Abstract

The mammary gland contains adult stem cells that are capable of self-renewal. Although these cells hold an important role in the biology and pathology of the breast, the studies of mammary stem cells are few due to the difficulty of acquiring and expanding undifferentiated adult stem cell populations. In this study, we developed mammosphere cultures from frozen mammary cells of nulliparous cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis) as a culture system to enrich mammary stem cells. Small samples of mammary tissues were collected by surgical biopsy; cells were cultured in epithelial cell growth medium and cryopreserved. Cryopreserved cells were cultured into mammospheres, and the expression of markers for stemness was evaluated by using quantitative PCR analysis. Cells were further differentiated by using 2D and 3D approaches to evaluate morphology and organoid budding, respectively. The study showed that mammosphere culture resulted in an increase in the expression of mammary stem cell markers with each passage. In contrast, markers for epithelial cells and pluripotency decreased across multiple passages. The 2D differentiation of the cells showed heterogeneous morphology, whereas 3D differentiation allowed for organoid formation. The results indicate that mammospheres can be successfully developed from frozen mammary cells derived from breast tissue collected from nulliparous cynomolgus macaques through surgical biopsy. Because mammosphere cultures allow for the enrichment of a mammary stem cell population, this refined method provides a model for the in vitro or ex vivo study of mammary stem cells.

Abbreviations: MaSC, mammary stem cells; qRT-PCR, quantitative real-time RT–PCR

Multipotential stem cells, known as adult stem cells, are essential to the maintenance of most tissues in the body throughout life. These cells have the ability to undergo self-renewal to subsequently produce 2 stem cells or can divide in a fashion such that one cell remains a stem cell while the other daughter cell undergoes further differentiation.32 Although adult stem cells are typically present in small numbers within most tissues after gestational development, this condition is different with the mammary gland. Mammary gland development is unique because full differentiation of this organ is only attained at adulthood through pregnancy and lactation.17 Consistent with this fact, breast tissue from nulliparous women is known to contain large numbers of undifferentiated stem cells.15,33

Difficulty in obtaining mammary stem cells (MaSC) is due in large part to the small number of these cells typically found within the mammary gland, limited availability of markers for the characterization of MaSC, and few techniques to maintain the MaSC in an undifferentiated state.8 Currently, a technique known to enhance stem cells in culture is mammosphere culture.9 Mammosphere culture is an in vitro culture system which allows biologic cells to grow and proliferate freely with their surroundings in a 3D fashion and therefore is more similar in nature to the in vivo actions of these cells as compared with monolayer culture systems, which largely restrict growth to only 2 dimensions. Human and murine mammosphere cultures are highly enriched in undifferentiated cells including stem and early progenitor cells, as demonstrated by the ability of single cells isolated from mammospheres to generate multilineage colonies when cultured in the presence of serum on a collagen substratum that promotes their differentiation.8,9,33

Previous studies suggest MaSC are likely to be more abundant at specific life stages, such as during puberty or in early adulthood prior to first pregnancy (that is, nulliparity), when the breast is less differentiated.1,22 Therefore, choosing the right developmental stage is critical to ensure enough stem cells are present in the breast tissue to allow for isolation and enrichment of these cells. Because acquiring normal breast tissue during specific developmental stages is restricted by ethical constraints in humans, the use of NHP models for the study of MaSC is likely to be helpful in that biopsy collection from animals of essentially any age is possible. NHP have similarities with humans in genomics, anatomy, and physiology. Importantly, the mammary gland of cynomolgus macaques (M. fascicularis) has been demonstrated to have high similarity with human breast with regard to development, morphology, molecular profile, and carcinogenesis.4-6 The incidence of mammary hyperplastic and neoplastic diseases in M. fascicularis is comparable to those in humans, in whom the reported rate is 3% to 7%.3,39 We previously showed in a preliminary study that stem cells are likely present in primary cell cultures from M. fascicularis breast tissue, thus suggesting that these cultures may serve as an easily maintained and reliable source of MaSC for research.21 Here, such cell culture was used to develop mammospheres for enhancement of a stem cell population in vitro. We used a refined approach to collect small mammary tissue biopsies from adult nulliparous cynomolgus macaques and then cultured and cryopreserved the primary cells. Cryopreserved cells were developed into mammospheres, which were evaluated by using cell markers for stemness and by assessing the cells’ ability to differentiate along multiple lineages.

Materials and Methods

The study used adult nulliparous cynomolgus macaques (M. fascicularis; n = 3; age, 5 to 6 y) as the source of mammary gland tissues. All procedures involving animals were performed at Research Animal Facility–Lodaya of the Primate Research Center at Bogor Agricultural University, an AAALAC-accredited facility, after ethics approval from the IACUC of this facility. Animals were housed in semioutdoor setting with natural light cycle and fed a commercial laboratory primate chow (Charoen Pokphand, Bangkok, Thailand) with supplementation of fruits. Macaques were maintained in accordance with the institution's approved standard operating procedures, which are based on the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.12

Breast biopsy was conducted during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, as confirmed by vaginal cytology after daily observation to identify an animal's menstrual bleeding pattern. Biopsy was performed on deeply anesthetized animals (ketamine, 10 mg/kg; xylazine 0.5 mg/kg, IM) by using a method described previously.34 Under aseptic conditions, a 1.5- to 2-cm incision was made in the upper outer breast quadrant, and a small subcutaneous tissue sample was collected. The biopsy sample was wedge-shaped, approximately 2 cm × 1cm in size from nipple to the edge of the gland. Upon removal, the tissue was immediately placed in transport media. The incision was sutured, and postoperative care was provided according to IACUC-approved clinical procedures, including the use of analgesia (ketoprofen, 5 mg/kg, IM for 3 d).

Mammary tissue thus obtained comprised adipose and glandular tissues. Tissue digestion and cell dissociation was done mechanically and enzymatically according to a method previously described7,40 with slight modifications. Briefly, tissues collected in DMEM containing penicillin, streptomycin, and amphotericin B were dissociated mechanically and enzymatically with collagenase (1 mg/mL; Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO) at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 16 to 18 h. Cell suspensions were separated by centrifugation and plated at 100,000 cells/mL in selective medium for mammary epithelial cells (Lonza, Visp, Switzerland) and incubated in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Subculture was performed when the cell population reached 80% confluency, and viable cells from each passage were cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen (that is, frozen M. fascicularis mammary cells). The M. fascicularis mammary cells suspended in cryopreservation solution were immediately transferred to 1-mL cryovials, placed in a freezing container for 24 h at –80 °C, and transferred to liquid nitrogen for storage.

All in vitro mammosphere experiments were performed in duplicate. Frozen M. fascicularis mammary cells were thawed and seeded at 10,000 cells/mL in ultra-low attachment plates. Methods similar to those previously described7,40 were used for this process with 2 notable differences. The first modification to the previously published techniques was that a commercially available mammosphere media (Complete Human MammoCult Medium, Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) was used. The second modification was that mammosphere culture plates were sealed with paraffin tape for the first 3 d that the cells were in culture to promote sphere growth. Mammospheres that formed from the original cell plating (primary sphere) were collected and examined for subsequent formation of mammospheres. This was done through enzymatic and mechanical dissolution of the intact mammospheres and replating of the single cells acquired from this process at 10,000 cells/mL (that is, secondary and tertiary spheres). Mammospheres were collected weekly by centrifugation. For serial passaging, the total number of mammospheres obtained at each passage was counted microscopically; mammospheres were then enzymatically dissociated into large single cells and again seeded in low-attachment plates after counting of live cells. The mammosphere forming efficiency (MFE) was calculated according to the following equation:

MFE (%) = (no. of mammospheres per well) / (no. of cells seeded per well) × 100%.19

Cell differentiation was evaluated by using both 2D and 3D approaches. To induce 2D differentiation, mammospheres were cultured in 6-well tissue culture plates (10 to 12 spheres per well) with mammary epithelial cell growth medium (Lonza). Cells were incubated for 7 d and then trypsinized and prepared for mRNA extraction. The 3D differentiation was induced by culturing mammospheres in Matrigel (10 to 12 spheres in 25 μL Matrigel; Corning, Corning, NY). After 7 d of incubation, organoids were collected and prepared for mRNA extraction.

RNA was extracted from cells by using RNeasy kits (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and reverse-transcribed by using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quantitative real-time RT–PCR (qRT–PCR) analysis was used to measure expression of markers for MaSC (integrin β1 [CD29], integrin α6 [CD49f]), epithelial cells (cytokeratin 18, CD24), pluripotency (NANOG, OCT4, SOX2), and differentiation (casein β, STAT5). Sequences of primers used in this study are presented in Table 1. Reactions were performed by using SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (BioRad, Hercules, CA) on the Icycler iQ5 (BioRad). Thermocycler conditions were 2 min at 98 °C, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 5 s and annealing–elongation at the optimal primer annealing temperature (Table 1) for 10 s. GAPDH was used as the internal calibrator gene; relative expression was determined by using the δCt method.28

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for qRT-PCR

| Gene | Forward (5′–3′) | Reverse (5′–3′) | Annealing temperature (° C) | Reference |

| Cytokeratin 18 | ATC TTG GTG ATG CCT TGG AC | CCT GCT TCT GCT GGC TTA AT | 50 | 20 |

| CD24 | CCC ACG CAG ATT TAT TCC AG | GAC TTC CAG ACG CCA TTT G | 50 | 23 |

| Integrin β1 | GTT ACA CGG CTG CTG GTC TT | CTA CTG CTG ACT TAG GGA TC | 50 | 25 |

| Integrin α6 | CAA GAT GGC TAC CCA GAT AT | CTG AAT CTG AGA GGG AAC CA | 50 | 25 |

| NANOG | CCA GTC CCA AAG GCA AAC A | TCT TGA CCG GGA CCT TGT CT | 50 | This study |

| OCT4 | GAT GTG GTC CGA GTG TGG TTC T | GTT GTG CAT AGT CAC TGC TCG AT | 54 | This study |

| SOX2 | CTA GAA ACC CAT TTA TTC CCT GAC A | GAC AAC TCC TGA TAC TTT TTT GAA CAA | 50 | This study |

| Casein β | CTG CCT GGT GGC TCT TGC TCT T | TGG GGG ATA GGC AGG ACT TTG G | 61 | 24 |

| STAT5 | TGA GAT CCT GAA CAA CTG | CAA CAC TGA ACT GAG ACT | 51 | This study |

| GAPDH | CGG ATT TGG TCG TAT TGG | TCA AAG GTG GAG GAG TGG | 55 | 35 |

Data were analyzed by using JMP12 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Data were log-transformed where appropriate to improve data normality, back-transformed to original scale, and presented as means ± 1 SD. We performed ANOVA followed by multiple pairwise comparisons by using the Tukey Honestly Significant Difference test. For nonparametric data, analysis was performed by using the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by the Wilcoxon test for each pair.

Results

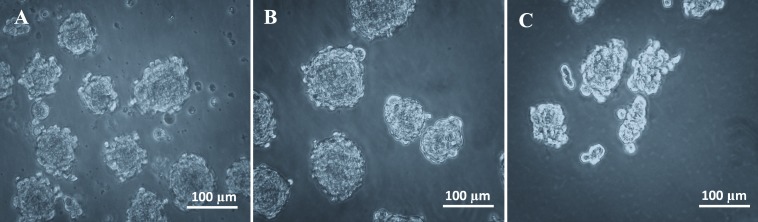

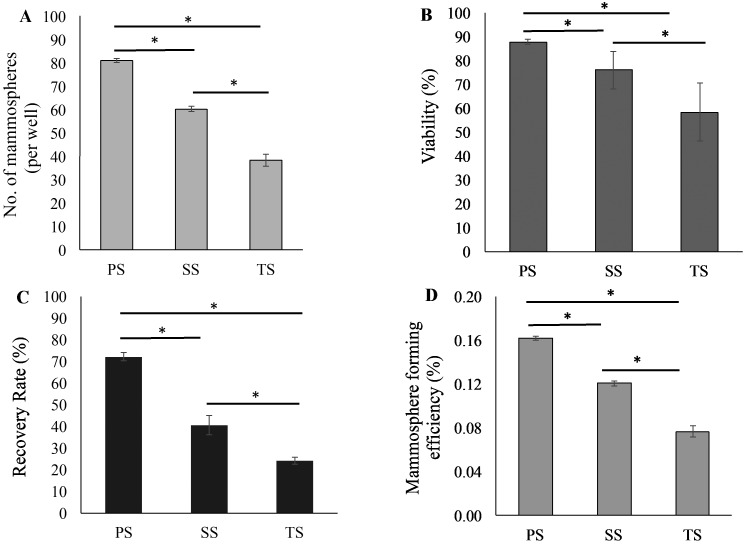

The biopsy tissues collected weighed 101, 115 and 122 mg, and each was successfully maintained as a primary cell culture, which then underwent cryopreservation. Cells derived from cryopreserved M. fascicularis mammary cells were able to survive and proliferate in ultra-low attachment surface plates and formed multicellular spheroids (that is, mammospheres; Figure 1). The spheres were round to oblong in morphology, and 40 to 100 µm in size. The primary spheres were successfully subcultured through at least 3 passages, after which tertiary-passage single cells were identified. The number of spheres decreased with each subsequent passage (Figure 2 A), as did viability (Figure 2 B), recovery rate (Figure 2 C), and mammosphere forming efficiency, which is the ability of single cells to form mammospheres (Figure 2 D).

Figure 1.

Morphology of M. fascicularis mammospheres. Mammospheres of M. fascicularis mammary cells (n = 3) were successfully subcultured to at least 3 passages. (A) Primary spheres. (B) Secondary spheres. (C) Tertiary spheres.

Figure 2.

M. fascicularis mammosphere (A) number, (B) viability, (C) recovery rate, and (D) mammosphere forming efficiency. All of these parameters decreased with each subsequent passage. Statistical differences between passages (P<0.05) are indicated with bar and different asterisk. Data are given as means ± 1 SD (error bars); *, P < 0.05. PS, primary spheres; SS, secondary spheres; TS, tertiary spheres.

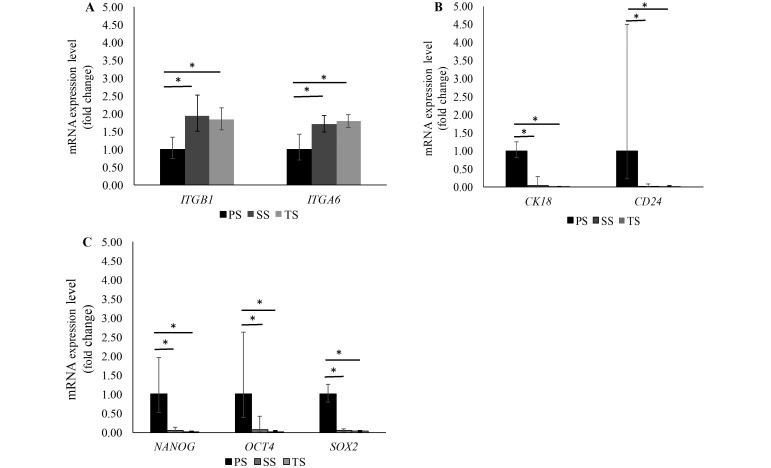

Importantly, the mRNA expression level of MaSC markers (integrin β1 and integrin α6) significantly (P < 0.05) increased in the mammospheres across each passage (Figure 3 A). In contrast, markers specific for differentiated mammary epithelial cells (that is, cytokeratin 18 and CD24) decreased (P < 0.01 for both markers) after each passage (Figure 3 B). The same pattern was found for markers of pluripotency, in that the expression of NANOG, SOX2, and OCT4 decreased (P < 0.001, P < 0.001, and P < 0.05, respectively) with subculture (Figure 3 C).

Figure 3.

Expression of markers for (A) mammary stem cells, (B) epithelial cells, and (C) pluripotency (in fold change, relative to PS). mRNA expression levels for integrin β1 (ITGB1; that is, CD29) and integrin α6 (ITGA6; that is, CD49f) increased with subsequent passages. In contrast, the expression of cytokeratin 18 (CK18), CD24, NANOG, OCT4, and SOX2 decreased with subsequent passages. Data are given as means ± 1 SD (error bars); *, P < 0.05. PS, primary spheres; SS, secondary spheres; TS, tertiary spheres.

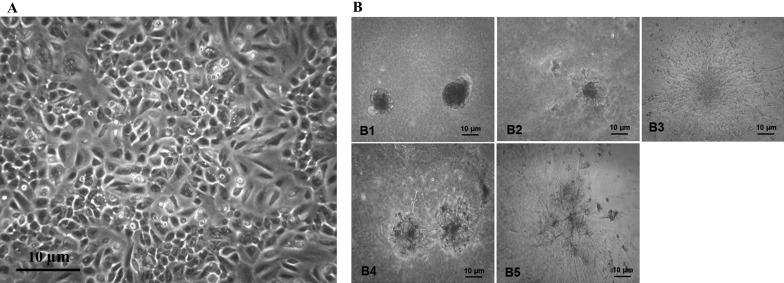

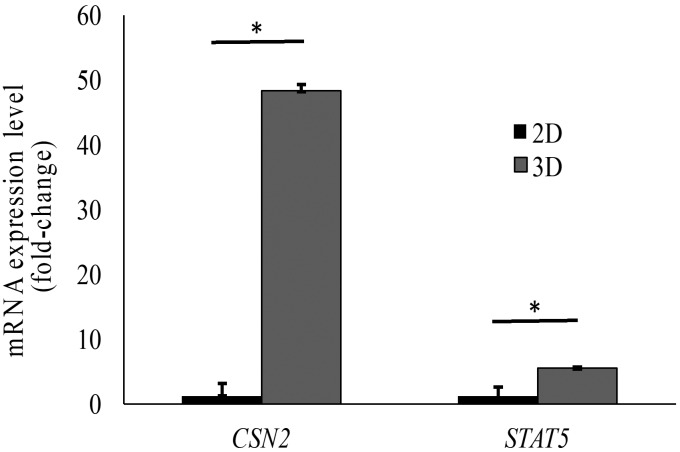

Cell differentiation under monolayer (that is, 2D) culture conditions produced cells with heterogeneous morphology, composed of epithelial-like and spindle-like cells (Figure 4 A). The 3D differentiation culture conditions produced organoid budding, categorized as coronal budding, subcoronal budding, and star-like budding, along with the formation of elongated ductal and alveolar-like structures (Figure 4 B). Differentiation markers casein β and STAT5 were detected in both 2D and 3D models, indicating that differentiated cells were present. The expression of these markers was higher (P < 0.05) in the 3D model (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Morphology of cells after (A) 2D and (B) 3D differentiation. Cells are heterogeneous with epithelial-like and spindle-like morphology after 2D differentiation. The morphology of organoids was categorized as nonbudding (B1), elongated duct structures (B2), coronal budding (B3), subcoronal budding (B4), and star-like budding (B5).

Figure 5.

Expression of differentiation markers (in fold change, relative to 2D). The mRNA expression (mean ± 1 SD [error bars]) of casein β (CSN2) and STAT5 in a 3D-differentiated culture was higher (*, P < 0.05) than in that with 2D differentiation.

Discussion

Adult MaSC hold an important role in the development of the mammary gland and are proposed to be cell-of-origin for some breast cancers.18,40 Given that changes in numbers or physiology of the stem cell populations in mammary glands may be critical to the understanding of breast carcinogenesis, there is a need for a reliable method to obtain adult MaSC populations for use in in vitro and ex vivo studies. Here, a 3D mammosphere culture system was created by using frozen primary mammary cells from the highly translational M. fascicularis model. Importantly, the cells used for these experiments were derived from small breast biopsy tissue samples, cultured as primary cells, and cryopreserved as cell stocks. This refined method is significant, because it allows for a minimally invasive and reliable approach to obtaining MaSC that can be used over long periods of time. The cells produced through these mammosphere cultures showed increases in expression levels of MaSC markers, indicative of enhancement of adult MaSC populations, and likewise were able to differentiate and form organoids.

The mammosphere culture assay is a well-established research tool. Mammospheres have been produced from the mammary gland cells of a wide variety of species,2,8,17 and these cultures have frequently been used to assess stem cell activity and self-renewal in breast cancer and normal mammary cells of both humans and mice.2,8,17 However, although mammosphere cultures have been derived from a large number of species, little is known regarding the validity of using NHP samples for the study of human breast cancer. In the only known NHP mammosphere publication to date, human- and murine-based mammosphere methods were used for the isolation of common marmoset and olive baboon stem and progenitor cells.40 Although important insights into the feasibility and utility of NHP mammosphere cultures were identified in this previous work,40 further biomedical exploration of mammospheres derived from other NHP species remains important. This need reflects the fact that some NHP species—macaques in particular—may be able to provide more insight into human breast carcinogenesis given the abundance of data regarding the mammary gland and breast cancer in these species. Specifically, macaque species have been demonstrated to have highly similar mammary morphology and tissue profiles to humans in the context of hormone receptors, gland development, and response to hormone and dietary treatments.4,5 Other research has found that some macaque species develop mammary gland tumors almost morphologically identical to those of humans; this same research has identified macaques to have similar prevalence rates of breast disease as humans when demographically comparable populations were evaluated.3,40 Mammosphere culture from macaques is therefore a valuable in vitro tool to study cancer risk and carcinogenesis, particularly under conditions that may be difficult to explore in humans, such as puberty and pregnancy. In light of the potential advantages of using macaques in research, we have undertaken studies using mammary gland cells collected from 2 of the most well-characterized macaque species. Ongoing mammosphere culture research on tissue from rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) tissues has resulted in optimized mammosphere culture and subculture conditions for necropsy-derived macaque mammary gland tissue.38 Furthermore, that work has validated the stem cell–like nature of the mammosphere-derived cells by using immunohistochemistry to identify differentiation of MaSC along various linages and by inducing lactation within the alveolar structures of budding spheres in vitro.38 The work described herein is the first description of validated mammosphere cultures derived from cynomolgus macaques. However, this research is perhaps most notable because this report is the first description of a nonterminal method for obtaining NHP mammospheres through the use of surgical biopsies, primary mammary cell cultures, and the cryopreservation of MaSC. Specifically, we showed that small surgical biopsies of breast tissue and cryopreservation of preliminary cultures can be used to maintain stocks of NHP MaSC for future mammosphere culture–related work. These developments thereby aid the breast cancer research community and simultaneously promote 3Rs implementation.11

Mammospheres are grown in suspension and are enriched in MaSC and progenitor cells, which are capable of self-renewal and multilineage differentiation. The sphere-initiating cells or their undifferentiated progeny then secrete proteins that contribute to the composition of mammospheres, as regulated by hormonal factors, extracellular matrix, and cell–cell interactions.9 In mouse models, the currently known cell-surface markers for isolating MaSC include CD24, integrin β1, and integrin α6, among others.1,31 The use of these markers has been a beneficial tool for isolating and enriching MaSC. In humans, integrin α6 is among the known markers for MaSC, although the expression of integrin α6 is also found in epithelial luminal progenitor cells.31 In the current study, mammosphere culture allowed for enrichment of M. fascicularis MaSC, as suggested by the increase in the expression of integrin β1 and integrin α6 with each passage.

Typically, first-generation cultures of human mammospheres contain 8 times the number of progenitor cells relative to human breast cell lines.8 The second- and third-generation mammospheres contain 100% bipotential progenitor cells, which can further form 3 lineages of the adult mammary gland: myoepithelial, ductal epithelial, and alveolar epithelial cells. Mammospheres are able to maintain stem cells and progenitors to retain self-renewal ability, which makes the system useful to study self-renewal and differentiation mechanisms.9

Our study showed that M. fascicularis mammospheres can survive as many as 3 passages, although the sphere numbers decreased with each subculture. Decrease in mammosphere formation may represent increased apoptosis, decreased proliferation of early progenitor cells or stem cells, or a reduction in stem cell self-renewal.30 In addition, the number of cells contained within each mammosphere may influence the mammosphere forming efficiency. Lack of sphere formation with each passage despite the presence of live and proliferating cells may be due to the tendency of the cells to differentiate toward the myoepithelial lineage with increasing passage.7 Manipulation of pathways that regulate the decision between self-renewal and differentiation may help in prolonging mammosphere lifespan in culture settings.7

The mammary gland ducts comprise an inner layer of luminal epithelial cells expressing cytokeratins, including cytokeratin 18, and an outer layer of myoepithelial–basal cells expressing additional cytokeratins and α-smooth muscle actin.15 In addition, cytokeratin 18 is an established marker typically used to delineate the degree of differentiation of mammary epithelial cells, because its presence indicates mature luminal epithelial cells.10 Another commonly used marker of epithelial cells is CD24 whereby the high and low expression levels of CD24 typically correspond to luminal epithelial and myoepithelial–basal cells, respectively.30 In our current study, M. fascicularis mammospheres were formed from a heterogeneous cell population which consisted of mammary epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and myoepithelial cells.21 The expression of both cytokeratin 18 and CD24 decreased with each passage, consistent with the idea that mammosphere culture enriches the stem cell population.

The mammary gland is composed of a ductal epithelial tree that comprises an inner layer of luminal cells and an outer layer of myoepithelial cells.26 The epithelium of the mammary gland is composed of 2 main cellular lineages: luminal cells that surround a central lumen and highly elongated myoepithelial cells that are located in a basal position adjacent to the basement membrane. Collectively, these cells are organized into a series of branching ducts that terminate in secretory alveoli during lactation.37 The cell populations derived from the M. fascicularis mammospheres in the current study were cultured as monolayers. Under these conditions, heterogeneous populations of epithelial-like and spindle-like cells were identified. Given their morphology, we propose that, under the monolayer culture conditions that we used, the mammosphere-derived stem cells underwent full differentiation into the mammary epithelial and myoepithelial cells that make up the bulk of the normal mammary gland structure.

Organoids can be expanded from embryonic cells, induced pluripotential stem cells, and from primary stem cells that have been isolated from organs. Notably, however, in vivo organs do not expand from single isolated stem cells, and therefore the mechanisms that drive the formation of stem cell organoids may be distinct from organogenesis in vivo.29 The organoid morphology can be used to define the necessary and sufficient components to replicate the structure and function of the mammary gland.29 In our study, the culture of M. fascicularis mammospheres in Matrigel resulted in organoid budding. Morphologically, these organoids contained diverse epithelial cell types that were organized into their normal spatial configurations, as observed in vivo.

Pluripotential cells are known to be present in disease-free breast tissue of parous and nulliparous women, and these cells are known to have remarkable lineage plasticity.27,36 Cells expressing the pluripotency markers OCT4, NANOG, and SOX2 are present in breast milk, supporting the notion that pluripotential cells are present in the normal breast.13,14 We have previously shown that OCT4, NANOG, and SOX2 were expressed in primary mammary cells of cynomolgus macaques.21 In the current study, the expression levels of these markers in mammosphere culture decreased with each passage, suggesting that mammosphere culture enriches multipotential cells but not pluripotential cells.

Our results show that mammospheres can be reliably obtained from cryopreserved M. fascicularis mammary gland cell cultures initially derived from small biopsies of mammary gland tissue; mammosphere culture enriches previously cryopreserved M. fascicularis mammary gland cell cultures for MaSC populations; and the M. fascicularis MaSC have the capability to further differentiate along multiple lineages when grown in mammary epithelial cell growth medium or Matrigel. In short, the M. fascicularis mammosphere model is likely to be highly useful for a variety of future studies addressing stem cell differentiation or breast carcinogenesis. Further studies are planned to better characterize and advance this cell culture model, including the use of chemical and radiation exposure to induce carcinogenesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Silvia Prabandari, MSi, for support regarding vaginal cytology evaluation; Ricky Fong for primer design; and the staffs of the Research Animal Facility at Lodaya, the Microbiology and Immunology Laboratory, and the Biotechnology Laboratory of the Primate Research Center at Bogor Agricultural University for their technical contributions. This study was financially supported by the Ministry of Research and Technology and Higher Education of the Republic of Indonesia.

References

- 1.Chen X, Liu Q, Song E. 2017. Mammary stem cells: angels or demons in mammary gland? Signal Transduct Target Ther 2:1–8. 10.1038/sigtrans.2016.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cioce M, Gherardi S, Viglietto G, Strano S, Blandino G, Muti P, Ciliberto G. 2010. Mammosphere-forming cells from breast cancer cell lines as a tool for the identification of CSC-like- and early progenitor-targeting drugs. Cell Cycle 9:2950–2959. 10.4161/cc.9.14.12371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cline JM. 2007. Assessing the mammary gland of nonhuman primates : effects of endogenous hormones and exogenous hormonal agents and growth factors. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol 80:126–146. 10.1002/bdrb.20112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cline JM, Wood CE. 2008. The mammary glands of macaques. Toxicol Pathol 36:134S–141S. 10.1177/0192623308327411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dewi FN, Wood CE, Lees CJ, Willson CJ, Register TC, Tooze JA, Franke AA, Cline JM. 2013. Dietary soy effects on mammary gland development during the pubertal transition in nonhuman primates. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 6:832–842. 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-13-0128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dewi FN, Wood CE, Willson CJ, Register TC, Lees CJ, Howard TD, Huang Z, Murphy SK, Tooze JA, Chou JW, Miller LD, Cline JM. 2016. Effects of pubertal exposure to dietary soy on estrogen receptor activity in the breast of cynomolgus macaques. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 9:385–395. 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-15-0165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dey D, Saxena M, Paranjape AN, Krishnan V, Giraddi R, Kumar MV, Mukherjee G, Rangarajan A. 2009. Phenotypic and Functional Characterization of Human Mammary Stem/Progenitor Cells in Long Term Culture. PLoS One 4:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dontu G, Abdallah WM, Foley JM, Jackson KW, Clarke MF, Kawamura MJ, Wicha MS. 2003. In vitro propagation and transcriptional profiling of human mammary stem / progenitor cells. Genes Dev 17:1253–1270. 10.1101/gad.1061803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dontu G, Al-Hajj M, Abdallah WM, Clarke MF, Wicha MS. 2003. Stem cells in normal breast development and breast cancer. Cell Prolif 36 Suppl 1:59–72. 10.1046/j.1365-2184.36.s.1.6.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eirew P, Stingl J, Raouf A, Turashvili G, Aparicio S, Emerman JT, Eaves CJ. 2008. A method for quantifying normal human mammary epithelial stem cells with in vivo regenerative ability. Nat Med 14:1384–1389. 10.1038/nm.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fenwick N, Griffin G, Gauthier C. 2009. The welfare of animals used in science: How the “Three Rs” ethic guides improvements. Can Vet J 50:523–530. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Institute for Laboratory Animal Research. 2011. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, 8th ed. Washington (DC): National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hassiotou F, Beltran A, Chetwynd E, Stuebe AM, Twigger AJ, Metzger P, Trengove N, Lai CL, Filgueira L, Blancafort P, Hartmann PE. 2012. Breastmilk is a novel source of stem cells with multilineage differentiation potential. Stem Cells 30:2164–2174. 10.1002/stem.1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hassiotou F, Hartmann PE. 2014. At the dawn of a new discovery: the potential of breast milk stem cells. Adv Nutr 5:770–778. 10.3945/an.114.006924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joshi PA, Di Grappa MA, Khokha R. 2012. Active allies: hormones, stem cells and the niche in adult mammopoiesis. Trends Endocrinol Metab 23:299–309. 10.1016/j.tem.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LaMarca HL, Rosen JM. 2008. Minireview: hormones and mammary cell fate—what will I become when I grow up? Endocrinology 149:4317–4321. 10.1210/en.2008-0450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liao MJ, Cheng CC, Zhou B, Zimonjic DB, Mani SA, Kaba M, Gifford A, Reinhardt F, Popescu NC, Guo W, Eaton EN, Lodish HF, Weinberg RA. 2007. Enrichment of a population of mammary gland cells that form mammospheres and have in vivo repopulating activity. Cancer Res 67:8131–8138. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu S, Dontu G, Wicha MS. 2005. Mammary stem cells, self-renewal pathways, and carcinogenesis. Breast Cancer Res 7:86–95. 10.1186/bcr1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lombardo Y, de Giorgio A, Coombes CR, Stebbing J, Castellano L. 2015. Mammosphere formation assay from human breast cancer tissues and cell lines. J Vis Exp 2015:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Makino T, Yamasaki M, Takeno A, Shirakawa M, Miyata H, Takiguchi S, Nakajima K, Fujiwara Y, Nishida T, Matsuura N, Mori M, Doki Y. 2009. Cytokeratins 18 and 8 are poor prognostic markers in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus. Br J Cancer 101:1298–1306. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mariya S, Dewi FNA, Suparto IH, Wilkerson GK, Cline JM. 2017. Mammary gland cell culture of Macaca fascicularis as a reservoir for stem cells. Hayati 24:136–141. 10.1016/j.hjb.2017.09.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meier-Abt F, Milani E, Roloff T, Brinkhaus H, Duss S, Meyer DS, Klebba I, Balwierz PJ, van Nimwegen E, Bentires-Alj M. 2013. Parity induces differentiation and reduces Wnt/Notch signaling ratio and proliferation potential of basal stem/progenitor cells isolated from mouse mammary epithelium. Breast Cancer Res 15:1–17. 10.1186/bcr3419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Modur V, Joshi P, Nie D, Robbins KT, Khan AU, Rao K. 2016. CD24 expression may play a role as a predictive indicator and a modulator of cisplatin treatment response in head and neck squamous cellular carcinoma. PLoS One 11:1–21. 10.1371/journal.pone.0156651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oakes SR, Rogers RL, Naylor MJ, Ormandy CJ. 2008. Prolactin regulation of mammary gland development. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 13:13–28. 10.1007/s10911-008-9069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qiu L, Low HP, Chang CI, Strohsnitter WC, Anderson M, Edmiston K, Adami HO, Ekbom A, Hall P, Lagiou P, Trichopoulos D, Hsieh CC. 2011. Novel measurements of mammary stem cells in human umbilical cord blood as prospective predictors of breast cancer susceptibility in later life. Ann Oncol 23:245–250. 10.1093/annonc/mdr153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rios AC, Fu NY, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE. 2014. In situ identification of bipotent stem cells in the mammary gland. Nature 506:322–327. 10.1038/nature12948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roy S, Gascard P, Dumont N, Zhao J, Pan D, Petrie S, Margeta M, Tlsty TD. 2013. Rare somatic cells from human breast tissue exhibit extensive lineage plasticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:4598–4603. 10.1073/pnas.1218682110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. 2008. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat Protoc 3: 1101–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shamir ER, Ewald AJ. 2014. Three-dimensional organotypic culture: experimental models of mammalian biology and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15:647–664. 10.1038/nrm3873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaw FL, Harrison H, Spence K, Ablett MP, Simoes BM, Farnie G, Clarke RB. 2012. A detailed mammosphere assay protocol for the quantification of breast stem cell activity. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 17:111–117. 10.1007/s10911-012-9255-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sleeman KE, Kendrick H, Robertson D, Isacke CM, Ashworth A, Smalley MJ. 2007. Dissociation of estrogen receptor expression and in vivo stem cell activity in the mammary gland. J Cell Biol 176:19–26. 10.1083/jcb.200604065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sobhani A, Khanlarkhani N, Baazm M, Mohammadzadeh F, Najafi A, Mehdinejadiani S, Sargolzaei Aval FS. 2017. Multipotent stem cell and current application. Acta Med Iran 55:6–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stingl J, Eirew P, Ricketson I, Shackleton M, Vaillant F, Choi D, Li HI, Eaves CJ. 2006. Purification and unique properties of mammary epithelial stem cells. Nature 439:993–997. 10.1038/nature04496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stute P, Sielker S, Wood CE, Register TC, Lees CJ, Dewi FN, Williams JK, Wagner JD, Stefenelli U, Cline JM. 2011. Life stage differences in mammary gland gene expression profile in non-human primates. Breast Cancer Res Treat 133:617–634. 10.1007/s10549-011-1811-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tian H, Bharadwaj S, Liu Y, Ma H, Ma PX, Atala A, Zhang Y. 2010. Myogenic differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells on a 3D nano fibrous scaffold for bladder tissue engineering. Biomaterials 31:870–877. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Visvader JE. 2009. Keeping abreast of the mammary epithelial hierarchy and breast tumorigenesis. Genes Dev 23:2563–2577. 10.1101/gad.1849509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Visvader JE, Stingl J. 2014. Mammary stem cells and the differentiation hierarchy : current status and perspectives. Genes Dev 28:1143–1158. 10.1101/gad.242511.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilkerson GK. [Internet]. 2016. Development and utilization of a macaque-based mammosphere culture technique for breast cancer research. [Cited 31 January 2019]. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10217/178824.

- 39.Wood CE, Usborne AL, Starost MF, Tarara RP, Hill RL, Wilkinson M, Geisinger KR, Feiste EA, Cline JM.2006. Hyperplastic and neoplastic lesions of the mammary gland in macaques. Vet Pathol 43:471–483. 10.1354/vp.43-4-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu A, Dong Q, Gao H, Shi Y, Chen Y, Zhang F, Bandyopadhyay A, Wang D, Gorena KM, Huang C, Tardif S, Nathanielsz PW, Sun LZ. 2016. Characterization of mammary epithelial stem/progenitor cells and their changes with aging in common marmosets. Sci Rep 6:1–15. 10.1038/srep32190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]