Abstract

Background

Active management of the third stage of labour (AMTSL) consists of a group of interventions, including administration of a prophylactic uterotonic (at at or after delivery of the baby), baby, cord clamping and cutting, controlled cord traction (CCT) to deliver the placenta, and uterine massage. Recent recommendations are to delay cord clamping until the caregiver is ready to initiate CCT. The package of AMTSL reduces the risk of postpartum haemorrhage, (PPH), as does one component, routine use of uterotonics. The contribution, if any, of CCT needs to be quantified, as it is uncomfortable, and women may prefer a 'hands‐off' approach. In addition its implementation has resource implications in terms of training of healthcare providers.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of controlled cord traction during the third stage of labour, either with or without conventional active management.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (29 January 2014), PubMed (1966 to 29 January 2014), and reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials comparing planned CCT versus no planned CCT in women giving birth vaginally.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors assessed trial quality and extracted data using a standard data extraction form.

Main results

We included three methodologically sound trials with data on 199, 4058 and 23,616 women respectively. Blinding was not possible, but bias could be limited by the fact that blood loss was measured objectively.

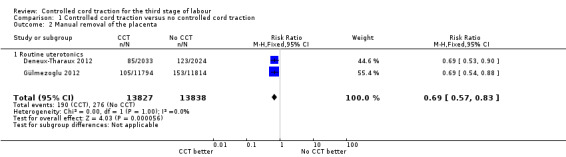

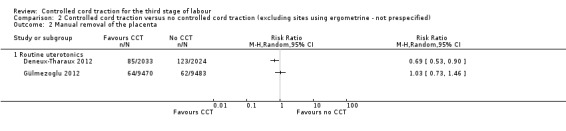

There was no difference in the risk of blood loss ≥ 1000 mL (three trials, 27,454 women; risk ratio (RR) 0.91, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.77 to 1.08). Manual removal of the placenta was reduced with CCT (two trials, 27,665 women; RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.83). In the World Health Organization (WHO) trial the reduction in manual removal occurred mainly in sites where ergometrine was used routinely in the third stage of labour. The non‐prespecified analysis excluding sites routinely using ergometrine for management of the third stage of labour found no difference in the risk of manual removal of the placenta in the WHO trial (one trial, 23,010 women; RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.46). The policy of restricting the third stage of labour to 30 minutes (4057 women; RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.90) may have had an effect in the French study.

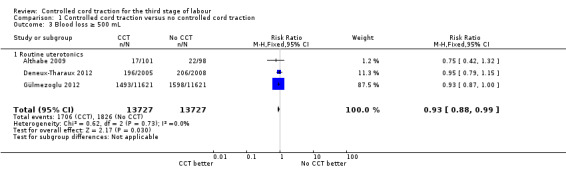

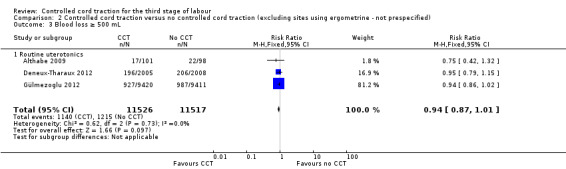

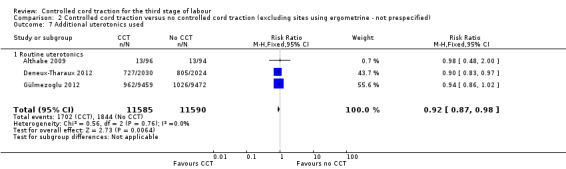

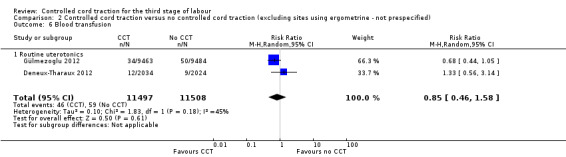

Among the secondary outcomes, there were reductions in blood loss ≥ 500 mL (three trials, 27,454 women; RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.88 to 0.99), mean blood loss (two trials, 27,255 women; mean difference (MD) ‐10.85 mL, 95% CI ‐16.73 to ‐4.98), and duration of the third stage of labour (two trials, 27,360 women; standardised MD ‐0.57, ‐0.59 to ‐0.54). There were no clear differences in use of additional uterotonics (three trials, 27,829 women; average RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.02), blood transfusion, maternal death/severe morbidity, operative procedures nor maternal satisfaction. Maternal pain (non‐prespecified) was reduced in one trial (3760 women; RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.99).

The following secondary outcomes were not reported upon in any of the trials: retained placenta for more than 60 minutes or as defined by trial author; maternal haemoglobin less than 9 g/dL at 24 to 48 hours post‐delivery or blood transfusion; organ failure; intensive care unit admission; caregiver satisfaction; cost‐effectiveness; evacuation of retained products; or infection.

Authors' conclusions

CCT has the advantage of reducing the risk of manual removal of the placenta in some circumstances, and evidence suggests that CCT can be routinely offered during the third stage of labour, provided the birth attendant has the necessary skills. CCT should remain a core competence of skilled birth attendants. However, the limited benefits of CCT in terms of severe PPH would not justify the major investment which would be needed to provide training in CCT skills for birth attendants who do not have formal training. Women who prefer a less interventional approach to management of the third stage of labour can be reassured that when a uterotonic agent is used, routine use of CCT can be omitted from the 'active management' package without increased risk of severe PPH, but that the risk of manual removal of the placenta may be increased.

Research gaps include the use of CCT in the absence of a uterotonic, and the place of uterine massage in the management of the third stage of labour.

Plain language summary

Cord traction to deliver the afterbirth

The third stage of labour refers to the time between birth of the baby and complete expulsion of the placenta. Some degree of blood loss occurs after the birth of the baby as a result of this separation of the placenta. Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) is a major cause of maternal deaths in both high‐income and low‐income countries. 'Active management of the third stage of labour' refers to the processes of giving the mother a medicine (usually by injection) to help the womb to contract, clamping the baby's cord, and pulling on the cord while applying counter pressure to help deliver the placenta (controlled cord traction, CCT). It may be uncomfortable for the mother and may interfere with her preference for a natural birth process. Birth attendants need specific training to carry out CCT.

This review of randomised controlled trials included three trials in women giving birth vaginally. The trials were methodologically good and findings were consistent. One of these trials was a large study conducted across eight countries, involving over 23,000 women, another was conducted in several sites in France involving over 4000 women and one was a single centre trial in Uruguay involving nearly 200 women. CCT did not clearly reduce severe PPH (blood loss > 1000 mL) but resulted in a small reduction in PPH (blood loss > 500 mL) and mean blood loss. It did reduce the risk of having to manually remove the placenta. Its use should be recommended if the care provider has the skills to administer CCT safely.

Background

Description of the condition

The third stage of labour refers to the period between the birth of the baby and complete expulsion of the placenta. Some degree of blood loss occurs after the birth of the baby due to separation of the placenta. This is a risky period, because the uterus may not contract well after birth and heavy blood loss can endanger the life of the mother. Different approaches, such as active management and expectant management, are proposed for the management of the third stage of labour.

Postpartum haemorrhage is defined as blood loss of 500 mL or more after birth; severe postpartum haemorrhage as 1000 mL or more. Postpartum haemorrhage is a major cause of maternal mortality in both high‐income and low‐income countries. Globally, it is estimated that postpartum haemorrhage occurs in about 11% of women who give birth. The incidence is thought to be much higher in low‐income countries, where many women do not have access to a skilled attendant at birth, and where active management of the third stage of labour may not be routine (Mousa 2007).

Description of the intervention

Once the uterus is felt to contract, traction is applied to the umbilical cord with counter‐pressure suprapubically on the uterus, until the placenta delivers.

Active management consists of a group of interventions, including administration of a prophylactic uterotonic (at or after delivery of the baby), early cord clamping and cutting, controlled cord traction to deliver the placenta, and uterine massage. Recently, due to emerging data on beneficial effects of delayed cord clamping on term (McDonald 2013) and preterm (Rabe 2012) newborn haematological indices, international recommendations on the timing of cord clamping have changed. It is recommended to delay cord clamping until the caregiver is ready to initiate controlled cord traction (thought to be around two to three minutes) (WHO 2007). Uterotonics, used as part of the active management of the third stage of labour include synthetic oxytocin, ergometrine, and various prostaglandins. Oxytocin has the advantage of minimal side effects when given intramuscularly or by slow intravenous infusion. The limitations are that it is not very heat stable, and requires parenteral administration. Uterine massage (transabdominal rubbing of the uterus to stimulate contractions by release of endogenous prostaglandins) is usually recommended after delivery of the placenta.

On the other hand, expectant management means waiting for the signs of separation of the placenta and its spontaneous delivery, and late cord clamping, which is clamping the umbilical cord when cord pulsation has ceased (hands‐off approach) (Begley 2011).

There is good evidence that the package of active management of the third stage of labour in women at mixed risk of bleeding reduces the occurrence of severe postpartum haemorrhage by approximately 60% to 70% (Begley 2011). A survey of policies in 14 European countries (part of the EUPHRATES Study) found that policies of using uterotonics for the management of the third stage of labour are widespread, but policies about agents, timing, clamping, and cutting the umbilical cord and the use of controlled cord traction differ widely (Winter 2007). Differences in policies and quality of care (Bouvier‐Colle 2001) have been cited as being responsible for large differences (up to 10‐fold) in rates of postpartum haemorrhage between countries in Europe (Zhang 2005).

Controlled cord traction is one of the components of active management of the third stage of labour that requires training in manual skill for it to be performed appropriately. Cord traction was introduced into obstetric practice by Brandt in 1933 and Andrews in 1940 (Brandt 1933). The procedure, which became known as the Brandt‐Andrews manoeuvre, consists of elevating the uterus suprapubically while maintaining steady traction on the cord, once there is clinical evidence of placental separation and the uterus is contracted. In 1962, the term 'controlled cord traction' was introduced by Spencer as a modification which aims to facilitate the separation of the placenta once the uterus contracts, and thus shorten the third stage of labour (Spencer 1962). This is achieved by applying traction on the cord, accompanied by counter‐traction to the body of the uterus towards the umbilicus (Stearn 1963). Current clinical recommendations and most recent studies describe this or a similar method (ICM 2003).

Controlled cord traction may result in complications such as uterine inversion, particularly if traction is applied before the uterus has contracted sufficiently, and without applying effective counter‐pressure to the uterine fundus. It is therefore a manual skill, which requires considerable practical training in order to be applied safely. Its use is limited to settings with access to birth attendants with reasonably high levels of skill and training. If it is possible to omit controlled cord traction from the active management package without losing efficacy, this would have major implications for effective management of the third stage of labour in settings with limited human resources.

Expectant management of the third stage of labour is preferred by some women and practitioners. It is seen as a more physiological and less interventionist approach, avoids uncomfortable procedures shortly after birth when the mother wishes to concentrate on the baby, and reduces the risk of uterine inversion. Sometimes nipple stimulation is used to enhance uterine contractions by stimulating the release of endogenous oxytocin.

Cord traction may be used during caesarean section. This is covered in another Cochrane review (Anorlu 2008).

How the intervention might work

Cord traction may hasten the process of separation and delivery of the placenta, thus reducing blood loss and the incidence of retained placenta. It is thought that administration of a uterotonic drug may cause uterine contraction and retention of the placenta if not combined with controlled cord traction.

Why it is important to do this review

Active management of the third stage of labour (AMTSL) has been shown to be beneficial. Controlled cord traction (CCT) is one of the components of AMTSL. This technique, however, requires training in manual skill for it to be performed appropriately. At community level, where there are limited trained personnel, controlled cord traction may be difficult and costly to implement. It is therefore, important to evaluate whether CCT is really necessary as part of the AMTSL package.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of controlled cord traction during the third stage of labour, either with or without conventional active management.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered randomised controlled trials evaluating the effects of controlled cord traction. Cluster‐randomised trials would also be included but we would exclude quasi‐random allocation trials. Trials using a cross‐over design would not be appropriate as each participant has only one opportunity for the intervention.

Types of participants

Women who have given birth vaginally at 24 weeks' gestation or more.

Types of interventions

Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction (both with uterotonics). Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction (both with no uterotonics, with or without uterine massage as an additional intervention).

Types of outcome measures

We chose severe postpartum haemorrhage (blood loss 1000 mL or more) as one primary outcome, as blood loss between 500 mL and 1000 mL is not usually associated with serious clinical morbidity.

Primary outcomes

Blood loss of 1000 mL or more after birth

Manual removal of the placenta

Secondary outcomes

Blood loss of 500 mL or more after birth

Mean blood loss

Mean duration of the third stage of labour

Retained placenta for more than 60 minutes or as defined by trial author

Blood transfusion

Maternal haemoglobin less than 9 g/dL at 24 to 48 hours post‐delivery or blood transfusion

Use of additional uterotonics during or after the third stage of labour

Maternal death or severe morbidity (e.g. operative procedures, organ failure, intensive care unit admission)

Operative procedures (e.g. hysterectomy, uterine compression sutures)

Organ failure

Intensive care unit admission

Maternal death

Maternal satisfaction

Caregiver satisfaction

Measures of cost‐effectiveness as defined by trial authors

Evacuation of retained products

Infection

Maternal pain (non‐prespecified outcome)

Cord rupture (non‐prespecified outcome)

Uterine inversion (non‐prespecified outcome)

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (29 January 2014).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and Embase, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

In addition we searched PubMed (1966 to 29 January 2014) using the search strategy detailed in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of retrieved studies.

We did not apply any language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

The authors participated in a multicentre clinical trial of controlled cord traction (Gülmezoglu 2012). Decisions regarding the inclusion and interpretation of this trial were checked independently by a Research Associate working for the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Selection of studies

Two review authors (Justus Hofmeyr (GJH) and Nolundi Mshweshwe (NM)) independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, consulted the third author or, if necessary, the editor assigned to the review.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, GJH and NM extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion. We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2014) and checked it for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (GJH and NM) independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or, if necessary, by involving another assessor.

(1) Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding would be unlikely to affect results. We planned to assess blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We planned to assess blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups; or less than 20% losses to follow‐up);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting bias

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found. We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s prespecified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s prespecified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other sources of bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed whether studies that included multiple pregnancies accounted appropriately for non‐independence of babies from the same pregnancy in the analysis. There are several ways this can be done, and these studies should present something like an odds ratio adjusted for non‐independence. If adjustment was not done, we assessed the potential for bias i.e. if multiples only made up a small proportion of the total then there is probably not much potential for bias.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low risk of other bias;

high risk of other bias;

unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies are at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we consider it likely to impact on the findings. In future updates of this review, as more data become available we will explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses (see Sensitivity analysis).

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference (MD) if outcomes are measured in the same way between trials. In future updates, if appropriate, we will use the standardised MD to combine trials that measure the same outcome, but use different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

In future updates, if cluster‐randomised trials are identified for inclusion, we will include cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually randomised trials. We will adjust their sample using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population (Higgins 2011). If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a subgroup analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we note levels of attrition. In future updates, as more data become available we will explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, we will carry out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempt to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and all participants will be analysed in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each trial will be the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes are known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if I² is greater than 30% and either Tau² is greater than zero, or there is a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

When there are 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis we will investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry is suggested by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using Review Manager software (RevMan 2014). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials were examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods were judged sufficiently similar. If there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity was detected, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary if an average treatment effect across trials was considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary was treated as the average of the range of possible treatment effects and we discussed the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect was not clinically meaningful we did not combine trials.

For the random‐effects analyses, the results were presented as the average treatment effect with its 95% CI, and the estimates of Tau² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In future updates of this review, if we identify substantial heterogeneity, we will investigate it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We will consider whether an overall summary is meaningful, and if it is, use random‐effects analysis to produce it.

We plan to carry out the following subgroup analyses.

Women with routine use of uterotonics, no routine use, or mixed/uncertain use.

Women with routine use of uterine massage before or after placental delivery, no routine use, or mixed/unclear use.

Women with and without placental drainage, or mixed or unclear use of placental drainage.

We will use all outcomes in the subgroup analysis.

We will assess subgroup differences by interaction tests available within Review Manager (RevMan 2014). We will report the results of subgroup analyses quoting the Chi² statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

Sensitivity analysis

As more data become available we will conduct sensitivity analyses by comparing the outcomes before and after exclusion of trials with 'high' or 'unclear' risk of bias for sequence generation or allocation concealment.

We have conducted a non‐prespecified sensitivity analysis excluding sites where ergometrine was used for third stage management. The reason for this is that in the largest trial included in the review (Gülmezoglu 2012), a reduction in manual removal of the placenta was found to be limited to the Philippines sites, which were the only sites where ergometrine was routinely used for third stage management.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The search of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register found 14 trial reports: we included three studies (Althabe 2009; Deneux‐Tharaux 2012; Gülmezoglu 2012), and excluded five studies (Artymuk 2014; Bonham 1963; Kemp 1971; Khan 1997; Sharma 2005). The PubMed search did not retrieve any additional papers (see Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included three studies (Althabe 2009; Deneux‐Tharaux 2012; Gülmezoglu 2012) (see Characteristics of included studies).

Excluded studies

We excluded five studies (see Characteristics of excluded studies). Three were excluded because they were quasi‐randomised trials (Artymuk 2014; Bonham 1963; Kemp 1971). Two trials were excluded because they compared controlled cord traction (CCT) with routine uterotonics with passive third stage without early uterotonics (oxytocin infusion only after delivery of the placenta) (Khan 1997), or draining versus non‐draining of the placenta (Sharma 2005).

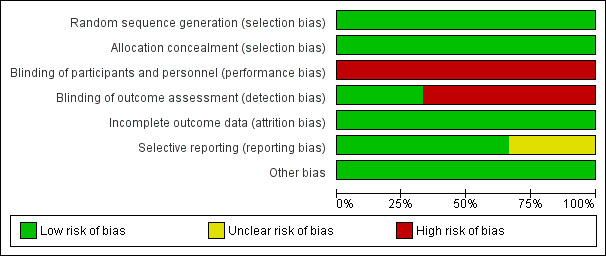

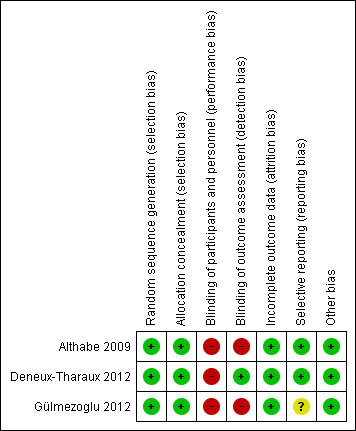

Risk of bias in included studies

Please see Figure 2 and Figure 3 for a summary of risk of bias assessments.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

We assessed all three trials (Althabe 2009; Deneux‐Tharaux 2012; Gülmezoglu 2012) as having low risk of bias for allocation concealment and sequence generation. All three used appropriate random sequence generation, and allocation concealment was by means of opaque sealed envelopes (Althabe 2009), on‐line allocation (Deneux‐Tharaux 2012) or local computer‐based allocation (Gülmezoglu 2012).

Blinding

Blinding was not possible (Althabe 2009; Deneux‐Tharaux 2012; Gülmezoglu 2012). Since the researchers were unblinded as to which group the participant belonged to, there is high risk of observer bias. Bias in the assessment of blood loss was minimised by using objective measurement.

Incomplete outcome data

Only 5/204 women were not included in the final analysis in the Althabe 2009 study. In the Gülmezoglu 2012 trial a modified intention‐to‐treat analysis (excluding women delivered by caesarean section ‐ 343 in the CCT group and 366 in the no CCT group) was used. The final numbers included in the analysis were 11,820/12,163 (97.2%) allocated, and 11,861/12,227 (97.0%), respectively. In the study of Deneux‐Tharaux 2012, 297 (6.8%) were excluded after enrolment, 294 for intrapartum caesarean section and three declined to participate.

Selective reporting

There are no obvious sources of selective reporting.

Other potential sources of bias

No obvious sources of bias, other than the lack of blinding.

Effects of interventions

There was heterogeneity between the trials for several outcomes, and for which we used a random‐effects analysis.

Primary analysis including sites routinely using ergometrine for management of the third stage of labour

Primary outcomes

There was no difference in the risk of blood loss ≥ 1000 mL (three trials, 27,454 women; risk ratio (RR) 0.91, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.77 to 1.08) (Analysis 1.1). Manual removal of the placenta was reduced with CCT (two trials, 27,665 women; RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.83) (Analysis 1.2). In the WHO trial the reduction in manual removal occurred mainly in sites where ergometrine was used routinely in the third stage of labour (see sensitivity analysis below). In the French study the effect on manual removal of the placenta may have been due to the policy of restricting the third stage of labour to 30 minutes.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction, Outcome 1 Blood loss ≥ 1000 mL.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction, Outcome 2 Manual removal of the placenta.

Secondary outcomes

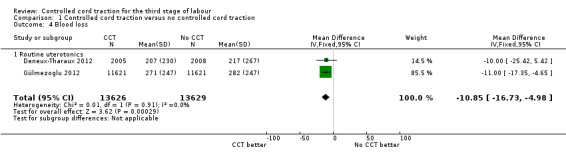

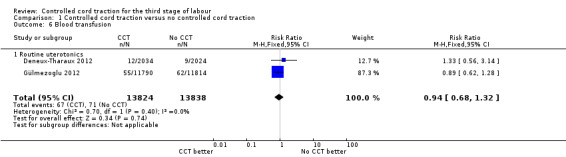

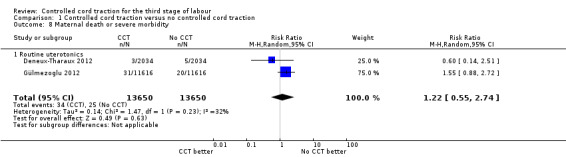

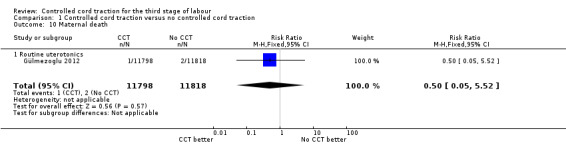

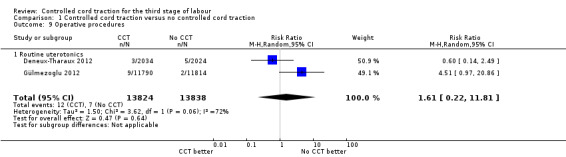

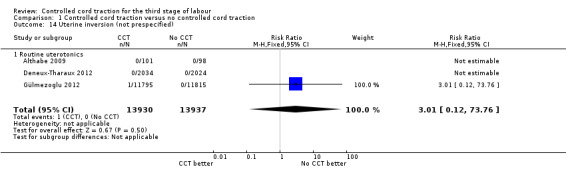

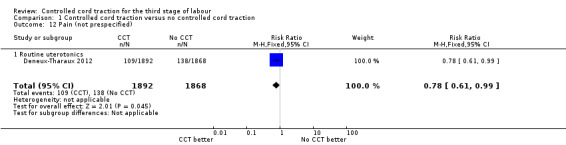

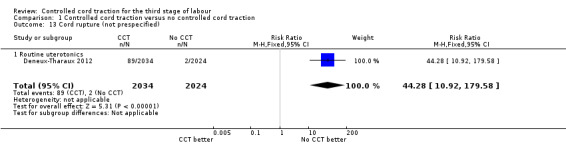

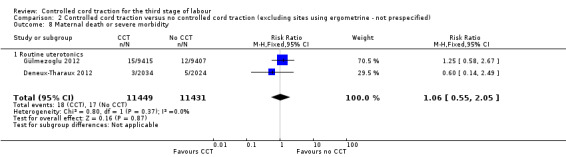

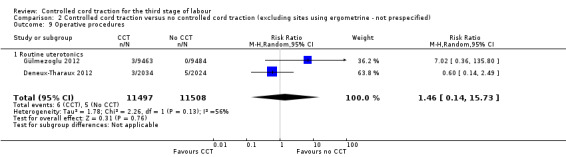

Among the secondary outcomes, there were reductions in blood loss ≥ 500 mL (three trials, 27,454 women; RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.88 to 0.99) (Analysis 1.3), mean blood loss (two trials, 27,255 women; mean difference (MD) ‐10.85 mL, 95% CI ‐16.73 to ‐4.98) (Analysis 1.4), and duration of the third stage of labour (two trials, 27,360 women; standardised MD ‐0.57, ‐0.59 to ‐0.54) (Analysis 1.5). There was no clear reduction in use of additional uterotonics (three trials, 27,829 women; average RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.02; heterogeneity: Tau² = 0.00; Chi² = 3.44, df = 2 (P = 0.18); I² = 42%) (Analysis 1.7), blood transfusion (Analysis 1.6), maternal death/severe morbidity (Analysis 1.8; Analysis 1.10), operative procedures (Analysis 1.9), nor maternal satisfaction (Analysis 1.11). Non‐prespecified outcomes: one case of uterine inversion was reported with CCT (Analysis 1.14), maternal pain was reduced in one trial (3760 women; RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.99) (Analysis 1.12); in one trial cord rupture as expected was far more common with CCT (89/2034 versus 2/2024; 4058 women; RR 44.28, 95% CI 10.92 to 179.58) (Analysis 1.13).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction, Outcome 3 Blood loss ≥ 500 mL.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction, Outcome 4 Blood loss.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction, Outcome 5 Duration of 3rd stage of labour (minutes).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction, Outcome 7 Additional uterotonics used.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction, Outcome 6 Blood transfusion.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction, Outcome 8 Maternal death or severe morbidity.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction, Outcome 10 Maternal death.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction, Outcome 9 Operative procedures.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction, Outcome 11 Maternal satisfaction.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction, Outcome 14 Uterine inversion (not prespecified).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction, Outcome 12 Pain (not prespecified).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction, Outcome 13 Cord rupture (not prespecified).

The following secondary outcomes were not reported upon in any of the trials: retained placenta for more than 60 minutes or as defined by trial author; maternal haemoglobin less than 9 g/dL at 24 to 48 hours post‐delivery or blood transfusion; organ failure; intensive care unit admission; caregiver satisfaction; cost‐effectiveness; evacuation of retained products; or infection.

Non‐prespecified sensitivity analysis excluding sites routinely using ergometrine for management of the third stage of labour

Primary outcomes

The results excluding sites routinely using ergometrine for management of the third stage of labour were similar to the primary analysis (Analysis 2.1), except that the difference in the risk of manual removal of the placenta in the WHO trial was eliminated (one trial, 23,010 women; RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.46) (Analysis 2.2). This result was significantly different from the result of the French trial (4057 women; RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.90) (Analysis 2.2). The effect in the French trial may have been due to the fact that the duration of the third stage of labour was limited to 30 minutes. Because of substantial clinical and statistical heterogeneity, we did not combine the results of the two trials.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction (excluding sites using ergometrine ‐ not prespecified), Outcome 1 Blood loss ≥ 1000 mL.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction (excluding sites using ergometrine ‐ not prespecified), Outcome 2 Manual removal of the placenta.

Secondary outcomes

There were marginal changes for only two results: the reduction in blood loss ≥ 500 mL was no longer statistically significant (three trials, 23,043 women; RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.01), probably because a reduction in sample size increased the 95% CI (Analysis 2.3); and the reduction in use of additional uterotonics was significant (three trials, 23,175 women; RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.87 to 0.98), probably because there was less heterogeneity and we used a fixed‐effect analysis (Analysis 2.7). For all other secondary outcomes, the results were similar to the primary analysis (Analysis 2.4; Analysis 2.5; Analysis 2.6; Analysis 2.8; Analysis 2.9; Analysis 2.10; Analysis 2.11).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction (excluding sites using ergometrine ‐ not prespecified), Outcome 3 Blood loss ≥ 500 mL.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction (excluding sites using ergometrine ‐ not prespecified), Outcome 7 Additional uterotonics used.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction (excluding sites using ergometrine ‐ not prespecified), Outcome 4 Blood loss.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction (excluding sites using ergometrine ‐ not prespecified), Outcome 5 Duration of 3rd stage of labour (minutes).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction (excluding sites using ergometrine ‐ not prespecified), Outcome 6 Blood transfusion.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction (excluding sites using ergometrine ‐ not prespecified), Outcome 8 Maternal death or severe morbidity.

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction (excluding sites using ergometrine ‐ not prespecified), Outcome 9 Operative procedures.

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction (excluding sites using ergometrine ‐ not prespecified), Outcome 10 Maternal death.

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction (excluding sites using ergometrine ‐ not prespecified), Outcome 11 Uterine inversion (not prespecified).

Discussion

Summary of main results

The results of this review are dominated by the large WHO trial (Gülmezoglu 2012), but are consistent with the results of the smaller trials (Althabe 2009; Deneux‐Tharaux 2012). There was no significant reduction in severe postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) (blood loss > 1000 mL), but a small reduction in PPH (blood loss > 500 mL) and mean blood loss with controlled cord traction (CCT). There was a significant reduction in manual removal of the placenta. In the WHO trial (Gülmezoglu 2012), the reduction in manual removal occurred mainly in sites where ergometrine was used routinely in the third stage of labour. The non‐prespecified analysis, excluding sites routinely using ergometrine for management of the third stage of labour, found no difference in the risk of manual removal of the placenta in the WHO trial. There may be some evidence that this decrease could be driven by imposed limitations on third stage times or by the routine use of ergometrine at some trial sites.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The evidence includes a large, multicentre trial conducted by the WHO in several continents (Gülmezoglu 2012), a large trial in several centres in France (Deneux‐Tharaux 2012), as well as a small single centre trial in Uruguay (Althabe 2009) and should be widely applicable.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence is high in that three methodologically sound trials with large sample sizes are included. Lack of blinding is a possible source of bias, but has been minimised by use of objective measurement of blood loss.

Potential biases in the review process

The authors participated in one of the included trials (Gülmezoglu 2012). Decisions regarding the inclusion and interpretation of this trial were checked independently by a Research Associate working for the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The findings of the review were consistent with those of the two excluded quasi‐randomised controlled trials (Bonham 1963; Kemp 1971).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Although there was no significant difference in the one primary outcome (blood loss > 1000 mL), controlled cord traction (CCT) has the advantage of reducing the risk of manual removal of the placenta, and blood loss > 500 mL, a modest shortening of the duration of the third stage of labour, and reduced mean blood loss. Thus evidence suggests that CCT can be routinely offered during the third stage of labour, provided the birth attendant has the necessary skills. It should be noted that in two of the trials reviewed (Althabe 2009; Gülmezoglu 2012), 5% to 6% of women in the 'no CCT' groups required CCT, and thus controlled CCT should remain a core competence of skilled birth attendants, and continued routine use of CCT has the benefit of maintaining skills for when the procedure is really needed. In the French study (Deneux‐Tharaux 2012) where no CCT was the standard of practice prior to the trial, CCT was used in only 1.6% of the 'no CCT' group. However, in view of the lack of evidence of a significant effect on severe postpartum haemorrhage (PPH), despite the large sample size, the major investment which would be needed to provide training in CCT skills for birth attendants who do not have formal training would probably not be justified. Women who prefer a less interventional approach to management of the third stage of labour can be reassured that when a uterotonic agent is used, routine use of CCT can be omitted from the 'active management' package without a significant increase in risk of severe postpartum haemorrhage, but there is an increased risk of manual removal of the placenta.

This review found no evidence of benefits or risks of CCT when a uterotonic is not used.

Implications for research.

Research gaps include the use of controlled cord traction in the absence of a uterotonic, and the place of uterine massage in the management of the third stage of labour.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 9 May 2019 | Amended | Edited Declarations of interest |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2009 Review first published: Issue 1, 2015

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 28 March 2017 | Amended | Typographical error corrected in the study flow diagram. |

Acknowledgements

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Team for administrative and editorial support.

As part of the pre‐publication editorial process, this review has been commented on by three peers (an editor and two referees who are external to the editorial team) and the Group's Statistical Adviser.

The World Health Organization and A Metin Gülmezoglu retain copyright and all other rights in their respective contributions to the manuscript of this Review as submitted for publication

Appendices

Appendix 1. PubMed search strategy

(third stage OR post partum OR postpartum OR postnatal* OR post natal* OR "Delivery, Obstetric/methods"[MeSH]) AND (cord AND traction)

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Blood loss ≥ 1000 mL | 3 | 27454 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.77, 1.08] |

| 1.1 Routine uterotonics | 3 | 27454 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.77, 1.08] |

| 2 Manual removal of the placenta | 2 | 27665 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.57, 0.83] |

| 2.1 Routine uterotonics | 2 | 27665 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.57, 0.83] |

| 3 Blood loss ≥ 500 mL | 3 | 27454 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.88, 0.99] |

| 3.1 Routine uterotonics | 3 | 27454 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.88, 0.99] |

| 4 Blood loss | 2 | 27255 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐10.85 [‐16.73, ‐4.98] |

| 4.1 Routine uterotonics | 2 | 27255 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐10.85 [‐16.73, ‐4.98] |

| 5 Duration of 3rd stage of labour (minutes) | 2 | 27360 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.57 [‐0.59, ‐0.54] |

| 5.1 Routine uterotonics | 2 | 27360 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.57 [‐0.59, ‐0.54] |

| 6 Blood transfusion | 2 | 27662 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.68, 1.32] |

| 6.1 Routine uterotonics | 2 | 27662 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.68, 1.32] |

| 7 Additional uterotonics used | 3 | 27829 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.88, 1.02] |

| 7.1 Routine uterotonics | 3 | 27829 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.88, 1.02] |

| 8 Maternal death or severe morbidity | 2 | 27300 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.55, 2.74] |

| 8.1 Routine uterotonics | 2 | 27300 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.55, 2.74] |

| 9 Operative procedures | 2 | 27662 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.61 [0.22, 11.81] |

| 9.1 Routine uterotonics | 2 | 27662 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.61 [0.22, 11.81] |

| 10 Maternal death | 1 | 23616 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.50 [0.05, 5.52] |

| 10.1 Routine uterotonics | 1 | 23616 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.50 [0.05, 5.52] |

| 11 Maternal satisfaction | 1 | 3672 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.32, 1.61] |

| 11.1 Routine uterotonics | 1 | 3672 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.32, 1.61] |

| 12 Pain (not prespecified) | 1 | 3760 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.61, 0.99] |

| 12.1 Routine uterotonics | 1 | 3760 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.61, 0.99] |

| 13 Cord rupture (not prespecified) | 1 | 4058 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 44.28 [10.92, 179.58] |

| 13.1 Routine uterotonics | 1 | 4058 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 44.28 [10.92, 179.58] |

| 14 Uterine inversion (not prespecified) | 3 | 27867 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.01 [0.12, 73.76] |

| 14.1 Routine uterotonics | 3 | 27867 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.01 [0.12, 73.76] |

Comparison 2. Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction (excluding sites using ergometrine ‐ not prespecified).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Blood loss ≥ 1000 mL | 3 | 23043 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.74, 1.11] |

| 1.1 Routine uterotonics | 3 | 23043 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.74, 1.11] |

| 2 Manual removal of the placenta | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 Routine uterotonics | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3 Blood loss ≥ 500 mL | 3 | 23043 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.87, 1.01] |

| 3.1 Routine uterotonics | 3 | 23043 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.87, 1.01] |

| 4 Blood loss | 2 | 22825 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐8.00 [‐15.89, ‐4.11] |

| 4.1 Routine uterotonics | 2 | 22825 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐8.00 [‐15.89, ‐4.11] |

| 5 Duration of 3rd stage of labour (minutes) | 2 | 22819 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.54 [‐0.56, ‐0.51] |

| 5.1 Routine uterotonics | 2 | 22819 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.54 [‐0.56, ‐0.51] |

| 6 Blood transfusion | 2 | 23005 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.46, 1.58] |

| 6.1 Routine uterotonics | 2 | 23005 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.46, 1.58] |

| 7 Additional uterotonics used | 3 | 23175 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.87, 0.98] |

| 7.1 Routine uterotonics | 3 | 23175 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.87, 0.98] |

| 8 Maternal death or severe morbidity | 2 | 22880 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.55, 2.05] |

| 8.1 Routine uterotonics | 2 | 22880 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.55, 2.05] |

| 9 Operative procedures | 2 | 23005 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.46 [0.14, 15.73] |

| 9.1 Routine uterotonics | 2 | 23005 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.46 [0.14, 15.73] |

| 10 Maternal death | 2 | 23016 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.06, 16.01] |

| 10.1 Routine uterotonics | 2 | 23016 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.06, 16.01] |

| 11 Uterine inversion (not prespecified) | 2 | 4257 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11.1 Routine uterotonics | 2 | 4257 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Althabe 2009.

| Methods | The study was an individually randomised superiority trial. Women who agreed to participate provided written informed consent and were randomised into 1 of 2 intervention groups when vaginal delivery was imminent. The randomisation was stratified by hospital. 204 women were randomised, 103 allocated to the controlled cord traction group and 101 to the hands‐off group | |

| Participants |

Inclusion criteria: women with imminent vaginal delivery in Montevideo & Uruguay public hospital: hospital de clinicas; from 30 December 2006 to September 18 2007; and Hospital Pereire Rossel from 29 June 2007 to 26 October 2007 Age of 18 years and older Single, term baby No contraindication to prophylactic oxytocin Exclusion criteria: severe acute complications (eclampsia and haemorrhage) that were present in labour and that required emergency action |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention: controlled cord traction Comparison: hands‐off |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcomes(s): blood loss during the third stage of labour. Blood was collected with a purpose designed plastic drape placed under the woman for 20 minutes or until bleeding stopped or she was transferred to another ward. Blood volume was measured by weighing the drape Secondary outcome(s): postpartum haemorrhage greater than or equal to 500 mL Postpartum haemorrhage greater than or equal to 1000 mL Length of the third stage of labour Use of additional uterotonics Need for manual removal of the placenta Uterine curettage or other therapeutic manoeuvres |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Sequence generated at the co‐ordinating centre using computer‐generated list of numbers with randomly permuted blocks of 4‐6 in a 1:1 ratio |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Use of sequentially numbered opaque sealed envelops. When a woman is about to deliver, next numbered envelope was opened |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk |

Participant:not blinded Clinician: not blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Outcome assessor: not blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Only 5 women not included in analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No indication of selective reporting |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other source of bias identified |

Deneux‐Tharaux 2012.

| Methods | ||

| Participants | Included: women 18 years or more, singleton pregnancy, > 35 weeks, planned vaginal delivery Excluded: severe haemostasis disease, placenta praevia, fetal death, multiple gestation, no French spoken |

|

| Interventions | Controlled cord traction: after birth controlled cord traction was started with a firm uterine contraction without waiting for placental separation. The lower segment was grasped between the thumb and index finger of 1 hand and steady pressure exerted upwards; at the same time the cord was held in the other hand and steady cord traction exerted downwards and backwards, exactly countered by the upwards pressure of the first hand, so that the position of the uterus remained unchanged. If the placenta was not expelled on the first attempt, controlled cord traction was repeated using counter pressure with the next uterine contraction. In the control arm, the attendant awaited the signs of spontaneous placental separation and descent into the lower uterine segment. Once the placenta was separated it was delivered through the mother’s efforts (helped by fundal pressure or soft tension on the cord to facilitate placental expulsion through the vagina if needed). All other aspects of management of the third stage were identical in both arms: intravenous injection of 5 IU oxytocin and clamping and cutting of the cord within two minutes of birth; placement of a graduated (100 mL graduation) collector bag (MVF Merivaara France) just after birth, left in place until the birth attendant judged that bleeding had stopped and that there was no reason to monitor further, 24 and always at least for 15 minutes; and manual removal of the placenta at 30 minutes after birth if not expelled. A blood sample was taken from all women on the second day after delivery to measure haemoglobin level and haematocrit |

|

| Outcomes | Primary: postpartum haemorrhage, defined by a blood loss of 500 mL, measured with a graduated collector bag. Secondary: measured blood loss 1000 mL at bag removal, mean measured blood loss at 15 minutes after birth (the bag had to be left in place at least 15 minutes to have 1 measure of blood loss at the same time point in all women), mean measured postpartum blood loss at bag removal, and mean changes in peripartum haemoglobin level and haematocrit (difference between haemoglobin level and haematocrit before delivery and at day 2 postpartum). Other secondary outcomes included use of supplementary uterotonic treatment; postpartum transfusion (until discharge); arterial embolisation or emergency surgery for postpartum haemorrhage; other characteristics of the third stage, including duration, manual removal of the placenta; and women’s experience of the third stage, assessed by a self administered questionnaire on day 2 postpartum. Safety outcomes included uterine inversion, cord rupture, and pain |

|

| Notes | Five French university hospitals between 1 January 2010 and 31 January 2011 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Allocation was stratified by centre and balanced in blocks of 4 |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Centrally through an automated web‐based system, which ensured allocation concealment |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Blinding not possible, but primary outcome objective measurement of blood loss |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Blinding not possible, but primary outcome objective measurement of blood loss |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | After randomisation and before delivery, 294 (6.8%) women became ineligible because an intrapartum caesarean was performed, and three others declined to participate. Women who underwent caesarean section were included in the analysis for outcomes where this was possible |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No indication of selective reporting |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other risk of bias identified |

Gülmezoglu 2012.

| Methods | Randomised non‐inferiority trial | |

| Participants | Women giving birth with no significant complications | |

| Interventions | Controlled cord traction versus no controlled cord traction. All women receive uterotonics | |

| Outcomes | Blood loss; duration of 3rd stage of labour; maternal outcomes. Blood loss was measured by collection in a plastic drape which was weighed | |

| Notes | Additional data were provided by the first author (standard deviations for continuous data) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | The random allocation sequence was computer generated centrally at the World Health Organization |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | At each facility, a computer programmed with the random allocation sequence was provided and allocation was made once the woman's details were entered into the computer by local investigators. Each site had 1 spare computer in case of break‐down or theft; if both failed the centre had to revert to sealed opaque envelopes as back‐up option |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk |

Participants: not blinded Investigators: not blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Outcome assessors: not blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Modified intention to treat analysis (excluding women delivered by caesarean section ‐ 343 in the controlled cord traction group and 366 in the no controlled cord traction group) was used. The final numbers included in the analysis were 11820/12163 (97.2%) allocated, and 11,861/12,227 (97.0%), respectively |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Outcome specified in the protocol (2009) ‐ postpartum maternal haemoglobin specified as a secondary outcome, not reported on in the full published report of the trial |

| Other bias | Low risk | Baseline characteristics appear similar (Table 1, P 1724) |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Artymuk 2014 | Quasi‐random allocation (odd and even dates) used |

| Bonham 1963 | Quasi‐random allocation. All women allocated to cord traction versus no cord traction in 'random' 2‐week periods |

| Kemp 1971 | Quasi‐random allocation (using odd and even ages). 713 consecutive women were allocated to placental delivery by cord traction or abdominal manipulation. Blood loss was similar between groups. Manual removal of the placenta was used in 3/379 women with cord traction and 6/334 women with abdominal manipulation |

| Khan 1997 | The comparison was between controlled cord traction plus routine oxytocin at delivery, versus minimal intervention with an oxytocin infusion only after delivery of the placenta |

| Sharma 2005 | This study compared placental drainage with no placental drainage. Cord traction was used in both groups. Placental drainage was associated with shorter third stage but no difference in postpartum haemorrhage |

Differences between protocol and review

The review includes a non‐prespecified sensitivity analysis, excluding sites using ergometrine for routine care in the third stage of labour (see above).

Three outcomes, not prespecified in the protocol, were included in the review: maternal pain; cord rupture; and uterine inversion.

Contributions of authors

Nolundi Mshweshwe (NM) wrote the first draft of the protocol, extracted data from the trials and revised the review. G Justus Hofmeyr (GJH) revised the protocol, did duplicate data extraction, and wrote the first draft of the complete review. A Metin Gülmezoglu (AG) revised the protocol and the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

-

University of the Witwatersrand (GJH), South Africa.

Financial support

UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP), Switzerland.

External sources

No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

GJH, AMG and NM participated in a multicentre clinical trial of controlled cord traction (Gülmezoglu 2012). Decisions regarding the inclusion and interpretation of this trial were checked independently by a Research Associate working for the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

GJH receives royalties from UpToDate for chapters related to breech pregnancy, delivery of a baby in breech presentation and external cephalic version. UpToDate is an electronic publication by Wolters Kluwer to disseminate evidence‐based medicine (such as Cochrane reviews).

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Althabe 2009 {published data only}

- Althabe F, Aleman A, Tomasso G, Gibbons L, Vitureira G, Belizan JM, et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial of controlled cord traction to reduce postpartum blood loss. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2009;107(1):4‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Deneux‐Tharaux 2012 {published data only}

- Deneux‐Tharaux. Correction to: Effect of routine controlled cord traction as part of the active management of the third stage of labour on postpartum haemorrhage: multicentre randomised controlled trial (TRACOR). BMJ 2013;346:f2542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deneux‐Tharaux C. Correction to: Effect of routine controlled cord traction as part of the active management of the third stage of labour on postpartum haemorrhage: multicentre randomised controlled trial (TRACOR). BMJ 2013;347:f6619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deneux‐Tharaux C, Sentilhes L, Maillard F, Closset E, Vardon D. Should routine controlled cord traction be part of the active management of third stage of labor? The Tracor multicenter randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2013;208(1 Suppl):S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deneux‐Tharaux C, Sentilhes L, Maillard F, Closset E, Vardon D, Lepercq J, et al. Effect of controlled traction of the cord during the third stage of labour on the incidence of postpartum haemorrhage (Tracor study): A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Journal of Maternal‐Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 2012;25(S2):5‐6. [Google Scholar]

- Deneux‐Tharaux C, Sentilhes L, Maillard F, Closset E, Vardon D, Lepercq J, et al. Effect of controlled traction of the cord during the third stage of labour on the incidence of postpartum haemorrhage (Tracor study): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Journal of Maternal‐Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 2012;25(S2):94. [Google Scholar]

- Deneux‐Tharaux C, Sentilhes L, Maillard F, Closset E, Vardon D, Lepercq J, et al. Effect of routine controlled cord traction as part of the active management of the third stage of labour on postpartum haemorrhage: multicentre randomised controlled trial (TRACOR). BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 2013;346:f1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gülmezoglu 2012 {published data only}

- Armbruster D. Update on active management of the third stage of labour‐new data from the 2012 WHO trial. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2012;119(Suppl 3):S166. [Google Scholar]

- Gulmezoglu AM, Lumbiganon P, Landoulsi S, Widmer M, Abdel‐Aleem H, Festin M, et al. Active management of the third stage of labour with and without controlled cord traction: a randomised, controlled, non‐inferiority trial. [Erratum appears in Lancet. 2012 May 5;379(9827):1704]. Lancet 2012;379(9827):1721‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulmezoglu AM, Widmer M, Merialdi M, Qureshi Z, Piaggio G, Elbourne D, et al. Active management of the third stage of labour without controlled cord traction: a randomized non‐inferiority controlled trial. Reproductive Health 2009;6:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Artymuk 2014 {published data only}

- Artymuk N, Surina M, Marochko T. Active management of the third stage of labor with and without controlled cord traction. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2014;124(1):84‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artymuk NV, Surina MN, Kolesnikova NB, Marochko TY. Active management of the third stage of labor with and without controlled cord traction: A randomized controlled study. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2012;119(Suppl 3):S284‐S285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bonham 1963 {published data only}

- Bonham DG. Intramuscular oxytocics and cord traction in third stage of labour. BMJ 1963;2:1620‐3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kemp 1971 {published data only}

- Kemp J. A review of cord traction in the third stage of labour from 1963 to 1969. Medical Journal of Australia 1971;1(17):899‐903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Khan 1997 {published data only}

- Khan GQ, John IS, Wani S, Doherty T, Sibai BM. Controlled cord traction versus minimal intervention techniques in delivery of the placenta: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1997;177(4):770‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sharma 2005 {published data only}

- Sharma JB, Pundir P, Malhotra M, Arora R. Evaluation of placental drainage as a method of placental delivery in vaginal deliveries. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2005;271(4):343‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Anorlu 2008

- Anorlu RI, Maholwana B, Hofmeyr GJ. Methods of delivering the placenta at caesarean section. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004737.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Begley 2011

- Begley CM, Gyte GML, Devane D, McGuire W, Weeks A. Active versus expectant management for women in the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 11. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007412.pub3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bouvier‐Colle 2001

- Bouvier‐Colle MH, Ould EJ, Varnoux N, Goffinet F, Alexander S, Bayoumeu F, et al. Evaluation of the quality of care for severe obstetrical haemorrhage in three French regions. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 2001;108(9):898‐903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brandt 1933

- Brandt ML. The mechanism and management of the third stage of labour. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1933;25:662‐7. [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

ICM 2003

- International Confederation of Midwives (ICM), International Federation of Gynaecologists and Obstetricians (FIGO). International joint policy statement: management of the third stage of labour to prevent postpartum hemorrhage. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada: JOGC 2003;25:952‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McDonald 2013

- McDonald SJ, Middleton P, Dowswell T, Morris PS. Effect of timing of umbilical cord clamping of term infants on maternal and neonatal outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 7. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004074.pub3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mousa 2007

- Mousa HA, Alfirevic Z. Treatment for primary postpartum haemorrhage. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003249.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rabe 2012

- Rabe H, Diaz‐Rossello JL, Duley L, Dowswell T. Effect of timing of umbilical cord clamping and other strategies to influence placental transfusion at preterm birth on maternal and infant outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 8. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003248.pub3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2014 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014.

Spencer 1962

- Spencer PM. Controlled cord traction in management of the third stage of labour. BMJ 1962;1(5294):1728‐32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Stearn 1963

- Stearn RH. Cord traction in the management of the third stage of labour. Suid‐Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Obstetrie en Ginekologie 1963;37:925‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

WHO 2007

- Mathai M, Gülmezoglu AM, Hill S. WHO recommendations for the prevention of postpartum haemorrhage. www.who.int/making_pregnancy_safer/documents/who_mps_0706/en/index.html (accessed January 2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Winter 2007

- Winter C, Macfarlane A, Deneux‐Tharaux C, Zhang WZ, Alexander S, Brocklehurst P, et al. Variations in policies for management of the third stage of labour and the immediate management of postpartum haemorrhage in Europe. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 2007;114(7):845‐54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zhang 2005

- Zhang WH, Alexander S, Bouvier‐Colle MH, Macfarlane A, MOMS‐B Group. Incidence of severe pre‐eclampsia, postpartum haemorrhage and sepsis as a surrogate marker for severe maternal morbidity in a European population‐based study: the MOMS‐B survey. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 2005;112(1):89‐96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]