Abstract

Background

This is an updated version of the original review that was first published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 4. Laparoscopy has become an increasingly common approach to surgical staging of apparent early‐stage ovarian tumours. This review was undertaken to assess the available evidence on the benefits and risks of laparoscopy compared with laparotomy for the management of International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage I ovarian cancer.

Objectives

To evaluate the benefits and harms of laparoscopy in the surgical treatment of FIGO stage I ovarian cancer (stages Ia, Ib and Ic) when compared with laparotomy.

Search methods

For the original review, we searched the Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Group Trials (CGCRG) Register, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2007, Issue 2), MEDLINE, Embase, LILACS, Biological Abstracts and CancerLit from 1 January 1990 to 30 November 2007. We also handsearched relevant journals, reference lists of identified studies and conference abstracts. For the first updated review, the search was extended to the CGCRG Specialised Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and LILACS to 6 December 2011. For this update we searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and Embase from November 2011 to September 2016.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), quasi‐RCTs and prospective cohort studies comparing laparoscopic staging with open surgery (laparotomy) in women with stage I ovarian cancer according to FIGO.

Data collection and analysis

There were no studies to include, therefore we tabulated data from non‐randomised studies (NRSs) for discussion as well as important data from other meta‐analyses.

Main results

We performed no meta‐analyses.

Authors' conclusions

This review has found no good‐quality evidence to help quantify the risks and benefits of laparoscopy for the management of early‐stage ovarian cancer as routine clinical practice.

Plain language summary

Laparoscopy versus laparotomy (open surgery) for early‐stage ovarian cancer

Background Stage I ovarian cancer is diagnosed when the tumour is confined to one or both ovaries, without spread to lymph nodes or other parts of the body. Approximately 25% of women with ovarian cancer will be diagnosed at an early stage, thus the diagnosis often occurs due to an accidental finding. The intention of surgical staging is to establish a diagnosis, to assess the extent of the cancer and to remove as much tumour as possible. The latter is particularly important as women with ovarian cancer survive for longer when all visible tumour has been removed.

Review question We conducted this review in an attempt to clarify whether laparoscopy (keyhole surgery) is as safe and effective as laparotomy (open surgery) for early‐stage ovarian cancer. We intended to include only high‐quality studies that compared the two types of surgery. We wanted to know whether women having laparoscopy survived as long as those having open surgery and whether there were differences in the time it took for the cancer to get worse. We were also interested to see how these different surgeries compared with regard to blood loss and other complications.

Main findings and quality of the evidence We search the literature from 1990 to 2106. Unfortunately, we were unable to find any high‐quality randomised trials comparing these approaches.

Background

Description of the condition

This is the second updated version of the original review that was first published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 4.

Ovarian cancer is the eighth most common cancer in women worldwide (Jemel 2011). A woman's risk of developing ovarian cancer before the age of 75 ranges from 0.5% in developing countries to 1% in developed countries (GLOBOCAN 2008; Jemel 2011). Just over a third of women with ovarian cancer are alive five years after diagnosis (EUROCARE 2003), largely because most women with ovarian cancer are diagnosed when the cancer is already at an advanced stage (Jemal 2008). International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage I ovarian cancer (limited to the ovaries) is diagnosed in approximately 20% to 33% of women with ovarian cancer in developed countries (Maringe 2012) and diagnosis is usually made by accidental discovery at sonography, computerised tomography (CT scanning) or during laparoscopy. The incidence of accidental discovery of ovarian cancer at laparoscopy has been estimated to range from 0.65% (Wenzl 1996) to 0.9% (Muzii 2005) of premenopausal women and 3% of postmenopausal women who undergo the procedure for an adnexal mass (Muzii 2005), but may be higher depending on the selection criteria applied.

Most cancers of the ovary are epithelial (90%) with histological subtypes including serous (35%), endometrioid (10%), borderline (16%), mucinous (8%), clear cell (4%), undifferentiated and mixed epithelial (Kosary 2007). In general, the prognosis of ovarian tumours depends on the FIGO stage, tumour grade, histological subtype, age and the volume of residual disease after surgery (Benedet 2000), however for stage I tumours the most important prognostic indicators are considered to be the degree of differentiation (grade) and the occurrence of tumour rupture (Vergote 2001).

The standard management of women with ovarian cancer is comprehensive surgical staging by laparotomy, a midline abdominal incision that allows exposure of the entire abdomen. Comprehensive surgical staging includes a total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo‐oophorectomy, removal of all obvious sites of tumour, aspiration of cytological washings or ascites, omentectomy, retroperitoneal (pelvic and para‐aortic) lymph node dissection or sampling and biopsy of all suspicious‐looking areas including mesentery, liver and diaphragm (Benedet 2000; Schorge 2012). Systematic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RLND) may improve survival in stage I ovarian cancer by detecting microscopic disease (Chan 2007), and is considered a standard procedure in some centres (Schorge 2012), however the UK National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines currently do not recommend RLND in stage I disease (NICE 2011).

A meta‐analysis of four randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of adjuvant platinum‐based chemotherapy, which included data from the International Collaborative Ovarian Neoplasm 1 (ICON1) trial (Trimbos 2003) and the Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Ovarian Neoplasm (ACTION) trial (Trimbos 2004), found that adjuvant chemotherapy significantly improved overall survival (OS) and progression‐free survival (PFS) in women with early ovarian cancer (Winter‐Roach 2012). However, it was considered not to be necessary in women with comprehensively staged, stage Ia or 1b grade 1 to 2 tumours, as subgroup analyses suggested that women who were optimally staged were unlikely to benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy. Hence, comprehensive surgical staging has an important impact on the subsequent management of women with early ovarian cancer, with adjuvant chemotherapy indicated when staging is considered to be inadequate (Elit 2004; Winter‐Roach 2012).

Description of the intervention

The intention of surgical staging is to establish a diagnosis, to assess the extent of the disease and to remove as much gross tumour as possible (Schorge 2012). Surgical staging of ovarian cancer by laparoscopy is the same intra‐abdominal procedure as that performed by laparotomy except that it involves two or more, much smaller, abdominal incisions, through which laparoscopic instruments are then inserted. Specimen retrieval bags are used to prevent spillage and possible seeding of cyst contents and to avoid contact with incision (port) sites. Cysts may be aspirated within the retrieval bag, or morcellated if solid, to facilitate extraction through the port sites (Ghezzi 2007). Larger specimens, like omentum, may be extracted through the vagina with the uterus after hysterectomy (Lee 2011; Park 2008a).

How the intervention might work

Several non‐randomised studies (NRSs) in early ovarian cancer have reported that laparoscopic surgical staging is a safe and technically feasible procedure (Colomer 2008; Ghezzi 2009; Nezhat 2009; Park 2008b; Park 2010). The possible advantages of laparoscopy include smaller incisions, less blood loss, faster recovery, shorter hospital stay, fewer complications, less postoperative infection and a better visualisation of the tumour inside the abdomen as the laparoscopy image can be magnified (Gad 2011; Ghezzi 2007; Lee 2011). In addition, the shorter recovery period following laparoscopy means that chemotherapy can be commenced sooner compared with laparotomy (Ghezzi 2007; Nezhat 2009), potentially resulting in a favourable effect on survival.

However, laparoscopy has been associated with a higher rate of intraoperative cyst rupture for apparently benign (Muzii 2005) and borderline tumours (Fauvet 2005), which may result in upstaging of the unexpected ovarian cancer from stage Ia or 1b to Ic (Muzii 2005). It has been argued that some aspects of comprehensive surgical staging, particularly RLND, may be technically difficult to achieve via laparoscopy and, therefore, that laparoscopy should be restricted to women with pre‐operative evidence of benign conditions only (Vergote 2004). Other disadvantages of laparoscopy may include longer operating times and the possibility of port‐site metastases, although the risk of the latter in early disease is considered to be low (Schorge 2012). Furthermore, to facilitate laparoscopy, CO₂ is commonly used for pneumoperitoneum and has been shown to lower the peritoneal pH (Bergstrom 2008; Kuntz 2000), which may activate enzymes that increase tumour cell mitosis and growth factor production. In addition, mechanical damage to the mesothelium may occur with prolonged laparoscopic surgery, thereby increasing the risk of metastases in the abdominal cavity (Greene 1995; Volz 1999).

Why it is important to do this review

Laparoscopic surgical staging of stage I ovarian cancer remains controversial as it is unclear how the risks and benefits of this procedure compare with the conventional open approach by laparotomy. Both earlier versions of this systematic review, published in 2008 and in 2013, found insufficient evidence to evaluate laparoscopy for the management of early ovarian cancer as routine clinical practice. We continue to update this review with the aim of clarifying and consolidating the available evidence regarding this alternative surgical approach.

Objectives

To evaluate the benefits and harms of laparoscopy in the surgical treatment of FIGO stage I ovarian cancer (stages Ia, Ib and Ic) when compared with laparotomy.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs. We also considered prospective cohort studies where the results had been adjusted for the baseline case mix using multivariate analyses, and excluded those with historical (non‐concurrent) controls.

Types of participants

Women with stage I ovarian cancer defined by FIGO as follows.

Stage Ia: unilateral tumours

Stage Ib: bilateral tumours

Stage Ic: identified tumour spillage, tumour capsular penetration, positive peritoneal cytology

Types of interventions

Surgical staging via laparoscopy (experimental group) versus laparotomy (control group) for stage I ovarian cancer

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Overall survival (OS)

Progression‐free survival (PFS)

Secondary outcomes

Operating time

Intraoperative tumour rupture

Pelvic and para‐aortic lymph node yield

Size of omental specimen

Estimated blood loss and the need for blood transfusion

Comprehensive staging achieved by the allocated procedure (conversion to laparotomy)

Surgical complications (immediate and delayed) including: injuries to the bladder, ureter, blood vessels, nerves, small bowel and colon; febrile morbidity; intestinal obstruction; haematomas and infections

Length of hospital stay

Time to adjuvant chemotherapy

Systemic complications

Abdominal wall recurrence: laparoscopy (port sites) and laparotomy (midline incision)

Quality of life

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We conducted searches to identify all published and unpublished RCTs and NRSs that compared laparoscopy and laparotomy for stage I ovarian cancer. The search strategies identified studies in all languages and, when necessary, we translated non‐English language papers so that they could be fully assessed for potential inclusion in the review.

For the original review, we searched the Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Review Group (CGCRG) Trials Register, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2007, Issue 2), MEDLINE (January 1990 to November 2007), Embase (1990 to November 2007), LILACS (1990 to November 2007), Biological Abstracts (1990 to November 2007) and CancerLit (1990 to November 2007).

For the first updated version, we extended these searches to 6 December 2011.

For this second updated version of the review we extended the search to 7 September 2016. Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2016, Issue 9), MEDLINE (November 2011 to August week 4 2016), Embase (2011 week 48 to 2016 week 36). See Appendix 1, Appendix 2, and Appendix 3 for search strategies.

Searching other resources

We handsearched the citation lists of relevant publications and included studies, and contacted experts in the field to identify further trials. For the original review we also handsearched the following conferences and publications: Gynecologic Oncology, International Journal of Gynaecological Cancer, British Journal of Cancer, British Cancer Research Meeting, Annual Meetings of the International Gynaecologic Cancer Society, Annual Meetings of the American Society of Gynecologic Oncologists, Annual Meetings of the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO), and Annual Meetings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors sifted the searches and identified potentially eligible studies. All authors assessed the methodology of these potentially eligible studies according to the specific inclusion criteria. Review authors were not blind to the authors, institutions or journals of potentially relevant studies.

Data extraction and management

No studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria for the original review or both the updated versions. For future versions of this review, two review authors will independently extract data from included trials to a pre‐designed data collection sheet that includes the following information.

Study methodology: description of randomisation, blinding, number of study centres, study duration, length of follow‐up and number of study withdrawals.

Participants: number, mean age, mean risk score.

Intervention: type of intervention, dose and schedule.

-

Outcomes:

we will extract data to allow for intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis where possible;

for dichotomous outcomes (e.g. number of lymph nodes, complications or deaths), we will extract outcome rates to estimate a risk ratio (RR);

for continuous outcomes (e.g. quality of life (QoL) measures and duration of treatment), we will extract means and standard deviations (SD) to estimate a mean difference (MD);

for time‐to‐event outcomes (e.g. OS), we will extract the log of the hazard ratio (log(HR)) and its standard error (SE) from trial reports. If these are not reported, we will attempt to estimate the log (HR) and its SE Parmar's methods (Parmar 1998).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For future versions of this review, we will assess the risk of bias in included studies using Cochrane's 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011) and the following criteria:

selection bias: random sequence generation and allocation concealment;

performance bias: blinding of participants and personnel (patients and treatment providers);

detection bias: blinding of outcome assessment;

attrition bias: incomplete outcome data;

reporting bias: selective reporting of outcomes;

other possible sources of bias.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

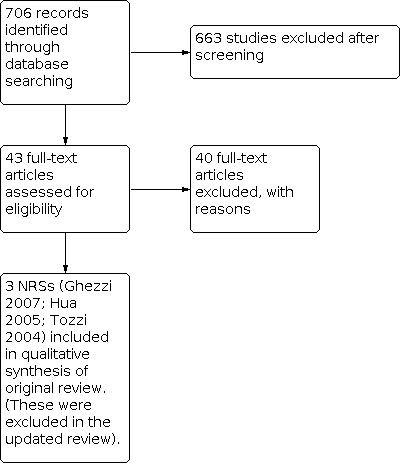

The original search identified 706 citations, of which we retrieved 43 for detailed examination. We subsequently excluded 40 of these records and three NRSs (two case‐control studies and one case series) were included in the original review (Ghezzi 2007; Hua 2005; Tozzi 2004; Figure 1). For this updated review, we excluded these NRSs but tabled their findings with other similar studies that were identified by the updated search (see Differences between protocol and review).

1.

Study flow diagram of original search 17 May 2007

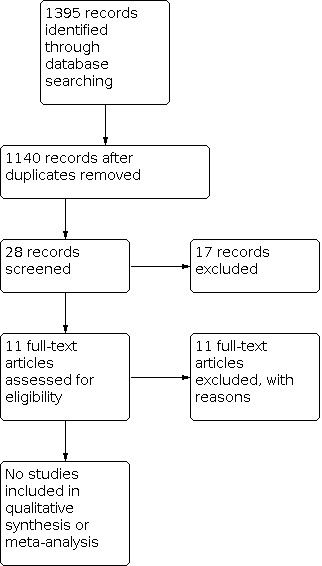

From the first updated search we identified 1395 records (1140 after de‐duplication), 28 of which we screened for possible relevance. Of these, 11 new studies were identified for classification (Chen 2010; Chi 2005; Colomer 2008; Ghezzi 2009; Lee 2011; Nezhat 2009; Park 2008a; Park 2008b; Park 2010; Park 2011a; Wu 2010; Figure 2). Park 2008b, Park 2010 and Park 2011a are extensions of the same series.

2.

Study flow diagram of updated search 30 November 2011

From the second updated search we identified 1806 records (1530 after de‐duplication), 32 of which we screened for possible relevance. Of these, 21 new studies were identified for classification (Bae 2014; Bogani 2014; Brockbank 2013; Ditto 2014; Ditto 2015; Gallotta 2016; Hong 2011; Kim 2014; Kobal 2013; Koo 2014; Leblanc 2014; Liu 2014; Lu 2014; Lu 2015; Minig 2015; Montanari 2013; Moon 2012; Park 2011b; Park 2013; Yoon 2011; Zhang 2015).

Included studies

There were no studies that met the inclusion criteria.

Excluded studies

Altogether we excluded 87 studies. None of these studies met the inclusion criteria in Types of studies. We have summarised the results of the relevant case series, case‐control studies and retrospective cohort studies in three tables: Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. None of the comparative NRSs reported adjusting results for baseline characteristics and we considered all of them to be at a high risk of selection bias and other bias (e.g. outcome assessment bias).

1. Case series of comprehensive laparoscopic staging of early ovarian cancer (including fallopian tube cancer).

| No. of women | Mean pelvic nodes (n) | Mean para‐aortic nodes (n) | Mean para‐aortic nodes and pelvic nodes (n) | Median follow‐up (months) | Recurrences (n) | PFS (%) | OS (%) | |

| Querleu 1994 | 8 | ‐ | 8.6 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Pomel 1995 | 8 | 7.5 | 8.5 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Childers 1995 | 14 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Tozzi 2004 | 24 | 19.4 | 19.6 | ‐ | 46 | 2 | 92 | 100 |

| Leblanc 2004 | 42 | 14 | 20 | ‐ | 54 | 3/34 ¹ | 91 | 98 |

| Colomer 2008 | 20 | 18 | 11.3 | ‐ | 24.7 | 1 | 95 | 100 |

| Ghezzi 2009 | 26 | 24.5 | 9.8 | ‐ | 26.7 | 1 | 96 | 96 |

| Nezhat 2009 | 36 | 14.8 | 12.2 | ‐ | 55.9² | 3 | 92 | 100 |

| Chen 2010 | 43 | 16.6 | 6.5 | ‐ | 24.7 | 3 | 93 | ‐ |

| Moon 2012 | 24 | ‐ | ‐ | 37.2 | 22.3 | 0 | ‐ | ‐ |

| Montanari 2013 | 19 | 17 | 14 | ‐ | 30 | 3 | 84 | 100 |

| Brockbank 2013 | 35 | 6 | 5.6 | ‐ | 18 | 2 | 94 | 100 |

| Yoon 2011 | 38 | ‐ | ‐ | 29.46 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

Abbreviations: PFS = progression‐free survival; OS = overall survival; n = number ¹Leblanc 2004 reported recurrences in confirmed stage I women only, i.e. excluding 8 women who were upstaged| ²Mean follow‐up.

2. Case‐control studies of laparoscopic surgical staging versus open surgical staging of early ovarian cancer.

| Study name | Hua 2005 | Chi 2005 | Ghezzi 2007 | Bogani 2014* | Ditto 2015 | Gallotta 2016 | Minig 2015 | ||||||||||||||

| Period | 2002‐2004 | 2000‐2003 | 2003‐2006 | 2003‐2010 | Not described | 2007‐2013 | 2006‐2014 | ||||||||||||||

| Design | Prospective cohort | Retrospective case‐control | Case‐control (with historical controls 1997‐2003) | Case‐control (with historical controls 1990‐2003) | Case‐control (with historical controls) | Case‐control (with historical controls 2000‐2011) | Retrospective case‐control | ||||||||||||||

| Intervention | LPS | LPT | P value | LPS | LPT | P value | LPS | LPT | P value | LPS | LPT | P value | LPS | LPT | P value | LPS | LPT | P value | LPS | LPT | P value |

| Number of women | 10 | 11 | ‐ | 20 | 30 | ‐ | 15 | 19 | ‐ | 35 | 32 | ‐ | 37 | 37 | ‐ | 60 | 120 | 50 | 58 | ‐ | |

| Mean age | 40 | 42 | ‐ | 47.3 | 50.6 | 0.31 | 55 | 61 | 0.05 | 52 | 56 | 0.35 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 48 | 55 | 0.001 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| BMI (kg/m²) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 24.6 | 25.4 | 0.64 | 23.8 | 25.8 | 0.19 | 24.1 | 22.6 | 0.56 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Mean operating time (min) | 298 | 182 | < 0.05 | 321 | 276 | 0.04 | 377 | 272 | 0.002 | 335 | 230 | <0.001 | 213 | 212 | 0.74 | NS | NS | 0.01⁴ | 222 | 214 | 0.482 |

| Mean blood loss (mL) (SD) | 280 | 346 | < 0.05 | 235 | 367 | 0.003 | 250 | 400 | 0.28 | 300 | 400 | 0.28 | 157 | 442 | <0.001 | NS | NS | 0.032⁴ | 229 | 684 | <0.0001 |

| Blood transfusion n (%) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 1 (6.7) | 2 (10.5) | 1.0 | 1 (3) | 7 (22) | 0.02 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 3 (6) | 20 (34) | <0.0001 |

| Pelvic lymph nodes, n | 25¹ | 27¹ | NS | 12.3 | 14.7 | NS | 25.2 | 25.1 | 0.96 | 22 | 15 | 0.002 | 15.8¹ | 27.7¹ | 0.04 | 16¹ | 18 | 0.464 | 16 | 15 | 0.472 |

| Para‐aortic nodes, n | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 6.7 | 9.2 | NS | 6.5 | 7 | 0.78 | 10 | 6 | 0.08 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 10 | 13 | 0.217 |

| Omental specimen (cm³) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 186 | 347 | 0.09 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Intra‐operative tumour spillage, n (%) | 0 | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 3 (20) | 2 (10.5) | 0.63 | 6 (17) | 4 (12) | 0.59 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Postoperative complications n (%) | 2 (20%) ² | 7 (72.7%) | < 0.01 | 0 (0) | 3 (10) | ‐ | 2 (13.3%) | 8 (42.1%) | 0.13 | 1 (3) | 9 (28) | 0.005 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 14 (28) | 22 (38) | 0.275 |

| Hospital stay (days) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 3.1 | 5.8 | < 0.001 | 3 | 7 | 0.001 | 4 | 6 | 0.03 | 3.3 | 17 | <0.001 | 3 | 7 | 0.001 | 2.42 | 5.67 | <0.0001 |

| Final diagnosis = stage I, n (%) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 11 (73.3) | 13 (68.4) | ‐ | 20 (57) | 17 (53) | 0.74 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Tumour upstaged, n (%) | 0 | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 4 (26.7) | 6 (31.6) | 1.0 | 6 (17) | 3 (9) | NS | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 12 (24) | 8 (14) | 0.173 |

| Conversion to LPT, n | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 0 | NA | ‐ | 0 | NA | ‐ | 0 | ‐ | NA | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 1 (2%) | NS | ‐ |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy, n (%) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 11 (73.3) | 13 (68.4) | ‐ | 32 | 24 | 0.1 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 42 (70) | NS | NS | 37 (74) | 34 (58.5) | 0.093 |

| Time to adjuvant chemotherapy (days) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 22 | 30 | <0.001 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 37 | 41 | 0.318 |

| Median follow‐up in months (range) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 16 (4‐34) | 60 (32‐108) | ‐ | 64 (37‐106) | 100 (61‐287) | <0.001 | 60.8 | 125.8 | NS | 38 (24‐48) | NS | 26 | 37 | 0.004 | |

| Port‐site/abdominal wound metastasis, n | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 0 | 0 | NA | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 0 | NS | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Recurrences, n (%) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 0 | 4 (21) | ‐ | 4 (11) | 9 (28) | 0.12 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 5 (8.3) | 16 (13.3) | 0.651 | 6 (12) | 7 (12) | 0.785 |

| OS, n (%) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 15 (100) | 19 (100) | ‐ | NS | NS | 0.26 | ‐³ | ‐³ | P > 0.2 | 55 (92) | 109 (91) | 0.719 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

Abbreviations: LPS = laparoscopy; LPT, laparotomy; BMI = body mass index; PFS = progression‐free survival; OS = overall survival; n = number; NA = not applicable; SD = standard deviation; NS = not specified ¹Lymph nodes not specified as pelvic or para‐aortic in origin ²Right obturator nerve damaged and repaired in one patient ³Stated as survival outcomes ⁴Favouring the laparoscopic group

3. Retrospective cohort studies of laparoscopic surgical staging versus open surgery for early ovarian cancer.

| Study name | Park 2008a | Park 2008b | Park 2010** | Park 2011a | Lee 2011 | Koo 2014 | Liu 2014 | Hong 2011 | ||||||||||||||||

| Study period | 2004‐2008 | 2004‐2007 | 2004‐2008 | 2004‐2010 | 2005‐2010 | 2006‐2012 | 2002‐2010 | 2000‐2005 | ||||||||||||||||

| Intervention | LPS | LPT | P value | LPS | LPT | P value | LPS | LPT | P value | LPS | LPT | P value | LPS | LPT | P value | LPS | LPT | P value | LPS | LPT | P value | LPS | LPT | P value |

| Number of women | 17 | 19 | ‐ | 19 | 33 | ‐ | 40 | 76 | ‐ | 84 | 128 | ‐ | 26 | 87 | ‐ | 24 | 53 | ‐ | 35 | 40 | ‐ | 18 | 17 | ‐ |

| Mean age (years) | 43.2 | 48.9 | 0.155 | 43.9 | 45.4 | 0.614 | ‐ | ‐ | NS | ‐ | ‐ | NS | 42 | 44.4 | 0.437 | 45.8 | 48.4 | 0.246 | 51.09 | 50.78 | NS | 49 | 48 | 0951 |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 22.8 | 24.2 | 0.247 | 23.2 | 22.7 | 0.578 | ‐ | ‐ | NS | ‐ | ‐ | NS | 21.9 | 23.3 | 0.185 | 22.9 | 23.7 | 0.353 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 22 | 24 | 0.164 |

| Mean operating time (min) | 303.8 | 290.4 | 0.706 | 221 | 275 | 0.012 | 230 | 278 | 0.001 | 207 | 262 | < 0.001 | 228 | 184 | 0.016 | 192.9 | 224.1 | 0.127 | 209.71 | 200.50 | NS | 121 | 139 | 0.295 |

| Mean blood loss (mL) | 231 | 505 | 0.001 | 240 | 569 | 0.005 | 301 | 494 | 0.004 | 252 | 454 | < 0.001 | 230 | 475 | < 0.001 | 697.9 | 972.6 | 0.127 | 197.14 | 345 | NS | 100 | 109 | 0.812 |

| Blood transfusion, n (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (11) | ‐ | 1 (5) | 10 (30) | 0.04 | 6 (15) | 23 (30) | 0.071 | 6 (13) | 36 (28) | 0.012 | 0 (0) | 20 (23) | 0.006 | 5 (20.8) | 15 (28.3) | 0.489 | 2 (5) | 5 (12) | ‐ | 0 | 2 (12) | 0.303 |

| Median pelvic lymph nodes, n | 13.7 | 19.3 | 0.052 | 27.2 | 33.9 | 0.079 | ‐ | ‐ | NS | ‐ | ‐ | NS | 23.5 | 22.8 | 0.867 | 26.8 | 27.8 | 0.721 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Median para‐aortic nodes, n | 8.9 | 6.4 | 0.187 | 6.6 | 8.8 | 0.324 | ‐ | ‐ | NS | ‐ | ‐ | NS | 9.9 | 4.8 | 0.003 | 17.7 | 21.2 | 0.202 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Omental specimen (cm³) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 160 | 274 | 0.113 | ‐ | ‐ | NS | ‐ | ‐ | NS | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Tumour size, mean (cm) | 4.0 | 4.5 | 0.618 | 8.9 | 11.0 | 0.254 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 9.1 | 14.0 | 0.010 | 7.3 | 11.2 | 0.001 | 6.69 | 11.50 | <0.05 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Complications n (%) | 0 (0) | 4 (21)¹ | ‐ | 2² | 9¹ | 0.290 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 6 (7.1) | 25 (19.5) | 0.013 | 2 | 20⁴ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 4 (11.43) | 5 (12.5) | NS | 0 | 1 (6) | 0 303 |

| Return to bowel movement (days) | 3.8 | 2.0 | < 0.001 | 1.3 | 3.6 | < 0.001 | 1.7 | 3.6 | < 0.001 | 1.8 | 3.1 | < 0.001 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 2.11 | 2.83 | <0.05 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Hospital stay (days) | 9.4 | 14.1 | 0.002 | 8.9 | 14.5 | 0.002 | 7.9 | 14.5 | 0.002 | 6.3 | 13.5 | < 0.001 | 6.4 | 12.4 | < 0.001 | 13.7 | 13.1 | 0.594 | 16.29 | 21.85 | <0.05 | 5 | 9 | <0.001 |

| Final diagnosis = stage I, n | 16 ³ | 13 | ‐ | 15 | 26 | 0.936 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 25 | 82 | 0.212 | 20 | 43 | ‐ | 30 | 33 | NS | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Intra‐operative tumour spillage, n (%) | 0 | 0 | ‐ | 2 | 4 | 1.000 | ‐ | ‐ | NS | ‐ | ‐ | NS | 0 | 13 (14.9) | 0.037 | 13 (54.2) | 21 (39.6) | 0.465 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy, n (%) | 10 (59) | 17 (89) | 0.196 | 15 (79) | 26 (79) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 17 (65.4) | 65 (74.7) | 0.453 | 21 (87.5) | 48 (90.6) | 0.48 | 30 (85.71) | 36 (90) | NS | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Time (days) to adjuvant chemotherapy | 11.1 | 14.3 | 0.140 | 12.8 | 17.6 | 0.049 | 12.8 | 13.9 | < 0.001 | 15.8 | 20.7 | < 0.001 | 8.5 | 10.3 | 0.007 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Upstaged, n (%) | 1 | 6 | 0.092 | 4 (21) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 6 (17.14) | 9 (22.50) | NS | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Conversion to LPT, n | 0 | NA | ‐ | 1 | NA | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 0 | ‐ | NA | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Port‐site/abdominal wound metastases | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 0 | 0 | ‐ | 0 | ‐ | NA | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Median follow‐up in months (range) | 19 (5 to 56) | 14 (5 to 61) | ‐ | 17 (2 to 40) | 23 (1 to 44) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 12 (1 to 42) | 25 (1 to 74) | ‐ | 31.7 (ND) | 31.1 (ND) | 0.9 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 53 (9‐84) | 45 (18‐84) | ‐ |

| PFS, n (%) | 15 ⁵(88) | 19 (100) | ‐ | 19 (100) | 33 (100) | ‐ | 37 (92) | 71 (93) | 0.876 | 66 (78) | 100 (78) | 0.873 | 26 (100) | 79 (91) | 0.195 | 22 (91.7) | 51 (96.2) | 0.585 | ‐ | ‐ | NS | 8 (80) | 7 (63.6) | 0.705 |

| OS, n (%) | 16 (94) | 19 (100) | ‐ | 19 (100) | 33 (100) | ‐ | 38 (96) | 71 (94) | 0.841 | 75 (89) | 110 (86) | 0.731 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 23 (95.8) | 53 (100) | NS | ‐ | ‐ | NS | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

Abbreviations: LPS = laparoscopy; LPT, laparotomy; BMI = body mass index; PFS = progression‐free survival; OS = overall survival; n = number; NA = not applicable; NS = not specified; ND = not described *Not included abstracts from conferences for lack of information **These studies are expansions of the original data set (Park 2008b) ¹Wound infections, fever, ileus ²Including one intra‐operative great vessel injury repaired via a small abdominal incision ³All these women were staged Ia/b compared with only five Ia/b and eight Ic cases in the LPT group ⁴Including 10 lymphoceles in the LPT group. Two umbilical hernias occurred in the LPS group ⁵One woman diagnosed as FIGO stage Ia grade 1 had severely disseminated disease 7 months postoperatively and died of the disease 15 months later. The other woman was stage Ia grade 2 at LPS and developed recurrence at the vaginal stump

We included in the second update of this analysis 4 meta‐analyses relevant for the subject in matter (Bogani 2014; Lu 2015; Park 2013; Zhang 2015) shown in Table 4.

4. Systematic reviews and meta analysis.

| Zhang 2015 | Park 2013 | Lu 2015 | Bogani 2014 | |||||

| P value | P value | P value | P value | |||||

| Number of studies | 8 | 11 | 11 | 6 | ||||

| OR length of hospital stay | 0.433 (0.215‐0.869) | 0.019 | ‐ | ‐4.87 (‐7.26, ‐2.47)** | <0.00001 | ‐3.30 (‐3.92, ‐2.69)** | <0.00001 | |

| OR recurrence rates | 0.707 (0.245‐2.037) | 0.521 | 0.099 (0.067‐0.144)* | <0.001 | 0.32 (0.13‐0.82) | 0.02 | 0.50 (0.21‐1.21) | 0.13 |

| OR of upstaging rates | ‐ | ‐ | 0.669 (0.246‐1.815) | 0.430 | ‐ | ‐ | 0.70 (0.38‐1.27) | 0.24 |

| OR intra‐operative complications | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 1.34 (0.37‐4.93) | 0.66 | 2.47 (0.50‐12.22) | 0.27 |

| OR postoperative complications | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 0.26 (0.13‐0.52) | 0.000 | 0.25 (0.12‐0.53) | 0.0003 |

| OR complications | 0.433 (0.215‐0.869) | 0.019 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

*Event rate

**Mean difference

Risk of bias in included studies

Not applicable.

Effects of interventions

There were no studies to include, therefore no meta‐analyses could be performed. Table 2 and Table 3 present the available data from the case‐control and retrospective studies to date as well as the relevant information from the four meta‐analyses.

Discussion

Stage I ovarian cancer is a rare disease and the use of laparoscopy for surgical staging is a relatively new field of clinical study, therefore data are scarce. UK guidelines on the management of ovarian cancer do not consider laparoscopy as an approach to the surgical staging of early ovarian cancer (NICE 2011); however, the German Gynaecological Oncology Group (AGO) have cautiously included the option of this procedure in their guidelines, for selected patients and only when performed by expert laparoscopic oncology surgeons, pending further evidence (Mettler 2009). The NCCN in its recent guidelines (NCCN 2016) suggest open laparotomy as the chosen surgical procedure for this pathology.

Summary of main results

We found no randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to include in this review and from which to compare the risks and benefits of laparoscopy with the conventional open approach. Existing non‐randomised evidence comparing these interventions is extremely limited and is particularly at risk of selection bias. We considered including case‐control non‐randomised studies (NRSs) in meta‐analyses, however sample sizes were small, none of these studies reported performing statistical adjustments for baseline case mix using multivariate analyses (e.g. age, final FIGO stage, grade, tumour size, co‐morbidity and adjuvant chemotherapy), the duration of follow‐up varied widely, and the primary outcomes of this review (overall survival (OS) and progression‐free survival (PFS)) were not consistently reported.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Survival

According to Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER; Kosary 2007), five‐year OS rates for stage Ia, Ib and Ic ovarian adenocarcinoma (excluding borderline tumours) are about 94%, 91% and 80%, respectively. However, survival data relating to the surgical approach (laparoscopy versus laparotomy) in the existing literature are extremely limited: comparative studies of laparoscopy versus laparotomy for early ovarian cancer to date include three case‐control studies (Table 2; Chi 2005; Ghezzi 2007; Hua 2005) and five retrospective cohort studies (Table 3; Lee 2011; Park 2008a; Park 2008b; Park 2010; Park 2011a), three of which are expansions of the same case series (Park 2008b; Park 2010; Park 2011a). Of these eight studies, six reported survival data but the length of follow‐up varied widely or was not reported. Lee 2011 reported higher PFS rates in the laparoscopy group (100% for laparoscopy versus 91% for laparotomy) and did not report OS, however median follow‐up was much shorter in the laparoscopy group compared with the laparotomy group (12 versus 25 months) and mean tumour size was significantly larger in the laparotomy group (P = 0.01). Park 2011a reported OS of 89% and 86% for laparoscopy and laparotomy, respectively and PFS rates of 78% in each group, but did not report the duration of follow‐up in each group. Ghezzi 2007 reported 100% OS in both groups, however the median duration of follow‐up differed substantially between the groups (16 months in the laparoscopy group compared with 60 months in the laparotomy group).

Two studies conducted in women with early ovarian cancer (Park 2008a; Wu 2010) have reported unfavourable survival outcomes with laparoscopy. In Park 2008a (OS = 88% in the laparoscopy group versus 100% in the laparotomy group; Table 3), one woman who was diagnosed with FIGO stage Ia grade 1 ovarian cancer was shown to have severely disseminated disease at seven months and died of the disease 15 months later; the other woman had stage Ia grade 2 ovarian cancer at laparoscopy and developed recurrence at the vaginal stump. The extent of laparoscopy surgical staging was considered sufficient in the latter case, the tumour was not ruptured and retrieval bags were used. Wu 2010 reported data from a cohort of women with stage 1 ovarian cancer treated between 1984 and 2006 and found that those in whom the initial surgical approach was laparoscopic had significantly worse PFS and OS than those who underwent laparotomy (OS hazard ratio (HR) = 3.52), however, comprehensive staging was not the purpose of the laparoscopy in most of these women, therefore these results are difficult to interpret. In general, we consider the available survival data to be of a very low quality, hence it is not possible draw any conclusions regarding the relative effect of laparoscopic surgical staging compared with laparotomy on ovarian cancer survival from the existing literature.

Feasibility

Measures of the technical feasibility of laparoscopy have included pelvic and para‐aortic lymph node yields, the size of the omental specimen, operating times and intra‐operative tumour spillage. All case‐control and cohort studies identified have reported statistically similar yields of retroperitoneal lymph nodes between their laparoscopy and laparotomy groups. Only two comparative studies (Chi 2005; Park 2008b) have reported mean omental specimen volumes, which were not statistically significantly different. With regard to operating times, some studies report significantly longer times with laparoscopy (Chi 2005; Ghezzi 2007; Hua 2005; Lee 2011), whilst others have reported significantly shorter times with laparoscopy (Park 2008b; Park 2010; Park 2011a). These differences probably reflect differences in surgeons' skills and laparoscopic techniques between investigator teams.

Rupture or spillage of ovarian tumours during surgery has been reported to occur more frequently with laparoscopy than laparotomy (Romagnolo 2006) and has been identified as a prognostic indicator of disease‐free survival (Vergote 2001). To date, six out of eight NRSs have compared rates of tumour spillage between laparoscopy and laparotomy groups (Hua 2005; Lee 2011; Park 2008a; Park 2008b; Park 2010; Park 2011a). Five of these studies reported no significant difference between the two groups, and one study (Lee 2011) reported a statistically significantly higher rate of spillage in the laparotomy group (0% versus 14.9%; P = 0.037), which also had a significantly larger mean tumour size compared with the laparoscopy group. The definitions of spillage vary and the distinction between tumour rupture and puncture is not detailed in most studies (Ghezzi 2009). To properly assess these outcomes, technique and definitions need to be clearly defined in future studies. However, these limited data suggest that laparoscopy staging of early ovarian cancer is technically feasible when performed by experienced laparoscopic gynaecology oncology surgeons.

An inherent shortcoming of laparoscopy for surgical staging is the inability to palpate lymph nodes and other peritoneal surfaces (Colomer 2008; Park 2008a), however Chi 2010 argues that intra‐operative direct visualisation and evaluation of nodes by palpation is inherently subjective. In a recent prospective study of 111 women with apparent early ovarian cancer who underwent comprehensive staging by laparotomy that included retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RLND), retroperitoneal nodal metastases were present in 13.5% of the women (Ditto 2012), which suggests that without RLND many women would be under‐staged. However, systematic RLND may be associated with significant morbidity and is not a routine part of staging for early ovarian cancer in the UK, where clinical guidelines currently recommend retroperitoneal lymph node assessment with sampling of suspicious nodes (NICE 2011). Therefore, where RLND is not routine, lymph node palpation may play a crucial role in the decision‐making process with regard to sampling. Another technically difficult part of the surgical staging procedure is the examination of the diaphragmatic peritoneum behind the liver and spleen and the dome of the liver (Park 2008a); this may be more difficult with laparoscopy, although it has been argued that isolated metastases to these areas are rare (Ghezzi 2009).

Safety

Surgical staging for ovarian cancer is a radical procedure that may be associated with severe intra‐operative vascular, nerve, lymphatic, bowel and urinary tract complications. Common postoperative complications include wound infection, ileus, febrile morbidity and lymphoceles (Ghezzi 2007; Lee 2011; Park 2008a; Park 2008b). Three comparative studies in early ovarian cancer have reported significantly fewer postoperative complications with laparoscopy compared with laparotomy (Hua 2005; Lee 2011; Park 2011a). The following complications have been reported in the laparoscopy participants of studies in early ovarian cancer: umbilical hernias (Lee 2011), retroperitoneal haematoma (Ghezzi 2007), vascular injury (Colomer 2008; Ghezzi 2007; Park 2008b), lymphoceles (Lee 2011; Nezhat 2009), obturator nerve damage (Hua 2005), bowel injury or obstruction (Nezhat 2009; Park 2008a) and ureter injury (Park 2008b). Estimated blood loss (EBL) in all case‐control (Table 2) and comparative cohort studies (Table 3) has been statistically significantly less than in the laparoscopy groups compared with laparotomy groups, with the exception of one study (Ghezzi 2007). In these studies, rates of blood transfusion in laparoscopy groups ranged from 0% to 15%, whereas transfusions were necessary in up to 30% (Park 2010) of women who underwent laparotomy.

There have been several reports of the occurrence of abdominal wall metastases following laparoscopy for ovarian cancer (Childers 1994; Gleeson 1993; Leminen 1999). However, in the studies of laparoscopy in stage I ovarian cancer that have reported this outcome, no port‐site metastases had occurred by the time of reporting in Chi 2005 (20 women), Park 2008a (17 women), Park 2008b (19 women), Nezhat 2009 (36 women) and Lee 2011 (26 women). Port‐site metastases may be technique‐related and limited mostly to patients with advanced disease (Chi 2005; Nezhat 2009). In a study of laparoscopic cytoreductive surgery for advanced ovarian cancer and in which no port‐site metastases occurred, the authors attributed their results to a surgical technique that employed endoscopic bags to retrieve intact specimens and a layered closure of the trocar site (Nezhat 2010). Lee 2011 and Chi 2005 have also reported employing this technique to prevent port‐site metastases.

Other outcomes

Lee 2011 evaluated the relative cost of laparoscopy compared with open surgery in women with early ovarian cancer and found that laparoscopy resulted in higher costs due to the cost of disposable instrumentation and direct material/operating room costs, but the cost of hospital stay was higher in the laparotomy group because the stay was longer. Where bed costs are higher, this difference in cost might be eliminated, however the median lengths of hospital stay in the laparotomy groups in most of the studies reporting this outcome seem excessive with a range of up to 14.5 days (Table 2; Table 3). Literature on the quality of life for women undergoing laparoscopy compared with laparotomy is scant, however Lee 2011 reported significantly lower postoperative pain scores in the laparoscopy group.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

A meta‐analysis of eight RCTs comparing laparoscopic surgical staging with laparotomy for endometrial cancer has shown the laparoscopic approach to be safe, with statistically significantly fewer postoperative complications than laparotomy, and similar rates of intra‐operative complications (Zullo 2012). It is possible that similar conclusions may, in time, be drawn about laparoscopy and laparotomy for stage I ovarian cancer, however the evidence for this is not currently in the literature.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Due to technological advancements in instrumentation and an increase in laparoscopic surgical expertise, the role of laparoscopy in gynaecological cancers is expanding, however there is still wide regional variation in the laparoscopic skills and competence of gynaecological‐oncology surgeons. We did not find any good evidence to recommend laparoscopy for the routine management of women with stage I ovarian cancer.

Implications for research.

Survival data for patients with gynaecological malignancies managed by laparoscopy are still lacking. A major barrier to conducting randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in early ovarian cancer is the anticipated difficulty in recruiting sufficient numbers of participants (Ghezzi 2009). Other difficulties include standardising the quality of the surgery and the skill of the surgeons. Subsequent results from such trials may only be applicable to expert laparoscopic oncology surgeons. However, we understand, from a personal communication, that the Korean Gynecologic Oncology Group (KGOG) is currently developing a protocol for a RCT comparing laparoscopy with laparotomy for early ovarian cancer. Two recently reported Korean cohort studies (Lee 2011; Park 2011a) recruited 325 women between them within the same six‐year period (2004 to 2010), suggesting that a multicentre RCT is feasible. Participating institutions should be subgrouped according to whether retroperitoneal lymph node dissection or lymph node assessment with sampling is performed routinely. Outcomes of RCTs should include overall and progression‐free survival, complications (intra‐operative and postoperative), the use of adjuvant chemotherapy, patient satisfaction, quality of life and costs. It would be helpful if costs are reported separately for the preoperative, intra‐operative and postoperative periods.

Feedback

Definition of studies, June 2015

Summary

Name: Alexander Melamed

Comment: The term "prospective case‐control" is used in this study is confusing. Case‐control studies by definition are retrospective. A case‐control study is one where patients with and without an outcome of interest are identified, and the presence or absence of a putative causal exposure is investigated among these "cases" and "controls." Perhaps what the authors of this study are referring to is what would conventionally be called a cohort study. For a useful discussion of the confusion in regarding the terminology please see Marshall T. What is a case‐control study? International Journal of Epidemiology 2004;33:612–617.

I agree with the conflict of interest statement below:

I certify that I have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with a financial interest in the subject matter of my feedback.

Reply

The authors would like to thank Dr Melamed for taking the time to write, and we accept his suggestion. We have amended the term prospective case‐control to prospective cohort studies throughout the review.

Contributors

Theresa A Lawrie on behalf of the author team.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 6 January 2022 | Amended | No longer for update as any future update will require the development of a new protocol reflecting current Cochrane methodological criteria. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2005 Review first published: Issue 4, 2008

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 17 November 2016 | Amended | Minor copy‐edit changes |

| 17 October 2016 | Amended | Additional author affiliations added. |

| 9 September 2016 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | No studies identified for inclusion. |

| 7 September 2016 | New search has been performed | Literature searches updated September 2016. |

| 16 June 2015 | Feedback has been incorporated | Feedback received and responded too. |

| 12 September 2012 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Eleven newly identified studies excluded, no studies included. Conclusions unchanged. |

| 30 November 2011 | New search has been performed | Search updated. |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jo Morrison, Gail Quinn, Clare Jess and Tracey Bishop of the Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Review Group team that is based at the Royal United Hospital, Bath, UK for their help, advice and support throughout the review process; Jane Hayes for performing the updated search; and the library staff at the Royal United Hospital, Bath, UK, who obtained many articles for us. We would also like to thank Lidia Medieros for acting as the contact author on the original review.

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to the Cochrane Gynaecological, Neuro‐oncology and Orphan Cancer Group. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor Ovarian Neoplasms explode all trees #2 ovar* near/5 (cancer* or tumor* or tumour* or neoplas* or carcinoma* or malignan* or adenocarcinoma*) #3 (#1 OR #2) #4 MeSH descriptor Laparoscopy explode all trees #5 laparoscop* or celioscop* or peritoneoscop* or (endoscop* near/5 abdom*) #6 MeSH descriptor Laparotomy, this term only #7 laparotom* or (abdom* near/5 (surg* or incision)) #8 (#4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7) #9 (#3 AND #8)

Appendix 2. MEDLINE search strategy

1 exp Ovarian Neoplasms/ 2 (ovar* adj5 (cancer* or tumor* or tumour* or neoplas* or carcinoma* or malignan* or adenocarcinoma*)).mp. 3 1 or 2 4 exp laparoscopy/ 5 (laparoscop* or celioscop* or peritoneoscop* or (endoscop* adj5 abdom*)).mp. 6 Laparotomy/ 7 (laparotom* or (abdom* adj5 (surg* or incision))).mp. 8 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 9 3 and 8 10 randomized controlled trial.pt. 11 controlled clinical trial.pt. 12 randomized.ab. 13 placebo.ab. 14 clinical trials as topic.sh. 15 randomly.ab. 16 trial.ti. 17 exp cohort studies/ 18 exp case‐control studies/ 19 comparative study/ 20 (cohort* or prospective* or retrospective* or control* or longitudinal or follow‐up).mp. 21 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 22 9 and 21

key: [mp = protocol supplementary concept, rare disease supplementary concept, title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word, unique identifier]

Appendix 3. Embase search strategy

1 exp ovary tumor/ 2 (ovar* adj3 (cancer* or tumor* or tumour* or neoplas* or carcinoma* or malignan* or adenocarcinoma*)).ti,ab. 3 1 or 2 4 laparoscopy/ 5 (laparoscop* or celioscop* or peritoneoscop* or (endoscop* adj3 abdom*)).ti,ab. 6 laparotomy/ 7 (laparotom* or (abdom* adj3 (surg* or incision))).ti,ab. 8 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 9 exp controlled clinical trial/ 10 cohort analysis/ 11 exp case control study/ 12 exp comparative study/ 13 (randomized or randomly or trial* or cohort* or prospective* or retrospective* or control* or longitudinal or follow‐up).ti,ab. 14 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 15 3 and 8 and 14

key: [mp = title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword]

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Amara 1996 | A case series of 11 women with stage Ia to IIIc ovarian cancer who underwent laparoscopy staging |

| Bae 2014 | A retrospective cohort study of laparoscopy (minimally invasive surgical approach) in 89 women with early ovarian cancer versus 105 women who underwent open surgery. There was no difference in progression‐free survival or overall survival. |

| Berman 2003 | Narrative review |

| Bogani 2014 | Case series with historical controls followed by a systematic review and meta‐analysis. The conclusion was that patients in the laparoscopy group had lower blood loss, shorter length of hospital stay, and shorter time gap between surgery and chemotherapy, although they had longer operative time (see Table 2 and Table 4) |

| Bristow 2000 | Narrative review |

| Brockbank 2013 | A case series of 35 women who underwent laparoscopic surgical staging for apparent early ovarian cancer |

| Canis 1994 | Narrative review |

| Canis 1997 | A case series of 10 cases of laparoscopy for low malignant potential tumour and 15 cases of cancer, but stage not described |

| Canis 2000 | A series of laparoscopy for 28 cases of cancer and borderline tumour; stage not described |

| Chapron 1998 | Narrative review |

| Chen 2010 | A case series of 43 women who underwent laparoscopic surgical staging for apparent early ovarian cancer (see Table 1) |

| Chi 2005 | A retrospective case‐control study of 50 women who underwent laparoscopic or open surgical staging for apparent early ovarian cancer (see Table 2) |

| Childers 1995 | A prospective case series of second‐look laparoscopy to evaluate both intraperitoneal cavity and retroperitoneal lymph nodes and laparoscopic surgical staging. 14 women underwent laparoscopic staging of apparent early ovarian cancer; metastatic disease was discovered in 8 of these women (see Table 1). |

| Childers 1996 | A series of 138 cases of laparoscopy for suspicious ovarian masses (not surgical staging). Malignancies were discovered in 19 women. |

| Colomer 2008 | A prospective case series of laparoscopic surgical staging of 20 women with apparent early ovarian cancer (18 EOCs and 2 dysgerminomas) (see Table 1) |

| Covens 2012 | A systematic review of the surgical management of suspicious adnexal mass. Included patients with suspicious early stage disease (stage I‐II) as well as studies about frozen section diagnosis |

| Darai 1998 | A retrospective case series of 25 women with borderline ovarian tumours |

| de Poncheville 2001 | Retrospective study of surgery without para‐aortic lymphadenectomy in stage I ovarian cancer. Investigators advocate surgery without lymphadenectomy for women with early ovarian cancer. |

| Ditto 2014 | Case‐control study comparing fertility sparing surgery open or laparoscopic (n = 18) with radical surgery (n = 18). The authors concluded that fertility‐sparing surgery in patients submitted to a comprehensive surgical staging yielded results similar to radical surgery. |

| Ditto 2015 | Case‐control study comparing laparoscopic (n = 37) with open surgery (n = 37) in patients with apparent early ovarian cancer (results in Table 2) |

| Dottino 1999 | Retrospective case series of 94 laparoscopic lymphadenectomies for gynaecological malignancies, including 14 women with ovarian cancer |

| Gallotta 2016 | Case‐control study comparing laparoscopic (n = 60) with laparotomic surgery (n = 120) in patients with apparent early ovarian cancer (results in Table 2) |

| Ghezzi 2007 | A case‐control study of 15 women who underwent laparoscopic staging for early ovarian cancer versus 19 historical controls who had open surgery (see Table 2) |

| Ghezzi 2009 | A case series of 26 women who underwent laparoscopic staging for early ovarian cancer (see Table 1) |

| Goff 2006 | Narrative review |

| Hong 2011 | A case series of 35 laparoscopic versus laparotomy (see Table 3) for second look operations for ovarian cancer (see Table 3) |

| Hua 2005 | A small, prospective, case‐control study of 10 women who underwent laparoscopic staging for early ovarian cancer versus 11 women who underwent laparotomy (see Table 2). No adjustments were made for baseline case mix. |

| Iglesias 2011 | Narrative review |

| Kadar 1995 | Included other cancers (endometrial, cervical, ovarian) |

| Kim 2014 | Retrospective case series of 113 laparoscopic versus laparotomy. Mean operation time longer for the laparoscopy group (not statistically significant), however the laparoscopy group had less blood loss, shorter time to adjuvant chemotherapy, lower operative complications, and shorter hospital stay (see Table 1). |

| Klindermann 1995 | A survey conducted on laparoscopy in Germany |

| Kobal 2013 | Retrospective case series of 28 laparoscopic versus laparotomy |

| Koo 2012 | A retrospective case series of 262 pregnant women who underwent laparotomy (n = 174) or laparoscopic surgery (88) for adnexal masses. |

| Koo 2014 | Retrospective case series of 77 laparoscopic versus laparotomy for early stage ovarian cancer (stage I to II) (see Table 3) |

| Leblanc 2004 | Cohort with other types of cancer (fallopian tube carcinoma) and in patients that were inadequately staged at the time of initial surgery for invasive ovarian carcinoma |

| Leblanc 2006 | Narrative review |

| Leblanc 2014 | Retrospective case series of laparoscopic staging paraaortic lymph node dissection (PALND) by two routes (extraperitoneal and transperitoneal) for gynaecologic cancers compared with laparotomic PALND. The author concluded that laparoscopic PALND is safe and the preferred approach is extraperitoneal since it yielded more lymph nodes compared with the transperitoneal approach. |

| Lécuru 2004 | Retrospective study of 105 women who underwent surgery for stage I ovarian cancer. 14 underwent laparoscopy only, 13 had a laparoscopy converted to laparotomy and 78 had a laparotomy. Comprehensive staging was less frequent in the laparoscopy group. |

| Lee 2011 | A retrospective cohort study of laparoscopy in 26 women with early ovarian cancer versus 87 women who underwent open surgery (see Table 3). No adjustments were made for baseline case mix. Women in the laparotomy group had significantly larger tumours and longer follow‐up. |

| Liu 2014 | Retrospective case series of 75 patients that underwent laparoscopy (35 patients) or laparotomy (40 patients) surgery for early ovarian cancer (stage I ‐ II)(see Table 3) |

| Lu 2014 | Retrospective case series of 92 patients that underwent laparoscopy vs laparotomy surgery for early ovarian cancer (stage I to II) |

| Lu 2015 | A systematic review and meta‐analysis of the surgical management of early ovarian cancer. Included non‐randomised studies with a total of 591 patients. The authors concluded that the laparoscopic approach is associated with less intraoperative blood loss, lower postoperative complication rates, shorter postoperative hospital stays, and lower postoperative recurrence rates. There were no significant differences mortality, operative time, and number of lymph node harvested. |

| Maiman 1991 | Members and candidate members of the Society of Gynecologic Oncologists responded to a survey concerning the "laparoscopy management of ovarian neoplasm subsequently found be malignant" |

| Malik 1998 | Unexpected ovarian tumours were discovered in 11/292 women who underwent laparoscopy to evaluate adnexal masses |

| Maneo 2004 | Criteria for exclusion: 62 patients had fertility‐sparing after surgery |

| Manolitsas 2001 | Narrative review |

| Mehra 2004 | A prospective case series of 32 women with ovarian and other gynaecological cancers who underwent laparoscopic retroperitoneal para‐aortic lymphadenectomy |

| Meinhold‐Heerlein 2014 | Narrative review |

| Minig 2015 | Case‐control study comparing laparoscopic (n = 50) with open surgery (n = 58) in patients with apparent early ovarian cancer (results in Table 2) |

| Montanari 2013 | Series of cases |

| Moon 2012 | Series of cases (see Table 1) |

| Nakayama 2015 | Retrospective study comparing laparoscopy versus laparotomy for the treatment stage I ‐ IV granulosa cell tumours |

| Nezhat 1992 | A case series |

| Nezhat 2009 | A case series of 36 women with early ovarian cancer who underwent complete laparoscopic staging (see Table 1) |

| Nezhat 2010 | A case series of women with advanced ovarian cancer who underwent complete laparoscopic staging |

| Palomba 2010 | Long‐term follow‐up of a randomised controlled trial comparing ultra‐conservative fertility sparing surgery (bilateral cystectomy) with oophorectomy plus contra‐lateral cystectomy in patients with bilateral borderline ovarian tumours |

| Park 2008a | A retrospective cohort study of 17 versus 19 women with early ovarian cancer who underwent laparoscopic staging and laparotomy respectively (see Table 3). No adjustments were made for baseline case mix. |

| Park 2008b | A retrospective cohort study of 19 versus 33 women with early ovarian cancer who underwent laparoscopic staging and laparotomy respectively (see Table 3) |

| Park 2010 | An expansion of the earlier study (Park 2008b; see Table 3) |

| Park 2011a | An expansion of Park 2008b and Park 2010 retrospective studies (see Table 3) |

| Park 2011b | The same report as Park 2011a |

| Park 2013 | A systematic review and meta‐analysis of retrospective and observational studies of laparotomy versus laparoscopy in early ovarian cancer. The authors concluded that the overall incidence of conversion from laparoscopy to laparotomy was 3.7% the overall rate of recurrence in studies with a median follow‐up period of 19 months was 9.9% |

| Parker 1990 | This study only included women with benign ovarian cysts |

| Poilblanc 2012 | Narrative review |

| Pomel 1995 | A series of women with stage I ovarian carcinoma who underwent a laparoscopic procedure to complete their staging |

| Querleu 2003 | A retrospective study of laparoscopic restaging of 30 women with borderline ovarian tumours |

| Querleu 2006a | Narrative review |

| Querleu 2006b | Many types of tumours (cervical, vaginal, endometrial and ovarian carcinoma) |

| Reich 1990 | A case report |

| Romagnolo 2006 | A case series where laparoscopy was performed for suspected borderline ovarian tumours, and included fertility‐sparing procedures |

| Rouzier 2005 | Narrative review |

| Satoh 2015 | Protocol description for fertility‐sparing surgery |

| Solima 2011 | A retrospective study designed to evaluate the learning curve of para‐aortic lymphadenectomy by laparoscopy and laparotomy in the setting of endometrial and early ovarian cancer |

| Spirtos 2005 | A case series of laparoscopy for all stages of ovarian cancer and other types of cancers |

| Tozzi 2004 | A case series of laparoscopic staging for early ovarian cancer (see Table 1) |

| Tozzi 2005 | Narrative review |

| Trillsch 2013 | Retrospective case series of 105 patients that underwent laparoscopy (44 patients) or laparotomy surgery (61 patients) for borderline ovarian tumours |

| Tropé 2006 | Narrative review |

| Vaisbuch 2005 | Narrative review |

| Vergote 2003 | Narrative review |

| Vinatier 1996 | Narrative review |

| Vizza 2012 | Abstract with narrative review |

| Volz 1997 | Narrative review |

| Wenzl 1996 | A questionnaire was sent to all 97 Departments of Gynaecology in Austria to determine the frequency of discovering a malignant ovarian mass when laparoscopy is used to manage an adnexal mass |

| Wu 2010 | A retrospective cohort study of laparoscopy versus laparotomy, however surgical staging was not always the aim of the initial laparoscopy |

| Yoon 2011 | A case series 38 ovarian cancer patients. Seven cases (18%) were converted to conventional laparotomy |

| Zhang 2015 | A systematic review and meta‐analysis of laparotomy versus laparoscopy in early ovarian cancer. Included non‐randomised studies. The authors found that laparoscopic surgery was associated with lower rates of complications and shorter postoperative hospital stays and no difference in the rates of recurrence (see Table 4). |

EOC = epithelial ovarian cancer

Differences between protocol and review

For the original review (Medeiros 2008), we included non‐randomised studies (NRSs) and evaluated the quality of three studies (Ghezzi 2007; Hua 2005; Tozzi 2004) according to the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) and NOS tools. For the updated review, these studies were excluded, but we tabulated and discussed the data with other NRSs.

Contributions of authors

Lidia Medieros (LM), Daniela Rosa (DR), Mary Bozetti (MB), Maria Ines Rosa (MR), Alice Zelmanowicz (AZ) and Airton Stein (AS) contributed to the writing of the protocol and the original review. LM, DR, MR, MB and Maria Edelweiss sifted the searches, selected studies and extracted data for the original review (which included NRSs). Anaelena Ethur (AE) and Roselaine Zanini (RZ) contributed to the protocol and methods section. Tess Lawrie (TL) sifted the updated search and wrote the first draft of the updated review. Frederico Falcetta (FF) and DR wrote the draft of the second update of the review. All authors approved the final version.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support provided

External sources

-

National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), UK

This review received methodological, statistical and editorial support as part of the 10/4001/12 NIHR Cochrane Programme Grant Scheme: Optimising care, diagnosis and treatment pathways to ensure cost effectiveness and best practice in gynaecological cancer: improving evidence for the NHS.

Declarations of interest

None.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies excluded from this review

Amara 1996 {published data only}

- Amara DP, Nezhat C, Teng N, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, Rosati M. Operative laparoscopy in the management of ovarian cancer. Surgical Laparoscopy and Endoscopy 1996;6(1):38-45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bae 2014 {published data only}

- Bae SY, Lee YY, Kim TJ, Choi JK, Kim TH, Yun G, et al. Analysis of recurrence pattern based on minimally invasive approach in patients with stage I epithelial ovarian cancer. In: International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. Conference: 15th Biennial Meeting of the International Gynecologic Cancer Society Melbourne, VIC Australia edition. Vol. 24, supplement 4. 2014:203-204.

Berman 2003 {published data only}

- Berman ML. Future directions in the surgical management of ovarian cancer. Gynecologic Oncology 2003;90(2):S33-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bogani 2014 {published data only}

- Bogani G, Cromi A, Serati M, Di Naro E, Casarin J, Pinelli C, et al. Laparoscopic and open abdominal staging for early-stage ovarian cancer: our experience, systematic review, and meta-analysis of comparative studies. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer 2014;24(7):1241-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bristow 2000 {published data only}

- Bristow RE. Surgical standards in management of ovarian cancer. Current Opinion in Oncology 2000;12:474-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brockbank 2013 {published data only}

- Brockbank EC, Harry V, Kolomainen D, Mukhopadhyay D, Sohaib A, Bridges JE, et al. Laparoscopic staging for apparent early stage ovarian or fallopian tube cancer. First case series from a UK cancer centre and systematic literature review. European Journal of Surgical Oncology 2013;39(8):912-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Canis 1994 {published data only}

- Canis M, Mage G, Pouly JL, Wattiez A, Manhes H, Bruhat MA. Laparoscopic diagnosis of adnexal cystic masses: a 12 year experience with long term follow up. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1994;83(5):707-12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Canis 1997 {published data only}

- Canis M, Pouly JL, Wattiez, Mage G, Manhes H, Bruhat A. Laparoscopic management of adnexal masses suspicious at ultrasound. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1997;89(5):679-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Canis 2000 {published data only}

- Canis M, Mage G, Wattiez A, Pouly JL, Sonteara SS, Bruhat MA. A simple management program for adnexal masses. Gynecologic Oncology 2000;7:113-8. [Google Scholar]

Chapron 1998 {published data only}

- Chapron C, Dubuisson JB, Kadadoch O, Capela-Allouc. Laparoscopic management of organic ovarian cysts: is there a place for frozen section diagnosis? Human Reproduction 1998;13:324-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chen 2010 {published data only}

- Chen Y. Laparoscopic comprehensive staging for apparent early invasive epithelial ovarian cancers: surgical and outcome. In: Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology; 39th Global Congress of Minimally Invasive Gynecology, Las Vegas, NV United States. Vol. 17(6). 2010:S44.

Chi 2005 {published data only}

- Chi D, Abu-Rustum NR, Sonoda Y, Ivy J, Rhee E, Moore K, et al. The safety and efficacy of laparoscopic surgical staging of apparent stage I ovarian and fallopian tube cancers. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2005;192:1614-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Childers 1995 {published data only}

- Childers JM, Lang J, Surwit EA, Hatch K. Laparoscopic surgical staging of ovarian cancer. Gynecologic Oncology 1995;59:25-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Childers 1996 {published data only}

- Childers JM, Nasseri A, Surwit EA. Laparoscopic management of suspicious adnexal masses. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1996;175(6):1451-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Colomer 2008 {published data only}

- Colomer AT, Jimenez AM, Bover Barcelo MI. Laparoscopic treatment and staging of early ovarian cancer. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology 2008;15(4):414-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Covens 2012 {published data only}

- Covens AL, Dodge JE, Lacchetti C, Elit LM, Le T, Devries-Aboud M, et al. Surgical management of a suspicious adnexal mass: a systematic review. Gynecologic Oncology 2012;126(1):149-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Darai 1998 {published data only}

- Darai E, Teboul J, Fauconnier A, Scoazec JY, Benifla JL, Madelenat P. Management and outcome of borderline ovarian tumors incidentally discovered at or after laparoscopy. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 1998;77:451-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

de Poncheville 2001 {published data only}

- Poncheville L, Perrrotin F, Lefrancq T, Lansac J, Body G. Does paraaortic lymphadenectomy have a benefit in the treatment of ovarian cancer that is apparently confined to the ovaries? European Journal of Cancer 2001;37:210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ditto 2014 {published data only}

- Ditto A, Martinelli F, Lorusso D, Haeusler E, Carcangiu M, Raspagliesi F. Fertility sparing surgery in early stage epithelial ovarian cancer. Journal of Gynecologic Oncology 2014;25(4):320-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ditto 2015 {published data only}

- Ditto A, Bogani G, Martinelli F, Lorusso D, Chiappa V, Daniele A, Perotto S, Raspagliesi F. Laparoscopic surgical staging for apparent early stage ovarian cancer: A propensity-matched comparison with open surgical staging. In: International Jjournal of Gynecological Cancer. Conference: 19th International Meeting of the European Society of Gynaecological Oncology, ESGO 2015 Nice France edition. Vol. 25. 2015:428.

Dottino 1999 {published data only}

- Dottino PR, Levine DA, Ripley DL, Cohen CJ. Laparoscopic management of adnexal masses in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1999;93(2):223-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gallotta 2016 {published data only}

- Gallotta V, Petrillo M, Conte C, Vizzielli G, Fagotti A, Ferrandina G, et al. Laparoscopic versus laparotomic surgical staging for early-stage ovarian cancer: a case-control study. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology 2016;23(5):769-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ghezzi 2007 {published data only}

- Ghezzi F, Cromi A, Uccella S, Bergamini V, Tomera S, Franchi M, et al. Laparoscopy versus laparotomy for the surgical management of apparent early stage ovarian cancer. Gynecologic Oncology 2007;105(2):409-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ghezzi 2009 {published data only}

- Ghezzi F, Cromi A, Siesto G, Serati M, Zaffaroni E, Bolis P. Laparoscopy staging of early ovarian cancer. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer 2009;19:S7-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Goff 2006 {published data only}

- Goff BA, Matthews BJ, Wynn M, Muntz HG, Lisher DM, Baldwin LM. Ovarian cancer: patterns of surgical care across the United States. Gynecologic Oncology 2006;103:383-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hong 2011 {published data only}

- Hong DG, Park NY, Chong GO, Cho YL, Park IS, Lee YS. Laparoscopic second look operation for ovarian cancer: single center experiences. Minimally Invasive Therapy & Allied Technologies: MITAT 2011;20(6):346-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hua 2005 {published data only}

- Hua KQ, Jin FM, Xu F, Zhu ZL, Lin JF, Feng YJ. Evaluations of laparoscopic surgery in the early stage malignant tumor of ovary with lower risk. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2005;85(3):169-72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Iglesias 2011 {published data only}

- Iglesias DA, Ramirez PT. Role of minimally invasive surgery in staging of ovarian cancer. Current Treatment Options in Oncology 2011;12(3):217-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kadar 1995 {published data only}

- Kadar N. Laparoscopic surgery for gynaecological malignancies in women aged 65 years or more. Gynaecological Endoscopy 1995;4:173-6. [Google Scholar]

Kim 2014 {published data only}

- Kim S, Nam EJ, Lee BS. Comparisons of surgical outcomes, complications,and costs between laparotomy and laparoscopy in early-stage ovarian cancer. In: Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology. Conference: 43rd Global Congress of Minimally Invasive Gynecology, AAGL 2014 Vancouver, BC Canada edition. Vol. 21. 2014:S191. [DOI] [PubMed]

Klindermann 1995 {published data only}

- Klindermann G, Maassen V, Kuhn W. Laparoscopic preliminary surgery of ovarian malignancies. Experiences from 127 German gynecologic clinics. Gerburtshilfe Frauenheikd 1995;55(12):687-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kobal 2013 {published data only}

- Kobal B, Branko C, Matija B, Leon M, Marina J. Complete laparoscopic surgical management of early stage ovarian cancer compared to standard laparotomy surgical management. In: Gynecological Surgery. Conference: 22nd Annual Congress of the European Society of Gynaecological Endoscopy, ESGE 2013 Berlin Germany edition. Vol. 10, supplement 1. 2013:S32.

Koo 2012 {published data only}

- Koo YJ, Kim HJ, Lim KT, Lee IH, Lee KH, Shim JU, et al. Laparotomy versus laparoscopy for the treatment of adnexal masses during pregnancy. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2012;52(1):34-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Koo 2014 {published data only}

- Koo Y-J, Kim J-E, Kim Y-H, Hahn H-S, Lee I-H, Kim T-J, et al. Comparison of laparoscopy and laparotomy for the management of early-stage ovarian cancer: Surgical and oncological outcomes. Journal of Gynecologic Oncology 2014;25(2):111-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Leblanc 2004 {published data only}

- Leblanc E, Querleu D, Narducci F, Occelli B, Papageorgiou T, Sonada Y. Laparoscopic restaging of early stage invasive adnexal tumors: a 10 year experience. Gynecologic Oncology 2004;94(3):624-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Leblanc 2006 {published data only}

- Leblanc E, Sonoda Y, Narducci F, Ferron G, Querleu D. Laparoscopic staging of early ovarian carcinoma. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology 2006;18:407-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Leblanc 2014 {published data only}

- Leblanc E, Narducci F, Bresson L, Merlot B, Querleu D. Laparoscopic paraaortic lymph node dissection (PALND) : Results of a 22-year single center experience, with comparative study of different approaches and patterns of dissection. In: International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. Conference: 15th Biennial Meeting of the International Gynecologic Cancer Society Melbourne, VIC Australia edition. Vol. 24, supplement 4. 2014:1233.

Lécuru 2004 {published data only}

- Lécuru F, Desfeux P, Camatte S, Bissery A, Robin F, Blanc B. Stage I ovarian cancer: comparison of laparoscopy and laparotomy on staging and survival. European Journal of Gynaecological Oncology 2004;25:571-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lee 2011 {published data only}

- Lee M, Kim SW, Lee SH, Yim GW, Kim JH, Kim JW, et al. Comparisons of surgical outcomes, complications, and costs between laparotomy and laparoscopy in early-stage ovarian cancer. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer 2011;21(2):251-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Liu 2014 {published data only}

- Liu M, Li L, He Y, Peng D, Wang X, Chen W, et al. Comparison of laparoscopy and laparotomy in the surgical management of early-stage ovarian cancer. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer 2014;24(2):352-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lu 2014 {published data only}

- Lu Q, Zhang Z, Liu C. Comparison of laparoscopy and laparotomy staging of early-stage ovarian cancer: A study with 12-year experience. In: Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology. Conference: 43rd Global Congress of Minimally Invasive Gynecology, AAGL 2014 Vancouver, BC Canada edition. Vol. 21. 2014:S16.

Lu 2015 {published data only}

- Lu Y, Yao D-S, Xu J-H. Systematic review of laparoscopic comprehensive staging surgery in early stage ovarian cancer: A meta-analysis. Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 2015;54(1):29-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Maiman 1991 {published data only}

- Maiman M, Seltzer V, Boyce J. Laparoscopic excision of ovarian neoplasms subsequently found to be malignant. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1991;77:563-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Malik 1998 {published data only}

- Malik E, Böhm W, Stoz F, Nitsch D, Rossmanith WG. Laparoscopic management of ovarian tumors. Surgical Oncology 1998;12:1326-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Maneo 2004 {published data only}

- Maneo A, Vignali M, Chiari S, Colombo A, Mangioni C, Landoni F. Are borderline tumors of the ovary safely treated by laparoscopy? Gynecologic Oncology 2004;94:387-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Manolitsas 2001 {published data only}

- Manolitsas T, Fowler JM. Role of laparoscopy in the management of the adnexal mass and staging of gynecologic cancers. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 2001;44(3):495-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mehra 2004 {published data only}

- Mehra G, Weekes ARL, Jacobs IJ, Visvanathan D, Menon U, Jeyarajah AR. Laparoscopy extraperitoneal paraaortic lymphadenectomy a study of its applications in gynecological malignancies. Gynecologic Oncology 2004;93:189-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Meinhold‐Heerlein 2014 {published data only}

- Meinhold-Heerlein I, Papathemelis T, Wolfler M, Maass N. Laparoscopy in gynecological oncology. Der Gynakologe 2014;47(3):165-71. [Google Scholar]

Minig 2015 {published data only}

- Minig L, Saadi JM, Patrono MG, Giavedini ME, Cardenas-Rebollo JM, Perrota M. Perioperative and oncological outcomes of laparoscopic versus open surgical staging in women with early stage epithelial ovarian cancer. In: International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. Conference: 19th International Meeting of the European Society of Gynaecological Oncology, ESGO 2015 Nice France edition. Vol. 25. 2015:77-81.

Montanari 2013 {published data only}

- Montanari G, Di Donato N, Del Forno S, Benfenati A, Bertoldo V, Vincenzi C, et al. Laparoscopic management of early stage ovarian cancer: is it feasible, safe, and adequate? A retrospective study. European journal of Gynaecological Oncology 2013;34(5):415-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moon 2012 {published data only}