Abstract

A Mg2+-water bridge between the C-3, C-4 diketo moiety of fluoroquinolones and the conserved amino acid residues in the GyrA/ParC subunit is critical for the binding of a fluoroquinolone to a topoisomerase-DNA covalent complex. The fluoroquinolone UING-5-249 (249) can bind to the GyrB subunit through its C7-aminomethylpyrrolidine group. This interaction is responsible for enhanced activities of 249 against the wild type and quinolone-resistant mutant topoisomerases. To further evaluate the effects of the 249-GyrB interaction on fluoroquinolone activity, we examined the activities of decarboxy- and thio-249 against DNA gyrase and conducted docking studies using the structure of a gyrase-ciprofloxacin-DNA ternary complex. We found that the 249-GyrB interaction rescued the activity of thio-249 but not that of decarboxy-249. A C7-group that binds more strongly to the GyrB subunit may allow for modifications at the C-4 position, leading to a novel compound that is active against the wild type and quinolone-resistant pathogens.

Keywords: DNA gyrase, drug design, fluoroquinolone, quinolone resistance, topoisomerase

1. Introduction

Type IIA topoisomerases play critical roles in various biological processes by controlling the topology of DNA (1-4). As part of the catalytic cycle, these enzymes cleave both strands of a duplex DNA and generate a double-strand break (DSB), which is potentially harmful to the genome. They form covalent links between the active-site tyrosine residues and 5’-phosphates at the sites of strand breakage until both DNA strands are re-sealed. Thus, the catalytic intermediate contains a DSB but the two DNA ends are held together by the topoisomerase (1-4). Several type IIA topoisomerase inhibitors, including fluoroquinolones, utilize the harmfulness of a DSB in their mode of action (3-7). These inhibitors bind and stabilize the catalytic intermediates that contain a DSB by forming topoisomerase-drug-DNA ternary complexes. Ternary complex formation leads to the inhibition of DNA replication, the generation of DSBs, and subsequent cell death. This unique mode of action is often referred to as ‘topoisomerase poisoning’ (3-7).

Fluoroquinolones are clinically important broad-spectrum antibacterial agents that poison bacterial type IIA topoisomerases, DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV (3-7). DNA gyrase, upon its discovery, was identified as the cellular target of quinolones (8,9). Kreuzer and Cozzarelli have shown that nalidixic acid blocks DNA replication in Escherichia coli by trapping gyrase in a gyrase-drug-DNA ternary complex, which arrests replication fork progression, rather than inhibiting the catalytic activity of gyrase. Thus, quinolones convert gyrase to a ‘poison’ of DNA replication (10). The molecular basis of topoisomerase poisoning was revealed when the structures of topoisomerase-fluoroquinolone-DNA complexes became available (11,12). Structural studies have shown that two fluoroquinolone molecules are intercalated between the +1 and −1 bases at the sites of strand breakage and anchored by a Mg2+-water bridge between the C-3, C-4 diketo moiety of fluoroquinolones and the conserved serine and glutamate/aspartate residues in the GyrA/ParC subunit (correspond to Ser-83 and Asp-87 of E. coli GyrA, respectively). No other direct interaction is observed between fluoroquinolones and topoisomerases (11-13). Thus, these are the only two amino acid residues that interact with the topoisomerase. This explains why these positions are hotspots for quinolone resistant mutations (5,7,12).

Unlike other fluoroquinolones, UING-5-249 (249) directly binds to the conserved glutamic acid residue in the Toprim domain of the GyrB subunit through the C7-aminomethylpyrrolidine (AMP) group (14). The enhanced activities of 249 against the wild type and quinolone-resistant mutant topoisomerases (15,16) are attributed to the 249-GyrB interaction (14). We synthesized analogs of 249 and ciprofloxacin (CFX) to examine if the 249-GyrB interaction modulates the effect of either the removal of the C3-carboxylic acid or the substitution of the C-4 carbonyl with an oxygen. We assessed their activities against E. coli gyrase and conducted docking studies using the structure of a Staphylococcus aureus gyrase-CFX-DNA ternary complex.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fluoroquinolones

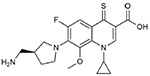

CFX was obtained from Bayer Healthcare (Westhaven, CT, USA). Synthesis of 249 (15) and decarboxy-CFX (17) was described previously. Synthesis of decarboxy-249, thio-249, and thio-CFX is described in the Supplemental Materials. Structures of the fluoroquinolones and their analogs used in this study are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Activities of 249 and CFX, as well as their analogs, against E. coli DNA gyrase

| Compound | Structure | IC50 (μM)1 | CC3 (μM)2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 249 |  |

0.18 ± 0.003 | 0.009 ± 0.001 |

| decarboxy-249 |  |

57.0 ± 5.4 | 7.6 ± 0.75 |

| thio-249 |  |

19.0 ± 2.4 | 2.2 ± 0.05 |

| CFX |  |

0.44 ± 0.008 | 0.068 ± 0.006 |

| decarboxy-CFX |  |

62.1 ± 7.2 | 22.7 ± 6.9 |

| thio-CFX |  |

255.3 ± 2.7 | 100.9 ± 2.7 |

The IC50 values (the 50% inhibitory concentration) against gyrase were determined in the supercoiling assay (15).

The CC3 values (the concentration required to triple the level of cleavage from the background level in the absence of drug) against DNA gyrase were determined in the DNA cleavage assay (15).

2.2. Biochemical Assays

The supercoiling and DNA cleavage assays were performed as described previously (16). Assay conditions are described in detail in the Supplemental Materials.

2.3. Docking experiments

Fluoroquinolones were docked into the structure of a S. aureus gyrase-CFX-DNA ternary complex (PDB ID: 2XCT) using the Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) 2016.08 software package [Chemical Computing Group (Montreal, Canada)]. The 3D structure obtained from PDB (PDB ID: 2XCT) was prepared for docking by sequentially adding hydrogens, adjusting the 3D protonation state and performing energy minimization using Amber10 force-field. The ligand structures to be docked were prepared by adjusting partial charges followed by energy minimization using Amber10 force-field. The site for docking was defined by selecting the co-crystallized ligand (CFX). Docking parameters were set as Placement: Triangle matcher; Scoring function: London dG; Retain Poses: 30; Refinement: Rigid Receptor; Re-scoring function: GBVI/WSA dG; Retain poses: 10. Reliability of the docking algorithm was assessed by determining the root mean square deviation (RMSD) between the co-crystallized and the redocked ligand confirmation. RMSD value for the top generated pose was < 2.0 Å, which is considered accurate in predicting a ligand’s binding orientation. Binding poses for the compounds were predicted using the above validated docking algorithm.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Decarboxylation significantly affects the activities of fluoroquinolones

As reported previously (14-16), 249 was more active than CFX against E. coli gyrase (Table 1). We conducted docking studies using a ternary complex formed with DNA gyrase (PDB ID: 2XCT). A recent study has shown that this ternary complex is suitable for docking studies of fluoroquinolones (18). Docking of CFX into a gyrase-CFX-DNA ternary complex generated several poses that exhibited excellent overlap with the reference ligand with the top ranked pose having an RMSD of 1.5512 Å with the co-crystallized ligand, validating the docking protocol used in this study. Docking of 249 at the site of gyrase-CFX-DNA ternary complex generated poses having similar orientation to that of co-crystallized reference ligand. As expected, the C3-carboxylic acid and the C4-carbonyl group of both 249 (Fig. 1A) and CFX (Fig. 1D) chelated a Mg2+ ion that would in turn form a Mg2+-water bridge with the GyrA subunit. In addition, the primary amine on the C7-AMP group of 249 interacted with Glu-477 of GyrB (Fig. 1A). This interaction is responsible for the enhanced activity of 249. Similar interactions were not formed by the secondary amine on the C7-piperazine group of CFX (Fig. 1D). Introduction of a C7-group that can bind more strongly to the conserved amino acid residue(s) in the Toprim domain of GyrB/ParE may create a novel fluoroquinolone with higher potency. Such fluoroquinolones may be active against quinolone-resistant topoisomerases.

Figure 1. Binding of decarboxy- and thio-fluoroquinolones to a gyrase-DNA complex.

Shown here is 2-D representation of the coordination sphere around docked 249 (A), decarboxy-249 (B), thio-249 (C), CFX (D), decarboxy-CFX (E), and thio-CFX (F) in the complex with S. aureus DNA gyrase and DNA (PDB ID: 2XCT). The compounds stacked between two bases, with the π-π stacking interactions depicted by bicyclic group with green dotted lines, the green dotted arrows represent sidechain donor interactions and the red lines represent Mg2+ contact.

Docking of decarboxy-fluoroquinolones showed that the C4-carbonyl group alone could interact with a Mg2+ ion (Figs. 1B and 1E). However, the removal of the C3-carboxylic acid significantly affected the activity of fluoroquinolones against gyrase (Table 1). Interestingly, docking experiments showed that the primary amine on the C7-AMP group of decarboxy-249 lost its interaction with Glu-477 of GyrB (Fig. 1B), while the secondary amine on the C7-piperazine group of decarboxy-CFX was placed in an orientation favorable for interacting with Arg-458 of GyrB (Fig. 1E). It is likely that interactions between the C3-carboxylic acid and both the Mg2+ ion and the conserved serine residue are required to form a stable Mg2+-water bridge and stabilize the binding of a fluoroquinolone to a topoisomerase-DNA complex (12,13). The stability of ternary complexes correlates with the potency of fluoroquinolones (13,19).

3.2. Activities of thio-fluoroquinolones are modulated by the C-7 group

To further probe the importance of the C-4 carbonyl, we substituted the C-4 oxygen with a sulfur. Since sulfur is less electronegative than oxygen, we had expected that the Mg2+-water bridge formed with thio-fluoroquinolones would be less stable than that formed with fluoroquinolones. Thus, thio-fluoroquinolones would be less active than their parent fluoroquinolones, which turned out to be the case (Table 1). Thio-249 was only about 10-fold less active than 249 and 3-fold more active than decarboxy-249 in inhibiting the supercoiling activity of gyrase. In contrast, thio-CFX was more than 500-fold less active than CFX and 4-fold less active than decarboxy-CFX. Docking studies of these thio-fluoroquinolones revealed their distinct characteristics that may explain their activities. Thio-249 overlapped relatively well with the co-crystallized reference ligand (Figs. S1A and S1B) and interacted with gyrase in the same manner as 249: binding through a Mg2+-water bridge between C-3 and C-4 groups and the GyrA subunit, and the interaction between the C7-AMP group and Glu-477 of GyrB (Fig. 1C). In contrast, thio-CFX did not generate any pose with orientation similar to that of the co-crystallized reference ligand (Figs. S1C and S1D). The inability of thio-CFX to bind to a gyrase-DNA complex in the appropriate orientation (Fig. 1F) resulted in its extremely low activity (Table 1). In any case, the C7-group, perhaps via its ability to bind to the GyrB subunit, modulated the effect of an alteration at the C-4 position, suggesting the importance of other sidechains when altering one sidechain of a fluoroquinolone.

4. Conclusion

We demonstrated the importance of both the C3-carboxylic acid and the C4-carbonyl group for the activity of fluoroquinolones. The unique ability of 249 to bind to the GyrB subunit through its C7-AMP lessened not only the effects of quinolone-resistant mutations at the conserved serine and glutamate/aspartate residues in the GyrA/ParC subunit (14-16) but also the effect of a modification at the C-4 position (Table 1). Thus, the introduction of a C7-group that can bind more strongly to the GyrB subunit may allow modifications at the C-3 and C-4 positions, even beyond the quinolone core structure, leading to novel compounds that are active against both the wild type and quinolone-resistant pathogens. On the other hand, maintaining the interaction with both the GyrA and GyrB subunits may create novel fluoroquinolones with extremely high potency. In both cases, the optimal stacking interaction between the quinolone core and the bases may be critical for the stability of ternary complexes and the potency of the drugs.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Binding of fluoroquinolone 249 to the GyrB subunit enhanced its activity

Decarboxylation abolished the activity of both 249 and ciprofloxacin

The 249-GyrB interaction lessened the effect of a modification at the C-4 position

A C7-group that binds to the GyrB subunit creates compounds with higher potency

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant R01 AI087671 (to RJK). PRC acknowledges support of the NIH Predoctoral Training Program in Biotechnology (GM008365) and the University of Iowa Center for Biocatalysis and Bioprocessing fellowship. TRT acknowledges support of the NIH Predoctoral Training Program in Pharmacological Sciences (GM067795), the American Foundation for Pharmaceutical Education Predoctoral Fellowship Program, and the American Chemical Society Division of Medicinal Chemistry Fellowship sponsored by Richard B. Silverman.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Nitiss JL, DNA topoisomerase II and its growing repertoire of biological functions. Nat Rev Cancer 2009;9:327–37. 10.1038/nrc2608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vos SM, Tretter EM, Schmidt BH, Berger JM, All tangled up: how cells direct, manage and exploit topoisomerase function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2011;12:827–41. 10.1038/nrm3228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen SH, Chan NL, Hsieh TS, New mechanistic and functional insights into DNA topoisomerases. Annu Rev Biochem 2013;82:139–70. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061809-100002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hiasa H, DNA topoisomerases as targets for antibacterial agents. Methods Mol Biol 2018; 1703:47–62. 10.1007/978-1-4939-7_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collin F, Karkare S, Maxwell A, Exploiting bacterial DNA gyrase as a drug target: current state and perspectives. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2011;92:479–97. 10.1007/s00253-011-3557-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pommier Y, Drugging topoisomerases: lessons and challenges. ACS Chem Biol 2013;8:82–95. 10.1021/cb300648v [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aldred KJ, Kerns RJ, Osheroff N, Mechanism of quinolone action and resistance. Biochemistry 2014;53:1565–74. 10.1021/bi5000564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugino A, Peebles CL, Kreuzer KN. Cozzarelli NR, Mechanism of action of nalidixic acid: purification of Escherichia coli nalA gene product and its relationship to DNA gyrase and a novel nicking-closing enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1977;74:4767–71. 10.1073/pnas.74.11.4767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gellert M, Mizuuchi K, O'Dea MH, Itoh T, Tomizawa J, Nalidixic acid resistance: a second genetic character involved in DNA gyrase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1977;74:4772–6. 10.1073/pnas.74.11.4772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreuzer KN, Cozzarelli NR, Escherichia coli mutants thermosensitive for deoxyribonucleic acid gyrase subunit A: effects on deoxyribonucleic acid replication, transcription, and bacteriophage growth. J Bacteriol 1979;140:424–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laponogov I, Sohi MK, Veselkov DA, Pan XS, Sawhney R, Thompson AW, McAuley KE, Fisher LM, Sanderson MR, Structural insight into the quinolone-DNA cleavage complex of type IIA topoisomerases. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2009;16:667–9. 10.1038/nsmb.1604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wohlkonig A, Chan PF, Fosberry AP, Homes P, Huang J, Kranz M, Leydon VR, Miles TJ, Pearson ND, Perera RL, Shillings AJ, Gwynn MN, Bax BD, Structural basis of quinolone inhibition of type IIA topoisomerases and target-mediated resistance. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2010;17:1152–3. 10.1038/nsmb.1892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blower TR, Williamson BH, Kerns RJ, Berger JM, Crystal structure and stability of gyrase-fluoroquinolone cleaved complexes from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016;113:1706–13. 10.1073/pnas.1525047113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drlica K, Mustaev A, Towle TR, Luan G, Kerns RJ, Berger JM, Bypassing fluoroquinolone resistance with quinazolinediones: studies of drug-gyrase-DNA complexes having implications for drug design. ACS Chem Biol 2014;9:2895–904. 10.1021/cb500629k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.German N, Malik M, Rosen JD, Drlica K, Kerns RJ, Use of gyrase resistance mutants to guide selection of 8-methoxy-quinazoline-2,4-diones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008;52:3915–21. 10.1128/AAC.00330-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oppegard LM, Streck KR, Rosen JD, Schwanz HA, Drlica K, Kerns RJ, Hiasa H, Comparison of in vitro activities of fluoroquinolone-like 2,4- and 1,3-diones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010;54:3011–4. 10.1128/AAC.00190-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marks KR, Malik M, Mustaev A, Hiasa H, Drlica K, Kerns RJ, Synthesis and evaluation of 1-cyclopropyl-2-thioalkyl-8-methoxy fluoroquinolones. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2011;21:4585–8. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.05.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sood D, Kumar N, Singh A, Sakharkar MK, Tomar V, Chandra R, Antibacterial and Pharmacological Evaluation of Fluoroquinolones: A Chemoinformatics Approach. Genomics Inform 2018;16:44–51. 10.5808/GI.2018.16.3.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfeiffer ES, Hiasa H, Replacement of ParC alpha4 helix with that of GyrA increases the stability and cytotoxicity of topoisomerase IV-quinolone-DNA ternary complexes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2004;48:608–11. 10.1128/AAC.48.2.608-611.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.