Abstract

Introduction

Our group has completed an exercise study of 200 patients with mild Alzheimer's disease. We found improvements in cognitive, neuropsychiatric, and physical measures in the participants who adhered to the protocol. Epidemiological studies in healthy elderly suggest that exercise preserves cognitive and physical abilities to a higher extent in APOE ε4 carriers.

Methods

In this post hoc subgroup analysis study, we investigated whether the beneficial effect of an exercise intervention in patients with mild AD was dependent on the patients' APOE genotype.

Results

We found that patients who were APOE ε4 carriers benefitted more from the exercise intervention by preservation of cognitive performance and improvement in physical measures.

Discussion

This exploratory study establishes a possible connection between the beneficial effects of exercise in AD and the patients' APOE genotype. These findings, if validated, could greatly impact the clinical management of patients with AD and those at risk for developing AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Exercise, APOE, Genetic, Intervention

1. Introduction

Cognitive decline in late life and dementia are associated with decreases in activities of daily living, quality of life, and increased mortality. There are an estimated 46.8 million people living with dementia worldwide [1], and with an aging population, dementia and Alzheimer's disease (AD) constitute a growing health and economic burden [1], [2]. Several genetic, environmental, and clinical risk factors for developing AD have been identified. The presence of the apolipoprotein-E (APOE) ε4 allele is the most important genetic risk factor, whereas physical inactivity is a major lifestyle risk factor for the development of AD [3].

The ε4 allele of the APOE gene located on chromosome 19 is associated with higher risk of developing AD and at an earlier age, whereas the ε2 allele has a protective effect against AD, and the ε3 allele is considered neutral [4]. The neuropathological hallmarks of AD are intracellular neurofibrillary tangles and extracellular plaques composed of tau and amyloid beta42 (A-beta), respectively [5]. Further neuropathological findings include increased inflammation and oxidative stress [6], [7]. It has been suggested that APOE ε4 genotype can lead to AD pathogenesis by several pathways: (1) damage of the vascular system in the brain; (2) initiation or acceleration of A-beta accumulation, aggregation, and deposition in the brain; (3) impaired cholesterol transport; and (4) increased neuroinflammation [4].

In animal and human studies, exercise has shown a neuroprotective effect, notably in the hippocampus and the dentate gyrus, both areas showing pathological changes in AD [8], [9], [10], [11]. Observational studies in healthy elderly persons show that higher levels of physical activity are associated with lower risk of cognitive decline, better cognitive performance, and preservation of hippocampal volume and that the effect was stronger in APOE ε4 carriers when compared to noncarriers [12], [13], [14]. Furthermore, higher levels of physical activity have been associated with faster reaction time in APOE ε4 carriers compared to noncarriers [15]. In subjects with MCI, 1 study investigated the effect of APOE genotype on physical function and found that walking speed was reduced in the APOE ε4 carriers, compared to noncarriers [16]. Despite evidence from observational studies in healthy elderly and MCI subjects of associations between physical inactivity, cognitive decline, and APOE ε4 carrier status, there is a paucity of knowledge of these associations in subjects with AD dementia. Similarly, in exercise intervention studies, positive effect of APOE ε4 carrier status on cognition has been found in healthy elderly subjects [17], [18], but to the best of our knowledge, this effect has not been evaluated in patients with AD.

Because the search for pharmacological treatments to slow down or reverse AD has not proven successful so far [19], researchers have turned their attention toward nonpharmacological approaches, including exercise, to try to slow the cognitive decline [20], [21]. Our group has previously investigated the effect of exercise in patients with mild AD in the “Preserving Cognition, Quality of Life, Physical Health and Functional Ability in Alzheimer's disease: The Effect of Physical Exercise (ADEX) study” [22]. In that study, for subjects who adhered to the protocol, we found a significant improvement in cognitive performance measured by the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT), neuropsychiatric symptoms [22], as well as in physical function [23].

Results of all cognitive tests (SDMT, ADAS-Cog, Stroop Color and Word test, verbal fluency, and MMSE) have been published [22]; we found a significant effect of exercise on our primary outcome measure, SDMT, but no effect of the exercise intervention was detected on the other cognitive tests. SDMT was chosen as primary outcome because this test is sensitive to very early changes in aspects of executive function (mental speed and attention) in AD [24]. Executive function is considered to be particularly sensitive to the effect of physical exercise [25], [26], which recently was corroborated in two trials of moderate- to high-intensity exercise in sedentary older adults [27] and patients with MCI [28] where executive function and performance on SDMT was improved by exercise.

In this post hoc subgroup analysis of patients with mild AD from the ADEX study, we aimed to investigate if the significant improvements in cognitive and physical outcomes were dependent on the patients' APOE genotype.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patient cohort and baseline characteristics

A total of 200 patients from eight memory clinics in Denmark were randomized to either a control group (n = 93) or an intervention group (n = 107), and 190 patients completed follow-up [29]. The inclusion/exclusion criteria have been described previously in the study by Hoffmann et al. [30]. Briefly, the patients were diagnosed with AD according to the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria [29] before enrollment in the trial, were between 50 and 90 years of age, and had a MMSE score ≥20.

Patient baseline characteristics have been summarized in Table 1. All patients gave blood samples before and after the intervention. The patients' APOE genotype was not known at the time of the exercise intervention because APOE genotyping was not part of the routine diagnostic procedure and was only analyzed after the end of the trial.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study cohort

| Controls |

Exercise |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APOE ε4 noncarriers | APOE ε4 carriers | P value | APOE ε4 noncarriers | APOE ε4 carriers | P value | |

| n | 21 | 72 (27 homozygotes) | 34 | 72 (27 homozygotes) | ||

| Gender | 0.45∗ | 0.23∗ | ||||

| Males, n (%) | 11 (52.4) | 41 (56.9) | 17 (50) | 43 (59.7) | ||

| Females, n (%) | 10 (47.6) | 31 (43.1) | 17 (50) | 29 (40.3) | ||

| Age, years† | 68.0 (8.8) | 72.5 (6.5) | 0.01‡ | 67.9 (9.1) | 70.8 (6.4) | 0.06‡ |

| MMSE† | 25.0 (3.6) | 23.9 (3.9) | 0.27‡ | 24.4 (3.5) | 23.6 (3.3) | 0.26‡ |

| Education, years† | 11.5 (2.9) | 11.9 (2.7) | 0.55‡ | 12.0 (2.9) | 11.9 (2.6) | 0.83‡ |

P values are APOE ε4 carriers versus APOE ε4 noncarriers. Bold value denotes statistical significance P < 0.05.

Chi-squared test.

Given as mean ± (standard deviation).

Independent t-test.

The study was approved by the ethical committee of the Capital Region of Denmark (H-3-2011-128) and the Danish Data protection agency (Capital Region of Denmark, 30-0718). All patients gave informed consent before enrollment (ClinicalTrials.gov registration number: NCT01681602).

2.2. Exercise intervention

The physical exercise intervention was supervised aerobic exercise at moderate-to-high intensity (70–80% of maximal heart rate [HR] measured by pulse watches) 1 hour, three times weekly for 16 weeks in groups of two to five participants. The exercise protocol has been described in detail in the study by Sobol et al. [31] and consisted of a short warm-up session followed by aerobic exercise on treadmill, stationary bike, and cross-trainer.

2.3. APOE genotype

DNA was isolated with Promega Maxwell DNA purification kits (Promega, Madison, WI), according to the manufacturer's protocol from 250 μL of buffy coat from 6 mL EDTA vials. APOE genotyping for the ε2, ε3, and ε4 alleles was performed with a TaqMan qPCR assay as described by Koch et al. [32].

2.4. Clinical outcomes

We have previously published the results of our exercise intervention on cognitive [22] and physical [23] outcomes. We found a significant effect of exercise on neuropsychiatric symptoms measured by the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) in the intention-to-treat group. Patients who reached the target intervention intensity of 70% of maximum HR and participated in at least two-thirds of the exercise sessions (per-protocol group, termed “high exercise group,” n = 66 of 107 patients) improved significantly on NPI as well as on a cognitive test of attention and mental speed (SDMT). We therefore chose these two outcomes for analysis in the present study to investigate whether the effect was different in APOE ε4 carriers compared to noncarriers.

2.4.1. Cognitive outcome

SDMT assesses mental speed and attention. Using the number and symbol key at the top of the test page, participants were asked to correctly decode several lines of symbols [33]. The total number of correct decodings in 120 s was used as outcome.

2.4.2. Neuropsychiatric outcome

NPI is a caregiver-rated 12-point questionnaire assessing 12 different behavioral and psychological symptoms common in AD. The primary caregiver rates each symptom according to frequency and severity [34].

2.4.3. Physical outcomes

Timed-Up-and-Go test assesses basic mobility by measuring the time it takes for a person to stand up from a chair, walk 3 meters, cross a line, turn around, and walk back to the chair and sit down [35].

Timed 10-meter walk test assesses gait speed on a 10-meter long course [36].

Timed 400-meter walk test assesses walking endurance measured on a 20-meter long course marked with colored cones [37].

Dual task performance is measured with the timed 10-meter walk test combined with counting backward from 50 [36].

Maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max): the submaximal test for estimating maximal oxygen uptake is considered to be valid for assessing changes in cardiovascular fitness (aerobic fitness) and is estimated based on the workload and average HR during the last minute of a 6-minute cycle test, corrected for age and body weight [38].

2.5. Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics were compared between randomization groups and between APOE genotypes with chi-square tests (categorical characteristics) and t-tests (continuous characteristics). The effect of the exercise intervention was assessed separately for APOE ε4 carriers and noncarriers in a linear regression model for each outcome as intention-to-treat analyses including all patients were performed and per-protocol analyses where only patients who reached the target intervention intensity of 70% of maximum HR and participated in at least two-thirds of the exercise sessions were included. Possible differential dropout between the randomization groups was adjusted for by weighting the available observations by the inverse of the probability of being in the data, estimated in logistic regression models including baseline characteristics of the patients. The analysis was performed with generalized estimating equations to account for the weighting and for repeated measurements. Analyses were done with SAS v9.4. A significance level of 5% was used.

3. Results

3.1. Patient cohort

Baseline characteristics of the patient cohort are summarized in Table 1. There was an even distribution of APOE ε4 carriers versus noncarriers in the control and intervention groups, with approximately 70% being carriers of the APOE ε4 allele. We did not find significant differences in baseline characteristics between the randomization groups. When analyzed by the patients' APOE genotype, the APOE ε4 noncarriers were significantly younger than the APOE ε4 carriers in the control group. There was no significant difference in gender distribution, MMSE, or years of education between the APOE ε4 carriers and the APOE ε4 noncarriers.

3.2. Clinical outcomes

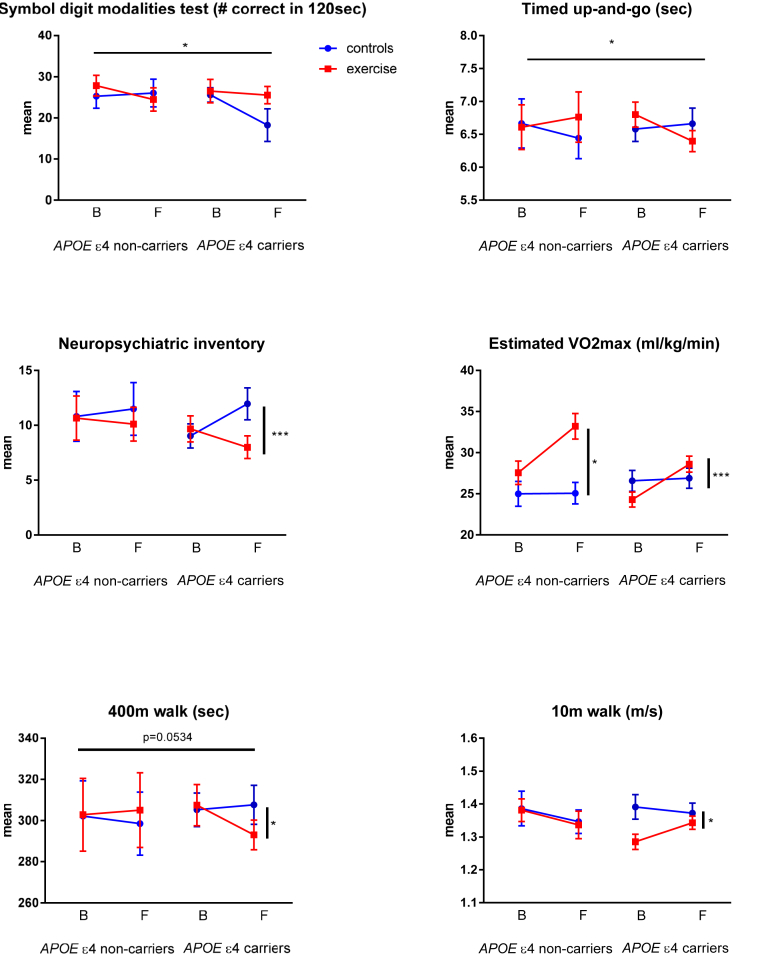

Carriers of the APOE ε4 allele who participated in the exercise arm maintained their performance on SDMT while APOE ε4 carriers who did not exercise had a decline in performance (Table 2). Exercise did not influence SDMT scores in the APOE ε4 noncarrier patients. There was a stabilizing effect of exercise on SDMT in APOE ε4 carriers compared to noncarriers, P = .0236 (Table 2, Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Effects of the intervention in APOE ε4 noncarriers and APOE ε4 carriers

| Mean (SEM) |

APOE ε4 noncarriers |

APOE ε4 carriers |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline |

Follow-up |

Baseline |

Follow-up |

||||||||||

| Controls | Exercise | P value∗ | Controls | Exercise | P value† | Controls | Exercise | P value∗ | Controls | Exercise | P value† | P value‡ | |

| Symbol Digit Modalities Test, # in 90 min | 25.78 (2.84) | 27.84 (2.50) | 0.0770 | 26.05 (3.35) | 24.49 (2.84) | 0.1637 | 25.58 (1.78) | 26.51 (2.84) | 0.9446 | 18.24 (3.97) | 25.55 (2.10) | 0.0598 | 0.0236 |

| Neuropsychiatric Inventory, range 0–144 | 10.81 (2.27) | 10.66 (2.02) | 0.6413 | 11.49 (2.40) | 10.10 (1.54) | 0.7331 | 9.03 (1.10) | 9.67 (1.19) | 0.4722 | 11.96 (1.45) | 7.80 (1.03) | 0.0002 | 0.1633 |

| Time-Up-and-Go, sec. | 6.67 (0.37) | 6.61 (0.34) | 0.3491 | 6.44 (0.31) | 6.76 (0.38) | 0.1794 | 6.58 (0.19) | 6.80 (0.19) | 0.2247 | 6.66 (0.34) | 6.40 (0.16) | 0.0153 | 0.0143 |

| Estimated VO2max, ml/kg/min | 24.99 (1.51) | 27.55 (1.43) | 0.1502 | 25.06 (1.31) | 33.21 (1.54) | 0.0240 | 26.57 (1.28) | 24.30 (0.91) | 0.0541 | 26.89 (1.22) | 28.60 (0.98) | 0.0002 | 0.8830 |

| 400 m walk, sec | 302.19 (17.11) | 302.80 (17.72) | 0.5428 | 298.48 (15.34) | 305.06 (18.19) | 0.5381 | 305.23 (8.11) | 307.53 (10.00) | 0.6896 | 307.63 (9.50) | 293.04 (7.18) | 0.0425 | 0.0681 |

| 10 m walk, m/sec | 1.39 (0.05) | 1.38 (0.03) | 0.9814 | 1.35 (0.04) | 1.34 (0.04) | 0.7779 | 1.39 (0.04) | 1.29 (0.02) | 0.0061 | 1.37 (0.03) | 1.34 (0.02) | 0.0269 | 0.1275 |

Bold values denote statistical significance P < 0.05.

Baseline difference between controls versus exercise within APOE status. Adjusted for clustering within training groups and centers.

Follow-up difference between controls versus exercise (beyond the difference present at the baseline) within APOE status. Adjusted for clustering within training groups and centers.

Effect of APOE status on the effect of exercise.

Fig. 1.

Mean scores in outcome intention-to-treat analysis. All participants analyzed with independent t-test, respectably of ApoE e4 carrier status and randomization group. B: baseline, F: 16-week follow-up, *P < .05, ***P < .001, displayed as mean score in groups with SD.

Similarly, APOE ε4 carriers who exercised had a significant and marked improvement in neuropsychiatric symptoms as evaluated by NPI compared to the control APOE ε4 carriers (P = .0002), although the effect of exercise on neuropsychiatric symptoms was absent in the APOE ε4 noncarriers (Table 2, Fig. 1).

3.3. Physical outcomes

We found that exercise improved Timed-Up-and-Go test in the APOE ε4 carriers versus noncarriers, P = .0143. Furthermore, we found significant improvement only in APOE ε4 carriers for timed 10-meter walk test (P = .0269), and timed 400-meter walk test (P = .0425), and these outcomes did not change significantly in noncarriers. Estimated VO2max improved significantly after exercise in both carriers and noncarriers (see Table 2 and Fig. 1).

4. Discussion

In this post hoc subgroup analysis study, we investigated whether the beneficial effect of an exercise intervention in patients with mild AD was driven by the patients' APOE genotype.

We found that patients who carried the APOE ε4 allele benefitted more from the exercise intervention than noncarriers on cognitive, neuropsychiatric, and physical measures. These findings are in line with the results from epidemiological studies showing that exercise improved cognitive and physical performance especially in carriers of the APOE ε4 allele [13], [16].

We found that patients who were carriers of the APOE ε4 allele in the exercise group maintained their performance in the SDMT test, whereas the carriers of the APOE ε4 allele in the control group deteriorated in performance. The effect of exercise on SDMT seen in this study is in line with the studies in patients with MCI [28] and in older adults [27] where executive function and performance on SDMT was improved by exercise. Furthermore, carriers of the APOE ε4 allele who exercise experienced an improvement in neuropsychiatric symptoms compared to a worsening in the control APOE ε4 carrier group. By contrast, we could not detect an effect of the exercise intervention on neuropsychiatric symptoms in the noncarrier group.

Carriers of the APOE ε4 allele who exercised improved their physical performance measured by walking speed compared both to noncarriers who exercised and to carriers in the control group. By contrast, we found that the noncarriers improved their cardiovascular fitness measured by estimated VO2max but this improvement was not reflected on their performance on the walking tests. All the participants in the intervention group had exercised on a stationary bike and most of them preferred this way of training endurance. Some participants did not perform treadmill walking exercises because they felt unsafe on the treadmill, and other than the treadmill-workout walking exercises were not part of the exercise intervention. Sitting on a test bike, where the movement is very simple and controlled, and where the assessor ensures that the cadence is kept, is probably less demanding than walking. Walking requires among other trunk stability, balance, and coordination. This will have an impact on the variation of spatiotemporal gait parameters, which has been shown to be greater in people with cognitive impairment [39].

In our previous work [22], we discovered that the highest effect on cognitive and physical end points was present in the subgroup of patients who exercised at the highest intensity and with most adhesion to the exercise program, termed the “high-exercise” group. In the current analysis, we did not find an additional effect of high exercise after segregating by APOE ε4 carrier status (data not shown). This could indicate that the effect exercise on cognitive and physical measures of carrying the APOE ε4 allele is equivalent to the effect of a higher intensity exercise regime.

There are several theories regarding why the APOE ε4 allele evolved in humans, and why this allele has been preserved during evolution up to modern times. Some have suggested that the APOE ε4 allele evolved in response to shifts in diet, response to a highly infectious environment, and need of increased absorption and reuptake of vitamin D [40], [41], cases where the APOE ε4 allele could be beneficial. The detrimental effects of the APOE ε4 allele, namely increased risk of atherosclerosis, stroke, and AD, were counteracted by the higher physical activity of the hunter-gatherers [42]. In modern societies, where high levels of physical activity are no longer required, this balance is skewed toward the adverse effects of the APOE ε4 allele. This highly speculative hypothesis would fit with the observation in the present study that physical exercise counteracts AD-related symptoms to a higher extent in APOE ε4 carriers than in noncarriers.

The mechanism for our observed APOE-mediated beneficial effect of exercise is unclear. It is not known whether physical exercise exerts its positive effect through disease-modifying or symptomatic mechanisms. The APOE genotypeinfluences several pathways related to AD, such as vascular damage, A-beta accumulation, cholesterol transport, and neuroinflammation [4]. In a small subsample of the ADEX patients, we could not detect an effect of exercise on CSF levels of biomarkers of AD pathology [43] or synaptic function [44], regardless of the patients' APOE genotype, and although this could be due to the small sample size, effects on other downstream pathways could be involved, such as positive effects on cerebral vasculature, improved cholesterol transport, or decreased neuroinflammation.

A limitation of this study is its exploratory nature because the ADEX study was not designed to elucidate the effects of the APOE genotype on an exercise intervention. However, this study is a large study of 200 patients from a genetically homogeneous population. All exercise sessions were supervised by qualified physical therapists; the exercise intensity was high as was the adherence to the exercise program. In our sample, 70% of the patients were carriers of the APOE ε4 allele; this is slightly higher than the background population of patients with AD with approximately 60% being carriers of one or two alleles of the APOE ε4 allele in northern Europe [45]. We have no simple explanation for this difference other than a possible random selection bias. This imbalance could influence our results because of the smaller number of subjects not carrying the APOE4 allele giving rise to a statistical type I error thus potentially not detecting significant changes that might happen in the noncarrier group.

Even if a nonpharmacological intervention such as exercise does not alter the known pathological pathways in AD, it can still be relevant for delaying disease progression by either purely symptomatic effects or by affecting some of the downstream biological processes. If exercise interventions could delay progression of AD and nursing home placement, this would be of benefit for patients and caregivers but also for society.

In conclusion, this exploratory study establishes a possible connection between the beneficial effects of exercise in AD and the patients' APOE genotype. These findings need to be replicated in larger studies specifically designed to investigate a potential causality. If replicated, these findings will contribute to a targeted and more personalized treatment approach in AD and give new hope for approximately 14% of the population with an increased genetic risk for AD.

Research in context.

-

1.

Systematic review: Review of the literature shows self-reported physical activity is associated with better cognitive and physical performance in healthy elderly who carry the APOE ε4 allele.

-

2.

Interpretation: In a post hoc analysis of a large multicenter study, we find that patients with Alzheimer's disease who carry the APOE ε4 allele benefit more from an exercise intervention on cognitive, neuropsychiatric, and physical measures compared to patients with Alzheimer's disease who do not carry the APOE ε4 allele.

-

3.

Future directions: These results need to be validated in larger studies. If positive, this knowledge could greatly impact the clinical management of Alzheimer's disease.

Acknowledgments

The Preserving Cognition, Quality of Life, Physical Health and Functional Ability in Alzheimer's Disease: The Effect of Physical Exercise (ADEX) study is supported by the Innovation Fund Denmark (J No. 10-092814). The Danish Dementia Research Centre is supported by grants from the Danish Ministry of Health (J No. 2007-12143-112, project 59506/J No. 0901110, project 34501) and the Danish Health Foundation (J No. 2007B004). The authors thank Kathrine Bjarnoe for technical support.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Prince M., Wimo A., Guerchet M., Ali G.-C., Wu Y.-T., Prina M. The global impact of dementia; London: 2015. International, World Alzheimer Report 2015; pp. 1–87. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brookmeyer R., Johnson E., Ziegler-Graham K., Arrighi H.M. Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.04.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Livingston G., Sommerlad A., Orgeta V., Costafreda S.G., Huntley J., Ames D. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017;390:2673–2734. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu C.C., Kanekiyo T., Xu H., Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: risk, mechanisms and therapy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:106–118. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jellinger K.A., Bancher C. Neuropathology of Alzheimer's disease: a critical update. J Neural Transm Suppl. 1998;54:77–95. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-7508-8_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luque-Contreras D., Carvajal K., Toral-Rios D., Franco-Bocanegra D., Campos-Pena V. Oxidative stress and metabolic syndrome: cause or consequence of Alzheimer's disease? Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2014;2014:497802. doi: 10.1155/2014/497802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heneka M.T., Carson M.J., El K.J., Landreth G.E., Brosseron F., Feinstein D.L. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:388–405. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)70016-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pereira A.C., Huddleston D.E., Brickman A.M., Sosunov A.A., Hen R., McKhann G.M. An in vivo correlate of exercise-induced neurogenesis in the adult dentate gyrus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5638–5643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611721104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erickson K.I., Miller D.L., Roecklein K.A. The aging hippocampus: interactions between exercise, depression, and BDNF. Neuroscientist. 2012;18:82–97. doi: 10.1177/1073858410397054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.West M.J., Coleman P.D., Flood D.G., Troncoso J.C. Differences in the pattern of hippocampal neuronal loss in normal ageing and Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 1994;344:769–772. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92338-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erickson K.I., Voss M.W., Prakash R.S., Basak C., Szabo A., Chaddock L. Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3017–3022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015950108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuit A.J., Feskens E.J., Launer L.J., Kromhout D. Physical activity and cognitive decline, the role of the apolipoprotein e4 allele. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:772–777. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200105000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lautenschlager N.T., Cox K.L., Flicker L., Foster J.K., van Bockxmeer F.M., Xiao J. Effect of physical activity on cognitive function in older adults at risk for Alzheimer disease: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;300:1027–1037. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.9.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith J.C., Nielson K.A., Woodard J.L., Seidenberg M., Durgerian S., Hazlett K.E. Physical activity reduces hippocampal atrophy in elders at genetic risk for Alzheimer's disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:61. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deeny S.P., Poeppel D., Zimmerman J.B., Roth S.M., Brandauer J., Witkowski S. Exercise, APOE, and working memory: MEG and behavioral evidence for benefit of exercise in epsilon4 carriers. Biol Psychol. 2008;78:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doi T., Shimada H., Makizako H., Tsutsumimoto K., Uemura K., Suzuki T. Apolipoprotein E genotype and physical function among older people with mild cognitive impairment. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2015;15:422–427. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Etnier J.L., Caselli R.J., Reiman E.M., Alexander G.E., Sibley B.A., Tessier D. Cognitive performance in older women relative to ApoE-epsilon4 genotype and aerobic fitness. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:199–207. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000239399.85955.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith J.C., Nielson K.A., Woodard J.L., Seidenberg M., Rao S.M. Physical activity and brain function in older adults at increased risk for Alzheimer's disease. Brain Sci. 2013;3:54–83. doi: 10.3390/brainsci3010054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khoury R., Patel K., Gold J., Hinds S., Grossberg G.T. Recent Progress in the Pharmacotherapy of Alzheimer's Disease. Drugs & Aging. 2017;34:811–820. doi: 10.1007/s40266-017-0499-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herholz S.C., Herholz R.S., Herholz K. Non-pharmacological interventions and neuroplasticity in early stage Alzheimer's disease. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13:1235–1245. doi: 10.1586/14737175.2013.845086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horr T., Messinger-Rapport B., Pillai J.A. Systematic review of strengths and limitations of randomized controlled trials for non-pharmacological interventions in mild cognitive impairment: focus on Alzheimer's disease. J Nutr Health Aging. 2015;19:141–153. doi: 10.1007/s12603-014-0565-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoffmann K., Sobol N.A., Frederiksen K.S., Beyer N., Vogel A., Vestergaard K. Moderate-to-High Intensity Physical Exercise in Patients with Alzheimer's Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;50:443–453. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sobol N.A., Hoffmann K., Frederiksen K.S., Vogel A., Vestergaard K., Braendgaard H. Effect of aerobic exercise on physical performance in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:1207–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bennett D.A., Wilson R.S., Schneider J.A., Evans D.A., Beckett L.A., Aggarwal N.T. Natural history of mild cognitive impairment in older persons. Neurology. 2002;59:198–205. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilbur J., Marquez D.X., Fogg L., Wilson R.S., Staffileno B.A., Hoyem R.L. The relationship between physical activity and cognition in older Latinos. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2012;67:525–534. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Netz Y., Wu M.J., Becker B.J., Tenenbaum G. Physical activity and psychological well-being in advanced age: a meta-analysis of intervention studies. Psychol Aging. 2005;20:272–284. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sink K.M., Espeland M.A., Castro C.M., Church T., Cohen R., Dodson J.A. Effect of a 24-Month Physical Activity Intervention vs Health Education on Cognitive Outcomes in Sedentary Older Adults: The LIFE Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2015;314:781–790. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.9617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baker L.D., Frank L.L., Foster-Schubert K., Green P.S., Wilkinson C.W., McTiernan A. Effects of aerobic exercise on mild cognitive impairment: a controlled trial. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:71–79. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKhann G., Drachman D., Folstein M., Katzman R., Price D., Stadlan E.M. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoffmann K., Frederiksen K.S., Sobol N.A., Beyer N., Vogel A., Simonsen A.H. Preserving cognition, quality of life, physical health and functional ability in Alzheimer's disease: the effect of physical exercise (ADEX trial): rationale and design. Neuroepidemiology. 2013;41:198–207. doi: 10.1159/000354632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sobol N.A., Hoffmann K., Vogel A., Lolk A., Gottrup H., Hogh P. Associations between physical function, dual-task performance and cognition in patients with mild Alzheimer's disease. Aging Ment Health. 2016;20:1139–1146. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1063108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koch W., Ehrenhaft A., Griesser K., Pfeufer A., Muller J., Schomig A. TaqMan systems for genotyping of disease-related polymorphisms present in the gene encoding apolipoprotein E. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2002;40:1123–1131. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2002.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith A. Western Psychological Services; California, USA: 1973. Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cummings J.L., Mega M., Gray K., Rosenberg-Thompson S., Carusi D.A., Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2308–2314. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGough E.L., Kelly V.E., Logsdon R.G., McCurry S.M., Cochrane B.B., Engel J.M. Associations between physical performance and executive function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: gait speed and the timed “up & go” test. Phys Ther. 2011;91:1198–1207. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20100372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lamoth C.J., van Deudekom F.J., van Campen J.P., Appels B.A., de Vries O.J., Pijnappels M. Gait stability and variability measures show effects of impaired cognition and dual tasking in frail people. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2011;8:2. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-8-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simonsick E.M., Fan E., Fleg J.L. Estimating cardiorespiratory fitness in well-functioning older adults: Treadmill validation of the long distance corridor walk. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:127–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cink R.E., Thomas T.R. Validity of the Astrand-Ryhming nomogram for predicting maximal oxygen intake. Br J Sports Med. 1981;15:182–185. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.15.3.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allali G., Annweiler C., Blumen H.M., Callisaya M.L., De Cock A.M., Kressig R.W. Gait phenotype from mild cognitive impairment to moderate dementia: Results from the GOOD initiative. Eur J Neurol. 2016;23:527–541. doi: 10.1111/ene.12882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Finch C.E. Evolution of the human lifespan, past, present, and future: phases in the evolution of human life expectancy in relation to the inflammatory load. Proc Am Philos Soc. 2012;156:9–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eisenberg D.T., Kuzawa C.W., Hayes M.G. Worldwide allele frequencies of the human apolipoprotein E gene: Climate, local adaptations, and evolutionary history. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2010;143:100–111. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raichlen D.A., Alexander G.E. Exercise, APOE genotype, and the evolution of the human lifespan. Trends Neurosci. 2014;37:247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steen Jensen C., Portelius E., Siersma V., Hogh P., Wermuth L., Blennow K. Cerebrospinal Fluid Amyloid Beta and Tau Concentrations Are Not Modulated by 16 Weeks of Moderate- to High-Intensity Physical Exercise in Patients with Alzheimer Disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2016;42:146–158. doi: 10.1159/000449408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jensen C.S., Portelius E., Hogh P., Wermuth L., Blennow K., Zetterberg H. Effect of physical exercise on markers of neuronal dysfunction in cerebrospinal fluid in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2017;3:284–290. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ward A., Crean S., Mercaldi C.J., Collins J.M., Boyd D., Cook M.N. Prevalence of apolipoprotein E4 genotype and homozygotes (APOE e4/4) among patients diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2012;38:1–17. doi: 10.1159/000334607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]