Abstract

We have established early-gestation chorionic villus–derived placenta mesenchymal stromal cells (PMSCs) as a potential treatment for spina bifida (SB), a neural tube defect. Our preclinical studies demonstrated that PMSCs have the potential to cure hind limb paralysis in the fetal lamb model of SB via a paracrine mechanism. PMSCs exhibit neuroprotective function by increasing cell number and neurites, as shown by indirect coculture and direct addition of PMSC-conditioned medium to the staurosporine-induced apoptotic human neuroblastoma cell line, SH-SY5Y. PMSC-conditioned medium suppressed caspase activity in apoptotic SH-SY5Y cells, suggesting that PMSC secretome contributes to neuronal survival after injury. As a part of PMSC secretome, PMSC exosomes were isolated and extensively characterized; their addition to apoptotic SH-SY5Y cells mediated an increase in neurites, suggesting that they exhibit neuroprotective function. Proteomic and RNA sequencing analysis revealed that PMSC exosomes contain several proteins and RNAs involved in neuronal survival and development. Galectin 1 was highly expressed on the surface of PMSCs and PMSC exosomes. Preincubation of exosomes with anti-galectin 1 antibody decreased their neuroprotective effect, suggesting that PMSC exosomes likely impart their effect via binding of galectin 1 to cells. Future studies will include in-depth analyses of the role of PMSC exosomes on neuroprotection and their clinical applications.—Kumar, P., Becker, J. C., Gao, K., Carney, R. P., Lankford, L., Keller, B. A., Herout, K., Lam, K. S., Farmer, D. L., Wang, A. Neuroprotective effect of placenta-derived mesenchymal stromal cells: role of exosomes.

Keywords: spina bifida, galectin 1, apoptosis, mesenchymal stromal cells, neuroprotection

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) display a high regenerative potential by possessing neuroprotective, immunomodulatory, and angiogenic functions (1). MSCs are a safe and effective candidate for cell therapy with a plethora of clinical applications. Although MSCs are known to possess a multilineage differentiation potential, to date, most of their function has been attributed to a paracrine mechanism of action (1). The numerous bioactive factors secreted by MSCs are capable of orchestrating key biologic functions, including protecting neurons from apoptosis, activating macrophages, and promoting angiogenesis (2–4). In addition to free secreted proteins, MSCs also secrete exosomes, which are nanosized vesicles generated via tightly controlled biogenesis by inward budding of the endosomal membrane. Exosomes are typically reported to range from 40 to 150 nm in size and traffic many types of small noncoding RNAs, especially microRNAs (miRNAs), in addition to mRNAs, cytokines, metabolites, and proteins; thus, they have been identified as powerful signaling units carrying complex messages for intercellular communication (5, 6). Exosomes have been reported to play a role in several biologic processes, including wound healing, angiogenesis, and neuroregeneration (7–10). This has led to several regenerative therapy applications using MSC-released exosomes (11–13).

MSCs can be isolated from several tissue sources, including bone marrow, placenta, adipose, and amniotic fluid (14–18). Several labs have isolated and characterized placenta-derived MSCs (PMSCs) from chorionic villus tissue of placenta obtained from different gestational ages (19). Our lab has extensively characterized PMSCs from early-gestation placenta, which are shown to possess all of the phenotypic characteristics of MSCs and secrete high levels of the neuroprotective, immunomodulatory, and angiogenic factors, including brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), VEGF, and the chemokines monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), IL-8, IL-6, and TIMP 1 (16, 19).

Spina bifida (SB) is a congenital defect of neurulation that occurs very early during pregnancy, resulting in incomplete closure of the spinal column. This leads to irreparable damage of the spinal cord that is due to exposure to the toxins and shear stress of the amniotic fluid throughout the pregnancy (20). Children born with SB have lifelong paralysis and additional complications, including bowel and bladder incontinence and hydrocephalus. The current standard of care for fetuses diagnosed prenatally with SB is in utero skin closure during the second trimester of pregnancy. Although this treatment significantly decreases the rates of ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement, its effects on motor function are less dramatic (21, 22). Several studies from our lab have shown that in utero transplantation of PMSCs in the surgically induced ovine SB model greatly improved the motor function recovery of PMSC-treated lambs compared with controls. Lambs treated with PMSCs were more likely to ambulate at birth and demonstrated increased numbers of motor neurons in the spinal cord tissue (23, 24). In this model, there was no evidence of engraftment of PMSCs in the host tissue; this effect can most likely be attributed to the paracrine function of the PMSCs rather than their differentiation potential (23, 24). Although apoptosis is required for remodeling during normal neural tube development, abnormally high levels of apoptosis have been shown in the neural tissue of humans with SB. This suggests that apoptosis plays a major role in the development and incomplete closure of the neural tube (25). In the retinoic acid-induced rat SB model, in utero transplantation of PMSCs or rat bone marrow–derived MSCs led to a significant decrease in the number of apoptotic cells (26, 27). Together these studies suggest that PMSCs possess a high neuroprotective potential attributable to a paracrine mechanism of action.

To further elucidate the mechanism of action of PMSCs, we characterized their in vitro neuroprotective effect and demonstrated that exosomes, as a part of the secretome of PMSCs, play a key role in their neuroprotective function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation and characterization of PMSCs

We used PMSC cell banks from 3 donors as described in Lankford et al. (19), plus a cell bank from a fourth donor, which were in turn characterized by flow cytometry and multipotency in the same manner. Isolated PMSCs were cultured in medium containing DMEM high glucose, 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 20 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor and 20 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (Advent Bio, Elk Grove Village, IL, USA), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin referred as D-5 medium, at 37°C and 5% CO2, and were used up to passage 5.

Cytotoxicity assay

Human neuroblastoma cell line (SH-SY5Y) was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA), cultured in DMEM high glucose containing 5% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (S-5 medium) at 37°C and 5% CO2, and was used up to passage 15. SH-SY5Y cells were seeded at 100,000 cells/cm2 in 24-well tissue culture–treated dishes and cultured in S-5 medium for 24 h. Cells were subsequently treated with 1 µM staurosporine (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) or DMSO (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA) (control) for 4 h. Caspase activity was assessed using the Caspase-3 Activity Assay Kit (Cell Signaling Technology). Briefly, cells were lysed with 1× cell lysis buffer, protein quantified using Bicinchoninic Acid Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 5 µg of protein used to test the caspase activity. For TUNEL analysis, after cells were treated with staurosporine or DMSO, they were fixed in 10% formalin for 15 min and stained using the Click-iT TUNEL Alexa Fluor 488 Imaging Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), per the manufacturer’s protocol and DAPI. Cells were imaged at ×5 magnification using an Axio Observer D1 inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) and manually counted.

To assess cytotoxicity by Western blotting, 0.5 × 106 SH-SY5Y cells were seeded in 6-well dishes and treated with staurosporine, as previously described. Cells were then lysed in RIPA lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) plus 1× protease inhibitors (MilliporeSigma) and 5 mM EDTA and then quantified by bicinchoninic acid assay. Thirty micrograms of protein was loaded onto 4–15% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gel (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and was run at a constant voltage (150 V) using 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Proteins were then transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with 1:500 dilution of caspase-3, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) (Cell Signaling Technology), and 1:5000 GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) antibodies diluted in 5% nonfat dry milk in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, and 0.5% Tween-20. Blots were then probed with their respective secondary antibodies and developed using Chemidoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Neuroprotection assay by indirect coculture

SH-SY5Y cells were seeded at 100,000 cells/cm2 in 12-well tissue culture–treated dishes and cultured in S-5 medium for 24 h. PMSCs were seeded directly onto 12-well hanging 0.4 µm millicell inserts (MilliporeSigma) coated with 50 µg/ml type I rat tail collagen (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) at a density of 300,000 cells/cm2 and cultured in D-5 medium for 24 h. For the neuroprotection assay, apoptosis was induced by treating cells with 1 µM staurosporine for 4 h. After treatment, the cells were washed twice with 1 ml of S-5 medium, and 1950 µl of S-5 medium was added to the cells. PMSCs in coculture inserts were washed twice with S-5 medium, and 400 µl of S-5 medium was added to the inserts. The inserts were then placed onto the apoptotic SH-SY5Y cells and incubated for 96 h at 37°C, 5% CO2. At 96 h, the inserts were removed, the cells were washed once with PBS, and 2 µM calcein AM (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in PBS was added to the cells and stained for 2 min. The cells were then imaged at 5 random positions per well at ×5 magnification using a motorized Axio Observer D1 inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss). The images were subsequently processed by WimNeuron Image Analysis (Onimagin Technologies, Cordoba, Spain) for neurite outgrowth analysis and manual counting of live cells.

Complete conditioned medium collection

PMSCs were seeded at 20,000 cells/cm2 in tissue culture–treated T150 flasks in 25 ml of D-5 medium for 48 h at 37°C, 5% CO2. Conditioned medium was collected and centrifuged at 1500 g for 20 min. Total number of cells was also counted. The medium was concentrated using Amicon Ultra-15 Centrifugal Filter Units (MilliporeSigma) with a 3 kDa MW cutoff to a final volume of 1 ml, and then was divided in aliquots and stored at −80°C. D-5 medium, concentrated similarly, served as a control.

Neuroprotection assay and caspase activity using conditioned medium

SH-SY5Y cells were seeded in 48-well dishes and treated with staurosporine as described above. After treatment, cells were gently washed twice using S-5 medium. Concentrated conditioned medium equivalent to 0.5 × 106 cells or an equivalent volume of concentrated D-5 medium (control), as previously described, was diluted in S-5 medium to a final volume of 300 µl and was added to the apoptotic SH-SY5Y cells. The cells were incubated for 72 h at 37°C, 5% CO2, and then imaged and analyzed as described above for indirect coculture studies. To assess the effect of conditioned medium on caspase activity, SH-SY5Y cells were seeded at 30,000 cells per well of a 96-well dish, cultured for 24 h, and staurosporine treated for 4 h, as previously described. After treatment, cells were washed twice with S-5 medium. Conditioned medium equivalent to 0.5 × 106 cells or an equal volume of concentrated D-5 medium was added and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2. One or three hours after addition of the medium, caspase activity was assessed according to protocol using the Caspase-3 Activity Assay Kit (Cell Signaling Technology).

Exosome isolation

Exosome-depleted FBS was prepared by spinning FBS at 112,700 g using the SW28 rotor and L7 Ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) for 16 h at 4°C. The supernatant was recovered and divided in aliquots of 25 ml and stored at −20°C. PMSCs at passage 4 were seeded at a density of 20,000 cells/cm2 in tissue culture–treated T175 flasks in 20 ml of exosome-depleted FBS containing D-5 medium for 48 h at 37°C, 5% CO2. Conditioned medium was collected, and exosomes were isolated by differential centrifugation (28). Briefly, the medium was sequentially centrifuged at 300 g for 10 min, 2000 g for 20 min, and passed through a 0.2-µm filter. The medium was concentrated using Amicon Ultra-15 Centrifugal Filter Units with a 100 kDa MW cutoff (MilliporeSigma), transferred to thickwall polypropylene tubes (355462; Beckman Coulter), and centrifuged at 8836 g using the SW28 rotor and L7 Ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter). The supernatant was transferred to fresh tubes, and the pellet was discarded. To collect exosomes, the supernatant was centrifuged at 112,700 g for 90 min, and the pellet was resuspended in PBS and spun again at the same speed and time. The final pellet was resuspended in 10 µl of PBS per T175 flask and stored in aliquots at −80°C.

Exosome characterization

Isolated exosomes were characterized by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) to obtain number and size distribution using the NanoSight LM10 (Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, United Kingdom) equipped with a 404-nm laser and sCMOS camera. A small aliquot from each exosome isolation was frozen separately for NTA (typically ∼5 μl) and thawed just prior to measurement. The sample was diluted in triple-filtered (0.2 μm) MilliQ-water to reach the appropriate concentration range of 3–20 108 particles/ml. Three 90-s videos were recorded for each sample at camera level 12 using NTA v.3.0 software. Data were consistently analyzed with a detection threshold of 3 and screen gain of 10. Typically, 100-fold lower dilutions than those determined for NTA were made to characterize single extracellular vesicle (EV) chemical composition using our established method of laser-trapping Raman spectroscopy (LTRS) (29, 30). Many single exosomes per donor were sampled carefully from throughout the diluted solution for optical trapping and Raman spectra measurement (5 min integration time per vesicle). For each of the donor samples, no significant further variation occurred after n = 6, and at least 10 vesicles were measured from each donor. Raw spectra were subjected to cosmic ray removal, background correction, and smoothing using a custom MatLab script (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed using an established negative-staining protocol (28). Briefly, following fixing and staining of adsorbed exosomes, electron microscope images were examined using a CM120 transmission electron microscope (Philips/FEI BioTwin, Amsterdam, Netherlands) at 80 kV. For Western blotting analysis, 10 µg of total cell lysate (generated by lysing PMSCs in RIPA lysis buffer) or 10 µl of exosomes were treated with either NuPAGE LDS Sample Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing reducing agent DTT [for detecting ALIX, tumor susceptibility gene 101 (TSG101), calnexin, and galectin 1 proteins] or without DTT (for detecting CD9 and CD63 proteins), and heated to 90°C. The samples were run, transferred, probed with 1:500 dilution of primary antibodies ALIX, TSG101, CD9 (MilliporeSigma), calnexin (Cell Signaling Technology), CD63 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1:1000 dilution of anti-galectin 1 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology), and imaged as previously described for the cytotoxicity assay. For proteomic analysis of exosomes, the final pellet was additionally washed twice with PBS, and the pellet was subjected to proteomics analysis by tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) using the Q-Exactive orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The analysis was performed at the Proteomics Core Facility at the University of California–Davis. Data were analyzed using Scaffold software (v.4.8.4; Proteome Software, Portland, OR, USA), and pathway analysis was executed using the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING) database v.10.5 (31) and the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) v.6.8 (32). Next-generation RNA sequencing (NGS) using high-throughput sequencing technology was performed by the ExoNGS service (CSEQ400A-1) provided by System Biosciences (Palo Alto, CA, USA), using the Exosome-RNA-Seq Maverix Analytic Platform (Maverix Biomics, San Mateo, CA, USA). Gene ontology (GO) analysis of miRNAs involved in the positive regulation of neurogenesis (GO:0050769), negative regulation of neuronal apoptosis (GO:0043524), and axon guidance (GO:0007411) was executed by mirPath v.3.0, TarBase v.7.0, and miRBase v.22 (Diana Tools, Volos, Greece; 33, 34). miRNA pathway analysis was performed by miRNet database using exosome miRNA annotation for target genes and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways analysis of all target genes using the hypergeometric test algorithm (35).

Flow cytometry analysis of galectin 1 expression on PMSCs and PMSC exosomes

PMSCs were analyzed by flow cytometry analysis as previously described in Lankford et al. (19). Briefly, 1 × 106 cells were stained with either 10 µg/ml of rabbit polyclonal anti-galectin 1 antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) or 10 µg/ml control IgG (Abcam). They were then washed and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific). PMSC exosomes were analyzed by on-bead flow cytometry as previously described in Carney et al. (36). Briefly, exosomes (100–200 × 106) were incubated with 3.9-µm latex beads with aldehyde and sulfate groups grafted to the polymer surface (Thermo Fisher Scientific) overnight at 4°C. The beads were then washed 3 times with PBS containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and subsequently incubated with 10 µg/ml of anti-galectin 1, rabbit pAb, or 10 µg/ml control anti-rabbit IgG for 30 min on ice. They were then washed and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated secondary antibody for 30 min on ice. Flow cytometry of the cells and bead-bound exosomes was performed using the Attune NxT Flow Cytometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Data were processed using FlowJo software (BD Biosciences).

EV-depleted conditioned medium collection

PMSCs at passage 4 were seeded at 20,000 cells/cm2 in tissue culture–treated T175 flasks in 20 ml of exosome-depleted FBS containing D-5 medium for 48 h at 37°C, 5% CO2. Conditioned medium was collected and sequentially centrifuged at 300 g for 10 min and 2000 g for 20 min, then passed through a 0.2-µm filter and divided into 2 aliquots. The first aliquot served as complete conditioned medium. The second aliquot was centrifuged at 112,700 g for 90 min using the SW28 rotor and L7 Ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter). The supernatant devoid of EVs was collected. Both the complete conditioned medium and EV-depleted conditioned medium were concentrated as described above to a final volume of 1 ml, divided into aliquots, and stored at −80°C.

Neuroprotection assay for exosomes

SH-SY5Y cells were seeded onto glass-bottom 8-well µ-Slides (Ibidi, Martinsried, Germany) at 100,000 cells/cm2 per well. Cells were treated with staurosporine as previously described and 200 × 106 exosomes were added per well in 300 µl S-5 medium. For galectin 1–blocking experiments, 200 × 106 exosomes were preincubated with either 0.5 µg/ml of anti-galectin 1 antibody or 0.5 µg/ml of anti-rabbit control IgG in 300 µl S-5 medium for 30 min on ice and subsequently added to apoptotic SH-SY5Y cells. Cells treated with control IgG only or anti-galectin 1 antibody only served as controls. Cells were incubated for 120 h at 37°C, 5% CO2, imaged, and analyzed as previously described for indirect coculture.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as means ± sd. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 7 software (Graphpad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA), and differences were considered significant if P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Induction of apoptosis in SH-SY5Y cells

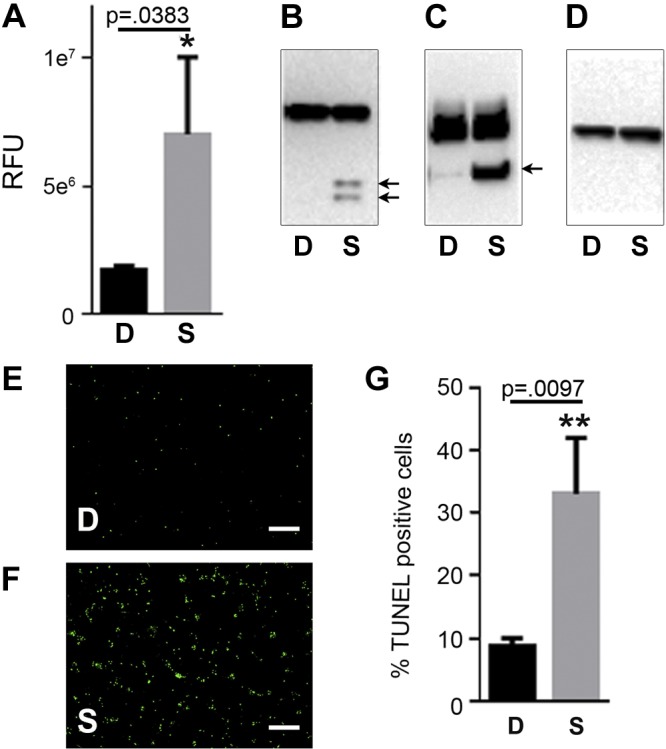

To test the neuroprotective effect of PMSCs, we developed an apoptotic injury model using the SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell line, a commonly used cell line by researchers in the field of neurobiology (37–39). Staurosporine has been widely used as an apoptotic inducer by inhibiting a broad spectrum of protein kinases. The classic markers of apoptosis are an increase in caspase-3 activity that leads to cleavage of its substrate PARP-1, ultimately leading to fragmentation of DNA that can be assessed by TUNEL staining. Treating SH-SY5Y cells with 1 µM staurosporine for 4 h showed a significant increase in caspase-3 activity compared with DMSO-treated controls (Fig. 1A). Apoptotic activity was further confirmed by Western blotting of caspase-3 protein and PARP-1, showing increased expression of their cleaved active products at 17 kDa/12 kDa and 89 kDa, respectively (Fig. 1B, C), in the presence of staurosporine compared with DMSO control. GAPDH was the endogenous protein loading control (Fig. 1D). TUNEL staining of SH-SY5Y cells showed a significant increase in the percentage of TUNEL-positive apoptotic cells in the presence of staurosporine compared with DMSO control (Fig. 1E–G). Together, these results confirmed the effect of staurosporine on SH-SY5Y cells and confirmed that this could be used to test the neuroprotective function of PMSCs.

Figure 1.

Cytotoxicity assay. A–D) SH-SY5Y cells treated with staurosporine (S) or DMSO (D) were assessed by caspase activity RFU (A), Western blotting of lysates probed with caspase-3 antibody (B), PARP-1 antibody (C), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH)-loading control (D). Arrows indicate the processed products only in the presence of staurosporine. E, F) Representative fluorescence images of TUNEL staining in the presence of DMSO (E) and staurosporine (F). G) Significant increase in the number of TUNEL-positive cells normalized to total cells stained using DAPI was observed in the presence of staurosporine (n = 3). Scale bars, 200 µm. RFU, relative fluorescence units.

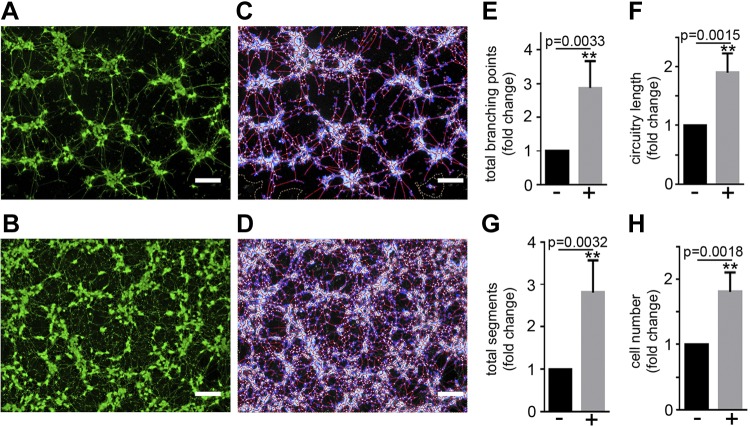

Indirect coculture of PMSCs and apoptotic SH-SY5Y cells

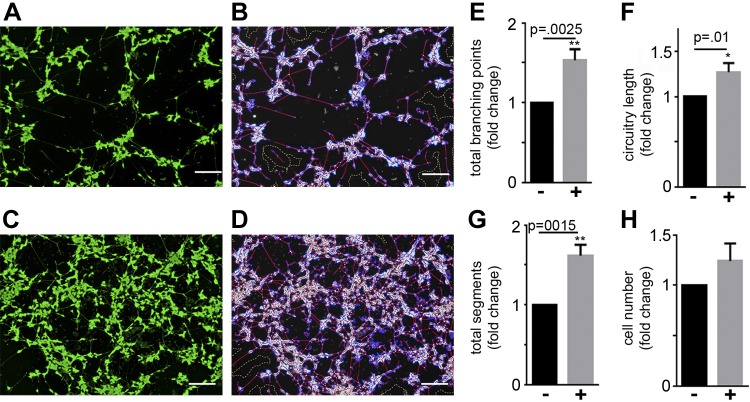

PMSCs have been reported to impart their regenerative function on other cells by a paracrine mechanism. To test the neuroprotective function of PMSCs, we used an indirect coculture system where PMSCs at 300,000 cells/cm2 were seeded onto the coculture inserts and placed onto apoptotic SH-SY5Y cells. Inserts with no PMSCs seeded served as controls. After 96 h of incubation, calcein AM staining of live cells (Fig. 2A, B), as well as subsequent WimNeuron software analysis that captured all the neurites (Fig. 2C, D), showed a significant increase in the total number of branching points (Fig. 2E), circuitry length (Fig. 2F), and tube length (Fig. 2G) in the presence of PMSCs compared with controls without PMSCs seeded on the inserts. There was also a significant increase in the number of cells in the presence of PMSCs compared with controls (Fig. 2H).

Figure 2.

Neuroprotective effect of PMSCs by indirect coculture. SH-SY5Y cells were subjected to staurosporine treatment and cocultured with PMSCs seeded onto hanging cell culture inserts. A–D) Calcein AM staining and Wimasis image analysis in the absence (A, C) and presence (B, D) of PMSCs show increased neurite outgrowth in the presence of PMSCs. E–H) WimNeuron image analysis showed a significant fold increase in total branching points (E), circuitry length (px) (F), and total segments (px) (G), and a significant increase in cell number (H) in the presence of PMSCs compared with controls (n = 4 donor cell banks and repeated 3 times). Scale bars, 200 µm.

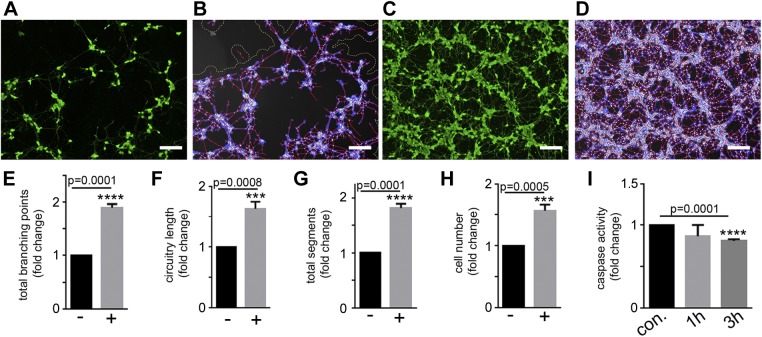

Effect of conditioned medium of PMSCs on apoptotic SH-SY5Y cells

To further confirm the paracrine effect of PMSCs, conditioned medium containing the complete secretome of PMSCs was collected and added onto apoptotic SH-SY5Y cells. After 72-h incubation with conditioned medium, calcein AM staining of live cells (Fig. 3A, B) and WimNeuron analysis (Fig. 3C, D) showed the same pronounced effect on the total number of branch points (Fig. 3E), circuitry length (Fig. 3F), tube length (Fig. 3G), and number of cells (Fig. 3H) compared with controls, as observed during indirect coculture previously described. To test if this increase was due to the neuroprotective function of PMSCs, caspase activity was measured at 1 and 3 h after stopping the staurosporine treatment in the presence and absence of PMSC-conditioned medium. A significant decrease in caspase activity was observed in the presence of PMSC-conditioned medium compared with its medium-only control at the 3-h time point (Fig. 3I), suggesting that PMSCs impart a neuroprotective function on SH-SY5Y by decreasing the progression and reversing apoptosis (anastasis).

Figure 3.

Neuroprotective effect of conditioned medium collected from PMSCs. SH-SY5Y cells were subjected to staurosporine treatment and cultured with conditioned medium from PMSCs. A–D) Calcein AM staining and Wimasis image analysis in the absence (A, B) and presence (C, D) of conditioned medium show increased neurite outgrowth in the presence of conditioned medium. E–H) WimNeuron image analysis showed a significant increase in total branching points (E), circuitry length (px) (F), and total segments (px) (G), and a significant fold increase in cell number (H) in the presence of conditioned medium compared with its control (n = 3). Scale bars, 200 µm. I) Caspase activity 1 and 3 h after cessation of staurosporine treatment showed a significant suppression at a 3-h time point in the presence of conditioned medium compared with the control (con.) Experiment was performed using conditioned medium obtained from 2 different donor cell banks and repeated 4 times.

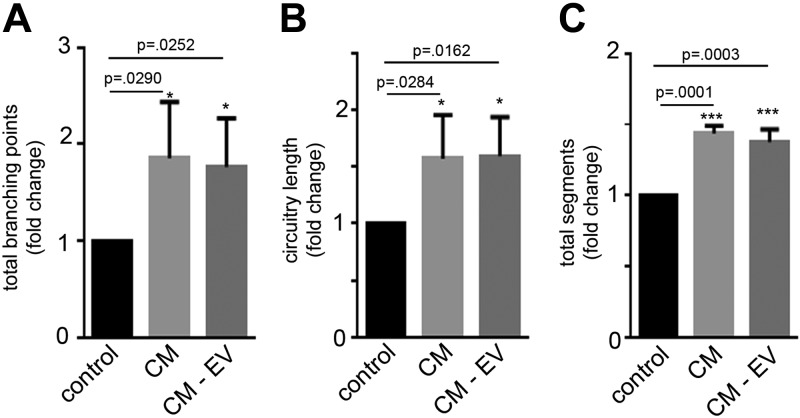

Effect of EV-depleted conditioned medium of PMSCs on apoptotic SH-SY5Y cells

To study the neuroprotective effects of PMSC exosomes, complete conditioned medium and EV-depleted conditioned medium secreted by PMSCs were tested on apoptotic SH-SY5Y cells. Calcein AM imaging and subsequent WimNeuron analysis showed a significant increase in the neurite outgrowth in the presence of both complete and EV-depleted conditioned medium compared with controls (Fig. 4). There was only a marginal decrease in the neurite outgrowth in EV-depleted conditioned medium compared with complete medium. This could be attributed to the fact that the number of secreted exosomes might be very low in number. Therefore, we sought to do a large-scale isolation of exosomes to study their neuroprotective function.

Figure 4.

Effect of EV-depleted conditioned medium (CM-EV) collected from PMSCs. SH-SY5Y cells were subjected to staurosporine treatment and cultured with either complete conditioned medium (CM) or CM-EV from PMSCs. Calcein AM staining and subsequent WimNeuron image analysis showed a significant fold increase in total branching points (A), circuitry length (px) (B), and total segments (px) (C) in the presence of either CM compared with its control. Only a marginal decrease in the total branch points (A) and total segments (C) was observed in the CM-EV compared with complete CM (n = 3 donor cell banks and repeated 3 times).

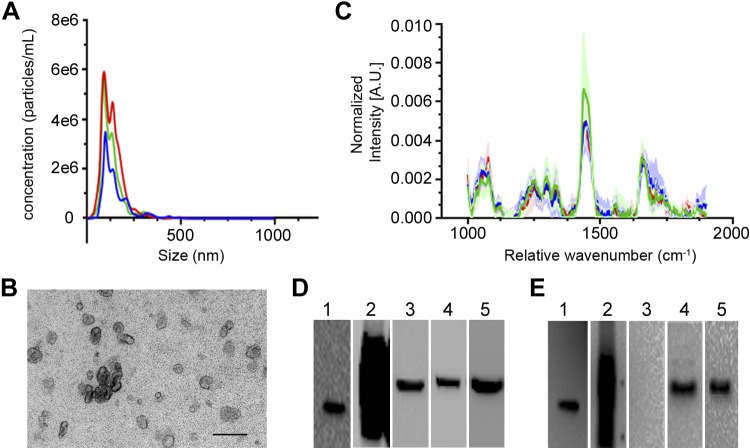

Isolation and characterization of PMSC exosomes

The secretome of PMSCs contains not only free proteins that act as signaling molecules but also EVs, including exosomes. To determine whether exosomes play a role in the signaling pathway involved in the neuroprotective function of PMSCs, we isolated exosomes from the conditioned medium secreted by PMSCs using the standard differential ultracentrifugation method. NTA showed that PMSC exosomes have a size range of 132.3 ± 5.79 nm, which is within the expected size range of exosomes (Fig. 5A). TEM images of the purified exosomes showed the characteristic cup shape and size of exosomes (Fig. 5B). LTRS is a relatively new method that has been used to characterize the composition of optically trapped EVs, including their component proteins, lipids, nucleic acids, sterols, and carbohydrates (29, 30). Importantly, Raman spectroscopy combined with optical trapping enables the measurement of a single vesicle at a time. Fig. 5C illustrates the average ± sd. Raman spectra for exosomes isolated by ultracentrifugation from each of the 3 donors. Each peak in the Raman spectra corresponds to biologic group assignments, including proteins and amino acids at 840, 882, 1000, 1240–1280, 1455, and 1680 cm−1; lipids at 1265, 1300, 1445, 1656 cm−1; cholesterol at 1150, 1440, 1680 cm−1; and nucleic acids at 898, 1095, 1128, 1420, 1490, 1580 cm−1, as previously described (29, 30). PMSC exosomes isolated from 3 donor cell banks have similar spectra, with major peaks corresponding to the presence of proteins, lipids, and cholesterol (Fig. 5C). This indicates that no major chemical differences (i.e., differences between classes of biomolecules present across exosomes) were apparent between the donors. Western blotting analysis confirmed the presence of typical exosome markers CD9 (Fig. 5E, lane 1), CD63 (Fig. 5E, lane 2), TSG101 (Fig. 5E, lane 4), and ALIX (Fig. 5E, lane 5) and the absence of endoplasmic reticulum marker calnexin (Fig. 5E, lane 3) compared to cell lysates, respectively (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

Characterization of PMSC-derived exosomes. Exosomes were isolated from the conditioned medium of PMSCs and subjected to differential ultracentrifugation. A) NTA tracings of average values of 2 different preparations of each of the 3 donor cell banks (3 line tracings with different colors representing 3 cell banks) showed a strong peak that is within the expected size range of exosomes. B) Representative TEM imaging showed typical cup-shaped structures of exosomes. Scale bar, 500 nm. C–E) LTRS analysis tracings of average values ± sd of 10 exosomes from 3 donor cell banks (3 line tracings with different colors representing 3 cell banks) showed similar profile of composition (C), and Western blot analysis of PMSC lysates (D) and exosomes (E) of CD9 (lane1), CD63 (lane2), calnexin (lane 3), ALIX (lane 4), and TSG101 (lane5) (n = 3 donor cell banks).

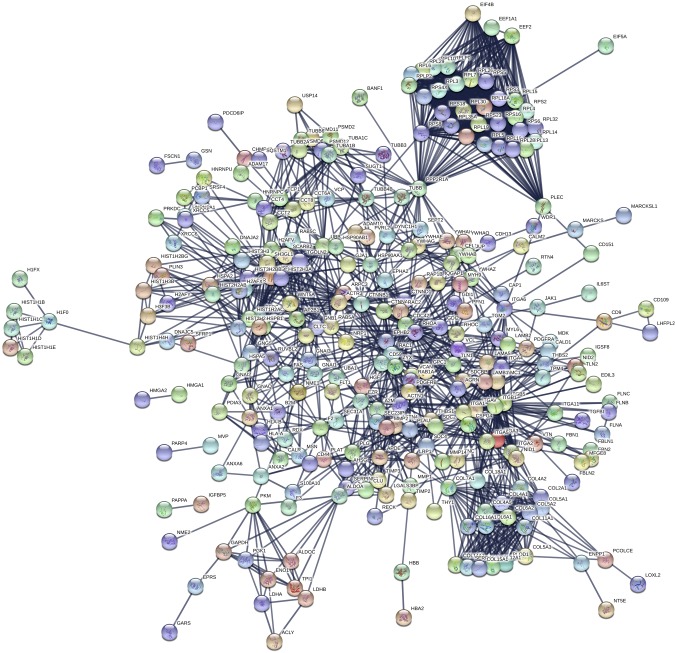

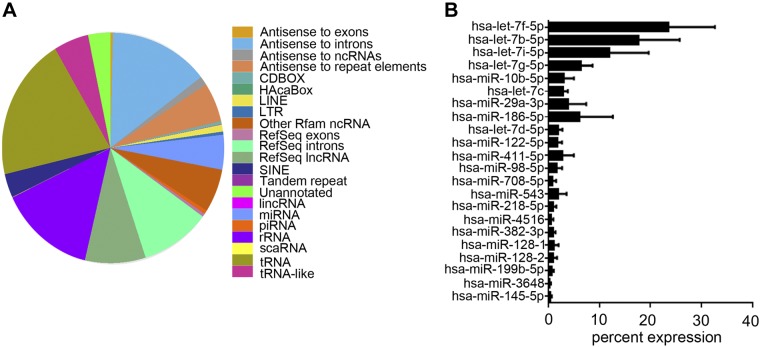

The composition of PMSC exosomes was further characterized by proteomics and NGS of RNAs. Proteomics by tandem mass spectrometry was analyzed by cluster analysis using Scaffold software, which identified ∼452 proteins in 399 clusters that are key signaling molecules (Table 1 and complete data set in Supplemental Table S1). BSA and keratin proteins (a contamination in our samples) were removed from the data set before analysis. Protein clusters were then assessed for their involvement in biologic processes using the STRING database for biologic process, cellular component, molecular function, and KEGG pathways (Table 2, complete data set in Supplemental Table S2). Similar data were obtained using DAVID database (unpublished results). Proteins identified were predominantly present in the EV and exosome components with strong binding activity function via integrins and growth factors. The pathways that were identified with very low false discovery rates were focal adhesion, extracellular matrix receptor interaction, PI3K-Akt, Rap1, and axon guidance. Ras, MAPK, and chemokine signaling pathways were also identified, but with a higher error rate. Network analysis using STRING database is depicted in Fig. 6, and the nodes are shown in Supplemental Table S3. Proteomics data did not pick up any bovine proteins except for BSA, showing that the exosome preparations solely consisted of human exosomes. Extensive washing of exosome pellets with PBS helped in the elimination of BSA, aiding in the tandem mass spectrometry analysis. NGS analyses identified the presence of several types of RNAs in exosomes (Fig. 7A), and for the scope of this manuscript only, the miRNAs (Supplemental Table S4) identified were further analyzed. Individual miRNAs that are > ∼0.5% of the total miRNA are shown in Fig. 7B. GO analysis for miRNAs using miRpath DIANA (34) involved in negative regulation of neuron apoptosis, positive regulation of neurogenesis, and axon guidance picked several miRNAs that are present in the PMSC exosomes (Table 3). Pathway analysis of the miRNAs using the miRNet database specifically for exosomal miRNA annotation and target genes identified key KEGG pathways involved in neuronal survival and neurogenesis (Table 4 and Supplemental Table S5).

TABLE 1.

Proteins identified by proteomics in exosomes and their function

| Protein function | Protein |

|---|---|

| Extracellular matrix | Collagen, fibronectin, vitronectin, heparan sulfate glycans, laminin, glypican-1 |

| Histones | H1, H2A, H3, H4 |

| Heat shock proteins | 70, 71, 90, β 1 |

| Histocompatibility antigen class 1 | A, B, and C |

| Annexins | A1, A2, A4, A5, A6, A7 |

| Matrix metalloproteases/inhibitors | MMP1, MMP2, MMP14, ADAM9, ADAM10, ADAM17, TIMP-2, TIMP-3 |

| Integrins | α1, α2, α3, α4, α5, α6, α8, α11, αv, β1, β3, β5 |

| Cytoskeletal proteins | Actin, actinin, tubulin, ephrin |

| Signaling molecules | HGF, galectin 1, α-catenin, β-catenin, platelet-derived growth factor, TGF-β, Wnt5a, tissue factor |

ADAM, a disintegrin and metalloprotease; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; TIMP, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase.

TABLE 2.

Pathways identified by STRING pathway database for cellular component, molecular function, biologic process, and KEGG pathways

| Pathway ID | Pathway description | Observed gene count | False discovery rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cellular component | |||

| GO.1903561 | EV | 265 | 5.62E−137 |

| GO.0070062 | Extracellular exosome | 264 | 1.41E−136 |

| GO.0044421 | Extracellular region part | 285 | 5.15E−129 |

| GO.0031988 | Membrane-bounded vesicle | 265 | 9.20E−115 |

| GO.0031982 | Vesicle | 267 | 1.20E−113 |

| GO.0005576 | Extracellular region | 289 | 2.49E−113 |

| GO.0005925 | Focal adhesion | 107 | 9.12E−97 |

| GO.0030055 | Cell-substrate junction | 106 | 3.17E−94 |

| GO.0005912 | Adherens junction | 103 | 8.32E−84 |

| GO.0030054 | Cell junction | 110 | 4.06E−49 |

| GO.0005615 | Extracellular space | 98 | 2.55E−33 |

| GO.0044420 | Extracellular matrix component | 36 | 1.66E−31 |

| GO.0031012 | Extracellular matrix | 54 | 1.69E−30 |

| GO.0005829 | Cytosol | 149 | 6.83E−28 |

| GO.0031410 | Cytoplasmic vesicle | 84 | 1.34E−27 |

| GO.0016023 | Cytoplasmic membrane-bounded vesicle | 80 | 2.18E−27 |

| GO.0009986 | Cell surface | 65 | 1.33E−25 |

| GO.0005578 | Proteinaceous extracellular matrix | 46 | 1.37E−24 |

| Molecular function | |||

| GO.0005515 | Protein binding | 220 | 1.95E−48 |

| GO.0005198 | Structural molecule activity | 67 | 7.65E−31 |

| GO.0032403 | Protein complex binding | 65 | 7.65E−31 |

| GO.0044822 | Poly(A) RNA binding | 90 | 1.16E−28 |

| GO.0003723 | RNA binding | 101 | 4.22E−27 |

| GO.0050839 | Cell adhesion molecule (CAM) binding | 33 | 5.05E−25 |

| GO.0044877 | Macromolecular complex binding | 80 | 1.68E−24 |

| GO.0005488 | Binding | 288 | 1.76E−23 |

| GO.0005201 | Extracellular matrix structural constituent | 22 | 2.23E−19 |

| GO.0005102 | Receptor binding | 69 | 7.40E−17 |

| GO.0005178 | Integrin binding | 21 | 1.53E−16 |

| GO.0019838 | Growth factor binding | 22 | 3.14E−16 |

| GO.0097367 | Carbohydrate derivative binding | 100 | 3.27E−15 |

| GO.0019899 | Enzyme binding | 70 | 2.95E−13 |

| GO.0005518 | Collagen binding | 15 | 4.22E−13 |

| GO.0048407 | Platelet-derived growth factor binding | 9 | 4.99E−12 |

| GO.0042802 | Identical protein binding | 52 | 5.96E−10 |

| GO.1901363 | Heterocyclic compound binding | 160 | 3.21E−09 |

| GO.0043168 | Anion binding | 97 | 3.41E−09 |

| Biologic process | |||

| GO.0030198 | Extracellular matrix organization | 74 | 3.79E−52 |

| GO.0022411 | Cellular component disassembly | 77 | 3.63E−44 |

| GO.0071822 | Protein complex subunit organization | 108 | 4.86E−36 |

| GO.0009611 | Response to wounding | 81 | 5.31E−36 |

| GO.0042060 | Wound healing | 77 | 1.67E−35 |

| GO.0016043 | Cellular component organization | 198 | 1.78E−35 |

| GO.0022617 | Extracellular matrix disassembly | 39 | 2.99E−35 |

| GO.0007155 | Cell adhesion | 77 | 2.96E−26 |

| GO.0022008 | Neurogenesis | 92 | 6.81E−26 |

| GO.0007399 | Nervous system development | 108 | 1.77E−24 |

| GO.0007411 | Axon guidance | 49 | 6.32E−24 |

| GO.0061564 | Axon development | 54 | 2.22E−23 |

| GO.0031175 | Neuron projection development | 59 | 5.57E−22 |

| GO.0007409 | Axonogenesis | 51 | 1.04E−21 |

| GO.0048812 | Neuron projection morphogenesis | 53 | 2.82E−21 |

| GO.0048666 | Neuron development | 62 | 4.07E−20 |

| KEGG pathways | |||

| 4510 | Focal adhesion | 52 | 5.60E−41 |

| 4512 | Extracellular matrix receptor interaction | 36 | 3.90E−37 |

| 4151 | PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | 52 | 1.25E−29 |

| 4810 | Regulation of actin cytoskeleton | 31 | 4.99E−17 |

| 4015 | Rap1 signaling pathway | 21 | 9.70E−09 |

| 4520 | Adherens junction | 13 | 1.31E−08 |

| 4540 | Gap junction | 13 | 1.10E−07 |

| 4514 | CAMs | 15 | 8.10E−07 |

| 4530 | Tight junction | 13 | 1.24E−05 |

| 4360 | Axon guidance | 12 | 4.47E−05 |

| 4144 | Endocytosis | 14 | 0.00021 |

| 4390 | Hippo signaling pathway | 11 | 0.00107 |

| 4014 | Ras signaling pathway | 13 | 0.00259 |

| 4010 | MAPK signaling pathway | 14 | 0.00287 |

| 4062 | Chemokine signaling pathway | 9 | 0.0431 |

| 4110 | Cell cycle | 7 | 0.0487 |

Figure 6.

Network analysis of proteins identified in exosomes. Proteins identified by the Scaffold software were subjected to network analysis using the STRING database set at a high confidence interaction score of 0.900. Network nodes represent proteins. Colored nodes represent query proteins and first shell of interactions. Empty nodes represent proteins of unknown 3-dimensional structure. Filled nodes signify that some 3-dimensional structure is known. Edges represent protein-protein associations (proteins jointly contributing to a shared function). Known interactions are generated from curated databases and experimentally determined; predicted interactions are generated from gene neighborhood, gene fusions, and gene co-occurrence; others are generated from text mining, coexpression, and protein homology.

Figure 7.

NGS analysis of PMSC-derived exosomes. Exosomes isolated from 3 donor cell banks were subjected to NGS analysis. A) Representative distribution of all RNAs identified in the exosomes. B) Relative percentage of miRNAs that is greater than ∼0.5% of the total miRNAs identified.

TABLE 3.

miRNAs involved in negative regulation of neuronal apoptosis, positive regulation of neurogenesis and axon guidance

| miRNA | Error rate |

|---|---|

| Negative regulation of neuronal apoptosis: GO:0043524 | |

| hsa-let-7b-5p | 3.66E−29 |

| hsa-miR-29a-3p | 5.96E−21 |

| hsa-miR-145-5p | 2.2E−19 |

| hsa-let-7g-5p | 7.62E−18 |

| hsa-let-7d-5p | 2.47E−16 |

| hsa-let-7f-5p | 2.47E−16 |

| hsa-let-7i-5p | 2.47E−16 |

| hsa-miR-218-5p | 2.47E−16 |

| hsa-miR-30b-5p | 2.47E−16 |

| hsa-miR-186-5p | 7.41E−15 |

| hsa-miR-19a-3p | 7.41E−15 |

| hsa-miR-122-5p | 2.06E−13 |

| hsa-miR-22-5p | 2.06E−13 |

| hsa-mir-98 | 5.27E−12 |

| hsa-let-7c | 1.23E−10 |

| hsa-miR-224-5p | 1.23E−10 |

| hsa-miR-128 | 2.61E−09 |

| hsa-miR-138-5p | 4.95E−08 |

| hsa-miR-10b-5p | 1.22E−05 |

| hsa-miR-374b-5p | 0.001618 |

| hsa-let-7a-3p | 0.01365 |

| hsa-miR-342-3p | 0.01365 |

| hsa-miR-411-5p | 0.01365 |

| hsa-mir-412 | 0.01365 |

| Positive regulation of neurogenesis: GO:0050769 | |

| hsa-miR-10b-5p | 4.22E−09 |

| hsa-let-7c | 9.74E−07 |

| hsa-let-7a-3p | 0.018314 |

| hsa-let-7f-5p | 0.018314 |

| hsa-let-7g-5p | 0.018314 |

| hsa-miR-138-5p | 0.018314 |

| hsa-miR-218-5p | 0.018314 |

| hsa-miR-22-5p | 0.018314 |

| Axon guidance: GO:0007411 | |

| hsa-miR-218-5p | 4.2E−51 |

| hsa-let-7b-5p | 3.87E−48 |

| hsa-let-7f-5p | 1.13E−46 |

| hsa-miR-122-5p | 1.13E−46 |

| hsa-let-7g-5p | 9.03E−44 |

| hsa-let-7i-5p | 9.03E−44 |

| hsa-miR-22-5p | 1.02E−36 |

| hsa-miR-186-5p | 5.53E−34 |

| hsa-let-7d-5p | 5.56E−30 |

| hsa-miR-19a-3p | 5.56E−30 |

| hsa-mir-98 | 5.56E−30 |

| hsa-let-7c | 1.12E−28 |

| hsa-miR-29a-3p | 1.12E−28 |

| hsa-miR-128 | 4.15E−26 |

| hsa-miR-145-5p | 7.57E−25 |

| hsa-miR-30b-5p | 7.57E−25 |

| hsa-miR-374b-5p | 1.65E−16 |

| hsa-miR-224-5p | 3.56E−11 |

| hsa-miR-10b-5p | 2.75E−08 |

| hsa-miR-342-3p | 2.75E−08 |

| hsa-miR-138-5p | 2.18E−07 |

| hsa-mir-412 | 2.18E−07 |

| hsa-let-7a-3p | 1.6E−06 |

| hsa-miR-199a-5p | 1.07E−05 |

| hsa-miR-708-5p | 6.56E−05 |

| hsa-miR-505-3p | 0.001778 |

| hsa-miR-99a-5p | 0.001778 |

| hsa-mir-495 | 0.028834 |

| hsa-mir-206 | 0.028834 |

TABLE 4.

Key signaling pathways identified being regulated by PMSC exosome miRNAs

| Pathway | No. of genes | P |

|---|---|---|

| ErbB signaling pathway | 59 | 2.18E−07 |

| Neurotrophin signaling pathway | 77 | 2.70E−07 |

| Focal adhesion | 111 | 2.29E−06 |

| TGF-β signaling pathway | 55 | 2.75E−06 |

| Regulation of actin cytoskeleton | 101 | 6.87E−06 |

| Adherens junction | 45 | 4.86E−05 |

| Axon guidance | 67 | 1.37E−04 |

| Wnt signaling pathway | 78 | 2.73E−04 |

| T cell receptor signaling pathway | 56 | 4.76E−04 |

| mTOR signaling pathway | 30 | 5.47E−04 |

| Jak-STAT signaling pathway | 54 | 2.53E−03 |

| MAPK signaling pathway | 124 | 5.91E−03 |

| Apoptosis | 45 | 7.41E−03 |

| Notch signaling pathway | 26 | 3.75E−02 |

Jak-STAT, Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin.

Neuroprotective function of exosomes

To study the neuroprotective function of PMSC exosomes, isolated PMSC exosomes were added directly to the apoptotic SH-SY5Y cells. Calcein AM imaging (Fig. 8A, B) and WimNeuron analysis (Fig. 8C, D) showed a significant increase in the total number of branch points (Fig. 8E), circuitry length (Fig. 8F), tube length (Fig. 8G), and increase in cell number (Fig. 8H). This showed that as part of the secretome, in addition to free-signaling molecules, PMSC exosomes play a role in the paracrine neuroprotective function of PMSCs.

Figure 8.

Neuroprotective effect of PMSC-derived exosomes. SH-SY5Y cells were subjected to staurosporine treatment and then cultured with exosomes isolated from the conditioned medium of PMSCs. A–D) Calcein AM staining and Wimasis image analysis in the absence (A, B) and presence (C, D) of exosomes show increased neurite outgrowth in the presence of exosomes. E–H) WimNeuron image analysis showed a significant increase in total branching points (E), circuitry length (F), and total segments (G), and an increase in cell number (H) in the presence of exosomes compared with its control (n = 3 donor cell banks and repeated 3 times). Scale bars, 200 µm.

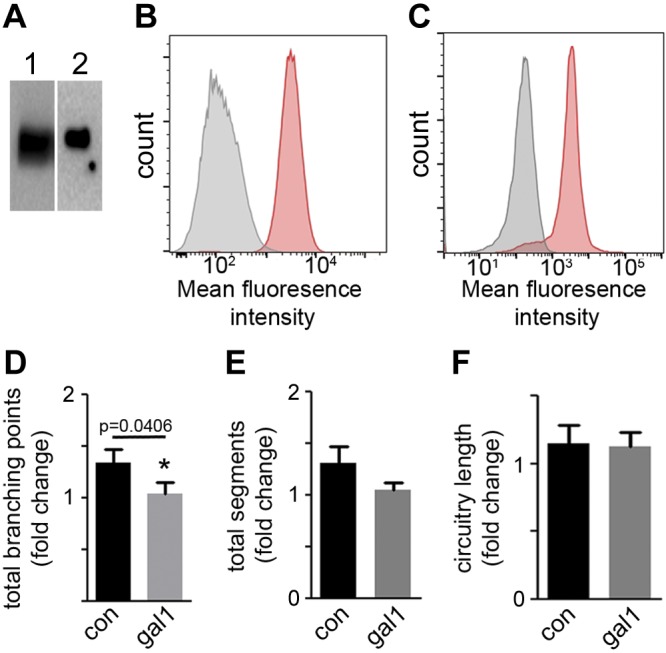

Role of galectin 1 in neuroprotective function of PMSC exosomes

Galectin 1, a molecule with both neuroprotective and immunomodulatory functions, was identified in PMSC exosomes by proteomic analysis (Supplemental Table S1). This expression was further confirmed by Western blotting of cell lysates and exosomes (Fig. 9A, lanes 1 and 2, respectively). Flow cytometry analysis demonstrated the expression of galectin 1 on the surface of both PMSCs and PMSC exosomes (Fig. 9B, C, respectively). In the neuroprotection assay, blocking experiments by preincubation of PMSC exosomes with anti–galectin 1 antibody led to a decrease in the total number of branching points (Fig. 9D, P = 0.0406) and total neurite segments (Fig. 9E, P = 0.0706) when compared with preincubation with control IgG, but did not have significant effect on the circuitry length (Fig. 9F, P = 0.8501). This result suggests that binding of galectin 1 present on the surface of the exosomes to the apoptotic SH-SY5Y cells is partially responsible for the neuroprotective effect imparted by PMSC exosomes.

Figure 9.

Expression and role of galectin 1 on the neuroprotective effect of PMSC exosomes. A) Expression of galectin 1 in PMSCs (lane 1) and PMSC exosomes (lane 2) by Western blot analysis. B, C) Flow cytometry analysis shows expression of galectin 1 on the surface of PMSCs (B) and PMSC exosomes (C) (IgG control in grey and anti-galectin 1 in red). SH-SY5Y cells were subjected to staurosporine treatment and then cultured with exosomes preincubated with either control IgG (con) or anti-galectin 1 antibody (gal1). D–F) Calcein AM staining and subsequent Wimasis image analysis showed a significant decrease in total branching points (D), a decrease in total segments (E), and no change in circuitry length (F) (n = 3 donor cell banks).

DISCUSSION

Over several years, the field of regenerative medicine has fully utilized the therapeutic potential of MSCs for treatment of a wide range of clinical disorders. Despite several reports of differentiation potential to various cell lineages in vitro and in vivo, their regenerative potential is predominantly executed by the trophic factors secreted by MSCs via a paracrine mechanism (1). MSCs can be isolated from various sources, and our lab has primarily focused on PMSCs isolated from discarded early-gestation chorionic villus tissue and its application for treatment of myelomeningocele (16, 23, 24, 27). We have shown that a large number of PMSCs can be obtained from a single donor and that they secrete high amounts of neurotrophic factors such as BDNF, HGF, and VEGF (19). In utero transplantation of PMSCs in the ovine SB model has shown pronounced recovery of hind limb motor function, and this effect was confirmed by decreasing the number of apoptotic cells at the site of injury in the retinoic acid–induced rat SB model (23, 24, 27). To further elucidate the paracrine function of PMSCs, we developed an in vitro apoptotic model and studied their paracrine neuroprotective function.

Cell survival by active inhibition of apoptosis can be accomplished by inhibiting the expression of proapoptotic factors and by up-regulating the expression of antiapoptotic factors. We have demonstrated that PMSCs have paracrine function, and their secretome has a profound effect on the recovery of apoptotic cells, both by indirect coculture studies and by conditioned medium secreted by PMSCs. In the neuroprotection assay, PMSCs not only increased the number of neurites but also increased overall cell number. This increase in cell number could be by increased proliferation of cells that survived the staurosporine treatment or by recovering the cells that are undergoing apoptosis from complete damage. One of the key pathways that promotes apoptosis is the increase of caspase-3 activity. We show here that the addition of conditioned medium to apoptotic cells decreased caspase-3 activity, suggesting that this pathway could be one of the ways that PMSCs impart their neuroprotective function. Further evaluation regarding whether this function is through inhibition of apoptosis in cells that have not started the apoptotic process or through anastasis (40) is needed, as well as an in-depth analysis of other key signaling players that are involved in this process. In order to correlate to in vivo function, unlike the neuroblastoma cell line used in this study, such studies will involve the use of available human neural progenitor cell lines and the influence of PMSCs on pathologic conditions, such as oxidative stress.

Previously, we have shown that PMSCs secrete several growth factors and cytokines involved in neuronal survival (16, 19). In addition to free proteins, secreted EVs also play a role in cell communication. Of the several types of EVs secreted by the cells, exosomes are small nanovesicles ranging from 50 to 150 nm in size, generated through a stringently regulated endocytic pathway and containing several proteins and RNAs. The removal of EVs from the conditioned medium showed only a slight decrease in effect on neurite outgrowth, but purified exosomes had a very significant neuroprotective effect. This finding could be due to the fact that MSCs inherently do not secrete a large number of exosomes (41), in addition to the overwhelming effect of high levels of trophic factors still remaining in the EV-depleted conditioned medium. To elucidate the paracrine function of PMSCs through exosomes, we performed large-scale purification of exosomes from PMSC-conditioned medium. NTA showed a distinct bimodal distribution of size range present in all 3 donor samples tested. It is now well-known that exosomes isolated from various cell types are a mixture of subpopulations, with each one having a role in the regulation of a specific biologic process (42). Because of the low yield of exosomes secreted by PMSCs, we have limited this study to the characterization of exosomes obtained after differential ultracentrifugation and 1 dosage for neuroprotection studies. Future studies will involve ways to increase the secretion of exosomes by using dynamic 3-dimensional bioreactors, such as hollow fiber scaffolds, instead of the 2-dimensional static culture method used here and to obtain highly purified subpopulations of exosomes by iodixanol density gradient flotation following differential ultracentrifugation (43). By identifying subtypes of exosomes and performing dose-dependent studies using neural progenitor cell lines, we may be able to focus their effects on specific cell signaling pathways for future exosome-based therapeutic applications. Nevertheless, to stringently control for variability in the secretion, we used the same passage number of cells from all the 3 donors, performed the isolation of PMSCs at the same time (for proteomics and NGS analysis), and used the same cell density, volume of culture medium, and time point of collection of conditioned medium.

In this study, we have identified several key proteins and miRNAs present in exosomes that could play a role in neuronal survival, neurogenesis, and axon guidance. The proteins identified were clustered into EV and exosome components. Galectin 1, a β-galactoside–binding protein with a wide spectrum of biologic function, was identified by proteomics, and we have demonstrated here that it is highly expressed on the surface of not only PMSCs but also PMSC exosomes. Considering the unconventional secretory pathway of galectins (44) and the presence of galectin 1 on the surface of the PMSC plasma membrane, it is highly possible that the galectin 1 found on the PMSC exosomes originates from the cell surface. Galectin 1 has been demonstrated to regulate cell adhesion, axonal regeneration, and proliferation of neural stem cells (45–47). Our blocking experiments show that galectin 1 is possibly involved in the adhesion of exosomes to cells, thus aiding in the neuroprotective function of PMSC exosomes. Whether it is solely an adhesion function of galectin 1 or whether it activates additional downstream signaling pathways warrants further investigation.

Two of the key signal transduction KEGG pathways identified were the focal adhesion and PI3-Akt pathways that play a role in cell proliferation and neuronal survival with focal adhesion pathway via integrins and Akt through inhibition of proapoptotic signals (48, 49). miRNAs are short (20–24 nt) noncoding RNAs involved in the post-translational regulation of gene expression and modulate cellular processes. Each miRNA can target several genes, thus affecting various biologic functions. To relate our study to the role of PMSCs on injured apoptotic neurons, we used GO for functional annotation of miRNAs and found several miRNAs identified in PMSC-derived exosomes involved in the negative regulation of neuronal apoptosis pathway, positive regulation of neurogenesis, and axon guidance. For example, miRNA let-7b-5p that is present at a high percentage has been shown to be involved in suppressing apoptosis of MSCs by targeting caspase-3 signaling (50). Interestingly, the common KEGG pathway that was identified in both the proteins and the miRNAs was the focal adhesion pathway with a low P value, suggesting that, with respect to PMSCs, it might play a key role in its function. We have mentioned only a few references relating to the mechanism of neuronal survival and development by exosomes. Considering all of the proteins and RNAs present in these exosomes, it will not be an overstatement to suggest that a uniform population of exosomes, if obtained, can act therapeutically for neurologic disorders.

One of the major drawbacks of cell-based therapy is the recipient’s rejection of transplanted donor cells, as with any other organ transplantation. There are several reports characterizing the secretome of MSCs and its use in cell-free therapy clinical applications (51–53). We have limited this study to the neuroprotective function of PMSCs, but considering the wide array of signaling molecules and exosomes present in the secretome of PMSCs, they could very well impart several other biologic functions. This opens up a possibility for cell-free therapeutic application of the PMSC secretome by using exosomes either alone or in combination with trophic factors, not only for spinal cord injury but also for other neurologic disorders.

Supplementary Material

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported, in part, by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (PC1-08103 to D.L.F. and A.W.), Craig H. Neilsen Foundation Research Grant 546558 (to D.L.F.), Shriners Hospital for Children Research Grants 85120-NCA-16 (to D.L.F.), 87410-NCA-17 and 85119-NCA-18 (to A.W.), U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant 5R01NS100761-02 (to A.W.), NIH Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant R03HD091601-01 (to A.W.), March of Dimes Foundation Grant 5FY1682 (to A.W.), a University of California–Davis Center for Biophotonics Pilot grant (to A.W.), and California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM) Training Grant TG2-01163 (to B.A.K.). The authors acknowledge Nicole Kreutzberg (University of California–Davis) for her help with manuscript editing and submission. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- EV

extracellular vesicle

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GO

gene ontology

- HGF

hepatocyte growth factor

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- LTRS

laser trapping Raman spectroscopy

- miRNA

microRNA

- MSC

mesenchymal stromal cell

- NGS

next-generation RNA sequencing

- NTA

nanoparticle tracking analysis

- PARP-1

poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1

- PMSC

placenta-derived MSC

- SB

spina bifida

- STRING

Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

P. Kumar drafted the manuscript; P. Kumar, J. C. Becker, K. Gao, R. P. Carney, and K. Herout acquired the data; P. Kumar, J. C. Becker, R. P. Carney, L. Lankford, B. A. Keller, K. S. Lam, and A. Wang provided critical revision; P. Kumar, R. P. Carney, and A. Wang analyzed and interpreted the data; and P. Kumar, D. L. Farmer, and A. Wang conceptualized and designed the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Liang X., Ding Y., Zhang Y., Tse H. F., Lian Q. (2014) Paracrine mechanisms of mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy: current status and perspectives. Cell Transplant. 23, 1045–1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szekiova E., Slovinska L., Blasko J., Plsikova J., Cizkova D. (2018) The neuroprotective effect of rat adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cell-conditioned medium on cortical neurons using an in vitro model of SCI inflammation. Neurol. Res. 40, 258–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beretti F., Zavatti M., Casciaro F., Comitini G., Franchi F., Barbieri V., La Sala G. B., Maraldi T. (2018) Amniotic fluid stem cell exosomes: therapeutic perspective. Biofactors 44, 158–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He X. T., Li X., Yin Y., Wu R. X., Xu X. Y., Chen F. M. (2018) The effects of conditioned media generated by polarized macrophages on the cellular behaviours of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. J. Cell Mol. Med. 22, 1302–1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krämer-Albers E. M., Hill A. F. (2016) Extracellular vesicles: interneural shuttles of complex messages. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 39, 101–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Niel G., D’Angelo G., Raposo G. (2018) Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 213–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shabbir A., Cox A., Rodriguez-Menocal L., Salgado M., Van Badiavas E. (2015) Mesenchymal stem cell exosomes induce proliferation and migration of normal and chronic wound fibroblasts, and enhance angiogenesis in vitro. Stem Cells Dev. 24, 1635–1647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson J. D., Johansson H. J., Graham C. S., Vesterlund M., Pham M. T., Bramlett C. S., Montgomery E. N., Mellema M. S., Bardini R. L., Contreras Z., Hoon M., Bauer G., Fink K. D., Fury B., Hendrix K. J., Chedin F., El-Andaloussi S., Hwang B., Mulligan M. S., Lehtiö J., Nolta J. A. (2016) Comprehensive proteomic analysis of mesenchymal stem cell exosomes reveals modulation of angiogenesis via nuclear factor-kappaB signaling. Stem Cells 34, 601–613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doeppner T. R., Herz J., Görgens A., Schlechter J., Ludwig A. K., Radtke S., de Miroschedji K., Horn P. A., Giebel B., Hermann D. M. (2015) Extracellular vesicles improve post-stroke neuroregeneration and prevent postischemic immunosuppression. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 4, 1131–1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mead B., Tomarev S. (2017) Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes promote survival of retinal ganglion cells through miRNA-dependent mechanisms. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 6, 1273–1285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bjørge I. M., Kim S. Y., Mano J. F., Kalionis B., Chrzanowski W. (2017) Extracellular vesicles, exosomes and shedding vesicles in regenerative medicine - a new paradigm for tissue repair. Biomater. Sci. 6, 60–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lamichhane T. N., Sokic S., Schardt J. S., Raiker R. S., Lin J. W., Jay S. M. (2015) Emerging roles for extracellular vesicles in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 21, 45–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keshtkar S., Azarpira N., Ghahremani M. H. (2018) Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles: novel frontiers in regenerative medicine. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 9, 63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brady K., Dickinson S. C., Guillot P. V., Polak J., Blom A. W., Kafienah W., Hollander A. P. (2014) Human fetal and adult bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells use different signaling pathways for the initiation of chondrogenesis. Stem Cells Dev. 23, 541–554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Coppi P., Bartsch G., Jr., Siddiqui M. M., Xu T., Santos C. C., Perin L., Mostoslavsky G., Serre A. C., Snyder E. Y., Yoo J. J., Furth M. E., Soker S., Atala A. (2007) Isolation of amniotic stem cell lines with potential for therapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 100–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lankford L., Selby T., Becker J., Ryzhuk V., Long C., Farmer D., Wang A. (2015) Early gestation chorionic villi-derived stromal cells for fetal tissue engineering. World J. Stem Cells 7, 195–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Safford K. M., Rice H. E. (2005) Stem cell therapy for neurologic disorders: therapeutic potential of adipose-derived stem cells. Curr. Drug Targets 6, 57–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antoniadou E., David A. L. (2016) Placental stem cells. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 31, 13–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lankford L., Chen Y. J., Saenz Z., Kumar P., Long C., Farmer D., Wang A. (2017) Manufacture and preparation of human placenta-derived mesenchymal stromal cells for local tissue delivery. Cytotherapy 19, 680–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meuli M., Moehrlen U. (2014) Fetal surgery for myelomeningocele is effective: a critical look at the whys. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 30, 689–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farmer D. L., Thom E. A., Brock J. W., III, Burrows P. K., Johnson M. P., Howell L. J., Farrell J. A., Gupta N., Adzick N. S.; Management of Myelomeningocele Study Investigators (2018) The management of myelomeningocele study: full cohort 30-month pediatric outcomes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 218, 256.e1–256.e13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adzick N. S., Thom E. A., Spong C. Y., Brock J. W., III, Burrows P. K., Johnson M. P., Howell L. J., Farrell J. A., Dabrowiak M. E., Sutton L. N., Gupta N., Tulipan N. B., D’Alton M. E., Farmer D. L.; MOMS Investigators (2011) A randomized trial of prenatal versus postnatal repair of myelomeningocele. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 993–1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kabagambe S., Keller B., Becker J., Goodman L., Pivetti C., Lankford L., Chung K., Lee C., Chen Y. J., Kumar P., Vanover M., Wang A., Farmer D. (2017) Placental mesenchymal stromal cells seeded on clinical grade extracellular matrix improve ambulation in ovine myelomeningocele. [E-pub ahead of print] J. Pediatr. Surg. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.10.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang A., Brown E. G., Lankford L., Keller B. A., Pivetti C. D., Sitkin N. A., Beattie M. S., Bresnahan J. C., Farmer D. L. (2015) Placental mesenchymal stromal cells rescue ambulation in ovine myelomeningocele. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 4, 659–669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang L., Lin S., Yi D., Huang Y., Wang C., Jin L., Liu J., Zhang Y., Ren A. (2017) Apoptosis, expression of PAX3 and P53, and caspase signal in fetuses with neural tube defects. Birth Defects Res. 109, 1596–1604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H., Miao J., Zhao G., Wu D., Liu B., Wei X., Cao S., Gu H., Zhang Y., Wang L., Fan Y., Yuan Z. (2014) Different expression patterns of growth factors in rat fetuses with spina bifida aperta after in utero mesenchymal stromal cell transplantation. Cytotherapy 16, 319–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Y. J., Chung K., Pivetti C., Lankford L., Kabagambe S. K., Vanover M., Becker J., Lee C., Tsang J., Wang A., Farmer D. L. (2017) Fetal surgical repair with placenta-derived mesenchymal stromal cell engineered patch in a rodent model of myelomeningocele. [E-pub ahead of print] J. Pediatr. Surg. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.10.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Théry C., Amigorena S., Raposo G., Clayton A. (2006) Isolation and characterization of exosomes from cell culture supernatants and biological fluids. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. , Unit 3.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carney R. P., Hazari S., Colquhoun M., Tran D., Hwang B., Mulligan M. S., Bryers J. D., Girda E., Leiserowitz G. S., Smith Z. J., Lam K. S. (2017) Multispectral optical tweezers for biochemical fingerprinting of CD9-positive exosome subpopulations. Anal. Chem. 89, 5357–5363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith Z. J., Lee C., Rojalin T., Carney R. P., Hazari S., Knudson A., Lam K., Saari H., Ibañez E. L., Viitala T., Laaksonen T., Yliperttula M., Wachsmann-Hogiu S. (2015) Single exosome study reveals subpopulations distributed among cell lines with variability related to membrane content. J. Extracell. Vesicles 4, 28533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Szklarczyk D., Morris J. H., Cook H., Kuhn M., Wyder S., Simonovic M., Santos A., Doncheva N. T., Roth A., Bork P., Jensen L. J., von Mering C. (2017) The STRING database in 2017: quality-controlled protein–protein association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D362–D368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang W., Sherman B. T., Lempicki R. A. (2009) Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vlachos I. S., Zagganas K., Paraskevopoulou M. D., Georgakilas G., Karagkouni D., Vergoulis T., Dalamagas T., Hatzigeorgiou A. G. (2015) DIANA-miRPath v3.0: deciphering microRNA function with experimental support. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W460–W466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vlachos I. S., Kostoulas N., Vergoulis T., Georgakilas G., Reczko M., Maragkakis M., Paraskevopoulou M. D., Prionidis K., Dalamagas T., Hatzigeorgiou A. G. (2012) DIANA miRPath v.2.0: investigating the combinatorial effect of microRNAs in pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, W498–W504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fan Y., Siklenka K., Arora S. K., Ribeiro P., Kimmins S., Xia J. (2016) miRNet - dissecting miRNA-target interactions and functional associations through network-based visual analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W135–W141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carney R. P., Hazari S., Rojalin T., Knudson A., Gao T., Tang Y., Liu R., Viitala T., Yliperttula M., Lam K. S. (2017) Targeting tumor-associated exosomes with integrin-binding peptides. Adv. Biosyst. 1, 1600038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Calzarossa C., Bossolasco P., Besana A., Manca M. P., De Grada L., De Coppi P., Giardino D., Silani V., Cova L. (2013) Neurorescue effects and stem properties of chorionic villi and amniotic progenitor cells. Neuroscience 234, 158–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kovalevich J., Langford D. (2013) Considerations for the use of SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells in neurobiology. Methods Mol. Biol. 1078, 9–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lopes F. M., Londero G. F., de Medeiros L. M., da Motta L. L., Behr G. A., de Oliveira V. A., Ibrahim M., Moreira J. C., Porciúncula L. O., da Rocha J. B., Klamt F. (2012) Evaluation of the neurotoxic/neuroprotective role of organoselenides using differentiated human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cell line challenged with 6-hydroxydopamine. Neurotox. Res. 22, 138–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang H. M., Talbot C. C., Jr, Fung M. C., Tang H. L. (2017) Molecular signature of anastasis for reversal of apoptosis. F1000Res 6, 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phan J., Kumar P., Hao D., Gao K., Farmer D., Wang A. (2018) Engineering mesenchymal stem cells to improve their exosome efficacy and yield for cell-free therapy. J. Extracell Vesicles 7, 1522236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lankford K. L., Arroyo E. J., Nazimek K., Bryniarski K., Askenase P. W., Kocsis J. D. (2018) Intravenously delivered mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes target M2-type macrophages in the injured spinal cord. PLoS One 13, e0190358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Colao I. L., Corteling R., Bracewell D., Wall I. (2018) Manufacturing exosomes: a promising therapeutic platform. Trends Mol. Med. 24, 242–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Popa S. J., Stewart S. E., Moreau K. (2018) Unconventional secretion of annexins and galectins. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 83, 42–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sakaguchi M., Shingo T., Shimazaki T., Okano H. J., Shiwa M., Ishibashi S., Oguro H., Ninomiya M., Kadoya T., Horie H., Shibuya A., Mizusawa H., Poirier F., Nakauchi H., Sawamoto K., Okano H. (2006) A carbohydrate-binding protein, Galectin-1, promotes proliferation of adult neural stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 7112–7117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horie H., Inagaki Y., Sohma Y., Nozawa R., Okawa K., Hasegawa M., Muramatsu N., Kawano H., Horie M., Koyama H., Sakai I., Takeshita K., Kowada Y., Takano M., Kadoya T. (1999) Galectin-1 regulates initial axonal growth in peripheral nerves after axotomy. J. Neurosci. 19, 9964–9974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Camby I., Le Mercier M., Lefranc F., Kiss R. (2006) Galectin-1: a small protein with major functions. Glycobiology 16, 137R–157R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahn J. Y. (2014) Neuroprotection signaling of nuclear akt in neuronal cells. Exp. Neurobiol. 23, 200–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peng X., Guan J. L. (2011) Focal adhesion kinase: from in vitro studies to functional analyses in vivo. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 12, 52–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ham O., Lee S. Y., Lee C. Y., Park J. H., Lee J., Seo H. H., Cha M. J., Choi E., Kim S., Hwang K. C. (2015) let-7b suppresses apoptosis and autophagy of human mesenchymal stem cells transplanted into ischemia/reperfusion injured heart 7by targeting caspase-3. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 6, 147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wagenaar N., de Theije C. G. M., de Vries L. S., Groenendaal F., Benders M. J. N. L., Nijboer C. H. A. (2018) Promoting neuroregeneration after perinatal arterial ischemic stroke: neurotrophic factors and mesenchymal stem cells. Pediatr. Res. 83, 372–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fais S., O’Driscoll L., Borras F. E., Buzas E., Camussi G., Cappello F., Carvalho J., Cordeiro da Silva A., Del Portillo H., El Andaloussi S., Ficko Trček T., Furlan R., Hendrix A., Gursel I., Kralj-Iglic V., Kaeffer B., Kosanovic M., Lekka M. E., Lipps G., Logozzi M., Marcilla A., Sammar M., Llorente A., Nazarenko I., Oliveira C., Pocsfalvi G., Rajendran L., Raposo G., Rohde E., Siljander P., van Niel G., Vasconcelos M. H., Yáñez-Mó M., Yliperttula M. L., Zarovni N., Zavec A. B., Giebel B.; Evidence-Based Clinical Use of Nanoscale Extracellular Vesicles in Nanomedicine (2016) Evidence-based clinical use of nanoscale extracellular vesicles in nanomedicine. ACS Nano 10, 3886–3899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Willis G. R., Kourembanas S., Mitsialis S. A. (2017) Therapeutic applications of extracellular vesicles: perspectives from newborn medicine. Methods Mol. Biol. 1660, 409–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.