Abstract

Background

Acquired adult‐onset hearing loss is a common long‐term condition for which the most common intervention is hearing aid fitting. However, up to 40% of people fitted with a hearing aid either fail to use it or may not gain optimal benefit from it. This is an update of a review first published in The Cochrane Library in 2014.

Objectives

To assess the long‐term effectiveness of interventions to promote the use of hearing aids in adults with acquired hearing loss fitted with at least one hearing aid.

Search methods

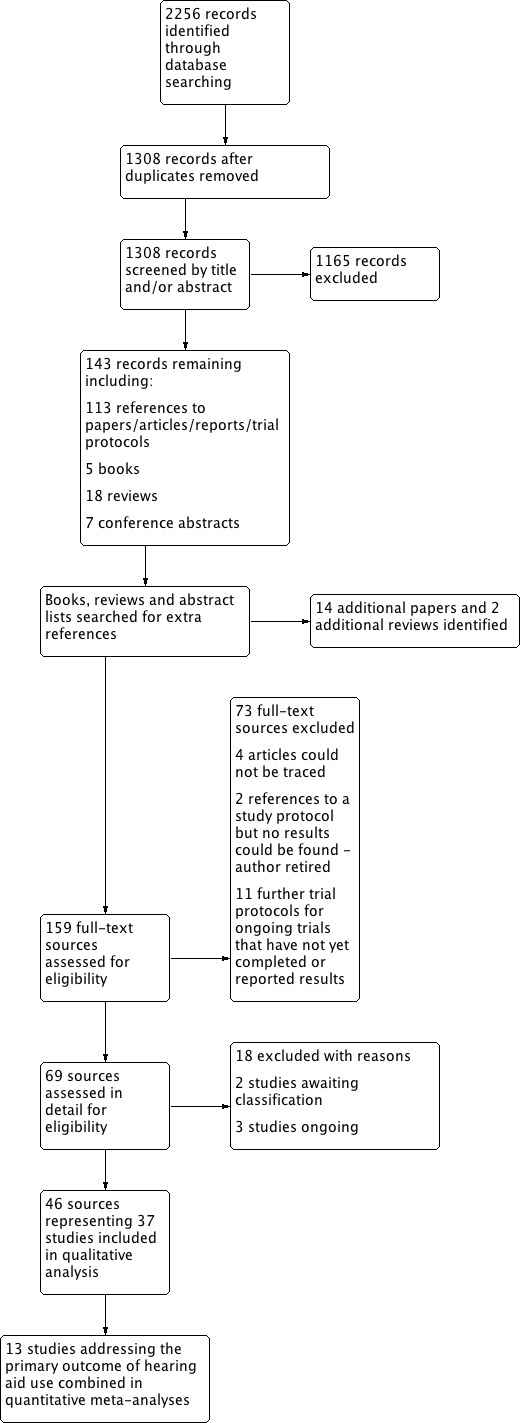

The Cochrane ENT Information Specialist searched the Cochrane ENT Trials Register; Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2016, Issue 5); PubMed; EMBASE; CINAHL; Web of Science; ClinicalTrials.gov; ICTRP and additional sources for published and unpublished trials. The date of the search was 13 June 2016.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of interventions designed to improve or promote hearing aid use in adults with acquired hearing loss compared with usual care or another intervention. We excluded interventions that compared hearing aid technology. We classified interventions according to the 'chronic care model' (CCM). The primary outcomes were hearing aid use (measured as adherence or daily hours of use) and adverse effects (inappropriate advice or clinical practice, or patient complaints). Secondary patient‐reported outcomes included quality of life, hearing handicap, hearing aid benefit and communication. Outcomes were measured over the short (</= 12 weeks), medium (> 12 to < 52 weeks) and long term (one year plus).

Data collection and analysis

We used the standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane.

Main results

We included 37 studies involving a total of 4129 participants. Risk of bias across the included studies was variable. We judged the GRADE quality of evidence to be very low or low for the primary outcomes where data were available.

The majority of participants were over 65 years of age with mild to moderate adult‐onset hearing loss. There was a mix of new and experienced hearing aid users. Six of the studies (287 participants) assessed long‐term outcomes.

All 37 studies tested interventions that could be classified using the CCM as self‐management support (ways to help someone to manage their hearing loss and hearing aid(s) better by giving information, practice and experience at listening/communicating or by asking people to practise tasks at home) and/or delivery system design interventions (just changing how the service was delivered).

Self‐management support interventions

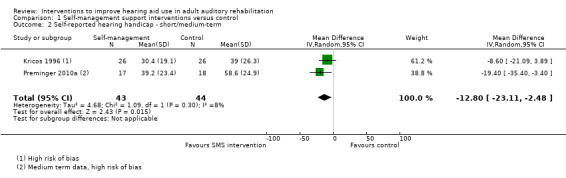

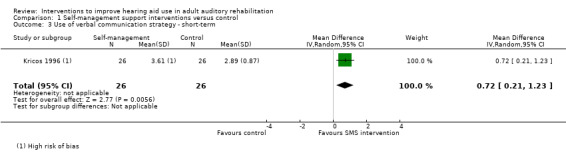

We found no studies that investigated the effect of these interventions on adherence, adverse effects or hearing aid benefit. Two studies reported daily hours of hearing aid use but we were unable to combine these in a meta‐analysis. There was no evidence of a statistically significant effect on quality of life over the medium term. Self‐management support reduced short‐ to medium‐term hearing handicap (two studies, 87 participants; mean difference (MD) ‐12.80, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐23.11 to ‐2.48 (0 to 100 scale)) and increased the use of verbal communication strategies in the short to medium term (one study, 52 participants; MD 0.72, 95% CI 0.21 to 1.23 (0 to 5 scale)). The clinical significance of these statistical findings is uncertain. It is likely that the outcomes were clinically significant for some, but not all, participants. Our confidence in the quality of this evidence was very low. No self‐management support studies reported long‐term outcomes.

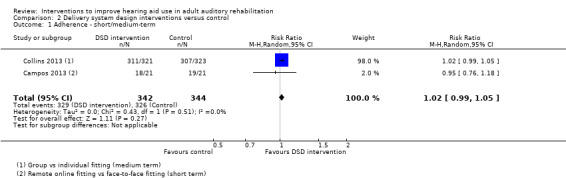

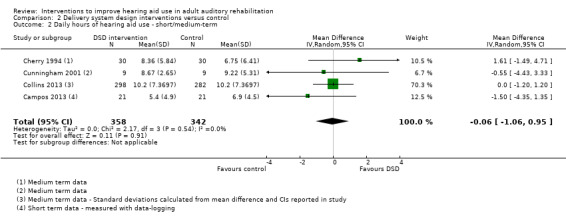

Delivery system design interventions

These interventions did not significantly affect adherence or daily hours of hearing aid use in the short to medium term, or adverse effects in the long term. We found no studies that investigated the effect of these interventions on quality of life. There was no evidence of a statistically or clinically significant effect on hearing handicap, hearing aid benefit or the use of verbal communication strategies in the short to medium term. Our confidence in the quality of this evidence was low or very low. Long‐term outcome measurement was rare.

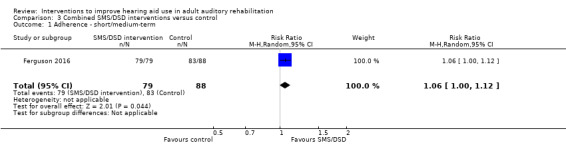

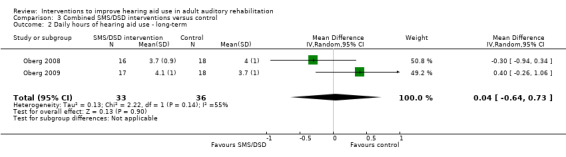

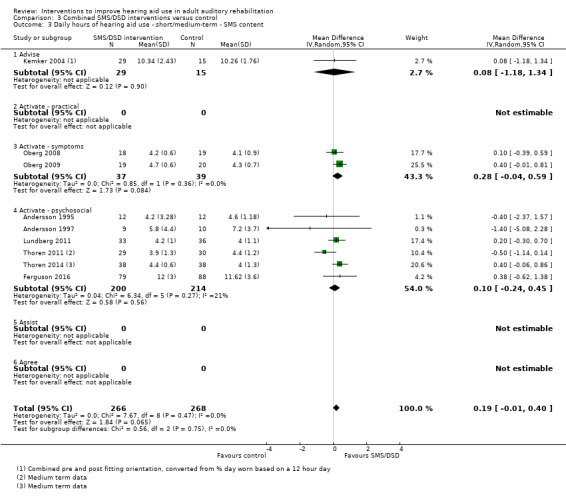

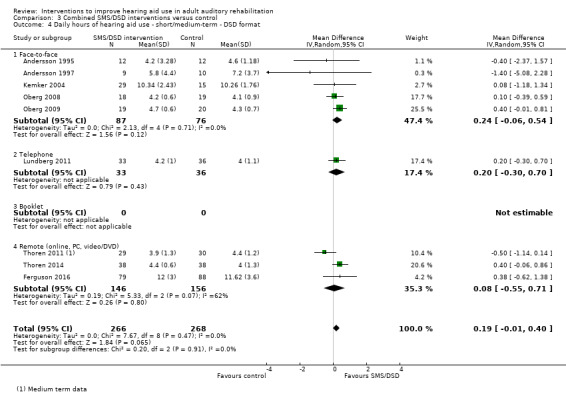

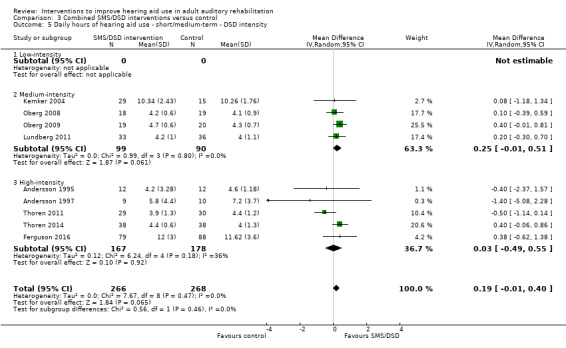

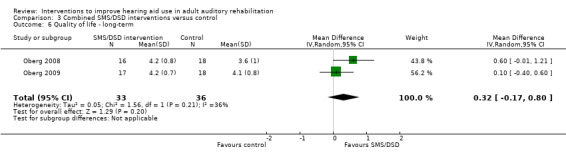

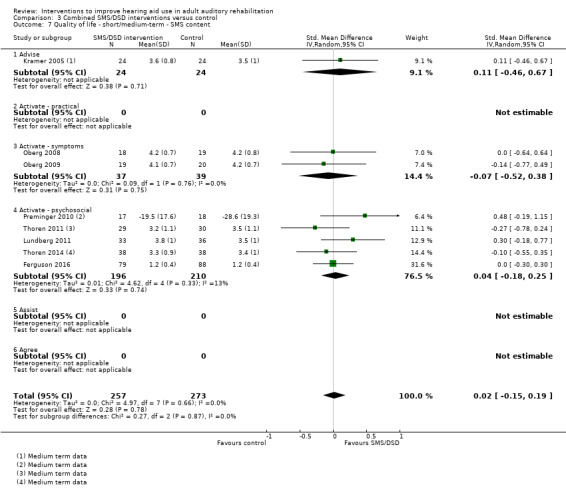

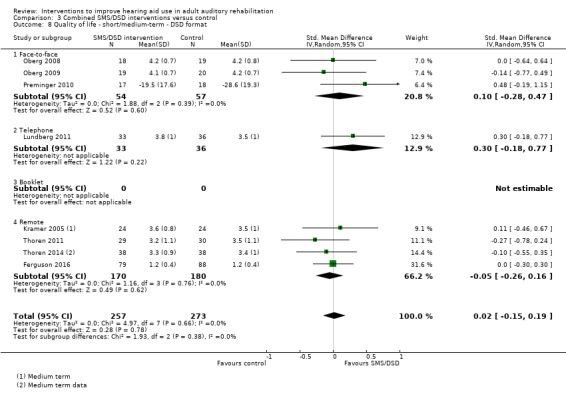

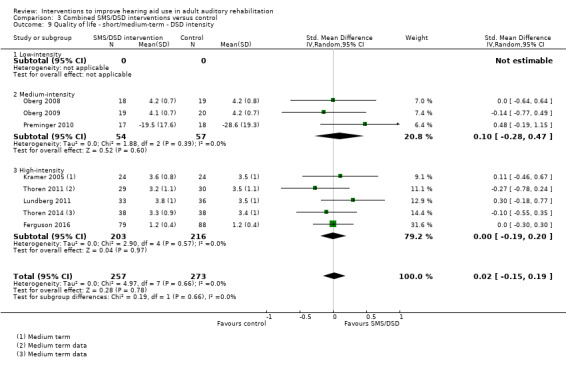

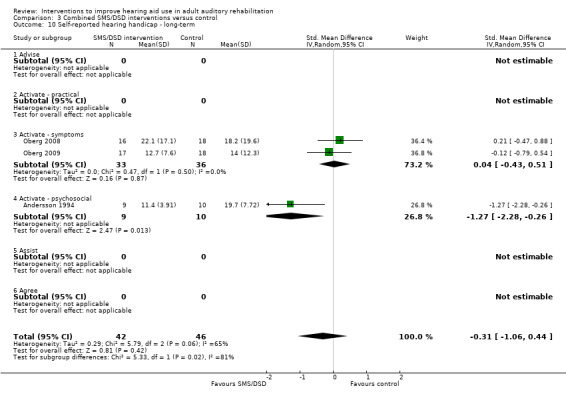

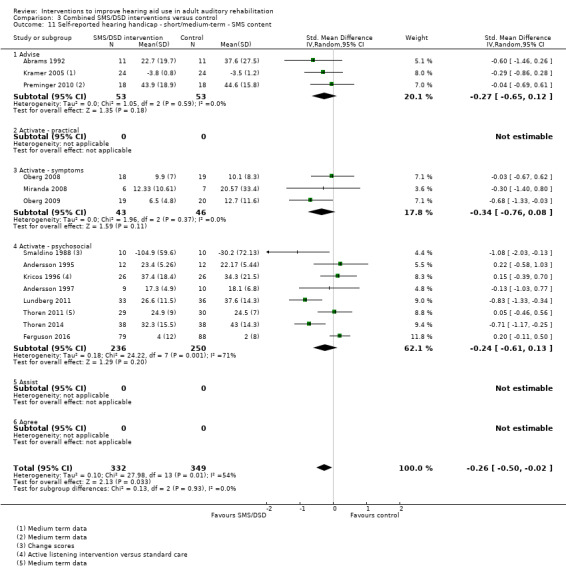

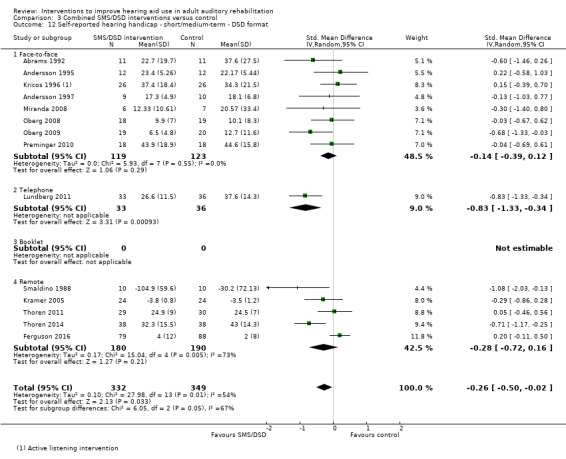

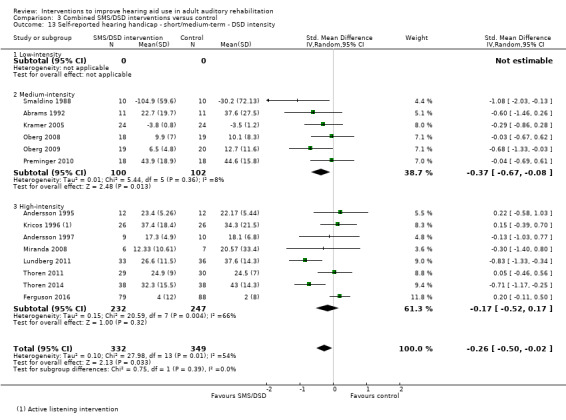

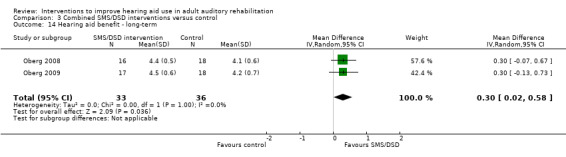

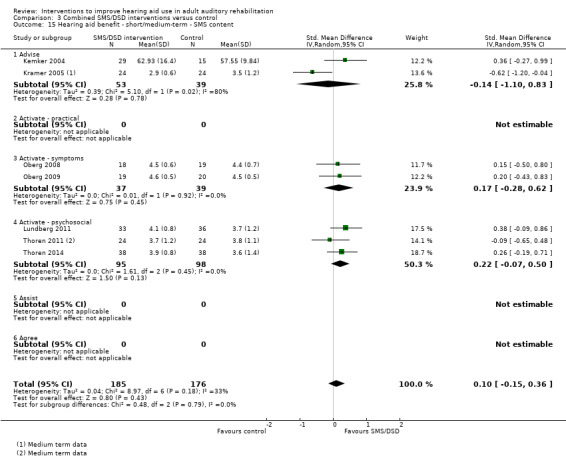

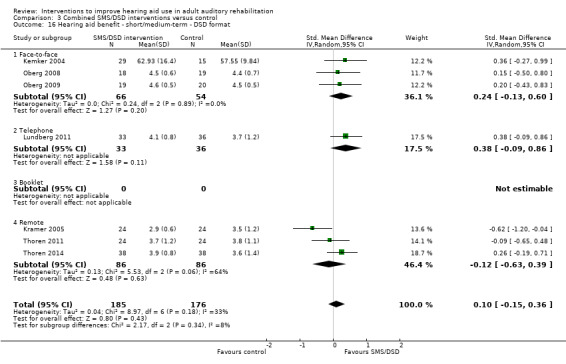

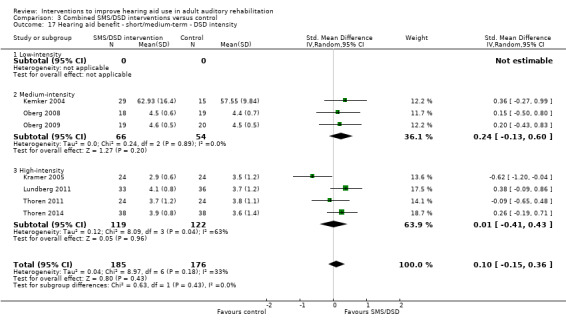

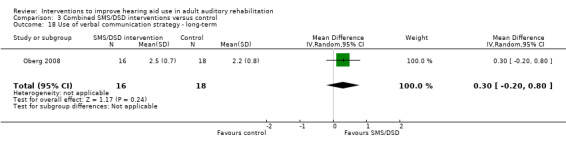

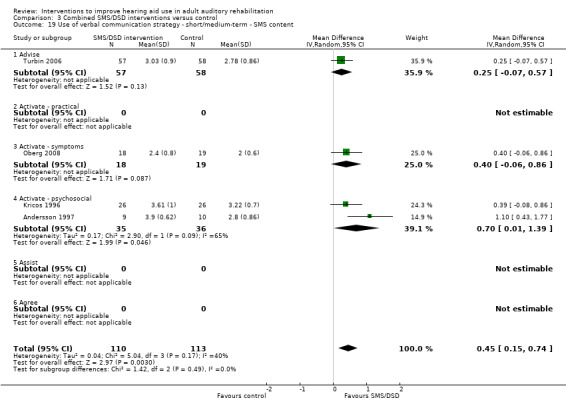

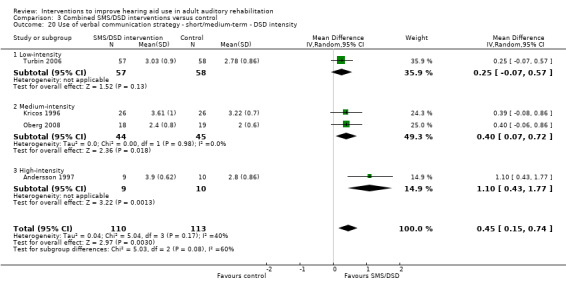

Combined self‐management support/delivery system design interventions

One combined intervention showed evidence of a statistically significant effect on adherence in the short term (one study, 167 participants, risk ratio (RR) 1.06, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.12). However, there was no evidence of a statistically or clinically significant effect on daily hours of hearing aid use over the long term, or the short to medium term. No studies of this type investigated adverse effects. There was no evidence of an effect on quality of life over the long term, or short to medium term. These combined interventions reduced hearing handicap in the short to medium term (14 studies, 681 participants; standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.26, 95% CI ‐0.50 to ‐0.02). This represents a small‐moderate effect size but there is no evidence of a statistically significant effect over the long term. There was evidence of a statistically, but not clinically, significant effect on long‐term hearing aid benefit (two studies, 69 participants, MD 0.30, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.58 (1 to 5 scale)), but no evidence of an effect over the short to medium term. There was evidence of a statistically, but not clinically, significant effect on the use of verbal communication strategies in the short term (four studies, 223 participants, MD 0.45, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.74 (0 to 5 scale)), but not the long term. Our confidence in the quality of this evidence was low or very low.

We found no studies that assessed the effect of other CCM interventions (decision support, the clinical information system, community resources or health system changes).

Authors' conclusions

There is some low to very low quality evidence to support the use of self‐management support and complex interventions combining self‐management support and delivery system design in adult auditory rehabilitation. However, effect sizes are small. The range of interventions that have been tested is relatively limited. Future research should prioritise: long‐term outcome assessment; development of a core outcome set for adult auditory rehabilitation; and study designs and outcome measures that are powered to detect incremental effects of rehabilitative healthcare system changes.

Plain language summary

Interventions to improve hearing aid use in adult auditory rehabilitation

Review question

We wanted to know if any interventions help people to wear their hearing aids more. We measured effects over the short term (less than 12 weeks), medium term (from 12 to 52 weeks) and long term (one year plus). This is an update of a review first published in The Cochrane Library in 2014.

Background

Hearing loss is very common. People who get hearing loss as adults are often offered a hearing aid(s). However, up to 40% of people fitted with a hearing aid choose not to use it.

Study characteristics

The evidence is up to date as of June 2016. We found 37 studies involving a total of 4129 people. Most of the people in the studies were aged over 65. There was a mix of new and experienced hearing aid users. Seven studies funded by the United States Veterans Association dominate the evidence. The 1297 people in these studies were serving in the military or military veterans. All but two of the other studies included fewer than 100 people in each study.

Results

Thirty‐three of the 37 studies looked at ways to help someone to manage their hearing loss and hearing aid(s) better by giving information, practice and experience at listening/communicating or by asking people to practise tasks at home. These are forms of self‐management support. Most of these studies also changed how the self‐management support was provided, for example by changing the number of appointment sessions or using telephone or email follow‐up.

Six studies looked at the effect of just changing how the service was delivered. No studies looked at the effect of using guidelines or standards, computerised medical record systems, community resources or changing the health system.

We found no evidence that the interventions helped people to wear their hearing aids for more hours per day over the short, medium or long term. One study that used interactive videos to give information after hearing aid fitting encouraged more people to wear their hearing aids.

We found no evidence of adverse effects of any of the interventions, but it was rare for studies to look for adverse effects.

Giving self‐management support meant that people reported less hearing handicap and improved verbal communication over the short term. When this was combined with changing how the support was delivered people also reported slightly more hearing aid benefit over the long term.

Only six studies (287 people) looked at how people were doing after a year or more.

Conclusions

Complex interventions that deliver self‐management support in different ways improve some outcomes for some people with hearing loss who use hearing aids. We found no interventions that increased self‐reported daily hours of hearing aid use. Few studies measured how many people use hearing aids compared to how many are fitted (adherence). Many things that might increase daily hours of hearing aid use or encourage more people to wear the hearing aids they have been fitted with have not been tested. It was difficult to combine data across different studies because many outcome measures were used and results were not always fully reported. In future it would be helpful if researchers:

‐ used existing guidelines for presenting their results;

‐ agreed a set of outcome measures for use in this type of study; and

‐ focused on long‐term outcomes where people are followed up for at least a year.

Quality of the evidence

We judged the evidence to be of very low or low quality. There was risk of bias in the way many of the studies were carried out or reported. The largest studies included only military veterans. We do not know whether studies would find the same results in more mixed populations. Most of the other studies had small sample sizes. Very few studies measured long‐term outcomes.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Self‐management support interventions for adults with hearing loss who use hearing aids.

| Self‐management support interventions for adults with hearing loss who use hearing aids | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with hearing loss who use hearing aids Settings: outpatient clinic Intervention: self‐management support interventions | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Self‐management support interventions | |||||

| Adherence | No studies identified | |||||

| Daily hours of hearing aid use | Two studies reported daily hours of hearing aid use but we were unable to combine these in a meta‐analysis | |||||

| Adverse effects | No studies identified | |||||

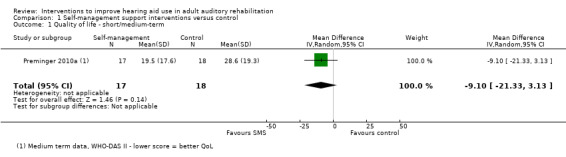

| Quality of life Validated self‐report measures. WHODAS 2.0 scale from: 0 to 100 Follow‐up: 0 to 12 months | The mean quality of life in the intervention group was 9.1 lower (21.33 lower to 3.13 higher) than in the control group (on this generic health‐related quality of life scale (WHODAS 2.0) a lower score indicates better quality of life) | — | 35 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | The minimal important difference on this scale has not been established for hearing health care. | |

| Self‐reported hearing handicap Validated self‐report measure: HHIE (Ventry 1982) scale from 0 to 100 Follow‐up: 0 to 12 months | The mean self‐reported hearing handicap in the intervention groups was 12.80 lower (23.11 lower to 2.48 lower) than in the control groups (lower score indicates less handicap) | — | 87 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2 | The minimal important difference on this scale is reported to be 18.7 for face‐to face administration and 36 for pencil and paper (Weinstein 1986). | |

| Hearing aid benefit | No studies identified | |||||

|

Communication Validated self‐report measure: verbal subscale of the CPHI (Demorest 1987) scale from 0 to 5 Follow‐up: 0 to 12 months |

The mean reported use of verbal communication strategy in the intervention group was 0.72 higher (0.21 higher to 1.23 higher) than in the control group (higher score indicates increased use of verbal communication strategy) | — | 52 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3 | The minimal important difference for this subscale of the CPHI is 0.93 at the 0.05 level (Demorest 1988). | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CPHI: Communication Profile for the Hearing Impaired; RR: risk ratio; WHODAS 2.0: World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Downgraded due to very serious concerns regarding limitations in study design (risk of bias), indirectness (participants were military veterans and only short‐ to medium‐term outcomes were available) and serious concerns regarding imprecision (single study with small sample size). 2Downgraded due to very serious concerns regarding limitations in study design (risk of bias) and serious concerns due to indirectness (only short‐ to medium‐term outcomes available) and imprecision (two small studies with a high risk of skewed data). 3Downgraded due to very serious concerns regarding limitations in study design (risk of bias) and serious concerns due to indirectness (only short‐ to medium‐term outcomes available) and imprecision (single study with small sample size).

Summary of findings 2. Delivery system design interventions for adults with hearing loss who use hearing aids.

| Delivery system design interventions for adults with hearing loss who use hearing aids | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with hearing loss who use hearing aids Settings: outpatient clinic Intervention: delivery system design interventions | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Delivery system design interventions | |||||

| Adherence Number of people fitted with hearing aid/number of people who use the aids Follow‐up: 0 to 12 months | 948 per 1000 | 967 per 1000 (938 to 995) | RR 1.02 (0.99 to 1.05) | 686 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | — |

| Daily hours of hearing aid use Average self‐reported or data‐logged hours of use per day. Scale from: 0 to 12 hours Follow‐up: 0 to 12 months | The mean daily hours of hearing aid use in the intervention groups was 0.06 lower (1.06 lower to 0.95 higher) than in the control groups. On average the intervention groups used their hearing aids for under a minute per day less than the control groups | — | 700 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2 | Participants in the intervention groups wore their hearing aids for 3 to 4 minutes less each day on average than those in the control group. This is not a clinically significant difference | |

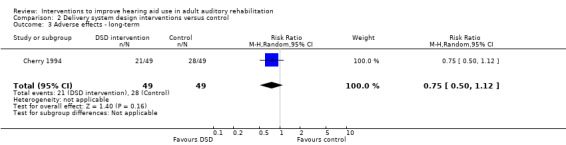

| Adverse effects Number of outstanding complaints Follow‐up: 1+ years | 571 per 1000 | 429 per 1000 (286 to 640) | RR 0.75 (0.5 to 1.12) | 98 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3 | — |

| Quality of life | No studies identified | |||||

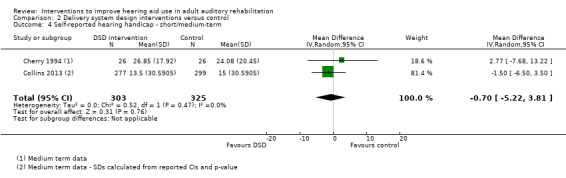

| Self‐reported hearing handicap Validated self‐report measure HHIE scale from: 0 to 100 (Ventry 1982) Follow‐up: 0 to 12 months | The mean self‐reported hearing handicap in the intervention groups was 0.7 lower (5.22 lower to 3.81 higher) than in the control groups (on this scale from 0 to 100, a lower score indicates less hearing handicap) | — | 628 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low4 | The minimal important difference on this scale is reported to be 18.7 for face‐to‐face administration and 36 for pencil and paper (Weinstein 1986) | |

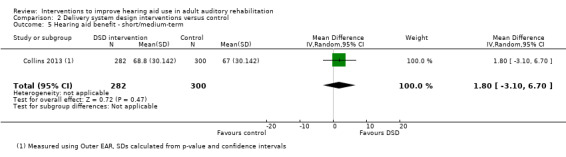

| Hearing aid benefit Validated self‐report measure. Outer EAR scale from: 0 to 100 Follow‐up: mean 6 months | The mean hearing aid benefit in the intervention group was 1.8 higher (3.1 lower to 6.7 higher) than in the control group (on this scale from 0 to 100, a higher score indicates more hearing aid benefit) | — | 582 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low4 | While we were unable to reference a minimal important difference for this scale, a mean difference of 1.8 on a scale from 0 to 100 is unlikely to be a clinically significant change | |

|

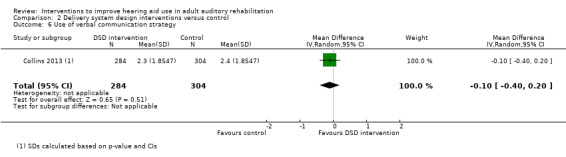

Communication Validated self‐report measure: verbal subscale of the CPHI scale from 0 to 5 (Demorest 1987) Follow‐up: 0 to 12 months |

The mean reported use of verbal communication strategy in the intervention group was 0.10 higher (0.40 lower to 0.20 higher) than in the control group (higher score indicates increased use of verbal communication strategy) | — | 588 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low5 | The minimal important difference for this subscale of the CPHI is 0.93 at the 0.05 level (Demorest 1988) | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CPHI: Communication Profile for the Hearing Impaired; HHIE: Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Downgraded due to very serious concerns regarding indirectness of the evidence (only short‐ to medium‐term evidence and the majority of the participants were military veterans). 2Downgraded due to very serious concerns regarding indirectness (short‐ to medium‐term data and military veteran participants) and serious concerns about limitations in study design (unclear risk of bias) and imprecision (standard deviations imputed in the largest study). 3Downgraded due to very serious concerns regarding indirectness (short‐ to medium‐term data and military veteran participants) and serious concerns regarding limitations in study design (unclear risk of bias) and imprecision (small sample size, wide CIs). 4Downgraded due to very serious concerns regarding indirectness (short‐ to medium‐term data and military veteran participants) and serious concerns about imprecision (standard deviations imputed). 5Downgraded due to very serious concerns regarding indirectness (short‐ to medium‐term outcomes, military veteran participants and the lack of a global communication outcome measure) and serious concerns about imprecision (standard deviations imputed).

Summary of findings 3. Combined self‐management support/delivery system design interventions for adults with hearing loss who use hearing aids.

| Combined self‐management support/delivery system design interventions for adults with hearing loss who use hearing aids | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with hearing loss who use hearing aids Settings: outpatient clinic Intervention: combined self‐management support/delivery system design interventions | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Combined SMS/DSD interventions | |||||

|

Adherence Number of people fitted with hearing aid/number of people who use the aids Follow‐up: 5 to 8 weeks |

943 per 1000 |

1000 per 1000 (943 to 1000) |

RR 1.06 (1 to 1.12) |

162 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | — |

| Daily hours of hearing aid use Self‐reported or data‐logged average hours of use per day. Scale from: 0 to 12 hours Follow‐up: 1+ years | The mean daily hours of hearing aid use in the intervention groups was 0.04 higher (0.64 lower to 0.73 higher) than in the control groups | — | 69 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2 | Participants in the intervention groups wore their hearing aids for 2 to 3 minutes more per day than those in the control group. This is not a clinically significant difference. | |

| Adverse effects | No studies identified | |||||

| Quality of life Validated self‐report measures. IOI‐HA item 7 scale from: 1 to 5 Follow‐up: 1+ years | The mean quality of life in the intervention groups was 0.32 higher (0.17 lower to 0.8 higher) than in the control groups, measured on item 7 of the IOI‐HA (Cox 2002) | — | 69 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3 | The minimally important difference for this subscale of the IOI‐HA is 0.32 for those with mild‐moderate hearing loss and 0.28 for those with moderate‐severe hearing loss (Smith 2009). | |

| Self‐reported hearing handicap Validated self‐report measures Follow‐up: 1+ years | The mean self‐reported hearing handicap in the intervention groups was 0.31 standard deviations lower (1.06 lower to 0.44 higher) than in the control groups | — | 88 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low4 | Using the classification suggested by Cohen 1988 a SMD of 0.31 represents a moderate effect size. | |

| Hearing aid benefit Validated self‐report measures (IOI‐HA item 4). Scale from: 1 to 5 Follow‐up: 1+ years | The mean hearing aid benefit in the intervention groups was 0.3 higher (0.02 to 0.58 higher) than in the control groups, measured on item 4 of the IOI‐HA (Cox 2002) | — | 69 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3 | This is a statistically significant difference. However, the minimally important difference for this subscale of the IOI‐HA is 0.39 for those with mild‐moderate hearing loss and 0.32 for those with moderate‐severe hearing loss (Smith 2009), so this does not represent a clinically important difference. | |

| Use of verbal communication strategy Validated self‐report measures (verbal subscale of the CPHI (Demorest 1987)). Scale from: 0 to 5 Follow‐up: 1+ years | The mean use of verbal communication strategy in the intervention groups was 0.3 higher (0.2 lower to 0.8 higher) than in the control groups | — | 34 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low5 | The minimal important difference for this subscale of the CPHI is 0.93 at the 0.05 level (Demorest 1988). | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CPHI: Communication Profile for the Hearing Impaired; DSD: delivery system design; IOI‐HA: International Outcome Inventory for Hearing Aids; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference; SMS: self‐management support | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Downgraded due to concerns regarding consistency (single study) and indirectness of the evidence (short‐term evidence only). 2Downgraded due to very serious concerns regarding imprecision (small sample size) and serious concerns regarding inconsistency (heterogeneity). 3Downgraded due to very serious concerns regarding imprecision (small sample size). 4Downgraded due to very serious concerns regarding imprecision (small sample size, risk of skewed data in two of the studies) and serious concerns regarding limitations in study design (high risk of bias in one study) and inconsistency (heterogeneity). 5Downgraded due to very serious concerns regarding imprecision (small sample size) and indirectness (lack of a global measure of communication, participants were all first‐time hearing aid users, we do not know whether equivalent benefit could be gained in people already fitted with hearing aids).

Background

This is an update of a review first published in The Cochrane Library in 2014.

Description of the condition

Adult acquired hearing loss is a common long‐term condition, which in the majority of cases is not remediable by surgical or medical intervention. It ranks 15th amongst the leading causes of global burden of disease and is the second leading cause of 'years lived with a disability' (WHO 2012). The prevalence of hearing loss increases with age, which has serious implications in a global population in which the proportion of elderly people is rising at unprecedented rates according to the World Health Organization (WHO 2011). The standard intervention for hearing loss, at least in the developed world, usually involves the provision of monaural or binaural hearing aids within an audiology clinic (Cox 2014). Despite the evidence of the negative consequences of hearing loss (Brooks 2001; Hallberg 1993; Lin 2011; Saito 2010), and the benefits of hearing aids (Bainbridge 2014; Chisolm 2007; Mulrow 1992; National Council on Aging 2000; Swan 2012), uptake of fitting is relatively low, even in countries where the provision of hearing aids is free at the point of use. In addition, results from studies on use and non‐use of hearing aids support the finding that a proportion of those being prescribed a hearing aid do not use it. Estimates of non‐use vary from 5% to 40% (Gimsing 2008; Lupsakko 2005; Smeeth 2002; Sorri 1984; Vuorialho 2006), and this is supported by commercial survey data from hearing aid dispensers (Hougaard 2011; Kochkin 2009). Some studies have highlighted poor sound quality or lack of perceived benefit as one of the reasons for non‐use (Brooks 1985; Lupsakko 2005; Smeeth 2002), and it is likely that developments in sound processing technology have had an effect over time, such as the move from analogue to digital sound processing. The more recent studies tend to show higher levels of use but there is still room for improvement. Recent evidence suggests that increased cost does not necessarily improve outcome over and above that gained from more cost‐effective options (Cox 2014). In addition, there is a reliable placebo effect when assessing different hearing aid technologies, which may have an impact on the results of unblinded studies (Dawes 2013). There are no data on rates of use in developing countries where access to hearing aid technology presents more of a challenge, although reasons for non‐use are starting to be investigated in less well‐resourced populations (Borg 2015).

Description of the intervention

This review considered any healthcare interventions aimed at improving or promoting the use of hearing aids in the context of acquired adult hearing loss. To provide a structure for this analysis we chose to classify interventions based on the chronic care model (CCM) (Bodenheimer 2002). This is a framework used to develop and describe initiatives in the care of long‐term conditions. Adult acquired hearing loss fits the World Health Organization definition of a long‐term condition in that it is a health problem that requires ongoing management over a period of years or decades (WHO 2002). We chose the CCM because it is widely cited, has been used in a variety of healthcare settings and its implementation has been associated with improved outcomes (DH 2007; NHS 2006; Tsai 2005). It has also been used as a framework in previous reviews looking at the effects of interventions in the context of long‐term conditions (Kreindler 2009; Tsai 2005).

We therefore hoped that this review would provide information on interventions and outcomes in the context of hearing loss as a long‐term condition.

We classified potential interventions according to the six elements of the CCM as follows:

1. Self‐management support interventions

Self‐management support is at the heart of the CCM and other frameworks used in the context of long‐term conditions. For chronic conditions such as hearing loss, patients themselves take on the primary responsibility for managing their condition. These are interventions that seek to empower and prepare patients to manage their own health and health care. They emphasise the patient's central role in managing their health. Self‐management support involves collaborating with patients and their families to help them develop the skills and confidence they need to do this effectively. In their review of self‐management approaches for people with long‐term conditions, Barlow and colleagues state that "self‐management refers to the individual's ability to manage the symptoms, treatment, physical and psychosocial consequences and life‐style changes inherent in living with a chronic condition" (Barlow 2002). Self‐management is a complex task.

The provision of self‐management support might therefore include:

self‐management assessment ‐ assessment of the impact of hearing loss, the difficulties it is causing and facilitators and barriers to potential solutions;

patient education;

patient activation ‐ interventions that involve practice of the behaviour changes needed to develop practical, symptom and psychosocial management skills;

self‐management resources and tools ‐ battery replacement services, provision of additional equipment to improve hearing aid benefit;

collaborative decision‐making (Tsai 2005).

These processes align to the Assess, Advise, Assist and Agree components of the 5As model of health behaviour change (Whitlock 2002). These have been applied previously in the context of long‐term condition self‐management (Glasgow 2003).

2. Delivery system design interventions

These interventions involve the introduction of systems to assure the delivery of efficient, effective care and self‐management support. Kreindler 2009 and Tsai 2005 describe how this includes interventions that:

reshape healthcare provider roles ‐ for example, introducing the role of case manager or defining roles within a multi‐disciplinary team;

reorganise the scheduling or organisation of care ‐ changes in care delivery, the provision of follow‐up or planned visits, visit system change.

Delivery system design interventions involve changes in the mode (for example, group versus individual), format (face‐to‐face, online, booklet etc.), timing or follow‐up pattern and location of delivery of self‐management support rather than the content of the support itself. This category would include interventions such as group counselling and group rehabilitation, providing the same content is delivered in the same way to the intervention and control group. It will also include interventions where changes have been made to the post‐fitting follow‐up process in terms of timing, quantity, location, mode or format of delivery. The 'arrange follow‐up' component of the 5As model would fit within this element.

In reality it is likely that many interventions will contain an element of self‐management support and delivery system design because in order to provide self‐management support some changes in delivery system design are likely to be needed (Tsai 2005).

3. Decision support interventions

Decision support interventions promote clinical care that is consistent with scientific evidence and patient preferences. They embed evidence‐based guidelines into daily clinical practice and provide mechanisms to share evidence‐based guidelines and information with patients to encourage their participation. They may involve the use of proven provider education methods or seek to integrate specialist expertise and primary care.

4. Clinical information system interventions

Interventions involving clinical information systems, generally computerised medical records systems, aim to organise patient and population data to facilitate care, provide timely reminders for providers and patients, identify relevant subpopulations for proactive care, facilitate individual care planning, share information with patients and providers to co‐ordinate care, and monitor performance of the practice team and care system as a whole. For example, in audiology this might include the introduction of electronic patient records that facilitate the development of individual management plans or identify patients in need of routine review or follow‐up.

5. Community interventions

Interventions falling into this category include those that mobilise community resources to meet the needs of patients, encourage patients to participate in community‐based programmes or where partnerships have been formed with community organisations to support and develop interventions that fill gaps in services or advocate for policies to improve patient care. In audiology this might include partnerships with local deaf clubs or community volunteers who visit patients in their own homes.

6. Health system interventions

Health system interventions seek to create a culture, organisation and mechanisms to promote safe, high‐quality care or visibly support improvement at all levels of the organisation, beginning with the senior leader. They may involve the introduction of policies that encourage open and systematic handling of quality problems or provide incentives based on quality of care. Health system interventions may also seek to develop agreements that facilitate care co‐ordination within and across organisations. Examples from hearing health care would include the introduction of the Improving Quality in Physiological Diagnostic Services (IQIPS) programme.

See Column 1, Table 4.

1. Intervention range and type.

| CCM element | Study reference | Hearing healthcare intervention | Control intervention | Self‐management support (SMS) subtype | Delivery system design (DSD) format | Delivery system design (DSD) intensity | Delivery system design (DSD) mode | Subgroup(s) compared |

| Health system | None found | — | ||||||

| Community resources | None found | |||||||

| Decision support | None found | |||||||

| Clinical information system | None found | |||||||

| Delivery system design | Campos 2013 | Remote online fitting | Face‐to‐face fitting | Activate ‐ practical | Remote (online) versus face‐to‐face | Low | Individual | DSD format |

| Cherry 1994 | Telephone follow‐up at 6, 9 and 12 weeks post‐fitting ‐ questions answered, trouble‐shooting and counselling | Face‐to‐face follow‐up on request | Activate ‐ symptom | Telephone versus face‐to‐face | Medium versus low | Individual | DSD format and intensity | |

| Collins 2013 | 60‐minute group orientation with PowerPoint presentation covering use, care and maintenance of the hearing aid | 30‐minute individual orientation with handout of same PowerPoint presentation | Advise | Face‐to‐face | Low | Group versus individual | DSD mode | |

| Cunningham 2001 | As many post‐fitting adjustments as patients requested | No post‐fitting adjustments | Activate ‐ symptom | Face‐to‐face | Medium versus low | Individual | DSD intensity | |

| Lavie 2014 | Simultaneous binaural fitting | Sequential binaural fitting | Activate ‐ practical | Face‐to‐face but simultaneous versus sequential | Low | Individual | DSD format | |

| Ward 1981 | Self‐help book on hearing tactics | Single session face‐to‐face advice on hearing tactics | Advise | Booklet versus face‐to‐face | Low | Individual | DSD format | |

| Self‐management support | Fitzpatrick 2008 | Auditory training ‐ phoneme discrimination in single words, then sentences and then in presence of background noise. 13 x 1 hour | 13 x 1‐hour lectures on hearing loss, hearing aids and communication | Activate ‐ symptom versus advise | Face‐to‐face | High | Individual | SMS content |

| Kricos 1996 | 4‐week communication training programme 8 x 1‐hour including information and practice in communication skills and coping strategies for communication | 8 x 1‐hour analytic auditory training | Activate ‐ psychosocial versus symptom | Face‐to‐face | High | Individual | SMS content | |

| Preminger 2010a | 6 x 1‐hour group communication strategy training plus psychosocial exercises addressing emotional and psychological impact of hearing loss | 6 x 1‐hour group communication strategy training | Activate ‐ psychosocial+ versus psychosocial | Face‐to‐face | High | Group | SMS content | |

| Saunders 2009 | Pre‐fitting counselling including demo | Pre‐fitting counselling with no demo | Activate ‐ symptom versus none | Face‐to‐face | Low | Individual | SMS content | |

| Saunders 2016 | 20 x 30‐minute sessions auditory training (LACE) over a 4‐week period on PC at home | 20 x 30‐minute sessions over a 4‐week period listening to an audio book (placebo) | Activate ‐ symptom versus none | Remote | High | Individual | SMS content | |

| Combined SMS/DSD | Abrams 1992 | Group AR 90 minutes once a week for 3 weeks post‐fitting. Each week lectures covering different topics relating to hearing loss and communication | No intervention post‐fitting | Advise | Face‐to‐face | Medium | Group | SMS content DSD format DSD intensity DSD mode |

| Andersson 1994 | 60‐minute individual behavioural counselling session then 3 consecutive weeks of group or individual sessions where hearing tactics and coping strategies were taught and practised | No intervention post‐fitting | Activate ‐ psychosocial | Face‐to‐face | Medium | Group or Individual | SMS content DSD format DSD intensity DSD mode |

|

| Andersson 1995 | 60‐minute individual behavioural counselling session then 4 x 2‐hour sessions including video feedback on role play, applied relaxation, information and homework | No intervention | Activate ‐ psychosocial | Face‐to‐face | High | Individual | SMS content DSD format DSD intensity |

|

| Andersson 1997 | Self‐help manual supplied with 1‐hour face‐to‐face training session including relaxation training followed by telephone contact over 4 consecutive weeks | No intervention | Activate ‐ psychosocial | Face‐to‐face | High | Individual | SMS content DSD intensity |

|

| Beynon 1997 | 4‐week communication course ‐ information and discussion regarding hearing loss, hearing aids and communication | No intervention | Advise | Face‐to‐face | Medium | Group versus individual | SMS content DSD intensity DSD mode |

|

| Chisolm 2004 | 4‐week course AR ‐ 2 hours per week with lectures covering different aspects relating to hearing loss and communication | No intervention | Advise | Face‐to‐face | Medium | Group versus Individual | SMS content DSD intensity DSD mode |

|

| Eriksson‐Mangold 1990 | 5 visits including fitting ‐ structured guidance, use of diary with specific homework tasks, restricted HA use during first month | Standard fitting | Activate ‐ psychosocial | Face‐to‐face | High | Individual | SMS content DSD intensity |

|

| Ferguson 2016 | Interactive DVD to use at home following fitting including information and exercises on hearing aid management and communication | Standard fitting | Activate ‐ practical and psychosocial | Remote (DVD/PC/online) | Medium | Individual | SMS content DSD format DSD intensity |

|

| Gil 2010 | 8 x 1‐hour twice a week for 4 weeks ‐ synthetic ‐ pointing to words, figures, digits and verbal repetition | No intervention | Activate ‐ symptom | Face‐to‐face | High | Individual | SMS content DSD intensity |

|

| Kemker 2004 | 2 x 1‐hour sessions of hearing aid orientation ‐ could be pre‐ or post‐fitting. In the review we combined these groups | No intervention | Advise | Face‐to‐face | Medium | Individual | SMS content DSD intensity |

|

| Kramer 2005 | 5 sequential videos showing listening situations and coping tactics | No intervention | Advise | Remote (video) | High | Individual | SMS content DSD format DSD intensity |

|

| Kricos 1992 | 4‐week communication training programme 8 x 1‐hour including information and practice in communication skills and coping strategies for communication | No intervention | Activate ‐ psychosocial | Face‐to‐face | High | Individual | SMS content DSD intensity |

|

| Kricos 1996 | 4‐week communication training programme 8 x 1‐hour including information and practice in communication skills and coping strategies for communication | No intervention | Activate ‐ psychosocial | Face‐to‐face | High | Individual | SMS content DSD intensity |

|

| Lundberg 2011 | Weekly topic‐based reading tasks based on an information booklet plus 5 x 10‐ to 15‐minute telephone calls with an audiologist to discuss the tasks | Information booklet | Activate ‐ psychosocial versus advise | Telephone | High | Individual | SMS content DSD format DSD intensity |

|

| Miranda 2008 | 7 x 50‐minute weekly session of auditory training ‐ mix of synthetic and analytic | No intervention | Activate ‐ symptom | Face‐to‐face | High | Individual | SMS content DSD intensity |

|

| Oberg 2008 | Pre‐fitting sound awareness training. 3 visits with different listening exercises. 1 visit without amplification and 2 with an experimental adjustable aid | No intervention | Activate ‐ symptom | Face‐to‐face | Medium | Individual | SMS content DSD intensity |

|

| Oberg 2009 | Pre‐fitting use of an experimental adjustable hearing aid ‐ 3 clinic visits to adjust the aid a week apart and experience at home in between | No intervention | Activate ‐ symptom | Face‐to‐face | Medium | Individual | SMS content DSD intensity |

|

| Olson 2013 | 20 x 30‐minute sessions at home over 4 weeks using interactive DVD delivering synthetic auditory tasks | No intervention | Activate ‐ symptom | Remote (DVD) | High | Individual | SMS content DSD format DSD intensity |

|

| Preminger 2008 | 6 x 1‐hour speech training classes including auditory and audiovisual analytic and synthetic tasks | No intervention | Activate ‐ symptom | Face‐to‐face | High | Group versus None | SMS content DSD intensity DSD mode |

|

| Preminger 2010 | Group AR plus separate group for SPs 4 x 90 minutes | Group AR without group for SPs | Advise | Face‐to‐face | Medium | Group | SMS content DSD intensity |

|

| Saunders 2016 | 10 x 30‐minute auditory training sessions delivered by DVD at home over a 2‐week period OR 20 x 30‐minute auditory training sessions delivered by PC at home over a 4‐week period |

No intervention | Activate ‐ symptom | Remote (DVD or PC based) | High | Individual | SMS content DSD intensity |

|

| Smaldino 1988 | 4 sessions of rehabilitation including information on hearing and hearing aids, practice and problem‐solving regarding communication and role play | No intervention | Activate ‐ psychosocial | Remote (PC‐based) | Medium | Individual | SMS content DSD intensity |

|

| Sweetow 2006 | 30 minutes 5 days a week for 4 weeks at home analytic and synthetic auditory training, information on communication strategies | No intervention | Activate ‐ symptom | Remote (PC‐based) | High | Individual | SMS content DSD format DSD intensity |

|

| Thoren 2011 | 5‐week online education programme including information, tasks assignments and professional contact via email | Online discussion forum with 5 weekly topics but no task assignments and no professional guidance | Advise versus Activate ‐ psychosocial | Remote (email follow‐up) | High | Individual | SMS content DSD format DSD intensity |

|

| Thoren 2014 | 5‐week online rehabilitation programme including self‐study, training and professional coaching in hearing physiology, hearing aids, and communication strategies as well as online contact with peers | No intervention | Activate ‐ psychosocial | Remote | High | Individual | SMS content DSD format DSD intensity |

|

| Turbin 2006 | Single session of group AR ‐ length not clear | No intervention | Advise | Face‐to‐face | Low | Group versus Individual | SMS content DSD intensity DSD mode |

|

| Vreeken 2015 | Weekly home visits for 3 to 5 weeks. Participants received a handbook with background information and a checklist accompanied with exercises covering: hearing aid use, maintenance and handling; living environment; hearing assistive devices; communication strategies | No intervention | Activate ‐ psychosocial | Face‐to‐face plus booklet | High | Individual | SMS content DSD format DSD intensity |

|

| Ward 1978 | 2 treatment groups ‐ 1 received 2 x 2‐hour AR sessions, the other 4 x 2‐hour sessions. Sessions including physical practice with aids and communication advice and practice. Also psychosocial aspects | No intervention | Activate ‐ psychosocial | Face‐to‐face | Medium | Group | SMS content DSD intensity DSD mode |

|

| Ward 1981 | Self‐help book on hearing tactics | No intervention | Advise | Booklet | Low | Individual | SMS content DSD format DSD intensity |

|

AR: auditory rehabilitation CCM: chronic care model DSD: delivery system design HA: hearing aid SMS: self‐management support SP: spouse

We recognise that within each of these elements there will be clinical diversity in the type of intervention delivered and we therefore planned to investigate this diversity with subgroup analyses where appropriate. However, we felt it would of interest to policy‐makers to know the relative effects of different interventions grouped by element so that they can make an informed judgement about whether it is more cost‐effective to make changes in intervention content (e.g. self‐management support), how that content is delivered (delivery system design) or in how delivery is supported (decision support, clinical information system).

How the intervention might work

1. Self‐management support interventions

These interventions act directly to promote behaviour change on the part of the patient. The behaviour change of primary interest in this review is increased hearing aid use. This might be achieved through:

improving knowledge (advice);

practising new skills ‐ practical, symptom management and psychosocial management skills (assist through activation/engagement);

providing self‐management resources and tools (assist through resource provision);

collaborating in decision‐making (agree).

We recognised that these subtypes of self‐management support may have an impact on behaviour to different extents and we explored this further with subgroup analyses (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

2. Delivery system design interventions

Delivery system design interventions work by making changes in the system to facilitate the delivery of self‐management support through:

reorganisation of staff roles;

restructuring of care delivery.

In terms of clinical outcomes for patients, delivery system design interventions therefore have a less direct mode of action than self‐management support interventions. They do not act directly to change patient behaviour but facilitate the delivery of interventions that do.

3. Decision support interventions

Decision support interventions work by promoting behaviour change on the part of the clinician. Again these have an indirect impact on patient behaviour. They work by providing the clinician with the knowledge and skills they need to provide self‐management support as effectively as possible.

4. Clinical information system interventions

Again these have an indirect action on patient behaviour. These interventions work by using organising data to facilitate effective self‐management support.

5. Community interventions

These interventions work by using resources within the wider community either by supporting the patient directly or by helping the health system function so that self‐management support can be provided more effectively.

6. Health system interventions

How health system interventions work is complex, context‐specific and less easy to quantify (Kreindler 2009). Tsai 2005 also noted that health system interventions are difficult to manipulate empirically and that evidence is hard to find across the spectrum of long‐term conditions.

Since the action and implementation of community and health system interventions cross the boundary between the direct healthcare patient‐provider environment into the wider healthcare system and policy environment, we did not plan to carry out a detailed meta‐analysis of effects for these two elements. Instead we documented whether any studies tested this type of intervention.

Why it is important to do this review

Researchers have argued that the negative consequences of hearing loss make a strong argument for early, effective hearing aid fitting (Arlinger 2003). Interventions that improve rates of hearing aid use should have an impact on such negative psychosocial consequences, both on an individual level and across the population with hearing loss who have been fitted with hearing aids.

In addition, if uptake of hearing aids is increased by the use of screening or education programmes (Davis 2007; Thodi 2013), then it is important that subsequent hearing aid fitting is as effective as possible. There are also economic implications of non‐use, both for national funding bodies and on an individual level for those purchasing their own hearing aids.

This review does not aim to compare the effects of context‐specific interventions (e.g. auditory training, communication training) or modes of delivery (e.g. group versus individual interventions). However, adult hearing loss is an under‐researched, under‐theorised field. Hence we have employed a framework from the wider field of long‐term conditions research and service development. We hope that this framework will provide information about high‐level intervention types such as those that act directly to support patient behaviour change and those that seek to influence patient behaviour in less direct ways. However, we also hope to provide another level of detail using subgroup analyses for those stakeholders interested in, for example, subtypes of self‐management support. We hope that by structuring the review in this way we will be able to encourage new research directions and highlight gaps in the evidence base.

Objectives

To assess the long‐term effectiveness of interventions to promote the use of hearing aids in adults with acquired hearing loss fitted with at least one hearing aid.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that fulfilled the inclusion criteria. We included quasi‐randomised trials such as those allocating by an arbitrary but not truly random process (e.g. day of the week) and cluster‐randomised trials.

Types of participants

Adults with hearing loss greater than 25 dB hearing level (HL) in the better ear averaged across four frequencies (0.5 kHz, 1 kHz, 2 kHz and 4 kHz) who were fitted with a hearing aid for at least one ear. This is consistent with World Health Organization criteria for the definition of hearing loss (WHO 2000), and includes those with mild, moderate, severe and profound losses. Studies on the acceptability and benefit of hearing screening sometimes set different criteria for what constitutes a significant hearing loss (e.g. Davis 2007). These are generally more conservative and so would be included under the definition given above. Where trials did not give details of hearing levels for participants we assumed that those fitted with a hearing aid would have met these criteria. For the purposes of this review we considered adults to be aged 18 years and over. Trials that included participants under the age of 18 were included if the data for adults could be accessed separately by contacting the authors where it was not obvious from the trial data. We included adults with sensorineural, conductive and mixed hearing losses. We excluded trials that included participants using implantable devices such as bone‐anchored hearing aids or cochlear implants.

Types of interventions

This review considered any healthcare interventions, classified according to the chronic care model (CCM), intended to increase the use of hearing aids. We excluded studies that tested or compared developments in hearing aid technology (see Description of the intervention).

Comparisons

Self‐management support interventions versus alternative interventions that control for other elements delivery method/pattern.

Delivery system design interventions versus alternative interventions that control for content.

Combined self‐management support/delivery system design interventions versus standard care/control.

Decision support interventions versus standard care.

Clinical information system interventions versus standard care.

We planned to include subgroup analyses by self‐management support content, delivery system design format and follow‐up schedule (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

Interventions were compared against each other, against no intervention or against 'standard care'. This review considered interventions supplementary to the hearing aid fitting process itself. We defined standard care as being a face‐to‐face individual hearing aid fitting typically lasting 45 to 60 minutes. We would expect a standard fitting to include a basic level of advice regarding use and management of the hearing aid with some practice at physical management of the device itself.

Types of outcome measures

The purpose of this review was to look at interventions that promote use of hearing aids once they have been fitted either by increasing the proportion of those fitted who become successful users or by increasing the amount of use per person. We recognise that for an individual use does not always equate to benefit but it is certainly a necessary starting point. At the most basic level it is not possible to benefit from a hearing aid if it is not in use for at least a proportion of the time.

As hearing loss is a long‐term condition and hearing aids are usually intended as a long‐term intervention, we were interested in hearing aid use after a follow‐up period of at least a year. We also included short‐term (</ = 12 weeks) and medium‐term (> 12 to < 52 weeks) follow‐up, but we considered this lower quality evidence than if long‐term data were available for the same outcome.

Primary outcomes

1. Hearing aid use

The purpose of this review was to assess the degree to which any of the interventions described above resulted in the increased usage of hearing aids by the patient. This may be measured in many different ways (Perez 2012). This review uses the following measures:

1.1. Adherence (i.e. the proportion of participants who continued to use their hearing aids after fitting relative to the total number fitted). The World Health Organization defines adherence as "the extent to which a person's behaviour – taking medication, following a diet, and/or executing lifestyle changes, corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health care provider" (WHO 2003). This definition differs from purely behavioural definitions of use (is the patient wearing their hearing aid?) and compliance (is the patient wearing their hearing aid as recommended?). For the purposes of this review we assumed that those being fitted with a hearing aid had agreed to this management option. We have therefore defined number of aids in use/number fitted as adherence. Participants were classified as users or non‐users. Users were defined as those who used their hearing aids on at least a weekly basis. Non‐users were those who did not use their hearing aids at all or those who had not used their hearing aid for at least a week prior to follow‐up data collection. Where it was unclear how often participants were using their hearing aids and how they had been classified as users or non‐users, we attempted to contact the study authors for clarification. If we were unable to get clarification the study was excluded.

1.2. Daily hours of hearing aid use. This may be assessed using validated self‐report measures that record the daily hours of hearing aid use or data‐logging by the hearing aid itself. Modern hearing aids have the capacity to capture and record when the hearing aid is switched on. It does not represent a true objective measure of use because it is only able to measure whether the hearing aid is switched on and the acoustic environment it is in, not whether it is switched on and in the patient's ear. However, we hoped to use it as a proxy measure of use. Both data collection methods yield continuous data either in terms of hours of use/time or proportion of the time the hearing aid(s) are worn. Since it is not the purpose of this review to compare methods of data collection, we combined data obtained using self‐report and data‐logging in our analyses of daily hours of hearing aid use.

2. Adverse effects

2.1 Inappropriate advice/clinical practice causing damage to patients' hearing.

2.2 Patient complaints:

unresolved problems with physical management of the hearing aid;

unresolved issues with symptom or psychosocial management;

complaints relating to the nature of the intervention itself, such as having to make repeat visits to the clinic.

Secondary outcomes

For the purposes of this review we were interested in additional patient‐reported outcomes that might be theoretically related to hearing aid use. Additional process‐related outcomes such as utilisation, quality of care and resource use are outside the scope of this review.

We included validated measures of:

quality of life ‐ we included validated generic (e.g. SF‐36, SF‐12) and disease‐specific measures of quality of life (e.g. IOI‐HA item 7 Cox 2002);

hearing handicap ‐ validated measures of residual handicap or activity limitations (e.g. Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly (HHIE) (Ventry 1982), Hearing Coping Assessment (HCA) (Andersson 1995a), Hearing Measurement Scale (HMS) (Noble 1970), Hearing Performance Inventory (HPI) (Giolas 1979), QDS (Alpiner 1978), IOI‐HA item 3);

hearing aid benefit ‐ validated measures of hearing aid benefit (e.g. Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (APHAB) (Cox 1995), Glasgow Hearing Aid Benefit Profile (GHABP) (Gatehouse 1999), IOI‐HA item 2);

communication ‐ any validated measure of communication ability or strategy (e.g. Communication Profile for the Hearing Impaired (CPHI) (Demorest 1987)).

These measures might be completed by the patient, their communication partner(s) or both, with or without supervision from a clinician. We selected the outcomes we considered would be of most interest to patients, clinicians and policy‐makers as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We reached the decision on which outcomes to include a priori following discussion between FB, EM and LE, who all have clinical experience in the context of hearing health care.

Search methods for identification of studies

The Cochrane ENT Information Specialist conducted systematic searches for randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials. There were no language, publication year or publication status restrictions. The date of the search was 13 June 2016.

Electronic searches

The Information Specialist searched:

the Cochrane ENT Trials Register (searched 20 June 2016);

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2016, Issue 5);

PubMed (1946 to 13 June 2016);

Ovid EMBASE (1974 to 2016 June 10);

Ovid CAB Abstracts (1910 to 2016 week 22);

EBSCO CINAHL (1982 to 13 June 2016);

Ovid AMED (1985 to 13 June 2016);

LILACS, lilacs.bvsalud.org (searched 13 June 2016);

KoreaMed (searched via Google Scholar 13 June 2016);

IndMed, www.indmed.nic.in (searched 13 June 2016);

PakMediNet, www.pakmedinet.com (searched 13 June 2016);

Web of Knowledge, Web of Science (1945 to 13 June 2016);

CNKI, www.cnki.com.cn (searched via Google Scholar 13 June 2016);

ClinicalTrials.gov (searched via the Cochrane Register of Studies 13 June 2016);

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), www.who.int/ictrp (searched 13 June 2016);

ISRCTN, www.isrctn.com (searched 13 June 2016);

Google Scholar, scholar.google.co.uk (searched 17 June 2016);

Google, www.google.com (searched 17 June 2016).

The Information Specialist modelled subject strategies for databases on the search strategy designed for CENTRAL. Where appropriate, they were combined with subject strategy adaptations of the highly sensitive search strategy designed by Cochrane for identifying randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials (as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0, Box 6.4.b. (Higgins 2011). Search strategies for major databases including CENTRAL are provided in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We scanned the reference lists of identified publications for additional trials. We searched PubMed, The Cochrane Library and Google to retrieve existing systematic reviews relevant to this systematic review, so that we could scan their reference lists for additional trials. We searched for conference abstracts using the Cochrane ENT Trials Register.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Material downloaded from electronic sources included details of author, institution or journal of publication and abstract. FB and EM inspected all reports independently in order to ensure reliable selection. We resolved any disagreement by discussion and, where there was still doubt, we acquired the full article for further inspection. Once the full articles were obtained, we decided whether the studies met the review criteria. If disagreement could not be resolved by discussion, we sought further information and added these trials to the list of those awaiting assessment.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction

Review authors FB and LE independently extracted data from all included studies. Again, we discussed any disagreement, documented decisions and, if necessary, contacted authors of studies for clarification. We extracted data presented only in graphs and figures whenever possible, but included them only if two review authors independently came to the same result. We attempted to contact authors through an open‐ended request in order to obtain missing information or for clarification whenever necessary. If studies were multicentre, where possible, we extracted data relevant to each component centre separately.

Data management

Forms

We extracted data onto standard, simple forms, which are available on request from the corresponding author.

Scale‐derived data

We included ordinal data from rating scales only if:

the psychometric properties of the measuring instrument had been described in a peer‐reviewed journal; and

the measuring instrument had not been written or modified by one of the investigators for that particular trial.

We considered the ideal measuring instrument to be either i) self‐report or ii) completed by an independent rater or relative (not the clinician).

Endpoint versus change data

There are advantages of both endpoint and change data. Change data can remove a component of between‐person variability from the analysis. On the other hand, calculation of change needs two assessments (baseline and endpoint), which increases the likelihood of missing data points. We primarily used endpoint data and only used change data if the former were not available. Where appropriate we used standardised mean differences to combine endpoint and change data in the analyses (Higgins 2011).

Skewed data

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, we applied the following standards to all data before inclusion:

standard deviations and means were reported in the paper or obtainable from the authors;

when a scale started from zero, the mean should be more than twice the standard deviation (as otherwise the mean was unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution (Altman 1996);

if a scale started from a positive value we modified the calculation described above to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew was present if 2SD>(S‐S min), where S is the mean score and S min is the minimum score.

Endpoint scores on scales often had a finite start and endpoint and these rules could be applied. We entered potentially skewed endpoint data from studies into our analyses but noted the high risk of skew, downgrading our judgement of the quality of the evidence for a particular outcome where the majority of studies were at high risk of bias.

When continuous data were presented on a scale that included a possibility of negative values (such as change data) and it was difficult to tell whether data were skewed or not, we entered change data but again noted where we considered it to be of potential significance when interpreting the evidence.

Common measure

To facilitate comparison between trials, we converted variables that were reported in different metrics, such as hours of use (mean hours per day, per week or per month) to a common metric. We used mean hours per day. For conversion purposes we considered a full day to equal 12 hours since hearing aids are not normally worn at night.

Direction of graphs

For outcomes where a higher score was judged to be a positive outcome (such as daily hours of use or quality of life), we displayed the results so that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for the control group. For outcomes where a higher score was judged to be a negative outcome (such as hearing handicap), we displayed the results so that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for the intervention group.

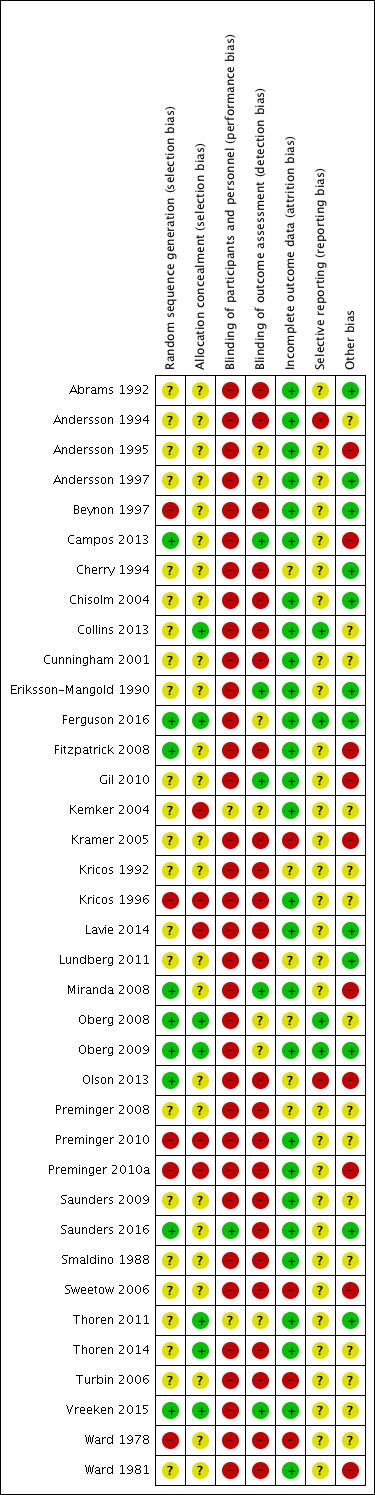

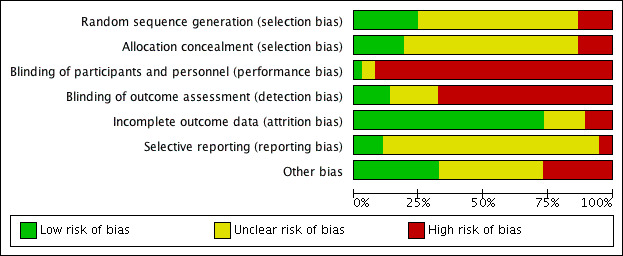

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Authors FB and EM independently undertook an assessment of the risk of bias of the included trials as guided by theCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). This set of criteria is based on evidence of associations between overestimate of effect and high risk of bias of the article such as sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting.

We used the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool in RevMan 5.3 (RevMan 2014), which involves describing each of the domains as reported in the trial and then assigning a judgement about the adequacy of each entry: 'low', 'high' or 'unclear' risk of bias. We judged that any study that had a high risk of bias in three or more areas had an overall high risk of bias and we subjected those to a sensitivity analysis (see Sensitivity analysis).

Where the raters disagreed, we made the final rating by consensus, with the involvement of another member of the review group. Where inadequate details of randomisation and other characteristics of trials were provided, we attempted to contact authors of the studies in order to obtain further information. We recorded non‐concurrence in quality assessment and, where there was disagreement as to which category a trial was to be allocated, again we resolved this by discussion.

We noted the level of risk of bias in both the text of the review and in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

Measures of treatment effect

Binary data

For binary outcomes we calculated a standard estimation of the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). It has been shown that the RR is more intuitive than the odds ratio (Boissel 1999), and additionally that odds ratios tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000). Where we identified heterogeneity we planned to used a random‐effects model.

Continuous data

If continuous data, for example from hearing aid benefit questionnaires, were measured on the same scale, we used the mean difference to summarise the results between studies. For outcomes measured using different scales, we calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD) to combine the results.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster trials

We anticipated that some studies might employ 'cluster‐randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice) and we planned for how we would deal with this statistically to reduce the risk of 'unit of analysis' errors (Divine 1992). In the event no trials involving cluster‐randomisation were included in this review.

2. Cross‐over trials

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence, on entry to the second phase the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash‐out phase. For the same reason cross‐over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable or progressive. As both these possibilities arise with hearing loss, we sought to use only data from the first phase of cross‐over studies.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involved more than two treatment arms, if relevant, we presented the additional treatment arms in comparisons. If data were binary we added and combined these within the two‐by‐two table. If data were continuous we combined data following the formula in section 7.7.3.8 ('Combining groups') of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions where appropriate (Higgins 2011). Where the additional treatment arms were not relevant, we did not use these data.

Dealing with missing data

Overall loss of credibility

At some degree of loss of follow‐up data must lose credibility. We decided that, for any particular outcome, should more than 50% of data be unaccounted for, we would not present these data or use them within analyses. If, however, more than 50% of those in one arm of a study were lost, but the total loss was less than 50%, we marked such data with (*) to indicate that such a result may well be prone to bias.

Binary

In the case where attrition for a binary outcome was between 0% and 50% and where these data were not clearly described, we presented data on a 'once randomised always analyse' basis (an intention‐to‐treat analysis). We assumed those leaving the study early to have the same rates of negative outcome as those who completed. We planned to undertake a sensitivity analysis to test how prone the primary outcomes are to change when data only from people who completed the study to that point were compared with the intention‐to‐treat analysis using the above assumption.

Continuous

Attrition

In the case where attrition for a continuous outcome was between 0% and 50% we reported data only from people who completed the study to that point.

Standard deviations

If standard deviations were not reported, we first tried to obtain the missing values from the authors. If not available, where there were missing measures of variance for continuous data, but an exact standard error and confidence intervals were available for group means, and either P value or t value were available for differences in mean, we calculated them according to the rules described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). When only the standard error (SE) was reported, we attempted to calculate standard deviations (SDs) by the formula SD = SE * square root (n). Chapters 7.7.3 and 16.1.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions present detailed formulae for estimating SDs from P values, t or F values, confidence intervals, ranges or other statistics (Higgins 2011).

Last observation carried forward

We anticipated that in some studies the method of last observation carried forward (LOCF) might be employed within the study report. As with all methods of imputation to deal with missing data, LOCF introduces uncertainty about the reliability of the results. Therefore, where LOCF data were used in a trial, if less than 50% of the data was assumed, we presented and used these data and indicated that they are the product of LOCF assumptions.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Clinical diversity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to look for variations in participants, interventions and outcomes (clinical diversity). We inspected all studies for clearly outlying people or situations that we had not predicted would arise. We planned theory‐led subgroup analyses based on CCM element definitions and long‐term conditions research (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

Methodological diversity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to look for variability in study design and risk of bias (methodological diversity). We inspected all studies for clearly outlying methods that we had not predicted would arise.

Statistical heterogeneity

Heterogeneity may arise as a result of clinical or methodological diversity, or both. We assessed it in two ways.

Visual inspection

We visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity by looking at the degree of overlap between confidence intervals.

Employing the I2 statistic

We investigated heterogeneity between studies by considering the I2 statistic alongside the Chi2 test P value. The I2 statistic provides an estimate of the percentage of inconsistency thought to be due to chance. The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on i) the magnitude and direction of effects and ii) the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P value from Chi2 test, or a confidence interval for I2). We have interpreted an I2 estimate greater than or equal to around 50% accompanied by a statistically significant Chi2 value as evidence of substantial levels of heterogeneity (Section 9.5.2 ‐ Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Egger 1997). These are described in section 10.1 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Protocol versus full study

We attempted to locate protocols for included randomised trials. If the protocol was available, we compared outcomes in the protocol and in the published report. If the protocol was not available, we compared outcomes listed in the methods section of the trial report with the results actually reported.

Funnel plot

We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small study effects. We did not use funnel plots for outcomes where there were 10 or fewer studies, or where all studies were of similar sizes.

Data synthesis

Fixed‐effect models hold that only within‐study variation influences the uncertainty of an effect (as reflected in the confidence interval). Variation between the estimates of effect from each study (heterogeneity) does not influence the confidence interval in a fixed‐effect model. Random‐effects models incorporate an assumption that the different studies are estimating different (yet related) but not fixed intervention effects.

In a group of studies where there is low heterogeneity, fixed‐effect and random‐effects models will return the similar confidence intervals. However, where there is evidence of statistical heterogeneity this will be taken into account only by a random‐effects model analysis and the confidence intervals will be wider than they would be when analysing the same data using a fixed‐effect model. In terms of identifying evidence of significant effects a random‐effects model is therefore more conservative. However, it does put more weight on the smaller studies, which are often the most biased. Depending on the direction of effect these studies can either inflate or deflate effect size.

Since we anticipated a degree of clinical and methodological heterogeneity in these data, given the wide range of interventions included, we used a random‐effects model for all analyses. To investigate heterogeneity further, where appropriate, we carried out a series of theory‐led subgroup analyses based on the CCM element definitions and previous research carried out in other long‐term conditions and we assessed risk of bias (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses

In this review, we have grouped the results into comparisons within the CCM element. We anticipated that there would be diversity of intervention within a CCM element (see Description of the intervention) and so we planned to use the CCM element definitions and previous research analysing complex interventions in long‐term conditions to perform subgroup analyses where appropriate.