Abstract

Background

The most common psychiatric diagnosis among cancer patients is depression; this diagnosis is even more common among patients with advanced cancer. Psychotherapy is a patient‐preferred and promising strategy for treating depression among cancer patients. Several systematic reviews have investigated the effectiveness of psychological treatment for depression among cancer patients. However, the findings are conflicting, and no review has focused on depression among patients with incurable cancer.

Objectives

To investigate the effects of psychotherapy for treating depression among patients with advanced cancer by conducting a systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Group Register, The Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO databases in September 2005.

Selection criteria

All relevant RCTs comparing any kind of psychotherapy with conventional treatment for adult patients with advanced cancer were eligible for inclusion. Two independent review authors identified relevant studies.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data from the original reports using standardized data extraction forms. Two independent review authors also assessed the methodological quality of the selected studies according to the recommendations of a previous systematic review of psychological therapies for cancer patients that utilized ten internal validity indicators. The primary outcome was the standardized mean difference (SMD) of change between the baseline and immediate post‐treatment scores.

Main results

We identified a total of ten RCTs (total of 780 participants); data from six studies were used for meta‐analyses (292 patients in the psychotherapy arm and 225 patients in the control arm). Among these six studies, four studies used supportive psychotherapy, one adopted cognitive behavioural therapy, and one adopted problem‐solving therapy. When compared with treatment as usual, psychotherapy was associated with a significant decrease in depression score (SMD = ‐0.44, 95% confidence interval [CI] = ‐0.08 to ‐0.80). None of the studies focused on patients with clinically diagnosed depression.

Authors' conclusions

Evidence from RCTs of moderate quality suggest that psychotherapy is useful for treating depressive states in advanced cancer patients. However, no evidence supports the effectiveness of psychotherapy for patients with clinically diagnosed depression.

Keywords: Humans, Psychotherapy, Depression, Depression/etiology, Depression/therapy, Depressive Disorder, Depressive Disorder/etiology, Depressive Disorder/therapy, Neoplasms, Neoplasms/psychology, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Psychotherapy for depression among cancer patients who are incurable

Depressive states represent frequent complications among cancer patients and are more common amongst advanced cancer patients. Psychotherapy comprises of various interventions for ameliorating or preventing psychological distress conducted by direct verbal or interactive communication, or both, and is delivered by health care professionals. It is a patient‐preferred and promising strategy for treating depressive states among cancer patients. Several systematic reviews have investigated the effectiveness of psychotherapy for treating depressive states among cancer patients. However, the findings are conflicting, and no review has focused on depressive states among patients with incurable cancer. The review authors conducted a systematic review of randomised controlled trials to investigate the effects of psychotherapy on the treatment of depressive states among patients with advanced cancer. The review authors found that psychotherapy was useful for treating depressive states in advanced cancer patients. However, little evidence supports the effectiveness of psychotherapy for patients with clinically diagnosed depression including major depressive disorder. Future studies to investigate and clarify the usefulness of psychotherapy for treating clinically diagnosed depression in terminally ill patients are needed.

Background

Cancer is a life‐threatening disease that often impacts on a patient's welfare and well‐being; attention to these issues is thus an important aspect of comprehensive patient care. Derogatis et al. found that 50% of cancer patients are diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder. The most common psychiatric diagnosis was depressive disorders, including adjustment disorder with depressed mood (12%) or mixed emotional features (13%) or unipolar major depression, (4%) or both (Derogatis 1983). Other studies have consistently indicated that these depressive disorders represent common forms of psychological distress experienced by cancer patients (Akechi 2001; Kugaya 2000; Okamura 2000) and are more common in patients with advanced cancer (Bukberg 1984; Kugaya 2000). Thus depression is one of the most widely recognized psychiatric disorders in cancer patients (McDaniel 1995). Depression not only produces serious suffering (Block 2000), but also worsens quality of life (Grassi 1996), reduces compliance with anti‐cancer treatment (Colleoni 2000), can lead to suicide (Henriksson 1995), is a psychological burden on the family (Cassileth 1985), and prolongs hospitalization (Prieto 2002). Thus, the appropriate management of depression in cancer patients is critically important.

One patient‐preferred and promising strategy for treating depression among cancer patients is psychotherapy (Okuyama 2007). Here, the term 'psychotherapy' is defined as various kinds of interventions for ameliorating or preventing psychological distress conducted by direct verbal or interactive communication, or both, delivered by health care professionals. Several meta‐analyses and systematic reviews investigating the effectiveness of psychosocial treatment for depression among cancer patients have been performed. However, the findings of these reports are conflicting (Devine 1995; Newell 2002; Ross 2002; Sheard 1999), and no review to date has addressed the effectiveness of psychotherapy for treating depression among incurable cancer patients.

Objectives

The primary objective of this review was to investigate the effectiveness of psychotherapy for treating any kind of depression in incurable cancer patients.

The review also evaluated the effectiveness of psychotherapy on:

anxiety,

general psychological distress,

control of cancer symptoms,

quality of life,

coping measures for patients,

severity of physical symptoms such as pain.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing any kind of psychotherapy with conventional treatment (treatment as usual).

Types of participants

The study participants were limited to adults (18 years or older) of either sex with any primary diagnosis of incurable cancer. Their depression had to be assessed by validated measures, such as standardized self‐report questionnaires or clinical interviews (e.g., Structured Clinical Interview for major depressive episode based on DSM‐IV). A concurrent diagnosis of another physical disease was not a criteria for exclusion.

Types of interventions

Studies involving psychotherapy of any kind were included in the review. We were interested in the effect of a broad range of psychological interventions, including several unique interventions, such as music therapy, that may be used in a palliative care setting. On the other hand, interventions that were not considered as forms of psychotherapy (e.g., aromatherapy, therapeutic touch) were not included. This broad range of non‐pharmacological interventions were further divided into: A: interventions by direct verbal or interactive communication, or both, delivered by health care professionals; and B: non‐pharmacological interventions other than the aforementioned ones.

Types of outcome measures

Tolerability of the treatment was to be evaluated using the following outcome measures: 1) Number of patients dropping out of the study for any reason.

Primary outcomes

The studies had to include at least one measure of the severity of depression, which was set as the primary outcome of this systematic review. Symptom severity could be measured either by self‐reporting or rating by an observer.

Effectiveness was to be evaluated using the group mean scores of these continuous depression severity scales (this planned analytical method was modified in the completed review (See 'Results')).

Outcomes were to be measured at the end of the study. Where possible, these indices of effectiveness would be pooled at different time points in the course of treatment, such as at one month, three months, six months and so on. In addition, when studies provided data regarding ongoing effectiveness after treatment termination, this data was also to be pooled (this planned method was modified (See 'data synthesis').

Secondary outcomes

No of patients who 'responded' to treatment according to the original study authors' definition.

Anxiety, as measured using scales like the Hamilton Anxiety Rating scale, the State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

General psychological distress, as measured using scales like the Profile of Mood States (total mood disturbance) and the General Health Questionnaire.

Quality of life, as measured using scales like the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) quality of life questionnaire, the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy‐General (FACT‐G) scale, and the Medical Outcome Study Short‐Form 36‐item survey.

Severity of physical symptoms like pain, as measured using scales like the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) and visual analogue scale (VAS).

Search methods for identification of studies

1. Electronic databases

To identify studies for inclusion in this review, detailed search strategies were developed for each electronic database searched in September 2005. These strategies were based on the search strategy developed for MEDLINE (Appendix 1) but were revised appropriately for each database and are included in additional Appendix 2.

2. Reference search

The references of all selected studies were inspected for more published reports and citations of unpublished studies. In addition, other relevant review papers were checked.

3. SciSearch

All the selected studies were sought as a citation in the SciSearch database to identify additional studies.

4. Personal communication

To ensure that all RCTs were identified, the authors of significant papers were contacted.

5. Language

No language restrictions were applied when selecting studies.

Data collection and analysis

1. Selection of studies

In September 2005, two review authors (TA and JO) checked hard copies of the references identified by the search strategy to identify studies meeting the following broad and simple criteria: i) randomised trials; ii) incurable cancer patients (this included subjects with incurable, advanced, metastatic, or terminal cancer. When the participants were mixed‐stage cancer patients, studies in which more than 80% of the participants had an advanced stage of cancer (stage III, IV, or recurrent) were eligible for inclusion in the review); and iii) assessment of depression.

The inter‐rater reliability of the two raters were evaluated using percentage agreement and kappa coefficient. All studies identified by either of the two raters were then subjected to the next stage of critical appraisal according to the strict eligibility criteria.

2. Quality assessment

Two independent review authors (TA and TO) assessed the methodological quality of the selected studies. We used Newell's methodological quality criteria (Newell 2002), which includes the following points: i) adequate concealment of allocation; ii) patients randomly selected; iii) patients blinded to treatment group; iv) care‐providers blinded to treatment group; v) except for study intervention, equivalence of other treatments; vi) care‐providers' adherence monitored; vii) detailed lost‐to‐follow‐up information; viii) percentage of patients not included in analyses; ix) intention‐to‐treat analyses; and x) outcomes measured in a blinding fashion.

The maximum score for each study was 30 points, with higher scores indicating higher quality. As previously reported, the quality of a study was considered to be good if the study had a total score greater than 20 points, fair if it scored 11 to 20 points, and poor if it scored less than 11 points (Newell 2002).

The inter‐rater reliability of these validity criteria was evaluated using Cohen's weighted kappa. Those studies with clearly inadequate concealment of random allocation were excluded. The influences of the other quality indices were examined using sensitivity analyses.

3. Data extraction

Two review authors (TA and TO) independently extracted data from the original reports using data extraction forms. Any disagreement was resolved by consensus between the two or, where necessary, between all the review authors. Extracted data included the country of origin, the nature and content of psychological intervention and the patient group involved, the duration of the study, the study setting, the sample size, and the key outcomes using validated instruments.

4. Data synthesis

Planned method

Data were to be entered by JO into Review Manager 4.2.10 twice, using the duplicate data entry feature. For dichotomous outcomes, the relative risk (RR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were to be calculated using the random‐effects model, since the RR of the random‐effects model has been shown to be superior in clinical interpretability and external generalisability than the fixed‐effect models and odds ratios (OR) or risk differences (Furukawa 2002). The heterogeneity among the studies was to be assessed using the I‐squared and Q statistics and by visual inspection of the results in the Meta View plots. An I2 greater than 30% or a Q statistic P value of less than 0.1 was to be considered indicative of heterogeneity. If significant heterogeneity was suspected, the sources were to be investigated. For dichotomous outcomes of response, two analytical strategies were to be adopted; first, a 'per protocol' analysis was to be performed according to the values reported by the original authors. When data on dropouts were included, usually by way of the last‐observation‐carried‐forward (LOCF) method, this data was to be analysed according to the primary studies. For continuous outcomes, the standardized mean difference (SMD) was to be pooled using the random‐effects model. Continuous outcomes were to be analysed on an endpoint basis, including only patients with a final assessment or with a last observation carried forward to the final assessment. A strict ITT analysis was not feasible with continuous outcomes, as the studies performed only LOCF or endpoint analyses.

Actual method

Data were entered by TA into Review Manager 4.2.10 twice using the duplicate data entry feature. Analysis of dichotomous outcomes was planned, but only one study (Wu 2003) included this. Post‐treatment scores were available in three studies (Wu 2003; Liossi 2001; Linn 1982) while change scores were available or could be calculated in six studies (Goodwin 2001; Classen 2001; Edelman 1999; Wood 1997; Linn 1982; Spiegel 1981). We therefore modified the data synthesis method during the review because the data obtained could not be synthesized appropriately using the planned method. The change between the baseline and immediate post‐treatment scores was selected as the primary outcome for the meta‐analysis (Banerjee 2006). The SMD and 95% CIs were pooled using a random‐effects model (Alderson 2004). Two studies provided data on the results of slope analyses (Classen 2001; Spiegel 1981), and we calculated the change scores using these data. One paper provided raw data only (Wood 1997); for these data, we calculated the change score using SPSS 10.0J version software for Windows (SPSS 2003). In addition, because we could not obtain the actual figures for the standard deviations in the change scores for depression, anxiety, and general psychological distress in two studies (Classen 2001; Linn 1982), we calculated the pooled standard deviations in the other available studies that utilized the same measuring instrument (the Profile of Mood States) (MaNair 1992) (Edelman 1999; Goodwin 2001; Spiegel 1981; Wood 1997) and these values were inputted for the missing data (Furukawa 2006).

The heterogeneity among the studies was assessed using the I2 and Q statistics and by visual inspection of the results in Meta View plots. An I2 value greater than 30% or a Q statistic with a P value less than 0.1 were considered indicative of heterogeneity. If significant heterogeneity was suspected, the source of it was investigated.

5. Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses should be performed and interpreted with caution because multiple analyses can lead to false‐positive conclusions (Oxman 1992). However, we performed the following subgroup analyses, if possible, for the following a priori reasons:

A separate analysis was performed for participants who received group psychotherapy, since different modalities of psychotherapy (i.e., group versus individual) could have different effects.

A separate analysis was performed for breast cancer patients, because many psycho‐oncology studies focus on this patient group.

A separate analysis was performed for participants with clinical depression based on any cut‐off points or diagnostic criteria of depression measures, because the effect of psychotherapy on depression may differ according to the baseline depressive status.

A separate analysis was performed for participants receiving interventions by direct verbal or interactive communication delivered by health care professionals, or both, because this type of psychotherapy may have a different effect on depression.

6. Funnel plot analysis and sensitivity analyses:

A funnel plot analysis was performed to check for any publication bias.

A sensitivity analysis was performed, if possible, to examine the robustness of the observed findings by repeating all the analyses using only high‐quality studies.

Results

Description of studies

Two independent review authors checked the studies identified by the search sources, and a total of 176 studies were extracted for possible inclusion. Full copies of these articles were obtained, and the two independent review authors then examined the strict eligibility of these papers. Further reference searches and a SciSearch did not yield any additional studies that satisfied the strict eligibility criteria. The inter‐rater reliability of the strict eligibility criteria were as follows: kappa coefficient, 0.84, percent concordance, 95.5%.

First, we identified 16 studies that were potentially suitable for inclusion (Classen 2001; Edelman 1999; Giasson 1998; Goodwin 2001; Laidlaw 2005; Linn 1982; Liossi 2001; Mantovani 1996; North 1992; Sarna 1998; Schofield 2003; Sloman 2002; Soden 2004; Spiegel 1981; Wood 1997; Wu 2003). However, five of these studies (Giasson 1998; North 1992; Sarna 1998; Schofield 2003; Soden 2004) were ultimately dropped after a discussion among the review authors because the interventions in these studies were not forms of psychotherapy. The interventions in these studies were as follows: aromatherapy (Soden 2004), a multisensory environment (Schofield 2003), a structured nursing assessment of symptoms (Sarna 1998), noncontact therapeutic touch (Giasson 1998), and information provided by tape‐recordings of consultations (North 1992). In addition, one study was excluded because of the absence of usual care in the control group (Mantovani 1996). Finally we identified ten studies that were suitable for inclusion (total of 780 participants) (Classen 2001; Edelman 1999; Goodwin 2001; Laidlaw 2005; Linn 1982; Liossi 2001; Sloman 2002; Spiegel 1981; Wood 1997; Wu 2003).

The subjects of the meta‐analysis were recruited from three main groups: patients with metastatic breast cancer (five studies), patients who had received some form of palliative care (three studies), and various patients with advanced cancer (two studies).

Various types of interventions were utilized in these ten studies. Five studies (Classen 2001; Goodwin 2001; Linn 1982; Spiegel 1981; Wu 2003) mainly used supportive psychotherapy. Three studies mainly investigated the effect of behavioural therapies, either relaxation techniques (Sloman 2002) or hypnosis (Laidlaw 2005; Liossi 2001). The other studies used cognitive behavioural therapy (Edelman 1999) and problem‐solving therapy (Wood 1997). The duration of the interventions was variable, ranging from just three to five sessions (Wood 1997) to unlimited and continuing until death (Spiegel 1981). Three of the five studies using supportive psychotherapy and the one study using cognitive behavioural therapy utilized group treatment sessions. Thus, the ten selected studies included several kinds of interventions, all of which involved direct verbal and interactive communication delivered by health care professionals (Classen 2001; Edelman 1999; Goodwin 2001; Laidlaw 2005; Liossi 2001; Linn 1982; Sloman 2002; Spiegel 1981; Wood 1997; Wu 2003). There were no interventions belonging to non‐pharmacological interventions other than the aforementioned ones.

Risk of bias in included studies

With regard to study quality, none of the studies met the criteria for a 'good' rating. Three studies met the criteria for a 'fair' rating (Goodwin 2001; Linn 1982; Wu 2003), and the remaining seven studies were judged as having a 'poor' rating. Two studies clearly described the procedure for adequate allocation concealment (Goodwin 2001; Linn 1982).

Effects of interventions

Two studies did not report the effects of the interventions on depression (Laidlaw 2005; Wood 1997), although they did measure the severity of depression among the participating subjects. As described above, all of the remaining eight studies used interventions involving direct verbal and interactive communication delivered by health care professionals (Classen 2001; Edelman 1999; Goodwin 2001; Linn 1982; Liossi 2001; Sloman 2002; Spiegel 1981; Wu 2003).

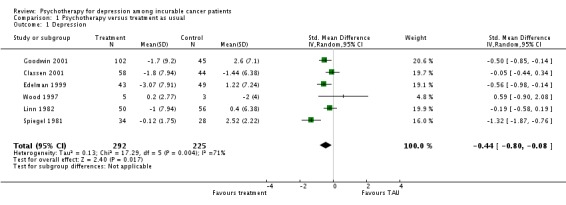

Effects of psychotherapy on depression: meta‐analyses

Moderate and statistically significant heterogeneity among six studies (see below) was observed (P = 0.004, I2 = 71%). The identified studies were quite heterogeneous with regard to their participants and interventions, and many studies did not include some of the data required for meta‐analyses. Consequently, we decided to conduct the meta‐analyses by combining the data from studies in which the change scores were available. Thus, we excluded four studies because they did not contain necessary data, such as the change score, the standard deviation of the change score, or the number of participants (Laidlaw 2005; Liossi 2001; Sloman 2002; Wu 2003). The data from the six studies that provided all the information needed to conduct the meta‐analyses were combined; all of these studies had used the Profile of Mood States as a measure of depression (Classen 2001; Edelman 1999; Goodwin 2001; Linn 1982; Spiegel 1981; Wood 1997). Among these six studies, four studies used supportive psychotherapy (Classen 2001; Goodwin 2001; Linn 1982; Spiegel 1981), one utilized cognitive behavioural therapy (Edelman 1999) and one utilized problem‐solving therapy (Wood 1997). Regarding the data from the study by Linnet al., we decided to use the data obtained one month after intervention to minimize the effects of drop‐outs, although the study provided data on depression at five time points during the intervention (Linn 1982).

The combined data from the six studies, involving 292 patients in the psychotherapy arm and 225 patients in the control arm, showed that psychotherapy had a significant effect on the treatment of depression among participants with advanced cancer (SMD = ‐0.44, 95% CI = ‐0.08 to ‐0.80). Visual inspection of the Meta View plots suggested that the study conducted by either Spiegel et al. or Wood et al. contributed most of the heterogeneity (Wood 1997; Spiegel 1981). While the heterogeneity indicators were similar if the study by Wood et al (Wood 1997) was excluded (Chi2 = 15.49, df = 4 (P = 0.004), I2 = 74%), the heterogeneity diminished and was no longer statistically significant if the study by Spiegel et al was excluded (Chi2 = 5.93, df = 4 [P = 0.20], I2 = 32.6%). The source of the heterogeneity was further investigated by examining the patient group, measuring instrument, type and duration of intervention, treatment of control group, outcome data and so on; however, clear factors that might have produced the heterogeneity could not be identified.

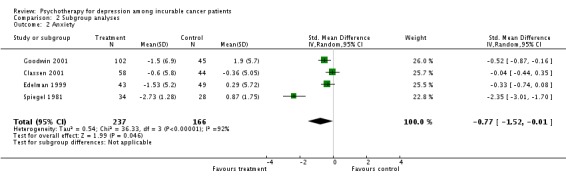

Effect of psychotherapy on anxiety and general psychological distress: meta‐analyses

Since one study did not measure anxiety (Linn 1982), we combined the data from five studies (Classen 2001; Edelman 1999; Goodwin 2001; Spiegel 1981; Wood 1997). The combined data, involving 242 patients in the psychotherapy arm and 169 patients in the control arm, showed that psychotherapy had a borderline effect on anxiety among participants with advanced cancer (SMD = ‐0.68, 95% CI = 0.01 to ‐1.37). Strong, statistically significant heterogeneity was observed (P < 0.00001, I2 = 89.1%). Visual inspection of the Meta View plots suggested that the study conducted by Spiegel et al. was heterogeneous (Spiegel 1981). When this study was omitted, the significant heterogeneity was no longer observed (Chi2 = 3.22, df = 3 [P = 0.36], I2 = 6.8%).

Four studies provided data on general psychological distress, as evaluated using the total mood disturbance score of the POMS (Classen 2001; Edelman 1999; Goodwin 2001; Spiegel 1981). The combined data, involving 237 participants in the psychotherapy arm and 166 participants in the control arm, showed a significant effect for psychotherapy on general psychological distress among participants with advanced cancer (SMD = ‐0.94, 95% CI = ‐0.01 to ‐1.87). A strong, statistically significant heterogeneity was observed (P < 0.00001, I2 = 94.3%). Visual inspection of the Meta View plots again suggested that the study conducted by Spiegel et al. was heterogeneous (Spiegel 1981). When this study was omitted, the significant heterogeneity was no longer observed (Chi2 = 2.43, df = 2 (P = 0.30), I2 = 17.8%).

Other secondary outcomes

We deleted some secondary endpoints, including symptom control, quality of life, coping measures for participants, and severity of physical symptoms (like pain), because few studies provided this kind of data. In addition, we stopped checking the tolerability of the treatment and the dichotomous outcomes for the same reason.

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

The two planned subgroup analyses (for participants who underwent group psychotherapy and for breast cancer patients) were conducted using the same four studies that investigated the effectiveness of group psychotherapy among metastatic breast cancer patients (Classen 2001; Edelman 1999; Goodwin 2001; Spiegel 1981). The results demonstrated similar and significant findings for all three targeted psychological symptoms: depression, anxiety, and general psychological distress.

The other subgroup analysis (for participants with clinical depression) was not conducted as none of the studies included the participants with clinically diagnosed depression. In addition, as described in the aforementioned section ('Effects of psychotherapy on depression: meta‐analyses'), the planned subgroup analysis for participants receiving interventions via direct verbal and interactive communication delivered by health care professionals was not performed.

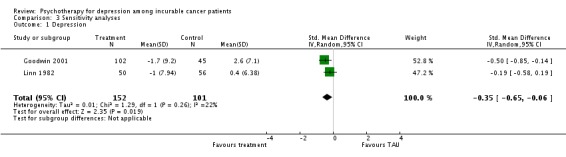

As only two studies included in the meta‐analysis were judged to be of good or fair quality (Goodwin 2001; Linn 1982), a sensitivity analysis limited to these studies was performed. However, the study conducted by Linn et al. did not include anxiety and general psychological distress measures, so we conducted the sensitivity analysis for depression only. The combined data, involving 152 patients in the psychotherapy arm and 101 patients in the control arm, showed that psychotherapy was significantly effective for the treatment of depression (SMD = ‐0.35, 95% CI = ‐0.06 to ‐0.65). Statistically significant heterogeneity was not observed (P = 0.26, I2 = 22.4%).

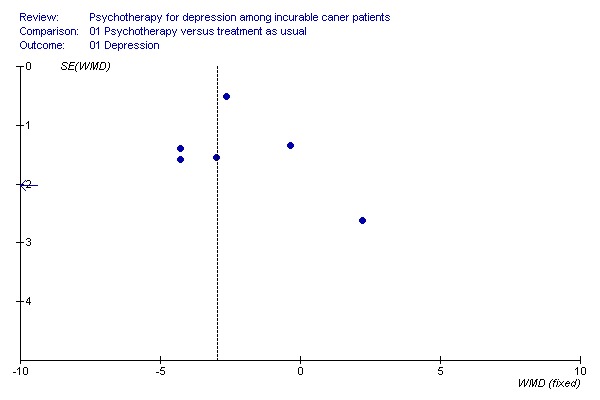

Although the number of included studies was small, thereby limiting the usefulness of a visual inspection of the funnel plot (Figure 1; Figure 2; Figure 3), a visual inspection did not suggest a prominent publication bias.

Figure 1.

Funnel plot for the outcome depression

Figure 2.

Funnel plot for the outcome anxieety

Figure 3.

Funnel plot for the outcome total mood disturbance

Discussion

Current findings

This is the first systematic review, including a meta‐analysis so far as we are aware, to show the significant effectiveness of verbal and interactive psychotherapeutic intervention for treating depression among advanced cancer patients. Unfortunately, the effectiveness of other types of non‐pharmacological interventions for the treatment of depression could not be analysed because the available data on this topic was insufficient.

Our findings suggest that the effects of psychotherapy are almost comparable to those obtained in antidepressant pharmacotherapy studies in general psychiatry settings (Bech 2000). On the other hand, this effect was not consistent with a previous meta‐analysis of 17 clinical trials that investigated the effect of psychological interventions on depression in cancer patients (Sheard 1999). This previous meta‐analysis indicated an effect size of 0.19, suggesting a clinically weak or negligible effect. Since the subjects of the majority of the studies included in this previous meta‐analysis were not advanced cancer patients and most of the studies had selected their patient populations based on cancer diagnosis, rather than on diagnostic or psychological criteria, or both, differences in the prevalence of clinical depression may be one possible explanation for the discrepancy between their meta‐analysis and ours. In other words, since depression is common in patients with advanced cancer (see 'Background'), this difference may account for the different findings regarding the effect of the intervention.

Regarding the types of verbal and interactive psychotherapeutic interventions that were included in the meta‐analysis, four of the six psychotherapeutic approaches utilized supportive therapy. Probably because of the nature of the study subjects (i.e., people suffering from incurable cancer), all of the approaches involved some form of techniques dealing with the impact of life‐threatening disease on patients' lives, including issues of 'dying' or 'existence', or both, in addition to general support (Spiegel 1978; Yalom 1977). In addition, one of the most prominent characteristics of these four studies was the fact that the interventions essentially continued until the patients' deaths. On the other hand, specific types of psychotherapy, especially cognitive behavioural therapy, are widely recommended for the treatment of psychological distress among cancer patients; however, our systematic review highlights the need for more well‐designed clinical trials to clarify the effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy on depression in patients with advanced cancer.

The findings with regard to anxiety and general psychological distress were similar to those for depression, although the results for anxiety did not reach statistical significance. These findings suggest that the psychotherapy may be useful for ameliorating a broad range of psychological distress, with the exception of anxiety experienced by advanced cancer patients.

Clinical implications and future research

The present findings suggest that the depression experienced by advanced cancer patients, who are well‐known to be at risk for developing depression or clinically profound psychological distress, or both, can be effectively ameliorated by psychotherapeutic intervention. Although our review could not clarify the cost effectiveness of psychotherapeutic interventions for patients with advanced cancer, and the fact that long‐term continuous interventions requiring trained mental health professionals may not be easy to provide for all patients, our findings suggest that psychological interventions should be combined with routine patient care for the treatment of patients with advanced cancer. At the same time, clarifying the cost‐effectiveness of psychotherapy and developing cost‐effective interventions for treating depression among advanced cancer patients may be important future tasks.

Some relevant questions remain concerning the effectiveness of psychotherapy on depression among patients with incurable cancer. First, because most studies included in the meta‐analysis investigated the impact of the interventions just after or during the process of continuous treatment, or both, the persistent effects of the completed interventions were unclear. Second, because most of the subjects were not clinically diagnosed as having depression, the effectiveness of psychotherapy for the treatment of clinical depression could not be clarified in this review. These clinically important issues should be addressed in future studies.

Finally, we would like to comment on the study quality of the psychological interventions. As reported in the previous reviews, the quality of most of the studies was problematic (Newell 2002; Williams 2006). However, given the difficulty of conducting clinical trials in this population, such as in palliative care settings and of evaluating the quality of clinical trials for psychological interventions (Penrod 2004), novel and realistic quality assessment systems may be needed for studies focusing on patients with advanced cancer.

Methodological advantages of this study

This systematic review has several major strengths. Firstly, we performed systematic and comprehensive literature searches for relevant studies, whereas previous studies contained several major flaws in their methodology, including a language bias (e.g., typically only English papers), and the combination of randomised and non‐randomized clinical trials. Second, the a priori planned heterogeneity and sensitivity analyses indicated that the results of the analyses were quite robust.

Limitations of this study

Our review also has some limitations. First, the reviewed studies generally had small sample sizes, and only a small number of studies (n = 6) were included in the meta‐analysis. These factors may limit the validity of our findings. The existence of a possible outcome reporting bias cannot be negated (Chan 2005; Furukawa 2007). Secondly, although the use of data imputation for missing standard deviations of change scores was found to be valid in one study dealing with pharmacotherapy for depression (Furukawa 2006), whether this procedure was valid in our study sample was not confirmed. Thirdly, while this review included studies on the treatment of depression among advanced cancer patients, the results may not be applicable to advanced cancer patients with clinically diagnosed depression. Additionally, although this study also included meta‐analyses for anxiety and general psychological distress, these findings were subsidiary and inconclusive. Finally, because the subjects' physical status (e.g., physical functioning, estimated survival) were not clearly defined a priori and the participants were at least not critically terminally ill (i.e. an estimated survival period of less than a few months), the findings may not be applicable to end‐stage cancer patients who are nearing death.

Despite these limitations, the obtained findings about the usefulness of psychotherapy for ameliorating depression in advanced cancer patients deserve important consideration, and future studies to investigate and clarify the usefulness of psychotherapy for treating clinically diagnosed depression in terminally ill patients are warranted.

Authors' conclusions

Evidence from RCTs of moderate quality suggests that psychotherapy is useful for treating depressive states in advanced cancer patients although little evidence supports the effectiveness of psychotherapy for patients with clinically diagnosed depression including major depressive disorder. The effects of psychotherapy are almost comparable to those observed in antidepressant pharmacotherapy studies of major depressive disorders in general psychiatry settings. Regarding the types of verbal and interactive psychotherapeutic interventions, the most common approach was long‐term continuous supportive therapy, typically until the patients' deaths. Although our review could not clarify the cost effectiveness of psychotherapeutic interventions for patients with advanced cancer and considering that long‐term continuous interventions requiring trained mental health professionals may not be easy to provide for all patients, our findings suggest that psychological interventions should be combined with routine patient care for the treatment of patients with advanced cancer.

The continuing effects of the completed interventions and the effectiveness of psychotherapy for the treatment of clinical depression should be addressed in future studies. In addition, clarifying the cost‐effectiveness of psychotherapy and developing cost‐effective interventions for the treatment of depression among advanced cancer patients are also important future tasks. Specific types of psychotherapy, especially cognitive behavioural therapy, are widely recommended for the treatment of psychological distress among cancer patients; however, our systematic review highlights the need for more well‐designed clinical trials to clarify the effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy on depression in patients with advanced cancer. The effectiveness of psychotherapy for treating depression in end‐stage cancer patients who are nearing death should also be investigated. Finally, given the difficulty of conducting clinical trials in palliative care settings and of evaluating the quality of clinical trials for psychological interventions, novel and realistic quality assessment systems may be needed for studies focusing on patients with advanced cancer.

Acknowledgements

This systematic review was conducted within the framework of the Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Review Group, and we acknowledge their help and support. This study was supported in part by a Grant‐in‐Aid from the Cancer Research and Second‐Term Comprehensive Ten‐Year Strategy for Cancer Control from the Ministry of Labour, Health and Welfare of Japan.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE via OVID search strategy

1. exp PSYCHOTHERAPY/ 2. (psychotherap$ or aromatherap$ or "art therap$" or "autogenic training" or "behavior$ adj6 therap$" or (behaviour$ adj6 therap$) or (biofeedback and psycho$) or (cognitive adj6 therap$) or (desensiti$ and psychol$) or "implosive therap$" or (relax$ adj6 therap$) or (relax$ adj6 techniq$) or (therap$ adj6 touch$) or yoga) 3. (bibliotherapy or (color$ adj6 therap$) or (colour$ adj6 therap$) or (music$ adj6 therap$) or (hypno$ adj6 therap$) or (imagery and psychotherap$) or counsel$ or (group$ adj6 therap$) or "socioenvironmental therap$" or "socio environmental therap$" or "milieu therap$" or "therapeutic communit$" or (famil$ adj6 therap$) or psychosoc$ or psycholog$ or "self help group$" or (support$ adj6 group$) or (guide$ adj6 image$)) 4. or/1‐3 5. Depression/ 6. (depression or depressive$ or depressed) 7. or/5‐6 8. exp NEOPLASMS/ 9. (tumor$ or tumour$ or cancer$ or carcinoma$ or malignan$ or neoplas$) 10. or/8‐9 11. 4 and 7 and 10

The above search strategy was run with the following filter for Controlled Clinical Trials: Cochrane Sensitive Search strategy for RCTs for MEDLINE on OVID (published in appendix 5b Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 4.2.5 May 2005) 1. randomized controlled trial.pt. 2. controlled clinical trial.pt. 3. randomized controlled trials.sh. 4. random allocation.sh. 5. double blind method.sh. 6. single blind method.sh. 7. or/1‐6 8. (ANIMALS not HUMAN).sh. 9. 7 not 8 10. clinical trial.pt. 11. exp clinical trials/ 12. (clin$ adj25 trial$).ti,ab. 13. ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).ti,ab. 14. placebos.sh. 15. placebo$.ti,ab. 16. random$.ti,ab. 17. research design.sh. 18. or/10‐17 19. 18 not 8 20. 19 not 9 21. 9 or 19

Appendix 2. Other search strategies

| Database searched | Search strategy used |

| PaPaS TRIALS REGISTER | ((psychotherapy OR psychotherapy* OR aromatherapy* OR "art therapy" OR "autogenic training" OR "behavior* therapy" OR "behaviour* therap*" OR (biofeedback AND psycho*) OR "cognitive therapy" OR "cognitive behavioural therap*" OR (desensiti* AND psychol*) OR "implosive therapy" OR "relaxation therap*" OR "relaxation technique*" OR "therapeutic touch" OR "touch therap*" OR yoga OR bibliotherapy OR "colour therap*" OR "colour therapy" OR "music therapy" OR hypnotherapy OR (imagery AND psychotherapy*) OR counsel* OR "group therap*" OR "socioenvironmental therapy" OR "socio‐environmental therapy" OR "milieu therapy" OR "therapeutic community" OR "family therap*" OR psychosoc* OR psycholog* OR "self help group*" OR "support* group*" OR "guided imagery") AND (depression OR depressive$ OR depressed) AND (neoplasms OR tumor$ OR tumour$ OR cancer$ OR carcinoma$ OR malignan$ OR neoplas$)) |

| CENTRAL | #1 PSYCHOTHERAPY (explode all trees MeSH) #2 (psychotherap* or aromatherap* or (art next therap*) or (autogenic next training) or (behavior* near therap*) or (behaviour* near therap*) or (biofeedback and psycho*) or (cognitive near therap*) or (desensiti* and psychol*) or (implosive near therap*) or (relax* near therap*) or (relax* near techniq*) or (therap* near touch*) or yoga) #3 (bibliotherapy or (color* near therap*) or (colour* near therap*) or (music* near therap*) or (hypno* near therap*) or (imagery AND psychotherap*) or counsel* or (group* NEAR therap*) or (socioenvironmental next therap*) or (socio next environmental next therap*) or (milieu next therap*) or (therapeutic communit*) or (famil* near therap*) or psychosoc* or psycholog* or self help group* or support* NEAR group* or guide* NEAR image*) #4 (#1 or #2 or #3) #5 DEPRESSION (single term MeSH) #6 (depression or depressive* or depressed) #7 (#5 or #6) #8 NEOPLASMS (explode all trees MeSH) #9 (tumor* or tumour* or cancer* or carcinoma* or malignan* or neoplas*) #10 (#8 or #9) #11 (#4 and #7 and #10) |

| EMBASE via Embase.Com | (('psychotherapy'/exp AND [embase]/lim) OR ((psychotherap* OR aromatherap* OR 'art therapy' OR 'autogenic training' OR 'behavior therapy' OR 'behavioural therapy' OR ('biofeedback' AND psycho*) OR 'cognitive therapy' OR 'cognitive behavioural therapy' OR 'cognitive behavioural therapies' OR (desensiti* AND psychol*) OR 'implosive therapy' OR 'relaxation therapy' OR 'relaxation therapies' OR 'relaxation technique' OR 'relaxation techniques' OR 'theraputic touch' OR 'touch therapy' OR 'touch teherapies' OR 'yoga') AND [embase]/lim AND [embase]/lim) OR ((bibliotherapy OR 'color therapy' OR 'colour therapy' OR 'color therapies' OR 'colour therapies' OR 'music therapy' OR 'hypnotherapy' AND imagery AND psychotherap* OR counsel* OR 'group therapy' OR 'group therapies' OR 'socioenvironmental therapy' OR 'socio environmental therapy' OR 'milieu therapy' OR 'theraputic community' OR 'family therapy' OR 'family therapies' OR psychosoc* OR psycholog* OR 'self help group' OR 'self help groups' OR 'support group' OR 'support groups' OR 'supportive group' OR 'supportive groups' OR 'guided imagery') AND [embase]/lim)) AND ((depression OR depressive* OR depressed AND [embase]/lim) OR ('depression'/exp AND [embase]/lim)) AND (('neoplasm'/exp AND [embase]/lim) OR ((tumor* OR tumour* OR cancer* OR carcinoma* OR malignan* OR neoplas*) AND [embase]/lim)) The above subject search was linked to the following Filter for EMBASE via EMBASE.com ((random*:ti,ab) OR (factorial*:ab,ti) OR (crossover*:ab,ti OR 'cross over':ab,ti OR 'cross over':ab,ti) OR (placebo*:ab,ti) OR ('double blind' OR 'double blind') OR ('single blind':ab,ti OR 'single blind':ab,ti) OR (assign*:ti,ab OR allocat*:ti,ab) OR (volunteer*:ab,ti) OR ('randomized controlled trial'/exp AND [embase]/lim) OR ('single blind procedure'/exp AND [embase]/lim) OR ('double blind procedure'/exp AND [embase]/lim) OR ('crossover procedure'/exp AND [embase]/lim)) NOT ((animal/ OR nonhuman/ OR 'animal'/de AND experiment/ AND [embase]/lim) NOT ((human/ AND [embase]/lim) AND (animal/ OR nonhuman/ OR 'animal'/de AND experiment/ AND [embase]/lim)) AND [embase]/lim) AND [embase]/lim |

| CINAHL via OVID | (Search Strategy as for MEDLINE but run with the following filter for Controlled Trials in CINAHL) 1. Random Assignment/ 2. single‐blind studies/ 3. Double‐Blind Studies/ 4. Triple‐Blind Studies/ 5. Crossover Design/ 6. Factorial Design/ 7. (multicentre study or multicenter study or multi‐centre study or multi‐center study).mp. [mp=title, cinahl subject headings, abstract, instrumentation] 8. random$.ti,ab. 9. latin square.ti,ab. 10. cross‐over.mp. or crossover.ti,ab. [mp=title, cinahl subject headings, abstract, instrumentation] 11. Placebos/ 12. ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).ti,ab. 13. placebo$.mp. [mp=title, cinahl subject headings, abstract, instrumentation] 14. Clinical Trials/ 15. (clin$ adj25 trial$).mp. [mp=title, cinahl subject headings, abstract, instrumentation] 16. or/1‐15 |

| PubMed Cancer Subset | #1 PSYCHOTHERAPY (MeSH) #2 (psychotherap* or aromatherap* or (art AND therap*) or (autogenic AND training) or (behavior* AND therap*) or (behaviour* AND therap*) or (biofeedback and psycho*) or (cognitive AND therap*) or (desensiti* and psychol*) or (implosive AND therap*) or (relax* AND therap*) or (relax* AND techniq*) or (therap* AND touch*) or yoga) #3 (bibliotherapy or (color* AND therap*) or (colour* AND therap*) or (music* AND therap*) or (hypno* AND therap*) or (imagery and psychotherap*) or counsel* or (group* AND therap*) or (socioenvironmental AND therap*) or (socio‐environmental AND therap*) or (milieu AND therap*) or (therapeutic AND communit*) or (famil* AND therap*) or psychosoc* or psycholog* or (self AND help AND group*) or (support* AND group*) or (guide* AND image*) #4 #1 OR #2 OR #3 #5 DEPRESSION (MeSH) #6 depression or depressive* or depressed #7 #5 OR #6 #8 NEOPLASMS (explode MeSH) #9 tumor* or tumour* or cancer* or carcinoma* or malignan* or neoplas* #10 #8 OR #9 #11 #4 AND #7 AND #10 All Fields, Limits: Cancer The above search strategy was linked to the following Cochrane filter for PubMed: (randomized controlled trial [pt] OR controlled clinical trial [pt] OR randomized controlled trials [mh] OR random allocation [mh] or double‐blind method [mh] or single‐blind method [mh] or clinical trial [pt] or clinical trials [mh] or ("clinical trial" [tw] or ((singl*) [tw] or doubl* [tw] or trebl* [tw] or tripl* [tw]) AND (mask* [tw] OR blind* [tw])) OR (placebos [mh] OR placebo* [tw] OR random* [tw] OR research design [mh:noexp]) NOT (animals [mh] NOT human [mh]) |

| PsychINFO via OVID | 1. exp PSYCHOTHERAPY/ 2. (psychotherap$ or aromatherap$ or "art therap$" or "autogenic training" or "behavior$ therap$" or (behaviour$ adj6 therap$) or (biofeedback and psycho$) or (cognitive adj6 therap$) or (desensiti$ and psychol$) or "implosive therap$" or (relax$ adj6 therap$) or (relax$ adj6 techniq$) or (therap$ adj6 touch$) or yoga) 3. (bibliotherapy or (color$ adj6 therap$) or (colour$ adj6 therap$) or (music$ adj6 therap$) or (hypno$ adj6 therap$) or (imagery and psychotherap$) or counsel$ or (group$ adj6 therap$) or "socioenvironmental therap$" or "socio environmental therap$" or "milieu therap$" or "therapeutic communit$" or (famil$ adj6 therap$) or psychosoc$ or psycholog$ or "self help group$" or (support$ adj6 group$) or (guide$ adj6 image$)) 4. or/1‐3 5. exp RECURRENT DEPRESSION/ or exp REACTIVE DEPRESSION/ or exp TREATMENT RESISTANT DEPRESSION/ or exp "DEPRESSION (EMOTION)"/ or exp MAJOR DEPRESSION/ 6. (depression or depressive$ or depressed) 7. or/5‐6 8. exp NEOPLASMS/ 9. (tumor$ or tumour$ or cancer$ or carcinoma$ or malignan$ or neoplas$) 10. or/8‐9 11. 4 and 7 and 10 The above subject search strategy was run with the following filter: CCT/RCT Filter for Embase (SRB revised) 1. (randomi$ or (control$ adj3 trial$)).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, table of contents, key concepts] 2. ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj (blind$ or mask$)).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, table of contents, key concepts] 3. placebo$.mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, table of contents, key concepts] 4. exp PLACEBO/ 5. crossover.mp. 6. exp Treatment Effectiveness Evaluation/ 7. or/1‐6 |

| LILACS via www.bireme.br | ((psychotherapy OR psychotherap$ OR aromatherap$ OR (art AND therapy) OR (autogenic AND training) OR (behavior$ AND therapy) OR (behaviour$ AND therapy) OR (biofeedback AND psycho$) OR (cognitive AND therapy) OR (cognitive AND behavioural AND therapy) OR (cognitive AND behavioural AND therapies) OR (desensiti$ AND psychol$) OR (implosive AND therapy) OR (relaxation AND therapy) OR (relaxation AND therapies) OR (relaxation AND technique$) OR (theraputic AND touch) OR (touch AND therapy) OR (touch AND therapies) OR yoga OR bibliotherapy OR (color AND therapy) OR (colour AND therapy) OR (color AND therapies) OR (colour AND therapies) OR (music AND therapy) OR hypnotherapy OR (imagery AND psychotherap$) OR counsel$ OR (group AND therapy) OR (group AND therapies) OR (socioenvironmental AND therapy) OR (socio‐environmental AND therapy) OR (milieu AND therapy) OR (therapeutic AND community) OR (family AND therapy) OR (family AND therapies) OR psychosoc$ OR psycholog$ OR (self AND help AND group) OR (self AND help AND groups) OR (support AND group) OR (support AND groups) OR (supportive AND group) OR (supportive AND groups) OR (guided AND imagery)) AND (depression OR depressive$ OR depressed OR depression) AND (neoplasms OR tumor$ OR tumour$ OR cancer$ OR carcinoma$ OR malignan$ OR neoplas$)) |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1.

Psychotherapy versus treatment as usual

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Depression | 6 | 517 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.44 [‐0.80, ‐0.08] |

| 2 Anxiety | 5 | 411 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.68 [‐1.37, 0.01] |

| 3 Total Mood Disturbance | 4 | 403 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.94 [‐1.87, ‐0.01] |

Analysis 1.1.

Comparison 1 Psychotherapy versus treatment as usual, Outcome 1 Depression.

Analysis 1.2.

Comparison 1 Psychotherapy versus treatment as usual, Outcome 2 Anxiety.

Analysis 1.3.

Comparison 1 Psychotherapy versus treatment as usual, Outcome 3 Total Mood Disturbance.

Comparison 2.

Subgroup analyses

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Depression | 4 | 403 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.58 [‐1.02, ‐0.13] |

| 2 Anxiety | 4 | 403 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.77 [‐1.52, ‐0.01] |

| 3 Total Mood Disturbance | 4 | 403 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.94 [‐1.87, ‐0.01] |

Analysis 2.1.

Comparison 2 Subgroup analyses, Outcome 1 Depression.

Analysis 2.2.

Comparison 2 Subgroup analyses, Outcome 2 Anxiety.

Analysis 2.3.

Comparison 2 Subgroup analyses, Outcome 3 Total Mood Disturbance.

Comparison 3.

Sensitivity analyses

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Depression | 2 | 253 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.35 [‐0.65, ‐0.06] |

Analysis 3.1.

Comparison 3 Sensitivity analyses, Outcome 1 Depression.

What's new

Last assessed as up‐to‐date: 11 February 2008.

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 14 October 2016 | Review declared as stable | See Published notes. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2005 Review first published: Issue 2, 2008

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 17 June 2013 | Amended | There has been a delay in updating this review. The authors are in the process of updating and we anticipate publication in early 2014. |

| 24 September 2010 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 7 November 2008 | Amended | Further adjustments for RevMan 5 conversion. |

| 9 July 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 125 women with metastatic breast cancer; American | |

| Interventions | Supportive‐expressive group psychotherapy, including fostering support among group members and encouraging the expression of emotions, psychoeducation, and self‐hypnosis exercise (90 minutes weekly session lasting at least one year) | |

| Outcomes | Profile of Mood States, Impact of Event scale | |

| Notes | Quality score: 10 It is reported that the group therapy did not improve depression | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 124 women with metastatic breast cancer; Australian | |

| Interventions | Group cognitive behavior therapy (8 weekly sessions) | |

| Outcomes | Profile of Mood States, Coopersmith Self‐esteem Inventory | |

| Notes | Quality score: 7 It is reported that the therapy improved depression | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 235 women with metastatic breast cancer; Canadian | |

| Interventions | Supportive‐expressive group psychotherapy, including fostering support among group members and encouraging the expression of emotions about cancer and its effects on their lives (90 minutes weekly session lasting at least one year) | |

| Outcomes | Profile of Mood States, Pain scale, Suffering scale, Survival | |

| Notes | Quality score: 17 It is reported that the group therapy improved depression | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 37 women with metastatic breast cancer; English | |

| Interventions | 1. Self ‐hypnosis, including both anti‐stress and anxiety techniques and visualization techniques (four weeks) 2. Johrei, a healing technique developed in Japan, is non‐touch, and requires the practitioner to visualize healing light entering the body and being transferred via the outstretched hand to the recipient with a spirit of goodwill towards the other person (four weeks) | |

| Outcomes | Beck Depression Inventory, Profile of Mood States Bi‐Polar‐Form, State Trait Anxiety Inventory, Impact of Event Scale, EORTC QLQ‐C30, BR23 (Assessment was conducted after at least three months of practice) | |

| Notes | Quality score: 5 The statistical results regarding depression were not reported | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | One hundred and twenty men with end‐stage cancer (clinical stage IV) identified on wards of a large general hospital; American | |

| Interventions | Counseling, including reducing denial, maintaining hope, life review, support for families (several times a week till death) | |

| Outcomes | Profile of Mood States, life satisfaction, self‐esteem, alienation, locus of control (one, three, six, nine, 12 months after the treatment) | |

| Notes | Quality score: 13 It is reported that the therapy improved depression at three months | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Fifty terminally ill cancer patients who were referred for palliative care; Greek | |

| Interventions | Hypnosis, including induction, suggestions for symptom management and ego‐strengthening, and post hypnotic suggestions for comfort and maintenance of the therapeutic benefits (30‐minutes four weekly sessions) | |

| Outcomes | Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale, Rotterdam Symptom Checklist (four weeks after the start of the treatment) | |

| Notes | Quality score: 9 It is reported that the therapy improved depression | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Fifty six advanced cancer patients receiving home palliative care who were experiencing anxiety and depression; Australian | |

| Interventions | Progressive muscle relaxation and guided imagery (twice weekly) | |

| Outcomes | Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale, Functional Living Index‐Cancer scale (three weeks after the initial session) | |

| Notes | Quality score: 4 It is reported that significant positive changes occurred for depression | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Eighty six women with metastatic breast cancer; American | |

| Interventions | Psychological support group, including fostering support among group members and encouraging the expression of emotions (90 minutes weekly session lasting at least one year) | |

| Outcomes | Profile of Mood States, Rotter Internal/External Locus of Control Scale, Health Locus of Control Scale, Self‐esteem (from the Janis‐Field Scale), Maladaptive coping response, Phobias, Denial | |

| Notes | Quality score: 9 The original study revealed "The treatment group tended (although not significantly) to be less depressed" on the basis of the findings about slopes analysis that investigated the score change per 100 days. On the other hand, because we set the outcome at the end of the study in the protocol, we recalculated the score change during 300 days. Consequently the score change has become to be statistically significant. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Twenty cancer patients who were referred to hospice home care teams; English | |

| Interventions | Problem‐solving therapy (three to five sessions) | |

| Outcomes | Profile of Mood States, Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale, modified Social Adjustment Scale | |

| Notes | Quality score: 9 The statistical results regarding depression were not reported | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | One hundred and twenty lung cancer patients receiving chemotherapy combined with radiotherapy; Chinese | |

| Interventions | Supporting psychotherapy, including cognitive therapy, patient self‐help group, behavioral therapy, and family education | |

| Outcomes | Self‐Rating Depression Scale, Self‐Rating Anxiety Scale (one month after the start of the treatment ) | |

| Notes | Quality score: 12 It is reported that the patients of the treatment group made a significant progress in relieving the depression compared with the control group | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Edmonds 1999 | Although the POMS‐Short Form was used as a psychological measure, this questionnaire cannot assess depression |

| Giasson 1998 | The intervention (noncontact therapeutic touch) was not considered as psychotherapy |

| Mantovani 1996 | The study did not include the usual care in the control group |

| North 1992 | The intervention (information giving by tape‐recording the consultation) was not considered as psychotherapy |

| Sarna 1998 | The intervention (structured nursing assessment of symptom) was not considered as psychotherapy |

| Schofield 2003 | The intervention (use of multisensory environment [Snoezelen]) was not considered as psychotherapy |

| Soden 2004 | The intervention (aromatherapy, including massages with lavender essential oil and an inert oil) was not considered as psychotherapy |

Contributions of authors

T Akechi, J Onishi, T Morita, and TA Furukawa: conceptualized and designed the study. T Akechi, T Okuyama, and J Onishi: conducted the systematic review. T Akechi: conducted the statistical analysis of the study. TA Furukawa: supervised the process of the systematic review. All authors: interpreted the data and wrote the report.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Nagoya City University Medical School, Japan.

External sources

Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan.

Declarations of interest

None known

Notes

This review is correct at the date of publication. This review has now been stabilised following discussion with the editors and authors. If appropriate, we will update the review if new evidence likely to change the conclusions is published, or if standards change substantially which necessitate major revisions.

Stable (no update expected for reasons given in 'What's new')

References

References to studies included in this review

- Classen C, Butler LD, Koopman C, Miller E, DiMiceli S, Giese‐Davis J, et al. Supportive‐expressive group therapy and distress in patients with metastatic breast cancer: a randomized clinical intervention trial. Archives of General Psychiatry 2001;58(5):494‐501. [] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 3291256

- Edelman S, Bell DR, Kidman AD. A group cognitive behaviour therapy programme with metastatic breast cancer patients. Psychooncology 1999;8(4):295‐305. [] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 3291258

- Goodwin PJ, Leszcz M, Ennis M, Koopmans J, Vincent L, Guther H, et al. The effect of group psychosocial support on survival in metastatic breast cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2001;345(24):1719‐26. [] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 3291260

- Laidlaw T, Bennett BM, Dwivedi P, Naito A, Gruzelier J. Quality of life and mood changes in metastatic breast cancer after training in self‐hypnosis or johrei: a short report. Contemporary Hypnosis 2005;22(2):84‐93. [] [Google Scholar]; 3291288

- Linn MW, Linn BS, Harris R. Effects of counseling for late stage cancer patients. Cancer 1982;49(5):1048‐55. [] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 3291268

- Liossi C, White P. Efficacy of clinical hypnosis in the enhancement of quality of life of terminally ill cancer patients. Contemporary Hypnosis 2001;18(3):145‐60. [] [Google Scholar]; 3291290

- Sloman R. Relaxation and imagery for anxiety and depression control in community patients with advanced cancer. Cancer Nursing 2002;25(6):432‐5. [] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 3291310

- Spiegel D, Bloom JR, Yalom I. Group support for patients with metastatic cancer. A randomized outcome study. Archives of General Psychiatry 1981;38(5):527‐33. [] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 3291274

- Wood BC, Mynors‐Wallis LM. Problem‐solving therapy in palliative care. Palliative Medicine 1997;11(1):49‐54. [] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 3291276

- Wu L, Wang S. Psychotherapy improving depression and anxiety of patients treated with chemotherapy combined with radiotherapy. Chinese Journal of Clinical Rehabilitation 2003;7(17):2462‐3. [] [Google Scholar]; 3291316

References to studies excluded from this review

- Edmonds CV, Lockwood GA, Cunningham AJ. Psychological response to long‐term group therapy: a randomized trial with metastatic breast cancer patients. Psychooncology 1999;8(1):74‐91. [] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 3291282

- Giasson M, Bouchard L. Effect of therapeutic touch on the well‐being of persons with terminal cancer. Journal of Holistic Nursing 1998;16(3):383‐98. [] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 3291284

- Mantovani G, Astara G, Lampis B, Bianchi A, Curreli L, Orru W, et al. Evaluation by multidimensional instruments of health‐related quality of life of elderly cancer patients undergoing three different "psychosocial" treatment approaches. A randomized clinical trial. Supportive Care in Cancer 1996;4(2):129‐40. [] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 3291294

- North N, Cornbleet MA, Knowles G, Leonard RC. Information giving in oncology: a preliminary study of tape‐recorder use. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 1992;31(Pt 3):357‐9. [] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 3291300

- Sarna L. Effectiveness of structured nursing assessment of symptom distress in advanced lung cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum 1998;25(6):1041‐8. [] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 3291304

- Schofield P, Payne S. A pilot study into the use of a multisensory environment (Snoezelen) within a palliative day‐care setting. International Journal of Palliative Nursing 2003;9(3):124‐30. [] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 3291306

- Soden K, Vincent K, Craske S, Lucas C, Ashley S. A randomized controlled trial of aromatherapy massage in a hospice setting. Palliative Medicine 2004;18(2):87‐92. [] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 3291312

Additional references

- Akechi T, Okamura H, Nishiwaki Y, Uchitomi Y. Psychiatric disorders and associated and predictive factors in patients with unresectable nonsmall cell lung carcinoma: a longitudinal study. Cancer 2001;92(10):2609‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderson P, Green S, Higgins JPT. Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook 4.2.2. Chichester, UK: Wiley‐Blackwell, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S, Wells G. Caveats in the meta‐analysis of continuous data: a simulation study. XIVth Cochrane Colloquium. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bech P, Cialdella P, Haugh MC, Birkett MA, Hours A, Boissel JP, et al. Meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials of fluoxetine versus placebo and tricyclic antidepressants in the short‐term treatment of major depression. British Journal of Psychiatry 2000;176:421‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block SD. Assessing and managing depression in the terminally ill patient. ACP‐ASIM End‐of‐Life Care Consensus Panel. American College of Physicians ‐ American Society of Internal Medicine. Annals of Internal Medicine 2000;132(3):209‐18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukberg J, Penman D, Holland JC. Depression in hospitalized cancer patients. Psychosomatic Medicine 1984;46(3):199‐212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassileth BR, Lusk EJ, Strouse TB, Miller DS, Brown LL, Cross PA. A psychological analysis of cancer patients and their next‐of‐kin. Cancer 1985;55(1):72‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan AW, Altman DG. Epidemiology and reporting of randomised trials published in PubMed journals. Lancet 2005;365:1159‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colleoni M, Mandala M, Peruzzotti G, Robertson C, Bredart A, Goldhirsch A. Depression and degree of acceptance of adjuvant cytotoxic drugs. Lancet 2000;356(9238):1326‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Morrow GR, Fetting J, Penman D, Piasetsky S, Schmale AM, et al. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among cancer patients. Jounal of American Medical Association 1983;249(6):751‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine EC, Westlake SK. The effects of psychoeducational care provided to adults with cancer: meta‐analysis of 116 studies. Oncology Nursing Forum 1995;22(9):1369‐81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa TA, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE. Can we individualize the 'number needed to treat'? An empirical study of summary effect measures in meta‐analyses. International Journal of Epidemiology 2002;31(1):72‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa TA, Barbui C, Cipriani A, Brambilla P, Watanabe N. Imputing missing standard deviations in meta‐analyses can provide accurate results. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2006;59:7‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa TA, Watanabe N, Omori I, Montori, VM, Guyatt G. Association between unreported outcomes and effect size estimates in Cochrane meta‐analyses. Journal of American Medical Association 2007;297:468‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassi L, Indelli M, Marzola M, Maestri A, Santini A, Piva E, et al. Depressive symptoms and quality of life in home‐care‐assisted cancer patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 1996;12(5):300‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksson MM, Isometsa ET, Hietanen PS, Aro HM, Lonnqvist JK. Mental disorders in cancer suicides. Journal of Affective Disorders 1995;36(1‐2):11‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kugaya A, Akechi T, Okuyama T, Nakano T, Mikami I, Okamura H, et al. Prevalence, predictive factors, and screening for psychologic distress in patients with newly diagnosed head and neck cancer. Cancer 2000;88(12):2817‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppleman LF. Edits manual for the Profile of Mood States. San Diego: Edits/Educational and Industrial Testing Service, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel JS, Musselman DL, Porter MR, Reed DA, Nemeroff CB. Depression in patients with cancer. Diagnosis, biology, and treatment. Archives of General Psychiatry 1995;52(2):89‐99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell SA, Sanson‐Fisher RW, Savolainen NJ. Systematic review of psychological therapies for cancer patients: overview and recommendations for future research. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2002;94(8):558‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura H, Watanabe T, Narabayashi M, Katsumata N, Ando M, Adachi I, et al. Psychological distress following first recurrence of disease in patients with breast cancer: prevalence and risk factors. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 2000;61(2):131‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuyama T, Nakane Y, Endo C, Seto T, Kato M, Seki N, et al. Mental health literacy in Japanese cancer patients: ability to recognize depression and preferences of treatments‐comparison with Japanese lay public. Psychooncology 2007;16(9):834‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxman AD, Guyatt GH. A consumer's guide to subgroup analyses. Annals of Internal Medicine 1992;116(1):78‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penrod JD, Morrison RS. Challenges for palliative care research. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2004;7:398‐402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto JM, Blanch J, Atala J, Carreras E, Rovira M, Cirera E, et al. Psychiatric morbidity and impact on hospital length of stay among hematologic cancer patients receiving stem‐cell transplantation. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2002;20(7):1907‐17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross L, Boesen EH, Dalton SO, Johansen C. Mind and cancer: does psychosocial intervention improve survival and psychological well‐being?. European Journal of Cancer 2002;38(11):1447‐57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheard T, Maguire P. The effect of psychological interventions on anxiety and depression in cancer patients: results of two meta‐analyses. British Journal of Cancer 1999;80(11):1770‐80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel D, Yalom ID. A support group for dying patients. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 1978;28:233‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS Japan Inc. SPSS. Version 11.5.1 J for Windows. Tokyo, Japan: SPSS Japan Inc, 2003.

- Williams S, Dale J. The effectiveness of treatment for depression/depressive symptoms in adults with cancer: a systematic review. British Journal of Cancer 2006;94:372‐90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yalom ID, Greaves C. Group therapy with the terminally ill. American Journal of Psychiatry 1977;134:396‐400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]