Abstract

Background

Propranolol is one of the most commonly prescribed drugs for migraine prophylaxis.

Objectives

We aimed to determine whether there is evidence that propranolol is more effective than placebo and as effective as other drugs for the interval (prophylactic) treatment of patients with migraine.

Search methods

Potentially eligible studies were identified by searching MEDLINE/PubMed (1966 to May 2003) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Issue 2, 2003), and by screening bibliographies of reviews and identified articles.

Selection criteria

We included randomised and quasi‐randomised clinical trials of at least 4 weeks duration comparing clinical effects of propranolol with placebo or another drug in adult migraine sufferers.

Data collection and analysis

Two reviewers extracted information on patients, methods, interventions, outcomes measured, and results using a pre‐tested form. Study quality was assessed using two checklists (Jadad scale and Delphi list). Due to the heterogeneity of outcome measures and insufficient reporting of the data, only selective quantitative meta‐analyses were performed. As far as possible, effect size estimates were calculated for single trials. In addition, results were summarised descriptively and by a vote count among the reviewers.

Main results

A total of 58 trials with 5072 participants met the inclusion criteria. The 58 selected trials included 26 comparisons with placebo and 47 comparisons with other drugs. The methodological quality of the majority of trials was unsatisfactory. The principal shortcomings were high dropout rates and insufficient reporting and handling of this problem in the analysis. Overall, the 26 placebo‐controlled trials showed clear short‐term effects of propranolol over placebo. Due to the lack of studies with long‐term follow up, it is unclear whether these effects are stable after stopping propranolol. The 47 comparisons with calcium antagonists, other beta‐blockers, and a variety of other drugs did not yield any clear‐cut differences. Sample size was, however, insufficient in most trials to establish equivalence.

Authors' conclusions

Although many trials have relevant methodological shortcomings, there is clear evidence that propranolol is more effective than placebo in the short‐term interval treatment of migraine. Evidence on long‐term effects is lacking. Propranolol seems to be as effective and safe as a variety of other drugs used for migraine prophylaxis.

Keywords: Adult, Humans, Adrenergic beta‐Antagonists, Adrenergic beta‐Antagonists/therapeutic use, Calcium Channel Blockers, Calcium Channel Blockers/therapeutic use, Migraine Disorders, Migraine Disorders/prevention & control, Propranolol, Propranolol/therapeutic use, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Treatment Refusal

Propranolol for migraine prophylaxis

Propranolol, a beta‐blocker, is one of the most commonly prescribed drugs for the prevention of migraine. This systematic review identified 58 trials, and these provide evidence that propranolol reduces migraine frequency significantly more than placebo. We did not find any clear differences between propranolol and other migraine‐preventing drugs, but firm conclusions cannot be drawn about the relative efficacy of propranolol and other drugs due to the small sample size of most of the trials.

Background

Migraine is a common disabling condition. It typically manifests as attacks of severe, pulsating, one‐sided headache and is often accompanied by nausea, phonophobia, or photophobia. Population‐based studies from the US and elsewhere suggest that six to seven per cent of men and 15% to 18% of women experience migraine headaches (Lipton 2001; Stewart 1994). Preventive drugs are used by a small proportion of migraineurs. Available guidelines commonly recommend beta‐blockers as the first choice for migraine prophylaxis (e.g., Pryse‐Phillips 1997). It is not certain exactly how beta‐blockers decrease the frequency of migraine attacks, but they may affect the central catecholaminergic system and brain serotonin receptors.

Among the many different beta‐blockers, propranolol is one of the most commonly prescribed for migraine prophylaxis (Ramadan 1997). It has been subjected to a number of placebo‐controlled trials and is now sometimes used as a comparator drug when testing newer agents for migraine prophylaxis (Gray 1999; Holroyd 1991). While propranolol is well‐tolerated in general, it is associated with a variety of adverse effects (such as bradycardia, hypotension, bronchospasm, gastrointestinal complaints, vertigo, hypoglycaemia, etc).

Objectives

We aimed to systematically review the available randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials of propranolol for migraine prophylaxis. Specifically, we aimed to determine whether there is evidence that propranolol is:

more effective than placebo;

as effective as other pharmacological agents.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised and quasi‐randomised (using methods such as alternation) clinical trials were included. Trials that did not make an explicit statement about the allocation method, but were described as double‐blind (referring to blinding of patients and blinding of recruiting, treating, and evaluating staff), were included unless there were clear reasons to assume that allocation was not randomised.

Types of participants

Study participants were required to be adult migraine sufferers. Trials including individual participants under 18 years of age were included provided that the mean age of trial participants clearly indicated that the majority of patients were adults (e.g., if the age range was 16 to 61 years, with a mean age of 41 years). Trials conducted among patients who suffered from other types of headaches in addition to migraine were included. Trials studying patients with migraine and patients with other types of headache were included only if results for the subgroup of migraine sufferers were presented separately.

Types of interventions

Included studies were required to have at least one arm in which oral propranolol was used for migraine prophylaxis. Acceptable control groups included other migraine‐prophylactic drugs (e.g., flunarizine, metoprolol, cyclandelate) and placebo. Trials comparing only different doses of propranolol, without a non‐propranolol group, were excluded. Trials comparing propranolol solely with non‐drug interventions (e.g., biofeedback or relaxation) were also excluded.

Types of outcome measures

At least one of the following outcomes must have been measured (but not necessarily reported in sufficient detail to allow effect size calculation): number of migraine attacks, number of headache days, pain intensity, headache index, or global response. Trials reporting only physiological or laboratory parameters were excluded, as were trials focusing on the treatment of acute migraine attacks and trials with an observation period of less than 4 weeks after the start of treatment.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the following sources:

The basic search was performed in MEDLINE (1966 through September 2001) using the search terms 'propranolol or propanolol' and 'headache (exploded)' combined with the optimal search strategy for randomised controlled trials described in the Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook (Clarke 2003). To update this search, we regularly screened citations from the search 'migraine AND propranolol' in PubMed for eligible studies or reviews that might include eligible studies (last update May 2003; limited to publication date 2000 or later).

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) was searched using the terms 'propranolol or propanolol' and 'migraine or headache' (last update Issue 2, 2003).

In addition, we screened bibliographies of reviews and identified articles.

Data collection and analysis

Eligibility

One reviewer screened titles and abstracts of all references identified and excluded all citations that were clearly ineligible (e.g., trials with children or on non‐migraine headaches). Full copies of all remaining articles were obtained. Two independent reviewers then checked whether trials met inclusion criteria using a special form. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction

Two independent reviewers extracted the following information using a pre‐tested form: On the patient population:

number randomised and analysed;

diagnoses (and headache classification systems used);

age;

sex;

duration of disease;

setting.

On methods:

study design;

use of a headache diary;

duration of baseline, therapy, and follow‐up periods; for crossover studies, we also documented washout periods;

randomisation;

concealment;

handling of dropouts and withdrawals.

On interventions:

type of intervention;

dosage;

regimen;

duration.

Outcomes and results:

withdrawals and dropouts due to adverse events, lack of efficacy, or other reasons, with total number;

results for headache days, attack frequency, pain intensity, medication use, headache index, and other outcomes at baseline, after up to 4 weeks of treatment, after more than 4 weeks of treatment, and at follow‐up after completion of treatment;

number of responders, with definition of 'response';

number of patients reporting adverse events

Assessment of quality

Methodological quality was assessed using the scale by Jadad et al. (Jadad 1996) and the Delphi list (Verhagen 1998). The Jadad scale has three items and a maximum score of 5: randomisation (statement that the study was randomised = 1 point; if the method used to generate the random sequence was described, an additional point is given), double‐blinding (statement that the study was double‐blind = 1 point; additional point if a credible description of how blinding was achieved was given), and dropouts and withdrawals (a point was given if the number and reasons for dropouts and withdrawals were presented for each group separately). The Delphi list has nine questions, which concern randomisation; concealment of randomisation; baseline comparability; specification of eligibility criteria; blinding of the care provider, patients, and outcome evaluator; adequacy of reporting of main results; and analysis according to the intention‐to‐treat principle. Each question can be answered 'yes = 1', 'no = 0', or 'unclear = ?'.

In addition, the adequacy of observation and reporting of key clinical issues was assessed using a checklist developed by one of the reviewers. It included questions on: description of the sampling strategy (source of patients, recruitment); description of headache diagnoses (description of specific diagnoses, use of transparent diagnostic criteria); description of patient characteristics (age, sex, duration, baseline severity); inclusion of a baseline period (of at least 4 weeks); description of co‐interventions (amount of analgesic use); use of a headache diary; detailed presentation of data on headache frequency and intensity (central tendency, variability); completeness of follow up at 2 months (results for at least 90% of included patients 2 months after the start of treatment) and at 6 months (follow up of at least 6 months after start of the treatment, with results available for at least 80% of patients). Each item could be scored as met ('yes = 1') or not met or unclear ('no/unclear = 0').

Summarising the results

As anticipated, the reporting of the complex outcome data in the included trials was highly variable (various measurement methods, different time points) and often insufficient (lack of variance measures, unclear number of observations). The only outcomes reported in a substantial number of papers were:

various headache frequency measures (number of migraine attacks, number of migraine days, and number of headache days; mostly reported for the last 4 weeks of treatment, but sometimes for other time frames);

headache indices;

number of 'responders' (with 'response' most often defined as at least a 50% reduction in number of migraine attacks, but also sometimes as at least a 50% reduction in headache index or by global patient assessment); and

number of patients reporting adverse events.

Furthermore, a relevant proportion of trials had a crossover design and reported results only in a pooled manner for both treatment periods.

Using RevMan 4.2, we calculated standardized mean differences for headache frequency, and relative risks for number of responders, number of patients with adverse events, and number of dropouts due to adverse events for individual trials. As the measure for headache frequency we used, if available, the number of migraine attacks in the last 4 weeks or the last month of (full‐dose) treatment. However, a number of trials presented data either for different time frames (for example, 8 weeks) or for another frequency measure (migraine or headache days). For the calculation of the relative risk of response to treatment (here referred to as the 'responder ratio') we used, if available, the number of patients with a reduction of at least 50% in the number of migraine attacks. If this was not available, we used the number of patients with a reduction of at least 50% in the number of headache days, the number of patients with a reduction of at least 50% in headache index, or global response measures. In the 'Characteristics of included studies' table, we indicate which measures were actually used for each trial. As denominators we used the number of patients included in the analysis for responder ratios and the relative risk of adverse events, and the number of patients randomised for the relative risk of dropouts due to adverse events. In many instances there was uncertainty about precise numbers, for example, when only percentage values were reported for proportion of responders, with denominators not fully clear, or when the total number of patients randomised was presented but not the number randomised to each group. In other cases, standard deviations had to be calculated from standard errors or 95% confidence intervals. We tried to calculate effect sizes for single trials as often as possible despite these uncertainties. Therefore, the effect size estimates must be interpreted with caution. In the 'Characteristics of included studies' table, we generally describe the data as reported in the publications.

For effect size calculation we used, in the first instance, only data from trials with a parallel‐group design and first‐period data from those crossover studies that reported data for the first treatment period separately. As many crossover trials did not present separate data for the first treatment period, we calculated, in a second step, effect size estimates for all trials providing data, including crossover trials that reported only 'pooled' data (data from all treatment periods combined as if they were from a parallel‐group trial). If crossover trials reported both first‐period and pooled data, then we used the first‐period data for the first analyses and pooled data for the second; if crossover trials reported data only for separate phases, with no pooled data, then we used first‐period data for both analyses. Comparisons of propranolol versus placebo, versus calcium antagonists, versus other beta‐blockers, and versus other drugs were included.

In our protocol we prespecified that we would not perform quantitative meta‐analysis for a given comparison if fewer than half of the included trials provided usable data. For the comparison of propranolol versus placebo, fewer than half of the trials in fact provided sufficient data for effect size calculation. However, because the descriptive results, simple vote counts (see next paragraph), and Jadad scores were similar for trials providing data for effect size calculation and those not providing data, we decided post hoc to perform quantitative meta‐analyses for the propranolol versus placebo comparison to get at least a crude estimate of the overall effect sizes. Quantitative meta‐analyses were also performed for the comparisons with calcium antagonists and other beta‐blockers. We calculated both fixed‐effect and random‐effects estimates, but only fixed‐effect estimates (which give more weight to larger trials) are presented in the 'Results' section. Due to the heterogeneity of trials (regarding patients, dosages, observation periods, and methods for outcome measurements), the lack of detailed data for a relevant proportion of the trials, and the problem of pooled crossover data (described in the preceding paragraph), all overall effect size estimates presented below must be interpreted with great caution. Because of these problems, we did not calculate measures like numbers‐needed‐to‐treat, which suggest direct applicability of effect size estimates to routine use in practice.

Because of the difficulties with the quantitative analysis, we also provide a systematic descriptive summary of results for each study in the table on the 'Characteristics of included studies'. If available, results were summarized for the following outcomes: response, headache frequency, analgesic use, headache indices, adverse events, and dropouts due to adverse events. In addition, we performed a simple vote count to provide a crude estimate of the overall outcome of each study. For this vote count, each reviewer independently categorized the results of each study using the following scale: + = propranolol significantly better than control (primary or most clinically relevant outcome measures statistically significantly better with propranolol than with control); (+) = propranolol trend better than control (significant differences for only some clinically relevant outcomes, or no statistically significant differences, but potentially clinically relevant trends in favour of propranolol); 0 = no difference; (‐) = control trend better than propranolol; ‐ = control significantly better than propranolol. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus was reached on each study.

Results

Description of studies

We identified 96 potentially relevant publications. Seventy‐two publications describing 58 separate trials met the inclusion criteria (see table on the 'Characteristics of included studies'). One publication presented separate data on patients suffering from migraine alone and patients suffering from migraine plus interval headaches, but no analysis of all patients together; it was, therefore, analysed as two separate trials (Mathew 1981‐Study 1; Mathew 1981‐Study 2).

Twenty‐four publications were excluded: six were review articles (Amery 1988; Anonymous 1979; Montastruc 1992; Raveau‐Landon 1988; Tfelt‐Hansen 1986; Turner 1984); nine described studies that were not randomised or quasi‐randomised (Cortelli 1985; de Bock 1997; Diamond 1987; Julien 1976; Rosen 1983; Schmidt 1991; Verspeelt 1996a; Verspeelt 1996b; Wober 1991); one unblinded trial did not describe the method of allocation to groups (Steardo 1982); two trials were on the treatment of acute attacks (Banerjee 1991; Fuller 1990); one had an observation period of less than 4 weeks (Winther 1990); and five were randomised trials, but did not include placebo or another drug as a control (Carroll 1990; Havanka‐Kann. 1988; Holroyd 1995; Penzien 1990; Sovak 1981) (for details see table on the 'Characteristics of excluded studies'). We have so far been unable to obtain a copy of two articles (Bernik 1978; Rao 2000); they are categorized here as studies 'awaiting assessment'.

The 58 trials included a total of 73 comparisons relevant to this review: 26 trials included a comparison with placebo, and 40 trials included a total of 47 comparisons of propranolol with another drug. Eight trials had both a placebo and an active comparator group. Three trials additionally included comparisons of propranolol alone versus propranolol in combination with another drug, one a comparison with another propranolol dose, and one a comparison with d‐propranolol. There were 15 comparisons with calcium antagonists (10 flunarizine, three nifedipine, one nimodipine, one verapamil), 12 with other beta‐blockers (five metoprolol, five nadolol, one atenolol, one timolol), and 20 with various other agents (three amitriptyline, two femoxetine, two methysergide, two cyclandelate, two divalproex sodium, two tolfenamic acid, one dihydroergotamine, one dihydroergocryptine, one mefenamic acid, one acetylsalicylic acid, one clonidine, one 5‐hydroxytryptophan, one naproxen). Thirty‐three trials had a crossover design. The included trials were published between 1972 and 2002; four were available only as abstracts. Ten studies reported the source of funding.

The median number of patients per trial was 49 (range 9 to 810), and the total number of included patients was 5072. The proportion of patients excluded from analysis varied from zero to 50%. Eight trials were restricted to patients with migraine without aura, and one to patients with migraine with aura. Twelve studies used the International Headache Society's criteria (IHS 1988) for confirming the diagnosis, 20 the Ad Hoc Committee's criteria (Ad Hoc 1962), and nine other criteria; in 17 trials, the diagnostic criteria used were not reported. Propranolol doses ranged from 60 to 320 mg per day. Baseline periods varied from 0 to 10 weeks (median 4 weeks), and treatment phases from 4 to 30 weeks (median 12 weeks). Only a few studies included a follow‐up period after completion of treatment, and dropout rates in these studies were high, making any interpretation difficult.

Risk of bias in included studies

The Jadad score for each study is given in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table, results of the assessment with the Delphi list are reported in Table 5, and results of the assessment of the adequacy of observation are described in Table 6 and Table 7.

Table 1.

Methodological quality ‐ Delphi list

| Study | Randomisation | Concealment | Baseline comparab. | Inclusion criteria | Blind evaluators | Blind care providers | Blind patients | Reporting of results | Intent‐to‐treat |

| Ahuja 1985 | 1 | ? | ? | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ? |

| Al‐Qassab 1993 | 1 | ? | ? | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ? |

| Albers 1989 | 1 | ? | ? | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Andresson 1981 | 1 | ? | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Baldrati 1983 | 1 | ? | ? | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Behan 1980 | ? | ? | ? | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Bonuso 1998 | 1 | ? | ? | 0 | ? | ? | ? | 0 | 0 |

| Bordini 1997 | 1 | ? | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Borgesen 1974 | 1 | ? | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Dahlöf 1987 | 1 | ? | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Diamond 1976 | 1 | ? | ? | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Diamond 1982 | 1 | ? | ? | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Diener 1996 | 1 | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Diener 2002 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Diener 1989 | 1 | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ? |

| Formisano 1991 | 1 | ? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Forssman 1976 | 1 | ? | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Gawel 1991 | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Gerber 1995 | 1 | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Grotemeyer 1987 | ? | ? | ? | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Hedman 1986 | 1 | ? | ? | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Holdorff 1977 | 1 | ? | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Johnson 1986 | 1 | 1 | ? | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Kangasniemi 1983 | 1 | ? | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Kangasniemi 1984 | 1 | ? | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Kaniecki 1997 | 1 | ? | ? | 1 | ? | ? | ? | 0 | 0 |

| Kass 1980 | 1 | ? | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Kjaesgard‐Rasmussen 1994 | 1 | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ? |

| Klapper 1994 | 1 | ? | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kuritzky 1987 | 1 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | 0 | 0 |

| Lücking 1988a | 1 | ? | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Lücking 1998b | 1 | ? | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Ludin 1989 | 1 | ? | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Maissen 1985 | ? | ? | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ? |

| Malvea 1973 | 1 | ? | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Mathew 1981‐Study 1 | 1 | ? | ? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Mathew 1981‐Study 2 | 1 | ? | ? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Micieli 2001 | 1 | ? | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Mikkelsen 1986 | 1 | ? | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Nadelmann 1986 | 1 | ? | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Nicolodi 1997 | 1 | ? | ? | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ? |

| Olerud 1986 | 1 | ? | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Olsson 1984 | 1 | ? | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Palferman 1983 | 1 | ? | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Pita 1977 | 1 | ? | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Pradalier 1989 | 1 | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ? |

| Ryan 1984 | 1 | ? | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Sargent 1985 | 1 | ? | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Scholz 1987 | 1 | ? | ? | ? | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Shimell 1990 | 1 | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ? |

| Solomon 1986 | ? | ? | ? | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Stensrud 1976 | 1 | ? | ? | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Stensrud 1980 | 1 | ? | ? | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Sudilovski 1987 | 1 | ? | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Tfelt‐Hasen 1984 | 1 | ? | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Weber 1972 | 1 | ? | ? | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Wideroe 1976 | 1 | ? | ? | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Ziegler 1987 | 1 | ? | ? | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Table 2.

Adequacy of observation and reporting of key clinical issues (questions 1‐5)

| Study | Sampling described | Clear diagnosis | Patient character. | > 4 weeks baseline | Co‐interventions |

| Ahuja 1985 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Al‐Qassab 1993 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Albers 1989 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Andersson 1981 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Baldrati 1983 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Behan 1980 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bonuso 1998 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bordini 1997 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Borgesen 1974 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Dahlöf 1987 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Diamond 1976 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Diamond 1982 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Diener 1996 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Diener 2002 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Diener 1989 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Formisano 1991 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Forssman 1976 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Gawel 1992 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Gerber 1995 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Grotemeyer 1987 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hedman 1986 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Holdroff 1977 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Johnson 1986 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Kangasniemi 1983 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Kangasniemi 1984 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Kaniecki 1997 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Kass 1980 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Kjaesgard‐Rasmussen 1994 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Klapper 1994 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kuritzky 1987 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lücking 1988a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lücking 1988b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ludin 1989 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Maissen 1985 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Malvea 1973 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Mathew 1981‐study 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Mathew 1981‐study 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Micieli 2001 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Mikkelsen 1986 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nadelmann 1986 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Nicolodi 1997 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Olerud 1986 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Olsson 1984 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Palferman 1983 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pita 1977 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Pradlier 1989 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Ryan 1984 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Sargent 1985 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Scholz 1987 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Shimell 1990 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Solomon 1986 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stensrud 1976 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stensrud 1980 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sudilovsky 1987 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Tfelt‐Hansen 1984 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Weber 1972 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Wideroe 1976 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ziegler 1987 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Table 3.

Adequacy of observation and reporting of key clinical issues (questions 6‐10)

| Study | Diary used | Frequency data | Intensity data | 2‐month follow up | 6‐month follow up |

| Ahuja 1985 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Al‐Qassab 1993 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Albers 1989 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Andersson 1981 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Baldrati 1983 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Behan 1980 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bonuso 1998 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Bordini 1997 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Borgesen 1974 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dahlöf 1974 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Diamond 1976 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Diamond 1982 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Diener 1996 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Diener 2002 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Diener 1989 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Formisano 1991 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Forssman 1976 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gawel 1992 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Gerber 1995 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Grotemeyer 1987 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hedman 1986 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Holdorff 1977 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Johnson 1986 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kangasniemi 1983 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kangasniemi 1984 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Kaniecki 1997 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kass 1980 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Kjaesgard‐Rasmussen 1994 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Klapper 1994 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kuritzky 1987 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lücking 1988a | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Lücking 1988b | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Ludin 1989 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Maissen 1985 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Malvea 1973 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mathew 1981‐study 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mathew 1981‐study 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Micieli 2001 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mikkelsen 1986 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Nadelmann 1986 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Olerud 1986 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Olsson 1984 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Palferman 1983 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pita 1977 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Pradalier 1989 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ryan 1984 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Sargent 1985 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Scholz 1987 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Shimell 1990 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Solomon 1986 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stensrud 1976 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stensrud 1980 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sudilovsky 1987 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Tfelt‐Hansen 1984 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Weber 1972 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Wideroe 1976 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ziegler 1987 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nicolodi 1997 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The methodological quality of studies and the observation and reporting of key clinical issues were unsatisfactory in the majority of trials. The main shortcoming was the reporting and handling of dropouts and withdrawals. Twenty‐five studies reported numbers of and reasons for dropouts and withdrawals, but only three included an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis, even as a secondary analysis. In comparisons between active drugs, an ITT analysis would seem highly desirable as a sensitivity analysis given the high dropout rates in most studies. Only two studies adequately described allocation concealment, and none tested the success of blinding. Fifty‐one studies were described as double‐blind. The median Jadad score was 2 (range 1 to 5); the median number of criteria met on the Delphi list was 5 (range 1 to 9). A transparent description of patient recruitment was available for only nine studies. Forty‐seven trials used headache diaries, but only 29 presented detailed results (means and standard deviations, or median and ranges, etc.) for frequency measures, and 15 for intensity measures. Eleven trials had data for at least 90% of randomised patients for a period of at least 2 months, and three for 80% of patients for at least 6 months. Crossover studies rarely reported analyses of carryover or period effects.

Effects of interventions

Comparisons with placebo

Twenty‐six trials compared propranolol with placebo.

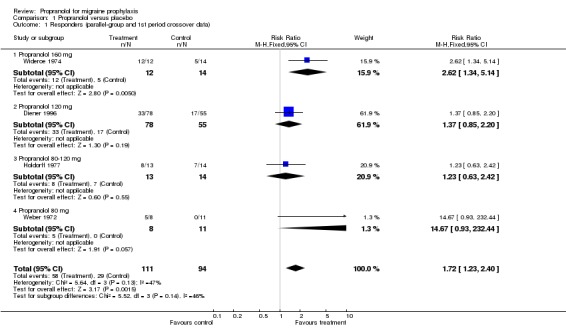

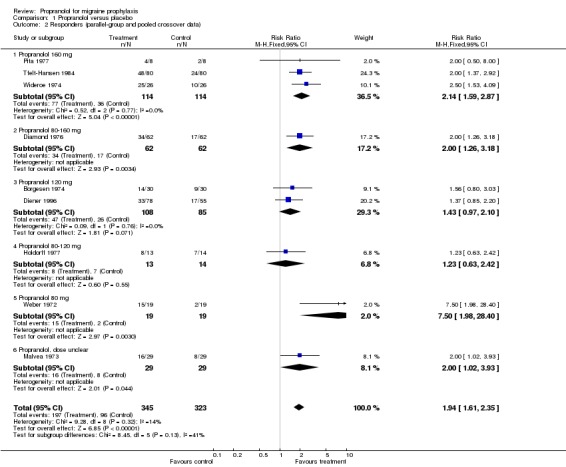

Four trials reported data on response (with variable definitions) that could be used to estimate effect sizes, nine if crossover trials with pooled data are included. In all nine trials, the proportion of responders was higher with propranolol than with placebo, and in five trials the difference between the two interventions was statistically significant. The overall relative risk of response to treatment (here called the 'responder ratio') was 1.94 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.61 to 2.35) for all nine trials (see Comparison No. 01 02), and 1.73 (95% CI 1.23 to 2.42) for the four trials with parallel‐group or first‐period crossover data (Comparison No. 01 01), indicating a significant effect of propranolol over placebo. Results were statistically rather heterogeneous (I² = 50.1%) in the set of four trials, but not in the set of nine trials (I² = 13.8%). Responder ratios tended to be higher in trials with higher dosages of propranolol, but the trial with the lowest dosage (80 mg) had the most positive result (Weber 1972).

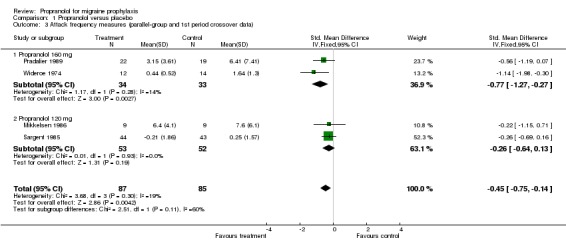

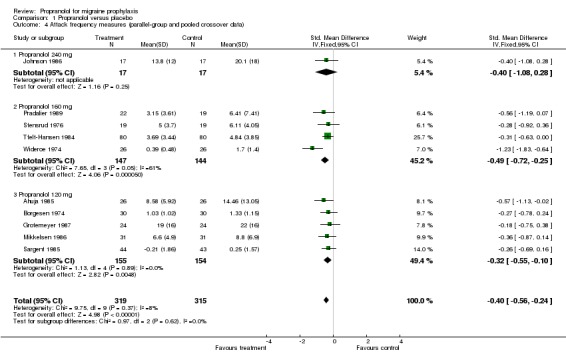

Four trials, or 10 if pooled crossover trials are included, reported sufficient data on headache frequency. Here, too, all 10 trials showed at least a trend in favour of propranolol. The overall standardized mean difference was ‐0.45 (95% CI ‐0.75 to ‐0.14) for the four trials with parallel‐group or first‐period crossover data (Comparison No. 01 03), and ‐0.40 (95% CI ‐0.56 to ‐0.24) for all 10 trials (Comparison No. 01 04). The results suggest that propranolol 160 mg may be slightly more effective than 120 mg, but the results from the four trials using 160 mg were highly heterogeneous (I² = 60.8%).

Data on headache intensity were reported inconsistently, but effects over placebo seemed minor at best. There was no consistent trend for larger effects with higher doses.

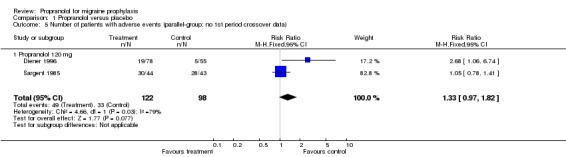

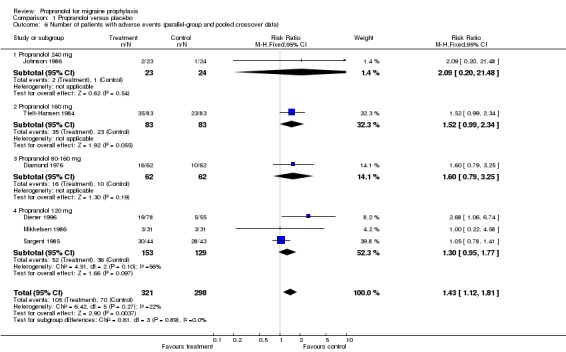

Only two trials, or six if pooled crossover trials are included, reported data on the number of patients with adverse events. Adverse events were more often reported by patients receiving propranolol (relative risk 1.33, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.82 for the two studies reporting parallel‐group or first‐period crossover data [Comparison No. 01 05]; and 1.43, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.81 for all six trials [Comparison No. 01 06]).

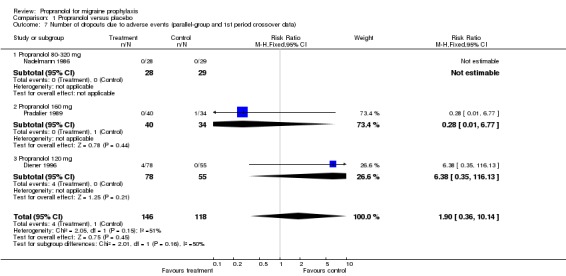

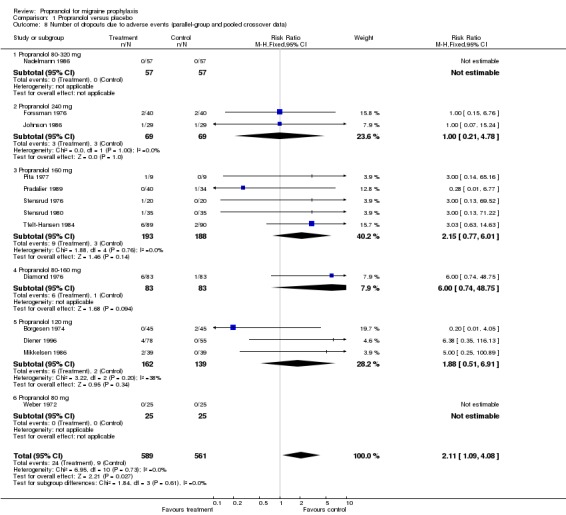

For three, respectively 13, trials the number of patients dropping out due to adverse events was reported. Patients receiving propranolol dropped out more often than patients receiving placebo (relative risk 1.90, 95% CI 0.36 to 10.14 in the three trials with parallel‐group or first‐period crossover data [Comparison No. 01 07]; and 2.11, 95% CI 1.09 to 4.08 in all 13 trials [Comparison No. 01 08]).

Both for the number of patients reporting adverse events and the number of patients dropping out due to adverse events, the results of trials with parallel‐group or first‐period crossover data were statistically highly heterogeneous (Comparisons No. 01 05 and No. 01 07), while this heterogeneity strongly decreased when pooled crossover data were considered (Comparisons No. 01 06 and No. 01 08).

The descriptive review of the placebo‐controlled trials confirms the impression that propranolol is significantly more effective than placebo, mainly by reducing headache frequency. Any effect on headache intensity seems at best minor. According to our vote count, 17 trials showed a significant superiority over placebo, seven a trend in favour of propranolol, and two no difference. All these results apply only to effects during the treatment phase (most often during the last month).

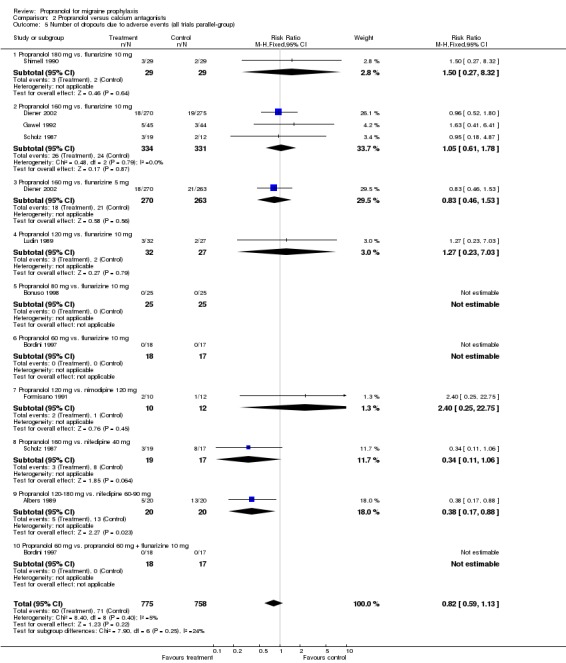

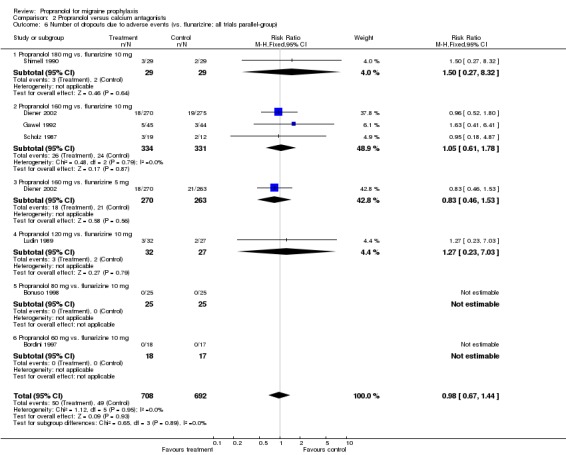

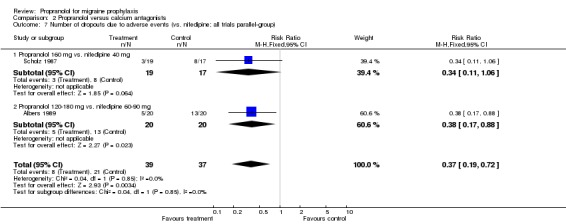

Comparisons with calcium antagonists

This category included 13 trials with 15 comparisons, plus one trial comparing propranolol alone with a combination of propranolol and flunarizine. All trials providing data for effect size calculations in this subset had a parallel‐group design.

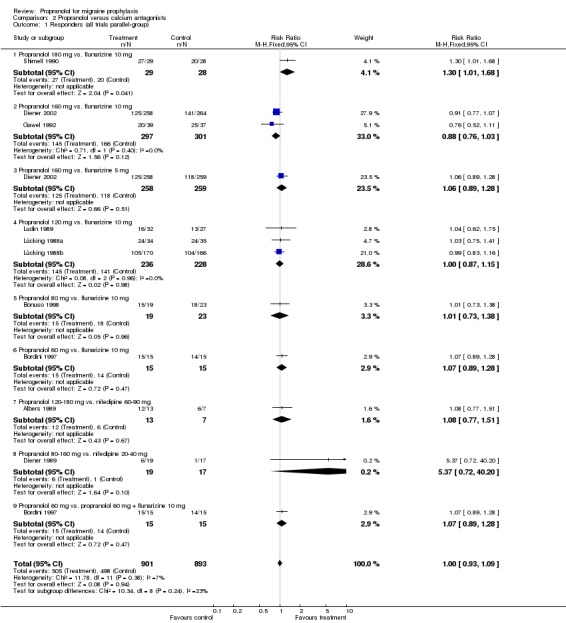

Responder data were available for 11 comparisons between propranolol in variable doses and calcium antagonists (flunarizine in nine cases), and for one comparison between propranolol alone and a combination of propranolol and flunarizine. No trial found a significant difference; in most studies response rates were very similar in both groups. The overall responder ratio was 1.00 (95% CI 0.93 to 1.09; Comparison No. 02 01).

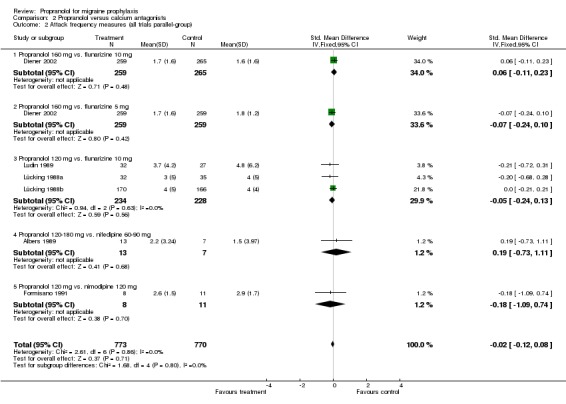

Attack frequency data were available for seven comparisons and indicated no statistically significant differences between groups. The pooled standardized mean difference was ‐0.02 (95% CI ‐0.12 to 0.08; Comparison No. 02 02).

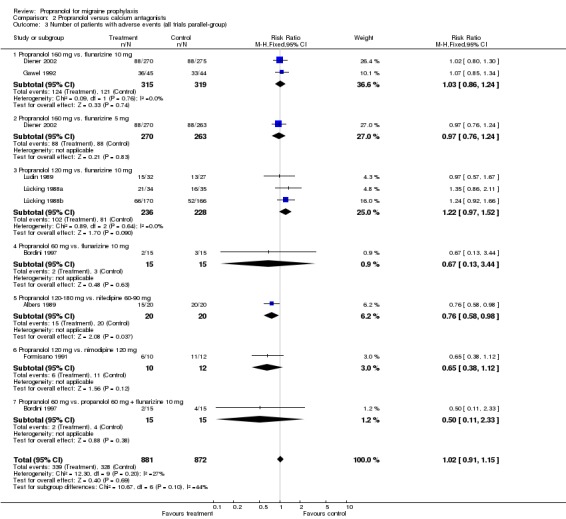

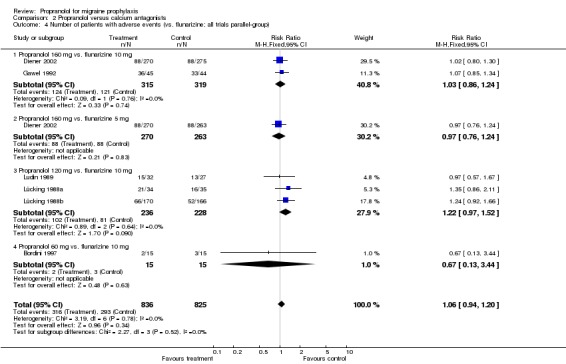

Nine trials comparing propranolol with a calcium antagonist (flunarizine in seven cases), and the trial comparing propranolol alone with a combination of propranolol and flunarizine reported the number of patients experiencing adverse events. These were similar in propranolol and flunarizine groups, but tended to be higher with nifedipine and nimodipine. The overall relative risk for all trials was 1.02 (95% CI 0.91 to 1.15; Comparison No. 02 03); for comparisons of propranolol and flunarizine, the overall relative risk was 1.06 (95% CI 0.94 to 1.20; Comparison No. 02 04).

Results were similar for the number of patients dropping out due to adverse events in the 12 trials describing this outcome (Comparison No. 02 05). The overall relative risk for trials comparing propranolol and flunarizine was 0.98 (95% CI 0.67 to 1.44; Comparison No. 02 06). Patients receiving nifedipine dropped out more often due to side effects (relative risk 0.37, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.72; Comparison No. 02 07).

The vote count yielded the following result: two comparisons with a trend in favour of propranolol, 12 showing no difference, one with a trend in favour of flunarizine, and one with a trend in favour of the combination of propranolol and flunarizine.

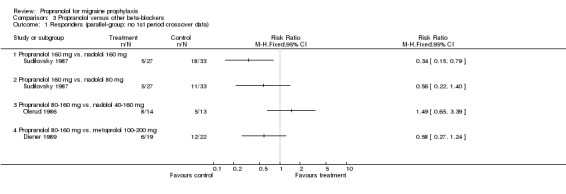

Comparisons with other beta‐blockers

This category included 10 trials with 12 comparisons, plus one trial comparing propranolol with d‐propranolol.

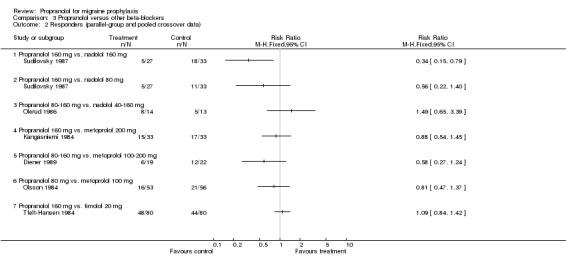

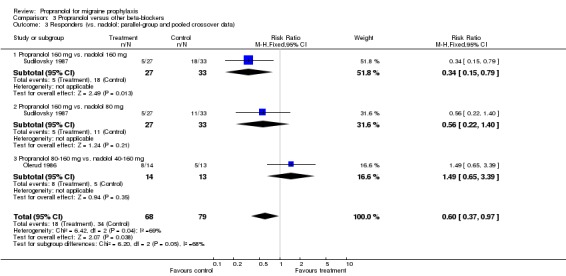

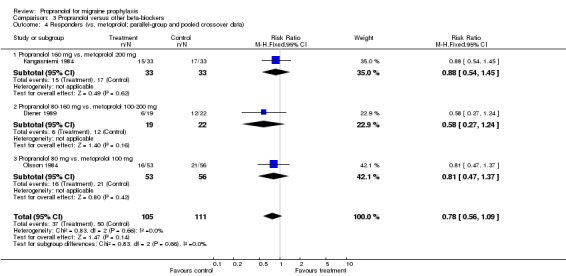

Responder data were reported for four comparisons (Comparison No. 03 01), or seven when including crossover trials with pooled data (Comparison No. 03 02). In one trial, nadolol 160 mg was significantly superior to propranolol 160 mg (Sudilovsky 1987); the other six trials did not yield significant differences. As trial results were statistically heterogeneous (I² = 53.5% for the four‐ and 48.0% for the seven‐trial set), and comparator drugs were nadolol in three trials and metoprolol in three trials, we did not combine results for all trials, but instead performed separate analyses for comparisons with nadolol (Comparison No. 03 03) and metoprolol (Comparison No. 03 04). In the three trials comparing propranolol and nadolol, the overall responder ratio favoured nadolol (0.60, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.97), but the results of the three trials were contradictory (I² = 68.8%). The three trials comparing propranolol and metoprolol had more consistent results (I² = 0%), but did not show significant differences (responder ratio 0.78, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.09).

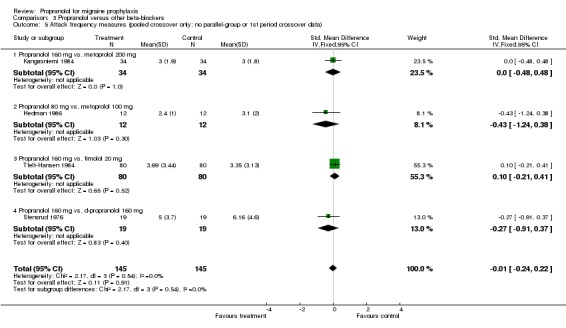

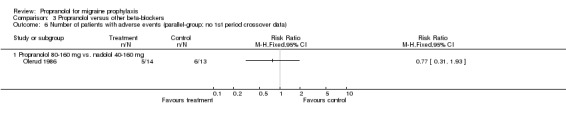

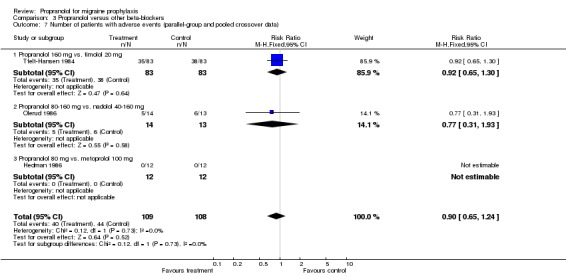

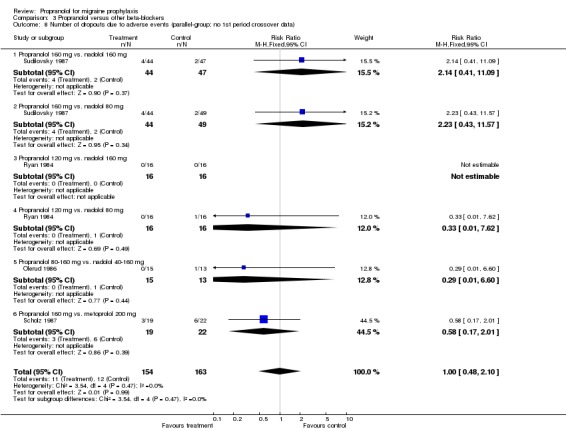

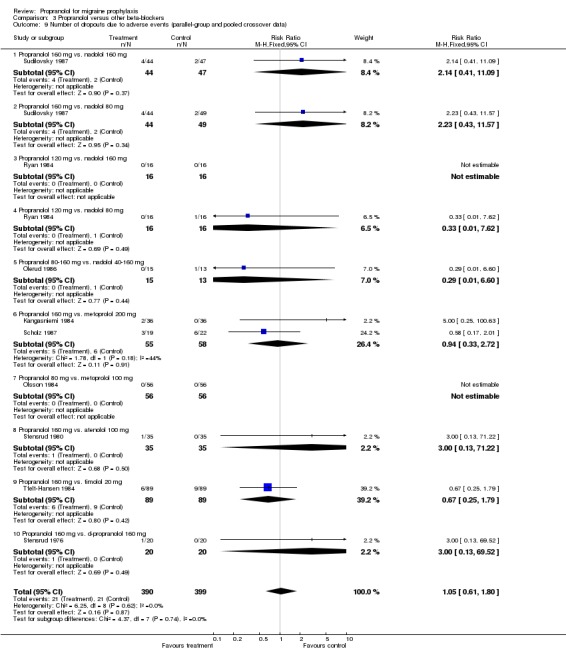

Only four trials, all crossover in design, reported attack frequency data, all pooled, and none reported significant differences; the overall standardized mean difference was ‐0.01 (95% CI ‐0.24 to 0.22; Comparison No. 03 05). There were also no clearcut differences in the number of patients with adverse events (one, respectively three, trials; Comparisons No. 03 06 and No. 03 07) or the number of patients dropping out due to adverse events (six, respectively 11, comparisons; Comparisons No. 03 08 and No. 03 09).

The vote count results were as follows: seven comparisons showing no difference, three with a trend in favour of the other beta‐blocker, one significantly in favour of the other beta‐blocker (vs. nadolol), and one not interpretable. Compared to d‐propranolol there was a trend in favour of propranolol.

Comparisons with other drugs

This category included 20 trials with 20 comparisons, plus two trials comparing propranolol alone with a combination of propranolol and amitriptyline. We did not perform quantitative meta‐analyses for the comparisons of propranolol and other drugs due to the great variety of comparator drugs used. Therefore, we provide only a descriptive summary of results here. Readers are referred to the 'Characteristics of included studies' table and the graphs in MetaView for further information.

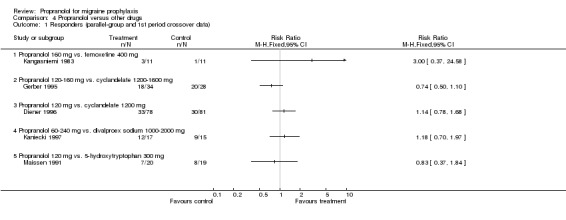

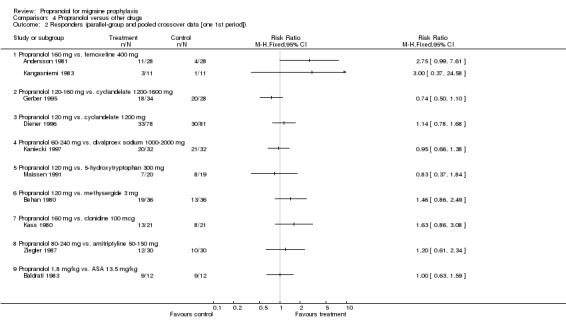

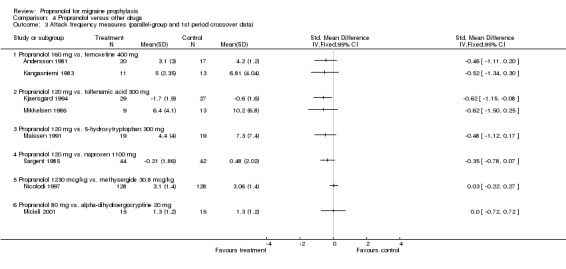

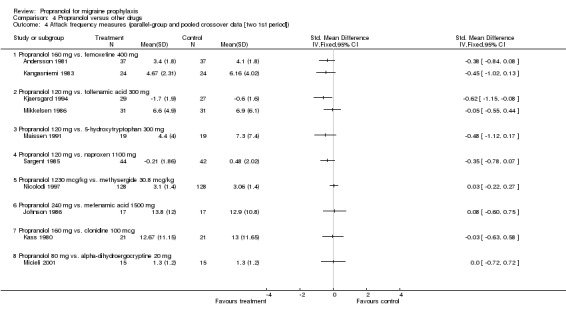

Five trials, or 10 if pooled crossover trials are included, provided responder data that could be used for effect size calculation (Comparisons No. 04 01 and No. 04 02). None found a significant difference. Both trials comparing propranolol 160 mg and femoxetine 400 mg reported a possibly relevant trend in favour of propranolol (Andersson 1981; Kangasniemi 1983). Attack frequency data were reported in eight, respectively 10, trials (Comparisons No. 04 03 and No. 04 04). Our calculations yielded a significant superiority of propranolol 120 mg in one of two trials comparing it with tolfenamic acid 300 mg (Kjaersgard 1994) and to 5‐hydroxytryptophan 300 mg (Maissen 1991). Both comparisons with femoxetine again showed a trend in favour of propranolol. No differences were observed in other trials.

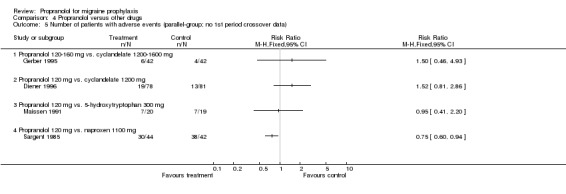

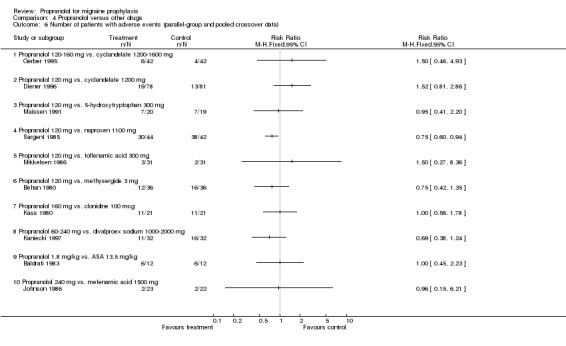

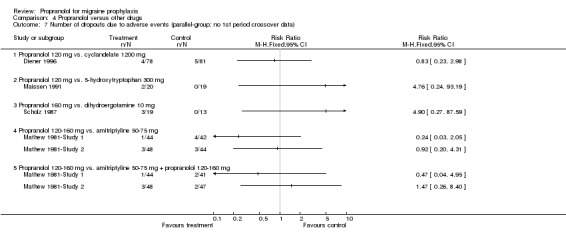

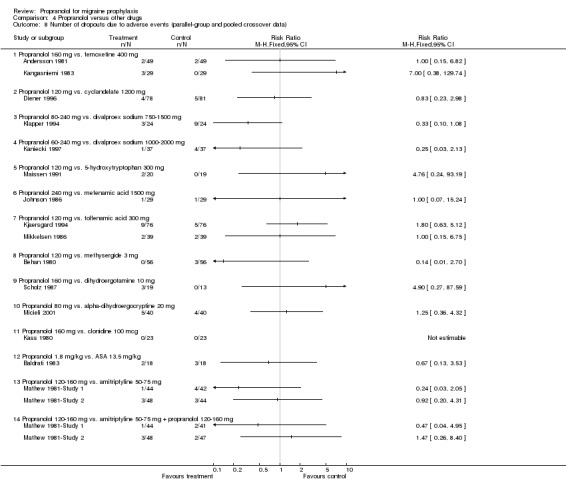

Four, respectively 10, trials described the number of patients reporting adverse events (Comparisons No. 04 05 and No. 04 06). The trial comparing propranolol 120 mg and naproxen 1100 mg reported significantly fewer adverse events with propranolol (Sargent 1985). Apart from the comparisons with cyclandelate (trend in favour of cyclandelate [Diener 1996]) and divalproex sodium (trend in favour of propranolol [Kaniecki 1997]), the numbers of patients reporting adverse events with propranolol and comparator drugs were very similar. The number of patients dropping out due to adverse events was reported for seven, respectively 18, comparisons (including the two comparisons of propranolol alone with a combination of propranolol and amitriptyline). There were no significant differences, but confidence intervals were wide due to the low number of events (Comparisons No. 04 07 and No. 04 08).

The vote count yielded the following result: one trial significantly in favour of propranolol (vs. amitriptyline), five with a trend in favour of propranolol, 11 showing no difference, two with a trend in favour of the comparator drug, and one not interpretable; one of the two comparisons of propranolol alone and propranolol in combination with amitriptyline was classified as no difference, and the other as showing a trend in favour of the combination.

Discussion

Despite the methodological limitations of the majority of the available trials, there is clear and consistent evidence that propranolol is superior to placebo in the interval treatment of patients suffering from migraine. Based on the available trials, it is not possible to draw reliable conclusions on whether different doses of propranolol have different effectiveness, or whether the prophylactic effects continue after propranolol is stopped. Propranolol seems to be as effective as other pharmacological agents used for migraine prophylaxis, and seems to have similar safety and tolerability, but definitive conclusions are not possible due to small sample sizes and the inconsistent reporting of results, which precluded a reliable meta‐analysis of the available studies.

The major problem encountered in this review was the highly variable and often insufficient reporting of the complex outcome data. Migraine prophylaxis trials typically use headache diaries to monitor the course of the disease. From these headache diaries a variety of outcomes can be extracted (headache days, migraine days, migraine attacks, days with a defined headache intensity, attack intensity, mean headache intensity, headache indices, headache hours, days with medication, use of analgesics, etc.). These outcomes can be assessed over different time frames (most often 4 weeks, but there were trials using 3 weeks, 8 weeks, total treatment periods, etc.) and presented in different manners (values at a certain time interval presented as means with standard deviations, standard errors, confidence intervals, or often no measure of variance; medians with range, quartiles, or nothing; as mean or median per cent change compared to baseline, etc.). The data reported in the included studies represent a highly heterogeneous mixture of these different options. This not only makes quantitative meta‐analysis technically difficult, but raises the question of why certain results have been presented and others not. Due to these problems, all overall effect size estimates from the quantitative meta‐analyses reported here must be interpreted with great caution.

Another problem was the high dropout rates reported. The majority of the trials were performed at a time when intention‐to‐treat analyses were not mandatory. Therefore, dropouts and withdrawals were typically excluded from analysis, which probably led to overly optimistic response rates (regardless of study group) and possibly to an over‐estimation of effects over placebo.

Due to the small sample size of most trials, the comparisons of propranolol with other drugs must be interpreted with great caution. Clinically relevant differences might exist but have not been detected. On the other hand, as there are very few trials or often only a single trial comparing a defined dose of propranolol with a comparator drug in a defined dose, any significant differences found in our effect size calculations also have to be interpreted with great care.

Taking all these problems into account, there is considerable uncertainty about the actual size of the effect of propranolol over placebo and effect sizes for propranolol in comparison with other pharmacological agents.

The main shortcoming of the available trials from a practical perspective is the lack of adequate follow up after stopping treatment. The few studies that had such a follow up reported very high withdrawal rates.

Our findings are very similar to those of a systematic review on drug treatments for the prevention of migraine headache performed for the US Agency of Health Care Policy and Research (now the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality) in 1999 (Gray 1999).

Authors' conclusions

Based on the available evidence, the use of propranolol for the prophylactic treatment of migraine is justified.

Since propranolol has been on the market for a long time, it seems unlikely that major studies will be performed in the future with propranolol as the primary experimental treatment. However, it will probably still be used as a comparator drug when new agents or uncommon dosing schemes are tested (as, e.g., in Diener 2002). We recommend that new trials follow the International Headache Society's guidelines for controlled trials of drugs for migraine (Tfelt‐Hansen 2000), so that future studies will be conducted according to a high methodological standard and will more readily permit quantitative meta‐analysis. However, as these guidelines recommend quite narrow inclusion criteria, it seems unclear whether the findings of such trials will be directly applicable to migraine treatment in primary care. Major topics for future research include the question of how stable the preventive effects of prophylactic drug treatment is once the treatment has been stopped and the extent to which migraine patients comply with prophylactic treatment in routine practice.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr HJ Jaster for extracting data from several studies, and Rebecca Gray and Douglas McCrory for their great help and input at various stages of the review.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1.

Propranolol versus placebo

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Responders (parallel‐group and 1st period crossover data) | 4 | 205 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.72 [1.23, 2.40] |

| 1.1 Propranolol 160 mg | 1 | 26 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.62 [1.34, 5.14] |

| 1.2 Propranolol 120 mg | 1 | 133 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.37 [0.85, 2.20] |

| 1.3 Propranolol 80‐120 mg | 1 | 27 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.23 [0.63, 2.42] |

| 1.4 Propranolol 80 mg | 1 | 19 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 14.67 [0.93, 232.44] |

| 2 Responders (parallel‐group and pooled crossover data) | 9 | 668 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.94 [1.61, 2.35] |

| 2.1 Propranolol 160 mg | 3 | 228 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.14 [1.59, 2.87] |

| 2.2 Propranolol 80‐160 mg | 1 | 124 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.0 [1.26, 3.18] |

| 2.3 Propranolol 120 mg | 2 | 193 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.43 [0.97, 2.10] |

| 2.4 Propranolol 80‐120 mg | 1 | 27 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.23 [0.63, 2.42] |

| 2.5 Propranolol 80 mg | 1 | 38 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.5 [1.98, 28.40] |

| 2.6 Propranolol, dose unclear | 1 | 58 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.0 [1.02, 3.93] |

| 3 Attack frequency measures (parallel‐group and 1st period crossover data) | 4 | 172 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.45 [‐0.75, ‐0.14] |

| 3.1 Propranolol 160 mg | 2 | 67 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.77 [‐1.27, ‐0.27] |

| 3.2 Propranolol 120 mg | 2 | 105 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.26 [‐0.64, 0.13] |

| 4 Attack frequency measures (parallel‐group and pooled crossover data) | 10 | 634 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.40 [‐0.56, ‐0.24] |

| 4.1 Propranolol 240 mg | 1 | 34 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.40 [‐1.08, 0.28] |

| 4.2 Propranolol 160 mg | 4 | 291 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.49 [‐0.72, ‐0.25] |

| 4.3 Propranolol 120 mg | 5 | 309 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.32 [‐0.55, ‐0.10] |

| 5 Number of patients with adverse events (parallel‐group; no 1st period crossover data) | 2 | 220 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.33 [0.97, 1.82] |

| 5.1 Propranolol 120 mg | 2 | 220 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.33 [0.97, 1.82] |

| 6 Number of patients with adverse events (parallel‐group and pooled crossover data) | 6 | 619 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.43 [1.12, 1.81] |

| 6.1 Propranolol 240 mg | 1 | 47 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.09 [0.20, 21.48] |

| 6.2 Propranolol 160 mg | 1 | 166 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.52 [0.99, 2.34] |

| 6.3 Propranolol 80‐160 mg | 1 | 124 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.6 [0.79, 3.25] |

| 6.4 Propranolol 120 mg | 3 | 282 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.30 [0.95, 1.77] |

| 7 Number of dropouts due to adverse events (parallel‐group and 1st period crossover data) | 3 | 264 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.90 [0.36, 10.14] |

| 7.1 Propranolol 80‐320 mg | 1 | 57 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7.2 Propranolol 160 mg | 1 | 74 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.28 [0.01, 6.77] |

| 7.3 Propranolol 120 mg | 1 | 133 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 6.38 [0.35, 116.13] |

| 8 Number of dropouts due to adverse events (parallel‐group and pooled crossover data) | 13 | 1150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.11 [1.09, 4.08] |

| 8.1 Propranolol 80‐320 mg | 1 | 114 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8.2 Propranolol 240 mg | 2 | 138 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.21, 4.78] |

| 8.3 Propranolol 160 mg | 5 | 381 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.15 [0.77, 6.01] |

| 8.4 Propranolol 80‐160 mg | 1 | 166 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 6.0 [0.74, 48.75] |

| 8.5 Propranolol 120 mg | 3 | 301 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.88 [0.51, 6.91] |

| 8.6 Propranolol 80 mg | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Analysis 1.1.

Comparison 1 Propranolol versus placebo, Outcome 1 Responders (parallel‐group and 1st period crossover data).

Analysis 1.2.

Comparison 1 Propranolol versus placebo, Outcome 2 Responders (parallel‐group and pooled crossover data).

Analysis 1.3.

Comparison 1 Propranolol versus placebo, Outcome 3 Attack frequency measures (parallel‐group and 1st period crossover data).

Analysis 1.4.

Comparison 1 Propranolol versus placebo, Outcome 4 Attack frequency measures (parallel‐group and pooled crossover data).

Analysis 1.5.

Comparison 1 Propranolol versus placebo, Outcome 5 Number of patients with adverse events (parallel‐group; no 1st period crossover data).

Analysis 1.6.

Comparison 1 Propranolol versus placebo, Outcome 6 Number of patients with adverse events (parallel‐group and pooled crossover data).

Analysis 1.7.

Comparison 1 Propranolol versus placebo, Outcome 7 Number of dropouts due to adverse events (parallel‐group and 1st period crossover data).

Analysis 1.8.

Comparison 1 Propranolol versus placebo, Outcome 8 Number of dropouts due to adverse events (parallel‐group and pooled crossover data).

Comparison 2.

Propranolol versus calcium antagonists

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Responders (all trials parallel‐group) | 10 | 1794 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.93, 1.09] |

| 1.1 Propranolol 180 mg vs. flunarizine 10 mg | 1 | 57 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.30 [1.01, 1.68] |

| 1.2 Propranolol 160 mg vs. flunarizine 10 mg | 2 | 598 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.76, 1.03] |

| 1.3 Propranolol 160 mg vs. flunarizine 5 mg | 1 | 517 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.89, 1.28] |

| 1.4 Propranolol 120 mg vs. flunarizine 10 mg | 3 | 464 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.87, 1.15] |

| 1.5 Propranolol 80 mg vs. flunarizine 10 mg | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.73, 1.38] |

| 1.6 Propranolol 60 mg vs. flunarizine 10 mg | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.89, 1.28] |

| 1.7 Propranolol 120‐180 mg vs. nifedipine 60‐90 mg | 1 | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.77, 1.51] |

| 1.8 Propranolol 80‐160 mg vs. nifedipine 20‐40 mg | 1 | 36 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.37 [0.72, 40.20] |

| 1.9 Propranolol 60 mg vs. propranolol 60 mg + flunarizine 10 mg | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.89, 1.28] |

| 2 Attack frequency measures (all trials parallel‐group) | 6 | 1543 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.02 [‐0.12, 0.08] |

| 2.1 Propranolol 160 mg vs. flunarizine 10 mg | 1 | 524 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.06 [‐0.11, 0.23] |

| 2.2 Propranolol 160 mg vs. flunarizine 5 mg | 1 | 518 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.07 [‐0.24, 0.10] |

| 2.3 Propranolol 120 mg vs. flunarizine 10 mg | 3 | 462 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.05 [‐0.24, 0.13] |

| 2.4 Propranolol 120‐180 mg vs. nifedipine 60‐90 mg | 1 | 20 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.19 [‐0.73, 1.11] |

| 2.5 Propranolol 120 mg vs. nimodipine 120 mg | 1 | 19 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.18 [‐1.09, 0.74] |

| 3 Number of patients with adverse events (all trials parallel‐group) | 8 | 1753 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.91, 1.15] |

| 3.1 Propranolol 160 mg vs. flunarizine 10 mg | 2 | 634 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.86, 1.24] |

| 3.2 Propranolol 160 mg vs. flunarizine 5 mg | 1 | 533 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.76, 1.24] |

| 3.3 Propranolol 120 mg vs. flunarizine 10 mg | 3 | 464 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.97, 1.52] |

| 3.4 Propranolol 60 mg vs. flunarizine 10 mg | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.13, 3.44] |

| 3.5 Propranolol 120‐180 mg vs. nifedipine 60‐90 mg | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.76 [0.58, 0.98] |

| 3.6 Propranolol 120 mg vs. nimodipine 120 mg | 1 | 22 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.38, 1.12] |

| 3.7 Propranolol 60 mg vs. propanolol 60 mg + flunarizine 10 mg | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.5 [0.11, 2.33] |

| 4 Number of patients with adverse events (vs. flunarizine; all trials parallel‐group) | 6 | 1661 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.94, 1.20] |

| 4.1 Propranolol 160 mg vs. flunarizine 10 mg | 2 | 634 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.86, 1.24] |

| 4.2 Propranolol 160 mg vs. flunarizine 5 mg | 1 | 533 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.76, 1.24] |

| 4.3 Propranolol 120 mg vs. flunarizine 10 mg | 3 | 464 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.97, 1.52] |

| 4.4 Propranolol 60 mg vs. flunarizine 10 mg | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.13, 3.44] |

| 5 Number of dropouts due to adverse events (all trials parallel‐group) | 9 | 1533 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.59, 1.13] |

| 5.1 Propranolol 180 mg vs. flunarizine 10 mg | 1 | 58 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.5 [0.27, 8.32] |

| 5.2 Propranolol 160 mg vs. flunarizine 10 mg | 3 | 665 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.61, 1.78] |

| 5.3 Propranolol 160 mg vs. flunarizine 5 mg | 1 | 533 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.46, 1.53] |

| 5.4 Propranolol 120 mg vs. flunarizine 10 mg | 1 | 59 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.27 [0.23, 7.03] |

| 5.5 Propranolol 80 mg vs. flunarizine 10 mg | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5.6 Propranolol 60 mg vs. flunarizine 10 mg | 1 | 35 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5.7 Propranolol 120 mg vs. nimodipine 120 mg | 1 | 22 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.4 [0.25, 22.75] |

| 5.8 Propranolol 160 mg vs. nifedipine 40 mg | 1 | 36 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.11, 1.06] |

| 5.9 Propranolol 120‐180 mg vs. nifedipine 60‐90 mg | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.17, 0.88] |

| 5.10 Propranolol 60 mg vs. propranolol 60 mg + flunarizine 10 mg | 1 | 35 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6 Number of dropouts due to adverse events (vs. flunarizine; all trials parallel‐group) | 7 | 1400 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.67, 1.44] |

| 6.1 Propranolol 180 mg vs. flunarizine 10 mg | 1 | 58 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.5 [0.27, 8.32] |

| 6.2 Propranolol 160 mg vs. flunarizine 10 mg | 3 | 665 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.61, 1.78] |

| 6.3 Propranolol 160 mg vs. flunarizine 5 mg | 1 | 533 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.46, 1.53] |

| 6.4 Propranolol 120 mg vs. flunarizine 10 mg | 1 | 59 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.27 [0.23, 7.03] |

| 6.5 Propranolol 80 mg vs. flunarizine 10 mg | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6.6 Propranolol 60 mg vs. flunarizine 10 mg | 1 | 35 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7 Number of dropouts due to adverse events (vs. nifedipine; all trials parallel‐group) | 2 | 76 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.37 [0.19, 0.72] |

| 7.1 Propranolol 160 mg vs. nifedipine 40 mg | 1 | 36 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.11, 1.06] |

| 7.2 Propranolol 120‐180 mg vs. nifedipine 60‐90 mg | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.17, 0.88] |

Analysis 2.1.

Comparison 2 Propranolol versus calcium antagonists, Outcome 1 Responders (all trials parallel‐group).

Analysis 2.2.

Comparison 2 Propranolol versus calcium antagonists, Outcome 2 Attack frequency measures (all trials parallel‐group).

Analysis 2.3.

Comparison 2 Propranolol versus calcium antagonists, Outcome 3 Number of patients with adverse events (all trials parallel‐group).

Analysis 2.4.

Comparison 2 Propranolol versus calcium antagonists, Outcome 4 Number of patients with adverse events (vs. flunarizine; all trials parallel‐group).

Analysis 2.5.

Comparison 2 Propranolol versus calcium antagonists, Outcome 5 Number of dropouts due to adverse events (all trials parallel‐group).

Analysis 2.6.

Comparison 2 Propranolol versus calcium antagonists, Outcome 6 Number of dropouts due to adverse events (vs. flunarizine; all trials parallel‐group).

Analysis 2.7.

Comparison 2 Propranolol versus calcium antagonists, Outcome 7 Number of dropouts due to adverse events (vs. nifedipine; all trials parallel‐group).

Comparison 3.

Propranolol versus other beta‐blockers

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Responders (parallel‐group; no 1st period crossover data) | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Propranolol 160 mg vs. nadolol 160 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Propranolol 160 mg vs. nadolol 80 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.3 Propranolol 80‐160 mg vs. nadolol 40‐160 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.4 Propranolol 80‐160 mg vs. metoprolol 100‐200 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 Responders (parallel‐group and pooled crossover data) | 6 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 Propranolol 160 mg vs. nadolol 160 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.2 Propranolol 160 mg vs. nadolol 80 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.3 Propranolol 80‐160 mg vs. nadolol 40‐160 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.4 Propranolol 160 mg vs. metoprolol 200 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.5 Propranolol 80‐160 mg vs. metoprolol 100‐200 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.6 Propranolol 80 mg vs. metoprolol 100 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.7 Propranolol 160 mg vs. timolol 20 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3 Responders (vs. nadolol; parallel‐group and pooled crossover data) | 2 | 147 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.60 [0.37, 0.97] |

| 3.1 Propranolol 160 mg vs. nadolol 160 mg | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.15, 0.79] |

| 3.2 Propranolol 160 mg vs. nadolol 80 mg | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.56 [0.22, 1.40] |

| 3.3 Propranolol 80‐160 mg vs. nadolol 40‐160 mg | 1 | 27 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.49 [0.65, 3.39] |

| 4 Responders (vs. metoprolol; parallel‐group and pooled crossover data) | 3 | 216 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.56, 1.09] |

| 4.1 Propranolol 160 mg vs. metoprolol 200 mg | 1 | 66 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.54, 1.45] |

| 4.2 Propranolol 80‐160 mg vs. metoprolol 100‐200 mg | 1 | 41 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.58 [0.27, 1.24] |

| 4.3 Propranolol 80 mg vs. metoprolol 100 mg | 1 | 109 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.47, 1.37] |

| 5 Attack frequency measures (pooled crossover only; no parallel‐group or 1st period crossover data) | 4 | 290 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.01 [‐0.24, 0.22] |

| 5.1 Propranolol 160 mg vs. metoprolol 200 mg | 1 | 68 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [‐0.48, 0.48] |

| 5.2 Propranolol 80 mg vs. metoprolol 100 mg | 1 | 24 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.43 [‐1.24, 0.38] |

| 5.3 Propranolol 160 mg vs. timolol 20 mg | 1 | 160 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.10 [‐0.21, 0.41] |

| 5.4 Propranolol 160 mg vs. d‐propranolol 160 mg | 1 | 38 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.27 [‐0.91, 0.37] |

| 6 Number of patients with adverse events (parallel‐group; no 1st period crossover data) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6.1 Propranolol 80‐160 mg vs. nadolol 40‐160 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7 Number of patients with adverse events (parallel‐group and pooled crossover data) | 3 | 217 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.65, 1.24] |

| 7.1 Propranolol 160 mg vs. timolol 20 mg | 1 | 166 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.65, 1.30] |

| 7.2 Propranolol 80‐160 mg vs. nadolol 40‐160 mg | 1 | 27 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.31, 1.93] |

| 7.3 Propranolol 80 mg vs. metoprolol 100 mg | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8 Number of dropouts due to adverse events (parallel‐group; no 1st period crossover data) | 4 | 317 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.48, 2.10] |

| 8.1 Propranolol 160 mg vs. nadolol 160 mg | 1 | 91 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.14 [0.41, 11.09] |

| 8.2 Propranolol 160 mg vs. nadolol 80 mg | 1 | 93 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.23 [0.43, 11.57] |

| 8.3 Propranolol 120 mg vs. nadolol 160 mg | 1 | 32 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8.4 Propranolol 120 mg vs. nadolol 80 mg | 1 | 32 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 7.62] |

| 8.5 Propranolol 80‐160 mg vs. nadolol 40‐160 mg | 1 | 28 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.29 [0.01, 6.60] |

| 8.6 Propranolol 160 mg vs. metoprolol 200 mg | 1 | 41 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.58 [0.17, 2.01] |

| 9 Number of dropouts due to adverse events (parallel‐group and pooled crossover data) | 9 | 789 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.61, 1.80] |

| 9.1 Propranolol 160 mg vs. nadolol 160 mg | 1 | 91 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.14 [0.41, 11.09] |

| 9.2 Propranolol 160 mg vs. nadolol 80 mg | 1 | 93 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.23 [0.43, 11.57] |

| 9.3 Propranolol 120 mg vs. nadolol 160 mg | 1 | 32 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9.4 Propranolol 120 mg vs. nadolol 80 mg | 1 | 32 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 7.62] |

| 9.5 Propranolol 80‐160 mg vs. nadolol 40‐160 mg | 1 | 28 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.29 [0.01, 6.60] |

| 9.6 Propranolol 160 mg vs. metoprolol 200 mg | 2 | 113 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.33, 2.72] |

| 9.7 Propranolol 80 mg vs. metoprolol 100 mg | 1 | 112 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9.8 Propranolol 160 mg vs. atenolol 100 mg | 1 | 70 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 71.22] |

| 9.9 Propranolol 160 mg vs. timolol 20 mg | 1 | 178 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.25, 1.79] |

| 9.10 Propranolol 160 mg vs. d‐propranolol 160 mg | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 69.52] |

Analysis 3.1.

Comparison 3 Propranolol versus other beta‐blockers, Outcome 1 Responders (parallel‐group; no 1st period crossover data).

Analysis 3.2.

Comparison 3 Propranolol versus other beta‐blockers, Outcome 2 Responders (parallel‐group and pooled crossover data).

Analysis 3.3.

Comparison 3 Propranolol versus other beta‐blockers, Outcome 3 Responders (vs. nadolol; parallel‐group and pooled crossover data).

Analysis 3.4.

Comparison 3 Propranolol versus other beta‐blockers, Outcome 4 Responders (vs. metoprolol; parallel‐group and pooled crossover data).

Analysis 3.5.

Comparison 3 Propranolol versus other beta‐blockers, Outcome 5 Attack frequency measures (pooled crossover only; no parallel‐group or 1st period crossover data).

Analysis 3.6.

Comparison 3 Propranolol versus other beta‐blockers, Outcome 6 Number of patients with adverse events (parallel‐group; no 1st period crossover data).

Analysis 3.7.

Comparison 3 Propranolol versus other beta‐blockers, Outcome 7 Number of patients with adverse events (parallel‐group and pooled crossover data).

Analysis 3.8.

Comparison 3 Propranolol versus other beta‐blockers, Outcome 8 Number of dropouts due to adverse events (parallel‐group; no 1st period crossover data).

Analysis 3.9.

Comparison 3 Propranolol versus other beta‐blockers, Outcome 9 Number of dropouts due to adverse events (parallel‐group and pooled crossover data).

Comparison 4.

Propranolol versus other drugs

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Responders (parallel‐group and 1st period crossover data) | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Propranolol 160 mg vs. femoxetine 400 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Propranolol 120‐160 mg vs. cyclandelate 1200‐1600 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.3 Propranolol 120 mg vs. cyclandelate 1200 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.4 Propranolol 60‐240 mg vs. divalproex sodium 1000‐2000 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.5 Propranolol 120 mg vs. 5‐hydroxytryptophan 300 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 Responders (parallel‐group and pooled crossover data [one 1st period]) | 10 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 Propranolol 160 mg vs. femoxetine 400 mg | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.2 Propranolol 120‐160 mg vs. cyclandelate 1200‐1600 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.3 Propranolol 120 mg vs. cyclandelate 1200 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.4 Propranolol 60‐240 mg vs. divalproex sodium 1000‐2000 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.5 Propranolol 120 mg vs. 5‐hydroxytryptophan 300 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.6 Propranolol 120 mg vs. methysergide 3 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.7 Propranolol 160 mg vs. clonidine 100 mcg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.8 Propranolol 80‐240 mg vs. amitriptyline 50‐150 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.9 Propranolol 1.8 mg/kg vs. ASA 13.5 mg/kg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3 Attack frequency measures (parallel‐group and 1st period crossover data) | 8 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 Propranolol 160 mg vs. femoxetine 400 mg | 2 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.2 Propranolol 120 mg vs. tolfenamic acid 300 mg | 2 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.3 Propranolol 120 mg vs. 5‐hydroxytryptophan 300 mg | 1 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.4 Propranolol 120 mg vs. naproxen 1100 mg | 1 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.5 Propranolol 1230 mcg/kg vs. methysergide 30.8 mcg/kg | 1 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.6 Propranolol 80 mg vs. alpha‐dihydroergocryptine 20 mg | 1 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4 Attack frequency measures (parallel‐group and pooled crossover data [two 1st period]) | 10 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4.1 Propranolol 160 mg vs. femoxetine 400 mg | 2 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.2 Propranolol 120 mg vs. tolfenamic acid 300 mg | 2 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.3 Propranolol 120 mg vs. 5‐hydroxytryptophan 300 mg | 1 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.4 Propranolol 120 mg vs. naproxen 1100 mg | 1 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.5 Propranolol 1230 mcg/kg vs. methysergide 30.8 mcg/kg | 1 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.6 Propranolol 240 mg vs. mefenamic acid 1500 mg | 1 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.7 Propranolol 160 mg vs. clonidine 100 mcg | 1 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.8 Propranolol 80 mg vs. alpha‐dihydroergocryptine 20 mg | 1 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5 Number of patients with adverse events (parallel‐group; no 1st period crossover data) | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5.1 Propranolol 120‐160 mg vs. cyclandelate 1200‐1600 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.2 Propranolol 120 mg vs. cyclandelate 1200 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.3 Propranolol 120 mg vs. 5‐hydroxytryptophan 300 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.4 Propranolol 120 mg vs. naproxen 1100 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6 Number of patients with adverse events (parallel‐group and pooled crossover data) | 10 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6.1 Propranolol 120‐160 mg vs. cyclandelate 1200‐1600 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.2 Propranolol 120 mg vs. cyclandelate 1200 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.3 Propranolol 120 mg vs. 5‐hydroxytryptophan 300 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.4 Propranolol 120 mg vs. naproxen 1100 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.5 Propranolol 120 mg vs. tolfenamic acid 300 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.6 Propranolol 120 mg vs. methysergide 3 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.7 Propranolol 160 mg vs. clonidine 100 mcg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.8 Propranolol 60‐240 mg vs. divalproex sodium 1000‐2000 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.9 Propranolol 1.8 mg/kg vs. ASA 13.5 mg/kg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.10 Propranolol 240 mg vs. mefenamic acid 1500 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7 Number of dropouts due to adverse events (parallel‐group; no 1st period crossover data) | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 7.1 Propranolol 120 mg vs. cyclandelate 1200 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7.2 Propranolol 120 mg vs. 5‐hydroxytryptophan 300 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7.3 Propranolol 160 mg vs. dihydroergotamine 10 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7.4 Propranolol 120‐160 mg vs. amitriptyline 50‐75 mg | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7.5 Propranolol 120‐160 mg vs. amitriptyline 50‐75 mg + propranolol 120‐160 mg | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 8 Number of dropouts due to adverse events (parallel‐group and pooled crossover data) | 16 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 8.1 Propranolol 160 mg vs. femoxetine 400 mg | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 8.2 Propranolol 120 mg vs. cyclandelate 1200 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 8.3 Propranolol 80‐240 mg vs. divalproex sodium 750‐1500 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 8.4 Propranolol 60‐240 mg vs. divalproex sodium 1000‐2000 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 8.5 Propranolol 120 mg vs. 5‐hydroxytryptophan 300 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 8.6 Propranolol 240 mg vs. mefenamic acid 1500 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 8.7 Propranolol 120 mg vs. tolfenamic acid 300 mg | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 8.8 Propranolol 120 mg vs. methysergide 3 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 8.9 Propranolol 160 mg vs. dihydroergotamine 10 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 8.10 Propranolol 80 mg vs. alpha‐dihydroergocryptine 20 mg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 8.11 Propranolol 160 mg vs. clonidine 100 mcg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 8.12 Propranolol 1.8 mg/kg vs. ASA 13.5 mg/kg | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 8.13 Propranolol 120‐160 mg vs. amitriptyline 50‐75 mg | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 8.14 Propranolol 120‐160 mg vs. amitriptyline 50‐75 mg + propranolol 120‐160 mg | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Analysis 4.1.

Comparison 4 Propranolol versus other drugs, Outcome 1 Responders (parallel‐group and 1st period crossover data).

Analysis 4.2.

Comparison 4 Propranolol versus other drugs, Outcome 2 Responders (parallel‐group and pooled crossover data [one 1st period]).

Analysis 4.3.

Comparison 4 Propranolol versus other drugs, Outcome 3 Attack frequency measures (parallel‐group and 1st period crossover data).

Analysis 4.4.

Comparison 4 Propranolol versus other drugs, Outcome 4 Attack frequency measures (parallel‐group and pooled crossover data [two 1st period]).

Analysis 4.5.

Comparison 4 Propranolol versus other drugs, Outcome 5 Number of patients with adverse events (parallel‐group; no 1st period crossover data).

Analysis 4.6.

Comparison 4 Propranolol versus other drugs, Outcome 6 Number of patients with adverse events (parallel‐group and pooled crossover data).

Analysis 4.7.

Comparison 4 Propranolol versus other drugs, Outcome 7 Number of dropouts due to adverse events (parallel‐group; no 1st period crossover data).

Analysis 4.8.

Comparison 4 Propranolol versus other drugs, Outcome 8 Number of dropouts due to adverse events (parallel‐group and pooled crossover data).

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 10 June 2019 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

History