Abstract

Background

Individual counselling from a smoking cessation specialist may help smokers to make a successful attempt to stop smoking.

Objectives

The review addresses the following hypotheses:

1. Individual counselling is more effective than no treatment or brief advice in promoting smoking cessation. 2. Individual counselling is more effective than self‐help materials in promoting smoking cessation. 3. A more intensive counselling intervention is more effective than a less intensive intervention.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialized Register for studies with counsel* in any field in May 2016.

Selection criteria

Randomized or quasi‐randomized trials with at least one treatment arm consisting of face‐to‐face individual counselling from a healthcare worker not involved in routine clinical care. The outcome was smoking cessation at follow‐up at least six months after the start of counselling.

Data collection and analysis

Both authors extracted data in duplicate. We recorded characteristics of the intervention and the target population, method of randomization and completeness of follow‐up. We used the most rigorous definition of abstinence in each trial, and biochemically‐validated rates where available. In analysis, we assumed that participants lost to follow‐up continued to smoke. We expressed effects as a risk ratio (RR) for cessation. Where possible, we performed meta‐analysis using a fixed‐effect (Mantel‐Haenszel) model. We assessed the quality of evidence within each study using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool and the GRADE approach.

Main results

We identified 49 trials with around 19,000 participants. Thirty‐three trials compared individual counselling to a minimal behavioural intervention. There was high‐quality evidence that individual counselling was more effective than a minimal contact control (brief advice, usual care, or provision of self‐help materials) when pharmacotherapy was not offered to any participants (RR 1.57, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.40 to 1.77; 27 studies, 11,100 participants; I2 = 50%). There was moderate‐quality evidence (downgraded due to imprecision) of a benefit of counselling when all participants received pharmacotherapy (nicotine replacement therapy) (RR 1.24, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.51; 6 studies, 2662 participants; I2 = 0%). There was moderate‐quality evidence (downgraded due to imprecision) for a small benefit of more intensive counselling compared to brief counselling (RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.53; 11 studies, 2920 participants; I2 = 48%). None of the five other trials that compared different counselling models of similar intensity detected significant differences.

Authors' conclusions

There is high‐quality evidence that individually‐delivered smoking cessation counselling can assist smokers to quit. There is moderate‐quality evidence of a smaller relative benefit when counselling is used in addition to pharmacotherapy, and of more intensive counselling compared to a brief counselling intervention.

Plain language summary

Does individually‐delivered counselling help people to stop smoking?

Background

Individual counselling is commonly used to help people who are trying to quit smoking. The review looked at trials of counselling by a trained therapist providing one or more face‐to‐face sessions, separate from medical care. The outcome was being a non smoker at least six months later.

Study characteristics

We searched for trials in May 2016 and identified 49 trials Inlcuding around 19,000 participants. All the trials involved one or more face‐to‐face counselling sessions lasting at least 10 minutes, but most were much longer. Many also included further telephone contact for additional support. Thirty‐three of the trials compared individual counselling to a control group that only had minimal support, which could be usual care, brief advice about stopping smoking, or written materials. Of these, 27 did not offer any medication such as nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), which also helps people stop. Six of the 33 provided NRT or other medication to everyone in the trial. Twelve studies compared more intensive to less intensive counselling, and five compared different types of counselling.

Results and quality of evidence

Combining the results of the studies showed that having individual counselling could increase the chance of quitting by between 40% and 80%, compared to minimal support. This means that if seven out of 100 smokers managed to quit for at least six months using the sort of brief support given to the control groups, then between 10 and 12 in 100 would be expected to be successful after having counselling. We judged the quality of this evidence to be high. If everyone also had NRT or other medication, and 11 in 100 could quit in the control group, between 11 and 16 in 100 would be expected to be successful with the addition of counselling. We assessed this evidence as being of moderate quality, because the size of benefit was less certain. Having more intensive counselling support, for example more sessions, probably helps more, but the additional benefit is likely to be small, and again was of moderate quality because the size of benefit was uncertain. The few studies that compared different types of counselling did not show any differences between them.

Summary of findings

Background

Psychological interventions to aid smoking cessation include self‐help materials, brief therapist‐delivered interventions such as advice from a physician or nurse, intensive counselling delivered on an individual basis or in a group, and combinations of these approaches. Previous reviews have shown a small but consistent effect of brief, therapist‐delivered interventions (Stead 2013a). The effect of self‐help interventions is less clear (Hartmann‐Boyce 2014). More intensive intervention in a group setting increases quit rates (Stead 2017).

In this review, we assess the effectiveness of more intensive counselling delivered by a smoking cessation counsellor to a person on a one‐to‐one basis. One problem in assessing the value of individual counselling is that of confounding with other interventions. For example, counselling delivered by a physician in the context of a clinical encounter may have different effects from that provided by a non‐clinical counsellor. One approach to this problem is to employ statistical modelling (logistic regression) to control for possible confounders, an approach used by the US Public Health Service in preparing clinical practice guidelines (AHCPR 1996; Fiore 2000; Fiore 2008). An alternative approach is to review only unconfounded interventions. This is the approach we have adopted in the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Review Group. We therefore specifically exclude from this review counselling provided by doctors or nurses during the routine clinical care of the patient, and focus on smoking cessation counselling delivered by specialist counsellors. We define counselling broadly, based only on a minimum time spent in contact with the smoker, not according to the use of any specific behavioural approach.

Objectives

The review addresses the following hypotheses:

1. Individual counselling is more effective than no treatment or brief advice in promoting smoking cessation. 2. Individual counselling is more effective than self‐help materials in promoting smoking cessation. 3. A more intensive counselling intervention is more effective than a less intensive intervention.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized or quasi‐randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with a minimum follow‐up of six months, where at least one treatment arm consisted of an unconfounded intervention from a counsellor. Studies in which the treatment arm combined counselling and pharmacotherapy, and the control condition had neither, are covered in a separate review (Stead 2016).

Types of participants

Any smokers, except pregnant women (smoking cessation interventions in pregnancy are addressed by a separate review, Chamberlain 2013). We also exclude trials recruiting only children and adolescents.

Types of interventions

We defined individual counselling as a face‐to‐face encounter between a smoker and a counsellor trained in assisting smoking cessation. This review specifically excludes studies of counselling delivered by doctors and nurses as part of clinical care, which are covered in separate reviews (Rice 2013; Stead 2013a). It also excludes studies of interventions that combined counselling with provision of pharmacotherapy, compared to brief support (Stead 2016), studies of motivational interviewing (Lindson‐Hawley 2015) and interventions which address multiple risk factors in addition to smoking. We include studies that evaluate the effect of counselling as an addition to pharmacotherapy.

We include studies comparing different counselling approaches if they are not covered by other Cochrane Reviews of specific interventions. Comparisons between individual counselling and behavioural therapy conducted in groups are covered in the Cochrane Review of group behavioural therapy (Stead 2017).

Types of outcome measures

The outcome was smoking cessation at the longest reported follow‐up. We used sustained abstinence where available, or multiple point prevalence. We included studies using self‐report with or without biochemically‐validated cessation, and performed sensitivity analyses to determine whether the estimates differed significantly in studies without verification.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialized Register for studies with counsel* in title, abstract or keyword fields. At the time of the search the Register included the results of searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (CENTRAL), issue 4, 2016; MEDLINE (via OVID) to update 20160513; EMBASE (via OVID) to week 201621; PsycINFO (via OVID) to update 20160516. See the Tobacco Addiction Group Module in the Cochrane Library for full search strategies and list of other resources searched. We also checked previous reviews and meta‐analyses for relevant studies, including all studies in the previous US guidelines (AHCPR 1996; Fiore 2000; Fiore 2008). The most recent search was conducted in May 2016.

Data collection and analysis

One author (LS, who is also the Cochrane Information Specialist for the Tobacco Addiction Group) prescreened results of the searches. Both authors checked reports of studies of potentially relevant interventions.

Both authors extracted data independently.

Information extracted included descriptive details on the setting of the study, the population, and details of intervention(s) and control conditions, including number and duration of planned sessions.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of selection, detection and attrition bias, based on the reported methods of randomization and allocation concealment (selection bias), use of biochemical validation of self‐reported abstinence (detection bias) and numbers lost to follow‐up (attrition bias).

Measures of treatment effect & data synthesis

We summarized individual study results as a risk ratio (RR), calculated as: (number of quitters in intervention group/number randomized to intervention group) / (number of quitters in control group/number randomized to control group). We assumed that participants lost to follow‐up continued to smoke and included them as such in denominators. Where appropriate we performed meta‐analysis using a Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect method to estimate a pooled risk ratio with a 95% confidence interval (CI) (Greenland 1985). We estimated the amount of statistical heterogeneity between trials using the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). Values over 50% can be regarded as moderate heterogeneity, and values over 75% as high.

We made the following comparisons:

Individual counselling versus no treatment, brief advice or self‐help materials

More intensive versus less intensive individual counselling

Comparisons between counselling methods matched for contact time

Results

Description of studies

We include 49 studies in this updated review, with around 19,000 participants. Thirty‐three studies (11 new for this update) contribute to the primary analysis comparing individual counselling to a minimal contact behavioural intervention. Eleven studies (six new) compared different intensities of counselling and five (two new) compared different counselling approaches which were similar in intensity of contact.

In a few cases we resolved difficulties in applying the inclusion criteria by discussion. In two cases (Wiggers 2006; Aveyard 2007) we were uncertain whether the providers were acting as specialist counsellors or were providing interventions as part of usual care in other healthcare roles. We included both after discussion about this aspect of their designs. We included one study that had only five months follow‐up (Kim 2005).

Study populations

Nineteen of the 49 studies recruited medical or surgical hospital inpatients (Pederson 1991; Ockene 1992; Stevens 1993; Rigotti 1997; Simon 1997; Dornelas 2000; Molyneux 2003; Simon 2003; Hennrikus 2005; Pedersen 2005; Brunner 2012), or outpatients (Weissfeld 1991; Kim 2005; Tonnesen 2006; Hennrikus 2010; Chan 2012; Ramon 2013; Thankappan 2013; Chen 2014). One recruited some inpatients (Schmitz 1999). Four other studies recruited drug‐ and alcohol‐dependent veterans attending residential rehabilitation (Bobo 1998; Burling 1991; Burling 2001; Mueller 2012). One study recruited new mothers in maternity wards (Hannover 2009); we considered the subgroup of trial participants who were smoking at this point. Other studies recruited smokers in primary care clinics (Fiore 2004; Aveyard 2007; Marley 2014; Ramos 2010), dental clinics (Nohlert 2009), primary care and local community (Aleixandre 1998), local community and university (Alterman 2001), communities and worksites (Nakamura 2004), at a periodic healthcare examination (Bronson 1989), at a Planned Parenthood clinic (Glasgow 2000), employees volunteering for a company smoking cessation programme (Windsor 1988), participants in a lung cancer screening study (Marshall 2016), and community volunteers (Jorenby 1995; Lifrak 1997; Ahluwalia 2006; Killen 2008; McCarthy 2008, Wu 2009; Garvey 2012; Kim 2015). Lack of interest in quitting was not an explicit exclusion criterion in any study, but the level of motivation to quit smoking was sometimes difficult to assess. One trial enrolled all smokers admitted to hospital (Stevens 1993), whilst one enrolled 90% of smokers approached (Rigotti 1997). In one large study in primary care 68% of smokers agreed to participate and 52% met the inclusion criteria and were recruited (Fiore 2004). In other studies a larger proportion of eligible smokers may have declined randomization because of lack of interest in quitting.

Special populations included Australian Aboriginal people (Marley 2014), homeless people (Okuyemi 2013), people under community corrections supervision (Cropsey 2015) and people with schizophrenia (Williams 2010). Two studies recruited Asian minority populations in the US; Kim 2015 (Koreans) and Wu 2009 (Chinese), and one recruited African Americans (Ahluwalia 2006).

Two studies recruited only women: Schmitz 1999 recruited 53 women hospitalized with coronary artery disease (CAD) and 107 volunteers with CAD risk factors. Glasgow 2000 recruited women attending Planned Parenthood clinics, who were not selected for motivation to quit. Weissfeld 1991 recruited only men, while Simon 2003 and Nakamura 2004 recruited predominantly men.

Thirty studies were conducted in the USA, three in Spain (Aleixandre 1998; Ramos 2010; Ramon 2013), three in Denmark (Pedersen 2005; Tonnesen 2006; Brunner 2012), two in the UK (Molyneux 2003; Aveyard 2007), two in Australia (Marley 2014; Marshall 2016), and one each in Germany (Hannover 2009), Switzerland (Mueller 2012), Sweden (Nohlert 2009), Netherlands (Wiggers 2006), Hong Kong (Chan 2012), China (Chen 2014), Japan (Nakamura 2004), Korea (Kim 2005), and India (Thankappan 2013).

Intervention components

The counselling interventions typically included the following components: review of a participant's smoking history and motivation to quit, help in the identification of high‐risk situations, and the generation of problem‐solving strategies to deal with such situations. Counsellors may also have provided non‐specific support and encouragement. Some studies provided additional components such as written materials, video or audiotapes. The main components used in each study are shown in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

Intervention providers

The therapists who provided the counselling were generally described as smoking cessation counsellors. Their professional backgrounds included social work, psychology, psychiatry, health education and nursing. In one study, the therapist for some of the sessions was a nurse practitioner (Alterman 2001), and in two others the therapists were research doctors or nurses trained in counselling (Molyneux 2003; Hennrikus 2005). In Aveyard 2007 all the support was from primary care nurses who were not full‐time counsellors. We included this study because the nurses were trained to provide counselling support as part of the National Health Service Stop Smoking Services and were not offering it as part of usual care. In Tonnesen 2006 the counselling was provided by nurses employed in a lung clinic, and in Wiggers 2006 it was provided by nurse practitioners in a cardiology outpatient clinic.

Studies with minimal contact controls

In the 33 studies with a minimal contact control the treatments offered to the control comparison group ranged from usual care to up to 15 minutes of advice, with or without the provision of self‐help materials. To be classified as individual counselling the trials had to involve at least one session with face‐to‐face contact lasting more than 10 minutes, although the duration was typically much longer. The face‐to‐face counselling in Kim 2005 was the shortest, at only 11 minutes on average. Three tested a single face‐to‐face session without further support by telephone (Weissfeld 1991 (low‐intensity arm); Molyneux 2003; Marshall 2016). Nine others offered a single face‐to‐face session with further support by telephone (Windsor 1988; Weissfeld 1991 (high‐intensity arm); Stevens 1993; Rigotti 1997; Simon 1997; Dornelas 2000; Glasgow 2000; Hennrikus 2005; Kim 2005). All the other studies planned multiple sessions of face‐to‐face support, and sometimes also telephone contacts.

In the meta‐analysis we have not distinguished between brief advice, usual care or provision of self‐help materials as the control intervention with which counselling is compared. Provision of written materials was generally accompanied by brief advice; no trials directly addressed the effect of providing counselling as an addition to a structured self‐help programme. One trial offered 15 minutes of counselling on a healthy diet to controls (Chan 2012), and one offered autogenic training, a relaxation‐based programme not shown to aid cessation (Mueller 2012).

Within this group of studies, pharmacotherapy was systematically provided to participants in all trial arms in six trials. Nicotine patch was provided to all participants in Jorenby 1995; Simon 2003; Fiore 2004; Okuyemi 2013. Cropsey 2015 provided bupropion to all participants. Wiggers 2006 provided nicotine patches to participants ready to quit in either trial arm. Since the use of pharmacotherapy might change the relative effect of additional counselling, we include these studies in a subgroup analysis. In one trial (Simon 1997) smokers randomized to receive counselling were given a prescription for nicotine gum if there were no contraindications. Although 65% in the counselling condition used gum compared to 17% of the control group, its use was not significantly associated with quitting.

Studies of counselling intensity

Eleven studies compared intensive counselling to less intensive interventions that also met our definition of counselling by involving more than 10 minutes of face‐to‐face contact. We considered these studies separately from those using a minimal‐contact control. Eight of these studies provided pharmacotherapy to all participants and we included subgroups for studies with and without pharmacotherapy. Tonnesen 2006 contributed to both subgroups.

Weissfeld 1991 compared two intensities of counselling with a control; both intensities are combined versus control in the first analysis but compared in this analysis.

Lifrak 1997 compared two intensities of counselling as an adjunct to nicotine patch therapy. The lower‐intensity one was a four‐session advice and education intervention from a nurse practitioner who reviewed self‐help materials and monitored patch use. The higher‐intensity intervention added 16 weekly sessions of cognitive behavioural relapse prevention therapy.

Alterman 2001 used similar interventions to Lifrak 1997, but added a lower‐intensity control of a single 30‐minute session with a nurse practitioner.

Tonnesen 2006 compared seven visits and five phone calls with a contact time of 4½ hours to four visits and six calls taking 2½ hours. This trial had a factorial design, also comparing a nicotine sublingual tablet and placebo; we entered the arms with and without NRT in separate subgroups.

Aveyard 2007 compared seven weekly contacts with four contacts for people receiving cessation support with nicotine patches.

Killen 2008 provided six counselling session and combined NRT and bupropion, and compared different schedules of extended contact.

Nohlert 2009 compared eight 40‐minute sessions over four months with a single 30‐minute session introducing a self‐help programme.

Wu 2009 compared four 60‐minute culturally‐tailored counselling sessions to four 60‐minute health education sessions covering general health, nutrition, exercise and tobacco. All sessions were in Chinese, and all participants were offered nicotine patch.

Williams 2010 compared 24 weekly 45‐minute counselling sessions to nine 20‐minute sessions that focused on medication management. All participants were given nicotine patches.

Brunner 2012 provided a 30‐minute counselling session and offer of nicotine patch during a hospital stay and tested the effect of an additional five outpatient sessions including free samples of NRT; we included this in the non‐pharmacotherapy subgroup, as it was not provided as standard to all participants.

Kim 2015 compared eight weekly 40‐minute sessions of culturally‐tailored counselling to eight 10‐minute sessions focusing on medication management. All participants received nicotine patches.

Studies of counselling methods or timing

Five studies compared different counselling approaches that had similar contact times. We considered these separately from the groups above.

Schmitz 1999 involved six one‐hour sessions. One intervention used a coping skills relapse prevention model. It was compared with a health belief model that focused on smoking‐related health information, the relationship with coronary disease and the benefits of quitting.

Ahluwalia 2006 provided three face‐to‐face visits and three phone contacts extending over six weeks, and 2 mg nicotine gum for eight weeks. One intervention used motivational interviewing and the other a health education focus.

McCarthy 2008 provided eight 10‐minute counselling sessions during assessment visits in a trial that also compared bupropion to placebo. The counselling was consistent with US practice guidelines. The control focused on medication use and adherence, and general support and encouragement.

Garvey 2012 compared two different schedules of 14 counselling sessions, either front‐loaded with six sessions in the first two weeks after quit date, or just two in that period. All participants received nicotine patches.

Ramon 2013 directly compared delivery of counselling either entirely face‐to‐face or with a combination of face‐to‐face and telephone to a control group where all contact after the pre‐quit session was by telephone.

Excluded studies

We excluded one study that provided motivational interviewing as part of an intervention to reduce passive smoke exposure in households with young children (Emmons 2001). Cessation was a secondary outcome and there was no significant difference in quit rates, which were not reported separately by group. A sensitivity analysis including this study assuming equal quit rates did not alter the review results.

We list 48 other studies identified as potentially relevant but which did not meet the full inclusion criteria, with their reasons for exclusion in the table Characteristics of excluded studies. We note where studies were included in other Cochrane Reviews.

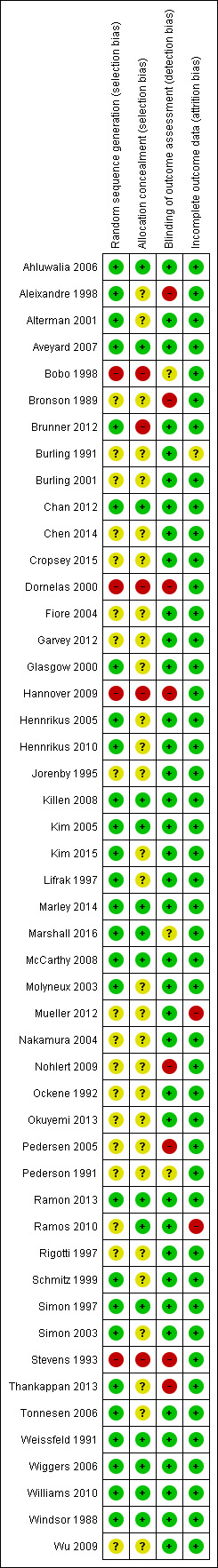

Risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risks of selection bias, detection bias and attrition bias.

Twenty‐seven studies reported the method for generating the randomization sequence in sufficient detail to be classified as having a low risk of bias, but only 14 also described a method of allocation likely to ensure that the assignment was concealed until after allocation, and thus being at low risk of selection bias (Simon 1997; Weissfeld 1991; Windsor 1988; Kim 2005; Ahluwalia 2006; Wiggers 2006; Aveyard 2007; Killen 2008; McCarthy 2008; Williams 2010; Chan 2012; Ramon 2013; Marley 2014; Marshall 2016). In most other trials, neither the method of randomization nor the use of allocation concealment was described. We judged five trials to be at high risk of selection bias, due to the method of randomization or concealment, or both (Stevens 1993; Bobo 1998; Dornelas 2000; Hannover 2009; Brunner 2012).

We judged the risk of detection bias to be low if self‐reported abstinence was confirmed biochemically. Eight studies were at high risk of bias because no validation was attempted and trial arms had different amounts of contact with study staff, making differential misreporting of abstinence more likely (Bronson 1989; Stevens 1993; Aleixandre 1998; Pedersen 2005; Nohlert 2009; Thankappan 2013; Kim 2005; Ahluwalia 2006). We rated three studies as unclear; one study tested for cotinine but did not report validated rates (Bobo 1998), and in two others validation was incomplete and results were based on self‐report (Pederson 1991; Marshall 2016).

We judged the risk of attrition bias to be low if loss to follow‐up was reported by group, was no greater than 50% and not substantially different between groups. Most studies reported the number of participants who dropped out or were lost to follow‐up, and included these people as smokers in analysis denominators. We judged most studies to be at low risk of bias, because the percentage lost was small and similar across conditions. We classified two studies as being at high risk (Ramos 2010; Mueller 2012), and one as unclear (Burling 1991). One study (Fiore 2004) excluded randomized participants who failed to collect their free supply of nicotine patches, and as a consequence also did not receive any additional behavioural components to which they were allocated. The proportions excluded were similar in all the intervention groups, so we have used the denominators as given.

Overall we classified 11 of the 49 included studies (22%) as being at low risk of bias on all the domains we considered. A summary is displayed in Figure 1.

1.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

We did not formally assess the risk of performance bias. There was little information about blinding of participants or staff during treatment. Whilst the therapists delivering counselling could not have been blinded, in some cases other care providers were noted to be unaware of intervention status. It was unclear what information participants were given, but almost all trials included an active control group that received some information about stopping smoking. Because of this, we do not consider that the risk of bias from this aspect of design for this group of studies is high.

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Individual counselling compared to minimal contact control for smoking cessation.

| Patient or population: People who smoke Setting: Healthcare and community settings Intervention: Individual counselling from a smoking cessation counsellor including at least one face‐to‐face session lasting 10 minutes or more Comparison: Minimal‐contact control (usual care, brief advice or self‐help materials) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Numbers quit in control condition | Numbers quit after individual counselling | |||||

| Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up ‐ 6 months or more No systematic pharmacotherapy |

Study population | RR 1.57 (1.40 to 1.77) | 11,100 (27 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Limiting to studies at low risk of bias on all assessed domains marginally increases estimate of effect | |

| 7 per 100 | 11 per 100 (10 to 12) | |||||

| Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up ‐ 6 months or more Pharmacotherapy offered to all participants |

Study population | RR 1.24 (1.01 to 1.51) | 2662 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | Higher control group quit rate reflecting use of pharmacotherapy | |

| 11 per 100 | 13 per 100 (11 to 16) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1Downgraded due to wide confidence intervals.

Summary of findings 2. More intensive compared to less intensive counselling for smoking cessation.

| More intensive compared to less intensive counselling for smoking cessation | ||||||

| Patient or population: People who smoke Setting: Healthcare and community settings Intervention: More intensive individual counselling (± pharmacotherapy) Comparison: Individual counselling (± pharmacotherapy) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Numbers quit with less intensive counselling | Numbers quit with more intensive counselling | |||||

| Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up | Without pharmacotherapy | RR 1.29 (1.09 to 1.53) | 2920 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Effect estimates for subgroups of studies with and without pharmacotherapy for all participants overlapped, so the overall pooled estimate is used with alternative control group estimates from subgroups | |

| 9 per 100 1 | 12 per 100 (10 to 14) | |||||

| With pharmacotherapy | ||||||

| 14 per 100 2 | 18 per 100 (15 to 21) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1Based on average in studies without pharmacotherapy.

2Based on average in studies with pharmacotherapy.

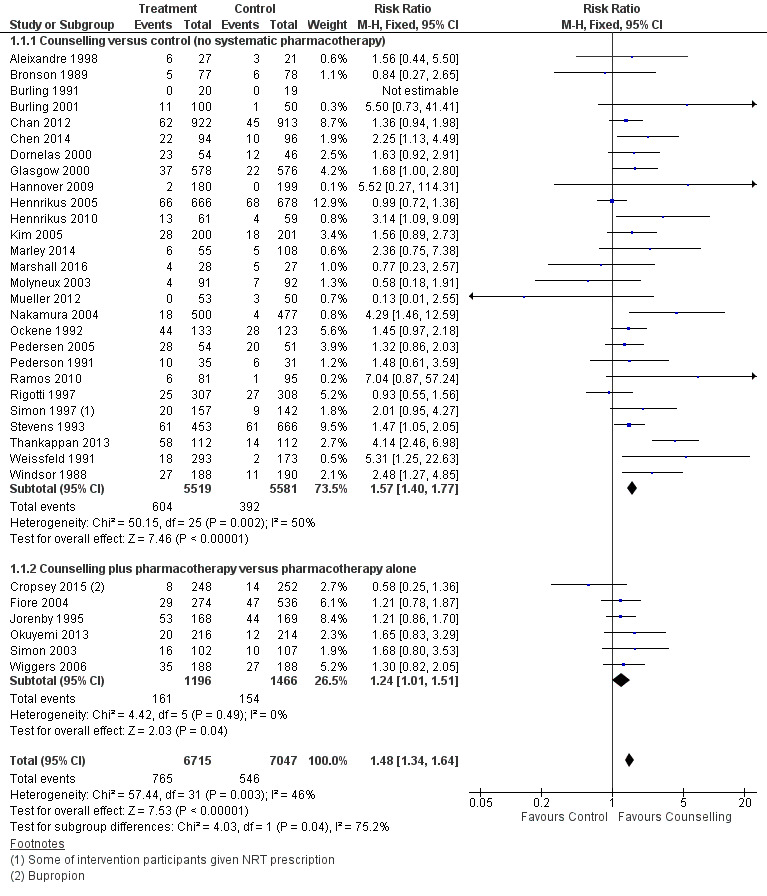

Counselling versus minimal contact control

We estimated a pooled effect size based on 33 studies of counselling, including one (Burling 1991) where there were no quitters and which therefore did not contribute to the meta‐analysis. The risk ratio (RR) was 1.48 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.34 to 1.64, n = 13,762; Analysis 1.1), with some evidence of heterogeneity (I2 = 46%). Restricting the analysis to seven studies at low risk of bias on all domains (Windsor 1988; Weissfeld 1991; Simon 1997; Kim 2005; Wiggers 2006; Chan 2012; Marley 2014) did not alter the conclusions; the point estimate increased slightly (RR 1.65, 95% CI 1.32 to 2.06). The estimate was higher in the subgroup of 27 studies where pharmacotherapy was not provided (RR 1.57, 95% CI 1.40 to 1.77; n = 11,100; I2 = 50%) than in the six testing the additional effect of counselling when participants had access to pharmacotherapy (RR 1.24, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.51; n = 2662; I2 = 0%) and a test for subgroup difference detected a difference between subgroups with and without pharmacotherapy. We base the estimates of absolute effect in Table 1 on the subgroup estimates.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Individual counselling compared to minimal contact control, Outcome 1 Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up.

2.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Individual counselling compared to minimal contact control, outcome: 1.1 Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up.

More intensive versus less intensive counselling

Eight of the studies compared different levels of counselling as adjuncts to pharmacotherapy, and four did not offer medication (Tonnesen 2006 contributes different arms to each subgroup). The estimates in the two subgroups overlapped. Pooling all 11 studies, there was evidence of a small benefit from more intensive compared to brief counselling (RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.53; n = 2920; I2 = 48%; Analysis 2.1), a change from the previous version of the review in which pooling five studies did not detect evidence of benefit. The moderate heterogeneity was attributable to two new studies with large effects. The control groups in these were distinct, with Wu 2009 offering general health education and Kim 2015 focusing on medication management. A sensitivity analysis excluding these two studies no longer detected evidence of a dose response to counselling intensity. Limiting the analysis to four studies at low risk of bias also failed to suggest evidence of benefit.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 More intensive versus less intensive counselling, Outcome 1 Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up.

Comparisons between counselling approaches

We did not pool these clinically heterogeneous five studies. Only one of them detected a significant difference between different types of counselling, where number of contacts and general intensity were similar. Schmitz 1999, comparing a relapse prevention approach to a health belief model, showed no significant difference, but with wide confidence intervals (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.45 to 1.98; n = 160; analysis 3.1.1). Ahluwalia 2006 compared a motivational interviewing to a health education approach and the point estimate favoured the latter (RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.76; n = 755; analysis 3.1.2). Participants were making quit attempts and using nicotine gum or placebo and therefore the motivational aspect may have been less relevant. McCarthy 2008 was also a pharmacotherapy trial with a factorial design and the specific behavioural components did not increase quitting over instructions about medication and general support (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.39; n = 463; analysis 3.1.3). There was no evidence of an interaction between medication and counselling in either of the factorial trials. Garvey 2012 did not show that front‐loading the schedule of sessions was associated with greater quit success, but CIs did not exclude no effect (RR 1.81, 95% CI 0.79 to 4.15; n = 242; analysis 3.1.4). Ramon 2013 did not detect a difference between face‐to‐face and telephone counselling (RR 1.39, 95% CI 0.89 to 2.19; n = 301; analysis 3.1.5), or combined contact (face‐to‐face plus telephone) versus telephone only (RR 1.44, 95% CI 0.92 to 2.25; n = 299), but confidence intervals were again wide.

Discussion

There is consistent evidence that individual counselling increases the likelihood of cessation compared to less intensive support. Individual counselling, used independently of pharmacotherapy, was estimated to increase cessation by 40% to 80% after at least six months, based on pooling 27 trials with over 11,000 participants. Assuming a control group quit rate of 7% from a brief intervention, the provision of counselling would be expected to result in 10% to 12% quit, an absolute increase of 3% to 5%. We rated the quality of this evidence as high, using the GRADE approach (Table 1). This estimate was based on using counselling without any pharmacotherapy. The six trials that offered pharmacotherapy (typically nicotine replacement therapy) to all participants had a smaller and less certain effect. Assuming a control quit rate of 11% reflecting the benefit of medication, the addition of counselling could result in an absolute increase of 0% to 5%. We rated this as moderate quality using GRADE, because of the imprecision of the estimate. It is possible that the relative additional benefit is smaller when the quit rates in the control group are already increased by the use of an effective pharmacotherapy, but the absolute benefit of counselling could be similar, whether or not pharmacotherapy is used.

Almost half the trials recruited people in hospital settings, but there was no evidence of heterogeneity of results in different settings.

These results are consistent with the US Public Health Service practice guideline (Fiore 2008), which supports the use of intensive counselling. The guideline evidence in this area is based on meta‐analyses conducted for the previous update of the guideline (Fiore 2000), and includes indirect comparisons. These included an analysis of 58 trials where treatment conditions differed in format (self‐help, individual counselling with person‐to‐person contact, proactive telephone counselling or group counselling) and estimated an odds ratio (OR) for successful cessation with individual counselling compared to no intervention of 1.7 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.4 to 2.0) (Fiore 2008 Table 6.13). Individual counselling in their categorization would have also included counselling from a physician. When they separately analysed the effect of different providers of care the estimates suggest that non‐physician clinicians (a category including psychologists, social workers and counsellors) are similarly effective compared to a no‐provider reference group (OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.3 to 2.1) as physicians (OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.5 to 3.2) (Fiore 2008 Table 6.11).

In our review there was no evidence of significant heterogeneity between relative quit rates in the different trials. Absolute quit rates varied across studies but this is likely to be related to the motivation of the smokers to attempt to quit and the way in which cessation was defined. Cessation rates were generally higher in trials where nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) was also used (Alterman 2001; Jorenby 1995; Lifrak 1997; Simon 2003), although there were exceptions (Ahluwalia 2006; Aveyard 2007). Rates were also higher amongst people with cardiovascular disease (Ockene 1992 ; Dornelas 2000; Pedersen 2005). Quit rates tended to be lower in studies recruiting hospitalized patients unselected for their readiness to quit (Stevens 1993; Rigotti 1997; Molyneux 2003). All these features of a trial are likely to affect absolute quit rates, confounding a possible effect of the exact content of the intervention.

Whilst we took account of the broad nature of the support offered to the control group when pooling studies, variation in the components used as part of, for example, a usual care control, may still give rise to heterogeneity. Treatment effects could be underestimated if those studies using effective interventions tended to provide relatively helpful usual care or brief advice. An ongoing systematic review is conducting a detailed analysis of behavioural intervention and control elements, and is expected to provide more evidence about this (de Bruin 2016).

The following description of the intervention used in the Coronary Artery Smoking Intervention Study (CASIS) (Ockene 1992) is broadly typical of the interventions used: "The telephone and individual counseling sessions were based on a behavioral multicomponent approach in which counselors used a series of open‐ended questions to assess motivation for cessation, areas of concern regarding smoking cessation, anticipated problems and possible solutions. Cognitive and behavioral self‐management strategies, presented in the self help materials, were discussed and reinforced". Although we cannot exclude the possibility that small differences in components, and in the therapists' training or skills, have an effect on the outcome, it is not possible to detect such differences in the meta‐analysis.

Most of the counselling interventions in this review included repeated contact, but differed according to whether face‐to‐face or telephone contact was used after an initial meeting. There are too few trials to draw conclusions from indirect comparisons about the relative efficacy of the various contact strategies. Again, the homogeneity of the results suggests that the way in which contact is maintained may not be important. A separate Cochrane Review of telephone counselling suggests that telephone support aids quitting (Stead 2013b).

The 11 trials that directly compared different intensities of individual support detected only weak evidence of a dose‐response effect which was sensitive to exclusion of outlying trials, and restriction to trials judged to be at low risk of bias. In some of the trials in this comparison the difference between the counselling protocols may be too small to affect long‐term quitting. The intended difference may also be eroded if the more intensive support cannot be consistently delivered. Eight of the trials provided pharmacotherapy to all participants, so were testing the additional benefit of more intensive individual counselling. As seen in the trials offering pharmacotherapy in the primary analysis, the relative effect of the additional support may be smaller in relation to the higher rates of cessation in the control arm receiving combined behavioural and pharmacological support. A separate Cochrane Review (Stead 2015) has assessed the effect of increasing the amount of any type of behavioural support when used alongside pharmacotherapy. It analysed 47 studies including relevant studies from this review, and concluded that "increasing the amount of behavioural support is likely to increase the chance of success by about 10% to 25%". The estimates in this review are consistent with that range.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Counselling interventions given outside routine clinical care, by smoking cessation counsellors including health educators and psychologists, assist smokers to quit.

Implications for research.

Individual counselling is an established treatment for smoking cessation. Identifying the most effective and cost‐effective intensity and duration of treatment for different populations of smokers is still an area for research. However, differences in relative effect are likely to be small, especially when counselling is used alongside pharmacotherapy. Small trials are unlikely to provide clear evidence of long‐term efficacy.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 12 March 2018 | Amended | Correction to plain language summary to say that individual counselling could increase the chance of quitting by between 40% and 80%, so there is consistency with risk ratio (the bracket was previously, erroneously given as 40%‐60%). |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 1998 Review first published: Issue 2, 1999

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 23 November 2016 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | No change to main conclusions. |

| 23 November 2016 | New search has been performed | Searches updated, 19 new studies included. 'Summary of findings' table added. |

| 16 July 2008 | New search has been performed | Updated for 2008 issue 4 with nine new studies. No changes to conclusions |

| 21 May 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 8 February 2005 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Updated for 2005 Issue 2 with three new studies. No changes to conclusions. |

| 7 April 2002 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Updated for 2002 Issue 3 with six new studies. No changes to conclusions. |

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to Peter Hajek and the late Roger Secker‐Walker for their helpful comments on the first version of this review. Nete Villebro translated a Danish paper

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Individual counselling compared to minimal contact control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up | 33 | 13762 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.48 [1.34, 1.64] |

| 1.1 Counselling versus control (no systematic pharmacotherapy) | 27 | 11100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.57 [1.40, 1.77] |

| 1.2 Counselling plus pharmacotherapy versus pharmacotherapy alone | 6 | 2662 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.24 [1.01, 1.51] |

Comparison 2. More intensive versus less intensive counselling.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up | 11 | 2920 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.29 [1.09, 1.53] |

| 1.1 No pharmacotherapy | 4 | 872 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.42 [0.98, 2.06] |

| 1.2 Adjunct to pharmacotherapy | 8 | 2048 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.26 [1.04, 1.52] |

Comparison 3. Comparisons between counselling approaches of similar intensity.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Relapse prevention versus health belief model | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Motivational interviewing versus health education | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.3 Counselling versus equal sessions of psychoeducation | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.4 Front‐loaded versus weekly counselling | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.5 Face‐to‐face versus telephone counselling | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Comparisons between counselling approaches of similar intensity, Outcome 1 Smoking cessation at longest follow‐up.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Ahluwalia 2006.

| Methods | Study design: Randomized controlled trial Setting: Community health centre, USA Recruitment: community volunteers interested in quitting |

|

| Participants | 755 African‐American light smokers (≤ 10 cpd) 67% women, av. age 45, av. cpd 8 | |

| Interventions | Therapists: trained counsellors Factorial trial, 2 mg nicotine gum/placebo arms collapsed for this review 1. Counselling using motivational interviewing (MI) approach. 3 in‐person visits at randomization, wk 1, wk 8, and phone contact at wk 3, wk 6, wk 16, S‐H materials 2. Counselling using health education (HE) approach. Same schedule and materials as 1 |

|

| Outcomes | PP abstinence at 6m (7‐day PP) Validation: cotinine ≤ 20 ng/ml | |

| Notes | Not in main analysis; compares 2 counselling styles. No significant effect of gum, no evidence of interaction. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Centrally generated blocked scheme, block size 36 |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sealed envelopes opened sequentially |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Biochemical validation of abstinence planned, but low level of cotinine validation. All participants received same level of contact so risk of differential misreporting judged to be low |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 118 (15.6%) lost to follow‐up included in ITT analysis. HE participants less likely to be lost. Alternative assumptions about losses did not alter conclusions |

Aleixandre 1998.

| Methods | Study design: Randomized controlled trial Setting: Primary care clinic, Spain Recruitment: clinic and community volunteers |

|

| Participants | 48 smokers (excludes 6 dropouts) 65% women, av. age 36, av. cpd 24 ‐ 27 | |

| Interventions | Therapist: unclear, primary care clinic staff 1. 'Advanced', 4 x 30‐min over 4 wks, video, cognitive therapy, social influences, relapse prevention 2. 'Minimal' 3‐min advice immediately after randomization |

|

| Outcomes | Abstinence at 12 m Validation: no biochemical validation | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Stratified on cigarette consumption and age, block size 4. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No details given |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No validation of abstinence and different levels of contact |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 6 post‐randomization dropouts excluded from ITT analyses. Their inclusion would marginally increase effect size |

Alterman 2001.

| Methods | Study design: Randomized controlled trial Setting: cessation clinic, USA Recruitment: community volunteers |

|

| Participants | 240 smokers of > 1 pack/day 45% ‐ 54% women, av. age 40, av. cpd 27 | |

| Interventions | Therapists: Nurse practitioners (NP) and trained counsellors All interventions included 8 wks nicotine patch (21 mg with weaning) 1. Low‐intensity. Single session with NP 2. Moderate intensity. as 1 plus additional 3 sessions at wks 3, 6, 9 with NP 3. High‐intensity. As 2. + 12 sessions cognitive behavioural therapy with trained therapist within 15 wks |

|

| Outcomes | Abstinence at 1 yr Validation: urine cotinine < 50 ng/ml, CO ≤ 9ppm | |

| Notes | Only contributes to intensive versus minimal intervention, using 3 vs 2+1. Quit rates significantly lower in 2 than 1 or 3. Using 3 vs 1; 26/80 vs 20/80; RR 1.30 [0.79, 2.13]. Using 3 vs 2; 26/80 vs 9/80; RR 2.89 [1.45, 5.77]. Overall estimate in 2016 no longer sensitive to choice of arms | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | 'Urn technique' |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No details given. Allocation took place after baseline session common to all conditions |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Biochemical validation of abstinence |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 30 (12.5%) lost to follow‐up included in ITT analysis |

Aveyard 2007.

| Methods | Study design: Randomized controlled trial Setting: 26 general practices (primary care clinics), UK Recruitment: 92% volunteers in response to mailings |

|

| Participants | 925 smokers 51% women, av. age 43, 50% smoked 11 ‐ 20 cpd | |

| Interventions | Therapists: Practice nurses trained to provide cessation support and manage NRT Both interventions included 8 wks of 16 mg nicotine patch 1. Basic support; 1 visit (20 ‐ 40 mins) before quit attempt, phone call on TQD, visits/phone calls at 7 ‐ 14 days and at 21 ‐ 28 days (10 ‐ 20 mins) 2. Weekly support; as 1. plus additional call at 10 days and visits at 14 and 21 days |

|

| Outcomes | Abstinence at 12 m (sustained at 1, 4, 12, 26 wks) Validation: CO < 10 ppm at treatment visits, saliva cotinine < 15 ng/ml at follow‐ups | |

| Notes | Not in main analysis; compares higher and lower intensity counselling. Therapists were not full‐time specialist counsellors | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Random‐number generator |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Numbered sealed envelopes |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Biochemical validation of abstinence; staff making follow‐up calls were blind |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 288 (31%) lost to follow‐up, similar across groups, included in ITT analysis |

Bobo 1998.

| Methods | Study design: Cluster‐randomized controlled trial Setting: 12 residential centres for alcohol/drug treatment, USA Recruitment: inpatient volunteers |

|

| Participants | (50 participants in each of 12 sites) 67% men, av. age 33 50% smoked > 1 pack/day | |

| Interventions | Therapists: centre staff for 1st session, trained counsellors for telephone sessions 1. 4 x 10 ‐ 15 min sessions. 1st during inpatient stay. 3 by telephone, 8, 12, 16 wks post‐discharge 2. No intervention | |

| Outcomes | Abstinence at 12 m post‐discharge (7 day PP) Validation: saliva cotinine, but validated quit rates not reported (A primary outcome for the study was alcohol abstinence) | |

| Notes | Cluster‐randomized, so individual data not used in primary meta‐analysis. Adjusted OR 1.02 (CI 0.50 to 2.49). Inclusion would not materially change results of analysis 1.1. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Matched pairs of centres allocated by coin toss, 2 centres declined participation after allocation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Cluster‐randomized with participant recruitment (by research team) after centre allocation so potential for selection bias |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Biochemical validation of abstinence but validated results not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 22% lost to follow‐up. Including them as smokers made little difference to estimates |

Bronson 1989.

| Methods | Study design: Randomized controlled trial Setting: internal medicine practice, USA Recruitment: attenders for periodic health examinations |

|

| Participants | 155 smokers 38% men, av. age 42, av. cpd 25 | |

| Interventions | Therapist: smoking cessation counsellor 1. 2 x 20‐min counselling sessions during a periodic health examination (benefits of quitting, assessment of motivation, quit plan, high risk/problem solving) 2. Control: completed smoking behaviour questionnaire |

|

| Outcomes | Abstinence at 18 m (sustained from 6 ‐ 18 m) Validation: no biochemical validation at 18 m, limited sample for saliva cotinine at 6 m | |

| Notes | 18 m data reported in Secker‐Walker 1990 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomized, method not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No details given |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Physicians carrying out health examinations were blind to group assignment and would have given similar advice to all participants Long‐term abstinence not validated |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 20 (13%) not contacted at 6 m and 18 m, included in ITT analysis |

Brunner 2012.

| Methods | Study design: Randomized controlled trial Setting: Single hospital, Denmark Recruitment: Inpatients with acute ischaemic stroke or TIA invited to participate |

|

| Participants | 94 inpatients | |

| Interventions | Therapists: Single study nurse provided initial session for all participants, and 5 telephone and 1 outpatient session. Main counselling by"'authorized smoking cessation instructor" 1. Minimal intervention: 1 x 30‐min session, offer of nicotine patch during hospital stay 2. Intensive intervention; additional 5 outpatient sessions from counsellor, duration NS. Study nurse also offered 30‐min session at 6 wks and 5 telephone sessions at 2 days, 1 wk, 3 wks, 3 m, 4 m. Free samples of NRT |

|

| Outcomes | Abstinence 6m after discharge Validation: CO < 8 ppm |

|

| Notes | New for 2016 update Contributes to comparison of more versus less intensive Analysis 2.1 (no pharma subgroup) only. 8 minimal and 29 intensive intervention participants used NRT at some time |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Patients were randomized using a computer‐generated list of odd and even numbers. These numbers, representing minimal and intensive smoking cessation intervention, respectively, were used to create consecutive numbered sealed envelopes." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | "After having obtained informed consent, the study nurse opened the randomization envelope and the patients were informed to which intervention they had been assigned." No mention that envelopes were opaque. Intensive intervention participants more likely to be younger, male, heavier smokers, suggesting possibility of selection bias |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Biochemical validation of abstinence |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Loss to follow‐up small and similar between conditions |

Burling 1991.

| Methods | Study design: Randomized controlled trial Setting: Inpatient substance abuse treatment centre, USA Recruitment: inpatient volunteers |

|

| Participants | 39 male veteran inpatients | |

| Interventions | Therapist: paraprofessional counsellor (Social Work Master's candidate) 1. Smoking cessation programme; daily 15‐min counselling session and computer‐guided nicotine fading with contingency contract 2. Wait‐list control |

|

| Outcomes | Abstinence 6 m after discharge Validation ‐ none; no self‐reported quitters at 6 m | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomized, method not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No details given |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No validation, but no self‐reported quitters |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Loss to follow‐up not reported |

Burling 2001.

| Methods | Study design: Randomized controlled trial Setting: Inpatient veterans rehabilitation centre, USA Recruitment: inpatient volunteers |

|

| Participants | 150 veteran drug‐ and alcohol‐dependent smokers 95% men, av. age 40, av. cpd 17 | |

| Interventions | Therapists: Masters/Doctoral level counsellors All participants were receiving standard substance abuse treatment, smoking banned in building. 1. Multicomponent. 9‐wk programme; 7 wks daily counselling, 2 wks bi‐weekly. TQD wk 5. Nicotine fading, contingency contracting, relapse prevention, coping skills practice. Nicotine patch (14 mg) 4 wks 2. As 1, but skills generalized to drug and alcohol relapse prevention 3. Usual care. Other programmes and NRT available |

|

| Outcomes | Abstinence at 12m (sustained at 1, 3, 6 m follow‐ups) Continuous abstinence rates taken from graph and abstract. PP rates also reported Validation: CO and cotinine | |

| Notes | 1+2 vs 3 Using PP rates would give lower estimate of treatment effect. No significant difference between 1 & 2, but favoured 1. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomized, method not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No details given |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Biochemical validation of abstinence |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 12 (8%) lost to follow‐up included in ITT analysis |

Chan 2012.

| Methods | Study design: Randomized controlled trial Country: Hong Kong Recruitment: Cardiac outpatient clinics at 10 major hospitals |

|

| Participants | 1860 Chinese cardiac patients smoking ≥ 1 cig in past week. 91% men, av. age 58, av. cpd 12. Excluded from study if "too clinically ill." | |

| Interventions | Therapist: nurse counsellors 1. Intervention: At baseline, 30‐min individual face‐to‐face counselling matched to stage of readiness to quit. At 1 wk and 1 m: telephone calls from nurse counsellor, re‐assessment of stage and counselling to suit that stage, av. phone call length 15 mins 2. Control: 15‐min, individual face‐to‐face counselling on healthy diet from nurse counsellor at baseline Pharmacotherapy: No smoking cessation drugs provided, but stage‐matched medication counselling on NRT was discussed with intervention participants "if deemed appropriate". |

|

| Outcomes | 7‐day PP at 12 m (30‐day PP at 12 m and 3 m and 6 m outcomes also reported) Validation: CO ≤ 8 ppm, urinary cotinine < 100 ng/ml |

|

| Notes | New for 2016 update Validated rates used in MA; only about 25% of people self‐reporting abstinence were validated. Participants in intervention group had higher stage of readiness to quit smoking than in the control group. Adjusted OR provided in text (unadjusted OR 1.35, 95% CI 0.91 to 2.00; adjusted OR 1.26, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.87); numbers used in MA are unadjusted. 54% intervention received all counselling. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "The allocation sequence was generated sequentially by the project co‐ordinator based on simple random sampling procedure using MS Excel." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "serially numbered sealed and opaque envelope" |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Biochemical validation of abstinence |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Similar rates of follow‐up in both groups at 12 m (85.5% intervention and 84.3% control) "No statistically significant difference was found between the two groups." ITT analysis conducted, 25 who died during study removed from denominators |

Chen 2014.

| Methods | Study design: Randomied controlled trial Setting: Hospital, China Recruitment: community volunteers and referrals from outpatient clinics |

|

| Participants | 190 smokers, > 1 cpd, 97% men, av.age 50, av. cpd 20. All had lung function tests; 85 had COPD and 105 were asymptomatic | |

| Interventions | Therapist: "Interventions provided by 2 doctors with experience of professional smoking cessation treatment." 1. Cognitive counselling, 20 mins at baseline and 9 calls > 10 mins at 1 ‐ 4 wks, 6 wks, 8 wks, 3 ‐ 5 m. S‐H materials 2. Brief advice |

|

| Outcomes | Abstinence at 6 m sustained from week 4 Validation: CO < 10 ppm |

|

| Notes | New for 2016 update | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "assigned to the intervention or control group according to the randomized digital table" stratified by motivation to quit |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No further details |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Biochemical validation of abstinence |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 12 withdrawals included as smokers |

Cropsey 2015.

| Methods | Study design: Randomized controlled trial Setting: Community corrections facility, USA Recruitment: smokers under community corrections supervision |

|

| Participants | 500 smokers; 33% women; av. age 37.4; av. cpd 17.9 | |

| Interventions | Therapist: Clincal psychologist 1. Control. Brief physician advice to set TQD 1 ‐ 2 wks after starting bupropion, stressed adherence 2. Intervention. As 1. plus 4 x 20 ‐ 30‐min counselling sessions; cognitive and behavioural strategies Pharmacotherapy: All participants received bupropion for 12 wks |

|

| Outcomes | Abstinence at 12 m (PP) Validation: CO ≤ 3 ppm at all visits |

|

| Notes | New for 2016 update Paper reports differential abstinence by race. Author confirmed quit rates in Fig 2, used to calculate numbers quit |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomized, blocked on race, no further details |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No details given |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Biochemical validation of abstinence |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 23% I, 26% C lost to follow‐up |

Dornelas 2000.

| Methods | Study design: Randomized controlled trial Setting: Hospital inpatients, USA Recruitment: Acute MI patients (not selected for motivation to quit) |

|

| Participants | 100 MI patients (98% smoked in previous wk) 23% women, aged 27 ‐ 83, av. cpd 29 | |

| Interventions | Therapist: Psychologist 1. 8 x 20‐min sessions, 1st during hospitalization, 7 by phone (< 1, 4, 8, 12, 20 and 26 wks post‐discharge). Stage‐of‐change model, motivational interviewing, relapse prevention 2. Minimal care. Recommended to watch online patient education video, referral to local resources |

|

| Outcomes | Sustained abstinence at 1 yr (no smoking since discharge) Validation: household member confirmation for 70%. 1 discrepancy found | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | "drawing random numbers from an envelope" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | as above |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No biochemical validation |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 20 (20%) lost to follow‐up included in ITT analysis |

Fiore 2004.

| Methods | Study design: Randomized controlled trial Setting: Primary care patients, 16 clinics, USA Recruitment: Clinic attenders willing to accept treatment |

|

| Participants | 961 smokers of 10+ cpd. (A further 908 were allowed to select treatment. Demographic details based on 1869) 58% women, av. age 40, av. cpd 22 | |

| Interventions | Therapists: Trained cessation counsellors (Self‐selected group of factorial trial not included in meta‐analysis) 1. Nicotine patch, 22 mg, 8 wks incl tapering 2. As 1 plus Committed Quitters programme, single telephone session and tailored S‐H 3. As 2 plus individual counselling, 4 x 15 ‐ 25‐min sessions, pre‐quit, ˜TQD, next 2 wks |

|

| Outcomes | Continuous abstinence at 1 yr (no relapse lasting 7 days), also PP Validation: CO, cut‐off not specified. 2 discordant | |

| Notes | 3 versus 1 and 2 used in meta‐analysis. More conservative than 3 versus 2. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomized, method not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No details given |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Biochemical validation of abstinence |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Denominators in meta‐analysis based on numbers who collected patches (85%, similar across arms) |

Garvey 2012.

| Methods | Study design: Randomized controlled trial Setting: Smoking cessation research clinic, Boston USA Recruitment: Community volunteers, motivated to quit |

|

| Participants | 278 smokers of ≥ 5 cpd. 53% women, av. age 47, av. cpd 18 | |

| Interventions | Therapist: MA or BA in psychology, 3 full days training Both group received nicotine patches for 12 weeks, dose tailored to baseline smoking 1. Front‐loaded CBT‐based counselling; 2 pre‐quit and 12 post‐quit, 6 post‐quit sessions received in first 2 weeks. Pre‐quit sessions approx. 45 mins each, post‐quit 20 ‐ 30 mins. Last 3 sessions at 6 m, 9 m, 12 m 2. Weekly counselling. Same number and duration of sessions, but weekly to 12 wks |

|

| Outcomes | Continuous abstinence from quit date at 12 m, (never smoking for 7+ consecutive days nor for 7+ consecutive episodes and PP also reported) Validation: CO < 8 ppm |

|

| Notes | New for 2016 update Analysis 3, not pooled with other studies. Authors report significantly lower likelihood of relapse, using hazard ratio and continuous abstinence to define relapse. Risk ratio based on 11.7% versus 6.3% abstinent at 12 m is not significant |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Block randomization, method of sequence generation not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "randomization occurred at the end of the baseline visit following the consenting process and administration of baseline measures" but no additional information |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Biochemical validation of abstinence |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 20 (14%) front‐loaded and 16 (11.5%) weekly did not start or dropped out before quit date. Not included in denominators for MA. Later losses treated as smokers |

Glasgow 2000.

| Methods | Study design: Randomized controlled trial Setting: 4 Planned Parenthood clinics, USA Recruitment: Clinic attenders, unselected for motivation |

|

| Participants | 1154 female smokers Av. age 24, av. cpd 12 | |

| Interventions | Therapists: 4 hours training Both groups received 20‐sec provider advice. 1. Video (9 mins) targeted at young women. 12 ‐ 15 min counselling session, personalized strategies, stage‐targeted S‐H materials. Offered telephone support call 2. Generic S‐H materials |

|

| Outcomes | Abstinence at 6 m (for 30 days) Validation: saliva cotinine ≤ 10 ng/ml | |

| Notes | 26% did not want telephone component, 31% of remainder not reached | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomized, block size 4, fixed schedule |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No details given |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Biochemical validation of abstinence |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 10% loss to follow‐up included in ITT analysis |

Hannover 2009.

| Methods | Study design: Randomized controlled trial Setting: Maternity wards in 6 hospitals, Germany Recruitment: Women in hospital post partum |

|

| Participants | 379 women who were smoking postpartum (subgroup of trial participants). av. age for all participants 26, av. cpd 14 | |

| Interventions | Therapist: 4 counsellors trained in motivational interviewing 1. Counselling; face‐to‐face session in mothers' homes, duration NS, 2 phone boosters at 4 and 12 wks 2. Usual care and S‐H materials at screening |

|

| Outcomes | Sustained abstinence at 24 m (PP also reported, followed up at 6, 12, 18 m) Validation: none |

|

| Notes | New for 2016 update Using earlier or PP outcome would not affect meta‐analysis |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | "simple randomization .... allocating women to either intervention or control group alternating in the order on the screening forms". Whether the allocation sequence would begin with treatment or control condition was decided ad hoc. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | No possibility of concealment |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No biochemical validation of abstinence |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 16% intervention and 6% control lost or withdrew |

Hennrikus 2005.

| Methods | Study design: Randomized controlled trial Setting: 4 hospitals, USA Recruitment: Newly‐admitted inpatients invited to participate, not selected by motivation |

|

| Participants | 2095 current smokers 53% women, av. age 47, cpd NS, 15 ‐ 20% precontemplators | |

| Interventions | Therapists: research nurses with 12 hours training 1. Control: modified usual care: smoking cessation booklet in hospital (not used in meta‐analysis) 2. Brief advice (A): as control, plus labels in records to prompt advice from nurses and physicians 3. Brief advice and counselling (A+C): As 2, plus 1 bedside (or phone) session using motivational interviewing and relapse prevention approaches and 3 to 6 calls (2 ‐ 3 days, 1 wk, 2 ‐ 3 wks, 1 m, 6 m) |

|

| Outcomes | Abstinence at 12 m (7‐day PP) Validation: saliva cotinine < 15 ng/ml | |

| Notes | Brief advice + counselling compared to brief advice. Including Usual Care in control as well would marginally increase relative effect but not change conclusion of no effect. Authors reported relatively high and differential levels of refusal to provide samples, and samples that failed to confirm abstinence | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "randomly ordered within blocks of 30 assignments" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Allocation by research assistant, concealment not described |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Biochemical validation of abstinence |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 78 (3.7%) excluded from ITT analysis due to death or too ill for follow‐up. 426 (20%) lost to follow‐up included in ITT analysis; higher loss from treatment than control |

Hennrikus 2010.

| Methods | Study design: Randomized controlled trial Setting: 2 medical centres; USA Recruitment: probable smokers with lower extremity PAD |

|

| Participants | 687 current smokers with PAD; 15% women, av. age 60, av. cpd 18 | |

| Interventions | Therapists: smoking cessation counsellor 1. Verbal advice to quit from vascular provider 2. Letter from vascular provider + intensive counselling, at least 6 sessions over 5 m, first in person then phone. Information about pharmacotherapies but not provided |

|

| Outcomes | Abstinence at 6 m (PP) Validation: saliva cotinine < 10 ng/ml, or CO < 8 ppm for people using NRT |

|

| Notes | New for 2016 update High use of pharmacotherapies in both groups; 87% in I, 67% in C |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "predetermined block randomization schedule stratified by medical center" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No details given |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Biochemical validation of abstinence |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 25% I, 17% C lost at 6 m. 4 deaths (3I, 1C) excluded from MA denominators |

Jorenby 1995.

| Methods | Study design: Randomized controlled trial Setting: Clinical research centres, USA (2 sites) Recruitment: community volunteers |

|

| Participants | 504 smokers 15+ cpd av. age 44, av. cpd 26 ‐ 29 | |