Abstract

Background

Mother‐infant separation post birth is common. In standard hospital care, newborn infants are held wrapped or dressed in their mother’s arms, placed in open cribs or under radiant warmers. Skin‐to‐skin contact (SSC) begins ideally at birth and should last continually until the end of the first breastfeeding. SSC involves placing the dried, naked baby prone on the mother's bare chest, often covered with a warm blanket. According to mammalian neuroscience, the intimate contact inherent in this place (habitat) evokes neuro‐behaviors ensuring fulfillment of basic biological needs. This time frame immediately post birth may represent a 'sensitive period' for programming future physiology and behavior.

Objectives

To assess the effects of immediate or early SSC for healthy newborn infants compared to standard contact on establishment and maintenance of breastfeeding and infant physiology.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (17 December 2015), made personal contact with trialists, consulted the bibliography on kangaroo mother care (KMC) maintained by Dr Susan Ludington, and reviewed reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials that compared immediate or early SSC with usual hospital care.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trials for inclusion and risk of bias, extracted data and checked them for accuracy. Quality of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach.

Main results

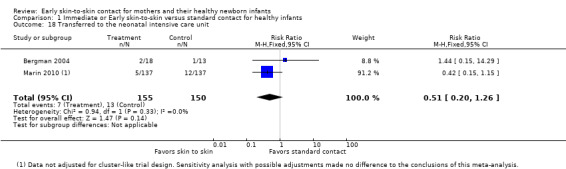

We included 46 trials with 3850 women and their infants; 38 trials with 3472 women and infants contributed data to our analyses. Trials took place in 21 countries, and most recruited small samples (just 12 trials randomized more than 100 women). Eight trials included women who had SSC after cesarean birth. All infants recruited to trials were healthy, and the majority were full term. Six trials studied late preterm infants (greater than 35 weeks' gestation). No included trial met all criteria for good quality with respect to methodology and reporting; no trial was successfully blinded, and all analyses were imprecise due to small sample size. Many analyses had statistical heterogeneity due to considerable differences between SSC and standard care control groups.

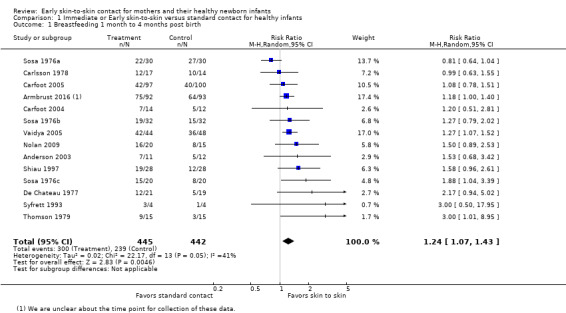

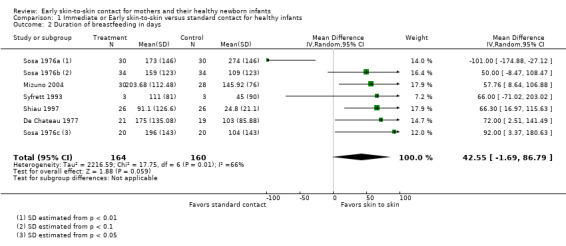

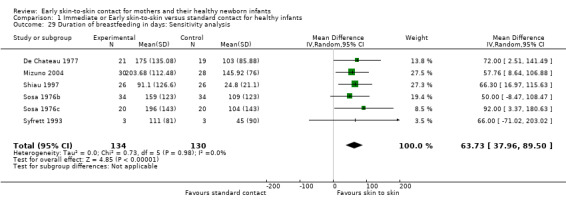

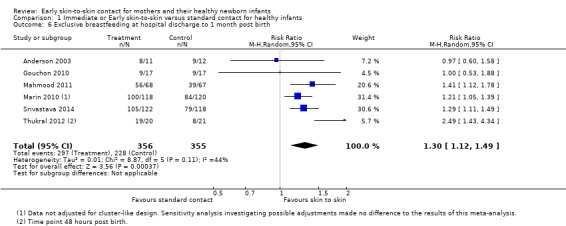

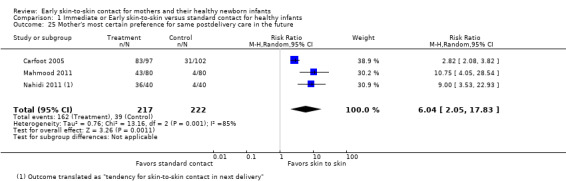

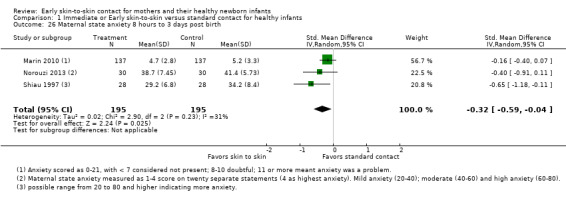

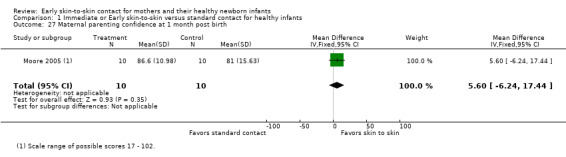

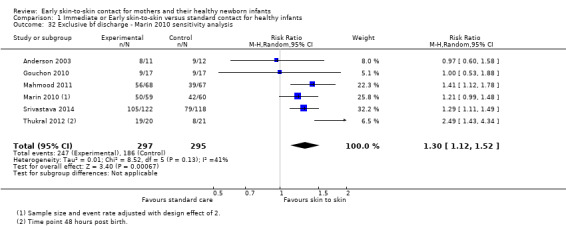

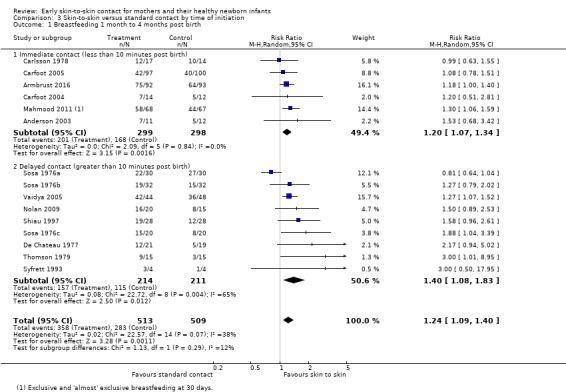

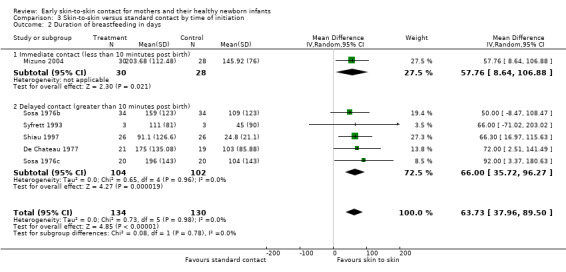

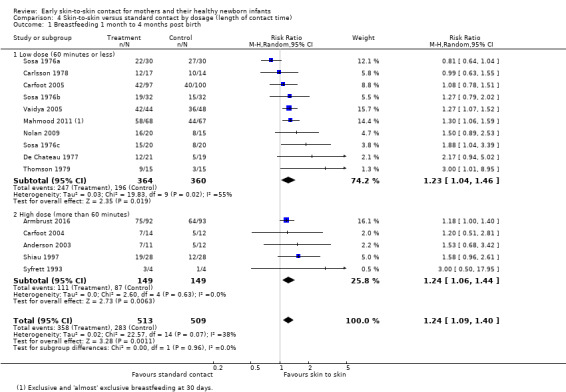

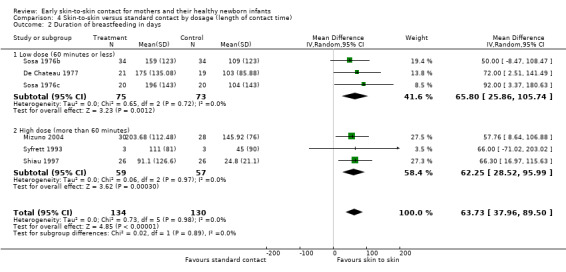

Results for women

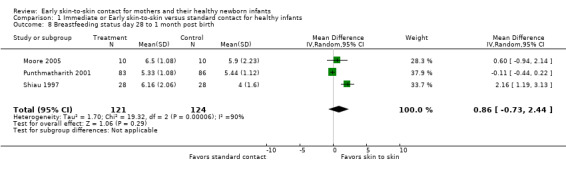

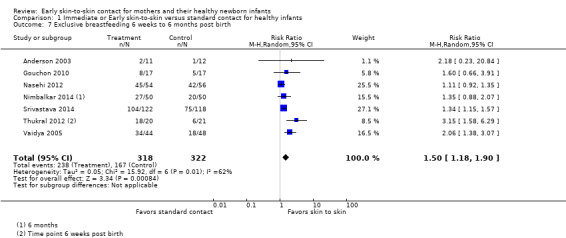

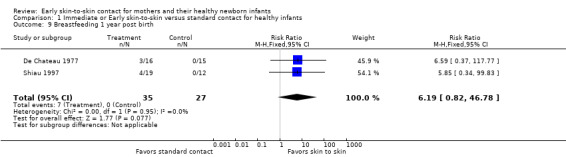

SSC women were more likely than women with standard contact to be breastfeeding at one to four months post birth, though there was some uncertainty in this estimate due to risks of bias in included trials (average risk ratio (RR) 1.24, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.07 to 1.43; participants = 887; studies = 14; I² = 41%; GRADE: moderate quality). SSC women also breast fed their infants longer, though data were limited (mean difference (MD) 64 days, 95% CI 37.96 to 89.50; participants = 264; studies = six; GRADE:low quality); this result was from a sensitivity analysis excluding one trial contributing all of the heterogeneity in the primary analysis. SSC women were probably more likely to exclusively breast feed from hospital discharge to one month post birth and from six weeks to six months post birth, though both analyses had substantial heterogeneity (from discharge average RR 1.30, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.49; participants = 711; studies = six; I² = 44%; GRADE: moderate quality; from six weeks average RR 1.50, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.90; participants = 640; studies = seven; I² = 62%; GRADE: moderate quality).

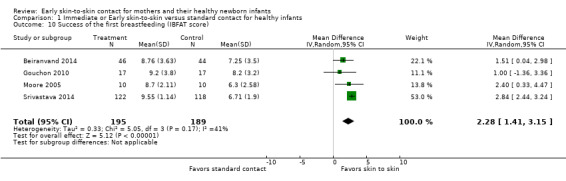

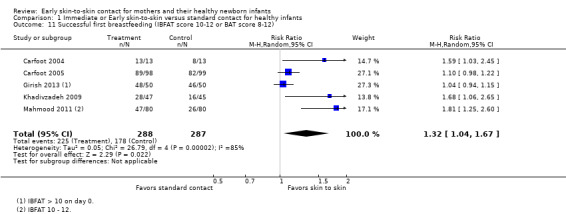

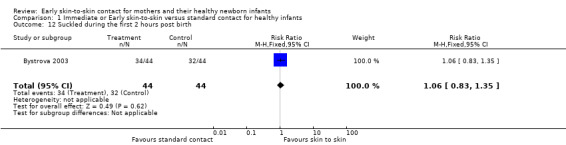

Women in the SCC group had higher mean scores for breastfeeding effectiveness, with moderate heterogeneity (IBFAT (Infant Breastfeeding Assessment Tool) score MD 2.28, 95% CI 1.41 to 3.15; participants = 384; studies = four; I² = 41%). SSC infants were more likely to breast feed successfully during their first feed, with high heterogeneity (average RR 1.32, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.67; participants = 575; studies = five; I² = 85%).

Results for infants

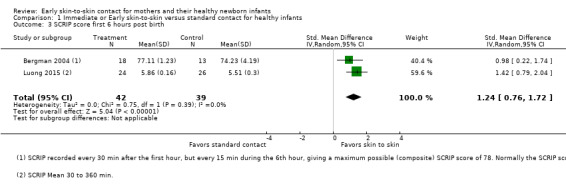

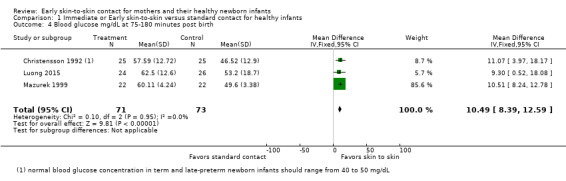

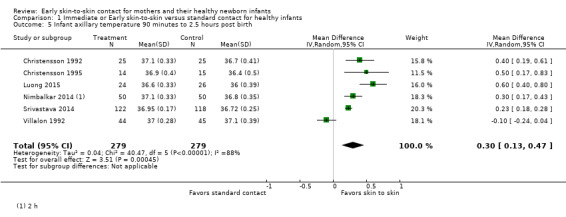

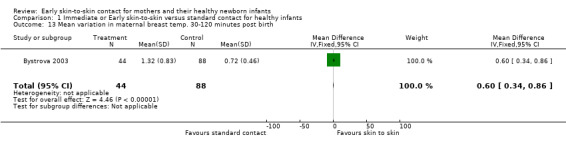

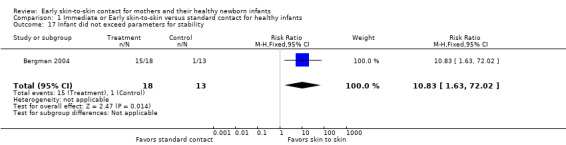

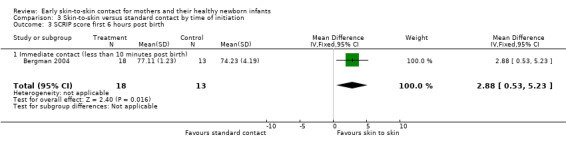

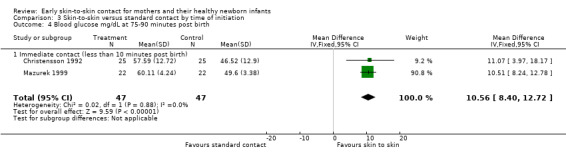

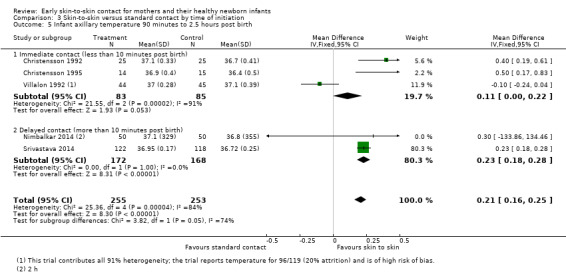

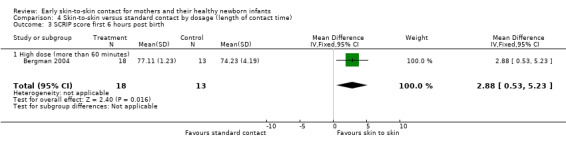

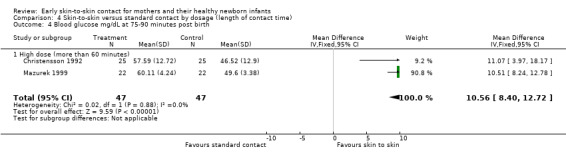

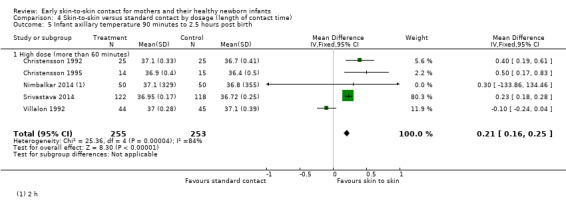

SSC infants had higher SCRIP (stability of the cardio‐respiratory system) scores overall, suggesting better stabilization on three physiological parameters. However, there were few infants, and the clinical significance of the test was unclear because trialists reported averages of multiple time points (standardized mean difference (SMD) 1.24, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.72; participants = 81; studies = two; GRADE low quality). SSC infants had higher blood glucose levels (MD 10.49, 95% CI 8.39 to 12.59; participants = 144; studies = three; GRADE: low quality), but similar temperature to infants in standard care (MD 0.30 degree Celcius (°C) 95% CI 0.13 °C to 0.47 °C; participants = 558; studies = six; I² = 88%; GRADE: low quality).

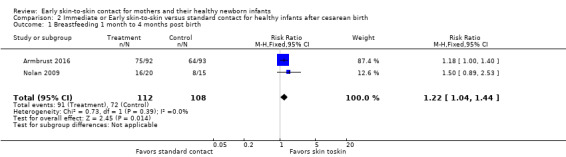

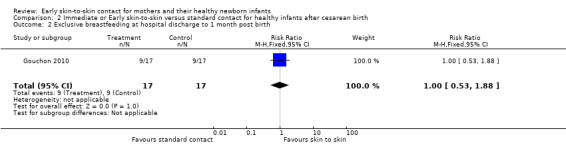

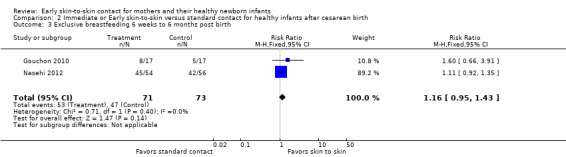

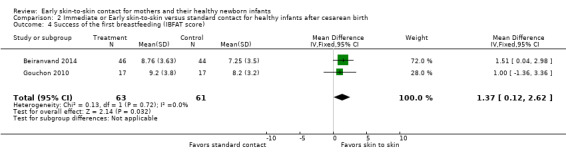

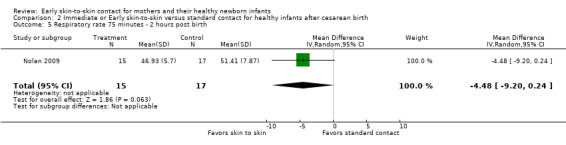

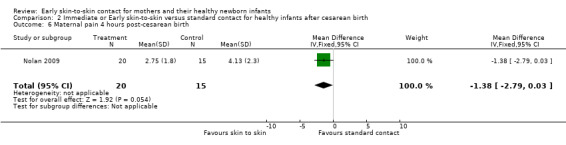

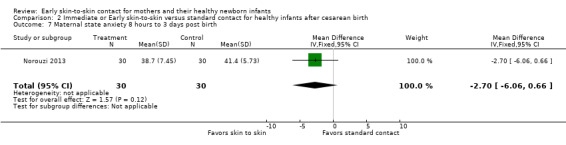

Women and infants after cesarean birth

Women practicing SSC after cesarean birth were probably more likely to breast feed one to four months post birth and to breast feed successfully (IBFAT score), but analyses were based on just two trials and few women. Evidence was insufficient to determine whether SSC could improve breastfeeding at other times after cesarean. Single trials contributed to infant respiratory rate, maternal pain and maternal state anxiety with no power to detect group differences.

Subgroups

We found no differences for any outcome when we compared times of initiation (immediate less than 10 minutes post birth versus early 10 minutes or more post birth) or lengths of contact time (60 minutes or less contact versus more than 60 minutes contact).

Authors' conclusions

Evidence supports the use of SSC to promote breastfeeding. Studies with larger sample sizes are necessary to confirm physiological benefit for infants during transition to extra‐uterine life and to establish possible dose‐response effects and optimal initiation time. Methodological quality of trials remains problematic, and small trials reporting different outcomes with different scales and limited data limit our confidence in the benefits of SSC for infants. Our review included only healthy infants, which limits the range of physiological parameters observed and makes their interpretation difficult.

Plain language summary

Early skin‐to‐skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants

What is the issue?

Babies are often separated from their mothers at birth. In standard hospital care, newborn infants can be held wrapped or dressed in their mother’s arms, placed in open cribs or under warmers. In skin‐to‐skin contact (SSC), the newborn infant is placed naked on the mother's bare chest at birth or soon afterwards. Immediate SSC means within 10 minutes of birth while early SSC means between 10 minutes and 24 hours after birth. We wanted to know if immediate or early SSC improved breastfeeding for mothers and babies, and improved the transition to the outside world for babies.

Why is this important?

There are well‐known benefits to breastfeeding for women and their babies. We wanted to know if immediate or early SSC could improve women's chances of successfully breastfeeding. Having early contact may also help keep babies warm and calm and improve other aspects of a baby's transition to life outside the womb.

What evidence did we find?

We searched for randomized controlled studies of immediate and early SSC on 17 December 2015. We found thirty‐eight studies with 3472 women that provided data for analysis. Most studies compared early SSC with standard hospital care for women with healthy full‐term babies. In eight studies women gave birth by cesarean, and in six studies the babies were healthy but born preterm at 35 weeks or more. More women who had SSC with their babies were still breastfeeding at one to four months after giving birth (14 studies, 887 women, moderate‐quality evidence). Mothers who had SSC breast fed their infants longer, too, on average over 60 days longer (six studies, 264 women, low‐quality evidence). Babies held in SSC were more likely to have breast fed successfully during their first breast feed (five studies, 575 women). Babies held in SSC had higher blood glucose levels (three studies, 144 women, low‐quality evidence), but similar temperature to babies with standard care (six studies, 558 women, low‐quality evidence). We had too few babies in our included studies and the quality of the evidence was too low for us to be very confident in the results for infants.

Women giving birth by cesarean may benefit from early SSC, with more women breastfeeding successfully and still breastfeeding at one to four months (fourteen studies, 887 women, moderate‐quality evidence), but there were not enough women studied for us to be confident in this result.

We found no clear benefit to immediate SSC rather than SSC after the baby had been washed and examined. Neither did we find any clear advantage of a longer duration of SSC (more than one hour) compared with less than one hour. Future trials with more women and infants may help us answer these questions with confidence.

SSC was defined in various ways and different scales and times were used to measure different outcomes. Women and staff knew they were being studied, and women in the standard care groups had varying levels of breastfeeding support. These differences lead to wide variation in the findings and a lower quality evidence. Many studies were small with less than 100 women participating.

What does this mean?

The evidence from this updated review supports using immediate or early SSC to promote breastfeeding. This is important because we know breastfeeding helps babies avoid illness and stay healthy. Women giving birth by cesarean may benefit from early SSC but we need more studies to confirm this. We still do not know whether early SSC for healthy infants helps them make the transition to the outside world more smoothly after birth, but future good quality studies may improve our understanding. Despite our concerns about the quality of the studies, and since we found no evidence of harm in any included studies, we conclude the evidence supports that early SSC should be normal practice for healthy newborns including those born by cesarean and babies born early at 35 weeks or more.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. 'Summary of findings Quality of the Evidence using GRADE.

| Skin‐to‐skin versus standard contact for healthy infants | ||||||

| Patient or population: mothers and their healthy newborn infants Setting: hospital settings in Chile, Guatemala, Japan, India, Italy, UK, Germany, Nepal, Poland, USA, Sweden, South Africa, Spain, Vietnam, Taiwan, and Canada Intervention: skin‐to‐skin contact Comparison: standard contact | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with standard contact for healthy infants | Risk with Skin‐to‐skin contact | |||||

| Breastfeeding 1 month to 4 months post birth | Study population | average RR 1.24 (1.07 to 1.43) | 887 (14 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1, 2, 11 | ||

| 541 per 1000 | 670 per 1000 (579 to 773) | |||||

| Duration of breastfeeding in days | The mean duration of breastfeeding in days in control groups was 88 days | The mean duration of breastfeeding in days in the intervention group was 63.73 days more (37.97 days more to 89.50 days more) | 264 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 4, 5 | This result is a sensitivity analysis excluding 1 trial that contributed all heterogeneity. | |

| SCRIP score first 6 hours post birth range (0 to 6) at each time point, trials recorded multiple time points** |

We could not calculate the control group mean due to different scales used in trials | The mean SCRIP score first 6 hours post birth in the intervention group was 1.24 standard deviations more (0.76 more to 1.72 more) | 81 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 12, 6 | A standardized mean difference (SMD) of 1.24 represents a large effect. | |

| Blood glucose mg/dL at 75 to 180 minutes post birth Thresholds for low glucose vary from 40 mg to 50 mg/dL |

The control group mean blood glucose at 75 to 180 minutes post birth was 49.8 mg/dL | The mean blood glucose mg/dL at 75 to 180 minutes post birth in the intervention group was 10.49 mg/dL more (8.39 more to 12.59 more) | 144 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3, 4 | The mean difference (MD) of 10.49 mg/dL is clinically significant. | |

| Infant axillary temperature (°C) 90 minutes to 2.5 hours post birth | The mean infant axillary temperature 90 minutes to 2.5 hours post birth was 36.62 °C | The mean infant axillary temperature 90 minutes to 2.5 hours post birth in the intervention group was 0.3 °C more (0.13 more to 0.47 more) | 558 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 4, 7 | The mean difference (MD) of 0.3 °C temperature is not clinically significant. | |

| Exclusive breastfeeding at hospital discharge to 1 month post birth | Study population | average RR 1.30 (1.12 to 1.49) | 711 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 8, 9 | ||

| 642 per 1000 | 835 per 1000 (719 to 957) | |||||

| Exclusive breastfeeding 6 weeks to 6 months post birth | Study population | average RR 1.50 (1.18 to 1.90) | 640 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 8, 10 | ||

| 519 per 1000 | 778 per 1000 (612 to 985) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ** SCRIP ‐ Stability of cardio‐respiratory system in preterms CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Most trials contributing data had unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment. Half had unclear sequence generation. We were unclear of the time point of data collection for 1 trial. No trial was blinded (‐1).

2 I² = 41% with random‐effects model. Not downgraded.

3 Estimate based on small sample size (‐1).

4 Most trials had unclear or high risk of bias for sequence generation and allocation concealment. No trial was blinded (‐1).

5 Estimate based on small sample size (‐1).

6 1 trial had unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment. No trial contributing data were blinded (‐1).

7 I² = 88% with random‐effects model due to 1 trial finding higher axillary temperature in the control group (‐1).

8 Several trials with unclear risk of bias for sequence generation and allocation concealment. No trial was blinded (‐1).

9 I² = 44% with random‐effects model (not downgraded).

10I² = 62% with random‐effects model (not downgraded).

112 very small trials had the most dramatic effects, and we could not rule out publication bias. The removal of these trials from the analysis does not change the overall effect or conclusions regarding the intervention. We have not downgraded for publication bias.

12Estimate based on small sample size. We also have some reservations regarding the trials' averaging SCRIP scores across repeated measures, as was done in both trials included in this analysis. Averaging will reduce the variability in infants' scores, reducing also the standard deviation. A smaller SD will increase the SMD, even if the actual difference between groups is not large. See http://bayesfactor.blogspot.co.uk/2016/01/averaging‐can‐produce‐misleading.html (‐1).

Background

Description of the condition

In humans, routine mother‐infant separation shortly after birth is unique to the 20th century. This practice diverges from evolutionary history, where neonatal survival depended on close and virtually continuous maternal‐infant skin‐to‐skin contact (SSC). In many industrialized societies separating the newborn from its mother soon after birth has become common practice. Therefore, for the purpose of this review, SSC has to be the experimental intervention. Ironically, and importantly, the experimental intervention in studies with all other mammals is to separate newborns from their mothers.

Description of the intervention

Immediate SSC is the placing of the naked baby prone on the mother's bare chest at birth and early SSC begins within the first day. In the evolutionary context, this would have been "immediate and continuous". In the context of this review, SSC is compared to all degrees of separation, from infants that are clothed but held by mother, to those in a central nursery. The clinical and nursing care does not change; SSC is regarded as the place where such care is provided. Further, although a dose‐response effect has not yet been documented in randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the general consensus is that minimally, SSC should continue until the end of the first successful breastfeeding in order to show an effect and to enhance early infant self‐regulation (Widstrom 2011). According to the Baby‐Friendly USA Initiative criteria, Step 4, all infants should be placed in SSC with their mothers immediately post birth for at least an hour.

How the intervention might work

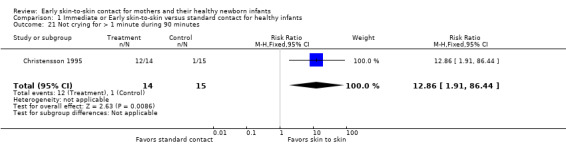

The rationale for SSC comes from animal studies in which some of the innate newborn behaviors that are necessary for survival are shown to be habitat or location dependent (Alberts 1994). In mammalian biology, maintenance of the maternal milieu following birth is required to elicit innate behaviors from the newborn and the mother that lead to successful breastfeeding, and thus survival. Further, maternal sensations are the triggers that ensure regulation of all aspects of neonatal physiology, including cardiorespiratory and digestive, hormonal and behavioral (Hofer 2006). Separation from this milieu is interpreted in rat studies as sudden and complete loss of such regulation (Hofer 2006), and results in immediate distress cries (Alberts 1994) and "protest‐despair" behavior. Human infants placed in a cot cry 10 times more than SSC infants (Christensson 1995). Their cry is similar to the vocalizations of separated rat pups using sound spectral analysis (Michelsson 1996). In rodent studies, the pups who had the least attentive contact from their mothers were the ones whose health and intelligence were compromised across the lifespan (Francis 1999; Liu 1997; Liu 2000; Meaney 2005; Plotsky 2005). Also in the report by Liu 2000, a cross‐fostering study provided evidence for a direct relationship between maternal behavior and normal hippocampal development in the offspring.

Healthy, full‐term infants employ a species‐specific set of innate newborn behaviors immediately following delivery when placed in SSC with the mother (Righard 1990; Varendi 1994; Varendi 1998; Widstrom 1987; Widstrom 1990). They localize the nipple by smell and have a heightened response to odor cues in the first few hours after birth (Porter 1999; Varendi 1994; Varendi 1997). More recently Widstrom 2011 described the sequence of nine innate behaviors as the birth cry, relaxation, awakening and opening the eyes, activity, a second resting phase, crawling towards the nipple, touching and licking the nipple, suckling at the breast and finally falling asleep. This 'sensitive period' predisposes or primes mothers and infants to develop a synchronous reciprocal interaction pattern, provided they are together and in intimate contact. Further evidence for a sensitive period is the activation of the olfactory cortex by colostrum, which is only present for the first day of life (Bartocci 2000). Infants who are allowed uninterrupted SSC immediately after birth and who self‐attach to the mother's nipple may continue to nurse more effectively. Effective nursing increases milk production and infant weight gain (De Carvalho 1983; Dewey 2003).

SSC is a powerful vagal stimulant, through sensory stimuli such as touch, warmth, and odor, which among other effects releases maternal oxytocin (Uvnas‐Moberg 1998; Winberg 2005). Oxytocin causes the skin temperature of the mother's breast to rise, providing warmth to the infant (Uvnas‐Moberg 1996). In a study of infrared thermography of the whole body during the first hour post birth, Christidis 2003 found that SSC was as effective as radiant warmers in preventing heat loss in healthy full‐term infants. When operating in a safe environment, oxytocin and direct SSC stimulation of vagal efferents are probably part of a broader neuro‐endocrine milieu (Porges 2007). A global physiological regulation of the autonomic nervous system is achieved, supporting growth and development, (homeorhesis). Under conditions perceived by the newborn to be threatening, (Graeff 1994; Porges 2007), stress mechanisms come into operation, with the focus on survival (homeostasis) rather than development (homeorhesis). The concept of allostasis takes a broader view of homeostasis and homeorhesis, being the relationship between psycho‐neurohormonal responses to stress and physical and psychological manifestations of health and illness across the lifespan (McEwen 1998; Shannon 2007). Allostatic mechanisms seek to restore autonomic systems to a healthy baseline. Repeated and chronic stress imposes an ‘allostatic load’, whereby the healthy baseline can no longer be maintained, and is therefore up‐regulated or adapted. The higher the allostatic load the greater the damage from stress, because allostatic load is cumulative.

Epigenetic changes probably mediate such change. In development, ‘predictive adaptive responses’ have been postulated to make early and permanent gene adaptations in many systems during sensitive periods (Gluckman 2005). In mammalian studies, maternal‐infant separation is regarded as a severe form of stress, with documented epigenetic changes in stress regulation systems (Arabadzisz 2010; Sabatini 2007). The original changes in hippocampal cortisol receptors first described in rats by Meaney 2005, are now also being documented in human adults (McGowan 2009). This concept is now more broadly described in DOHaD (Developmental Origins of Health and Disease), in which early developmental plasticity impacts “long‐term biological, mental, and behavioral strategies in response to local ecological and/or social conditions” (Hochberg 2011).

SSC also lowers maternal stress levels. Handlin 2009 found a dose‐response relationship between the amount of SSC and maternal plasma cortisol two days post birth. A longer duration of SSC was correlated with a lower median level of cortisol (r = ‐ 0.264, P = 0.044).

SSC induces oxytocin, which antagonizes the flight‐fight effect, decreasing maternal anxiety and increasing calmness and social responsiveness (Uvnas‐Moberg 2005). During the early hours after birth, oxytocin may also enhance parenting behaviors (Uvnas‐Moberg 1998; Winberg 2005). In the newborn period, stimuli such as SSC, suckling and vocalizations play a role in connecting oxytocin systems to dopamine pathways, neuroimaging shows that maternal neglect is characterized by failure to make such connections (Strathearn 2011). Consistent with this, SSC outcomes for mothers suggest improved bonding/attachment (Affonso 1989); other outcomes are an increased sense of mastery and self‐enhancement, resulting in increased confidence. Sense of mastery and confidence are relevant outcomes because they predict breastfeeding duration (Dennis 1999). Women with low breastfeeding confidence have three times the risk of early weaning (O'Campo 1992) and low confidence is also associated with perceived insufficient milk supply (Hill 1996).

Time to expulsion of the placenta was shorter (Marin 2010) (M = 409 + 245 sec.) in mothers of SSC infants than in control mothers (M = 475 + 277 sec., P = 0.05). With SSC on the mother's abdomen, the infant's knees and legs press into her abdomen in a massaging manner which would logically induce uterine contractions and thereby reduce risk of postpartum hemorrhage. Mothers who experience SSC have reduced bleeding (Dordevic 2008), and a more rapid delivery of the placenta than control mothers (Marin 2010).

Why it is important to do this review

In previous meta‐analyses with full‐term infants, early contact was associated with continued breastfeeding (Bernard‐Bonnin 1989; Inch 1989; Perez‐Escamilla 1994). Just altering hospital routines can increase breastfeeding levels in the developed world (Rogers 1997). The updated review on kangaroo mother care (KMC), (Conde‐Agudelo 2014) includes 18 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of 2751 low birthweight infants, all less than 2500 g at birth. KMC is defined as continuous or intermittent SSC with exclusive or nearly exclusive breastfeeding and early hospital discharge but KMC is seldom practiced in its entirety. Most included studies focus on SSC as the key intervention, evidenced by exclusive breastfeeding at discharge (and other breastfeeding outcomes) being reported as outcomes rather than the intervention. KMC was associated with reductions in mortality at hospital discharge and at latest follow‐up, nosocomial infection/sepsis at hospital discharge and severe infection/sepsis at latest follow‐up, hypothermia and hospital length of stay. The current WHO guidelines on newborn care “WHO recommendations on interventions to improve preterm birth outcomes” (WHO 2015) advise KMC for thermal care for preterm newborns.

In another meta‐analysis of 23 studies (13 case‐series, five RCT's, one cross‐over and four cohort), Mori 2010 evaluated temperature, heart rate and oxygen saturation outcomes in both low and normal birthweight infants up to 28 days old; showing small changes of no clinical significance. A Cochrane review focusing on the effect of SSC on procedural pain in all neonates (Johnston 2014), including 19 RCTs and 1594 infants; concluded that SSC provides effective pain relief as measured by physiological and behavioral responses. A meta‐analysis of nine RCTs and six observational studies, all from low‐ or middle‐income settings for infants born below 2000 g focusing on mortality using primarily the GRADE tool (Lawn 2010) reported that analysis of three RCTs commencing KMC in the first week of life showed a significant reduction in neonatal mortality. A commentary on this meta‐analysis points out a number of flaws (Sloan 2010), nevertheless the conclusions are in keeping with Conde‐Agudelo 2014.

The possibility exists that postnatal separation of human infants from their mothers is stressful (Anderson 1995). Delivery room and postpartum hospital routines may significantly disrupt early maternal‐infant interactions including breastfeeding (Anderson 2004a; Odent 2001; Winberg 1995). A concurrent widespread decline in breastfeeding is of major public health concern. Although more women are initiating breastfeeding, fewer are breastfeeding exclusively. Using data from the Infant Feeding Practices Study II conducted in the USA by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2005 to 2007, Grummer‐Strawn 2008 found that 83% of mothers initiated breastfeeding, but only 48% exclusively breast fed during their hospital stay. These innate behaviors can be disrupted by early postpartum hospital routines as shown experimentally by Widstrom 1990 and in descriptive studies by Gomez 1998; Jansson 1995 and Righard 1990. Gomez 1998 found that infants were eight times more likely to breast feed spontaneously if they spent more than 50 minutes in SSC with their mothers immediately after birth, and concluded that the dose of SSC might be an essential component regarding breastfeeding success. Bramson 2010 showed a clear dose‐response relationship between SSC in the first three hours post birth and exclusive breastfeeding at discharge in a large (N = 21,842 mothers) hospital‐based cohort study, (odds ratio (OR) for exclusive breastfeeding = 1.665 if in SSC for 16 to 30 minutes, and OR = 3.145 for more than 60 minutes of SSC).

The purpose of this review is to examine the available evidence of the effects of immediate and early SSC on breastfeeding exclusivity and duration and other outcomes in mothers and their healthy full‐term and late preterm newborn infants. Although our intent is to examine all clinically important outcomes, breastfeeding is the predominant outcome investigated so far in healthy newborns. Hence, our emphasis is on breastfeeding, although we also will examine maternal‐infant physiology and behavior. The focus of this review is on randomized controlled trials used to test the effects of immediate and early SSC. This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2003 and previously updated in 2007 and 2012.

Objectives

We assessed the effects of immediate or early skin‐to‐skin contact on healthy newborn infants and their mothers compared to standard contact (infants held swaddled or dressed in their mothers arms, placed in open cribs or under radiant warmers).

The three main outcome categories included:

establishment and maintenance of breastfeeding/lactation;

infant physiology ‐ thermoregulation, respiratory, cardiac, metabolic function, neuro behavior;

maternal‐infant bonding/attachment.

Planned comparisons

Planned comparisons included:

immediate or early skin‐to‐skin versus standard contact for healthy infants;

immediate or early skin‐to‐skin versus standard contact for healthy infants after cesarean birth;

skin‐to‐skin versus standard contact by time of initiation;

and skin‐to‐skin versus standard contact by dose (length of contact time).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in which the active encouragement of immediate or early skin‐to‐skin contact (SSC) between mothers and their healthy newborn infants was compared to usual hospital care. We did not include quasi‐randomized trials (e.g. where assignment to groups was alternate or by day of the week, or by other non‐random methods) or observational studies. We included cluster‐randomized trials if these were eligible. Cross‐over trials were not eligible for inclusion.

Trials reported in abstract form only were eligible for inclusion if there was sufficient information to assess the trial and include data. Abstract reports with insufficient information to assess the trial were left in Studies awaiting classification for one update cycle with a view that a full publication may clarify eligibility.

Because the focus of this review is on mothers and their healthy infants, potential effects of early SSC on father‐infant attachment and also the resistance of staff to this intervention are beyond the scope of this review. Maternal feelings about early SSC and satisfaction with the birth experience are important and relevant, but require more qualitative methods.

Types of participants

Mothers and their healthy full‐term or late preterm newborn infants (34 to less than 37 completed weeks' gestation) who had immediate or early SSC starting less than 24 hours after birth, and controls undergoing standard patterns of care. Infants eligible for our targeted trials weighed more than 2500 g, although some healthy late preterm infants weighed less and were not excluded. We excluded infants less than or equal to 1500 g because we expected that these infants did not complete at least 33 weeks' gestation. We excluded any infant admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit; eligible infants were healthy enough to stay with their mothers in the postpartum unit.

We included late preterm infants (from 34 weeks' gestation) in trials including infants of earlier gestation if we were able to separate data for the late preterm group.

We included women randomized to SSC after cesarean birth.

Types of interventions

Early SSC for term or late preterm infants can be divided into two subcategories.

(a) In 'Immediate, Birth or Very Early SSC', the infant is placed prone skin‐to‐skin on the mother's abdomen or chest less than 10 minutes post birth. The infant is suctioned while on the mother's abdomen or chest, if medically indicated, thoroughly dried and covered across the back with a pre‐warmed blanket. To prevent heat loss, the infant's head may be covered with a dry cap that is replaced when it becomes damp. Ideally, all other interventions are delayed until at least the end of the first hour post birth or the first successful breastfeeding. (b) 'Early SSC' can begin anytime between 10 minutes and 24 hours post birth. The baby is naked (with or without a diaper and cap) and is placed prone on the mother's bare chest between the breasts. The mother may wear a blouse or shirt that opens in front, or a hospital gown worn backwards, and the baby is placed inside the gown so that only the head is exposed. What the mother wears and how the baby is kept warm and what is placed across the baby's back may vary. What is most important is that the mother and baby are in direct ventral‐to‐ventral SSC and the infant is kept dry and warm.

Standard contact includes a number of diverse conditions: swaddled or dressed infants held in their mothers arms or with other family; infants placed in open cribs or under radiant warmers; or infants placed in a cot in the mother's room or elsewhere without holding. No infant in the comparison arm should have SSC.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Breastfeeding outcomes

Number of mothers breastfeeding (any breastfeeding) one month to four months post birth.

Duration of any breastfeeding in days.

Infant outcomes

Infant stabilization during the transition to extra‐uterine life (the first six hours post birth). Measured by the SCRIP score (e.g. stability of the cardio‐respiratory system – a composite score of heart rate, respiratory status and arterial hemoglobin oxygen saturation (SaO2), range of scores = 0‐6 (Bergman 2004).

Blood glucose levels during/after SSC compared to standard care in mg/dL 75 to 180 minutes post birth.

Infant thermoregulation = temperature changes during/after SSC compared to standard care (measured by axillary temperature in degree Celsius (°C) 90 minutes to 2.5 hours post birth.

Secondary outcomes

Breastfeeding outcomes (secondary)

Breastfeeding rates/exclusivity using the Labbok 1990; Hake‐Brooks 2008 Index of Breastfeeding Status (IBS) at hospital discharge up to one month post birth. The eight patterns of IBS are ranked as 1 for exclusive and 2 for almost exclusive breastfeeding, 3 for high, 4 for medium‐high, 5 for medium‐low and 6 for low partial breastfeeding. Token breastfeeding is ranked 7 and weaned is ranked 8.

Breastfeeding rates/exclusivity (using the Labbok 1990; Hake‐Brooks 2008 Index of Breastfeeding Status (IBS) six weeks to six months post birth.

Effective breastfeeding (Infant Breastfeeding Assessment Tool (IBFAT) (Matthews 1988; Matthews 1991) during the first feeding. The IBFAT evaluates four parameters of infant suckling competence: infant state of arousal or readiness to feed; rooting reflex; latch‐on; and suckling pattern. The infant can receive a score of 0 to 3 on each item for a maximum total score of 12 indicating adequate suckling competence.

Maternal breast temperature during and after SSC ‐ measured by an electronic thermometer positioned above the areola in a 12 o'clock position on the breast (Bystrova 2003).

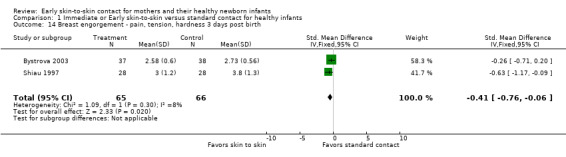

Breast engorgement ‐ measured by the self‐reported Six Point Breast Engorgement Scale (Hill 1994) or by the mother's perception of tension/hardness in her breasts) three days post birth.

Infant outcomes (secondary)

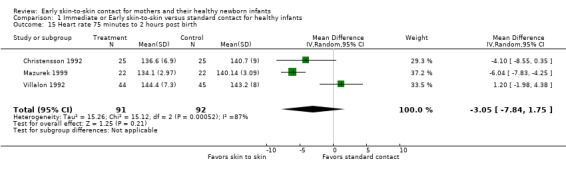

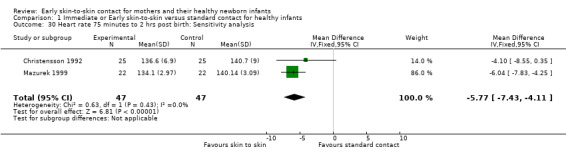

Infant heart rate during/after SSC compared to standard care 75 minutes to 2 hours post birth.

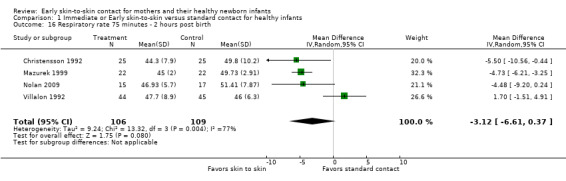

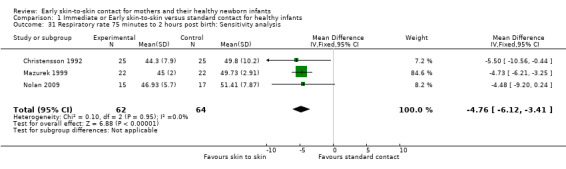

Respiratory status ‐ respiratory rate during/after SSC compared to standard care 75 minutes to 2 hours post birth.

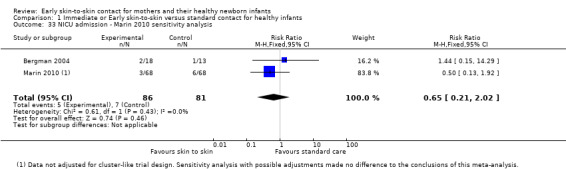

Neonatal intensive care unit admissions.

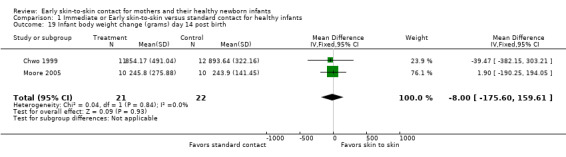

Infant weight changes/rate of growth in g/kg/day (daily weight change, change in weight over days of study) (Hill 2007).

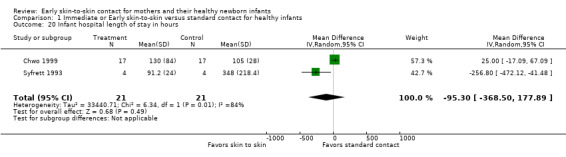

Length of hospital stay in hours.

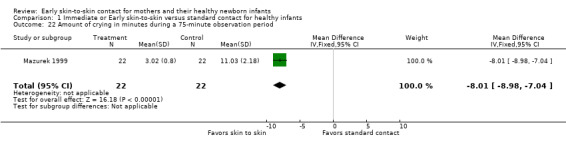

Amount of infant crying ‐ amount of crying in minutes during a 75‐ to 90‐minute observation period.

Maternal outcomes

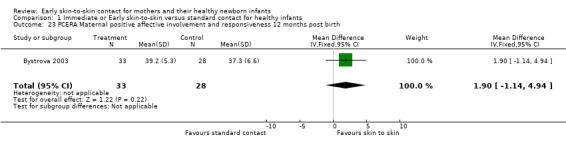

Maternal perceptions of bonding/connection to her infant at 12 months post birth using The Parent‐Child Early Relational Assessment (PCERA). The PCERA (Clark 1985; Clark 1999) has eight sub‐scales evaluating maternal and infant behavior and interaction.

Maternal pain four hours post cesarean birth ‐ Possible values for the pain scale were zero to 10 with 10 being the worst pain imaginable. Pain can interfere with maternal‐infant interaction.

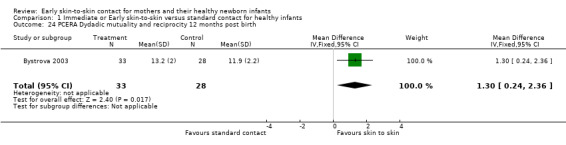

Maternal sensitivity to her infant’s cues using the PCERA at 12 months post birth.

Maternal anxiety using the state anxiety scale from the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (Spielberger 1970) eight hours to three days post birth. The state anxiety scale is a 20‐item instrument that measures how the individual feels in the present moment with a possible range of scores from 20 to 80 with higher scores indicating more anxiety.

Maternal parenting confidence measured at one month post birth by the Parenting Sense of Competence Scale, a 17‐item scale developed by Gibaud‐Wallston 1977 that assesses an individual’s perceptions of their skills, knowledge, and abilities for being a good parent, their level of comfort in the parenting role, and the importance they attribute to parenting.

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Electronic searches

We searched Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register by contacting their Information Specialist (17 December 2015).

The Register is a database containing over 22,000 reports of controlled trials in the field of pregnancy and childbirth. For full search methods used to populate Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register including the detailed search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL; the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service, please follow this link to the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth in the Cochrane Library and select the ‘Specialized Register ’ section from the options on the left side of the screen.

Briefly, Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register is maintained by their Information Specialist and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

monthly searches of CINAHL (EBSCO);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Search results are screened by two people and the full text of all relevant trial reports identified through the searching activities described above is reviewed. Based on the intervention described, each trial report is assigned a number that corresponds to a specific Pregnancy and Childbirth review topic (or topics), and is then added to the Register. The Information Specialist searches the Register for each review using this topic number rather than keywords. This results in a more specific search set which has been fully accounted for in the relevant review sections (Included studies; Excluded studies; Studies awaiting classification; Ongoing studies).

Searching other resources

The first three review authors have been active trialists in this area and have personal contact with many groups in this field including the International Network for Kangaroo Mother Care, based in Trieste (seeAppendix 1).

We searched the reference lists of retrieved studies.

We did not apply any language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For methods used in the previous version of this review, seeMoore 2012.

For this update, the following methods were used for assessing the 46 reports that were identified as a result of the updated search.

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted the third review author.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted the third review author. Data were entered into Review Manager software (RevMan 2014) and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we planned to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomization; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding was unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomized participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomization);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we planned to assess the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it was likely to impact on the findings. In future updates, we will explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Assessment of the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach

For this update we assessed the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach as outlined in the GRADE handbook in order to assess the quality of the body of evidence relating to the following outcomes for the main comparison of SSC versus standard contact for healthy infants.

Breastfeeding (any breastfeeding) one month to four months post birth

Duration of any breastfeeding in days

Exclusive breastfeeding at hospital discharge to one month post birth

Exclusive breastfeeding six weeks to six months post birth

Infant stabilization (SCRIP score first six hours post birth)

Blood glucose mg/dL at 75 to 180 minutes post birth

Infant axillary temperature 90 minutes to 2.5 hours post birth

We used the GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool to import data from Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan 2014) in order to create a ’Summary of findings’ table. A summary of the intervention effect and a measure of quality for each of the above outcomes was produced using the GRADE approach. The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence can be downgraded from 'high quality' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates or potential publication bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

We used the mean difference if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We used the standardized mean difference to combine trials that measured the same outcome but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomized trials

We included one cluster‐like randomized trial in this review with methods described in 'Other unit of analysis issues' below.

If in future updates we identify more eligible cluster‐randomized trials, we will include these trials in the analyses along with individually‐randomized trials. We will adjust their sample sizes or standard errors using the methods described in the Handbook [Section 16.3.4 or 16.3.6] using an estimate of the intra cluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomized trials and individually‐randomized trials, we plan to synthesize the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomization unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomization unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomization unit.

Cross‐over trials

Cross‐over trials were not eligible for inclusion in this review.

Other unit of analysis issues

For this update, we included a trial that randomized physicians rather than women Marin 2010. This trial was previously excluded from the review due to its cluster‐like design. We conducted sensitivity analyses to investigate the effects of cluster design (1.33 and 1.34). Assuming low dependence, we adjusted the sample size and event rate for the trial using a design effect of 2. Pagel 2011 offers a range of ICCs (0.01 to 0.09); a design effect of 2 uses an ICC of approximately 0.05. These adjustments did not substantially change the overall effect estimates or conclusions for our analyses 1.6 or 1.18. We therefore included unadjusted data in the meta‐analyses for these outcomes. We did not adjust for cluster design for the continuous variable 1.28 maternal state anxiety; however, the data contributed by this trial are in the same direction as the other trials in the analysis, with a more conservative estimate of the intervention.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. In future updates, if more eligible studies are included, we will explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, analyses were carried out, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomized to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomized minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if an I² was greater than 40% and either the Tau² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity. If we identified substantial heterogeneity (above 40%), we provided possible reasons for this in the text. We also explored heterogeneity by pre‐specified subgroup analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

In future updates, if there are 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis, we will investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry is suggested by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2014). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials were examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods were judged sufficiently similar.

If there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity was detected, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary, if an average treatment effect across trials was considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary was treated as the average of the range of possible treatment effects and we discuss the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect was not clinically meaningful, we planned not to combine trials. Where we used random‐effects analyses, the results were presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals and the estimates of Tau² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If we identified substantial heterogeneity, we considered whether an overall summary was meaningful, and if it was, we used random‐effects analysis to produce it. We investigated heterogeneity using subgroup analysis.

We carried out the following subgroup analyses to explore clinical groups even where there was no heterogeneity.

Initiation of skin‐to‐skin contact: immediate (< 10 minutes from birth) versus delayed (10 minutes or more after birth) in Comparison 3

Dose of skin‐to‐skin contact: high (more than 60 minutes in the first 24 hours) versus low (60 minutes or less) in Comparison 4

The following outcomes were used in subgroup analyses.

Breastfeeding outcomes

Number of mothers breastfeeding (any breastfeeding) one month to four months post birth

Duration of breastfeeding

Infant outcomes

Infant stabilization during the transition to extra‐uterine life Measured by the SCRIP score (e.g. stability of the cardio‐respiratory system – a composite score of heart rate, respiratory status and arterial hemoglobin oxygen saturation (SaO2), range of scores = 0‐6 (Fischer 1998)

Blood glucose levels during/after SSC compared to standard care

Infant thermoregulation = temperature changes during/after SSC compared to standard care (measured by axillary temperature)

We assessed subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan (RevMan 2014). We reported the results of subgroup analyses quoting the Chi² statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to carry out sensitivity analysis to look at whether the methodological quality of studies had an impact on results; however, none of the included studies met all criteria for low risk of bias and we therefore did not carry out this analysis in this version of the review. In view of the mixed methodological quality of trials, we advise caution in the interpretation of results.

For our two primary outcomes there were high levels of heterogeneity with much of the variation due to a single study. We therefore carried out sensitivity analysis excluding this study (Sosa 1976a) to examine the impact on results (1.29 and 1.30). For infant physiological outcomes, we also carried out sensitivity analysis removing Villalon 1992 to explore high levels of heterogeneity (1.31 and 1.32). Finally, we tested the impact of adjustments for cluster design for Marin 2010 as described above (1.33 and 1.34).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

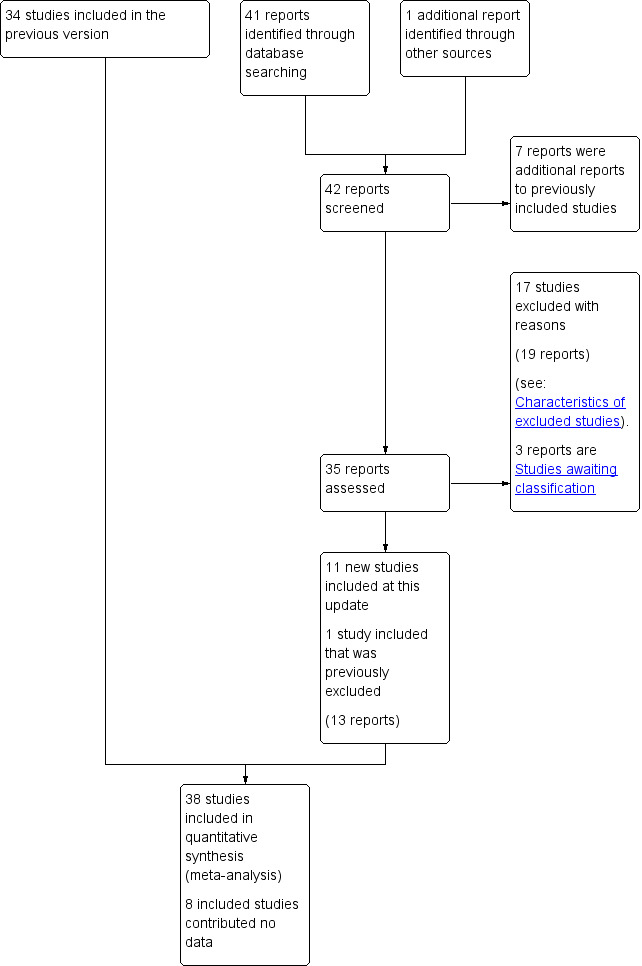

See: Figure 1.

1.

1 Study flow diagram.

For this 2016 update we assessed 41 new reports from the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group search. We located an additional trial report through our own searches (Luong 2015). From these 42 new reports we included 11 new studies. We also included one study previously excluded, so that this review includes 12 new studies (13 reports). We excluded 17 studies (19 reports). Three reports describe trials in abstract form only; we were unable to fully assess these for inclusion due to insufficient information (see Studies awaiting classification). Seven reports were additional reports for previously included studies (Bystrova 2003; Khadivzadeh 2009).

New studies found at this update

Twelve randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been added to the review for 2016. The results from an additional report involving the data set from Bystrova 2003, and several from Khadivzadeh 2009 have been added to this update.

Included studies

Forty‐six studies with 3850 mother‐infant dyads met the inclusion criteria. Eight of these trials contributed no data to the review (Curry 1982; Fardig 1980; Ferber 2004; Hales 1977; Huang 2006; Kastner 2005; McClellan 1980; Svejda 1980), leaving 38 studies with 3472 infants and women for analyses. A large number of outcomes (28) have been reported in the analysis, but only 20 of these included multiple trials for pooled analysis. For many of the other outcomes a small number of studies (two or three) contributed data.

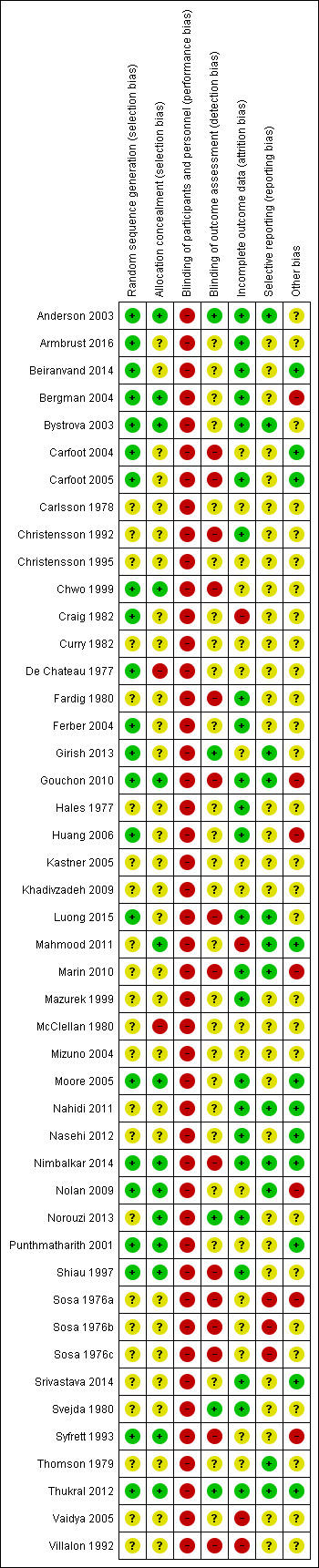

None of the 46 studies met all of the methodological quality criteria (seeFigure 2 and Figure 3). The total sample sizes in the studies ranged from eight to 350 mother‐infant pairs, with only 12 trials each recruiting over 100 women and infant pairs. The studies represented very diverse populations in Canada, Chile, Germany, Guatemala, India, Iran, Israel, Italy, Japan, Nepal, Pakistan, Poland, Russia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Taiwan, Thailand, the UK, USA and Vietnam. One paper reported results for studies carried out in two different sites in Guatemala, and we have treated these as three different studies in the data analysis (Sosa 1976a; Sosa 1976b; Sosa 1976c).

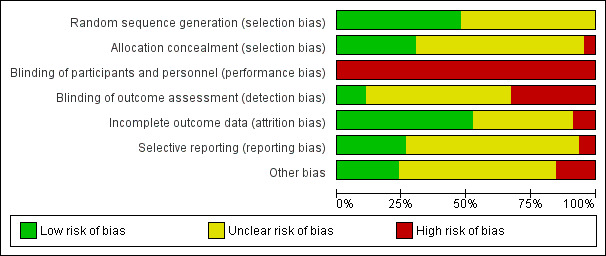

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

For this update, we have included unpublished data or clarification from authors for the following trials (Armbrust 2016; Girish 2013; Luong 2015; Nimbalkar 2014).

Population

Most trials recruited singleton pregnancies; though this was not always stated, it was inferred through outcome data and reference to mother‐infant dyad. Luong 2015 and Mahmood 2011 specifically excluded multiple births. Several trials recruited only primiparous women (Carlsson 1978; Craig 1982; Curry 1982; De Chateau 1977; Hales 1977; Khadivzadeh 2009; Nahidi 2011, all three Sosa trials, Svejda 1980; Thomson 1979). In contrast, all women in McClellan 1980 were multiparous.

All but six of the 46 studies included only healthy full‐term infants. Five studies (Anderson 2003; Bergman 2004; Chwo 1999; Luong 2015; Syfrett 1993) were carried out with healthy late preterm infants who were assigned to the normal newborn nursery or neonatal unit. Nimbalkar 2014 included both term and late preterm infants, while for Luong 2015 we have included a subset of late preterm infants with low birthweight (unpublished data). Seven studies (Armbrust 2016; Beiranvand 2014; Gouchon 2010; McClellan 1980; Nasehi 2012; Nolan 2009; Norouzi 2013) were conducted with healthy mother‐infant dyads after a cesarean birth. One study (Huang 2006) was conducted with hypothermic, but otherwise healthy newborns post‐cesarean birth.

Interventions

The characteristics of the intervention varied greatly between studies. Duration of skin‐to‐skin (SSC) ranged from approximately 15 minutes (De Chateau 1977; Svejda 1980; Thomson 1979; Vaidya 2005) to a mean of 37 hours of continuous SSC (Syfrett 1993); in Syfrett 1993 all dyads received 24 minutes of SSC before randomization. All dyads in Bergman 2004 also received a brief period of SSC immediately after birth. In contrast, all infants in Bystrova 2003 were immediately warmed, dried, washed and weighed before receiving control or intervention protocol. Apart from different protocols of SSC, intervention arms had different rates of compliance with the intervention (though not all trials reported this). Armbrust 2016 reported (by email) that two infants randomized to SSC did not receive this due to their need to see a neonatologist. Anderson 2003 reported that SSC mothers gave SSC 22% of the time and held their wrapped infants for 11.6% of the observation period.

For subgroup analysis we have compared trials that initiated SSC < 10 minutes post birth with trials starting SSC > 10 minutes from birth. Eighteen of 38 trials contributing data to the review began SSC immediately after birth (please see Table 2). Delayed contact trials had considerable differences in timing. Many infants went to their mothers after an initial assessment that was longer than 10 minutes; exact timing was not always described. SSC dyads in the study by Shiau 1997 could not begin until four hours post birth because of hospital policy. SSC did not begin until a mean of 21.3 hours post birth in the study by Chwo 1999 of late preterm infants 34 to 36 weeks' gestational age. In 31 of the 46 studies the infants were given the opportunity to suckle during SSC but only nine studies (Beiranvand 2014; Carfoot 2004; Carfoot 2005; Girish 2013; Gouchon 2010; Khadivzadeh 2009; Mahmood 2011; Moore 2005; Srivastava 2014) documented the success of the first breastfeeding using a validated instrument, the Infant Breastfeeding Assessment Tool. The amount of assistance the mothers received with breastfeeding during SSC was unclear in many of the research reports.

1. SSC Timing and Dosage.

| Trial | Immediate (< 10 min) or Delayed SSC (> 10 min)1 |

Low dose (< 60 min) or High dose (> 60 min) |

| Anderson 2003 | I | H |

| Armbrust 2016 | I | H |

| Beiranvand 2014 | D | L |

| Bergman 2004 | I | H |

| Bystrova 2003 | D | H |

| Carfoot 2004 | I | H |

| Carfoot 2005 | I | L |

| Carlsson 1978 | I | L |

| Christensson 1992 | I | H |

| Christensson 1995 | I | H |

| Chwo 1999 | D | H |

| Craig 1982 | D | L |

| De Chateau 1977 | D | L |

| Girish 2013 | I | L |

| Gouchon 2010 | D | H |

| Khadivzadeh 2009 | I | H |

| Luong 2015 | I | H |

| Mahmood 2011 | I | L |

| Marin 2010 | I | H |

| Mazurek 1999 | I | H |

| Mizuno 2004 | I | H |

| Moore 2005 | I | H |

| Nahidi 2011 | I | Not stated |

| Nasehi 2012 | D | H |

| Nimbalkar 2014 | D | H |

| Nolan 2009 | D | L |

| Norouzi 2013 | not stated | L |

| Punthmatharith 2001 | D | L |

| Shiau 1997 | D | H |

| Sosa 1976a | D | L |

| Sosa 1976b | D | L |

| Sosa 1976c | D | L |

| Srivastava 2014 | not stated | H |

| Syfrett 1993 | D | H |

| Thomson 1979 | D | H |

| Thukral 2012 | D | L |

| Vaidya 2005 | D | L |

| Villalon 1992 | I | H |

1. I = immediate; D = delayed; L = low; H = high.

We also compared trials with low (60 minutes or less SSC) or high dose (greater than 60 minutes SSC). Twenty‐three of 38 trials contributing data to the review offered infants 60 minutes or less of SSC (please see Table 2).

Control groups

Substantial differences were found between studies in the amount of separation that occurred in the control group. In eight studies (Chwo 1999; Hales 1977; Huang 2006; Mizuno 2004; Shiau 1997; Sosa 1976a; Sosa 1976b; Sosa 1976c), infants were removed from their mothers immediately post birth and reunited 12 to 24 hours later. In Luong 2015 control infants were separated from their mothers until their discharge from the neonatal unit. In five studies (Carlsson 1978; Craig 1982; Gouchon 2010; Svejda 1980; Thomson 1979), the mothers held their swaddled infants for about five minutes soon after birth and then were separated from their infants. Control mothers held their swaddled infants six times for 60 minutes in Chwo 1999, 20 minutes in Kastner 2005, 60 minutes in Moore 2005 and for two hours in Marin 2010 and Punthmatharith 2001. The swaddled control infants in Khadivzadeh 2009 were reunited with their mothers after the episiotomy repair. Control infants in Nolan 2009 were separated from their mothers for a mean of 21 minutes, for 30 to 60 minutes in Girish 2013 and in Gouchon 2010 for a mean of 51 minutes and in Nasehi 2012, 120 minutes post‐cesarean birth. There were four groups in the study by Bystrova 2003; an SSC group, a mother's arms group where the infants were held swaddled or dressed, a nursery group and a reunion group where the infants were taken to the nursery immediately post birth for 120 minutes but reunited with their mothers for rooming‐in on the postpartum unit. In Anderson 2003 control mothers held their wrapped infants 13.9% of the time (M = 6.67 hours). Many of the trials do not report when the control mothers were reunited with their infants or the length of initial contact.

The control group in several trials received multiple interventions, including those that may interfere with breastfeeding (such as vitamin K injections and physical assessment) (Armbrust 2016; Girish 2013; Khadivzadeh 2009; Luong 2015).

Details of all included studies are set out in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

Excluded studies

Sixty‐six studies were assessed and excluded from the review. The primary reason for exclusion was that the investigators did not state that the infants in the intervention group received immediate or early SSC with their mothers. When the information in the research report was unclear, where possible we contacted the investigators to determine whether the early contact was indeed skin‐to‐skin (see the table of Characteristics of excluded studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

Overall, no trial met all criteria for low risk of bias, due to lack of blinding in all trials. Most included studies had unclear reporting for one or more domains. Many studies also had high risk of bias for incomplete reporting of outcome data, attrition or other sources of bias, including multiple co‐interventions or baseline differences in important potential or known covariates such as socio‐economic status. Trials were best at reporting randomization methods, while we consider lack of blinding of outcomes assessors the highest risk of bias across included studies.

Allocation

Sequence generation

No trial was at high risk of bias due to quasi‐random methods of sequence generation. In 22 of the 46 included studies trialists described clear and appropriate methods for generating the randomization sequence for an assessment of low risk of bias. For 24 studies we found insufficient information to determine if the method of sequence generation was robust before allocation of the participants to groups occurred; one of these studies used a random numbers table, but there was some confusion as to whether women could have been re‐assigned (McClellan 1980).

Allocation concealment

Two studies (De Chateau 1977; McClellan 1980), we judged to be of high risk of bias for allocation concealment because the researchers used an open table of random numbers. Fourteen of 46 included studies were of low risk of bias for allocation concealment due to use of sequential, sealed envelopes or computer‐numbered programs (the minimization method) (Anderson 2003; Bergman 2004; Bystrova 2003; Chwo 1999; Gouchon 2010; Mahmood 2011; Moore 2005; Nimbalkar 2014; Nolan 2009; Norouzi 2013; Punthmatharith 2001; Shiau 1997; Syfrett 1993, Thukral 2012). Randomization by minimization, clearly described by Conlon 1990 and Zeller 1997, is a method of sequential assignment into groups that reduces the amount of bias by controlling for as many known extraneous factors as possible. It produces groups that are comparable in size and distribution of potentially confounding covariates (Pocock 1975). The remaining included trials had insufficient information on allocation concealment or incomplete description of methods used ‐ such as whether envelopes were sealed or sequentially numbered or opened consecutively. Some of these trials only reported that women were randomly assigned to groups.

Blinding

Performance bias

No trial was blinded for performance bias. Because the intervention clearly differed from the control in all trials, we have assessed all trials as of high risk of bias. We have downgraded all evidence assessed with GRADE for lack of adequate blinding of the intervention from staff and women in trials.

Most women and staff were aware of the intervention, and this awareness may have altered women's responses to questions and influenced the content and quality of care from staff. That stated, many included trials reported different scenarios where blinding of staff or women was attempted. For example, Ferber 2004 stated that the nursery staff were blind to patient group assignment. Surprisingly, several trials attempted to blind for patient performance bias. In seven older studies (Carlsson 1978; Craig 1982; Curry 1982; Ferber 2004; Kastner 2005; Svejda 1980; Thomson 1979), it was reported that the women randomized were not aware that they were receiving an experimental treatment and/or they were not informed about the true purpose of the study. Adequate control for patient performance is problematic in the more recent studies because of Institutional Review Board requirements that investigators disclose the true purpose of the study or the experimental conditions, or both.

In the majority of studies, control for provider performance bias was difficult to determine, and certainly the risk of bias of an unblinded intervention may differ according to the outcome in question ‐ whether physiological or self‐reported. However, due to the very different protocols for intervention and control arms, we have assessed all trials as of high risk of performance bias.

Detection bias

Blinding outcome assessors to treatment group is extremely difficult for this type of intervention, and we found it hard to judge the impact of lack of blinding on particular outcomes. We assessed five trials that reported blinding of outcome assessment as of low risk of bias (Anderson 2003; Girish 2013; Norouzi 2013; Svejda 1980; Thukral 2012). In 15 trials researchers who were aware of allocation also collected outcome data; these trials were assessed as high risk of detection bias. For remaining included trials we assessed the impact of lack of blinding for detection bias as unclear, due to insufficient information or due our uncertainty regarding the impact of limited blinding of various clinical staff, data analysts or statisticians.

Incomplete outcome data

Four trials were assessed as at high risk of attrition bias due to missing data at specific time points or unclear denominators (Craig 1982; Mahmood 2011; Vaidya 2005; Villalon 1992). Several trials (Anderson 2003; Bergman 2004; Bystrova 2003; Carfoot 2005; Gouchon 2010; Moore 2005) utilized the Consort Guidelines (Moher 2001; Moher 2010) to document the flow of participants through their clinical trial; these and others with clear reporting on all participants were assessed as of low risk of bias. We assessed the remaining trials as unclear if denominators were unclear or not reported, or if we were unsure of the impact of incomplete or unclear follow‐up at specific time points, for example.

Selective reporting

Selective reporting bias was evaluated by reviewing the outcomes listed in the Methods section of the individual trials and then examining whether data for these outcomes was reported in the Results section. We did not search for protocols but made judgements based on published reports only.

Twelve trials were assessed as at low risk of bias for selective reporting because all outcomes mentioned in the published papers were reported. We were unclear about the selective reporting of most remaining trials. There are several reasons for a judgment of unclear: we had questions about data and contacted authors; a trial reported an outcome for one treatment group and not the other; a trial reported a result in terms of statistical significance or percentages in the text without events and totals; we noted incomplete reporting of data collected at multiple time points, or finally, the trial failed to report an outcome mentioned in the methods text. We assessed the three Sosa trials as of high risk of bias due to incomplete reporting of data collected at different time points and because there were no standard deviation (SDs) reported for the mean of our primary outcome of breastfeeding duration.

Other potential sources of bias

A judgement unclear risk of 'other bias' has to do with different types of interventions and control groups (affecting generalizability of results), possible differences in important baseline characteristics between arms, and discrepancies in the published reports. The following trials were assessed as unclear for stated reasons. In several trials, women in the control arms received help with breastfeeding and lactation support (Anderson 2003; Chwo 1999; Girish 2013; Gouchon 2010; Moore 2005). Included studies Armbrust 2016, Nolan 2009, and Syfrett 1993 all had multiple co‐interventions with the potential to impact on outcomes. We were unsure of the impact of possible differences in baseline characteristics in Girish 2013. Other factors noted were: whether the primary outcome of the trial targeted something different from the focus of this review and whether or not the women had analgesia.

For several trials there were factors that we felt deserved a judgement of high risk of 'other bias'. The infants in both arms of Gouchon 2010 were bathed before returning to their mother, which would impact on the temperature outcomes. For another trial, the results represent an interim analysis and this was rated as high risk of bias; Bergman 2004 had difficulty recruiting women and stopped the trial after interim analyses favored the intervention. Infants receiving SSC in Huang 2006 weighed significantly more than control infants. In the Marin 2010 trial, SCC infants weighed less than controls, and the trial report does not offer any details of adjustments made for cluster‐design (randomization of pediatricians rather than women). Infants receiving the intervention in the Nolan 2009 trial had significantly higher cortisol and weighed more than control infants; further, this trial had several co‐interventions. More women in the control group of Sosa 1976a had poor socio‐economic status as measured with a socio‐economic index score; the authors used this to explain the difference in breastfeeding status favoring the control group. Syfrett 1993 had a very small sample size that was recruited at times convenient to the investigators and multiple co‐interventions.

An overall summary of risk of bias for all studies is set out in Figure 2 and 'Risk of bias' findings for individual studies are set out in Figure 3.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

All the studies reviewed were randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Where multiple studies contributed outcome data, there was often considerable statistical heterogeneity noted. Where we identified statistical heterogeneity (an I² greater than 40%), we have drawn attention to this in the text and provided explanation. We urge caution in the interpretation of these results which show the average treatment effect. Different scales and the definition of review outcomes between trials and differences in the intervention between trials most likely contribute to the heterogeneity found in several analyses.

Comparison 1: Immediate or early skin‐to‐skin contact versus standard care for healthy infants

Primary outcomes ‐ breastfeeding rates/duration

Immediate or early SSC resulted in better overall performance on several measures of breastfeeding status, although there was heterogeneity between studies. Almost all studies except Shiau 1997 and Chwo 1999 began SSC during the first hour post birth. We found few studies and limited data for many of the review outcomes.

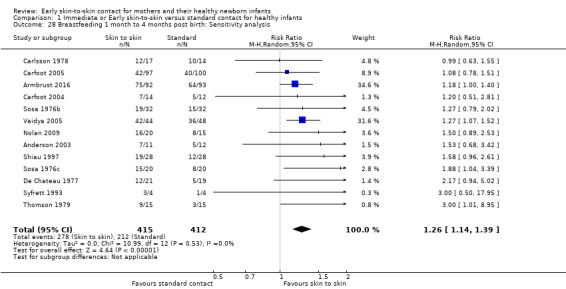

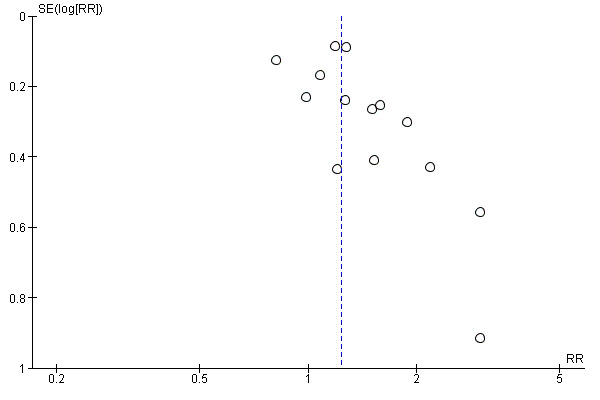

More SSC dyads were still breastfeeding one to four months post birth (average risk ratio (RR) 1.24, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.07 to 1.43; participants = 887; studies = 14; moderate‐quality evidence). Overall, there were differences in the size of the treatment effect between studies leading to moderate heterogeneity for this outcome (Tau² = 0.02, P = 0.05, I² = 41%) (Analysis 1.1). Much of the heterogeneity was due to a single study (Sosa 1976a) where the study author speculated that variation in treatment effect was due to the particular population of women with lower socio‐economic status attending one study hospital. We carried out a sensitivity analysis removing this study, which reduced statistical heterogeneity (Tau² = 0.00, P = 0.53, I² = 0%) and had little impact on the overall treatment effect; results favoring the SCC group remained (RR 1.26, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.39; participants = 827; studies = 13) (Analysis 1.28). As sufficient studies contributed data to this outcome, we generated a funnel plot to explore whether there was any obvious small‐study effect. Visual examination of the forest and funnel plots suggested that there was a greater treatment effect associated with smaller studies and this may indicate possible publication bias (Figure 4).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Immediate or Early skin‐to‐skin versus standard contact for healthy infants, Outcome 1 Breastfeeding 1 month to 4 months post birth.

1.28. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Immediate or Early skin‐to‐skin versus standard contact for healthy infants, Outcome 28 Breastfeeding 1 month to 4 months post birth: Sensitivity analysis.

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Skin‐to‐skin versus standard contact for healthy infants, outcome: 1.1 Breastfeeding 1 month to 4 months post birth.