Abstract

Background

Group therapy offers individuals the opportunity to learn behavioural techniques for smoking cessation, and to provide each other with mutual support.

Objectives

To determine the effect of group‐delivered behavioural interventions in achieving long‐term smoking cessation.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialized Register, using the terms 'behavior therapy', 'cognitive therapy', 'psychotherapy' or 'group therapy', in May 2016.

Selection criteria

Randomized trials that compared group therapy with self‐help, individual counselling, another intervention or no intervention (including usual care or a waiting‐list control). We also considered trials that compared more than one group programme. We included those trials with a minimum of two group meetings, and follow‐up of smoking status at least six months after the start of the programme. We excluded trials in which group therapy was provided to both active therapy and placebo arms of trials of pharmacotherapies, unless they had a factorial design.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors extracted data in duplicate on the participants, the interventions provided to the groups and the controls, including programme length, intensity and main components, the outcome measures, method of randomization, and completeness of follow‐up. The main outcome measure was abstinence from smoking after at least six months follow‐up in participants smoking at baseline. We used the most rigorous definition of abstinence in each trial, and biochemically‐validated rates where available. We analysed participants lost to follow‐up as continuing smokers. We expressed effects as a risk ratio for cessation. Where possible, we performed meta‐analysis using a fixed‐effect (Mantel‐Haenszel) model. We assessed the quality of evidence within each study and comparison, using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool and GRADE criteria.

Main results

Sixty‐six trials met our inclusion criteria for one or more of the comparisons in the review. Thirteen trials compared a group programme with a self‐help programme; there was an increase in cessation with the use of a group programme (N = 4395, risk ratio (RR) 1.88, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.52 to 2.33, I2 = 0%). We judged the GRADE quality of evidence to be moderate, downgraded due to there being few studies at low risk of bias. Fourteen trials compared a group programme with brief support from a health care provider. There was a small increase in cessation (N = 7286, RR 1.22, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.43, I2 = 59%). We judged the GRADE quality of evidence to be low, downgraded due to inconsistency in addition to risk of bias. There was also low quality evidence of benefit of a group programme compared to no‐intervention controls, (9 trials, N = 1098, RR 2.60, 95% CI 1.80 to 3.76 I2 = 55%). We did not detect evidence that group therapy was more effective than a similar intensity of individual counselling (6 trials, N = 980, RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.28, I2 = 9%). Programmes which included components for increasing cognitive and behavioural skills were not shown to be more effective than same‐length or shorter programmes without these components.

Authors' conclusions

Group therapy is better for helping people stop smoking than self‐help, and other less intensive interventions. There is not enough evidence to evaluate whether groups are more effective, or cost‐effective, than intensive individual counselling. There is not enough evidence to support the use of particular psychological components in a programme beyond the support and skills training normally included.

Plain language summary

Do group‐based smoking cessation programmes help people to stop smoking?

Background

One approach to help people who are trying to quit smoking is to offer them group‐based support. Participants meet regularly, with a facilitator who is typically trained in smoking cessation counselling. Programme components are varied. A perceived strength of this approach is that participants provide each other with support and encouragement. The outcome of interest was not smoking at least six months from the start of the group programme.

Study characteristics

We identified 66 trials comparing group‐based programmes to other types of support, or comparing different types of group programme. The most recent search was in May 2016.

Results & quality of evidence

In 13 trials (4395 participants) people in the control conditions were provided with a self‐help programme. There was a benefit for the group‐based approach, with the chance of quitting increased by 50% to 130%. This means that if five in 100 people were able to quit for at least six months using self‐help materials, eight to 12 in 100 might be successful if offered group support. We judged the quality of this evidence as moderate, because studies did not report methods in enough detail to exclude possible bias. There was also evidence of a benefit of group support compared to advice and brief support from a healthcare professional (14 trials, 7286 participants), although the difference was smaller and more variable. We rated this as low‐quality evidence, because of the variability as well as possible risk of bias. There was also low‐quality evidence of a benefit in studies that did not provide the control group with any help to quit (9 trials, 1098 participants). Six trials (980 participants) compared group format with individual face‐to‐face counselling; there was no sign that one approach was more helpful than the other. The remaining studies compared different types of group programmes; typically they did not show differences, so it is not possible to show which components of group‐based programmes are most helpful.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Group‐format behavioural programmes compared to alternative support for smoking cessation.

| Patient or population: People who smoke Setting: Smoking cessation clinics predominantly recruiting people interested in quitting smoking, from community and healthcare settings Intervention: Group‐format behavioural programmes Comparison: Various | ||||||

| Outcome: Smoking cessation assessed at least 6 months after start of treatment, based on self‐report, ± biochemical validation of abstinence | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Numbers quit in control conditions | Numbers quit after group programme | |||||

| Group programme compared to self‐help programme | Moderate | RR 1.88 (1.52 to 2.33) | 4395 (13 RCTs) 2 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 3 | ||

| 5 per 100 1 | 9 per 100 (8 to 12) | |||||

| Group programme compared to brief support | Moderate | RR 1.25 (1.07 to 1.46) | 7601 (16 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3 4 | ||

| 5 per 100 5 | 6 per 100 (5 to 7) | |||||

| Group programme compared to face‐to‐face individual intervention | Moderate | RR 0.99 (0.76 to 1.28) | 980 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 3 | ||

| 11 per 100 6 | 11 per 100 (8 to 14) | |||||

| Group programme plus pharmacotherapy versus pharmacotherapy and brief support alone | Moderate | RR 1.11 (0.93 to 1.33) | 1523 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 8 | ||

| 18 per 100 7 | 20 per 100 (17 to 24) | |||||

| Group programme versus 'no intervention' controls | Moderate | RR 2.60 (1.80 to 3.76) | 1098 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3 9 | ||

| 5 per 100 | 13 per 100 (9 to 19) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1Moderate assumed control condition quit rate, mid way between higher crude average and lower weighted average. 2Including 4 cluster‐randomized studies. 3Most studies at unclear risk of bias for allocation and concealment, probably reflecting poor reporting in old studies. Downgraded, but potential for large over‐ or under‐estimation of effect size low. 4Heterogeneity in pooled estimate. 5Based on crude average in control conditions. The weighted average would be 4%; one large trial had very low quit rates from brief support. 6Based on average in studies of individual counselling without pharmacotherapy from review of individual counselling. 7Based on control condition rate from review of behavioural adjuncts to pharmacotherapy. 8Downgraded due to imprecision. A larger review of the effect of increasing behavioural support as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy detected a small benefit. 9Most studies did not biochemically validate abstinence.

Background

Group therapy is a common method of delivering smoking cessation interventions. Over 100 group therapies have been described (Hajek 1996). The purposes of group programmes have been summarized as: to analyse motives for group members' behaviour; to provide an opportunity for social learning; to generate emotional experiences; and to impart information and teach new skills (Hajek 1985; Hajek 1996). Group programmes may be led by professional facilitators such as clinical psychologists, health educators, nurses or physicians, or occasionally by successful users of the programme.

The implementation of smoking cessation programmes in groups has been a popular method of delivering behavioural interventions. Behavioural interventions typically include such methods as coping and social skills training, contingency management, self‐control, and cognitive‐behavioural interventions. The use of a group format for the delivery of a behavioural intervention appears to have two underlying rationales. Lying between self‐help methods with minimal therapist contact and intensive individual counselling/therapy, a group might offer better cessation rates than the former, with lower costs per smoker than the latter. There may be a specific therapeutic benefit of the group format in giving people who smoke the opportunity to share problems and experiences with others attempting to quit. This might lead to increased quit rates, even compared to individual face‐to‐face methods.

More recent research has focused on identifying the components that contribute most to the success of the intervention. In particular, there is interest in ways to enhance programmes with components which could be specifically helpful for those with poor success rates for quitting, such as people with histories of depressive disorder or substance abuse. In addition to evaluating the benefit of generic group behaviour therapy for smoking cessation, this review evaluates the evidence for including specific strategies or psychological techniques in group programmes.

Objectives

To determine the effect of group‐delivered behavioural interventions in achieving long‐term smoking cessation.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Trials were eligible for inclusion if participants were randomly allocated to treatment conditions. We included trials of worksite smoking cessation programmes which randomized worksites to different programmes. We also included studies that randomized therapists, rather than smokers, to offer group therapy or control, provided that the specific aim of the study was to examine the effect of group therapy on smoking cessation.

Types of participants

Adult smokers of either gender, irrespective of their initial level of nicotine dependency, recruited from any setting, with the exception of trials recruiting pregnant women in antenatal care settings, since interventions for pregnant women are reviewed separately (Chamberlain 2013). Interventions recruiting only adolescent smokers are also reviewed separately (Grimshaw 2013).

Types of interventions

We considered studies in which smokers met for scheduled meetings and received some form of behavioural intervention, such as information, advice and encouragement or cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) delivered over at least two sessions. We excluded studies of interventions where participants met once for an orientation or information session. We excluded studies which covered group meetings but which were primarily investigating the efficacy of aversive smoking, acupuncture, hypnotherapy, exercise or partner support, unless there were other relevant arms. Trials investigating these specific components have been separately reviewed by Hajek 2001, White 2014, Barnes 2010, Ussher 2014 and Park 2012 respectively. We exclude trials of components to prevent relapse, as they are covered by a separate review (Hajek 2013). Trials in which smokers received group therapy in addition to active or placebo pharmacotherapy were excluded unless there were other relevant arms. The effect of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) is evaluated in a separate review (Stead 2012), but we include studies which tested group therapy as an adjunct to nicotine replacement.

Types of outcome measures

The main outcome was abstinence from cigarettes at follow‐up at least six months after the start of treatment. We excluded trials that reported only shorter follow‐up or had no measurement of smoking cessation. In each study we used the strictest available criteria to define abstinence. For example, in studies where biochemical validation of cessation was available, we counted as abstinent only those participants who met the criteria for biochemically‐confirmed abstinence. Wherever possible, we used a sustained cessation rate, rather than point prevalence. Where participants were lost to follow‐up, we regarded them as being continuing smokers.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialized Register for reports of studies with the keywords 'Behavio$r therapy', 'Group therapy' or 'Cognitive therapy' or free‐text terms 'behav*' and 'group*'. At the time of the search in May 2016 the Register included the results of searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (CENTRAL), issue 4, 2016; MEDLINE (via OVID) to update 20160513; Embase (via OVID) to week 201621; PsycINFO (via OVID) to update 20160516. See the Tobacco Addiction Group Module in the Cochrane Library for full search strategies and lists of other resources searched. The most recent search was conducted in May 2016. For earlier versions of the review we also checked the US Public Health Service Clinical Practice Guidelines on smoking cessation (Fiore 1996; Fiore 2008) reference lists for trials used in meta‐analyses assessing the efficacy of different treatment formats and the components of effective interventions.

Data collection and analysis

LS (Cochrane Information Specialist for the Tobacco Addiction Group) identified trials which met the screening criteria of having one group therapy arm and sufficient length of follow‐up. For the update in 2017, LS and AC independently checked and data‐extracted reports of potentially relevant interventions.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risks of selection bias based on methodology in the Cochrane Handbook (section 8.5) (Higgins 2011). We assessed risk of detection bias based on whether self‐reported smoking cessation was biochemically validated. Methods for validating abstinence include measuring carbon monoxide in exhaled air, and measuring cotinine, a metabolite of nicotine, in saliva or urine. We judged studies using any method of validation to be at low risk of bias. We assessed risk of attrition bias as high if loss to follow‐up was both high and differed across study arms.

Measures of treatment effect & data synthesis

We summarized individual study results as a risk ratio, calculated as: (number of quitters in intervention group/ number randomized to intervention group) / (number of quitters in control group/ number randomized to control group). We assumed that participants lost to follow‐up were continuing smokers and included them in denominators. We excluded any deaths from denominators. Where appropriate, we performed meta‐analysis using a Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect method to estimate a pooled risk ratio with a 95% confidence interval (Greenland 1985). We estimated the amount of statistical heterogeneity between trials using the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). Values over 50% can be regarded as moderate heterogeneity, and values over 75% as high.

If trial reports did not present results in a form which allowed extraction of the necessary key data, we attempted to contact investigators.

If a trial had both a comparable programme with non‐group delivery, and a waiting‐list or minimal‐intervention control, we included both in the appropriate comparisons. If two different group programmes were compared with another method or a control, we combined the group interventions in the comparison of group versus non‐group methods. We made the following comparisons, based on the characteristics of the comparator condition: 1.1 Groups versus self‐help programmes: 1.1.1 Group therapy plus self‐help manuals versus the same self‐help programme alone 1.1.2 Group therapy plus self‐help manuals versus a different self‐help programme 1.2 Group versus other less intensive interventions: 1.2.1 Group therapy versus physician, nurse, or pharmacist advice 1.2.2 Group therapy versus health education

1.3 Group therapy plus pharmacotherapy versus pharmacotherapy alone

1.4 Group therapy versus individual counselling sessions: 1.4.1 Group versus individual therapy, similar intensity, same programme content 1.4.2 Group versus individual therapy, similar intensity, different programme content 1.5 Group therapy versus no intervention (including usual care, minimal contact or a waiting‐list control) 2 Comparisons between group programmes (with and without matching for intensity and contact time) 2.1 Skills training 2.2 Mood management 2.3 Manipulation of group dynamics 2.4 Other miscellaneous comparisons

Results

Description of studies

We include 66 studies in this review. Forty studies compared a group programme with a non‐group‐based cessation intervention, or a no‐intervention control (Glasgow 1981; Pederson 1981; Cottraux 1983; Rabkin 1984; McDowell 1985; DePaul 1987; Curry 1988; Omenn 1988; DePaul 1989; Garcia 1989; Leung 1991; Ginsberg 1992; Gruder 1993; Hill 1993; Hilleman 1993; Hollis 1993; Sawicki 1993; Batra 1994; DePaul 1994; Rice 1994; Jorenby 1995; Nevid 1997; Bakkevig 2000; García 2000; Minthorn‐Biggs 2000; Camarelles 2002; Hall 2002; Grant 2003; Pisinger 2005; Romand 2005; Slovinec 2005; Otero 2006; Zheng 2007; Wilson 2008; Dent 2009; Rovina 2009; Pisinger 2010; Webb 2010; Gifford 2011; Schleicher 2012). Some of these compared group therapy with more than one alternative and were included in each relevant comparison group. Some compared more than one programme or used a factorial design, and in most cases we collapsed the factorial structure and combined different group programmes in the comparison with a non‐group control. The other 26 studies did not have a non‐group control and contribute only to comparisons between different group‐based programmes.

Most studies recruited community volunteers prepared to participate in group programmes. Three studies recruited in primary care settings (McDowell 1985; Hollis 1993; Pisinger 2010). Other studies recruited participants with a diagnosed cardiovascular health problem (Rice 1994), people with diabetes (Sawicki 1993), people with schizophrenia (George 2000), participants in an outpatient alcohol treatment programme (Grant 2003), and people in an inpatient alcohol treatment programme (Mueller 2012). Three studies conducted at DePaul University recruited employees in worksites which had been randomly assigned to provide different programme formats. One other study (Omenn 1988) also recruited at a worksite, but individual smokers were randomized to treatment.

Two studies recruited only women (Slovinec 2005; Schmitz 2007). One Chinese study recruited predominantly men (Zheng 2007). Two studies recruited only African‐American smokers (Matthews 2009; Webb 2010).

The group programmes varied in their length, format and content. The description in the table Characteristics of included studies gives the number and length of sessions and brief details of main components of the intervention. Most programmes used between six and eight sessions, with the first few sessions devoted to discussion of motivation for quitting, health benefits, and strategies for planning a quit attempt. Specific components at this stage may include signing a contract to quit, or making a public declaration, and nicotine fading (changing the type of cigarette smoked to a lower nicotine brand). Participants may also keep records of the number of cigarettes smoked and the triggers for smoking (self‐monitoring). Part of the group process also includes discussion and sharing of experiences and problems (intra‐treatment social support). Participants may also be instructed on ways to seek appropriate support from friends, colleagues and family (extra‐treatment social support). A range of other problem‐solving skills may also be introduced, including identifying high‐risk situations for relapse, generating solutions and discussing or rehearsing responses. Some programmes incorporate more specific components intended to help manage poor mood or depression associated with quitting and withdrawal.

Most studies followed participants for 12 months. Twenty‐two out of 66 (33%) had only six months follow‐up (Glasgow 1981; Pederson 1981; Rabkin 1984; Garcia 1989; Glasgow 1989; Goldstein 1989; Leung 1991; Sawicki 1993; Digiusto 1995; Jorenby 1995; Bushnell 1997; George 2000; Minthorn‐Biggs 2000; Camarelles 2002; Zheng 2007; Dent 2009; Matthews 2009; Macpherson 2010; Webb 2010; Aytemur 2012; Mueller 2012; Schleicher 2012). One study has reported five‐year follow‐up (Pisinger 2005). Of the studies with one‐year follow‐up, 23 reported an outcome requiring a sustained period of cessation; 13 with non‐group controls (DePaul 1987; Curry 1988; DePaul 1989; Gruder 1993; Hollis 1993; Batra 1994; DePaul 1994; Nevid 1997; Hall 2002; Romand 2005; Wilson 2008; Rovina 2009; Ramos 2010) and nine with only between‐group comparisons (Lando 1990; Lando 1991; Zelman 1992; Hall 1994; Hall 1996; Hall 1998; Brown 2001; Patten 2002; Batra 2010). Three of these did not require biochemical validation at longest follow‐up so there were 10 studies with one‐year sustained and validated quit rates contributing to the non‐group control comparisons (Curry 1988; DePaul 1989; Hollis 1993; DePaul 1994; Nevid 1997; Hall 2002; Romand 2005; Wilson 2008; Rovina 2009; Ramos 2010).

1 Comparisons between group therapy interventions and non‐group controls

1.1 Comparison of group versus self‐help programmes

Four studies compared a group programme with the same content provided by written materials alone. Curry 1988 tested two approaches, one emphasizing absolute abstinence and the other using a relapse prevention approach. Glasgow 1981 compared three different programmes suitable for self‐help use. Two were manuals using a structured behaviour therapy approach, the third was a multimedia quit kit with tips for quitting. All of these programmes lasted for eight weeks. García 2000 compared a 10‐session five‐week programme, a five‐session programme, and a five‐session programme plus self‐help manual, versus use of a self‐help manual alone. Rice 1994 used the shorter Smokeless programme. In this study the self‐help participants received five telephone calls during the two‐week programme to remind them to open the envelopes containing the appropriate booklet for the day. A further four trials included in this subgroup used a group programme as an adjunct to a televised cessation programme as well as self‐help materials. Three of these recruited smokers from worksites which had been randomly assigned to provide manuals or additional group meetings (DePaul 1987; DePaul 1989; DePaul 1994). In the fourth, smokers who had registered to receive a self‐help manual were randomized to receive the materials alone or additional group programmes (Gruder 1993). This study tested two different group programmes, both of three sessions. Their results are combined for comparison with self‐help.

Five studies did not use an identical programme manual for the group and self‐help conditions. In one the participants randomized to use self‐help were allowed a choice of manuals (Hollis 1993). In addition during a single meeting with the health counsellor they were encouraged to set a quit date, and one follow‐up telephone call was arranged. They were then mailed tip sheets and six bi‐monthly newsletters. Randomized participants who did not visit the health counsellor to receive their materials were mailed the appropriate programme, so a proportion of those assigned to group therapy effectively received a self‐help intervention. In a third treatment condition participants were randomized to make a choice between self‐help materials and attending a group programme, but we have not included this in a formal comparison. Hilleman 1993 gave no details of the programme used in the group format but the self‐help component consisted of a brief pamphlet. In this factorial trial of behavioural components and clonidine there was no evidence for an interaction with the pharmacotherapy, so the clonidine/placebo arms were collapsed. In Omenn 1988 participants with a stated preference for a group programme, and participants with no preference, were randomized to attend either a three‐ or an eight‐week group programme, or to use a self‐help guide alone. The two group programmes are combined in the analysis. Nevid 1997 compared a culturally‐tailored programme for Hispanic smokers with an enhanced self‐help programme which included one meeting and telephone contact. Batra 1994 compared a group and a self‐help approach.

1.2 Comparison of group therapy versus brief cessation support

Group therapy compared to physician or nurse advice

Of the 14 studies in this comparison, nine recruited from a healthcare setting. Two of the studies that compared different programme delivery formats also included an advice‐only control (Hollis 1993; Rice 1994). Hollis 1993 included a condition in which participants received the same 30‐second health provider advice as other arms, and in addition a brief pamphlet from the health counsellor. Rice 1994 included a no‐intervention control, but this included advice from a clinical nurse specialist to quit smoking because of the participants' cardiovascular health problems. In three other trials the physician advice was an alternative to a group programme. McDowell 1985 compared two different group programmes with an intervention in which participants were asked to attend a 15‐minute appointment with their physician for smoking cessation advice and a self‐help booklet. Sawicki 1993 compared referral to a group programme to referral for a 15‐minute physician advice session. Cottraux 1983 compared a three‐session group programme to two 10‐minute meetings with a doctor who prescribed a placebo. The authors describe this as a placebo control and the function of the doctor was to recommend the use of the tablets (which contained lactose) rather than to give other support. Bakkevig 2000 recruited community volunteers who were allocated to attend a group programme or to go and ask their physician for help. Only 36% consulted their general practitioner whilst 75% attended at least one programme session. In a factorial design with community volunteers, Hall 2002 randomized participants to pharmacotherapy with bupropion or nortriptyline or placebo, along with advice from a physician. Half of all these groups were randomized to an additional five‐session group‐based psychological intervention. Slovinec 2005 randomized women to either three physician visits alone or the addition of a group programme focused on stress management. Pisinger 2005 provided a single session of lifestyle counselling in a population‐based trial and offered the intervention group participation a six‐session group course over five months. Otero 2006 compared different schedules of group intervention to a single 20‐minute session. There was also randomization to nicotine patch or no‐patch conditions; the no‐patch conditions are used in this comparison. Wilson 2008 recruited people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease attending outpatient appointments. All received standardized brief advice to stop smoking. Dent 2009 included Veterans in a VA hospital who were referred by their physician to the smoking cessation pharmacy clinic. Participants either attended the “Vets without cigarettes” group‐based programme, which is based on theories of behaviour change, or received a standard care 10‐ to 15‐minute counselling phone call from a pharmacist. All participants were offered free bupropion or NRT. Ramos 2010, in addition to the individual counselling control noted above, included a "minimal intervention" condition consisting of brief physician advice to quit. All participants were offered NRT or bupropion at the physician’s discretion. In a cluster‐randomized trial in Danish primary care centres, Pisinger 2010 compared group‐based treatment to usual physician‐delivered advice; NRT was recommended to all participants.

Group therapy compared to health education

Rabkin 1984 compared a group programme to an intervention described as health education, consisting of a single group meeting which included a lecture on the health consequences of smoking. Participants decided on a method and made a commitment to quit, then had a single individual counselling session one week later. Romand 2005 compared the 'Five Day Plan' programme to a single session of information on health consequences.

1.3 Comparison of group therapy plus pharmacotherapy versus pharmacotherapy with brief support

In the comparisons above, pharmacotherapy was not systematically provided to all participants. Five trials included comparisons in which both intervention and control conditions had access to cessation medication. Ginsberg 1992 compared a prescription of nicotine gum plus a four‐week behavioural programme to nicotine gum plus two group sessions at which participants were given educational materials. Jorenby 1995 compared an eight‐week group programme to a minimal‐contact control group in which participants just used 22 mg or 44 mg nicotine patches and attended weekly assessment sessions without counselling. Otero 2006, as noted above, compared multiple sessions to a single 20‐minute session, and this comparison included arms allocated to use nicotine patch for eight weeks. Rovina 2009 compared group counselling (either CBT or supportive counselling) to brief (< 15 minutes) physician advice; all participants received bupropion. Gifford 2011 compared bupropion plus 10 weeks of combined group and individual counselling using functional analytic psychotherapy and acceptance and commitment therapy to bupropion and medication instructions only.

1.4 Comparison of group versus individual format therapy

Six trials compared a group‐based intervention with a multisession individual counselling intervention. Three had comparable intensity in terms of number of visits; one trial (Rice 1994), already noted in previous comparisons, compared group treatment with an individual intervention using the same Smokeless programme. Participants met with a clinical nurse specialist therapist for the same schedule of meetings as in the group format. The second in this category (Garcia 1989) compared group therapy to individual sessions with a doctor; all participants also received nicotine gum. The third compared the same schedule of group or individual meetings with a nurse who offered nicotine patch to participants willing to make a quit attempt (Wilson 2008). The other three studies had less individual than group contact time: Jorenby 1995, in addition to the minimal contact control used, also tested an individual counselling condition consisting of three brief sessions from a nurse at one, two and four weeks. Participants in each format were also randomly assigned to receive one of two doses of nicotine patch. Camarelles 2002 compared a seven‐session group therapy programme to two individual sessions, with encouragement to use nicotine patch for addicted participants. Ramos 2010 compared a group versus individual intervention for smokers in the preparatory stage of smoking cessation. Care was delivered by a "microteam" comprising a physician and a nurse, who also offered NRT or bupropion, as medically appropriate. The authors reported that individuals in the group intervention received six times more contact time than participants in the individual intervention. One trial (Smith 2001) previously contributing to this category now contributes to the relapse prevention review (Hajek 2013), because the two interventions compared were not offered until after the quit date.

1.5 Comparison of group therapy versus 'no intervention' controls

Nine trials included control conditions which we considered to have little or no specific content to encourage cessation. Hill 1993 used an exercise programme as a placebo control condition. The exercise arm did however receive a self‐help stop‐smoking pamphlet and encouragement to quit. McDowell 1985 included a control of smokers who had volunteered for the study but were asked only to complete smoking diaries and questionnaires at follow‐up. In one study (Grant 2003), the controls had access to standard smoking cessation resources at the substance abuse treatment centre they were attending. Schleicher 2012 recruited college students with elevated depressive symptoms to participate in six sessions of a CBT mood management smoking cessation group or a nutrition group with equal contact time, but no smoking‐related content. The remaining five trials had waiting‐list controls (Pederson 1981; Cottraux 1983; Leung 1991; Minthorn‐Biggs 2000; Zheng 2007).

2. Comparisons between different group programmes

Trials in this comparison tested a range of different components for enhancing abstinence as part of group‐based programmes. We now exclude trials of relapse prevention components because they are covered by a separate review (Hajek 2013). We include other skills training or cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) approaches that did not specifically address relapse prevention. We distinguish between trials that added a component and those that attempted to control for contact time by substituting an alternative component. We consider separately trials which specifically addressed mood management. We include as a separate subgroup in this comparison a trial comparing two public service programmes which differ in length.

2.1 Skills training

Nine trials contributed data to this category. Five trials substituted components in a programme, controlling for length. McDowell 1985 compared a nine‐session cognitive behaviour modification programme led by a psychologist to a programme led by a health educator. Goldstein 1989 compared two 11‐week courses; a behavioural programme which included skills training versus an educational programme which included non‐specific group support. Zelman 1992 compared two weeks of skills training or supportive counselling crossed with nicotine gum provision or a rapid smoking procedure. The nicotine exposure conditions are collapsed in this analysis. Ward 2001 added a cognitive counter‐conditioning (CCC) component to a four‐session programme which also included instruction in the use of NRT, and discussion of the concepts of self‐efficacy and the stages of change. In the CCC component participants jointly developed negative schema about smoking which they were to rehearse mentally whenever they had a cigarette. Rovina 2009, as noted above, compared CBT counselling to supportive group counselling composed of weekly sessions for one month followed by sessions every three weeks for the remaining 19 weeks. All participants in these groups were also given bupropion; the authors also included a condition in which participants attended CBT counselling but did not receive bupropion, but those data are not included in the meta‐analysis.

Four trials tested the effect of adding or extending sessions in a programme. Lando 1985 added six post‐quit sessions to a cessation programme using nicotine fading. Minthorn‐Biggs 2000 compared a 16‐session programme emphasizing social interaction and coping against a shorter American Lung Association programme. Huber 2003 compared a programme of five 90‐minute weekly meetings that included contracting, reinforcement, relaxation, skills training components to the same schedule of meetings lasting only 45 minutes where the focus was on sharing experiences. Nicotine gum was available to all participants. Otero 2006 compared programmes with three or four weekly hour‐long sessions to one or two sessions. Conditions with and without nicotine patch were collapsed in this analysis.

2.2 Mood Management

Seven studies investigated the use of a mood management intervention (either cognitive‐behavioural or behavioural activation) to manage the occurrence of negative mood. In five (Hall 1996; Brown 2001; Patten 2002; Brown 2007; Macpherson 2010) the contact time was matched. In two studies (Hall 1994; Hall 1998) the mood management intervention was compared with a shorter programme. Three of these studies had a factorial design with randomization to nicotine gum or placebo (Hall 1996), nortriptyline (Hall 1998) or bupropion (Brown 2007). These arms were collapsed in this meta‐analysis. Macpherson 2010 compared standard smoking cessation treatment to standard treatment plus behavioural activation, a treatment for depression that is one component of CBT, in which participants were taught to engage in non‐smoking reinforcing activities, activity monitoring and planning, and identification of values and goals. All participants also received eight weeks of nicotine patches.

2.3 Manipulation of group dynamics

Some of the studies already described had differences in group processes arising from the emphasis on skills or on discussion, but four studies specifically focused on manipulating the group dynamics. Digiusto 1995 compared a group programme which emphasized social support with one concentrating on self‐control. The organization of the groups differed, with the first emphasizing contact with other participants, the other using a didactic format and discouraging contact with other attenders. However other components were also varied, for example skills training instruction was given only in the self‐control group. The study hypothesis was that the treatments would show differential treatment effect with smokers of different personality types. Etringer 1984 and Lando 1991 manipulated the group environment in a less extreme way. Their programmes were intensive, lasting for 16 sessions over nine weeks. In an 'enriched cohesiveness' intervention, exercises focusing on the importance of self‐disclosure and feedback to other group members were introduced to facilitate positive group interaction. Etringer 1984 also compared a programme which included a satiation smoking procedure to one using nicotine fading. Their hypothesis was that group cohesiveness was already developed by the aversive smoking routine, so that the cohesiveness manipulation would be most effective in combination with nicotine fading. We collapse these two conditions. Schmitz 2007 compared a programme of CBT with a programme that focused on enhancing group support, both delivered over seven weekly meetings.

2.4 Other miscellaneous comparisons

Twelve studies do not fit within the broad categories above, either because they compared multiple different conditions, or because they did not use interventions comparable to other studies. They do not contribute substantially to the conclusions drawn in the review. All studies are described in the Results section, but not all are displayed in the summary meta‐analysis tables.

George 2000 used a programme developed to help smokers with schizophrenia and compared it to a standard programme. Two studies compared different procedures for altering smoking behaviour before the quit day. Glasgow 1989 compared two six‐week programmes, one emphasizing total abstinence, the other giving participants the option of cutting down their cigarette consumption if quitting was too difficult. Lando 1990 compared three programmes; the American Cancer Society Freshstart, the American Lung Association (ALA) Freedom from Smoking and a laboratory‐derived clinic approach. Bushnell 1997 compared Freshstart with a more intensive, small‐group approach. Glasgow 1981 compared three different group programmes, two based on social learning programmes developed by Pomerleau & Pomerleau, and Danaher & Lichtenstein, and the simpler I Quit Kit, intended to control for the non‐specific effects of a group programme. All groups had the same schedule of eight meetings. There were small numbers in each. García 2000 compared a 10‐session and a five‐session programme, each using the same components. Hertel 2008 manipulated participants expectations about smoking cessation during four sessions leading up to the target quit day, where participants in one group were encouraged to think about the positive consequences of smoking cessation (optimistic expectations) versus considering both the positive and negative consequences of smoking cessation (balanced expectations); the four sessions provided after the target quit day were identical between the conditions. In a sample of African‐American and mostly female smokers, Matthews 2009 compared a standard CBT‐plus‐NRT intervention to a culturally‐tailored CBT‐plus‐NRT intervention, in which approximately 40% of the session materials were modified to be culturally targeted. Only the results of one eight‐participant culturally‐tailored CBT group was reported. Batra 2010 compared standard treatment to targeted treatments for three high‐risk subgroups of smokers, including a highly dependent group, a depressive group, and a hyperactivity/novelty‐seeking group. All participants received the same amount of counselling plus NRT. In the meta‐analysis, the outcomes of the subgroups are collapsed to compare standard treatment compared to targeted treatment. We excluded from meta‐analysis participants in the standard treatment condition who were not classified as high‐risk smokers, because they were not randomized to treatment condition. Webb 2010 compared a six‐session CBT intervention culturally tailored for African‐American smokers to a time‐matched health education condition; all participants received eight weeks of nicotine patches. Aytemur 2012 evaluated the effect of adding a simultaneous eight‐week psychodrama training to a CBT group counselling plus smoking cessation pharmacotherapy intervention. Mueller 2012 compared a two‐week CBT programme to autogenic training for smokers on an inpatient alcohol detoxification unit.

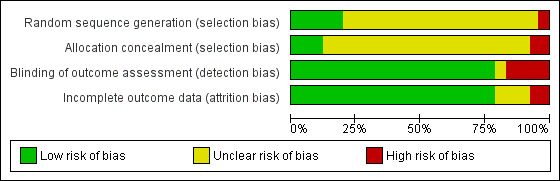

Risk of bias in included studies

Selection bias

All the included trials were described as randomized, but most gave insufficient detail about the method of random sequence generation to be judged as low risk. Most also gave too little detail to judge whether the allocation sequence was concealed until a participant was enrolled. The risk of selection bias was therefore unclear for most studies and the GRADE quality of evidence for most comparisons was accordingly downgraded from high to moderate. In cases where more than one group method was compared, and recruitment was continuous, participants were generally allocated to treatment groups on the basis of their sequence of arrival. The group was then randomized to treatment. In studies in which randomization was individual, randomization schedules were in some cases reported to be interrupted in order to allocate families or friends to the same group. Both these features mean that people in a particular group may be more similar than would be expected by chance. This undermines the statistical assumption used to estimate the variance, which is that they are typical of the population as a whole. The same principle also applies when participants are treated in groups, because each person's chance of success may be influenced by the group in which they find themselves. The possibility that success rates varied beyond chance between the groups given the same treatment can be tested, but the power to detect these differences will generally be very low. All these features of group therapy trials are likely to lead to an underestimate of the true variance, and therefore to the estimation of confidence intervals which are too narrow. In those trials which randomized entire worksites to programme type this factor is even more relevant.

Detection bias

Most studies validated self‐reported cessation biochemically and were assessed as being at low risk of detection bias. Ten studies (Pederson 1981; Cottraux 1983; Etringer 1984; DePaul 1987; Leung 1991; Gruder 1993; Minthorn‐Biggs 2000; Camarelles 2002; Grant 2003;Otero 2006) did not report any use of biochemical validation of self‐reported smoking cessation. Some other studies used a mixture of biochemical measures and verification by family or colleagues, or only sought biochemical verification in a random sample of quitters, or used biochemical validation only during the treatment period and not at longer‐term follow‐up. Where only a sample of quitters was verified it was not always clear whether overall quit rates were corrected for the disconfirmation rate in the sample. One study (Glasgow 1981) gave self‐reported quit rates and quitting as measured by carbon monoxide (CO) separately. In most arms the self‐reported rate was lower, so we have used this measure. In the only arm where the CO‐validated rate was more conservative, self‐reported rates favour self‐help over group treatment, so is still conservative with respect to the hypothesis of the review.

Attrition bias

The majority of studies reported the number of participants who had dropped out; in most cases they were explicitly assumed to be smokers. In most studies dropout rates were low and did not differ substantially between conditions, so we rated the risk of bias as low. Early post‐randomization dropouts were not always identified by treatment group. Where the information was available we have generally included them to base the analysis on the numbers randomized. Since the assumption that dropouts are continuing smokers is the same whatever their treatment group, measures of relative effect will only be altered greatly if there is differential dropout. If dropout rates are higher in a minimal treatment control group, then the relative effectiveness of the intervention group may be inflated. We have noted in the 'Risk of bias' tables if there were substantial differences between the numbers randomized and those followed up. In Gruder 1993 the numbers followed up were so much lower than the numbers randomized that we have used the numbers followed up, but report also the effect of using numbers randomized.

1.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

1 Comparisons between group therapy interventions and non‐group controls

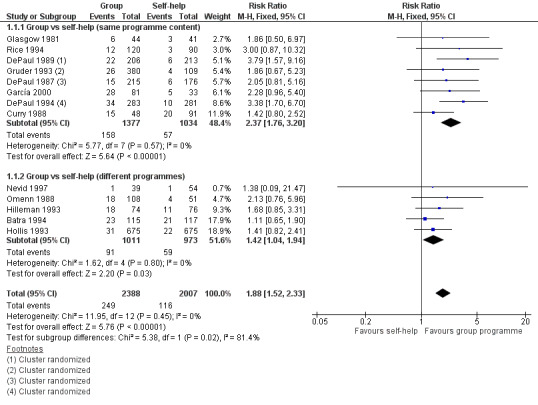

1.1 Comparison of group versus self‐help programmes

This comparison included 4395 participants from 13 studies. Results from all the studies had wide confidence intervals and only two detected a statistically significant effect. Quit rates in the self‐help control arms were typically 3% to 7% but were considerably higher in a few studies. In Table 1 we have assumed a control quit rate of 5% for estimating absolute effects. Pooling eight studies (N = 2411) that compared a group therapy programme with provision of the same content via a self‐help manual alone gave an estimated risk ratio (RR) of 2.37, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.76 to 3.20); Analysis 1.1.1) for the effectiveness of the addition of group meetings. The estimate was smaller and of only borderline significance for the other five studies (N = 1984) that used different programmes for the group and self‐help formats, with a risk ratio of 1.42 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.94; Analysis 1.1.2), but since there was no evidence of heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) among the 13 studies we pooled the subgroups giving an estimated RR of 1.88 (95% CI 1.52 to 2.33; Analysis 1.1). Figure 2

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Group‐format behavioural programmes vs other format, Outcome 1 Smoking cessation. Group programme vs self‐help programme.

2.

Forest plot of comparison 1.1: Group programme vs self‐help programme.

Sensitivity analyses

Four studies (DePaul 1987; DePaul 1989; Gruder 1993; DePaul 1994) were carried out during a televised smoking cessation series which all participants were encouraged to watch. The three DePaul studies also took place in worksite settings, with the worksites rather than individuals randomized to condition. Statistically therefore their results may be less precise. When these studies were excluded, the RR for all other studies with the same or different programmes was 1.57 (95% CI 1.22 to 2.02). The result is therefore robust whether or not worksite trials using cluster randomization, or studies using group programmes as adjuncts to mass media interventions, are included. A sensitivity analysis using numbers randomized rather than numbers followed up in Gruder 1993 had no effect on the results. Restricting the analysis to the five studies (Curry 1988; DePaul 1989; Hollis 1993; DePaul 1994; Nevid 1997) reporting sustained and validated cessation at 12 months also left conclusions unchanged.

1.2. Comparison of group therapy versus brief support interventions

Physician, nurse or pharmacist advice for controls

Fourteen trials with 7286 participants contributed to this comparison. Quit rates in the brief support/advice control were typically 9% to 16%, although three trials reported quit rates under 3% in the advice control groups (Hollis 1993; Pisinger 2010; Ramos 2010). One trial had no quitters in either arm (Wilson 2008). There was evidence of statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 59%); we report a pooled estimate but with a GRADE evidence quality of low, due to inconsistency as well as risk of bias. The pooled estimate suggested a small benefit of group support over brief support with a confidence interval just excluding no effect (RR 1.22, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.43). Of the trials, only Hollis 1993 and Bakkevig 2000 found a statistically significant superiority of a group programme compared to advice from a healthcare provider and a pamphlet. Of the trials that did not detect significant effects, three (Cottraux 1983; Rice 1994; Sawicki 1993) had point estimates favouring the control condition.

Health Education for controls

There was heterogeneity (I2 = 84%) between the results of the two trials (315 participants) with this type of control. Rabkin 1984 found similar cessation rates for a full group programme compared to an intervention with a single session of health education and one individual counselling session. Romand 2005 detected a significant benefit of the 'Five Day Plan' programme over a single session on health consequences.

1.3 Comparison of group therapy plus pharmacotherapy with pharmacotherapy alone

Five trials with 1523 participants evaluated the effect of adding a group support programme to NRT or bupropion (Rovina 2009) and some individual behavioural support. Quit rates in the control conditions were 25% to 30%, except for Gifford 2011 which reported a quit rate of 8%. None of the trials (Ginsberg 1992; Jorenby 1995; Otero 2006; Rovina 2009; Gifford 2011) detected significant effects. There was no evidence of heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) and the pooled estimate was not significant, although not ruling out a clinical benefit (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.33; Analysis 1.3). In a sensitivity analysis we included three trials from comparison 1.2 in which there was some offer of or access to pharmacotherapy although it was not provided systematically to all participants (Dent 2009; Pisinger 2010; Ramos 2010). This did not substantially change the estimate.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Group‐format behavioural programmes vs other format, Outcome 3 Smoking cessation. Group plus pharmacotherapy vs pharmacotherapy alone.

1.4. Comparison of group and individual format therapy

The six trials in this comparison included 980 participants. The quit rate for the controls receiving individual counselling was typically between 10% and 26%, but one trial had no quitters in either arm, and does not contribute data (Wilson 2008). Although there was some clinical heterogeneity in the precise details of the intervention and control conditions, there was little evidence of statistical heterogeneity between the five trials contributing data (I2 = 9%), so we calculated a pooled estimate. This did not detect evidence of a significant difference (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.28; Analysis 1.4). In two of the trials (Garcia 1989; Jorenby 1995), NRT was offered to all participants, in one trial (Ramos 2010), NRT or bupropion were offered to all participants, and in two others (Camarelles 2002; Wilson 2008) about half of the participants used NRT. It is possible that when pharmacotherapy is being used, small differences in type and amount of behavioural support may not affect long‐term success.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Group‐format behavioural programmes vs other format, Outcome 4 Smoking cessation. Group programme vs individual therapy.

1.5 Group therapy compared to 'No Intervention' controls

Nine trials with 1098 participants contributed (Analysis 1.5). Heterogeneity was moderate (I2 = 55%). Because of this, the estimate size is unreliable (RR 2.60, 95% CI 1.80 to 3.76). Eight trials had higher quit rates with group programmes compared to a no‐intervention or a minimal‐contact control, but the two highly weighted studies had amongst the smallest effects.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Group‐format behavioural programmes vs other format, Outcome 5 Smoking cessation. Group vs 'no intervention' controls.

2 Comparisons between different formats of group programme

2.1 Skills Training/Cognitive‐Behavioural components

Nine studies with 1599 participants compared group format programmes that differed in their use of specific components such as skills training or cognitive‐behavioural therapies. We distinguished between programmes that were matched for contact time (McDowell 1985; Goldstein 1989; Zelman 1992; Ward 2001; Rovina 2009) and those where the additional components increased the duration (Lando 1985; Minthorn‐Biggs 2000;Huber 2003; Otero 2006). Neither subgroup had evidence of much heterogeneity and the overall heterogeneity was also low (I2 = 10%), so we focus on the pooled estimate for all studies. Now that interventions addressing relapse prevention are not included the borderline significance disappears and there is no evidence for a benefit of more complex interventions (RR 1.16, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.37; Analysis 2.1). Only one trial (Goldstein 1989) showed a statistically significant benefit at long‐term follow‐up. The analysis includes almost 1600 participants but most of these were contributed by Otero 2006, with the other studies being small.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Comparisons between different group programmes [Outcome Long term cessation for all comparisons], Outcome 1 "Skills training".

2.2 Mood Management components

Seven trials with 1367 participants tested specific interventions to help manage mood, using either CBT or behavioural activation. Five studies were matched for contact time (Hall 1996; Brown 2001; Patten 2002; Brown 2007; Macpherson 2010) and two had longer intervention than control programmes (Hall 1994; Hall 1998). There was little or no heterogeneity evident in the subgroups and none when pooling all studies (I2 = 0%). The pooled estimate did not detect evidence of an effect (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.32; Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Comparisons between different group programmes [Outcome Long term cessation for all comparisons], Outcome 2 Mood management.

2.3 Manipulation of Group Dynamics

There was no evidence from the four trials with 702 participants (Etringer 1984; Lando 1991; Digiusto 1995; Schmitz 2007) that there was an effect on cessation of attempts to change the interaction between participants in a group programme. There was little heterogeneity; none of the trials detected significant long‐term effects and the pooled estimate provided no evidence of a difference (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.46; Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Comparisons between different group programmes [Outcome Long term cessation for all comparisons], Outcome 3 Manipulation of group dynamics.

2.4 Other miscellaneous comparisons

The trials briefly noted here were mostly small and did not show significant long‐term effects on cessation, although with wide confidence intervals. One trial with 154 African‐American smokers (Webb 2010) did detect a benefit of a cognitive behavioural programme, compared to a contact matched group health education programme, with all participants given nicotine patches (RR 2.27 95% CI 1.20 to 4.29; Analysis 2.4.1). George 2000 (n=45) failed to show evidence that a programme designed for smokers with schizophrenia had a greater benefit than a standard intervention (RR 1.65, 95% CI 0.37 to 7.25; Analysis 2.4.2). Glasgow 1989 (n=66) did not detect a difference in six‐month quit rates using programmes differing in their emphasis on abstinence or controlled smoking (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.32 to 2.78; Analysis 2.4.3). Pharmacotherapy use was similar between the psychodrama versus CBT‐only groups (80% versus 73%). Matthews 2009 did not find that culturally tailoring smoking cessation materials increased cessation rates (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.28 to 3.81; Analysis 2.4.4), although they only reported the outcomes from one group of eight participants in the culturally‐tailored intervention. Batra 2010 (n=193) did not detect an overall effect of targeted versus standard treatment for three subgroups of smokers: highly dependent, depressive, and hyperactivity/novelty‐seeking (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.69; Analysis 2.4.5), however, they reported higher rates of abstinence in the targeted versus standard treatment among the depressive subgroup (29% versus 12%). Moreover, more participants in the culturally‐tailored intervention used NRT (88% versus 51%). Mueller 2012 (n=103) did not detect a significant difference in cessation rates between a CBT smoking cessation group programme compared to a relaxation‐only group among smokers in a residential alcohol detoxification program, with the direction of effect favouring relaxation; none of the CBT group participants was abstinent at the six‐month follow‐up (RR 0.13, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.55; Analysis 2.4.5). Aytemur 2012 (n=127) did not find that adding psychodrama training to a CBT group programme improved smoking cessation outcomes (RR 1.39, 95% CI 0.89 to 2.16; Analysis 2.4.6).

The other trials are not shown graphically. Lando 1990 found that the American Lung Association (ALA) Freedom from Smoking programme was more successful than the American Cancer Society (ACS) Freshstart programme. Sustained one‐year quit rates were 12%, 19% and 22% for the ACS, ALA and clinic‐derived programme respectively. This was a large, multicentre study, and since treatment was allocated by group the authors estimated the design effect to allow for the correlation in outcome between people treated together. The corrected Chi2 for the three‐way comparison was significant (P < 0.014) for the one‐year sustained abstinence measure. The difference between the ALA and Lando programmes was not significant at one year. Bushnell 1997 compared Freshstart to a more intensive clinic‐based approach. This study did not show significant long‐term differences between the programmes, although early results favoured the intensive approach. Glasgow 1981 also compared three different programmes. They found no significant differences but numbers allocated to each programme were small. In García 2000 a five‐week 10‐session programme was associated with lower 12‐month quit rates than a five‐session programme (16% versus 39%). The rates for the more intensive programme were significantly lower when compared to a five‐session programme combined with a self‐help manual (16% vs 48%, P < 0.05). Hertel 2008 manipulated pre‐quit expectations (optimistic versus balanced) for four sessions, followed by four sessions of identical treatment. They found no overall difference in outcomes for people given optimistic versus balanced expectations before quitting (19% versus 21%), with some evidence of interaction with participants' prior experiences of quitting.

Take‐up rates for group programmes

The variation in take‐up rates for group therapy was partly determined by the method of recruitment and randomization. However, even in trials where eligible smokers agreed to attend group meetings prior to randomization, the non‐participation rate was often high. Curry 1988 enrolled participants who attended an information meeting. More group participants (88%) than self‐help participants (59%) began treatment (defined as completing the first week of self‐monitoring), and completed treatment. Because of the differential dropout the difference in quit rates is greater when we conducted an intention‐to‐treat analysis (including all randomized participants) than when only those who began treatment are included. Participation in the Glasgow 1981 trial was higher, with almost all those enrolled taking part and available for six‐month follow‐up.

Attrition following randomization was particularly high in Gruder 1993, which was carried out in conjunction with a television programme, because eligible smokers who had registered by mail for support materials were randomized before they were contacted. Only 70% could be reached and 62% scheduled for group meetings. Non‐participation at this stage was due to lack of interest or problems with timing or location of meetings. Of those who were scheduled, 50% then failed to attend any meetings.

Rice 1994 also had a high non‐attendance rate, even though participants were volunteers. Overall 34% dropped out of the trial on learning their treatment allocation. Thirty‐one per cent of those randomized to the group treatment refused to participate, whilst the dropout from the follow‐up‐only group was 48%. Hertel 2008 reported that only 79% of participants who completed the baseline session and were randomized to treatment attended at least two out of the four baseline sessions. On the other hand, Cottraux 1983 reported that just over half those enrolled attended all three behaviour therapy sessions, Batra 2010 reported that 74% of participants attended at least five out of six sessions, and Schleicher 2012 reported that 75% of participants attended at least four out of six sessions. Hilleman 1993 also did not report any dropout from group treatment, but this trial involved volunteers for a drug trial, and is probably not typical.

The lowest participation rates were seen in Hollis 1993 and Pisinger 2010. Hollis 1993 recruited smokers during visits to primary care offices. Of those randomized for referral to a group programme, 11% chose to attend, whilst of those given a choice of self‐help or groups just 8% attended a group programme. Pisinger 2010 cluster‐randomized GPs to recruit participants to a group counselling programme, an internet‐based programme, or usual care. Only 7% of participants attended a counselling group and 16% logged into the internet programme. A higher take‐up rate was seen in a Norwegian trial (Bakkevig 2000) which allocated community volunteers to either a smoking cessation group, which 75% attended, or to visit their physician for help (GP), which only 36% chose to do. In one study not included because the intervention offered NRT as well as referral to a behavioural programme as a covered benefit in a health plan, only 1.2% of the intervention group participated in a behavioural programme (Schauffler 2001). Pisinger 2005 had a 26.5% take‐up rate amongst people given brief counselling and offered group support.

Discussion

This review provides evidence that a behaviour therapy programme delivered in a group format aids smoking cessation. The effect is clearest when group support is compared to a self‐help programme providing information in written materials. We estimated that if five in 100 people could give up for at least six months assisted by written materials, eight to 12 in 100 could quit when given group support. We rate the GRADE evidence quality as moderate because these trials were done some years ago and most were at unclear risk of bias. Group support was also more effective than brief support such as advice from a physician or nurse, but we judged the GRADE quality to be low, because of the possibility of bias and variability in the effect size in different studies; see Table 1.

Combining the results of five trials that examined group therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy did not detect a significantly increased quit rate for combined therapy over pharmacotherapy without group support. In all studies the comparison arm had at least brief behavioural support. This finding was not changed by the addition of three studies for this update (Otero 2006, Rovina 2009; Gifford 2011). We graded the evidence quality as moderate, downgraded due to imprecision. The overall increase in success rates attributable to pharmacotherapy might make small relative differences attributable to the type and amount of behavioural support more difficult to detect. The Cochrane Review of individual counselling (Lancaster 2017) has noted a similar failure to detect a significant additional benefit of individual counselling when added to the systematic use of NRT. In both cases evidence comes from a small number of trials (Jorenby 1995 contributes data to both reviews). A separate Cochrane Review (Stead 2015) has assessed the effect of increasing the amount of any type of behavioural support when used alongside pharmacotherapy. It analysed 47 studies including relevant studies from this review, and concluded that "increasing the amount of behavioural support is likely to increase the chance of success by about 10% to 25%". The confidence interval for the estimate based on five trials is consistent with a similar small benefit. In the absence of clear evidence to the contrary, it seems reasonable to assume that behavioural interventions and pharmacotherapies independently contribute to successful quitting.

The results from six studies provide no evidence that group therapy is more effective than individual counselling, whether or not the number of sessions was matched. There was therefore a lack of evidence that meeting with a group of other smokers was a critical element in an intensive smoking cessation programme. In two of the trials (Garcia 1989; Jorenby 1995), NRT was offered to all participants, in one trial (Ramos 2010) all participants were offered NRT or bupropion at the physician's discretion, and in two others (Camarelles 2002; Wilson 2008) about half of the participants used NRT. As suggested above, the use of pharmacotherapy may make it difficult to detect differences between the effects of behavioural components, if the relative increase in quit rates is small. Additionally, in Ramos 2010 the treatment team for each arm comprised a nurse and a physician, but the group intervention was more likely to be delivered by the nurse and the individual intervention was more likely to be delivered by the physician, which may have influenced the outcomes. Although we did not specifically seek cost data, none of these studies was designed to compare the costs of different formats. Using a group format ought to allow more people to be treated by a therapist, and therefore could be more cost‐effective if outcomes were similar, but there is not enough evidence about comparative efficacy.

Problems of conducting a systematic review of behavioural interventions should be noted. First, many trials of behavioural interventions use multiple treatment arms in an attempt to identify the precise therapeutic element leading to success. This makes the pre‐definition of explicit comparison groups difficult. Second, as with all behavioural as opposed to pharmacological therapies, the choice of an appropriate control condition presents problems when evaluating efficacy. There is no obvious equivalent for the drug placebo to control for the non‐specific effects of a treatment method. Evaluating group therapies against a waiting‐list control does not provide very good evidence for the specific effect of the group format. Whilst we took account of the broad nature of the support offered to the control group when pooling studies, variation in the components used as part of, for example, a usual care control, may still give rise to heterogeneity. Treatment effects could be underestimated if those studies using effective interventions tended to provide relatively helpful usual care or brief advice. An ongoing systematic review is conducting a detailed analysis of behavioural intervention and control elements, and is expected to provide more evidence about this (de Bruin 2016).

A limitation of research in which participants are treated in groups is that typically there may be only two or three groups in each treatment condition. Participants' chances of success are almost certainly not completely independent. There may be variation by the group in which they were treated, due to aspects of the group process. This aspect is generally ignored in trial analyses. We also cannot exclude the possibility of publication bias. Although group programmes have been widely offered for smoking cessation, often under the auspices of cancer prevention or lung health charities, we found relatively few studies meeting our criteria. It is possible that there are other published or unpublished studies we have not located.

This review has taken a broad approach to group programmes, without distinguishing between treatments on the basis of their theoretical approach, therapists or intensity. There is still limited evidence from which to identify those elements of group therapy which are most important for success. In the main analyses there are too few studies to compare subgroups of studies according to content, provider or length. The number of studies directly comparing different programmes is also small, although now that group therapy is well established as a treatment, more effort is being devoted to optimizing interventions. The largest number of newly included studies in this update were in this category. Some studies compare programmes using different theoretical approaches. Most commonly, they distinguish between approaches that stress the acquisition of specific skills, and those that aim to increase motivation and confidence in quitting without emphasis on cognitive and behavioural skills, (e.g. Hall 1998; Zelman 1992; Brown 2001 for comparisons between approaches). At present the evidence supporting the use of additional skills‐based components is weak, although it is consistent with the US guideline meta‐analyses (Fiore 2008), discussed further below. Although pooled point estimates suggest a small benefit, confidence intervals are sensitive to the studies included and the way interventions are categorized.

Others focus on additional components, such as adding psychodrama (as in Aytemur 2012), tailoring interventions for different cultural groups (e.g. Matthews 2009), or manipulating pre‐quit expectations (Hertel 2008). However, none of these studies detected differences between groups. Furthermore, at this time there are few similarities between studies to allow for pooled analyses.

A further focus of research is to identify whether specific subgroups of smokers benefit differentially (e.g. Batra 2010). This could allow tailoring of intensive interventions for specific target groups, for example people with histories of depression or other addictions, or with smoking‐related medical problems (Brandon 2001). Research addressing these questions is likely to contribute more to future updates of these reviews. At the moment there is not sufficient evidence to support using one programme type over another for smokers with any particular characteristics. A number of studies that were included in earlier versions of this review are now separately considered in a Cochrane Review of relapse prevention interventions (Hajek 2013). That review has detected no evidence of proven effective behavioural approaches for reducing relapse rates at long‐term follow‐up.

The US Public Health Service Guideline, Treating Tobacco Use & Dependence, updated in 2008 (Fiore 2008), is based on meta‐analyses using logistic regression. This approach allows the contribution of data from trials which did not directly compare different formats. The guideline includes estimates of the comparative cessation rates using different formats for delivering interventions. In the Guideline analysis, the estimated odds ratio (OR) for success using group counselling compared to no intervention was 1.3 (95% CI 1.1 to 1.6, Table 6.13). In an earlier version of the guideline the estimated benefit of group therapy was somewhat larger (Fiore 1996). Another guideline meta‐analysis considered the components provided within group and individual counselling programmes. This suggested that general problem‐solving elements (including skills training, relapse prevention and stress management) were likely to be beneficial (OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.3 to 1.8, Table 6.18). Intra‐treatment social support (OR 1.3, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.6) was also recommended. The analysis did not show relaxation exercises, contingency contracting, cigarette fading or negative affect components to be useful. The guideline authors stress that the strength of evidence underlying recommendations on use of these components is not of the highest level because of the correlation of the types of counselling and behavioural therapies with other treatment characteristics such as programme length or type of therapist. The conclusions of this Cochrane Review are consistent with the guideline finding in relation to the inclusion of general problem‐solving components, and are strengthened by being limited to unconfounded comparisons. They are still limited by the small number of studies and the heterogeneity of approaches.

There is further evidence from studies which did not meet our inclusion criteria that group programmes are effective. The Lung Health Study (Kanner 1996) was a trial of a smoking intervention and a bronchodilator in smokers with mild pulmonary obstructive disease. The programme consisted of 12 weeks of group therapy with a cognitive‐behavioural approach, and nicotine gum was available to all participants. In addition they all received a strong physician message about quitting followed by a meeting with a smoking intervention specialist. A maintenance programme was also provided. We excluded the study from our meta‐analysis because the effect of the group was confounded by the effects of nicotine replacement. However the quit rate achieved is greater than might be expected from the use of NRT alone, and it is reasonable to assume that the group programme contributed to the effect. Twenty‐two per cent of the intervention participants achieved smoking cessation for five years compared to 5% of the usual‐care control . Nine‐year follow‐up of a cohort of people treated in large group‐format community‐based interventions suggests a quit rate somewhere between 16% and 48%, depending on the extent to which the 34% of the cohort reached were representative of those treated (Carlson 2000). More recent results based on longer follow‐up report a difference in health outcomes between the intervention groups (Anthonisen 2005).

The drawback to group programmes as a public health strategy is their limited reach to the smoking population. Participation rates in a number of the studies considered here were low. Participating smokers need to be sufficiently motivated not only to attempt to stop, but also to commit themselves to the time and effort involved in attending meetings.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is reasonable evidence that groups are better than self‐help, and other less intensive interventions, in helping people stop smoking, although they may be no better than advice from a healthcare provider. There is not enough evidence to determine how effective they are in comparison to intensive individual counselling. From the point of view of the consumer who is motivated to make a quit attempt, it is probably worth joining a group if one is available; it will increase the likelihood of quitting. Group therapy may also be valuable as part of a comprehensive intervention which includes pharmacotherapy. From a public health perspective, the impact of groups on smoking prevalence will depend on their uptake. Providers need to make a judgement about the cost effectiveness of the gains achieved by group therapy compared to other interventions.

Implications for research.

The general efficacy of multicomponent programmes which include problem‐solving and social support elements has been established. Demonstrating the efficacy of specific components or procedures requires large sample sizes which can be difficult to achieve, given the difficulty of attracting smokers to intensive programmes. Identifying subgroups of smokers who are differentially helped by particular components may be possible, and this could lead to the development of targeted interventions.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 15 December 2016 | New search has been performed | Searches updated, 13 new studies included. 'Summary of findings' table added |