ABSTRACT

Background

The literature regarding the relation between egg consumption and type 2 diabetes (T2D) is inconsistent and there is limited evidence pertaining to the impact of egg consumption on measures of insulin sensitivity.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of dietary whole egg on metabolic biomarkers of insulin resistance in T2D rats.

Methods

Male Zucker diabetic fatty (ZDF) rats (n = 12; 6 wk of age) and age-matched lean controls (n = 12) were randomly assigned to be fed a casein- or whole egg–based diet. At week 5 of dietary treatment, an insulin tolerance test (ITT) was performed on all rats and blood glucose was measured by glucometer. After 7 wk of dietary treatment, rats were anesthetized and whole blood was collected via a tail vein bleed. Following sedation, the extensor digitorum longus muscle was removed before and after an intraperitoneal insulin injection, and insulin signaling in skeletal muscle was analyzed by Western blot. Serum glucose and insulin were analyzed by ELISA for calculation of the homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR).

Results

Mean ITT blood glucose over the course of 60 min was 32% higher in ZDF rats fed the whole egg–based diet than in ZDF rats fed the casein-based diet. Furthermore, whole egg consumption increased fasting blood glucose by 35% in ZDF rats. Insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of key proteins in the insulin signaling pathway did not differ in skeletal muscle of ZDF rats fed casein- and whole egg–based diets. In lean rats, no differences were observed in insulin tolerance, HOMA-IR and skeletal muscle insulin signaling, regardless of experimental dietary treatment.

Conclusions

These data suggest that whole body insulin sensitivity may be impaired by whole egg consumption in T2D rats, although no changes were observed in skeletal muscle insulin signaling that could explain this finding.

Keywords: whole egg, egg consumption, insulin signaling, insulin resistance, diabetes, rat

Introduction

The increasing prevalence of type 2 diabetes (T2D) is a critical public health issue and insulin resistance is a key contributor to T2D development (1, 2). Insulin resistance is a condition characterized by hyperinsulinemia, hyperglycemia, and impaired glucose and insulin tolerance (3). Diet is an important modifiable risk factor for insulin resistance and the progression of T2D. Therefore, understanding the relation between dietary components, such as whole egg, and insulin resistance is essential for developing future dietary recommendations for the millions of individuals with existing T2D, as well as those who are at high risk for developing T2D.

Insulin mediates its metabolic effects by binding to the insulin receptor, thereby modifying the activity and intracellular location of proteins involved in the insulin signaling pathway. Insulin binding to the insulin receptor triggers autophosphorylation of the insulin receptor (IR) β subunit, which activates the receptor and initiates a cascade of phosphorylation events (4). Key events in the insulin signaling cascade include the activation of the insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) via tyrosine phosphorylation; serine/threonine phosphorylation of Akt and its subsequent activation; phosphorylation of Akt substrate 160 (AS160) at serine/threonine residues; and translocation of the glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) from intracellular vesicles to the plasma membrane, resulting in increased glucose uptake in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue (5–7). Defects in insulin function through the sequential action of the insulin receptor, IRS-1, Akt, AS160, and GLUT4 have been reported in metabolic disorders associated with insulin resistance, such as obesity and T2D (6, 8). Impaired insulin signaling at any of these key steps reduces the ability of insulin to promote glucose uptake and utilization.

Limited and inconsistent findings have been reported on the relation between egg consumption and T2D. Whereas some studies suggest that egg consumption increases the risk of T2D (9–11), others report a null association or a beneficial impact on T2D risk and outcomes (12–17). A meta-analysis found no association between egg consumption and T2D risk in countries outside of the United States, but found a modest increase in T2D risk that was restricted to US studies, suggesting that these results may be confounded by factors such as dietary behaviors of the US population (18). Results from a recent human study suggest that the apparent association between egg consumption and T2D risk in the US population may be due to an interaction between meat and egg intake, and not egg intake alone (19).

It is widely recognized that obesity is a major risk factor for insulin resistance, which precedes the onset of overt diabetes (1–3). We previously reported that a whole egg–based diet attenuates cumulative body weight gain in the Zucker diabetic fatty (ZDF) rat, a well-characterized genetic model of obesity and T2D (20, 21). The observed attenuation in body weight gain was attributed, in part, to an 8% reduction in body fat in ZDF rats consuming a whole egg–based diet (20). Furthermore, we extended this research to a diet-induced model of obesity and demonstrated that whole egg consumption in diet-induced obese rats markedly reduces weight gain compared with that in diet-induced obese rats fed a casein-based diet (CJ Saande, SK Jones, KE Hahn, CH Reed, MJ Rowling, KL Schalinske, unpublished observations, 2017). There is very limited evidence regarding the association between egg consumption and measures of insulin sensitivity (13, 22, 23), and, to our knowledge, the impact of whole egg consumption on insulin signaling has not been examined. Thus, the objective of this study was to investigate whether the previously observed reductions in adiposity in ZDF rats fed a whole egg–based diet are related to improved insulin sensitivity and enhanced insulin signaling.

Methods

Rats and diets

All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Iowa State University (IACUC no. 1-18-8674-R; approval date December 1, 2018) and were performed according to the Iowa State University Laboratory Animal Resources Guidelines. Male ZDF (fa/fa) rats (n = 12) and lean (fa/+) control rats (n = 12) were purchased at 5 wk of age (Charles River Laboratories). Rats were housed 2/cage with a 12-h light-dark cycle in a temperature-controlled room. All rats were acclimated to a semipurified diet (AIN-93 G) for 1 wk. Following acclimation, rats were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 experimental diets (Table 1): a casein-based diet (n = 12) or a whole egg-based diet (n = 12). Both diets provided protein at 20% (wt/wt) and were matched for lipid content (17.7% total lipid) via the addition of corn oil to the casein-based diet to account for the additional lipid contribution of the whole egg. Total protein at 20% (wt/wt) in the whole egg-based diet was achieved by the addition of 413 g/kg dried whole egg, which provided 48.4% (200 g) protein and 42.9% (177 g) lipid. Diets were prepared weekly and rats were given ad libitum access to food and water for a period of 7 wk. Body weight and food intake were recorded 5 d/wk. Prior to killing the animals, food was withheld for 4 h and rats were anesthetized via a single intraperitoneal injection of ketamine:xylazine (90:10 mg/kg body weight). Following sedation, whole blood was collected via a tail vein bleed and blood samples were stored on ice until centrifugation. The extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscle was removed from one leg prior to an insulin injection to account for basal differences in insulin signaling. All rats were then given an intraperitoneal insulin injection (Sigma; 10 U/kg body weight) and the EDL muscle was removed from the other leg 10 min post–insulin injection to allow sufficient time for insulin signaling to occur (24–27). Immediately following tissue removal, muscle samples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C for subsequent analysis. The epididymal fat pad was removed and weighed. All 24 rats were killed by exsanguination. Whole blood was centrifuged in separation tubes at 4,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C and the resultant serum was stored at −80°C.

TABLE 1.

Composition of the casein- and whole egg–based diet fed to lean control and ZDF rats for 7 wk1

| Ingredient, g/kg | Casein | Whole egg |

|---|---|---|

| Casein (vitamin free) | 200 | 0 |

| Dried whole egg | 0 | 413 |

| Corn starch | 423 | 387 |

| Glucose monohydrate | 150 | 150 |

| Mineral mix (AIN 93) | 35 | 35 |

| Vitamin mix (AIN 93) | 10 | 10 |

| Biotin 1% | 0 | 0.4 |

| Corn oil | 177 | 0 |

| Choline bitartrate | 2 | 2 |

| l-Methionine | 3 | 3 |

| Macronutrients, kcal/kg | ||

| Protein | 800 | 800 |

| Lipid | 1593 | 1593 |

| Carbohydrate | 2292 | 2148 |

| Total energy | 4685 | 4541 |

All ingredients were purchased from Envigo with the exception of dried whole egg (Rose Acre Farms) as well as l-methionine and choline bitartrate (Sigma-Aldrich). ZDF, Zucker diabetic fatty.

The total protein and lipid content provided by 413 g of dried whole egg was 48.4% (200 g) and 42.9% (177 g), respectively.

Insulin tolerance tests

Insulin tolerance tests (ITTs) were performed at week 5 of experimental dietary treatment. Rats were fasted for a period of 4 h prior to insulin tolerance testing and given an intraperitoneal insulin injection (0.5 U/kg body weight). Blood samples were collected from the tail vein immediately prior to the insulin challenge, as well as 15, 30, 45, and 60 min thereafter. Blood sampling was performed by making a nick with a sterilized razor blade toward the end of the tail and blood glucose was measured with the use of a glucometer (Bayer Healthcare). When blood glucose was above the detection limit (600 mg/dL), the maximum value of 600 mg/dL was used.

Serum glucose and serum insulin

Serum collected on the final day of the study was used for analysis of fasting glucose, fasting insulin, and calculation of HOMA-IR. Serum glucose was measured with the use of a commercially available colorimetric kit (Wako Diagnostics). Analysis of serum insulin was measured by a commercially available immunoassay kit for the detection of insulin in rat sera (EMD Millipore).

Western blot analysis

EDL muscles were homogenized in 800 μL of lysis buffer [Tris-hydrochloric acid (pH 7.8, 50 mM), EDTA (1 mM), EGTA (1 mM), glycerol (10%, wt/vol), Triton-X 100 (1%, wt/vvol), dithiothreitol (1 mM)] containing phosphatase (Sigma) and protease (Thermo Scientific) inhibitors. Samples were then centrifuged at 4000 × g for 15 min at 4°C and the supernatant was collected. Protein concentrations were determined via a bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A total of 20 μg protein was loaded and run on a 4–15% gradient sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad). Following separation, proteins were transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (EMD Millipore) and blocked at room temperature for 1 h in Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween and 5% nonfat dry milk. Membranes were incubated in phosphorylated (p)-IGFI Receptor βTyr1135/1136/Insulin Receptor βTyr1150/1151, p-AktSer473, Akt, and p-AS160Thr642 antibodies (Cell Signaling) at 1:1000 overnight at 4°C. Following incubation with primary antibody, membranes were washed and incubated with an antirabbit secondary antibody (Cell Signaling) at 1:5000 for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were incubated in enhanced chemiluminescent substrate (SuperSignal West Pico PLUS Sensitivity Substrate or SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate; Thermo Scientific) for 5 min prior to imaging with the ChemiDoc XRS detection imaging system (Bio-Rad). Densitometry was determined with the use of Image Lab software (BioRad) and raw data was normalized to total protein.

Statistical analysis

All data were evaluated for statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) with the use of SPSS Statistics Software version 23 (IBM). Body and epididymal fat pad weights, food intake, and serum parameters were analyzed with the use of a 2-factor ANOVA (diet × genotype). An analysis of main effects was performed when the interaction between diet and genotype was not statistically significant. Insulin tolerance test data was analyzed by a 3-factor, repeated-measures ANOVA (time × diet × genotype) and statistically significant 2-factor interactions were followed by an analysis of simple main effects. Western blot data was analyzed with the use of a 3-factor mixed ANOVA to determine the effects of insulin, diet, and genotype on insulin signaling. All pairwise comparisons were performed with the use of Fisher's least significant difference post-hoc test.

Results

Body and relative adipose tissue weights

As expected, there was a significant main effect of genotype on initial and final body weight. ZDF rats had a higher mean initial body weight than their lean counterparts, and body weight was 13% higher in ZDF rats than in lean rats on the final day of the study. Diet was without effect on final body weight in both lean and ZDF rats (Table 2). Likewise, there was a significant main effect of genotype on relative adipose tissue weight [epididymal fat pad weight (g/100 g body weight)]. The ZDF genotype was associated with a 74% higher mean relative adipose tissue weight than the lean genotype. No significant differences in relative adipose tissue weight were observed across diets within lean or ZDF rats (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Body and adipose tissue weights and total food intake of lean and ZDF rats fed a casein- or whole egg–based diet for 7 wk1

| Lean | ZDF | P | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casein | Whole egg | Casein | Whole egg | Genotype | Diet | Genotype × diet | |

| Initial body weight,2 g | 157 ± 5a | 155 ± 6a | 191 ± 6b | 191 ± 4b | <0.001 | 0.877 | 0.824 |

| Final body weight,2 g | 329 ± 7a | 334 ± 5a | 378 ± 4b | 371 ± 8b | <0.001 | 0.897 | 0.368 |

| Epididymal fat pad weight,2 g/100 g body weight | 0.47 ± 0.04a | 0.50 ± 0.08a | 0.86 ± 0.08b | 0.83 ± 0.03b | <0.001 | 0.992 | 0.642 |

| Total food intake,3 g | 990 ± 28a | 930 ± 29a | 1843 ± 135b | 1732 ± 163b | <0.001 | 0.449 | 0.818 |

| Total energy intake,3 kcal | 4639 ± 130a | 4224 ± 132a | 8636 ± 632b | 7865 ± 740b | <0.001 | 0.265 | 0.729 |

ZDF, Zucker diabetic fatty.

Data are means ± SEMs; n = 6. Data within the same row without a common letter differ (P < 0.05).

Data are means ± SEMs; n = 3. Total food intake per cage (2 rats/cage). Data within the same row without a common letter differ (P < 0.05).

Food intake

Main effects analysis indicated a significant effect of genotype on food intake and total energy intake. ZDF rats exhibited an 86% higher mean total food intake than lean rats (Table 2). Likewise, total energy intake was 86% higher in ZDF rats than in lean rats (Table 2). There was no effect of diet on total food intake or total energy intake.

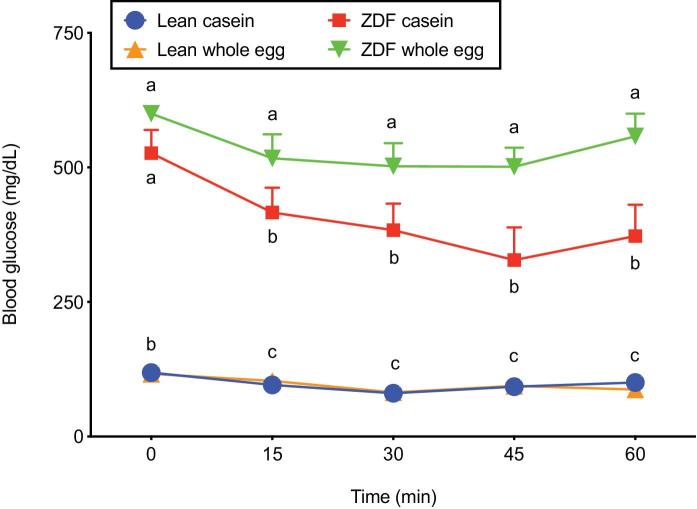

ITT

Analysis of ITT blood glucose concentrations revealed a significant effect of time on circulating glucose concentrations, demonstrating that insulin effectively lowered blood glucose. There was also a significant effect of genotype and diet, as well as significant diet × genotype and time × genotype 2-factor interactions. As expected, there was a simple main effect of genotype (P < 0.001) on blood glucose, indicating markedly higher blood glucose in ZDF rats than in lean rats at each time point (Figure 1). A simple main effect of time was also observed in the ZDF genotype (P = 0.001), but not in the lean genotype (P = 0.836). Lastly, a simple main effect of diet was observed in the ZDF genotype (P < 0.001), but not in the lean genotype (P = 0.987). With the exception of baseline blood glucose, ZDF rats fed the whole egg-based diet exhibited ∼38% higher blood glucose concentrations from the 15–60 min time points than ZDF rats fed the casein-based diet. In contrast, blood glucose did not differ between dietary treatment groups in lean rats at any of the time points (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

ITT blood glucose in lean and ZDF rats fed a casein- or whole egg–based diet for 5 wk. Data are means ± SEMs; n = 3–6. Data within the same time point without a common letter differ (P < 0.05). Three-factor repeated-measures ANOVA: time, P < 0.001; diet, P = 0.027; genotype, P < 0.001; time × diet, P = 0.662; time × genotype P = 0.031; diet × genotype P = 0.025; Time × diet × genotype, P = 0.572. ITT, insulin tolerance test; ZDF, Zucker diabetic fatty.

Serum glucose, serum insulin, HOMA-IR, and homeostatic model assessment of β-cell function

There was a significant main effect of genotype on serum glucose, serum insulin, and the HOMA-IR. As expected, mean serum glucose, serum insulin, and HOMA-IR values were 244%, 629%, and 234% higher, respectively, in the ZDF genotype than in the lean genotype (Table 3). Diet was without effect on serum glucose concentrations within the lean genotype; however, serum glucose concentrations were increased by 35% in ZDF rats fed the whole egg–based diet than in ZDF rats fed the casein-based diet (Table 3). No differences in serum insulin concentrations were observed across dietary groups within the lean genotype, whereas serum insulin was 68% higher in ZDF rats fed the casein-based diet than in ZDF rats fed the whole egg–based diet. There was no effect of diet on the HOMA-IR within the lean or ZDF genotype (Table 3). Lastly, there was a significant main effect of diet on the homeostatic model assessment of β-cell function (HOMA-β). The whole egg–based diet was associated with a mean decrease of 44% in HOMA-β compared with the casein-based diet (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Fasting serum glucose, fasting serum insulin, HOMA-IR and HOMA-β of lean and ZDF rats fed a casein- or whole egg–based diet for 7 wk1

| Lean | ZDF | P | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casein | Whole egg | Casein | Whole egg | Genotype | Diet | Genotype × diet | |

| Serum glucose, mg/dL | 124 ± 13c | 189 ± 19c | 457 ± 31b | 618 ± 86a | <0.001 | 0.026 | 0.317 |

| Serum Insulin, ng/mL | 0.3 ± 0.1c | 0.4 ± 0.1c | 3.2 ± 0.4a | 1.9 ± 0.6b | <0.001 | 0.116 | 0.078 |

| HOMA-IR | 2.1 ± 0.46b | 4.0 ± 1.2b | 82 ± 9.3a | 59 ± 20a | <0.001 | 0.344 | 0.267 |

| HOMA-β, % | 51 ± 13a,b | 32 ± 13b | 72 ± 13a | 37 ± 12a,b | 0.331 | 0.046 | 0.554 |

Data are means ± SEMs; n = 6. Data within the same row without a common letter differ (P < 0.05). HOMA-β, HOMA-β, homeostatic model assessment of β-cell function; ZDF, Zucker diabetic fatty.

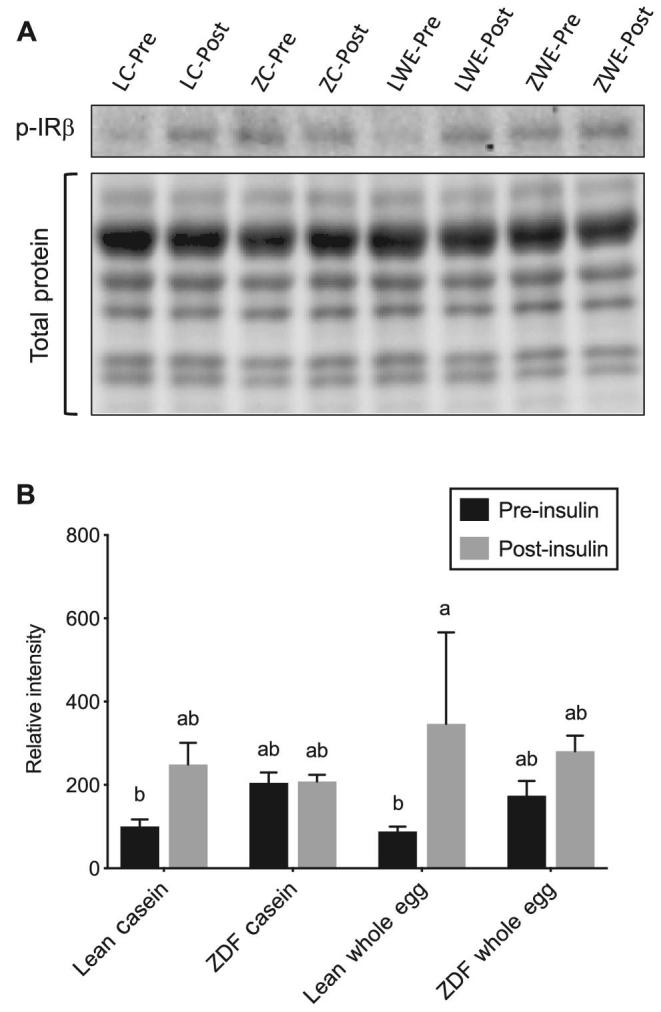

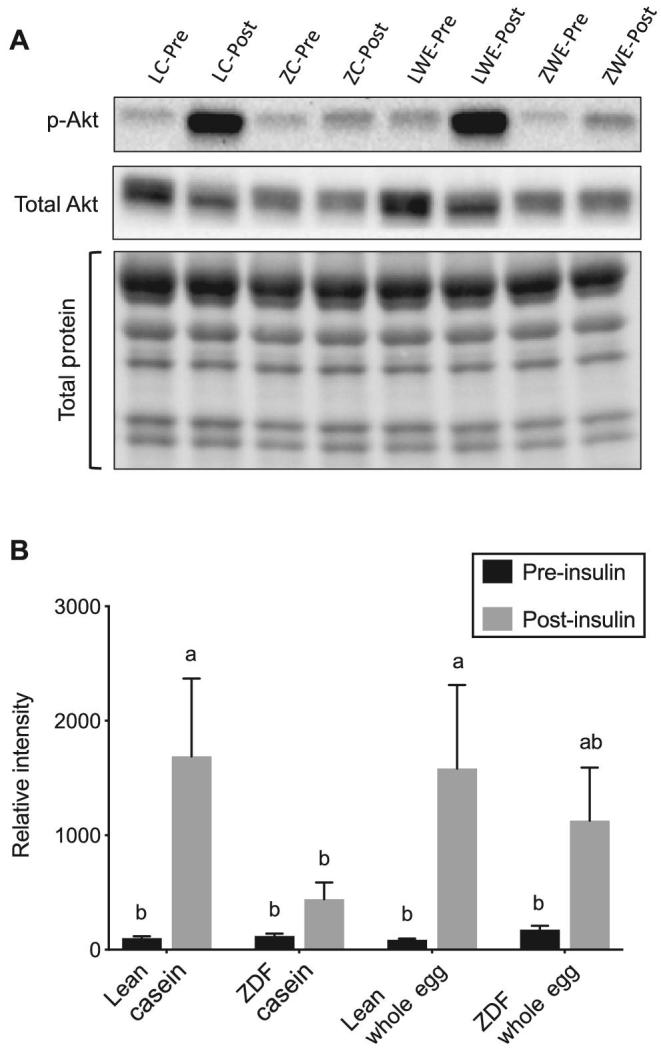

Insulin signaling pathway

Insulin increased phosphorylation of the IR βTyr1150/1151 by 291% in lean rats fed the whole egg–based diet compared with IR βTyr1150/1151 phosphorylation prior to insulin (Figure 2); however, post-insulin IR βTyr1150/1151 phosphorylation did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.215) in lean casein-fed rats compared with pre-insulin phosphorylated insulin receptor (p-IR) βTyr1150/1151. No differences in p-IR βTyr1150/1151 were observed pre- or post-insulin in ZDF rats, regardless of dietary treatment (Figure 2). In lean rats fed the casein- and whole egg–based diets, the post-insulin ratio of p-AktSer473:total Akt was increased 17-fold and 18-fold, respectively, compared with the pre-insulin ratio (Figure 3). Pre- and post-insulin p-AktSer473:total Akt did not differ in ZDF rats, regardless of dietary treatment. However, in ZDF rats fed the whole egg–based diet, the post-insulin p-AktSer473:total Akt ratio did not statistically differ from the lean genotype (Figure 3). No differences in post-insulin p-AS160Thr642 were observed, regardless of diet or genotype (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

Skeletal muscle p-IR βTyr1150/1151 (A) and representative Western blot images of skeletal muscle p-IR βTyr1150/1151 and total protein (B) pre- and post-insulin injection in lean and ZDF rats fed a casein- or whole egg–based diet for 7 wk. Data are expressed relative to pre-insulin p-IR βTyr1150/1151 in lean rats fed the casein-based diet. Data are means ± SEMs; n = 5–6. Bars without a common letter differ (P < 0.05). Three-factor mixed ANOVA: insulin, P = 0.029; diet, P = 0.492; genotype, P = 0.874; insulin × diet, P = 0.297; insulin × genotype P = 0.169; diet × genotype P = 0.723; insulin × diet × genotype, P = 837. LC-Pre, lean casein pre-insulin; LC-Post, lean casein post-insulin; ZC-Pre, ZDF casein pre-insulin; ZC-Post, ZDF casein post-insulin; LWE-Pre, lean whole egg pre-insulin; LWE-Post, lean whole egg post-insulin; ZWE-Pre, ZDF whole egg pre-insulin; ZWE-Post, ZDF whole egg post-insulin. p-IR, phosphorylated insulin receptor; ZDF, Zucker diabetic fatty.

FIGURE 3.

The ratio of skeletal muscle p-AktSer473:total Akt (A) and representative Western blot images of skeletal muscle p-AktSer473, total Akt, and total protein (B) pre- and post-insulin injection in lean and ZDF rats fed a casein- or whole egg–based diet for 7 wk. Data are expressed relative to the pre-insulin p-AktSer473:total Akt ratio in lean rats fed the casein-based diet. Data are means ± SEMs; n = 5–6. Bars without a common letter differ (P < 0.05). Three-factor mixed ANOVA: insulin, P < 0.001; diet, P = 0.53; genotype, P = 0.157; insulin × diet, P = 0.571; insulin × genotype P = 0.11; diet × genotype P = 0.535; insulin × diet × genotype, P = 0.609. LC-Pre, lean casein pre-insulin; LC-Post, lean casein post-insulin; ZC-Pre, ZDF casein pre-insulin; ZC-Post, ZDF casein post-insulin; LWE-Pre, lean whole egg pre-insulin; LWE-Post, lean whole egg post-insulin; ZWE-Pre, ZDF whole egg pre-insulin; ZWE-Post, ZDF whole egg post-insulin. p-Akt, phosphorylated Akt; ZDF, Zucker diabetic fatty.

Discussion

The relation between egg consumption and T2D remains contradictory and evidence is limited regarding potential mechanisms that may explain the reported associations between dietary egg intake, glycemic control, and incident diabetes. The present study aimed to examine the effects of egg consumption on insulin tolerance and insulin signaling in vivo through the use of a rat model of obesity and T2D. Although egg consumption impaired glycemic control in ZDF rats during an ITT, no differences were observed in skeletal muscle insulin signaling between ZDF rats fed casein- and whole egg–based diets. Although skeletal muscle is the primary site of insulin-stimulated glucose disposal, glucose metabolism by the liver and adipose tissue also contributes to whole body glucose homeostasis (28–30). The relative contribution of these tissues to systemic glucose metabolism, as well as differences in timing between insulin tolerance testing and skeletal muscle collection for insulin signaling analysis, may explain the differential results observed between whole body insulin tolerance and skeletal muscle insulin signaling.

Very few studies have investigated the effect of egg consumption on direct measures of insulin sensitivity (22). In the present study, we report higher blood glucose during an ITT in ZDF rats consuming a whole egg–based diet than in ZDF rats fed a casein-based diet. In support of this finding, egg consumption was inversely associated with insulin sensitivity and the metabolic clearance rate of insulin in a cross-sectional analysis of a nondiabetic population, although these associations became insignificant after adjustment for BMI and dietary cholesterol (22). Likewise, Djousse et al. (13) reported an increase in fasting blood glucose and insulin resistance, as measured by HOMA-IR, across varying amounts of egg consumption in a prospective cohort of older adults. However, the authors noted that the magnitude of difference, although statistically significant, was not likely to be of clinical significance (13). Here, we report higher fasting blood glucose in ZDF rats after 7 wk of dietary treatment with the whole egg–based diet, but no differences in HOMA-IR, a model used to quantify insulin resistance, between ZDF rats fed casein- and whole egg–based diets.

In the early stages of insulin resistance, enhanced pancreatic insulin secretion attempts to compensate for reduced responsiveness to insulin in peripheral tissues as a means to maintain normal glucose tolerance. A physiologic approach to accomplish this goal is by enhanced β-cell mass and activity (31, 32). As insulin resistance progresses, compensatory hyperinsulinemia is unable to maintain normal blood glucose concentrations. Insulin secretion is continuously stimulated by hyperglycemia, and β-cell structure and function becomes compromised, ultimately leading to apoptosis (32). In ZDF rats, β-cell mass decreases between 6 and 12 wk of age, and is significantly reduced at 12 wk (33–35). The observed loss of β-cell mass has been attributed an increase in cell death (33, 34). β-cell dysfunction in ZDF rats is accompanied by a progressive decline in circulating insulin concentrations, beginning at 7 wk of age (33, 35). We report significantly lower serum insulin, concomitant with higher serum glucose, in ZDF rats fed the whole egg–based diet compared with ZDF rats fed the casein-based diet after 7 wk of dietary treatment (13 wk of age). Additionally, consumption of a whole egg–based diet was associated with decreased HOMA-β, an index of β-cell function, suggesting impaired insulin production and secretion in rats fed the whole egg–based diet. It is possible that ZDF rats fed the whole egg–based diet exhibit a higher rate of decline in β-cell function, potentially explaining these differences. In cultured β-cells, cholesterol accumulation results in apoptosis and impaired glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (36–39). The cholesterol content of whole egg may play a role in the observed reduction in serum insulin; however, whether whole egg consumption affects β-cell function in ZDF rats remains to be determined.

Aberrant insulin signaling in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue impairs insulin-mediated translocation of GLUT4 and subsequent glucose uptake. To our knowledge, there are no previous studies examining the effect of egg consumption on insulin signaling. In the present study, phosphorylation of IR βTyr1150/1151 was not significantly increased in ZDF rats following an insulin injection, regardless of experimental dietary treatment. This result is consistent with findings from numerous human studies, which show reduced tyrosine phosphorylation of the insulin receptor and its subsequent kinase activity in states of insulin resistance (40–45). The serine/threonine kinase Akt is activated by insulin-stimulated phosphorylation at both Thr308 and Ser473 and plays a key role in the regulation of glucose uptake into insulin-responsive tissues (46). As expected, we report a marked increase in the ratio of p-AktSer473:total Akt in lean rats in response to insulin. Conversely, the p-AktSer473:total Akt ratio was not significantly increased by insulin in ZDF rats fed both casein- and whole egg–based diets. In agreement with this finding, several studies report defective Akt phosphorylation and kinase activity in insulin-resistant subjects compared with lean controls (47–51). Phosphorylation of AS160, a downstream substrate of Akt, links insulin signaling to GLUT4 translocation and impaired insulin-stimulated AS160 phosphorylation has been reported in the skeletal muscle of diabetic human subjects (51, 52). In contrast to these findings, we did not observe differences in post-insulin p-AS160Thr642 between lean and ZDF rats, regardless of dietary treatment group.

Eggs are a source of high-quality protein, and several human studies report an association between egg consumption, increased satiety, and reduced caloric intake (53–56). Egg consumption has also been shown to promote weight loss in a limited number of human studies (57, 58). In contrast to our previous findings (20, 21), we did not observe a reduction in body weight gain in ZDF rats fed a whole egg–based diet. Moreover, relative adipose tissue weight not differ between ZDF rats, regardless of dietary treatment. It is well documented that weight loss is a highly effective strategy to improve insulin sensitivity and glycemia, both in the prevention and treatment of T2D (59, 60). Furthermore, numerous human studies report improved glycemic control in type 2 diabetics following adherence to low-carbohydrate, low-glycemic index, and high-protein diets (61, 62). Indeed, beneficial impacts of egg consumption on blood glucose control have been shown in human subjects when combined with energy or carbohydrate restriction (12, 23, 63, 64). For example, Pearce et al. (12) reported improvements in glycemic and lipid profiles in type 2 diabetics following consumption of a hypoenergetic, high-protein diet containing 2 eggs/d. In individuals with metabolic syndrome, Blesso et al. (23) found a reduction in HOMA-IR following consumption of a carbohydrate-restricted diet including 3 eggs/d. In the current study, rodent diets were matched for macronutrient content and there were no differences in final body weight between ZDF rats fed casein- and whole egg–based diets. Taken together, these findings suggest that reported improvements in glycemic control associated with egg consumption may be related to changes in dietary macronutrient content or improved body weight management, and not a direct effect of egg consumption on skeletal muscle insulin signaling.

A limitation of this study is the quantity of dried whole egg used in the whole egg–based diet, which exceeds the amount of whole egg that would typically be consumed in a human diet. The quantity of dried whole egg was determined such that the casein- and whole egg–based diets were matched for protein content. Additionally, analysis of β-cell mass and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion would provide insight into whether β-cell function declines more rapidly in ZDF rats fed the whole egg–based diet. Lastly, insulin signaling was only analyzed in the EDL muscle. The EDL is frequently used in analysis of skeletal muscle insulin signaling (7, 65–68). However, it is possible that sensitivity for phosphoregulation by insulin may differ in other muscle groups. Future studies will include analysis of skeletal muscle groups composed of different fiber types, as well as additional tissues, to provide a more comprehensive examination of insulin signaling.

In summary, these data suggest that whole egg consumption may impair insulin sensitivity in T2D rats. Although consumption of a whole egg–based diet adversely affected whole body insulin sensitivity in ZDF rats, we were unable to identify changes in skeletal muscle insulin signaling that could explain this finding. Future studies investigating the impact of whole egg consumption on β-cell function may offer a potential explanation for the reduction in fasting serum insulin in ZDF rats fed a whole egg–based diet. Furthermore, dose-response studies are warranted to determine whether the observed impairment in insulin sensitivity is maintained at a lower dose of whole egg.

Acknowledgments

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows: CJS: designed the study and performed all aspects of animal maintenance, preparation of experimental diets, insulin tolerance testing and laboratory experiments, and drafted the original version of this manuscript; MAS: assisted in animal maintenance and preparation of experimental diets; JLW assisted with insulin tolerance testing; RJV, MJR, and KLS: assisted with the study design; and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Notes

Supported by the Egg Nutrition Center, Park Ridge, IL and by the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Experiment Station, Iowa State University, Ames, IA 50011. CJS was supported by a USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture National Needs Graduate Fellowship Program.

Author disclosures: CJS, MAS, JLW, RJV, MJR, and KLS, no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations used: AS160, Akt substrate 160; EDL, extensor digitorum longus; GLUT4, glucose transporter type 4; HOMA-β, homeostatic model assessment of β-cell function; IR, insulin receptor; IRS-1, insulin receptor substrate 1; ITT, insulin tolerance test; p-, phosphorylated; ZDF, Zucker diabetic fatty.

References

- 1. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Prediabetes and insulin resistance [Internet]. National Institutes of Health; 2014. Available from: [cited October 24, 2018]. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kahn SE, Hull RL, Utzschneider KM. Mechanisms linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature 2006;444:840–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ye J. Mechanisms of insulin resistance in obesity. Front Med 2013;1:14–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Guo S. Insulin signaling, resistance, and the metabolic syndrome: insights from mouse models into disease mechanisms. J Endocrinol 2014;220:T1–t23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boucher J, Kleinridders A, Kahn CR. Insulin receptor signaling in normal and insulin-resistant states. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2014;6:a009191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Copps KD, White MF.. Regulation of insulin sensitivity by serine/threonine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate proteins IRS1 and IRS2. Diabetologia 2012;55:2565–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kramer HF, Witczak CA, Fujii N, Jessen N, Taylor EB, Arnolds DE, Sakamoto K, Hirshman MF, Goodyear LJ. Distinct signals regulate AS160 phosphorylation in response to insulin, AICAR, and contraction in mouse skeletal muscle. Diabetes 2006;55:2067–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hojlund K. Metabolism and insulin signaling in common metabolic disorders and inherited insulin resistance. Dan Med J 2014;61:B4890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Djousse L, Gaziano JM, Buring JE, Lee I-M. Egg consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in men and women. Diabetes Care 2009;32:295–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shi Z, Yuan B, Zhang C, Zhou M, Holmboe-Ottesen G. Egg consumption and the risk of diabetes in adults, Jiangsu, China. Nutrition 2011;27:194–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Radzeviciene L, Ostrauskas R.. Egg consumption and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a case-control study. Public Health Nutr 2012;15:1437–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pearce KL, Clifton PM, Noakes M. Egg consumption as part of an energy-restricted high-protein diet improves blood lipid and blood glucose profiles in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Br J Nutr 2011;105:584–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Djousse L, Kamineni A, Nelson TL, Carnethon M, Mozaffarian D, Siscovick D, Mukamal KJ. Egg consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in older adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;92:422–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Virtanen JK, Mursu J, Tuomainen T-P, Virtanen HE, Voutilainen S. Egg consumption and risk of incident type 2 diabetes in men: the Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2015;101:1088–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zazpe I, Beunza JJ, Bes-Rastrollo M, Basterra-Gortari FJ, Mari-Sanchis A, Martinez-Gonzalez MA. Egg consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in a Mediterranean cohort; the sun project. Nutr Hosp 2013;28:105–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pourafshar S, Akhavan NS, George KS, Foley EM, Johnson SA, Keshavarz B, Navaei N, Davoudi A, Clark EA, Arjmandi BH. Egg consumption may improve factors associated with glycemic control and insulin sensitivity in adults with pre- and type II diabetes. Food Funct 2018;9:4469–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Njike VY, Ayettey RG, Rajebi H, Treu JA, Katz DL. Egg ingestion in adults with type 2 diabetes: effects on glycemic control, anthropometry, and diet quality-a randomized, controlled, crossover trial. BMJ Open Diabetes Res care 2016;4:e000281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Djousse L, Khawaja OA, Gaziano JM. Egg consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr 2016;103:474–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sabaté J, Burkholder-Cooley NM, Segovia-Siapco G, Oda K, Wells B, Orlich MJ, Fraser GE. Unscrambling the relations of egg and meat consumption with type 2 diabetes risk. Am J Clin Nutr 2018;108(5):1121–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Saande CJ, Jones SK, Hahn KE, Reed CH, Rowling MJ, Schalinske KL. Dietary whole egg consumption attenuates body weight gain and is more effective than supplemental cholecalciferol in maintaining vitamin D balance in type 2 diabetic rats. J Nutr 2017;147(9):1715–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jones SK, Rowling MJ, Schalinske KL. Whole egg consumption prevents diminished serum 25-hydroxycholecalciferol concentrations in type 2 diabetic rats. J Agric Food Chem 2016;64:120–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee C-TC, Liese AD, Lorenzo C, Wagenknecht LE, Haffner SM, Rewers MJ, Hanley AJ. Egg consumption and insulin metabolism in the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS). Public Health Nutr 2014;17:1595–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Blesso CN, Andersen CJ, Barona J, Volek JS, Fernandez ML. Whole egg consumption improves lipoprotein profiles and insulin sensitivity to a greater extent than yolk-free egg substitute in individuals with metabolic syndrome. Metabolism 2013;62:400–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ritchie IRW, Wright DC, Dyck DJ. Adiponectin is not required for exercise training-induced improvements in glucose and insulin tolerance in mice. Physiol Rep 2014;2:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kim YB, Uotani S, Pierroz DD, Flier JS, Kahn BB. In vivo administration of leptin activates signal transduction directly in insulin-sensitive tissues: overlapping but distinct pathways from insulin. Endocrinology 2000;141:2328–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Giorgino F, Almahfouz A, Goodyear LJ, Smith RJ. Glucocorticoid regulation of insulin receptor and substrate IRS-1 tyrosine phosphorylation in rat skeletal muscle in vivo. J Clin Invest 1993;91:2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kim YB, Peroni OD, Franke TF, Kahn BB. Divergent regulation of Akt1 and Akt2 isoforms in insulin target tissues of obese Zucker rats. Diabetes 2000;49:847–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. DeFronzo RA, Jacot E, Jequier E, Maeder E, Wahren J, Felber JP. The effect of insulin on the disposal of intravenous glucose. Results from indirect calorimetry and hepatic and femoral venous catheterization. Diabetes 1981;30:1000–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. DeFronzo RA, Tripathy D.. Skeletal muscle insulin resistance is the primary defect in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009;32(Suppl 2):S157–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. DeFronzo RA, Simonson D, Ferrannini E. Hepatic and peripheral insulin resistance: a common feature of type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) and type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1982;23:313–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kargar C, Ktorza A.. Anatomical versus functional beta-cell mass in experimental diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2008;10(Suppl 4):43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Khodabandehloo H, Gorgani-Firuzjaee S, Panahi G, Meshkani R. Molecular and cellular mechanisms linking inflammation to insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction. Transl Res 2016;167:228–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Finegood DT, McArthur MD, Kojwang D, Thomas MJ, Topp BG, Leonard T, Buckingham RE. Beta-cell mass dynamics in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Rosiglitazone prevents the rise in net cell death. Diabetes 2001;50:1021–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pick A, Clark J, Kubstrup C, Levisetti M, Pugh W, Bonner-Weir S, Polonsky KS. Role of apoptosis in failure of beta-cell mass compensation for insulin resistance and beta-cell defects in the male Zucker diabetic fatty rat. Diabetes 1998;47:358–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Topp BG, Atkinson LL, Finegood DT. Dynamics of insulin sensitivity, -cell function, and -cell mass during the development of diabetes in fa/fa rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2007;293:E1730–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hao M, Head WS, Gunawardana SC, Hasty AH, Piston DW. Direct effect of cholesterol on insulin secretion: a novel mechanism for pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction. Diabetes 2007;56:2328–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Paul R, Choudhury A, Choudhury S, Mazumder MK, Borah A. Cholesterol in pancreatic beta-cell death and dysfunction: underlying mechanisms and pathological implications. Pancreas 2016;45:317–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fryirs M, Barter PJ, Rye K-A. Cholesterol metabolism and pancreatic beta-cell function. Curr Opin Lipidol 2009;20:159–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bogan JS, Xu Y, Hao M. Cholesterol accumulation increases insulin granule size and impairs membrane trafficking. Traffic 2012;13:1466–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Goodyear LJ, Giorgino F, Sherman LA, Carey J, Smith RJ, Dohm GL. Insulin receptor phosphorylation, insulin receptor substrate-1 phosphorylation, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity are decreased in intact skeletal muscle strips from obese subjects. J Clin Invest 1995;95:2195–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Friedman JE, Ishizuka T, Liu S, Farrell CJ, Bedol D, Koletsky RJ, Kaung HL, Ernsberger P. Reduced insulin receptor signaling in the obese spontaneously hypertensive Koletsky rat. Am J Physiol 1997;273:E1014–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Caro JF, Sinha MK, Raju SM, Ittoop O, Pories WJ, Flickinger EG, Meelheim D, Dohm GL. Insulin receptor kinase in human skeletal muscle from obese subjects with and without noninsulin dependent diabetes. J Clin Invest 1987;79:1330–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Friedman JE, Ishizuka T, Shao J, Huston L, Highman T, Catalano P. Impaired glucose transport and insulin receptor tyrosine phosphorylation in skeletal muscle from obese women with gestational diabetes. Diabetes 1999;48:1807–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Thies RS, Molina JM, Ciaraldi TP, Freidenberg GR, Olefsky JM. Insulin-receptor autophosphorylation and endogenous substrate phosphorylation in human adipocytes from control, obese, and NIDDM subjects. Diabetes 1990;39:250–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nolan JJ, Freidenberg G, Henry R, Reichart D, Olefsky JM. Role of human skeletal muscle insulin receptor kinase in the in vivo insulin resistance of noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1994;78:471–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Alessi DR, Andjelkovic M, Caudwell B, Cron P, Morrice N, Cohen P, Hemmings BA. Mechanism of activation of protein kinase B by insulin and IGF-1. EMBO J 1996;15:6541–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Brozinick JTJ, Roberts BR, Dohm GL. Defective signaling through Akt-2 and -3 but not Akt-1 in insulin-resistant human skeletal muscle: potential role in insulin resistance. Diabetes 2003;52:935–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Krook A, Roth RA, Jiang XJ, Zierath JR, Wallberg-Henriksson H. Insulin-stimulated Akt kinase activity is reduced in skeletal muscle from NIDDM subjects. Diabetes 1998;47:1281–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Casaubon L, Sajan MP, Rivas J, Powe JL, Standaert ML, Farese RV. Contrasting insulin dose-dependent defects in activation of atypical protein kinase C and protein kinase B/Akt in muscles of obese diabetic humans. Diabetologia 2006;49:3000–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chen MZ, Hudson CA, Vincent EE, de Berker DAR, May MT, Hers I, Dayan CM, Andrews RC, Tavare JM. Bariatric surgery in morbidly obese insulin resistant humans normalises insulin signalling but not insulin-stimulated glucose disposal. PLoS One 2015;10:e0120084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Karlsson HKR, Zierath JR, Kane S, Krook A, Lienhard GE, Wallberg-Henriksson H. Insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of the Akt substrate AS160 is impaired in skeletal muscle of type 2 diabetic subjects. Diabetes 2005;54:1692–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Middelbeek RJW, Chambers MA, Tantiwong P, Treebak JT, An D, Hirshman MF, Musi N, Goodyear LJ. Insulin stimulation regulates AS160 and TBC1D1 phosphorylation sites in human skeletal muscle. Nutr Diabetes 2013;3:e74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kral TVE, Bannon AL, Chittams J, Moore RH. Comparison of the satiating properties of egg- versus cereal grain-based breakfasts for appetite and energy intake control in children. Eat Behav 2016;20:14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ratliff J, Leite JO, de Ogburn R, Puglisi MJ, VanHeest J, Fernandez ML. Consuming eggs for breakfast influences plasma glucose and ghrelin, while reducing energy intake during the next 24 hours in adult men. Nutr Res 2010;30:96–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Vander Wal JS, Marth JM, Khosla P, Jen K-LC, Dhurandhar NV. Short-term effect of eggs on satiety in overweight and obese subjects. J Am Coll Nutr 2005;24:510–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pombo-Rodrigues S, Calame W, Re R. The effects of consuming eggs for lunch on satiety and subsequent food intake. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2011;62:593–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wang S, Yang L, Lu J, Mu Y. High-protein breakfast promotes weight loss by suppressing subsequent food intake and regulating appetite hormones in obese Chinese adolescents. Horm Res Paediatr 2015;83:19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Vander Wal JS, Gupta A, Khosla P, Dhurandhar NV. Egg breakfast enhances weight loss. Int J Obes 2008;32:1545–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Grams J, Garvey WT.. Weight loss and the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes using lifestyle therapy, pharmacotherapy, and bariatric surgery: mechanisms of action. Curr Obes Rep 2015;4:287–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gummesson A, Nyman E, Knutsson M, Karpefors M. Effect of weight reduction on glycated haemoglobin in weight loss trials in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2017;19:1295–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ajala O, English P, Pinkney J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of different dietary approaches to the management of type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;97:505–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Meng Y, Bai H, Wang S, Li Z, Wang Q, Chen L. Efficacy of low carbohydrate diet for type 2 diabetes mellitus management: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2017;131:124–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Maki KC, Palacios OM, Lindner E, Nieman KM, Bell M, Sorce J. Replacement of refined starches and added sugars with egg protein and unsaturated fats increases insulin sensitivity and lowers triglycerides in overweight or obese adults with elevated triglycerides. J Nutr 2017;147:1267–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ratliff J, Mutungi G, Puglisi MJ, Volek JS, Fernandez ML. Carbohydrate restriction (with or without additional dietary cholesterol provided by eggs) reduces insulin resistance and plasma leptin without modifying appetite hormones in adult men. Nutr Res 2009;29:262–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. McCurdy CE, Cartee GD.. Akt2 is essential for the full effect of calorie restriction on insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in skeletal muscle. Diabetes 2005;54:1349–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Dumke CL, Wetter AC, Arias EB, Kahn CR, Cartee GD. Absence of insulin receptor substrate-1 expression does not alter GLUT1 or GLUT4 abundance or contraction-stimulated glucose uptake by mouse skeletal muscle. Horm Metab Res 2001;33:696–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Gazdag AC, Dumke CL, Kahn CR, Cartee GD. Calorie restriction increases insulin-stimulated glucose transport in skeletal muscle from IRS-1 knockout mice. Diabetes 1999;48:1930–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Taylor EB, An D, Kramer HF, Yu H, Fujii NL, Roeckl KSC, Bowles N, Hirshman MF, Xie J, Feener EP et al.. Discovery of TBC1D1 as an insulin-, AICAR-, and contraction-stimulated signaling nexus in mouse skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem 2008;283:9787–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]