Abstract

Chronic stress promotes depression in some individuals, but has no effect in others. Susceptible individuals exhibit social avoidance and anxious behavior and ultimately develop depression, whereas resilient individuals live normally. Exercise counteracts the effects of stress. Our objective was to examine whether lactate, a metabolite produced during exercise and known to reproduce specific brain exercise-related changes, promotes resilience to stress and acts as an antidepressant. To determine whether lactate promotes resilience to stress, male C57BL/6 mice experienced daily defeat by a CD-1 aggressor, for 10 days. On the 11th day, mice were subjected to behavioral tests. Mice received lactate before each defeat session. When compared with control mice, mice exposed to stress displayed increased susceptibility, social avoidance and anxiety. Lactate promoted resilience to stress and rescued social avoidance and anxiety by restoring hippocampal class I histone deacetylase (HDAC) levels and activity, specifically HDAC2/3. To determine whether lactate is an antidepressant, mice only received lactate from days 12–25 and a second set of behavioral tests was conducted on day 26. In this paradigm, we examined whether lactate functions by regulating HDACs using co-treatment with CI-994, a brain-permeable class I HDAC inhibitor. When administered after the establishment of depression, lactate behaved as antidepressant. In this paradigm, lactate regulated HDAC5 and not HDAC2/3 levels. On the contrary, HDAC2/3 inhibition was antidepressant-like. This indicates that lactate mimics exercise’s effects and rescues susceptibility to stress by modulating HDAC2/3 activity and suggests that HDAC2/3 play opposite roles before and after establishment of susceptibility to stress.

Subject terms: Neuroscience, Molecular biology

Introduction

Major depressive disorder or depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide. The World Health Organization estimates that 320 million people suffer from this disease [1]. Antidepressants that target neurotransmitter systems are currently prescribed; however, less than half of the depressed patients achieve complete remission upon treatment [2]. Because of the limited efficacy of traditional antidepressants, there is an urgent need to identify novel cellular pathways involved in regulating susceptibility and resilience to stress. Interestingly, some individuals are more susceptible to depression, and the molecular mechanisms underlying this vulnerability are poorly understood. It is clear that genetic predisposition, aberrant changes in gene expression and environmental factors such as chronic stress are involved [3]. Recent work has focused on the epigenetic basis of mental illness and on the identification of epigenetic modulators that are responsible for the gene expression patterns that mediate susceptibility or resilience to stress [4]. Evidence suggests that histone acetylation has important roles in this context [5], with class I and class II histone deacetylases (HDAC) implicated in various aspects of depression. Indeed, brain region-specific infusion of HDAC inhibitors rescues depression phenotypes [6–9]. Interestingly, physical exercise counteracts the effect of chronic stress by inducing changes in gene expression in the brain through regulation of HDAC activity [10].

Exercise has many positive effects on brain physiology [11, 12]. It rescues many features of neurodegenerative disorders [13] and is linked to improved mental health [14, 15]. Chronic exercise induces antidepressant-like behavior in mice subjected to learned helplessness, forced swim, and tail suspension tests [16]. Moreover, voluntary exercise promotes resilience to chronic social defeat stress (CSDS) by inducing changes in gene expression in the nucleus accumbens [15]. These results in animals have been substantiated in human studies [17]. Hence, it is valuable to harness the therapeutic potential of exercise [18].

Exercise induces the production of metabolites such as β-hydroxybutyrate (DBHB) [10] and lactate that coordinate to mediate its positive effects on the brain. Lactate administration reproduces specific brain exercise-related changes [19]. Indeed, lactate promotes memory formation by maintaining normal synaptic function [20–22] and protects against ischemic stress [23]. In addition, lactate has antidepressant effects in a corticosterone-induced model of stress [24].

In this work, we tested the hypothesis that lactate promotes resilience to CSDS. We showed that lactate promotes resilience to stress by restoring normal levels and activity of the class I HDACs, HDAC2, and HDAC3. Our results reveal that the molecular pathways involved in establishing resilience to stress are distinct from those important for antidepressant effects after susceptibility is established. We also discovered that lactate can serve as an antidepressant after the establishment of the defeat phenotype. In this case, lactate mediates its effects by decreasing hippocampal levels of the class II HDAC, HDAC5 rather than affecting class I HDACs.

Materials and methods

Animal housing and lactate injections

Adult male C57BL/6 mice were housed in cages and divided according to the experimental groups: saline or lactate-receiving. Male mice were intraperitoneally injected with lactate (180 mg/kg) alone or in combination with the class I HDAC inhibitor, CI-994 (30 mg/kg) or with saline. The lactate dose used yields 20 mM lactate concentrations in the blood. This is consistent with both lactate plasma and hippocampal levels reported after exercise [25–28]. Animal care and use was in accordance with the guidelines and as approved by the ACUC.

Chronic social defeat stress (CSDS)

We performed the CSDS in mice, as previously described [29]. Briefly, the CSDS consisted of three stages. The first stage involved the screening and selection of aggressive CD-1 mice. The second stage comprised 10 days of CSDS sessions, during which experimental mice were exposed to social defeat by introduction to the compartment containing the aggressor mouse for 7 min, then transferred to the other compartment of the cage allowing only sensory interaction between the intruder and resident mouse. The third stage involved social behavioral testing on the eleventh day followed by animal sacrifice and tissue harvesting.

Social interaction test

The social interaction test was performed one day after the last defeat session as previously described [30]. Mice were habituated for 5 min in a cage containing three compartments with two compartments having a circular wire enclosure separated by an empty compartment. After habituation, a social stimulus C57BL/6J mouse was confined to one of the empty chambers and the experimental mouse was reintroduced to the cage in the central chamber. The experimental mouse was allowed to freely navigate between the different chambers and its movement was recorded with a camera. The time spent in each compartment was measured by the ANY-maze program. The total time spent by the mouse in the social compartment was divided by the total time spent in the non-social compartment and the mouse was considered susceptible if the ratio was <1 and resilient if the ratio was >1 [31]. Because the defeat groups included both susceptible and resilient animals, we chose to have a higher n number in the defeat and defeat + lactate groups to ensure having sufficient tissues for the biochemical analyses.

Elevated plus maze

The elevated plus maze (EPM), a validated test for anxiety [32], measures anxiety-like behaviors by using a cross apparatus to measure the time spent in the open vs. closed arms. Experimental mice were allowed to freely navigate the maze for 5 min. The time spent in the closed and open arms was recorded with a camera and measured by the ANY-maze program.

Open field

Each mouse was allowed to freely explore the open field for 5 min. The average distance traveled was recorded.

Immunoblot analyses

To determine protein levels, total cellular proteins were extracted by lysing the hippocampi in RIPA-B in the presence of protease inhibitors.

RNA extraction and real time PCR

Total RNA was prepared from hippocampi using the Rneasy Plus Mini RNA extraction kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Reverse transcription and real-time PCRs were performed using standard PCR protocol.

Statistical analysis

Unpaired t-test, one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by the Dunnett, Tukey, or Bonferroni post tests, respectively, were used to measure statistical significance. p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Lactate promotes resilience to chronic social defeat stress

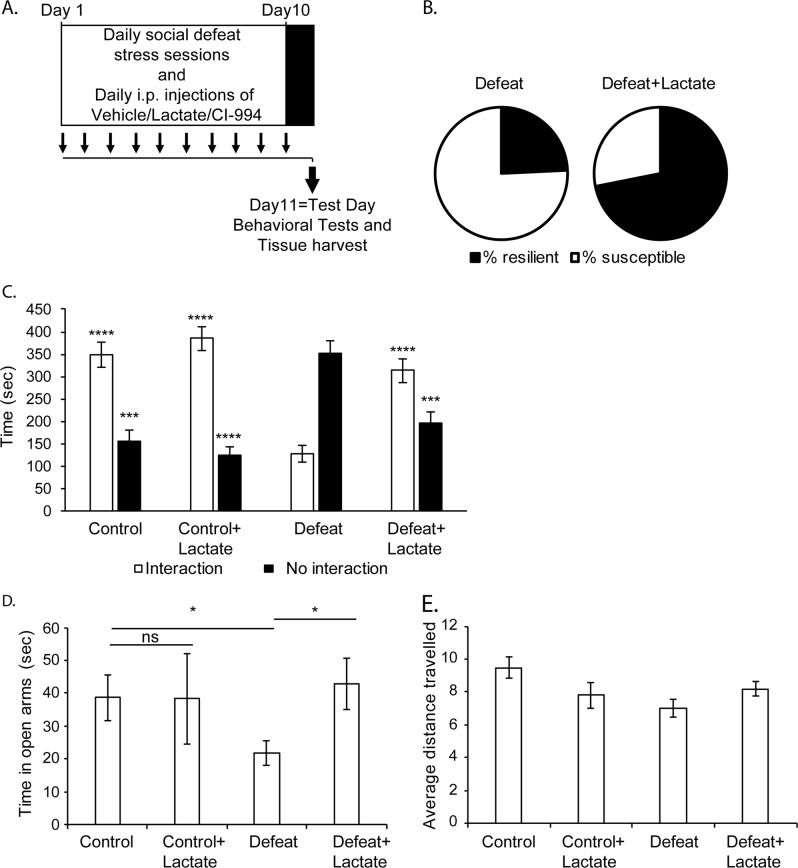

To determine whether lactate promotes resilience to stress, we subjected C57BL/6J male mice (6–7weeks) to a CSDS paradigm, a validated model of depression [33, 34]. For ten days, mice received intra-peritoneal injections of either vehicle or lactate. Four hours after each injection, mice were exposed to CSDS sessions followed by sensory contact with the aggressor, while control mice were only exposed to sensory contact with the resident mouse. This paradigm yields a depressed phenotype among the defeat group that can be reversed by the administration of antidepressants [9]. Twenty-four hours after the final defeat session, mice underwent social interaction testing to screen for susceptibility vs. resilience to stress (Fig. 1a). Previous work has established that mice exposed to CSDS can be divided into two distinct categories: susceptible mice characterized by social avoidance and anxiety behaviors, and resilient mice with wild-type social behaviors [33]. This sorting was based on the social interaction time of the mice with a social stimulus. When the ratio of the time spent in a chamber containing a social stimulus to the time spent in an empty chamber was greater than 1, the mouse was classified as resilient to stress. Our data showed that animals exposed to CSDS were split into 25 susceptible animals and 8 resilient animals. We found that lactate promotes resilience to stress since the percentage of resilient mice within the defeat group increased from 24% (8/33) in the defeat group receiving vehicle, to 72% (23/32) in the defeat group receiving lactate (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Lactate mediates resilience to chronic social defeat stress and rescues social avoidance behavior and anxiety. a The chronic social defeat paradigm consists of 10 days of daily defeat sessions that involve direct physical contact with an aggressor mouse for 7 min. On the 11th day, behavioral tests and tissue collection are conducted. Mice receive daily intra-peritoneal injections of either vehicle, lactate or the class I HDAC inhibitor, CI-994, 4 h before each defeat session. b Lactate increases resilience to stress. In the group of mice (n = 33) receiving saline and subjected to CSDS 24.2% are resilient to stress, whereas 75.8% are susceptible to stress. In the group of mice (n = 32) receiving lactate (180 mg/kg, daily for 10 days) and subjected to CSDS, 71.9% are resilient to stress, whereas 28.1% are susceptible to stress. c Intra-peritoneal injections of lactate (180 mg/kg, daily for ten days) reverse the chronic social defeat phenotype as shown by the increase in the time spent in interaction zone of the social interaction test. Statistical significance was measured by two-way Anova followed by multiple comparison test. Significance was measured vs. the defeat groups (Interaction: treatment F1,85 = 31.17, p < 0.0001 and stress F1,85 = 17.77, p < 0.0001; No interaction: treatment F1,85 = 19.61, p < 0.0001 and stress F1,85 = 9.008, p = 0.0035). ****p < 0.0001. The n numbers for the control, control + lactate, defeat (susceptible), and defeat + lactate are 15, 16, 25, and 32 respectively. d Intra-peritoneal injections of lactate decrease anxiety as measured by the significant increase in the time spent in the open arms of the elevated plus maze (EPM). Statistical significance was measured by unpaired t-test. Significance was measured vs. the defeat groups *p < 0.05. The n numbers for the control, control + lactate, defeat (susceptible), and defeat + lactate are 15, 16, 25, and 32, respectively. e The locomotor activity of all mice groups was not affected by lactate or defeat as measured by the distance traveled in the open field. Statistical significance was measured by one-way Anova followed by the Tukey’s multiple comparison test (F3,54 = 1.162, p = 0.3328)

Lactate enhances social interaction and decreases anxiety

In addition to promoting resilience to stress, lactate also enhanced social interaction. Defeat mice spent significantly less time interacting with the social stimulus as compared to the control groups receiving vehicle or lactate (Fig. 1c). This social avoidance behavior was reversed by lactate. Indeed, the average time spent interacting with the social stimulus was significantly higher in the defeat group receiving lactate as compared to the defeat group receiving vehicle (Fig. 1c). This confirms that lactate rescues the social behavior deficits induced by CSDS. Next, we assessed anxiety-like behaviors using the elevated plus maze (EPM). In the EPM, we measured the time spent exploring the open arms of the maze to assess the anxiety levels of the different mice groups. A significant decrease in the time spent exploring the open arms of the maze is indicative of anxious behavior. We found that defeat mice spent significantly less time in the open arms of the maze as compared to the control mice (Fig. 1d). This effect was reversed by lactate administration. Indeed, the time spent exploring the open arms of the maze by the defeat mice receiving lactate was comparable to control mice and significantly greater than that of the defeat mice receiving vehicle (Fig. 1d). Importantly, lactate treatment did not affect exploratory behavior of mice (Fig. 1e). Taken together, our data demonstrate that lactate rescues social deficits associated with CSDS and promotes resilience to stress. We next wanted to decipher the molecular mechanisms underlying the lactate-induced resilience to stress.

The resilient phenotype is associated with a decrease in class I HDACs (HDAC2 and HDAC3) protein levels in the hippocampus

Upon exposure to CSDS, multiple brain region-specific gene networks regulating susceptibility to stress have been deciphered [33, 35–37]. Consistent with these changes in gene expression patterns, many epigenetic modifications and modulators have been implicated in the progression of the CSDS. These modifications and modulators play unique roles in different brain regions (reviewed in refs. [4, 38]). For instance, the levels of acetylated histone H3 decrease in the amygdala during exposure to CSDS and amygdala-specific inhibition of the class I HDACs (HDAC1-3) by MS-275 rescues social behavior, but not sucrose preference [7]. In contrast, the levels of acetylated histone H3 increase in the hippocampus of mice during exposure to CSDS, but are restored to normal levels by the end of experimental paradigm [7]. Interestingly, hippocampal-specific inhibition of the class I HDACs by MS-275 only rescued sucrose preference, but not social behavior [7]. Because of the dynamics of the observed histone acetylation changes in the hippocampus, we focused on the role of class I HDACs in CSDS. First, we assessed HDAC1-3 and HDAC8 mRNA levels. Only HDAC3 mRNA levels were significantly reduced in the hippocampi of defeat mice, and we found that lactate restored these levels to normal (Fig. 2a). We next focused on determining whether class I HDAC protein levels are altered in the hippocampi of defeat mice. Specifically, we were interested in determining whether these HDAC proteins are differentially expressed in susceptible vs. resilient mice. For that reason, we compared the protein expression of class I HDACs in the hippocampi of susceptible and resilient mice. We found that only HDAC2 and HDAC3 protein levels were significantly decreased in the hippocampi of susceptible mice as compared to resilient mice (Fig. 2b–d). We observed no changes in hippocampal levels of HDAC1, HDAC5, or HDAC8 (Fig. 2e, f). These observed differences in HDAC2 and HDAC3 levels between susceptible and resilient mice correlated with changes in the expression of genes previously implicated in depression (Fig. 2g). We were next interested in determining whether lactate restores normal hippocampal HDAC2 and HDAC3 levels in mice exposed to CSDS.

Fig. 2.

The resilient phenotype is associated with increased hippocampal HDAC2 and HDAC3 protein levels as compared to the susceptible phenotype. a Real time RTPCR results showing that only Hdac3 mRNA expression is significantly decreased in the hippocampi of defeat animals as compared to control; whereas lactate restores normal Hdac3 mRNA expression. Statistical significance was measured by one-way Anova followed by the Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (F2,7 = 7.266, p < 0.05); defeat vs. control *p = 0.0270 and defeat vs. defeat + lactate *p = 0.0188. The n numbers for control, defeat, and defeat + lactate are 3, 3, and 4, respectively. No significant changes in Hdac1, Hdac2, Hdac5, or Hdac8 mRNA levels are observed. The n numbers for control, defeat and, defeat + lactate are 4, 4, and 4, respectively, for Hdac1, Hdac2, and Hdac8. The n numbers for control, defeat, and defeat + lactate are 8, 9, and 7, respectively, for Hdac5. b Representative western blot images depicting hippocampal HDAC2 and HDAC3 levels in susceptible vs. resilient mice. c Quantification of the HDAC2 western blots. Statistical significance was measured by unpaired t-test *p < 0.05. The n number of hippocampi analyzed is 9 for the susceptible and 10 for the resilient groups. d Quantification of the HDAC3 western blots. Statistical significance was measured by unpaired t-test *p < 0.05. The n number of hippocampi analyzed is 8 for the susceptible and 10 for the resilient groups. e Representative western blot images depicting hippocampal HDAC1, HDAC5, and HDAC8 levels in susceptible vs. resilient mice. f Quantification of the HDAC1, HDAC5, and HDAC8 western blots. Statistical significance was measured by one-way Anova followed by the Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (HDAC1: F2,5 = 8.63766, p = 0.0239; susceptible vs. control p = 0.1251 and susceptible vs. resilient p = 0.1457; HDAC5: F2,6 = 5.065, p = 0.0515; susceptible vs. control p = 0.2845 and susceptible vs. resilient p = 0.2480; HDAC8: F2,6 = 0.9725 p = 0.4307; susceptible vs. control p = 0.9822 and susceptible vs. resilient p = 0.3920). The n number of hippocampi analyzed is 8 for the susceptible and 10 for the resilient groups. g Real time RTPCR results show that the expression of the histone methyltransferase G9a, the NMDA receptor subunit Grin2a and the immediate early gene Arc mRNA is significantly decreased in the hippocampi of resilient mice as compared to susceptible mice. G9a was previously shown to be involved in cocaine-induced vulnerability to stress in the nucleus accumbens [44]. Grin2 was found to be involved in mood related disorders [45, 46]. Statistical significance was measured by t-test (G9a: p = 0.05, Grin2a: p = 0.047 and Arc: p = 0.038). The n number of hippocampi analyzed is 3

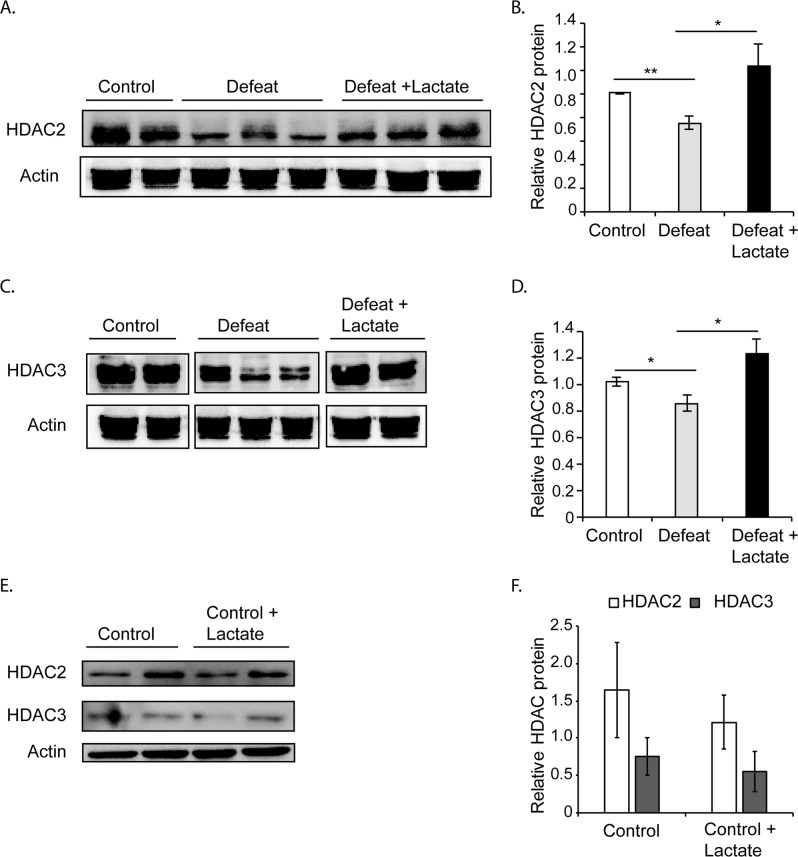

Lactate restores control HDAC2 and HDAC3 protein levels in the hippocampi of mice exposed to CSDS

Lactate treatment alters the protein levels of class I HDACs. As expected, western blot analysis revealed that HDAC2 and HDAC3 expression levels were significantly decreased in the hippocampi of defeat mice receiving vehicle as compared to the hippocampi of control mice (Fig. 3a–d). Interestingly, lactate restores normal levels of these HDACs (Fig. 3a–d) and does not increase the baseline levels of HDAC2 or HDAC3 (Fig. 3e, f). Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that a decrease in hippocampal class I HDAC levels correlates with susceptibility to stress, and that lactate can potentially promote resilience by restoring normal HDAC2/HDAC3 levels and activity in the hippocampus. We next tested this hypothesis.

Fig. 3.

Lactate restores hippocampal protein levels of HDAC2 and HDAC3 in mice exposed to CSDS. a Representative western blot images depicting hippocampal HDAC2 levels in control, defeat, and defeat + lactate mice. Mice exposed to CSDS have lower levels of hippocampal HDAC2 vs. control. Daily intra-peritoneal injections (180 mg/kg, daily for 10 days) of lactate restored HDAC2 protein levels. b Quantification of the HDAC2 western blots. Statistical significance was measured by 1way Anova followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (F2,11 = 4.316, p = 0.0413). Significance was measured vs. defeat **p < 0.01 and *p < 0.05. The n number of hippocampi analyzed is 4 for control, 5 for defeat, and 5 for the defeat + lactate groups, respectively. c Representative western blot images depicting hippocampal HDAC3 levels in control, defeat, and defeat + lactate mice. Mice exposed to CSDS have lower levels of hippocampal HDAC3 vs. control. Daily intra-peritoneal injections (180 mg/kg, daily for 10 days) of lactate-restored HDAC3 protein levels. d Quantification of the HDAC3 western blots. Statistical significance was measured by one-way Anova followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (F2,12 = 5.342, p = 0.0219). Significance was measured vs. defeat *p < 0.05. The n number of hippocampi analyzed is 5 for control, 5 for defeat, and 5 for the defeat + lactate groups, respectively. e Representative western blot images depicting hippocampal HDAC2 and HDAC3 levels in control and control + lactate mice. f Quantification of the HDAC2/HDAC3 western blots

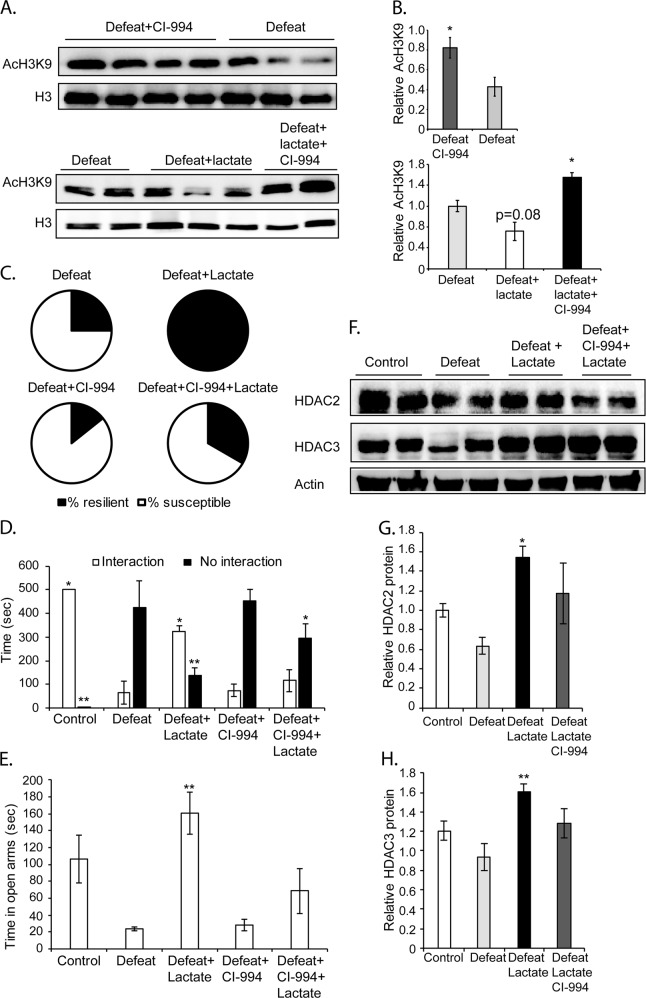

Lactate promotes resilience to stress by restoring HDAC2 and HDAC3 protein levels and deacetylase activity

In order to test whether lactate promotes resilience to stress by restoring HDAC2 and HDAC3 levels and activity, we decided to assess the effect of a combinatorial treatment of lactate and a selective class I HDAC inhibitor (HDACi), CI-994, on social behavior in response to CSDS. CI-994 is a benzamide-based HDACi that is brain-permeable and that targets both HDAC2 and HDAC3. Intra-peritoneal injections of 30 mg/kg CI-994 result in long-lasting levels of the compound in the brain and do not affect baseline behavior [39, 40]. Indeed, we found that intra-peritoneal injections of CI-994 either alone or when combined with lactate induce a significant increase in histone H3 lysine 9 (K9) acetylation in the hippocampus (Fig. 4a, b). This supports the observations that the compound reaches the hippocampus and induces changes in gene expression due to class I HDACi [39]. Consistent with our previous observations that lactate restores hippocampal HDAC2/3 levels, we also found that intra-peritoneal injections of lactate induce a decrease in histone H3K9 acetylation (Fig. 1a, b). We next assessed the effect of class I HDAC inhibition on lactate-mediated resilience to stress. In these experiments, mice received daily injections of vehicle, lactate, CI-994 or lactate + CI-994. Four hours after the injections, the mice were exposed to CSDS. We found that as expected, 75% (3/4) of animals exposed to CSDS were susceptible to stress. Lactate promoted resilience to stress. 100% (5/5) of the mice exposed to CSDS and receiving lactate were resilient to stress. CI-994 failed to promote resilience to stress. Only 14% (1/7) of the mice exposed to CSDS and receiving CI-994 were resilient to stress. Interestingly, when combined together, CI-994 attenuated lactate’s ability to promote resilience to stress. Indeed, 33% (2/6) of the mice exposed to CSDS and receiving CI-994 + lactate were resilient (Fig. 4c). Taken together, these experiments suggest that lactate mediates resilience to stress by restoring HDAC2/3 levels and importantly their deacetylase activity. We were next interested in assessing the social interaction and anxiety behaviors of the mice receiving the combined treatment. Both CI-994 and the combined treatment did not significantly rescue social avoidance phenotypes (Fig. 4d), nor anxiety behaviors (Fig. 4e). Indeed, no increase in the time spent interacting with the social stimulus was observed in mice exposed to CSDS and receiving either treatment (Fig. 4d). In addition, these mice also failed to explore the open arms of the EPM (Fig. 4e). These results support the hypothesis that lactate mediates its effects on social interaction and anxiety by restoring hippocampal HDAC2/3 levels and activity. Indeed, restoring hippocampal HDAC2/3 protein levels only is not sufficient for rescuing the behavioral deficits induced by CSDS. This is supported by the observation that lactate alone or in combination with CI-994 can restore hippocampal HDAC2/3 protein levels (Fig. 4f–h). As a result, the failure to rescue these activities in the combined treatment is due to the ability of CI-994 to inhibit deacetylase enzymatic activity. Taken together, our results suggest that lactate mediates resilience to stress and rescues social deficits induced by CSDS by restoring hippocampal HDAC2/3 levels and deacetylase activity.

Fig. 4.

Lactate promotes resilience and rescues social behavior in mice exposed to CSDS by restoring HDAC2 and HDAC3 protein levels and deacetylase activity. a The brain-permeable class I HDACi, CI-994, induces acetylation of histone H3 lysine (K)9 levels. Lactate treatment decreases acetyl histone H3K9 levels in defeat mice as compared to defeat, whereas the combined treatment of lactate + CI-994 significantly increases acetyl histone H3K9 level. Representative western blot images depicting hippocampal acetyl histone H3K9 levels in defeat and defeat + CI-994 mice as well as in defeat, defeat + lactate, and defeat + lactate + CI-994 mice. b Quantification of the acetyl histone H3K9 western blots. Statistical significance was measured by the unpaired t-test. Significance was measured vs. defeat *p < 0.05. The n of hippocampi analyzed are 3 for defeat, 3 for defeat + lactate, 3 for defeat + lactate + CI-994, and 4 for the defeat + CI-994 groups, respectively. c The lactate-mediated increases in resilience to stress are dependent on class I HDAC activity. In the group of mice (n = 4) receiving saline and subjected to chronic social defeat stress, 25% are resilient to stress, whereas 75 % are susceptible to stress. In the group of mice (n = 5) receiving lactate (180 mg/kg, daily for ten days) and subjected to CSDS, 100% are resilient to stress. In the group of mice (n = 7) receiving CI-994 (30 mg/kg, daily for 10 days) and subjected to CSDS, 14.3% are resilient to stress, whereas 85.7 % are susceptible to stress. In the group of mice (n = 6) receiving the combined lactate (180 mg/kg, daily for ten days) and CI-994 (30 mg/kg, daily for 10 days) treatment and subjected to CSDS, 33.3% are resilient to stress, whereas 66.7 % are susceptible to stress. Even though the n number for control, defeat, defeat + lactate is relatively low, these experiment follow the same paradigm as Fig. 1c and show identical results. We opted not to compile these experiments together and include only the animals that were subjected to chronic social defeat stress at the same time as the CI-994 or combined treatments. The results with the CI-994 and the combined treatment were conclusive even with the n = 7 and 6, respectively, and did not warrant further increases in the number of animals. d Intra-peritoneal injections of the combined lactate and CI-994 treatment fail to reverse the chronic social defeat phenotype. This is shown by non-significant change in the time spent in interaction zone of the social interaction test by this group (defeat + lactate + CI-994) as compared to defeat mice. CI-994 on its own was also unable to rescue social avoidance, whereas, as expected, lactate reversed it. Statistical significance was measured by one-way Anova followed by Dunnet’s multiple comparison test (interaction: F4,17 = 4.935, p = 0.008; no interaction: F4,17 = 8.625, p = 0.0005). Significance was measured vs. the defeat groups. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. The n numbers for the control, defeat, defeat + lactate, defeat + CI-994, and defeat + lactate + CI-994 are 3, 3, 5, 7, and 7, respectively. e Intra-peritoneal injections of the combined lactate and CI-994 treatment fails to rescue anxious behavior as measured in the EPM. This is shown by non-significant change in the time spent in the open arms of the EPM by this group (defeat + lactate + CI-994) as compared to defeat mice (p = 0.4624). CI-994 on its own was also unable to rescue anxiety, whereas as expected lactate reversed it. Statistical significance was measured by one-way Anova followed by Dunnet’s multiple comparison test (F4,19 = 7.473, p = 0.0009). Significance was measured vs. the defeat groups. **p < 0.01. The n numbers for the control, defeat, and defeat + lactate, defeat + CI-994, and defeat + lactate + CI-994 are 3, 3, 6, 7, and 6, respectively. f Lactate restores hippocampal HDAC2 and HDAC3 protein levels even when administered with CI-994. Representative western blot images depicting hippocampal HDAC2 and HDAC3 levels in control, defeat, defeat + lactate, and defeat + lactate + CI-994 mice. Mice exposed to CSDS have lower levels of hippocampal HDAC2/HDAC3 vs. control. Daily intra-peritoneal injections of lactate or lactate + CI-994 restored hippocampal HDAC2/HDAC3 protein levels. g Quantification of the HDAC2 western blots. Statistical significance was measured by one-way Anova followed by Dunnet’s multiple comparison test (F3,12 = 2.838, p = 0.0828). Significance was measured vs. defeat *p < 0.05. The n of hippocampi analyzed are 4 for each group. h Quantification of the HDAC3 western blots. Statistical significance was measured by one-way Anova followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (F3,12 = 5.256, p = 0.0151). Significance was measured vs. defeat **p < 0.01. The n of hippocampi analyzed are 4 for each group

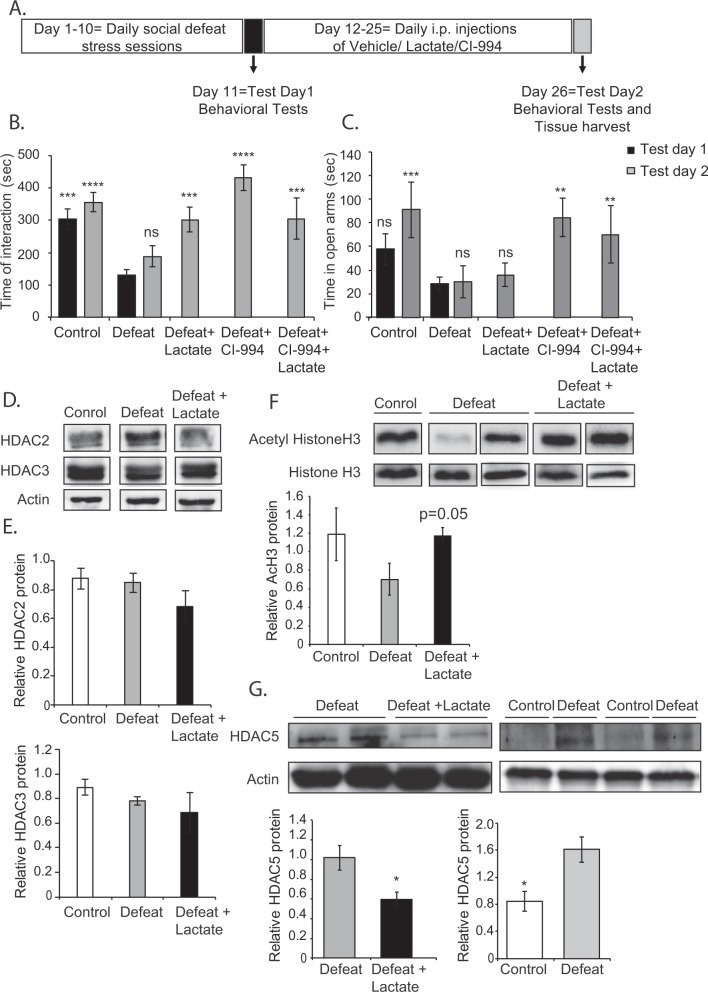

Lactate exhibits antidepressant-like effects by rescuing social avoidance associated with depression

We were next interested in assessing whether lactate has an antidepressant effect, and whether this effect is mediated by class I HDACs. To assess the antidepressant role of lactate, we modified the previously described CSDS paradigm (Fig. 5a). The modified paradigm consisted of ten daily CSDS sessions; however, no treatments were administered to the experimental mice. On the eleventh day, the mice exposed to CSDS were divided into susceptible and resilient groups based on the social interaction ratio calculated on day 11 (test day 1). Susceptible mice were divided into four groups that received intra-peritoneal injections of either vehicle, lactate (180 mg/kg), CI-994 (30 mg/kg) or a combination of lactate and CI-994 for an additional 13 days. These treatments were followed with behavioral tests on day 26 (test day 2) (Fig. 5a). In order to investigate the potential antidepressant effect of each treatment, we compared the social behavior phenotypes of each group in test day 1 and test day 2. As expected, mice subjected to CSDS spent significantly less time interacting with the social stimulus (Fig. 5b). On test day 2, mice that received vehicle treatment continued to exhibit social avoidance behavior, whereas mice receiving lactate, CI-994 or the combined treatment recovered and spent significantly more time interacting with the social stimulus (p < 0.001, p < 0.0001, and p < 0.001, respectively) (Fig. 5b). Interestingly, these compounds did not show similar effects when tested for their ability to rescue anxiety. CI-994 treatment significantly rescued anxiety. Indeed, mice receiving CI-994 alone or in combination with lactate spend significantly more time exploring the open arms of the EPM (p < 0.01) (Fig. 5c). Lactate, on the other hand, was unable to rescue this behavior (Fig. 5c). Further behavioral tests may be needed to fully substantiate that lactate is not anxiolytic. Our results suggest that both lactate and CI-994 have antidepressant-like effects with CI-994 being a more potent antidepressant and anxiolytic. These results suggest that the molecular pathways engaged by lactate to promote resilience to stress are different from those engaged by lactate to reverse the depression phenotype once susceptibility is established. For this reason, we decided to further investigate the antidepressant mechanism of action of lactate.

Fig. 5.

Lactate is an antidepressant that can rescue social avoidance phenotypes after their establishment. As an antidepressant, lactate increases hippocampal acetyl histone H3 and decreases hippocampal HDAC5 protein levels. a Modified chronic social defeat paradigm to assess the therapeutic potential of the compounds. This paradigm comprises of 10 days of daily defeat sessions that involve direct physical contact with an aggressor mouse for 7 min. On day 11, behavioral tests (test day 1) are conducted. During the 10 days of CSDS, mice do not receive any compound. From days 12–25, mice receive daily intra-peritoneal injections of either vehicle, lactate (180 mg/kg), CI-994 (30 mg/kg) or lactate + CI-994. On day 26, behavioral tests (test day 2) are conducted and tissue is collected. b Lactate rescues established defeat/depressed phenotype. Mice continue to exhibit social avoidance phenotype on test day 2 (day 26). No significant change is observed in the time of interaction between defeat groups on test day 1 and 2 (p = 0.8249). Intra-peritoneal injections of lactate (180 mg/kg), CI-994 (30 mg/kg), and lactate + CI-994, daily from days 12–25 reverse the chronic social defeat phenotype as shown by the significant increase on test day 2 in the time spent in interaction zone of the social interaction test as compared to the time spent there by the defeat group (test day 1 and 2). Statistical significance was measured by one-way Anova followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (F6,70 = 13.01, p < 0.0001). Significance was measured vs. the defeat groups. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ****p < 0.0001. The n numbers for the control (test day 1), control (test day 2), defeat (test day 1), defeat (test day 2), defeat + lactate (test day 2), defeat + CI-994 (test day 2), and defeat + lactate + CI-994 (test day 2) are 8, 8, 30, 6, 8, 8, and 8, respectively. c Lactate fails to rescue the established anxiety phenotype. Mice continue to exhibit anxious behavior on test day 2 (day 26). No significant change is observed in the time spent exploring the open arms of the EPM between defeat groups on test day 1 and 2 (p = 0.9998). Daily intra-peritoneal injections of lactate (180 mg/kg) from days 12–25 failed to rescue anxiety phenotypes; on the other hand, intra-peritoneal injections CI-994 (30 mg/Kg) were anxiolytic as shown by the significant increase on test day 2 in the time spent exploring the open arms of the EPM compared to the time spent there by the defeat group (test day 1 and 2). The combined treatment of lactate and CI-994 also significantly rescued anxiety. Statistical significance was measured by one-way Anova followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (F6,59 = 5.49, p = 0.0001). Significance was measured vs. the defeat groups. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ****p < 0.0001. The n numbers for the control, defeat, defeat + lactate, defeat + CI-994, and defeat + lactate + CI-994 are 5, 21, 6, 5, and 5, respectively. d Representative western blot images depicting hippocampal HDAC2 and HDAC3 levels in control, defeat, and defeat group receiving lactate from days 12–25. e Quantification of the HDAC2 and HDAC3 western blots. Statistical significance was measured by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-test. The n number of hippocampi analyzed is 4. f Representative western blot image depicting hippocampal acetyl histone H3 levels in control, defeat, and defeat group receiving lactate from days 12–25. Quantification of the acetyl histone H3 western blots. Statistical significance was measured by unpaired t-test. The n number of hippocampi analyzed is 4. g Representative western blot images depicting hippocampal HDAC5 levels in control, defeat, and defeat group receiving lactate from days 12–25. Quantification of the HDAC5 western blots. Statistical significance was measured by unpaired t-test. *p < 0.05. The n number of hippocampi analyzed is 3 for the control, 6 for the defeat group, and 5 for the defeat + lactate group

Lactate treatment after depression establishment does not affect class I HDAC protein levels

We assessed the protein levels of HDAC2/3 in the hippocampus in response to lactate antidepressant treatment (Fig. 5a). We found that HDAC2 and HDAC3 protein levels were similar in control mice vs. defeat/depressed mice receiving either vehicle, or lactate (Fig. 5d, e). This suggests that once susceptibility to stress is established, hippocampal class I HDAC protein levels normalize. This is consistent with our finding that CI-994 has antidepressant effects when administered after susceptibility to stress is established. Taken together, our data are consistent with the hypothesis that HDAC2/3 activity mediates lactate’s ability to promote resilience to stress, but may be dispensable for its antidepressant activity.

Lactate treatment after depression establishment promotes pan-histone H3 acetylation and decreases HDAC5 levels

Considering that our results with CI-994 suggest that systemic delivery of brain-permeable class I HDAC inhibitors has antidepressant effects, we decided to assess whether lactate treatment also affects histone acetylation. We found that lactate treatment after depression establishment induces increases in hippocampal pan-histone H3 acetylation (Fig. 5f). This was of particular relevance because class I HDAC inhibition is usually associated with acetylation of histone H3K9 and not pan-histone H3 acetylation [39]. These results raised the possibility that lactate mediates its antidepressant effects by modulating the expression or activity of another class of HDACs. Interestingly, hyperacetylation of hippocampal histones has also been observed after chronic imipramine treatment and has been associated with a selective downregulation of the class II HDAC5 [9]. Furthermore, viral-mediated HDAC5 overexpression in the hippocampus blocked imipramine’s ability to reverse depression-like behavior [9]. Since lactate treatment induced hyperacetylation of hippocampal histones without affecting class I HDAC levels, we decided to test whether lactate, like imipramine, alters hippocampal protein levels of HDAC5. We found that indeed lactate also reduces hippocampal HDAC5 levels (Fig. 5g). Taken together, our data suggest that lactate mediates its antidepressant effect by altering histone acetylation in the hippocampus, possibly by indirectly decreasing the levels of the class II HDAC5.

Discussion

With only half of the patients diagnosed with depression achieving remission, the need for novel antidepressants is high [2]. Even though the available antidepressants are highly selective, their inefficiency could be due to our limited knowledge of the molecular mechanisms underlying the disease [3]. In this study, we showed that lactate, a metabolite known to be increased during exercise, acts as an antidepressant and promotes resilience to stress in a CSDS mouse model of depression. We have also shown that these effects are achieved by modulating epigenetic pathways, namely histone acetylation/deacetylation dynamics.

It was previously established that cell- and gene-specific targeting of histone modifications controls CSDS behavior [41]. In this work, we showed that class I HDACs (HDAC2/3) have opposite roles during the time-course of depression. Initially, hippocampal HDAC2/3 mediate lactate-induced resilience to stress. Indeed, our results confirm the important role had by HDAC2/3 in the maintenance of normal social behavior and brain function [42, 43] and suggest that normal levels and deacetylase activity of these enzymes are necessary to promote resilience or inhibit a susceptibility transcriptional profile. In contrast, once the defeat or depressed phenotype is established, HDAC2/3 inhibition through CI-994 has antidepressant effects. This latter result confirms that class I HDAC inhibitors can be used as antidepressants and reinforces the viability of these HDAC isoforms as potential targets for antidepressant development. Our results are the first demonstration that systemic delivery of a class I selective HDACi rescues social deficits and anxiety, and thus mimics the previous results obtained with brain region-specific delivery of similar inhibitors [6, 7]. We have also shown that lactate acts as an antidepressant itself. Lactate reverses the social avoidance behavior, but not anxiety when administered as a therapeutic agent. Unlike resilience to stress, this effect is potentially related to regulation of the levels of the class II HDAC, HDAC5. Treatment with antidepressants such as imipramine decreases hippocampal HDAC5 levels [9] and promotes cytosolic export of HDAC5 [8]. This is thought to contribute to the beneficial effects of antidepressants on brain plasticity. Indeed, overexpression of HDAC5 in the hippocampus blocked imipramine’s ability to reverse depression-like behavior [9].

Even though our work provides evidence for the important roles that class I HDACs play in the hippocampus, we have not delineated the hippocampal regions where they exert their functions. Indeed, we can not rule out a role for these enzymes in other parts of the brain. Previous work has shown that infusion of the class I HDACi, MS-275, into the medial prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala exerts antidepressant effects [6]. Since we used systemic delivery of CI-994, our findings are consistent with the idea that brain region- specific overlapping molecular events are required to rescue the behavioral phenotypes. In addition, the opposite roles played by HDAC2/3 during the timeline of disease progression suggest that targeting these enzymes can serve as a therapeutic, but not a prophylactic.

In this work, we have shown that lactate, a metabolite known to be increased during exercise, promotes social interaction and rescues depression. Further work will be needed to more accurately delineate these temporal HDAC contributions and the brain regions involved. Because we have used lactate as an agent to mimic the effects of exercise, it will be ultimately interesting to determine whether exercise mediates resilience to chronic stress by increasing hippocampal lactate levels and activating its downstream epigenetic pathways.

Funding and disclosure

This work was supported by grants from the Lebanese American University School of Arts and Sciences and Graduate Research Fund to SFS. SFS conceived the study, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. NK, REG performed the experiments with the help of LEH, PN, PI, MB. JSS analyzed the results, provided valuable reagents and helped write the manuscript. RRR and EBH provided CI-994 and valuable insights and advice on class I HDAC inhibition. EBH: is a consultant for KDAc Therapeutics which has licensed compounds from the Broad Institute. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Moses V. Chao for valuable advice and sharing of reagents and to thank Mr. Jean Karam for help with animal research.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Nabil Karnib, Rim El-Ghandour

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41386-019-0313-z).

References

- 1.Smith K. Mental health: a world of depression. Nature. 2014;515:181. doi: 10.1038/515180a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Block SG, Nemeroff CB. Emerging antidepressants to treat major depressive disorder. Asian J Psychiatr. 2014;12:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nestler EJ, Barrot M, DiLeone RJ, Eisch AJ, Gold SJ, Monteggia LM. Neurobiology of depression. Neuron. 2002;34:13–25. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00653-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nestler EJ, Pena CJ, Kundakovic M, Mitchell A, Akbarian S. Epigenetic basis of mental illness. Neuroscientist. 2016;22:447–63. doi: 10.1177/1073858415608147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsankova N, Renthal W, Kumar A, Nestler EJ. Epigenetic regulation in psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:355–67. doi: 10.1038/nrn2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Covington HE, III, Maze I, Vialou V, Nestler EJ. Antidepressant action of HDAC inhibition in the prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience. 2015;298:329–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Covington HE, III, Vialou VF, LaPlant Q, Ohnishi YN, Nestler EJ. Hippocampal-dependent antidepressant-like activity of histone deacetylase inhibition. Neurosci Lett. 2011;493:122–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erburu M, Munoz-Cobo I, Dominguez-Andres J, Beltran E, Suzuki T, Mai A, et al. Chronic stress and antidepressant induced changes in Hdac5 and Sirt2 affect synaptic plasticity. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25:2036–48. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsankova NM, Berton O, Renthal W, Kumar A, Neve RL, Nestler EJ. Sustained hippocampal chromatin regulation in a mouse model of depression and antidepressant action. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:519–25. doi: 10.1038/nn1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sleiman SF, Henry J, Al-Haddad R, El Hayek L, Abou Haidar E, Stringer T, et al. Exercise promotes the expression of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) through the action of the ketone body beta-hydroxybutyrate. Elife. 2016;5:e15092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.van Praag H, Christie BR, Sejnowski TJ, Gage FH. Running enhances neurogenesis, learning, and long-term potentiation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13427–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cotman CW, Berchtold NC, Christie LA. Exercise builds brain health: key roles of growth factor cascades and inflammation. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:464–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sleiman SF, Chao MV. Downstream consequences of exercise through the action of BDNF. Brain Plast. 2015;1:143–8. doi: 10.3233/BPL-150017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim DM, Leem YH. Chronic stress-induced memory deficits are reversed by regular exercise via AMPK-mediated BDNF induction. Neuroscience. 2016;324:271–85. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mul Joram D., Soto Marion, Cahill Michael E., Ryan Rebecca E., Takahashi Hirokazu, So Kawai, Zheng Jia, Croote Denise E., Hirshman Michael F., la Fleur Susanne E., Nestler Eric J., Goodyear Laurie J. Voluntary wheel running promotes resilience to chronic social defeat stress in mice: a role for nucleus accumbens ΔFosB. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43(9):1934–1942. doi: 10.1038/s41386-018-0103-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duman CH, Schlesinger L, Russell DS, Duman RS. Voluntary exercise produces antidepressant and anxiolytic behavioral effects in mice. Brain Res. 2008;1199:148–58. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.12.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harvey SB, Overland S, Hatch SL, Wessely S, Mykletun A, Hotopf M. Exercise and the prevention of depression: results of the HUNT Cohort Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175:28–36. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16111223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noakes T, Spedding M. Olympics: run for your life. Nature. 2012;487:295–6. doi: 10.1038/487295a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.E L, Lu J, Selfridge JE, Burns JM, Swerdlow RH. Lactate administration reproduces specific brain and liver exercise-related changes. J Neurochem. 2013;127:91–100. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newman LA, Korol DL, Gold PE. Lactate produced by glycogenolysis in astrocytes regulates memory processing. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e28427. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suzuki A, Stern SA, Bozdagi O, Huntley GW, Walker RH, Magistretti PJ, et al. Astrocyte-neuron lactate transport is required for long-term memory formation. Cell. 2011;144:810–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang J, Ruchti E, Petit JM, Jourdain P, Grenningloh G, Allaman I, et al. Lactate promotes plasticity gene expression by potentiating NMDA signaling in neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:12228–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322912111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berthet C, Lei H, Thevenet J, Gruetter R, Magistretti PJ, Hirt L. Neuroprotective role of lactate after cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:1780–9. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carrard A, Elsayed M, Margineanu M, Boury-Jamot B, Fragniere L, Meylan EM, et al. Peripheral administration of lactate produces antidepressant-like effects. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:488. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dienel GA. Brain lactate metabolism: the discoveries and the controversies. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:1107–38. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferreira JC, Rolim NP, Bartholomeu JB, Gobatto CA, Kokubun E, Brum PC. Maximal lactate steady state in running mice: effect of exercise training. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;34:760–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ide K, Horn A, Secher NH. Cerebral metabolic response to submaximal exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:1604–8. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.5.1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ide K, Schmalbruch IK, Quistorff B, Horn A, Secher NH. Lactate, glucose and O2 uptake in human brain during recovery from maximal exercise. J Physiol. 2000;522:159–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-2-00159.xm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Golden SA, Covington HE, III, Berton O, Russo SJ. A standardized protocol for repeated social defeat stress in mice. Nat Protoc. 2011;6:1183–91. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaidanovich-Beilin O, Lipina T, Vukobradovic I, Roder J, Woodgett JR. Assessment of social interaction behaviors. J Vis Exp. 2011;48:e2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Henriques-Alves AM, Queiroz CM. Ethological evaluation of the effects of social defeat stress in mice: beyond the social interaction ratio. Front Behav Neurosci. 2015;9:364. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.File SE. Factors controlling measures of anxiety and responses to novelty in the mouse. Behav Brain Res. 2001;125:151–7. doi: 10.1016/S0166-4328(01)00292-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krishnan V, Han MH, Graham DL, Berton O, Renthal W, Russo SJ, et al. Molecular adaptations underlying susceptibility and resistance to social defeat in brain reward regions. Cell. 2007;131:391–404. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berton O, McClung CA, Dileone RJ, Krishnan V, Renthal W, Russo SJ, et al. Essential role of BDNF in the mesolimbic dopamine pathway in social defeat stress. Science. 2006;311:864–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1120972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bagot RC, Cates HM, Purushothaman I, Lorsch ZS, Walker DM, Wang J, et al. Circuit-wide transcriptional profiling reveals brain region-specific gene networks regulating depression susceptibility. Neuron. 2016;90:969–83. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bagot RC, Cates HM, Purushothaman I, Vialou V, Heller EA, Yieh L, et al. Ketamine and imipramine reverse transcriptional signatures of susceptibility and induce resilience-specific gene expression profiles. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;81:285–95. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benatti C, Valensisi C, Blom JM, Alboni S, Montanari C, Ferrari F, et al. Transcriptional profiles underlying vulnerability and resilience in rats exposed to an acute unavoidable stress. J Neurosci Res. 2012;90:2103–15. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pena CJ, Bagot RC, Labonte B, Nestler EJ. Epigenetic signaling in psychiatric disorders. J Mol Biol. 2014;426:3389–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Graff J, Joseph NF, Horn ME, Samiei A, Meng J, Seo J, et al. Epigenetic priming of memory updating during reconsolidation to attenuate remote fear memories. Cell. 2014;156:261–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seo YJ, Kang Y, Muench L, Reid A, Caesar S, Jean L, et al. Image-guided synthesis reveals potent blood-brain barrier permeable histone deacetylase inhibitors. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2014;5:588–96. doi: 10.1021/cn500021p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamilton PJ, Burek DJ, Lombroso SI, Neve RL, Robison AJ, Nestler EJ, et al. Cell-type-specific epigenetic editing at the Fosb gene controls susceptibility to social defeat stress. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43:272–84. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Akhtar MW, Raingo J, Nelson ED, Montgomery RL, Olson EN, Kavalali ET, et al. Histone deacetylases 1 and 2 form a developmental switch that controls excitatory synapse maturation and function. J Neurosci. 2009;29:8288–97. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0097-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Norwood J, Franklin JM, Sharma D, D’Mello SR. Histone deacetylase 3 is necessary for proper brain development. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:34569–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.576397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Covington HE, III, Maze I, Sun H, Bomze HM, DeMaio KD, Wu EY, et al. A role for repressive histone methylation in cocaine-induced vulnerability to stress. Neuron. 2011;71:656–70. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jiang Y, Jakovcevski M, Bharadwaj R, Connor C, Schroeder FA, Lin CL, et al. Setdb1 histone methyltransferase regulates mood-related behaviors and expression of the NMDA receptor subunit NR2B. J Neurosci. 2010;30:7152–67. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1314-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kurita M, Holloway T, Garcia-Bea A, Kozlenkov A, Friedman AK, Moreno JL, et al. HDAC2 regulates atypical antipsychotic responses through the modulation of mGlu2 promoter activity. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:1245–54. doi: 10.1038/nn.3181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.