Abstract

Background

Stroke is a major cause of long‐term disability in adults. Several systematic reviews have shown that a higher intensity of training can lead to better functional outcomes after stroke. Currently, the resources in inpatient settings are not always sufficient and innovative methods are necessary to meet these recommendations without increasing healthcare costs. A resource efficient method to augment intensity of training could be to involve caregivers in exercise training. A caregiver‐mediated exercise programme has the potential to improve outcomes in terms of body function, activities, and participation in people with stroke. In addition, caregivers are more actively involved in the rehabilitation process, which may increase feelings of empowerment with reduced levels of caregiver burden and could facilitate the transition from rehabilitation facility (in hospital, rehabilitation centre, or nursing home) to home setting. As a consequence, length of stay might be reduced and early supported discharge could be enhanced.

Objectives

To determine if caregiver‐mediated exercises (CME) improve functional ability and health‐related quality of life in people with stroke, and to determine the effect on caregiver burden.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register (October 2015), CENTRAL (the Cochrane Library, 2015, Issue 10), MEDLINE (1946 to October 2015), Embase (1980 to December 2015), CINAHL (1982 to December 2015), SPORTDiscus (1985 to December 2015), three additional databases (two in October 2015, one in December 2015), and six additional trial registers (October 2015). We also screened reference lists of relevant publications and contacted authors in the field.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials comparing CME to usual care, no intervention, or another intervention as long as it was not caregiver‐mediated, aimed at improving motor function in people who have had a stroke.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected trials. One review author extracted data, and assessed quality and risk of bias, and a second review author cross‐checked these data and assessed quality. We determined the quality of the evidence using GRADE. The small number of included studies limited the pre‐planned analyses.

Main results

We included nine trials about CME, of which six trials with 333 patient‐caregiver couples were included in the meta‐analysis. The small number of studies, participants, and a variety of outcome measures rendered summarising and combining of data in meta‐analysis difficult. In addition, in some studies, CME was the only intervention (CME‐core), whereas in other studies, caregivers provided another, existing intervention, such as constraint‐induced movement therapy. For trials in the latter category, it was difficult to separate the effects of CME from the effects of the other intervention.

We found no significant effect of CME on basic ADL when pooling all trial data post intervention (4 studies; standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.21, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.02 to 0.44; P = 0.07; moderate‐quality evidence) or at follow‐up (2 studies; mean difference (MD) 2.69, 95% CI ‐8.18 to 13.55; P = 0.63; low‐quality evidence). In addition, we found no significant effects of CME on extended ADL at post intervention (two studies; SMD 0.07, 95% CI ‐0.21 to 0.35; P = 0.64; low‐quality evidence) or at follow‐up (2 studies; SMD 0.11, 95% CI ‐0.17 to 0.39; P = 0.45; low‐quality evidence).

Caregiver burden did not increase at the end of the intervention (2 studies; SMD ‐0.04, 95% CI ‐0.45 to 0.37; P = 0.86; moderate‐quality evidence) or at follow‐up (1 study; MD 0.60, 95% CI ‐0.71 to 1.91; P = 0.37; very low‐quality evidence).

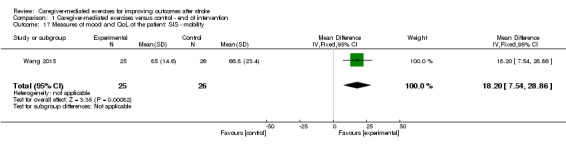

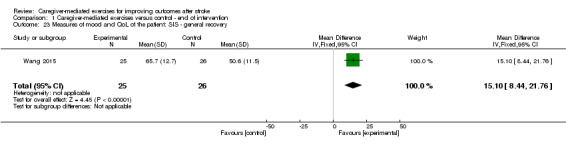

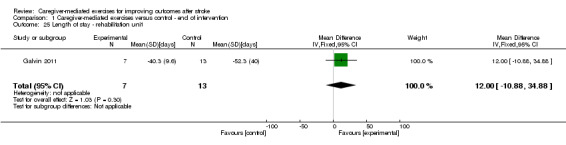

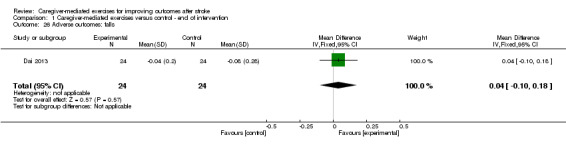

At the end of intervention, CME significantly improved the secondary outcomes of standing balance (3 studies; SMD 0.53, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.87; P = 0.002; low‐quality evidence) and quality of life (1 study; physical functioning: MD 12.40, 95% CI 1.67 to 23.13; P = 0.02; mobility: MD 18.20, 95% CI 7.54 to 28.86; P = 0.0008; general recovery: MD 15.10, 95% CI 8.44 to 21.76; P < 0.00001; very low‐quality evidence). At follow‐up, we found a significant effect in favour of CME for Six‐Minute Walking Test distance (1 study; MD 109.50 m, 95% CI 17.12 to 201.88; P = 0.02; very low‐quality evidence). We also found a significant effect in favour of the control group at the end of intervention, regarding performance time on the Wolf Motor Function test (2 studies; MD ‐1.72, 95% CI ‐2.23 to ‐1.21; P < 0.00001; low‐quality evidence). We found no significant effects for the other secondary outcomes (i.e. patient: motor impairment, upper limb function, mood, fatigue, length of stay and adverse events; caregiver: mood and quality of life).

In contrast to the primary analysis, sensitivity analysis of CME‐core showed a significant effect of CME on basic ADL post intervention (2 studies; MD 9.45, 95% CI 2.11 to 16.78; P = 0.01; moderate‐quality evidence).

The methodological quality of the included trials and variability in interventions (e.g. content, timing, and duration), affected the validity and generalisability of these observed results.

Authors' conclusions

There is very low‐ to moderate‐quality evidence that CME may be a valuable intervention to augment the pallet of therapeutic options for stroke rehabilitation. Included studies were small, heterogeneous, and some trials had an unclear or high risk of bias. Future high‐quality research should determine whether CME interventions are (cost‐)effective.

Plain language summary

Caregiver‐mediated exercises for improving outcomes after stroke

Review question

What is the effect of performing exercises with a caregiver after stroke on outcome for people with stroke and burden for caregivers?

Background

Stroke is a major cause of acquired adult disability. Research has shown that more time spent on exercise therapy in the first weeks to months after stroke leads to better functioning. Due to lack of personnel and resources, in practice it is difficult to spend more time on exercise therapy in this period. One method to increase this exercise time, is to involve caregivers in performing exercise training together with a person with stroke. During this exercise training a therapist coaches patient and caregiver and an evaluation is planned on a regular basis.

Study characteristics

We identified nine clinical trials to October 2015, which all investigated some form of caregiver‐mediated exercises compared with usual care, no treatment (intervention), or another intervention that was not caregiver‐mediated.

Key results

We included 333 patient‐caregiver couples in the review. We found trials in which caregiver‐mediated exercises themselves were the studied subject (called CME‐core). In addition, we found trials in which the caregiver was the provider of another, already existing intervention. In the latter category, it was difficult to separate the effect of caregiver‐mediated exercises from the effect of the other intervention.

We found evidence that caregiver‐mediated exercises could have a positive effect on patients' standing balance (low‐quality evidence) and quality of life (very low‐quality evidence) directly after the intervention. In the long term, we found very low‐quality evidence for a positive effect on walking distance. For speed of use of the arm and hand, we found low‐quality evidence in favour of the control group.

We found no significant side effects or beneficial effects on caregiver strain; we judged the quality of this evidence as moderate (after intervention) to very low (long term). Furthermore, we found no significant effects for basic activities of daily living, such as dressing and bathing, after intervention (moderate‐quality evidence) or follow‐up (low‐quality evidence). In addition, we found no significant effects for extended activities of daily living, such as cooking and gardening, after intervention or at follow‐up (both low‐quality evidence).

In the CME‐core analysis, we found moderate‐quality evidence for a positive effect of caregiver‐mediated exercises for basic activities of daily living.

It can be concluded that caregiver‐mediated exercises may be a promising form of therapy to add to usual care.

Quality of the evidence

The number of included trials was small and the level of evidence was of very low to moderate quality. Therefore, results should be interpreted with caution.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Caregiver‐mediated exercises compared with control intervention for people with stroke.

| Caregiver‐mediated exercises compared with control intervention for people with stroke | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with stroke Settings: inpatient and outpatient settings Intervention: caregiver‐mediated exercises Comparison: control, i.e. usual care, other intervention, no intervention | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control intervention | Caregiver‐mediated intervention | |||||

|

Patient: ADL measures Barthel Index. Scale 0 to 100 (follow‐up: 2 studies; 3/6 months) FIM. Scale 7 to 126 (no follow‐up) |

The mean Barthel Index score ranged across control groups from 78 to 84 1 study: The mean FIM score in the control group was 65 |

The mean Barthel Index score in the intervention groups was

5.09 higher (‐2.88 to 13.07 higher) 1 study: The mean FIM score in the intervention group was 11 higher (‐1.59 to 23.67 higher) |

‐ | Barthel Index: 247

(3) FIM: 48 (1) Total: 295 |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate | Higher scores are better More than half of the studies at low risk of bias (3 low risk of bias, 1 at unclear risk of bias) There was clinical heterogeneity SMD 0.21 (‐0.02 to 0.44) |

|

Caregiver: measures of mood, burden and QoL: burden Caregiver Strain Index Scale. 0 to 13 (follow‐up 3 months) Caregiver Burden Scale. 22 to 88 (no follow‐up) |

The mean Caregiver Strain Index score in the control group was

3.4 The mean Caregiver Burden Scale score in the control group was 46.6 |

The mean Caregiver Strain Index score in the intervention group was 0.50 higher (‐0.81 to 1.81 higher) The mean Caregiver Burden Scale score in the intervention group was 1.30 lower (‐4.88 to 7.48 lower) |

‐ | Caregiver Strain Index: 40 (1) Caregiver Burden Scale: 51 (1) Total: 91 |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate | Lower scores are better Both studies at low risk of bias Small total number of participants SMD ‐0.04 (‐0.45 to 0.37) |

|

Gait and gait‐related measures: walking speed in m/s (follow‐up: 1 study, 9 months) |

The mean walking speed ranged across control groups from 0.26 m/s to 0.46 m/s | The mean walking speed in the intervention group was 0.08 m/s higher (‐0.03 to 0.18) | ‐ | 71 (2) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low | |

|

Gait and gait‐related measures: walking distance measured with the Six‐Minute Walk Test in metres walked in 6 minutes (follow‐up: 1 study, 3 months) |

The mean distance walked ranged across control groups from 157 m to 166 m | The mean distance walked in the intervention groups was 30.98 m higher (‐20.22 to 82.19 higher) | ‐ | 91 (2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate | Lower scores are better 1 study at unclear risk of bias Small total number of participants MD 0.04 (‐0.10 to 0.18) |

|

Measures of mood and QoL of the patient: Stroke Impact Scale Stroke Impact Scale mobility scale. Scale 9 to 45. (no follow‐up) |

The mean Stroke Impact Scale mobility score in the control group was 66.8 | The mean Stroke Impact Scale mobility score in the intervention group was 18.2 higher (7.54 to 28.86 higher) | ‐ | 51 (1) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low | Higher scores are better 1 study at low risk of bias Small total number of participants MD 18.2 (7.54 to 28.86) |

|

Length of stay: length of stay in rehabilitation unit in days |

The mean length of stay in a rehabilitation unit in the control group was 52.3 days | The mean length of stay in a rehabilitation unit in the intervention group was 12 days lower (‐10.88 to 34.88) | ‐ | 20 (1) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low | Higher scores are better 1 study at low risk of bias and 1 at unclear or high risk of bias Small total number of participants There was clinical heterogeneity MD 0.08 m/s (‐0.03 to 0.18) |

|

Adverse outcomes: falls number of falls/patient (no follow‐up) |

1 study: the mean number of falls/patient in the control group was 0.08 | 1 study: the mean number of falls/ patient in the intervention group was 0.04 lower (‐0.10 to 0.18 lower) | ‐ | 48 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low | Higher scores are better Both studies at low risk of bias Small total number of participants MD 30.98 m (‐20.22 to 82.19) |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ADL: activities of daily living; CI: confidence interval; FIM: Functional Independence Measure; MD: mean difference; QoL: quality of life; RR: risk ratio; SD: standard deviation; SMD: standardised mean difference. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

Background

Description of the condition

Stroke is a major cause of long‐term disability in adults with effects on activities of daily living (ADL) and quality of life (QoL). Although most people leave the rehabilitation setting with some level of independent walking, many have residual walking disabilities and it has been reported that following rehabilitation, only 7% of stroke survivors can walk at a level commensurate with community participation (Ada 2009). Twelve months after stroke about 28% of people with stroke remain dependent in their basic ADLs, such as dressing, toileting, and indoor mobility (Ullberg 2015). Pettersen and colleagues reported that 32% of people with stroke living at home after three years were inactive in extended ADL (Pettersen 2002). Any treatment that improves functional outcome can potentially reduce the burden of this illness for the person, their caregivers, and society.

Description of the intervention

Several systematic reviews have shown that a higher intensity of training in terms of time spent on exercise therapy can lead to better functional outcome in people with stroke in terms of ADL and functional performance (French 2010; Galvin 2008a; Kwakkel 2004; Kwakkel 2006; Langhorne 2011; Lohse 2014; Veerbeek 2011; Veerbeek 2014). One resource‐efficient method to increase intensity of training could be to involve caregivers in exercise training (De Weerdt 2002). We define caregiver‐mediated exercises (CME) as the person with stroke performing exercises together with a caregiver under the auspices of a physical or occupational therapist. "Under the auspices" means that the therapist is involved as a coach by instructing both patient and caregiver on how to perform the exercises, and evaluating them on a regular basis. Hereby, the exercises are aimed at improving ADL including mobility, such as making transfers, standing, and walking.

How the intervention might work

Performing exercises together with a caregiver has the potential to augment the intensity of practice without increasing healthcare costs. This could improve outcomes in terms of body functions, activities, and participation as well as cost effectiveness in people with stroke.

In addition, caregivers are more actively involved in CME than in the usually applied rehabilitation services, which may increase feelings of empowerment with reduced levels of caregiver burden (Brereton 2002; Smith 2004a). CME could lead to a reduced length of inpatient stay or outpatient treatment in hospitals, rehabilitation, and nursing settings, and may improve outcomes in self‐management, empowerment, and QoL of patients and caregivers.

Why it is important to do this review

Several systematic reviews have indicated that additional exercise therapy and repetitive task training have a significant, favourable effect on functional outcome after stroke, and concluded that the more time spent on exercise therapy (Galvin 2008a; Kwakkel 2004; Kwakkel 2006; Lohse 2014; Veerbeek 2011), and the higher the number of repetitions, the better the outcome (French 2010; Langhorne 2011; Veerbeek 2014). Therefore, clinical guidelines recommend that people who are in a rehabilitation setting should have the opportunity to train intensively (ESO 2008; NICE 2013; SIGN 2010; Veerbeek 2014). For example, the stroke guideline in the UK recommends a daily dose of 45 minutes of exercise therapy (NICE 2013).

Currently, the resources in inpatient settings are not sufficient to meet these recommendations. Most people admitted to stroke units, rehabilitation wards, and nursing homes spend most of their waking time during the working week inactive (Bernhardt 2004; Smith 2008; West 2012), and on weekends, rehabilitation services (including exercise therapy) in most hospital and rehabilitation settings are not available (Otterman 2012). Therefore, it is important to find innovative methods, such as CME, to enhance intensity of training after stroke, without increasing costs.

However, the caregiver taking the role of a therapist (instead of a family role) may burden the caregiver with yet another task (Gordon 2004). Therefore, it is important to study the mood, burden, and QoL of caregivers when involving them in CME systematically. No systematic review has yet been conducted to evaluate the effect of caregiver participation in exercise training on functional outcome after stroke, or to evaluate the effect on mood and burden of the caregiver when involved in CME.

Objectives

To determine if caregiver‐mediated exercises (CME) improve functional ability and health‐related quality of life in people with stroke, and to determine the effect on caregiver burden.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including cluster‐RCTs. One group of the trial must have received CME and we considered this group as the experimental group for this review. The other (control) group could have received usual treatment, no treatment, or any other type of rehabilitation intervention or attention‐control as long as it was not caregiver‐mediated. We accepted usual treatment when it was described as usual care in the setting of the participant.

Types of participants

People, at least 18 years old, who had had a stroke. Stroke is defined by the World Health Organization as "a clinical syndrome typified by rapidly developing signs of focal or global disturbance of cerebral functions, lasting more than 24 hours or leading to death, with no apparent causes other than of vascular origin" (WHO 1989). We included RCTs regardless of timing after stroke and setting.

Types of interventions

One group of the RCT must have included CME, whereas the caregiver involvement was not explicitly asked for in the other group of the RCT. We included trials in which the patient and their caregiver were trained or instructed together, as well as trials in which the caregiver was trained or instructed alone. There was no limit to the number of sessions or to the frequency of delivery. We included all types of exercises as long as they were aimed at improving patients' abilities to perform daily activities. Therefore, we excluded RCTs of speech, swallowing, or cognitive interventions done together with a caregiver. We defined a caregiver or carer as an unpaid or partially paid person who voluntarily helped an impaired person with his or her ADL. In other words, the mediated services were not applied by a professional in health care but in most cases, someone who was close to the patient and voluntarily offered his or her services. This may have been a partner, family member, or friend, but it can also have been a volunteer. We argued that this person was 'not a professional' such as a 'therapy assistant'. When a professional in health services applied the mediated exercises, we excluded the RCT. We included interventions delivered at any location, for example at home, in hospital, or in a rehabilitation setting. Because a caregiver can be the provider of an intervention, we did not exclude trials that combined CME with an existing intervention. However, we did differentiate between trials in which CME was the only intervention (CME‐core) and trials in which a caregiver was used to deliver another, existing intervention. We contacted trial authors when it was unclear whether a trial met our definition.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Patient: basic ADL measures, such as the Barthel index (BI) (Collin 1988; Mahoney 1965), Functional Independence Measure (FIM) (Dodds 1993), modified Rankin Scale (mRS) (De Haan 1995; Dromerick 2003); extended ADL measures, such as the Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living (NEADL) Index (Nouri 1987), or Frenchay Activities Index (FAI) (Wade 1985). When found, we combined scales with the same construct.

Caregiver: measures of burden, for example Caregiver Strain Index (CSI) (Robinson 1983). When found, we combined scales with the same construct.

When possible we distinguished between caregivers who were family or friends and other types of caregivers, such as volunteers, for the above‐mentioned measures of outcome.

Secondary outcomes

Measures of motor impairment: Motricity Index (MI) (Collin 1990), Fugl‐Meyer Assessment (FMA) (Duncan 1983; Sanford 1993; Shelton 2001).

Gait and gait‐related measures: walking speed, walking distance, Timed‐Up‐and‐Go test (TUG) (Collen 1990; Flansbjer 2005), Rivermead Mobility Index (RMI) (Collen 1991; Hsieh 2000; Hsueh 2003), Berg Balance Scale (BBS) (Berg 1992; Berg 1995; Mao 2002; Stevenson 2001).

Measures of upper limb activities or function, for example, Action Research Arm Test (ARAT) (Chen 2012; Hsieh 1998; Platz 2005).

Measures of mood and QoL of the patient, for example, measured by the Stroke Impact Scale (SIS) (Duncan 1999; Duncan 2002; Duncan 2003), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Aben 2002; Bjelland 2002; Herrmann 1997; Zigmond 1983).

Measures of fatigue of the participant, for example, measured by the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) (Valko 2008).

Length of stay in hospital, rehabilitation centre, or nursing home, or treatment in an outpatient clinic.

Adverse outcomes, for example, pain, injury, or falls. When possible, we compared the total number of falls between groups, and the number of patients experiencing at least one fall between groups.

Caregiver: measures of mood and QoL, for example, HADS (Aben 2002; Bjelland 2002; Herrmann 1997; Zigmond 1983), or CarerQoL (Brouwer 2006; Hoefman 2011).

When we found scales measuring the same construct, we combined them. If studies reported outcome measures other than the ones mentioned above, we verified if they measured the same construct. If this was the case, we pooled them; if they did not measure the same construct, we reported these outcomes separately.

Search methods for identification of studies

See the 'Specialized register' section in the Cochrane Stroke Group module. We searched for trials in all languages and arranged translation of papers where necessary. Due to time limitations, we were unable to perform the review within one year after the first search (April 2014). Therefore, it was necessary to update our search in October 2015. We used the same search strategy but due to different availability of Information Specialists and providers of databases, we adjusted the search strategies accordingly: Embase.com instead of Ovid/Embase, and EBSCO/AMED instead of Ovid/AMED. We limited the update searches between 2014 and 2016.

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases and trials registers.

Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register (last searched October 2015).

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (the Cochrane Library, 2015, Issue 10) (Appendix 1).

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) (the Cochrane Library, last searched October 2015) (Appendix 1).

Cochrane Methodology Register (CMR) (the Cochrane Library, last searched October 2015) (Appendix 1).

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (the Cochrane Library, last searched October 2015) (Appendix 1).

Health Technology Assessment Database (HTA) (the Cochrane Library, last searched October 2015) (Appendix 1).

NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) (the Cochrane Library, last searched October 2015) (Appendix 1).

MEDLINE (Ovid) (from 1946 to October 2015) (Appendix 2).

Embase (Ovid from 1980 to April 2014 and Embase.com from 2014 to December 2015) (Appendix 3; Appendix 4).

CINAHL (Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature) (EBSCO) (from 1982 to December 2015) (Appendix 5).

SPORTDiscus (EBSCO) (from 1985 to December 2015) (Appendix 6).

AMED (Alternative and Complementary Medicine) (Ovid from 1985 to April 2014 and EBSCO from 1985 to December 2015) (Appendix 7; Appendix 8).

Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) (from 1929 to October 2015) (www.pedro.org.au/).

REHABDATA (from 1956 to October 2015) (www.naric.com/?q=en/REHABDATA).

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov/).

EU Clinical Trials Register (www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu).

Stroke Trials Registry (www.strokecenter.org/trials/).

Current Controlled Trials (www.controlled‐trials.com).

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/ictrp/en/).

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (www.anzctr.org.au/).

We developed the MEDLINE search strategy with the help of the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator (Brenda Thomas) and adapted this for the other databases. Search strategies for the main databases are included. For a complete overview of the search, see Appendix 9.

Searching other resources

To identify further published, unpublished, and ongoing studies we:

searched the reference lists of all included articles;

contacted experts and authors in the field;

used Science Citation Index Cited Reference Search for forward tracking of important articles.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (JV, MM) independently screened the titles of records obtained from the electronic searches and excluded obviously irrelevant studies. Subsequently, we screened the remaining abstracts and excluded those that were irrelevant. Finally, we obtained the full‐text articles for the remaining studies and the same two review authors selected studies for inclusion in the review based on the inclusion criteria described previously. We resolved any disagreement by discussion and, where necessary, in consultation with a third review author (EvW).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (JV, MM) conducted data extraction and reviewed risk of bias of the eligible trials. The review authors were not blinded to study authors, journals, or outcomes. We resolved any disagreement about risk of bias by discussion. If we could not reach consensus, a third review author (EvW) made the final decision. One review author (JV) extracted data and a second review author (MM) cross‐checked the extracted data using a standard checklist, including randomisation method, study population, intervention methods and delivery, outcome measures, and follow‐up.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We used the tool for assessing risk of bias in included RCTs as described in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We assessed allocation (selection bias), blinding (performance and detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective reporting (reporting bias), and other potential sources of bias, such as management of dropouts (no intention‐to‐treat analysis). We presented the results in 'Risk of bias' tables. We provided our judgement ('low risk', 'high risk' or 'unclear risk') for each entry, followed by a description of the judgement. We made our judgements transparent, and used comments or quotes when necessary.

Measures of treatment effect

We extracted means and standard deviations (SDs) of postintervention scores and follow‐up scores. Where available, we also extracted means and SDs of change from baseline.

For continuous outcomes using similar measurement scales, we used the mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). If similar outcomes were measured on different scales, we used Hedges' g, calculated the 95% CI and standard mean difference (SMD).

We reported the direction of the effect for every scale to align the treatment effects between outcome scales. For scales in which a low score reflected a favourable outcome and a high score an unfavourable outcome, we multiplied scores by ‐1.

We used Review Manager 5 for all quantitative analyses (RevMan 2014).

Unit of analysis issues

We took into account that studies can apply different randomisation methods, for example, at the level of a participant or at the level of a group of participants (cluster randomisation).

In selected studies with multiple intervention groups, we made multiple pair‐wise comparisons between all possible pairs of intervention groups. We made sure that participants were not double‐counted in the analysis.

Dealing with missing data

If data were missing or were not in a form suitable for quantitative pooling, we contacted the trial authors to request additional information.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed the impact of heterogeneity in the meta‐analysis for each outcome with the I2 statistic (Higgins 2011). When there was substantial statistical heterogeneity (I2 greater than 50%) we used a random‐effects model, otherwise we used a fixed‐effect model for meta‐analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

Because we identified fewer than 10 studies, we did not assess reporting bias by a funnel plot in which effect estimates and precision (standard error) of individual RCTs are plotted, as we had planned.

Data synthesis

We performed a meta‐analysis of the comparison CME versus control group (usual care, no intervention, or any other intervention) where there were two or more RCTs with a low risk of bias in which study population, intervention, and outcome measures were the same. We determined the quality of evidence using GRADE levels of evidence.

We included a 'Summary of findings' table using the Cochrane template, and included the following seven outcomes: ADL measures, burden of the caregiver, walking speed, walking distance, mood of the patient, length of stay, and adverse events (falls) (see Table 1). For each outcome, we included the number of participants, the overall quality of the evidence using GRADE levels of evidence, the magnitude of the effect, a measure of burden of the outcome, and comments (Guyatt 2008a; Guyatt 2008b).

In the text and tables, we have systematically described those studies that could not be included in the meta‐analysis. In the same way, we systematically reported other outcome measures that we could not include in a meta‐analysis because they did not measure the same construct as our predefined outcome measures.

We used Review Manager 5 for the analyses (RevMan 2014).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where two or more studies per subgroup were available, we performed subgroup analysis for:

interventions with a higher dose of training in the intervention group than the control group versus interventions with a same dose of training in intervention and control groups;

interventions within six months after stroke and interventions beyond six months after stroke;

interventions aimed at the upper extremity and interventions aimed at the lower extremity.

Sensitivity analysis

A caregiver could be a provider of an existing intervention, for example constraint‐induced movement therapy (CIMT). We included trials investigating this form of CME. However, in these trials, it was difficult to separate the effects of CME from the effects of the intervention. In the other trials, CME itself was considered as the only intervention under study. Therefore, we performed a sensitivity analysis in which only these trials were included (CME‐core). A priori, we did not plan this sensitivity analysis, but decided afterwards to include this analysis in light of the type of studies that we identified. In this sensitivity analysis, we also repeated the subgroup analyses.

Where we applied a fixed‐effect model, we subsequently applied a random‐effects model to assess the robustness of the results to the method used.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies, and Characteristics of ongoing studies tables.

Results of the search

Through electronic searches we found 8107 citations. In addition, one potentially relevant trial was already known to us, but not found through electronic searches (Wall 1987). After removing duplicates, we screened 5640 citations. Based on screening of titles, we excluded 5201 obviously irrelevant studies and screened the remaining 439 abstracts. Subsequently, we excluded 307 studies based on the abstract. Finally, we assessed 132 full‐text articles or trial registry entries for eligibility. After an extensive search, we still could not obtain full‐text articles for four studies ("THE DAYS AFTER"; "Family boosts results of poststroke therapy"; Liu 2012; Wang 2014). We identified 11 relevant systematic reviews, which we screened for trials (Bakas 2014; Brereton 2007; Glasdam 2010; Klinke 2015; Lawler 2013; Legg 2011; Morris 2014; Parke 2015; Pollock 2014a; Pollock 2014b; Warner 2015). In total, we identified 46 potentially relevant trials. The results of the search are summarised in Figure 1. We were able to include nine trials for final analysis (see Characteristics of included studies table), and we included six trials in the meta‐analysis (Abu Tariah 2010; Barzel 2015; Dai 2013; Galvin 2011; Wall 1987; Wang 2015).

1.

Study flow diagram.

We excluded three trials from the meta‐analysis because of poor methodological quality (Agrawal 2013; Gómez 2014) or no reporting of required data (i.e. means or SDs, or both, of outcome measures) (Agrawal 2013; Gómez 2014; Souza 2015), or both. We had no success contacting the corresponding authors to request the necessary data.

We excluded 37 trials, 35 with reasons given in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Two trials are ongoing (see Characteristics of ongoing studies table).

Included studies

Participants

Characteristics

In the nine included studies, 456 stroke survivors and their caregivers were randomised to CME or control interventions. A total of 342 people with stroke‐caregiver couples were included in the six trials included in the meta‐analysis. In these six trials, nine patient‐caregiver couples were not analysed according to intention‐to‐treat principles and no information about these withdrawals was published. Therefore, we have presented information about 333 stroke survivors and their caregivers (ranging from 18 to 156 patient‐caregiver couples per trial) in the meta‐analysis.

The mean age in all studies was around 60 years. The mean time since onset of symptoms ranged from 15 days to 10 years. One trial did not report mean time since onset of symptoms (Gómez 2014).

Three studies defined inclusion or exclusion criteria for the caregiver, for example "willing to participate", "medically stable and physically able" (Galvin 2011), "being defined as primary caregivers" (Dai 2013), and "caregivers were excluded if they were in poor physical health, had mental or behavioural disorders" (Wang 2015).

Four studies described an inclusion criterion for the patient about the caregiver: "live with family caregiver at home" (Abu Tariah 2010), "patients with family support" (Gómez 2014), "had a caregiver who was prepared to be a non‐professional coach (e.g., family member)" (Barzel 2015), and "availability of a family member to supervise home exercises" (Souza 2015). Two studies gave information about the caregiver: "about 50% of the caregivers were nursing attendants" (Dai 2013), and "majority were patients' spouse" (Wang 2015).

Sample size

Five trials included fewer than 50 participants: 20 participants (Abu Tariah 2010; Wall 1987), 24 participants (Souza 2015), 30 participants (Agrawal 2013), and 40 participants (Galvin 2011). Four trials included more than 50 participants: 51 participants (Wang 2015), 55 participants (Dai 2013), 60 participants (Gómez 2014), and 156 participants (Barzel 2015).

Interventions

The content of the training and the timing was different between trials. Details of each intervention are summarised in Table 2.

1. Outline of included studies.

| Study ID | Form of training | Upper or lower body | Timing since stroke | Task caregiver | Routine care continued | Control group | Programme (length ‐frequency‐ duration) | Contact with therapist | Place |

| Abu Tariah 2010 | CIMT | Upper | > 2 months | Carried out the intervention with support of therapists | No | Neurodevelopmental training, same intensity | 2 months ‐ daily ‐ 2 hours | 3 or 4 sessions | Home |

| Agrawal 2013 | Exercise therapy | Upper | "Sub‐acute stroke" | Encouragement, participating, and help | Yes | Usual care | 4 weeks ‐5 days/week ‐ 60 to 90 minutes | Weekly | Inpatient? |

| Barzel 2015 | CIMT | Upper | > 6 months | Supervision, help, and maintaining training diary | No | Usual care, frequency of seeing a therapist was the same | 4 weeks ‐ Every weekday (not weekend) ‐ 2 hours |

5 x 60 minutes | Home |

| Dai 2013 | Vestibular rehabilitation | Both | < 6 months | Guidance and supervision (in third and fourth week) |

Yes | Usual care | 4 weeks ‐ 10 sessions per 2 weeks ‐ 30 minutes | 2 to 4 sessions in first 2 weeks | Inpatient? |

| Galvin 2011 | Exercise therapy | Lower | Assessment 2 weeks after stroke onset | Encouragement and help | Yes | Usual care | 8 weeks ‐every day ‐ 35 minutes | Weekly | Inpatient or at home |

| Gómez 2014 | CIMT | Upper | < 6 months | Monitoring and supervising | Yes | Usual care | 14 days ‐ every day* ‐ 5.5 hours* | 1.5 hours per day* | Inpatient |

| Souza 2015 | CIMT: 1.5 hours with therapist and 1.5 hours with caregiver | Upper | < 24 months** | Supervision and making notes | No | CIMT: 3 hours with therapist | 22 days ‐ 10 sessions ‐ 3 hours | 10 x 90 minutes | Outpatient and home |

| Wall 1987 | Exercise therapy | Lower | After discharge of rehabilitation | Supervision | No | No intervention | 6 months ‐ twice a week ‐ 1 hour | 1 group: twice a week 1 group: once a week 1 group: 'monitoring' |

Outpatient or at home |

| Wang 2015 | Exercise programme aimed at body functions, activities, and participation | Both | > 6 months | Encouragement and help | No | Usual care | 12 weeks ‐ minimal twice a week, if possible every day ‐ minimal 50 to 60 minutes | Weekly 90 minutes | Home |

CIMT: constraint‐induced movement therapy. * Details of the intervention are not completely clear, contact with the authors was not successful. ** But mean time since stroke was 27 and 35 months since stroke, unclear why.

Two trials were aimed at the lower body (Galvin 2011; Wall 1987), five at the upper body (Abu Tariah 2010; Agrawal 2013; Barzel 2015; Gómez 2014; Souza 2015), and two at both upper and lower body (Dai 2013; Wang 2015). Four studies included patients within six months after stroke (Agrawal 2013; Dai 2013; Galvin 2011; Gómez 2014), three studies included patients beyond six months after stroke (Barzel 2015; Wall 1987; Wang 2015), one study included patients from two months after stroke or later (Abu Tariah 2010), one study included patients if they had a stroke in the last 24 months (Souza 2015). The task of the caregiver ranged across trials from supervision, guidance, encouragement, to physical help. In four trials, usual care continued, so CME were applied in addition to usual care (Agrawal 2013; Dai 2013; Galvin 2011; Gómez 2014). The frequency, duration, and programme length differed between studies, with training frequencies ranging from twice a week (Wall 1987; Wang 2015), to every day (Abu Tariah 2010; Galvin 2011), with a duration per session ranging from 30 minutes (Dai 2013), to three hours (Souza 2015), and a programme length ranging from 14 days (Gómez 2014), to six months (Wall 1987). In four trials, patients had weekly contact with the supervising therapist (Agrawal 2013; Barzel 2015; Galvin 2011; Wang 2015). Two trials planned two to four sessions with a therapist (Abu Tariah 2010; Dai 2013). One trial had 10 sessions with a therapist in 22 days (Souza 2015). One trial consisted of four groups, the amount of contact with the therapist differed between trial groups (Wall 1987). The frequency and duration of one trial was not clearly reported (Gómez 2014). Three trials were carried out at home (Abu Tariah 2010; Barzel 2015; Wang 2015), one trial was carried out in an inpatient setting (Gómez 2014), three trials were carried out when patients were inpatient, outpatient, or at home (Galvin 2011; Souza 2015; Wall 1987), and two trials were unclear about the location of the intervention (Agrawal 2013; Dai 2013).

Two trials had more than one trial group. The study by Agrawal 2013, which was not included in meta‐analysis, had two experimental trial groups with different duration of intervention (60 and 90 minutes, five days a week) and one control group. Wall 1987 had two intervention groups (CME, CME plus physiotherapy) and two control groups (physiotherapy, no intervention). We decided to combine the intervention groups and the control groups into one comparison because of the small total number of participants (20).

Compliance

Five studies recorded compliance: "frequency of training and tasks completed was recorded" (Wang 2015), "the amount of training was noted in a diary by patients' families" (Abu Tariah 2010), "compliance with therapy time was documented through the use of an exercise diary, in which the number of exercises completed and time taken to complete the exercises were recorded daily" (Galvin 2011), "a log sheet per participant to record the total number of minutes completed per day" (Agrawal 2013), and "compliance was assessed in all participants via a form (standard therapy group) or a training diary (home CIMT group)" (Barzel 2015). Two trials reported these outcomes in the results. Galvin 2011 reported that 245 minutes of additional exercise therapy was planned for each participant and that a mean of 227 minutes was actually delivered. Barzel 2015 reported a mean exercise time of 27.7 hours within the four‐week intervention. They also noted 12 cases of participants not adhering to the protocol. In Souza 2015, compliance about wearing of the sling was reported in the results, but no information about compliance to the CME was provided. Agrawal 2013 mentioned "inability to monitor patient's compliance with the home exercise programme which might have influenced the study".

Comparisons

Interventions consisted of CME in addition to usual care (Agrawal 2013; Dai 2013; Galvin 2011; Gómez 2014), or instead of usual care (Abu Tariah 2010; Barzel 2015; Souza 2015; Wall 1987; Wang 2015). Two studies included a control intervention (Abu Tariah 2010; Souza 2015), seven included usual care as control (Agrawal 2013; Barzel 2015; Dai 2013; Galvin 2011; Gómez 2014; Wall 1987; Wang 2015), one had no control intervention (Wall 1987). Furthermore, there were different forms of interventions in terms of type of exercise therapy, duration of the intervention, and timing of the intervention.

Outcome measures

All trials reported outcome measures at the end of intervention. Five trials reported outcome measures after three to six months' follow‐up (Abu Tariah 2010; Barzel 2015; Galvin 2011; Souza 2015; Wall 1987). Two trials reported outcome measures during the intervention period (Dai 2013; Wall 1987). Some outcome measures were not reported at baseline, but only at post intervention and at follow‐up. In some instances there were no SDs of outcome measures given, for which we imputed other SDs from the same study when possible (i.e. Galvin 2011: no SD at post intervention for NEADL Index, CSI and Reintegration to Normal Living Index was available and follow‐up SD was used; Abu Tariah 2010: no SD at post intervention or follow‐up for Wolf Motor Function test ‐ performance time was given and SD from baseline was used). Walking speed was reported in different units and were converted to metres/second. Where available, we also extracted mean changes from baseline (Abu Tariah 2010; Barzel 2015; Galvin 2011; Wang 2015), and in those cases where postintervention scores were not available, we used the mean change from baseline. Abu Tariah 2010 and Wang 2015 gave no SDs, but provided CIs. We calculated the SDs for these outcomes using the Z‐score.

One trial reported two outcome measures for extended ADL (Galvin 2011). Based on that, the NEADL Index is developed for people with stroke and widely used in stroke research, we restricted to NEADL Index in the main analysis.

Insufficient information was available regarding the type of caregiver, rendering it impossible to distinguish between caregivers who were family or friends and other (voluntary) caregivers for the different outcome measures. One study mentioned that "about 50% of the caregivers were nursing attendants" (Dai 2013), and one study included four paid workers (Wang 2015). We did not take this professional background into account during the analyses.

The trials used a variety of outcome measures. Some outcome measures were identical, but most differed between trials. We combined outcome measures when they appeared to measure the same construct.

Excluded studies

We excluded 35 articles based on the full texts because they did not meet the inclusion criteria (Adie 2014; Araujo 2015; Barzel 2009; Baskett 1999; Bertilsson 2014; Cameron 2015; Chang 2015; Chinchai 2010; El‐Senousey 2012; Evans 1984; Forster 2013; Goldberg 1997; Grasel 2005; Harrington 2010; Harris 2009; Hebel 2014; Hirano 2012; Jones 2015; Kalra 2004; Koh 2015; Larson 2005; Lin 2004; Maeshima 2003; Marsden 2010; McClellan 2004; Mudzi 2012; NCT00908479; Osawa 2010; Parker 2012; Redzuan 2012; Schure 2006; Shyu 2010; Smith 2004b; Van de Port 2012; Walker 1996). See Characteristics of excluded studies table.

The most common reasons for exclusion were: interventions were educational for patient and caregiver but they performed no, or minimal, exercises together (Chinchai 2010; El‐Senousey 2012; Evans 1984; Forster 2013; Harrington 2010; Larson 2005; Marsden 2010; Mudzi 2012; Parker 2012; Schure 2006; Shyu 2010; Smith 2004a); caregivers were involved and encouraged to participate but caregiver participation was not mandatory (Adie 2014; Baskett 1999; Bertilsson 2014; Harris 2009; Jones 2015; Lin 2004; McClellan 2004; NCT00908479; Van de Port 2012; Walker 1996); and the intervention concerned 'skill training' (Araujo 2015; Chang 2015; El‐Senousey 2012; Forster 2013; Grasel 2005; Hebel 2014; Kalra 2004; Mudzi 2012). Skill training is primarily aimed at training of the caregiver in performing ADL and mobility together with the patient to improve functioning together in the home situation. Skill training is given to the caregiver in a limited number of sessions by a professional, like a therapist or a nurse, but it is not considered progressive training to improve functioning of the patient.

Furthermore, there are some non‐randomised studies about CME (Barzel 2009; Hirano 2012; Maeshima 2003; Osawa 2010). Because of their relevance for the topic of this review they are listed in Characteristics of excluded studies table. However, it is important to note that our search was not aimed at identifying non‐randomised studies and, therefore, we may not be complete in reporting these studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

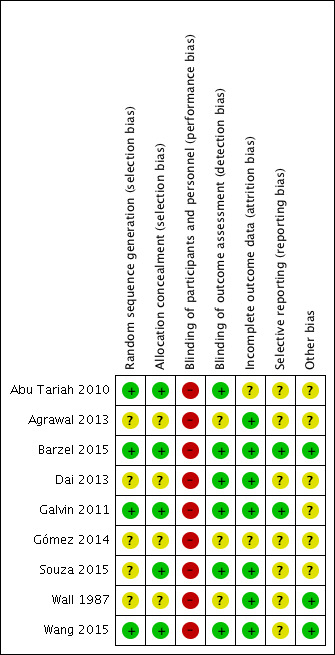

Assessments for 'Risk of bias' in individual studies are shown in the Characteristics of included studies table. See also Figure 2 and Figure 3 for a summary of the results.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

All trials used random allocation to an intervention or control group, of which four adequately described how the randomisation procedure took place and provided sufficient information to determine that the allocation procedure was concealed (Abu Tariah 2010; Barzel 2015; Galvin 2011; Wang 2015). One study was unclear about the randomisation procedure, but did provide sufficient information about allocation procedure (Souza 2015). The other four studies did not describe the randomisation procedure sufficiently (Agrawal 2013; Dai 2013; Gómez 2014; Wall 1987).

Blinding

Participant blinding

Due to the nature of the intervention, participants included in the trials could not be blinded for treatment allocation.

Investigator blinding

Six studies blinded the outcome assessors to treatment allocation (Abu Tariah 2010; Barzel 2015; Dai 2013; Galvin 2011; Souza 2015; Wang 2015). Three studies did not report anything about an outcome assessor (Agrawal 2013; Gómez 2014; Wall 1987). Five studies used participant‐reported outcomes (questionnaires, report of number of falls) (Barzel 2015; Dai 2013; Galvin 2011; Souza 2015; Wang 2015). For these outcomes, the assessor (patient or caregiver) was aware of the treatment allocation. This may have biased the results.

Incomplete outcome data

Three studies had no withdrawals and, therefore, reported complete outcome data (Agrawal 2013; Wall 1987; Wang 2015). Four studies had withdrawals, but reasons were well described and comparable in the intervention and control group (Barzel 2015; Dai 2013; Galvin 2011; Souza 2015). One study reported only withdrawals in the control group (Abu Tariah 2010). Reasons for withdrawal were not documented by the participants, making the risk of bias unclear. One trial did not describe withdrawals, making the risk of bias unclear (Gómez 2014).

Selective reporting

For two included trials (Barzel 2015; Galvin 2011), we identified a trial registry (NCT00666744) and published protocol (Barzel 2013; Galvin 2008b). Galvin 2011 reported no exclusion criteria in the trial paper in contrast to the protocol paper (Galvin 2008b) and trial registration (NCT00666744). Not all outcome measures that were reported in the protocol paper of Barzel 2013 were reported in the trial paper (Barzel 2015), such as the EQ‐5D and healthcare costs. There were an insufficient number of studies (fewer than 10) to reliably examine the effects of risk of bias on estimates of effect and thus we generated no funnel plots.

Other potential sources of bias

Three trials did not perform an intention‐to‐treat analysis. This could be a potential source of bias (Abu Tariah 2010; Dai 2013; Souza 2015). Three trials did not report means or SDs for (a part of) the study outcomes (Agrawal 2013; Galvin 2011; Souza 2015). In one trial, means and SDs for outcome measures were not given, the included outcomes were insufficiently described, and intervention and timing of measurements needed clarification (Gómez 2014). We identified no other potential sources of bias for the remaining trials (Barzel 2015; Wall 1987; Wang 2015).

Grading the quality of the evidence

We determined the quality of the evidence using GRADE levels of evidence. We downgraded effects based on one trial by two levels of evidence and effects based on a small total number of participants (fewer than 200 participants) (BMJ Clinical Evidence 2012) by one level. When half, or more, of the included trials for an outcome measure were of unclear or high risk of bias, we downgraded the level of evidence by one level. When we found substantial unexplained statistical heterogeneity or clinical heterogeneity, we also downgraded the level of evidence by one level. In addition, when we found publication bias, we downgraded the level of evidence by one level.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control (Comparison 1 and 2): primary outcomes

Patient: activities of daily living measures

End of intervention

Three trials assessed the BI (100‐point version) (Barzel 2015; Galvin 2011; Wang 2015). We found no significant summary effect (mean difference (MD) 5.09, 95% CI ‐2.88 to 13.07; P = 0.21; Table 3). One trial used the FIM (Dai 2013). The effect of CME on the FIM was not significant (MD 11.04, 95% CI ‐1.59 to 23.67; P = 0.09; Table 3). Overall, we found no significant summary effect on basic ADL (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.21, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.44; P =0.07; Analysis 1.1). The quality of evidence for effects on basic ADL was moderate; it was downgraded one level due to clinical heterogeneity between studies.

2. (Standard) Mean differences which are not reported in section 'data and analysis'.

| Outcome | Outcome measure | Fixed‐effect or random‐effects model | Mean difference | Confidence interval | Heterogeneity | P value |

| 1.1 Patient: ADL measures ‐ Combined |

1.1.1 Barthel Index | Random‐effects | 5.09 | ‐2.88 to 13.07 | 58% | 0.21 |

| 1.1.2 Functional Independence Measure |

Fixed‐effect | 11.04 | ‐1.59 to 23.67 | ‐ | 0.09 | |

| 1.2 Patient: ADL measures ‐ extended ADL | 1.2.1 Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living Index |

Fixed‐effect | 5.50 | ‐5.83 to 16.83 | ‐ | 0.34 |

| 1.2.2 IADL | Fixed‐effect | 0.02 | ‐0.72 to 0.76 | ‐ | 0.96 | |

| 1.3 Caregiver: burden | 1.3.1 Caregiver Strain Index | Fixed‐effect | ‐0.50 | ‐1.81 to 0.81 | ‐ | 0.46 |

| 1.3.2 Caregiver Burden Scale | Fixed‐effect | 1.30 | ‐4.88 to 7.48 | ‐ | 0.68 | |

| 1.6 Gait and gait‐related measures: balance |

1.6.1 Berg Balance Scale | Fixed‐effect | 6.35 | 1.64 to 11.06 | 0% | 0.008 |

| 1.6.2 Postural Assessment for Stroke patients |

Fixed‐effect | 3.50 | ‐0.52 to 7.52 | ‐ | 0.09 | |

| 2.2 Patient: ADL measures ‐ extended ADL |

2.2.1 Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living Index |

Fixed‐effect | 9.50 | ‐1.83 to 20.83 | ‐ | 0.10 |

| 2.2.2 IADL | Fixed‐effect | 0.02 | ‐0.77 to 0.81 | ‐ | 0.96 | |

| 3.1 Patient: ADL measures ‐ combined | 3.1.1 < 6 months | Fixed‐effect | 0.44* | 0.01 to 0.86 | 0% | 0.04 |

| 3.1.2 > 6 months | Random‐effects | 4.90 | ‐7.56 to 17.36 | 77% | 0.44 | |

| 8.1 Patient ADL measures ‐ extended ADL ‐ end of intervention | 8.1.1 Reintegration to normal living Index | Fixed‐effect | 0.20 | ‐3.76 to 4.16 | ‐ | 0.92 |

| 8.1.2 IADL | Fixed‐effect | 0.02 | ‐0.72 to 0.76 | ‐ | 0.96 | |

| 8.2 Patient ADL measures ‐ extended ADL ‐ end of follow‐up | 8.2.1 Reintegration to normal living Index | Fixed‐effect | 4.50 | 0.54 to 8.46 | ‐ | 0.03 |

| 8.2.2 IADL | Fixed‐effect | 0.02 | ‐0.77 to 0.81 | ‐ | 0.96 |

ADL: activities of daily living; IADL: instrumental activities of daily living.

*Standardised mean difference.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of intervention, Outcome 1 Patient: activities of daily living (ADL) measures: combined.

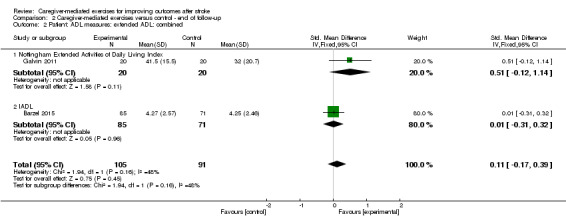

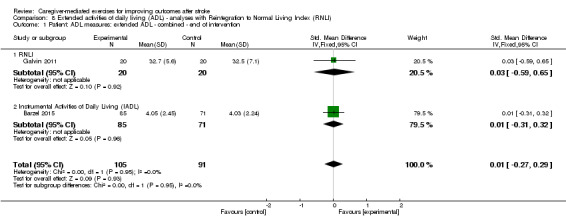

Two trials assessed extended ADL (Barzel 2015; Galvin 2011). We found no significant effects of CME on the NEADL Index (MD 5.50, 95% CI ‐5.83 to 16.83; P = 0.34; Table 3) or on the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) (MD 0.02, 95% CI ‐0.72 to 0.76; P = 0.96; Table 3). Overall, we found no significant summary effect on extended ADL (SMD 0.07, 95% CI ‐0.21 to 0.35; P = 0.64; Analysis 1.2). This effect was based on two trials with low risk of bias, but with clinical heterogeneity between studies and a small total number of participants for this outcome measure, resulting in a low quality of evidence.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of intervention, Outcome 2 Patient: ADL measures: extended ADL: combined.

Follow‐up

Two trials assessed basic ADL and extended ADL at three months' follow‐up (Galvin 2011) and six months' follow‐up (Barzel 2015). We found no significant summary effect of CME on basic ADL (MD 2.69, 95% CI ‐8.18 to 13.55; P = 0.63; Analysis 2.1). This effect was based on two trials with low risk of bias, but with clinical heterogeneity between studies and a small total number of participants for this outcome measure, resulting in a low quality of evidence. The substantial statistical heterogeneity between trials (I2 =69%), can be explained by different timing post stroke (within six months versus beyond six months) and thus there was no reason to downgrade the level of evidence further.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of follow‐up, Outcome 1 Patient: activities of daily living (ADL) measures: ADL.

The effect of CME on extended ADL measured with the NEADL Index (MD 9.50, 95% CI ‐1.83 to 20.83; P = 0.10; Table 3), or measured with the IADL (MD 0.02, 95% CI ‐0.77 to 0.81; P = 0.96; Table 3) was not significant. Overall, there was no significant summary effect of CME on extended ADL (SMD 0.11, 95% CI ‐0.17 to 0.39; P = 0.45; Analysis 2.2). The quality of evidence was low, based on two trials with low risk of bias, but with clinical heterogeneity between studies and a small total number of participants for this outcome measure.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of follow‐up, Outcome 2 Patient: ADL measures: extended ADL: combined.

Caregiver: measures of burden

End of intervention

One trial used the CSI to assess caregiver burden (Galvin 2011); we found no significant effect (MD –0.50, 95% CI ‐1.81 to 0.81; P = 0.46; Table 3). Another trial used the Caregiver Burden Scale (Wang 2015), and again we found no significant effect (MD 1.30, 95% CI ‐4.88 to 7.48; P = 0.68; Table 3). Overall, we found no significant summary effect of CME on caregiver strain (SMD ‐0.04, 95% CI ‐0.45 to 0.37; P = 0.86; Analysis 1.3). These findings were based on two trials with low risk of bias, but with a small total number of participants for this outcome measure, resulting in moderate quality of evidence.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of intervention, Outcome 3 Caregiver: burden: combined.

Follow‐up

One study reported follow‐up of caregiver burden by using the CSI, three months after termination of the intervention (Galvin 2011). We found no significant effect of CME on caregiver strain compared with the control group (MD 0.60, 95% CI ‐0.71 to 1.91; P = 0.37; Analysis 2.3). The quality of the evidence for this finding was very low, since it is based on only one trial with a small number of participants.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of follow‐up, Outcome 3 Caregiver: burden.

Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control (Comparison 1 and 2): secondary outcomes

Measures of motor impairment

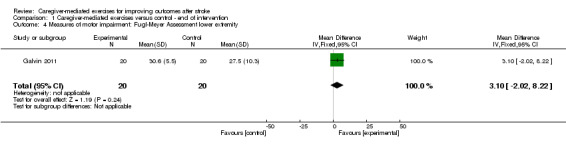

One study assessed the FMA lower extremity score (Galvin 2011). We found no significant effect after the intervention (MD 3.10, 95% CI ‐2.02 to 8.22; P = 0.24; Analysis 1.4) or at follow‐up (MD 3.40, 95% CI ‐1.74 to 8.54; P = 0.19; Analysis 2.4). These findings were based on one trial with a small number of participants, resulting in a very low quality of evidence.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of intervention, Outcome 4 Measures of motor impairment: Fugl‐Meyer Assessment lower extremity.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of follow‐up, Outcome 4 Measures of motor impairment: Fugl‐Meyer Assessment lower extremity.

One study assessed the FMA upper extremity score (Abu Tariah 2010). We found no significant effect of CME at the end of intervention (MD 4.43, 95% CI ‐2.09 to 10.95; P = 0.18; Analysis 1.5) or at follow‐up (MD 2.75, 95% CI ‐8.24 to 13.74; P = 0.62; Analysis 2.5). These findings were based on only one trial with a small number of participants. Therefore, the quality of evidence was very low.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of intervention, Outcome 5 Measures of motor impairment: Fugl‐Meyer Assessment upper extremity.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of follow‐up, Outcome 5 Measures of motor impairment: Fugl‐Meyer Assessment upper extremity.

Gait and gait‐related measures

Balance

Two trials reported the BBS (Galvin 2011; Wang 2015). We found a significant summary effect (MD 6.35, 95% CI 1.64 to 11.06; P = 0.008; Table 3). One study assessed the Postural Assessment Scale for Stroke Patients (Dai 2013), and found no significant effect of CME (MD 3.50, 95% CI ‐0.52 to 7.52; P = 0.09; Table 3). Overall, we found a significant summary effect of CME on standing balance performance at the end of the intervention (SMD 0.53, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.87; P = 0.002; Analysis 1.6). These findings were based on a small total number of participants and there was clinical heterogeneity between studies resulting in a low quality of evidence. One trial was of unclear risk of bias (Dai 2013), but more than half of the trials were of low risk of bias (Galvin 2011; Wang 2015), and thus there was no reason to downgrade the level of evidence further.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of intervention, Outcome 6 Gait and gait‐related measures: balance: combined.

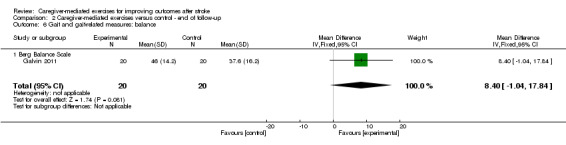

Only one trial assessed standing balance performance at three months' follow‐up (Galvin 2011). There was no significant effect (MD 8.40, 95% CI ‐1.04 to 17.84; P = 0.08; Analysis 2.6). This effect was based on one trial with a small number of participants resulting in a very low quality of evidence.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of follow‐up, Outcome 6 Gait and gait‐related measures: balance.

Walking distance

Two trials used the Six‐Minute Walk Test to assess walking distance (Galvin 2011; Wang 2015). We found no significant summary effect of CME at the end of the intervention period (MD 30.98 m, 95% CI ‐20.22 to 82.19; P = 0.24; Analysis 1.7). These findings were based on two trials with a low risk of bias, but with a small total number of participants for this outcome measure, resulting in a moderate quality of evidence.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of intervention, Outcome 7 Gait and gait‐related measures: Six‐Minute Walk Test.

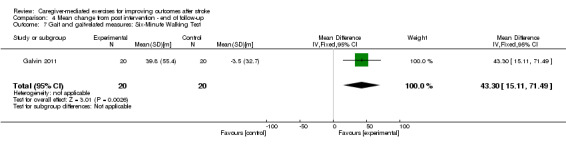

Only one trial assessed the Six‐Minute Walk Test at three months' follow‐up (Galvin 2011). There was a significant effect in favour of CME (MD 109.50 m, 95% CI 17.12 to 201.88; P = 0.02; Analysis 2.7). This finding was based on one trial with a small number of participants, resulting in a very low quality of evidence.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of follow‐up, Outcome 7 Gait and gait‐related measures: Six‐Minute Walking Test.

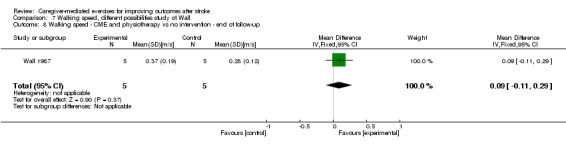

Walking speed

Two trials reported comfortable walking speed (Wall 1987; Wang 2015). We found no significant summary effect of CME on walking speed (MD 0.08 m/s, 95% CI ‐0.03 to 0.18; P = 0.17; Analysis 1.8). This effect was based on one trial with low risk of bias (Wang 2015) and one trial with an unclear risk of bias (Wall 1987). In addition, there was a small total number of participants. Therefore, the quality of evidence was low.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of intervention, Outcome 8 Gait and gait‐related measures: walking speed.

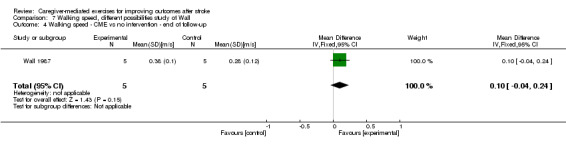

Only Wall 1987 reported follow‐up data three months after termination of the intervention. We found no significant effect of CME on walking speed (MD 0.10 m/s, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.22; P = 0.10; Analysis 2.8). The quality of evidence was very low, because the effect was based on only one trial of unclear risk of bias with a small total number of participants.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of follow‐up, Outcome 8 Gait and gait‐related measures: walking speed.

Measures of upper limb activities or function

Two trials with low risk of bias used the Wolf Motor Function test and the Motor Activity Log (Abu Tariah 2010; Barzel 2015). However, there may be publication bias, because all studies excluded for meta‐analysis were about upper limb training (Agrawal 2013; Gómez 2014; Souza 2015). In addition, there was a small total number of participants for these outcome measures and we detected substantial unexplained statistical heterogeneity between trials. We graded the quality of the evidence as very low, except the Wolf Motor Function test ‐ performance time and the Motor Activity Log ‐ amount of use at the end of intervention, and the Motor Activity Log ‐ quality of movement at both end of intervention and follow‐up. We did not detect any substantial statistical heterogeneity in these cases and, therefore, we graded the quality of evidence as low.

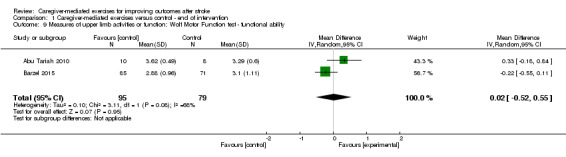

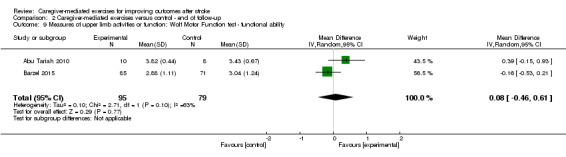

We found no significant summary effect of CME on the Wolf Motor Function test ‐ functional ability (end of intervention: MD 0.02, 95% CI ‐0.52 to 0.55; P = 0.95; Analysis 1.9; follow‐up four to six months after termination: MD 0.08, 95% CI ‐0.46 to 0.61; P = 0.77; Analysis 2.9), the Motor Activity Log ‐ amount of use (end of intervention: MD 0.01, 95% CI ‐0.36 to 0.38; P = 0.96; Analysis 1.11; follow‐up four to six months after termination: MD 0.21, 95% CI ‐0.65 to 1.08; P = 0.63; Analysis 2.11), and Motor Activity Log ‐ quality of movement (end of intervention: MD 0.08, 95% CI ‐0.26 to 0.42; P = 0.64; Analysis 1.12; follow‐up four to six months after termination: MD ‐0.03, 95% CI ‐0.43 to 0.37; P = 0.89; Analysis 2.12).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of intervention, Outcome 9 Measures of upper limb activities or function: Wolf Motor Function test ‐ functional ability.

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of follow‐up, Outcome 9 Measures of upper limb activities or function: Wolf Motor Function test ‐ functional ability.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of intervention, Outcome 11 Measures of upper limb activities or function: Motor Activity Log (MAL) ‐ amount of use.

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of follow‐up, Outcome 11 Measures of upper limb activities or function: Motor Activity Log ‐ amount of use.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of intervention, Outcome 12 Measures of upper limb activities or function: MAL ‐ quality of movement.

2.12. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of follow‐up, Outcome 12 Measures of upper limb activities or function: Motor Activity Log ‐ quality of movement.

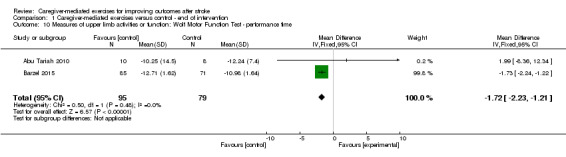

For the Wolf Motor Function test ‐ performance time, we found a significant summary effect in favour of the control group post intervention (MD ‐1.72, 95% CI ‐2.23 to ‐1.21; P < 0.00001; Analysis 1.10), but not at follow‐up (MD 1.85, 95% CI ‐8.78 to 12.48; P = 0.73; Analysis 2.10).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of intervention, Outcome 10 Measures of upper limb activities or function: Wolf Motor Function Test ‐ performance time.

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of follow‐up, Outcome 10 Measures of upper limb activities or function: Wolf Motor Function test ‐ performance time.

One trial used the Nine Hole Peg test (Barzel 2015). We found no significant effect post intervention (MD ‐0.04, 95% CI ‐0.11 to 0.03; P = 0.26; Analysis 1.13) or at follow‐up (MD ‐0.05, 95% CI ‐0.12 to 0.02; P = 0.17; Analysis 2.13). This evidence was based on one trial with a small number of participants, resulting in a very low quality of evidence.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of intervention, Outcome 13 Measures of upper limb activities or function: Nine Hole Peg test.

2.13. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of follow‐up, Outcome 13 Measures of upper limb activities or function: Nine Hole Peg test.

Measures of mood and quality of life of the patient

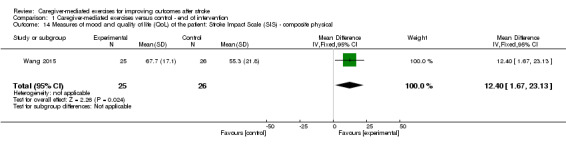

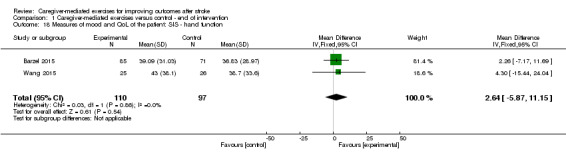

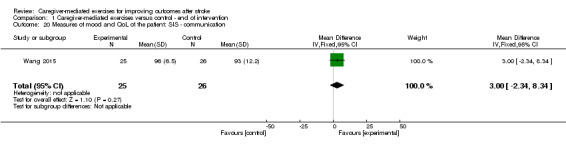

One trial assessed QoL of the patients with the SIS 3.0 at the end of the intervention (Wang 2015), and one trial assessed only SIS hand function (Barzel 2015).

The effect of CME was significant for the composite physical scale (MD 12.40, 95% CI 1.67 to 23.13; P = 0.02; Analysis 1.14), mobility scale (MD 18.20, 95% CI 7.54 to 28.86; P = 0.0008; Analysis 1.17), and general recovery scale (MD 15.10, 95% CI 8.44 to 21.76; P < 0.00001; Analysis 1.23).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of intervention, Outcome 14 Measures of mood and quality of life (QoL) of the patient: Stroke Impact Scale (SIS) ‐ composite physical.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of intervention, Outcome 17 Measures of mood and QoL of the patient: SIS ‐ mobility.

1.23. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of intervention, Outcome 23 Measures of mood and QoL of the patient: SIS ‐ general recovery.

For SIS hand function at follow‐up (Barzel 2015), we found no significant effect (MD ‐2.20, 95% CI ‐12.46 to 8.06; P = 0.67; Analysis 2.14). These findings were based on one trial with a small number of participants resulting in a very low quality of evidence. The reported effects on SIS hand function were based on two trials with low risk of bias, but with clinical heterogeneity between studies, resulting in a moderate quality of evidence.

2.14. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of follow‐up, Outcome 14 Measures of mood and quality of life of the patient: Stroke Impact Scale (SIS) ‐ hand function.

Measures of fatigue of the patient

None of the trials reported on effects of CME on fatigue of the patient after intervention or at follow‐up.

Length of stay

None of the included trials reported length of stay as an outcome measure. However, Galvin 2011 did state that mean length of hospital stay for the intervention group was 35.7 days (SD 10.5) and for the control group was 40.1 days (SD 15). Mean length of stay in a rehabilitation unit was 40.3 days (SD 9.6) for the intervention group and 52.3 days (SD 40) for the control group. Patients were recruited in a hospital and a rehabilitation unit. We found no significant differences for length of stay in a hospital (MD 4.40 days, 95% CI ‐3.91 to 12.71; P = 0.30; Analysis 1.24) or length of stay in a rehabilitation unit (MD 12.0 days, 95% CI ‐10.88 to 34.88; P = 0.30; Analysis 1.25). These effects were based on one trial, and length of stay was reported for a small number of participants (n = 20). Therefore, we graded the quality of the evidence as very low.

1.24. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of intervention, Outcome 24 Length of stay ‐ hospital.

1.25. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of intervention, Outcome 25 Length of stay ‐ rehabilitation unit.

Adverse outcomes

One trial reported falls among participants (Dai 2013). We found no significant effect of CME on the number of falls reported (MD 0.04, 95% CI ‐0.10 to 0.18; P = 0.57; Analysis 1.26). There was no follow‐up in this trial. This effect was based on one trial with unclear risk of bias and a small number of participants, resulting in a very low quality of evidence.

1.26. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Caregiver‐mediated exercises versus control ‐ end of intervention, Outcome 26 Adverse outcomes: falls.

Caregiver: measures of mood and quality of life

None of the included trials reported measures of mood or QoL of the caregiver.

Other outcomes

See Table 4.

3. Results 'other outcomes' (not included in meta‐analysis).

| Outcome |

Control group (mean (SD)) |

Intervention group (mean (SD)) |

||||

| Baseline | Post intervention | Follow‐up | Baseline | Post intervention | Follow‐up | |

| Behavioural Inattention Test Conventional (Dai 2013) | 48.79 (44.64) | 68.83 (44.72) | ‐ | 49.71 (39.63) | 88.71 (44.56) | ‐ |

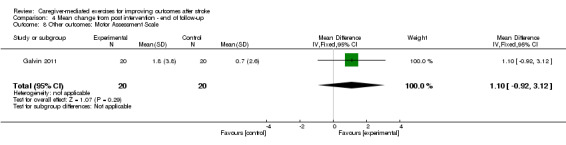

| Motor Assessment Scale (Galvin 2011) | 29.7 (12.9) | 34.5 (11.6) | 35.2 (10.8) | 24.3 (11.1) | 36.1 (10.2) | 37.9 (9.7) |

SD: standard deviation.

Wall 1987 reported on gait parameters such as duration of single support phase and asymmetry ratio. We did not summarise these findings because they were beyond the scope of this review.

Dose of training

In three trials, the dose of training was comparable between the intervention and control groups (Abu Tariah 2010; Souza 2015; Wall 1987).

In six trials, the dose of training in the intervention group was higher than the dose of training in the control group (Agrawal 2013; Barzel 2015; Dai 2013; Galvin 2011; Gómez 2014; Wang 2015). In four of these trials, there was as higher dose of training in the intervention group because the intervention was additional to usual care and the control group received only usual care (Agrawal 2013; Dai 2013; Galvin 2011; Gómez 2014). In one trial, the intensity of training in the intervention group was higher due to the differences between interventions in the intervention and control groups (Wang 2015). The study compared a 90‐minute visit of a therapist and performing activities at least twice weekly, and if possible, every day in the intervention group, with a weekly visit or telephone call of the therapist and maintaining daily routines in the control group. In one trial, daily CIMT, which is a high‐intensity training intervention, was compared with usual care (Barzel 2015). With that, the intensity of training in the intervention group was higher than the dose of training in the control group.

We could not perform subgroup analysis for dose of training (higher dose of training versus same dose of training). For most outcome measures, all included trials had a higher dose of training in the intervention group, so no comparison could be made. For walking speed and upper arm function (Wolf Motor Function test and Motor Activity Log), one included trial was in the higher dose of training group and one included trial was in the same dose of training group. Because there was only one study per subgroup for these outcome measures, we did not perform a subgroup analysis.

Timing post stroke (Comparison 3)

We performed subgroup analyses for trials that included patients within six months after stroke (Agrawal 2013; Dai 2013; Galvin 2011; Gómez 2014) versus trials that included patients beyond six months after stroke (Barzel 2015; Wall 1987; Wang 2015). One trial included patients from beyond two months after stroke (Abu Tariah 2010), and another included patients directly after stroke (Souza 2015); however, the reported mean time since stroke was about nine months after stroke in the Abu Tariah 2010 study and 30 months after stroke in the Souza 2015 study. Therefore, we included both trials in the chronic phase group.

Because of the low number of included trials, we could only perform a subgroup analysis for the outcome measure basic ADL at the end of intervention. We found no difference between trials that included participants within six months after stroke when compared with trials that included patients beyond six months after stroke (P = 0.21; Analysis 3.1). The quality of evidence for this comparison was low, due to clinical heterogeneity between studies and a small total number of participants per subgroup.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Timing post stroke ‐ end of intervention, Outcome 1 Patient: activities of daily living measures: combined.

For all other outcome measures, the number of included trials per subgroup was too low to test for subgroup differences.

Upper and lower extremity

Five trials were aimed at the upper extremity (Abu Tariah 2010; Agrawal 2013; Barzel 2015; Gómez 2014; Souza 2015), and four of these trials were about CIMT (Abu Tariah 2010; Barzel 2015; Gómez 2014; Souza 2015). However, Agrawal 2013, Gómez 2014, and Souza 2015 were not included in meta‐analysis.

Two trials were specifically aimed at the lower extremity (Galvin 2011; Wall 1987).

Basic and extended ADL were the only outcome measures in common when comparing upper and lower extremity trials. Due to the low number of trials per subgroup, we could not perform a subgroup analysis.

Reported mean changes (Comparison 4)

Mean change from post intervention to follow‐up

Galvin 2011 reported mean change at follow‐up (three months after termination of the intervention) from post intervention, using the outcome measures BI, CSI, NEADL Index, Reintegration to Normal Living Index, FMA lower extremity score, BBS, Six‐Minute Walk Test, and the Motor Assessment Scale.