Abstract

Background

Physical activity, a balanced diet, avoidance of tobacco exposure, and limited alcohol consumption may reduce morbidity and mortality from non‐communicable diseases (NCDs). Mass media interventions are commonly used to encourage healthier behaviours in population groups. It is unclear whether targeted mass media interventions for ethnic minority groups are more or less effective in changing behaviours than those developed for the general population.

Objectives

To determine the effects of mass media interventions targeting adult ethnic minorities with messages about physical activity, dietary patterns, tobacco use or alcohol consumption to reduce the risk of NCDs.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, ERIC, SweMed+, and ISI Web of Science until August 2016. We also searched for grey literature in OpenGrey, Grey Literature Report, Eldis, and two relevant websites until October 2016. The searches were not restricted by language.

Selection criteria

We searched for individual and cluster‐randomised controlled trials, controlled before‐and‐after studies (CBA) and interrupted time series studies (ITS). Relevant interventions promoted healthier behaviours related to physical activity, dietary patterns, tobacco use or alcohol consumption; were disseminated via mass media channels; and targeted ethnic minority groups. The population of interest comprised adults (≥ 18 years) from ethnic minority groups in the focal countries. Primary outcomes included indicators of behavioural change, self‐reported behavioural change and knowledge and attitudes towards change. Secondary outcomes were the use of health promotion services and costs related to the project.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently reviewed the references to identify studies for inclusion. We extracted data and assessed the risk of bias in all included studies. We did not pool the results due to heterogeneity in comparisons made, outcomes, and study designs. We describe the results narratively and present them in 'Summary of findings' tables. We judged the quality of the evidence using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) methodology.

Main results

Six studies met the inclusion criteria, including three RCTs, two cluster‐RCTs and one ITS. All were conducted in the USA and comprised targeted mass media interventions for people of African descent (four studies), Spanish‐language dominant Latino immigrants (one study), and Chinese immigrants (one study). The two latter studies offered the intervention in the participants’ first language (Spanish, Cantonese, or Mandarin). Three interventions targeted towards women only, one pregnant women specifically. We judged all studies as being at unclear risk of bias in at least one domain and three studies as being at high risk of bias in at least one domain.

We categorised the findings into three comparisons. The first comparison examined mass media interventions targeted at ethnic minorities versus an equivalent mass media intervention intended for the general population. The one study in this category (255 participants of African decent) found little or no difference in effect on self‐reported behavioural change for smoking and only small differences in attitudes to change between participants who were given a culturally specific smoking cessation booklet versus a booklet intended for the general population. We are uncertain about the effect estimates, as assessed by the GRADE methodology (very low quality evidence of effect). No study provided data for indicators of behavioural change or adverse effects.

The second comparison assessed targeted mass media interventions versus no intervention. One study (154 participants of African decent) reported effects for our primary outcomes. Participants in the intervention group had access to 12 one‐hour live programmes on cable TV and received print material over three months regarding nutrition and physical activity to improve health and weight control. Change in body mass index (BMI) was comparable between groups 12 months after the baseline (low quality evidence). Scores on a food habits (fat behaviours) and total leisure activity scores changed favourably for the intervention group (very low quality evidence). Two other studies exposed entire populations in geographical areas to radio advertisements targeted towards African American communities. Authors presented effects on two of our secondary outcomes, use of health promotion services and project costs. The campaign message was to call smoking quit lines. The outcome was the number of calls received. After one year, one study reported 18 calls per estimated 10,000 targeted smokers from the intervention communities (estimated target population 310,500 persons), compared to 0.2 calls per estimated 10,000 targeted smokers from the control communities (estimated target population 331,400 persons) (moderate quality evidence). The ITS study also reported an increase in the number of calls from the target population during campaigns (low quality evidence). The proportion of African American callers increased in both studies (low to very low quality evidence). No study provided data on knowledge and attitudes for change and adverse effects. Information on costs were sparse.

The third comparison assessed targeted mass media interventions versus a mass media intervention plus personalised content. Findings are based on three studies (1361 participants). Participants in these comparison groups received personal feedback. Two of the studies recorded weight changes over time. Neither found significant differences between the groups (low quality evidence). Evidence on behavioural changes, and knowledge and attitudes typically found some effects in favour of receiving personalised content or no significant differences between groups (very low quality evidence). No study provided data on adverse effects. Information on costs were sparse.

Authors' conclusions

The available evidence is inadequate for understanding whether mass media interventions targeted toward ethnic minority populations are more effective in changing health behaviours than mass media interventions intended for the population at large. When compared to no intervention, a targeted mass media intervention may increase the number of calls to smoking quit line, but the effect on health behaviours is unclear. These studies could not distinguish the impact of different components, for instance the effect of hearing a message regarding behavioural change, the cultural adaptation to the ethnic minority group, or increase reach to the target group through more appropriate mass media channels. New studies should explore targeted interventions for ethnic minorities with a first language other than the dominant language in their resident country, as well as directly compare targeted versus general population mass media interventions.

Keywords: Adult, Humans, Health Behavior, Mass Media, Alcohol Drinking, Alcohol Drinking/prevention & control, Black or African American, Diet, Exercise, Feeding Behavior, Health Promotion, Health Promotion/methods, Hotlines, Hotlines/statistics & numerical data, Interrupted Time Series Analysis, Minority Groups, Minority Groups/education, Primary Prevention, Primary Prevention/education, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Smoking Cessation, Smoking Prevention

Plain language summary

Targeted mass media interventions to encourage healthier behaviours in adult, ethnic minorities

Background and review question

Health authorities and non‐governmental organisations often use mass media interventions (e.g. leaflets, radio and TV advertisements, posters and social media) to encourage healthier behaviours related to physical activity, dietary patterns, tobacco use or alcohol consumption, among others. In this review, we consider the effects of mass media interventions targeted towards ethnic minorities. A targeted intervention is designed for and considers the characteristics of a specific group, ideally providing ethnic minority groups equal opportunities and resources to access information, life skills, and opportunities to make healthier choices. However, we do not know whether targeted mass media strategies are more effective in reaching and influencing ethnic minorities than mass media strategies developed for the general population.

Study characteristics

We found six studies, all from the USA, four of which targeted African Americans and two which targeted Latino or Chinese immigrants. Of the studies, four were experimental (1693 volunteers) and two reported the results of large, targeted campaigns run in whole communities and cities. The evidence is current to August 2016.

Key results

The available evidence is insufficient to conclude whether targeted mass media interventions for ethnic minority groups are more, less or equally effective in changing health behaviours than general mass media interventions. Only one study compared participants' smoking habits and intentions to quit following the receipt of either a culturally adapted smoking advice booklet or a booklet developed for the general population. They found little or no differences in smoking behaviours between the groups.

When compared to no mass media intervention, a targeted mass media intervention may increase the number of calls to smoking quit lines, but the effect on health behaviours is unclear. This conclusion is based on findings from three studies. One study gave participants access to a series of 12 live shows on cable TV with information on how to maintain a healthy weight through diet and physical activity. Compared to women who did not watch the shows, participants reported slightly increased physical activity and some positive changes to their dietary patterns; however, their body weight was no different over time. Two other studies were large‐scale targeted campaigns in which smokers were encouraged to call a quit line for smoking cessation advice. The number of telephone calls from the target population increased considerably during the campaign.

This review also compared targeted mass media interventions versus mass media interventions with added personal interactions. These findings, based on three studies, were inconclusive.

None of the studies reported whether the interventions could have had any adverse effects, such as possible stigmatisation or increased resistance to messages.

Further studies directly comparing targeted mass media interventions with general mass media interventions would be useful. Few studies have investigated the effects of targeted mass media interventions for ethnic minority groups who primarily speak a non‐dominant language.

Quality of the evidence

Our confidence in the evidence of effect on all main outcomes is low to very low. This means that the true effect may be different or substantially different from the results presented in this review. We have moderate confidence in the estimated increase in the number of calls to smoking quit lines.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Targeted mass media intervention versus general population mass media intervention for promoting healthy behaviours.

| Comparison 1: targeted mass media intervention versus general population mass media intervention for promoting healthy behaviours | ||||||

| Patient or population: adult, ethnic minority: self‐described Americans of African heritage Setting: volunteers, smokers, USA Intervention: targeted mass media intervention Comparison: general population mass media intervention | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | N of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE)a | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| General population mass media intervention | Targeted mass media intervention | |||||

| Indicators of behavioural change | ||||||

| Any outcome considered an indicator of change | No study provided data for this outcome. | |||||

| Self‐reported behavioural change | ||||||

| Proportion smoking reduction, 3 months follow‐up |

94% | 95% | — | 255 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,c | No effect measures reported by authors. Not significantly different between groups |

| Quit‐attempts, 3 months follow‐up |

— | — | Adjusted OR 1.97 (1.09 to 3.55) in favour of general population mass media intervention | 255 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,c | 24‐hour and 7‐day point prevalence abstinence not significantly different between groups |

| Knowledge and attitudes to change | ||||||

| Contemplation ladder to quit smoking (1‐10), 3 months follow‐up | Mean score: 8.2 (SD 2.4) | Mean score: 7.3 (SD 2.6) | — | 255 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,c | Difference between group reported at P = 0.01 |

| Adverse effects | ||||||

| Any outcome considered an adverse effect | No study provided data for this outcome. | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; SD: standard deviation. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aIn the GRADE assessments for the domain 'directness', we considered the studies directly relevant to the inclusion criteria. Thus, we have not downgraded on this domain. However, the population of interest will be dissimilar in different contexts, relating to characteristics of the ethnic minority group, the country and setting overall. The transferability of results must be considered for each context specifically. bDowngraded one level for unclear risk of bias. cDowngraded two levels for imprecision: Only one, relatively small study.

Summary of findings 2. Targeted mass media intervention for promoting healthy behaviours versus no intervention.

| Comparison 2: targeted mass media intervention for promoting healthy behaviours versus no intervention | ||||||

| Patient or population: adult, ethnic minority group: self‐described Americans of African heritage Setting: volunteers, community setting, USA Intervention: targeted mass media intervention Comparison: no intervention | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | N of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE)a | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| No intervention | Targeted mass media intervention | |||||

| Indicators of behavioural change | ||||||

| BMI (kg/m2), 12 months from baseline | 34.4 (SD 8.5)b | Mean difference in change 0.1 (−0.4 to 0.6) | — | 154 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc | Corresponding risk at 3 months: mean difference in change −0.4 (−0.7 to −0.02) |

| Self‐reported behavioural change | ||||||

| Changes in dietary composition, 12 months from baseline | Food habits questionnaire, score on fat behaviours (no scoring scale provided by study authors): 1.0 (SD 0.4) | Mean difference in change −0.2 (−0.3 to ‐0.1) | — | 154 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc,d | Corresponding risk at 3 months: mean difference in change −0.1 (−0.2 to −0.02) |

| Leisure time physical activity, 12 months from baseline | Physical activity score (no scoring scale provided by study authors): 60.0 (SD 47.0)e | Mean difference in change 12.0 (1.0 to 23.0) | — | 154 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc,d | Corresponding risk at 3 months: mean difference in change 10.0 (−1.7 to 21.8) |

| Knowledge and attitudes to change | ||||||

| Any measure of knowledge and attitude | No study provided data for this outcome. | |||||

| Adverse effects | ||||||

| Any outcome considered an adverse effect | No study provided data for this outcome. | |||||

| Use of health promotion services (secondary outcome) | ||||||

| Calls to smoking quit lines, during campaign | 18 calls per estimated 10,000 African American smokers in the intervention group versus 0.2 calls in the control communitiesf. | Estimated target population 641,800 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateg,h | — | ||

| Calls to smoking quit lines, during and after campaign | Change from pre‐campaign, calls per month (95% CI) from new pregnant smokers: 8 (1 to 14) first month of campaign, 8 (1 to 14) last month of campaign, 6 (−1 to 12) first month after campaign, 3 (−4 to 10) 4 months after campaign | Population in target city ˜300,000 (1 ITS) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowi,j | — | ||

| Proportion of calls from target population during campaign | Proportion of calls from African Americans during trial: 82% in intervention and 26% in control communities | Estimated target population 641,800 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowg,k | — | ||

| Proportion of calls from target population during and after campaign | Proportion African Americans among pregnant callers: 41% before campaign, 86% during the campaign, 28% after campaign | Population in target city ˜300,000 (1 ITS) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowi,k | — | ||

| Costs of the project (secondary outcome) | ||||||

| Programme costs | USD 106,821 for radio advertisements and USD 6744 for television advertisements. No overall costs reported | Estimated target population 641,800 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowg,k | — | ||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; ITS: interrupted time series; RTC: randomised controlled trial; SD: standard deviation. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aIn the GRADE assessments for the domain 'directness', we considered the studies directly relevant to the inclusion criteria. Thus, we have not downgraded on this domain. However, the population of interest will be dissimilar in different contexts, relating to characteristics of the ethnic minority group, the country and setting overall. The transferability of results must be considered for each context specifically. bMean BMI at baseline in comparison group. cDowngraded two levels for imprecision: only one relatively small study. dDowngraded one level for unclear risk of bias. eMean score at baseline in comparison group fMeasures of dispersion not reported. No adjustment for cluster‐randomised design. gDowngraded one level for unclear risk of bias in the largest study. hUnclear precision of estimate and no adjustment for cluster‐randomised design, but substantial effect. Results from ITS study concludes similarly. Therefore, we have not downgraded for imprecision. iGrading of ITS study (observational study) starts at low quality evidence. jResults from RCT study concludes similarly. Therefore, we have not downgraded for imprecision. kDowngraded one level for imprecision.

Summary of findings 3. Targeted mass media intervention versus targeted mass media intervention plus personalised content.

| Comparison 3: targeted mass media intervention versus targeted mass media intervention plus personalised content | ||||||

| Patient or population: adult, ethnic minority groups: Latino immigrants, elderly Chinese immigrants, self‐described Americans of African heritage Setting: volunteers, community setting, USA Intervention: targeted mass media intervention Comparison: media intervention combined with personalised content | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | N of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE)a | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Media intervention with personalised content (comparison) | Targeted mass media intervention | |||||

| Indicators of behavioural change | ||||||

| BMI (kg/m2), 12 months from baseline | 34.9 (SD 7.7)b | Mean difference in change 0.4 (−0.1 to 0.8) | — | 286 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc | Two RCTs (643 participants) reported BMI at 3 months. None found significant differences in weight change between study groups |

| Self‐reported behavioural change | ||||||

| Intake meeting target from dietary guidelines, 3 months from baseline | Vegetables: adjusted OR 5.53d (1.96 to 15.58) Fruit: adjusted OR 1.77d (0.99 to 3.15) |

718 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc,e | — | ||

| Changes in dietary composition, 12 months from baseline | Food habits questionnaire, score on fat behaviours (no scoring scale provided by study authors): 1.0 (SD 0.4)f | Mean difference in change −0.1 (−0.2 to −0.02) | — | 286 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc,e | Two RCTs (643 participants) reported changes in dietary composition at 3 months. None found significant differences/mean difference in change for energy or dietary fibre intake (study 1) or food habits questionnaire (fat behaviours) (study 2) |

| Weekly physical activity meeting target from guidelines, 3 months from baseline | Adjusted OR 1.27d (0.89 to 1.80) | 718 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc,e | — | ||

| Leisure time physical activity, 12 months from baseline | Physical activity score (no scoring scale provided by study authors): 68.0 (47.6)f | Mean difference in change 12.9 (3.5 to 22.3) | — | 286 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc,e | Corresponding risk at 3 months: mean difference in change −2.2 (−12.9 to 8.5) |

| Knowledge and attitudes to change | ||||||

| Knowledge of nutrition and physical activity guidelines | Daily vegetable intake: adjusted OR 12.6d (6.50 to 24.5) Daily fruit intake: adjusted OR 16.2d (5.61 to 46.5) Weekly physical activity: adjusted OR 2.70d (0.31 to 23.2) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc,e | — | |||

| Adverse effects | ||||||

| Any outcome considered an adverse effect | No study provided data for this outcome. | |||||

| Costs of the project (secondary outcome) | ||||||

| Costs per person in each treatment arm | USD 9.00 for targeted newsletters, USD 45.00 individually tailored newsletters, and USD 135 for individually tailored newsletters followed by home visits | 357 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc,e | — | ||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial;RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aIn the GRADE assessments for the domain 'directness', we considered the studies directly relevant to the inclusion criteria. Thus, we have not downgraded on this domain. However, the population of interest will be dissimilar in different contexts, relating to characteristics of the ethnic minority group, the country and setting overall. The transferability of results must be considered for each context specifically. bMean (SD) BMI at baseline in comparison group. cDowngraded two levels for imprecision: Relatively small studies and few measurement points. dOR > 1 in favour of targeted mass media combined with personalised content (control intervention). Effect estimates adjusted for cluster‐randomised design. eDowngraded one for unclear risk of bias. fMean (SD) score at baseline in comparison group.

Background

Description of the condition

This Cochrane Review explores the effectiveness of targeted mass media interventions in advising ethnic minority groups on preventing non‐communicable diseases (NCDs) through healthier behaviours. Specifically, this review addresses the question of whether or not ethnic minorities will benefit from targeted approaches, which means that interventions are designed to consider characteristics of particular groups (Kreuter 2003).

The most prevalent NCDs (cardiovascular diseases, cancers, chronic respiratory disease, and diabetes) are also the world's leading causes of morbidity and mortality. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), NCDs cause 63% of global deaths, about 40% of which occur in people between 30 and 70 years of age (WHO 2010). The burden of NCDs is a growing public health crisis worldwide, and WHO has called for more actions to prevent disease. Many NCDs share four modifiable, behavioural risk factors: lack of physical activity, poor diet, tobacco use, and excessive consumption of alcohol. Improvements in these behaviours can prevent or delay the onset of disease (Lim 2012). One of the objectives in the WHO Global Action Plan for the Prevention of Noncommunicable Diseases deals with the need to address these four risk factors throughout populations, and mass media campaigns and social marketing initiatives are among the proposed policy options (WHO 2013a).

The WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health highlighted how "the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age" strongly determine health status and disease patterns within and between populations (CSDH 2008). This picture includes inequities in the morbidity and mortality patterns of NCDs (WHO 2010). In most countries, life expectancy and health status are correlated with social status, as measured by education, occupation, income, or wealth. The underlying forces behind this link include a wide array of unevenly distributed environmental, structural, economic, social, and cultural factors (CSDH 2008). Health inequities are not simply differences between groups, but differences that are considered both avoidable and unjust (Whitehead 1992). The Rio Political Declaration on Social Determinants of Health reaffirmed a global political commitment to reducing health inequities (WHO 2011).

Inequities in health status and disease risk are also associated with ethnic minority status. In many countries, ethnic minority groups tend to have poorer health outcomes than the majority population (Alderete 1999; Nielsen 2010; AHRQ 2013). Genetic variations only partially contribute to differences between ethnic groups in terms of disease patterns (Bhopal 2007). Differences in cultural factors (e.g. beliefs and practices) may influence health status, but social, economic and structural determinants of health during people's lifespans appear to be associated with health inequities between ethnic groups as well (Nazroo 2003; Mulia 2008; Viruell‐Fuentes 2012). Therefore, cultural influences should not be overemphasised as discrete explanatory factors for health inequities (Nazroo 2003; Acevedo‐Garcia 2012). Ethnic minority groups are heterogeneous, having wide‐ranging living conditions within and between countries, with consequently different health statuses and disease risks. The disease patterns of ethnic minorities may converge over time towards those of the majority population. However, health inequities between groups are sufficiently pronounced in many countries to warrant specific public health considerations.

Physical activity levels, dietary habits, tobacco use and alcohol consumption vary between population groups (WHO 2010). In many countries, unhealthy behaviours tend to be more prevalent in disadvantaged groups (Mackenbach 2008), and disparities in health behaviours have recently been shown to increase over time, as more privileged socioeconomic groups adopt healthier behaviours while disadvantaged groups lag behind (Buck 2012). Thus, although behaviours have an element of personal choice, behavioural patterns reveal the influence of the wider determinants of health.

Concern has been raised that public health interventions that have benefited the population overall might have increased inequities. This effect has been observed in public health interventions aimed at voluntary behavioural change in particular (Lorenc 2013). Public health campaigns delivered through mass media or by other means appear to be less effective in socioeconomically disadvantaged groups, whether for smoking cessation (Niederdeppe 2008a; Thomas 2008), physical activity (De Bourdeaudhuij 2011), or dietary factors (Oldroyd 2008; Stockley 2008). On the contrary, structural interventions, such as taxation of tobacco products and alcoholic beverages, appear more likely to reduce differences in health parameters (Lorenc 2013). It is therefore important to identify effective public health strategies that bridge the health gap rather than amplify it.

There are reasons to believe that mass media interventions can be less effective in reaching many ethnic minority groups as well, although few studies have systematically assessed the effects of these campaigns on ethnic minority groups (Niederdeppe 2008b; Durkin 2012; Bala 2013). The health behaviours of ethnic minority groups in different countries could be both more and less healthy than those of the majority population (e.g. the higher prevalence of smokers in some indigenous populations or lower alcohol consumption among Muslim immigrants). However, by describing ethnic minority health in relative terms only, we may fail to consider the absolute magnitude of a health problem or a health need that should guide public health priorities (Bhopal 2007). The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion declares that equal opportunities and resources to secure "access to information, life skills and opportunities for making healthy choices" are some of the prerequisites for health improvements (WHO 1986). Targeted mass media interventions are possible strategies to better disseminate health promotion messages among ethnic minorities (Webb 2010b; Gould 2013; Nierkens 2013), but their effectiveness has not been established.

There is no internationally agreed‐upon definition of ethnicity, but Bhopal 2007 has summarised some key points: "The concept of ethnicity is complex and implies, according to most accounts, one or more of the following: shared origins or social background; shared culture and traditions which are distinctive, maintained between generations, and lead to a sense of identity and group‐ness; a common language or religious tradition" (Bhopal 2007). Oxford Dictionaries defines an ethnic minority as "a group within a community which has different national or cultural traditions from the main population". Ethnic minority groups are sometimes divided into indigenous populations (SPFII 2004), national ethnic minorities (long‐time residents) (FCNM 2012), and immigrants. Through international migration, most countries gradually become more ethnically diverse. It is important to note that these definitions use social and cultural factors rather than biological ones (physical appearance or genetic differences) to define population groups (Bhopal 2007).

Ethnic minority status is associated with lower socioeconomic status in many countries, but ethnic identity and measures of socioeconomic status have different features. Programmes targeted to ethnic minorities should consider factors such as preferred language; food traditions; different norms, values and knowledge systems; patterns of media use; collective history; and position in the society. Arguably, then, it is appropriate to explore the effectiveness of mass media interventions targeted to ethnic minority groups as distinct from interventions directed at socioeconomically disadvantaged groups.

Description of the intervention

Targeted mass media interventions that promote healthier behaviours to reduce the risk of NCDs in adult ethnic minorities are the subject of this Cochrane Review. Public health authorities, health promotion agencies and non‐governmental organisations (NGOs) are the main providers of health promotion interventions. According to Ferri 2013, most mass media campaigns can be characterised as either information campaigns with messages of warning, empowerment or support, or social marketing campaigns that attempt to correct erroneous normative beliefs, clarify social and legal norms, or set positive role models or social norms. Designers of mass media interventions draw on a wide range of commercial marketing tools and principles. Health promotion campaigns partly overlap with social marketing, using concepts and approaches from marketing to influence behaviours to benefit individuals and communities for the social good (French 2010).

Kreuter 2003 describes a targeted health communication strategy as communication "intended to reach some population subgroup based on characteristics presumed to be shared by the group's members". They distinguish targeted from tailored communication, which is communication adapted to the specific characteristics of an individual. A targeted approach coincides with the principle of audience segmentation in social marketing theory, that is, the identification of meaningful differences among population groups that affect their responses to the promoted action. Thorough knowledge of the target audience is important for developing good combinations of strategic elements and approaches to achieve an intervention's goals (French 2010; MvVey 2010). Targeted communication strategies are only meaningful if the population subgroup is sufficiently homogeneous (Kreuter 2003; Castro 2010). Thus, communication targeted to broadly defined population subgroups, for instance the Latino population in the USA, may fail to recognise subcultures with different history, collective experiences, living conditions and health needs.

Interventions targeting ethnic minority groups should include cultural adaptations that consider "language, culture, and context in such a way that is comparable with the client's cultural patterns, meanings, and values" (Bernal 2009). Common strategies for cultural adaptation of health interventions include gathering information, user input, and feedback from the target group (Netto 2010; Barrera 2013). A targeted approach should also carefully consider ethical aspects to avoid stereotyping and stigmatising. Cultural adaptation strategies have been categorised into surface adjustments and deep, structural‐level adjustments. Surface‐level adjustments involve changing factors such as language, graphics, food, and clothing to match the target audience. Deep, structural‐level adjustments are changes that reflect the cultural, social, historical, environmental, and psychological forces behind behaviours in the target population (Resnicow 1999).

This review includes only health promotion interventions delivered via mass media. Brinn 2010 and Bala 2013 describe mass media as "channels of communication that intend to reach a large number of people without direct person‐to‐person contact". Mass media reach audiences through print material, recordings, broadcast, the Internet, and digital technology. Mass media interventions have the potential to cost effectively reach many people and can spread a message to remote geographical areas or groups that otherwise are difficult to access, or to target certain groups through selected media channels. Mass media channels have diversified quickly in the last couple of decades, including the development of digital communication technology, and national borders now pose fewer constraints on the reach of media channels.

Previous systematic reviews on mass media interventions or campaigns concerning public health issues (smoking cessation, HIV testing, health services utilisation, illicit drug use, mental health‐related stigma) have found that their effects on behavioural outcomes are either inconclusive or exhibit only modest short‐term effects (Grilli 2002; Vidanapathirana 2006; Brinn 2010; Bala 2013; Clement 2013; Ferri 2013). Long‐term effects are generally unclear. Modest effects of mass media interventions on an individual level can still have an important public health impact overall. The population strategy approach to disease prevention, as suggested by Rose 1985, aims to shift the distribution of a risk factor across entire populations. This shift includes the large proportion of the population with only a moderate risk of disease but a significant portion of the total disease burden.

How the intervention might work

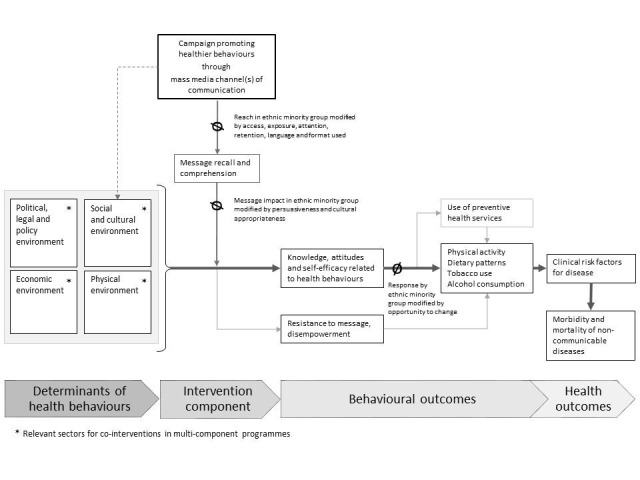

The evidence linking increased physical activity, balanced diets, avoidance of tobacco, and limited alcohol consumption to reduced morbidity and mortality from NCDs is well established (WHO 2009; WHO 2010; WHO 2013a; WHO 2013b; WHO 2014). The logic model in Figure 1 (adapted based on Bertrand 2006 and Niederdeppe 2008b) illustrates the possible elements and the relationships by which a targeted mass media intervention can influence these four health‐related behaviours. An additional desired outcome could be that individuals will consult health promotion services, such as smoking cessation assistance or health counselling.

1.

Logic model. Adapted based on Bertrand 2006 and Niederdeppe 2008b

Several theories and models seek to explain health behaviours on the individual level and to determine the most efficient way to influence these behaviours. These theories emphasise that increased knowledge is not sufficient to influence behaviour. Perceived barriers and risks are important moderators of behaviour, while attitudes and self‐efficacy contribute to a person's motivation and competence to act (Brewer 2008). In the logic model, changes in people's knowledge of and attitudes about health behaviours, in addition to self‐efficacy, are the measurable intermediate outcomes of mass media interventions. Contemporary thinking in public health and health promotion acknowledges that social norms, interpersonal interaction and the social and cultural environment influence individual behaviour strongly (Viswanath 2008). People's wider environment – physical, economic, political, legal and policy – may either enable or counteract a certain behaviour (McLeroy 1988; Davis 2014). A basic assumption in this Cochrane Review is that these theories and models are relevant to all population groups.

A mass media intervention can only influence health behaviours if the target audience receives, understands and can recall the message. Based on data and conceptual input (Sorensen 2004; Viswanath 2006; Niederdeppe 2008a), Niederdeppe 2008b has hypothesised that there are three possible sources of differences in response to smoking cessation campaigns that can be traced to socioeconomic status. These three domains probably apply to ethnic minorities as well and may be relevant to consider for targeted mass media interventions, as indicated in the logic model: differences in access, exposure, attention to and retention of the media message; differences in the message's persuasiveness and its motivational response; and differences in opportunities to change in response to the message (Niederdeppe 2008b).

Different media channels might be necessary to reach ethnic minorities, either because conventional media channels are less accessible or not preferred. The language and format of the content (language complexity, illustrations used, skills demonstration) can influence message recall and comprehension. Low health literacy levels, understood as low ability to obtain, process, and understand basic health information, have been identified in many ethnic minority groups and can influence response and compliance with health messages (Berkman 2011). Thus, planners must carefully consider media access, exposure, language and format, attention to and retention of the media message, making these relevant to the targeted ethnic minority group in order to extend the intervention reach.

The second domain relates to the persuasiveness of and motivational response to a message, which could strongly depend on its cultural appropriateness for ethnic minorities. Evidence from health promotion interventions via channels other than mass media have indicated better adherence to a promoted behavioural change when ethnic minorities receive culturally adapted health messages or counselling instead of a standard treatment (Nierkens 2013; Attridge 2014). The four health behaviours in this review relate closely to many markers of ethnic identity. The most obvious ones are dietary patterns and alcohol consumption, but physical activity and smoking patterns may also be closely related to cultural context.

Ethnic minorities might have limited opportunities to change health behaviours, either from a cultural, financial, or structural perspective. Previous reviews on the effect of mass media interventions for smoking cessation indicate that these are more likely to be successful as part of multicomponent programmes with upstream policy support and downstream community‐based activities (Brinn 2010; Bala 2013). Examples of relevant co‐interventions for this Cochrane Review include changes in legislation regarding advertising and taxation of food items, tobacco products, and alcoholic beverages, or changes in available spaces and social arenas for physical activity. Mass media interventions could have an indirect, amplifying effect if family, friends and the wider community adjust their attitudes, norms and behaviours according to the health message. Thus, multicomponent interventions can add benefits to efforts directed at individual change by modifying opportunities to change. Figure 1 indicates relevant sectors for co‐interventions in multicomponent programmes. The logic model also indicates possible unwanted effects of an intervention. Examples of adverse effects are increased resistance to the health promotion message or that the target population will experience more feelings of disempowerment when exposed to a goal they find difficult to achieve.

Why it is important to do this review

Mass media campaigns promoting healthy behaviours are one of several recommended policy options to prevent NCDs (WHO 2009; WHO 2013a), and most countries commonly use them to encourage healthier behaviours (WHO 2009; WHO 2013b; WHO 2014), despite the potentially limited effectiveness. The concern that mass media interventions could widen health inequities warrants more focus on the effect of targeted strategies in population subgroups. It is unclear whether targeted mass media interventions are more effective in changing health behaviours in ethnic minorities than a universal population strategy. This is important to explore, as segmentation of interventions to reach different subgroups may increase programme costs.

The Norwegian Directorate of Health and the Norwegian Cancer Society commissioned a systematic review on this issue to inform public health policy on how to deliver health promotion messages to the growing and increasingly diverse immigrant population. This systematic review has been widened to encompass an international perspective, including a wide focus on ethnic minority groups, as the question may be useful for other national authorities and NGOs as well.

The primary focus of this Cochrane Review is the mode of delivery (mass media intervention) and the strategies used to target such interventions to ethnic minority groups and prevention of NCDs, rather than any of the four specific health behaviours separately. The four behaviours have distinct features and require different messages regarding the suggested action (i.e. to increase physical activity, modify diets, decrease alcohol consumption, or refrain from smoking). At the same time, the behaviours are similar in their focus on preventing negative health outcomes in the future. Thus, the target audience may be less motivated to change ingrained habits in favour of longer‐term – and hence more uncertain – benefits. Our objectives intersect with two Cochrane Reviews on mass media interventions for smoking cessation (Brinn 2010; Bala 2013). Two other systematic reviews have examined the effects of smoking cessation interventions in indigenous populations but are not limited to mass media interventions (Carson 2012a; Carson 2012b). Our objectives include interventions focusing on tobacco use to obtain a full picture of mass media strategies as a means of disseminating health‐promoting messages among ethnic minorities. We gathered additional information on features of these interventions, theoretical frameworks and co‐interventions.

Objectives

Primary

• To determine the effect of mass media interventions targeting adult, ethnic minorities with messages about physical activity, dietary patterns, tobacco use or alcohol consumption to reduce risk of NCDs.

Secondary

• To examine the effect of targeted mass media interventions alone compared to targeted mass media interventions given as part of multi‐component interventions.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

By definition, mass media communication strategies target large groups of people. Individually randomised controlled trials (RCTs) may be neither the most appropriate nor most feasible study design. Therefore, we included the following study designs and specified features, guided by recommendations from the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group (EPOC) review group (EPOC 2016).

RCTs.

Cluster‐RCTs with at least two intervention groups and two control groups.

Non‐RCTs (NRCTs) with at least two intervention sites and two control sites.

Controlled before‐and‐after (CBA) studies with at least two intervention sites and two control sites.

Interrupted‐time‐series (ITS) or repeated measures studies (RMSs) with a clearly defined point in time when the intervention occurred and at least three data points before and three after the intervention.

Types of participants

The population of interest was adults (≥ 18 years) described as being from an ethnic minority group in their country of residence. We use the terms ethnicity and ethnic minorities as described in the Background but did not limit the eligibility of participants to studies using these terms. Different countries and research traditions have dissimilar terminology relating to aspects of ethnicity (Bhopal 2007). Not all use the terms ethnicity and ethnic minorities. We based inclusion on any direct or implicit description by the study authors that the study participants were selected based on ethnic minority characteristics and that the intervention was targeted to such a population group. Examples of applicable terms are indigenous populations, native, aboriginal, racial groups, immigrants, ancestral origin (countries or continents), countries of birth, or specified first language/mother tongue/language preference.

Types of interventions

To be eligible for inclusion, the intervention had to meet all of the following three criteria.

The purpose of the intervention was to promote healthier behaviours related to physical activity, dietary patterns, tobacco use, or alcohol consumption.

The intervention was disseminated via a mass media channel.

The intervention was targeted to an ethnic minority group.

We used the same definition of mass media as in two related Cochrane Reviews (Brinn 2010; Bala 2013): "Mass media is defined here as channels of communication such as television, radio, newspapers, billboards, posters, leaflets or booklets intended to reach large numbers of people and which are not dependent on person‐to‐person contact". In addition, we aimed to include other contemporary mass media channels, such as campaigns delivered through the Internet, social media, and mass distribution through mobile phones. We used the definition by Kreuter 2003 for targeted interventions but did not limit the inclusion to studies using the same terminology.

We included studies that compared the intervention with a general population mass media intervention, no intervention or any other intervention. We included studies that compared targeted mass media interventions alone with targeted mass media interventions delivered as part of multicomponent interventions to explore the secondary research objective.

There were no set requirements on minimum length of intervention.

We excluded the following interventions.

Courses, teaching activities and programmes, interactive self‐help programmes or self‐monitoring services, as these are not considered mass media interventions even though they can be delivered through the Internet, digital applications, or similar media.

Interventions with mass distributed print, audio, or visual material where the content has been tailored/personalised to each individual (i.e. based on answers from questionnaires or similar information sources).

Interventions for patient groups/patient education (including treatment of alcohol dependency and eating disorders), or interventions aimed specifically at relatives of patients.

Types of outcome measures

We did not expect to find any studies of targeted mass media interventions using morbidity or mortality of NCDs as outcome measures, nor clinical risk factors of disease. We intended to examine a number of surrogate endpoints relating to the four specified health behaviours as primary outcomes as relevant, including both objectively measured and self‐reported outcomes.

There was no requirement for a minimum duration of follow‐up for the outcome measures. We intended to present outcomes separately for short‐term (< six months) and long‐term ( ≥ six months) follow‐up.

Primary outcomes

Physiological or clinical parameters that indicate changes in physical activity, dietary intake, use of tobacco, or alcohol consumption

Objective or self‐reported measurements of physical activity, dietary intake, use of tobacco, or alcohol consumption

Measures of knowledge and attitudes concerning physical activity, dietary intake, use of tobacco, or alcohol consumption

Secondary outcomes

Use of health promotion services (for instance smoking quit lines and counselling) or other relevant services

Costs related to the project

Adverse outcomes

Any reported outcome considered an adverse effect, such as measures of participants' resistance to the health promotion message or measures of perceived disempowerment in participants.

Search methods for identification of studies

A research librarian conducted the electronic literature searches.

Electronic searches

We performed a scoping search to identify any systematic reviews in the last five years with a similar primary research objective. We based the search terms on the strategy described in Appendix 1 but with a filter for systematic reviews. We searched the following electronic databases from the beginning of 2009 until September 2014.

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, part of the Cochrane Library (www.thecochranelibrary.com).

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), part of the Cochrane Library (www.thecochranelibrary.com).

Health Technology Assessment Database (HTA), part of the Cochrane Library (www.thecochranelibrary.com).

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (DARE, HTA).

We did not identify any systematic reviews with a similar research objective. As previously described, we are aware of that four Cochrane systematic reviews intersect with the objectives of this Cochrane Review (Brinn 2010; Carson 2012a; Carson 2012b; Bala 2013).

We searched for primary studies without any time limitations or language restrictions on 22 May 2015 and later updated the search to 23 August 2016. We present the search strategies in Appendix 1. We modified the search strategy, subject headings, and syntax to each database and searched the following databases.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2016; Issue 7), part of the Cochrane Library.

MEDLINE Ovid (from 1946).

PubMed (from 1946).

Embase Ovid (from 1974).

PsycINFO Ovid (from 1806).

CINAHL EBSCO (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; from 1981).

ERIC EBSCO (from 1966).

SweMed+ (from 1977).

ISI Web of Science (from 1987).

After merging the databases from each search into the reference management software Endnote 2015, the librarian removed studies retrieved in duplicate.

Searching other resources

We screened related systematic reviews, as found in the scoping search, for relevant primary studies. We also conducted cited reference searches for all included studies using ISI Web of Knowledge and screened their reference lists.

Trial registries

We searched the following websites to 19 October 2016.

WHO International Clinical Trials Search Portal (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch).

ClinicalTrials.gov (http://clinicaltrials.gov).

Grey literature

We searched the following websites to 19 October 2016.

OpenGrey (www.opengrey.eu).

Grey Literature Report (www.greylit.org).

Eldis (www.eldis.org).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors screened titles and abstracts independently (AM with either IBL or GEV). We retrieved the full text of all potentially relevant studies. Two review authors (AM with either IBL or GEV) independently assessed these for eligibility using a checklist. At each stage, we resolved any disagreement by discussion or consensus with a third review author. The project group read articles in English, Scandinavian languages and German. Staff members at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health read other languages or considered them for translation. We list the studies excluded based on full‐text assessment in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

We extracted data using a form based on the Data Extraction and Assessment Template from the Cochrane Public Health Group (CPHG). This data extraction form embeds items relating to the PROGRESS‐Plus criteria and the PRISMA‐Equity 2012 Extension (Tugwell 2010; Welch 2012). We revised the form before data extraction. One review author retrieved the specified information and data from the included studies, and another review author checked data extraction. We resolved any disagreements by discussion or consensus with a third review author. We contacted the study authors if key information was missing. We entered the extracted data into RevMan 2014 as appropriate.

When more than one publication referred to the same study, we used the relevant paper with the most comprehensive and clear description of methods and outcome reports from a peer‐reviewed journal as the primary reference. If necessary, we used all papers from one study to extract the relevant information. We contacted investigators in cases of contradiction or incomplete reporting.

In addition to the items from the Data Extraction and Assessment Template, which included descriptions of study details (reference, design), participants, setting, intervention, outcomes, and adverse outcomes, we also extracted the following information when available.

Context of the intervention (sociodemographic, organisational, political, media structure).

Content of the message (health behaviour targeted).

Theoretical basis of the intervention, including message development and framing.

Theoretical basis for how the intervention and message were adapted to the target population.

Media channel(s) used for delivery and frequency of exposure.

Intervention fidelity (whether the intervention was delivered as planned).

Information on the nature and extent of any additional actions given as part of the intervention (co‐interventions).

Intervention costs.

Source of funding.

We present these data in the Characteristics of included studies section.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the included studies with respect to risk of bias (AM, GEV). We assessed all study designs using the suggested 'Risk of bias' criteria for EPOC reviews (EPOC 2015). There are nine standard criteria for RCTs, cluster‐RCTs, NRCTs, and CBAs: adequate generation of allocation sequence; adequate allocation concealment; similar baseline outcome measurements; similar baseline characteristics; adequate handling of incomplete outcome data; adequate prevention of knowledge of the allocated interventions during the study; adequate protection against contamination; freedom from selective outcome reporting; and other risks of bias. For ITS studies we considered the following criteria: intervention independent of other changes, shape of the intervention effect pre‐specified, intervention unlikely to affect data collection, knowledge of the allocated intervention adequately prevented during the study, incomplete outcome data adequately addressed, study free from selective outcome reporting, and any other risks of bias. We resolved any disagreement in the assessment between the two review authors by discussion. We assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias on the findings.

Measures of treatment effect

If possible, we presented continuous outcomes with mean difference and standard deviations. When studies had measured the same outcome using different instruments or scales, we considered combining the outcomes using the standardised mean difference. We did not consider any of the outcomes to be appropriate for such a combination. For dichotomous outcomes, where available from RCTs, cluster‐RCTs, NRCTs, and CBA studies, we intended to present the number of events and number of people in groups as proportions and if appropriate, express effect as relative risk ratio (RR) or odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

For ITS studies, we present the effect as the difference between the expected value at a given point in time based on the pre‐intervention trend and the expected value at the same point in time based on the postintervention trend. We contacted authors of Kennedy 2013, who provided the original data set for re‐analysis as an ITS for this review as described in EPOC 2013.

We present results from randomised studies, non‐randomised studies and ITS separately, as recommended (Higgins 2011). We present the follow‐up according to our predefined categories: short‐term (< six months) and long‐term ( ≥ six months) follow‐up. Where study authors report several follow‐up times from the same study, we present the longest follow‐up.

Unit of analysis issues

Unit of analysis error can occur if trials based on group allocation to treatment condition (cluster‐RCTs, NRCTs, and CBA studies) have not accounted for the effect of clustering in the statistical analyses. The included cluster‐RCT by Boyd 1998 did not adjust the results for the effect of clustering, while Jih 2016 did. We did not have sufficient information to re‐analyse the data by Boyd 1998. See Appendix 2 for the methods we intended to use.

Dealing with missing data

We consider that incomplete or missing data was not a problem in any of the included studies and thus did not contact any of the authors for such information. See Appendix 2 for the methods we intended to use.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We did not combine data in meta‐analysis and hence did not assess heterogeneity in the results. See Appendix 2 for the methods we intended to use.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to generate funnel plots if 10 or more studies reported the same outcome. See Appendix 2 for the methods we intended to use.

Data synthesis

We categorised the included studies according to the intervention, measures and comparisons made. We assessed results for each comparison and collated them separately. If population, study design, intervention, and outcome measures had been similar enough across studies, we could have conducted meta‐analyses using Review Manager 5 (RevMan) software (RevMan 2014). One comparison had only one included study. Otherwise, the interventions, outcome measurements, or study designs differed in ways that did not support meta‐analyses. We based our judgements on the recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We considered that one outcome had sufficiently homogeneous populations, interventions, and comparisons to consider a pooled risk ratio, but only one of these two studies reported a measurement of dispersion in the published paper. See Appendix 2 for the methods we intended to use for meta‐analyses. Since meta‐analysis was not appropriate, we present descriptive data in text and tables. Authors of Kennedy 2013 provided data so we could re‐analyse these results as an ITS through segmented time series regression (Ramsay 2003).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

The included studies did not provide sufficient data for subgroup analyses or investigation of heterogeneity. See Appendix 2 for the methods we intended to use and planned subgroups.

Sensitivity analysis

We intended to perform a sensitivity analysis excluding studies at high risk of bias if there had been a sufficient number of included studies; see Appendix 2.

Summary of findings table

We present the main outcome measures in a 'Summary of findings' table, along with our assessment of the certainty of effect for each outcome using the GRADE methodology (Guyatt 2011). Using GRADE, we reflect on the extent to which we have confidence that the estimates of effect are correct. Our confidence is presented as either high, moderate, low or very low quality evidence. We assess the results for each outcome measure against eight criteria. We consider the first five criteria for possible downgrading of the quality of documentation: study quality (risk of bias), consistency (consistency between studies), directness (the same study participants, intervention, comparator and outcome measures in included studies for the population, measures and outcomes we wanted to study), precision of results, and reporting biases. Results can be upgraded by three criteria: strong or very strong associations between intervention and outcome; large or very large dose‐response effect; and situations where all plausible confounders would have reduced the effect.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

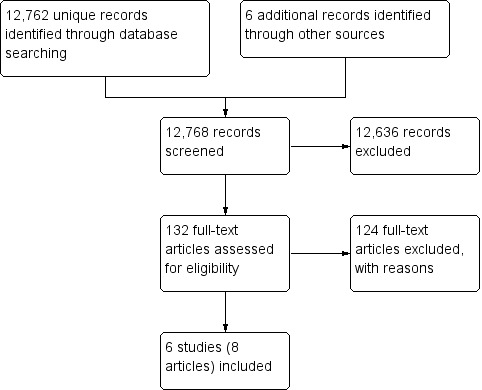

Searches in the electronic databases identified 12,762 unique records (see Figure 2: Study flow diagram). We discovered six additional records through other sources. Based on screening of titles and abstracts, we excluded 12,636 records and retrieved the full text of 132 articles, excluding 124. Six studies (8 articles) were eligible for this review. We did not identify any ongoing studies.

2.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Of the included studies, three were individual RCTs (Elder 2005; Webb 2009; Risica 2013), and two were cluster‐RCTs (Boyd 1998; Jih 2016). We obtained the original data from the authors of Kennedy 2013 and were able to re‐analyse this study as an ITS. All of the studies took place in the USA and were published between 1998 and 2016. In four studies, the interventions targeted groups self‐described as Americans of African heritage (Boyd 1998; Webb 2009; Kennedy 2013; Risica 2013), while Elder 2005 targeted Spanish‐language‐dominant Latino immigrants (95% born in Mexico), and Jih 2016, elderly people of Chinese ethnicity (predominantly foreign‐born). Three studies targeted women only (Elder 2005; Kennedy 2013; Risica 2013). In Boyd 1998 and Kennedy 2013, the entire populations of geographically defined areas were potentially exposed to the targeted mass media intervention. The objectives of the interventions were to promote smoking cessation (Boyd 1998; Webb 2009; Kennedy 2013); to encourage dietary changes (particularly regarding fibre and fat intake) (Elder 2005); to promote weight management through modifications to diet and physical activity (Risica 2013); or to increase vegetable intake, fruit intake, and physical activity levels to meet guidelines (Jih 2016). None of the studies examined alcohol intake.

Webb 2009 recruited 261 African American adults who were randomised to receive either a culturally specific smoking cessation booklet or a booklet intended for the general population. The booklet in the intervention arm was culturally adapted using values, communication patterns, statistics, pictures, and other elements considered relevant for the targeted population, and it contained information about smoking and quitting strategies. The booklet used for the control group was identical in format and content and was developed by removing any references to a specific population group and using more general information and graphics.

In Boyd 1998 and Kennedy 2013, the intervention consisted of paid radio advisements, and in Boyd 1998, also some television advertisements, aired repeatedly in two waves that varied from three to six weeks in length. Both studies also included substantial distributions of posters, flyers, and other types of small media. The investigators targeted African American communities by adapting their message, language, and format to the assumed preferences of the group and by user‐testing the intervention with the target population. Advertisements were aired through media channels popular with the target audience or placed in relevant residential areas. The comparator in both studies was no intervention. The main message was to quit smoking and to make use of free telephone smoking cessation information or counselling (quit lines). Calls to this service were also the studies' outcome measurement. Since these studies exposed whole populations to the intervention, the study populations were not fixed. Boyd 1998's targeted mass media intervention was run in seven communities (estimated 310,471 African American smokers), compared to no intervention in seven communities (estimated 331,360 African American smokers). The size of Kennedy 2013's target population was indicated by the 400 births per month among African American women in the catchment area and survey results showing that approximately 40% of pregnant women in this population group were recent smokers.

The study by Risica 2013 gave study participants access to 12, one‐hour live programmes on cable TV over three months, biweekly mailings with printed material corresponding to the shows and, afterwards, four monthly mailings with written material and booster videotapes. The material was culturally adapted based on formative research on the target population. The TV shows had African American female casts, including all experts used. The shows and material contained educational content regarding nutrition and physical activity to improve health and control weight. In total, 71 women received this targeted intervention compared to 82 women on a wait‐list control until the study ended. Another 214 women received both this targeted intervention and the opportunity to engage in personal contact with study staff, either access to a toll‐free number they could use to ask questions during the live‐sharing segments of the shows, and/or weekly telephone support calls with outreach educators. Thus, this study compared the targeted mass media intervention with both a no‐intervention control group and a group receiving the mass media intervention with additional personalised content.

The target mass media intervention in Elder 2005 comprised newsletters in Spanish, mailed to the participants' home (119 women). The targeted newsletters and activity inserts were based on off‐the‐shelf information material developed for the Latino population and contained suggested strategies to change food purchasing, food preparation, and food consumption to reduce the risk of NCDs. This targeted intervention was compared to personalised newsletters and activity inserts in Spanish that were based on baseline questionnaires and specified personal goals. The personalised newsletters (118 women) otherwise focused on the same dietary messages as the targeted materials. A third intervention group (120 women) received both the personalised newsletters and 12 weekly visits by a Spanish‐speeking lay health worker (LHW, called promotora) who reinforced the dietary messages. Similarly, Jih 2016 compared targeted lecture handouts and brochures in 357 participants to the same material delivered through two small‐group, LHW‐facilitated lectures in 361 participants. The main aim was to increase fruit and vegetable intake and physical activity levels to meet guidelines. The researchers developed the lectures and materials using culturally appropriate examples of common foods, relevant physical activities and familiar portion size models for the target group. The lectures were presented in the participants' preferred language (Cantonese, Mandarin, or English).

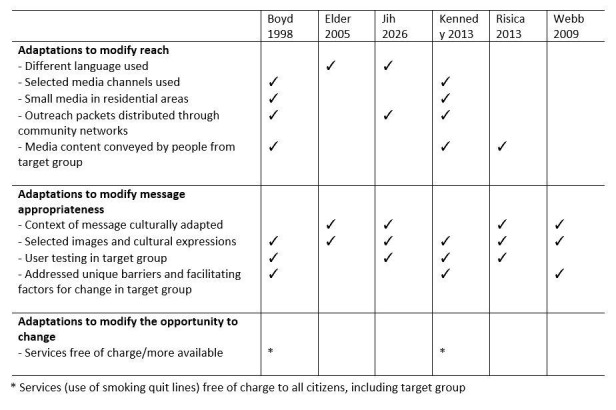

Figure 3 presents an overview of the strategies that the included studies used to adapt their interventions to the target populations. The strategies are categorised according to the logic model (Figure 1). All of the studies made adaptations to modify message appropriateness, including adapting the message to be culturally appropriate, using selected images or cultural expressions, user‐testing the intervention in the target group, or attempting to address unique barriers and facilitating factors for group change. Two campaigns were implemented in a real context and made adaptations to modify reach by using selected media channels, placing small media in residential areas, distributing outreach packets through community networks, and using people from the target group to convey the media content (Boyd 1998; Kennedy 2013). Two studies presented the mass media interventions in languages that differed from the dominant language of the country (Elder 2005, Jih 2016).

3.

Approaches used in the included studies to target the intervention to the study population, by categories according to logic model.

Three of the included studies received support from the National Cancer Institute (USA) (Boyd 1998; Elder 2005; Risica 2013), and one received funding from both the National Institutes of Health and the National Cancer Institute (Jih 2016). The National Center on Minority Health Disparities, part of the National Institutes of Health (USA), supported Kennedy 2013, and Syracuse University (USA) funded Webb 2009.

Excluded studies

After screening the full texts, we excluded 124 articles (see Characteristics of excluded studies). The main reasons for exclusion were: no mass media intervention or combining the media various forms of personal interaction with the participants; not targeting the intervention to ethnic minorities; or not meeting the inclusion criteria with respect to study design.

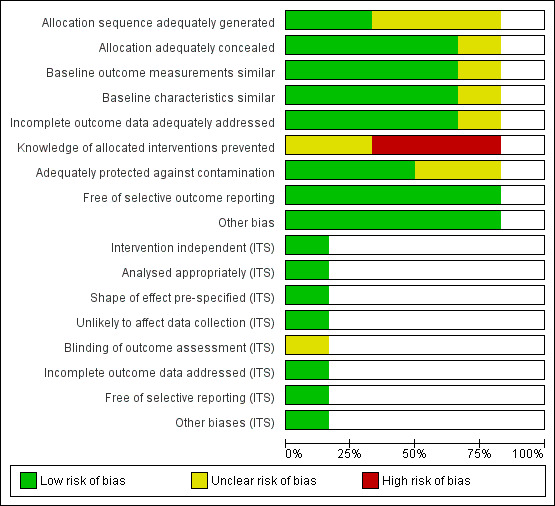

Risk of bias in included studies

The Characteristics of included studies table assesses the risk of bias and provides comments for each of the included studies. We used the study‐appropriate risk of bias domains as developed by EPOC 2015, which proposes different domains for assessing ITS studies and the other study designs included in this review. The risk of bias assessment for the ITS study is discussed under the section Other potential sources of bias. Figure 4 and Figure 5 summarise the 'Risk of bias' assessments. These figures present all domains used for both the ITS study and the other study designs but are only filled in for the appropriate categories for each study.

4.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

5.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Two studies reported adequate methods for random sequence allocation (Risica 2013; Jih 2016). Otherwise, the allocation method described in the papers was unclear. We also considered that the method used for allocation concealment in Webb 2009 was at unclear risk of bias. Four studies presented data showing that the groups were similar at baseline with regard to the outcome variables and the participant characteristics (Elder 2005; Webb 2009; Risica 2013; Jih 2016). In Boyd 1998, the communities were matched on selected characteristics before randomisation, but based on the published descriptions we found the distribution of the baseline characteristics to be unclear.

Blinding

It can be difficult to achieve blinding in studies intending to change behaviours. Since most or all the outcomes in Elder 2005, Risica 2013, and Jih 2016 were self‐reported outcomes from non‐blinded studies, we considered these results to be at high risk of bias. In Webb 2009, participants in both study arms received a non‐blinded smoking cessation intervention; we could not tell whether the trial misreported any of the study outcomes with unequal distribution between the groups. Kennedy 2013 reported on a whole‐population mass media campaign, and we considered it to be unclear whether knowledge of the allocated intervention was adequately prevented during the study and in what way this may have biased the findings.

Incomplete outcome data

Loss to follow‐up was unaccounted for in Webb 2009, so we consider the risk of bias to be unclear.

Selective reporting

We found no published study protocols for any of the studies but considered the risk for selective reporting of outcomes to be low in all the studies. This conclusion is based on descriptions in the Methods, expected outcomes reported, and corresponding presentations of results.

Other potential sources of bias

We considered the included studies to be at low risk of other biases.

We re‐analysed Kennedy 2013 as an ITS for this systematic review using the methodology described above. We noted that the second wave of advertisements coincided with a known seasonal increase in call volume and therefore excluded these data from the re‐analysis. We considered the remaining results, as re‐analysed according to the EPOC methods for ITS studies, to be at low risk of bias in all domains except one. As with the study by Boyd 1998, it was unclear whether knowledge of the allocated intervention in Kennedy 2013 (whole population mass media campaign) was adequately prevented during the study and in what way this may have biased the findings.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Comparison 1: targeted mass media intervention versus general population mass media intervention

See: Table 1.

Only one study assessed the effect of a targeted mass media intervention versus a mass media intervention intended for the general population (Webb 2009).

Primary outcomes

Webb 2009 did not assess any outcomes using indicators of behavioural change but reported several self‐reported measures, including smoking reduction, attempts to quit, 24‐hour point prevalence abstinence and 7‐day point prevalence abstinence. The authors report that they found no significant difference in smoking reduction between the two conditions at the three‐month follow‐up (94% and 95% reported smoking reduction; adjusted OR for quit attempts was 1.97 (95% CI 1.09 to 3.55) in favour of the general population mass media intervention). Knowledge and attitudes toward change were reported as readiness to quit, measured by a 10‐point contemplation ladder (1: no thoughts of quitting; 10: taking action to quit). The mean score was higher in participants who received the mass media intervention intended for the general population compared to the targeted mass media intervention (8.2 points, SD 2.4 versus 7.3 points, SD 2.6, P = 0.01). We considered all effect estimates of these self‐reported behavioural outcome measures to be very low quality evidence as assessed by the GRADE methodology.

Secondary outcomes

The included study did not assess any outcomes on the use of health promotion services or costs of the project.

Adverse outcomes

The included study did not assess any variables measuring adverse outcomes.

Comparison 2: targeted mass media intervention versus no intervention

See: Table 2.

Three studies compared targeted mass media interventions versus no intervention (Boyd 1998; Kennedy 2013; Risica 2013). We could not pool the findings due to differences in outcome measurements and study designs.

Primary outcome

Only one of the included studies reported any of our primary outcomes (Risica 2013). These were: BMI (kg/m2) as an indicator of behavioural change and self‐reported behavioural change using a Food Habits Questionnaire (fat behaviour score) and total leisure activity questionnaire. The included study did not assess knowledge or attitudes toward change.