Abstract

Previously we increased the potency of therapeutic antibodies in targeting, induction of apoptosis, and growth inhibition in vitro and in vivo by chemically conjugating a homophilic peptide to the antibody. Here, we describe the construction of a chimeric fusion gene derived from the murine anti-CD20 antibody (1F5) variable region, with an engineered homophilic domain at the C-terminus of the human IgG1 sequence. The construct was expressed in CHO suspension cells and purified. The potency of the homophilic anti-CD20 antibody was compared to a chimeric antibody without the engineered homophilic domain. In this comparison, the homophilic anti-CD20 antibody showed increased binding to a human CD20 cell line, and significantly more ADCC, CDC, and induction of apoptosis in three cell lines. In addition, the homophilic anti-CD20 antibody demonstrated increased inhibition of proliferation of two cell lines. These data show that homophilic fusion protein antibodies with enhanced therapeutic potency can be produced with industry-standard fermentation protocols.

Introduction

For therapeutic application of antibodies, potency is a decisive factor that affects the therapeutic response in patients undergoing immune therapy. Significant efforts have been made to augment the therapeutic potency of antibodies by increasing the affinity for the target,(1) as well as modifying carbohydrate(2,3) and Fc effector binding sites.(4,5) However, there are practical limits to how much affinity can be improved.(6–8) High-affinity antibodies may be less effective than medium-affinity antibodies, because high-affinity antibodies exhibit a decreased rate of diffusion,(9) and affinity is not predictive of anti-proliferative activity.(10) Classical mechanisms invoked in therapeutic potency are CDC, ADCC, and blockage of growth receptors. Induction of apoptosis has recently been recognized as an important mechanism of tumor killing.(11,12) Apoptosis is initiated by cross-linking of receptors that trigger apoptotic signaling pathways.(11,12) For example, Vitteta and colleagues have made chemically cross-linked dimmers of anti-CD20 and anti-CD19 antibodies, and have shown that these dimerized antibodies are superior in vitro and in vivo compared to the monomeric forms.(13) Other chemical and immunological techniques producing polyvalent antibodies have produced similar potency enhancement(14) or as a tetravalent F(ab’)2.(15)

Our laboratory has developed a method that produces dimerizing antibodies and has shown that they possess significantly higher potency in vitro and in vivo, targeting human and mouse tumors.(16,17) Homophilic antibodies, naturally occurring or engineered, are in equilibrium between monomeric and multimeric forms. In solution, homophilic antibodies behave as monomeric structures, but after attachment to a target, they exert their homophilic potential.(18) This mechanism has several biological implications. First, it increases the density of antibodies on its target, an important parameter for Fc-mediated mechanisms. Second, homophilic antibodies can induce targeted receptor cross-linking, a mechanism known to induce apoptosis. Third, induced receptor cross-linking can lead to uptake and internalization of the antibody-receptor complex. All three mechanisms may affect the therapeutic potency of antibodies.(19)

The potency-enhancing peptide is derived from naturally occurring, self-binding T15 antibodies(20–22) and confers homophilic properties to virtually any antibody. Although chemical modification has proven very effective, it presents a challenge for large-scale production of therapeutic antibodies. For this reason, we have employed molecular biological techniques to generate recombinant homophilic antibodies to satisfy the requirements for production, quality control, and FDA requirements.

Previously, we have generated such homophilic antibodies with improved potency using the Fc carbohydrate site or a photochemical affinity cross-linking method. The photochemical technology is based on the discovery of affinity sites on antibodies that can be used to photo cross-link peptides. Both methods are simple and effective in conjugating a peptide of interest to antibodies(23) and crosslink several peptides to one antibody molecule at different positions. It was important to determine that similar potency enhancements can be achieved with a peptide fusion protein in which one peptide is ligated to the C-terminus of the heavy chain, producing a fusion antibody with only two peptides.

Given the success of Rituxan™ in treating non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) and its recent approval for use in rheumatoid arthritis, we have chosen CD20 as a therapeutic target. CD20 is an important B-cell marker, since it is present at high levels in various B cell cancers, but is undetectable in precursor and plasma B cells.(24) Although chemical peptide cross-linking has proven very effective, it presents a challenge for large-scale production of therapeutic antibodies. For this reason, we have employed molecular biological techniques to generate recombinant homophilic antibodies to satisfy the requirements for production, quality control, and FDA regulations.

In this report, we compare the potencies of an anti-CD20 chimeric antibody with its homophilic recombinant chimeric version. We demonstrate that the recombinant homophilic anti-CD20 has increased effector functions versus the chimeric antibody without the homophilic domain. In general, homophilic antibodies via their increased target cellular targets may be low expressed, more effective, and with higher potent effector functions. The described recombinant approach of generating hemophilic antibodies provides a blueprint to produce a novel class of therapeutic antibodies.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines

JOK-1 cells were a gift of Affimed, Inc. (Heidelberg, DE). JOK-1 cells were grown in RPMI-1640 with Glutamax (Gibco, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), supplemented with 10% FBS-Premium-HI (Aleken Biologicals, Nash, TX), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco). 1F5 hybridoma, Raji, and Ramos cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA), numbers HB-9645, CCL-86, CRL-1596, and TIB-152, respectively. Raji and Ramos cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium with HEPES (ATCC), supplemented with 10% FBS-Premium-HI (Aleken Biologicals), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco). 1F5 cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium with HEPES (ATCC), supplemented with 10% FBS-low-IgG (Gibco), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco), and 0.5% Glutamax (Gibco).

CHO-S cells were purchased from Invitrogen, (Carlsbad, CA) and were grown in CD CHO medium, supplemented with 1% HT supplement, 2% Glutamax, and 100 U/mL pen/strep (all from Gibco). After introduction of vector DNA, CHO-S cells were grown as above with the addition of 1.2 mg/mL G418 (Invivogen, San Diego, CA) for selection. All cells were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Construction of chimeric antibody genes

Total RNA was isolated from ∼7×106 1F5 hybridoma cells using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. First strand cDNA synthesis, cDNA amplification by Long-Distance PCR (LD-PCR), and Proteinase K digestion were carried out using the materials and protocol of the Creator SMART cDNA library kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). The 1F5 heavy chain variable regions were amplified from the cDNA pool by PCR using primers modVH1F5fwd and modVH1F5rev. All oligos were purchased from Operon (Huntsville, AL). The 1F5 light chain variable regions were amplified from the cDNA pool by PCR using primers modVL1F5fwd and modVL1F5rev. The heavy chain and light chain PCR products were cloned into the XhoI-NheI and SacI-HindIII sites, respectively, of vector pAc-k-CH3 (Progen Biotechnik, Heidelberg, DE) to form pAc-k-1F5H and pAc-k-1F5K. Clones were verified by sequencing in both directions. All restriction enzymes were purchased from Takara or New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). Taq polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI) was used for all PCR. All enzymatic reactions were carried out using the manufacturers' protocols.

Construction of antibody expression vectors

Oligos LongT15fwd, LongT15rev, and PrimerB were used in a nested PCR, similar to the method of Horton,(27) to construct a DNA sequence that encodes the T15 peptide. The resulting PCR product was cloned into the SalI-NotI sites in MCSB of pIRES (Clontech) to form p homophilic. The complete heavy and light chains of pAc-k-1F5H and pAc-k-1F5K were PCR amplified using primers modVHXfwd and modVHXrev, or VKXfwd and VKXrev, respectively. The light chain was cloned into the NheI-XhoI sites of MCSA of vector homophilic, and the heavy chain was cloned into the SalI-NotI sites of the resulting vector to form pch1F5-homophilic. Clones were verified by sequencing in both directions. To produce pch1F5 (anti-CD20 without the T15 peptide), pch1F5-homophilic and pIRES were digested with NotI and ClaI. Resulting DNA fragments of ∼6 Kb from pch1F5-homophilic and ∼2.2 Kb from pIRES were each gel purified from a 1% agarose gel using a Qiaquick kit (Qiagen) and ligated together to form pch1F5. Clones were verified by sequencing in both directions. All vector constructs were introduced into Escherichia coli (XL-10 cells from Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) using the provided heat shock protocols. Plasmids were purified from 3 mL of overnight bacterial culture using a mini-prep kit (Qiagen). Vectors pch1F5 and pch1F5-homophilic were electroporated into CHO-S cells using a 4 mm gap cuvette in an Eppendorf Multiporator (Westbury, NY) set to 580 V and ms. Two days of recovery were allowed before the start of selection.

Purification of recombinant antibodies

Cell culture supernatant was harvested every 3–5 days, depending on cell density. Cell suspensions were centrifuged at low speed (480–740g) for 7 to 10 min, and the supernatant was held at−20°C prior to additional processing. After rapid thawing at 37°C, supernatant was passed through a 0.2 μm filter (Corning) by vacuum filtration to remove cell debris, and filtered supernatant was then passed over HiTrap Protein G HP column (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden). Bound antibodies were eluted with 0.1 M glycine buffer (pH 2.7), collected in 1 mL fractions, and the pH was neutralized with 50 μL 1 M Tris (pH 9.0). Elution profile was determined by reading UV absorbance at 280 (data not shown). Fractions with significant protein content were then pooled and concentrated using Amicon Ultra centrifugal filtration device 50,000 MW cutoff (Millipore, Danvers, MA) according to the manufacture's instructions.

Cell surface binding

3×105/well of Raji, Ramos, or JOK-1 cells were seeded in a 24-well plate and incubated overnight at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were then harvested and washed twice with PBS. Cells were resuspended in 1 mL PBS and were incubated with either ch1F5 or homophilic ch1F5 at increasing concentrations (1 μg, 5 μg, 10 μg, 20 μg/mL) and incubated at 4°C for 30 min. Excess antibody was removed by washing cells twice with PBS, and then cells were resuspended in a 1 mL solution of FITC conjugated goat anti-human (1:1000; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and incubated at 4°C for 30 min. After washing twice, cells were resuspended in 200 μL PBS and analyzed by flow cytometry (BD FACSCalibur Instrument, BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA). Specific mean fluorescence intensity was determined by using the following formula: specific MFI=MFI (primary Ab+goat anti-human FITC) – MFI (goat anti-human FITC).

Apoptosis assay

2×105/well of Raji, Ramos, or JOK-1 cells were seeded in a 24-well plate and incubated overnight at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were then treated with increasing concentrations of antibodies for 20 h at 37°C. Cells were harvested, washed once with PBS, and resuspended with 100 μL 1X annexin binding buffer containing 3 μL annexin V Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate (Invitrogen) and propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich) at a final concentration of 4 μg/mL to detect apoptosis and cell death, respectively. After 20 min incubation at 37°C, cells were diluted with 150 μL of 1X annexin binding buffer and analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur Instrument, BD Bioscience). Percent apoptotic cells was determined by gating the healthy population in the untreated control samples and using the following formula: percent apoptotic cells=(1 – (live treated target cells/live untreated target cells)) * 100.

CDC assay

2×105 cells were seeded into a 24-well plate and incubated overnight at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were then treated with increasing concentrations of antibodies for 2 h at 37°C in the presence of 5% rabbit HLA-ABC complement-enriched sera (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were harvested and washed once with PBS and resuspended in 200 μL of PBS containing 50 nM calcein-AM (Biochemika, Sigma-Aldrich) and 4 μg/mL propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich). After incubation for 20 min at 37°C, cell viability was analyzed by flow cytometry. Percent killing was determined by the following formula: percent dead cells=(1 – (live treated target cells/live untreated 8 target cells)) * 100.

PBMC separation

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were prepared from healthy donors' buffy coat (Kentucky Blood Center, Lexington, KY) by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation. PBMC were diluted to 6×106 cells/mL in hRPMI (10% FBS, low IgG) culture media) and maintained for a maximum of 3 days. PBMC viability and day-to-day cell population variation was analyzed by flow cytometry before experimentation.

ADCC assay

Target cells (Raji, Ramos, or JOK-1) were harvested from T75 flasks and resuspended in 1 mL of media containing 400 nM calcein-AM (Biochemika, Sigma-Aldrich) and 8 μL of TFL2 dye (OncoImmunin, Gaithersburg, MD), used according to manufacturer's instructions. Target cells were labeled for 45 min at 37°C, washed twice in media, and resuspended to a density of 6×105 cells/mL. Effector cells (PBMC) were then harvested from T75 flasks and resuspended to a density of 1.2×107 cells/mL. Target cells and effector cells were mixed at an E/T ratio of 20:1 then 250 μL of cell mixture was aliquoted into individual 5 mL round-bottom tubes and incubated with increasing concentrations of antibodies for 2 h at 37°C. After incubation, target cell viability was analyzed by flow cytometry. Percent killing was determined by the formula, percent dead cells=(1 – (live treated target cells/live untreated target cells)) * 100.

Anti-proliferation assay

5×103 cells per well of Raji or Ramos cells were seeded into a 96-well plate and treated with decreasing concentrations of antibodies. Cells were incubated for 6 days at 37°C and 5% CO2. At the end of the 6 days, cells were centrifuged at low speed (450g) for 7 min. Supernatant was removed and cells were resuspended with 100 μL Cyquant NF DNA binding dye reagent (Invitrogen) for 45 min at 37°C. Fluorescence was measured using a Synergy 2 microplate reader (Biotek, Winooski, VT), emission 485 nm and excitation 530 nm. Higher fluorescence is indicative of cell proliferation.

Results

Construction of ch1F5 and ch1F5-homophilic antibodies

Several groups have demonstrated that cross-linking of therapeutic antibodies can improve the antibody's ability to kill target cells. These cross-linking methods include addition of secondary antibody, chemical cross-linking, and molecular engineering of multimeric forms.(13,15–17, 25) We have previously shown that peptides can be photochemically added to affinity sites on antibodies,(23) and that photochemical addition of a specific peptide to antibodies can induce cross-linking in situ, producing homophilic antibodies. To further test the capacity of the homophilic peptide, we have used molecular biological techniques to generate a chimeric version of the murine 1F5 antibody (ch1F5), and we have generated a chimeric homophilic antibody that is identical to ch1F5, except for the addition of the homophilic peptide to the C-terminus of each heavy chain. Figure 1 shows a drawing of the structures of ch1F5 and ch1F5-homophilic.

FIG. 1.

Schematic of antibody structure, with and without T15 homophilic.

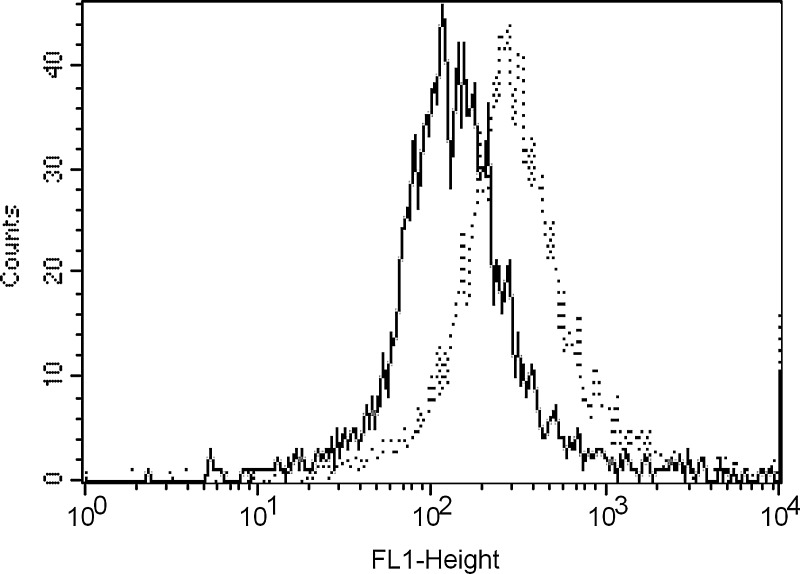

Binding to human B cell lines using FACS

To verify that the recombinant ch1F5 and ch1F5-homophilic antibodies are functional, we tested their ability to bind to cells from the human B-cell JOK-1 line, using fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS). In Figure 2, the dotted line shows the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of staining with the ch1F5-homophilic antibody, while the solid line represents the staining using the ch1F5 non-homophilic antibody. Binding of the ch1F5-homophilic antibody was approximately four-fold greater than binding of ch1F5.

FIG. 2.

Comparison of binding 5 mg/mL 1F5 ( solid) to homophilic 1F5 (dashed) using FACS on fixed cells.

Induction of apoptosis is dependent on receptor cross-linking

One of the proposed mechanisms of homophilic antibodies is receptor cross-linked induction of apoptosis.(16,17) We compared the induction of apoptosis of the ch1F5 and homophilic antibodies in three cell lines—Raji, Ramos, and JOK-1. As seen in Figure 3, the addition of 20 mg of ch1F5 induces apoptosis in approximately 30% of the cells (Fig. 3B vs 3A). The homophilic antibody induces significantly more apoptosis than the naked chimeric (Fig. 3C vs 3B). Similarly, the homophilic antibody is a more potent inducer of apoptosis in Ramos cells at a concentration of 10 mg (Fig. 3F vs 3D,E). In Table 1 we show the apoptotic effects of the two antibodies over a range of concentrations. It is interesting to note, at lower concentration of antibodies the enhancing effect is much more pronounced. For example, after treatment of Raji cells with 5 μg/mL of either antibody, the percent of apoptotic cells is 2.5-fold higher after homophilic treatment, but it is slightly less than 2-4 fold higher after treatment with 20 mg/mL.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of induction of apoptosis by 1F5 and homophilic 1F5 on Raji (A–C) and Ramos (D–F) cells. The x-axis (FL-1) shows the intensity of annexin-V binding, while the y-axis (FL-2) refers to the intensity of propidium iodide staining. Cells were incubated for 20 h untreated (A, D), cells with 1F5 (B, E), or cells with homophilic 1F5 (C, F).

Table 1.

Apoptotic Effects of Two Antibodies over a Range of Concentrations

| Cell line | Antibody/mLa | ch1F5b | Homphilic-ch1F5c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raji | |||

| 1 μg | 0.83±2.18 | 5.06±2.16 | |

| 5 μg | 14.90±1.81 | 36.91±8.73 | |

| 10 μg | 26.73±4.28 | 47.40±2.89 | |

| 20 μg | 30.05±3.13 | 58.37±4.67 | |

| Ramos | |||

| 1 μg | 4.00±0.11 | 19.36±2.06 | |

| 5 μg | 20.11±2.30 | 33.06±7.10 | |

| 10 μg | 24.61±0.40 | 42.53±4.28 | |

| 20 μg | 31.74±1.70 | 40.79±1.41 | |

| Jok-1 | |||

| 1 μg | 7.85±0.99 | 4.39±0.99 | |

| 5 μg | 23.77±5.48 | 27.19±12.14 | |

| 10 μg | 59.43±13.89 | 52.12±18.97 | |

| 20 μg | 49.44±7.50 | 56.87±4.60 | |

Different amounts of antibodies were added for 20 hours to each cell line.

Percent apoptotic cells induced by ch1F5.

Percent apoptotic cells induced by hemophilic-ch 1F5.

Comparison of complement-dependent cytotoxicity

Next we compared the CDC activity of the ch1F5 and ch1F5-homophilic. CDC is induced after binding of complement components to the Fc region of an antibody and is potent in the IgG1 isotype, which is the isotype of the homophilic construct. An enhancing effect was observed in all cell lines. As seen in Figure 4A, for example, at 5 mg/mL there was virtually no CDC activity in Raji cells with the chimeric; however, 35% of cells were killed with the homophilic antibody. This correlates to the greatest improvement of effectiveness in apoptosis. It is interesting to note that the potency of the homophilic antibody plateaus at 5 mg/mL in Ramos cells (Fig. 4B). The ch1F5 appears to plateau at 10 mg /mL, but it does not reach the potency of the homophilic antibody at any level tested, suggesting that even higher doses would not reach the killing capacity of 5 mg/mL hemophilic antibody.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of CDC using ch1F5 and homophilic ch1F5. (A) Raji; (B) Ramos; (C) JOK-1. Error bars show the standard deviation of the mean of two or more experiments. Student's t-test (two tailed) was used to test for statistical significance. *p<0.05; **p<0.01.

Comparison of ADCC

Since Type I antibodies, such as the murine 1F5, do not induce high levels of ADCC activity,(26) it was interesting to test the chimeric antibody in its ability to induce ADCC. As shown in Figure 5A and B, the homophilic antibody induces significantly more ADCC than ch1F5 in Raji and Ramos cells at 1 mg/mL and 3 mg/mL, but the increase in potency is not significant at 7.5 mg/mL.

FIG. 5.

Comparison of ADCC using ch1F5 and homophilic ch1F5. (A) Raji; (B) Ramos. Error bars show the standard deviation of the mean of two or more experiments. Student's t-test (two tailed) was used to test for statistical significance. *p<0.05; **p<0.01.

Inhibition of lymphoma growth in vitro

To approximate the in vivo killing potential of these anti-CD20 antibodies on tumor cells, we tested the anti-proliferative effects of the ch1F5 and ch1F5-homophilic in Raji and Ramos cell lines. The assay measures the level of fluorescence dye binding to nucleic acid (see Methods and Materials). As shown in Figure 6A and B, the homophilic antibody inhibited proliferation to a greater extent in both cell lines at all concentrations tested.

FIG. 6.

Comparison of inhibition of proliferation, (A) Raji; (B) Ramos, with ch1F5 and homophilic ch1F5.

Discussion

The novel aspect of this work is a new method of making non-covalently dimerizing, homophilic antibodies. The approach used standard techniques of molecular biology to create a fusion protein that consists of a full-length chimeric antibody and the T15 homophilic 24-mer domain.(28) There are several advantages of this method: (1) it can be applied to any antibody without risk of loss of affinity or specificity; (2) it produces a defined, single molecular product, which can be purified by standard method; and (3) the fusion antibodies of this type can be produced in large quantities using industry-standard mammalian expression systems.

Compared to antibody monomers, dimers and pentamers have increased avidity for the antigen. In situations where target expression is low, such as with Her2/neu in the majority of breast cancer patients, higher avidity can increase therapeutic potency. Potency increase can be achieved in vitro with a secondary antibody against the primary antibody to facilitate cross-linking; however this method is not suitable for therapeutic applications.(12) Vitetta and co-workers chemically cross-linked anti-CD19 and anti-CD20 antibodies, creating chemical homodimers and improved tumor killing in vitro and in xenograft mouse models.(13)

We have previously developed an alternative method to covalent antibody homodimers or to the use of secondary antibodies to induce tumor target cross-linking, taking advantage of a homodimerizing domain in a rare class of antibody.(18,20,22,28) This antibody contains a domain that induces dimerization upon docking to its specific target but remains monomeric in solution.(17) As previously reported, a 24-mer peptide corresponding to this domain plus a linker was affinity photo-linked to antibodies. These antibody conjugates induce enhanced effector functions in vitro(16,17,25) and in vivo.(29)

The effectiveness of covalent antibody dimers is limited because they are not able to form lattices around cellular targets, whereas non-covalent homo-dimerizing antibodies have the ability through lattice formation to cross-link low-density receptors. In addition, they can form, via self-binding, additional lattices covering the first layer of antigen-bound antibodies. The proposed mode of action of these antibodies is to induce lattice formation on target and increase receptor movement into lipid rafts, which is the initial step of signaling pathways. Facultative homodimerizing antibodies are in equilibrium between monomeric and dimeric states, whereby in physiological conditions the monomer is dominant in solution.(16,30) Upon docking to target, the equilibrium shifts to the dimer state. The term dynamic cross-linking (homophilic) describes this mechanism. Homophilic antibodies increase potency with respect to targeting, effector functions, apoptosis, and animal models.(16,17,25,29)

In this report we describe the generation of homophilic antibody against CD20 as a recombinant fusion protein. For this construct we have chosen the C-terminus as the potency of the resulting homophilic antibody. The homophilic version of the chimeric 1F5-derived antibody provides significant improvements in effector functions and apoptosis, across multiple cell lines, versus the chimeric non-homophilic antibody.

Figure 1 illustrates the placement of the T15 homophilic domain in the chimeric structure. The C-terminal attachment point assures that the homodimerizing domain does not interfere with target or complement binding; however, it may not provide optimal increase in potency. We are currently developing other constructs in which the homodimerizing domain is attached to the antibody of interest at different locations to allow direct comparison of the effect of positioning on homophilic effectiveness.

C1q binding correlates with the amount and spacing of Fc on the target cell. Our model of homophilic binding proposes lattice formation on targets, and two possible mechanisms for increased CDC. Lattice formation increases the total level of Fc available for C1q binding. In addition, the self-binding property tethers the antibodies on the cell surface into a conformation that promotes optimal spacing, which was shown to drastically enhance CDC via C1q binding.

Similarly, the homophilic anti-CD20 increases the amount of apoptosis two-fold over the “naked” anti-CD20. This agrees with the proposed mode of action in apoptosis signaling to move the antibody into lipid rafts enhanced by cross-linking.(31) Since in vitro assays of antibody potency can be unreliable predictors of patient's response, animal models using xenografts are needed to gain further confidence to initiate clinical trials with homophilic antibodies.

The present report provides a blueprint for making recombinant hemophilic antibody conjugate.(14,15,25) This sets the stage for large-scale production of recombinant homophilic antibodies using industry-standard techniques.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Xiaoping Wu for cell culture of Ramos, Raji, and JOK-1 cell lines and Mike Russ for critical comments.

Author Disclosure Statement

This work was supported in part by Innexus Biotechnology (Scottsdale, AZ).

References

- 1.Adams GP. Weiner LM. Monoclonal antibody therapy of cancer. Nat 2 Biotechnol. 2005;23:1147–1157. doi: 10.1038/nbt1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nechansky A. Schuster M. Jost W. Siegl P. Wiederkum S. Gorr G. Kircheis R. Compensation of endogenous IgG mediated inhibition of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity by glyco-engineering of therapeutic antibodies. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:1815–1817. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuster M. Umana P. Ferrara C. Brunker P. Gerdes C. Waxenecker G. Wiederkum S. Schwager C. Loibner H. Himmler G. Mudde GC. Improved effect or functions of a therapeutic monoclonal Lewis Y-specific antibody by glycolform engineering. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7934–7941. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scallon B. McCarthy S. Radewonuk J. Cai A. Naso M. Raju TS. Capocasale R. Quantitative in vivo comparisons of the Fc gamma receptor-dependent agonist activities of different fucosylation variants of an immunoglobulin G antibody. Int Immuno pharmacol. 2007;7:761–772. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scallon BJ. Tam SH. McCarthy SG. Cai AN. Raju TS. Higher levels of sialylated Fc glycans in immunoglobulin G molecules can adversely impact functionality. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:1524–1534. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foote J. Eisen HN. Breaking the affinity ceiling for antibodies and T cell receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10679–10681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.20.10679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foote J. Eisen HN. Kinetic and affinity limits on antibodies produced during immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1254–1256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rathanaswami P. Roalstad S. Roskos L. Su QJ. Lackie S. Babcook J. Demonstration of an in vivo generated sub-picomolar affinity fully human monoclonal antibody to interleukin-8. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;334:1004–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jain RK. Physiological barriers to delivery of monoclonal antibodies and other macromolecules in tumors. Cancer Res. 1990;50:814s–819s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelley RF. O'Connell MP. Carter P. Presta L. Eigenbrot C. Covarrubias M. Snedecor B. Bourell JH. Vetterlein D. Antigen binding thermodynamics and anti proliferative effects of chimeric and humanized anti-p185 HER2 antibody Fab fragments. Biochemistry. 1992;31:5434–5441. doi: 10.1021/bi00139a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shan D. Ledbetter JA. Press OW. Signaling events involved in anti-CD20-induced apoptosis of malignant human B cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2000;48:673–683. doi: 10.1007/s002620050016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shan D. Ledbetter JA. Press OW. Apoptosis of malignant human B cells by ligation of CD20 with monoclonal antibodies. Blood. 1998;91:1644–1652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghetie MA. Podar EM. Ilgen A. Gordon BE. Uhr JW. Vitetta ES. Homodimerization of tumor-reactive monoclonal antibodies markedly increases their ability to induce growth arrest or apoptosis of tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7509–7514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang H. Wang Q. Montone KT. Peavey JE. Drebin JA. Greene MI. Murali R. Shared antigenic epitopes and pathobiological functions of anti-18 p185(her2/neu) monoclonal antibodies. Exp Mol Pathol. 1999;67:15–25. doi: 10.1006/exmp.1999.2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghetie MA. Bright H. Vitetta ES. Homodimers but not monomers of Rituxan (chimeric anti-CD20) induce apoptosis in human B-lymphoma cells and synergize with a chemotherapeutic agent and an immunotoxin. Blood. 2001;97:1392–1398. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.5.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao Y. Kohler H. Enhancing tumor targeting and apoptosis using noncovalent antibody homodimers. J Immunother. 2002;25:396–404. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200209000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao Y. Lou D. Burke J. Kohler H. Enhanced anti-B-cell tumor effects with anti-CD20 superantibody. J Immunother. 2002;25:57–62. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200201000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaveri SV. Halpern R. Kang CY. Kohler H. Self-binding antibodies (autobodies) form specific complexes in solution. J Immunol. 1990;145:2533–2538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller K. Meng G. Liu J. Hurst A. Hsei V. Wong WL. Ekert R. Lawrence D. Sherwood S. DeForge L. Gaudreault J. Keller G. Sliwkowski M. Ashkenazi A. Presta L. Design, construction, and in vitro analyses of multivalent antibodies. Jlmmunol. 2003;170:4854–4861. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang CY. Brunck TK. Kieber-Emmons T. Blalock JE. Kohler H. Inhibition of self-binding antibodies (autobodies) by a VH-derived peptide. Science. 1988;240:1034–1036. doi: 10.1126/science.3368787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaveri SV. Kang CY. Kohler H. Natural mouse and human antibodies bind to a peptide derived from a germline VH chain. Evidence for evolutionary conserved self-binding locus. J Immunol. 1990;145:4207–4213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halpern R. Kaveri SV. Kohler H. Human anti-phosphorylcholine antibodies share idiotopes and are self-binding. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:476–482. doi: 10.1172/JCI115328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russ M. Lou D. Kohler H. Photo-activated affinity-site cross-linking of antibodies using tryptophan containing peptides. J Immunol Methods. 2005;304:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson KC. Bates MP. Slaughenhoupt BL. Pinkus GS. Schlossman SF. Nadler LM. Expression of human B cell-associated antigens on leukemias and lymphomas: a model of human B cell differentiation. Blood. 1984;63:1424–1433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao Y. Russ M. Retter M. Fanger G. Morgan C. Kohler H. Muller S. Endowing self-binding feature restores the activities of a loss-of-function chimerized anti-GM2 antibody. Cancer lmmunol lmmunother. 2007;56:147–154. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0182-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cragg MS. Glennie ML. Antibody specificity controls in vivo effector mechanisms of anti-CD20 reagents. Blood. 2004;103:2738–2743. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horton RM. PCR-mediated recombination and mutagenesis. SOEing together tailor-made genes. Mol Biotechnol. 1995;3:93–99. doi: 10.1007/BF02789105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kang CY. Cheng HL. Rudikoff S. Kohler H. Idiotypic self binding of a dominant germline idiotype (T15). Autobody activity is affected by antibody valency. J Exp Med. 1987;165:1332–1343. doi: 10.1084/jem.165.5.1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bryan AJ. Kohler H. Physical and biological properties of homophilic therapeutic antibodies. Cancer Immunol Immunotherapy. 2011;60:507–514. doi: 10.1007/s00262-010-0952-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohler H. Bryan AJ. Paradoxical concentration effect of a homodimerizing antibody against a human non-small cell lung cancer cell line. Cancer Immunol Immunotherapy. 2009;58:749–758. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0597-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bingaman MG. Basu GD. Golding TC. Chong SK. Lassen AJ. Kindt TJ. Lipinski CA. The autophilic anti-CD20 antibody DXL625 displays enhanced potency due to lipid raft-dependent induction of apoptosis. Anticancer Drugs. 2010:21532–21542. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e328337d485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]