Abstract

Introduction:

The use of intrathecal diamorphine is not commonplace in laparoscopic bariatric surgery. At our institution, a major UK bariatric centre, high-dose intrathecal diamorphine is routinely utilised.

Methods:

Data were analysed retrospectively. Fifty-three patients who had a spinal anaesthetic were matched against age, sex, body mass index and surgical procedure type to generate controls. Pain scores were recorded in the post-anaesthetic care unit on arrival, after 1 hour and on discharge to the ward. Post-operative nausea and vomiting; post-operative hypertension; pruritus; 24-hour morphine consumption and length of stay were measured.

Results:

Pain scores were better in the spinal anaesthetic group in all measured categories (p = 0.033, p < 0.01, p < 0.01); post-operative nausea and vomiting was less common in the spinal anaesthetic group (p < 0.01); post-operative hypertension was less common in the spinal anaesthetic group (p = 0.25); pruritus was more common in the spinal anaesthetic group (p < 0.01); morphine consumption was less common in the spinal anaesthetic group (p = 0.037). Length of hospital stay was reduced by 12.4 hours (p = 0.025).

Conclusion:

We propose that this is a practical and safe technique to adopt. A randomised-control trial will need to be conducted in order to find the most efficacious volume of local anaesthetic and dose of diamorphine

Keywords: Intrathecal, diamorphine, neuroaxial, bariatric, bariatric surgery

Introduction

Despite its minimal access approach, post-operative pain following laparoscopic bariatric surgery can be difficult to manage and often requires the use of systemic opioids in the post-operative period. Multi-modal strategies are encouraged but debate continues around what constitutes the best approach for this patient population.1 The ideal regime encompasses both good intra- and post-operative analgesia, encourages early mobilisation and avoids side effects such as post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV) and central nervous system (CNS) and respiratory depression.

Opioids play a traditional role in the delivery of analgesia but are often approached with caution in the obese population because of concerns around delayed post-operative complications.2 This is of particular concern in obese patients and those with underlying sleep disordered breathing (SDB) where post-operative care in a critical care setting is more likely to be sought. This can make the logistics of proceeding with surgery difficult due to the high demands that critical care units face from other medical and surgical specialties.

Spinal anaesthesia with intrathecal opioid is widely embraced and utilised in laparoscopic procedures for colorectal, urological and gynaecological surgery. Its use, however, is not commonplace in bariatric surgery. The use of low-dose intrathecal morphine has been studied in bariatric surgery giving promising results with improved post-operative pain scores, shorter time to ambulation and reduced length of stay. Importantly, there were no reported respiratory complications post-operatively.3

Others studies, in the non-bariatric population, have demonstrated that 1 mg diamorphine, which has a lower pKa and is more lipid soluble than morphine, is safe and gives superior analgesia with no worsening of side effects compared to 0.5 mg.4 However, in a group of patients undergoing knee replacements, pruritus was found to be more common in doses of >0.75 mg. They also did not report any incidences of respiratory depression.5

At our institution, a major UK bariatric centre, ‘high-dose’ (⩾1 mg) intrathecal diamorphine together with bupivacaine, is frequently used in patients undergoing laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) surgery. This retrospective cohort study was performed to compare pain scores, length of hospital stay (LoS), post-operative analgesic and antiemetic consumption, and complications in patients undergoing laparoscopic bariatric surgery with intrathecal diamorphine compared to matched controls.

Methods

Support from the Joint Research Office and approval from the Health Research Authority was obtained. All patients who underwent LSG and LRYGB from December 2015 to September 2017 (inclusive) were identified, a total of 291 cases. Of these, 62 patients received spinal analgesia with high-dose subarachnoid diamorphine and this was designated the spinal group.

The statistical computing software R (version R 3.3.0 GUI 1.68) running the MatchIt6 package was used to select an equivalent number of cases from the remaining 229 cases using ‘nearest neighbour’ propensity score matching.6 The covariates, age, sex, body mass index (BMI) and surgical procedure type (LSG vs LRYGB), were used to generate the control group. Balance of covariates between the two groups was improved for age, sex and surgical procedure, but not for BMI. Surgery was performed by the same four surgeons and anaesthesia delivered by four anaesthetists.

Data were collected from anaesthetic chart documentation and electronic patient records (Cerner UK) related to the admission. Nine patients from each group were excluded due to missing notes or anaesthetic charts.

Length of stay (LoS), in hours, was measured as the time from the commencement of anaesthesia to the time being deemed fit for discharge. Post-operative pain scores were documented by nursing staff on admission into the post-anaesthetic care unit (PACU), after 1 hour and on discharge in line with our institution’s guidelines. Pain scores were recorded using the verbal rating scale (VRS) of either none, mild, moderate or severe.

PONV and post-operative hypertension were defined as patients requiring pharmacological treatment in the PACU. Post-operative pruritus was defined as either a documented complaint, the administration of an anti-pruritic or both.

All patients were cannulated in the anaesthetic room and had standard anaesthetic monitoring applied.7 No patients required invasive monitoring or central venous catheterisation. Patients receiving a spinal anaesthetic had this performed prior to the induction of general anaesthesia.

Spinal group

Forty-five patients (Table 1) had a spinal anaesthetic with 0.25% isobaric bupivacaine (median volume 2.0 mL [IQR 1.2–2.2 mL]) and diamorphine (median dose 1 mg [IQR 1.0–1.5 mg]). Six patients had a spinal anaesthetic with 1 mL of 0.5% isobaric bupivacaine and 1 mg diamorphine. Two patients had a spinal anaesthetic with 1.4 mL of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine and 0.6 mg diamorphine.

Table 1.

The volumes (mL) of bupivacaine and doses (mg) of diamorphine used.

| Bupivacaine | Diamorphine |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.6 mg | 1 mg | 1.2 mg | 1.25 mg | 1.5 mg | |

| 1.4 mL 0.5% Hyperbaric | 2 | ||||

| 1 mL 0.5% Hyperbaric | 6 | ||||

| 1.2 mL 0.25% Isobaric | 1 | ||||

| 1.5 mL 0.25% Isobaric | 3 | 1 | |||

| 1.6 mL 0.25% Isobaric | 2 | ||||

| 2.0 mL 0.25% Isobaric | 34 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2.2 mL 0.25% Isobaric | 1 | ||||

Following this, general anaesthesia was induced with fentanyl (median dose 100 mcg [IQR 100–300 mcg]) and propofol in all patients. All patients received rocuronium. Intra-operative analgesia was intravenous paracetamol 1 g (53 patients), intravenous diclofenac 75 mg (19 patients), fentanyl (4 patients, median 100 mcg [IQR 50–250 mcg]). Antiemesis was ondansetron 4–8 mg (48 patients), dexamethasone 3.3–6.6 mg (26 patients), cyclizine 50 mg (9 patients) and metoclopramide 10 mg (3 patients). The maximum cumulative dose of fentanyl was 500 mcg. Forty-one patients had 40 mL 0.25% bupivacaine, infiltrated under the diaphragm under direct vision by the surgeon at the end of the procedure, prior to closure.

Control group

General anaesthesia was induced with fentanyl in 47 patients (median 150 mcg [IQR 100–500 mcg]) and propofol in all patients. All patients received rocuronium. Intra-operative analgesia was intravenous paracetamol 1 g (44 patients), intravenous diclofenac 75 mg (20 patients), fentanyl in 27 patients (median 150 mcg [IQR 100–500 mcg]), morphine in 23 patients (median 10 mg [IQR 6–18 mg]), ketamine in 9 patients (median 40 mg [IQR 30–50 mg]). Two patients received intravenous diamorphine 5 and 7 mg, respectively. Antiemesis was ondansetron 4–8 mg (51 patients), dexamethasone 3.3–6.6 mg (41 patients), cyclizine 50 mg (6 patients), metoclopramide 10 mg (14 patients). The maximum cumulative dose of fentanyl was 1000 mcg. Fifty patients had intraperitoneal local anaesthetic.

In all cases, anaesthesia was maintained with inhaled desflurane with end-tidal monitoring in an oxygen and air mix. The patients were ventilated with intermittent positive-pressure ventilation (IPPV) and a positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) of 5–8 cmH20. Extubation was performed with neuromuscular monitoring, in the sitting position and after the administration of 200–400 mg of sugammadex.

All patients were recovered in a PACU adjacent to the operating theatres. All bays were monitored and no patients required invasive monitoring.

Statistical analysis

Parametric data were analysed using Student’s t test and the chi-squared test, respectively. Significance was considered at P < 0.05. Data were anonymised and statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel 2016 (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA, USA).

Results

One hundred and six cases were analysed in detail; fifty-three in each group. Patient characteristics were similar in each group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics and operation type.

| Control group | Spinal group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean) | 42 | 43 | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 40 | 43 | |

| Male | 13 | 10 | |

| BMI (mean) | 44 | 46 | |

| ASA | 2 | 37 | 41 |

| 3 | 16 | 12 | |

| Procedure | LRYGB | 31 | 25 |

| LSG | 22 | 28 | |

ASA: American Society of Anaesthesiologists classification; BMI: body mass index; LRYGB: laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; LSG: laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy.

Recorded post-operative pain scores were better and in all measured categories (p = 0.033, p =< 0.01, p =< 0.01, respectively) for patients receiving a spinal anaesthetic (Table 3). The distribution of pain scores was the same across all age groups in the spinal group.

Table 3.

Pain scores (number of patients) in the control and spinal anaesthesia groups.

| Pain score | On admission into PACU |

PACU + 1 hour |

Discharge from PACU |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | Spinal group | Control group | Spinal group | Control group | Spinal group | |

| None | 19 | 35 | 6 | 42 | 15 | 49 |

| Mild | 19 | 7 | 16 | 8 | 31 | 4 |

| Moderate | 10 | 10 | 29 | 3 | 7 | 0 |

| Severe | 5 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

PACU: post-anaesthetic care unit.

Fewer patients in the spinal group required oral morphine solution post-operatively (20 patients vs 25 patients). The required average doses of oral morphine were lower in the spinal group in the first 24 hours (13.25 mg vs 21.4 mg, p = 0.037) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Average 24-hour oral morphine consumption.

The incidence of PONV in the PACU requiring treatment was lower in the spinal group. As expected, pruritus was more common in the spinal group. All of these patients required chlorphenamine 10 mg in the recovery area for symptom control but no further doses post-operatively. The avoidance of post-operative hypertension is important to maintain the integrity of the surgical anastomosis. At our institution, hypertension, if not pain related, is managed with oral or sublingual antihypertensives. Post-operative hypertension was less common in the spinal group (Table 4)

Table 4.

Incidence of PONV, pruritus and hypertension in the control and spinal anaesthesia groups.

| Control group | Spinal group | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PONV | 33 | 19 | <0.01 |

| Pruritus | 1 | 10 | <0.01 |

| Hypertension | 21 | 16 | 0.25 |

PONV: post-operative nausea and vomiting.

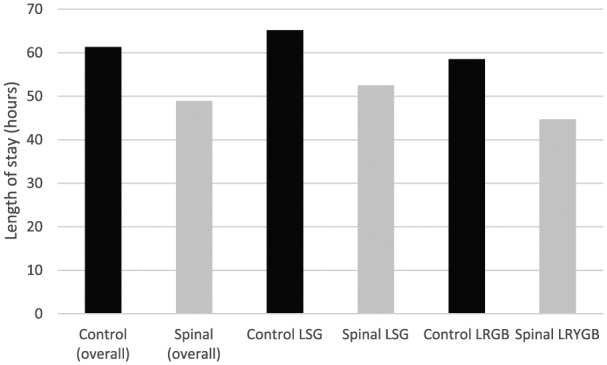

The mean LoS was reduced by 12.4 hours in the spinal group compared to the control (48.9 hours vs 61.3 hours, p = 0.025) (Figure 2). This was found to be independent of the day of the week the surgery was carried out. Sub-group analysis showed that this reduction was also independent of gender.

Figure 2.

Length of stay (hours).

Two patients required naloxone from the spinal group while in the PACU. This was for a reduced respiratory rate and drowsiness, respectively. Both received 400 mcg subcutaneously with good effect. No further doses were required and there were no other documented undesirable side effects of note.

Discussion

This retrospective analysis of data suggests that high-dose intrathecal diamorphine is an effective form of analgesia for patients undergoing laparoscopic bariatric surgery. The use of high-dose intrathecal diamorphine has not been formally studied in patients undergoing bariatric surgery. Its use is more commonly seen in lower doses in other laparoscopic procedures such as colorectal, gynaecological and urological surgery; caesarean sections and knee and hip arthroplasties. Its use is now well established in colorectal surgery with superior pain scores and LoS.8,9

Studies have shown that high intrathecal doses (up to 2.5 mg) are safe with no dangerous side effects.4,5 There might, however, be limited analgesic benefits above certain doses.5,10 There also might be a point where the side effects (PONV, pruritus) are deemed to be undesirable.10 Our findings partially contradict these findings as we have demonstrated reduced PONV in the spinal group but predictably, increased pruritus.

Clinicians might be concerned about the delayed side effects of intrathecal opioids, particularly respiratory depression. Previous studies have demonstrated that the incidence of respiratory depression is no different to lower doses, and that intrathecal opioid use in the bariatric population appears to be safe.3,5 Two patients in the spinal group received single doses of naloxone in the PACU, for respiratory depression (respiratory rate of six breaths per minute) and ‘drowsiness’, respectively. They had received 1 and 1.2 mg diamorphine and a total of 100 and 250 mcg fentanyl, respectively. It is difficult to comment as to whether this was due to the intrathecal diamorphine. There were no further complications, or the need for further doses. Both patients were cared for on the normal ward. The general current consensus is a move away from opioid use in the obese population and there is a degree of apprehension about its intrathecal use for shorter surgical procedures as well as their use outside of the provisions of post-operative critical care.

Opioid-free anaesthesia (OFA) is a developing technique using multimodal drugs to provide anaesthesia and analgesia both intra and post-operatively.11 Promoters of the technique argue that intraoperative goals are to provide physiological stability and control the stress response by controlling sympathetic stimulation. In addition, they believe that pain relief is only important when the patient is awake in the post-operative period.11 It has been shown to reduce PONV with reports of improved outcomes in the non-opioid group with a well-documented method consisting of total intravenous anaesthesia (TIVA) with propofol, dexmedetomidine and a single dose of ketamine.12 Alpha-2 agonists like clonidine and dexmedetomidine produce sedative and analgesic effects while causing autonomic blockade.13,14 It has also been shown to provide improved intraoperative haemodynamics and post-operative pain scores.13

We have shown a lower incidence of PONV in our spinal anaesthetic group compared to the non-spinal group. In the United Kingdom, dexmedetomidine is licenced for use as a sedative in the intensive care unit.15 It is not a common feature in most operating rooms.

We demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in pain scores on admission to, after 1 hour and on discharge from the PACU. This difference also appeared to affect older patients rather than younger patients; however, the number of cases is insufficient to determine whether this is statically significant by age group. This suggests older patients gain the greatest benefit from spinal anaesthesia for these procedures which is of particular importance given the increasing age of surgical patients in the United Kingdom and worldwide.

Regional anaesthesia, particularly myofascial plane blocks, is playing an increasingly more prominent role in the avoidance or limitation of opioid administration. However, a study into the use of bilateral transverse abdominal plane (TAP) blocks in LRYGB surgery showed no difference in cumulative opioid consumption and pain scores in the first 24 hours and the rates of nausea, vomiting and pruritus were the same compared to the control group.16 The use of erector spinae plane (ESP) blocks, where local anaesthetic is thought to spread to the paravertebral space giving somatic and visceral analgesia, has recently been described in patients undergoing laparoscopic bariatric surgery.17 Although thought to be simple and safe block by the authors, it is perceived as an advanced regional anaesthetic technique by most general anaesthetists, therefore adopting it as a first-line technique would be difficult.

Implementation of such blocks is limited by operator experience, equipment and good knowledge and visualisation of anatomy. They also can be time consuming. In addition, most would argue that intrathecal delivery of local anaesthetic and diamorphine is more reliable than delivery into a fascial plane.

Although performing a spinal anaesthetic in the obese can be technically challenging, no patients required the use of ultrasound to aid insertion and in those that required more than two attempts with a standard spinal needle, the use of a standard 16G Tuohy needle and long 27G pencil point needle helped to locate the epidural space and subsequently, the subarachnoid space, with a needle-through-needle technique. As a result, all general anaesthetists should be able to perform this technique.

Finally, we have demonstrated a modest reduction in the LoS in patients receiving a spinal anaesthetic. We found this to be statistically significant overall but following sub-group analysis we found the LoS reduction to be significant in the LRYGB group but not the LSG group. The sample sizes are small but this should not detract from potential benefits for patients and the health service in general should these results be borne out by larger studies.

Conclusion

We recognise that there are limitations to our study; namely the retrospective approach adopted, the small patient sample size and the non-standardised anaesthetic technique. As such, prospective research will be required to confirm or refute the findings we have presented. Nevertheless, our results suggest that spinal anaesthesia with high-dose intrathecal diamorphine is a practical and safe technique to adopt in patients undergoing bariatric surgery and does not mandate patients to be admitted routinely to the critical care environment. In order to assess this technique further and examine the hypotheses generated in this research, a randomised-control trial will need to be conducted in order to find the most efficacious volume of local anaesthetic and dose of diamorphine.

Acknowledgments

T.G.W. wrote the manuscript and was the guarantor.J.J. and A.K. contributed to data analysis. J.N. assisted with data collection. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Health Research Authority on 17 December 2017 (IRAS project ID: 227817; REC reference: 18/HRA/0402; sponsor: Imperial College Hospital NHS Trust).

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Informed consent: Informed consent was not sought for the present study because of its retrospective nature. No patient identifiable data were included.

ORCID iD: Thomas G Wojcikiewicz  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9815-9196

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9815-9196

References

- 1. Schug SA, Raymann A. Postoperative pain management of the obese patient. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2011; 25: 73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Benumof JL. Obesity, sleep apnea, the airway and anaesthesia. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2004; 17: 21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. El Sherif FA, Othman AH, El-Rahman AMA, et al. Effect of adding intrathecal morphine to a multimodal analgesic regimen for postoperative pain management after laparoscopic bariatric surgery: a prospective, double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Br J Pain 2016; 10: 209–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stacey R, Jones R, Kar G, et al. High-dose intrathecal diamorphine for analgesia after Caesarean section. Anaesthesia 2001; 56: 54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jacobson L, Kokri MS, Pridie AK. Intrathecal diamorphine: a dose-response study. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1989; 71: 289–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ho DE, Imai K, King G, et al. MatchIt: nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference. J Stat Softw 2011; 42: 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Checketts MR, Alladi R, Ferguson K, et al. Recommendations for standards of monitoring during anaesthesia and recovery 2015: association of anesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Anaesthesia 2016; 71: 85–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Levy BF, Scott MJ, Fawcett W, et al. Randomized clinical trial of epidural, spinal or patient-controlled analgesia for patients undergoing laparoscopic colorectal surgery. B J Surg 2011; 98: 1068–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Levy BF, Scott MJ, Fawcett W, et al. 23-hour-stay laparoscopic colectomy. Dis Colon Rectum 2009; 52: 1239–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Saravanan S, Robinson AP, Qayoum Dar A, et al. Minimum dose of intrathecal diamorphine required to prevent intraoperative supplementation of spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section. Br J Anaesth 2003; 91: 368–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mulier J. Opioid free general anesthesia: a paradigm shift? Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim 2017; 64: 427–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ziemann-Gimmel P, Goldfarb AA, Koppman J, et al. Opioid-free total intravenous anaesthesia reduces postoperative nausea and vomiting in bariatric surgery beyond triple prophylaxis. Br J Anaesth 2014; 112: 906–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Feld JM, Laurito CE, Beckerman M, et al. Non-opioid analgesia improves pain relief and decreases sedation after gastric bypass surgery. Can J Anaesth 2003; 50: 336–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hofer RE, Sprung J, Sarr MG, et al. Anesthesia for a patient with morbid obesity using dexmedetomidine without narcotics. Can J Anaesth 2005; 52: 176–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. National Institute for Health Clinical Excellence (NICE). Dexmedetomidine, https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/dexmedetomidine.html (accessed 12 September 2018).

- 16. Albrecht E, Kirkham KR, Endersby RVW, et al. Ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block for laparoscopic gastric-bypass surgery: a prospective randomized controlled double-blinded trial. Obes Surg 2013; 23: 1309–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chin KJ, Malhas L, Perlas A. The erector spinae plane block provides visceral abdominal analgesia in bariatric surgery: a report of 3 Cases. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2017; 42: 372–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]