Abstract

Surface capture assays can measure fluorescently labeled analytes across a 1,000-fold concentration range and at the sub-nanomolar level, but many biological molecules exhibit 1,000,000-fold variations in abundance down to the femtomolar level. The goal of this work is to expand the dynamic range of fluorescence assays by using imaging to combine molecular counting with single-molecule calibration of ensemble intensities. We evaluate optical limits imposed by surface-captured fluorescent labels, compare performances of different fluorophore classes, and use detector acquisition parameters to span wide ranges of fluorescence irradiance. We find that the fluorescent protein phycoerythrin provides uniquely suitable properties with exceptionally intense and homogeneous single-fluorophore brightness that can overcome arbitrary spot detection threshold biases. Major limitations imposed by nonspecifically bound fluorophores were then overcome using rolling circle amplification to densely label cancer-associated miRNA biomarkers, allowing accurate single-molecule detection and calibration across nearly 5 orders of magnitude of concentration with a detection limit of 29 fM. These imaging and molecular counting strategies can be widely applied to expand the limit of detection and dynamic range of a variety of surface fluorescence assays.

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION

Fluorescence is one of the most widely applied measurement modalities for quantification of proteins and nucleic acids, used extensively both in vitro and in situ in cells and tissues.1,2 When fluorescence measurements are based on net intensity, analytes can be measured across a ∼1,000-fold dynamic range with limits of detection typically in the nanomolar range.3–6 However, many proteins, nucleic acids, and other species are present in biological fluids and tissues across 1,000,000-fold concentration ranges, often down to the femtomolar level (a few hundred to thousands of copies per microliter) and are thus undetectable with current assays. These molecules may have clinical relevance for patient care, particularly in the case of genetic fragments shed from cancer cells that are present in body fluids in low abundance, below the limits of detection of current technologies.7–10 These cell-free circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and microvesicular microRNA (miRNA) are challenging to purify and analyze for clinical applications. Although measurement windows can be drastically improved through molecular amplification techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), these methods eliminate the direct relationship between absolute molecular counts and assay signal.11

In recent years, single-molecule optical imaging has revolutionized molecular measurements by pushing the limits of detection to the fundamental limit of digital analyte counting.12–14 By leveraging advances in optics, detectors, and fluorophores, optical signal amplification can eliminate the need for enzymatic amplification.15,16 As a result, these techniques enable the quantification of exact numbers of fluorophores using methods compatible with traditional multiplexing based on color codes or microarrays. Methodologies have rapidly advanced, and ultrasensitive technologies have now reached commercial success for single-molecule analysis of nucleic acids (NanoString nCounter and Pacific Biosciences SMRT Sequencing) and proteins (Singulex, Inc. SMC Immunoassays and Quanterix Corp. Simoa Micro-arrays).17–19 Despite these advancements, numerous challenges still limit robust digital counting and application breadth, particularly when molecular counts are hindered by optical diffraction limits and insufficient intensity and when nonspecific label binding is significant.14

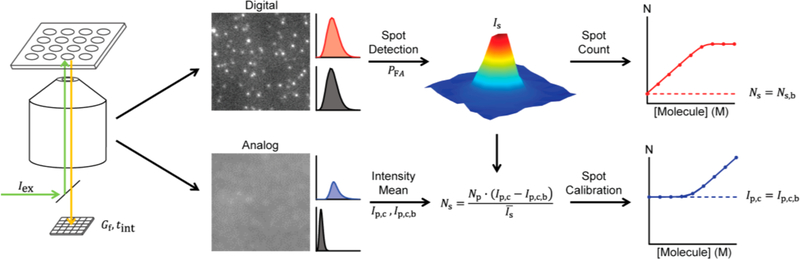

In this article, we investigate the intersection between conventional analog intensity measurements and digital molecular counting through imaging in surface-based fluorescence assays. We demonstrate that under certain conditions, counting and intensity calibration can be combined to yield a 1,000,000-fold dynamic range of molecular quantification down to the femtomolar level. Scheme 1 shows the workflow. Fluorescently labeled molecules captured on a surface are first imaged under precisely controlled acquisition conditions to optimize the unsaturated dynamic range of detection through the excitation intensity (Iex), detector gain (G), and integration time (tint). Low-intensity fluorescence images are analyzed digitally using a spot detection algorithm that identifies single molecules based on spot detection thresholds specified by the probability of false alarm (PFA) within a field of view (FOV). Spot analysis then provides the average single-molecule intensity and absolute spot counts (Ns) per FOV. For high-density coverage for which spots spatially overlap, analog intensity values of the image are used together with calibrated image acquisition condition parameters to convert the measured analog intensity per pixel, Ip,c, to calibrated spot counts, Ns, which allows extension of the assay across the detection limit imposed by the analog background intensity Ip,c,b. In this work, we compare avidin conjugates of organic dyes, quantum dots, fluorescent proteins, and fluorescent microbeads in terms of detection thresholds, spot intensity distributions, stability, dynamic detection range, and non-specific binding. We further measure the impact of detector gain and integration time. Finally, we study the degree of labeling amplification needed to overcome background signals derived from nonspecific probe adhesion in order to count cancer-associated miRNA using this methodology. These outcomes are particularly important for assays for biomarkers such as ctDNA and miRNA, which exhibit >1,000 variations in concentration, and when drastically dissimilar intensities are measured on adjacent elements of microarrays.20,21

Scheme 1.

Imaging and Analysis Workflow

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Spectral Characterization of Fluorescent Labels.

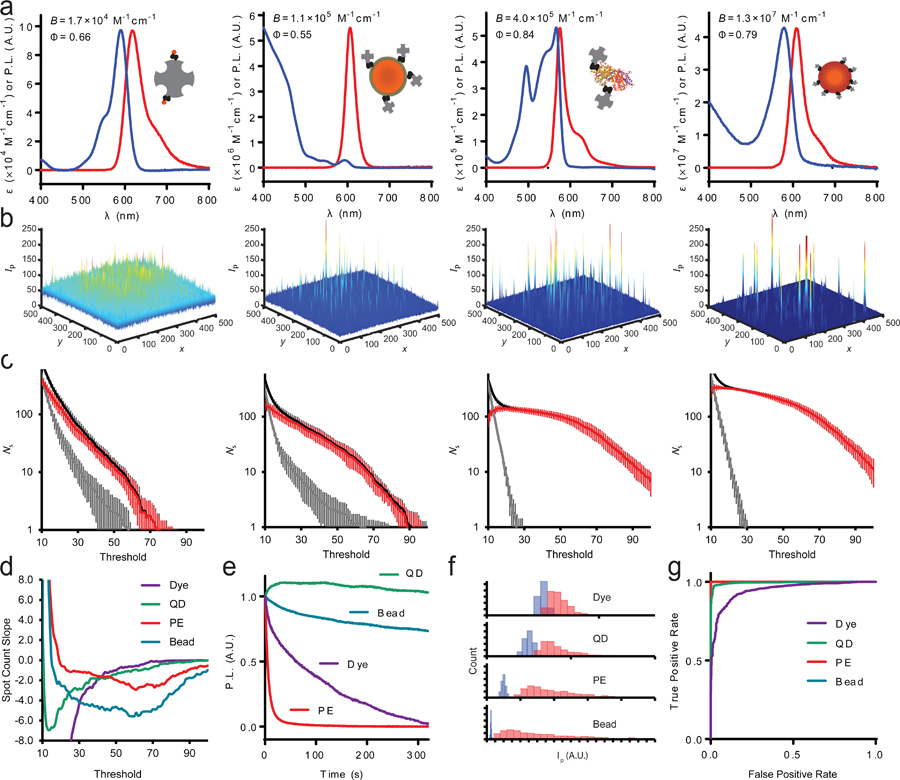

Four fluorophore classes are compared in this work, including an organic molecular dye (Alexa Fluor 594, or dye), semi-conductor nanocrystal quantum dot (Qdot 605, or QD), fluorescent protein (phycoerythrin, or PE), and fluorescent microbead (FluoSphere, or bead), each with emission maximum near 600 nm, efficient excitation at 561 nm, and conjugated to avidin for reaction with biotinylated surfaces or molecular targets.22 Figure 1a shows ensemble spectra of fluorescence emission and extinction coefficient (ε) for each fluorophore, together with fluorescence quantum yield (Φ) and relative brightness (B = ε Φ). The relative brightness values, normalized to that of the dye, are 1.0 (dye), 6.7 (QD), 24 (PE), and 780 (bead). Notably, the brightness of QDs can be boosted by more than an order of magnitude by exciting at a shorter wavelength due to their steeply rising broad-band extinction with decreasing wavelength,23,24 but for this study, matching excitation wavelengths across the materials was necessary for direct comparisons.

Figure 1.

Optical properties of avidin-conjugated fluorophores. (a) Extinction coefficient (ε) spectra and fluorescence emission spectra for avidin conjugates of four fluorophores. From left to right: dye, QD, PE, and bead. For each class, a schematic depiction shows avidin (gray) and the fluorophore in proportion to their relative sizes. Inset values show quantum yield (Φ) and relative brightness (B). (b) Representative single-molecule images of sparse labels on coverglass. (c) Spot detection counts are shown based on PFA detection thresholds for bare coverglass (gray) and those with several hundred fluorophores per FOV (black). The red line shows the difference between the two at each threshold value. Data are averages from >10 FOVs, and error bars indicate standard deviation. (d) Slopes of red curves from panel (c) demonstrate the stability of spot counts depending on chosen PFA threshold. (e) Photostability for the four different fluorophores, showing measured intensity over time of continuous excitation at 561 nm with irradiance of 24.07 W/m2. (f) Spot intensities for indicated fluorophores (red) using a 3 × 3 voxel compared with background values (blue). (g) Receiver operating characteristic curve for fluorophore spots measured using a 3 × 3 voxel. For PE and bead measurements, the area under the curve is unity.

Single-Molecule Spot Detection for Fluorescent Labels.

Each fluorophore−avidin conjugate was bound sparsely to a biotinylated glass coverslip to analyze single-molecule intensities. As average fluorophore brightness spanned a 780-fold range, different image acquisition conditions were needed to prevent detector saturation and to ensure that molecules were detectable across a wide dynamic range above the background. Images were acquired at 100× magnification in total internal reflectance fluorescence (TIRF) mode with an electron-multiplying charge-coupled device (CCD) camera. Images were then analyzed to detect diffraction-limited spots in a 7 × 7 voxel scanning window by fitting to two-dimensional Gaussian functions to approximate the point spread function. The detection and deflation algorithm from the multiple-target tracing (MTT) software of Serge et al. was used to recursively deplete spots in high-density images.25 Example images are shown in Figure 1b, and fitted point spread functions are shown in Supplementary Figure S1. The signal-to-noise differences are apparent when comparing the background levels and spikes in the z-axis between the four samples. For each image, the threshold for spot detection was tuned by the χ2 value for PFA per FOV, shown in Figure 1c. Both PE and beads are readily detectable over the background, with zero background counts for PFA > 30 dB, whereas absolute counts for the dye and QD strongly depend on the selected threshold. The slopes of spot count versus threshold are plotted in Figure 1d, showing that PE, in particular, provides a stable count over a broad threshold range, as the slope is close to zero and stable at low threshold values. Stable counts were not possible with the QD and dye, and the absolute count observed for beads strongly depended on the chosen PFA threshold due to their widely dispersed intensities (see below). For the further analysis below, we chose a PFA of 45 dB to ensure that all counts were within a relatively stable window for direct comparisons between the four fluorophores.

Stability Comparison.

The signal-to-noise ratio for spot detection can be substantially improved by increasing the detection integration time or by averaging across sequentially acquired images (see below); however, if the emitters are not temporally stable, this will reduce the accuracy of intensity measurements. Figure 1e shows decay curves of emission intensity over time of excitation, with decay half-times of 63.2 s (dye), 2040 s (QD), 4.87 s (PE), and 1020 s (beads). The high stability of QDs and microbeads is well-known due to the protective physical structure of the materials, whereas organic dyes and proteins can readily undergo photochemical reactions that result in a nonfluorescent structure.26 While this comparison suggests that PE is highly unstable, this experiment was conducted with high laser intensity, approximately 8.5 times higher than that used for single-molecule imaging. Indeed, there is no need in our detection setup to use long integration times or high laser intensity for PE due to its high detection threshold stability (Figure 1d). However, when higher laser power and extended acquisition times are required for practical applications, PE may not perform well for single-molecule counting.

Single-Molecule Intensity Distributions.

Figure 1f shows histograms of 3 × 3 voxel spot intensities for the four fluorophores. The intensities of PE and beads are well separated from background levels, as would be expected using a PFA of 45 dB (Figure 1c,d). Moreover, the proportionality of mean spot intensities between beads to PE (37.9:1) was close to that measured at the ensemble level (32.5:1), indicating that their average single-molecule intensities will provide accurate correlations to analog intensity measurements. Supplementary Figure S2 shows the intensity distribution dependence on voxel size from 1 × 1 to 9 × 9, demonstrating that spot intensities remain well separated for a wide range of voxel values. The result is unity area under the curve (AUC) for receiver operating characteristic plots for spot detection (Figure 1g) for all voxel sizes besides 1 × 1 for PE (Supplementary Figure S3). These results are similar to those of measurements of QDs, differing by just 16% from the expected ensemble value in comparison with that for beads and PE. However, dyes substantially deviated from expectations as single-molecule intensities significantly overlapped with background values for all voxel sizes between 1 × 1 and 9 × 9 (see Supplementary Figure S2). Dyes were more than 2-fold brighter than expected compared with beads and PE based on ensemble brightness expectations. This discrepancy results from selective measurement of a fraction of the total dye−avidin populations due to the imposed threshold, for which some fraction of the conjugate population likely contains multiple dyes per protein spot within a diffraction-limited spot. As a result, under conditions used here, dyes are not appropriate for calibrating intensities to correlate with absolute target concentrations.

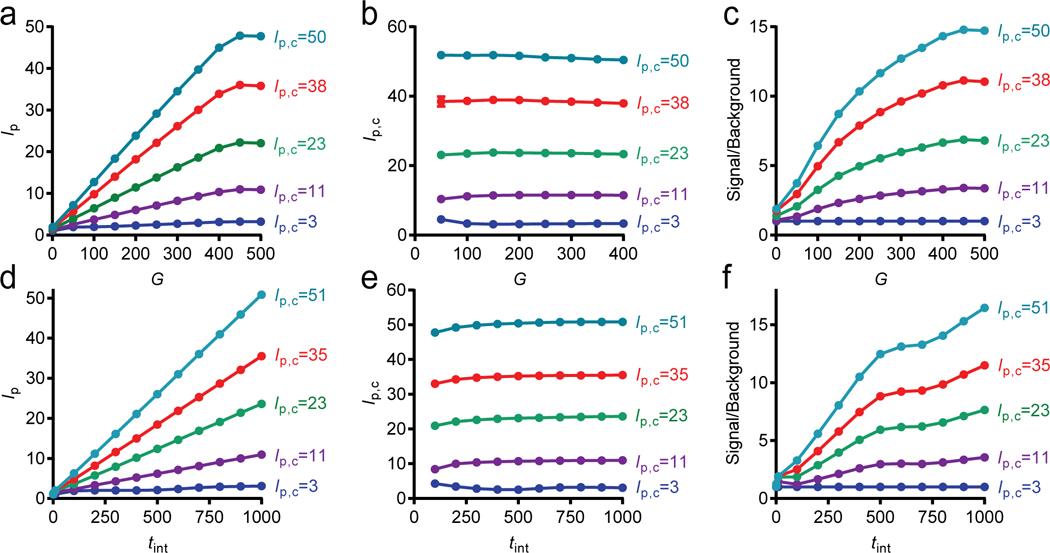

Detector Calibration.

A challenge in quantifying surface fluorescence over a wide range of intensities is the limited utilizable dynamic range of cameras, typically spanning several thousand gray levels. When imaging conditions capable of visualizing dim single molecules are selected, detector saturation can occur when widely varying intensity levels are present in the same FOV.27 We tuned electron-multiplying camera G and tint independently to collect images that were within the utilizable dynamic range of the detector and calibrated intensities to normalize images collected under different acquisition conditions. Figure 2a shows the average pixel intensities from images of surfaces covered with different densities of QDs, imaged across different G values, showing a quasilinear relationship between the average pixel intensity (Ip) and G between 0 and 450. From these curves, gain factors Gf could be calculated as the curve slope for calibration as

| (1) |

where Go is a standard gain value, usually chosen to be 0 or 450. By measuring across a wide range of intensities and gains, the range of measurable intensities could be fully spanned to interpolate any unsaturated intensity collected at any G value. Figure 2b shows the calibrated analog intensities, Ip,c calculated by

| (2) |

showing that these factors accurately normalize broadly ranging intensities across a wide range of gain values with an average coefficient of variation of 1.3%. A key outcome is that, due to the increase in gain factor with intensity, gain provides a means to increase the signal-to-noise ratio compared with blank samples for which there were no fluorophores applied (Figure 2c).27

Figure 2.

Tuning image acquisition conditions to normalize intensities. (a) Dependence of measured mean pixel intensity (Ip) on detector gain (G) for five different surface densities of QDs, indicated by the calibrated pixel intensities (Ip,c) for Go = 450. (b) Calibrated intensity per pixel (Ip,c) after applying linear gain factors in eqs 1 and 2. (c) Impact of gain on image signal relative to surfaces without fluorophores. (d−f) Same analysis using integration times to calibrate image intensity. Calibrated pixel intensities are shown for tinto = 1000. All data points include standard deviation error bars.

We repeated this same methodology for digital spot analysis of sparse QD images rather than analog intensity analysis and found that the gain factors were similar for 3 × 3 spot voxels, with an average coefficient of variation in calibrated measured intensity of 2.0% (Supplementary Figure S4). Similarly, when applied to individual pixels across a whole image, gain factors exhibited little variation (Supplementary Figure S5). We further applied the same calibration methodology by using tint as the means to span a broad range of intensities, shown in Figure 2d−f. This more broadly applicable method, for which numerous low-cost detectors can be used, yielded an average coefficient of variation of 3.7% of calibrated intensities and a similar increase in signal-to-noise ratio with increasing tint but may not be accurate when labels are not photostable. Gain factors are provided in Supplementary Figure S6.

Calibration of Spot Intensities.

Using this methodology to normalize fluorescence across a wide range of intensities using gain factors, single-molecule counts were correlated with analog fluorescence intensities spanning a wide range of label densities on a surface. Pixel intensities were normalized by Gf value based on the method described above (eqs 1 and 2). To determine which images should be analyzed using analog or single-molecule digital analysis, the limit of detection (LOD) for analog images was calculated by determining the fluorophore concentration at which the image mean fluorescence was equal to 3 times the standard deviation of the zero concentration background value.28 For all values below the analog LOD, single-molecule counting was applied to calculate the mean intensity of a fluorescent spot contributing to a FOV at a specific gain value, :

| (3) |

where is the average voxel intensity of a fluorophore spot, is the average voxel intensity from background, and k is a factor accounting for the fraction of total intensity within the voxel, derived from a Gaussian fit of the point spread function (Supplementary Figure S1).29 The number of spots per FOV in an analog image can be calculated as

| (4) |

where Ip,c,b is the calibrated background level per pixel and Np is the number of pixels per image.

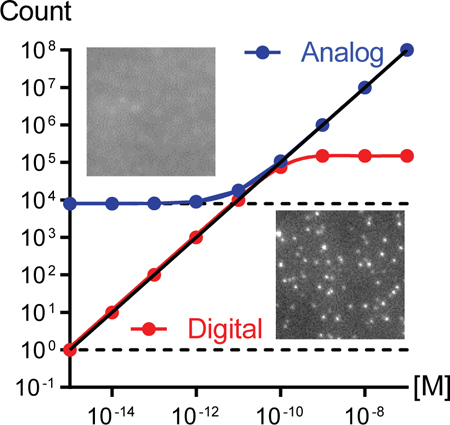

Fluorophore-Dependent Dynamic Range.

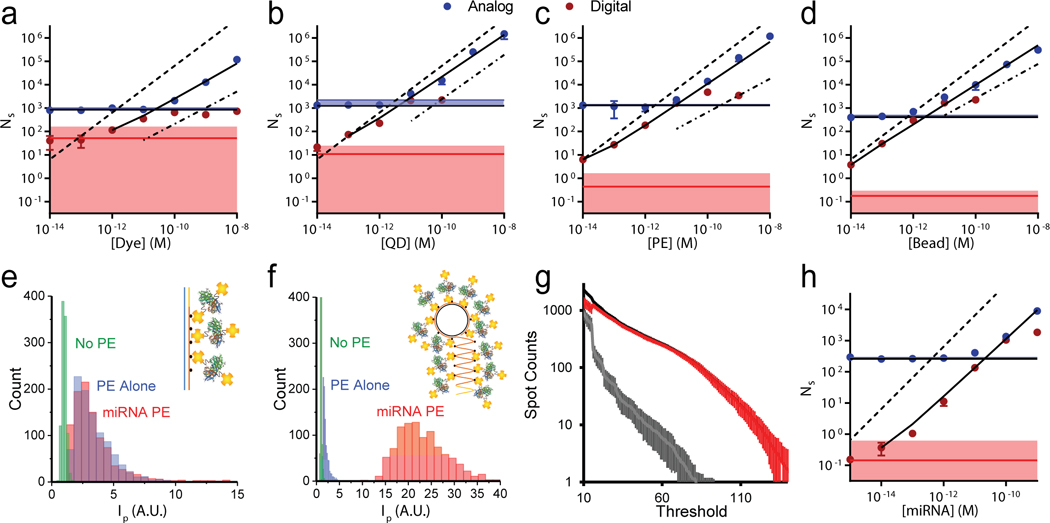

We evaluated the capacity of this methodology to expand the dynamic range (DR) for each of the four avidin-conjugated fluorophores captured from a controlled range of solution concentrations to biotin-functionalized surfaces. Figure 3a−d shows digitally measured spot counts in red and calibrated analog spot counts in blue across 6 orders of magnitude of fluorophore solution concentration. The horizontal red and blue lines indicate the background levels in digital and analog format, respectively, and shaded areas indicate the LOD for both formats. For each fluorophore type, the black line is a regression across both ranges, showing expansion below the analog LOD and conversion of analog measurements to absolute counts. Table 1 shows the LOD for analog and digital assay ranges, the full DR, and the R2 value for a full linear regression for each fluorophore class. The DR expanded the most in the order of bead > PE > QD > dye, and all assays reached the picomolar to femtomolar level with 4−7 log(10) DR, each with a R2 value near 0.99. The DR and LOD improved most for PE and beads due to their intense single-fluorophore brightness that was far greater than the back-ground, allowing accurate identification of individual molecules above background counts. Each of these limits could be further improved by tuning thresholds specifically for each fluorophore class.

Figure 3.

Single-molecule intensity calibration to extend fluorescence assay range. (a−d) Digital spot counts (red) and calibrated spot counts from analog intensity measurements (blue) are shown as points at the indicated avidin−fluorophore conjugate concentration, showing (a) dyes, (b) QDs, (c) PE, and (d) beads. The black line is a fit connecting analog data points that are above the analog limit of detection (horizontal blue shading) to digital points above the digital limit of detection (horizontal red shading). Dashed lines indicate the theoretical values if all solution fluorophores were detected, and dash-dotted lines indicate spot counts due to nonspecific labeling for surfaces without biotin, extrapolated from data in Supplementary Figure S7. (e) Spot intensity histograms for PE, miRNA labeled with PE through linear extension, and no PE background. (f) Spot intensity histograms for PE, miRNA labeled with PE through rolling circle amplification (RCA) extension, and no PE background. (g) Spot counts based on PFA thresholds for bare coverslips (gray) and those with several hundred RCA-extended miRNA per FOV (black). Both were labeled with avidin−PE conjugates. The red line shows the difference between the two at each threshold value. Data are averages from >10 FOV, and error bars indicate standard deviation. (h) Digital spot counts and calibrated spot counts from analog intensity measurements for PE-labeled RCA products of miRNA, using the same notations as used in panel (a).

Table 1.

Assay Metrics for Each Fluorophore Class

| dye | QD | PE | bead | RCA–PE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analog LOD (M) | 8.35 × 10−11 | 1.47 × 10−11 | 1.16 × 10−11 | 6.50 × 10−12 | 3.26 × 10−11 |

| Digital LOD (M)a | 2.69 × 10−12 | 5.11 × 10−14 | 5.32 × 10−15 | 4.57 × 10−16 | 2.93 × 10−14 |

| DR (M) | 1.66 × 104 | 4.98 × 105 | 8.16 × 106 | 4.01 × 107 | 1.64 × 105 |

| R2 | 0.987 | 0.990 | 0.996 | 0.998 | 0.991 |

For PE and bead, extrapolated from exponential fit.

Impact of Optical Surface Defects.

The surfaces used for these fluorescence capture assays have a major impact on the outcomes, as fluorescent imperfections intrinsic to microscopy-grade borosilicate glass can introduce background signals. The impact is particularly problematic for the dye measurements, for which singe-molecule intensities are similar to those of glass defects, making the threshold selection value incredibly important for detection sensitivity (see Figure 1c).30 With customized conditions, results with dyes can likely be significantly improved, especially with the use of quartz or other ultrapure (but expensive) substrates.31 Notably, the absolute number of dyes was substantially underestimated due to ineffective discrimination of dim dyes from fluorescent glass impurities, shown by the dashed lines in Figure 3a−d, which indicate theoretical spot numbers if all fluorophores in solution adsorbed to the surface. Whereas surface capture reactions are not expected to approach completion under conditions applied here,32 measured dye counts were much lower than those of the three other fluorophore classes, for which a higher single-molecule brightness provided an improved limit of detection and a correspondingly wider assay DR (Table 1).

Impact of Nonspecific Binding.

For fluorescence assays in which unbound labels can adsorb to assay surfaces, nonspecific label binding can significantly contribute to background signals to worsen the LOD.33 We analyzed the contribution of specific and nonspecific binding in these analytical tests for avidin conjugates described above. We used glass surfaces densely conjugated to 5000 Da methoxy-terminated polyethylene glycol to minimize surface adsorption34 and performed all labeling steps with a large excess of bovine serum albumin (BSA) to colloidally block random protein binding. Despite this, there was a strong concentration-dependent contribution to surface labeling from nonspecific binding for all fluorophore classes, measured using surfaces without biotin, shown as dot-dashed lines in each panel of Figure 3a−d, and plotted separately in Supplementary Figure S7. Even though all fluorophores were linked to avidin, the magnitude of nonspecific binding differed strongly across the fluorophore classes and was highest for QDs and beads. High nonspecific labeling of colloidal nanomaterials like beads and QDs is well-known35 and can be overcome by designer surface chemistries and optimized blocking agents, whereas optimized wash steps can further improve nonspecific adhesion of for all fluorophore classes.35–37

The dependence of nonspecific binding on label concentration establishes a critical trade-off between LOD and DR. This is because the concentration of the fluorophore label must exceed the maximum analyte concentration of the assay in order for the analyte to be quantified at high concentration. For each fluorophore tested in this assay, a concentration of 10 nM resulted in overwhelming background adsorption such that there was almost no extension of the analyte-specific assay signal into the single-molecule counting domain. Applying a much lower label concentration does enable an improved LOD but at the expense of a reduced DR at higher analyte concentration. Below we show that this fundamental trade-off between LOD and DR can be overcome through dense fluorophore labeling of target analytes.

Impact of the Calibration Procedure.

The accuracy of this assay can be substantially impacted by the methodology applied to calibrate intensities. Under ideal conditions, the digital and ensemble assays in Figure 3a−d can be calibrated simply by equalizing the two trend line slopes at their point of intersection.38 However, as shown in Supplementary Figure S8a, doing so with the dye led to widely varying results, spanning nearly 2 orders of magnitude of calibrated spot counts, depending on the arbitrary threshold imposed for digital spot counting. This effect arises from the similar dependence of both dye counts and autofluorescent spot counts on the threshold. In contrast, the same method with PE did not result in dramatic variation in the estimation of calibrated spot counts (Supplementary Figure S8b), as PE spot counts remained relatively constant at all threshold values due to much higher intensity compared with autofluorescent spots (Figure 1d). Although the number of autofluorescent spots detected did change as a function of the threshold, a consistent PE count allowed the curves to converge at a similar count number. Thus, accurate calibration using slope equalization requires an emitter that is substantially brighter than the background.

The bias of the calibration due to arbitrary spot counting thresholds can be overcome by simply normalizing the intensities to an absolute standard. The absolute intensity of an individual emitter is ideal because it is a fundamental photophysical parameter. PE assays calibrated by absolute intensity show monotonically increasing and continuous spot counts with concentration, suitable for a robust analytical assay, but dye assays exhibit substantial discontinuities depending on the detection thresholds (Supplementary Figure S8c,d). An additional advantage for PE compared with beads and QDs is that the former is molecularly precise, whereas the latter two are synthetic nanoparticles that can exhibit substantial polydispersity and batch-to-batch variability in intensity.

miRNA Counting by Rolling Circle Amplification.

To demonstrate an application of wide DR of analyte detection by molecular counting and intensity calibration, we developed an analytical platform for the detection of miRNA, a critically important biomolecule that regulates gene expression and for which precise quantification in blood and other bodily fluids is needed to serve as a biomarker for a variety of diseases.9,39 In particular, we measured miR375, a 22-mer RNA that has prognostic value in metastatic prostate cancer survival40 and is involved in the development of chemoresistance to docetaxel by regulating SEC23A and YAP1 expression.39 Docetaxel chemotherapy is a commonly used therapy in metastatic prostate cancer, which has a 40−50% response rate and has no validated predictive biomarkers. Detection and measurement of miR375 levels in the blood of advanced prostate cancer patients thus has clinical relevance in the management of cancer patients but is challenging to perform as it is in low abundance in body fluids like plasma or whole blood.

Driven by the aforementioned trade-off between LOD and DR derived from nonspecific binding, we developed two methodologies to fluorescently label miR375 in which the number of labels would be large so that target molecules could be accurately counted as spots over a background of single nonspecifically bound labels. In the first approach, the miRNA was enzymatically extended to 89 nucleotides using biotinylated uridine triphosphate (biotin-dUTP) and then captured to an azide-functionalized glass coverslip through click chemistry before being labeled with avidin−PE conjugates. PE was selected as the fluorescent label because of optimal signal thresholding, homogeneity of signal intensities, and low nonspecific binding. Temporal acquisition ranges were selected over which photobleaching did not impact our results. As shown in Figure 3e, the intensity of miRNAs labeled with PE through linear extension could be readily distinguished over surface background, but spot intensities were not substantially greater than those of individual PE, despite the presence of numerous biotins per nucleic acid. Although this approach did allow imaging and counting of miRNA, the LOD was severely limited by false spot counts from nonspecific avidin−PE adsorption. To overcome this problem, the number of labeling sites was drastically expanded using rolling circle amplification (RCA) with biotin-dUTP.41–43 RCA products are large macromolecules and thus can be more densely labeled with avidin−PE. As shown in Figure 3f and Supplementary Figure S9, spots were drastically brighter than background and PE alone, with 3 × 3 voxel intensities that were 11 times higher than background and 9.9 times higher than PE alone, allowing facile identification of labeled analytes over background. Figure 3g shows the threshold sensitivity curve, comparing PE and RCA products labeled with PE, such that PFA of 90 dB completely eliminated background counts, despite extensive nonspecific PE capture. Figure 3g shows an example of the assay using the same PFA of 45 used in Figure 3a−d, showing the quantification of miR375 by molecular counting and intensity calibration over a 100,000-fold concentration range with linear R2 of 0.991, corresponding to a concentration 1000-times lower than the analog detection limit, with a LOD of 29 fM. Notably, the LOD can be tuned to much lower levels by imposing a higher PFA threshold, which will offset the DR by reducing the observed capture density. This outcome demonstrates the extensive degree to which the limits of nonspecific binding in fluorescence surface assays can be overcome by applying spot counting together with densely labeled analytes.

CONCLUSIONS

Here, we developed and optimized a workflow for optical quantification of fluorescently labeled molecules, showing that fluorescent spot counting can expand the limit of detection and dynamic range of surface assays by more than 3 orders of magnitude by registering analog intensity measurements to molecular numbers. Numerous challenges can limit the success of this approach, as we observed that outcomes are strongly dependent on the class of fluorophore applied, with each providing specific photophysical properties uniquely beneficial or detrimental to this application. Phycoerythrin surprisingly stood out as an exceptional label due to its bright and homogeneous emission allowing facile counting far above the substrate background to overcome frequently overlooked biases imposed by arbitrary spot counting thresholds. In addition, we demonstrate that the trade-off between detection limit and dynamic range imposed by nonspecific fluorophore label adhesion can be largely eliminated by using densely labeled analytes. Rolling circle amplification, in particular, generates highly fluorescent miRNA amplicons so that single-molecule signals can be easily differentiated from a field of nonspecifically bound fluorophores that result from high label concentrations needed for a wide dynamic range. The development of new strategies for dense analyte labeling can allow this strategy to be applied to a broader range of target classes. We expect that this methodology will be especially impactful for assays in which large variations in analyte concentration are present, such as cell-free DNA or circulating miRNAs,20,21 and for assays in point-of-care devices in which sample volume and replicate number are limiting.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Chemicals and Reagents.

Coverglass (no. 15) was purchased either as 22 × 30 mm coverslips from VWR (48393–150) or as 50-well chambers from Electron Microscopy Sciences (70460–50R). Monomethoxy monosuccinimidyl ester poly(ethylene glycol) (mPEG5000-NHS, 5000 Da), monobiotin monosuccinimidyl ester poly(ethylene glycol) (biotin-PEG5000-NHS, 5000 Da), and monoazido monosuccinimidyl ester poly(ethylene glycol) (azide-PEG5000-NHS, 5000 Da) were purchased from Nanocs, Inc. Avidin-labeled phycoerythrin (405203) and Alexa 594 (405240) were purchased from BioLegend. Avidin-labeled Quantum Dot 605 nm (Q10103MP) and FluoSpheres (F8770) were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific. Sodium hydroxide (>97%), glacial acetic acid (>99.7%), sodium bicarbonate (>99.7%), tris(hydroxymethyl)-aminomethane (Tris base), Tween 20, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), biotin-dUTP (40029), SYBR Green I nucleic acid gel stain (SYBR Green), and SYBR Gold nucleic acid gel stain (SYBR Gold) were also purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific. Deoxy-nucleotide solution mix (dNTP), phi29 DNA polymerase (Φ29 polymerase), and Escherichia coli exonuclease I were purchased from New England Biolabs. CircLigase II was purchased from Lucigen. DNA or RNA oligonucleotides (oligos) with sequences shown in Table 2 were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies and purified by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; some oligos were modified with 5′-dibenzylcyclooctyne (DBCO) with tetraethylene glycol spacer (/5DBCOTEG/) or 5′-phosphate (5APhos). Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was purchased from Corning. In-house purified Milli-Q water was used throughout. Unless specified, all other chemicals and solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without further purification.

Table 2.

Oligonucleotide Sequences Used in This Work

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| miR375 | rUrUrUrGrUrUrCrGrUrUrCrGrGrCrUrCrGrCrGrUrGrA |

| DBCO-α-miR375 | /5DBCOTEG/ACTTTACTTTACTTTACTTTACTTTACTTTACTTTACTTTACTTTACTTTACTTTACTTTACTTTACTCACGCGAGCCGAACGAACAAA |

| RCA template | /5Phos/CAACAACCAACAAACACAGAATGCTCACGCGAGCCGAACGAACAAACCTCAGCAACACCAAACAACAAAC |

Coverglass Functionalization.

Coverglass was prepared in batches of 10 using staining racks. Coverglass was cleaned with 1 M NaOH with sonication for 10 min, washed 10 times with water, and dried by centrifugation at 500g for 5 min or by nitrogen flush. Surfaces were cleaned with plasma and immediately incubated in a solution of 93.46% methanol, 4.67% glacial acetic acid, and 1.87% 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane for 10 min at room temperature. Samples were then sonicated for 1 min, incubated for an additional 10 min at room temperature, washed 10 times with water, and dried by centrifugation at 500g for 5 min or by nitrogen flush. A freshly prepared solution containing 2.375% (w/v) mPEG5000-NHS and 0.125% (w/v) biotin-PEG5000-NHS or 0.125% (w/v) azide-PEG5000-NHS in 100 mM sodium bicarbonate was then applied to the coverslip surfaces. For chambered coverglass, PEG solutions were applied directly to each well (4 μL per well). For coverslips, the PEG solution was applied to one coverslip (20 μL) and sandwiched with a second coverslip. The surfaces were then incubated in a humidified chamber for 3 h, washed 10 times with water, dried by centrifugation at 500g for 5 min or by nitrogen flush, and stored at −20 °C until use. DNA-functionalized coverglass was prepared by conjugating DBCO-oligos to azide-functionalized coverslips through strain-promoted azide−alkyne click (SPAAC) reactions. For these reactions, oligos at 20 nM in high salt phosphate buffer (900 mM sodium chloride, 20 mM Tris base, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% Tween 20, pH 7.4) were incubated on coverglass for 4 h at room temperature and then washed four times with PBS prior to use.44,45

Avidin−Fluorophore Binding to Biotinylated Surfaces.

Biotin-functionalized coverslips were incubated with avidin-labeled phycoerythrin, Alexa 594, quantum dot 605 nm, or FluoSpheres across a range of concentrations in PBS containing 2% BSA. For each reaction, a 4 μL volume was applied to the surface in a humidified chamber for 1 h at room temperature and then washed six times with 10 mL of PBS, covered with a second coverslip, and imaged immediately.

Linear DNA Amplification.

DBCO-α-miR375 was hybridized with miR375 (Table 2) at 100 nM in polymerase buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM (NH4)2SO4, and 4 mM dithiothreitol at pH 7.5) for 1 h at room temperature. The DBCO-α-miR375 sequence was designed to contain an extension region at the 5′ end of the complementary sequence to miR375 so that the RNA could be enzymatically extended by 67 bases as biotin-labeled DNA. The reaction was performed under isothermal conditions at 37 °C for 1 h in reaction buffer (200 nM dNTPs, 200 nM biotin-dUTP, 0.2 mg/mL BSA, 0.01% SYBR Green, 0.5 U/μL Φ29 polymerase). The resulting amplicon hybrids were then conjugated to coverglass by SPAAC reactions, washed with PBS, labeled with avidin−phycoerythrin (10 nM) in a PBS solution containing 2% BSA for 1 h at room temperature, washed with PBS, and immediately imaged.

Rolling Circle Amplification.

Circularization of the 5′-phosphoryl RCA template (Table 2) was performed at 2 μM using CircLigase II (2.5 U/μL) in CircLigase buffer (0.33 M Tris-acetate, 0.66 M potassium acetate, 2.5 mM MnCl2, and 5 mM dithiothreitol at pH 7.5) for 1 h at 60 °C.46 Unreacted linear DNA was removed by reaction with exonuclease I for 1 h at 37 °C. The circularized RCA template sequence was designed to contain a complementary sequence to miR375 and numerous adenosines so that rolling circle amplification could be used to append a large DNA sequence to each miR375 with numerous biotins when polymerized in the presence of biotin-dUTP. The circular RCA template (100 nM) was hybridized with miR375 (10 nM) in polymerase buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM (NH4)2SO4, and 4 mM dithiothreitol at pH 7.5) for 1 h at room temperature. Isothermal RCA was then performed in reaction buffer (200 nM dNTPs, 200 nM biotin-dUTP, 0.2 mg/mL BSA, 0.01% SYBR Green, and 0.5 U/μL Φ29 polymerase) for 1 h at 37 °C. Amplicons were then diluted and conjugated to glass coverslips functionalized with complementary DNA, washed with PBS, labeled with avidin−phycoerythrin (10 nM) in a solution containing 2% BSA for 1 h at room temperature, washed with PBS, and immediately imaged.

Optical Spectroscopy.

Fluorescence spectra were collected with a Horiba NanoLog spectrofluorometer using Fluo Essence V3.5 software. Ultraviolet−visible absorption spectra were acquired using a Cary 5000 UV−vis−NIR spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies) using Cary WinUV scan application version 6.00 1551 software. For fluorescence quantum yield measurements, each fluorophore solution was diluted to an absorption value of ∼0.1 at 561 nm, and quantum yield was calculated relative to a reference dye (Rhodamine 101, QY = 91%).23,47

Image Acquisition.

Samples were imaged via wide-field illumination on a Zeiss Axio Observer.Z1 inverted microscope with 100× 1.45 NA Alpha PlanFluar oil immersion objective using a 561 nm laser excitation and a 600 nm band-pass filter. Images were collected with a Photometrics eXcelon Evolve 512 electron-multiplying CCD controlled using Zeiss Zen software. Laser excitation intensity, integration time, and camera gain were adjusted, and conditions were recorded for each experiment. Images were exported as 8-bit 512 × 512 TIFF files. For photobleaching studies, fluorophores captured to biotinylated surfaces were imaged with laser excitation (40 mW, 25% power) with 400 ms integration time.

Data Analysis Methods.

Mean fluorescence intensity values per pixel from images were measured using ImageJ software.48 Single-molecule images were analyzed in MATLAB using the MTT algorithm of Serge et al. and custom scripts to identify and count spots.25 Field-of-view single-molecule counts or mean fluorescence values were used to generate individual sample data points using the average of single-molecule counts or mean fluorescence values for 10 images from different fields of view for a single technical replicate. Spot intensities were calculated from square voxels centered at the centroid of each detected spot, and the fraction of fluorophore intensity in the voxel was estimated from a Gaussian fit of the point spread function. Receiver operating characteristic curves were generated from single-molecule images and background images containing no fluorophores. Experimental data points and error bars represent the mean and standard deviation for at least three technical replicates. Limit of detection was determined by calculating the concentration corresponding to the background signal plus 3 times the background standard deviation. The upper limit of detection for single-molecule images was determined by the minimum concentration corresponding to the maximum single-molecule count values, and for analog images, the maximum fluorophore concentration measured was used if images did not exhibit intensity saturation. Dynamic range was calculated from a regression of data points from the lower limit of detection to the upper limit of detection.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R00CA153914 to A. M.S., R01CA227699 to A.M.S. and M.K.; R01CA21209 to M.K.), the Department of Defense (W81XWH-15–1-0634 to M.K.), the Mayo-Illinois Alliance (to A.M.S.), the Mayo Clinic Center for Individualized Medicine (to M.K.), and Mayo Clinic Development by Joseph Gassner, Roger Thrun, and John P. Vaile (to M.K.).

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.8b08879.

Fluorescence microscopy images and histograms of single molecules with corresponding receiver operating characteristic curves; dependence of intensities on detector gain; dependence of gain factors on intensities of pixels and spot voxels; normalization factors for gain and integration time; nonspecific binding of avidin-conjugated fluorophores; fluorescence microscopy image of RCA products (PDF)

REFERENCES

- (1).Lakowicz JR Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy, 3rd ed.; Springer, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Stockert JC; Blazquez-Castro A Flourescence Microscopy in Life Sciences; Bentham Science Publishers, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Frgala T; Kalous O; Proffitt RT; Reynolds CP Mol. Cancer Ther 2007, 6, 886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Jiang L; Yu Z; Du W; Tang Z; Jiang T; Zhang C; Lu Z Biosens. Bioelectron 2008, 24, 376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Zhao S; Fung-Leung WP; Bittner A; Ngo K; Liu X PLoS One 2014, 9, e78644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Black MB; Parks BB; Pluta L; Chu TM; Allen BC; Wolfinger RD; Thomas RS Toxicol. Sci 2014, 137, 385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Gomella LG Can. J. Urol 2017, 24, 8693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Geyer PE; Holdt LM; Mann M; Teupser D Mol. Syst. Biol 2017, 13, 942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Rapisuwon S; Vietsch EE; Wellstein A Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J 2016, 14, 211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Borrebaeck CA Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Makrigiorgos GM; Chakrabarti S; Zhang Y; Kaur M; Price BD Nat. Biotechnol 2002, 20, 936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Thompson MA; Lew MD; Moerner WE Annu. Rev. Biophys 2012, 41, 321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Walt DR Anal. Chem 2013, 85, 1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Mir KU Genome Res 2006, 16, 1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Gooding JJ; Gaus K Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2016, 55, 11354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Shivanandan A; Deschout H; Scarselli M; Radenovic A FEBS Lett 2014, 588, 3595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Geiss GK; Bumgarner RE; Birditt B; Dahl T; Dowidar N; Dunaway DL; Fell HP; Ferree S; George RD; Grogan T; et al. Nat. Biotechnol 2008, 26, 317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Eid J; Fehr A; Gray J; Luong K; Lyle J; Otto G; Peluso P; Rank D; Baybayan P; Bettman B; et al. Science 2009, 323, 133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Fischer SK; Joyce A; Spengler M; Yang TY; Zhuang Y; Fjording MS; Mikulskis A AAPS J 2015, 17, 93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Schwarzenbach H; Stoehlmacher J; Pantel K; Goekkurt E Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 2008, 1137, 190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Bissels U; Wild S; Tomiuk S; Holste A; Hafner M; Tuschl T; Bosio A RNA 2009, 15, 2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Nguyen DC; Keller RA; Jett JH; Martin JC Anal. Chem 1987, 59, 2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Lim SJ; Zahid MU; Le P; Ma L; Entenberg D; Harney AS; Condeelis JS; Smith AM Nat. Commun 2015, 6, 8210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Geissler; Wurth C; Wolter C; Weller H; Resch-Genger U Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2017, 19, 12509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Serge A; Bertaux N; Rigneault H; Marguet D Nat. Methods 2008, 5, 687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Marx V Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Pang Z; Laplante NE; Filkins RJ J. Microsc 2012, 246, 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Armbruster DA; Pry T Clin. Biochem. Rev 2008, 29, S49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).DeSantis MC; DeCenzo SH; Li JL; Wang YM Opt. Express 2010, 18, 6563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Peterson EM; Harris JM Anal. Chem 2010, 82, 189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Gust A; Zander A; Gietl A; Holzmeister P; Schulz S; Lalkens B; Tinnefeld P; Grohmann D Molecules 2014, 19, 15824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Li J; Baird MA; Davis MA; Tai W; Zweifel LS; Waldorf KMA; Gale M Jr; Rajagopal L; Pierce RH; Gao X Nat. Biomed. Eng 2017, 1, 0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Zanetti-Domingues LC; Tynan CJ; Rolfe DJ; Clarke DT; Martin-Fernandez M PLoS One 2013, 8, e74200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Rasnik I; Myong S; Cheng W; Lohman TM; Ha TJ Mol. Biol 2004, 336, 395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Rosenthal SJ; Chang JC; Kovtun O; McBride JR; Tomlinson ID Chem. Biol 2011, 18, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Kairdolf BA; Mancini MC; Smith AM; Nie SM Anal. Chem 2008, 80, 3029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Hua B; Han KY; Zhou R; Kim H; Shi X; Abeysirigunawardena SC; Jain A; Singh D; Aggarwal V; Woodson SA; et al. Nat. Methods 2014, 11, 1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Peterson EM; Manhart MW; Harris JM Anal. Chem 2016, 88, 1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Wang J; Chen J; Sen SJ Cell. Physiol 2016, 231, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Huang X; Yuan T; Liang M; Du M; Xia S; Dittmar R; Wang D; See W; Costello BA; Quevedo F; et al. Eur. Urol 2015, 67, 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Miao P; Wang B; Meng F; Yin J; Tang Y Bioconjugate Chem 2015, 26, 602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Meyer R; Giselbrecht S; Rapp BE; Hirtz M; Niemeyer CM Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2014, 18, 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Yao J; Flack K; Ding L; Zhong W Analyst 2013, 138, 3121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Agard NJ; Prescher JA; Bertozzi CR J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 15046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Johansson LBG; Simon R; Bergström G; Eriksson M; Prokop S; Mandenius C-F; Heppner FL; Åslund AKO; Nilsson KPR Biosens. Bioelectron 2015, 63, 204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Gadkar VJ; Filion MJ Microbiol. Methods 2011, 87, 38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Valeur B; Berberan-Santos MN Molecular Fluorescence: Principles and Applications, 2nd ed.; Wiley-VCH, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Schindelin J; Arganda-Carreras I; Frise E; Kaynig V; Longair M; Pietzsch T; Preibisch S; Rueden C; Saalfeld S; Schmid B; et al. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.