Abstract

Background

Pain on propofol injection is an untoward effect and this condition can reduce patient satisfaction. Intravenous lidocaine injection has been commonly used to attenuate pain on propofol injection. Although many studies have reported that lidocaine was effective in reducing the incidence and severity of pain, nevertheless, no systematic review focusing on lidocaine for preventing high‐intensity pain has been published.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to determine the efficacy and adverse effects of lidocaine in preventing high‐intensity pain on propofol injection.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2014, Issue 10), Ovid MEDLINE (1950 To October 2014), Ovid Embase (1988 to October 2014), LILACS (1992 to October 2014) and searched reference lists of articles.

We reran the search in November 2015. We found 11 potential studies of interest, those studies were added to the list of ‘Studies awaiting classification' and will be fully incorporated into the formal review findings when we update the review.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) using intravenous lidocaine injection as an intervention to decrease pain on propofol injection in adults. We excluded studies without a placebo or control group.

Data collection and analysis

We collected selected studies with relevant criteria. We identified risk of bias in five domains according to the following criteria: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, adequacy of blinding, completeness of outcome data and selective reporting. We performed meta‐analysis by direct comparisons of intervention versus control. We estimated the summary odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals using the random‐effects Mantel‐Haenszel method in RevMan 5.3. We used the I2 statistic to assess statistical heterogeneity. We assessed overall quality of evidence using the GRADE approach.

Main results

We included 85 studies, 82 of which (10,350 participants) were eligible for quantitative analysis in the review. All participants, aged 13 years to 89 years, were American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) I‐III patients undergoing elective surgery. Each study was conducted in a single centre in high‐ , middle‐ and low‐income countries worldwide. According to the risk of bias assessment, all except five studies were identified as being of satisfactory methodological quality, allowing 82 studies to be combined in the meta‐analysis. Five of the 82 studies were assessed as high risk of bias: one for participant and personnel blinding, one for incomplete outcome data, and three for other potential sources of bias.

The overall incidence of pain and high‐intensity pain following propofol injection in the control group were 63.7% (95% CI 60% to 67.9%) and 37.9% (95% CI 33.4% to 43.1%), respectively while those in the lidocaine group were 30.2% (95% CI 26.7% to 33.7%) and 11.8% (95% CI 9.7% to 13.8%). Both lidocaine admixture and pretreatment were effective in reducing pain on propofol injection (lidocaine admixture OR 0.19, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.25, 31 studies, 4927 participants, high‐quality evidence; lidocaine pretreatment OR 0.13, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.18, 41 RCTs, 3918 participants, high‐quality evidence). Similarly, lidocaine administration could considerably decrease the incidence of pain when premixed with the propofol (OR 0.19, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.24, 36 studies, 5628 participants, high‐quality evidence) or pretreated prior to propofol injection (OR 0.14, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.18, 50 studies, 4722 participants, high‐quality evidence). Adverse effects of lidocaine administration were rare. Thrombophlebitis was reported in only two studies (OR not estimated, low‐quality evidence). No studies reported patient satisfaction.

Authors' conclusions

Overall, the quality of the evidence was high. Currently available data from RCTs are sufficient to confirm that both lidocaine admixture and pretreatment were effective in reducing pain on propofol injection. Furthermore, there were no significant differences of effect between the two techniques.

Keywords: Adolescent; Adult; Aged; Aged, 80 and over; Humans; Middle Aged; Anesthesia; Anesthesiology; Anesthetics, Intravenous; Anesthetics, Intravenous/administration & dosage; Anesthetics, Intravenous/adverse effects; Anesthetics, Local; Anesthetics, Local/administration & dosage; Lidocaine; Lidocaine/administration & dosage; Pain; Pain/chemically induced; Pain/prevention & control; Propofol; Propofol/administration & dosage; Propofol/adverse effects

Plain language summary

Lidocaine for reducing propofol‐induced pain on anaesthesia in adults

Review question

Is intravenous, (directly into a vein), lidocaine injection effective in reducing the pain caused by the injection of propofol, given to induce anaesthesia in adults undergoing general anaesthesia?

Background

Propofol is an anaesthetic drug (an induction agent) which is given to induce and maintain anaesthesia in adults undergoing surgery. Propofol is a popular induction agent because it provides a smooth induction and faster recovery than other drugs such as thiopental. The main disadvantage of propofol is that it often causes people severe pain. This is because propofol is usually injected into a hand vein and can cause skin irritation. This can make the anaesthesia experience unpleasant. One method for preventing propofol‐induced pain is to give lidocaine either before the propofol injection or mixed in with the propofol. Lidocaine is a commonly used low‐cost local anaesthetic drug. The objective of this review was to determine how effective lidocaine was in reducing the high pain levels caused by the injection of propofol.

Study characteristics

We searched the databases until October 2014. We included 85 studies, 82 of which (10,350 participants) were eligible for quantitative analysis. The study participants were randomly selected to receive either intravenous lidocaine injection or normal saline (placebo) at the same time as the propofol injection.

We reran the search in November 2015. We found 11 potential studies of interest, those studies were added to the list of ‘Studies awaiting classification' and will be fully incorporated into the formal review findings when we update the review.

Study funding sources

Three out of the 85 studies were funded by either a pharmaceutical manufacturer with a commercial interest in the results of the studies or the company which supplied the propofol. Eight studies were supported by government hospital or university funds and one study was funded by a charitable grant.

Key results

We found that the injection of lidocaine into a vein, either mixing lidocaine with propofol or injecting lidocaine before propofol, could effectively reduce the incidence and the high levels of pain associated with the injection of propofol. Adverse effects such as inflammation (redness, swelling) of the vein at the injection site were rare and in two studies were not more frequent with the use of lidocaine. No study reported on patient satisfaction.

Statistics

Based on these results we would expect that out of 1000 patients receiving intravenous propofol, about 384 who did not also receive intravenous lidocaine, would experience moderate to severe pain, compared to only 89 patients who also received intravenous lidocaine.

Quality of the evidence

The overall quality of evidence was high with a very large beneficial effect obtained by the administration of lidocaine to reduce painful propofol injections.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Lidocaine for propofol‐induced pain on induction of anaesthesia in adults.

| Lidocaine for propofol‐induced pain on induction of anaesthesia in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: Adult participants receiving propofol for induction of anaesthesia Settings: Patients undergoing elective surgery Intervention: Lidocaine | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Lidocaine | |||||

| High‐intensity pain with lidocaine admixture Pain scales Follow‐up: 1‐5 minutes | Study population | OR 0.19 (0.15 to 0.25) | 4927 (31 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ||

| 305 per 1000 | 77 per 1000 (62 to 99) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 329 per 1000 | 85 per 1000 (69 to 109) | |||||

| High‐intensity pain with lidocaine pretreatment Pain scales Follow‐up: 1‐5 minutes | Study population | OR 0.13 (0.1 to 0.18) | 3918 (41 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ||

| 463 per 1000 | 101 per 1000 (79 to 134) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 457 per 1000 | 99 per 1000 (78 to 132) | |||||

| Incidence of pain with lidocaine admixture Pain scales Follow‐up: 1‐5 minutes | Study population | OR 0.19 (0.15 to 0.24) | 5628 (36 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ||

| 582 per 1000 | 209 per 1000 (173 to 250) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 679 per 1000 | 287 per 1000 (241 to 337) | |||||

| Incidence of pain with lidocaine pretreatment Pain scales Follow‐up: 1‐5 minutes | Study population | OR 0.14 (0.11 to 0.18) | 4722 (50 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ||

| 698 per 1000 | 244 per 1000 (203 to 294) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 743 per 1000 | 288 per 1000 (241 to 342) | |||||

| Adverse effects Events Follow‐up: 0‐7 days | An adverse effect, thrombophlebitis, was observed in two out of 32 studies (Ganta 1992; Smith 1996). One study (Ganta 1992) reported thrombophlebitis 4/85 participants in lidocaine pretreatment group compared with 8/85 cases in saline group. Another study (Smith 1996) reported thrombophlebitis within seven days postoperatively 9/22 participants in lidocaine pretreatment group, compared to 4/29 in saline group. However, there were no statistically significant differences in lidocaine and saline groups. | Not estimated | 4007 (32 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the median control group risk across studies, or the average risk for pooled data; and the control group risk for single studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; HR: Hazard ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 The quality of evidence was downgraded by two levels due to serious imprecision and inconsistency.

Background

Propofol is used intravenously for the induction and maintenance of anaesthesia. The main disadvantage of propofol is pain on injection, however it is a popular induction agent for ambulatory surgery as it provides smoother induction and faster recovery than other agents such as thiopental, which is considered to be the standard induction agent (Kevin 2003; McCluskey 2003).

Description of the condition

Propofol is a phenol compound that causes skin and mucous membrane irritation, leading to pain at the injection site in 80% to 90% of people (Kwak 2007a). Although the underlying mechanisms are still not fully understood, pain immediately after injection of propofol may be caused either by direct stimulation of nociceptors and free nerve endings in the venous wall or indirectly by the release of mediators, such as bradykinin and prostaglandin E2, which stimulate afferent nerve endings, leading to a delayed onset of pain (Brooker 1985; Eriksson 1997; Wong 2001).

Description of the intervention

Many different physicopharmacological interventions have been proposed to reduce the incidence and severity of this adverse effect of propofol (Appendix 2; Jalota 2011; Picard 2000). Lidocaine in various dosages and concentrations, or combined with other interventions for reducing pain on propofol injection, has been extensively evaluated and seems to be the most promising drug for this condition. To reduce pain on propofol injection, lidocaine is administered either by mixing with the propofol and injecting both together, or by injecting separately, as an intravenous pretreatment prior to the propofol injection.

Concerning the physicochemical reaction of propofol‐lidocaine mixtures, there have not been any reports of adverse reactions in vivo. However in vitro there was a report of coalescence of oil droplets (diameters ≥ 5 micron) 30 minutes after the addition of 40 mg lidocaine to propofol. This reaction is time‐ and dose‐dependent and may cause pulmonary embolism, depending on the dose of lidocaine. In addition, propofol concentrations in the mixture with 40 mg of lidocaine decreased linearly and significantly from 4 hours to 24 hours after preparation, while those combined with 20 mg or less of lidocaine were unchanged (Masaki 2003).

How the intervention might work

Lidocaine appears to provide good results in preventing pain on injection by propofol. The mechanisms of action are still unclear. A preceding injection of lidocaine caused a reduction of pain, probably due to the direct effect of local anaesthetics on vascular smooth muscle (Nicol 1991). In addition, the discomfort of pain on injection could be reduced by mixing a small amount of lidocaine to the propofol. This might be because lidocaine hydrochloride is a weak free base cation solution, which would lower the pH after mixing it with propofol (Brooker 1985; Eriksson 1997). However, the right dose and concentration are required to demonstrate good efficacy (Adachi 2002).

Why it is important to do this review

Although people suffer from pain only temporarily after injection of propofol, the level of pain may be severe (Michael 1996). This results in them having a terrible anaesthesia experience. Therefore, many anaesthesiologists are concerned about this issue and a great amount of research has been conducted in order to prevent the pain from propofol injection. Among all the drugs and interventions that can decrease pain on propofol injection, lidocaine is a very common drug, being both effective and easily available worldwide. The cost of lidocaine is also relatively low. Therefore, lidocaine is of particular interest to us. Even though Picard 2000 produced a quantitative systematic review on this subject, and Jalota 2011 produced a systematic review, , there have been a significant number of trials using lidocaine to prevent pain from propofol injection since these reviews were published. Also, no systematic review focusing on lidocaine for preventing high‐intensity pain has been published. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review was to evaluate, with the best available evidence, the efficacy of lidocaine treatment for preventing high‐intensity pain following propofol injection.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to determine the efficacy and adverse effects of lidocaine in preventing high‐intensity pain on propofol injection.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared the use of lidocaine intervention with placebo or other interventions in order to reduce the severity of pain in patients receiving intravenous propofol injection.

Types of participants

We included participants aged 13 years and older who were administered propofol intravenously.

We excluded studies in children (below 13 years of age) due to differences in children's pain‐scale rating methods, and difficulty in classifying high and low doses in children and adults; for example, 20 mg lidocaine may be a high dose in small children but not in adults.

Types of interventions

Lidocaine in various regimens and dosages versus placebo or control group, which were those without lidocaine. Both lidocaine and control groups might similarly receive some active adjunct, for example remifentanil, ketamine, etc.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The incidence of high‐intensity pain on propofol injection.

'High‐intensity pain’ was defined as the combination of moderate and severe pain levels. For different scales in each included study, we defined ‘low‐ and high‐intensity pain’ according to the definition of the scoring system of each included study. ‘Low‐intensity pain’ included mild pain, pain mentioned only when questioned, without any behavioural signs. ‘High‐intensity pain’ included moderate pain, severe pain, pain mentioned when questioned and accompanied by behavioural signs, or pain reported spontaneously not as a result of questioning, pain associated with grimacing, withdrawal movement of forearm, tears. In case the definition of the pain score was not clear, we categorized one‐third of the lower range of pain scores as ‘low‐intensity pain’ and two‐thirds of the upper range of pain scores as ‘high‐intensity pain’.

Secondary outcomes

Incidence of pain

Adverse effects (such as thrombophlebitis, cardiac arrhythmia, allergic reaction or local anaesthetic toxicity)

Patient satisfaction

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL2014, Issue 10); Ovid MEDLINE; (1950 to October 2014); Ovid Embase (1988 to October 2014); and LILACS (1992 to October 2014).

We developed a specific strategy for each database. We based each search strategy on that developed for MEDLINE (see Appendix 3 (CENTRAL); Appendix 4 (MEDLINE); Appendix 5 (EMBASE); Appendix 6 (LILACS)).

We combined the MEDLINE search strategy with the Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy phases one and two as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Lefebvre 2011).

We also looked for trials by manually searching abstracts of relevant conference proceedings. We checked the reference lists of relevant articles. We contacted relevant trial authors to identify any additional studies.

We did not apply language or publication restrictions.

We reran the search in November 2015. We found 11 potential studies of interest, those studies were added to the list of ‘Studies awaiting classification' and will be fully incorporated into the formal review findings when we update the review.

Searching other resources

We searched for relevant ongoing trials in www.controlled‐trials.com. The last search of this database was conducted in November 2015.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors (PE and SM) independently scanned the titles and abstracts of reports identified by searching the electronic databases and handsearching journals. We obtained the full texts of trials that appeared to be eligible RCTs, and inspected them to assess their relevance, based on a pre‐planned checklist. A third author (WS) settled any disagreements.

Data extraction and management

Three authors (PE, SD and SM) independently extracted the data using a specific data extraction forms (see Appendix 7)and assessed trial quality using a standardized checklist. We resolved any disagreement through consultation with a fourth author (WS).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We judged study quality on the basis of the following methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Random sequence generation (selection bias)

We described the allocation method used in each study, whether study authors provided adequate information to allow assessment in comparable groups or not.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator, shuffling envelopes);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number, judgement by clinicians);

unclear risk of bias.

Allocation concealment (selection bias)

We described the method used to conceal allocation to interventions that prevented participants and investigators seeing assignment in advance, during recruitment or changing allocation after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone randomization, consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (e.g. a list of random numbers, unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias)

We described the methods used to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received in each study. If studies were blinded, we regarded them as a low risk of bias. We assessed blinding separately in each outcome. We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias)

We described the methods used to blind the investigator from knowledge of which intervention a participant received in each study. If studies were blinded, we regarded them as a low risk of bias. We assessed blinding separately in each outcome. We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias)

We described the completeness of outcome data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis in each study. We state whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomized participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information is reported, or was supplied by the trial authors, we re‐included missing data in the analyses which we undertook. We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as‐treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomization);

unclear risk of bias.

Selective reporting (reporting bias)

We described the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias in each study. We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s prespecified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s prespecified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias

Other bias

We described any important concerns about other possible sources of bias in each study. We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low risk of other bias (the study appears to be free of other sources of bias);

high risk of other bias (e.g. had a potential bias from a study design, baseline imbalance, early stopping);

unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

We discussed the impact of the methodological quality on the results.

Measures of treatment effect

We expressed results as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for all categorical outcomes of the individual studies.

Unit of analysis issues

We included RCTs with two or more intervention groups (multi‐arm studies). For multi‐arm studies, we either included the directly relevant arms only, or divided the shared group into two or more groups, so that the total number of events and the total number of participants added up to the original size of the shared group.

Dealing with missing data

We extracted the information that was available from the published reports. Denominators for each group in each study were extracted based on all participants that allocated to that group. Some studies presented numerical data as graphs so we were not able to extract numerical data directly, but estimated them from the graphs.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed the heterogeneity among trials by the Chi2 test for heterogeneity with a 10% level of statistical significance and by determining the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). When interpreting the I2 statistic, we used the following recommendations as stated in (Deeks 2011).

0% to 40% might not be important.

30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity.

50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity.

75% to 100%: represents considerable heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed the possibility of publication bias in a meta‐analysis including at least 10 trials by visual inspection of funnel plots (Sterne 2011).

Data synthesis

We performed meta‐analyses using a random‐effects model for assessment of treatment effects because this approach is widely used and tends to give a more conservative estimate of treatment effects with wider confidence intervals than the fixed‐effect model (Deeks 2011). All analyses were done by using Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan 2014).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In order to perform a subgroup analysis and also to estimate the treatment effects for each subgroup as well as overall studies, we presented the results according to doses of lidocaine pretreatment or admixture, and the application of venous occlusion above injection site (Deeks 2011). Moreover, we also planned to perform subgroup analysis regarding age groups, speed of propofol injection and site of propofol injection, but data were not available.

Sensitivity analysis

We carried out sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome, in order to explore the robustness of the results, by keeping studies at low risk of selection bias (random sequence generation and allocation concealment) and removing studies at unclear or high risk of selection bias from the analysis.

Summarizing and interpreting results

We used the GRADE approach to interpret findings (Schünemann 2011) and we used GRADE profiler software (GRADEpro GDT 2015) to import data from Review Manager (RevMan) (RevMan 2014) to create 'Summary of findings' tables using information on quality of evidence, magnitude of effects of the interventions examined, and sums of available data on all important outcomes from each study included in the comparison. The GRADE approach (Schünemann 2011) considers ‘quality’ to be a judgement of the extent to which we can be confident that the estimates of effect are correct. We initially graded evidence from RCTs as high, it was downgraded by one or two levels on each of five domains after full consideration of any limitations in the design of studies including risk of bias, indirectness of the evidence, inconsistency and imprecision of results and the possibility of publication bias. We upgraded the quality of evidence by one or two levels on three domains, including large magnitude of the effect, the influence of all possible residual confounding and the dose‐response gradient. A GRADE quality level of 'high' reflects confidence that the true effect lies close to the estimate of the effect for a given outcome. A judgement of 'moderate' quality indicates that the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but acknowledges that it could be substantially different. Evidence of 'low' and 'very low' quality limits our confidence in the effect estimate. The outcomes selected for the 'Summary of findings' tables include the following.

High‐intensity pain with low dose lidocaine admixture ‐ lidocaine ≤ 20 mg or ≤ 0.2 mg/kg admixture

High‐intensity pain with high dose lidocaine admixture ‐ lidocaine > 20 mg or > 0.2 mg/kg admixture

High‐intensity pain with low dose lidocaine pretreatment ‐ lidocaine ≤ 20 mg or ≤ 0.2 mg/kg pretreatment alone

High‐intensity pain with high dose lidocaine pretreatment ‐ lidocaine > 20 mg or > 0.2 mg/kg pretreatment alone

High‐intensity pain with low dose lidocaine pretreatment ‐ lidocaine ≤ 20 mg or ≤ 0.2 mg/kg pretreatment with venous occlusion

High‐intensity pain with high dose lidocaine pretreatment ‐ lidocaine > 20 mg or > 0.2 mg/kg pretreatment with venous occlusion

Results

Description of studies

See the Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

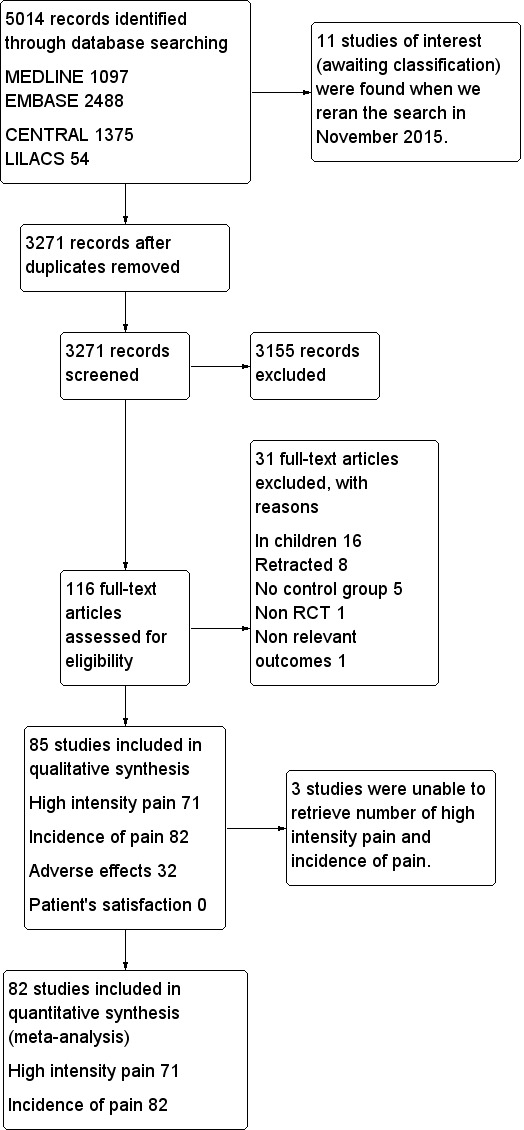

Results of the search

In October 2014, the search retrieved 5014 articles. We judged 116 studies to be potentially eligible and retrieved the full texts; 85 studies met our inclusion criteria and 31 studies were excluded, 82 studies were eligible for quantitative analysis. We reran the search in November 2015. 11 potential new studies of interest were added to the list of ‘Studies awaiting classification' and will be incorporated into the formal review findings during the review update. No disagreement between review authors regarding inclusion of studies was observed. See PRISMA study flow diagram (Figure 1) for further details (Liberati 2009).

1.

PRISMA study flow diagram

Included studies

Study design

We included 85 parallel‐design RCTs in this review; 82 studies were eligible for quantitative analysis.

Sample size

The number of participants analysed in the 82 included studies ranged from 36 to 464.

Setting

All of the included studies were single‐centre studies conducted in high‐, middle‐ and low‐income countries worldwide. Most of the included studies (59/85) were performed in Asia. There were 18 studies from Europe (Bachmann‐Mennenga 2007; Barker 1991; Eriksson 1997; Gajraj 1996; Gehan 1991; Harmon 2003; Helbo‐Hansen 1988; Johnson 1990; Lyons 1996; Mallick 2007; McCluskey 2003; McCulloch 1985; McDonald 1996; Niazi 2005; Nicol 1991; Nathanson 1996; Scott 1988; Smith 1996); seven studies from North America (Aldrete 2010; Ahmad 2013; Ganta 1992; Haugen 1995; Minogue 2005; O'Hara 1997; Walker 2011); two studies from Australia (Lee 1994; Newcombe 1990); and one study from Africa (Saadawy 2007).

Funding

Eight studies (Asik 2003; Bachmann‐Mennenga 2007; Ho 1999; Jeon 2012; Krobbuaban 2008; Kwak 2007b; Kwon 2012; Walker 2011) were supported by government hospital or university funds and one study (Helbo‐Hansen 1988) was funded by a charitable grant while three out of 85 studies (Aldrete 2010; Bachmann‐Mennenga 2007; McCulloch 1985) were funded or supplied propofol by the pharmaceutical manufacturer with a commercial interest in the results of the studies.

Participants

This review included 10,350 participants; 5597 of whom were in the lidocaine group and 4753 in the control group. All participants were American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) I‐III patients undergoing elective surgery and administered propofol for induction of anaesthesia. The age of participants ranged from 13 years to 89 years.

Intervention

All studies compared lidocaine versus placebo. Twelve of the 85 studies used an adjunct with lidocaine versus an adjunct with placebo: remifentanil (Aouad 2007; Han 2010; Kwak 2007a; Kwak 2007b), nitroglycerine ointment (O'Hara 1997), 50%N2O (Kim 2013a; Niazi 2005; Sinha 2005), sevoflurane (DeSousa 2011), dexamethasone (Kwak 2008), ketamine (Hwang 2010), dexmedetomidine (Ayoglu 2007). In our review, there were some included studies with multiple intervention groups (DeSousa 2011; Gajraj 1996; Gehan 1991; Ho 1999; Johnson 1990; Kim 2010; Massad 2006; Scott 1988), therefore, we split the shared group into two or more groups with a smaller sample size and included two or more (reasonably independent) comparisons, as mentioned in 'Unit of analysis issues'. The dose of lidocaine and injection techniques were classified into six subgroups as follows:

23/85 studies used a dose of ≤ 20 mg or ≤ 0.2 mg/kg of lidocaine‐propofol admixture (Bachmann‐Mennenga 2007; Barker 1991; Gajraj 1996; Gehan 1991; Harmon 2003; Helbo‐Hansen 1988; Ho 1999; Johnson 1990; Kim 2010; King 1992; Krobbuaban 2008; Kwak 2007b; McDonald 1996; Minogue 2005; Newcombe 1990; O'Hara 1997; Parmar 1998; Scott 1988; Sethi 2009; Tariq 2006; Tariq 2010; Tham 1995; Yew 2005).

19/85 studies used a dose of > 20 mg or > 0.2 mg/kg of lidocaine‐propofol admixture (Aldrete 2010; Aouad 2007; Gajraj 1996; Gehan 1991; Han 2010; Ho 1999; Johnson 1990; Karasawa 2000; Kim 2010; Krobbuaban 2005; Mallick 2007; Massad 2006; McCluskey 2003; Nakane 1999; Nathanson 1996; Sinha 2005; Tham 1995; Walker 2011; Yokota 1997).

7/85 studies used a dose of ≤ 20 mg or ≤ 0.2 mg/kg lidocaine pretreatment alone (Ganta 1992; Lee 1994; Lyons 1996; McCulloch 1985; Nicol 1991; Scott 1988; Smith 1996).

14/85 studies used a dose of > 20 mg or > 0.2 mg/kg lidocaine pretreatment alone (Agarwal 2004b; Agarwal 2004d; Azma 2004; Cheong 2002; DeSousa 2011; Haugen 1995; Honarmand 2008; Koo 2006; Lu 2013; Massad 2006; Nishiyama 2005; Salman 2011; Shimizu 2005; Zahedi 2009).

9/85 studies used a dose of ≤ 20 mg or ≤ 0.2 mg/kg lidocaine pretreatment with venous occlusion (Asik 2003; Batra 2005; Burimsittichai 2006; Jeon 2012; Johnson 1990; Kwak 2007a; Kwak 2008; Kwon 2012; Scott 1988).

25/85 studies used a dose of > 20 mg or > 0.2 mg/kg lidocaine pretreatment with venous occlusion (Ayoglu 2007; Agarwal 2004a; Agarwal 2004c; Ahmad 2013; Akgun 2013; Apiliogullari 2007; Borazan 2010; Canbay 2008; DeSousa 2011; Dubey 2003; El‐Radaideh 2007; Hwang 2010; Johnson 1990; Kim 2013a; Kim 2013b; Liaw 1999; Massad 2006; Niazi 2005; Ozgul 2013; Pang 1998; Pang 1999; Reddy 2001; Saadawy 2007; Walker 2011; Wong 2001).

Outcomes

All studies assessed the pain intensity by different pain scales and reported in different ways as follow.

71/85 studies reported both incidence of high‐intensity pain and incidence of pain.

11/85 studies reported only incidence of pain (El‐Radaideh 2007; Haugen 1995; Johnson 1990; Kim 2013a; Liaw 1999; Mallick 2007; McCulloch 1985; Pang 1998; Scott 1988; Tham 1995; Walker 2011).

2/85 studies reported only mean and standard deviation of pain‐intensity which were not included in meta‐analysis (Ayoglu 2007; Eriksson 1997).

1/85 studies reported only percentage of pain reduction which was not included in meta‐analysis (Polat 2012).

32/85 studies reported adverse effects (Agarwal 2004a; Agarwal 2004b; Agarwal 2004c; Agarwal 2004d; Akgun 2013; Apiliogullari 2007; Ayoglu 2007; Borazan 2010; Canbay 2008; Cheong 2002; Dubey 2003; Ganta 1992; Han 2010; Honarmand 2008; Jeon 2012; Johnson 1990; Kim 2013a; Koo 2006; Krobbuaban 2005; Krobbuaban 2008; Kwak 2007a; Kwak 2008; Kwon 2012; Liaw 1999; McCulloch 1985; Nakane 1999; Ozgul 2013; Pang 1999; Saadawy 2007; Smith 1996; Tham 1995; Zahedi 2009).

None of the studies reported patient satisfaction levels.

See Characteristics of included studies table for more details.

Excluded studies

We excluded 31 studies for the following reasons.

16/31 were studies in paediatric patients (Barbi 2003; Beh 2002; Cameron 1992; Cheng 1998; Depue 2013; Hiller 1992; Kaabachi 2007; Kwak 2009; Lembert 2002; Morton 1990; Nyman 2005; Nyman 2006; Pollard 2002; Rahman 2007; Rochette 2008; Valtonen 1989).

8/31 were retracted after publishing (Fujii 2004; Fujii 2005a; Fujii 2005b; Fujii 2006; Fujii 2008; Fujii 2009; Fujii 2011; Roehm 2003).

5/31 had no placebo‐controlled group (Brock 2010; Chaudhary 2013; Fujii 2007; Lee 2004; Massad 2008).

1/31 reported non‐relevant outcomes (So 2013).

1/31 was letter‐to‐editor and non randomized controlled trial (Ewart 1990).

see Characteristics of excluded studies for more details.

Studies awaiting classification

Eleven studies (Alipour 2014; Byon 2014; Galgon 2015; Gharavi 2014; Goktug 2015; Kim 2014a; Kim 2014b; Le Guen 2014; Lee 2011; Singh 2014; Terada 2014) are awaiting classification.

See the Characteristics of studies awaiting classification for more details.

Ongoing studies

There are no ongoing studies.

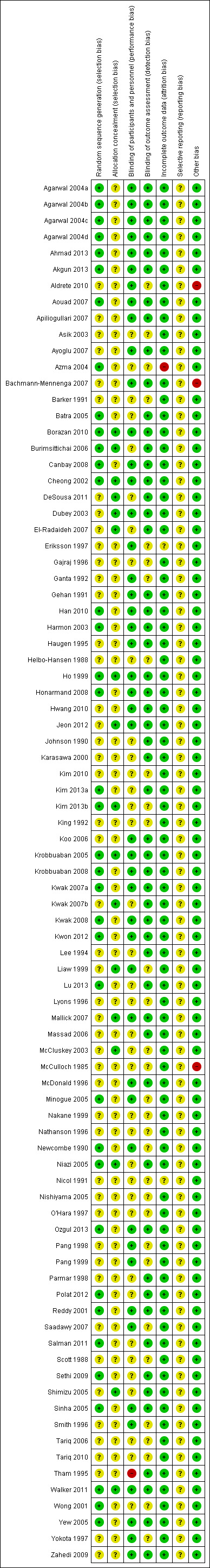

Risk of bias in included studies

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

All of the studies reported that the study was randomized but only 37 of 85 studies (43.5%) provided adequate sequence generation. Also, 17 of 85 (20%) mentioned adequate method of allocation concealment. No studies were assessed as high risk of selection bias.

Blinding

Most of the studies blinded participants, personnel and outcome assessors. The injected solution was prepared by an another person not involved in the investigation. Forty‐seven of 85 studies (55.3%) reported adequate blinding of participants and personnel. Only one study (Tham 1995) was judged as high risk of performance bias as the study mentioned that propofol was administered by the same person who prepared the mixture. However, 54 studies (63.5%) reported adequate blinding of outcome assessor.

Incomplete outcome data

Sixty‐five studies (76.5%) reported no withdrawal of participants after randomization. Seventeen studies (20%) reported that fewer than 15% of recruited participants dropped out and provided the reasons for their exclusions (Bachmann‐Mennenga 2007; Harmon 2003; Hwang 2010; Kim 2013a; Kim 2013b; King 1992; Krobbuaban 2005; Krobbuaban 2008; Kwak 2007a; Kwak 2007b; Kwak 2008; Kwon 2012; Mallick 2007; McDonald 1996; Newcombe 1990; Ozgul 2013; Sinha 2005). Only one study was assessed as high risk of attrition bias (Azma 2004). This study excluded 43 out of 180 patients (more than 15%) but reported only 20 excluded patients due to difficulty in cephalic venous catheterization and seven due to incidence of pain and severity beyond the expectations of the investigator, but other exclusions were not described. Also most of the excluded participants were in the control group. Another study (Nicol 1991) was judged as unclear risk of attrition bias. This is because the study reported that ten of 283 patients were excluded and provided the reason that more operations in one group were cancelled after randomization than in the other two groups. However, there was no information regarding the number of exclusions in each group. Moreover, a study by Eriksson 1997, which was not included in meta‐analysis, did not report some missing data. Total injections in this study were 88 injections (44 participants were injected both hands) but the study reported only 71 injections. No explanation of missing data were described.

Selective reporting

The assessment of selective reporting outcome was unclear in all studies because we could not access the study protocols.

Other potential sources of bias

Most of the included studies demonstrated a low risk of other potential sources of bias. Only three studies (Aldrete 2010; Bachmann‐Mennenga 2007; McCulloch 1985) were funded or supplied propofol by the pharmaceutical company and therefore were judged as high risk of other sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

See Table 1 Lidocaine for reducing propofol‐induced pain on induction of anaesthesia in adults.

Primary outcome: high‐intensity pain

There were 71 studies including a total of 8845 participants. Most of the studies assessed pain intensity by using 4‐point scales, although seven studies used 3‐point scales (Apiliogullari 2007; Asik 2003; DeSousa 2011; Massad 2006; Newcombe 1990; Nishiyama 2005; Wong 2001), one study, Azma 2004 used a 6‐point scale, and two studies, Kim 2013b; Pang 1999 used 11‐point scales. The overall incidence of high‐intensity pain in the control group was 37.9% (95% CI 33.4% to 43.1%) whereas in the lidocaine group it was only 11.8% (95% CI 9.7% to 13.8%). The number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) was 3.8.

Subgroup analysis

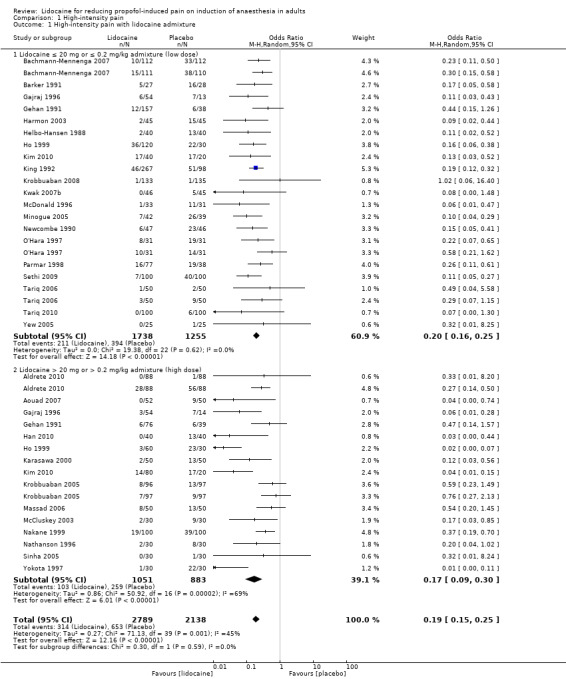

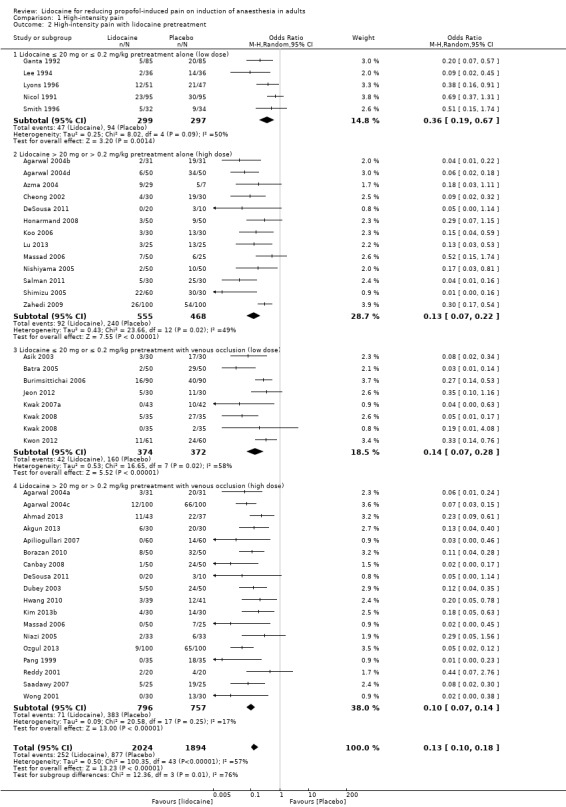

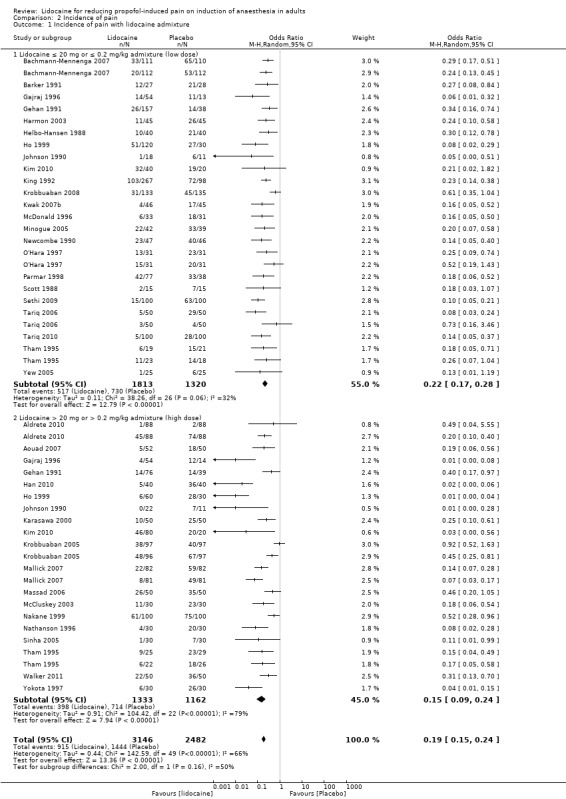

High‐intensity pain with lidocaine admixture (Analysis 1.1)

According to 31 of 71 studies, the percentage of high‐intensity pain in the control group was 30.5%, compared to 11.3% in the lidocaine admixture group. In other words, the magnitude (risk ratio reduction) of lidocaine admixture to reduce high‐intensity pain following propofol injection was 63%.

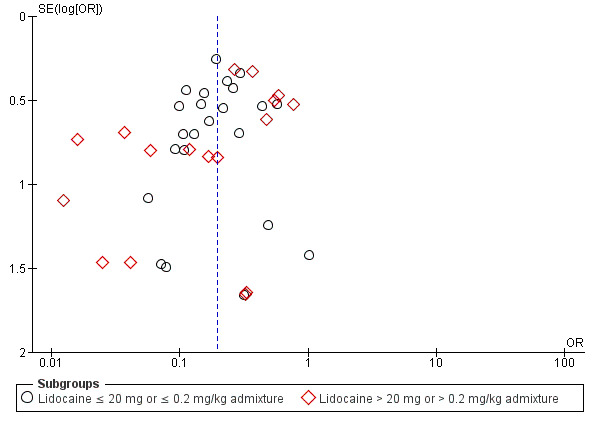

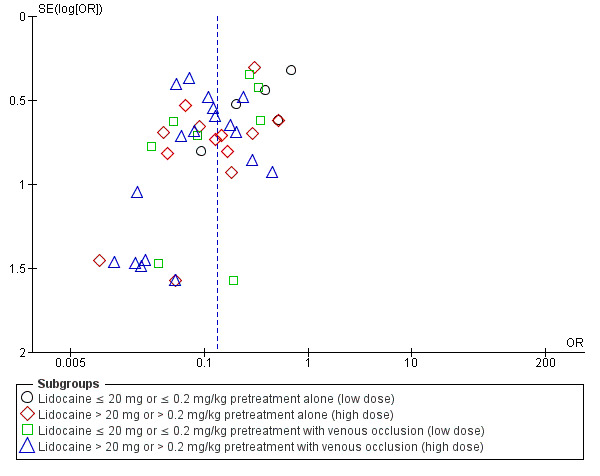

The overall effect of the random‐effects meta‐analysis favoured lidocaine admixture with a statistically significant benefit for high‐intensity pain (OR 0.19, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.25, 31 RCTs, 4927 participants, I2 = 45%, Tau2 = 0.27, high‐quality evidence, Analysis 1.1. The direction of the result was similar when we conducted the sensitivity analysis of studies with low risk of selection bias (OR 0.20, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.83, two RCTs (Ho 1999; Krobbuaban 2005), 627 participants, I2 = 87%, Tau2 = 1.87). The visual inspection of the funnel plot presented roughly symmetrical results around the overall effect, OR 0.19, this indicated that there might be no publication bias (Figure 4).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 High‐intensity pain, Outcome 1 High‐intensity pain with lidocaine admixture.

4.

Funnel plot of outcome: High‐intensity pain with lidocaine admixture

Low dose lidocaine admixture (≤ 20 mg or ≤ 0.2 mg/kg): 20 studies (Bachmann‐Mennenga 2007; Barker 1991; Gajraj 1996; Gehan 1991; Harmon 2003; Helbo‐Hansen 1988; Ho 1999; Kim 2010; King 1992; Krobbuaban 2008; Kwak 2007b; McDonald 1996; Minogue 2005; Newcombe 1990; O'Hara 1997; Parmar 1998; Sethi 2009; Tariq 2006; Tariq 2010; Yew 2005), 2993 participants were analysed with OR 0.20, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.25, I2 = 0%.

High dose lidocaine admixture (> 20 mg or > 0.2 mg/kg): 15 studies (Aldrete 2010; Aouad 2007; Gajraj 1996; Gehan 1991; Han 2010; Ho 1999; Karasawa 2000; Kim 2010; Krobbuaban 2005; Massad 2006; McCluskey 2003; Nakane 1999; Nathanson 1996; Sinha 2005; Yokota 1997), 1934 participants were analysed with OR 0.17, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.30, I2= 69%.

There was no significant difference between these two subgroups (Analysis 1.1; Chi² test = 0.30, df = 1 (P = 0.59), I² = 0%).

High‐intensity pain with lidocaine pretreatment (Analysis 1.2)

For lidocaine pretreatment, the statistically significant benefit was also observed (OR 0.13, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.18, 41 RCTs, 3918 participants, I2 statistic = 57%, Tau2 = 0.50, high‐quality evidence, Analysis 1.2. The sensitivity analysis which excluded studies with unclear and high risk of selection bias did not affect the direction of the result nor the statistical significance of high‐intensity pain (OR 0.18, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.29, five RCTs (Borazan 2010; Burimsittichai 2006; Cheong 2002; Kim 2013b; Niazi 2005), 466 participants, I2 = 0%, Tau2 = 0.00, Figure 5). We found the funnel plot to be asymmetrical (the absence of negative studies) (Figure 6), demonstrating the likelihood of publication bias.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 High‐intensity pain, Outcome 2 High‐intensity pain with lidocaine pretreatment.

5.

Sensitivity analysis for low risk of selection bias of outcome: High‐intensity pain with lidocaine pretreatment

6.

Funnel plot of outcome: High‐intensity pain with lidocaine pretreatment

This category comprised two doses of lidocaine regimen (low dose: ≤ 20 mg or ≤ 0.2 mg/kg lidocaine and high dose: > 20 mg or > 0.2 mg/kg lidocaine) with two different techniques of administration (with or without venous occlusion). A total of 41 studies were included with 3918 patients. Similar to lidocaine admixture, the percentage of patients with high‐intensity pain decreased from 46.3% in the control group to 12.5% in the lidocaine pretreatment group, which is 73% risk ratio reduction. Furthermore, all of the four different techniques of lidocaine administration in subgroup analysis showed a very good result in reducing pain on propofol injection. Accordingly, low dose lidocaine pretreatment without venous occlusion seemed to be the least effective treatment (OR 0.36, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.67, I2 = 50%).

Low dose lidocaine pretreatment alone (≤ 20 mg or ≤ 0.2 mg/kg): five studies (Ganta 1992; Lee 1994; Lyons 1996; Nicol 1991; Smith 1996), 596 participants were analysed with OR 0.36, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.67, I2 = 50%.

High dose lidocaine pretreatment alone (> 20 mg or > 0.2 mg/kg): 13 studies (Agarwal 2004b; Agarwal 2004d; Azma 2004; Cheong 2002; DeSousa 2011; Honarmand 2008; Koo 2006; Lu 2013; Massad 2006; Nishiyama 2005; Salman 2011; Shimizu 2005; Zahedi 2009), 1023 participants were analysed with OR 0.13, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.22, I2 = 49%.

Low dose lidocaine pretreatment with venous occlusion (≤ 20 mg or ≤ 0.2 mg/kg): seven studies (Asik 2003; Batra 2005; Burimsittichai 2006; Jeon 2012; Kwak 2007a; Kwak 2008; Kwon 2012), 746 participants were analysed with OR 0.14, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.28, I2 = 58%.

High dose lidocaine pretreatment with venous occlusion (> 20 mg or > 0.2 mg/kg): 18 studies (Agarwal 2004a; Agarwal 2004c; Ahmad 2013; Akgun 2013; Apiliogullari 2007; Borazan 2010; Canbay 2008; DeSousa 2011; Dubey 2003; Hwang 2010; Kim 2013b; Massad 2006; Niazi 2005; Ozgul 2013; Pang 1999; Reddy 2001; Saadawy 2007; Wong 2001), 1553 participants were analysed with OR 0.10, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.14, I2 = 17%.

There was a significant difference among these subgroups (Analysis 1.2; Chi² test = 12.36, df = 3 (P = 0.006), I² = 75.7%).

Both the lidocaine pretreatment subgroup (OR 0.13, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.18, I2 = 57%, high‐quality evidence) and the lidocaine admixture subgroup (OR 0.19, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.25, I2 = 45%, high‐quality evidence) demonstrated a very large effect size for reducing pain on propofol injection.

Secondary outcomes

Incidence of pain

All 82 studies (total of 10,350 participants) reported incidence of pain. The pain intensity was assessed using 2‐point scales in one study (El‐Radaideh 2007), 3‐point scales in ten studies (Apiliogullari 2007; Asik 2003; DeSousa 2011; Johnson 1990; Massad 2006; McCulloch 1985; Newcombe 1990; Nishiyama 2005; Tham 1995; Wong 2001), 4‐point scales in 64 studies, 6‐point scales in one study (Azma 2004), and 11‐point scales in eight studies (Haugen 1995; Kim 2013a; Kim 2013b; Liaw 1999; Mallick 2007; Pang 1998; Pang 1999; Walker 2011). The overall incidence of pain was significantly decreased from 63.7% (95% CI 60% to 67.9%) in the control group to about 30.2% (95% CI 26.7% to 33.7%) in the lidocaine group. The number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) was 3.0. Both the admixture and pretreatment with lidocaine groups saw a reduction in the incidence of pain, with OR varying from 0.11 to 0.40.

Subgroup analysis

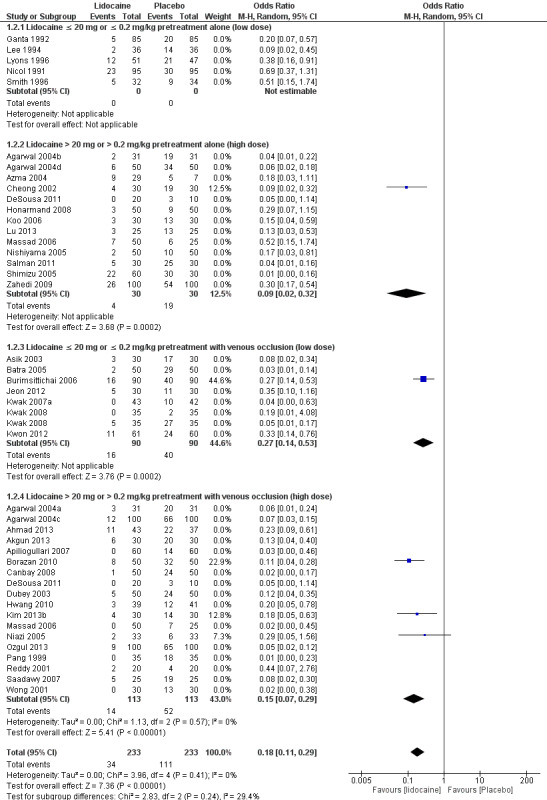

Incidence of pain with lidocaine admixture (Analysis 2.1)

There were 36 studies included in this subgroup with a total of 5628 participants (Aldrete 2010; Aouad 2007; Bachmann‐Mennenga 2007; Barker 1991; Gajraj 1996; Gehan 1991; Han 2010; Harmon 2003; Helbo‐Hansen 1988; Ho 1999; Johnson 1990; Karasawa 2000; Kim 2010; King 1992; Krobbuaban 2005; Krobbuaban 2008; Kwak 2007b; Mallick 2007; Massad 2006; McCluskey 2003; McDonald 1996; Minogue 2005; Nakane 1999; Nathanson 1996; Newcombe 1990; O'Hara 1997; Parmar 1998; Scott 1988; Sethi 2009; Sinha 2005; Tariq 2006; Tariq 2010; Tham 1995; Walker 2011; Yew 2005; Yokota 1997).

The overall effect of the random effects meta‐analysis favoured lidocaine admixture with a statistically significant reduction of incidence of pain (OR 0.19, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.24, 36 RCTs, 5628 participants, I2 = 66%, Tau2 = 0.44, high‐quality evidence). A premixed high dose of lidocaine > 20 mg or > 0.2 mg/kg with propofol (OR 0.15, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.24, 19 RCTs, 2495 participants, high‐quality evidence) or premixed low dose regimen (lidocaine ≤ 20 mg or ≤ 0.2mg/kg; OR 0.22, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.28, 23 RCTs, 3133 participants, high‐quality evidence) was comparably effective in preventing propofol‐induced pain.

Low dose lidocaine admixture (≤ 20 mg or ≤ 0.2 mg/kg): 23 studies (Bachmann‐Mennenga 2007; Barker 1991; Gajraj 1996; Gehan 1991; Harmon 2003; Helbo‐Hansen 1988; Ho 1999; Johnson 1990; Kim 2010; King 1992; Krobbuaban 2008; Kwak 2007b; McDonald 1996; Minogue 2005; Newcombe 1990; O'Hara 1997; Parmar 1998; Scott 1988; Sethi 2009; Tariq 2006; Tariq 2010; Tham 1995; Yew 2005), 3133 participants were analysed with OR 0.22, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.28, I2= 32%.

High dose lidocaine admixture (> 20 mg or > 0.2 mg/kg): 19 studies (Aldrete 2010; Aouad 2007; Gajraj 1996; Gehan 1991; Han 2010; Ho 1999; Johnson 1990; Karasawa 2000; Kim 2010; Krobbuaban 2005; Mallick 2007; Massad 2006; McCluskey 2003; Nakane 1999; Nathanson 1996; Sinha 2005; Tham 1995; Walker 2011; Yokota 1997), 2495 participants were analysed with OR 0.15, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.24, I2 = 79%.

There was no significant difference between the two subgroups (Analysis 2.1; Chi² test = 2.00, df = 1 (P = 0.16), I² = 49.9%).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Incidence of pain, Outcome 1 Incidence of pain with lidocaine admixture.

Incidence of pain with lidocaine pretreatment (Analysis 2.2)

There were 50 studies with 4722 participants included in this outcome. A statistically significant benefit was also demonstrated with lidocaine pretreatment (OR 0.14, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.18, 50 RCTs, 4722 participants, I2 = 62%, Tau2 = 0.49, high‐quality evidence). For the subgroup analysis, The high or low dose lidocaine, with or without venous occlusion, similarly demonstrated a good efficacy for decreasing the incidence of pain following propofol injection. However, the low dose lidocaine pretreatment alone (OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.55, seven studies, 713 participants, high‐quality evidence) appeared to be the least effective technique.

Low dose lidocaine pretreatment alone (≤ 20 mg or ≤ 0.2 mg/kg): seven studies (Ganta 1992; Lee 1994; Lyons 1996; McCulloch 1985; Nicol 1991; Scott 1988; Smith 1996), 713 participants were analysed with OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.55, I2 = 0%.

High dose lidocaine pretreatment alone (> 20 mg or > 0.2 mg/kg): 14 studies (Agarwal 2004b; Agarwal 2004d; Azma 2004; Cheong 2002; DeSousa 2011; Haugen 1995; Honarmand 2008; Koo 2006; Lu 2013; Massad 2006; Nishiyama 2005; Salman 2011; Shimizu 2005; Zahedi 2009), 1083 participants were analysed with OR 0.13, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.20, I2 = 40%.

Low dose lidocaine pretreatment with venous occlusion (≤ 20 mg or ≤ 0.2 mg/kg): nine studies (Asik 2003; Batra 2005; Burimsittichai 2006; Jeon 2012; Johnson 1990; Kwak 2007a; Kwak 2008; Kwon 2012; Scott 1988), 801 participants were analysed with OR 0.13, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.29, I2= 79%.

High dose lidocaine pretreatment with venous occlusion (> 20 mg or > 0.2 mg/kg): 24 studies (Agarwal 2004a; Agarwal 2004c; Ahmad 2013; Akgun 2013; Apiliogullari 2007; Borazan 2010; Canbay 2008; DeSousa 2011; Dubey 2003; El‐Radaideh 2007; Hwang 2010; Johnson 1990; Kim 2013a; Kim 2013b; Liaw 1999; Massad 2006; Niazi 2005; Ozgul 2013; Pang 1998; Pang 1999; Reddy 2001; Saadawy 2007; Walker 2011; Wong 2001), 2125 participants were analysed with OR 0.11, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.15, I2 = 26%.

There was a significant difference between these four subgroups (Analysis 2.2; Chi² test = 40.05, df = 3 (P < 0.00001), I² = 92.5%).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Incidence of pain, Outcome 2 Incidence of pain with lidocaine pretreatment.

Adverse effects

32 studies (Agarwal 2004a; Agarwal 2004b; Agarwal 2004c; Agarwal 2004d; Akgun 2013; Apiliogullari 2007; Ayoglu 2007; Borazan 2010; Canbay 2008; Cheong 2002; Dubey 2003; Ganta 1992; Han 2010; Honarmand 2008; Jeon 2012; Johnson 1990; Kim 2013a; Koo 2006; Krobbuaban 2005; Krobbuaban 2008; Kwak 2007a; Kwak 2008; Kwon 2012; Liaw 1999; McCulloch 1985; Nakane 1999; Ozgul 2013; Pang 1999; Saadawy 2007; Smith 1996; Tham 1995; Zahedi 2009), 4007 participants were analysed for adverse effects (OR not estimated, low‐quality evidence). An adverse effect, thrombophlebitis, was observed in two studies (Ganta 1992; Smith 1996).

One study (Ganta 1992) reported thrombophlebitis: 4/85 participants in the lidocaine 10 mg pretreatment group compared with 8/85 cases in the saline group.

Another study (Smith 1996) reported thrombophlebitis within seven days postoperatively by self‐assessment questionnaire. The incidence of thrombophlebitis was 9/22 participants in the lidocaine 20 mg pretreatment group, compared to 4/29 in the saline group. However, there were no statistically significant differences in the two groups.

According to the GRADE approach to consider the quality of the evidence, we downgraded the quality of evidence by two levels due to serious imprecision and inconsistency.

Patient's satisfaction

None of the studies described patient satisfaction in the reports.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Lidocaine, both administered by admixture and pretreatment (Table 1) could significantly reduce high‐intensity pain levels and decrease the incidence of pain. In subgroup analyses, there were no significant differences in the efficacy (with very large effect size) among two different techniques of lidocaine admixture administration for reducing propofol injection pain. However, there was a significant difference in the efficacy among four different techniques of lidocaine pre‐treatment administration for reducing propofol injection pain. Low dose lidocaine (≤ 20 mg or ≤ 0.2 mg/kg) pretreatment alone appeared to provide the least efficacy (with large effect size) in reducing and preventing propofol‐induced pain. Thrombophlebitis was an adverse effect reported in only two studies (Ganta 1992; Smith 1996) which was not significantly different between lidocaine and placebo groups.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Our review included studies conducted worldwide with low risk of bias in all except two domains, allocation concealment and selective reporting bias. Participants of the included studies were adults up to 89 years old. The level of pain intensity was reported in 71 of 82 studies while 33 studies reported adverse effects. Interestingly, no study reported patient satisfaction. This might be because there are many factors which influence the level of patient satisfaction, such as discomfort from sore throat after intubation, or postoperative pain, making it difficult to measure. Regrettably, patient satisfaction is a key outcome to present: it is important whether patients considered such pain was significant. In addition, there were many scoring systems for pain assessment in the different studies. However, most of the included studies used 4‐point scales as an outcome measure rather than a validated pain scale, such as visual analogue score or numerical rating score. This was probably because 11‐point scales might have been too complicated for patients under the induction process.

Generally, application of the review’s findings to clinical practice is possible since lidocaine is a cheap and easily available drug throughout the world. Premixed lidocaine with propofol has been well‐accepted (Kim 2010; Scott 1988; Tariq 2006). Subgroup analysis of the dose of lidocaine suggested that a higher dose is more effective for reducing and preventing propofol‐induced pain than a lower dose in both admixture and pretreatment groups. The most common high dose used in the included studies was 40 mg, double that in the low dose lidocaine group. The maximum dose was 100 mg (5 ml of 2% lidocaine) in Aldrete 2010, which is common for attenuation of haemodynamic response to intubation in clinical practice; however, there were no adverse effects detected.

Picard 2000 suggested that the combination of high dose lidocaine pretreatment and venous occlusion is more effective than the other lidocaine administration techniques to reduce the incidence of propofol injection pain. This is because venous occlusion with a tourniquet allowed high concentrations of the drug to be retained locally, extending the analgesic time. The procedure of pretreatment with venous occlusion involves more steps to start the anaesthesia, however and the efficacy of pretreatment with venous occlusion and without venous occlusion was not significantly different. Therefore it is not a popular strategy for many anaesthesiologists. Another reason is that, in some circumstances, such as in rapid sequence induction, it may not be appropriate to perform pretreatment with venous occlusion. A subsequent systematic review (Jalota 2011) recommended using the antecubital vein instead of a vein in the hand, as it was an equally effective method, and accessing the antecubital vein was relatively simple. However, it was quite unpopular because it is easy to dislodge intravenous lines when patients flex their elbows, and the hand vein proves more comfortable to the patient than the antecubital vein does.

Regarding our review, the result also showed that there were no significant differences among six subgroups. Therefore, we would recommend lidocaine administration by any method (low dose/high dose; premixed/pretreatment; with/without venous occlusion), depending on the anaesthesiologists’ circumstances and appropriateness, to provide effective pain reduction following propofol injection.

Quality of the evidence

We included 82 studies, with 10,350 participants for quantitative analysis. The overall risk of bias of most individual studies ranged from 'low' to 'unclear'. In terms of blinding, 48 studies were described as randomized, double blinded, controlled trials. However in the studies described as single blinded (four studies: Azma 2004; Barker 1991; DeSousa 2011; Tham 1995) or only randomized controlled trials (30 studies), the authors provided explicit detail about investigator blinding. Nevertheless the participants were likely to be blinded, as the injection of study drugs was done in the same manner for both the lidocaine and placebo groups. There was unclear risk of selection bias from inadequate information about sequence generation in 38 studies, and only 19 studies mentioned allocation concealment (see Figure 3). However the result was similar when sensitivity analysis of studies with low risk of selection bias was done. Only one study (Tham 1995) had high risk of performance bias, since propofol was injected by the same person who prepared the study drug (n = 183). We judged the risk of attrition bias as high in one study (Azma 2004) (n = 137) since more than 15% of participants were excluded without clear reasons reported for all excluded cases. There was also unclear risk of attrition bias in another study (Nicol 1991) (n = 283) as the number of excluded participants was not reported per group. The risk of reporting bias in all studies was unclear as the study protocols could not be accessed. There were also three studies (Aldrete 2010; Bachmann‐Mennenga 2007; McCulloch 1985) with high risk of other potential sources of bias as the studies were funded or supplied propofol by a pharmaceutical company. Furthermore the benefit of lidocaine pretreatment was interpreted with caution since there might be evidence of publication bias due to small study effect (Figure 6). Co‐treatment such as remifentanil was found in some studies with lidocaine pretreatment (Aouad 2007; Han 2010; Kwak 2007a; Kwak 2007b). This particular co‐treatment possibly confounded the levels of pain. However, when we tried to exclude studies with co‐treatments to confirm the applicability of the data, the results showed that the efficacy of the intervention groups was not changed.

Overall, the quality of the evidence for high‐intensity pain and incidence of pain outcomes with lidocaine admixture and pretreatment was high when using the GRADE approach. Considering 'lidocaine ≤ 20 mg or ≤ 0.2 mg/kg pretreatment alone' and 'lidocaine ≤ 20 mg or ≤ 0.2 mg/kg pretreatment with venous occlusion' subgroups, although the number of events was lower than 300, 95% confidence intervals around absolute effects were narrow. Therefore the quality of evidence for imprecision was not downgraded. Nevertheless, the quality of the evidence for adverse effects outcomes was low due to serious imprecision and inconsistency.

Potential biases in the review process

Despite using comprehensive and systematic searching we may have missed trials that were not indexed in CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE and LILACS, or websites of ongoing trials that remain unpublished in journals. We reran the search strategy in November 2015. We found 11 studies of interest. Those studies were added to a list of ‘Studies awaiting classification' and will be incorporated into the formal review findings during the review update.

There might be a possibility of publication bias as shown in Figure 6 for the effect of lidocaine pretreatment on high‐intensity pain. However, published evidence comprised a considerable number of trials, therefore, we would not consider publication bias in this subgroup.

We clearly stated in our protocol that participants aged over 15 years could be included, however, there was one study (DeSousa 2011) which enrolled participants aged 13 years to 65 years. On the agreement of two authors, we included this study in our review, because patients aged more than 12 years could certainly report pain rating scales (von Baeyer 2006) and body weight was not much different to adults. We were concerned about selective bias and misclassification bias regarding this decision, however the results of the forest plot that included or excluded DeSousa 2011 were no different.

There were eight studies excluded from this review due to retraction (Fujii 2004; Fujii 2005a; Fujii 2005b; Fujii 2006; Fujii 2008; Fujii 2009; Fujii 2011; Roehm 2003). This is very uncommon in this area and seven of the eight retracted papers were from one author. The reason for retraction was fabrication of data detected by journals. The findings of these retracted papers should not have any implications on the current findings. We think that the validity of our findings will be strengthened by excluding fabricated papers.

We were aware that deviating from or changing the protocol may cause potential biases. However, reducing the scope of the interventions and changing subgroup analyses in this review were considered as low potential bias.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

There were two published systematic reviews and meta analyses exploring interventions for reducing pain on injection induced by propofol (Jalota 2011; Picard 2000). Without any intervention the incidence of pain in our review (63.7%) was similar to the results of those two previously reported (60% from Jalota 2011 and 70% from Picard 2000). We could not find any other studies or reviews investigating the effect of lidocaine on the prevention of high‐intensity pain to compare against our review. We found the incidence of high‐intensity pain in the lidocaine group was only 11.8% compared with 37.9% in the control group (NNTH 3.8).

Both systematic reviews identified pretreatment with lidocaine in conjunction with venous occlusion, using a tourniquet above the injection site, to be the most efficacious intervention. With the combination of intravenous lidocaine 40 mg pretreatment and a tourniquet 30 seconds to 120 seconds before injection of propofol, the NNTH to prevent any pain was 1.6 in Picard 2000. Jalota 2011 reported RR 0.29 with the same technique. Our systematic review also confirmed the efficacy of these previous reports. The conjunction between high dose lidocaine (> 20 mg or > 0.2 mg/kg) pretreatment and venous occlusion showed a very large effect size in our review (OR 0.1, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.14). The duration of venous occlusion varied from a period of three seconds to three minutes before propofol injection, which was similar to other reports (Johnson 1990; Picard 2000).

Comparing lidocaine admixture to pretreatment, Picard 2000 reported NNTH was 2.4 in lidocaine admixture, compared with 1.6 in pretreatment with venous occlusion. Conversely, Lee 2004 demonstrated that high dose lidocaine admixture was modestly more effective in reducing incidence of pain than high dose lidocaine pretreatment, and recommended that lidocaine should be added to propofol for induction rather than given before induction. Regarding the findings in our review, however, there was no significant difference between lidocaine pretreatment and admixture for reducing and preventing propofol injection pain.

Adverse effects were rare in our review. Only thrombophlebitis was observed in two studies (Ganta 1992; Smith 1996), which were comparable to previous reviews (Jalota 2011; Picard 2000).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Regarding our results, lidocaine admixture and pretreatment were effective in reducing and preventing pain on propofol injection. As a consequence, lidocaine administration by any method (low dose/high dose; premixed/pretreatment; with/without venous occlusion), depending on the anaesthesiologists’ circumstances and on the appropriateness of the procedure, is beneficial for reducing propofol‐induced pain in adults. The venous occlusion technique may not be suitable for some situations, for example in cases requiring rapid induction, as the procedure takes more time to carry out. In such cases, premixed or pretreatment alone with high dose lidocaine (> 20 mg or > 0.2 mg/kg) may be a preferred option.

Implementation decisions should balance the high degree of certainty in the reduction in pain, low cost and wide availability of lidocaine against the lack of evidence for harms and patient satisfaction identified by this review.

Implications for research.

To date, there are a large number of randomized controlled trials regarding interventions for reducing propofol‐induced pain. Therefore, we would suggest that systematic reviews should be conducted in other aspects, for example, lidocaine for reducing pain caused by propofol injection in children, or opioids for reducing propofol‐induced pain.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 14 December 2016 | Amended | Two recently retracted studies (Fujii 2008; Fujii 2009), were excluded from the review |

Notes

December 2016: two recently retracted studies (Fujii 2008; Fujii 2009), were excluded from the review

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Karen Hovhannisyan for his help in writing the search strategy and search process, Miss Boonruan Kanlayanamatee, Siriraj medical librarian, for her assistance on full article access. Our appreciation also goes to Jane Cracknell (Managing Editor, Cochrane Anaesthesia, Critical and Emergency Care) for co‐ordinating the protocol and review processes.

We thank Andrew Smith (content editor); Andrew Moore, Yoshitaka Fujii, and Stefan Soltesz (peer reviewers); and Anne Lyddiatt (Cochrane Consumer Network) for their help and editorial advice during the preparation of the protocol (Euasobhon 2009) for the systematic review.

We also would like to thank Andrew Smith (content editor), Jing Xie (statistical editor), Yvonne Nyman, Chi Wai Cheung (peer reviewers), Janet Wale (consumer editor), Denise Mitchell (copy editor) for their help and editorial advice during the preparation of this systematic review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Glossary

| Terms | Definition |

| Afferent nerve ending | The distal end of nerve fibre of an sensory neuron that carries nerve impulses from sensory receptors or sense organs toward the central nervous system. |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification | ASA I = A normal healthy patient ASA II = A patient with mild systemic disease ASA III = A patient with severe systemic disease ASA IV = A patient with severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life ASA V = A moribund patient who is not expected to survive without the operation ASA VI = A declared brain‐dead patient whose organs are being removed for donor purposes |

| Bioclusive dressing | A thin, polyurethane, acrylic adhesive‐coated dressing, which is permeable to water and O2, but not bacteria; it prevents scabbing and facilitates epidermal regeneration, compared to wounds treated with dry dressings. |

| Bradykinin | A potent endothelium‐dependent vasodilator, leading to a drop in blood pressure. It also causes contraction of non‐vascular smooth muscle in the bronchus and gut, increases vascular permeability and is also an inflammatory mediator involved in the mechanism of pain. |

| Mallampati classification | Class 0: Ability to see any part of the epiglottis upon mouth opening and tongue protrusion Class I: Soft palate, fauces, uvula, pillars visible Class II: Soft palate, fauces, uvula visible Class III: Soft palate, base of uvula visible Class IV: Soft palate not visible at all |

| Prostaglandins | A group of physiologically active lipid compounds having diverse hormone‐like effects and also involved in inflammatory process. |

Appendix 2. Physicopharmacological interventions

| Pretreatment | Admixtured with propofol | Miscellaneous |

| Lidocaine | Lidocaine | Cold temperature |

| Venous occlusion with lidocaine | Thiopental | Warm temperature |

| Lidocaine + metoclopramide | Ketamine | pH adjusted |

| Epidural anaesthesia with lidocaine | 5% dextrose in Ringer's acetate solution | Bacteriostatic saline containing benzyl alcohol |

| Fentanyl | MCT/LCT propofol | |

| Alfentanyl | 0.5% diluted propofol | |

| Remifentanil | Lipid‐free propofol | |

| Remifentanyl + lidocaine | Microfiltation | |

| Meperidine | Aspiration of blood | |

| Ketamine | Target‐controlled propofol | |

| Thiopental | Double lumen intravenous set | |

| Butorphanol | Low‐dose propofol | |

| Flurbiprofen | ||

| Venous occlusion with flurbiprofen axetil | ||

| Ondansetron | ||

| Granisetron | ||

| Dolasetron | ||

| Ephedrine | ||

| Clonidine‐ephedrine | ||

| Oral clonidine | ||

| Metoclopramide | ||

| Dexmedetomidine | ||

| Magnesium sulphate | ||

| Ketolorac | ||

| Diclofenac | ||

| Metoprolol | ||

| Topical nitroglycerine | ||

| Cold saline | ||

| Acetaminophen + lidocaine | ||

| Diphenhydramine | ||

| Nitrous oxide | ||

| Lidocaine and nitrous oxide in oxygen | ||

| Neostigmine | ||

| Tramadol | ||

| Nafamostat mesylate | ||

| Prilocaine |

Appendix 3. Search strategy for CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library

#1 propofol* and pain*

#2 Dolasetron or Remifentanil or Lidocaine or Fentanylor Alfentanil or Pethidineor KETAMINE or THIOPENTAL or Butorphanol or ONDANSETRON or GRANISETRON or EPHEDRINE or CLONIDINE or METOCLOPRAMIDE or DEXMEDETOMIDINE or Magnesium Sulfate or Ketorolac or DICLOFENAC or METOPROLOL or Glyceryl Trinitrate or Cold saline or Acetaminophen or Paracetamol or DIPHENHYDRAMINE or Nitrous Oxide or Neostigmine or Tramadol or Nafamostat mesilate or Prilocaine or PRILOCAINE

#3 temperature near (cold or warm)

#4 (#1 AND ( #2 OR #3 ))

Appendix 4. Search strategy for Ovid MEDLINE (1950 to present)

#1 exp Propofol/ or propofol*.mp.

#2 (propofol adj6 (induc* or relat*)).mp.

#3 #1 or #2

#4 pain.mp. or exp Pain/

#5 #4 and #3

#6 exp Lidocaine/ or Lidocain*.mp.

#7 Fentanyl.mp. or Fentanyl/

#8 Alfentanyl.mp. or Alfentanil/

#9 Meperidine.mp. or Meperidine/

#10 Ketamine.mp. or Ketamine/

#11 Thiopental.mp. or Thiopental/

#12 Butorphanol.mp. or Butorphanol/

#13 Flurbiprofen.mp. or Flurbiprofen/

#14 Ondansetron.mp. or Ondansetron/

#15 Granisetron.mp. or Granisetron/

#16 Ephedrine.mp. or Ephedrine/

#17 clonidine.mp. or Clonidine/

#18 Metoclopramide.mp. or Metoclopramide/

#19 Dexmedetomidine.mp. or Dexmedetomidine/

#20 Magnesium sulfate.mp. or Magnesium Sulfate/

#21 Ketorolac/

#22 Diclofenac.mp. or Diclofenac/

#23 Metoprolol.mp. or Metoprolol/

#24 Nitroglycerin/ or Topical nitroglycerine.mp.

#25 Cold saline.mp.

#26 Acetaminophen.mp. or Acetaminophen/

#27 Diphenhydramine.mp. or Diphenhydramine/

#28 Nitrous oxide.mp. or Nitrous Oxide/

#29 Neostigmine.mp. or Neostigmine/

#30 Tramadol.mp. or Tramadol/

#31 Nafamostat mesilate.mp.

#32 Prilocaine.mp. or Prilocaine/

#33 (temperature adj3 (cold or warm)).mp.

#34 (Dolasetron or Remifentanil).mp.

#35 or/6‐34

#36 #35 and #5

#37 randomised controlled trial.pt.

#38 controlled clinical trial.pt.

#39 randomized.ab.

#40 placebo.ab.

#41 drug therapy.fs.

#42 randomly.ab.

#43 trial.ab.

#44 groups.ab.

#45 or/37‐44

#46 humans.sh.

#47 #45 and #46

#48 #36 and #47

mp = title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word

ti = title

ab = abstract

pt = publication type

fs = floating subject

sh = Medline subject heading (MeSH)

Appendix 5. Search strategy for EMBASE (OvidSP) (1988 to present)

#1 exp PROPOFOL/ or propofol*.mp.

#2 (propofol adj6 (induc* or relat*)).mp.

#3 #1 or #2

#4 PAIN/ or pain.ti,ab.

#5 #4 and #3

#6 LIDOCAINE/ or Lidocaine.mp.

#7 FENTANYL/ or Fentanyl.mp.

#8 Alfentanyl.mp. or Alfentanil/

#9 Meperidine.mp. or Pethidine/

#10 Ketamine.mp. or KETAMINE/

#11 Thiopental.mp. or THIOPENTAL/

#12 BUTORPHANOL/ or Butorphanol.mp.

#13 Flurbiprofen.mp. or FLURBIPROFEN/

#14 Ondansetron.mp. or ONDANSETRON/

#15 Granisetron.mp. or GRANISETRON/

#16 Ephedrine.mp. or EPHEDRINE/

#17 Clonidine.mp. or CLONIDINE/

#18 Metoclopramide.mp. or METOCLOPRAMIDE/

#19 Dexmedetomidine.mp. or DEXMEDETOMIDINE/

#20 Magnesium sulfate.mp. or Magnesium Sulfate/

#21 KETOROLAC/ or Ketorolac.mp.

#22 Diclofenac.mp. or DICLOFENAC/

#23 Metoprolol.mp. or METOPROLOL/

#24 Nitroglycerin.mp. or Glyceryl Trinitrate/

#25 Cold saline.mp.

#26 Acetaminophen.mp. or Paracetamol/

#27 Diphenhydramine.mp. or DIPHENHYDRAMINE/

#28 Nitrous Oxide.mp. or Nitrous Oxide/

#29 NEOSTIGMINE/ or Neostigmine.mp.

#30 TRAMADOL/ or Tramadol.mp.

#31 Nafamostat mesilate.mp.

#32 Prilocaine.mp. or PRILOCAINE/

#33 (temperature adj3 (cold or warm)).mp.

#34 (Dolasetron or Remifentanil).mp.

#35 or/6‐34

#36 #35 and #5

#37 Randomized Controlled Trial/

#38 RANDOMIZATION/

#39 Controlled Study/

#40 Multicenter Study/

#41 Phase 3 Clinical Trial/

#42 Phase 4 Clinical Trial/

#43 Double Blind Procedure/

#44 Single Blind Procedure/

#45 (RANDOM* or CROSS?OVER* or FACTORIAL* or PLACEBO* or VOLUNTEER*).ti,ab.

#46 ((SINGL* or DOUBL* or TREBL* or TRIPL*) adj3 (BLIND* or MASK*)).ti,ab.

#47 or/37‐46

#48 "human*".ec,hw,fs.

#49 #48 and #47

#50 #49 and #36

Appendix 6. Search strategy for LILACS (1992 to present)

("PROPOFOL/" or "propofol$") and ("PAIN" or "pain$")

Appendix 7. Study Selection, Quality Assessment and Data Extraction Form

First author Journal/Conference Proceedings etc Year

Study eligibility

RCT/Quasi/CCT (delete as appropriate) Yes/No/Unclear

Relevant participants Yes/No/Unclear

Relevant interventions Yes/No/Unclear

Relevant outcomes Yes/No*/Unclear

* Issue relates to selective reporting when authors may have taken measurements for particular outcomes, but not reported these within the paper(s). Review authors should contact trialists for information on possible non‐reported outcomes & reasons for exclusion from publication. Study should be listed in ‘Studies awaiting assessment’ until clarified. If no clarification is received after three attempts, study should then be excluded.

Do not proceed if any of the above answers are ‘No’. If study to be included in ‘Excluded studies’ section of the review, record below the information to be inserted into ‘Table of excluded studies’.

Freehand space for comments on study design and treatment:

References to trial

Code each paper Author(s) Journal/Conference Proceedings etc Year

Participants and trial characteristics

Participant characteristics

Age (mean, median, range, etc)

Sex of participants (numbers/%, etc)

Disease status/type, etc (if applicable)

Other

Trial characteristics

See Section 1, usually just completed by one review author

Methodological quality

State here method used to generate allocation and reasons for grading Grade (circle)

Adequate (random)

Inadequate (e.g. alternate)

Unclear

Concealment of allocation

Process used to prevent foreknowledge of group assignment in a RCT, which should be seen as distinct from blinding

State here method used to conceal allocation and reasons for grading Grade (circle)

Adequate

Inadequate

Unclear

Blinding

Person responsible for participants' care Yes/No

Participant Yes/No

Outcome assessor Yes/No

Other (please specify) Yes/No

Intention‐to‐treat

An intention‐to‐treat analysis is one in which all the participants in a trial are analysed according to the intervention to which they were allocated, whether they received it or not.

All participants entering trial Yes/No

Participants were excluded 15% or fewer/More than 15%

Analysed as intention to treat/per protocol/unspecified

Were withdrawals described? Yes? No? Not clear?

Discuss if appropriate

Data extraction

Outcomes relevant to your review

Copy and paste from ‘Types of outcome measures’ reported in paper (circle)

Pain score (VAS / NRS / VRS) Yes/No

Adverse effects Yes/No

Patients' satisfaction score Yes/No

Others Yes/No

For continuous data

Code of paper

Outcomes

Unit of measurement

Treatment group 1 N/Mean (SD)

Treatment group 2 N/Mean (SD)

Details if outcome only described in text

For dichotomous data