Abstract

Context

Although sport-related internal organ injuries among athletes are relatively infrequent, combining data sources enables a more comprehensive examination of their incidence.

Objective

To describe the incidence and characteristics of sport-related internal organ injuries due to direct-contact mechanisms among high school (HS) and collegiate athletes from 2005–2006 through 2014–2015.

Design

Descriptive epidemiology study.

Setting

United States HS and collegiate sports data from 3 national sports injury-surveillance systems: High School Reporting Information Online (HS RIO), the National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program (ISP), and the National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research.

Patients or Other Participants

High school and collegiate athletes in organized sports.

Main Outcome Measure(s)

Characteristics of the athlete, event, and injury were examined and stratified by data source and sport. Descriptive statistics of internal organ injuries via direct-contact mechanisms consisted of frequencies and incidence rates (IRs) per 1 000 000 athlete-exposures and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

During the 10-year period, 174 internal organ injuries were captured: 124 in HS RIO and 41 in the ISP; 9 were catastrophic. Most noncatastrophic injuries occurred among males (RIO = 85%, ISP = 89%), in football (RIO = 65%, ISP = 58%), and during competitions (RIO = 67%, ISP = 49%) and were due to player-player contact (RIO = 78%, ISP = 68%). The highest injury rates were in male contact sports: RIO football (IR = 11.7; 95% CI = 9.1, 14.2) and lacrosse (IR = 10.0; 95% CI = 3.1, 16.9); ISP: football (IR = 8.3; 95% CI = 5.0, 11.6) and ice hockey (IR = 7.9; 95% CI = 1.0, 14.7). A quarter of noncatastrophic injuries were season ending (RIO = 25%, ISP = 23%). Of the 9 catastrophic injuries, most occurred in HS (7/9) and football (7/9) and were due to player-player contact (6/9). Four resulted in death.

Conclusions

Direct-contact internal organ injuries occur infrequently; yet when they do occur, they may result in severe outcomes. These findings suggest that early recognition and a better understanding of the activities associated with the event and use or nonuse of protective equipment are needed.

Keywords: epidemiology, injury surveillance, catastrophic injuries

Key Points

Over the 10-year period, 174 internal organ injuries were captured. They occurred most often in contact sports and during competitions and were due to player-player contact. One-quarter were season ending.

Although infrequent, direct-contact internal organ injuries can result in severe outcomes. Early recognition of these conditions and further study of personal protective equipment are needed.

Surveillance is the cornerstone of the 4-stage public health approach and is defined as the ongoing, timely collection and dissemination of reliable data on a public health problem.1,2 This approach was applied to the study of sport injuries by van Mechelen et al3 in 1992: Surveillance is the first step to understanding the incidence and burden of sport injuries and forms the basis for additional research to identify injury risk factors and mechanisms. Once these items are identified, preventive measures are developed and implemented to address them. Surveillance, whether ongoing or follow-up, serves as the final, critical step in evaluating the effectiveness of preventive measures in reducing the incidence and burden of sport injuries. In the context of sport, injuries can happen during participation and have a variety of consequences ranging from initial pain and discomfort to limitations such as not being able to participate in the sport to permanent disability or death.4 From a public health perspective, the importance of the problem is defined by the incidence, burden, and severity and drives population-level research, education, and prevention activities. Consequently, in the context of sport, injuries with higher incidences, greater costs, or the most severe consequences (eg, disability or death) should and will be of higher priority and therefore garner our resources and guide research activities.5

In the United States, a number of surveillance systems provide ongoing and timely information on sport-related injuries among high school (HS) and collegiate athletes. Three commonly used systems are HS Reporting Information Online (RIO), the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Injury Surveillance Program (ISP), and the National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research (NCCSIR). Each system routinely publishes and disseminates information on sport injuries for national sport and medical organizations as well as the general public. In the fall of 2014, research staffs at each of these systems received multiple requests from news journalists for information on internal organ injuries during sports participation and putting these events in context with other injuries such as traumatic brain injuries. At the time of the requests, HS RIO had a study examining chest, rib, thoracic spine, and abdomen injuries under review at a journal (now published6); however, none of the 3 systems had previously reported on internal organ injuries.

An initial review of the literature revealed that outside of case reports7–11 and reviews on management and treatment,12–14 only 8 epidemiologic studies on the incidence of sport-related internal organ injuries had been published: 3 investigations using hospital records,15–17 2 using trauma registries,18,19 a cross-sectional study of national hospital emergency department visit data,20 an HS surveillance system no longer active,21 and a retrospective review of National Football League records (see Supplemental Table 1 (95.8KB, pdf) available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-271-17.S1).22 Collectively, these results suggested that sport-related internal organ injuries were uncommon relative to other sport injuries.15,18,19,21 The kidney and spleen were the organs injured most often,15,18,19 and these injuries most frequently occurred during football,16,18,19,21 ice hockey,15,16,18,19 soccer,15,21 skiing,19 and horseback riding.15 Incidence rates (IRs) of hospital visits due to sport-related internal organ injuries in the general pediatric population ranged from 5.6 to 6.9 per 1 million children for kidney and spleen injuries.19 At the HS level from 1997–1999, sport-specific IRs of catastrophic kidney injuries per 1 000 000 athlete-exposures (AEs) were 9.2 for football, 6.0 for girls' soccer, 3.2 for baseball, 2.6 for boys' soccer, 2.5 for girls' basketball, and 2.3 for boys' basketball.21 Injury rates were higher during competitions compared with practices.21,22

These studies were based on a variety of data sources from hospital records to trauma registries to a surveillance system, covering a variety of age groups, time periods, and selected recreational and sport activities. Four studies focused solely on kidney injuries16,17,21,22 and 4 reported on abdominal organ injuries.15,18,19,23 Hospital records and trauma registry data included more severe events, and the sport or physical activity at the time of injury was identified through e-codes, International Classification of Diseases codes (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd10cm.htm), or text-field review; however, these sources did not identify the level of the sport (eg, college, HS, youth league, recreational) or athlete status (whether the athlete was a participant in an organized sport). Dedicated surveillance systems enable characterization of sport level and athlete status as well as detailed information on the mechanisms and activities—critical information for determining whether and how the injury could have been prevented. In addition, surveillance systems provide information about the total number of participants at risk, enabling the calculation of injury rates that are critical for comparisons between sports and levels. Because sport-related internal organ injuries among athletes are relatively infrequent events with potentially severe consequences, combining data sources across multiple national surveillance systems over the same time period enables a more comprehensive examination of the problem, which should translate to more effective prevention measures.

The purpose of our study was to describe the incidence and characteristics of sport-related abdominal and thoracic internal organ injuries due to direct-contact mechanisms (contact with a player, apparatus, surface, or other object) among HS and collegiate athletic participants captured by 3 national sport injury-surveillance systems over a 10-year period (2005–2006 through 2014–2015). Case studies were presented from the most severe (catastrophic) injury events to provide context and to identify preventive factors.

METHODS

Data from 3 national surveillance systems were used to describe the characteristics and incidences of traumatic internal organ injuries due to direct-contact mechanisms that occurred during the 2005–2006 through 2014–2015 academic years. All 3 systems have been in operation for 10 or more years and have been used to characterize injuries in a number of organized HS and collegiate sports.24–30 Data from all 3 systems are reviewed and used by national sport organizations' (National Federation of State High School Associations [NFHS] and NCAA) medical advisory and sport rules committees on a regular basis to evaluate current and future sport rules, protective equipment requirements, medical care, and safety policies. For this study, internal organ injuries were defined as affecting the abdominal and thoracic internal organs (eg, kidney, lung) due to direct contact (contact with person, apparatus, surface, or object) and resulting in medical care and time loss of at least 1 day (RIO and ISP) or semipermanent or permanent disability or death (NCCSIR). Commotio cordis injuries were excluded because these events are disruptions in heart rhythm due to contact. Direct-contact mechanisms included both intentional (eg, tackle in football) and unintentional (eg, collision in the outfield) contact. Methods for each system are described in the following sections and summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Attributes and Field Definitions for 3 Surveillance Systems

| Attribute |

High School Reporting Information Online |

Collegiate NCAA Injury Surveillance Program |

National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research |

| Level | High school | NCAA collegiate institutions | High school and collegiate |

| Sports | 24 Sports (12 male, 12 female) | 25 Sports (12 male, 13 female) | 42 High school sports (21 male, 21 female) |

| 35 Collegiate sports (18 male, 17 female) | |||

| Coverage and sample information | Volunteer sample and nationally representative sample | Volunteer sample | National |

| Event capture (direct/indirect; reporter; reporting method) | Direct: Web-based reporting from ATs | Direct: Web-based reporting from ATs | Indirect: searches of publicly available sources (media, news articles) |

| Direct: paper and Web-based reporting from schools, athletes, parents, researchers, and sport organizations | |||

| Athlete-exposure capture and definition | Direct: Web-based reporting from ATs: athlete-exposure = 1 practice, competition, or performance | Direct Web-based reporting from ATs: athlete-exposure = 1 practice, competition, or performance | Estimated via annual participation statistics from National Federation of State High School Associations and NCAA1,2: athlete-season = 1 athlete sport-season |

| Injury definition | Time loss = 1 day or more and required medical attention | Time loss = 1 day or more and required medical attention | Semipermanent or permanent disability or death |

| Internal organs | No organ-specific body part variables: (1) abdomen (internal), (2) internal injury to chest/thoracic spine/ribs, or (3) other [free-text review] | Variable internal organ injuries included spleen injury, kidney injury, intestinal injury, liver injury, and lung contusion (2009–2010 onward) | Abdomen and chest/thorax organs: kidney, spleen, liver, appendix, pancreas, heart, intestine, stomach, and lung |

| Direct contact mechanism | Contact with another player, contact with playing apparatus, contact with playing surface, and contact with out-of-bounds object | Contact with another player, contact with playing apparatus, contact with playing surface, and contact with out-of-bounds object | 2005–2006 through 2012–2013: Direct contact |

| 2013–2014 through 2015–2016: Contact with another player, contact with playing apparatus, contact with playing surface, or contact with out-of-bounds object | |||

| Exclusions | (1) Abdomen (internal) category that indicated the injury was not internal (eg, sprains, strains, nerve injuries); | Not applicable | Commotio cordis; internal organ injury secondary to other condition such as heatstroke |

| (2) Injuries not seen by medical professional other than AT; | |||

| (3) No diagnostics beyond initial evaluation |

Abbreviations: AT, athletic trainer; NCAA, National Collegiate Athletic Association.

High School RIO

High School RIO is currently the largest HS sports-related injury surveillance system in the United States.31 The methods for HS RIO have been previously described32 and are summarized here as they pertain to this study. Data have been continuously collected for each academic year since 2005–2006, with the sport selection varying by year. Given the rare nature of internal organ injuries, we used the convenience sample of the HS RIO dataset (all 24 sports) for all available years (2005–2006 through 2014–2015). In 2014–2015, a total of 240 schools participated in the HS RIO with a volunteer group of athletic trainers (ATs) providing weekly AE reports (practice, competition, or performance) and injury reports. All information was entered online by the ATs. Injuries were included if they were incurred during an organized practice, competition, or performance; required medical attention; and resulted in participation restriction of 1 or more days.

With regard to outcome inclusion and exclusion criteria, HS RIO does not have organ-specific body part variables. Injuries to body parts other than abdomen (internal), chest/T-spine/ribs, or other were excluded. Injury diagnoses other than internal injury for the body part of chest/T-spine/ribs were excluded. For ATs selecting other body part, free text responses describing the body part injured were assessed and only those responses indicating an organ injury were included. Only injuries resulting from a contact mechanism (contact with another player, contact with a playing apparatus, contact with playing surface, or contact with an out-of-bounds object) were included.

In keeping with these inclusions and exclusions, injury types in the abdominal (internal) category that indicated the injury was not internal were excluded (eg, diagnoses of sprains, strains, nerve injuries). Finally, athletes with injuries who either (1) were not seen by a health care professional (eg, [orthopaedic] physician, physician assistant, nurse practitioner) other than an AT or (2) did not receive assessment beyond evaluation (eg, computed tomography scan, radiographs, laboratory work) were excluded as their conditions were unlikely to be internal organ injuries resulting in time loss from sport participation.

The NCAA-ISP

The NCAA began surveillance for all sponsored sports at its member institutions in 1982. The system evolved from paper-based collection to a Web-based system beginning in 2004–2005. The methods for the NCAA injury surveillance system have been previously described in detail33 and are summarized as they pertain to this study. From 2005–2006 through 2008–2009, a volunteer group of collegiate ATs at participating NCAA member institutions reported AEs (practice, competition, or performance) and injury data in real time via the Web-based platform provided by the NCAA. This included a convenience sample of 25 sports. Injuries from men's and women's swimming were collected only from 2006–2007 through 2008–2009. From 2004–2005 through 2008–2009, the annual average number of teams providing data was 33 per sport (range, 8–84).33 In 2009–2010, the Datalys Center for Sports Injury Research and Prevention, Inc (Indianapolis, IN), assumed management of the system—now referred to as the NCAA-ISP.34 From 2009–2010 through 2014–2015, deidentified data were extracted from existing electronic medical record platforms used by the ATs. Participation in the ISP varies by year and sport. From 2009–2010 through 2014–2015, the annual average number of teams providing data was 14 per sport (range, 2–44). Although men's and women's indoor and outdoor track and field data were collected separately through the study period, indoor and outdoor were combined into men's track and field and women's track and field for reporting purposes. Injuries were included if they resulted from a sponsored practice or competition, received medical attention, and resulted in participation restriction for 1 or more days.

With regard to outcome inclusion and exclusion criteria, both data-collection systems collected 4 specific injuries listed as internal organ injuries: spleen injury, kidney injury, intestinal injury, and liver injury. Beginning in 2009–2010, lung contusion injury data were also collected and included in the analyses.

Injuries not resulting from a contact mechanism (ie, contact with another player, contact with a playing apparatus, contact with the playing surface, or contact with an out-of-bounds object) were excluded. Although the NCAA-ISP from 2009–2010 through 2014–2015 included non–time-loss injuries, only injuries that resulted in removal from play for at least 24 hours were included.

National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research

The NCCSIR has been conducting catastrophic injury and illness surveillance for all sponsored HS and collegiate sports on a national level since 1982.35 Catastrophic sport-related injuries and illnesses are defined as severe events that result in temporary, semipermanent, or permanent disability or death.29,36 An athlete must be a participant in a school-sponsored, organized sport for the catastrophic event to be included. The NCCSIR monitors 42 HS and 35 collegiate sports (including cheer and rodeo).36 It captures events primarily through searches of publicly available sources, including online media reports, news articles, social media, and blogs. Events are also directly reported to NCCSIR via athletes, parents, ATs, school staff, researchers, and sport organizations. Once an event is captured, research staff contact the athletes, parents, and schools to obtain details about the athlete, event, and injury through a brief form or telephone interview or both. Medical examiner or coroner and medical records are also collected when available. All available information sources about the event are reviewed to determine eligibility and classification. In 2013–2014, the NCCSIR expanded to a consortium model with 3 research divisions representing the most frequent types of catastrophic events: Traumatic Injury, Exertional/Environmental, and Cardiac.36 The NCCSIR and division staff work collaboratively on event capture, reporting, and investigation. In January 2015, an online Web-based portal was launched for catastrophic injury reporting; anyone (eg, athletes, parents, ATs) can report catastrophic events at http://www.sportinjuryreport.org. For the current study, catastrophic traumatic injuries resulting directly from the activities of the sponsored sport (practice, competition, performance, conditioning session) were included.

With regard to outcome inclusion and exclusion criteria, traumatic injuries to the following body parts were included: kidney, spleen, liver, appendix, pancreas, heart, intestine, stomach, and lung (Table 1). All injury events to the identified organs were reviewed for inclusion. Injuries to these body parts that were not due to a direct-contact mechanism (such as contact with a person, apparatus, surface, or object) were excluded. Commotio cordis events, though due to direct contact, were not included because these are disruptions of the heart rhythm due to a direct blow to the chest resulting in cardiac arrest.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics included frequencies and percentages. Characteristics of the athlete (sex, level of play), event (sport, event type, mechanism or activity, playing surface), and injury (type, severity, outcome) were described and stratified by data source (HS, collegiate, or NCCSIR) and sport. Incidence rates per 1 000 000 AEs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. High school RIO and the NCAA-ISP collect AEs directly from participating ATs; an AE is defined as 1 athlete participating in 1 school-sanctioned practice, competition, or performance. The NCCSIR does not directly collect AEs and instead uses annual participation statistics from the NFHS37 and NCAA.38 For the NCCSIR, exposure was reported as an athlete-season, which was defined as 1 athlete participating in 1 sport season.

The injury report completed by ATs participating in HS RIO included an item about prevention. For catastrophic injuries, case details were summarized and reviewed to identify the causes and potential countermeasure strategies for injury prevention as defined by Haddon.39

RESULTS

During the 10-year period, 174 direct-contact internal organ injuries were captured across the 3 systems: 124 HS (RIO), 41 NCAA (ISP), 7 HS catastrophic (NCCSIR), and 2 collegiate catastrophic (NCCSIR; Table 2). Most noncatastrophic internal organ injuries occurred among males (RIO = 85%, ISP = 89%), in football (RIO = 65%, ISP = 58%), during competitions (RIO = 67%, ISP = 49%), and due to player-player contact (RIO = 78%, ISP = 68%). The sport activities most associated with player-player contact were tackling/being tackled (RIO = 52/97 [53.6%], ISP = 12/41 [29.3%]) and blocking/being blocked (RIO = 16/97 [16.5%], ISP = 5/41 [12.2%]). Injuries were also due to contact with an apparatus or object (RIO = 12.1%, ISP = 14.6%) or surface (RIO = 9.7%, ISP = 17.1%). Among HS sports, 8 events were due to contact with balls (field hockey = 3, football = 2, and baseball, boys' lacrosse, girls' lacrosse, and girls' soccer = 1 each) and 2 events were due to contact with a stick (boys' lacrosse). Among collegiate sports, 2 events were due to contact with balls (men's lacrosse = 1, women's soccer = 1) and 5 were due to contact with a stick (men's ice hockey = 3, men's lacrosse = 2). Playing surfaces were predominantly grass (RIO = 51.2%, ISP = 48.6%) and turf (RIO = 37.2%, ISP = 35.1%). A majority of internal organ injuries resulted in 1 to 9 days of time loss (RIO = 35.9%, ISP = 33.3%) and a quarter of internal organ injuries were season ending (RIO = 25%, ISP = 23%). Most high school events occurred during competitions (RIO = 66.9%), whereas the majority of collegiate events occurred during practices (ISP = 51.2%).

Table 2.

Athlete, Event, and Injury Characteristics of Internal Organ Injuries Due to Direct-Contact Mechanisms Across 3 Surveillance Systems, 2005–2006 Through 2014–2015, No. (%)

| Characteristic |

High School RIO |

Catastrophic Injuries in High School | Collegiate NCAA ISS/ISP |

Catastrophic Injuries in Collegiate |

| NCCSIR |

NCCSIR |

|||

| Total | 124 (100) | 7 (100) | 41 (100) | 2 (100) |

| Sexa | ||||

| Female | 19 (15.3) | 1 (14.3) | 2 (11.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Male | 105 (84.7) | 6 (85.7) | 16 (89.0) | 2 (100) |

| Levelb | ||||

| Varsity | 82 (70.7) | NA | 41 (100) | 2 (100) |

| Junior varsity | 22 (19.0) | NA | NA | NA |

| Freshman | 7 (6.0) | NA | NA | NA |

| Combined | 5 (4.3) | NA | NA | NA |

| Session | ||||

| Competition | 83 (66.9) | 5 (71.4) | 20 (48.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Practice | 41 (33.1) | 0 (0.0) | 21 (51.2) | 2 (100) |

| Conditioning or other team activity | 0 (0.0) | 2 (28.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Mechanism | ||||

| Contact with player | 97 (78.2) | 6 (85.7) | 28 (68.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Contact with apparatus/object | 15 (12.1) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (14.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Contact with surface | 12 (9.7) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (17.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Contact with other | 0 (0.0) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100) |

| Playing surfacec | ||||

| Grass | 62 (51.2) | NA | 18 (48.6) | NA |

| Turf | 45 (37.2) | NA | 13 (35.1) | NA |

| Wood/court | 8 (6.6) | NA | 2 (5.4) | NA |

| Other | 6 (5.0) | NA | 4 (10.8) | NA |

| Organ | ||||

| Spleen | NA | 4 (57.1) | 8 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Kidney | NA | 1 (14.9) | 19 (33.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Intestine | NA | 0 (0.0) | 4 (7.1) | 1 (50.0) |

| Liver | NA | 1 (14.9) | 4 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Pancreas | NA | 1 (14.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Lung | NA | 0 (0.0) | 6 (10.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Multiple chest organs | NA | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (50.0) |

| Time lossd | ||||

| 1–9 d | 42 (35.9) | NA | 13 (33.3) | NA |

| 10–21 d | 30 (25.9) | NA | 7 (17.9) | NA |

| 22 d or more | 15 (12.9) | NA | 10 (25.6) | NA |

| Season/career ending | 29 (25.0) | 5 (71.5) | 9 (23.1) | 1 (50.0) |

| Outcome | ||||

| Death | 0 (0.0) | 3 (42.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (50.0) |

| Surgerye | 10 (8.2) | NA | 3 (7.3) | NA |

| Disability | NA | 2 (28.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Serious | NA | 2 (28.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (50.0) |

Abbreviations: ISP, Injury Surveillance Program; ISS, Injury Surveillance System; NA, field not collected by the system; NCAA, National Collegiate Athletic Association; NCCSIR, National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research; RIO, Reporting Information Online.

Not collected for NCAA ISP from 2005–2006 through 2008–2009; missing for 23 injuries.

Missing for 8 High School (HS) RIO injuries.

Missing for 3 HS RIO injuries (baseball and softball coded as grass, ice hockey and swimming all coded as other); missing for 4 NCAA-ISP injuries; not collected for NCCSIR.

Missing for 7 HS RIO injuries; missing for 2 NCAA-ISP injuries; not collected for NCCSIR.

Missing for 2 HS RIO injuries; not collected for NCCSIR.

Of the 9 catastrophic internal organ injuries reported to the NCCSIR, most occurred in high school (7/9) and football (7/9) and were due to player-player contact (6/9; Table 2). One event occurred during HS cheer and 1 event during collegiate rodeo (Table 3). Tackling or being tackled was the most common activity associated with internal organ injuries in HS football players (6/7). Internal organ injuries to high school athletes occurred most often during competitions (5/7), whereas all such injuries to collegiate athletes occurred during practices (n = 2). Four catastrophic internal organ injuries resulted in death and 5 resulted in semipermanent or permanent disability.

Table 3.

Incidence Rates per 1 000 000 Athlete-Exposures of Internal Organ Injuries Due to Direct-Contact Mechanisms by Sex-Sport Overall Across 3 Surveillance Systems, 2005–2006 Through 2014–2015

| High School Reporting Information Online |

Catastrophic Injuries in High School NCCSIR |

National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program |

Catastrophic Injuries in Collegiate NCCSIR |

|||||

| n, Athlete-Exposuresa |

Incidence Rate (95% CI) |

n, Athlete-Seasonsb |

Incidence Rate (95% CI) |

n, Athlete-Exposuresa |

Incidence Rate (95% CI) |

n, Athlete-Seasonsb |

Incidence Rate (95% CI) |

|

| Overall total | 124, 35 581 036 | 3.49 (2.87, 4.10) | 7, 70 184 148 | 0.10 (0.03, 0.17) | 41, 11 565 284 | 3.55 (2.46, 4.63) | 2, 4 247 247 | 0.47 (0, 1.12) |

| Contact level | ||||||||

| Contact sportc | 117, 21 860 374 | 5.35 (4.38, 6.32) | 6, 31 054 013 | 0.19 (0.04, 0.35) | 41, 7 508 984 | 5.46 (3.79, 7.13) | 2, 1 768 516 | 1.13 (0, 2.70) |

| Noncontact sport | 7, 13 720 662 | 0.51 (0.13, 0.89) | 1, 39 130 135 | 0.03 (0.00, 0.08) | 0, 4 056 299 | 0.00 | 0, 2 478 731 | 0.00 |

| Incidence rate ratio: contact versus noncontact | 10.49 (4.89, 22.49) | 7.56 (0.91, 62.80) | Not calculated | Not calculated | ||||

| Sport and sex | ||||||||

| Baseball, male | 3, 2 327 774 | 1.29 (0.00, 2.75) | 0, 4 761 189 | 0.00 | 0, 754 852 | 0.00 | 0, 312 162 | 0.00 |

| Basketball | ||||||||

| Male | 1, 3 092 761 | 0.32 (0.00, 0.96) | 0, 5 443 233 | 0.00 | 2, 816 484 | 2.45 (0.00, 5.84) | 0, 174 602 | 0.00 |

| Female | 4, 2 473 363 | 1.62 (0.00, 3.20) | 0, 4 414 491 | 0.00 | 2, 723 717 | 2.76 (0.00, 6.59) | 0, 157 295 | 0.00 |

| Cross-country | ||||||||

| Male | 0, 432 043 | 0.00 | 0, 5 443 233 | 0.00 | 0, 159 413 | 0.00 | 0, 133 757 | 0.00 |

| Female | 0, 381 453 | 0.00 | 0, 2 020 867 | 0.00 | 0, 139 918 | 0.00 | 0, 147 300 | 0.00 |

| Field hockey, female | 3, 652 484 | 4.60 (0.00, 9.80) | 0, 622 908 | 0.00 | 0, 167 362 | 0.00 | 0, 56 925 | 0.00 |

| Football, male | 80, 6 848 953 | 11.68 (9.12, 14.24) | 6, 10 987 849 | 0.55 (0.11, 0.98) | 24, 2 892 878 | 8.30 (4.98, 11.62) | 1, 670 894 | 1.49 (0.00, 4.41) |

| Gymnastics, female | 0, 80 739 | 0.00 | 0, 188 202 | 0.00 | 0, 108 696 | 0.00 | 0, 14 584 | 0.00 |

| Ice hockey | ||||||||

| Male | 2, 409 031 | 4.89 (0.00, 1.67) | 0, 361 725 | 0.00 | 5, 636 863 | 7.85 (0.97, 14.73) | 0, 39 828 | 0.00 |

| Female | NA | NA | 0, 85 508 | 0.00 | 0, 253 455 | 0.00 | 0, 19 878 | 0.00 |

| Lacrosse | ||||||||

| Male | 8, 799 976 | 10.00 (3.07, 16.93) | 0, 911 825 | 0.00 | 3, 384 535 | 7.80 (0.00, 16.63) | 0, 103 130 | 0.00 |

| Female | 1, 583 195 | 1.71 (0.00, 5.08) | 0, 695463 | 0.00 | 0, 291 944 | 0.00 | 0, 81 537 | 0.00 |

| Soccer | ||||||||

| Male | 6, 2 555 908 | 2.34 (0.47, 4.22) | 0, 3 967 236 | 0.00 | 3, 616 346 | 4.87 (0.00, 10.38) | 0, 221 680 | 0.00 |

| Female | 7, 2 208 954 | 3.17 (0.82, 5.52) | 0, 3 560 690 | 0.00 | 2, 725 401 | 2.76 (0.00, 6.58) | 0, 242 747 | 0.00 |

| Softball, female | 1, 1 731 644 | 0.58 (0.00, 1.71) | 0, 3 814 809 | 0.00 | 0, 555 700 | 0.00 | 0, 180 014 | 0.00 |

| Swimming and diving | ||||||||

| Male | 0, 645 392 | 0.00 | 0, 1 269 020 | 0.00 | 0, 207 934 | 0.00 | 0, 89 481 | 0.00 |

| Female | 1, 740 794 | 1.35 (0.00, 4.00) | 0, 1 573 492 | 0.00 | 0, 274 795 | 0.00 | 0, 118 192 | 0.00 |

| Tennis | ||||||||

| Male | 0, 58 997 | 0.00 | 0, 1 582 354 | 0.00 | 0, 72 319 | 0.00 | 0, 88 500 | 0.00 |

| Female | 0, 67 366 | 0.00 | 0, 1 793 908 | 0.00 | 0, 86 214 | 0.00 | 0, 79 595 | 0.00 |

| Track and field | ||||||||

| Male | 0, 1 916 742 | 0.00 | 0, 6 337 247 | 0.00 | 0, 443 037 | 0.00 | 0, 475 854 | 0.00 |

| Female | 0, 1 580 276 | 0.00 | 0, 5 241 506 | 0.00 | 0, 460 966 | 0.00 | 0, 474 617 | 0.00 |

| Volleyball | ||||||||

| Male | 0, 56 208 | 0.00 | 0, 492 098 | 0.00 | NA | NA | 0, 14 585 | 0.00 |

| Female | 1, 2 294 585 | 0.44 (0.00, 1.29) | 0, 4 112 315 | 0.00 | 0, 538 240 | 0.00 | 0, 154 383 | 0.00 |

| Wrestling, male | 5, 2 235 749 | 2.24 (0.28, 4.20) | 0, 2 652 502 | 0.00 | 0, 254 215 | 0.00 | 0, 65 815 | 0.00 |

| Other sports | ||||||||

| Cheerleading | 1, 1 406 649 | 0.71 (0.00, 2.10) | 1, 1 114 880 | 0.90 (0.00, 2.66) | NA | NA | 0, not available | 0.00 |

| Rodeo | NA | NA | 0, NA | 0.00 | NA | NA | 1, NA | Not calculated |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; NA, injuries or exposures for the sport not collected by the system; NCCSIR, National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research.

Reporting Information Online and National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program rates were calculated per 1 000 000 athlete-exposures (competition or practice).

NCCSIR rates were calculated per 1 000 000 athlete-seasons.

Includes basketball, field hockey, football, ice hockey, lacrosse, and soccer.

The internal organs affected were identified in the ISP and NCCSIR systems. The kidney (ISP = 33.9%, NCCSIR = 14.9%) and spleen (ISP = 14.3%, NCCSIR = 57.1%) were the organs affected most often, followed by the lung, intestine, liver, pancreas, and multiple organs (Table 2). Three catastrophic events resulted in injuries to multiple organs and 2 resulted in removal of the injured organ.

Incidence Rates

Over the 10-year period, the overall rate of noncatastrophic internal organ injury per 1 000 000 AEs was similar for the HS (IR = 3.49; 95% CI = 2.87, 4.10) and collegiate (IR = 3.55; 95% CI = 2.46, 4.63; Table 3) levels. High school contact-sport athletes experienced higher rates of both catastrophic and noncatastrophic direct-contact internal organ injuries compared with those in noncontact sports (RIO incidence rate ratio [IRR] = 10.49; 95% CI = 4.89, 22.49; NCCSIR IRR = 7.56; 95% CI = 0.91, 62.80). No catastrophic or noncatastrophic direct-contact internal organ injuries occurred in collegiate-level noncontact sports. The highest rates of injury were in male contact sports: HS football (IR = 11.7; 95% CI = 9.1, 14.2) and lacrosse (IR = 10.0; 95% CI = 3.1, 16.9) in RIO and collegiate football (IR = 8.3; 95% CI = 5.0, 11.6) and ice hockey (IR = 7.9; 95% CI = 1.0, 14.7; Table 3) in the ISP. Other sports with higher IRs were HS boys' wrestling, boys' and girls' soccer, girls' field hockey, and girls' basketball in RIO and collegiate men's and women's soccer in the ISP.

For sex-comparable sports, the rate of direct-contact internal organ injury was higher during competitions than during practices for the following sports: female basketball (IRR = 6.84; 95% CI = 0.71, 65.74) and male lacrosse (IRR = 6.75; 95% CI = 1.36, 33.47) in RIO and male soccer (IRR = 7.39; 95% CI = 0.67, 81.47), female soccer (IRR = 3.12; 95% CI = 0.19, 49.84), male basketball (IRR = 3.84; 95% CI = 0.24, 61.36), female basketball (IRR = 3.45; 95% CI = 0.22, 55.20), and male lacrosse (IRR = 5.35; 95% CI = 1.08, 26.51; Supplemental Table 2 (95.8KB, pdf) ) in the ISP. All noncatastrophic direct-contact internal organ injuries occurred during competitions in RIO: HS boys' and girls' soccer, boys' basketball, and softball. Rates were not substantively different in practices versus competitions for HS baseball, softball, boys' basketball, and girls' lacrosse. Due to low injury counts, these estimates were imprecise, as illustrated by the wide CIs.

For sex-comparable sports, the rate of noncatastrophic direct-contact internal organ injury was lower among boys' HS sports during competitions compared with girls' HS sports for soccer (IRR = 0.75; 95% CI = 0.25, 2.24), basketball (IRR = 0.27; 95% CI = 0.03, 2.60), and baseball and softball (IRR = 0.73; 95% CI = 0.05, 11.66; Supplemental Table 2 (95.8KB, pdf) ). During practices, the rate of direct-contact internal organ injury was higher among HS boys' lacrosse players compared with their female counterparts (IRR = 1.45; 95% CI = 0.13, 16.01). Conversely, the rate of noncatastrophic internal organ injury was higher among collegiate men's athletes during competition compared with their women counterparts for soccer (IRR = 2.68; 95% CI = 0.24, 29.60). Due to low injury counts, these estimates were imprecise, as illustrated by the wide CIs.

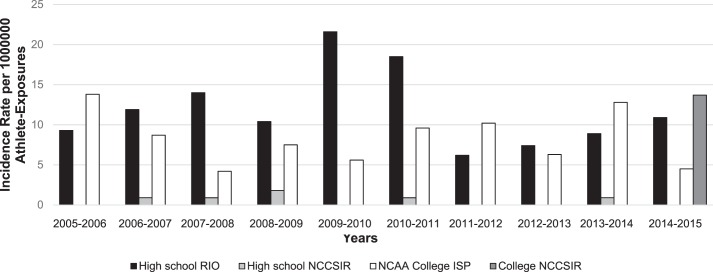

Incidence-rate trends over the 10-year period were examined for football (Figure, Supplemental Table 3 (95.8KB, pdf) ). The RIO HS football IRs per 1 000 000 AEs ranged from a high of 21.6 in 2009–2010 (14 events) to a low of 6.2 in 2011–2012 (4 events). The ISP collegiate football IRs per 1 000 000 AEs ranged from a high of 13.77 in 2005–2006 (6 events) to a low of 4.24 in 2007–2008 (2 events). Catastrophic injury rates per 1 000 000 athlete-seasons in HS football did not substantially change over the 10-year period (range, 0 to 1.80 per 1 000 000 athlete-seasons) and only 1 catastrophic injury occurred in collegiate football in 2014–2015 (IR = 13.7 per 1 000 000 athlete-seasons).

Figure.

Football-related incidence rates of internal organ injuries due to direct-contact mechanisms per 1 000 000 athlete-exposures by year by surveillance system, 2005–2006 through 2014–2015. Note: See Supplemental Table 3 (95.8KB, pdf) for n, participants, and 95% confidence intervals. Reporting Information Online (RIO) and National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Injury Surveillance Program rates are calculated per 1 000 000 athlete-exposures; National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research (NCCSIR) rates are per 1 000 000 athlete-seasons.

Additional Details and Prevention Measures

Details for all 9 catastrophic injuries and corresponding Haddon injury-prevention countermeasure strategies are presented in Table 4. Two HS football deaths were the result of the athlete (wide receiver and offensive tight end) being tackled by 2 players—1 from each side. A HS cheerleader flier was fatally injured after a basket toss when she underrotated during a flip and was caught on her stomach. A collegiate rodeo participant was injured during practice when the bull he was riding stepped on his chest; he died from his injuries, despite wearing a chest protector.

Table 4.

Descriptions of 9 Catastrophic Internal Organ Injuries Due to Direct-Contact Mechanisms in High School and Collegiate Organized Sports and Associated Haddon Energy-Damage Countermeasures, the National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research, 2005–2006 Through 2014–2015a Continued on Next Page

| Level |

Sport |

Severity |

Player Position |

Activity, Player Action |

Narrative |

Countermeasures |

| High school | Cheerleading | Death | Flier | Practice, basket toss | A female freshman high school cheerleader aged 14 years sustained an injury during practice. She did not rotate enough in the air while flipping and was caught on her stomach instead of her back. She complained of abdominal pain and difficulty breathing shortly before collapsing. She was transported by emergency medical services (EMS) to the hospital where she later died. Cause of death: ruptured spleen that led to internal bleeding. | 4. Modify the rate or special distribution of the hazard from its source (use padded landing surfaces when practicing new skills) |

| 9. Move rapidly to detect and evaluate the damage and counter its continuation and extension (implement emergency action plan and access to advanced medical care onsite) | ||||||

| 10. Stabilize, repair, and rehabilitate the damage or injured person (provide advanced trauma care) | ||||||

| High school | Football | Recovery | Running back | Game, being tackled | A male senior high school player was returning a kickoff during a game when he was hit by an opposing player, injuring his spleen. He continued to play the remainder of the game. He later collapsed in the locker room after the game and was immediately attended to by an athletic trainer. He was transported by EMS via ambulance to the hospital. He later underwent surgery to have his spleen removed. A full recovery was expected. | 4. Modify the rate or special distribution of the hazard from its source (decrease closing distance on kickoffs) |

| 9. Move rapidly to detect and evaluate the damage and counter its continuation and extension (implement emergency action plan and access to advanced medical care onsite) | ||||||

| 10. Stabilize, repair, and rehabilitate the damage or injured person (provide advanced trauma care) | ||||||

| High school | Football | Death | Offensive (tight) end | Game, being tackled | A male senior high school player aged 18 years was injured in a game when he was hit from the front and the back while being tackled. He immediately was transported to the hospital where damage to his spleen and small intestines was found. He underwent surgery a few days after the injury but died about a month later due to complications. | 6. Separate the hazard and what is to be protected by a material barrier (use protective gear such as flak jacket) |

| 9. Move rapidly to detect and evaluate the damage and counter its continuation and extension (implement emergency action plan and access to advanced medical care onsite) 10. Stabilize, repair, and rehabilitate the damage or injured person (provide advanced trauma care) | ||||||

| High school | Football | Recovery | Defensive back | Scrimmage, being tackled | A male freshman high school player aged 14 years sustained a hit to his right side during a scrimmage game (shoulder to his stomach). He was attended to by athletic trainers but collapsed a short time after. He was transported to the hospital by EMS in an ambulance before undergoing surgery to remove his injured right kidney. A full recovery was expected. | 6. Separate the hazard and what is to be protected by a material barrier (use protective gear such as flak jacket) |

| 9. Move rapidly to detect and evaluate the damage and counter its continuation and extension (implement emergency action plan and access to advanced medical care onsite) | ||||||

| 10. Stabilize, repair, and rehabilitate the damage or injured person (provide advanced trauma care) | ||||||

| High school | Football | Death | Wide receiver | Game, being tackled | A male sophomore high school player aged 15 years was catching a ball over his head when he was hit by 2 other players during a junior varsity game. He walked off the field before collapsing on the sideline. He was transported to the hospital but died the next day of internal injuries to his liver. | 6. Separate the hazard and what is to be protected by a material barrier (use protective gear such as flak jacket) |

| 9. Move rapidly to detect and evaluate the damage and counter its continuation and extension (implement emergency action plan and access to advanced medical care onsite) | ||||||

| 10. Stabilize, repair, and rehabilitate the damage or injured person (provide advanced trauma care) | ||||||

| High school | Football | Recovery | Quarterback | Game, being tackled | A male sophomore high school player was tackled during a game that resulted in a lacerated pancreas. He returned to the game but was taken to the hospital a few days later after becoming ill. He underwent surgery on his pancreas. A full recovery was expected. | 9. Move rapidly to detect and evaluate the damage and counter its continuation and extension (implement emergency action plan and access to advanced medical care onsite) |

| 10. Stabilize, repair, and rehabilitate the damage or injured person (provide advanced trauma care) | ||||||

| High school | Football | Recovery | Running back | Game, being tackled | A male high school player aged 15 years was injured during a tackle on kickoff return. The athletic trainer examined him and thought it was a cracked rib. His pain increased and his parents took him to the hospital. Injuries included a ruptured spleen, lacerated kidney, and punctured lung. A full recovery was expected. | 4. Modify the rate or special distribution of the hazard from its source (decrease closing distance on kickoffs) |

| 6. Separate the hazard and what is to be protected by a material barrier (use protective gear such as flak jacket) | ||||||

| 9. Move rapidly to detect and evaluate the damage and counter its continuation and extension (implement emergency action plan and access to advanced medical care onsite) | ||||||

| 10. Stabilize, repair, and rehabilitate the damage or injured person (provide advanced trauma care) | ||||||

| College | Rodeo | Death | Does not apply | Practice, bull riding | A male college sophomore player aged 20 years was killed during practice after a bull stepped directly on his chest. The athlete was wearing all required safety gear, including a chest protector and mouth guard, at the time of the incident. Cause of death: blunt force trauma to the chest. | 6. Separate the hazard and what is to be protected by a material barrier (use protective gear such as chest protector) |

| 9. Move rapidly to detect and evaluate the damage and counter its continuation and extension (implement emergency action plan and access to advanced medical care onsite) | ||||||

| 10. Stabilize, repair, and rehabilitate the damage or injured person (provide advanced trauma care) | ||||||

| College | Football | Recovery | Safety | Practice, general play | A male senior college player fractured a rib during practice that resulted in a bowel injury. He underwent treatment at the hospital. A full recovery was expected. | 9. Move rapidly to detect and evaluate the damage and counter its continuation and extension (implement emergency action plan and access to advanced medical care onsite) |

| 10. Stabilize, repair, and rehabilitate the damage or injured person (provide advanced trauma care) |

Haddon W Jr. Energy damage and the ten countermeasure strategies. J Trauma. 1973;13(4):321–331.

The injury report completed by ATs participating in HS RIO included an item about prevention. The ATs in 25.0% of cases (n = 31) noted that they believed additional or more appropriate use of protective equipment could have prevented or reduced the severity of the injury. In 65.3% of cases (n = 81), they stated that additional or more appropriate use of protective equipment could not have prevented or reduced the severity of the injury, and in 9.7% (n = 12), they responded that it was unknown. The most commonly reported personal protective equipment that might have helped were flak jackets or rib protectors, which were mentioned by 27 of the 31 ATs (87.1%) who believed that additional or more appropriate use of protective equipment could have prevented or reduced the severity of the injury. The ATs participating in the ISP were not surveyed on this item.

DISCUSSION

In 2014, little published research on sport-related internal organ injuries compared with other injuries was available.40 Timely and reliable surveillance data on the incidence, characteristics, and severity of sport-related injuries is important to make informed decisions about prevention measures. Our findings support the rarity of sport-related, direct-contact internal organ injuries, which occurred predominantly in the male contact sports of football, lacrosse, ice hockey, and soccer; the female contact sports of field hockey and soccer; and wrestling. Injuries were more frequent during competitions compared with practices and were often due to player-player contact. Most internal organ injuries were not severe, with more than 50% of athletes returning to sport participation within 21 days; however, a quarter of injuries were season ending. Only 9 catastrophic internal organ injuries occurred during the 10-year period, most of which were in HS football; fewer than half (4/9) resulted in death.

Overall Numbers and Rates

Although 3 times as many internal organ injuries were reported at the HS level (n = 124) compared with the collegiate level (n = 41), the overall IRs of internal organ injuries in this study did not differ between the high school and collegiate levels (3.49 and 3.55 per 1 000 000 AEs, respectively). National cross-sectional surveys conducted from 1999 through 2008 indicated life-threatening, sport-related internal organ injuries were more frequent among 13- to 18-year-olds than those more than 18 years old20; however, the older group included individuals beyond college age. A previous study18 of national trauma-registry–data showed that patients 15 to 18 and 12 to 14 years old had equal frequencies of sport-related internal organ injuries. Analyses of regional trauma-registry data provided sport-related internal organ injury IRs for children ages 5 to 18 years using census data: 6.9 kidney and 5.6 spleen injuries per 1 000 000 children.19 Though these rates were higher than the rates we observed, our ability to compare rates was hampered by methodologic differences between the studies: only kidney and spleen injuries were included in the previous study, age ranges varied, injury data sources were different (hospital records versus school AT surveillance reports), athlete status was known in the surveillance data and unknown in the trauma registry, and trauma-registry denominators were per child and represented the general population rather than the population participating in the sport.

Internal Organ Versus Other Injuries

Compared with other sport-related injuries, internal organ injuries are infrequent events. Research20 suggested that 14% of life-threatening injuries seen in the emergency department from 1999–2008 were sport related, and of these, only 5.4% involved the torso or abdomen. Furthermore, 39% of life-threatening, sport-related injuries were among US children aged 13 to 18 years, which translates to 333 000 life-threatening, sport-related injuries, of which 17 982 (1798 per year) involved the torso or abdomen.20 Regarding fatal football injuries at the HS and collegiate levels, 3 of 79 (3.7%) direct traumatic injury deaths from 1990–2010 were due to intra-abdominal injuries.41 We reported 9 catastrophic or life-threatening events captured over the 10-year period by the NCCSIR, the majority of which were in football players (7/9). Of these, 4 resulted in death. In-depth review of the catastrophic cases and Haddon39 countermeasure strategies highlighted the importance of early recognition and prompt medical evaluation and treatment to ensure the best possible outcome. Emergency action plans, access to ATs, and on-site emergency medical services for sport competitions at higher risk for direct-contact injury constitute best-practice strategies for these injuries.42,43

The current study included both severe and less severe internal organ injuries. The ISP and NCCSIR data support previous research15,18,19 demonstrating that the kidney and spleen were the internal organs injured most often. Anatomically, the kidneys are retroperitoneal and protected by the ribs, which, if fractured, can lacerate the kidneys. They are also susceptible to direct blows, particularly in adolescents, who have a greater percentage of mass below the level of rib protection along with less developed musculature, rendering them more susceptible to injury.44 During contact sports, an enlarged spleen from an unidentified, underlying illness (eg, mononucleosis) may be injured, emphasizing the importance of symptom reporting and diagnosis and removal from sport-specific contact until the athlete has recovered.

Type of Sport, Mechanism, and Activity

It is not surprising that contact sports had higher rates of direct-contact internal organ injuries than noncontact sports. In our study, football, male ice hockey, and male lacrosse in HS and college were the sports with the highest rates. Previous trauma-registry, hospital, and surveillance research supports these sport-specific findings for football,16,18,19,21 ice hockey,15,16,18,19 and soccer.15,21 Though wrestling was not classified in this study as a contact sport, HS wrestlers had a rate equivalent to that of male HS soccer players. Eighty percent of wrestling injuries were a result of take-down maneuvers. Overall, most injuries were due to player-player contact, but contact with an apparatus, surface, or object was also noted. Among HS sports, 8 events were due to contact with balls. Identifying whether player-player contact was intentional or unintentional and the specific apparatus, surface, or object is also important for prevention.

Prevention

A better understanding of the activity and mechanism of injury, the source and location of contact, and protective gear worn may be helpful in determining whether the injury could have been prevented. Athletic trainers' reports to HS RIO indicated that in their opinions, additional protective equipment could have prevented injury in 25% of patients. For example, football shoulder pads were designed to protect the shoulder, chest, and upper rib cage but not the lower rib cage and abdominal area. Using protective gear (eg, padded belt or shirt) that extends beyond the bottom of the shoulder pads and covers the torso may have a role in protecting internal organs from direct contact. Further research on the use and effects of protective equipment for internal injury prevention are needed. Education and information about internal organ injuries, mechanisms of injury, and types of protective equipment available are important to ensure that athletes and parents can make informed decisions.40

Whereas primary prevention measures will reduce the likelihood of an event occurring, secondary prevention may help to limit the potential severity associated with internal organ injuries. Early recognition and serial follow-up of patients with suspected internal organ injuries may reduce the severity of injury. This may require medical staff to be present at high-risk events and to be available at the time of the injury. Best practices for preventing sudden death and severe injury include emergency action plans and availability of ATs.42 Colleges and universities have staff ATs who are on-site for competitions and the majority of practices, whereas 70% of public HSs have access to an AT; of those, only 47% have ATs present at both competitions and practices.45

Strengths and Limitations

All 3 surveillance systems have been in operation for 10 or more years—2 since 1982—and the data are disseminated annually and used by national sport bodies and medical organizations. Athlete status is known, as are the specific sport, level of participation (HS, college), and other details such as the injury mechanism, activity at time of injury, and playing position, which are critical for identifying potential prevention measures. The RIO and ISP rely on ATs for injury data collection and AE tracking, which translates to accurate, high-quality data for both descriptive and comparative analyses. The data quality of the RIO and ISP systems has been previously evaluated.46,47 The RIO and ISP do not collect identifiers, whereas the NCCSIR does. Results were provided separately for each system for this reason.

Despite these strengths, the following limitations should be noted. First, both the HS RIO and collegiate ISP surveillance systems use convenience samples of schools with ATs who voluntarily report injury and exposure data. Internal organ injuries are rare events in sport; consequently, generalizing these study results beyond the sample to schools without ATs or non-NCAA schools or organizations (eg, National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics or junior colleges) should be done cautiously. National trauma registries18 and surveys such as the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey20 have the advantage of broader and more representative coverage; however, athlete status, sport level, and the number of athlete participants at risk (rate denominator data) are unknown in these sources. Athlete status is known in all 3 systems, and both HS RIO and the ISP directly collect AE data, whereas the NCCSIR uses sport participation estimates from the NFHS and NCAA.37,38

Second, the injury definitions in each of the systems were slightly different. The specific internal organ affected (eg, spleen, kidney) was classified in collegiate ISP and NCCSIR data sources. However, RIO data fields did not identify injury to the specific internal organ beyond the abdomen or chest, rib, or thorax region in general. Thus, injuries may be misclassified within the RIO dataset. To decrease the likelihood of misclassification, injuries reported to RIO that did not require medical evaluation beyond the AT or specific diagnostics were excluded. However, this exclusionary provision may miss less severe internal organ injuries, which would result in an underestimate of the injury frequency and rate.

Third, the NCCSIR data source relies predominantly on media reports for event capture.36 It is possible that internal organ injuries that did not result in death or permanent disability were not covered by the media and therefore were not captured by the NCCSIR. The online portal (http://www.sportinjuryreport.org) that allows anyone to report catastrophic injuries should improve future capture of these events. Increasing awareness and use of this portal is critical for obtaining accurate numbers on the burden and incidence of these and other catastrophic injuries.

Last, use of protective gear at the time of the injury was not reported. With the exception of the fatal injury in collegiate rodeo, whether protective equipment could have prevented the injury is unknown. Future researchers who collect information on protective equipment worn by all athletes may be able to determine whether the equipment reduces the frequency of internal organ injuries.

CONCLUSIONS

Direct-contact internal organ injuries happen infrequently, yet when they occur, they may result in severe outcomes. These findings suggest that early recognition and a better understanding of the activities associated with the injury event and use or nonuse of protective equipment is needed. Given the potential severity of these injuries, further research into all potential preventive measures is warranted. Our findings also indicate that preventive strategies will vary by the sport, level of play, and playing position.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

High School RIO has received generous research funding contributions from the National Federation of State High School Associations (Indianapolis, IN), the National Operating Committee on Standards for Athletic Equipment (Overland Park, KS), and DJO LLC (Vista, CA) as well as funding via Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, GA) grants R49/CE000674-01 and R49/CE001172-01. The content of this report is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or any of the other institutions that provided financial support for this research. The NCAA-ISP data were provided by the Datalys Center for Sports Injury Research and Prevention, Inc (Indianapolis, IN). The ISP was funded by the NCAA (Indianapolis, IN). The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NCAA. The NCCSIR (Chapel Hill, NC) is funded by the following organizations: the American Football Coaches Association (Waco, TX), the National Athletic Trainers' Association (Carrollton, TX), the NCAA, the National Federation of State High School Associations, the National Operating Committee on Standards for Athletic Equipment, and the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine (Leawood, KS).

We acknowledge former NCCSIR Director Dr Frederick O. Mueller, PhD; HS RIO, NCAA-ISP, and NCCSIR staff members; and members of the Consortium for Catastrophic Injury Monitoring in Sport. We also thank the ATs, athletes, families, coaches, and others who have participated in this research and have shared information with the 3 surveillance systems. We thank the many ATs who have volunteered their time and efforts to submit data to HS RIO and the NCAA-ISP.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental Tables (95.8KB, pdf) . Published studies on sport-related internal organ injuries before 2014 data request; direct-contact internal organ injury incidence rates by sex-comparable sports; and contact-mechanism internal organ injury incidence rates in football by year.

Found at DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-271-17.S1

REFERENCES

- 1.Thacker SB. Editorial: public health surveillance and the prevention of injuries in sports: what gets measured gets done. J Athl Train. 2007;42(2):171–172. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thacker SB, Berkelman RL. Public health surveillance in the United States. Epidemiol Rev. 1988;10:164–190. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Mechelen W, Hlobil H, Kemper HC. Incidence, severity, aetiology and prevention of sports injuries: a review of concepts. Sports Med. 1992;14(2):82–99. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199214020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marshall SW, Guskiewicz KM. Sports and recreational injury: the hidden cost of a healthy lifestyle [editorial] Inj Prev. 2003;9(2):100–102. doi: 10.1136/ip.9.2.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langley J, Cryer C. A consideration of severity is sufficient to focus our prevention efforts. Inj Prev. 2012;18(2):73–74. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2011-040278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson BK, Comstock RD. Epidemiology of chest, rib, thoracic spine, and abdomen injuries among United States high school athletes, 2005/06 to 2013/14. Clin J Sport Med. 2017;27(4):388–393. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Houshian S. Traumatic duodenal rupture in a soccer player. Br J Sports Med. 2000;34(3):218–219. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.34.3.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Idriz S, Abbas A, Sadigh S, Padley S. Pulmonary laceration secondary to a traumatic soccer injury: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(11):1625.e1–1625.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Milton AE, Hansen PJ, Miller KC, Rhee YS. Grade III liver laceration in a female volleyball player. Sports Health. 2013;5(2):150–152. doi: 10.1177/1941738112451429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ray R, Lemire JE. Liver laceration in an intercollegiate football player. J Athl Train. 1995;30(4):324–326. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stricker PR, Hardin BH, Puffer JC. An unusual presentation of liver laceration in a 13-yr-old football player. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25(6):667–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holmes FC, Hunt JJ, Sevier TL. Renal injury in sport. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2003;2(2):103–109. doi: 10.1249/00149619-200304000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Intravia JM, DeBerardino TM. Evaluation of blunt abdominal trauma. Clin Sports Med. 2013;32(2):211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Styn NR, Wan J. Urologic sports injuries in children. Curr Urol Rep. 2010;11(2):114–121. doi: 10.1007/s11934-010-0098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergqvist D, Hedelin H, Karlsson G, Lindblad B, Matzsch T. Abdominal injury from sporting activities. Br J Sports Med. 1982;16(2):76–79. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.16.2.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerstenbluth RE, Spirnak JP, Elder JS. Sports participation and high grade renal injuries in children. J Urol. 2002;168(6):2575–2578. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64219-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McAleer IM, Kaplan GW, LoSasso BE. Renal and testis injuries in team sports. J Urol. 2002;168(4, pt 2):1805–1807. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000028021.97382.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wan J, Corvino TF, Greenfield SP, DiScala C. Kidney and testicle injuries in team and individual sports: data from the National Pediatric Trauma Registry. J Urol. 2003;170(4, pt 2):1528–1533. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000083999.16060.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wan J, Corvino TF, Greenfield SP, DiScala C. The incidence of recreational genitourinary and abdominal injuries in the Western New York pediatric population. J Urol. 2003;170(4, pt 2):1525–1527. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000084430.96658.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meehan WP, III, Mannix R. A substantial proportion of life-threatening injuries are sport-related. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29(5):624–627. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31828e9cea. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grinsell MM, Butz K, Gurka MJ, Gurka KK, Norwood V. Sport-related kidney injury among high school athletes. Pediatrics. 2012;130(1):e40–e45. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brophy RH, Gamradt SC, Barnes RP, et al. Kidney injuries in professional American football: implications for management of an athlete with 1 functioning kidney. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(1):85–90. doi: 10.1177/0363546507308940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meehan WP, III, d'Hemencourt P, Comstock R. High school concussions in the 2008–2009 academic year: mechanism, symptoms, and management. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(12):2405–2409. doi: 10.1177/0363546510376737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Currie DW, Fields SK, Patterson MJ, Comstock RD. Cheerleading injuries in United States high schools. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1) doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Darrow CJ, Collins CL, Yard EE, Comstock RD. Epidemiology of severe injuries among United States high school athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:1798–1805. doi: 10.1177/0363546509333015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kerr ZY, Collins CL, Fields SK, Comstock RD. Epidemiology of player-player contact injuries among US high school athletes, 2005–2009. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2011;50(7):594–603. doi: 10.1177/0009922810390513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kerr ZY, Marshall SW, Dompier TP, Corlette J, Klossner DA, Gilchrist J. College sports-related injuries—United States, 2009–10 through 2013–14 academic years. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(48):1330–1336. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6448a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kay MC, Register-Mihalik JK, Gray AD, Djoko A, Dompier TP, Kerr ZY. The Epidemiology of severe injuries sustained by National Collegiate Athletic Association student-athletes, 2009–2010 through 2014–2015. J Athl Train. 2017;52(2):117–128. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-52.1.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mueller FO, Cantu RC. Catastrophic injuries and fatalities in high school and college sports, fall 1982–spring 1988. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1990;22(6):737–741. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199012000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kucera KL, Yau RK, Register-Mihalik J, et al. Traumatic brain and spinal cord fatalities among high school and college football players—United States, 2005–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;65(52):1465–1469. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6552a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.High school RIO: Reporting Information Online. University of Colorado Denver Web site. 2017 http://www.ucdenver.edu/academics/colleges/PublicHealth/research/ResearchProjects/piper/projects/RIO/Pages/default.aspx Accessed May 24.

- 32.Comstock RD, Currie DW, Pierpoint LA. Convenience Sample Summary Report: National High School Sports-Related Injury Surveillance Study, 2014–2015 School Year. Denver, CO: Colorado School of Public Health; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kerr ZY, Dompier TP, Snook EM, et al. National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System: review of methods for 2004–2005 through 2013–2014 data collection. J Athl Train. 2014;49(4):552–560. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-49.3.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.NCAA Injury Surveillance Program. Datalys Center for Sports Injury Research and Prevention Web site. 2017 http://www.datalyscenter.org/ncaa-injury-surveillance-program Accessed May 24.

- 35.National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research (NCCSIR) Web site. 2017 http://nccsir.unc.edu/about/ Accessed May 24.

- 36.Kucera KL, Yau RK, Thomas L, Wolff C, Cantu RC. Catastrophic Sports Injury Research Thirty-Third Annual Report, Fall 1982–Spring 2015. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina, The National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sport participation statistics. National Federation of State High School Associations Web site. 2018 https://www.nfhs.org/articles/high-school-sports-participation-increases-for-28th-straight-year-nears-8-million-mark Accessed February 20.

- 38.Sports sponsorship and participation research. National Collegiate Athletic Association Web site. 2017 http://www.ncaa.org/about/resources/research/sports-sponsorship-and-participation-research Accessed April 1.

- 39.Haddon W., Jr Energy damage and the ten countermeasure strategies. Hum Factors. 1973;15(4):355–366. doi: 10.1177/001872087301500407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.The next concussion? Internal injuries are youth sport danger. NBC News Web site. 2018 https://www.nbcnews.com/health/kids-health/next-concussion-internal-injuries-are-youth-sport-danger-n181846 Accessed February 24.

- 41.Boden BP, Breit I, Beachler JA, Williams A, Mueller FO. Fatalities in high school and college football players. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(5):1108–1116. doi: 10.1177/0363546513478572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Casa DJ, Guskiewicz KM, Anderson SA, et al. National Athletic Trainers' Association position statement: preventing sudden death in sports. J Athl Train. 2012;47(1):96–118. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-47.1.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Casa DJ, Almquist J, Anderson SA, et al. The Inter-Association Task Force for Preventing Sudden Death in Secondary School Athletics Programs: best-practices recommendations. J Athl Train. 2013;48(4):546–553. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-48.4.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prentice WE. Principles of Athletic Training: A Guide to Evidence-Based Clinical Practice 16th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pryor RR, Casa DJ, Vandermark LW, et al. Athletic training services in public secondary schools: a benchmark study. J Athl Train. 2015;50(2):156–162. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-50.2.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yard EE, Collins CL, Comstock RD. A comparison of high school sports injury surveillance data reporting by certified athletic trainers and coaches. J Athl Train. 2009;44(6):645–652. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-44.6.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kucera KL, Marshall SW, Bell DR, DiStefano MJ, Goerger CP, Oyama S. Validity of soccer injury data from the National Collegiate Athletic Association's Injury Surveillance System. J Athl Train. 2011;46(5):489–499. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.5.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.