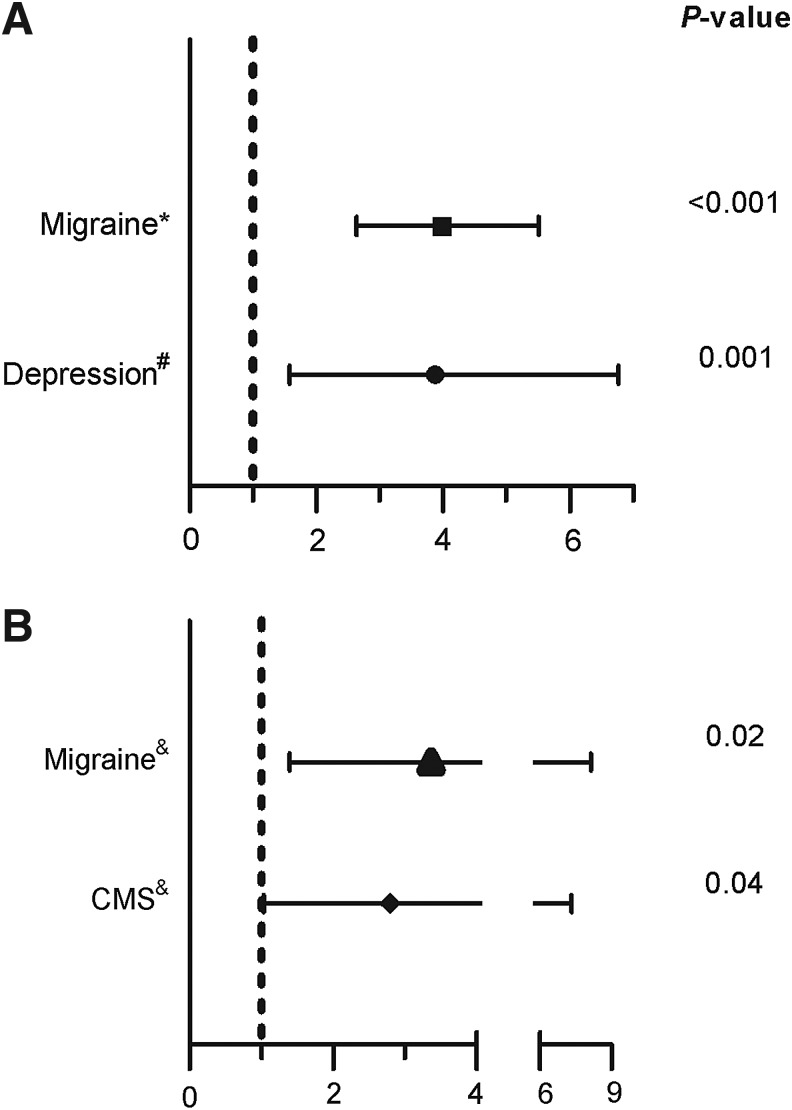

Hypoxia is characteristic of living at high altitude. Animal and human studies have shown that chronic hypoxia is associated with changes in the brain. Neurological symptoms are common in high altitude populations. Headaches, paresthesias, physical and mental fatigue have been described at high altitude (Arregui et al 1991; Appenzeller et al. 2002; Winslow and Monge 1987). Furthermore, these symptoms are frequent in Monge's disease or chronic mountain sickness (CMS), a disease that develops after many years of residing at high altitude. It is characterized by excessive erythrocytosis, hypoxemia, headache, dizziness, tinnitus, breathlessness, sleep disturbances, physical and mental fatigue and dilation of the veins (Winslow and Monge 1987). Notable among CMS symptoms is migraine headache, which is particularly frequent at high altitude, being approximately 4 times more frequent than sea level populations 1 (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Odds ratios for high altitude and neuropsychiatric symptoms. (A). High altitude is associated with the presence of migraine and depression. The rates of migraine and depression were compared in high altitude and sea level natives. (B). At high altitude (4300 m) depression is associated with the occurrence of migraine and chronic mountain sickness (CMS). Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated from Arregui et al. 1991*, Arregui 1995#, and Arregui et al 1995& using 2×2 contigency tables through StatCalc utility software (Epi Info 2010, CDC Atlanta, Georgia).

The recent retrospective study by Brenner et al. (2011) involving most U.S. counties, which spanned 20 years, reported a dramatic increase of suicide in high altitude populations. This finding was independent of demographic factors usually associated with suicide such as age, race, gender, or income. The higher suicide rate at high altitude is not explained by increased overall mortality since there is a negative correlation between altitude and overall mortality. Previous findings from our group may shed some light on this finding (Arregui 1995; Arregui et al 1995). Using epidemiological surveys we described an increased prevalence of depression in men living at high altitude compared with those living at sea level (see Fig 1A). Moreover, migraines and CMS occur more frequently at high altitude. In addition, depression is associated with the presence of migraines and CMS at high altitude (Arregui et al 1995) (see Fig 1B). Depression is responsible for the majority of suicide cases worldwide (Henriksson et al. 1993). Therefore, increased depression prevalence at high altitude populations may explain the association of increased suicide rate at high altitude (Brenner et al. 2011). Currently, the contribution of migraine in the association between suicide and high altitude is not entirely clear. However, migraine is also a risk factor for psychiatric disorders, including depression (Pompili et al. 2010). Both, depression and migraine are associated with serotonin related abnormalities, and both are part of the chronic mountain sickness symptomatology. However, further research is warranted. Another potential explanation for the association between suicide and high altitude is that people who are depressed preferentially migrate to the highlands. Due to the higher prevalence of depression at high altitude we will expect a measurable migration rate from sea level to the high altitude. Nevertheless, at least in Peru, there is an opposite trend, people from high altitude migrate to coastline cities (Instituto Nacional de Estadistica e Informatica, 1995).

Noteworthy, chronic hypoxia is associated with changes in monoamine systems including dopamine and serotonin (Arregui et al. 1994; Davis and Carlsson 1973). For instance, striatum dopamine uptake sites are increased in mice exposed to 14 days of hypoxia (Arregui et al. 1994). Additionally, concentrations of the serotonin metabolite 5-hydroxy indolacetic acid (5-HIAA) are reduced in the striatum and hypothalamus (Saligout et al. 1986), frontal cortex, pons and medulla of rats exposed to chronic hypoxia (Ray et al. 2011). Dopamine and serotonin are known to play a central role in the pathophysiology and treatment of depression (Dunlop and Nemeroff 2007; Carr and Lucki 2010). It is possible that these neurotransmitter alterations might be related to changes in neuronal energetic metabolism, particularly, reduction of mitochondrial respiration, as previously described in chronic hypoxia (Hochachka et al. 1994; Chavez et al. 1995; Caceda et al. 2001). Interestingly, it has been recently suggested that mitochondrial dysfunction may play role in depression (Burroughs and French 2007; Lucca et al. 2009).

The coexistence of depression, migraine and CMS does not appear to be a random association (Arregui et al. 1995). Hypobaric hypoxia increases the hematocrit, but may also be the cause of neurologic symptoms and mood disorders. Depression is responsible for most suicide cases and it is reasonable to suggest that the correlation between suicide and altitude found by Brenner et al. (2011) is due to a high prevalence of depression. Prospective studies are required to establish the relation between depression, high altitude and suicide. These studies are also relevant at sea level in conditions such as sleep apnea and chronic pulmonary diseases, where hypoxia play a major pathogenic role.

References

- 1.Arregui A. Cabrera J. Leon-Velarde F. Paredes S. Viscarra D. Arbaiza D. High prevalence of migraine in a high altitude population. Neurology. 1991;41:1668. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.10.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appenzeller O. Thomas PK. Ponsford S. Gamboa JL. Caceda R. Milner P. Acral paresthesias in the Andes and neurology at sea level. Neurology. 2002;59:1532–1535. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000034761.86543.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winslow RM. Monge C. Hypoxia, Polycythemia and Chronic Mountain Sickness. Baltimore: John Hopkins Press; 1987. Chronic mountain sickness. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenner B. Cheng D. Clark S. Camargo CA. Positive association between altitude and suicide in 2584 U.S. counties. High Alt Med Biol. 2011;12:30–35. doi: 10.1089/ham.2010.1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arregui A. Is depression more frequent in the altitude? A pilot study. Rev Med Hered. 1995;6:182–186. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arregui A. Cabrera J. Leon-Velarde F. Vizcarra D. Umeres H. Acosta R. Paredes S. Chronic mountain sickness, migraine and depression: Causal or fortuitous coexistence? Possible role of hypoxic environment. Rev Med Hered. 1995;6:163–167. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henriksson MM. Aro HM. Marttunen MJ. Heikkinen ME. Isometsa ET. Kuoppasalmi KI. Lonnqvist JK. Mental disorders and comorbidity in suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:935–940. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.6.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pompili M. Serafini G. Di CD. Dominici G. Innamorati M. Lester D. Forte A. Girardi N. De FS. Tatarelli R. Martelletti P. Psychiatric comorbidity and suicide risk in patients with chronic migraine. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2010;6:81–91. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s8467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Instituto Nacional de Estadistica e Informatica. Migraciones internas en el Peru. 1995. http://www.inei.gob.pe/biblioineipub/bancopub/Est/Lib0018/cap31003.htm http://www.inei.gob.pe/biblioineipub/bancopub/Est/Lib0018/cap31003.htm

- 10.Arregui A. Hollingsworth Z. Penney JB. Young AB. Autoradiographic evidence for increased dopamine uptake sites in striatum of hypoxic mice. Neuroscience Letters. 1994;167:195–197. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)91060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis JN. Carlsson A. The effect of hypoxia on monoamine synthesis, levels and metabolism in rat brain. J Neurochem. 1973;21:783–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1973.tb07522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saligaut C. Chretien P. Daoust M. Moore N. Boismare F. Dynamic characteristics of dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin metabolism in axonal endings of the rat hypothalamus and striatum during hypoxia: a study using HPLC with electrochemical detection. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 1986;8:343–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ray K. Dutta A. Panjwani U. Thakur L. Anand JP. Kumar S. Hypobaric hypoxia modulates brain biogenic amines and disturbs sleep architecture. Neurochem International. 2011;58:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunlop BW. Nemeroff CB. The role of dopamine in the pathophysiology of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:327–337. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carr GV. Lucki I. The role of serotonin in depression. In: Christian PMaB., editor. Handbook of Behavioral Neuroscience. Handbook of the Behavioral Neurobiology of Serotonin. Vol. 21. Elsevier; 2010. pp. 493–505. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hochachka PW. Clark CM. Brown WD. Stanley C. Stone CK. Nickles RJ. Zhu GG. Allen PS. Holden JE. The brain at high altitude: Hypometabolism as a defense against chronic hypoxia? J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1994;14:671–679. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1994.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chavez JC. Pichiule P. Boero J. Arregui A. Reduced mitochondrial respiration in mouse cerebral cortex during chronic hypoxia. Neurosci Lett. 1995;193:169–172. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11692-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caceda R. Gamboa JL. Boero JA. Monge C. Arregui A. Energetic metabolism in mouse cerebral cortex during chronic hypoxia. Neurosci Lett. 2001;301:171–174. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01630-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burroughs S. French D. Depression and anxiety: Role of mitochondria. Current Anesth Crit Care. 2007;18:34–41. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lucca G. Comim CM. Valvassori SS. Réus GZ. Vuolo F. Petronilho F. Gavioli EC. Dal-Pizzol F. Quevedo J. Increased oxidative stress in submitochondrial particles into the brain of rats submitted to the chronic mild stress paradigm. J Psychiatric Res. 2009;43:864–869. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]