Abstract

The purpose of this study was to explore and compare different countries in what motivated research participants’ decisions whether to share their de-identified data. We investigated European DIRECT (Diabetes Research on Patient Stratification) research project participants’ desire for control over sharing different types of their de-identified data, and with who data could be shared in the future after the project ends. A cross-sectional survey was disseminated among DIRECT project participants. The results found that there was a significant association between country and attitudes towards advancing research, protecting privacy, and beliefs about risks and benefits to sharing data. When given the choice to have control, some participants (<50% overall) indicated that having control over what data is shared and with whom was important; and control over what data types are shared was less important than respondents deciding who data are shared with. Danish respondents indicated higher odds of desire to control data types shared, and Dutch respondents showed higher odds of desire to control who data will be shared with. Overall, what research participants expect in terms of control over data sharing needs to be considered and aligned with sharing for future research and re-use of data. Our findings show that even with de-identified data, respondents prioritise privacy above all else. This study argues to move research participants from passive participation in biomedical research to considering their opinions about data sharing and control of de-identified biomedical data.

Subject terms: Ethics, Medical research

Introduction

International research consortia in the field of biomedicine collect large amounts of information consisting of different data types from participants that are often located in different countries. A key tenet that facilitates ongoing and future research is data sharing. Data sharing is viewed as good practice for advancing biomedical research, as it maximises the use of biological samples and other types of data, reduces participant burden, and stockpiling and pooling data helps to improve statistical power of research [1–3]. Data sharing within research consortia and externally is encouraged and is increasingly being adopted and enabled through advanced storing and sharing technologies. Supported by research data governance strategies, the optimisation of data sharing has been an important focus for the Open Science Agenda [4].

Empirical research to date has focused on three key areas: willingness of research participants and the public to share their data [5–8]; how to deliver broad informed consent to enable the sharing of data [9–12]; and patients’ happiness to share their own clinical data for research purposes [13–16]. Central to these studies has been the need to address privacy and confidentiality of data donors and any fear of data misuse. A balance, therefore, must be struck with permissions to use data for research. As more data is captured including genomic, phenotypic and other health-related data, safeguarding study participants’ privacy and confidentiality requires robust governance mechanisms.

Through ethical and legal standpoints, data protection and informed consent policies can support data sharing practice to avoid privacy mishaps. However, current mechanisms most commonly adopted in large consortia (such as a broad consent model) do not go far enough to address individual participants’ attitudes and perceptions about data sharing governance and practice [5, 12, 17–19]. Studies employing broad consent approaches regarding the release of de-identified data for future research may not be sufficiently ethical. There may be inconsistencies in the information provided at the time about how data may be shared and this approach further removes the ability for data donors to have control over what happens to their data after the end of the agreed research period [12, 15].

The question, therefore, arises as to how to design data governance that integrates study participants’ preferences, and the first step is to engage with them. Whilst some studies have explored the patient, public, and research participants’ perspectives about research consent types, preferences for how and who data should be shared with [9, 11, 12], to date, little is known about research participants’ views and preferences about how their biomedical, particularly genetic and phenotypic data from one research project should be shared for future and separate research [5].

While there is increasing recognition to engage and involve research participants in data governance plans in international consortia, studies highlighted here have largely been conducted in North America, with focus on hypothetical data sharing scenarios and improving broad consent at the initial stage of projects. Furthermore, the challenge in engaging research participants about the management of data sharing is compounded when international consortia collect data from people in different countries, where cultural and legal differences can affect readiness and ability to share data [5]. Differences in wanting or having control over data sharing also varies within diverse populations in relation to privacy concerns [1]. Participants in large consortia projects are often not consulted about their opinions on how their data should be governed during and after the end of the research project. Differences in attitudes and preferences between culturally dissimilar countries in Europe have been least studied, within the context of future research data sharing [5].

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate research participant’s beliefs about the importance of protecting their privacy, advancing research quickly and controlling future data sharing beyond the end of the research project with a subset of participants in four European countries enroled in the DIRECT (Diabetes Research on Patient Stratification) project.

Materials and methods

Study population and recruitment

Participants were sampled from a subset of those enroled in the DIRECT studies. In total 1082 participants attending follow-up appointments for other DIRECT studies at study centres in Denmark, Sweden, The Netherlands, and the UK were invited to complete the cross-sectional survey. The overall DIRECT project participant sample and recruitment is described in detail elsewhere [20, 21]. Study participants were eligible to take part in the survey if they were aged 18 years and older, of white European descent and able to consent to participate. This study was approved by institutional review boards in: Denmark (The Secretariat of the Scientific Ethics Committees for the Capital Region Protocol no. H-1-2011-166 Note no. 50965, and H-1-2012-100 Note no. 50694), Sweden (Regional Ethics Examination Board in Lund Dnr 2015/815 and Dnr 2015/843), The Netherlands (Medical Ethics Review Committee Vrije Universiteit Medical Centre Protocol 2012.222), and the UK (Newcastle and North Tynesside 1 Research Ethics Committee 12/NE/0132; East of Scotland Research Ethics Service 11/ES/0046; and 12/ES/0034).

Survey measures

Survey items analysed in this study were selected from a wider patient engagement survey that assessed: DIRECT participants’ willingness to participate in medical research; support for data sharing; preferences for control of different types of data; who data are shared with; and, preferences for future data sharing governance. Sociodemographic characteristics and self-reported knowledge of genetics and health status were also collected. The survey was developed with DIRECT diabetes clinicians, participants with Type 2 diabetes (T2D) and consortium researchers through iterative review and adjustment to question items [21].

Respondents were asked to assert their agreement on four statements measuring beliefs about whether it was important to advance research quickly, whether privacy should be protected, and whether respondents perceived that there were risks or benefits to sharing their genetic information [22]. The outcome variables assessed participants’ ratings of importance of which data are shared and with whom (importance of control), and were measured by the questions “How important is it that you decide what types of data are shared” and “How important is it that you decide who your data is shared with?”. The survey also measured respondents’ happiness to share different types of data. Similarly, respondents were asked to rate their happiness to share their de-identified data with different research groups. These items were treated as continuous explanatory variables. Participant characteristics were binary or categorical in nature. The explanatory variables were recoded into smaller categorical variables due to low numbers of responses in some categories, except the items measuring happiness to share different types of data and with different research groups, which were treated as continuous. The outcome variables were collapsed into binary variables for ease of interpretation.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated as frequencies and percentages, and Chi-Square tests for independence assessed associations between categorical variables. Univariate (see supplementary tables S2 and S3) and multivariate logistic regressions were conducted to assess which explanatory variables predicted the odds of importance for control over (1) types of data shared, and (2) who data are shared with. These outcome variables were binary (important versus not important). The continuous explanatory variables entered into the logistic regressions were the four items measuring beliefs and perceptions about data sharing, happiness to share different types of data and with whom data can be shared. Between-country differences were assessed in the multivariate logistic regressions adjusted for by all other variables (see Table 2). The multivariate logistic regressions were adjusted for by the categorical variables: age, gender, country, education level, self-rated knowledge of genetics, diabetes status, previously worked in health or medicine, and self-reported health (see Tables 3 and 4). All univariate and multivariate models contained complete cases, as not all respondents answered all of the questions and the minimal amount of cases were missing. All analyses were also stratified by country to assess associations within countries and compare findings. The logistic regression results are reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and significance level p < 0.05. The reference group in all regression models comparing the countries was the UK due to the largest number of responses received from this participant group. The analyses were performed using SPSS version 22 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Table 2.

Multivariate logistic regressions—differences between countries in importance for respondent’s to decide what data types are shared and who data is shared with (important versus not important a,b)

| UK | Denmark | Sweden | The Netherlands | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI | p | OR | CI | p | OR | CI | p | ||

| How important is it that you decide what types of data from this study are shared? (N = 49)c,d | ||||||||||

| REF | 0.85 | 0.44–1.63 | 0.625 | 0.70 | 0.35–1.40 | 0.314 | 0.64 | 0.38–1.10 | 0.106 | |

| How important is it that you decide who your data is shared with? (N = 747)c,d | ||||||||||

| REF | 0.93 | 0.47–1.85 | 0.838 | 0.92 | 0.44–1.93 | 0.819 | 0.68 | 0.38–1.23 | 0.201 | |

aAdjusted odds by: (categorical variables) diabetes diagnosis, gender, age, educational level, country, having ever worked in health or medical related job, self-rated health, and self-rated knowledge; (continuous variables) It is important to advance research quickly, It is important that my privacy is protected, There are benefits to sharing my genetic information, There are risks to sharing my genetic information, Happiness to share Medical history, Happiness to share Genetic information, Happiness to share Blood test results, Happiness to share Lifestyle information, and Happiness to share Personal information.

bREF: Not important

cQuestions collapsed from 5-point Likert Scale (Not at all important (1) to Extremely Important (5)); Respondents stating if they thought control over data sharing was ‘Not at all important’, ‘Fairly unimportant’ and ‘Neither important nor unimportant’ were grouped as ‘Not important’; those rating ‘Fairly important’ and ‘Extremely important’ were grouped as ‘Important’. The ‘I don’t know’ and ‘Prefer not to say’ options were treated as missing because of minimal or zero counts.

dComplete cases only, as not all respondents answered all questions

Table 3.

Multivariate Logistic regression—importance for respondent’s to decide what data types are shared (important versus not importanta,b)

| All Countries N = 749c | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI | p | |

| It is important to advance research quickly (Likert: 1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree) | 0.97 | 0.64–1.467 | 0.884 |

| It is important that my privacy is protected (Likert: 1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree) | 1.86 | 1.377–2.515 | <0.001 |

| There are benefits to sharing my genetic information (Likert: 1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree) | 1.26 | 0.835–1.912 | 0.269 |

| There are risks to sharing my genetic information (Likert scale: 1 = Strongly agree, 5 = Strongly disagree) | 0.82 | 0.669–1.006 | 0.057 |

| Happiness to share Medical history (Likert: 1 = Very unhappy to 5 = Very happy) | 1.01 | 0.605–1.671 | 0.982 |

| Happiness to share Genetic information (Likert: 1 = Very unhappy to 5 = Very happy) | 0.92 | 0.526–1.594 | 0.756 |

| Happiness to share Blood test results (Likert: 1 = Very unhappy to 5 = Very happy) | 1.77 | 0.850–3.687 | 0.127 |

| Happiness to share Lifestyle information (Likert: 1 = Very unhappy to 5 = Very happy) | 0.5 | 0.295–0.837 | 0.009 |

| Happiness to share Personal information (Likert: 1 = Very unhappy to 5 = Very happy) | 0.65 | 0.517–0.804 | <0.001 |

aAdjusted odds by: diabetes diagnosis, gender, age, educational level, country, having ever worked in health or medical related job, self-rated health, and self-rated knowledge

bREF: Not important

cComplete cases only, as not all respondents answered all questions

Table 4.

Multivariate logistic regression—importance for respondents to decide who data is shared with (important versus not importanta,b)

| All Countries N = 747c | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI | p | |

| It is important to advance research quickly (Likert: 1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree) | 1.22 | 0.772–1.915 | 0.398 |

| It is important that my privacy is protected (Likert: 1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree) | 2.26 | 1.627–3.142 | <0.001 |

| There are benefits to sharing my genetic information (Likert: 1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree) | 1.64 | 1.058–-2.555 | 0.027 |

| There are risks to sharing my genetic information (Likert scale: 1 = Strongly agree, 5 = Strongly disagree) | 0.74 | 0.594–0.915 | 0.005 |

| Happiness to share with Research teams in European universities (Likert: 1 = Very unhappy to 5 = Very happy) | 1.88 | 0.702–5.038 | 0.209 |

| Happiness to share with Research teams in universities around the world (Likert: 1 = Very unhappy to 5 = Very happy) | 0.34 | 0.131–0.86 | 0.023 |

| Happiness to share with Government funded organisations involved with health research (Likert: 1 = Very unhappy to 5 = Very happy) | 1.61 | 0.878–2.935 | 0.124 |

| Happiness to share with Commercial research companies (e.g. drug companies) (Likert: 1 = Very unhappy to 5 = Very happy) | 0.43 | 0.325–0.556 | <0.001 |

| Happiness to share with Charities involved in research (Likert: 1 = Very unhappy to 5 = Very happy) | 0.57 | 0.388–0.84 | 0.004 |

| Happiness to share with Patient organisations involved in research (Likert: 1 = Very unhappy to 5 = Very happy) | 1.55 | 0.985–- 2.44 | 0.058 |

aAdjusted odds by: diabetes diagnosis, gender, age, educational level, country, having ever worked in health or medical related job, self-rated health, and self-rated knowledge

b Reference = not important

cComplete cases only, as not all respondents answered all questions

Results

Sample characteristics

In total, 1082 DIRECT project participants were approached and 855 participated in the engagement survey from University research centres and Diabetes clinics in the four countries. The combined response rate for all countries was 79%. The majority (73%) of participants were aged 61 and over, 57% were male, 70% had been diagnosed with T2D, 60% had education qualifications above secondary school, and 20% had held a job related to health or medicine at some point in their career (Supplementary Table S1). Sixty-three per cent of 835 respondents rated their health as ‘very good’ or ‘good’ versus 30% rating it as ‘fair’. Forty-five per cent rated their knowledge of genetics as ‘fair’ versus 39% that rated it as either ‘poor’ or ‘very poor’.

Beliefs about research and privacy, and risk-benefit assessments to sharing data

Eighty-nine percent of respondents either strongly agreed or agreed that it is important to advance research as quickly as possible; however, all respondents were already participating in research as they had agreed to enrol onto a study within the DIRECT project. Seventy-seven per cent overall also agreed that protecting privacy was important to them, and this was consistent across all countries when stratified. The perception that there were benefits to sharing their genetic information for research was strongly agreed and agreed by 87% of respondents; in contrast, only 46% agreed that there were risks to sharing their genetic information. There were no other significant differences in respondents’ beliefs about privacy or advancing research, and benefits to sharing their data by knowledge of genetics. When stratified, country of origin was significantly associated with all belief statements except the importance of protecting privacy (Table 1), except importance over privacy where there was no significant change in proportions between countries.

Table 1.

Beliefs about advancing research and protecting privacy, and risk-benefits assessments to sharing genetic informationa,b

| UK | Denmark | Sweden | The Netherlands | Overall | p c | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| It is important to me to advance research as quickly as possible c | |||||||||||

| Strongly disagree and disagree | 5 | 1.2 | 4 | 1.5 | 1 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 1.2 | 0.04 |

| Neither disagree nor agree | 34 | 8.3 | 37 | 14.0 | 1 | 1.8 | 8 | 7.2 | 80 | 9.5 | |

| Strongly agree and agree | 370 | 90.5 | 223 | 84.5 | 53 | 96.4 | 103 | 92.8 | 749 | 89.3 | |

| It is important to me that my privacy is protected c | |||||||||||

| Strongly disagree and disagree | 24 | 6.0 | 18 | 6.8 | 4 | 7.1 | 7 | 6.3 | 53 | 6.4 | 0.495 |

| Neither disagree nor agree | 68 | 16.9 | 36 | 13.7 | 10 | 17.9 | 26 | 23.2 | 140 | 16.8 | |

| Strongly agree and agree | 310 | 77.1 | 209 | 79.5 | 42 | 75.0 | 79 | 70.5 | 640 | 76.8 | |

| There are benefits to sharing my genetic information c | |||||||||||

| Strongly disagree and disagree | 5 | 1.2 | 2 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 0.8 | <0.001 |

| Neither disagree nor agree | 23 | 5.6 | 43 | 16.3 | 7 | 13.0 | 30 | 27.5 | 103 | 12.3 | |

| Strongly agree and agree | 382 | 93.2 | 218 | 82.9 | 47 | 87.0 | 79 | 72.5 | 726 | 86.8 | |

| There are risks to sharing my genetic information c | |||||||||||

| Strongly agree and agree | 213 | 53.4 | 119 | 45.4 | 21 | 41.2 | 25 | 23.8 | 378 | 46.3 | <0.001 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 111 | 27.8 | 96 | 36.6 | 15 | 29.4 | 57 | 54.3 | 279 | 34.1 | |

| Strongly disagree and disagree | 75 | 18.8 | 47 | 17.9 | 15 | 29.4 | 23 | 21.9 | 160 | 19.6 | |

aLikert Scale responses collapsed due to small counts in extreme categories

bNot all respondents answered all questions

cPearson chi-square tests assessing association between countries and privacy and research attitudes, and beliefs about risks and benefits to sharing genetic information

Importance of control for participants to share data

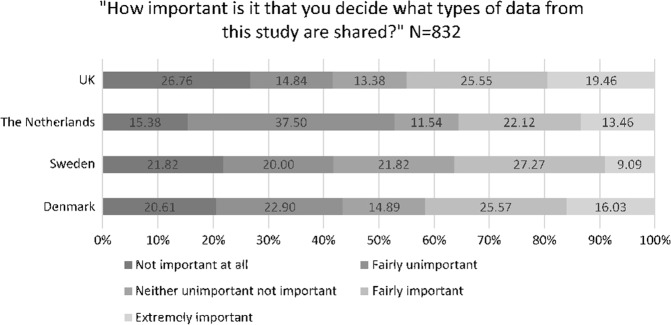

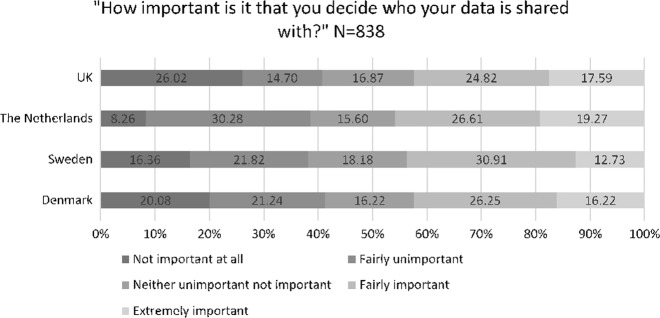

Forty-two percent of respondents rated having control of what types of data should be shared as either fairly or extremely important, and when stratified by country the results were: 41% in Denmark, 36% in Sweden, 36% in The Netherlands, and 45% in the UK (Fig. 1). However, after adjusting for all variables in the multivariate logistic regressions, none of the countries were significantly more or less likely to want control compared to the UK (see Table 4). Forty-three percent of respondents rated that having control over who their data is shared with was either fairly or extremely important to them, and by country the results were: 42% in Denmark, 44% in Sweden, 46% in The Netherlands, and 42% in the UK (Fig. 2). There were no significant differences in the importance of control for deciding who to share data with compared to the UK after adjusting for all other variables (see Table 4).

Fig. 1.

Importance of control over types of data shared from the DIRECT project

Fig. 2.

Importance of control over who data is shared with

Examining associations for importance for participants to control types of data shared

In univariate binary logistic regression models (Supplementary Table S2), our findings suggested that questions about: the importance of protecting privacy; beliefs that there are risks to sharing genetic information; and happiness to share: (a) genetic information, (b) blood test results, (c) lifestyle information, and (d) personal information, were all significant predictors of the importance of control. There were no significant differences between countries compared to the UK in whether deciding the types of data shared was important vs not important (supplementary Table S2).

The pooled country results (Table 3 and Supplementary Table S4) suggested that agreeing that it is important to protect privacy was significantly associated with beliefs concerning control over which data are shared (OR = 1.86, CI (1.38–2.51), p < 0.001). Happiness to share lifestyle and personal information were significantly associated with the importance to control which data are shared (OR = 0.5, CI (0.29–0.84), p < 0.01), and OR = 0.64, CI (0.52–0.80), p < 0.01), respectively. There were no other significant associations between the covariates and importance for control. When results were stratified by country, similar results were found in the Danish cohort, though results in the UK and Dutch cohorts did not reach significance. The sample size for the Swedish cohort was too small to compute the results for comparison (Supplementary Table S4).

Examining associations for importance for participants to control who data is shared with

Results from univariate logistic regressions found that importance of control was predicted by belief in protecting privacy, agreement that there are benefits to sharing genetic information, happiness to share with commercial companies and charities. This was consistent in the results stratified by country (Supplementary Table S3). The adjusted model showed that there was no significant association between country and importance of respondents to decide who data are shared with (Supplementary Table S5). Table 4 shows that increased importance for protecting privacy resulted in respondents being more likely to indicate that having control over data sharing was important (OR = 2.26, CI (1.67–3.1), p < 0.001). This was consistent across all countries, except Sweden, which did not yield significant results due to a very small sample (Supplementary Table S5). Respondents in all countries were 1.64 times significantly more likely to also indicate importance of control (data sharing) and believe that there were benefits to sharing their genetic information (p = 0.03). Disagreement that there were risks to sharing genetic information was associated with decreased likelihood for rating importance of control (OR = 0.74, CI (0.59–0.91), p < 0.01). Happiness to share data with commercial companies and charities was significantly associated with rating importance for control (OR = 0.43, CI (0.32–0.56), p < 0.01) and (OR = 0.57, CI (0.39–0.84), p < 0.01), respectively. These results were similar across countries, except Sweden where results were not significant.

Discussion

The current study aimed to assess desire for control for sharing data in relation to motivations (measured by attitudes/beliefs) about advancing research and protecting privacy, and willingness to share data. Where previous research has investigated improving informed consent through tiered choices [8, 12, 22], this study sought to obtain a more granular overview of study participants’ judgements about data sharing, and whether there were differences between individual participants across four European countries. When given the choice to have control, <50% indicated that having control over what data is shared and with whom was important.

The study findings suggest that control over what data types are shared was less important to respondents than deciding who data are shared with. The importance for control over de-identified data sharing found in this study is consistent with other research, which has highlighted that when data are de-identified, fewer respondents expect the need to have control in sharing of their data [14].

Whilst we found that overall desire for control of de-identified data was moderate (<50%), when assessing associations between happiness to share different data types and with research groups, importance for control varied with different options. How participants valued control over data sharing was associated with unhappiness to share data with global universities, commercial companies, and charities that conduct research. A report commissioned by the Wellcome Trust in the UK [23], found that willingness to share data is influenced by trust in the institution and the extent patients are informed about who their data are being shared with, and what aspects, particularly in relation to commercial entities [23]. Therefore, the desire for control over data sharing with particular types of organisations may reflect uncertainty of risks and benefits of sharing data with these groups. We did not investigate trustworthiness of different research groups; however, participants’ support for data sharing to advance research in this study is likely to be determined by the actions of researchers and data repositories, who will need to provide rationale for why data may be shared with separate research groups, particularly with the commercial sector [5]. Offering participants the choice about data sharing may develop trust in the research and researchers. D’Abramo et al. [8] found that attitudes to data sharing become restrictive when more information and options are provided about permitting data in biobanks to be publicly available. Similarly, McGuire et al. [12] reported that participants preferred having multiple data sharing options but were less likely to consent to public data release after being given options. Conversely, Bell et al. [18], having surveyed healthy people about hypothetical data sharing preferences, found that participants wanted to have control over uses of their data to varying degrees, including demographics, lab results, and sensitive information, such as mental health and genetic information. Participants were more willing to share data if they were given choices about what they wanted to share, and a high proportion wanted to know more about the public and private researchers requesting access to their data [18]. Whether the extent of control participants have over data shared affects future research participation requires further investigation.

Further cultural factors may affect preferences for control. Gaskell et al. [5] found that in their pan-EU study, willingness to participate in biobank research was affected by beliefs in risk of misuse of data, and public in southern European countries were less likely to participate than in north-western countries. The study reported here was specifically situated in Western Europe and involved high-income countries with good health systems and nations that are viewed as socially inclusive. Designing international consortia data governance would benefit from understanding cultural attributes, if research aims to be inclusive of participants in data sharing decision making. As these findings show, some aspects of data sharing are consistently agreed upon, such as importance of privacy, whereas others are not (differences between countries in deciding with whom it is acceptable to share data). Furthermore, differences found between countries in this study show the diversity of perspectives about data sharing in different populations. Danish respondents indicated higher odds of importance to control data types shared, and Dutch respondents showed higher odds of importance to control who data are shared with. This means that large consortia sourcing data from culturally diverse countries may find it challenging to consistently oversee how data are shared and managed for future research.

Maintaining privacy is central for governance of data sharing in research; results from this study show that privacy is key to the likelihood of wanting control over sharing data. However, there may be ambiguity in understanding what privacy means across different populations [24]. The discourse about privacy being important now needs to shift to how it can be facilitated and in what context data donors require control over data sharing. Lemke et al. [7] argued that participants wanted control over release of genetic information and that mechanisms to protect privacy needed to be provided. In consideration of this, it is ethically important to provide research participants with options to control sharing their study data, even after its anonymization. This could be facilitated by having simple mechanisms for choosing preferences, and further research about which (and how many) choices are needed, so as not to overburden participants [12]. With divergences in attitudes to control data sharing, how the availability of control mechanisms is facilitated will require addressing. The first step is for international consortia to communicate and engage with participants to assess preferences for data sharing [5, 11, 12, 25].

The importance to engage and involve study participants in research decisions is very timely. One proposed solution to facilitate participant engagement with future data sharing decisions is Dynamic Consent [26]. This approach provides participants with an electronic record of their consent decisions, which can be reviewed and updated at any time. This would allow those that wanted greater control to be more directly involved in real-time decision-making, and could potentially provide an infrastructure to support participants beyond the lifetime of a specific project [27]. Based on the findings of this study, this may be a relevant solution to manage future involvement, and thus would be appropriate to investigate further.

Strengths and limitations

This was a unique study in that it looked at participants already enroled in research to engage their views about how their data should be shared for future research. Few studies have investigated data sharing choices of patients from different countries in Europe. However, there are also a number of limitations that must be discussed. Firstly, the results are not generalisable to other patient or healthy populations or countries. Countries included were in the north-western region of Europe, and there may be marked differences in data sharing opinions with other European countries, and between non-white population groups. Due to the socio-demographic and personal characteristics, participation may have been influenced by already being enroled in DIRECT studies, and data sharing opinions referred to data that would be de-identified. In addition to this, the cross-sectional nature of the study design meant that it was difficult to ascertain whether respondents’ views would change over time and with more information about data sharing options, as we did not investigate the level of awareness respondents had about data sharing for future research. Also, collapsing the Likert survey questions from 5 to binary variables removes nuances in opinions of respondents about a given issue. Respondents’ views could potentially have been influenced by their level of confidence in the effectiveness of de-identification of their data in protecting privacy [14].

Conclusions

As it is responsible practice to obtain informed consent from participants to share their data [12], it should also be responsible practice to involve participants in decisions about how their data should be governed. Our findings indicate that what research participants expect in terms of control over data sharing needs to be considered and aligned with sharing for future research and re-use of data [2]. There is a balance to be struck between protecting privacy and benefits to biomedical research from data sharing [11, 17, 28]. Contributing to the data sharing governance literature, this study argues to move research participants from passive participation in biomedical research to considering their opinions about data sharing and control of de-identified biomedical data. Our findings show that even with de-identified data, respondents prioritise privacy above all else. However, this does not shut data sharing down, this is consistent across all countries investigated. Though some differences between countries in attitudes towards data sharing and need for control were found, it is important not to presume that participants do not wish to be kept informed about study procedures moving forward. These findings will aid the development of future data sharing policy for the DIRECT consortium. While this study was conducted prior to the introduction of the General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) in Europe, it aligned with the GDPR’s emphasis of understanding the preferences of those whose personal data is processed within the lens of privacy by design. While, consortia must adhere to regulatory governance; it can additionally develop specific data governance practices as appropriate through adopting evidence based and well-supported engagement and involvement guidelines and policies.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all of the teams in the consortium that assisted with the survey development, distribution, and collection, as well as the participants of the DIRECT project who participated in this study for their time. The work leading to this publication has received support from the Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint Undertaking under grant agreement no. 115317 (DIRECT), resources of which are composed of financial contribution from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) and EFPIA companies’ in-kind contribution.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41431-019-0344-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Kaufman DJ, Murphy-Bollinger J, Scott J, Hudson KL. Public opinion about the importance of privacy in biobank research. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85:643–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaufman D, Murphy J, Scott J, Hudson K. Subjects matter: a survey of public opinions about a large genetic cohort study. Genet Med. 2008;10:831–9. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31818bb3ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trinidad SB, Fullerton SM, Bares JM, Jarvik GP, Larson EB, Burke W. Genomic research and wide data sharing: views of prospective participants. Genet Med. 2010;12:486–95. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181e38f9e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Commission E Horizon 2020 Work Programme 2018–2020, 16. Science with and for Society.; 2018. http://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/data/ref/h2020/wp/2018-2020/main/h2020-wp1820-swfs_en.pdf. Accessed 25 July 2018.

- 5.Gaskell G, Gottweis H, Starkbaum J, et al. Publics and biobanks: Pan-European diversity and the challenge of responsible innovation. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21:14–20. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahm AK, Wrenn M, Carroll NM, Feigelson HS. Biobanking for research: a survey of patient population attitudes and understanding. J Community Genet. 2013;4:445–50. doi: 10.1007/s12687-013-0146-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lemke AA, Wolf WA, Hebert-Beirne J, Smith ME. Public and biobank participant attitudes toward genetic research participation and data sharing. Public Health Genom. 2010;13:368–77. doi: 10.1159/000276767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D’Abramo F, Schildmann J, Vollmann J. Research participants’ perceptions and views on consent for biobank research: a review of empirical data and ethical analysis. BMC Med Ethics. 2015;16:60. doi: 10.1186/s12910-015-0053-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanderson SC, Brothers KB, Mercaldo ND, et al. Public attitudes toward consent and data sharing in biobank research: a large multi-site experimental survey in the US. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;100:414–27. doi: 10.1016/J.AJHG.2017.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ewing Altovise T., Erby Lori A.H., Bollinger Juli, Tetteyfio Eva, Ricks-Santi Luisel J., Kaufman David. Demographic Differences in Willingness to Provide Broad and Narrow Consent for Biobank Research. Biopreservation and Biobanking. 2015;13(2):98–106. doi: 10.1089/bio.2014.0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGuire AL, Oliver JM, Slashinski MJ, et al. To share or not to share: a randomized trial of consent for data sharing in genome research. Genet Med. 2011;13:948–55. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182227589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGuire a L, Hamilton Ja, Lunstroth R, McCullough LB, Goldman a. DNA data sharing : Research participants’ perspectives. Genet Med J Am Coll Med Genet. 2008;10:46. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31815f1e00.DNA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Page SA, Manhas KP, Muruve DA. A survey of patient perspectives on the research use of health information and biospecimens. BMC Med Ethics. 2016;17:48. doi: 10.1186/s12910-016-0130-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riordan F, Papoutsi C, Reed JE, Marston C, Bell D, Majeed A. Patient and public attitudes towards informed consent models and levels of awareness of Electronic Health Records in the UK. Int J Med Inform. 2015;84:237–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim Katherine K, Joseph Jill G, Ohno-Machado Lucila. Comparison of consumers’ views on electronic data sharing for healthcare and research. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2015;22(4):821–830. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis C, Clotworthy M, Hilton S, et al. Public views on the donation and use of human biological samples in biomedical research: a mixed methods study. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003056. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haga SB, O’Daniel J. Public perspectives regarding data-sharing practices in genomics research. Public Health Genom. 2011;14:319–24. doi: 10.1159/000324705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bell EA, Ohno-Machado L, Grando MA. Sharing my health data: a survey of data sharing preferences of healthy individuals. AMIA Annu Symp Proc AMIA Symp. 2014;2014:1699–708. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trinidad SB, Fullerton SM, Ludman EJ, Jarvik GP, Larson EB, Burke W. Research ethics. Research practice and participant preferences: the growing gulf. Science. 2011;331:287–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1199000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koivula RW, Heggie A, Barnett A, et al. Discovery of biomarkers for glycaemic deterioration before and after the onset of type 2 diabetes: rationale and design of the epidemiological studies within the IMI DIRECT Consortium. Diabetologia. 2014;57:1132–42. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3216-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah N, Coathup V, Teare H, et al. Sharing data for future research—engaging participants’ views about data governance beyond the original project: a DIRECT Study. Genet Med. 2018:1. 10.1038/s41436-018-0299-7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Oliver JM, Slashinski MJ, Wang T, Kelly PA, Hilsenbeck SG, McGuire, et al. Balancing the risks and benefits of genomic data sharing: genome research participants’ perspectives. Public Health Genom. 2012;15:106–14. doi: 10.1159/000334718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MORI for Wellcome Trust I, Trust IM for W. The one-way mirror: public attitudes to commercial access to health data Report prepared for the Wellcome Trust. 2016.

- 24.Snell K, Starkbaum J, Lauß G, Vermeer A, Helén I. From protection of privacy to control of data streams: a focus group study on biobanks in the information society. Public Health Genom. 2012;15:293–302. doi: 10.1159/000336541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shabani Mahsa, Bezuidenhout Louise, Borry Pascal. Attitudes of research participants and the general public towards genomic data sharing: a systematic literature review. Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics. 2014;14(8):1053–1065. doi: 10.1586/14737159.2014.961917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaye J, Whitley EA, Lund D, Morrison M, Teare H, Melham K. Dynamic consent : a patient interface for twenty-first century research networks. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23:141–6. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Budin-Ljøsne I, Teare HJA, Kaye J, et al. Dynamic consent: a potential solution to some of the challenges of modern biomedical research. BMC Med Ethics. 2017;18:4. doi: 10.1186/s12910-016-0162-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vayena E, Gasser U. Between openness and privacy in genomics. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1001937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.