Abstract

Background

Automated telephone communication systems (ATCS) can deliver voice messages and collect health‐related information from patients using either their telephone's touch‐tone keypad or voice recognition software. ATCS can supplement or replace telephone contact between health professionals and patients. There are four different types of ATCS: unidirectional (one‐way, non‐interactive voice communication), interactive voice response (IVR) systems, ATCS with additional functions such as access to an expert to request advice (ATCS Plus) and multimodal ATCS, where the calls are delivered as part of a multicomponent intervention.

Objectives

To assess the effects of ATCS for preventing disease and managing long‐term conditions on behavioural change, clinical, process, cognitive, patient‐centred and adverse outcomes.

Search methods

We searched 10 electronic databases (the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; MEDLINE; Embase; PsycINFO; CINAHL; Global Health; WHOLIS; LILACS; Web of Science; and ASSIA); three grey literature sources (Dissertation Abstracts, Index to Theses, Australasian Digital Theses); and two trial registries (www.controlled‐trials.com; www.clinicaltrials.gov) for papers published between 1980 and June 2015.

Selection criteria

Randomised, cluster‐ and quasi‐randomised trials, interrupted time series and controlled before‐and‐after studies comparing ATCS interventions, with any control or another ATCS type were eligible for inclusion. Studies in all settings, for all consumers/carers, in any preventive healthcare or long term condition management role were eligible.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard Cochrane methods to select and extract data and to appraise eligible studies.

Main results

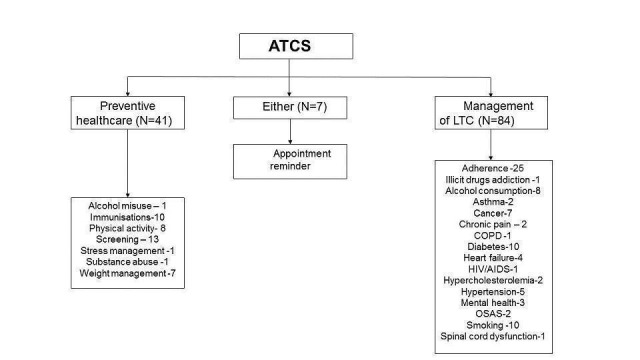

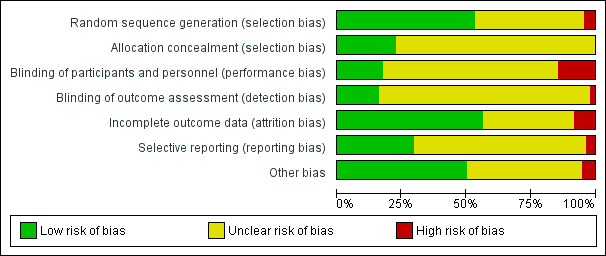

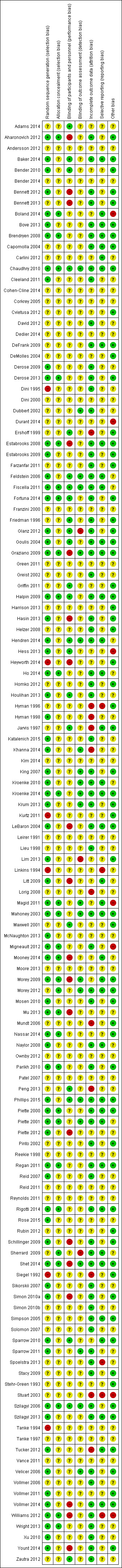

We included 132 trials (N = 4,669,689). Studies spanned across several clinical areas, assessing many comparisons based on evaluation of different ATCS types and variable comparison groups. Forty‐one studies evaluated ATCS for delivering preventive healthcare, 84 for managing long‐term conditions, and seven studies for appointment reminders. We downgraded our certainty in the evidence primarily because of the risk of bias for many outcomes. We judged the risk of bias arising from allocation processes to be low for just over half the studies and unclear for the remainder. We considered most studies to be at unclear risk of performance or detection bias due to blinding, while only 16% of studies were at low risk. We generally judged the risk of bias due to missing data and selective outcome reporting to be unclear.

For preventive healthcare, ATCS (ATCS Plus, IVR, unidirectional) probably increase immunisation uptake in children (risk ratio (RR) 1.25, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.18 to 1.32; 5 studies, N = 10,454; moderate certainty) and to a lesser extent in adolescents (RR 1.06, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.11; 2 studies, N = 5725; moderate certainty). The effects of ATCS in adults are unclear (RR 2.18, 95% CI 0.53 to 9.02; 2 studies, N = 1743; very low certainty).

For screening, multimodal ATCS increase uptake of screening for breast cancer (RR 2.17, 95% CI 1.55 to 3.04; 2 studies, N = 462; high certainty) and colorectal cancer (CRC) (RR 2.19, 95% CI 1.88 to 2.55; 3 studies, N = 1013; high certainty) versus usual care. It may also increase osteoporosis screening. ATCS Plus interventions probably slightly increase cervical cancer screening (moderate certainty), but effects on osteoporosis screening are uncertain. IVR systems probably increase CRC screening at 6 months (RR 1.36, 95% CI 1.25 to 1.48; 2 studies, N = 16,915; moderate certainty) but not at 9 to 12 months, with probably little or no effect of IVR (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.99, 1.11; 2 studies, 2599 participants; moderate certainty) or unidirectional ATCS on breast cancer screening.

Appointment reminders delivered through IVR or unidirectional ATCS may improve attendance rates compared with no calls (low certainty). For long‐term management, medication or laboratory test adherence provided the most general evidence across conditions (25 studies, data not combined). Multimodal ATCS versus usual care showed conflicting effects (positive and uncertain) on medication adherence. ATCS Plus probably slightly (versus control; moderate certainty) or probably (versus usual care; moderate certainty) improves medication adherence but may have little effect on adherence to tests (versus control). IVR probably slightly improves medication adherence versus control (moderate certainty). Compared with usual care, IVR probably improves test adherence and slightly increases medication adherence up to six months but has little or no effect at longer time points (moderate certainty). Unidirectional ATCS, compared with control, may have little effect or slightly improve medication adherence (low certainty). The evidence suggested little or no consistent effect of any ATCS type on clinical outcomes (blood pressure control, blood lipids, asthma control, therapeutic coverage) related to adherence, but only a small number of studies contributed clinical outcome data.

The above results focus on areas with the most general findings across conditions. In condition‐specific areas, the effects of ATCS varied, including by the type of ATCS intervention in use.

Multimodal ATCS probably decrease both cancer pain and chronic pain as well as depression (moderate certainty), but other ATCS types were less effective. Depending on the type of intervention, ATCS may have small effects on outcomes for physical activity, weight management, alcohol consumption, and diabetes mellitus. ATCS have little or no effect on outcomes related to heart failure, hypertension, mental health or smoking cessation, and there is insufficient evidence to determine their effects for preventing alcohol/substance misuse or managing illicit drug addiction, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, HIV/AIDS, hypercholesterolaemia, obstructive sleep apnoea, spinal cord dysfunction or psychological stress in carers.

Only four trials (3%) reported adverse events, and it was unclear whether these were related to the interventions.

Authors' conclusions

ATCS interventions can change patients' health behaviours, improve clinical outcomes and increase healthcare uptake with positive effects in several important areas including immunisation, screening, appointment attendance, and adherence to medications or tests. The decision to integrate ATCS interventions in routine healthcare delivery should reflect variations in the certainty of the evidence available and the size of effects across different conditions, together with the varied nature of ATCS interventions assessed. Future research should investigate both the content of ATCS interventions and the mode of delivery; users' experiences, particularly with regard to acceptability; and clarify which ATCS types are most effective and cost‐effective.

Plain language summary

Automated telephone communication systems for preventing disease and managing long‐term conditions

Background

Automated telephone communication systems (ATCS) send voice messages and collect health information from people using their telephone's touch‐tone keypad or voice recognition software. This could replace or supplement telephone contact between health professionals and patients. There are several types of ATCS: one‐way voice messages to patients (unidirectional), interactive voice response (IVR) systems, those with added functions like referral to advice (ATCS Plus), or those where ATCS are part of a complex intervention (multimodal).

Review question

This review assessed the effectiveness of ATCS for preventing disease and managing long‐term conditions.

Results

We found 132 trials with over 4 million participants across preventive healthcare areas and for the management of long‐term conditions.

Studies compared ATCS types in many ways.

Some studies reported findings across diseases. For prevention, ATCS probably increase immunisation uptake in children, and slightly in adolescents, but in adults effects are uncertain. Also for prevention, multimodal ATCS increase numbers of people screened for breast or colorectal cancers, and may increase osteoporosis screening. ATCS Plus probably slightly increases attendance for cervical cancer screening, with uncertain effects on osteoporosis screening. IVR probably increases the numbers screened for colorectal cancer up to six months, with little effect on breast cancer screening.

ATCS (unidirectional or IVR) may improve appointment attendance, key to both preventing and managing disease.

For long‐term management, multimodal ATCS had inconsistent effects on medication adherence. ATCS Plus probably improves medication adherence versus usual care. Compared with control, ATCS Plus and IVR probably slightly improve adherence, while unidirectional ATCS may have little, or slightly positive, effects. No intervention consistently improved clinical outcomes. IVR probably improves test adherence, but ATCS Plus may have little effect.

ATCS were also used in specific conditions. Effects varied by condition and ATCS type. Multimodal ATCS, but not other ATCS types, probably decrease cancer pain and chronic pain. Outcomes may improve to a small degree when ATCS are applied to physical activity, weight management, alcohol use and diabetes.However, there is little or no effect in heart failure, hypertension, mental health or quitting smoking. In several areas (alcohol/substance misuse, addiction, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, HIV/AIDS, high cholesterol, obstructive sleep apnoea, spinal cord dysfunction, carers' psychological stress), there is not enough evidence to tell what effects ATCS have.

Only four trials reported adverse events. Our certainty in the evidence varied (high to very low), and was often lowered because of study limitations, meaning that further research may change some findings.

Conclusion

ATCS may be promising for changing certain health behaviours, improving health outcomes and increasing healthcare uptake.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

The demand for information and communication technology applications in healthcare settings is increasing, driven by an interest in facilitating active participation of consumers in managing their own health as well as by the need to develop platforms that have greater reach and are also more cost‐effective than traditional approaches. Automated telephone communication systems (ATCS) are applications that have been used to deliver both preventive healthcare programmes as well as services to manage long‐term conditions.

The range of ATCS interventions included in this review encompasses the following.

Unidirectional ATCS. This is the non‐interactive form, which enables one‐way, non‐interactive voice communication.

Interactive ATCS. These are systems that enable two‐way real‐time communication. The most common form of this is the interactive voice response system or IVR, which might be used, for example, to provide automated tailored feedback based on the monitoring of an individual's progress.

ATCS Plus. These are also interactive ATCS systems, but they are more complex and include additional functions, such as access to an advisor to ask questions.

Additionally, this review includes several multimodal/complex ATCS interventions, defined as any type of ATCS (unidirectional, IVR or ATCS Plus) delivered as part of a complex, multimodal package, such as symptom monitoring by a health professional plus automated monitoring via IVR plus provision of medications.

Primary preventive healthcare

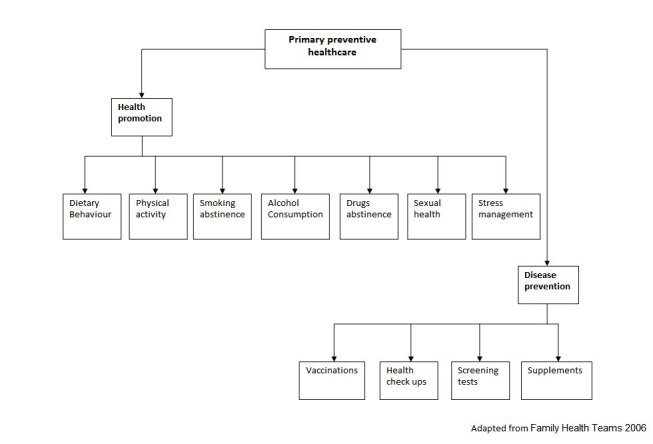

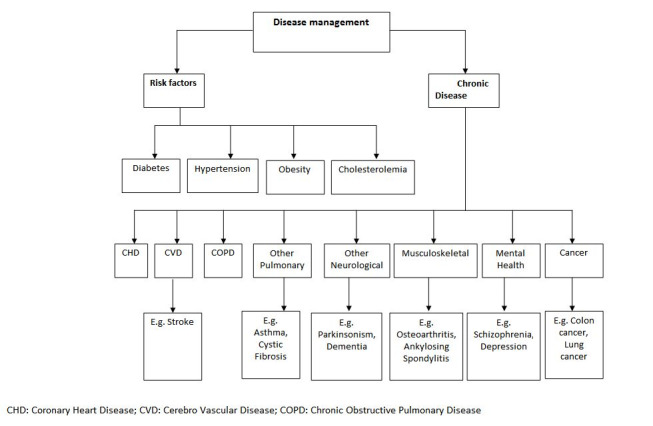

Primary preventive healthcare focuses on keeping people well, preventing disease and injury, and educating people about adopting healthier behaviours (Family Health Teams 2006). There are two types of primary prevention strategies: health promotion and disease prevention (Figure 1).

1.

Primary preventive healthcare

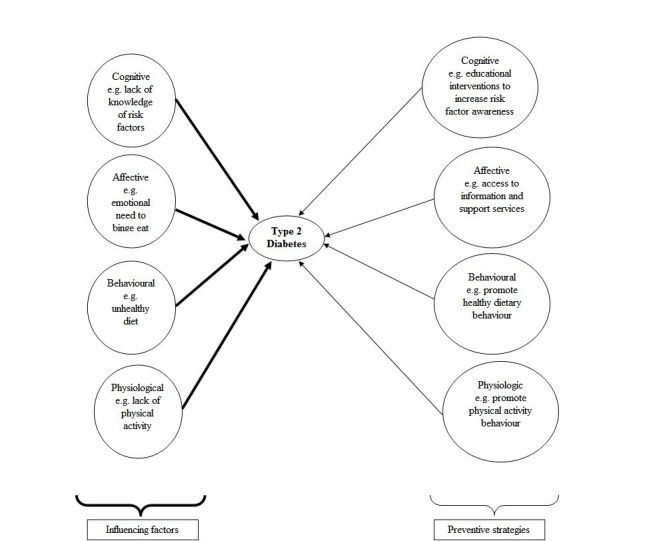

A major challenge for healthcare systems is to deliver preventive services that systematically target the factors that contribute to ill health (Gullotta 2014). In the prevention of diabetes mellitus, for example, a combination of cognitive, physiological, and behavioural factors (such as lack of knowledge around risk factors, lack of physical activity and unhealthy diet) may contribute to the development of the condition. An effective preventive strategy would therefore need to take an integrative approach and target each of the influencing factors (Figure 2).

2.

Influencing factors and preventive strategies in type 2 diabetes

One possible method of communicating preventive activities to the population is via information and communication technology (ICT) (Baranowski 2012; Haluza 2015).

Management of long‐term conditions

Long‐term conditions such as cardiovascular diseases, cancer, diabetes and chronic lung diseases are the leading causes of death globally (O'Dowd 2014). People with long‐term conditions face challenges such as dealing with complex symptoms, medication regimens, disability, and lifestyle adjustments (Carolan 2014; Demain 2015).

Effective chronic disease management programmes bring together relevant information systems with continuous follow‐up and targeted management, incorporating ICT to provide accessible and convenient educational information as well as self‐management tools for people with long‐term conditions (Galdas 2015).

ICT for primary prevention and management of long‐term conditions

Consumers increasingly use ICT for health in a myriad of ways, such as accessing medical records through web portals; communicating online with others, one‐on‐one or in a virtual community (Sawmynaden 2012); surfing the Internet to find information about health and health services; and transmitting health data or communicate messages using the web or the telephone (Pappas 2011).

There is some evidence that tools such as ATCS can successfully deliver health information to consumers, which facilitates health promotion (Cohen‐Cline 2014; Oake 2009b), enables active participation of consumers in managing their own care, and facilitates epidemiological and public health research by using collected patient data (Hendren 2014; Maheu 2001).

ICT can also support the delivery and administration of disease management programmes. There is evidence that ATCS can successfully deliver health information to patients for the management of long‐term conditions (Derose 2009; Derose 2013).

Description of the intervention

ATCS incorporate a specialised computer technology platform to deliver voice messages and collect information from consumers using either touch‐tone telephone keypads or voice recognition software (Piette 2012c). There are three types of ATCS.

Unidirectional ATCS enable one‐way, non‐interactive voice communication. This might include interventions such as automated reminder calls to take medication or perform other actions.

Interactive ATCS (e.g. IVR systems) enable two‐way real‐time communication, for example asking questions and receiving responses and individualised interventions (Reidel 2008; Rose 2015). Different studies have tested interactive ATCS for managing diabetes (Katalenich 2015; Khanna 2014), heart failure (Chaudhry 2010; Krum 2013), coronary heart disease (Reid 2007), and asthma (Bender 2010). They have also been used in health promotion initiatives, focusing on dietary behaviour (Delichatsios 2001; Wright 2014), physical activity (David 2012; Pinto 2002), and substance use (Aharonovich 2012).

ATCS Plus interventions are also interactive systems but include additional functions.

Advanced communicative functions including access to an advisor to request advice (e.g. 'ask the expert' function), scheduled contact with an advisor (e.g. telephone or face‐to‐face meetings), and peer‐to‐peer access (e.g. buddy systems).

Supplementary functions including automated, non‐voice communication (e.g. email or short messaging service (SMS)) (Webb 2010).

In this review, we also include several multimodal/complex ATCS interventions. These are more complex packages of care than ATCS Plus interventions and can include any type of ATCS (unidirectional, IVR or ATCS Plus) delivered as part of a complex, multimodal package, such as symptom monitoring by a health professional plus automated IVR monitoring plus provision of medications.

How the intervention might work

ATCS is a mode of communication that can replace or supplement some of the human‐to‐human telephone communication with a computer‐to‐human communication (Lieberman 2012; McCorkle 2011).

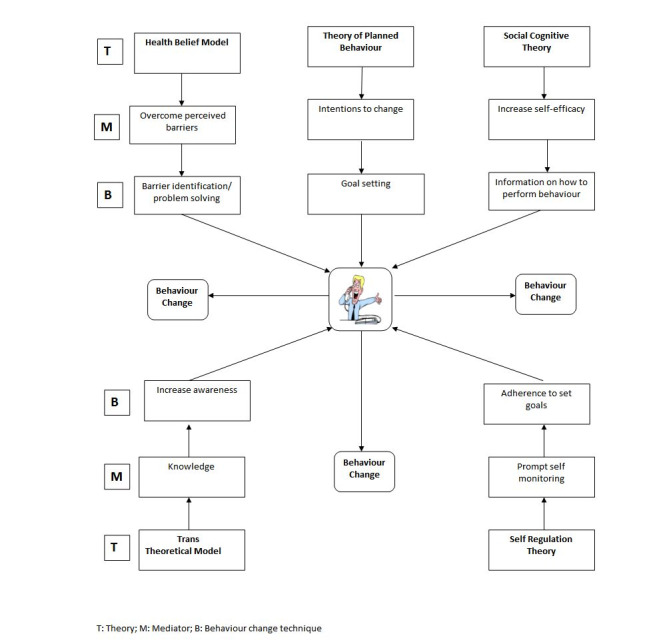

There is recognition that ATCS – like all other health interventions – should be underpinned by appropriate theoretical models (Krupinski 2006; Puskin 2010). These include the transtheoretical model (Prochaska 1984); theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen 1985); the health belief model (Rosenstock 1974); social cognitive theory (Bandura 2001); and self‐regulation theory (Leventhal 1984). Self‐management or preventive skills can be developed using any of these models (Barlow 2002).

There is evidence to suggest that behaviour change interventions underpinned by a theory can significantly enhance health behaviours (Fisher 2007; Gourlan 2015; Michie 2009; Webb 2010). Figure 3 shows a conceptual framework on how theories can influence health behaviour and illustrates how ATCS are used in preventive healthcare.

3.

Conceptual framework of ATCS in preventive healthcare

Social cognition models assume that any health outcome is the consequence of the complex interaction between social, environmental, economic, psychological and biomedical factors (Edelman 2000; Jekauc 2015; Kelly 2009). These models focus on key concepts, such as self‐efficacy and attitudes to influence behaviour, which in turn can lead to behaviour change (Hardeman 2005; Michie 2010; Vo 2015).

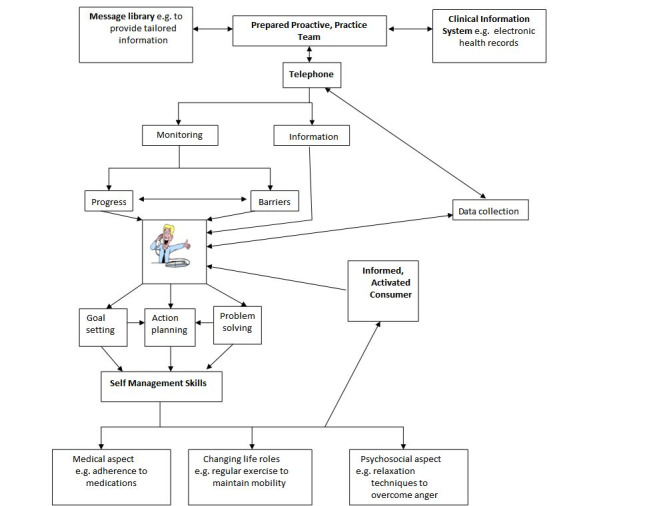

Healthcare interventions delivered through disease management programmes, such as those underpinned by the chronic care model, have produced improved consumer care and health outcomes (Gee 2015; Lee 2011; Piatt 2006; Schillinger 2009). According to the chronic care model, management of long‐term conditions requires an interaction between a prepared, proactive team of practitioners and an informed, engaged consumer (Gammon 2015; Wagner 2002). This can be achieved through the interplay between elements such as self‐management support, delivery system design, decision support, and clinical information systems (Webb 2006). Figure 4 describes a framework illustrating how ATCS might work in the management of long‐term conditions using the chronic care model, by educating, monitoring, and coaching patients.

4.

Conceptual framework of ATCS in the management of long‐term conditions

The importance of verbal communication is a complex psycholinguistic, cognitive‐emotional, and educational process that involves the transfer of information between a source (or sender) and a destination (or receiver); it largely depends on the topic/perspective of communication, perceived efficacy of communication, a person's mastery in encoding and understanding the semantic meaning decoded in verbal messages, and communicative intentions. However, other variables such as accent, voice tone, speech rate, and background noise also need to be taken into account when evaluating ATCS (Krauss 2001).

Advantages of automated telephone communication systems

ATCS as a data collection tools have a number of advantages over traditional face‐to‐face consultation (Rosen 2015). These include convenience, simplicity, anonymity, and low cost (Lee 2003; Piette 2012c). ATCS can provide access to health care 24 hours a day, seven days a week, along with immediate feedback to the consumer (Hall 2000; Schroder 2009). Both patients and healthcare professionals using ATCS have reported a high degree of user satisfaction, indicating that it is user‐friendly and convenient (Abu‐Hasaballah 2007).

ATCS technology can facilitate access to difficult‐to‐reach populations (e.g. people from a lower socioeconomic background) as ATCS require access only to a telephone (private or public) (Schroder 2009). Different authors have found ATCS to be acceptable to low‐literacy populations (Glasgow 2004; Piette 2007; Piette 2012c), and others have confirmed these findings in frail elderly patients (Mundt 2001). Unlike face‐to‐face interaction, which can elicit socially desirable responses, leading to under‐reporting of stigmatising behaviours and over‐reporting of socially desirable behaviours, ATCS have been found to elicit better self‐reporting of sensitive issues (e.g. substance misuse, alcohol use and sexual history) and reduce self‐reporting bias (Schroder 2009). They also have the potential to reduce healthcare delivery costs (Phillips 2015; Szilagyi 2013).

Disadvantages of automated telephone communication systems

Programming of ATCS involves investment in software and hardware, for example to enable multiple simultaneous calls and the development of a voice script appropriate for the target population and the topic of investigation (Piette 2007; Schroder 2009). ATCS may also present difficulties with the provision of immediate participant support. Should questions arise during the interview (Schroder 2009), ATCS cannot capture, interpret, or respond to the users' non‐verbal responses (Williams 2001). Individuals with physical disabilities (e.g. severe loss of hearing or speech) may have difficulty with ATCS (Mundt 2001). Others may simply have a strong preference for interactions with humans rather than with automated voice messages (Mahoney 2003). In addition, for individuals targeted by several ATCS‐based interventions, ATCS could lead to information overload and outright rejection of the interventions. Finally, protection of individually identifiable health information could be a challenge.

Why it is important to do this review

Existing reviews found evidence of effectiveness of ATCS in preventive healthcare and management of long‐term conditions (Krishna 2002; Lieberman 2012; Oake 2009b). However, none of those was conclusive, nor did they explore the theoretical basis or the mechanism of action of the intervention. The present review fills this gap by investigating the effects of interventions based on theoretical constructs and by exploring the behaviour change techniques implemented in the intervention (Abraham 2008; Michie 2011).

In addition, it is not clear which types of ATCS are most effective for prevention or management of long‐term conditions, in what setting, or for which conditions. This review aims to explore different interfaces of ATCS programme design and layout that may be used for diverse population groups (considering factors such as age, socioeconomic status, preferred language, and literacy) (Car 2004; Pappas 2011). Numerous randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the effectiveness of ATCS have recently been published.

A new systematic review is thus needed to critically assess the available evidence and to guide the implementation of ATCS in preventive healthcare and management of long‐term conditions.

Objectives

To assess the effects of ATCS for preventing disease and managing long‐term conditions on behavioural change, clinical, process, cognitive, patient‐centred and adverse outcomes.

Specific secondary objectives include:

determining which type of ATCS is most effective for preventive healthcare and management of long‐term conditions;

exploring which components of the interventional design contribute to positive consumer behavioural change;

exploring the behaviour change techniques and theoretical models underpinning the ATCS interventions.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included RCTs, cluster RCTs, quasi‐RCTs, interrupted time series (ITS) and controlled before‐and‐after (CBA) studies.

We included CBA and ITS studies because they are often used to draw conclusions about 'promising interventions' ready for trial when RCTs may be too expensive or simply impractical or where there are insufficient RCTs on a particular type of intervention (Centre for Reviews and Dissemination 2008; Higgins 2011; Jackson 2005). Interrupted time series designs can address cyclical trends (i.e. the outcome may be increasing or decreasing over time such as seasonal or other cyclical observations). To be considered for inclusion, these studies must have met the criteria specified by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Review Group (EPOC) (Ryan 2009). For CBA designs, the timing of data collection for the control and intervention groups had to have been the same, there must have been at least two intervention sites and two control sites, and both groups would have been comparable on key characteristics related to demographics and intervention context. For ITS designs, the studies had to use a clearly defined point in time when the intervention occurred and at least three data points before and three after the intervention.

Types of participants

We included consumers, including carers, who received ATCS for prevention or management of long‐term conditions, regardless of age, sex, education, marital status, employment status, or income.

For management of long‐term conditions, we included consumers who had one or more concurrent long‐term conditions (i.e. multimorbidity).

We included consumers in all settings.

Types of interventions

The ATCS interventions included in this review included the following.

Unidirectional ATCS: non‐interactive ATCS enabling one‐way voice communication.

Interactive ATCS: systems that enable two‐way, real‐time communication, such as interactive voice response systems or IVR.

ATCS Plus: interactive ATCS systems including additional functions.

The review also included several multimodal/complex ATCS interventions, defined as any type of ATCS (unidirectional, IVR or ATCS Plus) delivered as part of a complex, multimodal package.

We included studies that evaluated either unidirectional ATCS or interactive ATCS. We also included studies that compared ATCS interventions (e.g. unidirectional ATCS versus interactive ATCS and/or ATCS Plus) to compare the effects of different intervention designs on preventive healthcare or management of long‐term conditions.

Interactive ATCS had an automated function such as automated tailored feedback based on individual progress monitoring (e.g. comparison to norms or goals, reinforcing messages, coping messages, and automated follow‐up messages). Although our protocol (Cash‐Gibson 2012) indicated that we would include ATCS Plus interventions only if the study explicitly reported that the effects of the intervention could be attributed to the ATCS component, in the review we included all types of ATCS Plus interventions as, in a complex intervention such as this, it would be impossible to attribute the intervention effect to one of the intervention components. We also included studies that delivered any type of ATCS (unidirectional, IVR, or ATCS Plus) as part of a complex, multimodal (package) intervention.

The interventions were delivered for one or more types of prevention or one or more types of management for long‐term conditions, as illustrated in Figure 1 and Figure 5, respectively.

5.

Management of long‐term conditions

We excluded studies in which interventions:

targeted health professionals or teachers for educational purposes;

were exclusively for the purpose of electronic history‐taking or data collection or risk assessment with no health promotion or interactive elements;

involved only a non‐ATCS component such as face‐to‐face communication or written communication;

were web‐based interventions that were accessed via a mobile phone.

Comparisons were made against various controls or standard or enhanced forms of usual care (i.e. no ATCS intervention). We also included comparisons of one type of ATCS against another, or the same type of ATCS that was delivered via different delivery modes (e.g. landline telephone versus mobile phone).

As part of this review, we piloted and applied the intervention Complexity Assessment Tool for Systematic Reviews version 1 (iCAT_SR) for assessing complex, multimodal interventions and reported results narratively/qualitatively (Lewin 2015).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Primary outcomes consisted of health behaviour and clinical outcomes (defined below). For each study, we included all relevant primary outcomes, as these are likely to be most meaningful to clinicians, consumers, the general public, administrators and policymakers (Chandler 2013). Given the wide spread of the included studies and the fact that this review represents the first attempt to systematically assess all relevant evidence on broadly defined ATCS interventions, we felt that it was important to capture and report as much relevant information on outcomes and effects of interventions as possible, in order to assist with comprehensively mapping where the evidence lies and how it has been assessed. In future updates to this review, we may consider modifying this approach to focus on a smaller number and range of outcomes if this is likely to improve the clarity and meaningfulness of the collected data.

We reported the following outcomes in 'Summaries of findings' tables.

1. Health behaviour outcomes (category)

Changes in health‐enhancing behaviour (e.g. physical activity, adherence to medications/uptake of recommended laboratory or other testing)

Risk‐taking behaviour (e.g. tobacco consumption)

This outcome was either self‐reported or collected using a validated questionnaire that was either self‐administered or completed in an interview. In studies that measured the same outcome using both a self‐reported measure and an objective measure, we used the objective measure. For example, if a study on physical activity measured Metabolic Equivalent of Task (MET) scores using a self‐reported, seven‐day physical activity recall as well as a pedometer, we used the score obtained from the (objective) pedometer.

2. Clinical outcomes (category)

Physiological measures (e.g. blood pressure)

Blood biochemistry (e.g. glucose levels)

Secondary outcomes

For each study, we selected all relevant secondary outcomes as these were also meaningful for the various stakeholders.

1. Process outcomes (category)

Change in acceptability of service (e.g. consumer accessibility and usability of the interventions to apply information and support supplied through ATCS)

Satisfaction (e.g. patient and carer satisfaction with the intervention)

Cost‐effectiveness

2. Cognitive outcomes (category)

Changes in knowledge (i.e. accurate risk knowledge and perception)

Attitude and intention to change

Self‐efficacy (i.e. a person's belief in their capacity to carry out a specific action)

3. Patient‐centred outcomes (category)

Quality of life

4. Adverse outcomes

Unintended adverse events attributable to the intervention

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases.

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2015; Issue 5) in the Cochrane Library (searched 12 May 2015);

MEDLINE OvidSP (1980 to 12 May 2015);

Embase OvidSP (1980 to 12 May 2015);

PsycINFO OvidSP (1980 to 12 May 2015);

CINAHL EBSCOhost (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; 1980 to 12 June 2015);

Web of Science (1980 to 19 May 2015);

GlobalHealth EBSCOhost (1980 to 16 June 2015);

WHOLIS (1980 to 17 June 2015);

LILACS (1982 to 17 June 2015); and

ASSIA ProQuest (Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts; 1987 to 20 May 2015).

We detail the search strategies for each database in respective appendices: CENTRAL (Appendix 1), MEDLINE (Appendix 2), Embase (Appendix 3), PsycINFO (Appendix 4), CINAHL (Appendix 5), Web of Science (Appendix 6), Global Health (Appendix 7), and WHOLIS (Appendix 8). We also present the list of keywords used in trial registers (Appendix 9) and grey literature (Appendix 10).

We searched most databases from 1980 onwards because we expected that any prior evidence would have been incorporated into subsequent research, and because technology has advanced dramatically over the last thirty years, so integration of older research should be interpreted only in light of new findings. We tailored search strategies to each database and reported them in the review. There were no language restrictions.

Searching other resources

We searched grey literature (Dissertation Abstracts, Index to Theses, Australasian Digital Theses). We contacted experts in the field and authors of included studies for advice as to other relevant studies. We searched reference lists of relevant studies, including all included studies and previously published reviews. We also searched online trial registers (e.g. Current Controlled Trials, www.controlled‐trials.com; www.clinicaltrials.gov) for ongoing and recently completed studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

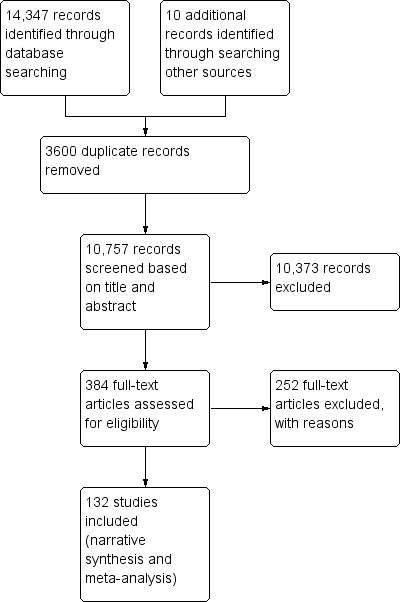

We merged search results across databases using (EndNote 2015) reference management software and removed duplicate records. Following de‐duplication, two authors (PP, NM) independently examined titles and abstracts of records retrieved from the search. We retrieved the full text of the potentially relevant studies and assessed their eligibility according to the inclusion criteria. We linked multiple reports of the same study in order to determine whether the study was eligible for inclusion. Two authors independently performed both the initial screening and the full text screening. Authors corresponded with each other to make final decisions on study inclusion and resolved disagreement about study eligibility through discussion with a third review author (JC). We describe excluded studies, with reasons for exclusion, in Characteristics of excluded studies. We used an adapted PRISMA flow chart to describe the study selection process Figure 6 (Higgins 2011).

6.

Study flow diagram

Data extraction and management

Two authors (PP, NM) independently extracted relevant characteristics related to participants, intervention, comparators, outcome measures, and results (effectiveness of the interventions) from all the included studies using a standard data collection form; any disagreements were resolved by discussion. We sought relevant missing information on the trial, particularly information required to judge the risk of bias, from the original author(s) of the article. One author (PP) transferred all the data from the extraction form into the Review Manager (RevMan) software while another author (NM) confirmed the accuracy of the transferred data (RevMan 2014).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We included all studies meeting the inclusion criteria regardless of the outcome of the assessment of risk of bias. We assessed and reported on the methodological risk of bias of included studies in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and Cochrane Consumers and Communication guidelines (Higgins 2011; Ryan 2011), which recommend explicitly reporting the following individual elements for RCTs: random sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding (participants, personnel); blinding (outcome assessment); completeness of outcome data (attrition bias), selective outcome reporting (relevant outcomes reported); other sources of bias (baseline imbalances). For cluster RCTs, we also assessed and reported the risk of bias associated with an additional domain: selective recruitment of cluster participants. We referred to Cochrane Consumers and Communication guidelines to narratively describe the results of risk of bias for each domain for all included studies (Ryan 2011). We reported our assessment of risk of bias for each domain and included study, with a descriptive summary/synthesis of our judgments. In all cases, two authors (PP, NM) independently assessed the risk of bias of included studies, resolving any disagreements by discussion and consensus. We also contacted several study authors for additional information about the included study or for clarification of the study's methods. We incorporated the results of the risk of bias assessment into GRADE assessments and the review itself through standard tables together with systematic and descriptive summary, leading to an overall assessment of the risk of bias of included studies and a judgment about the internal validity of the review's results.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous data, we reported risk ratios (RR), odds ratios (OR), or hazard ratios (HR), as well as their 95% confidence intervals (CI) and P values. For continuous data we reported mean values and standard deviations (SD) of the outcomes in each intervention group along with the number of participants and P values (Table 13).

1. Results.

| Dichotomous outcomes | ||||||||||

| Primary outcome | Study ID | Timing of outcome assessment (months) | Intervention group | Comparator group | Between group difference | Notes | ||||

| Observed (n) | Total (N) | Observed (n) | Total (N) | P value | Effect estimate (OR/RR/HR) | 95% CI | ||||

| IMMUNISATIONS | ||||||||||

| Immunisation uptake | Dini 2000 | 24 | 107 | 189 | 87 | 186 | — | 1.21 | 0.99 to 1.47 | — |

| Franzini 2000 | * | 270 | 314 | 273 | 429 | — | — | — | — | |

| Hess 2013 | 3 | 146 | 5599 | 46 | 6383 | < 0.001 | 3.69 | 2.64 to 5.15 | Cluster RCT unadjusted for clustering. Approximate sample size calculations gave the following adjusted values: intervention 20/791; control 6/902; see Appendix 14 for calculations | |

| Lieu 1998 | 4 | 89 | 167 | 70 | 162 | 0.11 | — | 29.0 to 43.8 | CIs for % values and for IVR alone; P value from Chi2 | |

| Linkins 1994 | 1 | 1684 | 4636 | 955 | 3366 | < 0.01 | 1.28 | 1.20 to 1.37 | — | |

| LeBaron 2004 | 13 | 305 | 763 | 259 | 763 | < 0.05 | — | — | — | |

| Nassar 2014 | 2 | 3 | 26 | 3 | 24 | — | — | — | — | |

| Stehr‐Green 1993 | 1 | 46 | 112 | 41 | 110 | — | 1.07 | 0.78 to 1.46 | — | |

| Szilagyi 2006 | 18 | 928 | 1496 | 873 | 1510 | 0.02 | — | — | — | |

| Szilagyi 2013 | 12 | 748 | 1423 | 651 | 1296 | < 0.05 | 1.3 | 1.0 to 1.7 | — | |

| SCREENING | ||||||||||

| Screening rate | Baker 2014 | 6 | 191 | 225 | 90 | 225 | < 0.001 | — | — | — |

| Cohen‐Cline 2014 | 6 | 801 | 8005 | 234 | 3005 | 0.0012 | 1.32 | 1.14 to 1.52 | ||

| Corkrey 2005 | 3 | — | 45,303 | — | 30,229 | — | — | 1.28 to 1.42a 0.11 to 0.17b |

aWomen aged 50‐69 years bWomen aged 20‐49 years |

|

| DeFrank 2009 | 10 to 14 | 960 | 1355 | 574 | 847 | 0.014 | 1.32 | 1.06 to 1.64 | — | |

| Fiscella 2011 | 12 | 55a 47b |

134a 163b |

23a 16b |

137a 160b |

— | 3.44a 3.70b |

1.91 to 6.19a 1.93 to 7.09b |

aBreast cancer screening; bColorectal cancer screening |

|

| Fortuna 2014 | 12 | 36a 24b |

158a 157b |

28a 19b |

157a 156b |

> 0.05 | 1.4a 1.3b |

0.8 to 2.4a 0.7 to 2.5b |

aBreast cancer screening; bColorectal cancer screening (both crude estimates) |

|

| Hendren 2014 | 12 | 30a 43b |

101a 114b |

15a 21b |

90a 126b |

0.034a 0.0002b |

1.96a 3.22b |

0.87 to 4.39a 1.65 to 6.30b |

aBreast cancer screening; bColorectal cancer screening |

|

| Heyworth 2014 | 12 | 385 | 1565 | 290 | 1558 | < 0.001 | — | — | ||

| Mosen 2010 | 6 | 662 | 2943 | 474 | 2962 | < 0.001 | 1.31 | 1.10 to 1.56 | — | |

| Phillips 2015 | 9 | 19a 33b |

90a 198b |

17a 27b |

88a 199b |

— | — | — |

aBreast cancer screening; bColorectal cancer screening |

|

| Simon 2010a | 12 | 3192 | 10,432 | 3194 | 10,506 | 0.76 | 1.01 | 0.94 to 1.07 | In the adjusted model | |

| Solomon 2007 | 10 | 144 | 997 | 97 | 976 | 0.006 | 1.52 | 1.13 to 2.05 | In the adjusted model | |

| APPOINTMENT REMINDERS | ||||||||||

| Reducing non‐attendance rates | Dini 1995 | 1 | 144 | 277 | 78 | 240 | < 0.05 | 1.60 | 1.29 to 1.98 | — |

| Griffin 2011 | 1.5 | 333a 169b |

794a 411b |

324a 164b |

790a 409b |

> 0.05 | — | −6 to 5a −8 to 7b |

aColonoscopy bFlexible sigmoidoscopy |

|

| Maxwell 2001 | 2 | 347 | 700 | 322 | 670 | > 0.05 | — | — | — | |

| Parikh 2010 | 4 | 2662 | 3219 | 2576 | 3350 | < 0.001 | 1.52 | 1.34 to 1.71 | — | |

| Reekie 1998 | 1.5 | 473 | 500 | 453 | 500 | < 0.001 | 3.41 | 1.87 to 6.20 | — | |

| Tanke 1994 | 6 | 257 | 407 | 235 | 456 | < 0.01 | 1.50 | — | — | |

| Tanke 1997 | 3 days | 652 | 701 | 617 | 701 | < 0.05 | 1.71 | — | — | |

| ADHERENCE | ||||||||||

| Adherence to medications/laboratory tests | Bender 2010 | 2.5 | 16 | 25 | 12 | 25 | 0.003 | — | — | — |

| Derose 2009 | 3 | 453 | 2199 | 298 | 1550 | 0.31 | 1.09 | 0.92 to 1.28 | At 8 weeks differences were not significant (P = 0.23) | |

| Feldstein 2006 | 25 days | 177 | 267 | 53 | 237 | < 0.001 | 4.1 | 3.0 to 5.6 | — | |

| Friedman 1996 | 6 | 24 | 133 | 16 | 134 | 0.03 | — | — | — | |

| Glanz 2012 | 12 | 47 | 157 | 42 | 155 | > 0.05 | — | — | — | |

| Green 2011 | 2 weeks | 1180 | 4124 | 958 | 4182 | < 0.001 | — | — | — | |

| Ho 2014 | 12 | 109 | 122 | 88 | 119 | 0.003 | — | — | — | |

| Lim 2013 | 5 | 29 | 38 | 34 | 42 | 0.233 | — | — | After the mid‐study visit | |

| Migneault 2012 | 12 | — | 169 | — | 168 | 0.19 | — | — | — | |

| Mu 2013 | 1 | 1096975 | 4153634 | 18395 | 84187 | < 0.001 | — | — | — | |

| Patel 2007 | 3 to 6 | 3362 | 6833 | 1865 | 4172 | — | — | — | ||

| Reynolds 2011 | 2 weeks | 4318 | 15,356 | 3309 | 15,254 | < 0.001 | — | — | — | |

| Sherrard 2009 | 6 | 70 | 137 | 55 | 143 | 0.041 | 0.60 | 0.37 to 0.96 | Primary composite outcome of adherence and adverse effects (emergency room visit and hospitalisation) | |

| Simon 2010b | 12 | — | 600 | — | 600 | — | 0.93 | 0.71 to 1.22 | — | |

| Stacy 2009 | 6 | 178 | 253 | 148 | 244 | < 0.05 | 1.54 | 1.13 to 2.10 | — | |

| Vollmer 2011 | 18 | — | 3171 | — | 3260 | 0.002 | — | 0.01 to 0.03 | P value and CIs for Δ change | |

| Vollmer 2014 | 12 | — | 7247 | — | 7255 | 0.022 | — | 0.011 to 0.034 | P value and CIs for Δ change | |

| HEART FAILURE | ||||||||||

| Heart failure hospitalisation | Capomolla 2004 | 10 ± 6 (median 11) | 17 | 67 | 58 | 66 | < 0.05 | — | — | — |

| Kurtz 2011 | 12 | 4 | 32 | 17 | 50 | < 0.05 | — | — | This was a cluster outcome: "cardiovascular deaths and hospitalisations‐ which ever event occurred first" | |

| All‐cause mortality | Capomolla 2004 | 10 ± 6 (median 11 ) | 5 | 67 | 7 | 66 | > 0.05 | — | — | — |

| Chaudhry 2010 | 6 | 92 | 826 | 94 | 827 | 0.86 | 0.97 | 0.73 to 1.30 | Death or readmission | |

| Krum 2013 | 12 | 17 | 170 | 16 | 209 | 0.439 | 1.36 | 0.63 to 2.93 | — | |

| Cardiac mortality | Capomolla 2004 | 10 ± 6 (median 11) | 2 | 67 | 6 | 66 | > 0.05 | — | — | — |

| Kurtz 2011 | 12 | 3 | 32 | 5 | 50 | > 0.05 | — | — | Cluster outcome: "cardiovascular deaths and hospitalisations‐ which ever event occurred first" | |

| SMOKING | ||||||||||

| Smoking abstinence | Brendryen 2008 | 12 | 74 | 197 | 48 | 199 | 0.02 | 1.91 | 1.12 to 3.26 | — |

| Ershoff 1999 | 9 | 20 | 120 | 25 | 111 | — | — | — | — | |

| McNaughton 2013 | 12 | 12 | 23 | 14 | 21 | 0.33 | — | — | — | |

| Regan 2011 | 3 | 105 | 361 | 95 | 364 | 1.13 | 0.90 to 1.41 | — | ||

| Reid 2007 | 12 | 23 | 50 | 17 | 49 | 0.25 | 1.60 | 0.71 to 3.60 | — | |

| Rigotti 2014 | 6 | 51 | 198 | 30 | 199 | 0.009 | 1.71 | 1.14 to 2.56 | — | |

| Velicer 2006 | 30 | 75 | 500 | 65 | 523 | — | — | — | For 6 month prolonged abstinence | |

| Continous outcomes | ||||||||||

| Primary outcome | study ID | Timing of outcome assessment (months) | Intervention group | Comparator group | Between‐group difference | Notes | ||||

| Mean |

Standard deviation of change (SD) or SD |

Mean | Standard deviation of change (SD) or SD | Change | Confidence intervals | P values | ||||

| ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION | ||||||||||

| Drinks per drinking day | Hasin 2013 | 2 | 3.5 | 1.8 | 4.7 | 3.2 | 1.38 | 1.12 to 1.70 | < 0.01 | CIs are for the effect size |

| Rose 2015 | 2 | 4 | 0.4 | 4.3 | 0.4 | — | — | 0.45 | — | |

| CANCER | ||||||||||

| Symptom severity | Cleeland 2011 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Effect size: intervention = 0.75; control = 0.68 |

| Mooney 2014 | 1.5 | 5.76 to 7.36 (range) | — | 5.55 to 7.44 (range) | — | 0.06 | — | 0.58 | — | |

| Sikorskii 2007 | 2.5 | 20.73 | — | 20.80 | — | — | — | > 0.05 | Effect size: intervention = 0.59; control = 0.56 | |

| Spoelstra 2013 | 2.5 | 11.6 | — | 11.0 | — | — | — | 0.02 | — | |

| DIABETES | ||||||||||

| Glycated haemoglobin (%) | Graziano 2009 | 3 | 7.87 | 1.09 | 7.82 | 1.14 | — | — | 0.89 | — |

| Katalenich 2015 | 6 | 8.10 | 7.90 | — | — | — | > 0.05 | Median values | ||

| Khanna 2014 | 3 | 9.1 | 1.9 | 8.6 | 1.3 | — | — | 0.41 | — | |

| Kim 2014 | 12 | 9.0 | 2 | 9.9 | 2.2 | — | — | 0.02 | — | |

| Lorig 2008 | 6 | 7.0 | 1.4 | 7.3 | 1.5 | — | — | 0.04 | — | |

| Piette 2001 | 12 | 8.1 | 1.15 | 8.2 | 1.18 | — | — | 0.3 | — | |

| Schillinger 2009 | 12 | 8.7 | 1.9 | 9.0 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 0.5 to 0.4 | 0.8 | — | |

| Williams 2012 | 6 | 7.9 | 1.2 | 8.7 | 1.8 | 0.91 | 0.86 to 0.93 | 0.002 | — | |

| Serum blood glucose (mg/dL) | Piette 2001 | 12 | 180 | 9 | 172 | 10 | — | — | 0.6 | — |

| Homko 2012 | 26 | 107.4 | 12.9 | 109.7 | 16.5 | — | — | 0.44 | — | |

| Self‐monitoring of blood glucose | Graziano 2009 | 3 | 1.9 | 1.07 | 1.3 | 0.75 | — | — | < 0.001 | — |

| Lorig 2008 | 6 | 0.05 | 0.387 | 0.08 | 0.365 | — | — | 0.457 | — | |

| Piette 2001 | 12 | 4.6 | 0.1 | 4.4 | 0.1 | — | — | 0.05 | — | |

| Schillinger 2009 | 12 | 4.3 | 2.6 | 3.3 | 2.9 | 0.8 | 0.1 to 1.5 | 0.03 | — | |

| Self‐monitoring of diabetic foot | Piette 2001 | 12 | 4.6 | 0.1 | 4.4 | 0.1 | — | — | — | — |

| Schillinger 2009 | 12 | 5.1 | 1.4 | 4.6 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 0.2 to1.0 | 0.002 | — | |

| HYPERTENSION | ||||||||||

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) | Dedier 2014 | 3 | 136.4 | 83.5 | 138.9 | 81.5 | — | — | > 0.05 | — |

| Goulis 2004 | 6 | 123.8 | 14.2 | 128.6 | 19.4 | — | — | > 0.05 | — | |

| Friedman 1996 | 6 | 158 | * | 160.2 | * | −1.8 | — | 0.20 | — | |

| Harrison 2013 | 1 | 141.2 | 15.1 | 143.1 | 14.6 | — | < 0.001 | — | ||

| Magid 2011 | 6 | 137.4 | 19.4 | 136.7 | 17.0 | −0.7 | — | 0.006 | — | |

| Piette 2012 | 6 weeks | 142.5 | 2.3 | 143.6 | 2.4 | −4.2 | −9.1 to 0.7 | 0.09 | — | |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) | Friedman 1996 | 6 | 80.9 | — | 83.2 | — | — | — | 0.02 | — |

| Goulis 2004 | 6 | 74.6 | 8.5 | 79.5 | 14.0 | — | — | > 0.05 | — | |

| Harrison 2013 | 1 | 80.3 | 12.6 | 81.3 | 12.5 | — | — | < 0.001 | — | |

| Magid 2011 | 6 | 82.9 | 12.9 | 81.1 | 11.7 | −2.3 | −4.9 to −0.2 | 0.07 | — | |

| OBSTRUCTIVE SLEEP APNOEA SYNDROME (OSAS) | ||||||||||

| Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) use | DeMolles 2004 | 2 | 4.4 | — | 2.9 | — | — | — | 0.076 | — |

| Sparrow 2010 | 12 | — | — | — | — | — | 1.18 to 2.48 | 0.004 | — | |

| WEIGHT MANAGEMENT | ||||||||||

| BMI in adults | Bennett 2012 | 18 | 36.54 | 2.01 | 36.84 | 1.90 | −0.35 | −0.75 to 0.06 | — | — |

| Bennett 2013 | 18 | 29.8 | 1.90 | 30.3 | 1.93 | −0.6 | −1.2 to −0.1 | 0.03 | — | |

| Goulis 2004 | 6 | 33.7 | 5.2 | 37.2 | 8.7 | — | — | 0.06 | — | |

| BMI‐z scores in children | Estabrooks 2009 | 12 | 1.95 | 0.04 | 1.98 | 0.03 | — | — | > 0.05 | — |

| Wright 2013 | 3 | 1.9 | 0.28 | 1.9 | 0.3 | −0.03 | — | 0.48 | — | |

Analyses limited to primary outcomes from at least 2 studies from the same category.

Unit of analysis issues

When a study had more than one active treatment arm, we labelled the study arms as 'a', 'b' and so on. If more than one intervention arm was relevant for a single comparison, we compared the relevant ATCS arm with the least active control arm to avoid double‐counting of data. We listed the arms that were not used for comparison in the 'Notes' section of the Characteristics of included studies tables.

In cluster RCTs, we checked for unit of analysis errors. If we identified any and sufficient information was available, we re‐analysed the data using the appropriate unit of analysis, taking account of the intracluster correlation coefficients (ICC). We planned to impute estimates of the ICC using external sources. Where it was not possible to obtain sufficient information to reanalyse the data, we annotated the study 'unit of analysis error' and used this when interpreting the results of that study (where failure to adjust for clustering may lead to overly precise effect estimates) (Higgins 2011; Ukoumunne 1999).

Dealing with missing data

We conducted an intention‐to‐treat analysis, including all participants who were randomised to either the ATCS group or comparator, regardless of losses to follow‐up and withdrawals (Higgins 2011). Wherever possible, we attempted to obtain missing data (e.g. number of participants in each group, outcomes and summary statistics) from the original author(s). For dichotomous outcomes, data imputed case analysis can be used to fill in missing values. This strategy imputes missing data according to reasons for 'missingness' and essentially averages over several of the specific imputation strategies (Higgins 2008). When SDs of continuous outcome data were missing, we calculated them from other statistics, such as 95% CIs, standard errors, or P values. If these were unavailable, we planned to contact the authors or impute the standard deviations from other similar studies (Higgins 2008).

Assessment of heterogeneity

Where we considered studies to be sufficiently similar (based on consideration of populations, interventions, comparators, outcome measures and primary endpoints) to allow pooling of data using meta‐analysis, we assessed the degree of heterogeneity by visual inspection of forest plots and by examining the Chi2 test for heterogeneity. We quantified heterogeneity using the I2 statistic. We considered an I2 value of 50% or more to represent substantial levels of heterogeneity, but we also interpreted this value in light of the size and direction of effects and the strength of the evidence for heterogeneity, based on the P value from the Chi2 test (Higgins 2011). Where substantial heterogeneity was present in pooled effect estimates, we had planned to explore the reasons for variability by conducting subgroup analyses. However, there was not a sufficient number of studies in pooled analyses to enable performance of subgroup analysis. Where we detected substantial clinical, methodological, or statistical heterogeneity across included studies, we did not report pooled results from meta‐analysis but instead used a narrative approach to data synthesis. In this event we attempted to explore possible clinical or methodological reasons for this lack of homogeneity by grouping studies that were similar in terms of populations, interventions, comparators, outcome measures and primary endpoints to explore differences in intervention effects.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed reporting bias qualitatively based on the characteristics of the included studies (e.g. if only small studies that indicate positive findings were identified for inclusion). Where quantitative meta‐analysis included at least 10 studies, we had planned to construct a funnel plot to investigate small study effects, as this may indicate the presence of publication bias. We also planned to formally test for funnel plot asymmetry, with the choice of test made based on advice in Higgins 2011, and bearing in mind that there may be several reasons for funnel plot asymmetry when interpreting the results (Egger 1997). However, there were not enough studies in any of the pooled analyses to allow formal assessment of reporting biases.

Data synthesis

Our decisions on whether to perform meta‐analysis were based on an assessment of whether participants, interventions, comparisons, and outcomes were sufficiently similar to ensure a clinically meaningful result. For studies that were included in meta‐analysis, we used a random‐effects model. For studies that assessed the same continuous outcome measures, we estimated mean differences (for studies using the same scale) and standardised mean differences (for differences in scale) between groups, along with 95% CIs. We displayed the results of the meta‐analysis in a forest plot that provided effect estimates and 95% CIs for each individual study as well as a pooled effect estimate and 95% CI. We performed meta‐analysis using RevMan 2014. We adhered to the statistical guidelines described in Higgins 2011.

We used a systematic approach to the description of results from pooled data and to narratively describe results. This approach was based on the following process.

Two authors (PP, RR) assessed the size of the effect and jointly rated it as an important, less important, or not important.

Two authors (PP, RR) assessed the quality of the evidence using GRADE criteria (Schünemann 2011). According to these guidelines, we assessed all primary and secondary outcomes reported in the review and assigned a rating of high, moderate, low, or very low certainty.

We reported results and then adopted the standardised wording developed for writing Plain Language Summaries in Cochrane reviews (Glenton 2010); see Appendix 12. We used this wording to synthesise all of the results of the review, irrespective of whether we meta‐analysed or narratively reported the data.

For all the included studies we used the following steps to describe the studies as described by Rodgers 2009.

Developed a preliminary synthesis by grouping the included studies by the type of prevention or long‐term condition and intervention.

Described the inclusion criteria (especially participants, interventions, comparators, and outcome elements) along with the reported findings for each of the included studies.

Included an additional table to describe the intervention components including: the type of ATCS; content delivery; intervention content; behaviour change theories; behaviour change techniques (Michie 2011); instructions on how to use the system (yes/no); call initiation (participants/interventionist/either); telephone keypad for response (yes/no); toll free number (yes/no); duration of intervention; duration of call; frequency, intensity; speakers features; and security arrangement.

Used the summary of quality of the evidence, assessed using the GRADE tool, to judge the robustness of the evidence; and adapted standardised wording based on the size of effects and the strength (quality) of the evidence to consistently describe results.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We considered performing subgroup analyses depending on the types of preventive intervention (Figure 1), long‐term condition being managed (Figure 5), and other relevant factors that may have influenced the results.

Type of ATCS (unidirectional, IVR or ATCS Plus, multimodal).

Type of preventive intervention;

Type of long‐term condition.

Language (for studies in languages other than English).

Country's income level (for studies undertaken in 'high‐income countries', 'middle‐income countries', or 'low‐income countries' as defined by the World Bank's income level data (World Bank 2012)).

Source of funding (industry versus other).

Theoretical models (where applicable, we separated included studies depending on the type of theoretical model used to inform the design of the intervention).

If at least 10 studies had been available for a particular outcome and if feasible, we would have performed a meta‐regression. This was to be undertaken using Stata Software with the metareg command, including trial characteristics as covariates. However, we did not identify a sufficient number of studies within review comparisons to allow performance of subgroup analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses to investigate the robustness of the results, including assessing the effects of:

including only studies with low risk of bias in the selection bias domain in analysis (i.e. sequence generation and allocation concealment);

including only studies with low risk of bias in the attrition bias domain in analysis (i.e. incomplete outcome data);

using a fixed‐effect model of analysis for all the studies;

using a fixed‐effect model for analysis of studies with low risk of bias in the selection bias domain; and

using a fixed‐effect model for analysis of studies with low risk of bias in the attrition bias domain.

Again, we did not identify a sufficient number of studies within review comparisons to enable performance of sensitivity analyses.

Summary of findings tables

We prepared 'Summary of findings' tables to present the results for each of the major primary outcomes, based on meta‐analysis or narrative synthesis. We converted results into absolute effects when possible and provided a source and rationale for each assumed risk cited in the table(s) when presented. Two authors independently (PP, RR) assessed the overall quality of the evidence as implemented and described in the GRADEprofiler (GRADEpro 2016) software and chapter 11 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2011). We considered the following criteria to assess the quality of the evidence: limitations of studies (risk of bias), inconsistency of results, indirectness of the evidence, imprecision and publication bias, downgrading the quality where appropriate. We did this for all primary and secondary outcomes reported in the review.

As there were many prevention and long‐term management areas and comparisons included in this review, two authors (PP, RR) made the decision to limit the number of 'Summary of findings' tables presented. We examined the prevention and long‐term management areas covered by the review, assessed the numbers of studies contributing data to each of these areas, and determined the direction of results for each area (positive, negative or inconclusive). We then made the decision to report in 'Summary of findings' tables only those areas of prevention and/or long‐term management where four or more studies contributed data.

We also determined that in the review, we would represent both comparisons presented and those not presented in 'Summary of findings' tables, describing results that were positive, negative, or inconclusive.

We took this approach in order to be confident that we were not selectively reporting and presenting positive results (those in favour of the intervention) over negative or inconclusive results.

As the included studies covered a very large range of preventive care and long‐term management decisions, we also made the pragmatic decision not to report only a single comparison in each 'Summary of findings' table. Instead we chose to present all the main results for primary outcomes within a given preventive healthcare/long‐term management area, irrespective of the comparisons being made. We clearly identified the different comparisons in each case within each 'Summary of findings' table. The reasons for doing so were as follows.

Reporting by different disease/prevention areas together (i.e. by comparison) would have resulted in significant clinical heterogeneity, as the populations and the likely effects of interventions on targeted behaviours and clinical outcomes varied considerably.

Given the above point, if we had further split tables by comparisons, it would have most likely meant creation and reporting of more than 30 tables, many with sparse data that would not be informative to most users or readers of this review.

We have otherwise not deviated from the advice on preparing 'Summary of findings' tables outlined in Schünemann 2011.

Involvement of non‐governmental organisations (NGOs) that represent a range of potential user groups was an important part of the project development. We contacted NGOs such as the Diabetes Research Network and requested one of the members (AM) to guide us in the review process, particularly in considering outcomes of interest to users and methods of disseminating results to user communities. The protocol was peer reviewed by at least one consumer, as part of the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group's standard editorial process.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies for more details about individual studies.

Additional tables also contain supplementary information: Table 14 presents further information on participants of included studies, Table 15 reports details of the interventions assessed, and Table 16 presents an assessment of intervention complexity for studies evaluating the effects of highly complex (i.e. multimodal) ATCS interventions.

2. Participants.

| Study ID | Study typea | Study subtypeb | Country | Sample size | Mean age (years unless stated otherwise) | Male (%) | Female (%) | Ethnicityc | Duration of condition | Comorbidities, medication | Incentives for participation | Incentives |

| Tucker 2012 | P | Alcohol misuse | USA | 187 | 45 | 63 | 37 | White ‐ 54% Other ‐ 46% |

— | — | Yes | Visa gift cards or checks (USD 50 per in‐person interview, USD 15 per phone interview). IG participants received USD 0.50 minimum for each daily call and USD 1.00 after seven consecutive calls |

| Franzini 2000 | P | I | USA | 1138 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Hess 2013 | P | I | USA | 11,982 | 72 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Dini 2000 | P | I | USA | 1227 | 2‐3 months | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| LeBaron 2004 | P | I | USA | 3050 | 9 monthsd | 49 | 51 | Black ‐ 76% Hispanic ‐ 14% White ‐ 7% Other – 3% |

— | — | — | — |

| Lieu 1998 | P | I | USA | 752 | 20 months | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Linkins 1994 | P | I | USA | 8002 | — | 51 | 49 | Black ‐ 50% White ‐ 45% Other – 5% |

— | — | — | — |

| Nassar 2014 | P | I | USA | 50 | 24 | 0 | 100 | Black ‐ 86% White ‐ 14% |

— | — | Yes | USD 35 per month to help pay for cell phone service or a free, unlimited minutes cell phone until 6 weeks postpartum |

| Stehr‐Green 1993 | P | I | USA | 229 | 9 months | 52 | 48 | Black ‐ 90% Other – 7% Hispanic ‐ 3% |

— | — | — | — |

| Szilagyi 2006 | P | I | USA | 3006 | — | 51 | 49 | Other – 41% Black ‐ 35% White ‐ 17% Hispanic ‐ 7% |

— | — | — | — |

| Szilagyi 2013 | P | I | USA | 4115 | 14 | 50 | 50 | — | — | — | — | — |

| David 2012 | P | Physical activity | USA | 71 | 57 | 0 | 100 | White ‐ 93% Other ‐ 7% |

— | — | — | — |

| Dubbert 2002 | P | Physical activity | USA | 181 | 69 | 99 | 1 | — | — | Mean (SD) number of comorbidities IG: 3.8 (1.5) CG: 3.9 (1.4) |

Yes | USD 15 for completing each visit to help defray expenses |

| Jarvis 1997 | P | Physical activity | USA | 85 | 67 | 24 | 76 | Other ‐ 70% Black ‐ 30% |

— | Mean co‐morbidities: 3 | — | — |

| King 2007 | P | Physical activity | USA | 218 | 61 | 31 | 69 | White ‐ 90% Other ‐ 10% |

— | — | — | — |

| Morey 2009 | P | Physical activity | USA | 398 | 78 | 100 | 0 | White ‐ 77% Black ‐ 23% |

— | Mean (SD) number of diseases IG: 5.2 (2.5) CG: 5.5 (2.7) |

— | — |

| Morey 2012 | P | Physical activity | USA | 302 | 67 | 97 | 3 | White ‐ 70% | — | Mean (SD) number of comorbidities IG: 4.2 (2.4) CG: 3.9 (2.4) |

— | — |

| Pinto 2002 | P | Physical activity | USA | 298 | 46 | 28 | 72 | White ‐ 45% Black ‐ 45% Other ‐ 10% |

— | — | — | — |

| Sparrow 2011 | P | Physical activity | USA | 103 | 71 | 69 | 31 | — | — | Depression (unclear %) | — | — |

| Baker 2014 | P | Screening | USA | 450 | 60 | 28 | 72 | Hispanic 87% Other‐ 13% |

— | ≥ 1 long‐term conditions ‐ 68% | No | — |

| Cohen‐Cline 2014 | P | Screening | USA | 11,010 | 61 | 54 | 46 | White ‐ 86% Other ‐ 14% |

— | — | — | — |

| Corkrey 2005 | P | Screening | Australia | 75,532 | — | 0 | 100 | — | — | — | — | — |

| DeFrank 2009 | P | Screening | USA | 3547 | — | 0 | 100 | White ‐ 88% Black ‐ 11% Asian or Other ‐ 1% |

— | — | — | — |

| Durant 2014 | P | Screening | USA | 47,097 | 58 | 47 | 53 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Fiscella 2011 | P | Screening | USA | 469 | — | 56 (for colorectal cancer) |

44 (for colorectal cancer) |

White ‐ 61% Black ‐ 28% Latinos ‐ 5% Asian ‐ 5% |

— | — | — | — |

| Fortuna 2014 | P | Screening | USA | 1008 | — | 45 | 55 | White ‐ 48% Black ‐ 37% Other ‐ 15% |

— | — | No | — |

| Hendren 2014 | P | Screening | USA | 366 | — | — | — | White ‐ 50% Black ‐ 41% Other (including Hispanic) ‐ 9% |

— | — | — | — |

| Heyworth 2014 | P | Screening | USA | 4685 | 57 | 0 | 100 | — | — | Anticonvulsants ‐ 6% Corticosteroids ‐ 4% COPD (unclear %) Oophorectomy ‐ 3% |

— | — |

| Mosen 2010 | P | Screening | USA | 6000 | 60 | 50 | 50 | White ‐ 93% Other ‐ 7% |

— | Obesity ‐ 40% | — | — |

| Phillips 2015 | P | Screening | USA | 685 | 58 | 38 | 62 | Non‐Hispanic white ‐ 78% Black ‐ 13% Other ‐ 9% |

— | — | — | — |

| Simon 2010a | P | Screening | USA | 20,936 | 57 | 47 | 53 | White ‐ 86% Other ‐ 9% Black ‐ 5% |

— | — | — | — |

| Solomon 2007 | P | Screening | USA | 1973 | 69 | 8 | 92 | — | — | Use of oral glucocorticoids ‐ 22% Fractures ‐ 12% |

— | — |

| Mahoney 2003 | P | Stress management | USA | 100 (caregiver) | 63 (caregiver) | 22 (caregiver) | 78 (caregiver) | Black ‐ 64% Hispanic ‐ 21% White ‐ 15% Other ‐ 1% |

— | — | — | — |

| Aharonovich 2012 | P | Substance use | USA | 33 | 46 | 76 | 24 | White ‐ 64% White ‐ 15% Hispanic ‐ 21% |

— | HIV medication ‐ 64% Hepatitis A, B, or C ‐ 49% |

Yes | USD 20 gift certificates for each assessment |

| Bennett 2012 | P | Weight management | USA | 365 | 55 | 31 | 69 | Black ‐ 71% Hispanic ‐ 13% White ‐ 4% Other ‐ 2% |

— | Cholesterol medication ‐ 36% Diabetes medication ‐ 30% Mean BMI ‐ 37 kg/m2 |

Yes | USD 50 reimbursement at the first 3 follow‐up visits and USD 75 at 24 months |

| Bennett 2013 | P | Weight management | USA | 194 | 35 | 0 | 100 | Black ‐ 100% | — | Hypertension ‐ 36% Metabolic syndrome ‐ 31% Depression ‐ 22% Diabetes mellitus ‐ 7% |

Yes | Reimbursements of USD 50 each at baseline and at all follow‐up study visits |

| Estabrooks 2008 | P | Weight management | USA | 77 | 59 | 29 | 71 | White ‐ 68% Hispanic ‐ 18% Other ‐ 7% Black ‐ 4% Asian ‐ 3% |

— | — | — | — |

| Estabrooks 2009 | P | Weight management | USA | 220 | 11 | 54 | 46 | White‐ 63% Hispanic ‐ 26% Other ‐ 11% |

— | — | — | — |

| Goulis 2004 | P | Weight management | Greece | 122 | 44 | 12 | 88 | — | — | Hypertension ‐ 13% Diabetes mellitus ‐ 2% |

— | — |

| Vance 2011 | P | Weight management | USA | 140 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Wright 2013 | P | Weight management | USA | 50 (child) | 10 (child) 40 (parent) |

58 (child) 4 (parent) | 42 (child) 96 (parent) | Black ‐ 72% Other ‐ 22% White ‐ 6% (parent) |

— | BMI (child) ‐ 25.7 kg/m2 BMI (parent) ‐ 34 kg/m2 |

Yes | For completing assessments (USD 40 parents; USD 10 child) |

| Dini 1995 | E | Appointment reminder | USA | 517 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Griffin 2011 | E | Appointment reminder | USA | 3610 | 63 | 95 | 5 | White ‐ 83% Other ‐ 16% Hispanic ‐ 1% |

— | — | — | — |

| Maxwell 2001 | E | Appointment reminder | USA | 2304 | 29 | — | 100 | Hispanic ‐ 66% Black ‐ 19% White ‐ 13% Other ‐ 2% |

— | — | — | — |

| Parikh 2010 | E | Appointment reminder | USA | 12,092 | 56 | 43 | 57 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Reekie 1998 | E | Appointment reminder | UK | 1000 | — | 33 | 67 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Tanke 1994 | E | Appointment reminder | USA | 2008 | 19d | 54 | 46 | Spanish‐speaking ‐ 39% Vietnamese‐speaking ‐ 28% English‐speaking ‐14% Other – 13% Tagalog‐speaking Filipino – 6% |

— | — | — | — |

| Tanke 1997 | E | Appointment reminder | USA | 701 | < 12e | 45 | 55 | English‐speaking ‐ 59% Spanish‐speaking ‐ 29% Vietnamese‐speaking ‐ 3% Other – 9% |

— | — | — | — |

| Moore 2013 | M | Illicit drugs addiction | USA | 36 | 41 | 58 | 42 | White ‐ 58% Black ‐ 28% Other – 14% |

On methadone treatment mean = 21.7 | — | Yes | USD 20 per week for completing weekly assessments and providing a urine sample |

| Andersson 2012 | M | Alcohol consumption | Sweden | 1423 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Hasin 2013 | M | Alcohol consumption | USA | 254 | 46 | 78 | 22 | Black ‐ 49% Hispanic ‐ 45% Other – 6% |

12.8y | HIV/AIDS (unclear %) | Yes | USD 20; USD 40 at last 2 post‐treatment follow‐ups |

| Helzer 2008 | M | Alcohol consumption | USA | 338 | 46 | 64 | 36 | White ‐ 97% | Currently dependent ‐ 67% | — | Yes | USD 30 for the index, USD 25 for the 3‐month, and USD 60 for the 6‐month assessment |

| Litt 2009 | M | Alcohol consumption | USA | 110 | 49 | 58 | 42 | White ‐ 86% Black ‐9%, Hispanic‐3% Other‐2% |

Mean of 1.2 (SD 2.4) treatments for alcohol dependence | — | Yes | The possible total incentive was USD 50.00 per week |

| Mundt 2006 | M | Alcohol consumption | USA | 60 | 42 | 55 | 45 | White ‐ 95% Black ‐5% |

52.3 heavy drinking days within past 3 months | — | Yes | Patients were paid USD 75 for the 30‐day follow‐up, USD 125 for the 90‐day follow‐up, and USD 200 for the 180‐day follow‐up |

| Rose 2015 | M | Alcohol consumption | USA | 158 | 49 | 53 | 47 | — | Regular alcohol use mean = 17.94 years | — | Yes | USD 25 for each interview |

| Rubin 2012 | M | Alcohol consumption | USA | 47 | 57 | 60 | 40 | Caucasian ‐ 83% African‐American ‐ 13% | — | — | — | — |

| Simpson 2005 | M | Alcohol consumption | USA | 98 | 46 | 91 | 9 | White ‐ 45% Black ‐ 40% Native American ‐ 7% Other ‐ 6% Hispanic ‐ 2% |

— | — | Yes | USD 25.00 each for the baseline and for the follow‐up assessments |

| Vollmer 2006 | M | Asthma | USA | 6948 | 52 | 35 | 65 | White ‐ 92% Other ‐ 8% |

— | Beta agonist ‐ 55% Oral steroids ‐ 46% COPD ‐ 33% |

— | — |

| Xu 2010 | M | Asthma | Australia | 121 | 7 | 53 | 47 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Cleeland 2011 | M | Cancer | USA | 79 | 60 | 53 | 47 | White ‐ 85% Black ‐ 15% |

— | — | — | — |

| Kroenke 2010 | M | Cancer | USA | 405 | 59 | 32 | 68 | White ‐ 80% Black‐ 18% Other ‐ 2% |

— | Depression ‐ 76% Pain ‐ 68% |

— | — |

| Mooney 2014 | M | Cancer | USA | 250 | 55 | 24 | 76 | White/Caucasian ‐ 91% Other ‐ 9% |

— | — | — | — |

| Siegel 1992 | M | Cancer | USA | 239 | 58 | 50 | 50 | White ‐ 89% Black‐ 6% Hispanic ‐ 4% Other 1% |

Mean (SD) time since cancer diagnosis‐ IG: 36 months (35) CG: 26 months (32) |

Mean (SD) symptoms (out of 13) IG: 3.4 (2.2) CG: 4.0 (2.4) |

— | — |

| Sikorskii 2007 | M | Cancer | USA | 437 | 57 | 25 | 75 | — | — | Mean comorbidities: 2 | — | — |

| Spoelstra 2013 | M | Cancer | USA | 119 | 60 | 31 | 69 | White ‐ 76% Asian ‐ 17 % Black ‐ 7% |

— | Capecitabine ‐ 35% Erlotinib ‐ 24% Lapatinib ‐ 9% Imatinibf ‐ 8% Temozolomide ‐ 6% Sunitinib ‐ 5% Sorafenib ‐ 2.5% Methotrexate ‐ 1.7% Cyclophosphamide ‐ 0.8% |

— | — |

| Yount 2014 | M | Cancer | USA | 253 | 61 | 49 | 51 | White ‐ 58% Black ‐ 36% Other ‐ 6% | — | Planned single chemotherapy ‐ 9% Planned combination chemotherapy ‐ 90% |

— | — |

| Kroenke 2014 | M | Chronic pain | USA | 250 | 55 | 83 | 17 | White ‐ 77 % | ≤ 5 years = 29% 6‐10 years = 19% > 10 years = 52% |

Major depression‐ 24% Post‐traumatic stress disorder‐ 17% |

— | — |

| Naylor 2008 | M | Chronic pain | USA | 55 | 46 | 14 | 86 | White ‐ 96% Other ‐ 4% |

— | — | — | — |

| Halpin 2009 | M | COPD | UK | 79 | 69 | 74 | 26 | — | — | SABA ‐ 75% LAMA ‐ 43% LABA/ICS ‐ 43% ICS ‐ 33% SAMA ‐ 32% Oral steroids ‐ 25% LABA ‐ 18% |

— | — |

| Adams 2014 | M | Adherence | USA | 475 | 5 (child) 35 (parent) | 52 (child) 7 (parent) | 48 (child) 93 (parent) | Black ‐ 67% (child) 47% (parent); Other – 33% (child) 53% (parent) |

— | — | Yes | Gift cards |

| Bender 2010 | M | Adherence | USA | 50 | 42 | 36 | 64 | White ‐ 58% Black ‐ 20% Hispanic ‐ 18% Asian ‐ 4% |

— | — | Yes | USD 25 for each completed visit |

| Bender 2014 | M | Adherence | USA | 1187 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Boland 2014 | M | Adherence | USA | 70 | 66 | 49 | 51 | African American ‐ 58% European ‐ 32% Asian ‐ 6% Hispanic ‐ 3% Middle Eastern ‐ 1% |

Median 5 years in IG; 4.5 years in CG | Bimatoprost ‐ 11.5% Travoprost ‐ 17.5% Latanoprost ‐ 71.5% Bilateral medication ‐ 70% |

— | — |

| Cvietusa 2012 | M | Adherence | USA | 1393 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Derose 2009 | M | Adherence | USA | 13,057 | 51 | 54 | 46 | Other ‐ 48 % White ‐ 23% Hispanic ‐ 14% Black ‐ 10% Asian ‐ 5% |

— | — | — | — |

| Derose 2013 | M | Adherence | USA | 5216 | 56 | 49 | 51 | Hispanic ‐ 30% White ‐ 28% Unknown ‐ 23% Black ‐ 10% Asian and Pacific Islander ‐ 7.1% Other ‐ 1.7% Native American‐ 0.2% |

— | Mean low‐density lipoproteins = 146 mg/dL | — | — |

| Feldstein 2006 | M | Adherence | USA | 961 | 59 | 47 | 53 | — | — | Statins ‐ 32% Depression ‐ 11% |

— | — |

| Friedman 1996 | M | Adherence | USA | 267 | 77 | 23 | 77 | Other ‐ 89 % Black: 11% |

— | Other – 81% Heart disease ‐ 32% Diabetes mellitus ‐ 18% Stroke ‐ 7% |

— | — |

| Glanz 2012 | M | Adherence | USA | 312 | 63 | 62 | 38 | Black ‐ 91% White ‐ 9% |

— | — | Yes | USD 25 gift card |

| Green 2011 | M | Adherence | USA | 8306 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Ho 2014 | M | Adherence | USA | 241 | 64 | 98 | 2 | White ‐ 78% | — | Hypertension ‐ 91% Hyperlipidaemia ‐ 85% Diabetes mellitus ‐ 45% Chronic kidney disease ‐ 23% Chronic lung disease ‐ 20% Prior heart failure ‐ 12% Peripheral arterial disease ‐ 10% Cerebrovascular disease ‐ 7% |

— | — |

| Leirer 1991 | M | Adherence | USA | 16 | 71 | 31 | 69 | — | — | — | Yes | USD 25 for participating |

| Lim 2013 | M | Adherence | USA | 80 | 66 | 51 | 49 | White ‐ 62% African‐American ‐ 10% Hispanic/Latino ‐ 9% Asian ‐ 9% East Indian ‐ 6% |

Mean IG: 25.79 months; CG: 22.1 months |

Number of medical problems: IG: 3.43 CG: 3.32 |

— | — |

| Migneault 2012 | M | Adherence | USA | 337 | 57 | 30 | 70 | Black ‐ 100% | — | BMI ‐ 34.4 kg/m2 Diabetes ‐ 38% Stroke ‐ 7.5% |

— | — |

| Mu 2013 | M | Adherence | USA | 4,237,821 | 56 | 38.5 | 61.5 | — | — | Correspondence with the author: "All participants were on maintenance medications" | — | — |

| Ownby 2012 | M | Adherence | USA | 27 | 80 | — | — | — | — | Participants had cognitive (memory) impairment and were on donepezil, rivastigmine, or galantamine | — | — |

| Patel 2007 | M | Adherence | USA | 15,051 | 57 | 53 | 47 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Reynolds 2011 | M | Adherence | USA | 30,610 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Sherrard 2009 | M | Adherence | Canada | 331 | 63 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Simon 2010b | M | Adherence | USA | 1200 | 51 | 62 | 38 | Other ‐ 95% Black ‐ 5% |

— | Insulin ‐ 19.4% (participants) | — | — |

| Stacy 2009 | M | Adherence | USA | 497 | 54 | 38 | 62 | — | — | Lipitor – 54% Zocor – 16% Other statin – 16% |

— | — |

| Stuart 2003 | M | Adherence | USA | 647 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Vollmer 2011 | M | Adherence | USA | 8517 | 54 | 34 | 66 | White ‐ 50% Other – 26% Asian ‐ 11% Mixed – 7% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander ‐ 4% Black ‐ 2% American Indian/Alaskan Native – 1% |

— | COPD ‐ 33% | — | — |

| Vollmer 2014 | M | Adherence | USA | 21,752 | 64 | 53 | 47 | White ‐ 47% Asian ‐ 17% Black ‐15% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander ‐ 11% Black ‐ 2% American Indian/Alaskan Native – 1% |

— | Diabetes mellitus ‐ 78% CVD ‐ 36% Statin only ‐ 40% ACEI/ARB only ‐ 25% Statin and ACEI/ARB ‐ 35% low‐density lipoproteins among statin users (mean) = 93.4 mg/dL |

— | — |

| Graziano 2009 | M | Diabetes mellitus | USA | 119 | 62 | 55 | 45 | White ‐ 77% Other – 23% |

— | — | Yes | USD 25 |

| Homko 2012 | M | Diabetes mellitus | USA | 80 | 30 | 0 | 100 | White ‐ 41% Black ‐ 34% Hispanic ‐ 18% Asians or others ‐ 7% |

— | BMI ‐ 34.1 kg/m2 | — | — |

| Katalenich 2015 | M | Diabetes mellitus | USA | 98 | 59 | 40 | 60 | Black ‐ 65% White ‐ 30% Other ‐ 3% Hispanic ‐ 1% Asian ‐ 1% |

— | Other antidiabetic medications + insulin ‐ 80% Basal‐bolus regimen ‐ 40% Long‐acting insulin only ‐ 33% Mixed insulin only ‐ 17% Short‐acting insulin only ‐ 10% |

— | — |

| Khanna 2014 | M | Diabetes mellitus | USA | 75 | 52 | 59 | 41 | Hispanic ‐ 100% | — | — | Yes | USD 10 for initial visit and USD 20 incentive card at the follow‐up |

| Kim 2014 | M | Diabetes mellitus | USA | 100 | — | — | — | — | — | Psychiatric illness ‐ 46% Had been hospitalised over the past year ‐ 28% |

— | — |

| Lorig 2008 | M | Diabetes mellitus | USA | 417 | 53 | 38 | 62 | Hispanic ‐ 100% | — | — | — | — |

| Piette 2000 | M | Diabetes mellitus | USA | 248 | 55 | 41 | 59 | Hispanic ‐ 50% White ‐ 29% Other – 21% |

— | BMI ‐ 33.7 kg/m2 Mean comorbidities: 1 |

— | — |

| Piette 2001 | M | Diabetes mellitus | USA | 272 | 61 | 97 | 3 | White ‐ 60% Black ‐ 18% Hispanic ‐ 12% Other ‐ 10% |

— | BMI ‐ 31 kg/m2 Mean comorbidities: 2 |

— | — |

| Schillinger 2009 | M | Diabetes mellitus | USA | 339 | 56 | 43 | 57 | Hispanic ‐ 47% Asian ‐ 22% Black ‐ 20% White ‐ 8% Other ‐ 2% |

— | BMI: 31 kg/m2 | Yes | USD 15 and USD 25 for the baseline and 1‐year follow‐up visits, respectively |