Abstract

Neuroticism is a stable and heritable personality trait that is strongly linked to depression. Yet, little is known about its association with late life depression, as well as how neuroticism eventuates into depression. This study used data from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (WLS; N=4,877) to examine the direct and indirect effects of neuroticism on late life depression at three points in the life course–ages 53, 64, and 71–via stressful life events (i.e., independent and dependent) and social supports measured across adulthood and into later life. Neuroticism was assayed using multiple methods, including self-report measures (phenotypic model) and a polygenic score (polygenic model) informed by a meta-analytic genome-wide association study. Results indicated that the phenotypic model of neuroticism and late life depression was partially mediated via dependent stressful life events experienced after the age of 53 and by age 64 social support. This association was replicated in the polygenic model of neuroticism, providing key evidence that the findings are robust. No indirect effects emerged with respect to age 53 social support, age 71 social support, adult dependent stressful life events (experienced between age 19 and 52), and adult and late life independent stressful life events in either the phenotypic or polygenic models as they pertained to late life depression. Results are consistent with previous findings that individuals with high neuroticism may be vulnerable to late life depression through psychosocial risk factors that are, in part, attributable to their own personality.

Keywords: Neuroticism, depression, polygenic score, social support, stressful life events

General Scientific Summary:

Neuroticism is strongly linked to depression, but little is known how this association unfolds over time, especially in older adults. This study suggests that neuroticism (measured using both a traditional self-report and an unbiased polygenic score) is indirectly associated with late life depression through the effects of late life dependent stressful life events and social support.

Neuroticism is a personality trait characterized by irritability, anger, sadness, anxiety, worry, hostility, self-consciousness, and vulnerability in response to threat, frustration, or loss (Costa & McCrae, 1992; Lahey, 2009). Neuroticism is notably associated with a wide gamut of negative physical (Goodwin, Cox, & Clara, 2006) and mental health outcomes (Lahey, 2009; Malouff, Thorsteinsson, & Schutte, 2005). Among mental health outcomes, the link between neuroticism and adult depression has been among the most well-studied in the literature (Fanous, Gardner, Prescott, Cancro, & Kendler, 2002; Kendler, Gatz, Gardner, & Pedersen, 2006; Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt, & Watson, 2010), yet little is known about its links to late life depression (Cheng, 2018). Late life depression is associated with increased mortality rate related to cardio- and cerebro-vascular diseases and suicide (Dines, Hu, & Sajatovic, 2014), impaired cognitive functioning (Butters et al., 2004), and increased risk of dementia (Diniz, Butters, Albert, Dew, & Reynolds, 2013). Furthermore, older individuals (age 65 and older) are the fastest growing segment of our population and projected to constitute nearly one quarter of the total population in the United States by 2060 (Colby, 2014). Depression among this age group is expected to rise in relative proportion (Dines et al., 2014). It is paramount to develop a better understanding about how neuroticism predicts depression in later life, as this knowledge may lead to improved and/or novel interventions for a vulnerable and growing population.

Relatively little is known about the causal pathways that link neuroticism and mental health outcomes more generally (Ferguson, 2013; Iacovino, Bogdan, & Oltmanns, 2016), in part due to the challenges of measuring neuroticism simultaneously with mental health outcomes (Lahey, 2009; Ormel, Rosmalen, & Farmer, 2004). For instance, measures of personality tend overlap in content with measures of depression and other mental health outcomes, thus inflating estimates of their association (Spijker, Graaf, Oldehinkel, Nolen, & Ormel, 2007). Even when overlapping items are removed, individuals who are high on neuroticism still tend to self-report more symptoms of unfounded illness and somatic symptoms (Rosmalen, Neeleman, Gans, & Jonge, 2007). To address possible measurement confounds in association studies of neuroticism and depression, the current investigation supplements traditional assays of neuroticism (i.e., self-report) with an unbiased and genetically-informed characterization of neuroticism.

Genes play an important role in the underpinnings of neuroticism, accounting for between 30 and 60% of its variance (Boomsma et al., 2018; Vukasović & Bratko, 2015). Recently, a large number of common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been discovered through genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of neuroticism (Luciano et al., 2018; Moor et al., 2015; Nagel et al., 2017; Okbay et al., 2016). Because a focus on genome-wide significant SNPs still leaves a substantial portion of the overall genetic variation in neuroticism uncharacterized, researchers are increasingly using polygenic scoring methods to account for the polygenicity of complex traits (Plomin, Haworth, & Davis, 2009). Conventionally, polygenic scores (PS) can be derived by taking an ensemble of associated genetic variants in a discovery GWAS sample and computing a weighted linear composite of these variants in a separate target sample (The International Schizophrenia Consortium, 2009). The advantage of this approach is that SNP weights are derived independently from the target study sample and eliminate any possibility of shared method confounds. Thus, PS for neuroticism can be used to validate associations between traditionally measured neuroticism (i.e., using self-report scales) and mental health outcomes. Studies using PS for neuroticism have rapidly emerged in recent years, with scores demonstrating significant associations with major depressive disorder (Gale et al., 2016; Lehto, Karlsson, Lundholm, & Pedersen, 2018; Moor et al., 2015). Twin study findings have also shown robust genetic correlations between neuroticism and depression (Fanous et al., 2002; Kendler et al., 2006), providing collective evidence that a large portion of the genetic variation for neuroticism and depression may be shared.

Multidimensional characterizations of neuroticism may help to elucidate the mechanisms by which neuroticism eventuates into late life depression. For instance, individuals with high levels of neuroticism are more prone to seeing the world as threatening, problematic, and distressing (Pegano et al., 2004). Thus, one theory is that they may be more likely to generate stressful life events (SLEs) (Hammen, 1991; Kendler, Gardner, & Prescott, 2005; Os, Park, & Jones, 2001), which in turn predicts depression in later life (Kendler & Gardner, 2016; Kendler, Karkowski, & Prescott, 1999). This association may be especially salient with respect to dependent SLEs, which are partly or entirely attributable to the person’s own behavior (e.g., being fired from a job), rather than independent SLEs which the result of factors not directly attributable to the person’s own behavior (e.g., losing a job due to the company closing) (Iacovino et al., 2016). Still, it remains unclear whether there are indirect effects of neuroticism on depression through SLEs (dependent or otherwise), as the few studies that have tested this association yielded conflicting results (Kercher, Rapee, & Schniering, 2009; Ormel, Oldehinkel, & Brilman, 2001). SLEs may be important constituents in causal models for late life depression, but well-powered longitudinal studies that extend into later adulthood are needed to provide a stronger test of this hypothesis.

Another plausible pathway between neuroticism and depression in later life is through the lack of perceived social support (Finch & Graziano, 2001; Kendler et al., 2006; Lahey, 2009). Poor social support is a well-established correlate of depression (Rueger, Malecki, Pyun, Aycock, & Coyle, 2016), including of late life depression (Schwarzbach, Luppa, Forstmeier, König, & Riedel‐Heller, 2013). However, a number of these studies examined social support in relation to depression independent from personality factors, even though individual differences in neuroticism may predict one’s initiation and maintenance of social supports (Lahey, 2009). One study found a significant indirect effect of neuroticism on adult depressive symptoms via poor social support, including lower levels of satisfaction and more frequent negative social interactions (Finch & Graziano, 2001). However, this association was modeled cross-sectionally using a college-aged population. Lara and colleagues (1997) also detected an indirect association between neuroticism and course of late life depression via social support in a small sample of depressed adults, providing evidence that high neuroticism may dispose certain individuals towards poor or disrupted social relationships that may in turn, increase risk for later depression (Lara, Leader, & Klein, 1997). However, more research is needed to determine whether these effects are also present in larger samples where depression has been mapped out into late adulthood.

The current investigation used prospective longitudinal data from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (WLS) to examine associations between neuroticism, SLEs and social support, and late life depression over a nearly 20-year span. This study combines traditional phenotypic measures (i.e., self-report) with individual-level genetic information (i.e., PS), with the goal of uncovering environmental mechanisms by which neuroticism eventuates into late life depression. We hypothesized that dependent SLEs and social support (but not independent SLEs) will mediate the association between neuroticism and late life depression symptoms. Importantly, we also aimed to validate our findings by examining the associations between self-report and PSs for neuroticism on depression in each of our models.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

This study uses data from WLS, a long-term study of a random sample (N=10,317) of all men and women (52% and 48%, respectively) born between 1938 and 1940 who graduated from Wisconsin (United States) high schools in 1957. Participants were followed up in 1964, 1975, 1992, 2004, and 2011 (Herd, Carr, & Roan, 2014). The sample is predominantly self-reported White of non-Hispanic origin (98%), reflecting the demographics in Wisconsin when WLS began in 1957. Since mental health and personality measures were collected beginning in the 1992 assessment and onwards, this study only uses the data from 1992, 2004, and 2011. Of the original 10,317 participants who participated in the study in 1957, 86% participated at the 1992 follow-up (n=8,493; mean age=53.22, S.D.=.65), 78% participated at the 2004 follow-up (n=7,732; mean age=64.32, S.D.=.71), and 60% participated at the 2011 follow-up (n=6,152; mean age=71.24, S.D.=.94). Attrition rates also include deaths. Genotyping was conducted in 2007/2008 and again in 2011, such that 58% of the original sample consented and provided saliva to WLS (n=5,984). In total, 4,877 participants had both phenotype and genotype data by the 2011 assessment, which forms the current study sample. Additional information about WLS can be accessed at http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/wlsresearch/. This study was approved by the [university name redacted for blind review] Institutional Review Board [study name and number redacted for blind review].

Measures

Depression Symptoms.

Depression symptoms were measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977) administered at the 1992, 2004 and 2011 assessments. The CES-D is a 20-item self-report screener for major depressive disorder, which asks respondents to rate how often over the past week they experienced symptoms associated with depression (e.g., depressed mood, feelings of guilt and worthlessness, loss of appetite, etc.). Respondents were originally asked to rate these items based on the number of days in the past week they experienced each symptom (i.e., 0 to 7). These items were recoded on a four-point Likert scale per Radloff (1977), where 0=“rarely or none of the time,” 1=“some or little of the time,” 2=“moderately or much of the time,” and 3=“most or almost all of the time.” A composite score at each assessment was used in the current analyses, with scores ranging from 0 to 60 (higher scores indicate greater depression symptoms).

Neuroticism.

Neuroticism was measured from five items using the Big Five Inventory (John, Donahue, & Kentle, 1991) administered at the 1992, 2004 and 2011 assessments. Respondents were asked to rate “to what extent do you agree that you see yourself as someone who…: 1) can be tense, 2) is emotionally stable and not easily upset, 3) worries a lot, 4) remains calm in tense situations, and 5) gets nervous easily?” All items were rated on a 6-point Likert scale, where 1=“agree strongly,” 3=“agree slightly,” and 6=“disagree strongly.” Items 1, 3, and 5 were reverse coded so that higher scores indicate higher neuroticism. A composite score of neuroticism at each assessment was used in the current analyses, with scores ranging from 0 to 30 (higher scores indicate higher neuroticism).

Social Support.

Social support was assessed during the 1992, 2004, and 2011 assessments. We used five items to assess the quality and amount of social support experienced by the participant at each time point: 1) “is there a person in your family with whom you can really share your very private feelings and concerns?” 2) “is there a friend outside your family with whom you can really share your very private feelings and concerns?” 3) “if you had a personal problem, and you wanted to talk to someone about it, could you ask friends, neighbors, or co-workers for help or advice?” 4) “how much do friends and relatives, other than your spouse or your children, make you feel loved and cared for?” and 5) “how much are friends and relatives, other than your spouse or your children, willing to listen to you when you need to talk about your worries or problems?” These items were selected because they were asked at each time point. Respondents were asked yes/no to items 1–3, whereas items 4–5 were queried on a Likert scale, where = “not at all,” 2= “a little,” 3= “some,” 4= “quite a bit,” and 5= “a lot.” To maintain consistency of scale, items 4–5 were dichotomized such that scores of 4 or higher were scored “1” and 3 and lower were scored “0.” Thus, composite scores for social support at each assessment were used in the current analysis, with scores ranging from 0 to 5 (higher scores indicate higher social support).

Stressful Life Events (SLEs).

SLEs were assessed retrospectively at the 2011 assessment. A total of 15 items were queried about the respondent’s lifetime exposure to dependent and independent events. Dependent SLEs were comprised of exposure to three events, including financial problems, legal difficulties, and imprisonment. Independent SLEs were comprised of 12 items, including items related to the experience of childhood maltreatment (i.e., physical and sexual abuse), death of a loved one, experience of a natural disaster, caring for a child, and caring for an aging parent. For each item, respondents were first asked if they ever experienced the event (yes/no). If they responded affirmatively to the event, they were then asked, “how old were you the last time [the event occurred]?” Thus, based on the most recent occurrence of SLEs, we created four composite variables representing 1) the developmental period in which the SLE was last experienced (i.e., adult SLEs=age 18–52 versus late life SLEs=age 53 and later) and 2) the type of SLE experienced (i.e., dependent versus independent). A childhood independent SLEs composite was also created, which includes physical and sexual abuse and other SLEs experienced prior to the age of 18.

DNA Collection and Genotyping and Quality Control

Saliva samples were collected from study participants using Oragene DNA collection kits by mail in 2007/2008 and from home interviews during the 2011 assessment (Herd et al., 2014). Saliva samples were genotyped at the Center for Inherited Disease Research at Johns Hopkins University Center. Genotyping was performed using the Illumina HumanOmniExpress array. A total of 713,014 SNPs were genotyped. Sample quality control filters were applied based on the following criteria: 1) samples of questionable identity (12 samples), 2) irreconcilable discrepancies either between annotated and genetic sex or relatedness (12 samples), and 3) presence of chromosomal abnormalities associated with error-prone genotypes and whole samples with an overall missing call rate>2% (31 samples). SNPs were filtered if the minor allele frequency was less than .01 or if they were deemed “non-informative,” defined as either a technical failure, redundant positional duplicate, or monomorphism in the sample (2.3% of all SNPs). SNPs were also pruned for linkage disequilibrium (LD) (R2<.01 in a sliding 10 Mb window). Applying these filters resulted in a total of 16,185 SNPs removed from the original 713,014 SNPs that were genotyped. Genotype data were then imputed to a reference of European ancestry from the Haplotype Reference Consortium. SNPs with a minor allele frequency less than .01 or imputation quality score less than .8 were removed after the imputation. After quality control, a total of 7,251,583 autosomal SNPs remained in our analysis.

Polygenic Scores for Neuroticism

A meta-analytic GWAS of neuroticism was previously conducted by the Social Science Genetic Association Consortium, which included data from the Genetics of Personality Consortium (n=63,661 across 29 cohorts) and data from the UK Biobank (n=107,245), yielding a pooled sample of N=170,911 in the GWAS meta-analysis. For the Genetics of Personality Consortium data, neuroticism was measured from a combination of the NEO Personality Inventory, Eysenck Personality Questionnaire, and International Personality Item Pool Inventory. Genetics of Personality Consortium neuroticism data were harmonized using Item Response Theory. For UK Biobank data, neuroticism was measured using a 12-item version of the Eysenck Personality Inventory Neuroticism scale. The meta-analytic GWAS of neuroticism was conducted on a single, composite variable for neuroticism on the pooled sample of N = 170,911 by Okbay and colleagues (2016).

Next, we computed PS for neuroticism on our sample by specifying a GWAS p-value threshold of .05. Due to the presence of LD, we pruned SNPs as part of the calculation (LD-clumping with a R2 threshold of 0.1 and a distance threshold of 250 kb). We included all SNPs from the GWAS that met the p-value and LD thresholds (31,040 SNPs), summed the number of risk alleles at each of these SNPs (i.e., 0, 1, or 2) and multiplied them by their GWAS effect size. As expected, the zero-order correlation (i.e., no between the PS for neuroticism and the factor score of neuroticism was significant (r=.110, p<.001), explaining 1.2% of its variance.

Data Reduction

Neuroticism was measured across three assessments (in 1992, 2004, and 2011) in WLS. Because neuroticism is a stable personality trait, especially among older adults (Anusic & Schimmack, 2016; Steunenberg, Twisk, Beekman, Deeg, & Kerkhof, 2005), we considered the multiple points of data on each individual’s level of neuroticism across adulthood as individual factor loadings for a single latent factor representing neuroticism. Indeed, the bivariate correlations of neuroticism across the three assessments were robust (r=.54–.69) and the single-factor confirmatory factor analysis not only demonstrated strong fit to the data (RMSEA=0, CFI=1, TLI=1), but also very high standardized factor loadings for each measure of neuroticism (factor loading ranged from .70 to .86). Thus, we derived factor scores for neuroticism to more precisely characterize each person’s level of neuroticism after accounting for 18 years of data. This variable served as our predictor in the “phenotypic model” (see Data Analysis section below for more details).

With respect to depression symptoms, only a few studies have examined its stability of in late life and those studies have produced mixed results. One study found that depression symptoms were stable from ages 55 to 85 (Beekman et al., 2002), a separate study of adults aged 70 and older showed a slight increase in symptoms over time (Hong, Hasche, & Bowland, 2009), and yet another study of adults aged 65 and older found a slight decrease in depression over time (Yang, 2007). Given the lack of consensus with regard to the form factor of depression trajectories in older adults, we conducted a latent growth curve analysis (LGCA) across three waves of depression data, specifying a 1) intercept-only factor model and a 2) intercept and slope factor model. In the intercept and slope factor model, factor loadings were fixed to represent each unit increase in time [i.e., 1992 (T1) → 2004 (T2) → 2011 (T3)]. Model selection was determined per expert recommendations (Collins & Lanza, 2013). Fit indices for the intercept only model (Bayesian information criterion (BIC)=88880.12, RMSEA=.08, CFI=.90, TLI=.92) were superior to the intercept and slope model (BIC= 88887.17, RMSEA=.18, CFI=.88, TLI=.63). Furthermore, the variance of the slope factor in the intercept and slope model was not significant (b=−.87, s.e.=1.15, p=.45) indicating no significant variability in the change in depression symptoms from T1 to T3. Due to the invariance of the slope factor and the superior of fit for the intercept only model, an intercept factor score of depression symptoms was used in our subsequent models. The zero-order correlation between the PS for neuroticism and the factor score for depression was significant (r=.074, p<.001), explaining 0.5% of its variance.

Data Analysis

We conducted serial multiple mediator models to investigate the indirect and direct effects of predictor (i.e., neuroticism) on the outcome (i.e., LGCA factor scores from Step 1 for depression symptoms) while also modeling a process in which the predictor predicts M1 (i.e., T1 social support, SLEs), which in turn predicts M2 (i.e., T2 social support, SLEs), and so forth, concluding with the outcome variable as the final consequent. Classical tests of mediation (Baron & Kenny, 1986) require that a series of conditions must be met (i.e., predictor correlated with the outcome, predictor correlated with mediator, and mediator correlated with outcome controlling for predictor). One key update to classical mediation is that the condition of the predictor being correlated with the outcome need not occur for mediation (Preacher and Hayes, 2008). The association of the predictor and the outcome may reflect a “stage sequence” effect whereby the predictor may lead to a change in the mediator first, which then subsequently changes the outcome (Collins et al., 1998). Three major conceptual models were tested, which differed by the hypothesized indirect effect pathways.

Model 1 examined the direct and indirect effects of neuroticism on late life depression symptoms through the effects of social support measured at T1 (1992), T2 (2004), and T3 (2011), while controlling for adult and late life SLEs (including both dependent and independent forms), childhood SLEs, as well as demographic variables (see Covariates below). Because neuroticism was measured based on self-report, we called this the “phenotypic model” of neuroticism. We then conducted a parallel analytic model that examined the direct and indirect effects of a PS for neuroticism instead of the factor score of neuroticism. This model served to provide a more unbiased approach for estimating direct and indirect effects relative to the phenotypic model. This model was referred to as the “polygenic model” of neuroticism.

Model 2 examined the direct and indirect effects of the phenotypic model of neuroticism on late life depression symptoms through the effects of adult and late life dependent SLEs, while controlling for adult and late life independent SLEs, childhood SLEs, social support at T1-T3, and demographic variables. Once again, we tested a parallel analytic model in the polygenic model of neuroticism that examined the direct and indirect effects of a PS for neuroticism instead of the factor score of neuroticism (i.e., the polygenic model).

Model 3 examined the direct and indirect effects of neuroticism on late life depression symptoms through the effects of adult and late life independent SLEs, while controlling for adult and late life dependent SLEs, childhood SLEs, social support at T1-T3, and demographic variables (i.e., the phenotypic model). We then examined the direct and indirect effects of a PS for neuroticism instead of the factor score of neuroticism in the polygenic model.

Covariates

For the phenotypic models, we controlled for sex (1=male, 2=female), highest level of education (0–21 scale representing years of education completed), current marital status (0=never married, separated, divorced or widowed, and 1=married), and childhood SLEs (dependent and independent SLEs experienced before age 18, including exposure to physical and sexual abuse) in each of the regression pathways in Models 1–3 (e.g., predictor to T1 mediator, T1 mediator to T2 mediator, and T2 mediator to outcome). We covaried sex given the presence of sex differences in the prevalence of depression and expression of neuroticism (Kendler et al., 2006; Kendler, Kuhn, & Prescott, 2004). Level of education and marital status were covaried given their associations with late life depression (Miech & Shanahan, 2000). We controlled for childhood SLEs (including maltreatment) given evidence that childhood trauma and maltreatment may be causally associated with adult neuroticism (Allen & Lauterbach, 2007). For the phenotypic models (i.e., PSs of neuroticism), we additionally accounted for the possibility of population stratification in WLS by controlling for the top 10 principal components of the covariance matrix of WLS genotypic data, as population stratification may severely bias estimates of effect size.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Demographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. Table 2 shows the bivariate correlations among the study variables. Correlations between adult independent and dependent SLEs were significant (r=.16, p<.01), as were correlations between late life independent and dependent SLEs (r=.19, p<.01). Similarly, correlations between T1–T3 social support were robust (r’s=.35–.45, p’s<.01). As expected, depression was positively correlated with dependent and independent SLEs (except for late life independent SLEs), negatively correlated with social support, and positively correlated with neuroticism. Finally, neuroticism was not significantly correlated with dependent or independent SLEs but was negatively correlated with social support.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Variable | T1 (1992) | T2 (2004) | T3 (2011) |

|---|---|---|---|

| % Male | 47.40 | 47.50 | 47.10 |

| Mean Age (S.D.) | 53.22 (.65) | 64.32 (.71) | 71.24 (.94) |

| % Highest Level Education | |||

| Less than one year of college | 54.70 | ||

| Some college | 16.00 | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 14.40 | ||

| Advanced degree (master’s and above) | 15.00 | ||

| % Married | 79.20 | ||

| Mean CES-D Depression (S.D.) (0–60) | 8.32 (7.55) | 6.85 (6.76) | 7.91 (7.44) |

| Mean Big Five Inventory Neuroticism (0–30) | 15.68 (7.3) | 14.85 (4.60) | 14.81 (4.72) |

| Mean Social Support (S.D.) (0–5) | 2.44 (.79) | 3.70 (1.37) | 1.99 (.91) |

| Mean Independent SLEs (S.D.) (0–12) | |||

| Adult | .29 (.64) | ||

| Late life | 1.31 (1.24) | ||

| Mean Dependent SLEs (S.D.) (0–3) | |||

| Adult | .05 (.24) | ||

| Late life | .09 (.33) |

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex | 1 | |||||||||||

| 2. Level of Education | −.151** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 3. Marital Status | −.154** | .008 | 1 | |||||||||

| 4. Adult Independent SLEs | .029 | .008 | −.045** | 1 | ||||||||

| 5. Late Life Independent SLEs | −.003 | .011 | .003 | .146** | 1 | |||||||

| 6. Adult Dependent SLEs | −.090** | .017 | −.033* | .157** | .130** | 1 | ||||||

| 7. Late Life Dependent SLEs | −.085** | .053** | −.074** | .097** | .187** | .005 | 1 | |||||

| 8. T1 Social Support | .143** | .064** | −.032* | .040* | .043** | −.010 | −.010 | 1 | ||||

| 9. T2 Social Support | .267** | .029 | −.064** | .011 | .059** | −.035* | .005 | .353** | 1 | |||

| 10. T3 Social Support | .237** | .139** | .−.071** | .021 | .080** | −.016 | .022 | .349** | .451** | 1 | ||

| 11. Depression Factor Score | .108** | −.105** | −.116** | .049** | .024 | .043** | .075** | −.100** | −.168** | −.096** | 1 | |

| 12. Neuroticism Factor Score | .117** | −.137** | −.001 | .002 | −.009 | −.001 | .019 | −.085** | −.123** | −.083** | .490** | 1 |

Note. p < .01

p < .05

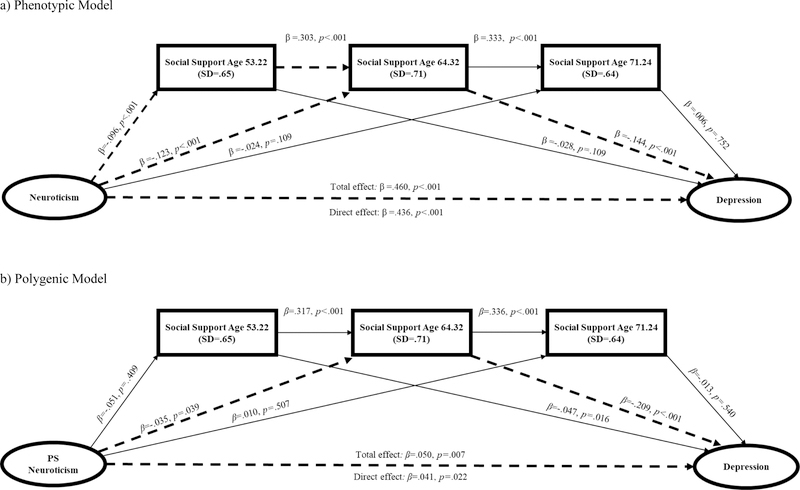

Model 1: Neuroticism → Social Support → Depression1

First, we examined the direct and indirect effects of phenotypic model of neuroticism on late life depression symptoms through the effects of social support measured at T1, T2, and T3 (Table 3). Figure 1a provides the results of each regression path in this model. First, without accounting for the effects of social support, neuroticism was significantly associated with depression (β=.460, p<.001) (i.e., total effects model). After accounting for the mediators (i.e., direct effects model), the relationship between neuroticism and depression was relatively weaker but still significant (β=.436, p<.001). The 95% CI for the specific indirect effect of neuroticism on depression through the serial effects T1 and T2 social support, and through the effect of T2 social support alone, were above zero (95% CIs=.003, .007 and .013, .026, respectively). There was no evidence of an indirect effect of neuroticism on depression through the effects of social support at T3.

Table 3.

Bootstrapped 95% CIs of the total and specific indirect effects (standardized) for Models 1–3

| Phenotypic Model | Polygenic Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI lower | 95% CI upper | 95% CI lower | 95% CI upper | |

| Model 1 | ||||

| Total indirect effects | .018 | .034 | .001 | .018 |

| Neuroticism → T1 social support → Depression | −.001 | .007 | −.001 | .004 |

| Neuroticism → T1 social support → T2 social support → Depression | .003 | .007 | −.001 | .004 |

| Neuroticism → T1 social support → T3 social support → Depression | −.001 | .001 | −.001 | .001 |

| Neuroticism → T1 social support → T2 social support → T3 social support → Depression | −.001 | .001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Neuroticism → T2 social support → Depression | .013 | .026 | .001 | .015 |

| Neuroticism → T2 social support → T3 social support → Depression | −.002 | .001 | <.001 | .001 |

| Neuroticism → T3 social support → Depression | −.002 | .001 | −.002 | .001 |

| Model 2 | ||||

| Total indirect effects | .001 | .007 | <.001 | .008 |

| Neuroticism → Adult dependent SLEs → Depression | −.002 | .001 | <.001 | .002 |

| Neuroticism → Adult dependent SLEs → Late life dependent SLEs → Depression | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Neuroticism → Late life dependent SLEs → Depression | .001 | .007 | .001 | .007 |

| Model 3 | ||||

| Total indirect effects | −.002 | .002 | −.002 | .002 |

| Neuroticism → Adult independent SLEs → Depression | −.001 | .002 | −.002 | .001 |

| Neuroticism → Adult independent SLEs → Late life independent SLEs → Depression | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Neuroticism → Late life independent SLEs → Depression | −.002 | .001 | −.001 | .001 |

Note. Bolded font represents statistically significant indirect pathways.

Figure 1.

Standardized regression paths for Model 1: Neuroticism/PRS → Social Support → Depression

Note. Dotted lines represent statistically significant indirect effect pathways.

Next, we examined the direct and indirect effects of the polygenic model of neuroticism on late life depression through the effects of social support measured at T1, T2 and T3 (Table 3). Results from this model were in line with the phenotypic model of neuroticism (Figure 1b). Without accounting for the effects of social support, the PS for neuroticism was significantly associated with depression (β=.050, p=.007) (total effects model). After accounting for the effects of social support, the association between the PS for neuroticism and depression was relatively weaker but still significant (β=.041, p=.022) (direct effects model). Only the 95% CI for the specific indirect effect of the PS for neuroticism on depression through the effects T2 social support was above zero (95% CI=.001, .015), which is consistent with findings from the phenotypic model of neuroticism.

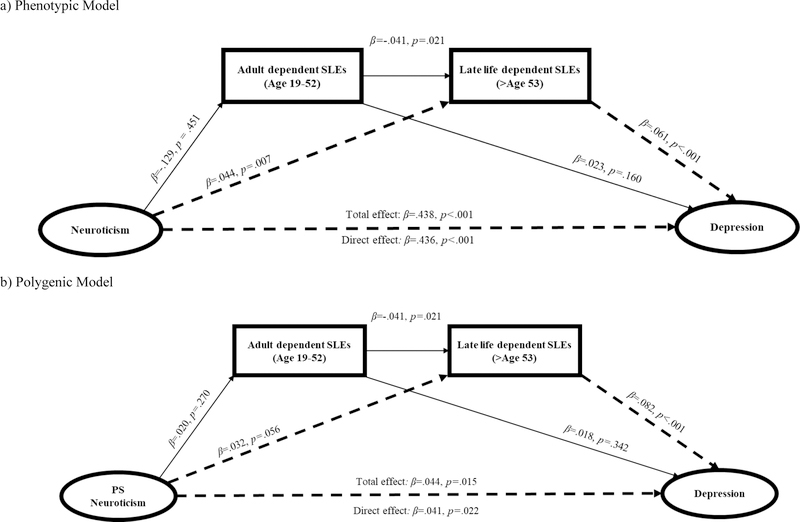

Model 2: Neuroticism → Dependent SLEs → Depression

Next, we examined the direct and indirect effects of the phenotypic model of neuroticism on late life depression symptoms through the effects of dependent SLEs experienced during adulthood (age 19 – 52) and late life (after age 53) (Table 3 and Figure 2a). Without accounting for the effects of dependent SLEs, neuroticism was significantly associated with depression (β=.438, p<.001) (total effects model). After accounting for the effects of dependent SLEs, the association between neuroticism and depression was relatively weaker but still significant (β=.436, p<.001) (direct effects model). Only the 95% CI for the specific indirect effect of neuroticism on depression through the effects of late life dependent SLEs was significant (95% CI=.001, .007). There was no evidence of an indirect effect of neuroticism on depression through the effects of adult dependent SLEs.

Figure 2.

Standardized regression paths for Model 2: Neuroticism/PRS → Dependent SLEs → Depression

Note. Dotted lines represent statistically significant indirect effect pathways.

We then examined the direct and indirect effects of the polygenic model of neuroticism on depression through the effects of dependent SLEs (Table 3). Results of the polygenic model largely replicated results from the phenotypic model (Figure 2b). Without accounting for dependent SLEs, the PS for neuroticism was significantly associated with depression (β=.044, p=.015). After accounting for the effects of dependent SLEs, the association between the PS for neuroticism and depression was relatively weaker but still significant (β=.041, p=.022). Only the 95% CI for the specific indirect effect of the PS for neuroticism on depression through the effects of late life dependent SLEs was significant (95% CI=.001, .007). Once again, there was no evidence of an indirect effect of the PS for neuroticism on depression through the effects of adult dependent SLEs.

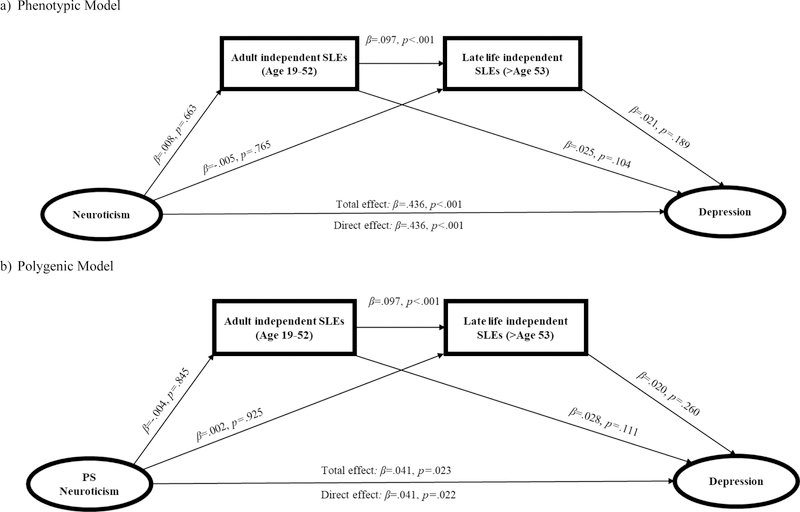

Model 3: Neuroticism → Independent SLEs → Depression

Finally, we examined the direct and indirect effects of the phenotypic model of neuroticism on late life depression symptoms through the effects of independent SLEs experienced during adulthood (age 19 – 52) and late life (after age 53) (Table 3 and Figure 3a). Without accounting for independent SLEs, neuroticism was significantly associated with depression (β=.436, p<.001). After accounting for the effects of independent SLEs, there was no change in the association between neuroticism and depression (β=.436, p<.001). Thus, as hypothesized there was no evidence of any indirect effects of neuroticism on depression through the effects of either adult independent SLEs or late life independent SLEs.

Figure 3.

Standardized regression paths for Model 3: Neuroticism/PRS → Independent SLEs → Depression

We then examined the direct and indirect effects of the polygenic model of neuroticism on depression through the effects of independent SLEs experienced during adulthood and late life (Table 3 and Figure 3b). Without accounting for independent SLEs, the PS for neuroticism was significantly associated with depression (β=.041, p=.023). After accounting for independent SLEs, there was no difference in the association between the PS for neuroticism and depression (β=.041, p=.022). As hypothesized, there was no evidence of indirect effects of the PS for neuroticism on depression through the effects of either adult or late life independent SLEs.

Discussion

This study examined associations between neuroticism, SLEs, social support, and late life depression over a nearly 20-year span using longitudinal data from WLS. To address concerns about potential rater bias in the measurement of neuroticism and depression, we assayed neuroticism using both self-reports and PS for neuroticism. As expected, we found significant main effects of self-reported neuroticism on late life depression. However, the association between self-reported neuroticism and depression was partially mediated through the effects of T1 and T2 social support (when participants were a mean age of 53 and 64 respectively) and late life dependent SLEs (SLEs experienced after the age of 53). There were no specific indirect effects of self-reported neuroticism on depression through the effects of T3 social support (mean age 71), adult dependent SLEs (SLEs experienced between age 19 and 52), and adult and late life independent SLEs. Crucially, these associations were almost entirely replicated in our polygenic models of neuroticism.

Neuroticism was negatively associated with social support, which in turn was negatively associated with late life depression symptoms. This replicates findings from previous studies, albeit in smaller samples (Finch & Graziano, 2001; Lara et al., 1997). Notably, we found an indirect effect of neuroticism on depression through the effects of social support at T1 and T2 (mean age 53 and 64). The latter time point aligns with the average age of retirement in the United States, and although we did not explicitly examine the role of retirement status as it pertained to neuroticism and late life depression, previous studies have found that individuals with fewer social-relational resources are more likely to have increased risk of depression and poorer psychological well-being during their transition into retirement (Kim & Moen, 2001, 2002). Personality factors have also been shown to play a crucial role in adapting to retirement (Löckenhoff, Terracciano, & Costa, 2009). Taken together, our findings suggest that individuals high on neuroticism may be especially more prone to late life depression as a result of having fewer social supports during this major life transition (Chen & Feeley, 2014). One important note is that perceived social support may differ from received social support (e.g., number of friends and family members who provide support in times of need). Individuals high on neuroticism have been shown to overestimate negative conflict and underestimate positive support (Shurgot & Knight, 2005). Although we found no association between neuroticism and social support at T3 in either of our models, future studies should attempt to substantiate measures of social support by using multiple informants and/or measures.

Next, we found that the association between neuroticism and late life depression was partially mediated by late life dependent SLEs (experienced after age 53). Consistent with our hypothesis, we found no evidence of an indirect effect of neuroticism on late life depression through the effects of independent SLEs. This supports the theory that individuals with high neuroticism may be more likely to generate SLEs that are (in part) attributable to the individual (Hammen, 1991; Kendler, Prescott, Myers, & Neale, 2003; Os et al., 2001), which in turn, predicts greater depression symptoms later on. Importantly, these findings generalize to an older adult population in WLS. One interpretation is that financial problems may be particularly salient for late life depression because they are among the most robust risk factors for suicide and depression in later life (Conwell, Duberstein, & Caine, 2002), and high levels of neuroticism are robustly associated with worse socioeconomic outcomes (Chapman, Fiscella, Kawachi, & Duberstein, 2010). Although other aspects of dependent SLEs were not assessed in the current study (e.g., relationship difficulties), our data support the notion that individuals with high neuroticism may be more prone to late life depression via the effects of dependent (but not independent) SLEs.

Crucially, we replicated each of our mediation models when we tested the direct and indirect effects of PS for neuroticism on late depression as well. Convergence of the phenotypic and polygenic models of neuroticism provides key evidence that pathways between neuroticism and late life depression may be partially mediated by social support and dependent SLEs, independent from potential methodological confounds when measuring neuroticism and depression (Lahey, 2009; Ormel et al., 2004). Two important issues with regard to these findings are worth noting.

First, the effect of PS for neuroticism on depression was significantly weaker (in both total and direct effects models) relative to parallel associations in the phenotypic model. On the one hand, the relatively larger effects of the phenotypic models for neuroticism on depression may be somewhat exaggerated due to methodological confounds, such as rater bias. These associations, where participant self-reports on Trait A are meant to predict self-reported Trait B, are especially vulnerable to Type I error. In addition to having adequate power in a study sample, replicating these associations with different measurement methods provides an additional check on Type 1 error. On the other hand, the relatively smaller (but still significant) effects of the polygenic model for neuroticism on depression may be attenuated because polygenic effect sizes are directly linked to the size of the GWAS discovery sample, which are continually growing (Wood et al., 2014). Traits with only moderate heritability may potentially require even larger samples relative to model traits (e.g., human height) to achieve comparable gains in terms of variance explained. Ongoing efforts by the Social Science Genetic Association Consortium ensure that polygenic effect sizes relevant to psychiatric phenotypes should continue to climb as more data are being collected.

Second, although candidate gene-environment interactions have been well studied in depression (Lesch, 2004; Risch et al., 2009), few studies have focused on gene-environment correlations. Gene-environment correlations confound interpretations of gene-environment interactions and play an important causal role in mental illnesses (Knafo & Jaffee, 2013). Polygenic influences for neuroticism are complex and likely operate through environmental influences as well as directly on the specific disorders themselves (Li et al., 2017). Future genetically-informed studies of depression should focus on elucidating the pathways (including biological) from genes to behavior, as these studies may help to uncover mechanisms that may be amenable to intervention.

Our findings should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, WLS was almost entirely comprised of individuals of European ancestry, reflecting the demographics of Wisconsin in 1957. Results need to be replicated across racial-ethnic groups, particularly given recent evidence of population differences in the polygenic basis of depression in European and East Asian populations (Bigdeli et al., 2017). Second, only data from 1992, 2004 and 2011 were used in the current study. None of the study variables were assessed in the WLS surveys conducted prior to 1992, precluding our ability to examine the development of depression across the lifespan. Third, predictors should temporally precede downstream variables in a serial mediation model but some of the assessments of neuroticism were measured after when the SLEs and social support were measured. We viewed each neuroticism assessment as factor loadings on to a single latent dimension of neuroticism, providing more precise estimates for each individual. Fourth, we detected only a marginal attenuation of the association between neuroticism and depression after accounting for the mediators. This likely reflects the multitude of potential risk pathways leading to late life depression that were not tested in the current study. We note that even though effect sizes we detected were small, the concordance of findings across completely divergent methodologies (i.e., polygenic scores vs. self-reports) provides confidence that the findings are robust and replicable. Finally, this investigation did not assess other internalizing problems that are known to covary with depression. More complex phenotypic models that account of the shared genetic underpinnings of co-occurring phenotypes are needed in future studies of late life depression.

The current study is innovative for incorporating prospective longitudinal data spanning nearly 20 years in the late adult life course with individual level genome-wide information to validate two key psychosocial mechanisms between neuroticism and late life depression. Incorporating genetic information may be especially useful as a method to validate hypotheses, an important endeavor given the high rates of failure to replicate in psychology (Maxwell, Lau, & Howard, 2015). We look forward to other methods to validate association studies of complex behavioral constructs, especially as publicly available genotypic and phenotypic databases grow [e.g., database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP)].

Acknowledgments

This research uses data from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (WLS) of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Since 1991, the WLS has been supported principally by the National Institute on Aging (AG-9775, AG-21079, AG-033285, and AG-041868), with additional support from the Vilas Estate Trust, the National Science Foundation, the Spencer Foundation, and the Graduate School of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Since 1992, data have been collected by the University of Wisconsin Survey Center. A public use file of data from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study is available from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1180 Observatory Drive, Madison, Wisconsin 53706 and at http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/wlsresearch/data/. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors.

This study complies with APA ethical standards in the treatment of participants. The study was approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Institutional Review Board (IRB) (Study Name: Nonnormative Parenting in Old Age: Pathways to Resiliency and Vulnerability, IRB #2017–0618).

This study was supported in part by a core grant to the Waisman Center from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U54 HD090256) and by the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF). A preprint of this manuscript has been posted on the Center for Open Science Preprints website at the following URL: osf.io/px4tm.

Footnotes

We also tested a simple mediation model with temporally separated variables, i.e., T1 neuroticism → T2 social support → T3 depression symptoms. Results of this model replicated the serial mediation model reported herein. Results are available upon request.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Allen B, & Lauterbach D (2007). Personality characteristics of adult survivors of childhood trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20(4), 587–595. 10.1002/jts.20195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anusic I, & Schimmack U (2016). Stability and change of personality traits, self-esteem, and well-being: Introducing the meta-analytic stability and change model of retest correlations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 110(5), 766–781. 10.1037/pspp0000066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, & Kenny DA (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beekman ATF, Geerlings SW, Deeg DJH, Smit JH, Schoevers RS, Beurs E. de, … Tilburg W. van. (2002). The Natural History of Late-Life Depression: A 6-Year Prospective Study in the Community. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59(7), 605–611. 10.1001/archpsyc.59.7.605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigdeli TB, Ripke S, Peterson RE, Trzaskowski M, Bacanu S-A, Abdellaoui A, … Kendler KS (2017). Genetic effects influencing risk for major depressive disorder in China and Europe. Translational Psychiatry, 7(3), e1074 10.1038/tp.2016.292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boomsma DI, Helmer Q, Nieuwboer HA, Hottenga JJ, Moor M. H. de, Berg S. M. van den, … Geus E. J. de. (2018). An Extended Twin-Pedigree Study of Neuroticism in the Netherlands Twin Register. Behavior Genetics, 48(1), 1–11. 10.1007/s10519-017-9872-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butters MA, Whyte EM, Nebes RD, Begley AE, Dew MA, Mulsant BH, … Becker JT (2004). The Nature and Determinants of Neuropsychological Functioning in Late-Life Depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61(6), 587–595. 10.1001/archpsyc.61.6.587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman BP, Fiscella K, Kawachi I, & Duberstein PR (2010). Personality, Socioeconomic Status, and All-Cause Mortality in the United States. American Journal of Epidemiology, 171(1), 83–92. 10.1093/aje/kwp323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, & Feeley TH (2014). Social support, social strain, loneliness, and well-being among older adults: An analysis of the Health and Retirement Study. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 31(2), 141–161. 10.1177/0265407513488728 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng T (2018). Late-Life Depression. In Geriatric Psychiatry (pp. 219–235). Springer, Cham; 10.1007/978-3-319-67555-8_10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Claridge G, & Davis C (2001). What’s the use of neuroticism? Personality and Individual Differences, 31(3), 383–400. 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00144-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colby (2014). Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060. U.S. Census Bureau, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, & Lanza ST (2013). Latent Class and Latent Transition Analysis: With Applications in the Social, Behavioral, and Health Sciences John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, & Caine ED (2002). Risk factors for suicide in later life. Biological Psychiatry, 52(3), 193–204. 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01347-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, & McCrae RR (1992). The Five-Factor Model of Personality and Its Relevance to Personality Disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 6(4), 343–359. 10.1521/pedi.1992.6.4.343 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dines P, Hu W, & Sajatovic M (2014). Depression in later life: An overview of assessment and management. Psychiatria Danubina, 26, 7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diniz BS, Butters MA, Albert SM, Dew MA, & Reynolds CF (2013). Late-life depression and risk of vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based cohort studies. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 202(5), 329–335. 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.118307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanous A, Gardner CO, Prescott CA, Cancro R, & Kendler KS (2002). Neuroticism, major depression and gender: a population-based twin study. Psychological Medicine, 32(4), 719–728. 10.1017/S003329170200541X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson E (2013). Personality is of central concern to understand health: towards a theoretical model for health psychology. Health Psychology Review, 7(sup1), S32–S70. 10.1080/17437199.2010.547985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch JF, & Graziano WG (2001). Predicting Depression From Temperament, Personality, and Patterns of Social Relations. Journal of Personality, 69(1), 27–55. 10.1111/1467-6494.00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale CR, Hagenaars SP, Davies G, Hill WD, Liewald DCM, Cullen B, … Harris SE (2016). Pleiotropy between neuroticism and physical and mental health: findings from 108 038 men and women in UK Biobank. Translational Psychiatry, 6(4), e791 10.1038/tp.2016.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Cox BJ, & Clara I (2006). Neuroticism and Physical Disorders Among Adults in the Community: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29(3), 229–238. 10.1007/s10865-006-9048-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C (1991). Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(4), 555–561. 10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herd P, Carr D, & Roan C (2014). Cohort Profile: Wisconsin longitudinal study (WLS). International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(1), 34–41. 10.1093/ije/dys194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S-I, Hasche L, & Bowland S (2009). Structural Relationships Between Social Activities and Longitudinal Trajectories of Depression Among Older Adults. The Gerontologist, 49(1), 1–11. 10.1093/geront/gnp006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacovino JM, Bogdan R, & Oltmanns TF (2016). Personality Predicts Health Declines Through Stressful Life Events During Late Mid-Life. Journal of Personality, 84(4), 536–546. 10.1111/jopy.12179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, & Gardner CO (2016). Depressive vulnerability, stressful life events and episode onset of major depression: a longitudinal model. Psychological Medicine, 46(9), 1865–1874. 10.1017/S0033291716000349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Gardner CO, & Prescott CA (2005). Toward a Comprehensive Developmental Model for Major Depression in Women. FOCUS, 3(1), 83–97. 10.1176/foc.3.1.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Gatz M, Gardner CO, & Pedersen NL (2006). Personality and Major Depression: A Swedish Longitudinal, Population-Based Twin Study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(10), 1113–1120. 10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, & Prescott CA (1999). Causal Relationship Between Stressful Life Events and the Onset of Major Depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156(6), 837–841. 10.1176/ajp.156.6.837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Kuhn J, & Prescott CA (2004). The Interrelationship of Neuroticism, Sex, and Stressful Life Events in the Prediction of Episodes of Major Depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(4), 631–636. 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Prescott CA, Myers J, & Neale MC (2003). The Structure of Genetic and Environmental Risk Factors for Common Psychiatric and Substance Use Disorders in Men and Women. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(9), 929–937. 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kercher AJ, Rapee RM, & Schniering CA (2009). Neuroticism, Life Events and Negative Thoughts in the Development of Depression in Adolescent Girls. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(7), 903–915. 10.1007/s10802-009-9325-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JE, & Moen P (2001). Is Retirement Good or Bad for Subjective Well-Being? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10(3), 83–86. 10.1111/1467-8721.00121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JE, & Moen P (2002). Retirement Transitions, Gender, and Psychological Well-BeingA Life-Course, Ecological Model. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 57(3), P212–P222. 10.1093/geronb/57.3.P212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knafo A, & Jaffee SR (2013). Gene–environment correlation in developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 25(1), 1–6. 10.1017/S0954579412000855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotov R, Gamez W, Schmidt F, & Watson D (2010). Linking “big” personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136(5), 768–821. 10.1037/a0020327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraaij V, Arensman E, & Spinhoven P (2002). Negative Life Events and Depression in Elderly PersonsA Meta-Analysis. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 57(1), P87–P94. 10.1093/geronb/57.1.P87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB (2009). Public Health Significance of Neuroticism. The American Psychologist, 64(4), 241–256. 10.1037/a0015309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara ME, Leader J, & Klein DN (1997). The association between social support and course of depression: Is it confounded with personality? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106(3), 478–482. 10.1037/0021-843X.106.3.478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehto K, Karlsson I, Lundholm C, & Pedersen NL (2018). Genetic risk for neuroticism predicts emotional health depending on childhood adversity. Psychological Medicine, 1–8. 10.1017/S0033291718000715 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lesch KP (2004). Gene–environment interaction and the genetics of depression. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 29(3), 174–184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JJ, Savage JE, Kendler KS, Hickman M, Mahedy L, Macleod J, … Dick DM (2017). Polygenic Risk, Personality Dimensions, and Adolescent Alcohol Use Problems: A Longitudinal Study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 78(3), 442–451. 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löckenhoff CE, Terracciano A, & Costa PT (2009). Five-factor Model Personality Traits and the Retirement Transition: Longitudinal and Cross-sectional Associations. Psychology and Aging, 24(3), 722–728. 10.1037/a0015121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciano M, Hagenaars SP, Davies G, Hill WD, Clarke T-K, Shirali M, … Deary IJ (2018). Association analysis in over 329,000 individuals identifies 116 independent variants influencing neuroticism. Nature Genetics, 50(1), 6–11. 10.1038/s41588-017-0013-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malouff JM, Thorsteinsson EB, & Schutte NS (2005). The Relationship Between the Five-Factor Model of Personality and Symptoms of Clinical Disorders: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 27(2), 101–114. 10.1007/s10862-005-5384-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell SE, Lau MY, & Howard GS (2015). Is psychology suffering from a replication crisis? What does “failure to replicate” really mean? American Psychologist, 70(6), 487–498. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/10.1037/a0039400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miech RA, & Shanahan MJ (2000). Socioeconomic Status and Depression over the Life Course. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 41(2), 162–176. 10.2307/2676303 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moor M. H. M. de, Berg S. M. van den, Verweij KJH, Krueger RF, Luciano M, Vasquez AA, … Boomsma DI (2015). Meta-analysis of Genome-wide Association Studies for Neuroticism, and the Polygenic Association With Major Depressive Disorder. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(7), 642–650. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel M, Jansen PR, Stringer S, Watanabe K, Leeuw C. A. de, Bryois J, … Posthuma D (2017). GWAS Meta-Analysis of Neuroticism (N=449,484) Identifies Novel Genetic Loci and Pathways. BioRxiv, 184820 10.1101/184820 [DOI]

- Nivard MG, Middeldorp CM, Dolan CV, & Boomsma DI (2015). Genetic and Environmental Stability of Neuroticism From Adolescence to Adulthood. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 18(6), 746–754. 10.1017/thg.2015.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okbay A, Baselmans BML, Neve J-ED, Turley P, Nivard MG, Fontana MA, … Cesarini D (2016). Genetic variants associated with subjective well-being, depressive symptoms, and neuroticism identified through genome-wide analyses. Nature Genetics, 48(6), 624–633. 10.1038/ng.3552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormel J, Oldehinkel AJ, & Brilman EI (2001). The Interplay and Etiological Continuity of Neuroticism, Difficulties, and Life Events in the Etiology of Major and Subsyndromal, First and Recurrent Depressive Episodes in Later Life. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(6), 885–891. 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.6.885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormel J, Rosmalen J, & Farmer A (2004). Neuroticism: a non-informative marker of vulnerability to psychopathology. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 39(11), 906–912. 10.1007/s00127-004-0873-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Os JV, Park SBG, & Jones PB (2001). Neuroticism, life events and mental health: evidence for person-environment correlation. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 178(S40), s72–s77. 10.1192/bjp.178.40.s72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R, Haworth CMA, & Davis OSP (2009). Common disorders are quantitative traits. Nature Reviews Genetics, 10(12), 872–878. 10.1038/nrg2670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Risch N, Herrell R, Lehner T, Liang K-Y, Eaves L, Hoh J, … Merikangas KR (2009). Interaction Between the Serotonin Transporter Gene (5-HTTLPR), Stressful Life Events, and Risk of Depression: A Meta-analysis. JAMA, 301(23), 2462–2471. 10.1001/jama.2009.878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosmalen JGM, Neeleman J, Gans ROB, & Jonge P de. (2007). The association between neuroticism and self-reported common somatic symptoms in a population cohort. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 62(3), 305–311. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueger SY, Malecki CK, Pyun Y, Aycock C, & Coyle S (2016). A meta-analytic review of the association between perceived social support and depression in childhood and adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 142(10), 1017–1067. 10.1037/bul0000058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzbach M, Luppa M, Forstmeier S, König H-H, & Riedel‐Heller SG (2013). Social relations and depression in late life—A systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(1), 1–21. 10.1002/gps.3971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shurgot GR, & Knight BG (2005). Influence of Neuroticism, Ethnicity, Familism, and Social Support on Perceived Burden in Dementia Caregivers: Pilot Test of the Transactional Stress and Social Support Model. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 60(6), P331–P334. 10.1093/geronb/60.6.P331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spijker J, Graaf R. de, Oldehinkel AJ, Nolen WA, & Ormel J (2007). Are the vulnerability effects of personality and psychosocial functioning on depression accounted for by subthreshold symptoms? Depression and Anxiety, 24(7), 472–478. 10.1002/da.20252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steunenberg B, Twisk JWR, Beekman ATF, Deeg DJH, & Kerkhof AJFM (2005). Stability and Change of Neuroticism in Aging. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 60(1), P27–P33. 10.1093/geronb/60.1.P27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The International Schizophrenia Consortium. (2009). Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nature, 460(7256), 748–752. 10.1038/nature08185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vukasović T, & Bratko D (2015). Heritability of personality: A meta-analysis of behavior genetic studies. Psychological Bulletin, 141(4), 769–785. 10.1037/bul0000017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood AR, Esko T, Yang J, Vedantam S, Pers TH, Gustafsson S, … Frayling TM (2014). Defining the role of common variation in the genomic and biological architecture of adult human height. Nature Genetics, 46(11), 1173–1186. 10.1038/ng.3097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y (2007). Is Old Age Depressing? Growth Trajectories and Cohort Variations in Late-Life Depression, Is Old Age Depressing? Growth Trajectories and Cohort Variations in Late-Life Depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 48(1), 16–32. 10.1177/002214650704800102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]