Abstract

Emiliania huxleyi is a globally important marine phytoplankton that is routinely infected by viruses. Understanding the controls on the growth and demise of E. huxleyi blooms is essential for predicting the biogeochemical fate of their organic carbon and nutrients. In this study, we show that the production of nitric oxide (NO), a gaseous, membrane-permeable free radical, is a hallmark of early-stage lytic infection in E. huxleyi by Coccolithoviruses, both in culture and in natural populations in the North Atlantic. Enhanced NO production was detected both intra- and extra-cellularly in laboratory cultures, and treatment of cells with an NO scavenger significantly reduced viral production. Pre-treatment of exponentially growing E. huxleyi cultures with the NO donor S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP) prior to challenge with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) led to greater cell survival, suggesting that NO may have a cellular antioxidant function. Indeed, cell lysates generated from cultures treated with SNAP and undergoing infection displayed enhanced ability to detoxify H2O2. Lastly, we show that fluorescent indicators of cellular ROS, NO, and death, in combination with classic DNA- and lipid-based biomarkers of infection, can function as real-time diagnostic tools to identify and contextualize viral infection in natural E. huxleyi blooms.

Subject terms: Cellular microbiology, Water microbiology

Introduction

Emiliania huxleyi is a cosmopolitan species of coccolithophore, a group of unicellular, eukaryotic marine phytoplankton that produces intricate shells (coccoliths) of calcium carbonate. As both a dominant calcifier and a bloom-forming photoautotroph, E. huxleyi exerts a profound influence on marine biogeochemical cycles (particularly of carbon and sulfur) and food web dynamics. E. huxleyi is known for forming large annual blooms in the North Atlantic, often spanning >105 km2 with cell densities exceeding 106 cells l−1 [1–3]. These blooms are associated with dimethyl sulfide production in the surface ocean and flux into the atmosphere [4], increased albedo and heating of the surface ocean due to their coccoliths [5], and enhanced export flux of carbonate to the deep ocean [6].

Understanding the mechanisms of E. huxleyi bloom termination is necessary for predicting the fate of its calcium carbonate and fixed organic carbon in the ocean. E. huxleyi is often infected by large, double stranded DNA viruses belonging to the group Phycodnaviridae [7–9]. These Coccolithoviruses, known as EhVs, have been shown to cause the termination of E. huxleyi in culture [10, 11] and natural blooms [12–16]. One paradigm holds that viral lysis shunts fixed carbon away from downward vertical flux or transfer to higher trophic levels by stimulating cell lysis and bacterial respiration of dissolved organic carbon in the surface ocean [17, 18]. However, the biogeochemical and ecosystem consequences of infection could vary among different phytoplankton species. Recent evidence suggests that infection of E. huxleyi may actually facilitate aggregation and sinking of particulate carbon into the mesopelagic where it is subsequently respired [12, 15]. This may be a result of increased cellular production of transparent exopolymeric particles (TEP) during infection, which acts to enhance particle aggregation and couple infection with microzooplankton grazing [19].

Due to the ecological significance of E. huxleyi blooms and the range of recently developed diagnostic tools for studying infection, E. huxleyi and EhVs have emerged as one of the best described systems for understanding the molecular mechanisms of infection in marine eukaryotic microalgae [20]. During infection, EhVs co-opt and rewire cellular lipid biosynthetic machinery, producing viral-specific classes of glycosphingolipids (vGSLs) [11, 16, 21] and betaine-like lipids [22]. Accumulation of these polar lipids during infection occur concomitant with a late stage increase in production of reactive oxygen species (ROS; [23–25]), particularly hydrogen peroxide (H2O2; [25]), caspase activity, and metacaspase expression [10, 16], ultimately leading to programmed cell death (PCD; [26]) in the form of autophagy [27].

The dynamics of ROS production during viral infection are well described [16, 23, 25]. Little is known, however, about the role(s) of reactive nitrogen species (RNS), such as nitric oxide (NO), in modulating subcellular redox pathways and associated cellular responses. NO is a small, uncharged free radical gas that has been shown to be involved in a myriad of biological functions, including immunity, stress adaptation, and normal growth in all branches of life [28–31]. The foundation for this breadth of action rests on the broad reactivity of NO with various cellular targets, as well as its ability to diffuse across membranes to act both intra- and extra-cellularly. Of particular interest is the role of NO in modifying cellular ROS pools, either via radical–radical reactions or indirectly through the regulation of pro- or anti-oxidant pathways [32–34]. Although the sources(s) of NO synthesis in plants and photosynthetic protists is still unresolved [35], its signaling function during cellular response to diverse biotic and abiotic stressors is well known and summarized in several in-depth reviews [36, 37]. In diatoms, for instance, NO is part of a stress-surveillance system that senses and responds to the toxic polyunsaturated aldehyde decadeinal [38–40].

To date, investigations on the role(s) of NO in E. huxleyi physiology have been limited. One study demonstrated E. huxleyi growth rate and maximum cell densities increased in response to low levels of exogenously added NO [41]. In addition, we have previously shown that E. huxleyi cell lysates possess the enzymatic capacity to produce NO from nitrite and NADH via nitrate reductase [42]. There is, however, a notable gap in our knowledge of the mechanistic roles of this ubiquitous signaling molecule in E. huxleyi ecophysiology, including during viral infection. Given EhV infection induces PCD through elevated ROS production, it stands to reason that NO may play an important interactive role in infection dynamics. Here, we demonstrate that elevated intracellular NO production is a hallmark of early-stage lytic viral infection of E. huxleyi both in culture and in natural populations in the North Atlantic. Scavenging of intracellular NO leads to a dose-dependent reduction in viral burst sizes, indicating that NO is critical for maximal viral production in lab conditions. Using a novel liposome-enabled electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy method [42], we also show that elevated extracellular NO is observed during infection. Our work further suggests that intracellular NO production upregulates cellular antioxidant activity during the early stages of infection, keeping the cellular redox state favorable for viral replication.

Materials and methods

Culture conditions and viral infections

Emiliania huxleyi strain CCMP1516 was obtained from the Provasoli-Guillard National Center for Marine Algae and Microbiota and grown in batch culture in f/2 (minus Si) media at 18 °C on a 14:10 light:dark cycle at a light intensity of 250 µmol m−2s −1. Virus strain EhV201 (obtained courtesy of W. Wilson, Marine Biological Association, Plymouth, UK) was propagated in batch cultures of E. huxleyi CCMP1516. Viral lysates were passed through a 0.45 µm pore-size PVDF syringe filter to remove cell debris. For infection experiments, E. huxleyi was inoculated with EhV during mid-exponential growth (~5.0 × 105 cells ml−1) at a virus-to-host ratio of 5:1. Uninfected E. huxleyi cultures served as controls.

Enumeration of cells and viruses

E. huxleyi cell abundances were quantified using either a BD InFlux Mariner 209S flow cytometer or a BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer. Cell abundances were determined based on the chlorophyll autofluorescence (Ex/Em: 488 nm, 692 nm) vs. forward scatter signature. Free viruses were quantified by flow cytometry according to [43]. See Supplementary Information for additional flow cytometry methods.

Intracellular NO detection

Semi-quantitative measurements of intracellular NO were made using the NO specific fluorescent probe DAF-FM Diacetate (DAF-FM DA; Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA). DAF-FM DA passes through cell membrane, is cleaved by intracellular esterases to DAF-FM, and accumulates inside the cell. DAF-FM is non-fluorescent until it binds to NO or its oxidized products to form a fluorescent triazole product, DAF-FM-T [44]. Stocks of DAF-FM DA were made to 5 mM in DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and used at a final concentration of 5 µM. Stained samples were incubated in the dark at RT for 45 min. Mean fluorescence intensity per cell was determined by flow cytometry (Ex/Em: 488 nm, 520 nm). An unstained sample was run to account for background autofluorescence. Several controls were run to contextualize DAF-FM DA results and are described below.

Chemical identification of DAF-FM-T in cells

The presence of the fluorescent DAF-FM-T triazole product in cells treated with NO donors was chemically confirmed using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and ion-trap mass spectrometry (MS). Cultures of E. huxleyi CCMP1516 were treated with the NO donors S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP; Thermo Fisher) and sodium nitroprusside (SNP; Sigma-Aldrich) at 100 µM and 1 mM, respectively, and stained with 5 µM DAF-FM DA. A DAF-FM-T standard was generated in vitro by exposing 50 µM DAF-FM (Thermo Fisher) to an excess ( > 50 mM) of SNP. Identification of DAF-FM and DAF-FM-T was confirmed by MS2 spectra of the 413 m/z and 424 m/z molecular ions, which showed diagnostic neutral loss of CO2 (44 m/z) as previously characterized [45]. See Supplementary Information for full description.

Intracellular esterase activity

Intracellular esterase activity was measured in infected and uninfected cells using a general fluorogenic esterase substrate. Cell lysates were generated and protein was quantified (see Supplementary Information). A total of 2 µg of protein was incubated with 25 µM 4-Methylumbelliferyl butyrate (Sigma-Aldrich). The time course of fluorescence (Ex/Em: 365 nm, 440 nm) was measured every 2 min for 1 h using a SpectraMax M3 microplate reader. Esterase activity is expressed as the rate of change in fluorescence (RFU) per µg protein.

Intracellular ROS and cell death analysis

Cellular ROS production was assessed using the fluorescent probe CM-H2DCFDA (Thermo Fisher), which has a broad reactivity with a variety of ROS. Stocks of CM-H2DCFDA were made up to 1 mM in DMSO and used at a final concentration of 5 µM. Samples were incubated in the dark at RT for 60 min. The percentage of dead cells in cultures was determined using SYTOX Green (Thermo Fisher). SYTOX Green (5 mM stock solution in DMSO) was used at a final concentration of 1 µM and incubated in the dark at RT for 10–15 min. Stained samples (Ex/Em: 488 nm, 520 nm), along with an unstained control, were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Extracellular NO measurements

In situ, cell-derived NO produced during infection and present in the surrounding media was monitored using liposome-encapsulated spin trap (LEST) and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy, as previously described [42]. In brief, liposomes were prepared from a 9:1 molar ratio of the phospholipids POPC and DPPG (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL) in chloroform containing 10 mM of the NO spin trap N-methyl-D-glucamine dithiocarbamate (MGD) and 2 mM ammonium iron (II) sulfate. See Supplementary Information for more details.

LEST (25 µL) was incubated in 10 ml of triplicate infected and uninfected cultures adjusted to equal cell densities with f/2 (minus Si) media for 3 h in the dark at RT. LEST incubated in f/2 (minus Si) served as a negative control; LEST incubated in the presence of 200 µM of the NO donor NOC-9 (Sigma-Aldrich) served as a positive control. After incubation, LEST was pelleted by centrifugation (20,000 × g, 30 min, 4 °C). The supernatant was removed such that 30 µL of LEST pellet and buffer remained. The pellet and buffer were homogenized, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C. For EPR analysis, frozen LEST was thawed and drawn up into microcapillary tubes. EPR spectra were collected and the signal from spin-trapped NO quantified as described previously [42]. See Supplementary Information for more details.

NO donor, NO scavenger, and hydrogen peroxide treatments

To further investigate the cellular role of NO during infection, the following experiments were conducted: (1) E. huxleyi-EhV infection in the presence of an NO scavenger, (2) monitoring physiology of E. huxleyi pre-treated with various concentrations of an NO donor and subsequently challenged with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and (3) determination of the total antioxidant capacity of E. huxleyi cell lysates both treated with an NO donor and undergoing infection. The NO donor used was S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP) and treatments were done at concentrations empirically determined to be non-lethal (up to 100 µM; Figure S7) for at least 16 h prior to H2O2 treatment or biomass harvest. Given SNAP has a donor half-life of ~6 h, this time period represents >2 half-lives. The NO scavenger used was carboxy-PTIO potassium salt (c-PTIO; Thermo Fisher) and was applied to cells at the time of infection at a range of concentrations (250 µM–1 mM dissolved in MilliQ). Treatments with H2O2 (30% w/w; Sigma-Aldrich) were performed between 10 and 100 µM. Cell abundance, percent dead cells, intracellular NO and ROS, and the photochemical quantum yield of photosystem II (Fv/Fm; see Supplementary Information) were monitored for these experiments.

Total antioxidant capacity

E. huxleyi cell lysates were generated and protein concentration was determined (see Supplementary Information). The total enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant capacity (TAC) of the extracts was determined using the Antioxidant Assay Kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), which measures the capacity of cell extracts to prevent the oxidation of ABTS (2,2’-azino-di-[3-ethylbenzthiazoline sulphonate]) in the presence of H2O2 compared to a standard of the vitamin E analog Trolox (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid). The assay and standard curve were run according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance at 750 nm was measured using a SpectraMax M3 microplate reader. TAC is expressed as the concentration (mM) of antioxidants in equivalents of Trolox normalized to the total protein concentration of the sample.

Fieldwork

Intracellular NO, ROS, and cell death were assessed for open ocean, EhV-infected E. huxleyi populations in the Northeast Atlantic during the North Atlantic Virus Infection of Coccolithophores Expedition (http://www.bco-dmo.org/project/2136) aboard the R/V Knorr. The NA-VICE traversed a 2000 nautical mile transect from the Azores to Iceland and identified E. huxleyi blooms at different stages of bloom formation and viral infection [12, 13, 15]. Individual CTD casts were characterized and grouped into stations- “early infection (EI)”, “early infection revisited (EIR)”, “late infection (LI)”, and “post infection (PI)”—using a combination of MODIS/AQUA satellite imagery, a suite of diagnostic lipid- and gene-based molecular biomarkers, analytical flow cytometry, in situ optical sensors, and sediment traps (methods described by [12]). Here we further divided the “early infection” population into “EI1” and “EI2” given the greater number of samples available at this site for analysis and to provide higher temporal resolution to the trends. In order to explore the robustness of the patterns observed, we explored additional data from three CTD casts not analyzed in the aforementioned study [12], along with an individual CTD cast (92) from EI1 to illustrate a comparative signal for an early infected population. See Supplementary Information for a list of casts in each station.

Water was collected at six depths—extending from the subsurface, through the mixed layer encompassing the chlorophyll maximum, and down to 150 m—using Niskin bottles mounted on a 24-position rosette equipped with a Seabird SBE conductivity-temperature-depth (CTD) profiler. Sub-samples were stained with DAF-FM Diacetate, CM-H2DCFDA, and SYTOX Green (5 µM) as described above. Stained samples, along with an unstained control, were run on a Guava flow cytometer (EMD Millipore, Burlington, MA) in duplicate. We present data from three depths per cast corresponding to the depth at which E. huxleyi cell abundance was highest, along with one sampling depth above and one sampling depth below the E. huxleyi maximum, in box-and-whisker plots. These depths generally ranged from 8 to 40 m and are listed in Table S2.

Data analysis and statistics

Flow cytometry data collected for laboratory experiments were analyzed using FlowJo (v. 10.2). Statistics (counts and mean fluorescence) were based on at least 1000 E. huxleyi events. Mean fluorescence per cell for DAF-FM Diacetate and CM-H2DCFDA stained samples are reported as the difference between the mean 520 nm fluorescence per cell of the stained sample and an unstained control. Percent SYTOX Green positive cells are reported as the percent of the total E. huxleyi population that has elevated 520 nm fluorescence relative to an unstained control.

Flow cytometry data for fieldwork were analyzed using GuavaSoft InCyte (v. 2.2.2). E. huxleyi was distinguished by pre-gating all events by chlorophyll and gating the E. huxleyi population off side scatter and forward scatter signatures corresponding to a reference culture. Statistics (counts and mean fluorescence) were based on at least 50 E. huxleyi events, with most samples encompassing 100–400 events, and averaged between two replicates per depth.

Statistically significant differences between infected and uninfected cultures for the parameters measured in this study were determined with Student’s t-tests (p < 0.05). To test differences between multiple means, a one-way ANOVA with a Tukey HSD post hoc test was used. Error bars on all graphs are ± standard error of the mean (se). Linear regression analysis was used to explore relationships between various parameters in the NA-VICE dataset. All statistical tests were performed in R and plots were generated using the ggplot2 package.

Results

Intracellular NO production increases during viral infection

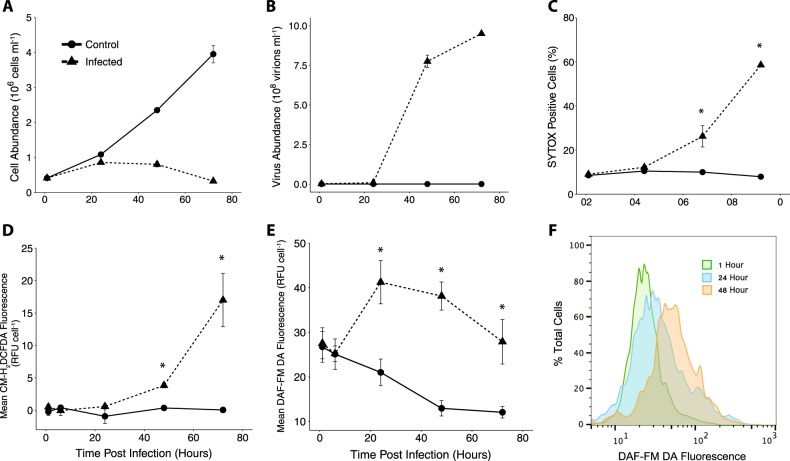

The onset of cell lysis by EhV infection at 48–72 h post infection (hpi) was marked by 12.5 and 60% decreases in cell abundance between 24–48 hpi and 48–72 hpi, respectively (Fig. 1a), coinciding with EhV production (Fig. 1b). Cell decline was concomitant with increases in both the proportion of dead or dying cells indicated by SYTOX Green (26% of culture at 48 hpi and 58% culture at 72 hpi; Fig. 1c) and intracellular ROS indicated by CM-H2DCFDA, increasing ~3-fold at 48 hpi and ~17-fold at 72 hpi (Fig. 1d). Both SYTOX and CM-H2DCFDA signals were strongest at 72 hpi. Notably, intracellular NO production did not follow these trends. Enhanced intracellular NO, assessed with DAF-FM DA, was observed earlier than the burst of ROS, increasing 1.5- to 2-fold above uninfected controls at 24 hpi (Fig. 1e, f). Intracellular NO production in infected cultures remained elevated compared to uninfected controls throughout the course of infection. A steady decrease in basal intracellular NO production was observed in uninfected control cells over the same time frame (Fig. 1e).

Fig. 1.

Dynamics of viral infection of E. huxleyi CCMP1516 by EhV201. a Cell abundance and b viral abundance of infected (triangles/dashed line) and uninfected (circles/solid line) cultures are a mean of n = 2 (±se) from one representative viral infection experiment. c Percent dead cells assessed by SYTOX Green, d intracellular ROS assessed by CM-H2DCFDA, and e intracellular NO assessed by DAF-FM DA. Values represent the mean of at least n = 4 (±se) across at least 3 distinct infection experiments. Statistically significant differences between infected and control cultures were determined using unpaired Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05). f Histogram overlay of DAF-FM DA fluorescence values of one representative infected culture at 1, 24, and 48 hpi

Intracellular esterase activity in infected cells remained unchanged during infection, while control cells displayed an increase in esterase activity during growth (Figure S1), suggesting that changes in intracellular esterase activity were not responsible for the higher DAF-FM DA fluorescence observed in infected cells. Furthermore, treatment of E. huxleyi with the NO donor SNAP increased DAF-FM DA cellular fluorescence, while the NO scavenger diminished fluorescence (Figure S2). The presence of the NO-bound, fluorescent DAF-FM-T product was also chemically confirmed using HPLC MS/MS in cells treated with two NO donors in a dose-dependent manner (Figures S3 and S4).

Viral infection triggers enhanced extracellular NO

Statistically significant differences in extracellular NO production were observed between infected and uninfected cultures at 48 hpi, 24 h after peak intracellular NO production (Fig. 2). Four-fold higher cell-normalized extracellular NO was observed at 48 hpi in the infected cultures relative to uninfected controls. A control experiment in which cells were incubated with LEST for 3 h found no impacts of LEST on cell survival, intracellular NO production, intracellular ROS production, or photochemical quantum yield of photosystem II (Fv/Fm) (Table S1).

Fig. 2.

Concentration of extracellular NO in E. huxleyi CCMP1516 infected with EhV201 (dark gray bars) and control cultures (light gray bars). Values represent the mean concentration of spin trap bound NO per cell over a 3 h incubation period (n = 3, ±se). Statistically significant differences between infected and control cultures were determined using unpaired Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05)

NO scavenging decreases viral burst size

EhV infection proceeded similarly in cells treated with the NO scavenger c-PTIO as that observed for untreated cells across a range of concentrations, with the onset of cell lysis and viral production occurring 48–72 hpi (Figure S5). There was, however, a statistically significant, dose-dependent decrease in viral burst size (the number of viruses produced per cell lysed between the 24–72 hpi) in c-PTIO-treated cells undergoing infection (Fig. 3). Exposure of uninfected control E. huxleyi cells to c-PTIO yielded no significant differences in cellular growth rates or Fv/Fm compared to untreated cells over the course of 72 h (Figure S6).

Fig. 3.

Viral burst sizes of infected E. huxeyi CCMP1516 treated with the NO scavenger c-PTIO, represented as the number of viral particles produced per cell lysed between 24 and 72 h post infection. Data are the mean of n = 2 (±se) and are a representative subset of multiple experiments. Statistically significant differences were determined using one-way ANOVA with the Tukey HSD post hoc test (letters denote statistically different subgroups; p < 0.05)

NO production stimulates antioxidant activity

Cells that were pre-treated with the NO donor SNAP prior to challenge with H2O2 (100 µM) had enhanced growth compared to cells treated with H2O2 only over the course of 72 h (Fig. 4a). Additionally, none of the SNAP pre-treated cultures experienced net cell death in the first 24 h of the experiment, though growth rates were diminished (Fig. 4a). In contrast, cells treated with H2O2 only experienced net cell decline within the first 24 h of treatment. SNAP pre-treated cultures were also able to maintain higher Fv/Fm values over the course of 72 h compared to the H2O2-only control (Fig. 4b). No effect was observed in DMSO-only pre-treated cultures (SNAP is dissolved in DMSO) in their response to H2O2 treatment (Figure S8).

Fig. 4.

Response of cells pre-treated with exogenous NO to H2O2. a Cell abundance and b Fv/Fm of H2O2 treated (100 µM) E. huxleyi CCMP1516 pre-treated with different concentrations (10 µM, 50 µM, and 100 µM) of the NO donor SNAP. Data are a representative subset of multiple experiments and values represent the mean of n = 2 (±se)

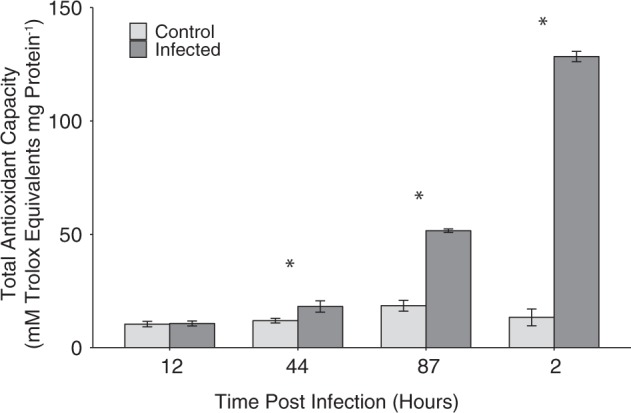

Cell lysates from cultures treated with SNAP exhibited significantly elevated protein-normalized total enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant capacity (TAC) (Fig. 5). The protein-normalized TAC of cells also increased in cells undergoing viral infection, with statistically significant differences between infected and uninfected cells beginning at 24 hpi. Little to no change was detected in uninfected control cultures during this same time period (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Protein-normalized, cellular antioxidant capacity of lysates from E. huxleyi CCMP1516 cultures treated with SNAP, along with a DMSO only and untreated controls. Statistically significant differences were determined using one-way ANOVA with the Tukey HSD post hoc test (letters denote statistically different subgroups, p < 0.05). Data shown are a representative subset of multiple experiments and are the mean of n = 2 (±se) per treatment

Fig. 6.

Protein-normalized, cellular antioxidant capacity of lysates from E. huxleyi CCMP1516 cultures undergoing infection with EhV201 (dark gray bars) and uninfected control cultures (light gray bars). Values represent the mean of n = 5 (+/− se) pooled from biological duplicates from one experiment. Statistically significance between control and infected cultures was determined used a Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05)

NO, ROS, and cell death in natural E. huxleyi blooms

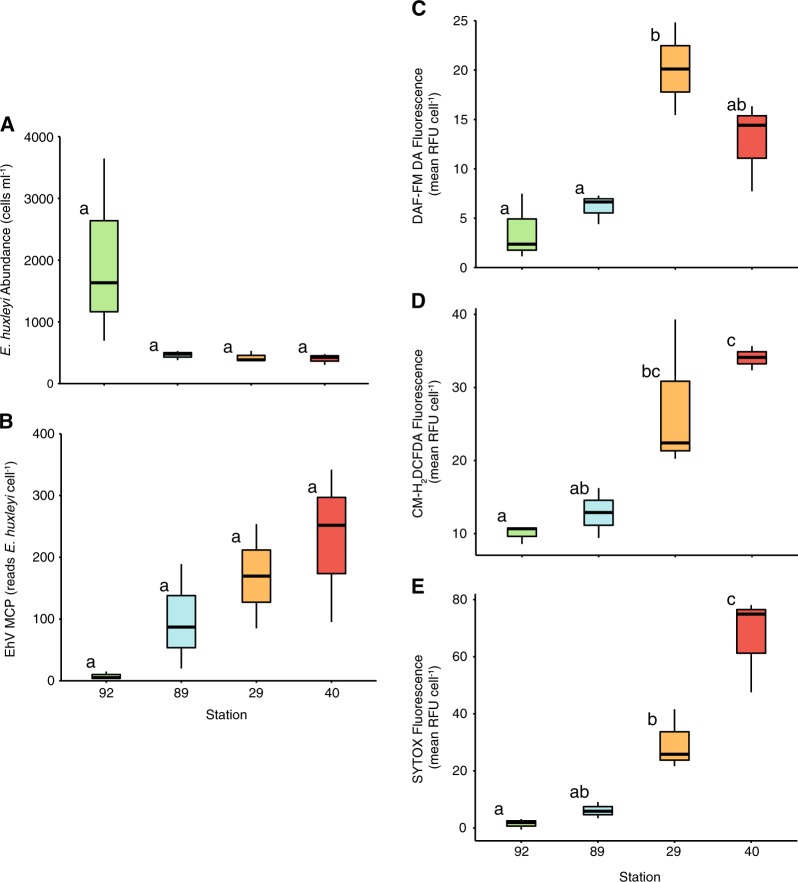

Open ocean E. huxleyi blooms were encountered during the NA-VICE cruise in the eastern North Atlantic that were at different stages of viral infection ([12, 13, 15]; Fig. 7a–c). Stations were designated as “early infection” (EI1, EI2, EIR), “late infection” (LI), and “post infection” (PI) by [12] based on the relative abundance of E. huxleyi (Fig. 7b) and cell-associated EhV populations (i.e., the number of copies of major capsid protein (MCP) per host cell) (Fig. 7c), as well as the inventories of diagnostic glycosphingolipid (such as vGSLs and sGSLs) and betaine-like lipid biomarkers, all of which are indicative of these stages of infection ([11, 16, 22, 46]; see Discussion). The abundance of E. huxleyi cells ranged from ~1000–3000 cells ml−1 in early infection stations and decreased in late (~1300 cells ml−1) and post (~800 cells ml−1) infection stations (Fig. 7b). Early infection stations had low copy numbers of EhV-derived MCP (mean of 44 copies cell−1). MCP copy number increased in late (mean of 120 copies cell−1) and post (mean of 800 copies cell−1) infection (Fig. 7c), indicative of an increased degree of infection.

Fig. 7.

Assessment of diagnostic stains for natural E. huxleyi populations in the North Atlantic. a Locations of distinct water masses sampled on the NA-VICE cruise along a 2000 nautical mile transect in the North Atlantic. Early, late, and post infection populations were previously characterized using lipid- and gene-based biomarkers [12]. Red numbers 29, 40, 89, and 92 represent CTD casts for which additional analyses are performed in this study. b, c Box-and-whisker plots showing the respective abundances of host E. huxleyi cells (cells ml−1) and replicating EhVs (MCP gene copies E. huxleyi cell−1) for the different sampled populations at three depths where E. huxleyi were present in highest abundance. d–f Box-and-whisker plots showing corresponding DAF-FM DA, CM-H2DCFDA, and SYTOX Green fluorescence for these populations. Data are an average of two replicates per depth sampled. Data in (a, b, c, and f) were published by Laber et al. [12]. For all box plots, upper and lower bounds of the box represent the 25% and 75% quartiles around the median. Vertical lines extend to data points no greater than 1.5 times the inter-quartile range. Data points that extend beyond this range are represented by dots. Statistically significant differences were determined using one-way ANOVA with the Tukey HSD post hoc test (letters denote statistically different subgroups, p < 0.05)

Intracellular NO production was elevated in EI2, EIR, LI, and PI, relative to the initial occupation of EI1, with a 5.2, 2.8, 3.0, and 5.0-fold higher mean per cell DAF-FM DA fluorescence, respectively (Fig. 7d). Intracellular ROS of E. huxleyi at these stations was generally low and not statistically different from each other. ROS was elevated only in E. huxleyi cells found in the PI populations (Fig. 7e), with an average 3.5-fold higher mean per cell CM-H2DCFDA fluorescence than the other stations, consistent with observations of a late phase infected culture (Fig. 1). Similarly, cell death was moderately elevated in LI populations and significantly higher in PI populations; E. huxleyi cells averaged about 6-fold higher mean per cell SYTOX Green fluorescence in PI casts (Fig. 7f) above cells in early infection populations. Taken together, the levels of cellular NO, ROS, and death of E. huxleyi cells undergoing different stages of infection generally reflected the patterns observed in lab cultures (Fig. 1).

These diagnostic parameters were examined for three additional E. huxleyi populations (CTD 29, 40, and 89) that were outside of the aforementioned characterized water masses. An individual cast (CTD 92) from the collection of casts performed and characterized at EI1 with DNA- and lipid-based biomarkers was also included for comparison (Fig. 8; [12]). While not all biomarkers showed statistically significant differences, likely due to low sample size per station, trends in the data nonetheless suggest that these populations were in distinct phases of infection. CTD casts 29 and 40 appeared most similar to a late infection or post infection scenario, respectively, with high ROS, NO, and cell death signatures. Specifically, CTD cast 29 had median DAF-FM DA, CM-H2DCFDA, and SYTOX Green fluorescence values of 20.1, 22.4, and 25.8 RFU, respectively. CTD cast 40 had median DAF-FM DA, CM-H2DCFDA, and SYTOX Green fluorescence values of 14.1, 34.1, and 74.9 RFU, respectively. These casts also had high EhV-derived MCP copies E. huxleyi cell−1 (mean of 170 and 230 copies cell−1 for cast 29 and 40), and low host cell abundance (mean less than 450 cells ml−1). Cast 29 also had a high vGSL:sGSL ratio (mean ratio of 2.4 across all depths, with a log10 depth integrated inventory ratio of −0.042), further indicating active viral infection.

Fig. 8.

Gene- and fluorescence-based biomarkers for four additional CTD casts conducted during the NA-VICE cruise. a, b Box-and-whisker plots showing E. huxleyi cell abundance (cells ml−1) and EhV-derived MCP gene copies E. huxleyi cell−1 for these casts at three depths where E. huxleyi were present in highest abundance. c–e Box-and-whisker plots showing corresponding DAF-FM DA, CM-H2DCFDA, and SYTOX Green fluorescence for these casts. Data are an average of two replicates per depth. For all box plots, upper and lower bounds of the box represent the 25% and 75% quartiles around the median. Vertical lines extend to data points no greater than 1.5 times the inter-quartile range. Statistically significant differences were determined using one-way ANOVA with the Tukey HSD post hoc test (letters denote statistically different subgroups, p < 0.05)

On the other hand, E. huxleyi populations sampled at CTD casts 89 and 92 were characterized by lower ROS, NO, and cell death signatures. Cast 89 had median DAF-FM DA, CM-H2DCFDA, and SYTOX Green fluorescence values of 6.7, 12.9, and 5.6 RFU, respectively. CTD cast 89 also had moderate EhV-derived MCP copies (mean of 98 copies cell−1) and low cell abundance (mean of 460 cells ml−1), along with a much lower vGSL:sGSL ratio (mean ratio of 0.60 across all depths, with a log10 depth integrated inventory of −0.35). Cells at CTD cast 92 had the lowest comparative DAF-FM DA, CM-H2DCFDA, and SYTOX Green fluorescence with median values of 2.4, 10.7, and 1.9 RFU, respectively. These populations also had very low incidence of EhV-derived MCP (mean of only 8 copies cell−1) and high host cell abundance (~2000 cells ml−1).

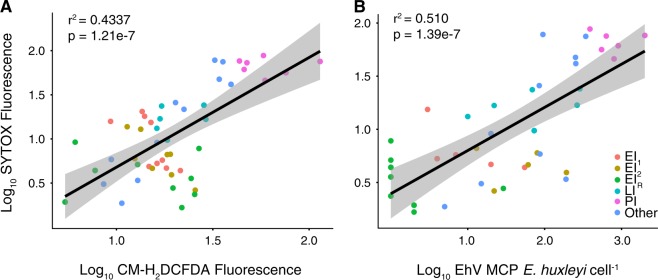

Relationships among these diagnostic stains across the cruise were explored using linear regression analysis. There was a significant positive correlation (r2 = 0.4337, p = 1.21e−7) between the levels of intracellular ROS and cell death (mean SYTOX fluorescence) in E. huxleyi cells across all CTD casts (Fig. 9a). In addition, there was a positive correlation (r2 = 0.510, p = 1.39e−7) between cell death and EhV-derived MCP copies E. huxleyi cell−1 (Fig. 9b). There were weak or non-significant relationships observed between intracellular NO and: intracellular ROS (r2 = 0.0696, p = 0.0266); cell death (r2 = −0.0049, p = 0.386); and EhV-derived MCP copies E. huxleyi cell−1 (r2 = −0.00684, p = 0.414) across the stations.

Fig. 9.

Linear regression analysis of various diagnostic parameters measured across the NA-VICE cruise. a Regression of log10-transformed mean SYTOX fluorescence vs. log10-transformed mean CM-H2DCFDA fluorescence. b Regression of log10-transformed EhV-derived MCP gene copy per E. huxleyi cell vs. log10-transformed mean SYTOX fluorescence. Shading indicates 95% confidence interval for the regression line

Discussion

The production of reactive oxygen species (ROS)—radical and non-radical molecules known to have toxic cellular effects such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), superoxide (O2.−), and the hydroxyl radical (HO.)—is a well-documented feature of lytic viral infection in E. huxleyi [16, 23, 25]. Unlike in host-pathogen systems of higher plants in which a ROS burst often occurs rapidly following pathogen invasion in order to prevent the spread of infection [47], cellular ROS production in the E. huxleyi-EhV system is not observed until late stages of infection occurring at the onset of lysis.These ROS, specifically H2O2, appear to be required for the induction of the PCD cascade in the host and subsequent cell lysis [25].

Little is known about the function of reactive nitrogen species, such as NO, in E. huxleyi physiology or in the emerging picture of the molecular pathways governing viral infection. Our previous work demonstrated that E. huxleyi cell lysates possess the ability to produce NO via nitrate reductase (NR) and hinted at the possibility of elevated NO production during infection [42]. It remains unclear, however, whether cellular nitrite levels reach sufficient concentrations during infection to drive NR-dependent NO production. Here, we demonstrate that enhanced intracellular NO production is a hallmark of viral infection in this species and does not occur simultaneously with the accumulation of ROS, indicating an independent function. Statistically significant differences in intracellular NO between infected and non-infected control cells were seen as early as 24 hpi, when there is ~2-fold higher DAF-FM DA fluorescence in infected cells. NO in cells remains elevated throughout the course of infection, relative to uninfected controls. Additionally, we detected an increase in extracellular NO in cultures during infection. These results provide an interesting framework for further exploring the role of NO in viral infection within a population. The ability of NO to act as a diffusible extracellular signal has been previously demonstrated in diatoms where it was shown to be a critical component in the stress perception of Phaeodactylum tricornutum [40]. Given our results, it is conceivable that NO produced during viral infection of E. huxleyi may serve a similar extracellular signaling role, possibly communicating infection to neighboring cells.

Both the early production and apparent requirement of NO for optimal viral production does suggest a potential cyto-protective role. NO has been shown in both plants and algae to have a broad antioxidant function, allowing cells to cope with various stressors that elicit ROS [48]. For example, NO has been implicated in the response of Chlorella vulgarus to copper stress [49], protection of Scenedesmus obliquus against H2O2 [50], and reduction of UV-B damage in the cyanobacterium Spirulina platensis [51]. Our findings show that NO may be responsible for similar antioxidant activity in E. huxleyi. Pre-treatment of cells with an NO donor increased survival upon subsequent challenge with H2O2, the main ROS produced during infection. Additionally, exogenously added NO led to an increase in the ability of E. huxleyi cell lysates to detoxify H2O2, a feature of cells also undergoing viral infection.

The antioxidant function of NO in early infected E. huxleyi supports previous observations of antioxidant changes that occur in this system. Sheyn et al. [25] showed that significant changes in the expression of antioxidant related genes and metabolites occur in the early stages of infection. Specifically, despite downregulation of some genes involved in ROS detoxification (such as ascorbate peroxidase and catalase) and upregulation of others, net H2O2 accumulation and cell death induction was not observed until late stages of the infection. E. huxleyi is also able to maintain high levels of both total and reduced glutathione pools [25], suggesting a maintenance of antioxidant capacity. Additionally, viral infection has been shown to induce production of the volatile organic sulfur compound dimethyl sulfide (DMS), along with its byproduct acrylic acid [52], both of which are believed to also have an antioxidant function [52, 53]. Therefore, there is evidence to support our observation that increased antioxidant function is a hallmark of infection, and we suggest that that NO may be crucial player in this induction.

Surprisingly, we observed a continued enhancement of cellular antioxidant capacity well into the late stages of infection, when oxidative stress and cell death became apparent. Previous work has demonstrated that prior exposure of the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and the dinoflagellate Peridinium gatunense to H2O2 increases both cellular antioxidant enzyme activity and the cell’s ability to detoxify ROS, but, paradoxically, it also increases sensitivity to subsequent sub-lethal doses of ROS [54]. This sensitivity has been attributed to accumulation of certain metabolites of antioxidant pathways during the initial stress, specifically the metabolite dehydroascorbate [54, 55], which acts as a stress-surveillance system. It is feasible that a similar mechanism occurs in E. huxleyi during viral infection, in which increased NO production and antioxidant capacity during the early stages of infection act to sensitize cells to oxidative stress and ROS-induced PCD later on.

The mechanism(s) by which NO production may lead to increased cellular antioxidant capacity in algae is unknown. However, work in plant systems suggest that a major mechanism of NO function is by post-translational modification of antioxidant proteins, particularly s-nitrosylation of cysteine residues [32]. For example, it has been shown that NO binds to the ascorbate peroxidase of Arabidopsis thaliana, upregulating its H2O2-scavenging activity during stress [56]. Other possible points of NO involvement during viral infection include regulation of metacaspases, the activity of which has been demonstrated to be essential for viral infection of E. huxleyi [10]. In Arabidopsis, for example, NO is a critical regulator of type-II metacaspase 9 [57]. Future work in the E. huxleyi-EhV system should explore potential host and/or viral proteins that are targets of NO-mediated post-translational modification in order to get a complete understanding of the role of NO in infection and the antioxidant changes that occur. Our observation that extracellular NO does not accumulate until 48 hpi (24 h after intracellular increases are seen) does point to the existence of intracellular NO sinks during infection.

Our findings also demonstrate NO production by naturally occurring E. huxleyi populations undergoing various stages of viral infection in the eastern North Atlantic [12, 13, 15]. These populations were characterized as either early, late, or post infection based on an array of diagnostic lipid (glycosphingolipid and betaine-like lipids) and gene-based (EhV-derived MCP) biomarkers, along with the abundance of host E. huxleyi [12, 15]. We were able to ground-truth the diagnostic stains used in our lab cultures in natural populations across a dynamic range of infection states. We observed that intracellular ROS production and cell death generally show similar trends in the field to those in laboratory (Fig. 1; [23–25]) and mesocosm [16] studies. Both are significantly elevated only in the post infection scenario where the abundance of replicating EhVs was high, E. huxleyi abundance was low, and lipid biomarkers indicated active infection. When all stations are taken together, a statistically significant linear relationship between cell death and intracellular ROS, as well as between cell death and EhV copy number, is observed, supporting multiple laboratory studies showing that the accumulation of ROS within cells occurs concurrently with initiation of cell death.

Patterns of intracellular NO in E. huxleyi at these stations also support our lab-based results. Elevated NO occured in relatively early infection and remains elevated in E. huxleyi cells encountered at both the late and post infection scenarios. We identified three distinct early infection phases where EhV-derived MCP copy number was low and E. huxleyi cell concentrations were high: EI1, EI2, and EIR. Populations at EI2 and EIR were characterized by elevated NO production relative to EI1. It may be that the populations sampled at the EI1 were early enough in infection that virus-induced NO production had not yet occurred, as illustrated by CTD cast 92.

Finally, data from additional casts reinforced the robustness and predictive power of the relationships that emerged between diagnostic stain data and other established biomarkers of viral infection. The combination of very low levels of cellular NO, ROS, death, virus-specific lipid signatures (vGSL:sGSL), and EhV-derived MCP copy numbers per E. huxleyi cell at CTD casts 89 and 92 was indicative infection was either in its beginning stages or was occurring at a low level at these two casts. Furthermore, the relatively high abundances of E. huxleyi cells found in CTD cast 92 further suggests that this was a relatively healthy bloom with little to no lytic viral infection occurring. E. huxleyi at CTD casts 29 and 40 were marked by relatively high levels of intracellular NO, ROS, and cell death in resident E. huxleyi populations. As expected, these populations showed strong evidence of a late or post stage viral infection with high virus-specific lipids (cast 29), high EhV-derived MCP reads, and low abundances of E. huxleyi.

Fluorescent dyes targeting cellular lipids have been previously used to quickly and efficiently diagnose viral infection in lab studies [24]. Our field observations suggest that NO production, determined through the DAF-FM DA staining, can also be a useful early indicator of the onset of lytic viral infection in natural E. huxleyi populations. NO can be assessed in real-time and its increase occurs prior to the emergence of other fluorescent signatures and biomarkers, many of which can only be analyzed on shore. Combined with classic and previously established infection biomarkers, fluorescent intracellular NO, ROS, and death indicators can provide an in situ, high-resolution assessment of the stage of lytic viral infection and physiological status of natural blooms.

Conclusion

Our work implicates the free radical NO as a crucial player in the molecular pathways governing the viral infection of E. huxleyi, distinct from ROS production. Furthermore, intracellular NO may have an antioxidant function, keeping ROS accumulation low so that viruses can replicate and assemble in a redox favorable environment. The application of an exogenous NO donor to E. huxleyi cultures enhanced survival in the face of subsequent H2O2 stress. Similarly, cultures undergoing infection and treated with a low dose of exogenous NO exhibited enhanced ability to detoxify H2O2. Additionally, the patterns of NO production, ROS production, and cell death seen in the laboratory were observed across a dynamic range of infection states for natural E. huxleyi populations sampled in the North Atlantic. Taken together, our culture studies and fieldwork demonstrate that the use of this suite of stains, along with classic lipid- and gene-based biomarkers, helps to more fully describe and diagnose viral infection status in natural E. huxleyi populations.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank K. Thamatrakoln and A. Kustka for feedback and fruitful discussion. We also thank the captain and crew of the R/V Knorr for their assistance during the NA-VICE. This work was funded by grants from the National Science Foundation (OCE-1061833 and OCE-1537951 to KBD) and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (GBMF#3301 to BASVM and GBMF#3789 to KDB).

Compliance with ethical standards

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41396-018-0325-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Brown CW, Yoder JA. Coccolithophorid blooms in the global ocean. J Geophys Res. 1994;99:7467–82. doi: 10.1029/93JC02156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holligan PM, Fernández E, Aiken J, Balch WM, Boyd P, Burkill PH, et al. A biogemical study of the coccolithophore, Emiliania huxleyi, in the North Atlantic. Glob Biogeochem Cycles. 1993;7:879–900. doi: 10.1029/93GB01731. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tyrrell T, Merico A. Emiliania huxleyi: bloom observations and the conditions that induce them. In: Thierstein HR, Young JR, editors. Coccolithophores: From Molecular Processes to Global Impact. Germany: Springer; 2004. pp. 75–97. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malin G, Steinke M. Dimethyl sulfide production: what is the contribution of the coccolithophores? In: Thierstein HR, Young JR, editors. Coccoltihophores: From Molecular Processes to Global Impact. Germany: Springer; 2004. pp. 127–64. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tyrrell T, Holligan PM, Mobley CD. Optical impacts of oceanic coccolithophore blooms. J Geophys Res. 1999;104:3223–41. doi: 10.1029/1998JC900052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klaas C, Archer DE. Association of sinking organic matter with various types of mineral ballast in the deep sea: Implications for the rain ratio. Glob Biogeochem Cycles. 2002;16:63-1--14. doi: 10.1029/2001GB001765. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bratbak G, Egge JK, Heldal M. Viral mortality of the marine alga Emiliania huxleyi (Haptophyceae) and termination of algal blooms. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1993;93:39–58. doi: 10.3354/meps093039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brussaard CPD, Kempers RS, Kop AJ, Riegman R, Heldal M. Virus-like particles in a summer bloom of Emiliania huxleyi in the North Sea. Aquat Microb Ecol. 1996;10:105–13. doi: 10.3354/ame010105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schroeder DC, Oke J, Malin G, Wilson WH. Coccolithovirus (Phycodnaviridae): characterisation of a new large dsDNA algal virus that infects Emiliana huxleyi. Arch Virol. 2002;147:1685–98. doi: 10.1007/s00705-002-0841-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bidle KD, Haramaty L, Barcelos ERJ, Falkowski P. Viral activation and recruitment of metacaspases in the unicellular coccolithophore, Emiliania huxleyi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:6049–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701240104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vardi A, Van Mooy BA, Fredricks HF, Popendorf KJ, Ossolinski JE, Haramaty L, et al. Viral glycosphingolipids induce lytic infection and cell death in marine phytoplankton. Science. 2009;326:861–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1177322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laber CP, Hunter JE, Carvalho F, Collins JR, Hunter EJ, Schieler BM, et al. Coccolithovirus facilitation of carbon export in the North Atlantic. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3:537–47. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lehahn Y, Koren I, Schatz D, Frada M, Sheyn U, Boss E, et al. Decoupling physical from biological processes to assess the impact of viruses on a mesoscale algal bloom. Curr Biol. 2014;24:2041–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinez JM, Schroeder DC, Larsen A, Bratbak G, Wilson WH. Molecular dynamics of Emiliania huxleyi and cooccurring viruses during two separate mesocosm studies. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:554–62. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00864-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheyn U, Rosenwasser S, Lehahn Y, Barak-Gavish N, Rotkopf R, Bidle KD, et al. Expression profiling of host and virus during a coccolithophore bloom provides insights into the role of viral infection in promoting carbon export. ISME J. 2018;12:704–13. doi: 10.1038/s41396-017-0004-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vardi A, Haramaty L, Van Mooy BAS, Fredricks HF, Kimmance SA, Larsen A, et al. Host-virus dynamics and subcellular controls of cell fate in a natural coccolithophore population. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:19327–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208895109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuhrman JA. Marine viruses and their biogeochemical effects. Nature. 1999;399:541–8. doi: 10.1038/21119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suttle CA. Marine viruses—major players in the global ecosystem. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:801–12. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frada MJ, Schatz D, Farstey V, Ossolinski JE, Sabanay H, Ben-Dor S, et al. Zooplankton may serve as transmission vectors for viruses infecting algal blooms in the ocean. Curr Biol. 2014;24:2592–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bidle KD, Vardi A. A chemical arms race at sea mediates algal host-virus interactions. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2011;14:449–57. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenwasser S, Mausz MA, Schatz D, Sheyn U, Malitsky S, Aharoni A, et al. Rewiring host lipid metabolism by large viruses determines the fate of Emiliania huxleyi, a bloom-forming alga in the ocean. Plant Cell. 2014;26:2689–707. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.125641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hunter JE, Frada MJ, Fredricks HF, Vardi A, Van Mooy BAS. Targeted and untargeted lipidomics of Emiliania huxleyi viral infection and life cycle phases highlights molecular biomarkers of infection, susceptibility, and ploidy. Front Marine Science. 2015;2.

- 23.Evans C, Malin G, Mills GP, Wilson WH. Viral Infection of Emiliania Huxleyi (Prymnesiophyceae) Leads to elevated production of reactive oxygen species. J Phycol. 2006;42:1040–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2006.00256.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez Martinez J, Poulton NJ, Stepanauskas R, Sieracki ME, Wilson WH. Targeted sorting of single virus-infected cells of the coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e22520. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheyn U, Rosenwasser S, Ben-Dor S, Porat Z, Vardi A. Modulation of host ROS metabolism is essential for viral infection of a bloom-forming coccolithophore in the ocean. ISME J. 2016;10:1742–54. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bidle KD. The molecular ecophysiology of programmed cell death in marine phytoplankton. Annu Rev Mar Sci. 2015;7:341–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-010213-135014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schatz D, Shemi A, Rosenwasser S, Sabanay H, Wolf SG, Ben-Dor S, et al. Hijacking of an autophagy-like process is critical for the life cycle of a DNA virus infecting oceanic algal blooms. New Phytol. 2014;204:854–63. doi: 10.1111/nph.13008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moncada S. Nitric oxide: discovery and impact on clinical medicine. J R Soc Med. 1999;92:164–9. doi: 10.1177/014107689909200402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gusarov I, Shatalin K, Starodubtseva M, Nudler E. Endogenous nitric oxide protects bacteria against a wide sprectrum of antibiotics. Science. 2009;235:1380–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1175439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martens-Habbena W, Qin W, Horak RE, Urakawa H, Schauer AJ, Moffett JW, et al. The production of nitric oxide by marine ammonia-oxidizing archaea and inhibition of archaeal ammonia oxidation by a nitric oxide scavenger. Environ Microbiol. 2015;17:2261–74. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mur LA, Mandon J, Persijn S, Cristescu SM, Moshkov IE, Novikova GV, et al. Nitric oxide in plants: an assessment of the current state of knowledge. AoB Plants. 2013;5:pls052. doi: 10.1093/aobpla/pls052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Begara-Morales JC, Sanchez-Calvo B, Chaki M, Valderrama R, Mata-Perez C, Padilla MN, et al. Antioxidant systems are regulated by nitric oxide-mediated post-translational modifications (NO-PTMs) Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:152. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Groß F, Durner J, Gaupels F. Nitric oxide, antioxidants and prooxidants in plant defence responses. Front Plant Sci. 2013;4:419. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Toledo JC, Jr, Augusto O. Connecting the chemical and biological properties of nitric oxide. Chem Res Toxicol. 2012;25:975–89. doi: 10.1021/tx300042g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frohlich A, Durner J. The hunt for plant nitric oxide synthase (NOS): is one really needed? Plant Sci Int J Exp Plant Biol. 2011;181:401–4. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Besson-Bard A, Pugin A, Wendehenne D. New insights into nitric oxide signaling in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2008;59:21–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar A, Castellano I, Patti FP, Palumbo A, Buia MC. Nitric oxide in marine photosynthetic organisms. Nitric oxide Biol Chem. 2015;47:34–9. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gallina AA, Brunet C, Palumbo A, Casotti R. The effect of polyunsaturated aldehydes on Skeletonema marinoi (Bacillariophyceae): the involvement of reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide. Mar Drugs. 2014;12:4165–87. doi: 10.3390/md12074165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vardi A, Bidle KD, Kwityn C, Hirsh DJ, Thompson SM, Callow JA, et al. A diatom gene regulating nitric-oxide signaling and susceptibility to diatom-derived aldehydes. Curr Biol: Cb. 2008;18:895–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vardi A, Formiggini F, Casotti R, De Martino A, Ribalet F, Miralto A, et al. A stress surveillance system based on calcium and nitric oxide in marine diatoms. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e60. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Z, Lin C, Liu C, Sun M, Ding H. The effect of nitric oxide on the growth of marine phytoplankton. J Ocean Univ Qingdao. 2003;2:185–8. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hirsh DJ, Schieler BM, Fomchenko KM, Jordan ET, Bidle KD. A liposome-encapsulated spin trap for the detection of nitric oxide. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;96:199–210. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brussaard CPD, Marie D, Bratbak G. Flow cytometric detection of viruses. J Virol Methods. 2000;85:175–82. doi: 10.1016/S0166-0934(99)00167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kojima H, Urano Y, Kikuchi K, Higuchi T, Hirata Y, Nagano T. Fluorescent indicators for imaging nitric oxide production. Angew Chem. 1999;38:3209–12. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19991102)38:21<3209::AID-ANIE3209>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cortese-Krott MM, Rodriguez-Mateos A, Kuhnle GG, Brown G, Feelisch M, Kelm M. A multilevel analytical approach for detection and visualization of intracellular NO production and nitrosation events using diaminofluoresceins. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53:2146–58. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fulton JM, Fredricks HF, Bidle KD, Vardi A, Kendrick BJ, DiTullio GR, et al. Novel molecular determinants of viral susceptibility and resistance in the lipidome of Emiliania huxleyi. Environ Microbiol. 2014;16:1137–49. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lamb C, Dixon RA. The oxidative burst in plant disease response. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1997;48:251–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li P, Liu CY, Liu H, Zhang Q, Wang L. Protective function of nitric oxide on marine phytoplankton under abiotic stresses. Nitric oxide Biol Chem. 2013;33:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh A, Sharma L, Mallick N. Antioxidative role of nitric oxide on copper toxicity to a chlorophycean alga, Chlorella. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2004;59:223–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mallick N, Mohn FH, Soeder CJ, Grobbelaar JU. Ameliorative role of ntiric oxide on H2O2 toxicity to a chlorophycean alga Scenedesmus obliquus. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 2002;48:1–7. doi: 10.2323/jgam.48.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xue L, Li S, Sheng H, Feng H, Xu S, An L. Nitric oxide alleviates oxidative damage induced by enhanced ultraviolet-B radiation in cyanobacterium. Curr Microbiol. 2007;55:294–301. doi: 10.1007/s00284-006-0621-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Evans C, Kadner SV, Darroch LJ, Wilson WH, Liss PS, Malin G. The relative significance of viral lysis and microzooplankton grazing as pathways of dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) cleavage: An Emiliania huxleyi culture study. Limnol Oceanogr. 2007;52:1036–45. doi: 10.4319/lo.2007.52.3.1036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sunda W, Kieber DJ, Kiene RP, Huntsman S. An antioxidant function for DMSP and DMS in marine algae. Nature. 2002;418:31–320. doi: 10.1038/nature00851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murik O, Kaplan A. Paradoxically, prior acquisition of antioxidant activity enhances oxidative stress-induced cell death. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:2301–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murik O, Elboher A, Kaplan A. Dehydroascorbate: a possible surveillance molecule of oxidative stress and programmed cell death in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. New Phytol. 2014;202:471–84. doi: 10.1111/nph.12649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang H, Mu J, Chen L, Feng J, Hu J, Li L, et al. S-nitrosylation positively regulates ascorbate peroxidase activity during plant stress responses. Plant Physiol. 2015;167:1604–15. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.255216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Belenghi B, Romero-Puertas MC, Vercammen D, Brackenier A, Inze D, Delledonne M, et al. Metacaspase activity of Arabidopsis thaliana is regulated by S-nitrosylation of a critical cysteine residue. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:1352–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608931200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.