Abstract

Research on rural health needs to represent the diverse demographics of these regions by carefully considering the distinct characteristics, inequities, and stressors occurring in rural communities. Drawing from our own findings and other empirical investigations examining diverse rural communities, we propose several considerations to guide future endeavors toward more inclusive rural health research. These include population-health assessment tools that consider minority stress and intervention strategies designed to reflect both the environmental and socio-cultural contexts of rural residents.

Disparities in morbidity and mortality between urban and rural residents are well-documented and have been referred to as the “rural mortality penalty.” (Cosby et al., 2008) Rural residents have not seen the same health improvements as their urban counterparts, and population trends indicate that the disparity is large and growing (Cosby et al., 2019). Rural communities have higher burdens of preventable conditions such as obesity, diabetes, cancer, and injury compared to urban populations and are more likely to engage in risky behaviors such as substance use and smoking. Rural residents also exhibit lower levels of physical activity and consume lower nutrient and more calorically dense diets (Eberhardt & Pamuk, 2004; Hartley, 2004). Whether from their physical environment, socioeconomic status, or additional social factors, rural residents are at increased risk of poor health outcomes and higher mortality. Notable among these trends are increases in suicides and unintentional injuries, including opioid overdoses (Case & Deaton, 2015; Stein, Gennuso, Ugboaja, & Remington, 2017).

In order to achieve a fuller understanding of health risk factors for rural communities, more research efforts need to focus not only on urban-rural comparisons, but also on mortality and health differences within rural populations. A closer examination of the widening gaps between urban and rural residents suggest that there is an important racial component to the rural mortality penalty. Although rural Americans, both black and white, have substantial mortality disadvantages, black rural residents are at an even greater disadvantage (James & Cossman, 2017). Black rural populations have worse overall health than rural white populations, with rural black adults at particularly high risk for chronic diseases, including diabetes, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease (Bennett, Olatosi, & Probst, 2008). The same disadvantages are also experienced by other rural populations of color, particularly American Indians. Further, in many regions, the health of rural populations of color is worse than their urban counterparts, highlighting poorly understood geographic dimensions implicit in ethnic and racial health disparities (James et al., 2017).

With important exceptions, only a limited subset of the population, namely Midwestern white, working class, or poor residents have received the majority of research and media attention. Although research that highlights how health differences vary across diverse rural regions find notable and significant differences (James, 2014; Knudson et al., 2015), detailed health assessments of other rural populations including the middle class, southerners, northeasterners and populations of color remain underrepresented. In order to fully understand and eliminate entrenched population health disparities, current and future population health efforts must prioritize inclusion of communities that reflect the true diversity of rural populations.

In our own research with a racially heterogeneous, rural community in North Carolina, we have been able to examine social and environmental stressors implicated as key contributors to ethnic and racial health disparities. We investigated the complex mechanisms driving disparities in chronic kidney disease in an economically depressed, racially diverse rural community. In this region, Lumbee American Indians and African Americans suffer a 2-fold greater risk of diabetes and hypertension and a 2-fold greater risk of death from chronic kidney disease compared with other racial and ethnic minorities across the state (North Carolina State Center for Health Statistics, 2010; United States Census Bureau, 2017).

Several indicators from our observational cohort study suggest health disparities arise from socioecological determinants, both shared and unique to rural communities. Lifestyle-related risk factors, socioeconomic status, access to healthcare, and health literacy all play central roles in the disparate health outcomes experienced by the residents of this rural county, which are findings consistent with a large body of evidence in rural health. Nonetheless, compared with white people in this community, ethnic and racial minorities report greater levels of everyday stress, including stress from overwork, the neighborhood environment, and meeting basic daily needs. Accumulated chronic stressors are increasingly recognized to cause ‘wear and tear’ on an individual's body that over time leads to prolonged physiologic burden beyond normal homeostasis, a process called allostatic load. The role of allostatic load as a key biologic mediator of the effects of cumulative stress exposures on health is evident (Seeman, Singer, Rowe, Horwitz, & McEwen, 1997); yet, few studies have examined its role in ethnic and racial health disparities within rural communities.

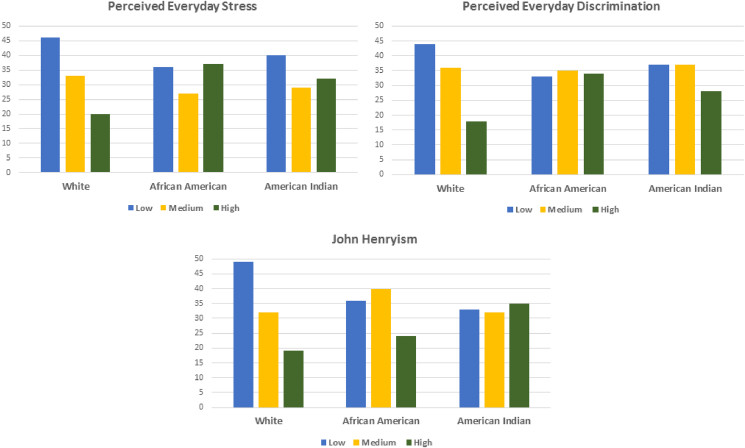

In our study, African Americans (AA) were nearly twice as likely as Whites to report high everyday stress (RR 1.75; 95% CI 1.05, 2.92) and American Indians (AI) were 1.5 times more likely as Whites to report high everyday stress (RR = 1.51; 95% CI 1.03, 2.17). Minorities (AA and AI) were 1.5 times more likely to report everyday discrimination (RR = 1.55; 95% CI 1.04, 2.35). Likewise, both African Americans and American Indians report significantly greater John Henyrism -- a measure of high effortful coping with prolonged stresses -- which in other settings has been associated with worse chronic disease outcomes (Subramanyam et al., 2013) (RR = 1.88; 95% CI 1.24, 2.85). (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Race differences on stress measures.

Another facet of stress in these communities reflects concerns about exposures to environmental toxins. Although Black and American Indian participants did not have more exposure to toxins than Whites did, our interview data suggest that these residents experience a heightened sense of stress and anxiety about such exposures which itself has been found to exacerbate negative health risk (Thoits, 2010). In interviews, ethnic and racial minority residents expressed distress about water-contamination, heavy pesticide use on crops, and other environmental risk factors that contribute heavily to poor health. These participants have much reason for concern about contamination. As one example, high levels of PFCs dumped into local waterways by a chemical company led to contaminated public water supplies, prompting government officials to request a public health assessment and impose injunctions (Sun et al., 2016). Exposure to PFCs through water and household items is increasingly recognized as a risk for diabetes, cancers, and kidney disease (Stanifer et al., 2018). The health implications of willfully exposing rural communities to toxic environmental waste include not just biological effects but also effects on more distal perceptions and behaviors. When community members interpret environmental toxin exposure as a reflection of societal disregard, the downstream effects on motivation to maintain healthy behaviors, mental health, and attitudes about illness may play important roles in observed racial health disparities.

A broader, more inclusive population-based approach to rural health will require careful consideration of the distinct cultural characteristics and social inequities occurring in rural communities. We offer three recommendations to pursue more impactful rural health research.

First, public health researchers and practitioners must recognize that each socially distinguishable population warrants its own in-depth investigation. Additionally, each population will optimally benefit from tailored interventions that incorporate unique shared perspectives. Moreover, interactions across multiple dimensions of identity, such as race/ethnicity and region of country, require more careful consideration. Health behavior models developed with urban majority populations obscure important social heterogeneity, cultural variation, and structural differences associated with diverse identity groups living in rural communities. For example, conventional socioeconomic status reliably predicts the health of white Americans. Dressler and colleagues (Dressler, Bindon, & Neggers, 1998) however, found that compared with socioeconomic status, cultural consensus (agreement on what constitutes a desirable and successful life in the immediate social environment) and consonance (degree to which individuals or families were able to meet these expectations) were more predictive of reduced hypertension risk in a southern Black American community. Furthermore, public health strategies that fail to recognize such key differences in the needs of rural communities also risk exaggerating expectations of positive health outcomes across distinct population groups and may even exacerbate the poor health status of already vulnerable populations (Geronimus, 2000; Pearson, 2008). Evidence suggests that public policy efforts proposing to improve birth outcomes for all populations by using traditional widely-adopted interventions like increasing access to prenatal care have, in select cases, inadvertently increased black/white differences (Goldenberg et al., 1996; Lu & Halfon, 2003).

A second step toward greater inclusivity requires understanding the facilitators and barriers to positive behavior change in rural communities. This approach has two parts: perspective and measurement. Perspective requires recognizing how individual-level, proximal behaviors are influenced by the broader social context in which people in rural communities live. This is a goal for all population health endeavors; however, understanding the contextual determinants specific to rural communities poses unique challenges. These individual and structural perspectives are not mutually exclusive. Developing individual- or community-level interventions designed to encourage healthy behaviors does not preclude casting a critical eye towards understanding the broader institutional and structural contexts that constrain individual choice and, by extension, reproduce oppression of targeted groups (Richman & Hatzenbuehler, 2014). Many past efforts to address these phenomena have miscast adaptive behavioral responses developed by marginalized populations as social or cultural pathology. For example, urban studies that found differences in fertility timing, extended family networks, alternative household composition and innovative economic enterprising were, in work during the great society era, described as pathological. Subsequent investigations revealed that these were socio-cultural and socio-behavioral mechanisms developed to help stave off despair and distress (Geronimus et al., 1994; Stack & Linda, 1993). Consequently, researchers proposing to integrate these and similar perspectives should exercise caution and humility as they defer to community members' expertise in explaining their own lives.

The measurement aspect of better understanding positive behavior change in rural communities involves developing more progressive, integrative assessment tools incorporating the social and environmental context. The majority of survey instruments designed to measure latent constructs representing social and contextual determinants of health were developed in urban settings or with majority population. As such, many widely used validated instruments are not well-suited to capture the lived experiences of rural life. In our research, when we administered the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2010) dietary screener, we found that it lacked nuance in reflecting local dietary patterns, particularly for the distinct American Indian cultural groups living in the area. Further, as many residents live on family farmlands, questionnaires designed to measure neighborhood cohesion missed contextual factors such as the close proximity of family members and ill-defined geographic boundaries defining “neighborhood”. We also experienced challenges with survey items designed to measure the neighborhood environment, particularly the built environment and the social environment around crime. For example, survey items about lack of sidewalks, excessive noise, or heavy traffic had no context for many participants, and survey items designed to measure crime were focused on urban problems, such as gang violence, and lacked recognition of opioid-related crimes ravaging rural America. More health assessment instruments such as the Rural Active Living Perceived Environmental Support Scale (RALPESS) (Umstattd et al., 2011) that are designed for and validated with rural communities are needed.

A related measurement challenge many rural health researchers face is one of logistics, particularly around communication and long-distances required for study interviews. In our research, frequent telephone disconnections, lack of electricity in many participants' homes, and limited access to the internet were substantial barriers in recruitment. The long distances (sometimes >30 miles) required for study interviews coupled with no public transportation system meant that interviews often had to be re-scheduled, cancelled, or conducted as home visits, and reimbursement for travel was a critical factor allowing many participants the opportunity to participate.

A third step toward greater inclusivity involves assessment of the strengths of local communities in order to leverage existing resources as part of broader public health strategies. There are many aspects to this goal, including identifying the deficits in services and public resources and developing recommendations for better systems of care to connect rural residents with social services broadly defined. The use of patient navigators as one such mechanism have found success in some communities and would benefit from further examination in rural areas. Telehealth technology may be a critical means by which rural communities can receive services that may otherwise be unavailable, including specialty care that address the most pressing rural health issues. However, there are limitations to how effective this technology can be since many rural communities do not have access to broadband, high-speed support. A stronger investment in community-based participatory research that informs best practices for this range of potential resources is essential to improve health for rural residents.

In conclusion, accumulated, life-course stressors appear to play key roles in driving ethnic and racial disparities in rural communities, and there remains a critical need to develop population-health assessment tools for measuring chronic stressors in rural residents. Further, intervention strategies must be designed to reflect both the environmental and cultural contexts of rural residents as well as their behavioral responses. These efforts need to recognize that important heterogeneity across multiple dimensions of rural life demand uniquely tailored approaches to reflect uniquely diverse rural experiences. Population-based interventions aimed to improve the physical, mental, and social well-being of rural residents are most likely to make positive change when both the uniquely stressful circumstances and the notable resources of the local communities are taken into consideration.

Declarations of interest

None.

References

- Bennett K.J., Olatosi B., Probst J.C. South Carolina Rural Health Research Center; Columbia: 2008. Health disparities: A rural-urban chartbook. [Google Scholar]

- Case A., Deaton A. Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112(49):15078–15083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518393112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National health and nutrition examination survey questionnaire (or examination protocol, or laboratory protocol) U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Hyattsville, MD: 2010. National center for health Statistics (NCHS) [Google Scholar]

- Cosby A.G., McDoom-Echebiri M., James W. Growth and persistence of place-based mortality in the United States: The rural mortality penalty. American Journal of Public Health. 2019;109:155–162. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosby A.G., Neaves T.T., Cossman R.E., Cossman JS, James WL, Feierabend N, Mirvis DM, Jones CA, Farrigan T. Preliminary evidence for an emerging nonmetropolitan mortality penalty in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:1470–1472. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.123778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dressler W.W., Bindon J.R., Neggers Y.H. Culture, socioeconomic status, and coronary heart disease risk factors in an African American community. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1998;21(6):527–544. doi: 10.1023/a:1018744612079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhardt M.S., Pamuk E.R. The importance of place of residence: Examining health in rural and nonrural areas. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(10):1682–1686. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.10.1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus A.T. The weathering hypothesis and the health of African-American women and infants. In: Sen G., Snow R.C., editors. Power and decision: The social Control of reproduction. Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies; Cambridge, MA: 1994. pp. 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus A.T. To mitigate, resist, or undo: Addressing structural influences on the health of urban populations. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90(6):867–872. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.6.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg R.L., Cliver S.P., Mulvihill F.X., Hickey C.A., Hoffman H.J., Klerman L.V. Medical, psychosocial, and behavioral risk factors do not explain the increased risk for low birth weight among black women. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1996;175(5):1317–1324. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley D. Rural health disparities, population health, and rural culture. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(10):1675–1678. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.10.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James W.L. All rural places are not created equal: Revisiting the rural mortality penalty in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104:2122–2129. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James W., Cossman J.S. Long-term trends in black and white mortality in the rural United States: Evidence of a race-specific rural mortality penalty. The Journal of Rural Health. 2017;33 doi: 10.1111/jrh.12181. 21-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James C.V., Moonesinghe R., Wilson-Frederick S.M., Hall J.E., Penman-Aguilar A., Bouye K. Racial/ethnic health disparities among rural adults — United States, 2012–2015. MMWR Surveillance Summaries. 2017;66(No. SS-23):1–9. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6623a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudson A., Meit M., Tanenbaum E. Rural Health Reform Policy Research Center; Bethesda, MD: 2015. Exploring rural and urban mortality differences. [Google Scholar]

- Lu M.C., Halfon N. Racial and ethnic disparities in birth outcomes: A life-course perspective. Journal of Maternal and Child Health. 2003;7(1):13–30. doi: 10.1023/a:1022537516969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North Carolina State Center for Health Statistics . North Carolina Minority Health Facts: American Indians; 2010. Office of minority health and health disparities. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson J. Can't buy me whiteness: New lessons from the titanic on race, ethnicity, and health. Du Bois Review. 2008;5(1):27–47. [Google Scholar]

- Richman L.S., Hatzenbuehler M.L. A multilevel Analysis of stigma and health. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2014;1(1):213–221. [Google Scholar]

- Seeman T.E., Singer B.H., Rowe J.W., Horwitz R.I., McEwen B.S. Price of adaptation—allostatic load and its health consequences: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1997;157:2259–2268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stack C., Linda M. Kinscripts. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 1993;24(2):157–170. Burton. [Google Scholar]

- Stanifer J.W., Stapleton H.M., Souma T., Wittmer A., Zhao X., Boulware L.E. Perfluorinated chemicals as emerging environmental threats to kidney health: A scoping review. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2018;13(10):1479–1492. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04670418. CJN.04670418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein E.M., Gennuso K.P., Ugboaja D.C., Remington P.L. The epidemic of despair among white Americans: Trends in the leading causes of premature death, 1999–2015. American Journal of Public Health. 2017;107(10):1541–1547. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanyam M.A., James S.A., Diez-Roux A.V., Hickson D.A., Sarpong D., Sims M. Socioeconomic status, John henryism and blood pressure among African-Americans in the jackson heart study. Social Science & Medicine. 2013;93:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M., Arevalo E., Strynar M., Lindstrom A., Richardson M., Kearns B. Legacy and emerging perfluoroalkyl substances are important drinking water contaminants in the cape fear river watershed of North Carolina. Environmental Science and Technology Letters. 2016;3(12):415–419. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits P.A. Stress and health: Major findings and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;(51):541–543. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umstattd M.R. Development of the rural active living perceived environmental support scale (RALPESS) Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2011;9(5):724–730. doi: 10.1123/jpah.9.5.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau . 2017. State & county quickfacts: Robeson county, North Carolina.http://quickfacts.census.gov Accessible at. [Google Scholar]