Abstract

Introduction:

Local anaesthetic (LA) with highly selective alpha-2 agonist dexmedetomidine has not been evaluated in adductor canal block (ACB) for arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction surgeries. The study evaluates postoperative analgesic effect of ropivacaine with adjuvant dexmedetomidine following postoperative ultrasound-guided ACB.

Methods:

105 randomized subjects received ultrasound-guided ACB using 15 mL of 0.5% ropivacaine, with 0.5 µg kg−1 of dexmedetomidine administered perineurally (Group II), intravenously (Group III) or none (Group I). Primary outcome included 24 hours’ total morphine consumption postoperatively. Secondary outcomes included haemodynamics and adverse effects.

Results:

The postoperative total morphine consumption was significantly reduced till 4 hours in II 0.57 mg (0.98 (0–3)) (p = 0.011) and up to 6 hours in Group III 0.77 mg (1.00 (0–4)) (p = 0.004) compared to Group I. The postoperative total morphine consumption was comparable at 24 hours in Group III 3.57 mg (1.73 (0–8)) and Group II 3.34 mg (1.92 (07)) (p = 1.000). The visual analogue scale (VAS) scores were comparable in all the three groups at all the time intervals studied (p > 0.05). There were no adverse effects observed during the study.

Conclusion:

Use of perineural dexmedetomidine with LA for ACB in the postoperative period resulted in significant reduction in total morphine consumption in initial 4 hours as compared to 6 hours with intravenous (IV) dexmedetomidine.

Keywords: Anterior cruciate ligament, dexmedetomidine, postoperative analgesia, saphenous nerve block

Introduction

Ultrasound-guided (USG) saphenous nerve block in adductor canal with intermittent ropivacaine has been described for providing postoperative analgesia after arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) surgery and significant opioid sparing in initial hours in the intermittent group up to 24 hours had been noticed.1 However, usually the postoperative pain persists for 24–72 hours2 and postoperative analgesia can be prolonged with addition of adjuvants to local anaesthetics (LAs).3 Dexmedetomidine, a highly selective alpha 2 agonist,4 has been used as an adjuvant to LA for prolonging the duration of analgesia provided by LA.5 However, its use as an adjuvant to LA has not been described for prolonging the duration of postoperative analgesia achieved by saphenous nerve block in adductor canal in subjects after ACL surgery. Thus, this study was done to study the effects of dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant to LA for prolonging the duration of postoperative analgesia produced by saphenous nerve block in adductor canal in subjects after ACL surgery. The primary objective of the study included total morphine consumption in 24 hours in the postoperative period. The secondary objectives included postoperative pain relief, haemodynamics and adverse effects.

Methods

Subjects and design

This single-centre, randomized, blinded trial was approved by the institutional ethics committee of the government medical college and hospital in Chandigarh, India via communication No. 2572, dated 20 January 2016, and was prospectively registered at the clinical trial registry in India in 2016. The data are presented in accordance with the CONSORT statement (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing patient selection and randomization.

After taking informed consent, 105 subjects of either sex, having American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I & II, aged between 18 and 60 years, body mass index (BMI) of ⩾20 and ⩽30 kg m−2 and scheduled for ACL reconstruction surgery were enrolled and randomized in three groups between March 2016 and June 2017 (Table 1). Exclusion criteria included a history of substance abuse, peripheral neuropathy, pre-existing bleeding disorders, pregnancy, lactation and infection at the site of block. Subjects having inability in understanding the functioning of patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pumps or visual analogue scale (VAS), having contraindication to study drugs, having haemodynamic instability, hepatic dysfunction and who were on regular chronic pain management drugs for the last 3 months were also excluded from the study.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Variable | Group I (n = 35) | Group II (n = 35) | Group III (n = 35) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 28.40 ± 8.35 | 26.51 ± 5.41 | 26.20 ± 5.67 | 0.33 |

| Sex (male/female), n | 33/2 | 32/3 | 32/3 | 0.87 |

| Weight (kg) | 77.94 (9.33) | 73.66 (10.30) | 76.23 (12.92) | 0.26 |

| Height (cm) | 175 (5.38) | 173.73 (6.44) | 173.27 (6.76) | 0.33 |

| BMI (kg m−2) | 25.37 (2.37) | 24.37 (2.53) | 25.26 (3.52) | 0.28 |

BMI: body mass index.

Values are presented as mean (SD).

After recording baseline values for range of movement (ROM) at knee6 and timed up and go (TUG) tests,7 subjects were explained VAS for pain assessment, where 0 stands for no pain and 10 stands for the worst imaginable pain.

In operating room, standard monitors were attached. After intravenous (IV) cannulation and preloading of 500 mL of 0.9% normal saline, a standard subarachnoid block (SAB) was performed in all the subjects with 3.0 mL of 0.5% heavy bupivacaine at L3–L4 interspace. At the completion of surgery, all subjects received paracetamol 1 g IV prior to shifting into post-anaesthesia care unit (PACU).

Randomization and group allocation

Randomization was done in the postoperative period using computer-generated random number table, and subjects were allocated to one of the three groups of 35 each. Concealment was done with opaque sealed envelopes. Group I (n = 35) received adductor canal block (ACB) with 17 mL of a solution (15 mL of 0.5% ropivacaine plus 2 mL of sterile normal saline to make a final volume of 17 mL) and 10 mL of sterile normal saline by IV route. Group II (n = 35) received ACB with 17 mL of a solution (15 mL of 0.5% ropivacaine plus 0.5 µg kg−1 of dexmedetomidine plus normal saline to make a final volume of 17 mL) and 10 mL of sterile normal saline by IV route. Group III (n = 35) received ACB with 17 mL of a solution (15 mL of 0.5% ropivacaine plus 2 mL of sterile normal saline to make a final volume of 17 mL) and 0.5 µg kg−1 of dexmedetomidine diluted in sterile normal saline to make a final volume of 10 mL by IV route.

Technique of ACB

An anaesthesiologist not participating in analysis and management of subjects prepared the study drugs and adjusted PCA pump settings. ACB was performed by a blinded anaesthesiologist with 10 cm, 18 gauge (G) Tuohy needle (Braun Medical, Melsungen, Germany) in PACU at mid-thigh level between the anterior superior iliac spine and the patella using a high-frequency (5–10 MHz) ultrasound probe of ultrasound machine (Sonosite, Inc., Bothell, WA, USA). In a cross-sectional view, the saphenous nerve was visualized lateral to the femoral artery under the sartorius muscle. After ensuring Tuohy needle tip proximity to the saphenous nerve, 5.0 mL of normal saline was injected in adductor canal to facilitate insertion of 20G catheter beyond the tip of the epidural needle for up to 5 cm. Thereafter, study drugs were administered in accordance with group allocation to blinded subjects.

The morphine PCA pump (Medima S-PCA) was set as follows: morphine concentration,1.0 mg mL−1; individual morphine boluses, 1.0 mg per bolus; lock-out interval, 5 minutes; dose limit, 0.2 mg kg−1 over 4 hours and no background infusion. All subjects received IV PCA morphine, paracetamol 1 g every 6 hours and ondansetron 8 mg every 12 hours in the postoperative period. Rescue analgesia was provided with IV diclofenac 75 mg in 100 mL normal saline over 10 minutes if the patient experienced a VAS score greater than 4, in spite of the above multimodal analgesic regime. Decoding was done at the completion of the study.

Outcome measures

All subjects were monitored for mean arterial pressure (MAP), pulse rate (PR), respiratory rate (RR), VAS for pain at rest and on movement (pain at 45°–60° knee flexion), rescue analgesic requirement, total morphine consumption, nausea or vomiting, Ramsay sedation scale (RSS) score and for any other complaints after block at 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30 and 60 minutes and later at 2, 4, 6, 8, 12 and 24 hours’ interval. Nausea/vomiting were assessed using a 4-point scale: where 0 stands for none, 1 stands for slight, 2 stands for moderate, 3 and 4 stands for severe. RSS sedation scores included 1, for awake, agitated and restless subjects; 2, for awake, cooperative, oriented and tranquil; 3, for awake, responsive to commands only; 4 for asleep but brisk response to light glabellar tap or to loud auditory stimulus; 5, for asleep with sluggish response to light glabellar tap or to loud auditory stimulus; and 6 for asleep with no response to light glabellar tap or to loud auditory stimulus.

ROM at knee joint was assessed at 12 and 24 hours by knee bending exercise which measures the degrees of flexion at knee joint with the help of a goniometer. TUG test was performed at 12 and 24 hours postoperatively by asking patient to walk for 3 m on a level ground and return back to his place, and the time taken for the same was noted. The postoperative pain satisfaction at 24 hours were assessed using a 5-point scale, where 5 stands for very satisfied, 4 stands for satisfied, 3 stands for undecided, 2 stands for dissatisfied and 1 stands for very dissatisfied.

Statistical analysis

Sample size was calculated from data based on few cases conducted in our institution. The pilot cases setup was similar to those in the study cases. A minimal acceptable difference of 30% in postoperative morphine consumption was considered significant for sample size estimation. The mean morphine consumption in subjects receiving dexmedetomidine with ropivacaine in ACB was 5 mg with a standard deviation of 4.08, whereas, in IV dexmedetomidine group, the mean morphine consumption was 5.25 mg with a standard deviation of 3.4. The control group receiving only ropivacaine for ACB had mean opioid consumption of 8.25 mg with a standard deviation of 4.72. A sample size of 29 subjects per group was calculated with a power of 80% and confidence interval of 95%. To compensate for drop-outs, sample size was increased to 35 subjects per group with a total of 105 in the study. The presumed normally distributed data were presented as mean and standard deviation or as median and interquartile range (IQR). The normality of quantitative data was checked by measures of Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests of normality. For normally distributed data, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by post hoc multiple comparisons test was used to compare the three groups. Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Mann–Whitney U test was used for statistical analysis of skewed continuous variables. For comparison of haemodynamic variables repeated-measure ANOVA was applied. For time-related skewed or ordinal data, Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied. Proportions were compared using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, depending on their applicability. Bonferroni correction was used for multiple comparisons. All the statistical tests were two-sided and were performed at a significance level of α = 0.05. Analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 22.0). Intention to treat analysis was not done since there were no drop-outs.

Results

The mean postoperative morphine consumption was significantly reduced till 4 hours in Group II, 0.57 mg (0.98 (0–3)) (p = 0.011) and up to 6 hours in Group III, 0.77 mg (1.00 (0–4)) (p = 0.004) as compared to control group. The mean postoperative morphine consumption was comparable at 24 hours in Group III, 3.57 mg (1.73 (0–8)) and Group II, 3.34 mg (1.92 (0–7)) (p = 1.000) (Figure 2). The time-to-first analgesic request was significantly prolonged in Group III, 8.57 hours (4.98) compared to Group I, 4.43 hours (5.54) and Group II, 7.14 hours (4.83) (p < 0.001). The VAS scores at rest and movement were comparable in all the three groups at all the time intervals studied (p > 0.05) (Figures 3 and 4). There were no significant differences in ROM (Figure 5) and TUG tests among the groups at 24 hours postoperatively. The mean PR and RR were comparable between the groups at all the time intervals of observation. The mean MAP was significantly lower in Group III till 2 hours in PACU. There were no adverse effects, that is, hypotension or bradycardia observed during the study. The mean RSS was significantly higher in Group III, 2.49 (0.74 (2–4)) as compared to Group I, 2.09 (0.28 (2–3)) and Group II, 2.09 (0.28 (2–3)) till 20 minutes postoperatively (p = 0.003).

Figure 2.

Postoperative comparison of total morphine consumption (from 0 minutes in PACU to 24 hours) in 105 subjects who received postoperative ACB. Values are presented as mean (SD (range)).

*p < 0.05.

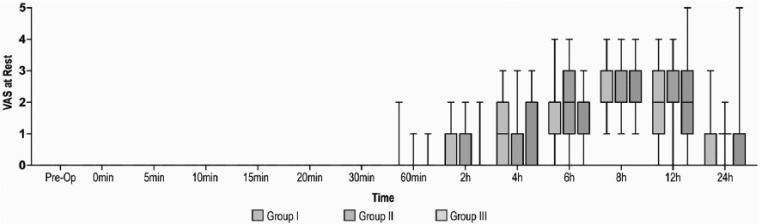

Figure 3.

Preoperative and postoperative comparison of VAS at rest (from 0 minutes in PACU to 24 hours) in 105 subjects who received postoperative ACB. Group I: Ropivacaine in ACB. Group II: ropivacaine and dexmedetomidine in ACB. Group III: ropivacaine in ACB with intravenous dexmedetomidine. Values are presented as median (IQR (range)).

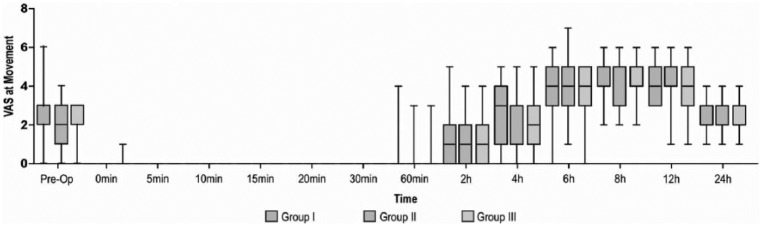

Figure 4.

Preoperative and postoperative comparison of VAS at movement (from 0 minutes in PACU to 24 hours) in 105 subjects who received postoperative ACB. Group I: ropivacaine in ACB. Group II: ropivacaine and dexmedetomidine in ACB. Group III: ropivacaine in ACB with intravenous dexmedetomidine. Values are presented as median (IQR (range)).

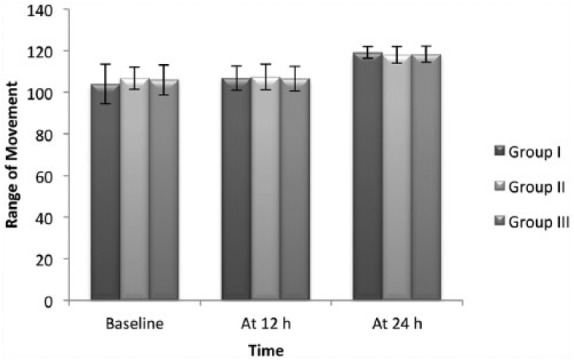

Figure 5.

Preoperative and postoperative comparison of range of movement (at 12 and 24 hours) in 105 patients who received postoperative ACB. Group I: ropivacaine in ACB. Group II: ropivacaine and dexmedetomidine in ACB. Group III: ropivacaine in ACB with intravenous dexmedetomidine. Values are presented as mean ± SD.

Discussion

ACB provides analgesia to anteromedial region of the knee.8 It has been evaluated earlier for postoperative pain management in subjects undergoing arthroscopic surgeries,9 medial meniscectomy10 and total knee arthroplasty (TKA).11 In this study, it was noticed that total morphine consumption was significantly reduced at 4 hours but not at 24 hours postoperatively. Although the extent of spinal block, tourniquet time and pressure, duration of surgery and speed of IV dexmedetomidine infusion were not part of recordings, their uniformity in both the group was ensured to avoid any confounding errors.

Perineural dexmedetomidine and postoperative opioid consumption

Combination of dexmedetomidine and LA for peripheral nerve blocks had produced inconsistent results, which may be due to lower dose of dexmedetomidine used.12 For example, Abdulatif et al.12 reported a dose-dependent opioid sparing effect of dexmedetomidine with 0.5% bupivacaine (25 mL) in femoral nerve block (FNB). In a study by Packiasabapathy et al.,13 perineural dexmedetomidine 1 µg kg−1 as adjuvant to LA (0.25% bupivacaine 20 mL) in FNB did not significantly reduce postoperative morphine consumption at 24 hours, but produced significant reduction with 2 µg kg−1. However, the total dose of LA (50 mg) used by Packiasabapathy et al. was lesser than that used by Abdulatif et al. (125 mg). In contrast to above studies, Oritz-Gomez et al.14 could not find any significant difference between pain scores in ACB group with and without dexmedetomidine. Studies utilizing higher doses of dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant to the LA, witnessed significant morphine consumption at 24 hours.12,15 However, an increase in the dose of dexmedetomidine would also reflect in increased incidence of its complications like hypotension.12,15 Another noteworthy finding in this study was a significant reduction in morphine consumption at 60 minutes, 2 hours and 4 hours postoperatively. Such an outcome could possibly be attributed to an additional analgesic effect of dexmedetomidine 0.5 µg kg−1. After first bolus, further boluses of 15 mL of 0.5% ropivacaine were injected in groups receiving ACB. Since the duration of perineural dexmedetomidine analgesia in ACB was not known, further ropivacaine boluses (0.5%, 15 ml) every 6 hourly were provided for ensuring postoperative analgesia.

Perineural dexmedetomidine on duration of analgesia

Perineural dexmedetomidine (0.5–1 µg kg−1) as an adjuvant to LA has a duration of analgesia of 4–5 hours.16,17 This duration may correlate with initial 4 hours in this study when morphine consumption was significant between groups.

Oritz-Gomez et al.14 failed to observe statistical significance in postoperative pain scores and need for rescue analgesia in ACB group with and without administration of 100-µg perineural dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant to 0.375% levobupivacaine in elective TKA. However, it may be noted that nociceptive inputs in TKA surgeries are different (sciatic and femoral nerves)18 from ACL reconstruction surgeries (saphenous nerve).

Time of first analgesic demand

The duration of first analgesic administration in this study was largest in IV group and smallest in control group. This duration in IV dexmedetomidine group is similar to a study by Agrawal et al.,19 where duration of first postoperative analgesic requirement was 353.13 ± 39.6 minutes in dexmedetomidine group. This could be explained due to 4–6 half-lives of IV dexmedetomidine (normal half-life 1.5–3 hours),20 that is, 6–8 hours.

Perineural and IV dexmedetomidine groups: comparable morphine consumption

The comparable morphine consumption at 24 hours in this study could be due to equivalence in local and IV effect of dexmedetomidine. Locally, perineural dexmedetomidine causes vasoconstriction, inhibition of C-fibres discharge and decrease in release of inflammatory mediators.15 IV dexmedetomidine could prolong postoperative analgesia due to its central action, anti-inflammatory properties21 and potentiation of other analgesics.22 This resulted in delayed first bolus of IV PCA morphine in subjects receiving IV dexmedetomidine in this study. In addition, sedative effects of dexmedetomidine23 might prevent the subjects to use PCA pump in the initial period. As noticed in this study, Abdallah et al.24 also observed similar postoperative total morphine consumption at 24 hours with either IV or local perineural dexmedetomidine (0.5 µg kg−1) in interscalene block.

All subjects in this study were instructed to take boluses at VAS > 4 and had adequate analgesia as depicted by their lower and comparable VAS scores. In addition, they were receiving intermittent boluses of LA and IV paracetamol.

Motor sparing effect of ACB

An interesting finding in this study is that the strength of the quadriceps muscle was well preserved in all subjects of this study. ROM and TUG tests were also comparable to baseline at 24 hours postoperatively. This enabled active exercises and ambulation at 24 hours postoperatively. The presence of analgesia and absence of motor block with 0.5% of ropivacaine could be attributed to predominantly sensory nature of saphenous nerve in adductor canal and not a sign of block failure.

Requirement of rescue analgesics

None of the subjects in any of the three groups required additional rescue analgesia, which explained effective pain control with a combination of nerve block, IV paracetamol and PCA pump. Paracetamol was selected for its better safety profile and a shorter duration of analgesia (4–6 hours). Diclofenac 75 mg IV was kept as a rescue analgesic.

Sedation scoring

In the PACU, sedation was higher in IV dexmedetomidine group as compared to perineural dexmedetomidine or control group for initial 20 minutes. The sedative effect25 of IV dexmedetomidine is well recognized to account for this. However, all subjects remained drowsy but arousable.26 This finding is similar to administration of 0.7 µg kg−1 h−1 dexmedetomidine by Chopra et al.26 for awake fibreoptic intubation, where optimum sedation with preservation of arousability was noted. Nausea and vomiting were not reported by any of the subjects in this study though all subjects were receiving prophylactic ondansetron 8 mg IV also.

Subjects in this study were satisfied with pain control as illustrated by their comparable mean satisfaction scores. The satisfaction could be credited to the use of multimodal analgesic regimen in this study.27

The study, however, has few limitations. First, analgesic boluses need to be timed before physiotherapy in the postoperative period. Second, information regarding ease of performing physiotherapy could have also been obtained from patient as well as physiotherapist, and third, higher ASA grades of subjects should also be evaluated to know the impact of dexmedetomidine on haemodynamics.

Conclusion

Use of dexmedetomidine as adjuvant in ACB significantly reduced postoperative morphine consumption till 4 hours with perineural dexmedetomidine and up to 6 hours with IV dexmedetomidine in subjects receiving ultrasound-guided ACB for managing postoperative pain following ACL reconstruction surgeries. Postoperative morphine consumption was similar at 24 hours postoperatively in all the three groups. The study presents a negative outcome to the addition of 0.5 µg kg−1 perineural dexmedetomidine as an adjunct to LA for ACB.

Future prospective

Increasing the dose of perineural dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant to LA for ACB could prolong the duration of analgesia as evidenced in FNB. Similarly allowing higher concentration of dexmedetomidine in ACB could also prolong the duration of analgesia as seen in ulnar nerve blocks. These require further investigations.

Acknowledgments

D.T. takes full responsibility for the article, including for the accuracy and appropriateness of the reference list. This study was registered with Clinical Trials Registry, India: CTRI/2016/03/006712 dated 07 March 2016.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: This study was supported by GMCH.

Ethical approval: Institutional Ethics Committee GMCH Chandigarh (Regd No. ECR/658/Inst/PB/2014) Ethics/2015/0050. Approval letter No. 2572 dated 20 January 2016.

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Trial Registration: Prospective registration, No: CTRI/2016,03/006712. 07 March 2016.

Guarantor: DT

Contributorship: First author, corresponding author.

References

- 1. Thapa D, Ahuja V, Verma P, et al. Post-operative analgesia using intermittent vs. continuous adductor canal block technique: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2016; 60: 1379–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Parker RD, Streem K, Schmitz L, et al. Efficacy of continuous intra-articular bupivacaine infusion for postoperative analgesia after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a double-blinded, placebo-controlled, prospective, and randomized study. Am J Sports Med 2007; 35: 531–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kirskey MA, Haskins SC, Cheng J, et al. Local anesthetic peripheral nerve block adjuvants for prolongation of analgesia: a systematic qualitative review. PLoS ONE 2015; 10: e0137312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Venn RM, Bradshaw CJ, Spencer R, et al. Preliminary UK experience of dexmedetomidine, a novel agent for postoperative sedation in the intensive care unit. Anaesthesia 1999; 54: 1136–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Abdallah FW, Brull R. Facilitatory effects of perineural dexmedetomidine on neuraxial and peripheral nerve block: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth 2013; 110: 915–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Klupinski K, Krekora K, Woldanska-Okonska M. Evaluation of early physiotherapy in patients after surgical treatment of cruciate ligament injury by bone-tendon-bone method. Pol Merkur Lekarski 2014; 36: 22–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yeung TS, Wessel J, Stratford PW, et al. The timed up and go test for use on an inpatient orthopaedic rehabilitation ward. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2008; 38: 410–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Burckett-St Laurant D, Peng P, Giron Arango L, et al. The nerves of the adductor canal and the innervation of the knee: an anatomic study. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2016; 41: 321–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bonet A, Koo M, Sabate A, et al. Ultrasound-guided saphenous nerve block is an effective technique for perioperative analgesia in ambulatory arthroscopic surgery of the internal knee compartment. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim 2015; 62: 428–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hanson NA, Derby RE, Auyong DB, et al. Ultrasound-guided adductor canal block for arthroscopic medial meniscectomy: a randomized, double-blind trial. Can J Anaesth 2013; 60: 874–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grevstad U, Mathiesen O, Lind T, et al. Effect of adductor canal block on pain in patients with severe pain after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized study with individual patient analysis. Br J Anaesth 2014; 112: 912–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abdulatif M, Fawzy M, Nassar H, et al. The effects of perineural dexmedetomidine on the pharmacodynamic profile of femoral nerve block: a dose-finding randomised, controlled, double-blind study. Anaesthesia 2016; 71: 1177–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Packiasabapathy SK, Kashyap L, Arora MK, et al. Effect of dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant to bupivacaine in femoral nerve block for perioperative analgesia in patients undergoing total knee replacement arthroplasty: a dose-response study. Saudi J Anaesth 2017; 11: 293–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ortiz-Gomez JR, Pereperez-Candel M, Vazquez-Torres JM, et al. Postoperative analgesia for elective total knee arthroplasty under subarachnoid anesthesia with opioids: comparison between epidural, femoral block and adductor canal block techniques (with and without perineural adjuvants). A prospective, randomized, clinical trial. Minerva Anestesiol 2017; 83: 50–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Memary E, Mirkheshti A, Dabbagh A, et al. The effect of perineural administration of dexmedetomidine on narcotic consumption and pain intensity in patients undergoing femoral shaft fracture surgery; a randomized single-blind clinical trial. Chonnam Med J 2017; 53: 127–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lin YN, Li Q, Yang RM, et al. Addition of dexmedetomidine to ropivacaine improves cervical plexus block. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan 2013; 51: 63–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thakur A, Singh J, Kumar S, et al. Efficacy of dexmedetomidine in two different doses as an adjuvant to lignocaine in patients scheduled for surgeries under axillary block. J Clin Diagn Res 2017; 11: UC16–UC21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bendtsen TF, Moriggl B, Chan V, et al. The optimal analgesic block for total knee arthroplasty. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2016; 41: 711–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Agrawal A, Agrawal S, Payal YS. Comparison of block characteristics of spinal anesthesia following intravenous dexmedetomidine and clonidine. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol 2016; 32: 339–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Manson KP, Zgleszewski SE, Dearden JL, et al. Dexmedetomidine for pediatric sedation for computed tomography imaging studies. Anesth Analg 2006; 103: 57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yun SH, Park JC, Kim SR, et al. Effects of dexmedetomidine on serum interleukin-6, hemodynamic stability, and postoperative pain relief in elderly patients under spinal anesthesia. Acta Med Okayama 2016; 70: 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ge D, Qi B, Tang G, et al. Intraoperative dexmedetomidine promotes postoperative analgesia and recovery in patients after abdominal hysterectomy: a double-blind, randomized clinical trial. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 21514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hall JE, Uhrich TD, Barney JA, et al. Sedative, amnestic, and analgesic properties of small-dose dexmedetomidine infusions. Anesth Analg 2000; 90: 699–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Abdallah FW, Dwyer T, Chan VW, et al. IV and perineural dexmedetomidine similarly prolong the duration of analgesia after interscalene brachial plexus block: a randomized, three-arm, triple-masked, placebo-controlled trial. Anesthesiology 2016; 124: 683–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Colin PJ, Hannivoort LN, Eleveld DJ, et al. Dexmedetomidine pharmacodynamics in healthy volunteers: 2. Haemodynamic profile. Br J Anaesth 2017; 119: 211–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chopra P, Dixit MB, Dang A, et al. Dexmedetomidine provides optimum conditions during awake fiberoptic intubation in simulated cervical spine injury patients. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol 2016; 32: 54–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Miaskowski C, Crews J, Ready LB, et al. Anesthesia-based pain services improve the quality of postoperative pain management. Pain 1999; 80: 23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]