Abstract

Introduction

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is one of the most common malignancies of gastrointestinal tract in the world, and the long-term prognosis for ESCC patients still remains dismal due to the lack of effective early diagnosis biomarkers.

Materials and methods

Western blot and immunochemistry were used to determine the expression of PRR11 in 201 clinicopathologically characterized ESCC specimens. The effects of PRR11 on stem cell-like traits and tumorigenicity were examined by tumor sphere formation assay and SP assays in vitro and by a tumorigenesis model in vivo. The mechanism by which PRR11 mediated Wnt/β-catenin signaling was explored using luciferase reporter, immuno-chemistry, and real time-PCR (RT-PCR) assays.

Results

We found that PRR11 was markedly upregulated, at the level of both transcription and translation, in ESCC cell lines as compared with normal esophageal epithelial cells (NECCs). Immunohistochemical analysis showed that 69.2% paraffin-embedded archival ESCC specimens exhibited high levels of PRR11 expression, and multivariate analysis revealed that PRR11 upregulation might be an independent prognostic indicator for the survival of patients with ESCC. Furthermore, overexpression of PRR11 dramatically enhanced, whereas inhibition of PRR11 reduced the capability of cancer stem cell (CSC)-like phenotypes and tumorigenicity of ESCC cells both in vitro and in vivo. Mechanically, we demonstrated PRR11-enhanced tumorigenicity of ESCC cells via activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling, and PRR11 expression is found to be significantly correlated with β-catenin nuclear location in ESCC.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that the PRR11 might represent a novel and valuable prognostic marker for ESCC progression and play a role during the development and progression of this malignancy.

Keywords: PRR11, CSC-like phenotypes, tumorigenesis, Wnt/β-catenin, ESCC

Introduction

Esophageal carcinoma, one of the most common malignancies of the digestive system, is the 6th most common cause of cancer-related death in the world.1–3 Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is one of the major histological types of esophageal carcinoma, which ranks the 6th in mortality and the 7th in incidence in China with great variations in geography, ethnicity, and sociocultures.4 In spite of the recent advances in surgical techniques and adjuvant therapy, patients afflicted with ESCC exhibit poor prognosis with an average 5-year survival rate of 10%–20%.5–7 Unfortunately, the prediction of clinical prognosis of ESCC patients based on conventional pathological variables, such as tumor size, tumor grade, and tumor stage, is still highly empirical.8–10 Interestingly, Cheng et al11 demonstrated that tryptophan metabolism confers tumorigenesis and metastasis to ESCC, which help biologists to investigate the mechanism of the disease. Moreover, Cheng et al12 showed that tyrosine metabolism is disturbed in ESCC patients, suggesting that the metabolites involved in the tyrosine pathway can be used as diagnostic biomarkers of the disease. Therefore, identifying sensitive and specific early biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of this aggressive tumor is needed urgently.

The novel tumor-related gene, proline-rich protein 11 (PRR11), is located on chromosome 17q22 and encodes a 360-amino acid protein. Bioinformatic analysis revealed that PRR11 contains 2 proline-rich regions and 1 zinc-finger domain. Zinc-finger domain is a well-known domain that can bind double-stranded DNA and modulate gene transcription.13,14 The proline-rich motif can bind with SH3 domains or WW domain and mediate protein–protein interactions involved in cellular signaling events, such as PI3K and YAP signaling, and its abnormal activation contributed to tumorigenesis.15–18 Consistent with this functional domain analysis, Ji et al19 showed that PRR11 played an important role in cell cycle, tumorigenesis, and metastasis by regulating the expression of genes (eg, CCNA1, RRM1, MAP4K4, and EPB41L3), which might serve as a novel potential target in the diagnosis and treatment of human lung cancer. A new study also showed that PRR11 is strictly regulated during cell cycle progression and induces premature chromatin condensation (PCC) in human lung carcinoma-derived H1299 cells.20 In addition, by using quantitative proteomics analysis, Larance et al21 revealed that PRR11 is identified as rapidly degraded proteasome targets in ESCC cells and highlighted a feedback mechanism resulting in translation inhibition. Previous studies indicated that PRR11 might involve in cancer development and progression; however, the expression and clinical significance of PRR11 in ESCC still remain unclear. Thus, it is of importance to investigate the expression of PRR11 associated with clinical pathological factors including the prognosis of patients with ESCC.

Cancer stem cells (CSCs), a small subpopulation with stem-like properties, are capable of multilineage differentiation potential, which results in metastasis, chemotherapy resistance, and recurrence in many cancers, including ESCC.22–25 For example, the proportions of both CD90+ and CD271+ cells in ESCC were dramatically increased in chemoresistant ESCC cells and confers self-renewal and tumor initiation capability.26 Wang et al27 demonstrated that CD90 overexpressing ESCC cells exhibit CSC-like characteristics and radiation resistance, which inhibits apoptosis and could exhibit more local invasion as well as distant metastasis. Gao et al22 suggested that SOX2 promoted the metastasis of ESCC by modulating Slug expression through the activation of STAT3/HIF-1α signaling. Therefore, targeting CSCs might improve the cure rates and survival of patients with ESCC.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

Primary cultures of normal esophageal epithelial cells (NEECs) were established from fresh specimens of the adjacent non-cancerous esophageal tissue, which is over 5 cm from the cancerous tissue, according to the previous report.28 The NEECs were grown at 37°C and 5% CO2 in keratinocyte serum-free medium, with 40 μg/mL bovine pituitary extract, 1.0 ng/mL EGF, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. The esophageal cancer cell lines EC18, ECA109, and HKESC1 were kindly provided by Professors Tsao SW, Srivastava G (The University of Hong Kong). ESCC cell lines KYSE30, KYSE140, KYSE180, KYSE410, KYSE510, and KYSE520 were obtained from Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen, the German Resource Centre for Biological Material.29 These cell lines were grown in DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA). All cell lines were authenticated by short tandem repeat (STR) fingerprinting at Medicine Lab of Forensic Medicine Department of Sun Yat-Sen University (Guangzhou, China).

Tissue specimens and clinicopathological characteristics

The total 201 paraffin-embedded, archived ESCC samples used in this study were histopathologically and clinically diagnosed at The First Affiliated Hospital of Clinical Medicine of Guangdong Pharmaceutical University between 2003 and 2009. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Clinical Medicine of Guangdong Pharmaceutical University. Clinical staging and clinicopathological TNM classification were determined according to the criteria proposed by the International Union Against Cancer. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to the study. The clinicopathological characteristics of the samples are summarized in Table S1. Eight freshly collected ESCC tissues and matched adjacent non-tumor esophageal tissues from the same patient were frozen and stored in liquid nitrogen until required.

Western blotting

For Western blot analysis, the total protein of 8 pairs of ESCC and matched non-neoplastic tissues was extracted using a previously described method.30 The protein was separated using sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and then transferred to an NC membrane (0.45 mm, EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The protein levels were analyzed using the corresponding antibodies as follows: anti-PRR11 antibody (1:500; Novus, Centennial, CO, USA), anti-α-tubulin monoclonal antibody (1:3,000; Sigma-Aldrich Co., St Louis, MO, USA), and anti-β-catenin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). The blotting membranes were stripped and reprobed with an anti-α-tubulin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) as a loading control.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

IHC analysis was performed on the 201 paraffin-embedded ESCC tissue sections,30 using the anti-PRR11 antibody (1:100; Novus). The degree of immunostaining of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections was reviewed and scored separately by 2 independent pathologists. The scores were determined by combining the proportion of positively stained tumor or NEECs and the intensity of staining. Cell proportions were scored as follows: 0, no positive cells; 1, <10% positive cells; 2, 10%–35% positive cells; 3, 35%–75% positive cells; and 4, >75% positive cells. Staining intensity was graded according to the following standard: 1, no staining; 2, weak staining (light yellow); 3, moderate staining (yellow brown); and 4, strong staining (brown). The staining index (SI) was calculated as the product of the staining intensity score and the proportion of positive cells. Using this method of assessment, we evaluated protein expression in benign esophageal epithelia and malignant lesions by determining the SI, with possible scores of 0, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 12, and 16. Samples with an SI of ≥8 were determined as high PRR11 expression and samples with an SI of <8 were determined as low PRR11expression. Cutoff values were determined on the basis of a measure of heterogeneity using the log-rank test with respect to overall survival. Briefly, the stained sections were evaluated at 200× magnification, and 10 representative staining fields of each section were analyzed to verify the mean optical density (MOD), which represents the strength of staining signals as measured per positive pixels. The MOD data were statistically analyzed using t-test to compare the average MOD difference between different groups of tissues, and P<0.05 was considered significant.

RNA extraction, reverse transcription, and real-time PCR (RT-PCR)

Total RNA from cultured cell and surgically obtained tumor tissues was extracted using the Trizol reagent according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Amplification and quantification of cDNA were performed using an ABI Prism 7500 Sequence Detection System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and SYBR Green I dye (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA). Relative gene expression was evaluated by the threshold cycle (Ct) method, normalized to the housekeeping gene GAPDH, according to the formula 2−[(Ct of PRR11) − (Ct of GAPDH)]. RT-PCR primers used are the following:

PRR11 forward: 5′-GACTTCCAAAGCTGTGC TTCC-3′; PRR11 reverse: 5′-CTGCATGGGTCCATCC TTTTT-3′. GAPDH forward: 5′-GACTCATGACCAC AGTCCATGC-3′; GAPDH reverse: 5′-AGAGGCAGGGA TGATGTTCTG-3′.

Vectors, retroviral infection, and transfection

PRR11 expression construct was generated by PCR amplified from cDNA and cloned into the pMSCV plasmid, and short hairpin RNA (shRNA) oligonucleotide sequences targeting PRR11 were cloned into the pSuper-retro-puro viral vector. According to the manufacturer’s instruction, transfection of plasmids was performed using the Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Retroviral production and infection were performed as per the previously reported protocol. The shRNA sequences for PRR11 were as follows: RNAi#1, TTTATTGCATCTCTGATGTTA and RNAi#2, ATCAACATCCAATGCTGGTGC (synthesized by Thermo Fisher Scientific). The siRNA sequence of β-catenin was as follows: ATAGGTGCGCAGGAACTCCTC. Stable cell lines expressing PRR11 or PRR11 shRNA(s) were selected for 10 days with 0.5 μg/mL puromycin 48 h after infection.

Luciferase reporter assay

Cells (1×104) were seeded in triplicate in 48-well plates and allowed to settle for 24 h. One hundred nanograms of the indicated luciferase reporter plasmids or control-luciferase plasmid plus 5 ng of pRL-TK Renilla plasmid (Promega Corporation, Fitchburg, WI, USA) were transfected into the osteosarcoma cells using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Luciferase and renilla signals were measured 48 hours after transfection using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay (Promega Corporation) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Three independent experiments were performed, and the data are presented as mean ± SD.

Tumor sphere formation assay

Six hundred stable cell lines were seeded in 6-well ultra-low cluster plates (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY, USA) for 10 days. Spheres were cultured in DMEM/F12 serum-free medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 2% B27 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 20 ng/mL EGF, and 20 ng/mL bFGF (PeproTech, Offenbach, Germany), 5 μg/mL insulin, and 0.4% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich Co.).

Flow cytometric analysis

Cells were dissociated with trypsin and resuspended at 1×106 cells/mL in DMEM containing 2% FBS and then pre-incubated at 37°C for 30 min with or without 100 μM verapamil (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) to inhibit ABC transporters. The cells were subsequently incubated for 90 min at 37°C with 5 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 (Sigma-Aldrich Co.). Finally, the cells were incubated on ice for 10 min and washed with ice-cold PBS before flow cytometry analysis. The data were analyzed by Summit5.2 (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN, USA).

Chemical reagents

ICG001 was purchased from Selleck (Shanghai, China) and dissolved in DMSO.

Xenografted tumor

All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of The Clinical Medicine of Guangdong Pharmaceutical University, and the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals was followed. The 6-week-old BALB/c-nu mice were randomly divided into 3 groups (n=10 per group). Cells (1×105, 1×104, and 1×103) were inoculated subcutaneously together with Matrigel (final concentration of 25%) into the inguinal folds of the nude mice. Tumor volume was determined using an external caliper and calculated using the equation (L × W2)/2. The mice were sacrificed 35 days after inoculation, and the tumors were excised and subjected to pathological examination.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS 19.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Pearson’s Chi-square test was used for studying the correlation between PRR11 expression and clinicopathological characteristics of ESCC. Survival curves for both PRR11-high and PRR11-low patients were plotted using the Kaplan–Meier method, and statistical differences were compared using a log-rank test. Comparisons between groups were performed using Student’s t-test. Data represent mean ± SD. Bivariate correlations between study variables were calculated by Pearson’s rank correlation coefficients. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics approval and informed consent

The study was performed after obtaining consent from the ethics committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Clinical Medicine of Guangdong Pharmaceutical University and the patients.

Results

PRR11 overexpression correlated with poor prognosis in ESCC

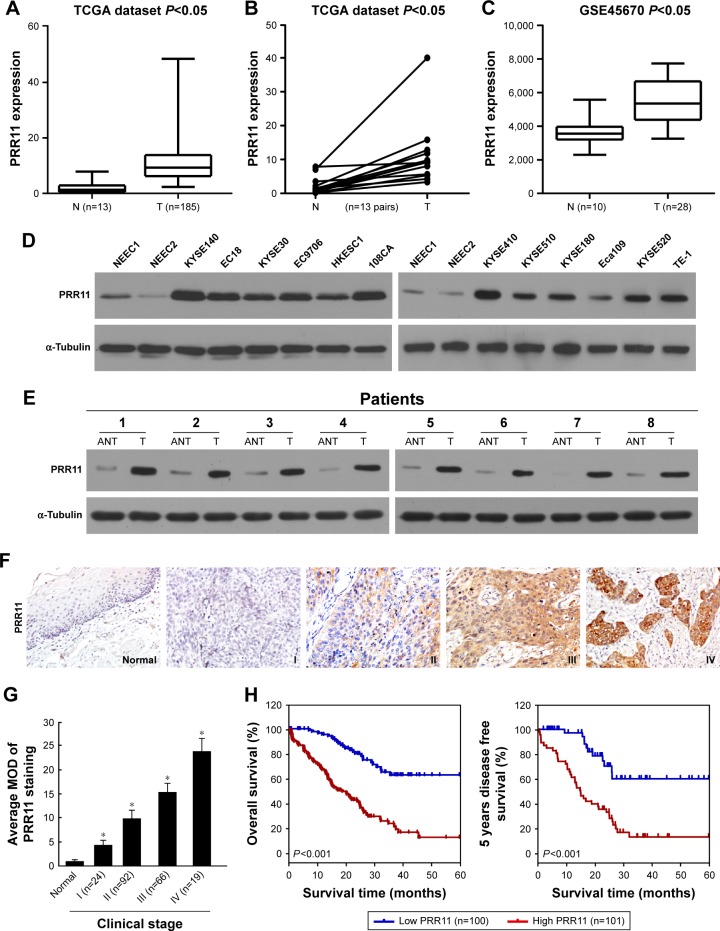

By analyzing the mRNA sequencing datasets of esophageal carcinoma downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (http://cancergenome.nih.gov/, n=198 cases), we found that PRR11 expression was upregulated in esophageal carcinoma tissues compared with non-cancerous tissues (Figure 1A). Consistent with this observation, PRR11 was identified to be significantly upregulated in esophageal carcinoma than in matched non-cancerous tissue (http://cancergenome.nih.gov/, n=13 pairs) (Figure 1B). Furthermore, by analyzing a published microarray-based high-throughput assessment, we found that PRR11 was also identified to be significantly upregulated in ESCC tissues compared with non-cancerous tissues (n=38; P<0.05; NCBI/GEO/GSE45670; Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

mRNA expression analysis shows that PRR11 was upregulated in ESCC cell lines and tissues.

Notes: (A and B) Expression profiling of mRNAs showing that PRR11 is upregulated in ESCC tissues compared with non-cancerous tissue (N) (http://cancergenome.nih.gov/). (C) PRR11 was significantly upregulated in ESCC tissues compared with non-cancerous tissues in published mRNA sequencing datasets (NCBI/GEO/GSE45670). (D) Western blot analysis of PRR11 protein expression in 2 NEECs and 12 cultured ESCC cell lines. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. (E) Western blot analysis of PRR11 protein expression in ESCC tissues (T) with matched adjacent non-tumor tissues (N) from 8 patients. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. (F) Representative images from immunohistochemistry analyses of PRR11 expression in normal esophageal tissues and different clinical stages of ESCC tissues (clinical stages I–IV). (G) The average MOD of PRR11 staining between the adjacent esophageal tissues (4 cases) and different clinical stage ESCC (randomly picked 10 cases per stage) was statistically quantified. The average MOD of PRR11 staining increases as ESCC progresses to more advanced stages (P<0.05). Error bars represent mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. (H) Kaplan– Meier analysis of overall survival and disease-free survival of patients with ESCC was stratified according to low expression and high expression of PRR11. PRR11 upregulation was significantly correlated with shorter overall survival and disease-free survival. Each bar represents mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. *P<0.05.

Abbreviations: ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; MOD, mean optical density; NEECs, normal esophageal epithelial cells.

Interestingly, consistent with the above published data-set, we found that the expression of PRR11, at both mRNA and protein levels, was significantly upregulated in all 12 ESCC cell lines and 8 human ESCC samples, compared with 2 NEECs and the matched adjacent non-tumor tissues, respectively (Figures 1D and E and S1A and B). These results suggest that PRR11 expression is upregulated in ESCC.

Overexpression of PRR11 in archived ESCC tissues

To further evaluate whether PRR11 protein upregulation is associated with clinicopathological characteristics of ESCC, archived ESCC tissues were examined by IHC staining with an antibody against human PRR11. Two hundred one paraffin-embedded archived ESCC tissues were examined by IHC staining, and clinical information about the samples is summarized in Table S1. The samples including 24 cases of stage I, 92 cases of stage II, 66 cases of stage III, and 19 cases of stage IV tumors and the results of the IHC analysis are summarized in Table S2. As shown in Figure 1F, PRR11 was found to be upregulated in advanced clinical stage ESCC compared with normal esophageal tissues. In contrast, PRR11 was barely detectable in the non-cancerous tissues. These results suggest that PRR11 expression is upregulated in archived ESCC tissues. Meanwhile, statistical analysis revealed that PRR11 levels were significantly correlated with the clinical stage (P=0.037), T classification (P<0.001), N classification (P<0.001), and M classification (P=0.02) in patients with ESCC (Table S3). Quantitative analysis indicated that the average MODs of PRR11 staining in clinical stage I–IV primary tumors were statistically significantly higher than those in adjacent non-cancerous esophageal tissues (P<0.001; Figure 1G). Importantly, high PRR11 expression was found to be associated with shorter overall survival and poorer disease-free survival in ESCC (P<0.001; P<0.001; Figure 1H). Taken together, these observations suggested that overexpression of PRR11 was associated with the clinical development of ESCC.

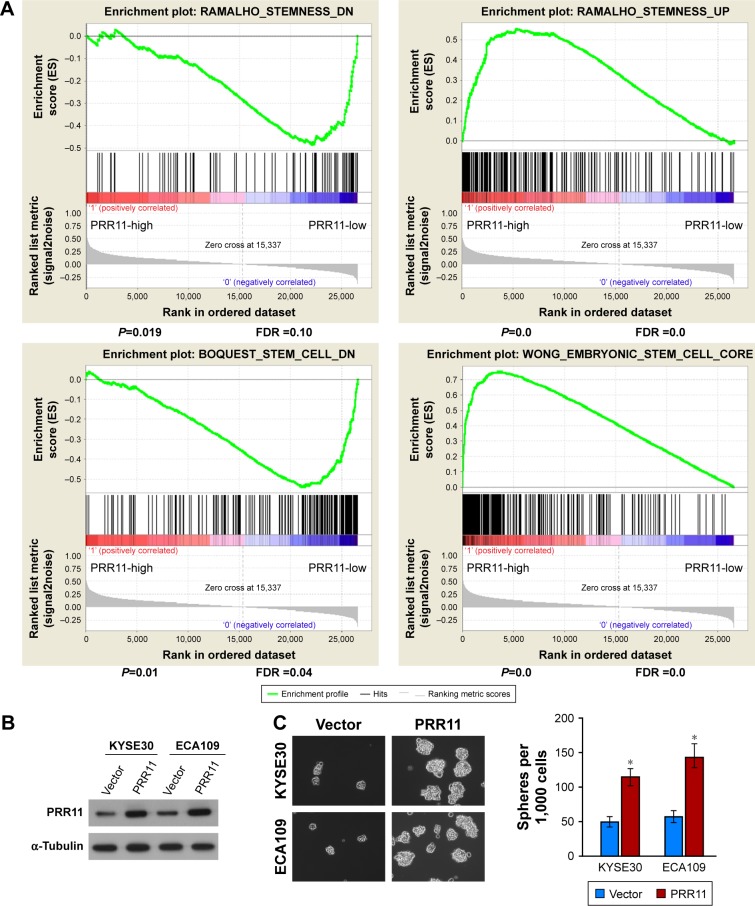

Upregulation of PRR11 promoted stem cell-like traits of human ESCC cells in vitro

It is well known that CSCs play important role in tumorigenesis and are responsible for tumor recurrence. Interestingly, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) revealed that PRR11 overexpression strongly correlated with gene signatures associated with stem cell-like traits, suggesting that PRR11 overexpression might contribute to stem cell-like traits in ESCC (Figure 2A). To determine whether PRR11 plays a role in maintaining self-renewal of CSCs in ESCC in vitro, the effect of PRR11 overexpression on stem cell-like traits was examined (Figure 2B). As shown in Figure 2C, tumor sphere formation assay showed that PRR11-transduced cells formed more spheres compared with the spheres formed by vector control cells, suggesting overexpression of PRR11-promoted tumorigenic capability of ESCC cells in vitro (Figure 2C). Furthermore, we found that PRR11 overexpression dramatically increased the proportion of SP+ cells, a subpopulation of cells that process stem cell-like traits in KYSE30 and ECA109 cells (Figure 2D). Meanwhile, multiple pluripotency-associated factors, including OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, BMI1, and ABCG2, were detected to be upregulated in PRR11-overexpressing ESCC cells (Figure 2E). Collectively, these results indicated that upregulation of PRR11 promoted stem cell-like traits of ESCC cells in vitro.

Figure 2.

Upregulation of PRR11 expression promotes ESCC stem cell-like traits in vitro.

Notes: (A) GSEA plot showing that PRR11 expression positively correlated with cancer stem cell signaling pathway. (B) Western blotting analysis of PRR11 expression in KYSE30 and ECA109 cells stably overexpressing PRR11. (C) Representative micrographs of tumor spheres formed by the indicated cells. Histograms show the mean number of tumor spheres formed by the indicated cells. (D) Hoechst 33342 dye exclusion assay showing that the overexpression of PRR11 promoted the SP+ subpopulation. (E) Real-time PCR of mRNA expression of the pluripotency-associated factors in indicated cells. Transcript levels were normalized to GAPDH expression. Error bars represent mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. *P<0.05.

Abbreviations: ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; GSEA, gene set enrichment analysis.

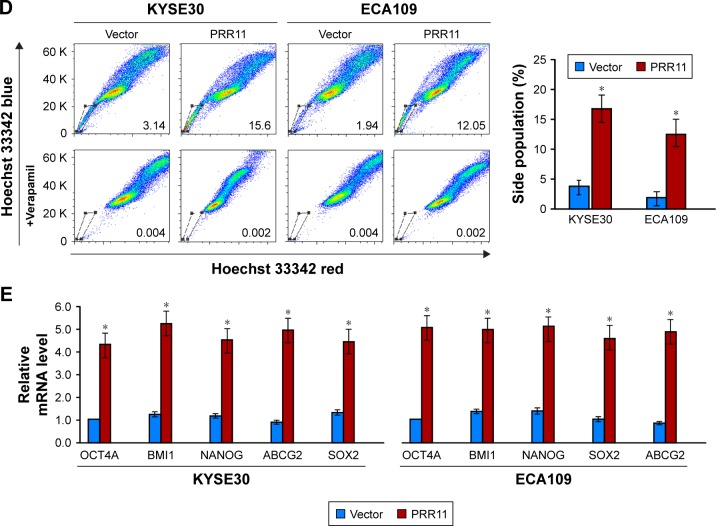

Silencing PRR11 inhibited stem cell-like traits of human ESCC cells in vitro

Meanwhile, we examine the effect of silencing PRR11 on the stem cell-like traits of ESCC cells. Endogenous PRR11 was silenced using shRNA (Figure 3A). As expected, silencing PRR11 decreased the number and size of tumor spheres (Figure 3B). Meanwhile, the proportion of SP+ cells (Figure 3C) and the mRNA expression of pluripotency-associated factors were, respectively, decreased in PRR11-silenced ESCC cells compared with the control cells (Figure 3D). Altogether, these findings further supported the notion that PRR11 regulated stem cell-like traits in ESCC.

Figure 3.

Silencing PRR11 inhibits ESCC stem cell-like traits in vitro.

Notes: (A) Western blotting analysis of PRR11 expression in PRR11-silenced KYSE30 and ECA109 ESCC cells. (B) Representative micrographs of tumor spheres formed by the indicated cells. Histograms show the mean number of tumor spheres formed by the indicated cells. (C) Hoechst 33342 dye exclusion assay showing that the silencing expression of PRR11 decreased the SP+ subpopulation. (D) Real-time PCR of the mRNA expression of the pluripotency-associated factors in indicated cells. Transcript levels were normalized to GAPDH expression. Error bars represent mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. *P<0.05.

Abbreviation: ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

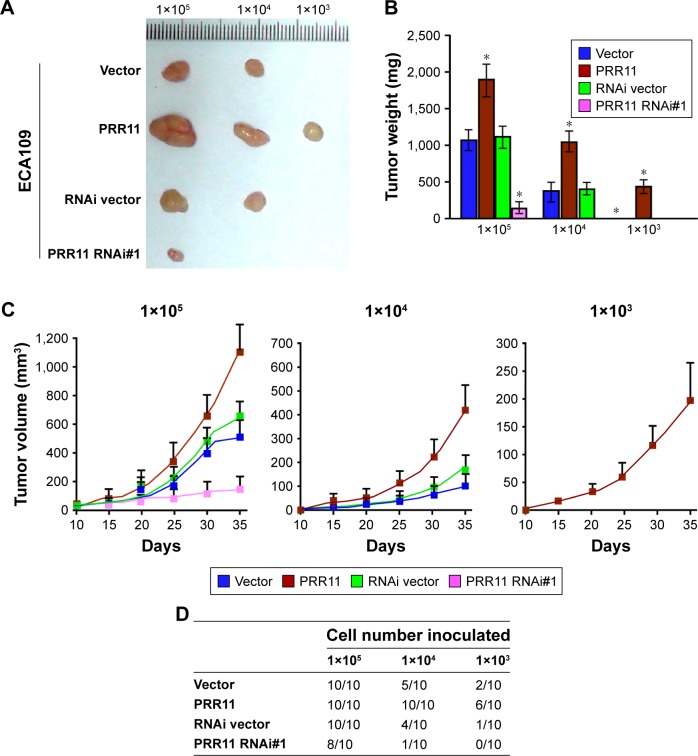

PRR11 enhances tumorigenesis of ESCC cells in vivo

Furthermore, to test whether ESCC inhibits the tumorigenesis of human ESCC in vivo, ECA109 cell was used to stably overexpress PRR11 or PRR11-shRNA. The PRR11-overexpressing, anti-PRR11-expressing, and control cells were inoculated into nude mice. As shown in Figure 4A–C, tumors in the PRR11 overexpression group grew more rapidly than tumors in the control group following implantation of 1×105 or 1×104 cells. Conversely, tumors in the PRR11-shRNA group were smaller than the tumors in the vector group. Importantly, the ability of tumor formation was significantly increased in PRR11 overexpression group cells after 1×103 cells were implanted compared to those of the control group (ECA109-vector:2/10; ECA109-PRR11:6/10; and ECA109-RNAi/vector:1/10) (Figure 4D). These results showed that PRR11 enhances ESCC cell tumorigenesis in vivo.

Figure 4.

PRR11 enhances tumorigenesis and stem cell-like traits of ESCC in vivo.

Notes: (A) Tumors from all the mice in each group. (B) Mean tumor weights. (C) Tumor volumes were measured on the indicated days. (D) A total of 1×105, 1×104, or 1×103 of the indicated cells were implanted into nude mice. Representative images of tumorigenesis in each group are shown. *P<0.05.

Abbreviation: ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

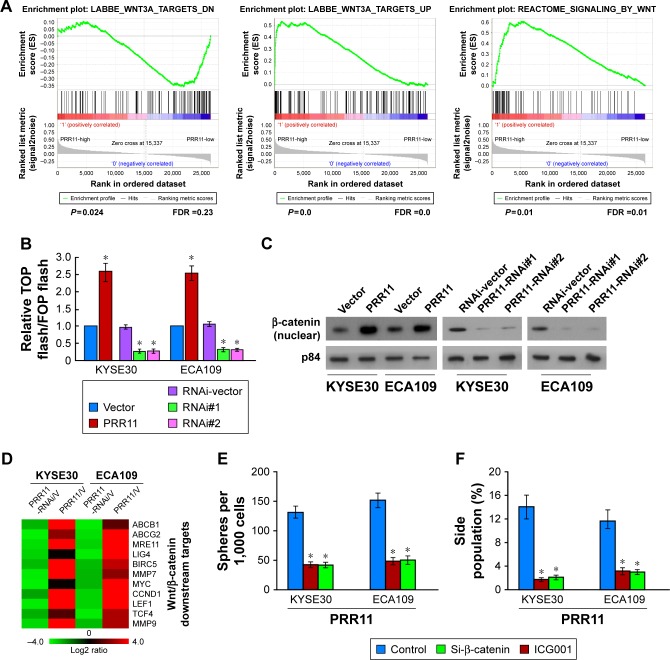

PRR11 upregulation activates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in ESCC

Through analysis of PRR11 mRNA expression levels and Wnt/β-catenin-regulated gene signatures from TCGA dataset, gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis showed that the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway was enriched in TCGA datasets (Figure 5A). As expected, overexpression of PRR11 significantly enhanced, whereas silencing of PRR11 reduced the activity of TOP/FOP flash luciferase reporter (Figure 5B). Furthermore, cellular fractionation showed that PRR11 overexpression enhances nuclear accumulation of β-catenin (Figure 5C), indicating that PRR11 activates the Wnt/β-catenin pathway by promoted β-catenin nuclear accumulation. Moreover, the expression levels of numerous well-characterized Wnt/β-catenin downstream genes were shown to be increased in PRR11 overexpressing cells but were lower in PRR11-silenced cells (Figure 5D). Next, we investigated whether PRR11-mediated ESCC tumorigenesis occurs through Wnt/β-catenin activation. As shown in Figure 5E and F, the stimulatory effect of PRR11 on β-catenin activation was significantly inhibited by transfection of knockdown β-catenin or treatment with β-catenin inhibitor (ICG001). Taken together, these results indicate that activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway exerted functional effects of PRR11 on ESCC tumorigenesis.

Figure 5.

PRR11 upregulation activates the β-catenin signaling pathway in ESCC.

Notes: (A) GSEA plot showing that PRR11 expression positively correlated with β-catenin signaling pathway. (B) Analysis of luciferase reporter activity in the indicated cells. (C) Altered nuclear translocation of β-catenin in response to deregulated PRR11 expression. (D) Real-time PCR analysis demonstrating an apparent overlap between β-catenin-dependent gene expression and PRR11-regulated gene expression. The pseudo color represents an intensity scale for PRR11 versus vector or PRR11 shRNA versus control shRNA, calculated by log2 transformation. (E) Histograms show the mean number of tumor spheres formed by the indicated cells. (F) Hoechst 33342 dye exclusion assay showing the silencing expression of PRR11 decreased the SP+ subpopulation. *P<0.05.

Abbreviations: ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; GSEA, gene set enrichment analysis.

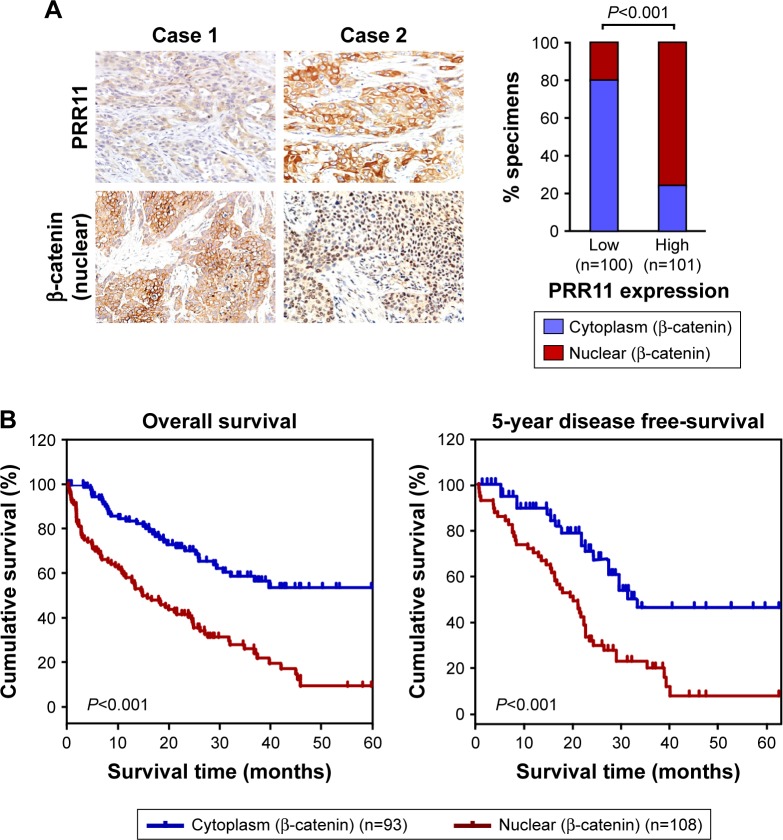

Clinical relevance of PRR11 induced Wnt/β-catenin activation in ESCC

The clinical relevance of PRR11 expression and Wnt/β-catenin activation was further characterized in human ESCC. As shown in Figure 6A (P<0.001), the correlation of PRR11 expression and nuclear β-catenin, as an indicator of Wnt/β-catenin signaling activation, was further confirmed in a cohort of clinical ESCC cancer tissues using IHC analysis. Importantly, statistical analysis showed that patients with ESCC cancer with high β-catenin expression had worse overall and disease-free survival than those with low β-catenin expression (Figure 6B, P<0.01; P<0.01). Collectively, these results further supported the notion that PRR11 overexpression enhanced tumorigenic capability and promoted recurrence of ESCC via upregulation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, consequently resulting in poor survival of ESCC patients.

Figure 6.

Clinical relevance of PRR11 induced Wnt/β-catenin activation in ESCC.

Notes: (A) The nuclear expression levels of p65 were associated with the expression of PRR11 in 201 primary human ESCC specimens. (B) The Kaplan–Meier overall (left) or disease-free (right) survival curves comparing patients with ESCC with low and high β-catenin nuclear expression levels (n=201; P<0.001).

Abbreviation: ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

Discussion

ESCC leads to significant morbidity and mortality in developing countries, especially in China, where approximately 50% of all newly identified ESCC patients in the world are present.31,32 Due to the lack of effective early diagnosis biomarkers, ESCC is the most common cause of cancer-related deaths, and the 5-year survival rate of ESCC is just about 15%.33–35 Therefore, identification and functional analysis of novel potential cancer-associated genes are of great importance for developing diagnostic, preventive, and therapeutic strategies for ESCC treatment and management.

Disease recurrence is a major prognostic factor in ESCC and greatly reduces the effect of ESCC treatment. Our study showed that patients with high PRR11 expression revealed a 17.3% cumulative 5-year survival rate, which was significantly lower than that in patients with low PRR11 expression (64.3%), suggesting the possibility of using PRR11 as a predictor for ESCC patient prognosis and survival. Moreover, the high PRR11 expression group revealed a lower 5-year disease-free survival rate than low PRR11 expression group, which indicates that PRR11 may involve in drug resistance and tumor recurrence. Interesting, PRR13, a member of the PRR11 protein family, has been reported to be resistant to chemotherapy in several cancers, such as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), gastric cancer, and nasopharyngeal carcinoma.36–38 Therefore, it is particularly noteworthy to investigate the relationship between PRR11 and ESCC chemotherapy as well as the mechanism of PRR11-regulated ESCC recurrence.

Recent advances have indicated that CSC-targeting therapeutics may be a potential and effective strategy to improve the prognosis of patients suffering from malignancies. CSC-dependent pathways, such as Wnt/β-catenin signaling, are emerging as attractive targets owing to the fact that their inactivation may allow the elimination of CSCs.39–42 For example, ITCH hyperexpression promotes ubiquitination and degradation of phosphorylated Dvl2, thereby inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in ESCC, which indicates that cir-ITCH may have an inhibitory effect on ESCC by regulating the Wnt pathway.43 Expression of WISP1, a downstream target gene of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, predicted prognosis of ESCC patients treated with radiotherapy, and inhibition of WISP1 may be a potential target to overcome radioresistance in ESCC.44 Therefore, targeting the Wnt/β-catenin pathway may provide an attractive therapeutic approach for achieving better clinical outcomes for cancer patients.

In this study, we showed that both the mRNA and protein levels of PRR11 were markedly higher in ESCC cell lines than in NEECs. Moreover, the overexpression of PRR11 is correlated with the clinical staging, T classification, and N classification of the disease as determined by IHC analysis. These data strongly suggest that PRR11 might be an independent marker in human ESCC progression and pathogenesis. Herein, we reported that the mRNA level of PRR11 was significantly upregulated in ESCC not only by our study but also by analyzing the public dataset. Interestingly, we found that transcription factor TCF4 was predicted to localize in the promoter region of PRR11, by using the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgGateway) and the ECR Browser (http://ecrbrowser.dcode.org/). Thus, it would be of great interest to further investigate whether PRR11 upregulation in ESCC can be attributed to Wnt/b-catenin-mediated transcriptional upregulation.

It has been reported that PRR11 plays an important role in cancer development; however, the molecular mechanism of PRR11 in cancers is still unclear. Interestingly, we found that APC, GSK-3β, and AXIN2, which have been reported to be the negative regulators of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, were the potent PRR11-binding proteins identified by affinity purification/mass spectrometry (IP/MS) (data not shown). We suspect that PRR11 may interact with the destructive complex (APC, GSK-3β, and AXIN2) and release the β-catenin from the destructive complex, subsequently enhancing the level of nuclear β-catenin protein accumulation in ESCC cells. In fact, we found that PRR11 overexpression enhances but PRR11 downregulation decreases nuclear accumulation of β-catenin by using cellular fractionation assay (Figure 5C), which indicates that PRR11 activates the Wnt/β-catenin pathway probably via breaking negative regulation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Therefore, we speculate that PRR11 activated the Wnt/β-catenin pathway by interacting with the destructive complex (APC, GSK-3β, and AXIN2), which is under investigation in our laboratory.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that a new tumor-related gene, PRR11, was overexpressed in ESCC and that upregulation of PRR11 may be useful as a prognostic marker of ESCC progression. Uncovering a biological function and molecular mechanism for PRR11 overexpression in ESCC is needed, and it provides important insights into understanding ESCC progression. Understanding the roles of PRR11 in ESCC progression will not only advance our knowledge of the mechanisms underlying ESCC development and progression but also could establish PRR11 as a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of ESCC.

Supplementary materials

(A) Real-time PCRanalysis of PRR11 expression in ESCCtissues (T) with matched adjacent non-tumor tissues (N) from 8 patients. (B) Real-time PCR analysis of PRR11 expression in 2 NEECs and in ESCC cell lines (HKESC1, TE-1, KYSE520, EC9706, KYSE410, ECA109, KYSE140, KYSE510, EC18, KYSE30, KYSE180, and 108Ca).

Notes: (A) Transcript levels were normalized to GAPDH expression. (B) Transcript levels were normalized to GAPDH expression. Each bar represents mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. *P<0.05.

Abbreviations: ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; NEECs, normal esophageal epithelial cells.

Table S1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of studied patients and expression of PRR11 in ESCC

| Factor | No | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 155 | 73.6 |

| Female | 46 | 26.4 |

| Age (years) | ||

| ≤57 | 99 | 49.3 |

| >57 | 102 | 50.7 |

| Clinical stage | ||

| I | 24 | 11.9 |

| II | 92 | 45.8 |

| III | 66 | 32.8 |

| IV | 19 | 9.5 |

| T classification | ||

| T1 | 21 | 10.4 |

| T2 | 69 | 34.3 |

| T3 | 99 | 49.3 |

| T4 | 12 | 6.0 |

| N classification | ||

| N0 | 109 | 54.2 |

| N1 | 92 | 45.8 |

| M classification | ||

| No | 180 | 89.6 |

| Yes | 21 | 10.4 |

| Histological differentiation | ||

| Well | 56 | 27.9 |

| Moderate | 82 | 40.8 |

| Poor | 63 | 31.3 |

| Vital status | ||

| Alive | 80 | 39.8 |

| Dead | 121 | 60.1 |

| Expression of PRR11 | ||

| Low expression | 62 | 30.8 |

| High expression | 139 | 69.2 |

Abbreviation: ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

Table S2.

Correlation between the clinicopathological features and expression of PRR11

| Patients’ characteristics | PRR11 expression | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low or none | High | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 63 | 89 | <0.001 |

| Female | 37 | 12 | |

| Age (years) | |||

| ≤57 | 51 | 49 | 0.752 |

| >57 | 49 | 52 | |

| Clinical stage | |||

| I | 17 132 62 |

7 44 |

0.037 |

| II | 49 | 43 | |

| III | 25 | 41 | |

| IV | 9 | 10 | |

| T classification | |||

| T1 | 15 132 62 |

6 44 |

<0.001 |

| T2 | 49 | 20 | |

| T3 | 31 | 68 | |

| T4 | 5 | 7 | |

| N classification | |||

| N0 | 68 204 |

41 0 |

<0.001 |

| N1 | 32 | 60 | |

| M classification | |||

| No | 95 | 86 | 0.02 |

| Yes | 5 | 16 | |

| Histological differentiation | |||

| Well | 26 174 |

30 | 0.809 |

| Moderate | 41 | 41 | |

| Poor | 33 | 30 | |

| Vital status | |||

| Alive | 59 | 21 | <0.001 |

| Dead | 41 | 80 | |

Table S3.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of different prognostic parameters in patients with ESCC by Cox-regression analysis

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR–RR (95% CI) | |

| Clinical stage | ||||

| I | <0.001 | 1.913 (1.478–2.476) | =0.02 | 1.677 (1.286–2.188) |

| II | ||||

| III | ||||

| IV | ||||

| T classification | ||||

| T1 | <0.001 | 4.929 (3.576–6.793) | <0.001 | 5.277 (3.771–7.385) |

| T2 | ||||

| T3 | ||||

| T4 | ||||

| N classification | ||||

| N0 | <0.001 | 4.871 (3.203–7.409) | 0.02 | 1.514 (1.314–1.841) |

| N1 | ||||

| PRR11 expression | ||||

| Low expression | <0.001 | 38.077 (7.254–199.867) | 0.003 | 1.879 (1.178–2.998) |

| High expression | ||||

Abbreviation: ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by Guangdong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. 2018A0303130323).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(14):2137–2150. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, et al. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esophageal cancer: epidemiology, pathogenesis and prevention. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;5(9):517–526. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koshy M, Esiashvilli N, Landry JC, et al. Multiple management modalities in esophageal cancer: combined modality management approaches. Oncologist. 2004;9(2):147–159. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-2-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Younes M, Henson DE, Ertan A, et al. Incidence and survival trends of esophageal carcinoma in the United States: racial and gender differences by histological type. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37(12):1359–1365. doi: 10.1080/003655202762671215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enzinger PC, Mayer RJ. Esophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(23):2241–2252. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashida A, Boku N, Aoyagi K, et al. Expression profiling of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients treated with definitive chemoradiotherapy: clinical implications. Int J Oncol. 2006;28(6):1345–1352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin DC, Du XL, Wang MR. Protein alterations in ESCC and clinical implications: a review. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22(1):9–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2008.00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yie SM, Yang H, Ye SR, et al. Expression of HLA-G is associated with prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128(6):1002–1009. doi: 10.1309/JNCW1QLDFB6AM9WE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng J, Jin H, Hou X, et al. Disturbed tryptophan metabolism correlating to progression and metastasis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;486(3):781–787. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.03.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng J, Zheng G, Jin H, et al. Towards tyrosine metabolism in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2017;20(2):133–139. doi: 10.2174/1386207319666161220115409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sera T. Zinc-finger-based artificial transcription factors and their applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61(7–8):513–526. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Negi S, Imanishi M, Matsumoto M, et al. New redesigned zinc-finger proteins: design strategy and its application. Chemistry. 2008;14(11):3236–3249. doi: 10.1002/chem.200701320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ball LJ, Kuhne R, Schneider-Mergener J, et al. Recognition of proline-rich motifs by protein-protein-interaction domains. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2005;44(19):2852–2869. doi: 10.1002/anie.200400618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kay BK, Williamson MP, Sudol M. The importance of being proline: the interaction of proline-rich motifs in signaling proteins with their cognate domains. FASEB J. 2000;14(2):231–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barron DA, Kagey JD. The role of the Hippo pathway in human disease and tumorigenesis. Clin Transl Med. 2014;3:25. doi: 10.1186/2001-1326-3-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altomare DA, Testa JR. Perturbations of the AKT signaling pathway in human cancer. Oncogene. 2005;24(50):7455–7464. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ji Y, Xie M, Lan H, et al. PRR11 is a novel gene implicated in cell cycle progression and lung cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45(3):645–656. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang C, Zhang Y, Li Y, et al. PRR11 regulates late-S to G2/M phase progression and induces Premature Chromatin Condensation (PCC) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;458(3):501–508. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.01.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larance M, Ahmad Y, Kirkwood KJ, et al. Global subcellular characterization of protein degradation using quantitative proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12(3):638–650. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.024547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao H, Teng C, Huang W, et al. SOX2 promotes the epithelial to mesenchymal transition of esophageal squamous cells by modulating slug expression through the activation of STAT3/HIF-alpha signaling. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(9):21643–21657. doi: 10.3390/ijms160921643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Islam F, Gopalan V, Wahab R, et al. Cancer stem cells in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma: identification, prognostic and treatment perspectives. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2015;96(1):9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Long A, Giroux V, Whelan KA, et al. WNT10A promotes an invasive and self-renewing phenotype in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2015;36(5):598–606. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgv025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang XX, Liu R, Jin SQ, et al. Overexpression of Aurora-A kinase promotes tumor cell proliferation and inhibits apoptosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cell line. Cell Res. 2006;16(4):356–366. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang KH, Dai YD, Tong M, et al. A CD90(+) tumor-initiating cell population with an aggressive signature and metastatic capacity in esophageal cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73(7):2322–2332. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y, Zhang C, Zhu H, et al. CD90 positive cells exhibit aggressive radioresistance in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9(3):610–620. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.03.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andl CD, Mizushima T, Nakagawa H, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor mediates increased cell proliferation, migration, and aggregation in esophageal keratinocytes in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(3):1824–1830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209148200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimada Y, Imamura M, Wagata T, et al. Characterization of 21 newly established esophageal cancer cell lines. Cancer. 1992;69(2):277–284. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920115)69:2<277::aid-cncr2820690202>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li J, Zhang N, Song LB, et al. Astrocyte elevated gene-1 is a novel prognostic marker for breast cancer progression and overall patient survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(11):3319–3326. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xing D, Tan W, Lin D. Genetic polymorphisms and susceptibility to esophageal cancer among Chinese population (review) Oncol Rep. 2003;10(5):1615–1623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55(2):74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parkin DM, Pisani P, Ferlay J. Estimates of the worldwide incidence of eighteen major cancers in 1985. Int J Cancer. 1993;54(4):594–606. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910540413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu SM, Su M, Tian DP, et al. Characterization of one newly established esophageal cancer cell line CSEC from a high-incidence area in China. Dis Esophagus. 2008;21(4):309–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.An JY, Fan ZM, Zhuang ZH, et al. Proteomic analysis of blood level of proteins before and after operation in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma at high-incidence area in Henan Province. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10(22):3365–3368. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i22.3365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bi W, Wang Y, Sun G, et al. Paclitaxel-resistant HeLa cells have up-regulated levels of reactive oxygen species and increased expression of taxol resistance gene 1. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2014;27(4):871–878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bi J, Bai Z, Ma X, et al. Txr1: an important factor in oxaliplatin resistance in gastric cancer. Med Oncol. 2014;31(2):807. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0374-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peng X, Li W, Tan G. Reversal of taxol resistance by cisplatin in nasopharyngeal carcinoma by upregulating thromspondin-1 expression. Anticancer Drugs. 2010;21(4):381–388. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e3283363980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yeung J, Esposito MT, Gandillet A, et al. Beta-Catenin mediates the establishment and drug resistance of MLL leukemic stem cells. Cancer Cell. 2010;18(6):606–618. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang N, Wei P, Gong A, et al. FoxM1 promotes beta-catenin nuclear localization and controls Wnt target-gene expression and glioma tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(4):427–442. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vermeulen L, De Sousa EMF, van der Heijden M, et al. Wnt activity defines colon cancer stem cells and is regulated by the microenvironment. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(5):468–476. doi: 10.1038/ncb2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malanchi I, Peinado H, Kassen D, et al. Cutaneous cancer stem cell maintenance is dependent on beta-catenin signalling. Nature. 2008;452(7187):650–653. doi: 10.1038/nature06835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li F, Zhang L, Li W, et al. Circular RNA ITCH has inhibitory effect on ESCC by suppressing the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Oncotarget. 2015;6(8):6001–6013. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang H, Luo H, Hu Z, et al. Targeting WISP1 to sensitize esophageal squamous cell carcinoma to irradiation. Oncotarget. 2015;6(8):6218–6234. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(A) Real-time PCRanalysis of PRR11 expression in ESCCtissues (T) with matched adjacent non-tumor tissues (N) from 8 patients. (B) Real-time PCR analysis of PRR11 expression in 2 NEECs and in ESCC cell lines (HKESC1, TE-1, KYSE520, EC9706, KYSE410, ECA109, KYSE140, KYSE510, EC18, KYSE30, KYSE180, and 108Ca).

Notes: (A) Transcript levels were normalized to GAPDH expression. (B) Transcript levels were normalized to GAPDH expression. Each bar represents mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. *P<0.05.

Abbreviations: ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; NEECs, normal esophageal epithelial cells.

Table S1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of studied patients and expression of PRR11 in ESCC

| Factor | No | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 155 | 73.6 |

| Female | 46 | 26.4 |

| Age (years) | ||

| ≤57 | 99 | 49.3 |

| >57 | 102 | 50.7 |

| Clinical stage | ||

| I | 24 | 11.9 |

| II | 92 | 45.8 |

| III | 66 | 32.8 |

| IV | 19 | 9.5 |

| T classification | ||

| T1 | 21 | 10.4 |

| T2 | 69 | 34.3 |

| T3 | 99 | 49.3 |

| T4 | 12 | 6.0 |

| N classification | ||

| N0 | 109 | 54.2 |

| N1 | 92 | 45.8 |

| M classification | ||

| No | 180 | 89.6 |

| Yes | 21 | 10.4 |

| Histological differentiation | ||

| Well | 56 | 27.9 |

| Moderate | 82 | 40.8 |

| Poor | 63 | 31.3 |

| Vital status | ||

| Alive | 80 | 39.8 |

| Dead | 121 | 60.1 |

| Expression of PRR11 | ||

| Low expression | 62 | 30.8 |

| High expression | 139 | 69.2 |

Abbreviation: ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

Table S2.

Correlation between the clinicopathological features and expression of PRR11

| Patients’ characteristics | PRR11 expression | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low or none | High | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 63 | 89 | <0.001 |

| Female | 37 | 12 | |

| Age (years) | |||

| ≤57 | 51 | 49 | 0.752 |

| >57 | 49 | 52 | |

| Clinical stage | |||

| I | 17 132 62 |

7 44 |

0.037 |

| II | 49 | 43 | |

| III | 25 | 41 | |

| IV | 9 | 10 | |

| T classification | |||

| T1 | 15 132 62 |

6 44 |

<0.001 |

| T2 | 49 | 20 | |

| T3 | 31 | 68 | |

| T4 | 5 | 7 | |

| N classification | |||

| N0 | 68 204 |

41 0 |

<0.001 |

| N1 | 32 | 60 | |

| M classification | |||

| No | 95 | 86 | 0.02 |

| Yes | 5 | 16 | |

| Histological differentiation | |||

| Well | 26 174 |

30 | 0.809 |

| Moderate | 41 | 41 | |

| Poor | 33 | 30 | |

| Vital status | |||

| Alive | 59 | 21 | <0.001 |

| Dead | 41 | 80 | |

Table S3.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of different prognostic parameters in patients with ESCC by Cox-regression analysis

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR–RR (95% CI) | |

| Clinical stage | ||||

| I | <0.001 | 1.913 (1.478–2.476) | =0.02 | 1.677 (1.286–2.188) |

| II | ||||

| III | ||||

| IV | ||||

| T classification | ||||

| T1 | <0.001 | 4.929 (3.576–6.793) | <0.001 | 5.277 (3.771–7.385) |

| T2 | ||||

| T3 | ||||

| T4 | ||||

| N classification | ||||

| N0 | <0.001 | 4.871 (3.203–7.409) | 0.02 | 1.514 (1.314–1.841) |

| N1 | ||||

| PRR11 expression | ||||

| Low expression | <0.001 | 38.077 (7.254–199.867) | 0.003 | 1.879 (1.178–2.998) |

| High expression | ||||

Abbreviation: ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.