Abstract

Objective:

The number of older adults with alcohol use disorder (AUD) is expected to significantly increase in the coming years. Both aging and AUD have been associated with compromised white matter microstructure, although the extent of combined AUD and aging effects is unclear. This study investigated interactions between aging and AUD in cerebral white matter integrity using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI).

Method:

All participants (44 recently detoxified participants with AUD and 28 healthy controls; ages 31–64 years) completed neurocognitive testing and a DTI scan. Regions of interests were identified on Tract-Based Spatial Statistics images. Hierarchical multiple regression was used to examine interactions between age and AUD status on DTI values [e.g., fractional anisotropy (FA)].

Results:

Significant Age × AUD interactions were found across several prefrontal white matter regions (R2Δ = 5%–9%). Regional FA was negatively associated with age in the AUD group (rs = -.33–-.53) but not in the control group (rs = .18–-.32). This pattern remained after adjusting for lifetime history of drinking and recent drinking. Lifetime alcohol consumption negatively correlated with frontal white matter integrity in the AUD group (rs = -.33–-.40). Finally, processing speed was significantly slower in the AUD group versus controls (p = .001) and was positively correlated with FA values in frontal white matter regions (rs = .34–.53).

Conclusions:

Cumulative alcohol consumption may affect frontal white matter integrity, and persons with AUD may be more prone to reductions in frontal white matter integrity with advancing age. These reductions in frontal white matter integrity may contribute to reductions in processing speed.

It is projected that the number of adults age 50 and older in the United States with a substance use disorder, including alcohol use disorder (AUD), will increase dramatically within the next decade, from an estimated 2.8 million in 2006 up to a projected 5.8 million by 2020 (Han et al., 2009). This increase can be attributed to the large size of the baby-boom cohort as well as the higher rates of substance use observed within this group (Han et al., 2009; Johnson & Gerstein, 1998; Koenig et al., 1994). There is increasing concern regarding the consequences of AUD on the central nervous system in older adults (Dowling et al., 2008). A greater understanding of the effects of aging in the context of AUD is critically important, as findings may provide additional insight into brain structure and function, both of which are susceptible to age- and alcohol-related changes.

Normal aging is associated with ongoing gray and white matter neurostructural changes that appear to follow an anterior–posterior gradient, wherein frontal regions are first and most affected by the aging process, followed by changes to gray and white matter in posterior regions (Gunning-Dixon et al., 2009; Head et al., 2004; Jernigan et al., 2001; Raz & Rodrigue, 2006; Raz et al., 2005; Resnick et al., 2003; Salat et al., 2005; Sullivan & Pfefferbaum, 2007; Sullivan et al., 2010; Tisserand et al., 2004). White matter microstructure within prefrontal pathways and the anterior corpus callosum is particularly affected by increasing age in adults (Head et al., 2004; Salat et al., 2005; Sullivan & Pfefferbaum, 2007; Sullivan et al., 2010). Coinciding with these brain changes are cognitive declines observed in aging, including slowed processing speed (Finkel et al., 2007; Salthouse, 2000) and reductions in performance on tests of executive functions (Fisk & Sharp, 2004; Greenwood, 2000; Jurado & Rosselli, 2007; Phillips & Henry, 2008). AUD is also associated with cognitive slowing and reduced executive functions (Davies et al., 2005; Oscar-Berman & Marinković, 2007) in both early and prolonged abstinence (Stavro et al., 2013). In addition, abnormal frontal lobe structures are well documented in long-term alcoholics (Fein et al., 2002; Jernigan et al., 1991; Kubota et al., 2001; Pfefferbaum et al., 1992).

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) has advanced our ability to investigate age- and AUD-associated changes in cerebral white matter. DTI is sensitive to the movement of water molecules and yields measures such as fractional anisotropy (FA) that describe intravoxel directional coherence of water molecules and provides a proxy measure of white matter structural integrity (Le Bihan et al., 2001; Pierpaoli & Basser, 1996). Thus, higher FA values are thought to reflect better white matter integrity. Reductions in FA have been associated with the diagnosis and duration of AUD, cognitive performance, and response to treatment (Harris et al., 2008; Moeller et al., 2005; Pfefferbaum & Sullivan, 2005; Pfefferbaum et al., 2000, 2006a, 2006b, 2009; Schulte et al., 2005; Sorg et al., 2012; Yeh et al., 2009).

DTI diffusivity measures such as axial diffusivity (AD) and radial diffusivity (RD) are used to further describe changes in white matter integrity. AD refers to the amount of water movement along the primary direction of diffusion, and reductions in AD are thought to relate to axonal damage (Song et al., 2003, 2005). RD describes the average diffusion along the two axes orthogonal to the primary diffusion direction, and increases in RD are associated with increased interstitial water movement, possibly reflecting a reduction in myelin integrity (Song et al., 2003, 2005). Studies of RD suggest myelin compromise in both aging and AUD (Burzynska et al., 2010; Penke et al., 2010; Pfefferbaum et al., 2009; Yeh et al., 2009). Some neuroimaging studies have shown Age × AUD interactions on both brain volume and white matter integrity (Pfefferbaum et al., 1992, 2006a). In a prior DTI study, greater age-related reductions in microstructural integrity were found in adults with AUD, but the analysis was limited to the corpus callosum (Pfefferbaum et al., 2006a).

Given the predilection of the frontal lobes to age-related white matter changes, coupled with frontal lobe susceptibility to AUD-related decrements, we sought to broaden the scope to include extracallosal regions. Specifically, we hypothesized that the greatest decrements in white matter integrity as they relate to aging and AUD may be found in regions other than the corpus callosum, especially in frontal regions. Therefore, the current study attempts to investigate possible Age × AUD interactions within frontal white matter regions in middle-aged participants (ages 31–64). We proposed that the presence of AUD would moderate the relationship between aging and white matter integrity such that FA would be more strongly negatively associated with age in the frontal white matter regions of the AUD group when compared with an age-matched control sample. Furthermore, we expected to find associations between white matter integrity and tests of processing speed and executive functions, as these cognitive domains are sensitive to changes in frontal white matter integrity (Madden et al., 2004; Salami et al., 2012; Vernooij et al., 2009), and they have been shown to be negatively affected in both aging and AUD.

Method

Participants

Institutional review board approval for this study was obtained from the University of California, San Diego, and the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System (VAS-DHS). Participants (N = 72) were 44 recently detoxified persons with AUD undergoing inpatient treatment for AUD at the VASDHS Alcohol and Drug Treatment Program (age range: 31–64 years; 98% male) and 28 non-AUD, healthy controls (age range: 33–64 years; 96% male). AUD participants were approached after their treatment intake and were provided with details regarding the purpose of the study and compensation amount. All AUD participants who provided full consent for study inclusion met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 2000), criteria for alcohol dependence based on a Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV administered by trained research psychiatrists at the VASDHS Alcohol Research Center, and had consumed at least the equivalent of 560 g of pure ethanol each week for the most recent 5 years (Grant et al., 1979). The control participants were recruited from advertisements in the local community and did not meet criteria for AUD or any other DSM-IV Axis I disorder.

Exclusionary criteria included a DSM-IV diagnosis of substance abuse (other than alcohol) disorder in the preceding 5 years, a history of a diagnosed neurological disorder unrelated to AUD (e.g., multiple sclerosis), lifetime history of head injury with loss of consciousness exceeding 15 minutes, current or past diagnosis of a major medical disorder that may interfere with cognitive functioning (e.g., cirrhosis of the liver, cerebrovascular disease, and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus), and major mental illness such as psychotic disorder or bipolar disorder or hospitalization for a psychiatric condition that preceded the onset of the AUD.

All subjects underwent a structured interview to gather information on history of drug use, history of mild head trauma, smoking status, family history of AUD, and estimated lifetime history of alcohol consumption via Timeline Followback (Adams et al., 1981; Sobell et al., 1988). An alcoholic beverage was considered to have approximately 12.5 g of pure ethanol and was equivalent to the following: (a) one 12-oz. can of beer, (b) 4 oz. of wine, or (c) 1.5 oz. of distilled spirits. During the standard course of inpatient treatment, regular monitoring of blood and urine for the presence of alcohol was performed to ensure sobriety before magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Participants were also administered the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, 1978). AUD participants received MRI scanning while undergoing inpatient treatment and were scanned and tested after a minimum of 2 weeks of sobriety to minimize the effects of acute detoxification.

Measures

Imaging.

DTI data were obtained via a General Electric (Milwaukee, WI) Echospeed LX 1.5T scanner located at the VASDHS using a single-shot, stimulated-echo sequence with spiral acquisition (echo time [TE] = 100 ms, repetition time [TR] = 6,000 ms, slice thickness = 3.8 mm, field of view = 240 mm, and in-plane resolution = 3.75 mm × 3.75 mm). Diffusion data were acquired in 42 directions, with a b value of 1,745 s/mm2. A single, non–diffusion-weighted (b = 0) image was also acquired. For each direction and b value, four identical acquisitions were performed and averaged.

Image processing.

Tools from the Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain Software Library (FSL; Smith et al., 2004; www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl) were used for image processing. Each volume was visually inspected for quality during each image-processing stage (e.g., motion, artifact). Motion and eddy current artifacts were corrected using an affine registration to the non–diffusion-weighted volume (FSL’s eddy_correct tool) and were evaluated again for image quality. A data set was not used if there was poor image quality due to motion or artifact that could not be adequately corrected via FSL tools (five scans were excluded from the analysis based on quality). FSL tools were used to remove nonbrain voxels (Brain Extraction Tool; Smith, 2002) and solve the diffusion tensor (dtifit; Basser & Jones, 2002). AD was defined as the amount of diffusion corresponding to the principal diffusion direction (AD = λ1; Song et al., 2003), and RD was defined as the average of the two eigenvalues orthogonal to the principal diffusion direction [RD = (λ2 + λ3) / 2; Song et al., 2003].

Diffusion tensor imaging data analyses.

Region of interest (ROI) placement was guided by a multistep process. The Tract-Based Spatial Statistics (TBSS; Smith et al., 2006) algorithm was used to align all FA images to a standard space as well as to identify those fiber tracts common to all participants (see Smith et al., 2006, for a complete description). An FA threshold of .20 was applied to the mean skeleton to maintain strong tract correspondence across subjects and reduce partial voluming effects by omitting voxels that border gray matter or cerebrospinal fluid (Smith et al., 2006). This method produced 72 aligned FA, AD, and RD skeletons with voxel values unique to each participant.

ROIs were derived from the ICBM-DTI-81 Johns Hopkins University white matter labels atlas available within FSL (http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/data/atlas-descriptions.html#wm; Mori et al., 2008). White matter skeleton ROIs with connections to the prefrontal cortex included the anterior corona radiata (ACR), genu of the corpus callosum (CC), anterior limb of the internal capsule (AIC), and external capsule (EC). ROIs with some frontal connections included the body of the CC, fornix, superior corona radiata (SCR), uncinate fasciculus, and cingulum bundle. More posterior ROIs that were not expected to demonstrate early Age × AUD interactions included the posterior limb of the internal capsule (PIC), superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF), sagittal stratum (SS), posterior corona radiata (PCR), splenium of the CC, and posterior thalamic radiation (PTR). Mean FA, RD, and AD values for the ROIs were extracted for each subject and exported to SPSS Version 19 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) for statistical analysis.

Neuropsychological assessment

Participants completed a neuropsychological test battery administered by a trained psychometrist before the MRI procedure. The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–III (WAIS-III; Wechsler, 1997) Vocabulary subtest T scores—correcting for age, gender, education, and ethnicity (Heaton et al., 2004)—were used to estimate premorbid Verbal IQ (Wechsler, 1997). Tests of processing speed included the Trail Making Test–A (TMT-A; Army Individual Test Battery, 1944) and the WAIS-III Digit-Symbol Coding subtest (Wechsler, 1997). Tests of executive function included number of errors on the Halstead Category Test (Reitan & Wolfson, 1993) and a discrepancy score calculated by subtracting TMT-A time from Trail Making Test–B time (TMT-B; Lezak et al., 2004). All scores were converted to z scores based on the mean and standard deviation of the control sample. Z score values were inverted where necessary such that higher values indicate better performance. Composite z scores were calculated as the average z score of the tests in each domain.

Data analysis

Pearson correlations were performed across all ROIs within each group to test for zero-order associations between age and regional DTI values. Next, hierarchical multiple regression was used to test for the interactions between age and AUD status on DTI values (i.e., FA, AD, and RD) within those regions that demonstrated correlations with age. The first level of the hierarchical regression analysis included demographic and nonalcohol substance use variables that significantly differed by group (i.e., years of education, current reported number of cigarettes smoked per day, WAIS-III Vocabulary T score, and BDI total scores; Table 1). Age and AUD status (i.e., AUD vs. control) were entered in the second level, and the Age × AUD interaction term was entered in the third level. In regions with significant Age × AUD interactions, follow-up regression analyses were performed on RD and AD to inform the direction of the change in diffusion (i.e., whether the FA change is attributable to diffusion changes perpendicular or parallel to the apparent main diffusion direction). False discovery rate (FDR; Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995) was used for type I error correction with FDR < .05.

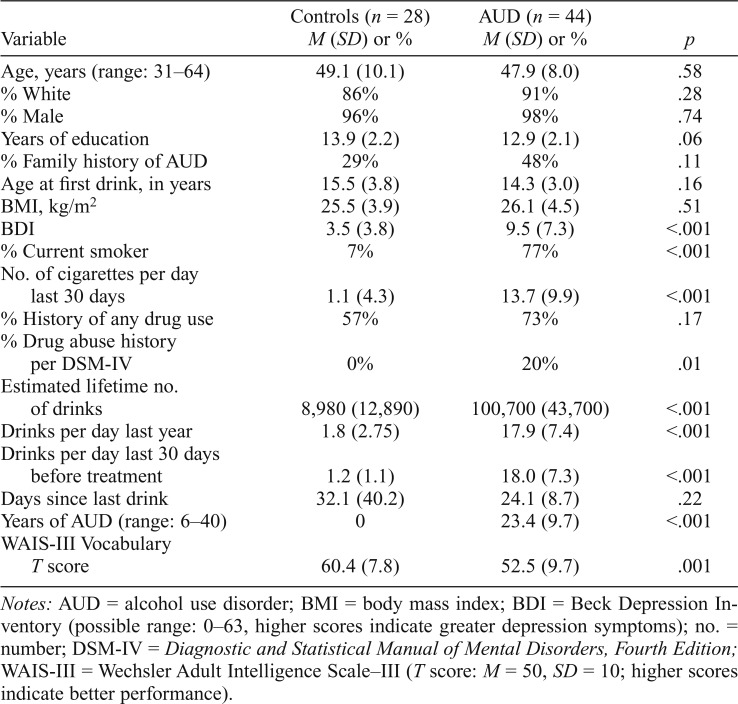

Table 1.

Demographics, alcohol use characteristics, and neuropsychological testing

| Variable | Controls (n = 28) M (SD) or % | AUD (n = 44) M (SD) or % | p |

| Age, years (range: 31–64) | 49.1 (10.1) | 47.9 (8.0) | .58 |

| % White | 86% | 91% | .28 |

| % Male | 96% | 98% | .74 |

| Years of education | 13.9 (2.2) | 12.9 (2.1) | .06 |

| % Family history of AUD | 29% | 48% | .11 |

| Age at first drink, in years | 15.5 (3.8) | 14.3 (3.0) | .16 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.5 (3.9) | 26.1 (4.5) | .51 |

| BDI | 3.5 (3.8) | 9.5 (7.3) | <.001 |

| % Current smoker | 7% | 77% | <.001 |

| No. of cigarettes per day | |||

| last 30 days | 1.1 (4.3) | 13.7 (9.9) | <.001 |

| % History of any drug use | 57% | 73% | .17 |

| % Drug abuse history | |||

| per DSM-IV | 0% | 20% | .01 |

| Estimated lifetime no. of drinks | 8,980 (12,890) | 100,700 (43,700) | <.001 |

| Drinks per day last year | 1.8 (2.75) | 17.9 (7.4) | <.001 |

| Drinks per day last 30 days before treatment | 1.2 (1.1) | 18.0 (7.3) | <.001 |

| Days since last drink | 32.1 (40.2) | 24.1 (8.7) | .22 |

| Years of AUD (range: 6–40) | 0 | 23.4 (9.7) | <.001 |

| WAIS-III Vocabulary | |||

| T score | 60.4 (7.8) | 52.5 (9.7) | .001 |

Notes: AUD = alcohol use disorder; BMI = body mass index; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory (possible range: 0–63, higher scores indicate greater depression symptoms); no. = number; DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; WAIS-III = Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III (T score: M = 50, SD = 10; higher scores indicate better performance).

Group comparisons of the neuropsychological domain scores were conducted using analysis of covariance correcting for age, years of education, current reported number of cigarettes smoked per day, WAIS-III Vocabulary T score, and BDI total scores. Within the AUD group, partial correlations were performed to test associations among the FA and diffusivity values from regions with significant Age × AUD interactions, neuropsychological composite scores, and alcohol use variables.

Results

Diffusion tensor imaging associations with age

Age was negatively correlated with FA in 15 of the 24 ROIs in the AUD group (n = 44), whereas no significant correlations were found between age and FA in the control group (n = 28; Table 2). In the AUD group, RD positively correlated with age in 12 ROIs, with no significant correlations within the control group after FDR correction. Age was positively correlated with AD in 8 ROIs in the AUD group and 2 ROIs in the control group.

Table 2.

Zero-order correlations between regional DTI values and age for controls and AUD

| Region | FA |

RD |

AD |

|||

| Control (n = 28) | AUD (n = 44) | Control (n = 28) | AUD (n = 44) | Control (n = 28) | AUD (n = 44) | |

| Anterior | ||||||

| ACR L | -.05 | -.59* | .18 | .62* | .20 | .42* |

| ACR R | -.03 | -.55* | .29 | .54* | .40 | .20 |

| Genu CC | -.10 | -.47* | .26 | .56* | .49 | .60* |

| AIC L | .06 | -.51* | -.18 | .41* | -.11 | .06 |

| AIC R | .16 | -.41* | -.01 | .00 | .06 | -.15 |

| EC L | .04 | -.26 | .30 | .28 | .54* | .24 |

| EC R | -.19 | -.38* | .46 | .41* | .43 | .23 |

| Body CC | -.16 | -.47* | .37 | .56* | .42 | .36 |

| Fornix | -.30 | -.64* | .42 | .63* | .42 | .56* |

| SCR L | -.13 | -.37* | .23 | .55* | .23 | .36* |

| SCR R | -.35 | -.15 | .36 | .42* | .05 | .37* |

| Uncinate L | .07 | .07 | .03 | -.02 | .10 | .16 |

| Uncinate R | -.02 | -.12 | .14 | -.06 | .16 | -.02 |

| Cingulum L | .15 | -.33* | .17 | .32 | .46 | -.03 |

| Cingulum R | -.01 | -.39* | .16 | .29 | .16 | -.11 |

| PIC L | .03 | -.29 | -.20 | .21 | -.22 | -.09 |

| PIC R | -.12 | -.18 | -.05 | .06 | -.33 | -.14 |

| SLF L | .18 | -.17 | .00 | .25 | .37 | .27 |

| SLF R | .12 | -.22 | -.11 | .25 | .06 | .25 |

| SS L | -.01 | -.33* | .20 | .41* | .33 | .31* |

| SS R | -.14 | -.39* | .19 | .29 | .17 | .17 |

| PCR L | -.34 | -.06 | .31 | .36* | .19 | .46* |

| PCR R | -.33 | -.07 | .18 | .36* | -.10 | .49* |

| Splenium CC | -.15 | -.33* | .34 | .32 | .57* | .01 |

| PTR L | -.32 | -.19 | .41 | .29 | .45 | .24 |

| PTR R | -.01 | -.46* | .06 | .09 | .16 | -.15 |

| Posterior | ||||||

Notes: DTI = diffusion tensor imaging; AUD = alcohol use disorder; FA = fractional an-isotropy; RD = radial diffusivity; AD = axial diffusivity; ACR = anterior corona radiata; L = left; R = right; CC = corpus callosum; AIC = anterior internal capsule; EC = external capsule; SCR = superior corona radiata; PIC = posterior internal capsule; SLF = superior longitudinal fasciculus; SS = sagittal stratum; PCR = posterior corona radiata; PTR = posterior thalamic radiation.

False discovery rate p-corrected < .05.

Age × Alcohol Use Disorder interaction: Fractional anisotropy

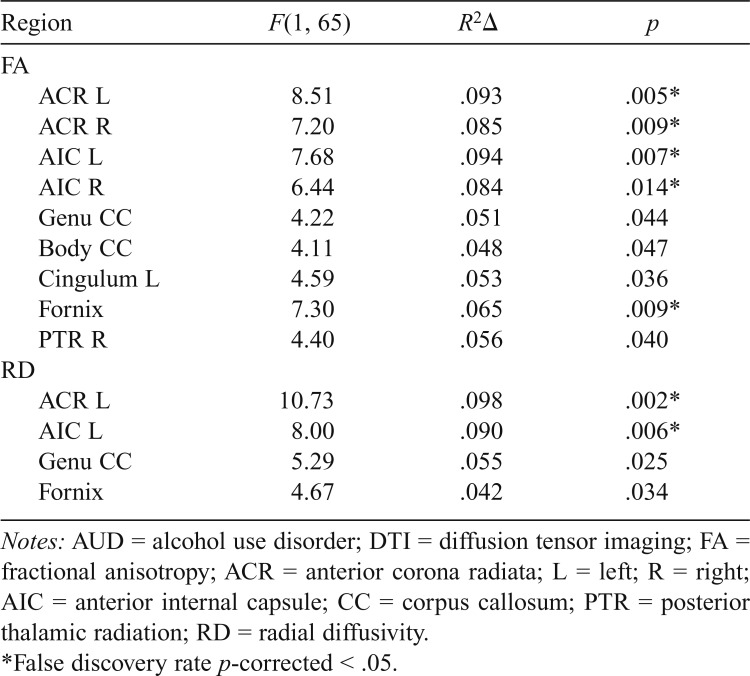

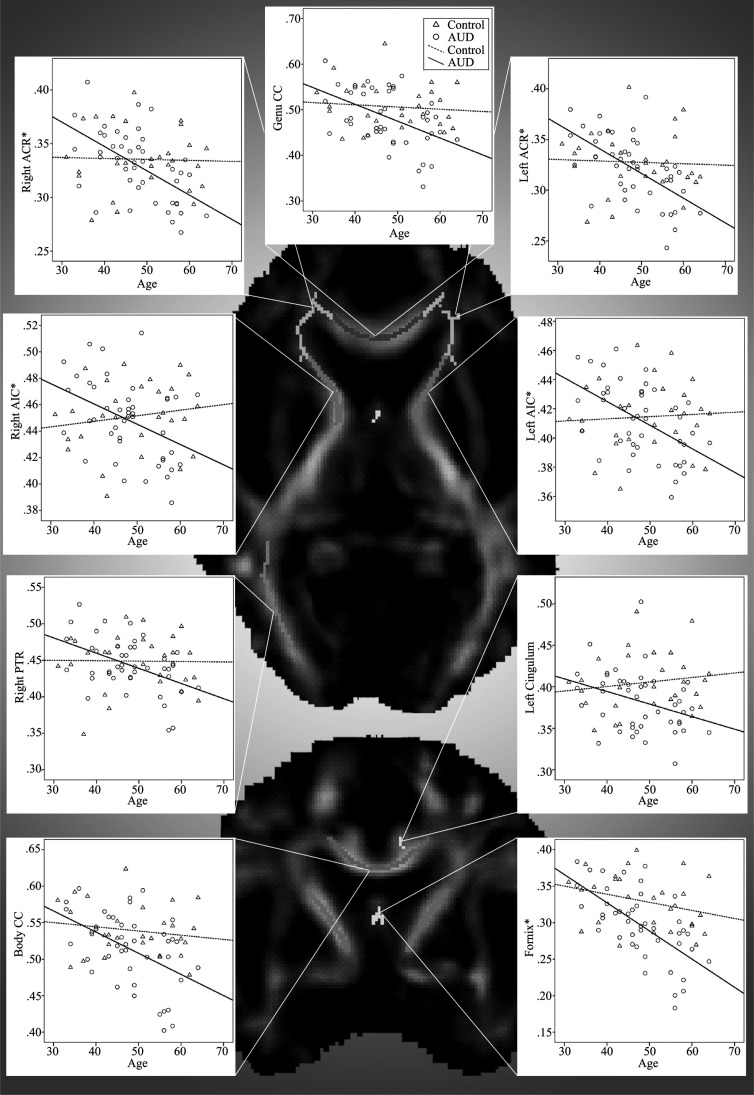

Hierarchical multiple regression analyses were then conducted to test for significant Age × AUD interactions. Significant Age × AUD interactions for FA values adjusting for current reported number of cigarettes smoked per day, WAIS-III Vocabulary T score, and BDI total scores are shown in Table 3. Significant interactions were found in the left and right ACR, left and right AIC, genu and body of the CC, left cingulum bundle, fornix, and right PTR. No other interactions reached significance (all ps > .05). For each interaction, age was significantly negatively correlated with FA in the AUD group, whereas age and FA were not correlated in the control group (Figure 1). Interactions in the ACR, AIC, and fornix remained significant at p-corrected < .05 after multiple comparison corrections using FDR, with trends (p-corrected < .10) in the genu CC, body CC, and right PTR.

Table 3.

Significant interactions between age and AUD status for regional DTI values

| Region | F(1, 65) | R2Δ | p |

| FA | |||

| ACR L | 8.51 | .093 | .005* |

| ACR R | 7.20 | .085 | .009* |

| AIC L | 7.68 | .094 | .007* |

| AIC R | 6.44 | .084 | .014* |

| Genu CC | 4.22 | .051 | .044 |

| Body CC | 4.11 | .048 | .047 |

| Cingulum L | 4.59 | .053 | .036 |

| Fornix | 7.30 | .065 | .009* |

| PTR R | 4.40 | .056 | .040 |

| RD | |||

| ACR L | 10.73 | .098 | .002* |

| AIC L | 8.00 | .090 | .006* |

| Genu CC | 5.29 | .055 | .025 |

| Fornix | 4.67 | .042 | .034 |

Notes: AUD = alcohol use disorder; DTI = diffusion tensor imaging; FA = fractional anisotropy; ACR = anterior corona radiata; L = left; R = right; AIC = anterior internal capsule; CC = corpus callosum; PTR = posterior thalamic radiation; RD = radial diffusivity.

False discovery rate p-corrected < .05.

Figure 1.

Zero-order correlations between age and regional fractional anisotropy (FA) by group shown on a representative FA image. AUD = alcohol use disorder; ACR = anterior corona radiata; CC = corpus callosum; AIC = anterior internal capsule; PTR = posterior thalamic radiation. *False discovery rate p-corrected < .05, otherwise p-corrected < .10.

Because alcohol use variables such as lifetime alcohol consumption tend to be correlated with age, as was the case in our AUD sample (r = .47, p = .001), we ran separate hierarchical multiple regression models to account for AUD severity within those regions showing a significant interaction. With the inclusion of estimated lifetime number of drinks as a predictor at the base level of the model, interactions within most anterior regions remained significant, including the left ACR, F(1, 64) = 5.93, p = .02, R2Δ = .06; right ACR, F(1, 64) = 5.41, p = .02, R2Δ = .06; left AIC, F(1, 64) = 4.92, p = .03, R2Δ = .06; right AIC, F(1, 64) = 4.38, p = .04, R2Δ = .06; and fornix, F(1, 64) = 5.70, p = .02, R2Δ = .05. In a separate model that accounted for recent drinking (i.e., number of drinks in the past 30 days) and did not include lifetime history of alcohol consumption, all interactions remained significant except for the right PTR (p > .05), suggesting that findings were robust to recent substance use.

Age × AUD interaction: Radial diffusivity and axial diffusivity

Follow-up hierarchical regression analyses with RD and AD were performed within those regions showing significant Age × FA interactions. Regions with significant interactions for RD are shown in Table 3 and included the left ACR, left AIC, genu CC, and the fornix. Interactions in the left ACR and left AIC remain significant after FDR corrections (p-corrected < .05), whereas trends remained (p-corrected < .10) in the genu and the fornix. In each interaction, age was associated with greater RD in AUD compared with controls. After adjusting for estimated lifetime number of drinks, interactions in the left ACR, F(1, 64) = 9.79, p < .01, R2Δ = .09, and left AIC, F(1, 64) = 5.79, p < .05, R2Δ = .07, remained significant. No interactions for the AD values reached significance in any ROI.

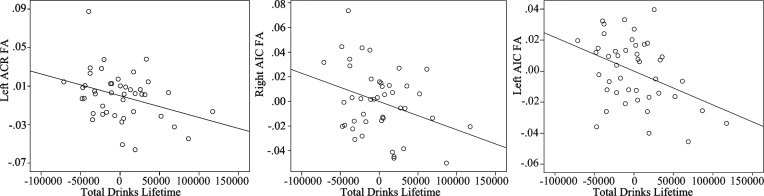

Diffusion tensor imaging associations with alcohol use disorder and alcohol use characteristics

Regional FA, RD, or AD values were not associated with AUD status (all ps > .10) in the hierarchical regression analyses. Partial correlations were conducted in the AUD group (n = 44) to determine if white matter integrity within those regions showing a significant Age × AUD interaction was sensitive to cumulative and recent alcohol consumption within the AUD group independent of age and recent cigarette use. Age was included as a covariate in each partial correlation (also adjusting for cigarette use) because lifetime number of drinks was significantly correlated with number of years lived (r = .47, p = .001). Estimated total lifetime number of drinks significantly correlated with FA in the left ACR (r = -.34, p = .03), right AIC (r = -.33, p = .04), and left AIC (r = -.40, p = .009) (Figure 2), with trends in the genu CC (r = -.29, p = .07) and body CC (r = -.27, p = .09) each showing lower FA values with greater cumulative drinks. Number of drinks in the 30 days preceding treatment significantly correlated only with the right ACR FA (r = -.32, p = .04). RD significantly correlated with estimated drinks in the past year in the right ACR (r = .31, p = .04), fornix (r = .33, p = .03), and genu CC (r = .31, p < .05). Years of AUD did not correlate with FA or RD after adjusting for age and cigarette use. No significant partial correlations were found between substance use variables and AD values for the AUD group.

Figure 2.

Partial correlations between frontal fractional anisotropy (FA) and lifetime alcohol consumption in the alcohol use disorder (AUD) group. Scatter plots show significant associations between estimated lifetime number of drinks and FA in the AUD group for three frontal white matter regions of interest (ROIs), with the effects of age and current cigarette use adjusted for. ACR = anterior corona radiata, AIC = anterior internal capsule.

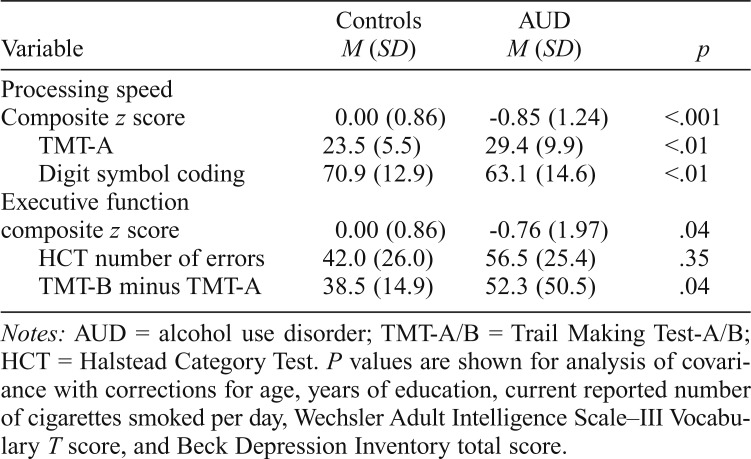

Neuropsychological testing: Group comparisons

Results from analysis of covariance—adjusting for age, years of education, current reported number of cigarettes smoked per day, WAIS-III Vocabulary T score, and BDI total scores—found that the AUD group had significantly lower processing speed composite score, F(1, 65) = 12.46, p < .001,  , and executive functioning composite score, F(1, 65) = 4.29, p = .04,

, and executive functioning composite score, F(1, 65) = 4.29, p = .04,  , compared with controls (Table 4).

, compared with controls (Table 4).

Table 4.

Neuropsychological domains composite scores and raw tests scores

| Variable | Controls M (SD) | AUD M (SD) | p |

| Processing speed | |||

| Composite z score | 0.00 (0.86) | -0.85 (1.24) | <.001 |

| TMT-A | 23.5 (5.5) | 29.4 (9.9) | <.01 |

| Digit symbol coding | 70.9 (12.9) | 63.1 (14.6) | <.01 |

| Executive function | |||

| composite z score | 0.00 (0.86) | -0.76 (1.97) | .04 |

| HCT number of errors | 42.0 (26.0) | 56.5 (25.4) | .35 |

| TMT-B minus TMT-A | 38.5 (14.9) | 52.3 (50.5) | .04 |

Notes: AUD = alcohol use disorder; TMT-A/B = Trail Making Test-A/B; HCT = Halstead Category Test. P values are shown for analysis of covariance with corrections for age, years of education, current reported number of cigarettes smoked per day, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–III Vocabulary T score, and Beck Depression Inventory total score.

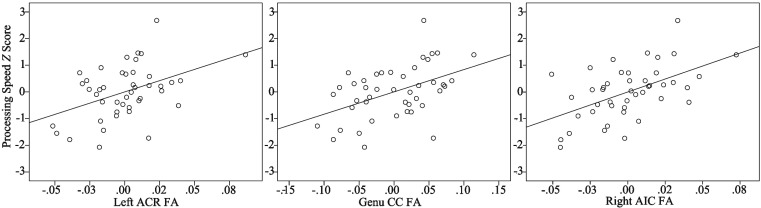

Associations among regional diffusion tensor imaging values and neuropsychological domain composites within alcohol use disorder

Within the AUD group (n = 44), partial correlations were run between FA values in regions showing significant Age × AUD interactions and neuropsychological test scores to elucidate possible behavioral consequences of poorer white matter integrity for heavy drinkers. Partial regression was used in each analysis adjusting for age, years of education, current reported number of cigarettes smoked per day, WAIS-III Vocabulary T score, and BDI total score. There were no significant associations between FA and executive functioning composite scores. The processing speed composite showed significant positive correlations with FA (i.e., lower FA was associated with slower processing speed; Figure 3) within the left ACR (r = .44, p < .01), right ACR (r = .43, p < .01), left AIC (r = .42, p < .01), right AIC (r = .53, p < .001), and genu CC (r = .47, p < .01) and body of the CC (r = .34, p < .05). Correlations remained significant for all but the body of the CC after FDR corrections (p-corrected < .05). Only RD in the genu CC significantly correlated with processing speed (r = -.42, p < .01), although this did not survive multiple comparison correction. No other regions significantly correlated with either domain score in either RD or AD.

Figure 3.

Associations between frontal fractional anisotropy (FA) and processing speed in the alcohol use disorder group. Figures show partial correlation analysis depicting positive associations between processing speed z scores and frontal FA values adjusting for age, years of education, current reported number of cigarettes smoked per day, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–III Vocabulary T score, and Beck Depression Inventory total scores. ACR = anterior corona radiata; CC = corpus callosum; AIC = anterior internal capsule.

Discussion

In this study, we used DTI to investigate whether the relationship between age and white matter microstructure differs between persons with AUD and controls in a middle-aged adult sample. Our findings align with others that suggest the neurotoxic effects of chronic heavy alcohol use may exacerbate age-related brain changes in white matter (Pfefferbaum et al., 2006a). We expand on the findings of Pfefferbaum et al. (2006a) by demonstrating an anterior–posterior gradient with anterior frontal white matter being particularly affected by age in the AUD group (Burzynska et al., 2010; Gunning-Dixon et al., 2009; Raz & Rodrigue, 2006).

In our AUD sample, both the amount of alcohol use and age appear to affect frontal white matter microstructure. Lower frontal white matter integrity was associated with higher levels of estimated lifetime alcohol consumption. Moreover, the age effect on white matter microstructure was not simply a function of heavy alcohol use, because it remained significant even after adjusting for cumulative lifetime alcohol consumption. Together, these findings suggest that disruption of frontal white matter microstructure related to the cumulative effects of alcohol consumption may intensify the effects of the neurobiological mechanisms responsible for the aging process. In addition, it is possible that slower alcohol metabolism in older adults compared with younger drinkers results in prolonged effects of alcohol that may further contribute to the observed age-related increased vulnerability (Meier & Seitz, 2008).

The lack of a significant association between age and white matter microstructure in the control sample may be because we sampled an age range that corresponds to a plateau in the nonlinear associations between age and brain structure. Some DTI and volumetric studies indicate leveling off of changes during middle adulthood followed by a more rapid decline in later years (Hasan et al., 2009; Malykhin et al., 2011; see Raz & Rodrigue, 2006, for review), although other studies have not found this pattern (Sullivan & Pfefferbaum, 2007). This apparent stability in white matter seen in middle age may reflect a balance between ongoing myelination (Bartzokis, 2004) and regressive brain changes that occurs into middle adulthood (Jernigan & Fennema-Notestine, 2004). Neurotoxic factors that may perturb that balance, such as chronic excessive alcohol consumption, could contribute to a more rapid and/or earlier onset of age-related changes as suggested in the present study.

The diffusivity analyses suggest that local myelin compromise (as indexed by RD) may be driving the observed decrements in frontal white matter integrity and align with other reports of myelin compromise in aging and AUD (Bartzokis, 2004; Lewohl et al., 2001; Wiggins et al., 1988). It is noted that such interpretations of RD are tenuous. Neuronal pathology and highly complex fiber structures may alter the relationship between the primary diffusion direction and the true fiber orientation, thus obscuring tentative associations between RD and myelin integrity (Wheeler-Kingshott & Cercignani, 2009). Additional research on diffusivity measures and their relationships with underlying tissue structure is needed before RD may be definitively related to myelin integrity.

Our findings comport with others that link decrements in processing speed to reductions in frontal white matter integrity (Madden et al., 2004; Salami et al., 2012; Vernooij et al., 2009). Thus, the reduced processing speed in AUD observed in this study may be related to disruption of white matter pathways within the neural networks responsible for the speeded integration of the cognitive processes engaged in tests of processing speed (e.g., visual scanning and attention, response speed, incidental learning, and visuomotor coordination) (Lezak et al., 2004; Schulte et al., 2005). Although decrements in executive functions were found in the AUD compared with controls, executive functions did not significantly correlate with frontal white matter microstructure. It is possible that the disruption in neural signal propagation that may have affected the processing speed scores was not great enough to contribute to the observed reductions in executive functions. Consistent with this possibility, the executive function measures used in this study minimized the contribution of processing speed and, as such, were more direct measures of concept formation and cognitive set-shifting and may have been related to variations in cortical gray matter not assessed in this study (Lezak et al., 2004).

Our groups were not well matched on cigarette use, with the AUD group smoking more than ten times the rate of controls. As the emphasis of the present work is on the effect of AUD in aging, we sought to mitigate the effect of smoking via inclusion in the regression models and in-group comparisons. In doing so, group differences in AUD and the Age × AUD interaction may have been attenuated. When current reported number of cigarettes smoked per day is excluded from the regression model, significant group differences in FA are found in the genu CC, fornix, and left and right cingulum bundles, although these effects do not survive multiple comparison correction. Similarly, with removal of current cigarette use, the results of Age × AUD interactions are changed only in the effect size (slightly greater effects). Because cigarette use can affect white matter integrity (Wang et al., 2008), further study on this effect and how it may also interact with the aging process is warranted.

There are other limitations of note in the present study. First, the AUD group had a higher frequency of past DSM-IV criteria for drug abuse than the controls, although groups did not significantly differ with respect to the proportion of participants reporting any past use. When those nine AUD participants with a history of drug abuse were removed from the analysis, the pattern of findings remained unchanged. The AUD group comprised treatment-seeking veterans; thus, the findings may not necessarily extend to non–treatment-seeking AUD or nonveterans. No controls met the criteria for a DSM-IV Axis I disorder, and we screened out AUD participants who met the criteria for major mental illness such as psychotic disorder and bipolar disorder. However, it is possible that groups differed with respect to other psychiatric symptoms (e.g., anxiety) and that some of the observed effects may be related to differing rates of mental illness between the AUD group and controls. Moreover, because this was a predominantly male sample, the findings may not generalize to women. DTI is highly sensitive to artifacts introduced by head motion in the scanner. Although attempts were made to evaluate and mitigate these effects during image acquisition and processing, it is possible that motion artifacts may have affected the data quality. Also, the age range presented here is restricted to middle age, and we were unable to investigate Age × AUD interactions in age ranges where we would expect to see more declines with normal aging (i.e., >65 years). An added limitation is the cross-sectional nature of the present study. Future studies should explore Age × AUD interactions using a broader age span, in a longitudinal design to investigate the maintenance of this effect over time and explore the potential neural recovery associated with sobriety. Finally, the results of this study described recently detoxified patients with AUD, and so it is not known whether the age-associated frontal white matter integrity decline persists with long-term abstinence.

Conclusions

In healthy adults, great age-related alterations in white matter microstructure are not expected in middle age (Malykhin et al., 2011), potentially owing to a relative balance in progressive and regressive factors during that time (Jernigan & Fennema-Notestine, 2004). In this study, we found that AUD might disrupt this balance and contribute to advanced age-related alterations in frontal white matter microstructure. These premature neurostructural changes may contribute to observed reductions in information processing speed. These findings point to possible atypical neurostructural aging trajectories for persons with AUD and, in the context of the increasing number of older adults with substance use disorders, encourage continued research inquiry in this growing population.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge June Allen for her invaluable assistance throughout the data-collection phase of this project.

Footnotes

This project was supported by a MERIT grant from the Veterans Affairs Medical Research Service awarded to Igor Grant.

References

- Adams K. M., Grant I., Carlin A. S., Reed R. Cross-study comparisons of self-reported alcohol consumption in four clinical groups. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1981;138:445–449. doi: 10.1176/ajp.138.4.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, text revision. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Army Individual Test Battery. Manual of directions and scoring. Washington, DC: War Department, Adjutant General’s Office; 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Bartzokis G. Age-related myelin breakdown: A developmental model of cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging. 2004;25:5–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.03.001. author reply 49–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basser P. J., Jones D. K. Diffusion-tensor MRI: Theory, experimental design and data analysis—A technical review. NMR in Biomedicine. 2002;15:456–467. doi: 10.1002/nbm.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A. T. Depression inventory. Philadelphia, PA: Center for Cognitive Therapy; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Burzynska A. Z., Preuschhof C., Bäckman L., Nyberg L., Li S. C., Lindenberger U., Heekeren H. R. Age-related differences in white matter microstructure: Region-specific patterns of diffusivity. NeuroImage. 2010;49:2104–2112. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies S. J. C., Pandit S. A., Feeney A., Stevenson B. J., Kerwin R. W., Nutt D. J., Lingford-Hughes A. Is there cognitive impairment in clinically ‘healthy’ abstinent alcohol dependence? Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2005;40:498–503. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling G. J., Weiss S. R., Condon T. P. Drugs of abuse and the aging brain. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:209–218. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fein G., Di Sclafani V., Cardenas V. A., Goldmann H., Tolou-Shams M., Meyerhoff D. J. Cortical gray matter loss in treatment-naïve alcohol dependent individuals. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002;26:558–564. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel D., Reynolds C. A., McArdle J. J., Pedersen N. L. Age changes in processing speed as a leading indicator of cognitive aging. Psychology and Aging. 2007;22:558–568. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.3.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisk J. E., Sharp C. A. Age-related impairment in executive functioning: Updating, inhibition, shifting, and access. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2004;26:874–890. doi: 10.1080/13803390490510680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant I., Adams K., Reed R. Normal neuropsychological abilities of alcoholic men in their late thirties. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1979;136:1263–1269. doi: 10.1176/ajp.136.10.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood P. M. The frontal aging hypothesis evaluated. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2000;6:705–726. doi: 10.1017/s1355617700666092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunning-Dixon F. M., Brickman A. M., Cheng J. C., Alexopoulos G. S. Aging of cerebral white matter: A review of MRI findings. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2009;24:109–117. doi: 10.1002/gps.2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B., Gfroerer J. C., Colliver J. D., Penne M. A. Substance use disorder among older adults in the United States in 2020. Addiction. 2009;104:88–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris G. J., Jaffin S. K., Hodge S. M., Kennedy D., Caviness V. S., Marinković K., Oscar-Berman M. Frontal white matter and cingulum diffusion tensor imaging deficits in alcoholism. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:1001–1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00661.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan K. M., Kamali A., Iftikhar A., Kramer L. A., Papanicolaou A. C., Fletcher J. M., Ewing-Cobbs L. Diffusion tensor tractography quantification of the human corpus callosum fiber pathways across the lifespan. Brain Research. 2009;1249:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head D., Buckner R. L., Shimony J. S., Williams L. E., Akbudak E., Conturo T. E., Snyder A. Z. Differential vulnerability of anterior white matter in nondemented aging with minimal acceleration in dementia of the Alzheimer type: Evidence from diffusion tensor imaging. Cerebral Cortex. 2004;14:410–423. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton R. K., Miller W., Taylor M. J., Grant I. Revised comprehensive norms for an expanded Halstead-Reitan battery: Demographically adjusted neuropsychological norms for African American and Caucasian adults. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan T. L., Archibald S. L., Fennema-Notestine C., Gamst A. C., Stout J. C., Bonner J., Hesselink J. R. Effects of age on tissues and regions of the cerebrum and cerebellum. Neurobiology of Aging. 2001;22:581–594. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan T. L., Butters N., DiTraglia G., Schafer K., Smith T., Irwin M., Cermak L. S. Reduced cerebral grey matter observed in alcoholics using magnetic resonance imaging. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1991;15:418–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1991.tb00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan T. L., Fennema-Notestine C. White matter mapping is needed. Neurobiology of Aging. 2004;25:37–39. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. A., Gerstein D. R. Initiation of use of alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana, cocaine, and other substances in US birth cohorts since 1919. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:27–33. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurado M. B., Rosselli M. The elusive nature of executive functions: A review of our current understanding. Neuropsychology Review. 2007;17:213–233. doi: 10.1007/s11065-007-9040-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig H. G., George L. K., Schneider R. Mental health care for older adults in the year 2020: A dangerous and avoided topic. The Gerontologist. 1994;34:674–679. doi: 10.1093/geront/34.5.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota M., Nakazaki S., Hirai S., Saeki N., Yamaura A., Kusaka T. Alcohol consumption and frontal lobe shrinkage: Study of 1432 non-alcoholic subjects. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 2001;71:104–106. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.71.1.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bihan D., Mangin J. F., Poupon C., Clark C. A., Pappata S., Molko N., Chabriat H. Diffusion tensor imaging: Concepts and applications. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2001;13:534–546. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewohl J. M., Dodd P. R., Mayfield R. D., Harris R. A. Application of DNA microarrays to study human alcoholism. Journal of Biomedical Science. 2001;8:28–36. doi: 10.1007/BF02255968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak M. D., Howieson D. B., Loring D. W., Hannay H. J., Fischer J. S. Neuropsychological assessment. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Madden D. J., Whiting W. L., Huettel S. A., White L. E., MacFall J. R., Provenzale J. M. Diffusion tensor imaging of adult age differences in cerebral white matter: Relation to response time. NeuroImage. 2004;21:1174–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malykhin N., Vahidy S., Michielse S., Coupland N., Camicioli R., Seres P., Carter R. Structural organization of the prefrontal white matter pathways in the adult and aging brain measured by diffusion tensor imaging. Brain Structure & Function. 2011;216:417–431. doi: 10.1007/s00429-011-0321-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier P., Seitz H. K. Age, alcohol metabolism and liver disease. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 2008;11:21–26. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3282f30564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller F. G., Hasan K. M., Steinberg J. L., Kramer L. A., Dougherty D. M., Santos R. M., Narayana P. A. Reduced anterior corpus callosum white matter integrity is related to increased impulsivity and reduced discriminability in cocaine-dependent subjects: Diffusion tensor imaging. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:610–617. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori S., Oishi K., Jiang H., Jiang L., Li X., Akhter K., Mazziotta J. Stereotaxic white matter atlas based on diffusion tensor imaging in an ICBM template. NeuroImage. 2008;40:570–582. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oscar-Berman M., Marinković K. Alcohol: Effects on neurobehavioral functions and the brain. Neuropsychology Review. 2007;17:239–257. doi: 10.1007/s11065-007-9038-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penke L., Maniega S. M., Murray C., Gow A. J., Hernández M. C. V., Clayden J. D., Deary I. J. A general factor of brain white matter integrity predicts information processing speed in healthy older people. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30:7569–7574. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1553-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum A., Adalsteinsson E., Sullivan E. V. Dysmorphology and microstructural degradation of the corpus callosum: Interaction of age and alcoholism. Neurobiology of Aging. 2006a;27:994–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum A., Adalsteinsson E., Sullivan E. V. Supratentorial profile of white matter microstructural integrity in recovering alcoholic men and women. Biological Psychiatry. 2006b;59:364–372. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum A., Lim K. O., Zipursky R. B., Mathalon D. H., Rosenbloom M. J., Lane B., Sullivan E. V. Brain gray and white matter volume loss accelerates with aging in chronic alcoholics: A quantitative MRI study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1992;16:1078–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb00702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum A., Rosenbloom M., Rohlfing T., Sullivan E. V. Degradation of association and projection white matter systems in alcoholism detected with quantitative fiber tracking. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;65:680–690. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum A., Sullivan E. V. Disruption of brain white matter microstructure by excessive intracellular and extracellular fluid in alcoholism: Evidence from diffusion tensor imaging. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:423–432. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum A., Sullivan E. V., Hedehus M., Adalsteinsson E., Lim K. O., Moseley M. In vivo detection and functional correlates of white matter microstructural disruption in chronic alcoholism. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:1214–1221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips L. H., Henry J. D. Adult aging and executive functioning. In: Anderson V., Jacobs R., Anderson P. J., editors. Executive functions and the frontal lobes: A lifespan perspective. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis; 2008. pp. 57–79. [Google Scholar]

- Pierpaoli C., Basser P. J. Toward a quantitative assessment of diffusion anisotropy. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1996;36:893–906. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz N., Lindenberger U., Rodrigue K. M., Kennedy K. M., Head D., Williamson A., Acker J. D. Regional brain changes in aging healthy adults: General trends, individual differences and modifiers. Cerebral Cortex. 2005;15:1676–1689. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz N., Rodrigue K. M. Differential aging of the brain: Patterns, cognitive correlates and modifiers. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2006;30:730–748. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan R. M., Wolfson D. The Halstead–Reitan neuropsychological test battery: Theory and clinical interpretation. Tucson, AZ: Neuropsychology Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick S. M., Pham D. L., Kraut M. A., Zonderman A. B., Davatzikos C. Longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging studies of older adults: A shrinking brain. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:3295–3301. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03295.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salami A., Eriksson J., Nilsson L. G., Nyberg L. Age-related white matter microstructural differences partly mediate age-related decline in processing speed but not cognition. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2012;1822:408–415. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salat D. H., Tuch D. S., Hevelone N. D., Fischl B., Corkin S., Rosas H. D., Dale A. M. Age-related changes in prefrontal white matter measured by diffusion tensor imaging. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2005;1064:37–49. doi: 10.1196/annals.1340.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse T. A. Aging and measures of processing speed. Biological Psychology. 2000;54:35–54. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(00)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte T., Sullivan E. V., Muller-Oehring E. M., Adalsteinsson E., Pfefferbaum A. Corpus callosal microstructural integrity influences interhemispheric processing: A diffusion tensor imaging study. Cerebral Cortex. 2005;15:1384–1392. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. M. Fast robust automated brain extraction. Human Brain Mapping. 2002;17:143–155. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. M., Jenkinson M., Johansen-Berg H., Rueckert D., Nichols T. E., Mackay C. E., Behrens T. E. J. Tract-based spatial statistics: Voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. NeuroImage. 2006;31:1487–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. M., Jenkinson M., Woolrich M. W., Beckmann C. F., Behrens T. E., Johansen-Berg H., Matthews P. M. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. NeuroImage, 23, Supplement. 2004;1:S208–S219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L. C., Sobell M. B., Leo G. I., Cancilla A. Reliability of a timeline method: Assessing normal drinkers’ reports of recent drinking and a comparative evaluation across several populations. British Journal of Addiction. 1988;83:393–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S. K., Sun S. W., Ju W. K., Lin S. J., Cross A. H., Neufeld A. H. Diffusion tensor imaging detects and differentiates axon and myelin degeneration in mouse optic nerve after retinal ischemia. NeuroImage. 2003;20:1714–1722. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S. K., Yoshino J., Le T. Q., Lin S. J., Sun S. W., Cross A. H., Armstrong R. C. Demyelination increases radial diffusivity in corpus callosum of mouse brain. NeuroImage. 2005;26:132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorg S. F., Taylor M. J., Alhassoon O. M., Gongvatana A., Theilmann R. J., Frank L. R., Grant I. Frontal white matter integrity predictors of adult alcohol treatment outcome. Biological Psychiatry. 2012;71:262–268. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stavro K., Pelletier J., Potvin S. Widespread and sustained cognitive deficits in alcoholism: A meta-analysis. Addiction Biology. 2013;18:203–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2011.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan E. V., Pfefferbaum A. Neuroradiological characterization of normal adult ageing. British Journal of Radiology, 80, Special Issue. 2007;2:S99–S108. doi: 10.1259/bjr/22893432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan E. V., Rohlfing T., Pfefferbaum A. Longitudinal study of callosal microstructure in the normal adult aging brain using quantitative DTI fiber tracking. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2010;35:233–256. doi: 10.1080/87565641003689556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tisserand D. J., van Boxtel M. P., Pruessner J. C., Hofman P., Evans A. C., Jolles J. A voxel-based morphometric study to determine individual differences in gray matter density associated with age and cognitive change over time. Cerebral Cortex. 2004;14:966–973. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernooij M. W., Ikram M. A., Vrooman H. A., Wielopolski P. A., Krestin G. P., Hofman A., Breteler M. M. B. White matter micro-structural integrity and cognitive function in a general elderly population. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:545–553. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. Y., Bakhadirov K., Devous M. D., Sr., Abdi H., McColl R., Moore C., Diaz-Arrastia R. Diffusion tensor tractography of traumatic diffuse axonal injury. Archives of Neurology. 2008;65:619–626. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.5.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler adult intelligence scale-third edition (WAIS-III) San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler-Kingshott C. A., Cercignani M. About “axial” and “radial” diffusivities. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2009;61:1255–1260. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins R. C., Gorman A., Rolsten C., Samorajski T., Ballinger W. E., Jr., Freund G. Effects of aging and alcohol on the biochemical composition of histologically normal human brain. Metabolic Brain Disease. 1988;3:67–80. doi: 10.1007/BF01001354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh P. H., Simpson K., Durazzo T. C., Gazdzinski S., Meyerhoff D. J. Tract-Based Spatial Statistics (TBSS) of diffusion tensor imaging data in alcohol dependence: Abnormalities of the motivational neurocircuitry. Psychiatry Research. 2009;173:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]