Abstract

Objective:

To estimate the alignment between the Ontario Ministry of Children and Youth Services (MCYS) expenditures for children’s mental health services and population need, and to quantify the value of adjusting for need in addition to population size in formula-based expenditure allocations. Two need definitions are used: “assessed need,” as the presence of a mental disorder, and “perceived need,” as the subjective perception of a mental health problem.

Methods:

Children’s mental health need and service contact estimates (from the 2014 Ontario Child Health Study), expenditure data (from government administrative data), and population counts (from the 2011 Canadian Census) were combined to generate formula-based expenditure allocations based on 1) population size and 2) need (population size adjusted for levels of need). Allocations were compared at the service area and region level and for the 2 need definitions (assessed and perceived).

Results:

Comparisons were made for 13 of 33 MCYS service areas and all 5 regions. The percentage of MCYS expenditure reallocation needed to achieve an allocation based on assessed need was 25.5% at the service area level and 25.6% at the region level. Based on perceived need, these amounts were 19.4% and 27.2%, respectively. The value of needs-adjustment ranged from 8.0% to 22.7% of total expenditures, depending on the definition of need.

Conclusion:

Making needs adjustments to population counts using population estimates of children’s mental health need (assessed or perceived) provides additional value for informing and evaluating allocation decisions. This study provides much-needed and current information about the match between expenditures and children’s mental health need.

Keywords: mental health need, children, services, expenditures, Ontario, funding formula

Abstract

Objectif :

Estimer la correspondance entre les dépenses du ministère des Services à l’enfance et à la jeunesse (MSEJ) de l’Ontario allouées aux services de santé mentale des enfants et les besoins de la population, et quantifier la valeur de l’ajustement aux besoins ainsi qu’à la taille de la population pour des dépenses attribuées selon une formule. Deux définitions des besoins sont utilisées: un « besoin évalué » en fonction de la présence d’un trouble mental, et un « besoin perçu » étant la perception d’un besoin d’aide professionnelle.

Méthodes :

Les estimations des besoins de santé mentale des enfants et des contacts avec les services (tirées de l’Étude sur la santé des jeunes Ontariens 2014), les données sur les dépenses (tirées des données administratives du gouvernement) et les dénombrements de la population (tirés du Recensement canadien de 2011) ont été combinés pour produire des attributions de dépenses selon une formule en fonction a) de la taille de la population et b) du besoin (taille de la population ajustée aux niveaux du besoin). Les attributions ont été comparées dans le secteur des services et au niveau de la région et dans les 2 définitions du besoin (évalué et perçu).

Résultats :

Des comparaisons ont été effectuées dans 13 des 33 secteurs de services du MSEJ et dans toutes les 5 régions. Le pourcentage de réattribution des dépenses du MSEJ nécessaire pour obtenir une allocation basée sur le besoin évalué était de 25,5% au niveau du secteur des services et de 25,6% au niveau de la région. Selon le besoin perçu, ces chiffres étaient de 19,4% et de 27,2%, respectivement. La valeur de l’ajustement aux besoins oscillait entre 8,0% et 22,7% des dépenses totales, selon la définition du besoin.

Conclusion :

Effectuer des ajustements aux besoins selon la taille de la population en utilisant les estimations dans la population des besoins de santé mentale des enfants (évalués ou perçus) offre une valeur ajoutée pour éclairer et évaluer les décisions en matière d’allocation. Cette étude procure de l’information actuelle et très nécessaire sur la correspondance entre dépenses et besoins de santé mentale des enfants.

The Ontario Ministry of Children and Youth Services (MCYS) was responsible for funding services addressing the mental health needs of children and youth aged 0 to 17 (herein “children”) until August 2018.1 Although additional services are provided by the Ministries of Health and Education (in primary care, hospital settings, and schools) and by private providers, advocacy, charity and self-help groups,2 total expenditure allocations to children’s mental health services and the proportion of public and private sector allocations are unknown. Also unknown is Ontario’s overall capacity to care for children with mental health needs, as service planning and provision is not coordinated across sectors.3 Accordingly, this work focuses exclusively on MCYS expenditures in children’s mental health services and excludes expenditures in child welfare, primary care, hospitals, schools and private settings.

There are 5 MCYS administrative regions in Ontario (West, Central, East, North, and Toronto) comprising 33 service areas that are geographically bounded in one or more Statistics Canada Census Divisions. Within service areas, MCYS contracts with individual service agencies to provide programs targeting the early identification of mental health problems, as well as individual-, family-, and group-based interventions for these problems.4 MCYS service areas and regions formed our target allocation units (TAUs), with individual agency expenditures aggregated to both the area and region levels.

To date, limited information is publicly available on how MCYS has approached expenditure allocation decisions; although, the introduction of a funding formula has been considered.5,6 Governments commonly use these types of formulas, as they are believed to maximize the usefulness of tax dollars for the public good by distributing resources according to need, thereby creating equitable capacities for care.7 Although formula-based allocations consider the principle of equity (distributing resources according to need), they do not consider the relationship between the allocation and outcomes (i.e., how expenditure allocations get used once distributed, service effectiveness, among others).

At a minimum, we expect children’s mental health need to be a function of the number of children living in a particular area. Beyond this, Bradshaw8 developed a typology of need that we can apply: normative (presence of mental disorder); felt (parent/youth subjective perception of a mental health problem); expressed (demand for mental health service); comparative (population inequities in mental health); medical (treatable disease); and social (restoring quality of life).9 With no single definition of need in children’s mental health, and evidence that the presence of disorder is only a partial determinant of service use,10 we defined the concept of need in 2 ways: “assessed” (the presence of mental disorder) and “perceived” (subjective perceptions of mental health need), based on data from a large population survey.

In the absence of periodic, general population surveys, the systematic collection of data on children’s mental health need would require significant time, resources, and commitment to implement. It is therefore important to quantify how well a simple population-based allocation approximates a needs-based allocation. Small allocation differences would signify that using easily available population counts to generate expenditure allocations is more cost-effective and preferable. However, evidence from the Canadian health sector suggests these approaches can differ considerably.11 In addition to understanding how MCYS expenditures align with population- and needs-based allocations, we also aim to quantify the value in adjusting for need over and above population size.

To our knowledge, this is the first study anywhere to use an allocation formula to evaluate expenditure allocations in children’s mental health. Only 2 studies in Canada have examined allocations for children’s mental health at all. In Québec, Blais and colleagues12 reported no significant regional differences in need indicators but large differences in mental health resources and services in 1992 to 1993. In Ontario, Boyle and Offord13 reported large discrepancies in expenditures and service use that could not be explained by children’s mental health need.

The objectives of the current study are to: 1) evaluate the extent to which expenditures for MCYS children’s mental health services in Ontario are aligned with population- and needs-based expenditure allocations; 2) quantify the value of using a needs-based formula as opposed to a simple, population-based formula; and 3) estimate the impact of the TAU and definition of children’s mental health need on our findings. We addressed 3 questions. First, what percentage of 2015-2016 MCYS expenditures would need to be reallocated to achieve a needs-based expenditure allocation? Second, what percentage of expenditures would need to be reallocated to move from a population-based allocation to a needs-based allocation? Finally, to what extent does the TAU and definition of need influence the results?

Methods

Data

This study combines aggregate data from: 1) the 2014 Ontario Child Health Study (OCHS);14 2) MCYS expenditures for the 2015-2016 fiscal year, obtained from the Client Services Branch of MCYS; and 3) the 2011 Census population counts of children.15 The 2014 OCHS is a province-wide, cross-sectional, epidemiological study of children’s mental health. A probability sample of 6,537 households (50.8% response) participated, with 10,802 children aged 4 to 17. Using the 2014 Canadian Child Tax Benefit file as the sampling frame, households were selected based on a complex 3-stage survey design that involved cluster sampling of residential areas and stratification by residency (urban, rural) and income (areas and households cross-classified by three levels of income). Data were collected during home visits by trained Statistics Canada interviewers from the person most knowledgeable about the child and by computer-assisted interviews from children aged 12 to 17. Detailed accounts of the survey design, content, training, and data collection are available elsewhere.14,16

Concepts and Measures

Children’s mental health need

Assessed need

One randomly selected child from each family (n = 6,537) and their parent was interviewed using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Youth (MINI-KID).17,18 Youth aged 12 to 17 were also interviewed. Children meeting the criteria for one or more disorders in the past 6 months,19 according to parent or youth report, were classified with assessed need. The remaining children (n = 4,265) were classified based on a total scale score from the OCHS Emotional Behavioural Scales (OCHS-EBS)20 converted to a binary disorder classification. The OCHS-EBS contains a 52-item checklist that is self-reported by parents about children of all ages and by youth aged 12 to 17 to assess mental health disorder symptoms over the past 6 months. The OCHS-EBS demonstrates satisfactory reliability and validity when used as either a dimensional20 or categorical21 measure. A total scale score cut-off was selected and applied to produce a prevalence of one or more disorders that matched the same disorder prevalence assessed by the MINI-KID interview. Assessed need was coded as present (1) when the child was identified with one or more disorders, based on parent or youth report; and otherwise, as absent (0).

Perceived need

Perceived need was defined as a positive response to a question asking whether the parent (for ages 4 to 17) or youth (for ages 12 to 17) thought that, in the past 6 months, the child had any emotional or behavioural problems. Perceived need was coded as present (1) if the parent or youth answered yes to this question; and otherwise, absent (0).

Analysis

Selection and evaluation of target allocation units

Due to extensive clustering in the 2014 OCHS, we assessed the coverage and representativeness of the data in each TAU to identify those areas and regions eligible for inclusion. Survey respondents were grouped according to administrative boundaries and were assessed for adequate coverage. Adequacy was defined as an unweighted sample size over 100, a weighted sample size over 20,000, and household weighted sample estimates of the percentage of single-parent families within 5% of the 2011 Census and an average income within 20%. Without existing guidelines for assessing coverage adequacy, cut-offs were selected based on statistical power requirements and observed differences between Census and survey estimates on socio-demographic variables.16

Expenditure allocation formulas

Population-based

This formula divided total MCYS expenditures by the 2011 Census count of children aged 0 to 17 in Ontario to estimate an average 2015-2016 dollars per capita amount, which came to $341,367,552 ÷ 2,683,795 = $127. To generate total expenditure allocations for each TAU, this amount was multiplied by the number of children in each area.

Needs-based

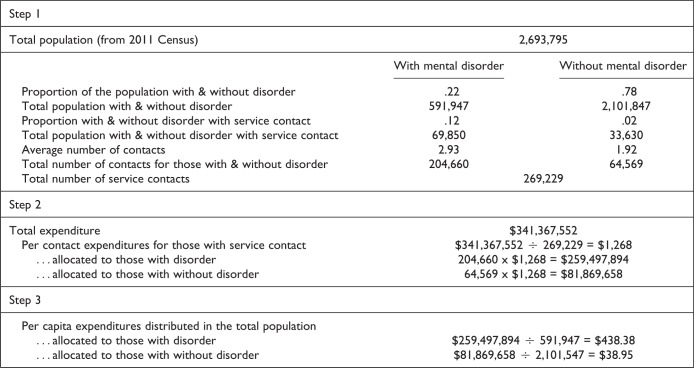

This formula included 3 steps, as summarized for assessed need in Figure 1. The process outlined here for assessed need was repeated using perceived need for professional help as the definition of need. In step 1, we adjusted our formula for imperfect targeting of services by splitting overall expenditures between children with and without mental health need (assessed need based on the presence of mental disorder in the first expenditure allocation and perceived need in the second). This was done by estimating the proportion of children with and without mental disorder, who had mental health agency service contact, based on parent responses to the question, “In the past 6 months, did you, another family member or <child> see or talk to anyone from any mental health or addictions agency because of concerns about his/her mental health?” Proportions were multiplied by the 2011 Census population counts to estimate the numbers of children in the general population with and without mental disorder who had service contact (69,850 and 33,630 children, respectively). We also adjusted the formula for the differential number of service contacts among those with and without mental disorder in recognition that more resources may be required to serve those with a mental disorder v. those without. This was done by estimating the average number of service contacts based on parent responses to the question “In the past 6 months, how many times in total did you, another family member, or <child> see or talk to anyone from this/these agency/ies about your concerns?” These averages were multiplied by the number of children with and without mental disorder with service contact to estimate the total number of service contacts by children in the general population with and without disorder (204,661 and 64,570 contacts, respectively).

Figure 1.

Outline of the process used to generate dollar per capita allocations based on population size adjusted for children's mental health need, defined as the presence of mental disorder and weighted by the likelihood that children with and without mental disorder will be in contact with services. This example uses the assessed need definition and rounded estimates. The process was repeated using the perceived need definition.

In step 2, we divided total expenditures ($341,367,552) among service contacts (204,661 + 64,570 = 269,231) and multiplied that amount ($1,268) by the number with and without disorder that had service contact. In step 3, we divided these totals among the total number of children in the population with and without disorder. This resulted in dollar per capita allocations of $438 for children with mental disorder and $39 for those without.

We then multiplied Census population counts from each TAU by the aggregate proportions of children with and without mental disorder in each TAU based on 2014 OCHS data (see Table 2 for assessed and perceived need estimates and population counts). We multiplied these numbers by the dollar per capita amounts to generate total expenditure allocations for each TAU.

Table 2.

Table of Total Expenditures and Allocations for Selected Service Areas and Regions.

| MCYS Region and Service Area | MCYS Expenditures | Population-based Allocation | Assessed Needs-based Allocation | Perceived Needs-based Allocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| West | $72,246,178 | $71,996,145 | $74,989,469 | $81,388,441 |

| Haldimand-Norfolk | $2,172,879 | $2,180,762 | $2,983,205 | $3,087,113 |

| Niagara | $9,424,423 | $8,190,963 | $9,864,967 | $11,600,549 |

| Middlesex | $14,521,891 | $8,856,804 | $9,060,159 | $10,032,389 |

| Central | $82,878,481 | $119,184,232 | $118,144,457 | $110,887,754 |

| Dufferin/Wellington | $4,674,442 | $5,896,533 | $6,796,540 | $6,959,004 |

| Waterloo | $9,823,075 | $11,115,468 | $12,675,822 | $13,583,433 |

| Halton | $14,182,012 | $11,698,997 | $9,336,397 | $11,387,454 |

| York | $17,897,615 | $23,336,260 | $19,449,850 | $16,242,701 |

| Peel | $22,097,003 | $30,767,802 | $28,857,068 | $21,746,378 |

| East | $65,614,461 | $67,813,630 | $71,225,966 | $74,821,183 |

| Lanark/Leeds and Grenville | $5,725,664 | $3,081,778 | $4,093,527 | $4,277,347 |

| Hastings/Prince Edward/Northumberland | $7,370,543 | $4,428,157 | $4,659,232 | $6,210,662 |

| Durham | $9,477,283 | $13,848,402 | $13,387,925 | $14,227,762 |

| Ottawa | $21,281,697 | $17,850,793 | $18,507,710 | $19,204,827 |

| North | $44,240,846 | $20,435,457 | $27,734,040 | $33,048,576 |

| Nipissing/Parry Sound/Muskoka | $5,827,074 | $3,222,883 | $4,803,200 | $5,915,981 |

| Toronto | $76,387,586 | $54,537,865 | $49,273,620 | $41,221,598 |

Statistical analysis

All survey estimates were weighted using standardized weights to reflect the probability of selection. Total overall weighted estimates of both assessed and perceived children’s mental health need and service contact in addition to TAU-specific weighted estimates were generated. We did not adjust for age and sex, as the age and sex distributions of MCYS services and expenditures are unknown, and we expect age and sex differences in mental health need to be evenly distributed across the province. Population counts and MCYS expenditures are based on a 0 to 17 age group to align with the age group that MCYS agencies serve. Estimates of need are based on a 4 to 17 age group, the target population of the 2014 OCHS. However, excluding 0- to 4-year-olds in our assessments of need would not affect prevalence estimates differently across TAUs. Our service area analysis included only expenditures and population counts from eligible service areas. Our regional analysis used expenditures and counts from all regions.

Our analysis compared needs-based expenditure allocations with 2015-2016 MCYS expenditures and with population-based allocations. To quantify the amount of MCYS expenditures that would need to be reallocated to achieve a needs-based expenditure allocation, we calculated the differences between allocations, summed the absolute differences, and calculated this as a percentage of total expenditures. To quantify the value in adjusting for need in addition to population size, we followed the same procedure comparing needs-based allocations to population-based allocations. We then compared allocation differences at the service area and region levels, and repeated the analysis using perceived need instead of assessed need.

Results

Thirteen service areas and all 5 regions met the adequacy criteria, shown in Table 1 along with estimates of need and child population counts. As Toronto is both a service area and region, we included it as a region only due to its size. Unweighted sample sizes are suppressed for confidentiality reasons.

Table 1.

Number of Children, Prevalence of Assessed and Perceived Need by Selected Service Areas and Regions, and Summary Statistics of Coverage Evaluation Comparing Weighted Survey Estimates with 2011 Census Estimates of Proportion of Single Parent Families and Household Income.

| Coverage Evaluation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCYS Region and Service Area | No. Children 0 to 17 |

% Children with Mental Health Need | Weighted Sample Size (Rounded to Base 50) | Absolute % Difference in Estimates of Single Parent Families | Absolute % Difference in Estimates of Household Incomea | |

| Assessed | Perceived | |||||

| West | 568,135 | 23.4 | 32.0 | 108,050 | 1 | 9 |

| Haldimand-Norfolk | 22,255 | 31.2 | 22.1 | 23,300 | 3 | 9 |

| Niagara | 83,590 | 26.3 | 30.2 | 127,950 | 2 | 9 |

| Middlesex | 90,385 | 20.9 | 37.6 | 29,300 | 2 | 7 |

| Central | 940,505 | 21.8 | 25.9 | 750,950 | 1 | 7 |

| Dufferin/Wellington | 60,175 | 24.8 | 31.6 | 33,650 | 2 | 0 |

| Waterloo | 113,435 | 24.4 | 17.9 | 147,750 | 1 | 6 |

| Halton | 119,390 | 14.1 | 38.3 | 57,650 | 3 | 16 |

| York | 238,150 | 15.2 | 32.8 | 138,700 | 4 | 3 |

| Peel | 313,990 | 18.3 | 28.6 | 233,800 | 2 | 8 |

| East | 535,130 | 23.7 | 31.1 | 485,200 | 3 | 10 |

| Lanark/Leeds and Grenville | 31,450 | 30.0 | 38.0 | 43,900 | 5 | 11 |

| Hastings/Prince | 45,190 | 21.8 | 25.7 | 26,850 | 3 | 7 |

| Edward/Northumberland | ||||||

| Durham | 141,325 | 19.2 | 27.2 | 136,550 | 1 | 11 |

| Ottawa | 182,170 | 21.3 | 50.4 | 132,400 | 3 | 11 |

| North | 161,260 | 33.6 | 46.7 | 108,050 | 2 | 6 |

| Nipissing/Parry Sound/Muskoka | 32,890 | 34.9 | 38.4 | 29,000 | 1 | 15 |

| Toronto | 488,765 | 15.5 | 17.9 | 388,250 | 3 | 12 |

aAbsolute differences in income were calculated by subtracting the 2014 OCHS income estimate from the 2011 Census income estimate and then dividing this amount by the 2011 Census income estimate to generate a proportion. Multiplying by 100 gives a %. (e.g., $18,000-$20,000=$2000, $2,000/$20,000= 0.1, 0.1 × 100 = 10%)

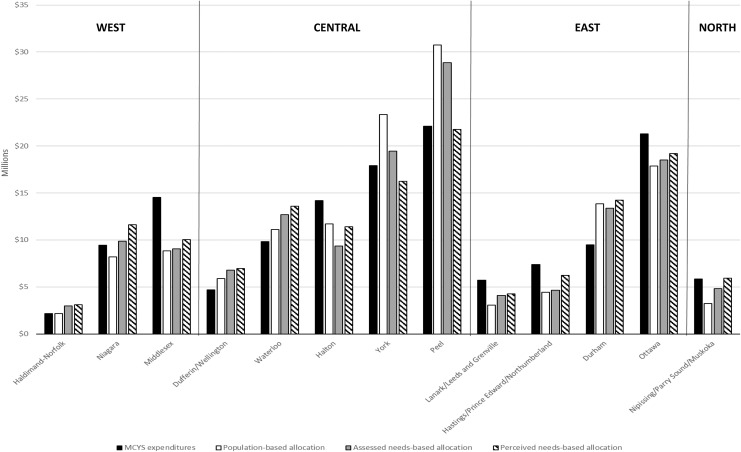

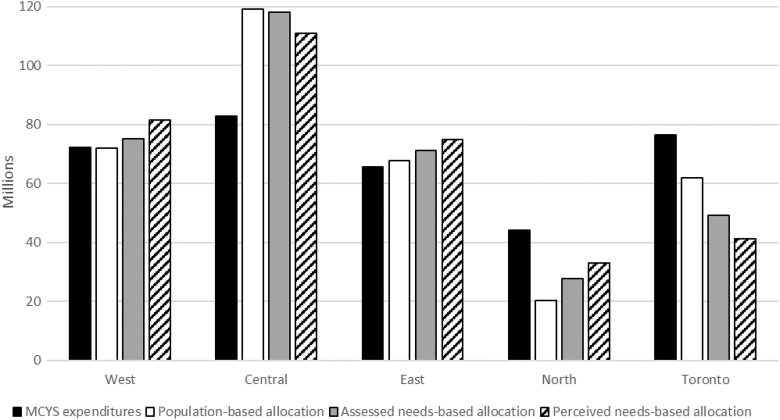

Table 2 presents MCYS expenditures and the 3 formula-based expenditure allocations: 1) population-based in the second column, 2) assessed needs-based in the third column, and 3) perceived needs-based in the fourth column. For example, in the West region, actual MCYS expenditures were $72,246,178 compared with a population-based allocation of $71,996,145; an assessed needs-based allocation of $74,989,469; and a perceived needs-based allocation of $81,388,441. Figures 2 and 3 graph the same information. For service areas, total MCYS expenditures ranged from $2.2 M (Haldimand-Norfolk) to $22.1 M (Peel). For regions, expenditures ranged from $44.2 M in the North to $82.8 M in the Central region.

Figure 2.

Graph of allocations to MCYS service areas based on expenditures, population-based allocations, and needs-based allocations.

Figure 3.

Graph of allocations to MCYS regions based on expenditures, population-based allocations, and needs-based allocations.

Table 3 shows allocation differences, the sum of the absolute total differences, and the percentage of total expenditures represented by this amount. The percentages in columns 1 and 2 represent the proportion of MCYS expenditure reallocation required for a distribution commensurate to population size adjusted for need. These amounts were 25.5% and 25.6% for service areas and regions, respectively, based on an assessed need definition, and 19.4% and 27.2%, respectively, based on a perceived need definition. The percentages in columns 3 and 4 represent the allocation difference between population-based and needs-based allocations expressed as a percentage of total expenditures. Based on an assessed needs-based allocation, this difference was 11.9% and 8.0% of total expenditures for service areas and regions, respectively. Based on a perceived needs-based allocation, this difference was 22.7% and 17.0%, respectively.

Table 3.

Table of Allocation Differences and Reallocations at the Service Area and Region Level.

| Difference between MCYS Expenditures V.: | Difference between Population-based Allocation V.: | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCYS Region and Service Area | Assessed Needs-based Allocation | Perceived Needs-based Allocation | Assessed Needs-based Allocation | Perceived Needs-based Allocation |

| West | ||||

| Haldimand-Norfolk | −$810,326 | −$914,234 | $802,443 | $906,351 |

| Niagara | −$440,544 | −$2,176,126 | $1,674,003 | $3,409,586 |

| Middlesex | $5,461,732 | $4,489,502 | $203,355 | $1,175,586 |

| Central | ||||

| Dufferin/Wellington | −$2,122,098 | −$2,284,562 | $900,007 | $1,062,471 |

| Waterloo | −$2,852,747 | −$3,760,358 | $1,560,355 | $2,467,965 |

| Halton | $4,845,615 | $2,794,558 | −$2,362,599 | −$311,543 |

| York | −$1,552,235 | $1,654,914 | −$3,886,409 | −$7,093,558 |

| Peel | −$6,760,065 | −$350,625 | −$1,910,735 | −$9,021,425 |

| East | ||||

| Lanark/Leeds and Grenville | $1,632,137 | $1,448,317 | $1,011,749 | $1,195,569 |

| Hastings/Prince Edward/Northumberland | $2,711,311 | $1,159,881 | $231,075 | $1,782,505 |

| Durham | −$3,910,642 | −$4,750,479 | −$460,477 | $379,360 |

| Ottawa | $2,773,987 | $2,076,870 | $656,916 | $1,354,034 |

| North | ||||

| Nipissing/Parry Sound/Muskoka | $1,023,874 | -$88,907 | $1,580,317 | $2,693,098 |

| Total absolute differences | $36,897,314 | $27,949,334 | $17,240,440 | $32,853,051 |

| Reallocation (percentage of total expenditures) | 25.5% | 19.4% | 11.9% | 22.7% |

| Regions | ||||

| West | −$2,743,291 | −$9,142,263 | $2,993,325 | $9,392,297 |

| Central | −$35,265,976 | −$28,009,273 | −$1,039,775 | −$8,296,479 |

| East | −$5,611,505 | −$9,206,722 | $3,412,336 | $7,007,553 |

| North | $16,506,806 | $11,192,280 | $7,298,583 | $12,613,119 |

| Toronto | $27,113,966 | $35,165,988 | −$12,664,468 | −$20,716,490 |

| Total absolute differences | $87,241,545 | $92,716,516 | $27,408,487 | $58,025,938 |

| Reallocation (percentage of total expenditures) | 25.6% | 27.2% | 8.0% | 17.0% |

Discussion

This study is the first to use a formula-based approach to: 1) evaluate the extent to which government expenditures to children’s mental health services align with the number of children and their levels of need, and 2) quantify the value of adjusting for need, over and above the number of children. Our findings suggest that 26% of MCYS expenditures would need to be reallocated to achieve a distribution commensurate to the levels of assessed need in the population. To avoid penalizing areas with lower need, a policy option would be to employ incremental funding adjustments over time to higher need areas (negative differences in Table 3). In our data, this represents 12.8% of expenditures, translating to new expenditures of $18.4 M across the 13 service areas or $43.6 M across the 5 regions in 2015-2016 funds.

There is substantial variation in the alignment of needs-based allocations with MCYS expenditures. For example, these differences were small in the West and East regions and large in the Central, North, and Toronto regions. The higher MCYS expenditures in the North might reflect greater service delivery costs. This could also be the case in Toronto, along with comparatively lower levels of need due to the high proportion of immigrants in the Toronto region (83% in our sample); children of immigrants have been found to have lower levels of mental health need.19,22 Lower levels of MCYS expenditures in the Central region may be due to expenditure allocations falling behind population growth. Census population counts for this region show a 19% population increase from 2006 to 2016 compared with growth ranging from 0% to 9% in the other regions for the same period.23,24

Is there value in making needs-adjustments to population counts when evaluating allocation decisions? Our findings suggest that there is. Depending on the definition of need used, the difference between needs-based and population-based allocations ranged from 8% to 23% (15% on average) or from $17,240,440 to $58,025,938 ($33,881,979 on average) in 2015-2016 dollars, which is consistent with previous findings from the health care sector.11 This suggests that going from population- to needs-based allocations would have considerable value based on the reallocation estimates.

If Ontario proceeds with a formula-based funding approach, efforts should be made to include needs-adjustments. Implementing adjustments for children’s mental health need means confronting 2 challenges. The first is achieving consensus on the definition and measurement of children’s mental health need. The second is identifying a cost-efficient method for obtaining reliable population estimates of need for MCYS service areas.

In reference to the first challenge, children’s mental health need was defined as the presence of mental disorder identified by parents or their children. Acknowledging that many service providers do not use DSM disorder classifications to define children’s mental health need, we replicated our analysis using parent and child subjective perceptions of need. Compared with assessed need, perceived need more directly captures mental health concerns and is associated more closely with actual service demand.25 Differences between assessed and perceived need in their patterns of recommended expenditures indicate that a consensus on the definition and measurement of children’s mental health need is a prerequisite for developing a needs-based formula.

In reference to the second challenge, decision makers must devise strategies to minimize the costs of obtaining reliable estimates of children’s mental health need associated with data collection, sampling, and survey timing. Periodic, in-person, household surveys like the 2014 OCHS would provide affordable and reliable estimates at the provincial level but not at the individual service area level; producing reliable estimates at the service area level could be more costly. One difficulty for policymakers is that sampling small areas is more informative for service planning and evaluation because it can identify differences in need not discernible by sampling large areas. In addition, the interval between surveys—5, 10, or 20 years—will influence overall cost. However, the ideal interval for discerning population changes in children’s mental health need has not been identified.

Limitations

This study is not without limitations. One, limited sample size and coverage restricted the analysis to 13 of the 33 MCYS service areas in Ontario. The regional replication of our findings provides confidence that the interpretation of our findings applies to the other 20 areas, and that a general formula-based approach can be applied to other provinces and jurisdictions. Two, a 4-year gap exists between the 2014 OCHS and the 2011 Census. However, correlations between variables assessing the same phenomena in the 2014 OCHS and the 2011 Census are high, obviating concerns about census timing.16 More relevant and not addressable here are concerns about the quality of the Census data due to extensive non-response.26 Three, reliance on MCYS expenditures excluded resources contributed by other sectors (namely health and education) for the reasons outlined in the Introduction. Understanding the distribution of service expenditures across sectors and the capacity to care that these resources create, is an important area for further research when such information can be made available. Finally, this work focused only on service expenditures and puts aside important issues about service costs, effectiveness, efficiency, and outcomes that warrant exploration. Despite these limitations, we believe that this work provides a useful approach to using 2014 OCHS data to inform and evaluate government expenditure allocation decisions that could be modified to incorporate other estimates of need or additional relevant information. The availability of the 2014 OCHS data presents numerous opportunities for similar and further work in this much-neglected area.

Conclusion

This study combines estimates from general population survey data, Census data and government expenditures data to compare needs-based allocations with actual MCYS expenditures and a population-based allocation. Our findings suggest that an expenditure reallocation was needed in 2015-2016 to ensure resources were distributed according to need. Our findings also suggest there is value in including estimates of need, in addition to population size, in formula-based expenditure decisions.

The lack of a needs-based approach to expenditure decisions in children’s mental health reflects a lack of available data. Policymakers would benefit from identifying data collection opportunities or exploring the potential usefulness of alternative indicators of need that are systematically collected. The availability of this data would provide an opportunity to inform and evaluate funding allocation decisions and establish much-needed understanding about the funding required to serve children with mental health needs and their families. Ensuring the usefulness of this data would also require addressing certain challenges including: 1) achieving consensus on the definition of mental health need; 2) finding commitment, resources, and capacity within governments to collect and use this kind of data; and 3) coordinating initiatives and funding across the various sectors involved with children’s mental health.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Ministry of Children and Youth Services for providing expenditure information used in the analysis, and acknowledge Nancy Pyette for technical assistance with editing and proofreading the manuscript.

Data Access: Data access available through Statistics Canada Research Data Centres.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by research operating grant 125941 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Health Services Research Grant 8-42298 from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC) and from funding from MOHLTC, the Ontario Ministry of Children and Youth Services and the Ontario Ministry of Education. Dr. Boyle was supported by CIHR Canada Research Chair in the Social Determinants of Child Health and Dr. Georgiades by the David R. (Dan) Offord Chair in Child Studies.

ORCID iD: Laura Duncan, MA, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7120-6629

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7120-6629

References

- 1. Government of Ontario. Draft child and youth mental health service framework. Toronto (ON): Queen’s Printer for Ontario; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Government of Ontario. Child and family services act. Revised statutes of Ontario (1990. c. C.11). 2015. Available from http://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/90c11 (accessed 2018 Jul 26).

- 3. Duncan L, Boyle MH, Abelson J, et al. Measuring children’s mental health in Ontario: policy issues and prospects for change. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;27(2):88–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Government of Ontario. Community-based child and youth mental health - Program guidelines and requirements #01: Core services and key processes. 2015. Available from http://www.children.gov.on.ca/htdocs/English/documents/specialneeds/mentalhealth/pgr1.pdf (accessed 2018 Jul 26).

- 5. MNP. Ministry of Children and Youth Services – Development of a Child and Youth Mental Health Services Allocation Funding Model: Community Need Definition Summary Report. Toronto (ON): MNP; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6. MNP. Ministry of Children and Youth Services – Development of a Child and Youth Mental Health Services Allocation Funding Model: September Consultation Feedback Summary Report. Toronto (ON: ): MNP; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7. National Research Council, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, Committee on National Statistics, Panel on Formula Allocations. Statistical Issues in Allocating Funds by Formula. Washington (DC: ): National Academies Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bradshaw J. Taxonomy of social need In: McLachlan G, ed. Problems and Progress in Medical Care: Essays on Current Research, 7th Series. London (UK: ): Oxford University Press; 1972. p. 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bradshaw J. The conceptualization and measurement of need: a social policy perspective In: Popay J, Williams G., ed. Researching the People’s Health. London (UK: ): Routledge; 2005. p. 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Offord DR, Boyle MH, Szatmari P, et al. Ontario Child Health Study: II. Six-month prevalence of disorder and rates of service utilization. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44(9):832–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Birch S, Chambers S. To each according to need: a community-based approach to allocating health care resources. CMAJ. 1993;149(5):607–612. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Blais R, Breton JJ, Fournier M, et al. Are mental health services for children distributed according to needs? Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48(3):176–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boyle MH, Offord D. Prevalence of childhood disorder, perceived need for help, family dysfunction and resource allocation for child welfare and children’s mental health services in Ontario. Can J Behav Sci, 1988;20(4):374–388. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Statistics Canada. 2014. Ontario Child Health Study (Master File). Statistics Canada. Survey No. 3824 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Statistics Canada. National Household Survey (NHS), 2011. Individuals File. Statistics Canada. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Boyle MH, Georgiades K, Duncan L, et al. The 2014 Ontario Child Health Study—Methodology. Can J Psychiatry. Forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sheehan DV, Sheehan KH, Shytle RG, et al. Reliability and validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID). J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(3):313–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Duncan L, Georgiades K, Wang L, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID). Psychol Assess. 2017;30(7):916–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Georgiades K, Duncan L, Wang L, et al. Six-month prevalence of mental disorders and service contacts among children and youth in Ontario: evidence from the 2014 Ontario Child Health Study. Can J Psychiatry. Forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Duncan L, Georgiades K, Wang L, et al. The 2014 Ontario Child Health Study Emotional Behavioural Scales (OCHS-EBS) Part I: a checklist for dimensional measurement of selected DSM-5 disorders. Can J Psychiatry. doi.org/10.1177/0706743718808250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21. Boyle MH, Duncan L, Georgiades K, et al. The 2014 Ontario Child Health Study Emotional Behavioural Scales (OCHS-EBS) Part II: Psychometric Adequacy for Categorical Measurement of Selected DSM-5 Disorders. Can J Psychiatry. doi.org/10.1177/0706743718808251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22. Comeau J, Georgiades K, Wang L, et al. Changes in the prevalence of child mental disorders and perceived need for professional help between 1983 and 2014: Evidence from the Ontario Child Health Study. Can J Psychiatry. Forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Statistics Canada. Population and Dwelling Count Highlight Tables, 2011 Census. Available from http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/dp-pd/hlt-fst/pd-pl/Table-Tableau.cfm?LANG=Eng&T=701 (accessed 2018 Jul 26).

- 24. Statistics Canada. Population and Dwelling Count Highlight Tables, 2011 Census. Available from http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/hlt-fst/pd-pl/Table.cfm?LANG=Eng&T=701&S=3 (accessed 2018 Jul 26).

- 25. Wichstrøm L, Belsky J, Jozefiak T, et al. Predicting service use for mental health problems among young children. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):2013–3184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hulchanski D, Murdie R, Walks A, et al. Canada’s voluntary census is worthless. Here’s why. The Globe and Mail, 2013. Available from http://neighbourhoodchange.ca/documents/2014/04/nhs-oped-data-tables.pdf (accessed 2018 Jul 26).