Abstract

This article presents the raw and analysed data on the absorption features of 30 pigments commonly occurring in phytoplankton. All unprocessed absorption spectra are given between 350 and 800 nm. The presented data also gives information on the wavelength of the main absorption peaks together with associated magnitudes of the concentration-specific absorption coefficient.

Keywords: Pigments, Phytoplankton, Absorption

Specifications table

| Subject area | Biology |

| More specific subject area | Phytoplankton biology; Marine biology; Marine bio-optics |

| Type of data | Tables, figures, separate .txt files with entire measured spectra |

| How data was acquired | UV-VIS double-beam spectrophotometer (GBC Scientific Equipment Ltd., Cintra 404); software: Cintral ver. 2.2 |

| Data format | Analysed |

| Experimental factors | Pigments were dissolved in either 100% ethanol or 90% acetone as received from DHI (Denmark) or Sigma Aldrich prior to the measurements being made. |

| Experimental features | The absorption spectra were measured in a 1-cm quartz-glass cuvette using a dual-beam spectrophotometer against the pure solvent as a blank. The spectra were measured over the 350–800 nm spectral range in 1.3 nm increments. |

| Data source location | Hobart, TAS, Australia |

| Data accessibility | All data are provided in this article |

| Related research article | Baird, M.E., Mongin, M., Rizwi, F., Bay, L.K., Cantin, N.E., Soja-Woźniak, M., Skerratt, J., 2018. A mechanistic model of coral bleaching due to temperature-mediated light-driven reactive oxygen build-up in zooxanthellae. Ecol. Model. 386, 20–37 [1]. |

Value of the data

|

1. Data

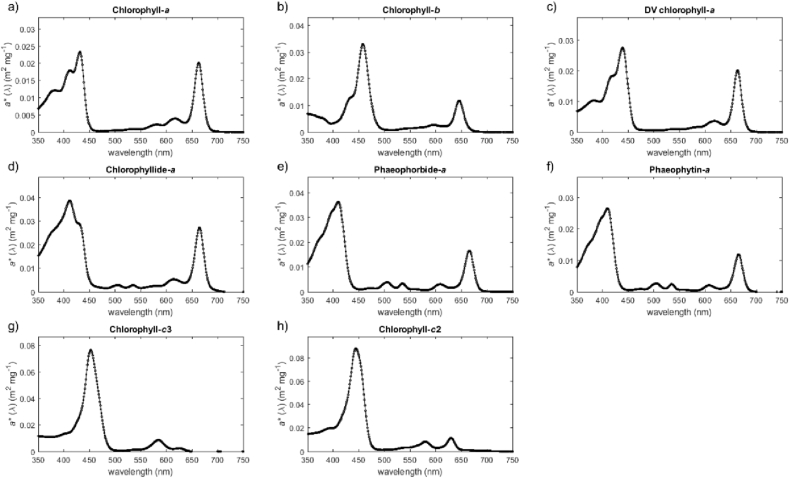

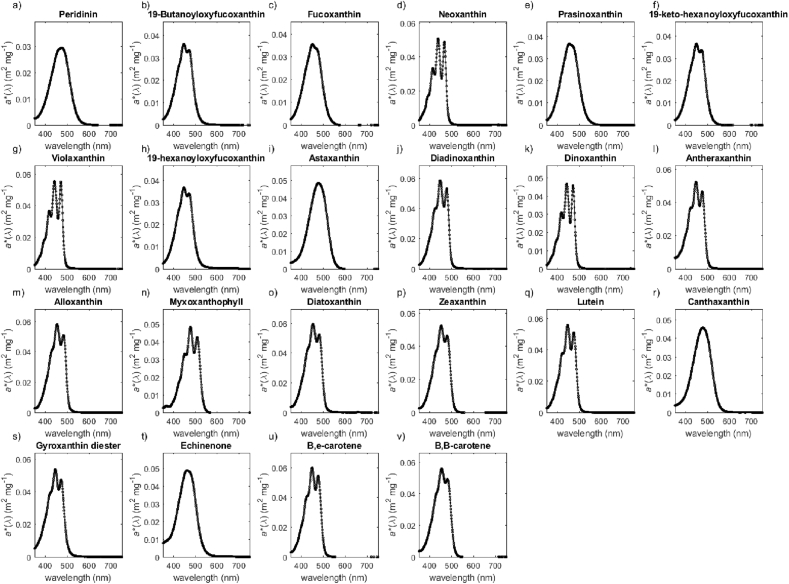

The unprocessed measurement data for the absorption spectra of chlorophylls (chlorophyll-a, chlorophyll-b, DV chlorophyll-a, chlorophyllide-a, phaeophorbide-a, phaeophytin-a, chlorophyll-c3, chlorophyll-c2) and carotenoids (peridinin, 19′-butanoyloxyfucoxanthin, fucoxanthin, neoxanthin, prasinoxanthin, 19′-keto-hexanoyloxyfucoxanthin, violaxanthin, 19′- hexanoyloxyfucoxanthin, astaxanthin, diadinoxanthin, dinoxanthin, antheraxanthin, alloxanthin, myxoxanthophyll, diatoxanthin, zeaxanthin, lutein, canthaxanthin, gyroxanthin diester, echinenone, β,ε-carotene, β,β-carotene) are given in separate files (Appendix A; carotenoids_concentration_specific_spectra.txt, chlorophylls_concentration_specific_spectra.txt). Fig. 1, Fig. 2 present pigment-specific absorption spectra for each of the analysed pigments and Table 1, Table 2 list the location of the main absorption peaks and the magnitude of the pigment-specific absorption coefficients at these local maxima for chlorophylls and carotenoids, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Concentration-specific absorption spectra of (a) chlorophyll-a, (b) chlorophyll-b, (c) DV chlorophyll-a, (d) chlorophyllide-a, (e) phaeophorbide-a, (f) phaeophytin-a, (g) chlorophyll-c3, (h) chlorophyll-c2.

Fig. 2.

Concentration-specific absorption spectra of (a) peridinin, (b) 19′-butanoyloxyfucoxanthin,(c) fucoxanthin, (d) neoxanthin, (e) prasinoxanthin, (f) 19′-keto-hexanoyloxyfucoxanthin, (g) violaxanthin, (h) 19′- hexanoyloxyfucoxanthin, (i) astaxanthin, (j) diadinoxanthin, (k) dinoxanthin, (l) antheraxanthin, (m) alloxanthin, (n) myxoxanthophyll, (o) diatoxanthin, (p) zeaxanthin, (q) lutein, (r) canthaxanthin, (s) gyroxanthin diester, (t) echinenone, (u) β,ε-carotene, (v) β,β-carotene.

Table 1.

Location of the main absorption peaks and the associated magnitude of the concentration specific absorption coefficient for chlorophyll-a, chlorophyll-b, DV chlorophyll-a, chlorophyllide-a, phaeophorbide-a, phaeophytin-a, chlorophyll-c3, and chlorophyll-c2.

| Name of pigment | Source | Lot/Batch number | Solvent | Main absorption peaks (nm) | Concentration specific absorption coefficient (m2 mg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorophyll-a | Sigma | BCBK2207V | 90% acetone | 431 | 0.0233 |

| 663 | 0.0202 | ||||

| 412 | 0.0179 | ||||

| 382 | 0.0122 | ||||

| 617 | 0.0040 | ||||

| Chlorophyll-b | Sigma | SLBF7339V | 90% acetone | 458 | 0.0330 |

| 646 | 0.0118 | ||||

| DV chlorophyll-a | DHI | 112 | 90% acetone | 439 | 0.0276 |

| 663 | 0.0203 | ||||

| Chlorophyllide-a | DHI | 125 | 90% acetone | 411 | 0.0387 |

| 665 | 0.0272 | ||||

| 615 | 0.0053 | ||||

| 535 | 0.0029 | ||||

| 506 | 0.0028 | ||||

| Phaeophorbide-a | DHI | 105 | 90% acetone | 410 | 0.0363 |

| 666 | 0.0166 | ||||

| 505 | 0.0039 | ||||

| 535 | 0.0034 | ||||

| 608 | 0.0031 | ||||

| Phaeophytin-a | DHI | 107 | 90% acetone | 410 | 0.0266 |

| 665 | 0.0119 | ||||

| 505 | 0.0027 | ||||

| 535 | 0.0024 | ||||

| 607 | 0.0021 | ||||

| Chlorophyll-c3 | DHI | 122 | 90% acetone | 452 | 0.0766 |

| 584 | 0.0085 | ||||

| 626 | 0.0024 | ||||

| Chlorophyll-c2 | DHI | 129 | 90% acetone | 444 | 0.0880 |

| 630 | 0.0113 | ||||

| 580 | 0.0083 |

Table 2.

Location of the main absorption peaks and the associated magnitude of the concentration-specific absorption coefficient for carotenoids (peridinin, 190-butanoyloxyfucoxanthin, fucoxanthin, neoxanthin, prasinoxanthin, 190-keto-hexanoyloxyfucoxanthin, violaxanthin, 190- hexanoyloxyfucoxanthin, astaxanthin, diadinoxanthin, dinoxanthin, antheraxanthin, alloxanthin, myxoxanthophyll, diatoxanthin, zeaxanthin, lutein, canthaxanthin, gyroxanthin diester, echinenone, b,ε-carotene, b,b-carotene).

| Name of pigment | Source | Lot/Batch number | Solvent | Main absorption peaks (nm) | Concentration specific absorption coefficient (m2 mg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peridinin | DHI | 111 | 100% ethanol | 474 | 0.0293 |

| 19'-Butanoyloxyfucoxanthin | DHI | 122 | 100% ethanol | 447 | 0.0362 |

| 471 | 0.0335 | ||||

| Fucoxanthin | DHI | 119 | 100% ethanol | 449 | 0.0355 |

| Neoxanthin | DHI | 122 | 100% ethanol | 438 | 0.0508 |

| 466 | 0.0489 | ||||

| 413 | 0.0333 | ||||

| Prasinoxanthin | DHI | 110 | 100% ethanol | 453 | 0.0367 |

| 19'-keto-hexanoyloxyfucoxanthin | DHI | 101 | 100% ethanol | 448 | 0.0365 |

| 471 | 0.0337 | ||||

| Violaxanthin | DHI | 138 | 100% ethanol | 441 | 0.0555 |

| 471 | 0.0552 | ||||

| 417 | 0.0365 | ||||

| 19'-hexanoyloxyfucoxanthin | DHI | 116 | 100% ethanol | 446 | 0.0367 |

| 471 | 0.0339 | ||||

| Astaxanthin | DHI | 105 | 100% acetone | 477 | 0.0486 |

| Diadinoxanthin | DHI | 117 | 100% ethanol | 447 | 0.0588 |

| 477 | 0.0535 | ||||

| 426 | 0.0402 | ||||

| Dinoxanthin | DHI | 103 | 100% ethanol | 442 | 0.0468 |

| 471 | 0.0458 | ||||

| 417 | 0.0316 | ||||

| Antheraxanthin | DHI | 127 | 100% ethanol | 446 | 0.0523 |

| 475 | 0.0464 | ||||

| 423 | 0.0369 | ||||

| Alloxanthin | DHI | 112 | 100% ethanol | 453 | 0.0583 |

| 482 | 0.0511 | ||||

| Myxoxanthophyll | DHI | 106 | 100% acetone | 477 | 0.0486 |

| 508 | 0.0427 | ||||

| 452 | 0.0333 | ||||

| Diatoxanthin | DHI | 133 | 100% ethanol | 452 | 0.0596 |

| 481 | 0.0524 | ||||

| Zeaxanthin | DHI | 131 | 100% ethanol | 452 | 0.0524 |

| 479 | 0.0464 | ||||

| Lutein | DHI | 128 | 100% ethanol | 446 | 0.0559 |

| 474 | 0.0508 | ||||

| 423 | 0.0381 | ||||

| Canthaxanthin | DHI | 131 | 100% ethanol | 478 | 0.0458 |

| Gyroxanthin diester | DHI | 105 | 100% ethanol | 445 | 0.0538 |

| 472 | 0.0473 | ||||

| Echinenone | DHI | 121 | 100% ethanol | 461 | 0.0488 |

| β,ε-carotene | DHI | 126 | 100% acetone | 488 | 0.0600 |

| 476 | 0.0544 | ||||

| β,β-carotene | DHI | 126 | 100% acetone | 454 | 0.0559 |

| 480 | 0.0492 |

2. Experimental design, materials, and methods

Pigment standards for chlorophyll-a and chlorophyll-b were prepared from extracts purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (www.sigmaaldrich.com), while other pigment standards were obtained from DHI (www.dhigroup.com). The source and the batch/lot number of each pigment are given in Table 1, Table 2. The standards were in either 90% acetone, 100% acetone or 100% ethanol (Table 1, Table 2). The final concentrations of the standards were measured by HPLC (High Performance Liquid Chromatography) with the CSIRO method [2], which is a modified version of the [3] technique, using C8 column and binary gradient system with an elevated column temperature. Pigments were identified by their retention time and their absorption spectra from the photo-diode array detector. Next, the pigment concentrations were determined through peak integration performed in Empower© software.

The absorption spectra of the pigment standards were measured in a 1-cm quartz-glass cuvette using a Cintra 404 (GBC Scientific Equipment Ltd.) UV-VIS dual-beam spectrophotometer against the pure solvent as a blank. The spectra were measured over the 350–800 nm spectral range in 1.3 nm increments. The absorbance (OD) obtained from the measurements was converted to an absorption coefficient (a(λ), m−1) by multiplying the appropriate baseline-corrected optical density values of each standard by 2.3 and dividing by the optical path length/cuvette thickness (0.01 m):

| (1) |

Finally, the concentration specific absorption coefficients (a*(λ), m2 g−1) were calculated by dividing each absorption coefficient by the respective pigment concentration.

Data presented in Fig. 1, Fig. 2 and in Table 1, Table 2 were null-point corrected by subtracting the absorption coefficient value at 750 nm assuming no absorption of pigments in the NIR region of the spectrum [4]. The spectra were also interpolated to yield absorption coefficients between 350 and 750 nm with the resolution of 1 nm using linear interpolation method (MATLAB, interp1.m).

Due to differences in the organic solvent and water refractive index (i.e. 1.352 for acetone, 1.361 for ethanol and 1.330 for water), the spectra may be wavelength-adjusted by using the ratio between the refractive index of the solvent and the water as done by [1].

Acknowledgements

CSIRO strategy funding was used to perform all the laboratory work.

Footnotes

Transparency document associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2019.103875.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2019.103875.

Transparency document

The following is the transparency document related to this article:

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Baird M.E., Mongin M., Rizwi F., Bay L.K., Cantin N.E., Soja-Woźniak M., Skerratt J. A mechanistic model of coral bleaching due to temperature-mediated light-driven reactive oxygen build-up in zooxanthellae. Ecol. Model. 2018;386:20–37. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hooker S.B., Van Heukelem L., Thomas C.S., Claustre H., Ras J., Schlüter L., Clementson L.A., Van der Linde D., Eker-Develi E., Berthon J.-F., Barlow R., Sessions H., Ismail H., Perl J. NASA Goddard Space Flight Center; Greenbelt: 2009. The Third SeaWiFS HPLC Analysis Round-Robin Experiment (SeaHARRE-3) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Heukelem L., Thomas C.S. Computer-assisted high-performance liquid chromatography method development with applications to the isolation and analysis of phytoplankton pigments. J. Chromatogr. A. 2001;910:31–49. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)00603-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stramski D., Piskozub J. Estimation of scattering error in spectrophotometric measurements of light absorption by aquatic particles form three-dimensional radiative transfer simulations. Appl. Opt. 2003;42:3634–3646. doi: 10.1364/ao.42.003634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.