Abstract

Photonic

quantum technologies call for scalable quantum light sources

that can be integrated, while providing the end user with single and

entangled photons on demand. One promising candidate is strain free

GaAs/AlGaAs quantum dots obtained by aluminum droplet etching.

Such quantum dots exhibit ultra low multi-photon probability and an

unprecedented degree of photon pair entanglement. However, different

to commonly studied InGaAs/GaAs quantum dots obtained by the Stranski–Krastanow

mode, photons with a near-unity indistinguishability from these quantum

emitters have proven to be elusive so far. Here, we show on-demand

generation of near-unity indistinguishable photons from these quantum

emitters by exploring pulsed resonance fluorescence. Given the short

intrinsic lifetime of excitons and trions confined in the GaAs quantum

dots, we show single photon indistinguishability with a raw visibility

of  , without the need

for Purcell enhancement.

Our results represent a milestone in the advance of GaAs quantum dots

by demonstrating the final missing property standing in the way of

using these emitters as a key component in quantum communication applications,

e.g., as quantum light sources for quantum repeater architectures.

, without the need

for Purcell enhancement.

Our results represent a milestone in the advance of GaAs quantum dots

by demonstrating the final missing property standing in the way of

using these emitters as a key component in quantum communication applications,

e.g., as quantum light sources for quantum repeater architectures.

Keywords: Semiconductor quantum dot, resonance fluorescence, indistinguishable photons, Al droplet etching

Most applications in photonic

quantum technologies rely on clean quantum interference of deterministically

generated single and entangled photons. Quantum indistinguishability

is a crucial ingredient for the creation of higher N00N states,1,2 quantum teleportation3 and swapping operations,4 boson-sampling,5,6 and photon-based

quantum simulations.7 An ideal quantum

light source thus needs to emit photons on demand, with high purity

and near-unity indistinguishability as well as being scalable and

interconnected with different quantum systems. Semiconductor quantum

dots are proving to be the best sources that fulfill these requirements,8 delivering ultra bright sources of on-demand

single photons at high rates compatible with photonic circuitry. Recently,

GaAs quantum dots obtained by the infilling of nanoholes produced

by local droplet etching9 have emerged

to be one of the most promising deterministic solid-state quantum

light sources, reporting the lowest multi-photon probability10 and the highest degree of polarization entanglement11 while also being the brightest entangled photon

pair source reported.12 Entangled photons

from these quantum dots have also been used to implement quantum teleportation13 and entanglement swapping protocols,14 thus proving their potential for quantum network

applications. Furthermore, their short intrinsic lifetime enables

high-repetition rate single-photon sources and, together with the

high symmetry of the quantum dots, results in improved entanglement

fidelities.11 Another advantage of these

quantum dots is that they have reduced strain gradients compared to

commonly studied dots obtained by the Stranski–Krastanow growth

mode and are expected to have long nuclei ensemble spin coherence,

promising for quantum-dot-based quantum memories.15 Additionally, their emission wavelength range makes them

suitable for hybrid quantum photonic technologies since they can be

tuned into resonance with quantum memories, e.g. rubidium atoms.16,17 However, near-unity indistinguishable photons, a crucial element

for photonic quantum technologies, was missing from this type of quantum

dots until now. Strong charge fluctuations at the vicinity of the

quantum dot,18,19 induced by the droplet growth

method20 and faster phonon-induced pure

dephasing21 and zero-phonon broadening22 were suspected to be the main causes of the

lower quantum interference visibility for these quantum emitters.

In this letter, we apply cross-polarized pulsed resonance fluorescence

to show that quantum dots derived from droplet etching do not suffer

from additional dephasing mechanisms at short time scales and exhibit

near-unity indistinguishability of on-demand generated single photons.

Remarkably, high quantum interference visibility values of  are achieved without

the need of Purcell

enhancement using microcavities.23−25 Instead, we capitalize

on the intrinsically short lifetime of the excited states of these

quantum emitters.26

are achieved without

the need of Purcell

enhancement using microcavities.23−25 Instead, we capitalize

on the intrinsically short lifetime of the excited states of these

quantum emitters.26

For pulsed resonant

s-shell excitation,27 a polarization suppression

setup was constructed similar to that

in ref (28) but with

the second polarizing beam splitter (PBS) replaced by a nanoparticle

linear film polarizer, as illustrated in Figure 1 a. The sample was mounted in a low vibration

closed-cycle cryostat and cooled to 5 K. For excitation, a tunable,

linearly polarized laser was used with a repetition rate of 80 MHz

and pulse duration of 5.0 ps after sending the pulse through a pulse

slicer. The excitation beam was directed onto the sample via the polarizing

beam splitter, through an objective with  , and focused onto the quantum dot of interest

using a solid immersion lens (SIL), directly attached to the sample

surface. The signal was collected through the same optics in a confocal

geometry and separated from the backscattered excitation laser by

the polarizing beam splitter and a linear polarizer oriented perpendicular

to the laser polarization. Further improvement of the laser suppression

was achieved by spatial filtering since a small portion of the backscattered

laser has a component perpendicular to the original polarization with

a four-leaf clover patterned beam profile.29

, and focused onto the quantum dot of interest

using a solid immersion lens (SIL), directly attached to the sample

surface. The signal was collected through the same optics in a confocal

geometry and separated from the backscattered excitation laser by

the polarizing beam splitter and a linear polarizer oriented perpendicular

to the laser polarization. Further improvement of the laser suppression

was achieved by spatial filtering since a small portion of the backscattered

laser has a component perpendicular to the original polarization with

a four-leaf clover patterned beam profile.29

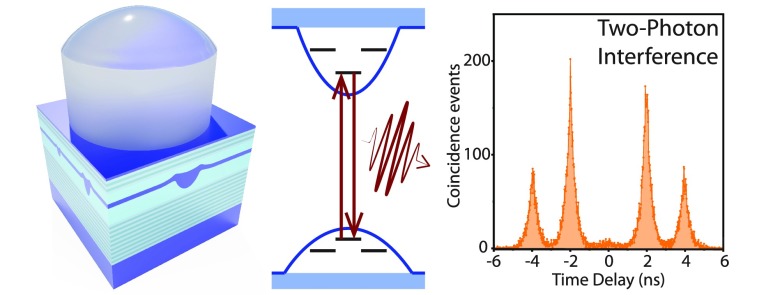

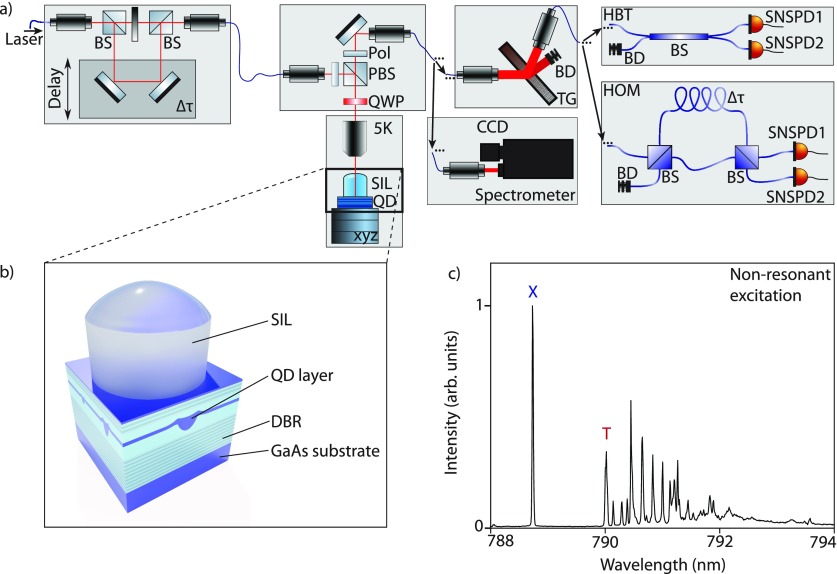

Figure 1.

(a) The modular setup consisting of laser excitation with delay line, the confocal microscopy setup with polarization suppression, the transmission spectrometer, the Hanbury-Brown and Twiss setup (HBT), and the Hong–Ou–Mandel setup (HOM). BS, beam splitter; BD, beam dump; TG, transmission grating; SNSPD, superconducting nanowire single photon detector; Pol, polarizer; PBS, polarizing beam splitter; QWP, quarter waveplate; SIL, solid immersion lens. (b) Schematic illustration of the sample structure. (c) Spectrum of QD1 under non-resonant excitation.

To perform photoluminescence measurements, the signal was coupled through a spectrometer onto a silicon CCD. For correlation measurements, the resonance fluorescence signal was further filtered with a home-built transmission spectrometer having a bandwidth of 19 GHz and an end-to-end efficiency exceeding 60%. Second-order intensity correlation measurements were carried out with a Hanbury–Brown and Twiss type setup realized with a fiber coupled 50:50 beam splitter connected to two superconducting nanowire single photon detectors (SNSPD) with efficiencies of 50% and 60%, a timing jitter of 20 and 30 ps, and dark count rates of 0.006 and 0.017 dcts/s. The detection events are recorded in a timetag file along with laser excitation events and analyzed with our Extensible Timetag Analyzer (ETA) software.30 To determine the indistinguishability of two consecutively emitted photons, two-photon interference was measured in a Hong–Ou–Mandel (HOM) type experiment. In order to interfere, these photons must impinge on a beam splitter with excellent spatial and temporal overlap. The temporal overlap is achieved by sending the signal into an unbalanced fiber-based Mach–Zehnder interferometer with a path-length difference of 2 ns. The two output ports of the Mach–Zehnder interferometer are connected to a SNSPD each. Depending on the paths the photons take, they can arrive on the beam splitter simultaneously or with a time delay of 2 or 4 ns, resulting in the characteristic quintuplet for Hong–Ou–Mandel measurements31 in the histogram. The temporal overlap of the photons on the second beam splitter is ensured by splitting the excitation pulse into two identical pulses using another unbalanced Mach–Zehnder interferometer with variable delay. This delay is precisely tuned to the fixed fiber delay in the Hong–Ou–Mandel setup by measuring the interference of overlapping short laser pulses using the same detectors as for all the correlation measurements. For the best possible time resolution, unsliced laser pulses with a pulse duration of 1.94 ps were used.

The GaAs quantum dot sample investigated

in this work was grown

by molecular beam epitaxy using the aluminum droplet etching technique.

The quantum dot layer was embedded in a λ-cavity made of  (123 nm) with 9.5 pairs of bottom and 2.5

pairs of top distributed Bragg reflectors (DBR) consisting of

(123 nm) with 9.5 pairs of bottom and 2.5

pairs of top distributed Bragg reflectors (DBR) consisting of  /

/

-thick

layers, as depicted in Figure 1 b. The structure was finished

by a 4 nm thick protective GaAs layer. The Al-droplet etching method

allows the growth of highly symmetric quantum dots with a low fine

structure splitting (FSS).32 This sample

structure shows an extraction efficiency of

-thick

layers, as depicted in Figure 1 b. The structure was finished

by a 4 nm thick protective GaAs layer. The Al-droplet etching method

allows the growth of highly symmetric quantum dots with a low fine

structure splitting (FSS).32 This sample

structure shows an extraction efficiency of  % into the first lens for a quantum dot

well-positioned under the SIL.

% into the first lens for a quantum dot

well-positioned under the SIL.

In Figure 1 c we show the spectrum of QD1 subject to pulsed non-resonant excitation at a wavelength of 781 nm. The neutral exciton (X), emitting at 788.73 nm, is isolated from the rest of emission lines at longer wavelengths, which are attributed to electron-hole recombination in the presence of additional carriers in the quantum dot which stem from nearby confined states due to the weak confinement in shallow quantum dots.33 The trion (T) transition corresponds to the peak at 790.02 nm. To resonantly excite an s-shell transition (X or T), we tune the energy of the excitation laser to the transition energy, ideally resulting in photoluminescence only from this specific transition. Furthermore, the dephasing due to interactions with phonons and nearby trapped charge carriers is reduced.34 To address the electric environment of the dot, we additionally illuminate the sample with a low intensity white light source.35,36 This results in a very clean spectrum with only one prominent line of the exciton transition and minor contribution of less than 2% from the trion transition as shown in a semi-logarithmic plot in Figure 2 a.

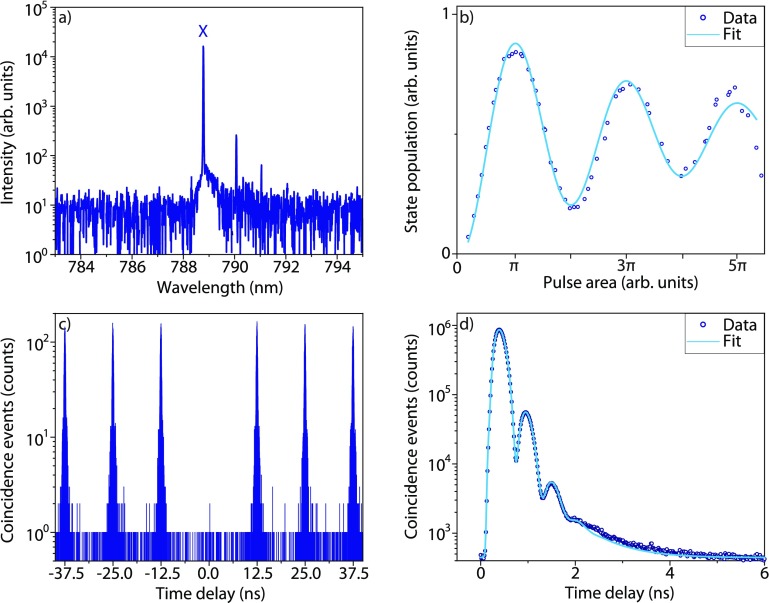

Figure 2.

Characterization of the

neutral exciton under pulsed resonant s-shell

excitation. (a) Resonance fluorescence spectrum in a semi-logarithmic

plot. (b) Excitation laser power-dependent Rabi oscillation up to

a pulse area of 5π. From our fit we extract an occupation probability

of 85% under π-pulse excitation. (c) Second-order intensity

correlation histogram yielding  (d) Semi-logarithmic plot of the lifetime

measurement with oscillations due to the fine structure splitting.

The fit gives a lifetime of

(d) Semi-logarithmic plot of the lifetime

measurement with oscillations due to the fine structure splitting.

The fit gives a lifetime of  ps and a fine structure splitting of

ps and a fine structure splitting of  μeV.

μeV.

To show that this excitation scheme addresses the quantum dot coherently, we performed power-dependent pulsed resonance fluorescence measurements. In Figure 2 b, Rabi oscillations of the integrated intensity of the neutral exciton transition as a function of the excitation pulse area are shown. By exciting the quantum dot with a power corresponding to a pulse area of π, the population of the two-level system of the quantum dot is maximally inverted, preparing the quantum dot in the excited state. The procedure used to fit the data is explained in the Supporting Information. We extract a population probability for the neutral exciton state of 85% under π-pulse excitation. For all further measurements, the quantum dot is excited with a π-pulse.

The second-order intensity correlation function shown in Figure 2 c shows nearly background

free single photon emission. By calculating the ratio of the area

of the center peak and average area of eight side peaks in a time

window of 3.2 ns each, a measured degree of second-order coherence

of  is determined.

We attribute the deviation

from 0 solely to re-excitation37 and conclude

that there is negligible residual excitation laser present in the

correlation measurement.

is determined.

We attribute the deviation

from 0 solely to re-excitation37 and conclude

that there is negligible residual excitation laser present in the

correlation measurement.

Figure 2 d shows

the lifetime measurement of the resonantly excited neutral exciton

in a semi-logarithmic plot. The exponential decay is observed with

a periodic modulation.38 Due to the exchange

interaction between the electron and hole spins, the degeneracy of

the exciton states of the quantum dot is lifted, leading to two linearly

cross-polarized fine structure (FS) states with an energy splitting

of  . During excitation, the

spin of the exciton

state is determined by the polarization of the excitation pulse.39,40 Then, the spin starts precessing on the equator of the Bloch sphere,

oscillating between the two orthogonal fine structure states. The

polarization of the emitted photon is set by the spin at the time

of the recombination. Since one polarization component is suppressed

by the polarizers in our setup, the intensity of the detected signal

oscillates with a frequency

. During excitation, the

spin of the exciton

state is determined by the polarization of the excitation pulse.39,40 Then, the spin starts precessing on the equator of the Bloch sphere,

oscillating between the two orthogonal fine structure states. The

polarization of the emitted photon is set by the spin at the time

of the recombination. Since one polarization component is suppressed

by the polarizers in our setup, the intensity of the detected signal

oscillates with a frequency  .41 The data

is modeled with a fit explained in the Supporting Information, which yields a lifetime of

.41 The data

is modeled with a fit explained in the Supporting Information, which yields a lifetime of  ps and a fine structure splitting of

ps and a fine structure splitting of  μeV.

μeV.

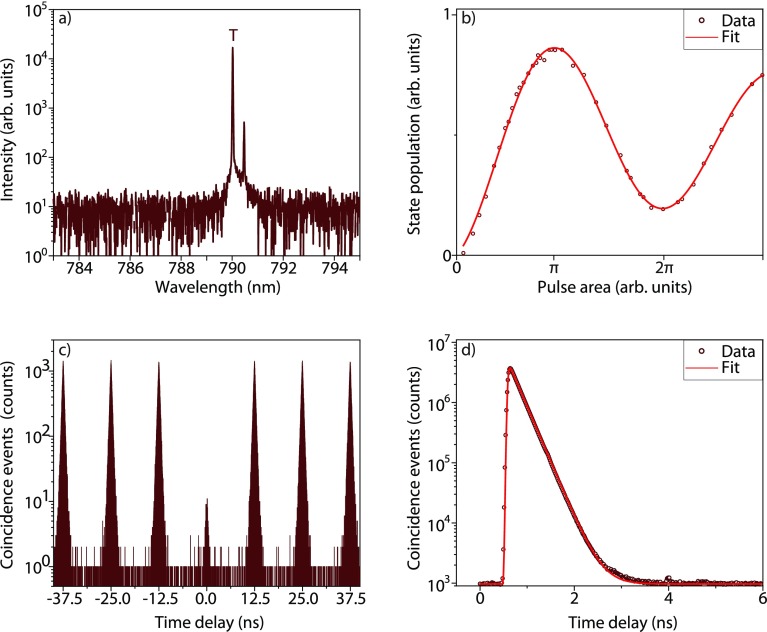

In order to point out similarities with and differences

to the

neutral exciton, we investigate the resonantly excited charged exciton

as well. Figure 3 a

shows the spectrum of the trion of QD1 under pulsed resonant excitation.

We observe an additional line close to the trion transition with  times lower intensity, which might be a

higher charge state emitting after a second capture process. Similar

to the neutral exciton, we observe clear Rabi oscillations as a function

of the excitation pulse area, as shown in Figure 3 b, and a maximum population inversion probability

of

times lower intensity, which might be a

higher charge state emitting after a second capture process. Similar

to the neutral exciton, we observe clear Rabi oscillations as a function

of the excitation pulse area, as shown in Figure 3 b, and a maximum population inversion probability

of  under π-pulse

excitation. The second-order

intensity correlation function yields a measured degree of second-order

coherence of

under π-pulse

excitation. The second-order

intensity correlation function yields a measured degree of second-order

coherence of  , as shown in Figure 3 c, confirming that the laser suppression

is very good. In Figure 3 d we show a semi-logarithmic plot of a lifetime measurement. A single

exponential fit gives a lifetime of

, as shown in Figure 3 c, confirming that the laser suppression

is very good. In Figure 3 d we show a semi-logarithmic plot of a lifetime measurement. A single

exponential fit gives a lifetime of  . As opposed to the lifetime measurement

of the neutral exciton in Figure 3 d, this measurement shows no quantum beats, due to

the lack of fine structure splitting of the trion state.42

. As opposed to the lifetime measurement

of the neutral exciton in Figure 3 d, this measurement shows no quantum beats, due to

the lack of fine structure splitting of the trion state.42

Figure 3.

Characterization of the trion under pulsed s-shell resonant

excitation.

(a) Resonance fluorescence spectrum in a semi-logarithmic plot. The

origin of the ≈30× less intense line is discussed in the

main text. (b) Rabi oscillation up to a pulse area of 3π. (c)

Second-order intensity correlation histogram yielding  (d) Semi-logarithmic

plot of the lifetime

measurement fitted with a single exponential decay giving us a lifetime

of

(d) Semi-logarithmic

plot of the lifetime

measurement fitted with a single exponential decay giving us a lifetime

of  .

.

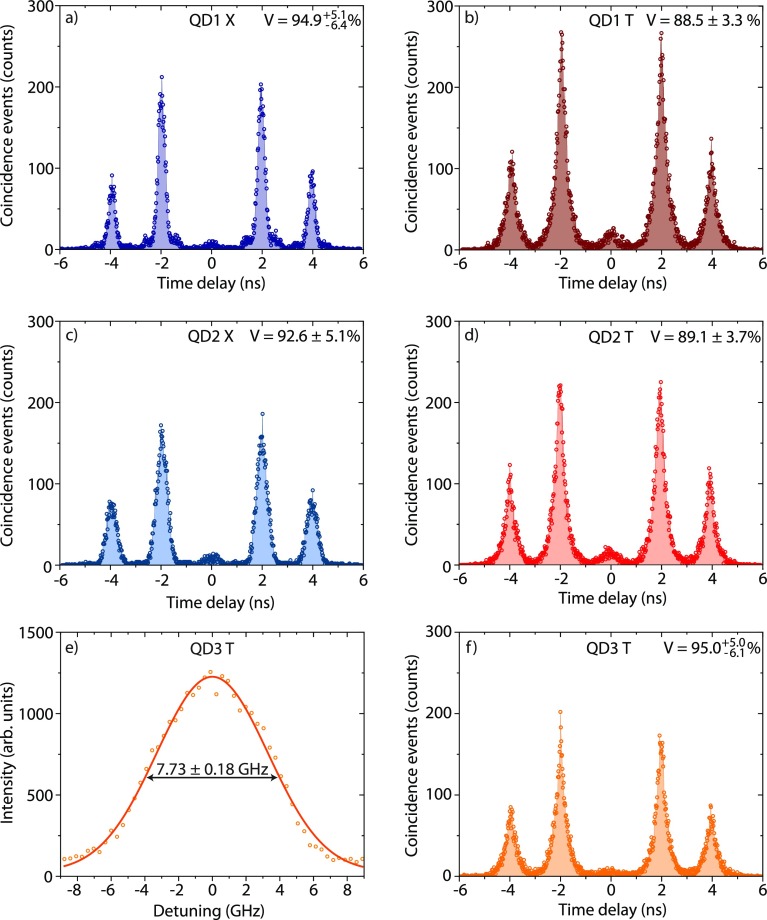

Having confirmed low multi-photon emission probability for both neutral and charged excitons under π-pulse resonant excitation, we continue to investigate the indistinguishability of consecutively emitted photons using a two-photon interference measurement, as described above. In Figure 4 a and b the center peak quintuplet for two-photon interference measurements of the neutral exciton and trion of QD1 are shown. The relative peak heights originate from different combinations of long and short paths in the Mach–Zehnder interferometer two consecutive photons can take. In the Hong–Ou–Mandel measurement of the neutral exciton, the same oscillations as in the lifetime measurements are visible.

Figure 4.

Hong–Ou–Mandel measurements under resonant s-shell

excitation for the (a) neutral exciton of QD1  , (b) trion of QD1

, (b) trion of QD1  , (c)

neutral exciton of QD2

, (c)

neutral exciton of QD2  , (d)

trion of QD2

, (d)

trion of QD2  , and (f) trion of QD3

, and (f) trion of QD3  . The visibilities are calculated by summing

up the peak areas of the three center peaks. The method is explained

in more detail in the Supporting Information; (e) line width of the trion of QD3 with a Gaussian fit

. The visibilities are calculated by summing

up the peak areas of the three center peaks. The method is explained

in more detail in the Supporting Information; (e) line width of the trion of QD3 with a Gaussian fit  .

.

In the limit of  , the visibility of two-photon interference

can be calculated from the area of the three center peaks A1,2,3 by

, the visibility of two-photon interference

can be calculated from the area of the three center peaks A1,2,3 by  , where

, where  corresponds to perfectly indistinguishable

photons.31 To calculate the peak area of

the three center peaks, the coincidence events are summed up in time

windows which are individual for every transition (see details in

the Supporting Information). The uncorrected

visibilities for QD1 are

corresponds to perfectly indistinguishable

photons.31 To calculate the peak area of

the three center peaks, the coincidence events are summed up in time

windows which are individual for every transition (see details in

the Supporting Information). The uncorrected

visibilities for QD1 are  with a statistical error

with a statistical error  and

and  for

the neutral exciton and

for

the neutral exciton and  for the trion. To compensate for imperfections

in the setup, we measure the classical interference fringe visibility

with a narrow continuous wave diode laser to be

for the trion. To compensate for imperfections

in the setup, we measure the classical interference fringe visibility

with a narrow continuous wave diode laser to be  , which yields the upper measurable

bound

of the visibility in this setup. In general, we are able to show very

high indistinguishability visibilities by performing the Hong–Ou–Mandel

measurement on further dots, as shown in Figure 4 c, d, and f. Here we obtain a visibility

of

, which yields the upper measurable

bound

of the visibility in this setup. In general, we are able to show very

high indistinguishability visibilities by performing the Hong–Ou–Mandel

measurement on further dots, as shown in Figure 4 c, d, and f. Here we obtain a visibility

of  for the neutral exciton,

for the neutral exciton,  for the trion of QD2, and

for the trion of QD2, and  for the trion of QD3. This value

is the

highest obtained visibility for on-demand sources without Purcell

enhancement or more elaborate excitation techniques.43 We would like to note that fitting the Hong–Ou–Mandel

data, instead of summing up the data in specified time windows, very

often overestimates the two-photon interference visibility, in particular

if the data were collected with low timing resolution. Especially

when the low time resolution is masking quantum beats and the dip

at zero time delay, fitting can wrongly increase the visibility and

even lead to unphysical results, i.e., visibilities above

for the trion of QD3. This value

is the

highest obtained visibility for on-demand sources without Purcell

enhancement or more elaborate excitation techniques.43 We would like to note that fitting the Hong–Ou–Mandel

data, instead of summing up the data in specified time windows, very

often overestimates the two-photon interference visibility, in particular

if the data were collected with low timing resolution. Especially

when the low time resolution is masking quantum beats and the dip

at zero time delay, fitting can wrongly increase the visibility and

even lead to unphysical results, i.e., visibilities above  . This result is

even independent of the

used fit function (see details in the Supporting Information). We measure the line width of the trion transition

of QD3 by slowly scanning a Fabry–Pérot interferometer

with a resolution of

. This result is

even independent of the

used fit function (see details in the Supporting Information). We measure the line width of the trion transition

of QD3 by slowly scanning a Fabry–Pérot interferometer

with a resolution of  over the line and recording the

signal

on a SNSPD. Fitting the data with a Gaussian peak provides a line

width of

over the line and recording the

signal

on a SNSPD. Fitting the data with a Gaussian peak provides a line

width of  and is shown in Figure 4 e. Considering a

lifetime of

and is shown in Figure 4 e. Considering a

lifetime of  , we show that the line width is a factor

of 10 larger than the Fourier limit. As we are still measuring a very

high HOM visibility for this transition, this indicates negligible

spectral wandering on short time scales.

, we show that the line width is a factor

of 10 larger than the Fourier limit. As we are still measuring a very

high HOM visibility for this transition, this indicates negligible

spectral wandering on short time scales.

We point out that our

two-photon interference visibility value

of  is the highest raw value measured for any

on-demand source without a micro-cavity and marks an important milestone

for quantum dots derived from droplet etching. Near-unity indistinguishability

was the last missing quantum optical property to put GaAs quantum

dots on the horizon for future quantum communication and quantum information

processing applications. On the basis of our results, we foresee that

photonic structures other than cavities, e.g., waveguides, trumpets,

and nanowires44,45 to enhance light extraction efficiency

from solid-state emitters, can be used to achieve even higher levels

of indistinguishability without the need of Purcell enhancement.

is the highest raw value measured for any

on-demand source without a micro-cavity and marks an important milestone

for quantum dots derived from droplet etching. Near-unity indistinguishability

was the last missing quantum optical property to put GaAs quantum

dots on the horizon for future quantum communication and quantum information

processing applications. On the basis of our results, we foresee that

photonic structures other than cavities, e.g., waveguides, trumpets,

and nanowires44,45 to enhance light extraction efficiency

from solid-state emitters, can be used to achieve even higher levels

of indistinguishability without the need of Purcell enhancement.

Acknowledgments

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program (820423; S2QUIP), the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (SPQRel; 679183), the FWF (P 29603, P 30459), the Linz Institute of Technology, the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research via the funding program Photonics Research Germany (13N14846), Q.Com (16KIS0110) and Q.Link.X, the DFG via the Nanosystem Initiative Munich, the MCQST, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation grant “Quantum Sensors”, the Swedish Research Council (VR) through the VR grant for international recruitment of leading researchers (ref. 2013-7152), and the Linnæus Excellence Center ADOPT. K.D.Z. gratefully acknowledges funding by the Dr. Isolde Dietrich Foundation. K.M. acknowledges support from the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities. K.D.J. acknowledges funding from the Swedish Research Council (VR) via the starting grant HyQRep (ref. 2018-04812). A.R. acknowledges fruitful discussions with Y. Huo, G. Weihs, R. Keil, and S. Portalupi.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b05132.

Resonance fluorescence of GaAs quantum dots with near-unity photon indistinguishability; Rabi oscillation; time-correlated single-photon counting fit function including convolution with internal response function; polarization-resolved photoluminescence spectroscopy; and analysis of two-photon interference measurements (PDF)

Author Contributions

⊥ E. Schöll, L. Hanschke, and L. Schweickert contributed equally to this work. E.S. and K.D.J. built the setup with the help from K.D.Z., L.S., and T.L., E.S., L.H., L.S., K.D.Z., and K.D.J. performed the measurements. E.S., L.H., L.S., and K.D.Z. carried out the data analysis with help from K.D.J. S.F.C.S. and A.R. designed, optimized, and grew the quantum dot sample. M.R. and R.T. characterized the quantum dot sample, helping to optimize the sample. T.L. fabricated the final device with the help from R.T. E.S. and K.D.J. wrote the manuscript with help from all of the authors. K.D.J. conceived the experiment and supervised the project.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Walther P.; Pan J.-W.; Aspelmeyer M.; Ursin R.; Gasparoni S.; Zeilinger A. Nature 2004, 429, 158. 10.1038/nature02552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata T.; Okamoto R.; O’Brien J. L.; Sasaki K.; Takeuchi S. Science 2007, 316, 726–729. 10.1126/science.1138007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwmeester D.; Pan J.-W.; Mattle K.; Eibl M.; Weinfurter H.; Zeilinger A. Nature 1997, 390, 575–579. 10.1038/37539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J.-W.; Bouwmeester D.; Weinfurter H.; Zeilinger A. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 80, 3891–3894. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.80.3891. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spring J. B.; Metcalf B. J.; Humphreys P. C.; Kolthammer W. S.; Jin X.-M.; Barbieri M.; Datta A.; Thomas-Peter N.; Langford N. K.; Kundys D.; Gates J. C.; Smith B. J.; Smith P. G. R.; Walmsley I. A. Science 2013, 339, 798–801. 10.1126/science.1231692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broome M. A.; Fedrizzi A.; Rahimi-Keshari S.; Dove J.; Aaronson S.; Ralph T. C.; White A. G. Science 2013, 339, 794–798. 10.1126/science.1231440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspuru-Guzik A.; Walther P. Nat. Phys. 2012, 8, 285. 10.1038/nphys2253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Senellart P.; Solomon G.; White A. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2017, 12, 1026–1039. 10.1038/nnano.2017.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber D.; Reindl M.; Huo Y.; Huang H.; Wildmann J. S.; Schmidt O. G.; Rastelli A.; Trotta R. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15506. 10.1038/ncomms15506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweickert L.; Jöns K. D.; Zeuner K. D.; Covre da Silva S. F.; Huang H.; Lettner T.; Reindl M.; Zichi J.; Trotta R.; Rastelli A.; Zwiller V. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2018, 112, 093106. 10.1063/1.5020038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huber D.; Reindl M.; Covre da Silva S. F.; Schimpf C.; Martín-Sánchez J.; Huang H.; Piredda G.; Edlinger J.; Rastelli A.; Trotta R. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 121, 033902. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.121.033902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Zopf M.; Keil R.; Ding F.; Schmidt O. G. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2994. 10.1038/s41467-018-05456-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reindl M.; Huber D.; Schimpf C.; da Silva S. F. C.; Rota M. B.; Huang H.; Zwiller V.; Jöns K. D.; Rastelli A.; Trotta R. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaau1255. 10.1126/sciadv.aau1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso Basset F.; Rota M. B.; Schimpf C.; Tedeschi D.; Zeuner K. D.; Covre da Silva S. F.; Reindl M.; Zwiller V.; Jöns K. D.; Rastelli A.; Trotta R.. Entanglement swapping with photons generated on-demand by a quantum dot. 2019, arXiv:1901.06646.arXiv.org e-Prints. https://arxiv.org/abs/1901.06646 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gangloff D. A.; Éthier-Majcher G.; Lang C.; Denning E. V.; Bodey J. H.; Jackson D. M.; Clarke E.; Hugues M.; Le Gall C.; Atatüre M. Science 2019, eaaw2906. 10.1126/science.aaw2906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akopian N.; Wang L.; Rastelli A.; Schmidt O.; Zwiller V. Nat. Photonics 2011, 5, 230–233. 10.1038/nphoton.2011.16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schweickert L.; Jöns K. D.; Namazi M.; Cui G.; Lettner T.; Zeuner K. D.; Scavuzzo Montaña L.; Covre da Silva S. F.; Reindl M.; Huang H.; Trotta R.; Rastelli A.; Zwiller V.; Figueroa E.. Electromagnetically Induced Transparency of On-demand Single Photons in a Hybrid Quantum Network. 2018, arXiv:1808.05921.arXiv.org e-Print archive. https://arxiv.org/abs/1808.05921.

- Heyn C.; Zocher M.; Pudewill L.; Runge H.; Küster A.; Hansen W. J. Appl. Phys. 2017, 121, 044306. 10.1063/1.4974965. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Konthasinghe K.; Davanço M.; Lawall J.; Anant V.; Verma V.; Mirin R.; Nam S. W.; Song J. D.; Ma B.; Chen Z. S.; Ni H. Q.; Niu Z. C.; Srinivasan K. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2018, 9, 064019. 10.1103/PhysRevApplied.9.064019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyn C.; Stemmann A.; Köppen T.; Strelow C.; Kipp T.; Grave M.; Mendach S.; Hansen W. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 94, 183113. 10.1063/1.3133338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axt V. M.; Kuhn T.; Vagov A.; Peeters F. M. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2005, 72, 125309. 10.1103/PhysRevB.72.125309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tighineanu P.; Dreeßen C. L.; Flindt C.; Lodahl P.; Sørensen A. S. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 257401. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.120.257401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somaschi N.; et al. Nat. Photonics 2016, 10, 340–345. 10.1038/nphoton.2016.23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X.; He Y.; Duan Z.-C.; Gregersen N.; Chen M.-C.; Unsleber S.; Maier S.; Schneider C.; Kamp M.; Höfling S.; Lu C.-Y.; Pan J.-W. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 020401. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.020401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett A. J.; Lee J. P.; Ellis D. J. P.; Meany T.; Murray E.; Floether F. F.; Griffths J. P.; Farrer I.; Ritchie D. A.; Shields A. J. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1501256 10.1126/sciadv.1501256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiraz A.; Atatüre M.; Imamoğlu A. Phys. Rev. A: At., Mol., Opt. Phys. 2004, 69, 032305. 10.1103/PhysRevA.69.032305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He Y.-M.; He Y.; Wei Y.-J.; Wu D.; Atatüre M.; Schneider C.; Höfling S.; Kamp M.; Lu C.-Y.; Pan J.-W. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 213–217. 10.1038/nnano.2012.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlmann A. V.; Houel J.; Brunner D.; Ludwig A.; Reuter D.; Wieck A. D.; Warburton R. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2013, 84, 073905. 10.1063/1.4813879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novotny L.; Grober R. D.; Karrai K. Opt. Lett. 2001, 26, 789–791. 10.1364/OL.26.000789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweickert L.; Lin Z.; Zeuner K. D.; Lettner T.; Gyger S.; Zichi J.; Schöll E.; Jöns K. D.; Zwiller V.. ETA is a graphical event-driven programming language for time-tag processing. Zenodo: 2018; https://github.com/timetag; 10.5281/zenodo.1495352 [DOI]

- Santori C.; Fattal D.; Vucković J.; Solomon G. S.; Yamamoto Y. Nature 2002, 419, 594–7. 10.1038/nature01086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo Y. H.; Rastelli A.; Schmidt O. G. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 102, 152105. 10.1063/1.4802088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Musiał A.; Gold P.; Andrzejewski J.; Löffler A.; Misiewicz J.; Höfling S.; Forchel A.; Kamp M.; Sęk G.; Reitzenstein S. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2014, 90, 045430. 10.1103/PhysRevB.90.045430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ates S.; Ulrich S. M.; Reitzenstein S.; Löffler A.; Forchel A.; Michler P. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 103, 167402. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.167402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzano O.; Michaelis de Vasconcellos S.; Arnold C.; Nowak A.; Galopin E.; Sagnes I.; Lanco L.; Lemaître A.; Senellart P. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1425. 10.1038/ncomms2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reindl M.; Jöns K. D.; Huber D.; Schimpf C.; Huo Y.; Zwiller V.; Rastelli A.; Trotta R. Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 4090–4095. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b00777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer K. A.; Müller K.; Lagoudakis K. G.; Vučković J. New J. Phys. 2016, 18, 113053. 10.1088/1367-2630/18/11/113053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dada A. C.; Santana T. S.; Koutroumanis A.; Ma Y.; Park S.-I.; Song J.; Gerardot B. D. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2017, 96, 081404. 10.1103/PhysRevB.96.081404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kodriano Y.; Schwartz I.; Poem E.; Benny Y.; Presman R.; Truong T. A.; Petroff P. M.; Gershoni D. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2012, 85, 241304. 10.1103/PhysRevB.85.241304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Müller K.; Kaldewey T.; Ripszam R.; Wildmann J. S.; Bechtold A.; Bichler M.; Koblmüller G.; Abstreiter G.; Finley J. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1906. 10.1038/srep01906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flissikowski T.; Hundt A.; Lowisch M.; Rabe M.; Henneberger F. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 86, 3172–3175. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.3172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer M.; Ortner G.; Stern O.; Kuther A.; Gorbunov A. A.; Forchel A.; Hawrylak P.; Fafard S.; Hinzer K.; Reinecke T. L.; Walck S. N.; Reithmaier J. P.; Klopf F.; Schäfer F. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2002, 65, 195315. 10.1103/PhysRevB.65.195315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y.-J. J.; He Y.-M. M.; Chen M.-C. C.; Hu Y.-N. N.; He Y.-M. M.; Wu D.; Schneider C.; Kamp M.; Höfling S.; Lu C.-Y. Y.; Pan J.-W. W. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 6515–6519. 10.1021/nl503081n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregersen N.; McCutcheon D. P. S.; Mørk J.; Gérard J.-M.; Claudon J. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 20904–20924. 10.1364/OE.24.020904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulgarini G.; Reimer M. E.; Bouwes Bavinck M.; Jöns K. D.; Dalacu D.; Poole P. J.; Bakkers E. P. A. M.; Zwiller V. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 4102–4106. 10.1021/nl501648f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.