Abstract

Background

To limit long‐term sick leave and associated consequences, insurers, healthcare providers and employers provide programmes to facilitate disabled people's return to work. These programmes include a variety of coordinated and individualised interventions. Despite the increasing popularity of such programmes, their benefits remain uncertain. We conducted a systematic review to determine the long‐term effectiveness of return‐to‐work coordination programmes compared to usual practice in workers at risk for long‐term disability.

Objectives

To assess the effects of return‐to‐work coordination programmes versus usual practice for workers on sick leave or disability.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2016, Issue 11), MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL and PsycINFO up to 1 November 2016.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that enrolled workers absent from work for at least four weeks and randomly assigned them to return‐to‐work coordination programmes or usual practice.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened titles, abstracts and full‐text articles for study eligibility; extracted data; and assessed risk of bias from eligible trials. We contacted authors for additional data where required. We conducted random‐effects meta‐analyses and used the GRADE approach to rate the quality of the evidence.

Main results

We identified 14 studies from nine countries that enrolled 12,568 workers. Eleven studies focused on musculoskeletal problems, two on mental health and one on both. Most studies (11 of 14) followed workers 12 months or longer. Risk of bias was low in 10 and high in 4 studies, but findings were not sensitive to their exclusion.

We found no benefits for return‐to‐work coordination programmes on return‐to‐work outcomes.

For short‐term follow‐up of six months, we found no effect on time to return to work (hazard ratio (HR) 1.32, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.93 to 1.88, low‐quality evidence), cumulative sickness absence (mean difference (MD) −16.18 work days per year, 95% CI −32.42 to 0.06, moderate‐quality evidence), the proportion of participants at work at end of the follow‐up (risk ratio (RR) 1.06, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.30, low‐quality evidence) or on the proportion of participants who had ever returned to work, that is, regardless of whether they had remained at work until last follow‐up (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.19, very low‐quality evidence).

For long‐term follow‐up of 12 months, we found no effect on time to return to work (HR 1.25, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.66, low‐quality evidence), cumulative sickness absence (MD −14.84 work days per year, 95% CI −38.56 to 8.88, low‐quality evidence), the proportion of participants at work at end of the follow‐up (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.15, low‐quality evidence) or on the proportion of participants who had ever returned to work (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.09, moderate‐quality evidence).

For very long‐term follow‐up of longer than 12 months, we found no effect on time to return to work (HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.17, low‐quality evidence), cumulative sickness absence (MD 7.00 work days per year, 95% CI −15.17 to 29.17, moderate‐quality evidence), the proportion of participants at work at end of the follow‐up (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.07, low‐quality evidence) or on the proportion of participants who had ever returned to work (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.02, low‐quality evidence).

We found only small benefits for return‐to‐work coordination programmes on patient‐reported outcomes. All differences were below the minimal clinically important difference (MID).

Authors' conclusions

Offering return‐to‐work coordination programmes for workers on sick leave for at least four weeks results in no benefits when compared to usual practice. We found no significant differences for the outcomes time to return to work, cumulative sickness absence, the proportion of participants at work at end of the follow‐up or the proportion of participants who had ever returned to work at short‐term, long‐term or very long‐term follow‐up. For patient‐reported outcomes, we found only marginal effects below the MID. The quality of the evidence ranged from very low to moderate across all outcomes.

Plain language summary

Effect of return‐to‐work coordination programmes for workers on sick leave

What is the aim of this review?

The aim of this review was to compare the effect of return‐to‐work coordination programmes to usual practice in workers on sick leave or disability.

Key messages

We found that return‐to‐work coordination programmes had no effects compared to usual practice on return‐to‐work outcomes. These outcomes were time to return to work, cumulative sickness absence, the proportion of workers at work at the end of the follow‐up and the proportion who had ever returned to work. We found no benefits in the short term, long term or very long term.

We found only small benefits in patient‐reported outcomes. All these effects were smaller than the so‐called minimal clinically important difference.

What was studied in the review?

Returning long‐term sick‐leave workers back to work is important for society, employers and certainly for workers themselves. Possible interventions for this purpose are return‐to‐work coordination programmes, also described as case management or collaborative care. These programmes involve a number of health professionals collaborating with the workers to help them overcome their incapacity to work. Return‐to‐work coordination programmes vary in duration and design. In general, they include an assessment of the obstacles impeding a return to work and an individualised plan to eliminate barriers and return workers to employment. Treatment components may include counselling, physical or occupational therapy, and specialist care.

Return‐to‐work coordination programmes require substantial resources. However, it is uncertain how effective they are.

What are the main results of the review?

We included 14 randomised controlled trials involving 12,568 workers with musculoskeletal or mental health problems. Workers had to be on sick leave for a minimum of four weeks.

At short‐term follow‐up of six months, return‐to‐work coordination programmes may make little or no difference to time to return to work (low‐quality evidence), probably make little or no difference to cumulative sickness absence (moderate‐quality evidence), may make little or no difference to the proportion of participants at work at end of the follow‐up (low‐quality evidence). Finally, we are uncertain whether the programmes improve the proportion of participants who had ever returned to work as the quality of the evidence has been assessed as very low.

At long‐term follow‐up of 12 months, return‐to‐work coordination programmes may make little or no difference to time to return to work, cumulative sickness absence or the proportion of participants at work at end of the follow‐up (all low‐quality evidence) and they probably make little or no difference to the proportion of participants who had ever returned to work (moderate‐quality evidence).

At very long‐term follow‐up of longer than 12 months, return‐to‐work coordination programmes may make little or no difference to time to return to work (low‐quality evidence), probably make little or no difference to cumulative sickness absence (moderate‐quality evidence), and may make little or no difference to the proportion of participants at work at end of the follow‐up and to the proportion of participants who had ever returned to work (both low‐quality evidence).

We found only small benefits in patient‐reported outcomes including pain, ability to function, depression and anxiety. All these effects were smaller than the so‐called minimal clinically important difference.

As we found so much low‐ and very low‐quality evidence it means that new research is likely to change the results.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

We searched scientific literature until 1 November 2016.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Return to work coordination programmes compared to usual practice for improving return to work in workers on sick leave.

| Return to work coordination programmes compared to usual practice for improving return to work in workers on sick leave | |||||

| Patient or population: workers on sick leave Intervention: return‐to‐work coordination programmes Comparison: usual practice | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with usual practice | Risk with return‐to‐work coordination programmes | ||||

| Time to return to work ‐ short‐term follow‐up: 6 months |

— | — | HR 1.32 (0.93 to 1.88) | 161 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b |

| Time to return to work ‐ long‐term follow‐up: 12 months |

— | — | HR 1.25 (0.95 to 1.66) | 1935 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb,c |

| Time to return to work ‐ very long‐term follow‐up: more than 12 months | — | — | HR 0.93 (0.74 to 1.17) | 474 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b |

| Cumulative sickness absence in work days ‐ short‐term follow‐up: 6 months | The mean cumulative sickness absence was 79.14 work days | The mean cumulative sickness absence in the intervention group was 16.18 work days lower (32.42 lower to 0.06 higher) | — | 113 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb |

| Cumulative sickness absence in work days ‐ long‐term follow‐up: 12 months |

The mean cumulative sickness absence was 144 work days | The mean cumulative sickness absence in the intervention group was 14.84 work days lower (38.56 lower to 8.88 higher) | — | 1339 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb,c |

| Cumulative sickness absence in work days ‐ very long‐term follow‐up: more than 12 months |

The mean cumulative sickness absence was 466 work days | The mean cumulative sickness absence in the intervention group was 7 work days higher (15.17 lower to 29.17 higher) | — | 8052 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb |

| Proportion at work at end of the follow‐up ‐ short‐term follow‐up: 6 months | 53 per 100 | 56 per 100 (46 to 69) | RR 1.06 (0.86 to 1.30) | 1388 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b |

| Proportion at work at end of the follow‐up ‐ long‐term follow‐up: 12 months |

60 per 100 | 64 per 100 (59 to 69) | RR 1.06 (0.99 to 1.15) | 3061 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b |

| Proportion at work at end of the follow‐up ‐ very long‐term follow‐up: more than 12 months |

53 per 100 | 49 per 100 (43 to 56) | RR 0.94 (0.82 to 1.07) | 815 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b |

| Proportion who had ever returned to work ‐ short‐term follow‐up: 6 months |

57 per 100 | 49 per 100 (36 to 68) | RR 0.87 (0.63 to 1.19) | 675 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c |

| Proportion who had ever returned to work ‐ long‐term follow‐up: 12 months | 69 per 100 | 71 per 100 (67 to 75) | RR 1.03 (0.97 to 1.09) | 3822 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb |

| Proportion who had ever returned to work ‐ very long‐term follow‐up: more than 12 months |

75 per 100 | 71 per 100 (66 to 77) | RR 0.95 (0.88 to 1.02) | 938 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; OR: odds ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

a Downgraded 1 level for risk of bias (attrition bias, reporting bias). b Downgraded 1 level for imprecision (confidence interval encloses negative and positive effect or population size less than 400). c Downgraded 1 level for inconsistency (substantial heterogeneity).

Background

Description of the condition

Most industrialised countries recognise long‐term sick leave as an increasing public health problem (Canadian Human Rights Commission 2007; Henderson 2005; OECD 2010), which affects society through loss of productivity and work disability claims (Arends 2012). NICE 2009 defines long‐term sick leave as an absence from work for at least four weeks.

Statistics from the Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development (OECD) countries show that 5.7% of the working age population (20 to 64 years of age) received disability benefits in 2010 (OECD 2014 a), ranging from 0.6% to 10.4% across countries. Mental health problems were the leading causes for sick leave, followed by musculoskeletal disorders (Arends 2012; Henderson 2005). For workers, long‐term sick leave implies health risks as well as occupational, social and economic deprivation (Henderson 2005; OECD 2003).

The duration of sick leave and the likelihood to return to work have an inverse relationship: being sick‐listed for six months or longer resulted in an 80% chance of remaining off work for five years (Waddell 2006). Once on disability benefits, people tend not to go back to work; they rather move onto another benefit or retire (OECD 2010).

Description of the intervention

To limit long‐term sick leave and associated consequences, insurers, healthcare providers and employers may provide special programmes that facilitate workers' return. These programmes run under a variety of names, such as case management, integrated or collaborative care, or return‐to‐work coordination programmes. They differ widely in content, set‐up and duration, and their components include a variety of interventions, such as occupational therapy, physiotherapy, psychological therapy, medical interventions, workplace ergonomics, education and social therapy. All components are individually adjusted to the worker's needs.

Despite increasing popularity, there is limited evidence regarding the short‐ and long‐term effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness of return‐to‐work programmes (Berchtold 2006; Hofmarcher 2007; NICE 2009; Palmer 2012).

How the intervention might work

Return‐to‐work programmes identify barriers that may prevent workers from successfully returning to work and assess their strengths and limitations. A designated coordinator then provides the worker with individually tailored interventions to overcome these barriers (Craig 2013).

Possible barriers are:

physical (e.g. a painful joint due to osteoarthritis, chronic obstructive lung disease);

mental (e.g. low resilience due to depression or a personality disorder);

functional (e.g. low endurance, minor flexibility to adapt to new situations, restricted range of motion);

workplace‐related (elements of the workplace may be unsuitable, e.g. lack of job autonomy); and

psychosocial (e.g. interpersonal problems with the supervisor, challenging family situation, burdening financial situation).

Early multidisciplinary interventions seem appropriate and promising ways to return people to work (Department for Work and Pensions 2013; Hoefsmit 2012).

Effective return‐to‐work coordination programmes depend on good communication between the various stakeholders (i.e. workers and their families, employers, supervisors, healthcare providers, and insurers) and on smooth coordination of the various components included in the programme. The return‐to‐work coordinator plays a pivotal role by ensuring communication and a joint understanding regarding expectations for all stakeholders (IWH 2007). Face‐to‐face contact between the worker and the return‐to‐work coordinator favours an optimal selection and implementation of the return‐to‐work interventions and intensifies the worker's accountability to the programme.

Why it is important to do this review

Long‐term sick leave results in serious consequences for individuals and other stakeholders as well as for the society at large. Return‐to‐work coordination programmes may respond to this challenge, but they represent complex and costly interventions requiring substantial human and financial resources. The sparse and heterogeneous evidence on their effectiveness calls for an investigation into their impact.

We published a former version of this review (Schandelmaier 2012). The importance and timeliness of the subject required an update with a new search for relevant studies.

Objectives

To assess the effects of return‐to‐work coordination programmes versus usual practice for workers on sick leave or disability.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) irrespective of their language of publication. We included studies reported as full text, those published as abstract only and unpublished data.

Types of participants

We included studies in adults of working age (16 to 65 years) who:

were on full‐ or part‐time sick leave continuously for at least four weeks or were receiving long‐term disability benefits; and

were employed at the time of sick‐listing.

At least 80% of the participants in a study had to fulfil both criteria. We included studies irrespective of the cause of sick leave or disability, the setting or the benefit scheme (e.g. private or government provider).

Types of interventions

Experimental intervention

We included trials comparing return‐to‐work coordination programmes to usual practice. No uniform definition of return‐to‐work coordination programmes exists. We defined such programmes as follows.

The objective is to promote return to work.

The return‐to‐work coordinator(s) and the affected worker have at least one face‐to‐face contact.

The process starts with an assessment of the worker's needs and leads to an individually tailored return‐to‐work plan.

The implementation of the return‐to‐work plan is managed by the return‐to‐work coordinator(s).

In our definition, 'individually tailored' implies a personalised set of actions directed at the worker, the employer, the workplace, or other factors in the return‐to‐work process. Adjustment to the needs of the worker within a pre‐defined action, such as individually tailored physical therapy, was not sufficient to meet the criterion. Consequently, the return‐to‐work plan had to allow for more than one possible action.

We included studies where public or private insurers offered return‐to‐work coordination programmes to people on sick leave due to impaired health ('in‐house programmes'). In addition, we considered return‐to‐work coordination programmes that could be contracted by insurers ('commissioned programmes'). We assumed that both have comparable effects as long as they share the goal of returning to work.

We excluded employer‐initiated return‐to‐work coordination programmes. Such programmes encounter fewer barriers in implementing workplace‐directed interventions than insurers or third‐party return‐to‐work coordinators and are typically not available for smaller companies.

Control intervention

We classified the level of support for the control groups as low, moderate or high. To get a better understanding of what usual practice in the different countries entailed, we contacted all authors and asked them to provide additional information.

We classified usual practice by a healthcare provider (e.g. a general practitioner or a physical therapist or other generally accessible rehabilitation professionals) as a low level of support. We classified conventional case management (e.g. as provided by the municipality or the insurer), usual sickness guidance by an occupational practitioner or a brief clinical intervention as a moderate level of support. We classified a clinical intervention in addition to a conventional case management as a high level of support.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Our primary outcome of interest was return to work, which was measured in studies using several descriptive outcomes. We included studies that reported at least one of the following.

Time to return to work.

Cumulative sickness absence.

Proportion at work at end of the follow‐up.

Proportion ever returned to work.

Since almost all of the included studies reported on the outcome 'proportion of participants who had ever returned to work', we added it post hoc. This outcome captures workers who returned to work (for a defined time span) during the follow‐up time, regardless of whether they stayed at work or took sick leave again.

We further considered whether the individual returned to:

full‐time or part‐time work; and

the former or a modified occupation.

Secondary outcomes

If included studies provided data on patient‐reported outcomes, we collected the following.

Physical, mental, social or overall functioning.

Pain, depression and anxiety.

Quality of life.

Satisfaction of patients, employers, and social insurance organisations.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We conducted a systematic literature search to identify published and unpublished trials that could be eligible for inclusion in this review. We developed a search strategy for PubMed and then adapted it for use in the other electronic databases (Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5). In order to avoid language bias, we used our international network to assess all non‐English language papers for potential inclusion in our review.

We searched the following electronic databases from their inception to 1 November 2016.

MEDLINE via PubMed (including the 'related citations' feature).

Embase.

CINAHL.

PsycINFO.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2016, Issue 11).

Searching other resources

We scanned the bibliographies of all eligible trials and other relevant publications, including reviews and meta‐analyses. For relevant publications that were listed in the Web of Science, we scanned citing articles with the 'times cited' feature.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Three authors (SS, NV, RK) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all identified citations and acquired full‐text articles that at least one author deemed potentially eligible. Subsequently, two authors (SS, NV) independently assessed the full‐text articles for eligibility; we resolved disagreements through discussion or by arbitration with a third author (RK). We identified and excluded duplicates and collated multiple reports of the same study so that each study rather than each report was the unit of interest. For details of excluded studies see Characteristics of excluded studies.

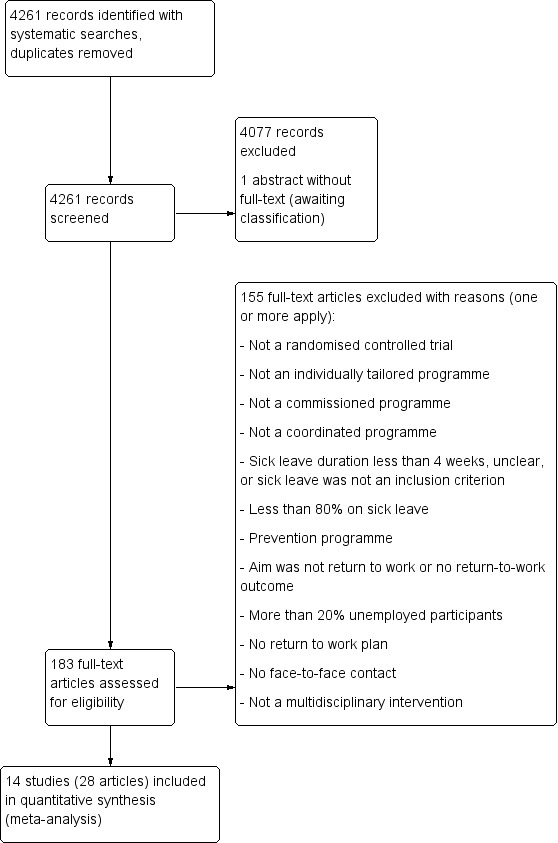

We recorded the selection process to complete a PRISMA flow diagram (Moher 2009). For details see Figure 1.

1.

PRISMA Study flow diagram

Data extraction and management

Using a standardised form, we extracted the following data.

Characteristics of study design.

Setting.

Participants.

Study eligibility criteria.

Intervention details.

Outcomes.

Funding sources and stated conflicts of interest.

Two pairs of authors (SS, JB, SE, NV) independently extracted data and resolved disagreement by discussion or by arbitration with a third author (RK). If information was insufficient or uncertain for data extraction, we contacted the study authors for clarification.

One author (NV) transferred data into the Cochrane statistical software, Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014); another author (TZ) cross‐checked the transferred data.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors (SS, NV) independently assessed all included studies for risk of bias using the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011). We referred to a third author (RK) to resolve disagreements. We evaluated the following risk of bias domains (Higgins 2011).

Sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding.

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective outcome reporting.

Other sources of bias.

We further assessed cluster‐RCTs for recruitment bias and appropriate statistical analysis (Higgins 2011).

We modified the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011): the response options of 'definitely yes' and 'probably yes' conferred low risk of bias, while the response options of 'definitely no' and 'probably no' conferred high risk of bias (Akl 2012). We graded each potential source of bias as high, low or unclear and provided a quote from the study report together with a justification for our judgment in the 'Risk of bias' table. We considered random sequence generation, allocation concealment, selective outcome reporting and incomplete outcome data to be key domains. We judged a study to be at high risk of bias when we judged one or more key domains to be at high risk of bias. Conversely, we judged a study to have a low risk of bias when we judged low risk of bias for all key domains. We summarised the risk of bias judgments across different studies for each of the domains listed.

We assessed blinding of outcome assessment and completeness of data for return‐to‐work outcomes and patient‐reported outcomes separately. We judged studies to be at high risk of attrition bias if they had more than 15% losses to follow‐up for return‐to‐work outcomes.

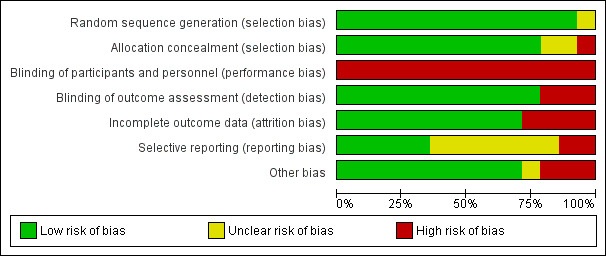

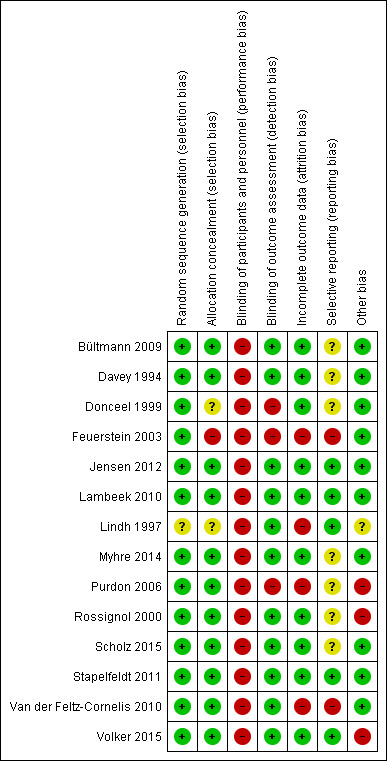

We summarised and presented the results of our risk of bias assessment in Figure 2 and Figure 3 as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Where information on risk of bias related to unpublished data or correspondence with the author, we noted this in the 'Risk of bias' tables.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review author's judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Assessment of bias in conducting the systematic review

We conducted the review according to our published protocol (Vogel 2015), reporting any deviations in the section Differences between protocol and review.

Measures of treatment effect

We entered outcome data for each study into the data tables in RevMan 2014 to calculate the treatment effects. We expressed dichotomous outcomes as risk ratios (RRs) and time‐to‐event outcomes as hazard ratios (HRs). We calculated absolute effects through risk differences (RDs). We recalculated sickness absence days in work days where necessary. For patient‐reported outcomes presented in different units, we transformed them into units on the scale of the most familiar instrument before pooling mean differences (MDs) (Thorlund 2011).

We used the minimal clinically important difference (MID) to improve the interpretation of patient‐reported outcomes (Johnston 2010). If studies reported only effect estimates and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) or standard errors, we entered these data into RevMan 2014 using the generic inverse variance method. If studies with time‐to‐event outcomes failed to report HRs, we extracted individual patient data from survival curves, verified the extracted data by comparing the original plot with the plot derived from the extracted data, and then calculated the HRs and associated 95% CIs.

We considered longer‐lasting return to work to be the most important outcome. If we detected varying measures of return to work, we concentrated on the one that expressed long‐term outcome best. If available, we focused on outcomes with at least four weeks of lasting return to work, even if a longer interval might be more meaningful.

Unit of analysis issues

In the case of cluster‐RCTs, we followed the methods in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). For studies that employed a cluster‐randomised design and that reported sufficient data to be included in the meta‐analysis but did not make an allowance for the design effect, we calculated the design effect based on a fairly large assumed intracluster correlation (ICC) of 0.10. We based this assumption of 0.10 being a realistic estimate by analogy on studies about implementation research (Campbell 2001).

Dealing with missing data

We contacted study authors to obtain data missing from their reports when necessary. If we could not obtain essential information within a reasonable time, we judged the respective risk of bias domain to be unclear. If we could not obtain numerical outcome data such as standard deviations (SD) or correlation coefficients, we calculated them from other available statistics such as P values according to the methods described in Higgins 2011. In case of missing values, we analysed the available data without imputations as a complete case analysis (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical homogeneity of the results of the included studied based on similarity of intervention, participants, outcome and follow‐up. We followed the algorithm provided by (Verbeek 2012). We considered participants as similar when they were of working age and on sick leave for at least four weeks. In the presence of statistical heterogeneity, we investigated differences between workers with musculoskeletal diseases and workers with mental health problems.

We considered interventions as similar when they were multidisciplinary return‐to‐work interventions tailored to the needs of the sick‐listed worker (as stated in Criteria for considering studies for this review). We considered outcome measures as similar when they reported on time to return to work, cumulative sickness absence, proportion of participants at work at a specific time point or proportion who had ever returned to work. We regarded short‐term (up to 6 months), long‐term (6 to 12 months) and very long‐term (longer than 12 months) follow‐up times as different.

We assessed heterogeneity by visual inspection of forest plots and by using the I² statistic. We then quantified the degree of heterogeneity as follows (Higgins 2011).

0% to 40% might not be important.

30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity.

50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity.

75% to 100% considerable heterogeneity.

In the presence of substantial heterogeneity and sufficient number of studies, we conducted subgroup analyses as described below (Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

Assessment of reporting biases

We tried to prevent reporting bias by searching across multiple databases and by including articles irrespective of their language. If we detected multiple articles on the same study, we extracted data only once. We assessed publication bias by funnel plots (Higgins 2011).

Data synthesis

We pooled data using the generic inverse variance method in RevMan 2014 according to Higgins 2011. If sufficient data were available, we performed a meta‐analysis. Since it is implausible that the true effect is the same in all considered studies, we considered a random‐effects model more appropriate for meta‐analyses. All our estimates include 95% CIs. For analyses not available within RevMan 2014, we used the R software (R 2015).

We expressed pooled effects of dichotomous outcomes as RRs and time‐to‐event outcomes as HRs. We calculated illustrative RDs by using the median baseline risk. We pooled effects of continuous outcomes as differences between group means (MDs). For patient‐reported outcomes, we calculated the proportion of patients who experienced an improvement greater than the MID ('substantial improvement') and pooled the RD (Thorlund 2011). If available, we used baseline‐adjusted effect estimates.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to conduct subgroup analyses to detect different effects if we found at least 10 studies in a meta‐analysis. We specified the following a priori hypotheses for possible subgroup differences.

Methodology: trials with high risk of bias show larger effects.

Intervention: effects increase with return‐to‐work coordination programmes starting earlier (within three months) in the course of sick leave.

Intervention: effects increase with the involvement of the employers.

Controls: effects decrease with the intensity of support for the control group (ranging from no support to other form of return‐to‐work coordination programmes).

We were unable to carry out subgroup analyses; no meta‐analyses included 10 or more studies.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed a sensitivity analysis to test the robustness of our results by omitting studies with a high risk of bias.

Reaching conclusions

We based our conclusions only on findings from the quantitative synthesis of included studies for this review. We considered the different return‐to‐work outcomes as measurements of the same concept and based our conclusion on all of them. We avoided making recommendations for practice based on more than just the evidence, such as values and available resources. Our implications for research suggest priorities for future research and outline the remaining uncertainties in the area.

Summary of findings table

We used the GRADE approach as described in Higgins 2011 and present the quality of the evidence in the Table 1.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We identified 14 relevant RCTs and included them in our meta‐analyses. Figure 1 illustrates the details of the search.

Included studies

Study design

All of the 14 included studies were RCTs with a parallel design. Three studies were cluster‐RCTs (Donceel 1999; Van der Feltz‐Cornelis 2010; Volker 2015). See Characteristics of included studies for further details.

Participants

We included 12,568 participants, 30% of whom were women. The range of participants per study was 50 to 8050 with a median of 220 participants. The mean age was 41.8 years. Eleven studies enrolled workers with musculoskeletal health problems, two enrolled workers with mental health problems (Van der Feltz‐Cornelis 2010; Volker 2015), and one study investigated both (Purdon 2006). Twelve studies included only employed participants, Davey 1994 included 96% employed participants, and Scholz 2015 included 93% employed participants. Workers in all studies were on sick leave: in seven studies they were on partial or full sick leave (Feuerstein 2003; Jensen 2012; Lambeek 2010; Myhre 2014; Scholz 2015; Stapelfeldt 2011; Volker 2015), while the rest of the studies included only workers on full sick leave. In five studies the length of work absence was shorter than three months (Bültmann 2009; Donceel 1999; Jensen 2012; Rossignol 2000; Stapelfeldt 2011); in four studies, longer than three months (Davey 1994; Lambeek 2010; Lindh 1997; Myhre 2014); in three studies, from 1 to 6 months (Feuerstein 2003; Purdon 2006; Volker 2015); and in one study, from 1 to 11 months (Van der Feltz‐Cornelis 2010). Scholz 2015 did not provide data, but the inclusion of participants with severe accidents made a sick leave duration of at least four weeks plausible. For further details see Characteristics of included studies.

Setting

Recruitment procedures took place from June 1995 to August 2011; this information was missing in four studies. Most of the studies took place in Europe, in: Belgium (Donceel 1999), Denmark (Bültmann 2009; Jensen 2012; Stapelfeldt 2011), the Netherlands (Lambeek 2010; Van der Feltz‐Cornelis 2010; Volker 2015), Norway (Myhre 2014), Sweden (Lindh 1997), Switzerland (Scholz 2015), and the UK (Davey 1994; Purdon 2006). Rossignol 2000 was in Canada, and Feuerstein 2003 was in the USA. For details of the recruitment procedures see Characteristics of included studies.

Experimental intervention

Although the return‐to‐work coordination programmes differed in structure, components, team members and duration, all included a tailored, multidisciplinary, coordinated intervention with an individual assessment and a return‐to‐work plan.

A variety of specialists were involved in the interventions, most often an occupational physician, a general practitioner or physician, a mental health specialist, a physical or occupational therapist, and a social worker. For further information see Table 2 and Characteristics of included studies. The duration of the return‐to‐work coordination programmes varied substantially. Some studies delivered the programme tailored to the worker's needs, others until successful return to work or for a defined period. Heterogeneous reporting precluded a descriptive summary (e.g. total number of weeks, median number of weeks, range of weeks). For details see Characteristics of included studies.

1. Involved disciplines in the intervention groups.

| Occupational or rehabilitation physician | General practitioner | (Occupational) physiotherapist | Psychologist, psychiatrist, psychotherapist | Occupational therapist | Social worker | Chiropractor | Other | |

| Bültmann 2009 | X | — | X | X | — | X | X | — |

| Davey 1994 | X | — | X | X | X | — | — | — |

| Donceel 1999 | X (social insurance physician) | X | — | — | — | — | — | Other healthcare personnel, social insurance agent |

| Feuerstein 2003 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | “[E].g. supervisor, injury compensation specialist, medical providers, claims examiner” |

| Jensen 2012 | X | X | X | — | X | X | — | — |

| Lambeek 2010 | X | — | X | — | X | — | — | Medical specialist |

| Lindh 1997 | X | — | X | X | X | X | — | Nurse, vocational counsellor |

| Myhre 2014 | X | — | X | — | — | — | — | Case worker, medical specialist, group discussions, lecturer |

| Purdon 2006 | — | — | X | X | — | — | X | Podiatrists, osteopaths and dieticians |

| Rossignol 2000 | X | — | X | — | — | — | X | — |

| Scholz 2015 | X (insurance physician) | X | X | — | X | — | — | Outpatient care provider, inpatient care provider, other care provider |

| Stapelfeldt 2011 | X | X | X | — | X | X | — | — |

| Van der Feltz‐Cornelis 2010 | X | X | — | X | — | — | — | — |

| Volker 2015 | X | X | — | X | — | — | — | Web‐based eHealth Modules |

X = involved discipline

The study coordinator contacted and enlisted the involvement of the employer in eight studies (Bültmann 2009; Feuerstein 2003; Jensen 2012; Lambeek 2010; Myhre 2014; Purdon 2006; Scholz 2015; Stapelfeldt 2011). One study reported no direct contact but described workplace accommodations as needed (Rossignol 2000). In five studies the employer was not involved in the intervention.

In five studies the intervention started less than three months after inclusion (Bültmann 2009; Donceel 1999; Jensen 2012; Rossignol 2000; Stapelfeldt 2011), while in four studies it started later than three months (Davey 1994; Lambeek 2010; Lindh 1997; Myhre 2014). In four studies the start of the intervention ranged from one to six months after inclusion, while the final study did not provide information.

Control intervention

We classified five studies as using a control intervention with a low level of support (Davey 1994; Donceel 1999; Lindh 1997; Purdon 2006; Rossignol 2000), while seven provided a moderate level of support (Bültmann 2009; Feuerstein 2003; Lambeek 2010; Myhre 2014; Scholz 2015; Van der Feltz‐Cornelis 2010; Volker 2015), and two studies offered a high level of support (Jensen 2012; Stapelfeldt 2011).

One study performed at two sites used the pre‐existing intervention at each site: either a brief or a comprehensive multidisciplinary intervention (Myhre 2014). However, authors showed similar effects for these treatment programmes.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

Nine studies retrieved the primary outcomes on return to work from administrative data (Bültmann 2009; Feuerstein 2003; Jensen 2012; Lindh 1997; Myhre 2014; Rossignol 2000; Scholz 2015; Stapelfeldt 2011; Volker 2015). Two studies used a combination of administrative data and self‐report (Lambeek 2010; Van der Feltz‐Cornelis 2010). Other studies used a semi‐structured interview in combination with information from claims files (Davey 1994), a standardised questionnaire (Donceel 1999), or a face‐to‐face survey (Purdon 2006).

Nine studies reported on time to return to work (Donceel 1999; Feuerstein 2003; Jensen 2012; Lambeek 2010; Myhre 2014; Rossignol 2000; Stapelfeldt 2011; Van der Feltz‐Cornelis 2010; Volker 2015), 7 studies reported on cumulative sickness absence (Bültmann 2009; Jensen 2012; Lambeek 2010; Myhre 2014; Scholz 2015; Stapelfeldt 2011; Volker 2015), 7 studies reported on the proportion of participants at work at end of the follow‐up (Bültmann 2009; Davey 1994; Donceel 1999; Jensen 2012; Lindh 1997; Purdon 2006; Van der Feltz‐Cornelis 2010), and 12 studies reported on the proportion of participants who had ever returned to work (Davey 1994; Donceel 1999; Feuerstein 2003; Jensen 2012; Lambeek 2010; Lindh 1997; Myhre 2014; Purdon 2006; Rossignol 2000; Stapelfeldt 2011; Van der Feltz‐Cornelis 2010; Volker 2015).

Definitions of return to work varied: eight studies used full‐time return to work (i.e. suspension of sickness benefits) (Donceel 1999; Feuerstein 2003; Jensen 2012; Lambeek 2010; Myhre 2014; Purdon 2006; Stapelfeldt 2011; Van der Feltz‐Cornelis 2010), and four studies applied full and partial return to work (Davey 1994; Lindh 1997; Rossignol 2000; Scholz 2015). Two studies reported data on full and partial return to work separately (Bültmann 2009; Volker 2015).

Six studies reported successful return to work without additional specification (Bültmann 2009; Davey 1994; Donceel 1999; Feuerstein 2003; Lindh 1997; Scholz 2015). Eight studies defined lasting return to work for at least two days (Rossignol 2000), two weeks (Purdon 2006), four weeks (Jensen 2012; Lambeek 2010; Stapelfeldt 2011; Van der Feltz‐Cornelis 2010; Volker 2015), or five weeks (Myhre 2014).

Secondary outcomes

Included studies also collected data on patient‐reported outcomes. We analysed secondary outcomes on pain (Bültmann 2009; Feuerstein 2003; Jensen 2012; Lambeek 2010; Myhre 2014; Purdon 2006; Rossignol 2000), overall function (Bültmann 2009; Jensen 2012; Lambeek 2010; Myhre 2014; Purdon 2006; Rossignol 2000), physical function (Feuerstein 2003; Jensen 2012; Lambeek 2010; Purdon 2006; Rossignol 2000), mental function (Feuerstein 2003; Jensen 2012; Purdon 2006), social function (Jensen 2012; Purdon 2006), depression (Davey 1994; Myhre 2014; Van der Feltz‐Cornelis 2010; Volker 2015), and anxiety (Davey 1994; Myhre 2014; Volker 2015).

We found insufficient data for meta‐analyses on quality of life and on the satisfaction of workers, employers or social insurance organisations.

Follow‐up

We regarded a follow‐up of up to 6 months as short‐term (Davey 1994; Rossignol 2000; Van der Feltz‐Cornelis 2010); between 6 and 12 months, as long‐term (Bültmann 2009; Donceel 1999; Lambeek 2010; Myhre 2014; Purdon 2006; Stapelfeldt 2011; Volker 2015); and more than 12 months, as very long‐term (Feuerstein 2003 (16 months); Jensen 2012 (24 months); Lindh 1997 (60 months); Scholz 2015 (72 months)). Duration of follow‐up times ranged from 3 to 72 months.

Excluded studies

We assessed 183 full text articles and excluded 155 for not meeting our inclusion criteria. See Characteristics of excluded studies for details.

Risk of bias in included studies

Risk of bias varied across studies (Figure 2). We judged 10 studies to be at low risk of bias (Bültmann 2009; Davey 1994; Donceel 1999; Jensen 2012; Lambeek 2010; Myhre 2014; Rossignol 2000; Scholz 2015; Stapelfeldt 2011; Volker 2015). We judged four studies to be at high risk of bias based on lack of allocation concealment (Feuerstein 2003), incomplete outcome data (Feuerstein 2003; Lindh 1997; Purdon 2006; Van der Feltz‐Cornelis 2010), and selective outcome reporting (Feuerstein 2003; Van der Feltz‐Cornelis 2010). See Figure 3 for details.

Allocation

Eleven studies reported concealed allocation and suitable methods of randomisation; we judged them to be at low risk of selection bias. Feuerstein 2003 omitted allocation concealment, so we judged the study to be at high risk of selection bias. Donceel 1999 and Lindh 1997 reported no concealment; we judged them to be at unclear risk of selection bias.

Blinding

We judged all studies to be at high risk of bias, acknowledging that successful blinding towards the intervention may be very challenging or not feasible at all. All but three studies succeeded in blinded outcome assessment by using administrative data on return to work (Donceel 1999;Feuerstein 2003;Purdon 2006) (see Types of outcome measures).

Incomplete outcome data

We found high risk of attrition bias for four studies (Feuerstein 2003; Lindh 1997; Purdon 2006; Van der Feltz‐Cornelis 2010).

Selective reporting

Two studies were at high risk of reporting bias. Feuerstein 2003 did not publish return‐to‐work outcomes but provided (incomplete) data on request. Van der Feltz‐Cornelis 2010 did not pre‐specify return to work as a primary outcome: it changed from 'level of functioning' in the protocol to 'time until return to work for at least four weeks'. They did not report the level of functioning.

Other potential sources of bias

We judged two studies to have a potential source of bias because of low adherence among participants (Purdon 2006; Volker 2015), while one study had baseline imbalances between the groups (Rossignol 2000).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Return‐to‐work coordination programmes versus usual practice

We compared return‐to‐work coordination programmes to usual practice. See Table 1 for the effects of the intervention for all outcomes and the GRADE assessment of quality of the evidence per outcome.

Primary outcomes

Time to return to work

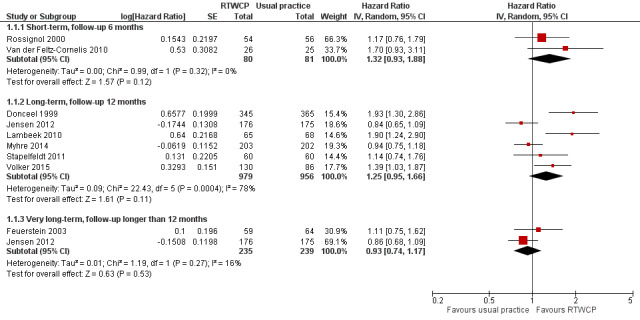

Based on nine studies, we found no significant differences in the Hazard Ratios (HR) of time to return to work (Analysis 1.1, Figure 4).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Return‐to‐work outcomes, Outcome 1 Time to return to work.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: time to return to work. RTWCP = return‐to‐work coordination programmes

The HR at short‐term follow‐up was 1.32 (95% CI 0.93 to 1.88, two studies, low quality evidence, low heterogeneity). The HR at long‐term follow‐up was 1.25 (95% CI 0.95 to 1.66, six studies, low quality evidence, substantial heterogeneity). The HR at very long‐term follow‐up was 0.93 (95% CI 0.74 to 1.17, two studies, low quality evidence, low heterogeneity).

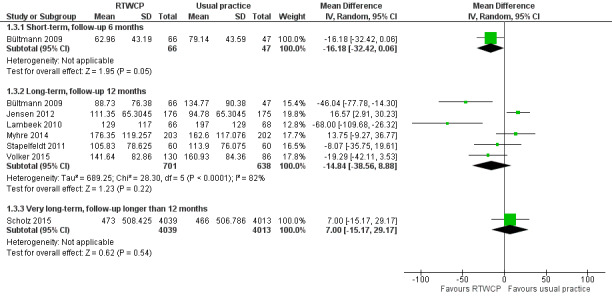

Cumulative sickness absence

Based on seven studies, we found no significant differences in cumulative sickness absence (Analysis 1.3, Figure 5).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Return‐to‐work outcomes, Outcome 3 Cumulative sickness absence in work days.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: cumulative sickness absence in work days. RTWCP = return‐to‐work coordination programmes

The Mean Difference (MD) at short‐term follow‐up was 16.18 work days per year lower (95% CI −32.42 to 0.06, one study, moderate quality evidence). The MD at long‐term follow‐up was 14.84 work days per year lower (95% CI −38.56 to 8.88, six studies, low quality evidence, substantial heterogeneity). The MD at very long‐term follow‐up was 7.00 work days per year higher (95% CI −15.17 to 29.17, one study, moderate quality evidence).

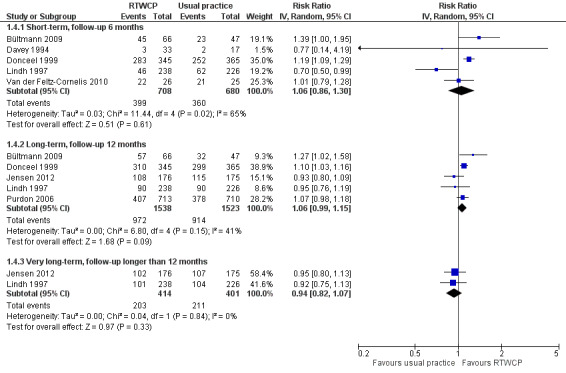

Proportion of participants at work at end of the follow‐up

Based on seven studies, we found no significant differences in the proportion of participants at work at end of the follow‐up (Analysis 1.4, Figure 6).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Return‐to‐work outcomes, Outcome 4 Proportion at work at end of the follow‐up.

6.

Forest plot of comparison: proportion at work at end of the follow‐up. RTWCP = return‐to‐work coordination programmes

The Risk Ratio (RR) at short‐term follow‐up was 1.06 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.30, five studies, low quality evidence, substantial heterogeneity). The RR at long‐term follow‐up was 1.06 (95% CI 0.99 to 1.15, five studies, low quality evidence, moderate heterogeneity). The RR at very long‐term follow‐up was 0.94 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.07, two studies, low quality evidence, low heterogeneity).

The absolute effect for the intervention versus control was 4 in 100 more individuals returning to work at short‐term follow‐up (95% CI 8 fewer to 16 more), 4 in 100 more at long‐term follow‐up (95% CI 2 fewer to 9 more), and 3 in 100 fewer at very long‐term follow‐up (95% CI 10 fewer to 3 more).

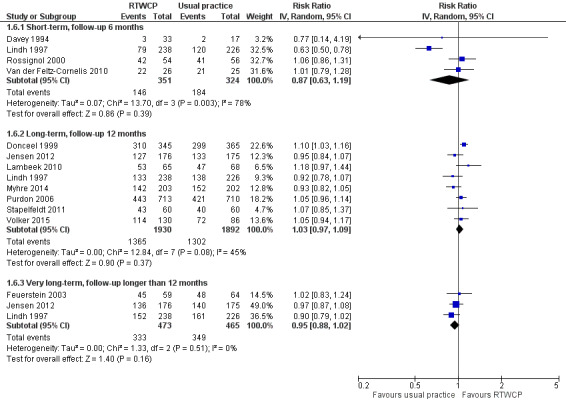

Proportion of participants who had ever returned to work

Based on 12 studies, we found no significant differences in the proportion of participants who had ever returned to work (Analysis 1.6, Figure 7).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Return‐to‐work outcomes, Outcome 6 Proportion who had ever returned to work.

7.

Forest plot of comparison: proportion who had ever returned to work. RTWCP = return‐to‐work coordination programmes

The RR at short‐term follow‐up was 0.87 (95% CI 0.63 to 1.19, four studies, very low quality evidence, substantial heterogeneity). The RR at long‐term follow‐up was 1.03 (95% CI 0.97 to 1.09, eight studies, moderate quality evidence, moderate heterogeneity). The RR at very long‐term follow‐up was 0.95 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.02, three studies, low quality evidence, low heterogeneity).

The absolute effect for the intervention versus control was 6 in 100 fewer individuals having ever returned to work for any time period at short‐term follow‐up (95% CI 19 fewer to 8 more), 2 in 100 more at long‐term follow‐up (95% CI 2 fewer to 6 more), and 4 in 100 fewer at very long‐term follow‐up (95% CI 10 fewer to 1 more).

Sensitivity analyses

For the primary outcomes, we conducted sensitivity analyses for studies at high risk of bias and cluster‐RCTs.

Omitting studies at high risk of bias revealed a significant difference in the proportion of participants working at end of the short‐term follow‐up (RR 1.20, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.30; Analysis 1.5). We found no significant changes for the time to return to work (Analysis 1.2), cumulative sickness absence (no high risk af bias studies), or the proportion of participants who had ever returned to work (Analysis 1.7)

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Return‐to‐work outcomes, Outcome 5 Proportion at work at end of the follow‐up, sensitivity analysis (low risk of bias studies only).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Return‐to‐work outcomes, Outcome 2 Time to return to work, sensitivity analysis (low risk of bias studies only).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Return‐to‐work outcomes, Outcome 7 Proportion who had ever returned to work, sensitivity analysis (low risk of bias studies only).

For cluster‐RCTs (Donceel 1999; Van der Feltz‐Cornelis 2010; Volker 2015), we calculated the design effect based on an ICC of 0.10. We found no relevant changes in the effect estimates or CIs.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In the presence of substantial heterogeneity, we wanted to conduct subgroup analyses according to our a priori hypotheses; however, we found too few studies in each subgroup to compare them in meaningful subgroup analyses.

Heterogeneity was substantial for time to return to work at long‐term follow‐up (I² = 78%; Analysis 1.1), cumulative sickness absence at a long‐term follow‐up (I² = 82%; Analysis 1.3), the proportion of participants at work at the end of short‐term follow‐up (I² = 65%; Analysis 1.4), and for the proportion who had ever returned to work at short‐term follow‐up (I² = 78%; Analysis 1.6).

Eliminating high risk of bias studies resolved heterogeneity for the proportion at work and the proportion who had ever returned to work. Eliminating two outliers, both clearly in favour for return‐to‐work coordination programmes (Donceel 1999; Lambeek 2010), reduced heterogeneity for time to return to work to a moderate level, even though these programmes showed no obvious differences to other studies. Heterogeneity for cumulative sickness absence at a long‐term follow‐up remained substantial and unexplained: even if we just analysed Jensen 2012 and Stapelfeldt 2011, two studies within the identical setting, identical recruitment procedure and identical interventions, heterogeneity remained moderate (I² = 59%).

Secondary outcomes

Pain

Seven studies reported on pain, and we found a significant MD and Risk Difference (RD) for long‐term follow‐up. However, the difference was not clinically important (Minimally Important Difference (MID) = −10.0 points on a 0 to 100 scale).

The MD at short‐term follow‐up was −4.76 points (95% CI −14.89 to 5.36, four studies, low quality evidence); at long‐term follow‐up, −2.98 points (95% CI −5.33 to −0.63, six studies, moderate quality evidence); and at very long‐term follow‐up, −7.20 points (95% CI −15.76 to 1.36, one study, very low quality evidence; Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Patient‐reported outcomes, Outcome 1 Pain ‐ scale 0 to 100 (higher score indicates improvement) ‐ MID 10.0.

The proportion of participants in the intervention group whose pain improved substantially was 3% (95% CI 0% to 6%) at long‐term follow‐up and not significantly different from control at short‐term (RD −3%, 95% CI −11% to 5%) or very long‐term follow‐up follow‐up (RD −2%, 95% CI −11% to 7%; Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Patient‐reported outcomes, Outcome 2 Pain ‐ pooled RDs of workers with an improvement greater than the MID of 10.0.

Overall function

Six studies reported on overall function, and we found a significant MD at short‐term follow‐up and no significant RDs. The effect did not reach the MID of 10 points on a 0 to 100 scale.

The MD at short‐term follow‐up was 8.13 points (95% CI 3.95 to 12.32, three studies, moderate quality evidence) and at long‐term follow‐up, 2.74 points (95% CI −0.15 to 5.64, five studies, moderate quality evidence; Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Patient‐reported outcomes, Outcome 3 Overall function ‐ scale 0 to 100 (higher score indicates improvement) ‐ MID 10.0.

The proportion of participants in the intervention group whose overall function improved substantially was not significantly different from control (RD 16%, 95% CI −4% to 37% and RD 0%, 95% CI −9% to 9%, respectively; Analysis 2.4).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Patient‐reported outcomes, Outcome 4 Overall function ‐ pooled RDs of workers with an improvement greater than the MID of 10.0.

Physical function

Five studies reported on physical function, but we found no significant MDs or RDs (MID = 8.4 points on a 0 to 100 scale).

The MD at short‐term follow‐up was 3.47 points (95% CI −3.26 to 10.20, three studies, low quality evidence); at long‐term follow‐up, 2.19 points (95% CI −2.29 to 6.67, four studies, very low quality evidence); and at very long‐term follow‐up, 1.85 points (95% CI −2.25 to 5.95, one study, very low quality evidence; Analysis 2.5).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Patient‐reported outcomes, Outcome 5 Physical function ‐ scale 0 to 100 (higher score indicates improvement) ‐ MID 8.4.

The proportion of participants in the intervention group whose physical function improved substantially was not significantly different from control (short‐term: RD 3%, 95% CI −7% to 13%; long‐term: RD 1%, 95% CI −2 to 3%; very long‐term: RD 0%, 95% CI −2% to 2%; Analysis 2.6).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Patient‐reported outcomes, Outcome 6 Physical function ‐ pooled RDs of workers with an improvement greater than the MID of 8.4.

Social function

Two studies reported on social function, and we found no significant MDs or RDs (MID = 11.7 points on a 0 to 100 scale).

The MD at long‐term follow‐up was 2.84 points (95% CI −0.09 to 5.77, two studies, low quality evidence; Analysis 2.7).

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Patient‐reported outcomes, Outcome 7 Social function ‐ scale to 0 to 100 (higher score indicates improvement) ‐ MID 11.7.

The proportion of participants in the intervention group whose social function improved substantially was not significantly different from control (RD 1%, 95% CI −2% to 4%; Analysis 2.8).

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Patient‐reported outcomes, Outcome 8 Social function ‐ pooled RDs of workers with an improvement greater than the MID of 11.7.

Mental function

Three studies reported on mental function. We found a significant MD at long‐term and very long‐term follow‐up and no significant RDs (MID = 7.3 points on a 0 to 100 scale).

The MD at short‐term follow‐up was 1.85 points (95% CI −2.67 to 6.37, one study, very low quality evidence); at long‐term follow‐up, 3.14 points (95% CI 1.16 to 5.11, three studies, moderate quality evidence); and at very long‐term follow‐up, 6.09 points (95% CI 0.56 to 11.63, one study, very low quality evidence; Analysis 2.9).

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Patient‐reported outcomes, Outcome 9 Mental function ‐ scale to 0 to 100 (higher score indicates improvement) ‐ MID 7.3.

The proportion of participants in the intervention group whose mental function improved substantially was not significantly different from control (short‐term: RD 0%, 95% CI −1% to 1%; long‐term: RD 0%, 95% CI −1% to 1%; and very long‐term: RD 0%, 95% CI −1% to 1%; Analysis 2.10).

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Patient‐reported outcomes, Outcome 10 Mental function ‐ pooled RDs of workers with an improvement greater than the MID of 7.3.

Depression

Four studies reported on depression, but we found no significant MDs or RDs (MID = 5.0 on a 0 to 27 scale).

The MD at short‐term follow‐up was 0.37 points (95% CI −2.81 to 3.55, three studies, low quality evidence) and for long‐term follow‐up, 0.00 points (95% CI −1.07 to 1.07, two studies, moderate quality evidence; Analysis 2.11).

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Patient‐reported outcomes, Outcome 11 Depression ‐ scale 0 to 27 (higher score indicates deterioration) ‐ MID 5.0.

The proportion of participants in the intervention group that experienced substantial change in depression was not significantly different from control (short term: RD 3%, 95% CI −7% to 12%; and long term: RD 1%, 95% CI −4% to 6%; Analysis 2.12).

2.12. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Patient‐reported outcomes, Outcome 12 Depression ‐ pooled RDs of workers with an improvement greater than the MID of 5.0.

Anxiety

Three studies reported on anxiety, but we found no significant MDs or RDs (MID = 4.0 on a 0 to 21 scale).

The MD at short‐term follow‐up was −0.02 points (95% CI −3.24 to 3.21, two studies, low quality, P = 0.99) and for long‐term follow‐up, 0.97 points (95% CI −0.17 to 2.12, two studies, moderate quality, P = 0.1; Analysis 2.13).

2.13. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Patient‐reported outcomes, Outcome 13 Anxiety ‐ scale 0 to 21 (higher score indicates deterioration) ‐ MID 4.0.

The proportion of participants in the intervention group that experienced substantial change in anxiety was not significantly different from control (short term: RD −1%, 95% CI −8% to 7 and long‐term: RD 2%, 95% CI −3% to 8%; Analysis 2.14).

2.14. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Patient‐reported outcomes, Outcome 14 Anxiety ‐ pooled RDs of workers with an improvement greater than the MID of 4.0.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We included 14 RCTs comparing return‐to‐work coordination programmes to usual practice. Very low‐ to moderate‐quality evidence suggests no benefits on return‐to‐work outcomes.

For the outcomes time to return to work, cumulative sickness absence, proportion of participants working at end of the follow‐up and proportion who had ever returned to work, we found no significant differences at short‐term (6 months), long‐term (12 months) or very long‐term (longer than 12 months) follow‐up.

Omitting high risk of bias studies showed a significantly higher proportion of participants returning to work at short‐term follow‐up but there were no relevant changes for any other outcome.

Regarding the patient‐reported outcomes, we found no differences greater than the MID. The quality of the evidence ranged from very low to moderate.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

We performed an extensive literature search without language restriction and screened almost 4000 records. Furthermore, the review authors contributed with their professional expertise in the field of work disability and insurance medicine to find ongoing or unpublished studies. Risk of selection bias is therefore low. However, we found only two studies in workers with common mental health problems.

We identified studies from nine different countries, reflecting a broad variety of healthcare systems. Differences in the healthcare systems and benefit schemes of each country might have an additional effect on the return‐to‐work outcome.

Quality of the evidence

We included 14 RCTs with more than 12,500 workers. We considered this a large number of participants.

The risk of bias was low in 10 studies and high in 4 studies because of reporting bias, attrition bias or detection bias. None of the studies blinded participants or personnel, but most studies retrieved return‐to‐work data through administrative databases (11 of 14).

According to the GRADE system, the quality of the evidence was very low to moderate through the different outcomes. Besides high risk of attrition or reporting bias, we downgraded the quality of evidence for inconsistency (substantial heterogeneity) and imprecision (a confidence interval spanning a negative and positive effect or a small population size).

Potential biases in the review process

At least two authors independently performed all subjective steps in the review process. We reported on individual studies, not articles, to prevent reporting bias, but we extracted data from all related articles. Funnel plots (not shown) did not suggest the presence of publication bias. If required, we recalculated sickness absence into work days to pool the MD or recalculated SDs from studies when only P values or standard errors were given. If studies reported no time‐to‐event outcomes, we extracted data from survival curves and verified it by comparing the original plot with the plot derived from the extracted data, and then calculated the HRs and associated 95% CIs.

Due to methodological considerations we included only RCTs and excluded non‐RCTs. We already knew we had an adequate number of RCTs because of our previous non‐Cochrane version of this review (Schandelmaier 2012). Furthermore, we decided to exclude studies without at least one face‐to‐face contact and employer‐initiated programmes, which were not our focus. However, we did not have to exclude studies solely for these reasons.

It is challenging to compare multidisciplinary programmes that allow for different interventions, in different intensities, with different support for the control group. However, we tried to choose appropriate inclusion and exclusion criteria. Unfortunately, we did not find enough data to explore further heterogeneity by means of subgroup analyses.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

In the previous version of this review (Schandelmaier 2012), we found significant effects for all four of the return‐to‐work outcomes in favour for return‐to‐work coordination programmes. Our new search identified five additional publications: all of them with low risk of bias, a follow‐up ranging from 12 months to 72 months, and moderate to high support for the control group. Thus, we conclude that the quality of research as well as the quality of usual practice has improved.

Other reviews on interventions facilitating return to work have different foci but partly overlap regarding the included studies. In summary, they give no clear recommendations regarding return‐to‐work coordination programmes.

Recently, Van Vilsteren 2015 investigated workplace interventions to prevent disability in workers on sick leave. Especially for workers with musculoskeletal disorders, they found evidence that workplace interventions reduce time to first return to work and cumulative duration of sickness absence. For time to lasting return to work, they found only low‐quality evidence for workplace interventions.

Nieuwenhuijsen 2014 analysed interventions to improve return to work in people with depression. Moderate‐quality evidence suggested that adding a work‐directed intervention to a clinical intervention reduced the number of days on sick leave compared to a clinical intervention alone. For adults with adjustment disorders, Arends 2012 found that cognitive behavioural therapy did not significantly reduce time to partial or full return to work compared with no treatment. For problem‐solving therapy, they found a significant effect on partial return to work after one year compared to non‐guideline based care, but there was no significant effect on time to full return to work.

Palmer 2012 completed a systematic review regarding the effectiveness of community‐ and workplace‐based interventions to reduce sickness absence and job loss. They concluded that most interventions, especially in large and high‐quality studies, show small beneficial effects. No intervention was clearly superior to another, but effort‐intensive interventions were less effective than simple programmes. Clayton 2011 reviewed studies with an individual focus to return people with disabilities and long‐term illnesses back to work. Personal advisors and individual case management helped some participants back to work, but authors concluded that existing programmes must be modified and extended for the more complex needs of those workers further from the labour market. Kuoppala 2008 found that return‐to‐work programmes decreased long sick leaves but not the proportion who returned to work. They emphasised the benefit of involving the workplace in rehabilitation efforts.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

This review found very low‐ to moderate‐quality evidence that return‐to‐work coordination programmes compared to usual practice do not facilitate return to work. We found no significant differences in our return‐to‐work outcomes at any follow‐up time point. Very low‐ to moderate‐quality evidence suggests no substantial impact on patient‐reported outcomes.

One fairly large, well‐designed study contributed data on more than 8000 participants over 72 months and provides moderate‐quality evidence suggesting no beneficial effect on cumulative sickness absence. On the other hand, we found two nearly identical studies (same setting and interventions, different participants): Stapelfeldt 2011 favoured return‐to‐work coordination programmes, and Jensen 2012 favoured usual practice, even if the results were not significant. These findings challenge the formulation of definitive implications for practice.

Implications for research.

Future studies should investigate lasting return to work for at least four weeks. A longer interval might be even more meaningful. It is not sufficient to report only whether return to work occurred or not; outcomes should capture relapse into sick leave as well.

More studies with a long‐term and very long‐term follow‐up will help to evaluate lasting benefits. A more detailed description of the intervention in both the control and the intervention group are necessary to distinguish the extent to which groups are different from one another. To improve the replicability of interventions, the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide ought to be used (Hoffmann 2014). Furthermore, monitoring additional healthcare utilisation would allow for better comparability.

There is a need for more studies on workers with mental health problems, as we already know that this will be a rising concern in the future (OECD 2014 b).

Furthermore, even if coordinated return‐to‐work programmes are not necessarily employer‐initiated, we believe it is essential to integrate the workplace as much as possible in the return‐to‐work process. Future studies should investigate and report more details on the extent and relevance of employers' involvement.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the authors providing us additional material and information and who patiently answered our questions. We are grateful to Gordon Guyatt for his indispensable support. Furthermore, we thank Mohsen Mousavi, who contributed to the protocol and helped to draft the review.

We thank Jani Ruotsalainen, Managing Editor, Cochrane Work Group for providing administrative and logistical support for the planning of the current review, and Kaisa Neuvonen, Trials Search Co‐ordinator, Cochrane Work Group, for developing and testing the search strategies.

We would also like to thank the Cochrane Work Group's Coordinating Editor Jos Verbeek, Managing Editor Jani Ruotsalainen, the Central Editorial Unit's Senior Editor Toby Lasserson, Editors Deirdre FitzGerald, Anneli Ojajärvi, and Kaisa Neuvonen; and external peer referees Juha Liira, David Bruinvels, Ute Bültmann and Doug Gross for their comments. Last but not least, we thank Joey Kwong for copy‐editing the protocol and Meggan Harris for copy editing the review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

1. "absenteeism"[tw]

2. "sick days"[tw]

3. "illness days"[tw]

4. "sick listed"[tw]

5. ("long term"[tw] OR "absence"[tw] OR "leave"[tw]) AND ("disability"[tw] OR "sickness"[tw] OR "sick"[tw])

6. ("benefit"[tw] OR "benefits"[tw] OR "pension"[tw] OR "pensions"[tw]) AND ("claimant"[tw] OR "claimants"[tw] OR "claim"[tw] OR "claims"[tw])

7. "work disablement"[tw]

8. "work disability"[tw]

9. "working disability"[tw]

10. "work absence"[tw]

11. ("injured"[tw] OR "injury"[tw] OR "accident"[tw] OR "sickness"[tw] OR "sick"[tw] OR "disability"[tw] OR "disabled"[tw] OR "disablement"[tw] OR "invalid"[tw] OR "invalidity"[tw] OR "absent"[tw] OR "absence"[tw]) AND ("worker"[tw] OR "workers"[tw] OR "employee"[tw] OR "employees"[tw])

12. ("sickness"[tw] OR "disability"[tw] OR "disabled"[tw] OR "disablement"[tw] OR "invalid"[tw] OR "invalidity"[tw] OR "absent"[tw] OR "absence"[tw] OR "out of work"[tw] OR "social security"[tw] OR "social insurance"[tw]) AND ("benefit"[tw] OR "benefits"[tw] OR "beneficiaries"[tw] OR "beneficiary"[tw] OR "claimant"[tw] OR "claimants"[tw] OR "claim"[tw] OR "claims"[tw] OR "pension"[tw] OR "pensions"[tw] OR "pensioners"[tw] OR "pensioner"[tw] OR "compensation"[tw] OR "compensations"[tw])

13. "Insurance, disability"[tw]

14. "disability insurance"[tw]

15. ("workman's"[tw] OR "workman"[tw] OR "workmans"[tw] OR "workmen's"[tw] OR "workmen"[tw] OR "workmens"[tw] OR "worker's"[tw] OR "worker"[tw] OR "workers"[tw]) AND ("compensation"[tw] OR "compensations"[tw])

16. "case management"[tw]

17. "case manager"[tw]

18. "absence management"[tw]

19. "assertive community treatment"[tw]

20. "management programme"[tw]

21. "management program"[tw]

22. ("project"[tw] OR "programme"[tw] OR "program"[tw] OR "model"[tw] OR "interview"[tw] OR "interviews"[tw] OR "plan"[tw] OR "measure"[tw] OR "measures"[tw] OR "intervention"[tw] OR "interventions"[tw] OR "rehabilitation"[tw] OR "management"[tw]) AND ("co ordinator"[tw] OR "coordinator"[tw] OR "coordination"[tw] OR "co ordination"[tw] OR "coordinated"[tw] OR "co ordinated"[tw] OR "multidisciplinary"[tw] OR "multi disciplinary"[tw] OR "multi professional"[tw] OR "multiprofessional"[tw] OR "multimodal"[tw] OR "multi modal"[tw] OR "integrated"[tw] OR "patient centred"[tw] OR "patient focused"[tw] OR "individual"[tw] OR "individually"[tw] OR "face to face"[tw] OR "one on one"[tw] OR "in person"[tw] OR "personal"[tw] OR "personally"[tw] OR "customized"[tw] OR "customised"[tw] OR "tailored"[tw] OR "on the job"[tw] OR "work focused"[tw] OR "work related"[tw] OR "workplace"[tw] OR "work location"[tw] OR "work‐site"[tw] OR "work place"[tw] OR "job site"[tw] OR "worksite"[tw] OR "occupational"[tw] OR "vocational"[tw] OR "return to work"[tw] OR "return to work" [mesh] OR "counselling"[tw] OR "reintegration"[tw])

23. "rehabilitation"[tw] AND ("project"[tw] OR "programme"[tw] OR "program"[tw] OR "plan"[tw] OR "model"[tw] OR "measure"[tw] OR "measures"[tw] OR "intervention"[tw] OR "interview"[tw] OR "interviews"[tw] OR "intervention"[tw] OR "interventions"[tw] OR "management"[tw])

24. "randomized controlled trial"[pt]

25. "controlled clinical trial"[pt]

26. "randomized"[tiab]

27. "randomised"[tiab]

28. "randomly"[tiab]

29. "trial"[ti]

30. "clinical trials as topic"[mesh: noexp]

31. OR / 1 ‐ 15

32. OR / 16 ‐ 23

33. OR / 24 ‐ 30

34. AND / 31 – 33

Appendix 2. EMBASE search strategy

(("absenteeism" OR "sick days" OR "illness days" OR "sick listed" OR (("long term" OR "absence" OR "leave" ) NEAR/3 ("disability" OR "sickness" OR "sick")) OR (("benefit" OR "benefits" OR "pension" OR "pensions") AND ("claimant" OR "claimants" OR "claim" OR "claims")) OR "work disablement" OR "work disability" OR "working disability" OR "work absence" OR (("injured" OR "injury" OR "accident" OR "sickness" OR "sick" OR "disability" OR "disabled" OR "disablement" OR "invalid" OR "invalidity" OR "absent" OR "absence") AND ("worker" OR "workers" OR "employee" OR "employees")) OR (("sickness" OR "disability" OR "disabled" OR "disablement" OR "invalid" OR "invalidity" OR "absent" OR "absence" OR "out of work" OR "social security" OR "social insurance") NEAR/3 ("benefit" OR "benefits" OR "beneficiaries" OR "beneficiary" OR "claimant" OR "claimants" OR "claim" OR "claims" OR "pension" OR "pensions" OR "pensioners" OR "pensioner" OR "compensation" OR "compensations")) OR "Insurance, disability" OR "disability insurance" OR (("workman?s" OR "workman" OR "workmans" OR "workmen?s" OR "workmen" OR "workmens" OR "worker?s" OR "worker" OR "workers") Near/3 ("compensation" OR "compensations"))) AND ("case management" OR "case anager" OR "absence management" OR "assertive community treatment" OR "management programme" OR "management program" OR (("project" OR "programme" OR "program" OR "model" OR "interview" OR "interviews" OR "plan" OR "measure" OR "measures" OR "intervention" OR "interventions" OR "rehabilitation" OR "management") NEAR/3 ("co ordinator" OR "coordinator" OR "coordination" OR "co ordination" OR "coordinated" OR "co ordinated" OR "multidisciplinary" OR "multi disciplinary" OR "multi professional" OR "multiprofessional" OR "multimodal" OR "multi modal" OR "integrated" OR "patient centred" OR "patient focused" OR "individual" OR "individually" OR "face to face" OR "one on one" OR "in person" OR "personal" OR "personally" OR "customized" OR "customised" OR "tailored" OR "on the job" OR "work focused" OR "work related" OR "workplace" OR "work location" OR "work‐site" OR "work place" OR "job site" OR "worksite" OR "occupational" OR "vocational" OR "return to work" OR "counselling" OR "reintegration")) OR (("project" OR "programme" OR "program" OR "plan" OR "model" OR "measure" OR "measures" OR "intervention" OR "interview" OR "interviews" OR "intervention" OR "interventions" OR "management") NEAR/3 "rehabilitation"))):ti:ab:de AND ([controlled clinical trial]/lim OR [randomized controlled trial]/lim OR "randomized":ti:ab OR "randomly":ti:ab OR "trial":ti OR "controlled clinical trial":de OR "single blind procedure":de OR "double blind procedure":de OR "triple blind procedure":de OR (doubl* next blind*):ti:ab OR (singl* next blind*):ti:ab OR (assign*):ti:ab OR (allocate*):ti:ab OR (volunteer*):ti:ab) AND [embase]/lim

Appendix 3. CINAHL search strategy