Abstract

Background

SHON nuclear expression (SHON-Nuc+) was previously reported to predict clinical outcomes to tamoxifen therapy in ERα+ breast cancer (BC). Herein we determined if SHON expression detected by specific monoclonal antibodies could provide a more accurate prediction and serve as a biomarker for anthracycline-based combination chemotherapy (ACT).

Methods

SHON expression was determined by immunohistochemistry in the Nottingham early-stage-BC cohort (n = 1,650) who, if eligible, received adjuvant tamoxifen; the Nottingham ERα− early-stage-BC (n = 697) patients who received adjuvant ACT; and the Nottingham locally advanced-BC cohort who received pre-operative ACT with/without taxanes (Neo-ACT, n = 120) and if eligible, 5-year adjuvant tamoxifen treatment. Prognostic significance of SHON and its relationship with the clinical outcome of treatments were analysed.

Results

As previously reported, SHON-Nuc+ in high risk/ERα+ patients was significantly associated with a 48% death risk reduction after exclusive adjuvant tamoxifen treatment compared with SHON-Nuc− [HR (95% CI) = 0.52 (0.34–0.78), p = 0.002]. Meanwhile, in ERα− patients treated with adjuvant ACT, SHON cytoplasmic expression (SHON-Cyto+) was significantly associated with a 50% death risk reduction compared with SHON-Cyto− [HR (95% CI) = 0.50 (0.34–0.73), p = 0.0003]. Moreover, in patients received Neo-ACT, SHON-Nuc− or SHON-Cyto+ was associated with an increased pathological complete response (pCR) compared with SHON-Nuc+ [21 vs 4%; OR (95% CI) = 5.88 (1.28–27.03), p = 0.012], or SHON-Cyto− [20.5 vs. 4.5%; OR (95% CI) = 5.43 (1.18–25.03), p = 0.017], respectively. After receiving Neo-ACT, patients with SHON-Nuc+ had a significantly lower distant relapse risk compared to those with SHON-Nuc− [HR (95% CI) = 0.41 (0.19–0.87), p = 0.038], whereas SHON-Cyto+ patients had a significantly higher distant relapse risk compared to SHON-Cyto− patients [HR (95% CI) = 4.63 (1.05–20.39), p = 0.043]. Furthermore, multivariate Cox regression analyses revealed that SHON-Cyto+ was independently associated with a higher risk of distant relapse after Neo-ACT and 5-year tamoxifen treatment [HR (95% CI) = 5.08 (1.13–44.52), p = 0.037]. The interaction term between ERα status and SHON-Nuc+ (p = 0.005), and between SHON-Nuc+ and tamoxifen therapy (p = 0.007), were both statistically significant.

Conclusion

SHON-Nuce+ in tumours predicts response to tamoxifen in ERα+ BC while SHON-Cyto+ predicts response to ACT.

Subject terms: Predictive markers, Molecular medicine, Prognostic markers

Background

Annually there are approximately 2.1 million new cases of female breast cancer (BC) in the world.1 Despite improved treatment options, an estimated 626,000 women still die from this disease each year.1 BC is not one single disease but consists of a complex group of diseases that are highly heterogeneous in terms of genotype, phenotype, sensitivity to treatment, and clinical outcome.2 The success of improved personalised BC therapy relies on the development of robust and accurate biomarkers to guide clinical decision-making in the management of BC.

While targeted therapies are preferable to chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with oestrogen receptor α positive (ERα+) and HER2-positive (HER2+) metastatic BC, chemotherapy is often the initial therapeutic modality of choice for triple negative, and locally advanced or metastatic BC. A meta-analysis of 123 randomised trials involving more than 100,000 patients over 40 years has concluded that standard chemotherapy reduced two-year recurrence rates by 50%, eight-year recurrence rates by approximately one-third, and overall mortality rates by 20–25%.3 However, one obstacle to greater success with chemotherapy treatment is drug resistance (acquired or/and intrinsic).4 Currently, there is still no definitive methodology to distinguish tumours that will or will not respond to chemotherapies.5,6

SHON is a recently identified secreted hominoid-specific oncogene in BC.7 Forced expression of SHON in BC cell lines significantly increases cell proliferation and survival, promotes anchorage independent growth and enhances cell migration/invasion.7 Furthermore, SHON enhances the oncogenicity of BC cells in xenograft models and is sufficient to oncogenically transform MCF10A human normal breast cells.7 It has also been shown that SHON regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) through TGF-β signalling in BC cells.8 More importantly, SHON is an oestrogen inducible gene and its expression in ERα+ breast tumours has been shown to be a potential prognostic biomarker for predicting a patient's response to endocrine therapy.7 On the other hand, SHON expression is also observed in ERα− BC cell lines such as BT549 and MDA-MB-231, as well as in ERα− BC tissues.7 However, the clinical implication of SHON expression in ERα− breast tumours remains unknown.

In the present study, we analysed SHON protein expression in a large cohort of breast tumours by immunohistochemical (IHC) staining using a newly generated anti-SHON monoclonal antibody and determined the relationship of SHON expression with the clinical outcome of chemotherapy-treated patients in another two independent cohorts. We not only validated that SHON nuclear expression in tumour cells was an accurate predictive biomarker for ERα+ patients who received tamoxifen, but also identified that SHON cytoplasmic expression in ERα− tumours was able to predict the response of a patient to anthracycline-based treatment.

Materials and Methods

The Nottingham University Hospitals early-stage BC cohort

SHON protein expression was examined in a consecutive series of 1,650 patients with primary invasive breast carcinomas who were diagnosed between 1986 and 1999 and entered into the Nottingham University Hospitals (NUH) early-stage BC (NUH-ES-BC) cohort. All patients were treated uniformly in a single institution and have been investigated in a wide range of biomarker studies.9–11 Supplementary Table S1 summarises the patient demographics. Patients received standard surgery (mastectomy or wide local excision) with radiotherapy. Prior to 1989, patients did not receive either endocrine therapy or chemotherapy. After 1989, adjuvant therapy was scheduled on the basis of the Nottingham Prognostic Index (NPI), ERα and menopausal status. Patients with NPI scores < 3.4 (low risk) did not receive adjuvant therapy. Pre-menopausal patients with NPI scores ≥ 3.4 (high risk) received Cyclophosphamide, Methotrexate and 5-Fluorouracil (CMF) combination chemotherapy, and patients with ERα+ tumour were also received tamoxifen for 5 years. The minimum follow-up period was 123 months and the BC specific survival (BCSS) was used as a primary endpoint.

The NUH ERα− early-stage BC cohort

In order to assess the value of SHON protein expression as a biomarker in the context of current combination cytotoxic chemotherapy, we also analysed its expression in the NUH ERα− early-stage BC (NUH-ERα−ESBC) cohort. It is an independent series of 697 patients who had been diagnosed and managed at the same institution between 1999 and 2007, 141 of whom were treated with adjuvant anthracycline-based combination chemotherapy (ACT). Comprehensive follow-up data were available for 275 patients with BCSS as a primary endpoint (median = 89 months, mean = 86 months; Supplementary Table S1).

The NUH locally advanced BC cohort

The relationship between SHON protein expression and response to chemotherapy was evaluated by investigating its expression in the pre-chemotherapy core biopsies from 120 female patients with locally advanced (stage IIIA-C) primary BC (NUH-LABC), who were treated with anthracycline-based Neo-ACT (Neo-ACT) at the Nottingham City Hospital between 1996 and 2012. Fifty-three percent (62/120) of the patients received six cycles of anthracycline-based therapy, i.e. FEC: 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) 500 mg m−2, Epirubicin 75–100 mg m−2, Cyclophosphamide 500 mg m−2, on day 1 of a 21-day cycle, and 47% (54/120) of the patients received three cycles of the FEC plus three cycles of taxane (Docetaxel; 100 mg m−2). All patients underwent mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery and axillary dissection, followed by adjuvant radiation therapy and if tumours were ERα+, 5-year tamoxifen treatment. The median follow-up time was 67 months (IRQ 27–81).

Survival data

Survival data including survival time, disease-free survival (DFS), and development of loco-regional and distant metastases (DM) were maintained on a prospective basis. DFS was defined as the number of months from diagnosis to the occurrence of recurrence or DM relapse. BCSS was defined as the number of months from diagnosis to the occurrence BC-related death. Survival was censored if the patient was still alive, lost to follow-up, or died from other causes. The study was carried out according to the Reporting Recommendations for Tumour Marker Prognostic Studies (REMARK) criteria.12

Tissue microarrays and immunohistochemistry

Tumours were incorporated into tissue microarrays (TMAs). These were constructed using six replicate 0.6 mm cores from the centre and periphery of the tumours of each patient.

We produced a mouse monoclonal antibody against the mature SHON peptide. The specificity of the mouse anti-SHON monoclonal antibody was determined by Western blot analysis and indirect immunofluorescence staining. The antibody was able to specifically recognise both the endogenous and forced expression of SHON protein in human BC cell lines (Supplementary Figure S1).

The TMAs and full face sections were immunohistochemically profiled with the anti-SHON monoclonal antibody and other antibodies (Supplementary Table S2) using a Novolink Detection kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Leica Microsystems, UK) as we previously described.7 Sections were pre-treated by boiling in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 20 min, and incubated at room temperature for 60 min with the anti-SHON monoclonal antibody at a final concentration of 4 µg/ml. Expression of HER2, ERα and PR was assessed according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists (ASCO/CAP) guidelines.13,14

To validate the use of TMAs for immuno-phenotyping, full-face sections of 40 cases were stained and the protein expression levels were compared. The concordance between TMAs and full-face sections was excellent using Cohen's kappa statistical test for categorical variables (kappa = 0.8). Positive and negative (omission of the primary antibody and IgG-matched serum) controls were included in each run.

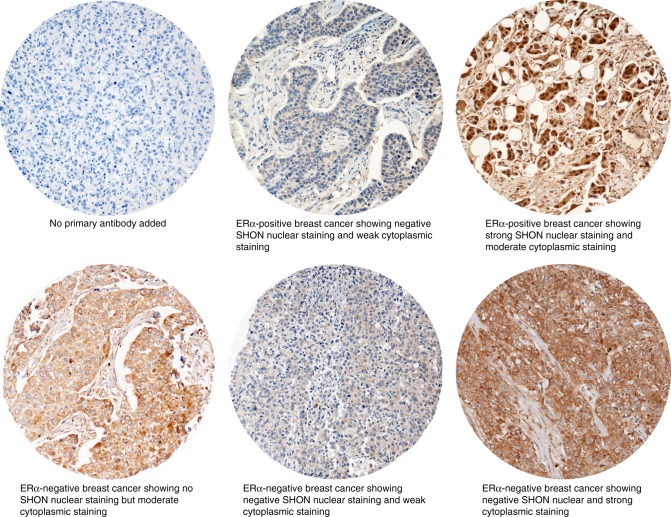

Evaluation of SHON IHC staining

Tumour cores were evaluated by two pathologists who were blinded to the clinicopathological characteristics of patients in two different settings. Whole field inspection of the core was scored, and intensities of both nuclear and cytoplasmic staining were grouped as follows: 0 = no staining, 1 = weak staining, 2 = moderate staining, and 3 = strong staining. The percentage of each category was estimated, and the H-score was calculated as previously described.9 Due to intra- and inter-tumoural heterogeneity of staining, the average percentage was calculated. The cut-off of SHON cytoplasmic and nuclear staining was determined by using the median expression. High cytoplasmic staining was defined as the presence of H-score > 150, whereas high nuclear staining was defined as the presence of ≥ 1% positive nuclear staining (Fig. 1). Intra- (kappa > 0.8; Cohen kappa test) and inter- (kappa > 0.8; using multi-rater kappa tests) observer agreements were excellent. In cases where discordant results were obtained, the slides were re-evaluated by both pathologists together and a consensus was reached.

Fig. 1.

Microphotographs of SHON expression in representative breast cancer TMA cores. SHON expression was determined by IHC using a SHON mouse monoclonal antibody. ERα, oestrogen receptor α

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed using SPSS statistics software (version 17, Chicago, IL). Where appropriate, Pearson’s Chi-square, and Student’s t-test were used. Significance was defined at p < 0.05.

Cumulative survival probabilities were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences between survival rates were tested for significance using the log-rank test. Multivariate analyses for survival were performed using the Cox proportional hazard model. The proportional hazards assumption was tested using standard log-log plots. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were estimated for each variable. All tests were two-sided with a 95% CI, and a p value < 0.05 was considered to be indicative of statistical significance. A stringent p value < 0.01 was considered to indicate statistical significance for multiple comparisons.

Results

Sub-cellular compartmentalisation of SHON protein expression

A total of 1,299 tumours in the NUH-ES-BC cohort were suitable for the IHC analysis of SHON protein expression. High nuclear SHON (SHON-Nuc+) staining was observed in 205/1,299 (16%) tumours compared to 1,094/1,299 (84%) tumours that had no nuclear SHON staining (SHON-Nuc−). However, 865/1,299 (67%) tumours exhibited high cytoplasmic staining (SHON-Cyto+) compared with 434/1,299 (33%) tumours that had low cytoplasmic expression (SHON-Cyto−). There was an inverse correlation between cytoplasmic and nuclear SHON expression (p < 0.0001). The majority of tumours (766/1,299; 59%) were SHON-Cyto+/Nuc− phenotype. The percentages of SHON-Cyto−/Nuc−, SHON-Cyto−/Nuc+ and SHON-Cyto+/Nuc+ tumours were 25% (328/1,299), 8% (106/1,299) and 8% (99/1,299), respectively.

Association of SHON nuclear expression with favourable clinicopathological characteristics

SHON nuclear expression was associated with favourable clinicopathological features including hormone receptor (ERα+, PR+ and AR+) positivity, 4-IHC luminal A (ERα+/HER2−/low proliferation phenotype), tubular BC, low histological grade, low mitotic index, low proliferation index (Ki67), low pleomorphism, and MDM4 overexpression (Table 1). Furthermore, SHON-Nuc+ was highly associated with high expression of DNA repair proteins: PARP1, TOPO2A, RECQL4 Nuclear, RECQL5, BLM Nuclear, CHK1, CHK2, and Phosphorylated CHK1 Nuclear (Table 1).

Table 1.

Association between SHON protein nuclear expression and clinicopathological variables in the NUH-ES-BC cohort (n = 1,650)

| Variables | SHON protein nuclear expression | χ2 p value (2 sided) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low N (%) | High N (%) | ||

| (A) Pathological parameters | |||

| Lymph node (LN) metastases | 0.824 | ||

| Negative | 753 (62.0) | 28 (63.6) | |

| Positive | 462 (38.0) | 16 (36.4) | |

| Gradea | <0.001* | ||

| Low (G1) | 183 (15.1) | 17 (38.6) | |

| Intermediate (G2) | 373 (30.8) | 20 (45.5) | |

| High (G3) | 656 (54.1) | 7 (15.9) | |

| Tumour size (cm) | 0.332 | ||

| T1 a + b (≤ 1.0) | 120 (9.9) | 6 (13.6) | |

| T1 c (> 1.0–2.0) | 596 (49.2) | 26 (59.1) | |

| T2 (> 2.0–5.0) | 462 (38.1) | 11 (25.0) | |

| T3 (> 5.0) | 34 (2.8) | 1 (2.3) | |

| Mitotic index | <0.001* | ||

| M1 | 370 (30.8) | 26 (61.9) | |

| M2 | 231 (19.2) | 8 (19.0) | |

| M3 | 600 (50.0) | 8 (19.0) | |

| Pleomorphism | <0.001* | ||

| P1 | 24 (2.0) | 1 (2.4) | |

| P2 | 428 (35.6) | 29 (69.0) | |

| P3 | 749 (62.4) | 12 (28.6) | |

| Tubule formation | 0.004* | ||

| T1 | 68 (5.7) | 2 (4.8) | |

| T2 | 394 (32.8) | 24 (57.1) | |

| T3 | 739 (61.5) | 16 (38.1) | |

| Lympho-vascular invasion | 0.587 | ||

| Positive | 788 (65.8) | 30 (69.8) | |

| Negative | 410 (34.2) | 13 (30.2) | |

| Histological type of invasive carcinoma | 0.016* | ||

| Invasive ductal carcinoma - no special type | 637 (61.5) | 11 (36.7) | |

| Tubular carcinoma | 210 (20.3) | 8 (26.7) | |

| Medullary carcinoma | 25 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Invasive lobular carcinoma | 79 (7.6) | 5 (16.7) | |

| Others | 84 (8.1) | 6 (20.0) | |

| (B) Molecular characteristics | |||

| ERα (IHC) | 0.044* | ||

| Negative | 348 (29.1) | 6 (14.6) | |

| Positive | 848 (70.9) | 35 (85.4) | |

| PR (IHC) | 0.049* | ||

| Negative | 507 (45.1) | 11 (28.9) | |

| Positive | 617 (54.9) | 27 (71.1) | |

| HER2 overexpression | 0.052 | ||

| No | 1,038 (87.7) | 41 (97.6) | |

| Yes | 145 (12.3) | 1 (2.4) | |

| HER3 (IHC) | 0.155 | ||

| Negative | 474 (49.6) | 16 (64.0) | |

| Positive | 482 (50.4) | 9 (36.0) | |

| HER4 (IHC) | 0.006* | ||

| Negative | 401 (41.6) | 19 (67.9) | |

| Positive | 563 (58.4) | 9 (32.1) | |

| Androgen receptor (IHC) | 0.034* | ||

| Negative | 369 (39.1) | 4 (17.4) | |

| Positive | 574 (60.9) | 19 (82.6) | |

| EGFR (IHC) | 0.974 | ||

| Low | 746 (79.7) | 16 (80.0) | |

| High | 190 (20.3) | 4 (20.0) | |

| MIB1 (Ki67) (IHC) | 0.001* | ||

| Low | 325 (32.4) | 20 (58.8) | |

| High | 679 (67.6) | 14 (41.2) | |

| BRCA1 (IHC) | 0.102 | ||

| Absent | 174 (20.4) | 1 (5.3) | |

| Normal | 677 (79.6) | 18 (94.7) | |

| SPAG5 (IHC) | 0.093 | ||

| Low | 696 (78.7) | 24 (92.3) | |

| High | 188 (21.3) | 2 (7.7) | |

| KIF2C (IHC) | <0.001* | ||

| Low | 264 (32.5) | 17 (68.0) | |

| High | 549 (67.5) | 8 (32.0) | |

| PARP1 (IHC) | 0.012* | ||

| Low | 537 (73.5) | 9 (47.4) | |

| High | 194 (26.5) | 10 (52.6) | |

| TOPO2A (IHC) | 0.001* | ||

| Low | 398 (46.7) | 3 (12.0) | |

| High | 454 (53.3) | 22 (88.0) | |

| P53 (IHC) | 0.306 | ||

| Low | 754 (78.1) | 20 (87.0) | |

| High | 212 (21.9) | 3 (13.0) | |

| P27 (IHC) | 0.057 | ||

| Low | 444 (61.1) | 9 (40.9) | |

| High | 283 (38.9) | 13 (59.1) | |

| Cyclin B2 (IHC) | <0.001* | ||

| Low | 532 (44.2) | 31 (72.1) | |

| High | 671 (55.8) | 12 (27.9) | |

| MDM2 (IHC) | 0.402 | ||

| Low | 628 (75.3) | 12 (66.7) | |

| High | 206 (24.7) | 6 (33.3) | |

| MDM4 (IHC) | 0.017* | ||

| Low | 667 (62.9) | 14 (42.4) | |

| High | 393 (37.1) | 19 (57.6) | |

| P21 (IHC) | 0.312 | ||

| Negative | 474 (55.6) | 14 (66.7) | |

| Positive | 379 (44.4 | 7 (33.3) | |

| P16 (IHC) | 0.745 | ||

| Low | 686 (84.4) | 18 (81.8) | |

| High | 127 (15.6) | 4 (18.2) | |

| P63 (IHC) | 0.438 | ||

| Negative | 978 (97.9) | 28 (100.0) | |

| Positive | 21 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| CDK1 (IHC) | 0.039* | ||

| Low | 506 (70.0) | 10 (100) | |

| High | 217 (30.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| BCL-2 (IHC) | 0.044* | ||

| Low | 385 (36.0) | 6 (18.8) | |

| High | 683 (64.0) | 26 (81.3) | |

| BAX (IHC) | 0.451 | ||

| Low | 465 (69.6) | 13 (61.9) | |

| High | 203 (30.4) | 8 (38.1) | |

| CK18 (IHC) | 0.663 | ||

| Negative | 108 (11.6) | 2 (8.7) | |

| Positive | 820 (88.4) | 21 (91.3) | |

| CK19 (IHC) | 0.192 | ||

| Negative | 62 (6.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Positive | 644 (93.8) | 26 (100.0) | |

| CK14 (IHC) | 0.012* | ||

| Negative | 875 (87.1) | 19 (70.4) | |

| Positive | 130 (12.9) | 8 (29.6) | |

| CK6 (IHC) | 0.096 | ||

| Negative | 838 (82.7) | 19 (70.4) | |

| Positive | 175 (17.3) | 8 (29.6) | |

| SMA (IHC) | 0.991 | ||

| Negative | 846 (85.1) | 23 (85.2) | |

| Positive | 148 (14.9) | 4 (14.8) | |

| ERCC1 (IHC) | 0.007* | ||

| Low | 344 (61.2) | 4 (26.7) | |

| High | 218 (38.8 | 11 (73.3) | |

| TDK (IHC) | 0.948 | ||

| Low | 461 (59.4) | 18 (60.0) | |

| High | 315 (40.6) | 12 (40.0) | |

| RECQL4 cytoplasm (IHC) | 0.137 | ||

| Low | 122 (15.2) | 7 (25.9) | |

| High | 673 (84.7) | 20 (74.1) | |

| RECQL4 nuclear (IHC) | 0.003* | ||

| Low | 405 (50.9) | 6 (22.2) | |

| High | 390 (49.1) | 21 (77.8) | |

| RECQL5 (IHC) | 0.027* | ||

| Low | 429 (47.9) | 9 (28.1) | |

| High | 466 (52.1) | 23 (71.9) | |

| Vimentin (IHC) | 0.686 | ||

| Low | 920 (88.6) | 25 (86.2) | |

| High | 118 (11.4) | 4 (13.8) | |

| E-cadherin (IHC) | 0.747 | ||

| Negative | 54 (5.5) | 1 (4.0) | |

| Positive | 931 (94.5) | 24 (96.0) | |

| BLM cytoplasm (IHC) | 0.533 | ||

| Low | 418 (45.0) | 20 (50.0) | |

| High | 511 (55.0) | 20 (50.0) | |

| BLM nuclear (IHC) | 0.001* | ||

| Low | 518 (55.8) | 12 (30.0) | |

| High | 411 (44.2) | 28 (70.0) | |

| CHK1 (IHC) | 0.016* | ||

| Low | 504 (52.5) | 7 (28.0) | |

| High | 456 (47.5) | 18 (72.0) | |

| ATM cytoplasm (IHC) | 0.311 | ||

| Low | 392 (53.2) | 6 (40.0) | |

| High | 345 (46.8) | 9 (60.0) | |

| ATR (IHC) | 0.098 | ||

| Low | 623 (64.4) | 28 (77.8) | |

| High | 345 (35.6) | 8 (22.2) | |

| CHK2 (IHC) | 0.039* | ||

| Low | 389 (48.3) | 5 (25.0) | |

| High | 416 (51.7) | 15 (75.0) | |

| Phosphorylated CHK1 nuclear (IHC) | <0.001* | ||

| Low | 975 (85.9 | 17 (38.6) | |

| High | 160 (14.1 | 27 (61.4) | |

| Phosphorylated CHK1 cytoplasm (IHC) | 0.328 | ||

| Low | 359 (31.6) | 17 (38.6) | |

| High | 776 (68.4) | 27 (61.4) | |

| XRCC1 (IHC) | 0.122 | ||

| Low | 142 (16.3) | 1 (4.3) | |

| High | 728 (83.7) | 22 (95.7) | |

| DNA polymerase beta (IHC) | 0.036* | ||

| Low | 396 (39.3) | 7 (21.2) | |

| High | 611 (60.7) | 26 (78.8) | |

| DNA PK (IHC) | 0.511 | ||

| Low | 317 (35.8) | 8 (29.6) | |

| High | 569 (64.2) | 19 (70.4) | |

| SMUG1 (IHC) | 0.063 | ||

| Low | 316 (40.7) | 4 (20.0) | |

| High | 461 (59.3) | 16 (80.0) | |

| APE1 (IHC) | 0.008* | ||

| Low | 493 (52.1) | 9 (28.1) | |

| High | 454 (47.9) | 23 (71.9) | |

| FEN1 (IHC) | <0.001* | ||

| Low | 606 (74.1) | 8 (36.4) | |

| High | 212 (25.9) | 14 (63.6) | |

| Phosphorylated c-Jun (IHC) | 0.023* | ||

| Low | 439 (46.7) | 7 (25.0) | |

| High | 501 (53.3) | 21 (75.0) | |

| Phosphorylated JNK (IHC) | 0.001* | ||

| Low | 661 (72.2) | 9 (39.1) | |

| High | 255 (27.8) | 14 (60.9) | |

| Phosphorylated p38 (IHC) | 0.062 | ||

| Low | 741 (84.1) | 16 (69.6) | |

| High | 140 (15.9) | 7 (30.4) | |

| SRC3 (IHC) | 0.603 | ||

| Low | 541 (57.2) | 15 (62.5) | |

| High | 405 (42.8) | 9 (37.5) | |

| S543 (IHC) | 0.001* | ||

| Low | 727 (82.9) | 12 (54.5) | |

| High | 150 (17.1) | 10 (45.5) | |

| ATF2 (IHC) | 0.786 | ||

| Low | 455 (49.2) | 13 (52.0) | |

| High | 469 (50.8) | 12 (48.0) | |

| T24 (IHC) | 0.669 | ||

| Low | 612 (74.6) | 15 (78.9) | |

| High | 208 (25.4) | 4 (21.1) | |

| T71 (IHC) | 0.252 | ||

| Low | 502 (50.6) | 12 (40.0) | |

| High | 490 (49.4) | 18 (60.0) | |

| HAGE (IHC) | 0.476 | ||

| Negative | 982 (90.8) | 33 (94.3) | |

| Positive | 100 (9.2) | 2 (5.7) | |

| TROAP (IHC) | 0.455 | ||

| Negative | 431 (55.7) | 11 (47.8) | |

| Positive | 343 (44.3) | 12 (52.2) | |

| Breast cancer sub-groups | 0.001* | ||

| Luminal A | 348 (34.5) | 24 (72.7) | |

| Luminal B (Ki67 ≥15) | 314 (31.1) | 4 (12.1) | |

| Luminal B (HER2+) | 63 (6.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Non-luminal HER2+ | 81 (8.0) | 1 (3.0) | |

| Basal-like | 155 (15.4) | 4 (12.1) | |

| ERα−/HER2− none basal | 48 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Basal-like phenotype | 0.508 | ||

| No | 981 (86.4) | 36 (90.0) | |

| Yes | 155 (13.6) | 4 (10.0) | |

| Triple negative phenotype | 0.105 | ||

| No | 937 (79.5) | 36 (90.0) | |

| Yes | 241 (20.5) | 4 (10.0) | |

ERα oestrogen receptor α, PR progesterone receptor, HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, Triple negative ERα−/PR−/HER2−

*Statistically significant at p < 0.05

aGrade as defined by the Nottingham Grading System (NGS)

Association of SHON cytoplasmic expression with aggressive clinicopathological characteristics

SHON cytoplasmic expression was associated with aggressive clinicopathological features including absence of hormone receptor (ERα− and PR−) positivity, basal-like phenotype, ERα−/HER2−, triple negative, invasive ductal carcinoma of no specific type (IDC-NST), higher histological grade, tubular dedifferentiation, pleomorphism, high mitotic index, and higher levels of proliferation markers (all p < 0.01) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between SHON protein cytoplasmic expression and clinicopathological variables in the NUH-ES-BC cohort (n = 1,650)

| Variables | SHON protein cytoplasmic expression | χ2 p value (2 sided) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low N (%) | High N (%) | ||

| (A) Pathological parameters | |||

| Lymph node (LN) metastases | 0.432 | ||

| Negative | 343 (63.2) | 457 (61.0) | |

| Positive | 200 (36.8) | 292 (39.0) | |

| Gradea | <0.001* | ||

| Low (G1) | 102 (18.8) | 106 (14.2) | |

| Intermediate (G2) | 192 (35.3) | 213 (28.6) | |

| High (G3) | 250 (46.0) | 426 (57.2) | |

| Tumour size (cm) | 0.180 | ||

| T1 a + b (≤ 1.0) | 49 (9.0) | 80 (10.7) | |

| T1 c (> 1.0–2.0) | 286 (52.6) | 286 (38.4) | |

| T2 (> 2.0–5.0) | 198 (36.4) | 25 (3.4) | |

| T3 (> 5.0) | 11 (2.0) | 25 (3.4) | |

| Mitotic index | <0.001* | ||

| M1 | 208 (38.9) | 204 (27.6) | |

| M2 | 100 (18.7) | 143 (19.3) | |

| M3 | 227 (42.4) | 393 (53.1) | |

| Pleomorphism | <0.001* | ||

| P1 | 13 (2.4) | 15 (2.0) | |

| P2 | 229 (42.8) | 240 (32.4) | |

| P3 | 293 (54.8) | 485 (65.5) | |

| Tubule formation | 0.488 | ||

| T1 | 31 (5.8) | 43 (5.8) | |

| T2 | 189 (35.3) | 238 (32.2) | |

| T3 | 315 (58.9) | 459 (62.0) | |

| Lympho-vascular invasion | 0.114 | ||

| Positive | 368 (68.8) | 477 (64.5) | |

| Negative | 167 (31.2) | 262 (35.5) | |

| Histological type of invasive carcinoma | <0.001* | ||

| Invasive ductal carcinoma - no special type | 256 (56.6) | 409 (63.7) | |

| Tubular carcinoma | 86 (19.0) | 138 (21.5) | |

| Medullary carcinoma | 10 (2.2) | 15 (2.3) | |

| Invasive lobular carcinoma | 56 (12.4) | 32 (5.0) | |

| Others | 44 (9.7) | 48 (7.5) | |

| (B) Molecular characteristics | |||

| ERα (IHC) | <0.001* | ||

| Negative | 117 (21.8) | 224 (33.2) | |

| Positive | 419 (78.2) | 490 (66.8) | |

| PR (IHC) | 0.048* | ||

| Negative | 210 (41.3) | 322 (47.0) | |

| Positive | 299 (58.7) | 363 (55.4) | |

| HER2 overexpression | 0.008* | ||

| No | 485 (91.0) | 624 (86.1) | |

| Yes | 48 (9.0) | 101 (13.9) | |

| HER3 (IHC) | <0.001* | ||

| Negative | 236 (56.7) | 263 (44.9) | |

| Positive | 180 (43.3) | 323 (55.1) | |

| HER4 (IHC) | 0.006* | ||

| Negative | 204 (47.3) | 227 (38.7) | |

| Positive | 227 (52.7) | 360 (61.3) | |

| Androgen receptor (IHC) | 0.580 | ||

| Negative | 156 (37.7) | 229 (39.4) | |

| Positive | 258 (62.3) | 352 (60.6) | |

| EGFR (IHC) | 0.005* | ||

| Low | 335 (83.8) | 442 (76.3) | |

| High | 65 (16.3) | 137 (23.7) | |

| MIB1 (Ki67) (IHC) | 0.004* | ||

| Low | 170 (38.7) | 189 (30.1) | |

| High | 269 (61.3) | 438 (69.9) | |

| BRCA1 (IHC) | 0.207 | ||

| Absent | 65 (18.1) | 114 (21.5) | |

| Normal | 295 (81.9) | 416 (78.5) | |

| SHON nuclear (IHC) | <0.001* | ||

| Negative | 491 (93.3) | 731 (98.8) | |

| Positive | 35 (6.7) | 9 (1.2) | |

| SPAG5 (IHC) | 0.03* | ||

| Low | 321 (82.5) | 417 (76.7) | |

| High | 68 (17.5) | 127 (23.3 | |

| KIF2C (IHC) | 0.003* | ||

| Low | 138 (39.9) | 155 (30.2) | |

| High | 208 (60.1) | 358 (69.8) | |

| PARP1 (IHC) | 0.008* | ||

| Low | 245 (77.8) | 314 (69.2) | |

| High | 70 (22.2) | 140 (ki67 | |

| TOPO2A (IHC) | 0.360 | ||

| Low | 174 (47.5) | 236 (44.4) | |

| High | 192 (52.5) | 295 (55.6) | |

| P53 (IHC) | 0.121 | ||

| Low | 338 (80.9) | 460 (76.8) | |

| High | 80 (19.1) | 139 (23.2) | |

| P27 (IHC) | 0.997 | ||

| Low | 198 (61.1) | 227 (61.1) | |

| High | 126 (38.9) | 173 (38.9) | |

| Cyclin B2 (IHC) | <0.001* | ||

| Low | 288 (54.3) | 295 (39.4) | |

| High | 242 (45.7) | 453 (60.6) | |

| MDM2 (IHC) | <0.001* | ||

| Low | 241 (68.7) | 412 (79.2) | |

| High | 110 (31.3) | 108 (20.8) | |

| MDM4 (IHC) | 0.002* | ||

| Low | 314 (68.0) | 386 (58.8) | |

| High | 148 (32.0) | 271 (41.2) | |

| P21 (IHC) | 0.064 | ||

| Negative | 218 (59.7) | 284 (53.5) | |

| Positive | 147 (40.3) | 247 (46.5) | |

| P16 (IHC) | 0.274 | ||

| Low | 292 (86.1) | 431 (83.4) | |

| High | 47 (13.9) | 86 (16.6) | |

| P63 (IHC) | 0.925 | ||

| Negative | 433 (98.0) | 602 (98.0) | |

| Positive | 9 (2.0) | 12 (2.0) | |

| CDK1 (IHC) | <0.001* | ||

| Low | 219 (77.9) | 307 (65.7) | |

| High | 62 (22.1) | 160 (34.3) | |

| BCL-2 (IHC) | 0.384 | ||

| Low | 159 (33.9) | 240 (36.4) | |

| High | 310 (66.1) | 419 (63.6) | |

| BAX (IHC) | 0.01* | ||

| Low | 209 (74.9) | 282 (65.7) | |

| High | 70 (25.1) | 147 (34.3) | |

| CK18 (IHC) | 0.77 | ||

| Negative | 48 (11.9) | 85 (11.3) | |

| Positive | 355 (88.1) | 510 (88.7) | |

| CK19 (IHC) | 0.308 | ||

| Negative | 31 (7.0) | 34 (5.5) | |

| Positive | 411 (93.0) | 585 (4.5) | |

| CK14 (IHC) | 0.384 | ||

| Negative | 385 (87.7) | 534 (85.9) | |

| Positive | 54 (12.3) | 88 (14.1) | |

| CK6 (IHC) | 0.039* | ||

| Negative | 379 (85.2) | 501 (80.3) | |

| Positive | 66 (14.8) | 123 (19.7) | |

| SMA (IHC) | 0.036* | ||

| Negative | 385 (87.5) | 505 (82.8) | |

| Positive | 55 (12.5) | 105 (17.2) | |

| ERCC1 (IHC) | 0.081 | ||

| Low | 151 (64.5) | 200 (57.3) | |

| High | 83 (35.5) | 149 (42.7) | |

| TDK (IHC) | 0.407 | ||

| Low | 211 (61.2) | 278 (58.3) | |

| High | 134 (38.8) | 199 (41.7) | |

| RECQL4 cytoplasm (IHC) | <0.001* | ||

| Low | 81 (24.3) | 51 (10.1) | |

| High | 252 (75.7) | 453 (89.9) | |

| RECQL4 nuclear (IHC) | 0.921 | ||

| Low | 167 (50.2) | 251 (49.8) | |

| High | 166 (49.8) | 253 (50.2) | |

| RECQL5 (IHC) | 0.023* | ||

| Low | 204 (51.4) | 243 (43.9) | |

| High | 193 (48.6) | 310 (56.1) | |

| Vimentin (IHC) | 0.637 | ||

| Low | 400 (89.1) | 566 (88.2) | |

| High | 49 (10.9) | 76 (11.8) | |

| E-cadherin (IHC) | 0.223 | ||

| Negative | 28 (6.5) | 29 (4.8) | |

| Positive | 402 (93.5) | 580 (95.2) | |

| BLM cytoplasm (IHC) | <0.001* | ||

| Low | 228 (53.6) | 219 (38.8) | |

| High | 197 (46.4) | 345 (61.2) | |

| BLM nuclear (IHC) | 0.720 | ||

| Low | 231 (54.4) | 313 (55.5) | |

| High | 194 (45.6) | 251 (44.5) | |

| CHK1 (IHC) | 0.210 | ||

| Low | 219 (53.9) | 300 (49.9) | |

| High | 187 (46.1) | 301 (50.1) | |

| ATM cytoplasm (IHC) | 0.922 | ||

| Low | 166 (52.7) | 243 (53.1) | |

| High | 149 (47.3) | 215 (46.9) | |

| ATR (IHC) | 0.011* | ||

| Low | 294 (69.7) | 373 (62.0) | |

| High | 128 (30.3) | 229 (38.0) | |

| CHK2 (IHC) | <0.001* | ||

| Low | 187 (55.3) | 215 (42.6) | |

| High | 151 (44.7 | 290 (57.4 | |

| Phosphorylated CHK1 nuclear (IHC) | 0.217 | ||

| Low | 433 (85.7) | 586 (83.1) | |

| High | 72 (14.3) | 119 (16.9) | |

| Phosphorylated CHK1 cytoplasm (IHC) | <0.001* | ||

| Low | 215 (42.6) | 174 (24.7) | |

| High | 290 (57.4) | 531 (75.3) | |

| XRCC1 (IHC) | 0.546 | ||

| Low | 64 (16.8) | 82 (15.4) | |

| High | 316 (83.2) | 452 (84.6) | |

| DNA polymerase beta (IHC) | <0.001* | ||

| Low | 201 (45.4) | 213 (34.2) | |

| High | 242 (54.6) | 409 (65.8) | |

| DNA PK (IHC) | <0.001* | ||

| Low | 176 (46.0) | 154 (28.1) | |

| High | 207 (54.0) | 394 (71.9) | |

| SMUG1 (IHC) | 0.095 | ||

| Low | 124 (36.6) | 203 (42.4) | |

| High | 215 (63.4) | 276 (57.6) | |

| APE1 (IHC) | <0.001* | ||

| Low | 254 (61.5) | 260 (44.3) | |

| High | 159 (38.5) | 327 (55.7) | |

| FEN1 (IHC) | 0.780 | ||

| Low | 261 (73.7) | 368 (72.9) | |

| High | 93 (26.3) | 137 (27.1) | |

| Phosphorylated c-Jun (IHC) | 0.023* | ||

| Low | 209 (50.9) | 253 (43.5) | |

| High | 202 (49.1) | 328 (56.5) | |

| Phosphorylated JNK (IHC) | 0.280 | ||

| Low | 294 (73.3) | 392 (70.1) | |

| High | 107 (26.7) | 167 (29.9) | |

| Phosphorylated p38 (IHC) | 0.563 | ||

| Low | 322 (85.0) | 457 (83.5) | |

| High | 57 (15.0) | 90 (16.5) | |

| SRC3 (IHC) | 0.08 | ||

| Low | 249 (60.6) | 319 (55.0) | |

| High | 162 (39.4) | 261 (45.0) | |

| S543 (IHC) | 0.866 | ||

| Low | 310 (82.2) | 448 (82.7) | |

| High | 67 (17.8) | 94 (17.3) | |

| ATF2 (IHC) | 0.325 | ||

| Low | 204 (51.4) | 277 (48.2) | |

| High | 193 (48.6) | 298 (51.8) | |

| T24 (IHC) | 0.885 | ||

| Low | 261 (75.4) | 384 (75.0) | |

| High | 85 (24.6) | 128 (25.0) | |

| T71 (IHC) | 0.015* | ||

| Low | 237 (55.0) | 293 (47.3) | |

| High | 194 (45.0) | 326 (52.7) | |

| HAGE (IHC) | 0.949 | ||

| Negative | 440 (90.9) | 602 (90.8) | |

| Positive | 44 (9.1) | 61 (9.2) | |

| TROAP (IHC) | 0.001* | ||

| Negative | 216 (62.8) | 241 (50.6) | |

| Positive | 128 (37.2) | 235 (49.4) | |

| Breast cancer sub-groups | 0.001* | ||

| Luminal A | 184 (41.2) | 202 (32.4) | |

| Luminal B (Ki67 ≥ 15) | 142 (31.8) | 181 (29.1) | |

| Luminal B (HER2+) | 27 (6.0) | 38 (6.1) | |

| Non-luminal HER2+ | 21 (4.7) | 62 (10.0) | |

| Basal like | 52 (11.6) | 111 (17.8) | |

| ERα−/HER2− none basal | 21 (4.7) | 29 (4.7) | |

| Basal-like phenotype | 0.003* | ||

| No | 463 (89.9) | 583 (84.0) | |

| Yes | 52 (10.1) | 111 (16.0) | |

| Triple negative phenotype | 0.005* | ||

| No | 441 (83.7) | 559 (77.2) | |

| Yes | 68 (16.3) | 165 (22.8) | |

ERα oestrogen receptor α, PR progesterone receptor, HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, Triple negative ERα−/PR−/HER2−

*Statistically significant at p < 0.05

aGrade as defined by the Nottingham Grading System (NGS)

SHON-Cyto+/Nuc− phenotype exhibited the most aggressive features including absence of hormone receptor (ERα−, PR− and AR−) positivity, triple negative, basal-like, large size, high stage, high grade, high lymphovascular invasion, overexpression of HER family (HER1+, HER2+, HER3+ and HER4+), p53 mutation, dysregulation of both DNA repair and high vimentin.

SHON protein nuclear expression predicted favourable clinical outcomes of ERα+ BC treated with endocrine therapy

SHON-Nuc+ in the whole NUH-ES-BC cohort was associated with prolonged BCSS and a reduced risk of death from BC [HR (95% CI) = 0.66 (0.55–0.80), p < 0.0001] (Fig. 2a), in the low risk patients [NPI < 3.4; HR (95% CI) = 0.53 (0.32–0.88), p = 0.015] (Fig. 2b), and in the ERα+ subgroup [HR (95% CI) = 0.61 (0.48-0.76), p < 0.0001] (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

Clinical outcome of SHON protein nuclear expression in breast cancer. Kaplan–Meier plots of the rates of breast cancer specific survival (BCSS; months) in the NUH-ES-BC cohort (n = 1,650) according to SHON protein nuclear expression (SHON-Nuc) status. The p value from the log rank test is shown in each panel; ‘n' is the number of samples in each group. High risk, NPI scores ≥ 3.4; ERα, oestrogen receptor α; +, positive expression; −, negative expression

In high risk (NPI ≥ 3.4)/ERα+ patients who did not receive tamoxifen treatment, tumours with or without SHON nuclear protein expression had a similar BCSS rate [HR (95% CI) = 1.00 (0.73–1.37), p = 0.998] (Fig. 2d). Meanwhile, SHON nuclear protein expression positivity was very significantly associated with better survival and a 48% lower risk of death in tamoxifen-treated patients [HR (95% CI) = 0.52 (0.34–0.78), p = 0.002] compared with SHON nuclear protein expression negativity (Fig. 2e). In high risk/ERα+ subgroups, if the tumours were SHON-Nuc−, administration of tamoxifen had no impact on the survival [HR (95% CI) = 0.85 (0.63–1.16), p = 0.302] (Fig. 2f), whereas if the tumours were also SHON-Nuc+, tamoxifen treatment resulted in improved survival and a reduced risk of death from BC by 79% [HR (95% CI) = 0.21 (0.08–0.56), p = 0.002] (Fig. 2g). This result is consistent with our previous observation that SHON nuclear protein expression is a predictor of patient response to tamoxifen treatment in BC.7

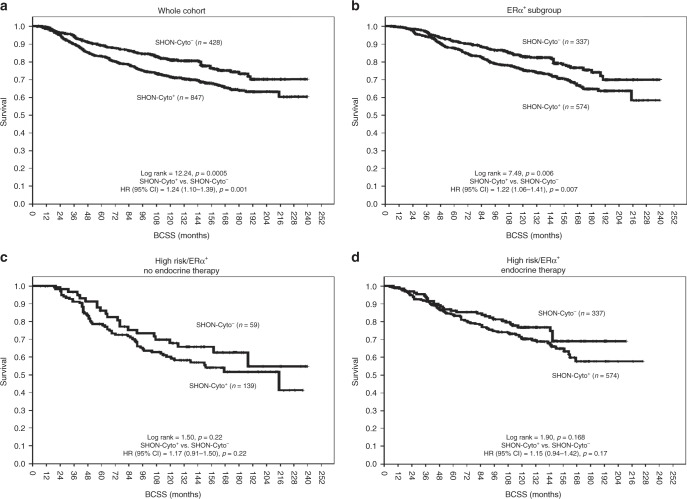

SHON protein cytoplasmic expression predicted worse clinical outcomes of BC

SHON-Cyto+ in the whole NUH-ES-BC cohort was associated with shorter BCSS and an increased risk of death from BC [HR (95% CI) = 1.24 (1.10–1.39), p = 0.001] (Fig. 3a), and the ERα+ subgroup [HR (95% CI) = 1.22 (1.06–1.41), p = 0.007] (Fig. 3b). However, there was no association between the impact of tamoxifen on patient survival and SHON cytoplasmic expression in the ERα+ subgroup (Fig. 3c, d).

Fig. 3.

Clinical outcome of SHON protein cytoplasmic expression in breast cancer. Kaplan–Meier plots of the rates of breast cancer specific survival (BCSS; months) in the NUH-ES-BC cohort (n = 1,650) according to SHON protein cytoplasmic expression (SHON-Cyto) status. The p value from the log rank test is shown in each panel; ‘n' is the number of samples in each group. High risk, NPI scores ≥ 3.4; ERα, oestrogen receptor α; +, positive expression; −, negative expression

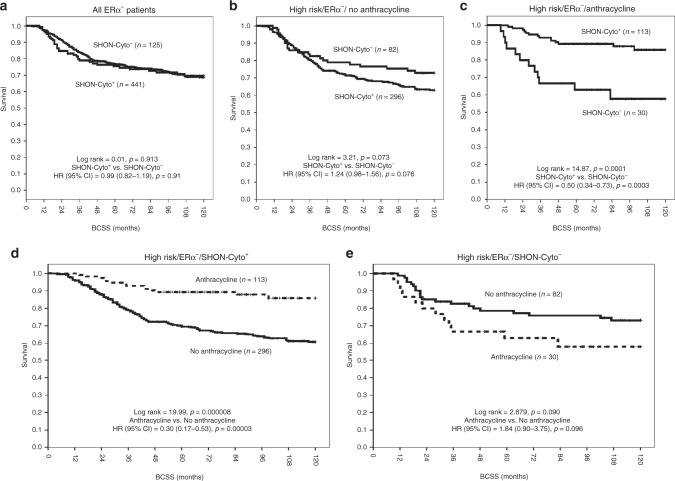

SHON protein cytoplasmic expression predicted clinical outcomes of ERα− BC treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy

In the ERα− BC subgroup, there was no association between SHON-Cyto+ and clinical outcomes in the NUH-ERα−ESBC cohort [HR (95% CI) = 0.99 (0.82–1.19), p = 0.91] (Fig. 4a). However, SHON cytoplasmic expression predicted better BCSS in those patients who received anthracycline-based combination chemotherapy. As shown in Fig. 4b, SHON-Cyto+ was associated with a trend of shorter survival in ERα− patients who did not receive any chemotherapy, though it was not statistically significant [HR (95% CI) = 1.24 (0.98–1.56), p = 0.076]. In contrast, in anthracycline-based combination-treated patients with ERα− tumours, SHON-Cyto+ was highly significantly associated with better BCSS and a lower risk of death compared with SHON-Cyto− [HR (95% CI) = 0.50 (0.34–0.73), p = 0.0003] (Fig. 4c). Exposure to anthracycline resulted in improved BCSS and a reduced risk of death from BC in tumours with SHON-Cyto+ [HR (95% CI) = 0.30 (0.17–0.53), p = 0.00003] (Fig. 4d), whereas in those with SHON-Cyto−, exposure to anthracycline was associated with a trend of shorter survival and a higher risk of death, though it was not statistically significant [HR (95% CI) = 1.84 (0.90–3.75), p = 0.096] (Fig. 4e). The interaction term between SHON-Cyto expression and anthracycline chemotherapy was highly significant (p < 0.001). These results indicate that SHON cytoplasmic protein expression was able to predict the BCSS of patients with ERα− tumours treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy.

Fig. 4.

Clinical outcome of SHON protein cytoplasmic expression in ERα− breast cancer patients. Kaplan–Meier plots of the rates of breast cancer specific survival (BCSS; months) in the NUH-ERα−ESBC cohort (n = 697) according to SHON protein cytoplasmic expression (SHON-Cyto) status. The p value from the log rank test is shown in each panel; ‘n' is the number of samples in each group. High risk, NPI scores ≥ 3.4; ERα, oestrogen receptor α; +, positive expression; −, negative expression

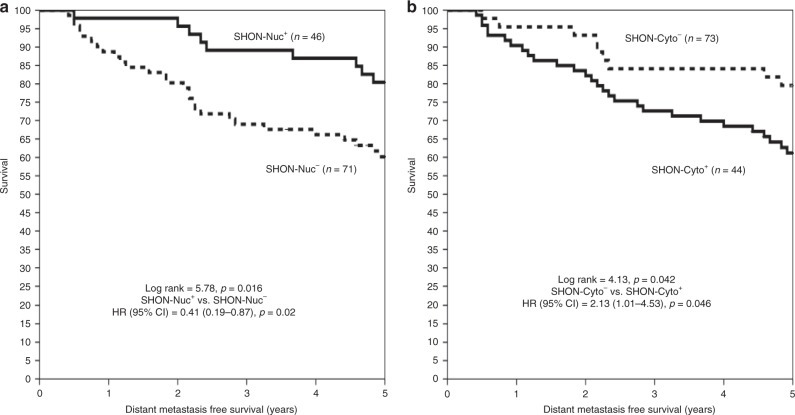

The relationship between SHON protein expression and distant relapse risks after receiving Neo-ACT and 5-year adjuvant tamoxifen

In the NUH-LABC cohort, BC patients received the Neo-ACT chemotherapy followed by a 5-year adjuvant tamoxifen treatment if the tumours were ERα+. Patients with high nuclear SHON protein expression had a significantly lower distant relapse risk compared to low nuclear SHON protein expression [20 vs 39%; HR (95% CI) = 0.41 (0.19–0.87), p = 0.02] (Fig. 5a), whereas high SHON cytoplasmic expression had a significant higher distant relapse risk compared to low SHON cytoplasmic expression [44 vs 22%; HR (95% CI) = 2.13 (1.01–4.53), p = 0.046] (Fig. 5b). Moreover; a multivariate Cox regression model controlling for other validated prognostic factors and systemic therapy revealed that high cytoplasmic SHON expression was independently associated with a higher risk of distant relapse after the Neo-ACT and 5-year tamoxifen treatment [HR (95% CI) = 5.08 (1.13–44.52), p = 0.037]. The interaction term between ERα status and SHON nuclear expression was statistically significant in determining distant metastasis-free survival (p = 0.005). In addition, the interaction term between SHON nuclear expression and tamoxifen therapy was also highly significant (p = 0.007) (Table 3).

Fig. 5.

Clinical outcome of SHON protein nuclear and cytoplasmic expression in the chemotherapy-treated patients. Kaplan–Meier plots of the rates of distant metastasis-free survival (years) in the NUH-LABC cohort (n = 117), who received neoadjuvant anthracycline-based combination chemotherapy and if ERα+, followed by 5-year adjuvant tamoxifen, according to the status of SHON protein nuclear expression (SHON-Nuc) (a) and SHON protein cytoplasmic expression (SHON-Cyto) (b). The p value from the log rank test is shown in each panel; ‘n' is the number of samples in each group. + positive expression, − negative expression

Table 3.

Multivariate Cox regression model analyses for distant metastasis-free survival in the NUH-LABC cohort (n = 117)

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| SHON cytoplasmic expression (high) | 7.06 | 1.13 | 44.52 | 0.037# |

| Adjuvant tamoxifen endocrine therapy | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.11 | 0.061 |

| ERα status | 13.90 | 2.26 | 85.63 | 0.005## |

| Post chemotherapy lymph node status | 0.999 | 0.995 | 1.003 | 0.697 |

| Post chemotherapy lymph vascular invasion | 1.003 | 0.999 | 1.007 | 0.090 |

| Residual tumour size (mm) | 1.002 | 0.998 | 1.005 | 0.287 |

| Histological grade | 0.807 | 0.390 | 1.673 | 0.565 |

| HER2 status | 1.020 | 0.414 | 2.513 | 0.966 |

| ERα*SHON nuclear expression interaction | 0.005## | |||

| ERα*SHON cytoplasmic expression Interaction | 0.065 | |||

| Adjuvant tamoxifen *SHON nuclear expression interaction | 0.007## | |||

ERα oestrogen receptor α, HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

#p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01

The relationship between SHON protein expression and response to Neo-ACT chemotherapy

We further investigated the association between SHON protein expression and the pathological complete response (pCR) in the NUH-LABC cohort, in which 117 patients had response data and 15% (17/117) achieved a pCR. SHON nuclear expression was detected in 39% (46/117) of the pre-chemotherapy core biopsies, whereas high cytoplasmic staining was observed in 62% (73/117) of the biopsies. No SHON expression was seen in 14.5% (17/117) of the biopsies, while 12% (14/117) showed both high nuclear and cytoplasmic staining, 50% (59/117) no nuclear but high cytoplasmic staining, and 23% (27/117) high nuclear but low cytoplasmic staining. Low SHON nuclear protein expression was associated with an increased proportion of patients achieving a pCR [21% (15/71) of the patients] compared with high SHON nuclear protein expression [4% (2/46) of the patients; OR (95% CI) = 5.88 (1.28–27.2203), p = 0.012]. High SHON cytoplasmic protein expression was associated with an increased proportion of patients achieving a pCR [21% (15/73) of the patients] compared with low SHON cytoplasmic protein expression [5% (2/44) of the patients; OR (95% CI) = 5.43 (1.18–25. 03), p = 0.017]. Multivariate logistic regression analyses showed that SHON high cytoplasmic staining, like SPAG5 overexpression,10 independently predicted the sensitivity to ACT (i.e., a higher pCR) [OR (95% CI) = 5.22 (1.03–26.47), p = 0.046] (Table 4)].

Table 4.

Multivariate logistic regression model analyses for the pCR in the NUH-LABC cohort (n = 117)

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| SHON cytoplasmic expression (high) | 5.22 | 1.03 | 26.47 | 0.046* |

| ERα status (positive) | 0.30 | 0.078 | 1.152 | 0.079 |

| HER2 status (overexpression) | 0.80 | 0.14 | 4.57 | 0.804 |

| SPAG5 (overexpression) | 4.84 | 1.274 | 18.36 | 0.021* |

ERα oestrogen receptor α, HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, SPAG5 sperm-associated antigen 5

*p < 0.05

Discussion

SHON is a recently identified novel secreted hominoid-specific oncoprotein in BC.7 We had previously generated a SHON polyclonal antibody and used it to perform IHC in the well-characterised Nottingham Tenovus primary breast carcinoma series.9–11 In that study, we demonstrated that SHON nuclear expression in breast tumours predicted the clinical outcome of patients who received tamoxifen in a high risk and ERα+ cohort.7 We have now developed a SHON monoclonal antibody and with it, we have not only validated our previous findings, but have also observed that SHON nuclear expression is actually an absolute determinant of survival outcomes with tamoxifen. Furthermore, we demonstrated that SHON cytoplasmic expression in ERα− tumours predicted clinical outcomes in patients receiving anthracycline-based chemotherapy. Given that tamoxifen and chemotherapy resistance severely limits successful management of BC, SHON may serve as a biomarker for selection of patients for treatment in the clinic.

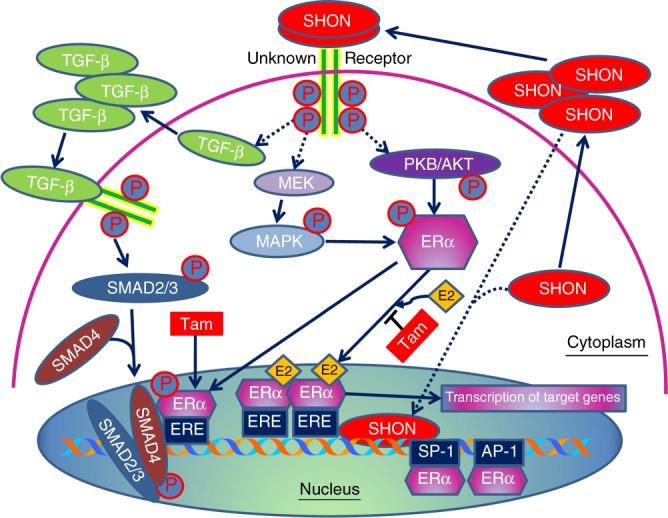

It is still unclear how SHON nuclear expression is able to impact on the efficacy of tamoxifen therapy. SHON is an oestrogen-regulated gene and the pure ERα antagonist ICI 182,780 partially attenuates SHON-stimulated growth promotion in MCF-7 breast cancer cells, indicating that SHON signalling is at least, in part, mediated by ERα.7 However, ERα-regulated functions are thought to play a pivotal role in determining the response to anti-oestrogen therapy. Several of the genes that the Oncotype DX test measures are ERα-regulated genes, including PR, BCL-2 and SCUBE2.15,16 Therefore, ERα-driven genes may be of particular interest for the development of molecular biomarkers to predict response to endocrine treatment. It has been shown that forced expression of SHON increases phosphorylation of AKT and p44/42 MAPK and increases the expression of BCL-2 and NF-κB to mediate the oncogenicity of SHON.7 Therefore, SHON may modulate ERα signalling through the activation of p44/42 MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways and NF-κB transcriptional activation of BCL-2 (Fig. 6). SHON presumably functions in an autocrine/paracrine manner as other secreted growth factors. Secreted SHON may bind to and activate a yet-unknown cell surface receptor, which consequently activates the PI3K/AKT and MAPK pathways that are linked to the action of ERα, including transcription of target genes. Nuclear SHON may also be directly involved in oestrogen independent signalling of ERα, through modulation of the binding of ERα to other transcription factors e.g. SP-1 and AP-1. It has now been shown that many secreted growth factors, including prolactin, growth hormone, epidermal growth factor (EGF), interferon gamma and Schwannoma-derived growth factor, are located both in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus.17 Such differential subcellular localisations are often associated with distinctive functions. It is observed that some of these factors e.g. FGFs contain nuclear localisation signals, but others do not. In the case of FGF-1, it is the exogenous, rather than intracellular, pools of FGF-1 that enter the nucleus.18,19 Cytosolic accumulation and subsequent nuclear import of FGF-1 require PI3K signalling, and nuclear translocation of FGF-1 is dependent upon acidic vesicular pumps. Once in the nucleus, nuclear FGF-1 stimulates DNA synthesis, independent of cell surface signalling. Moreover, multiple growth factor receptors have also been found in the nucleus, including the prolactin receptor, growth hormone receptor and EGF receptors in the form of both intact and cleaved membrane associated receptors. ERα itself is a nuclear receptor. Therefore, it is possible that exogenous and/or intracellular pools of SHON may directly enter the nucleus, and thus enhance the transcriptional activity of ERα (Fig. 6). However, it is not yet clear how SHON enters the nucleus. Of note, SHON has also been shown to promote EMT through the TGF-β pathway via the mediation of SMAD2/3 signalling.8 Activated SMAD2/3 binds SMAD4 in cytoplasm, followed by the translocation of the SMAD2/3/4 complex into the nucleus to regulate the transcription of TGF-β-induced genes.20,21 Upon exposure to tamoxifen, SMAD4 binds ERα and serves as a transcription corepressor for ERα.22,23 Therefore, SHON nuclear expression could be a determinant of an active ERα signalling complex so that tamoxifen can effectively block ERα signalling. It is also possible that its nuclear localisation facilitates TGF-β-SMAD4 and ERα cross talk and inhibits ERα-mediated gene transcription (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Current understanding of SHON and ERα signalling. Classically, ERα signalling is initiated following the binding of oestrogen (E2) to oestrogen receptor, resulting in its translocation to nucleus and binding directly to oestrogen response elements (EREs) on gene promoter of oestrogen-regulated genes, which subsequently activate transcription of downstream genes. Anti-oestrogen tamoxifen (Tam) competes with E2 for binding to ERα. SHON may bind to a yet-unknown receptor and activate PI3K/AKT and MAPK pathways that are linked to the action of ERα. SHON may also activate TGF-β pathway, resulting in SMAD2/3/4 translocation to nucleus and causing inhibition of ERα transcriptional activity upon Tam induction. Exogenous and/or intracellular pools of SHON may also enter the nucleus, thus enhancing the transcriptional activity of ERα

Biomarkers play a fundamental role in the personalisation of clinical breast cancer care for improved treatment outcomes. Despite more than a decade’s effort to develop new breast cancer biomarkers, only three biomarker tests (ERα, PR and HER2) are currently mandatory for those diagnosed with breast cancer.24 Other multigene tests are either useful only in a subgroup of breast cancers, including Oncotype DX, Prosigna, MammaPrint and EndoPredict, or simply investigational.25 They are commonly used to provide complementary prognostic information to clinicopathological features and predict chemotherapy benefit in early-stage hormone receptor-positive and HER2-negative BC.26–28 The development of multigene tests usually face issues such as insufficiently high levels of evidence, overfitting computational models and false discovery rates.29 In addition, they often do not yield significant improvement in predictive accuracy over the well-established pathological parameters such as histological grade.30 This is because these gene-expression biomarkers share common molecular pathways centred on cell proliferation and cell cycle regulation, which are the key components of the well-established pathological parameters.30 Moreover, MammaPrint and EndoPredic have been found to give different treatment recommendations for a portion of patients and cannot be used interchangeably,31 while Oncotype DX and MammaPrint offer different prognostic information to the same patients.32 Another issue with multigene tests is that some patients will still have an “intermediate” risk score, leading to an inconclusive prognosis,26 though chemotherapy may be surely spared in patients at intermediate recurrence scores as shown in the recent prospective TAILORx trail.28 Furthermore, although Oncotype DX can identify a group of patients with excellent prognosis when treated with adjuvant tamoxifen,15,16 it may provide no new biological insights into tamoxifen response than the simple measurement of ER and PR levels by the easy conventional IHC.33 It has now been demonstrated that a well selected single gene, such as SPAG5,10 ESPL134 or Ki67,35 may be a better indicator of proliferation than the mixture of suboptimal proliferation genes included in the multigene tests.36 Such a protein biomarker would easily be implemented in the clinic as a routine test using conventional IHC techniques that have been used for ER at a fraction of the high cost associated with multigene tests.

In the current study, we also demonstrated that SHON cytoplasmic expression predicted better survival to adjuvant ACT chemotherapy in the ERα− cohort, a higher pCR after receiving pre-operative ACT chemotherapy (chemotherapy responsiveness), and poor survival after 5-year tamoxifen treatment. In addition, SHON nuclear expression predicted favourable survival to adjuvant endocrine therapies, and a lower pCR after receiving pre-operative ACT chemotherapy (chemotherapy resistance). It is worthy of note that achieving a pCR after receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy provides important prognostic information and is considered a surrogate endpoint for event-free survival in ERα− or triple negative BC.37–39 In contrast, in ERα+ and HER2+ BC, the event-free survival is merely determined by the administration of targeting therapy: either endocrine or Herceptin therapy. Therefore, it was not surprising that SHON cytoplasmic expression was associated with a better survival outcome in our adjuvant ERα− BC cohort whereas it was associated with poor survival in the neoadjuvant cohort (which was predominantly ERα+ BC) who received pre-operative chemotherapy followed by 5-year adjuvant tamoxifen although SHON cytoplasmic expression was associated with a higher pCR. Similarly, although SHON nuclear expression was associated with a lower pCR after receiving pre-operative chemotherapy, it was associated with better survival after 5-year tamoxifen therapy.

We previously demonstrated that SHON was also expressed in ERα− BT549 and MDA-MB-231 BC cells.7 The current IHC analysis also showed that SHON cytoplasmic expression was significantly associated with aggressive BC phenotypes. Clinical data have previously indicated that as anti-oestrogen responsiveness increases, chemo-responsiveness decreases.40,41 We also showed that there was an inverse correlation between cytoplasmic and nuclear SHON expression in all the tumours. Therefore, it is consistent that nuclear SHON expression was linked to better survival to tamoxifen whereas cytoplasmic SHON expression was associated with better response to chemotherapy. High chromosomal instability and aneuploidy are hallmarks of malignant cells and confer vulnerability to chemotherapy.42 We demonstrated that SHON nuclear expression was highly associated with the expression of DNA repair proteins and a low proliferation index (Ki67), suggesting that SHON may be an important driver for genetic stability in BC, and SHON dysregulation could contribute to chromosomal instability. These findings are in agreement with previous studies that have suggested anthracycline works best in tumours with higher proliferation and chromosomal instability,43,44 whereas endocrine therapy is more effective in chromosomally stable, low proliferative BC.45

In summary, our study has clearly demonstrated that SHON expression in tumours is a potential biomarker for tamoxifen and chemotherapy responses, depending on its subcellular localisation. While SHON nuclear expression was able to predict patient outcomes to tamoxifen in ERα+ BC, SHON cytoplasmic expression could predict the response to ACT chemotherapy. However, the exact mechanism for its biomarker utility is still unclear. Identification of a potential SHON receptor, and determining the role of SHON in ERα− BC cells will be the next priority in delineating its mechanisms of action. Multicentre prospective studies are required for confirmation and validation before SHON can be used as a clinical biomarker.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Breast Cancer Now Tissue Bank for the provision of breast cancer tissue samples for the study and all the participating patients of the study. The authors also thank Holly Perry for critical reading of the manuscript.

Author contributions

Conception and design: D-X.L., T.M.A.A-F., R.J.B., J.L., B.H., D.P.L., A.R.G. Development of methodology: D-X.L., T.M.A.A-F., M.A., L-A.H., C.C.N., A.R.G. Acquisition of data: D-X.L., T.M.A.A-F., M.A., L.L., L.C., W.C., X.W., L-A.H., P.M.M., C.C.N., S.Y.T.C., I.O.E., A.R.G. Analysis and interpretation of the data: D-X.L., T.M.A.A-F., R.J.B., M.A., J.L., B.H., S.L., D.P.L., J.K.P., P.E.L., S.Y.T.C., I.O.E., A.R.G. Writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: D-X.L., T.M.A.A-F., R.J.B., M.A., L.L., J.L., B.H., S.L., L.C., R.Z.M., W.C., X.W., L-A.H., D.P.L., Y.L., J.L., J.K.P., P.M.M., C.C.N., P.E.L., S.Y.T.C., I.O.E., A.R.G. Study supervision: D-X.L., J.L., B.H., R.Z.M., X.W., D.P.L., S.Y.T.C., I.O.E., A.R.G.

Competing interests

D.-X.L., T.M.A.A.-F., J.K.P., J.L., B.H., S.Y.T.C., A.R.G., and I.O.E. are named inventors on a PCT patent application PCT/NZ/2013/000188 and patent applications NZ603056, NZ616981, CN201380063947, AU2013332512, EP2013846652 and US15/103581; D.-X.L. and R.Z.M. are applicants for the applications PCT/NZ/2013/000188 and NZ616981; and D.-X.L. is the applicant for the application NZ603056. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study and materials described are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Some restrictions may apply.

Ethics approval

All patients were consented as per hospital standard of care. This study was approved by the Hospital Research and Innovations Department and the Nottingham Research Ethics Committee 2 under the title "Development of a molecular genetic classification of BC" (REC Reference No C202313).

Funding

This work was supported by the Breast Cancer Foundation New Zealand (to D.-X.L. & R.J.B., no grant number), the New Zealand Breast Cancer Cure (to D.-X.L., no grant number), the Health Research Council of New Zealand (14/704 to D.-X.L., R.J.B., T.M.A.A.-F., J.L., A.R.G., S.Y.T.C. & I.O.E.), the Auckland Medical Research Foundation (1113022 to D-X.L.), the Margaret Morley Medical Trust (to D.-X.L., no grant number), the Maurice & Phyllis Paykel Trust (to D.-X.L., no grant number), the Kelliher Charitable Trust (to D.-X.L., no grant number), the Lottery Health Research of New Zealand (340942 to D.-X.L., I.O.E., A.R.G., S.Y.T.C. & T.M.A.A.-F.), the Biopharma Programme of the University of Auckland (to D.-X.L., no grant number), and the Shenzhen Development and Reform Commission Subject Construction Project (2017/1434 to P.E.L).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Andrew R. Green, Phone: +44-115 823 1407, Email: andrew.green@nottingham.ac.uk

Dong-Xu Liu, Phone: +64-9-921 9999, Email: dong-xu.liu@aut.ac.nz.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41416-019-0405-x.

References

- 1.Bray, F. et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 10.3322/caac.21492 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Zardavas D, Irrthum A, Swanton C, Piccart M. Clinical management of breast cancer heterogeneity. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2015;12:381–394. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peto R, et al. Comparisons between different polychemotherapy regimens for early breast cancer: meta-analyses of long-term outcome among 100,000 women in 123 randomised trials. Lancet. 2012;379:432–444. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61625-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Florea AM, Busselberg D. Cancers. 2011. Cisplatin as an anti-tumor drug: cellular mechanisms of activity, drug resistance and induced side effects; pp. 1351–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colombo PE, Milanezi F, Weigelt B, Reis-Filho JS. Microarrays in the 2010s: the contribution of microarray-based gene expression profiling to breast cancer classification, prognostication and prediction. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:212. doi: 10.1186/bcr2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borst P, Wessels L. Do predictive signatures really predict response to cancer chemotherapy? Cell Cycle. 2010;9:4836–4840. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.24.14326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung Y, et al. SHON is a novel estrogen-regulated oncogene in mammary carcinoma that predicts patient response to endocrine therapy. Cancer Res. 2013;73:6951–6962. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li L, et al. SHON, a novel secreted protein, regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition through transforming growth factor-beta signaling in human breast cancer cells. Int J. Cancer. 2015;136:1285–1295. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abd El-Rehim DM, et al. High-throughput protein expression analysis using tissue microarray technology of a large well-characterised series identifies biologically distinct classes of breast cancer confirming recent cDNA expression analyses. Int J. Cancer. 2005;116:340–350. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdel-Fatah TM, et al. SPAG5 as a prognostic biomarker and chemotherapy sensitivity predictor in breast cancer: a retrospective, integrated genomic, transcriptomic, and protein analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1004–1018. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)00174-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green AR, et al. Nottingham Prognostic Index Plus: Validation of a clinical decision making tool in breast cancer in an independent series. J. Pathol. Clin. Res. 2016;2:32–40. doi: 10.1002/cjp2.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McShane LM, et al. Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies (REMARK) J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1180–1184. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammond ME, Hayes DF, Wolff AC, Mangu PB, Temin S. American society of clinical oncology/college of american pathologists’ guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. J. Oncol. Pract. 2010;6:195–197. doi: 10.1200/JOP.777003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolff AC, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25:118–145. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paik S, et al. A multigene assay to predict recurrence of tamoxifen-treated, node-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351:2817–2826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paik S, et al. Gene expression and benefit of chemotherapy in women with node-negative, estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006;24:3726–3734. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.7985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Planque N. Nuclear trafficking of secreted factors and cell-surface receptors: new pathways to regulate cell proliferation and differentiation, and involvement in cancers. Cell Commun. Signal. 2006;4:7. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bryant DM, Stow JL. Nuclear translocation of cell-surface receptors: lessons from fibroblast growth factor. Traffic. 2005;6:947–954. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhen Y, et al. Nuclear import of exogenous FGF1 requires the ER-protein LRRC59 and the importins Kpnalpha1 and Kpnbeta1. Traffic. 2012;13:650–664. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2012.01341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Massague J. TGFbeta signalling in context. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:616–630. doi: 10.1038/nrm3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen W, Ten DP. Immunoregulation by members of the TGFbeta superfamily. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016;16:723–740. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu L, et al. Smad4 as a transcription corepressor for estrogen receptor alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:15192–15200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212332200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiong Z, et al. Synergistic repression of estrogen receptor transcriptional activity by FHL2 and Smad4 in breast cancer cells. IUBMB Life. 2010;62:669–676. doi: 10.1002/iub.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duffy MJ, et al. Clinical use of biomarkers in breast cancer: Updated guidelines from the European Group on Tumor Markers (EGTM) Eur. J. Cancer. 2017;75:284–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colomer R, et al. Biomarkers in breast cancer: a consensus statement by the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology and the Spanish Society of Pathology. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2018;20:815–826. doi: 10.1007/s12094-017-1800-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vieira AF, Schmitt F. An update on breast cancer multigene prognostic tests-emergent clinical biomarkers. Front Med. 2018;5:248. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krop I, et al. Use of biomarkers to guide decisions on adjuvant systemic therapy for women with early-stage invasive breast cancer: american society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline focused update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017;35:2838–2847. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.0472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sparano JA, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy guided by a 21-gene expression assay in breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;379:111–121. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayes, D. F., Khoury, M. J. & Ransohoff, D. Why hasn't genomic testing changed the landscape in clinical oncology? Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ. Book e52–e55 (2012). 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2012.32.e52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Sgroi DC. The HOXB13:IL17BR gene-expression ratio: a biomarker providing information above and beyond tumor grade. Biomark. Med. 2009;3:99–102. doi: 10.2217/bmm.09.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bosl A, et al. MammaPrint versus EndoPredict: Poor correlation in disease recurrence risk classification of hormone receptor positive breast cancer. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0183458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nunes RA, et al. Genomic profiling of breast cancer in African-American women using MammaPrint. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;159:481–488. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-3949-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kok M, Linn SC. Gene expression profiles of the oestrogen receptor in breast cancer. Neth. J. Med. 2010;68:291–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Finetti P, et al. ESPL1 is a candidate oncogene of luminal B breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;147:51–59. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3070-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rimm DL, et al. An international multicenter study to evaluate reproducibility of automated scoring for assessment of Ki67 in breast cancer. Mod. Pathol. 2019;32:59–69. doi: 10.1038/s41379-018-0109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bertucci F, Viens P, Birnbaum D. SPAG5: the ultimate marker of proliferation in early breast cancer? Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:863–865. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liedtke C, et al. Response to neoadjuvant therapy and long-term survival in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:1275–1281. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.4147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.von MG, et al. Definition and impact of pathologic complete response on prognosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in various intrinsic breast cancer subtypes. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30:1796–1804. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McAndrew N, DeMichele A. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Considerations in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J. Target Ther. Cancer. 2018;7:52–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Montemurro F, Aglietta M. Hormone receptor-positive early breast cancer: controversies in the use of adjuvant chemotherapy. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2009;16:1091–1102. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joerger M, Thurlimann B. Chemotherapy regimens in early breast cancer: major controversies and future outlook. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2013;13:165–178. doi: 10.1586/era.12.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sansregret L, Vanhaesebroeck B, Swanton C. Determinants and clinical implications of chromosomal instability in cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018;15:139–150. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Munro AF, Twelves C, Thomas JS, Cameron DA, Bartlett JM. Chromosome instability and benefit from adjuvant anthracyclines in breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2012;107:71–74. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jamal-Hanjani M, et al. Extreme chromosomal instability forecasts improved outcome in ER-negative breast cancer: a prospective validation cohort study from the TACT trial. Ann. Oncol. 2015;26:1340–1346. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McGranahan N, Burrell RA, Endesfelder D, Novelli MR, Swanton C. Cancer chromosomal instability: therapeutic and diagnostic challenges. EMBO Rep. 2012;13:528–538. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study and materials described are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Some restrictions may apply.