Abstract

Background

There is extensive evidence of important health risks for infants and mothers related to not breastfeeding. In 2003, the World Health Organization recommended that infants be breastfed exclusively until six months of age, with breastfeeding continuing as an important part of the infant’s diet until at least two years of age. However, current breastfeeding rates in many countries do not reflect this recommendation.

Objectives

To describe forms of breastfeeding support which have been evaluated in controlled studies, the timing of the interventions and the settings in which they have been used.

To examine the effectiveness of different modes of offering similar supportive interventions (for example, whether the support offered was proactive or reactive, face‐to‐face or over the telephone), and whether interventions containing both antenatal and postnatal elements were more effective than those taking place in the postnatal period alone.

To examine the effectiveness of different care providers and (where information was available) training.

To explore the interaction between background breastfeeding rates and effectiveness of support.

Search methods

We searched Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth's Trials Register (29 February 2016) and reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials comparing extra support for healthy breastfeeding mothers of healthy term babies with usual maternity care.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trials for inclusion and risk of bias, extracted data and checked them for accuracy. The quality of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach.

Main results

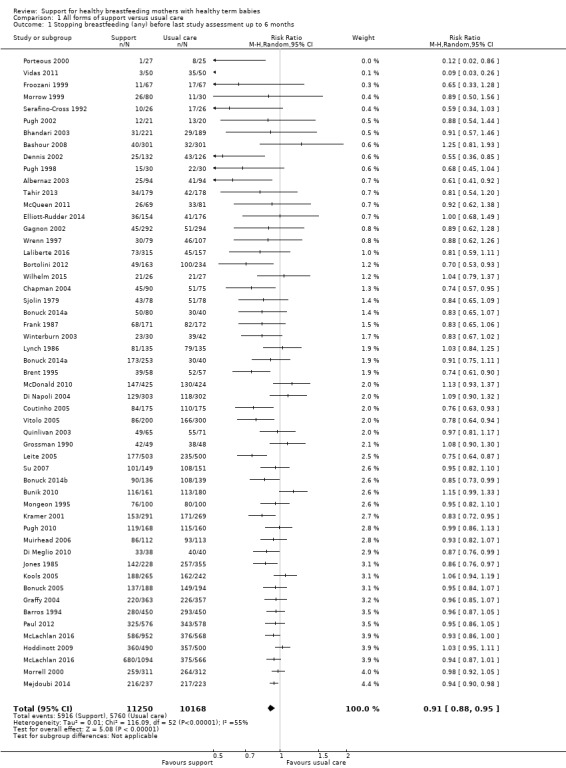

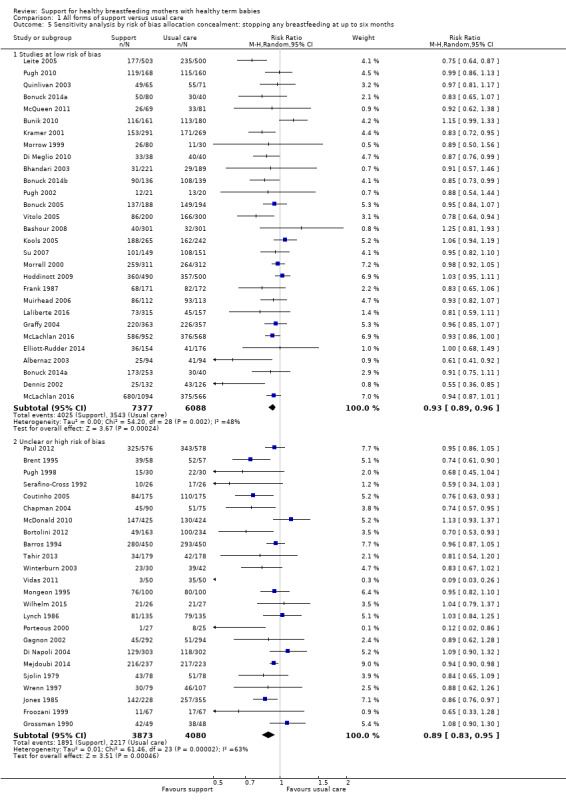

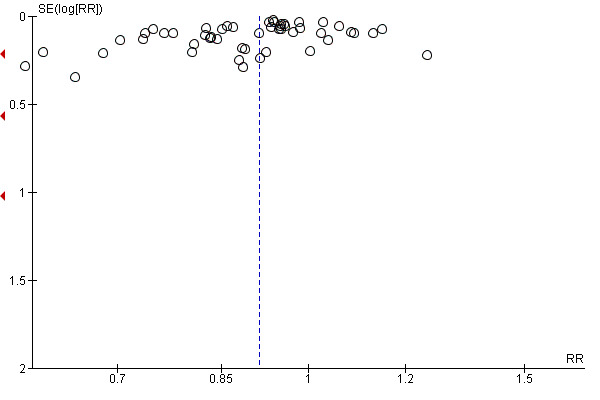

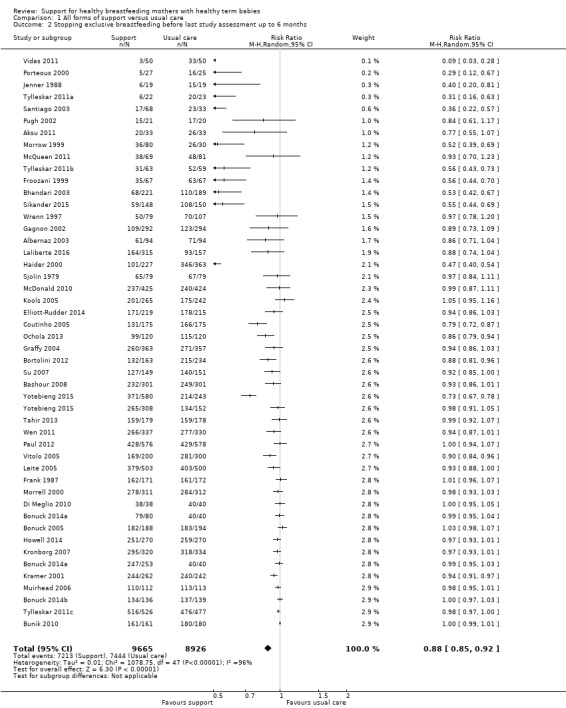

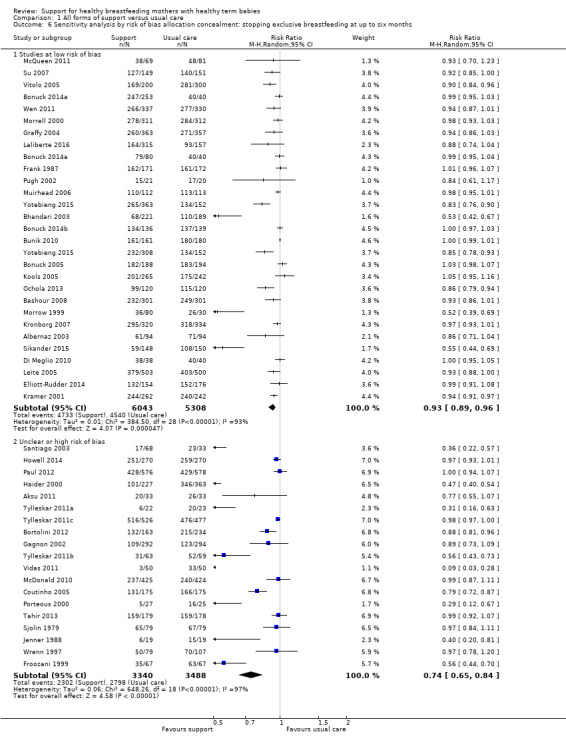

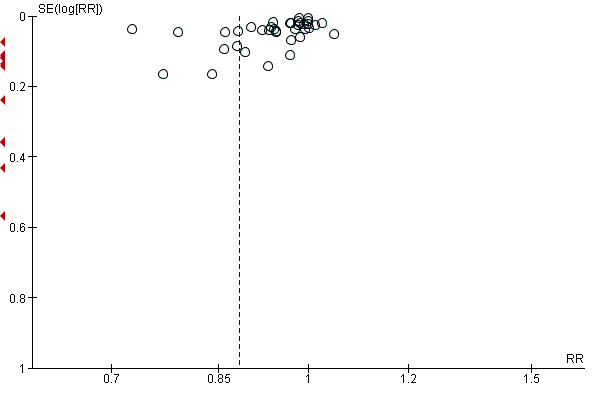

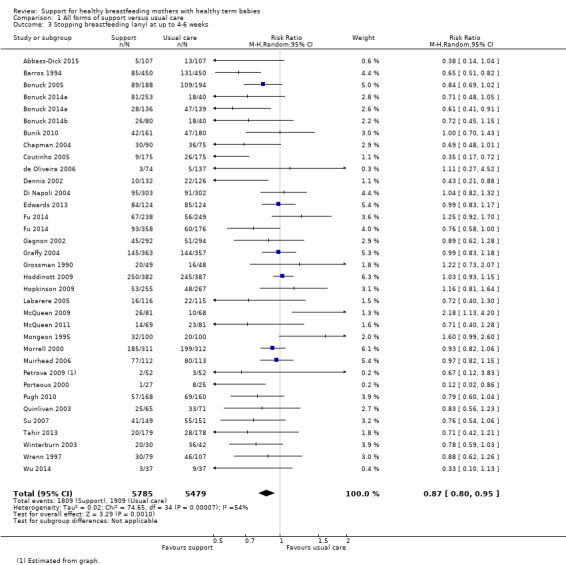

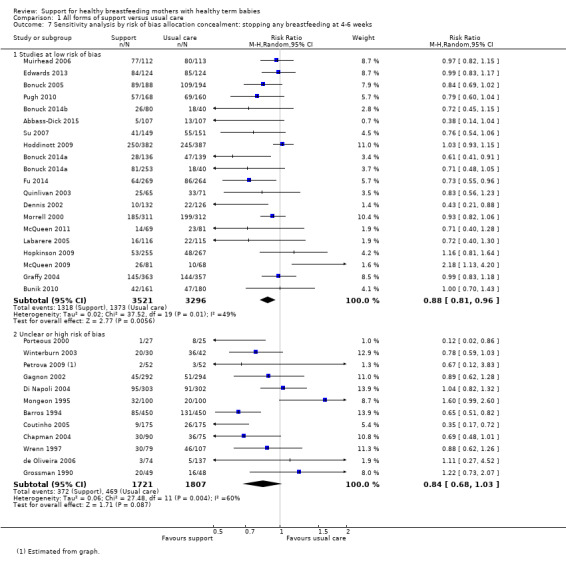

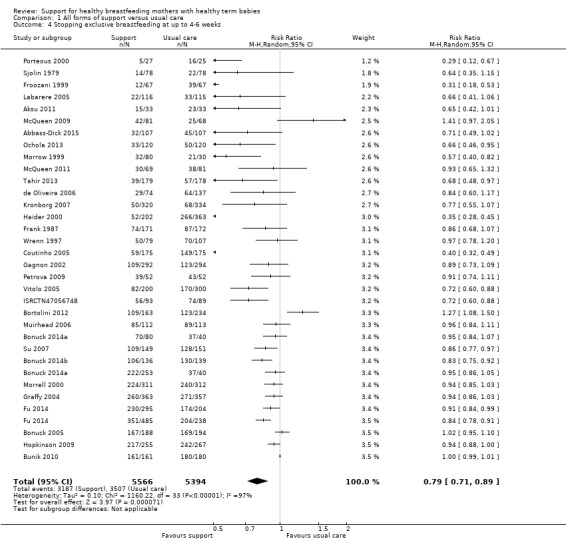

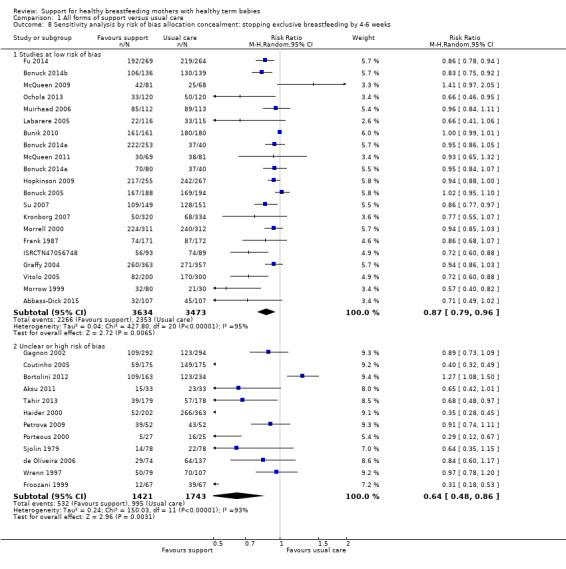

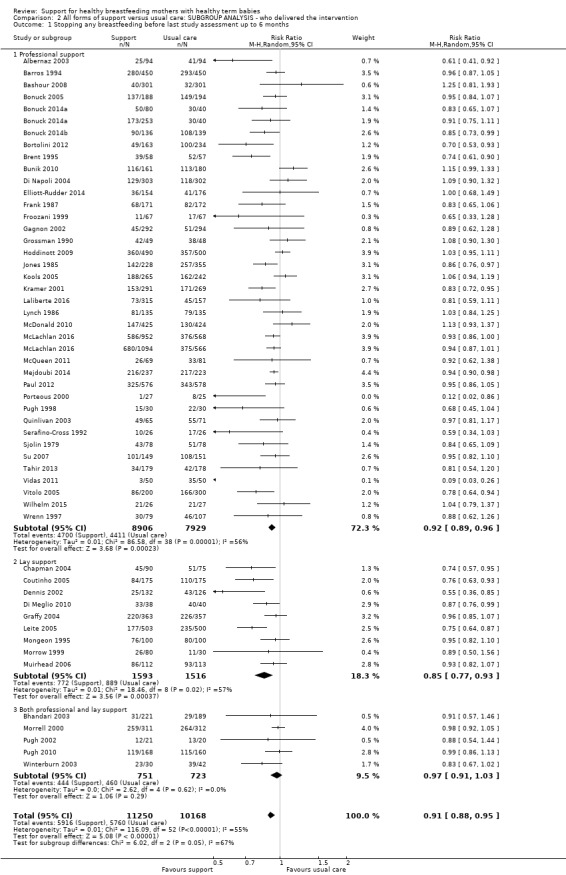

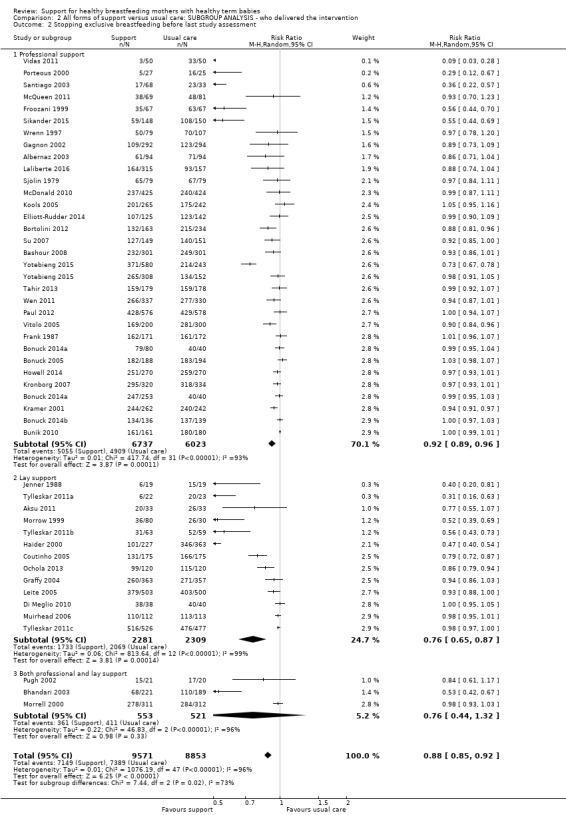

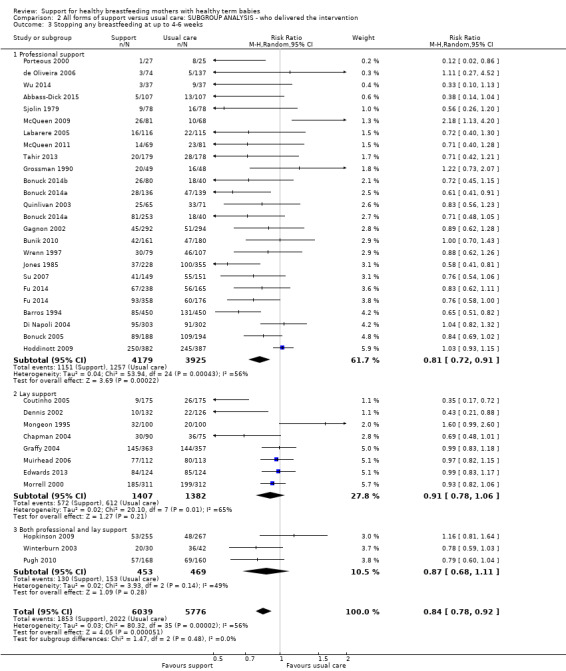

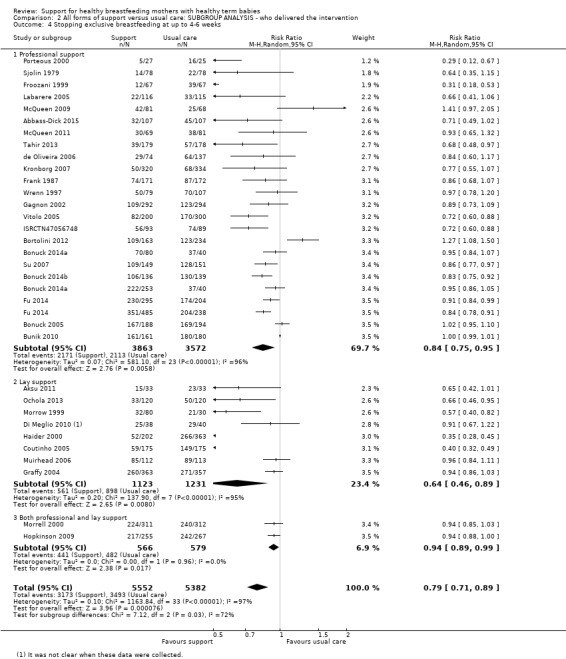

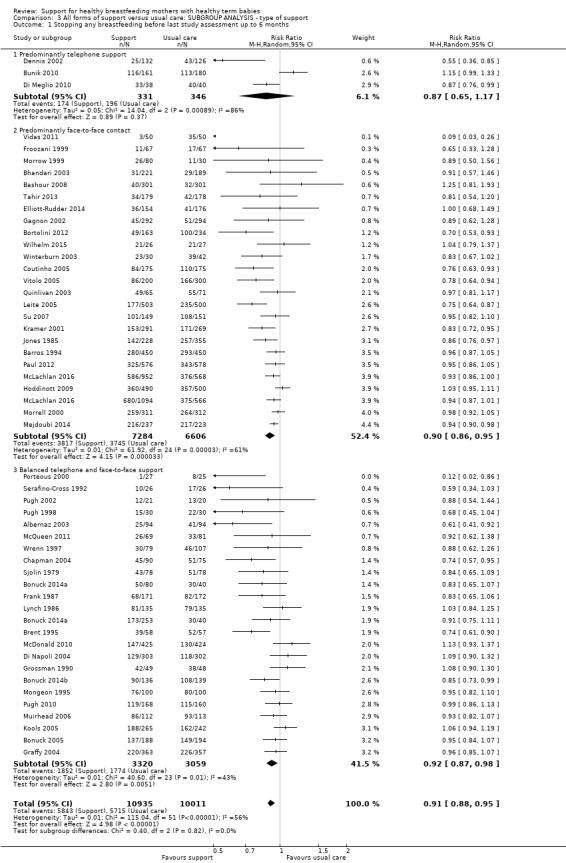

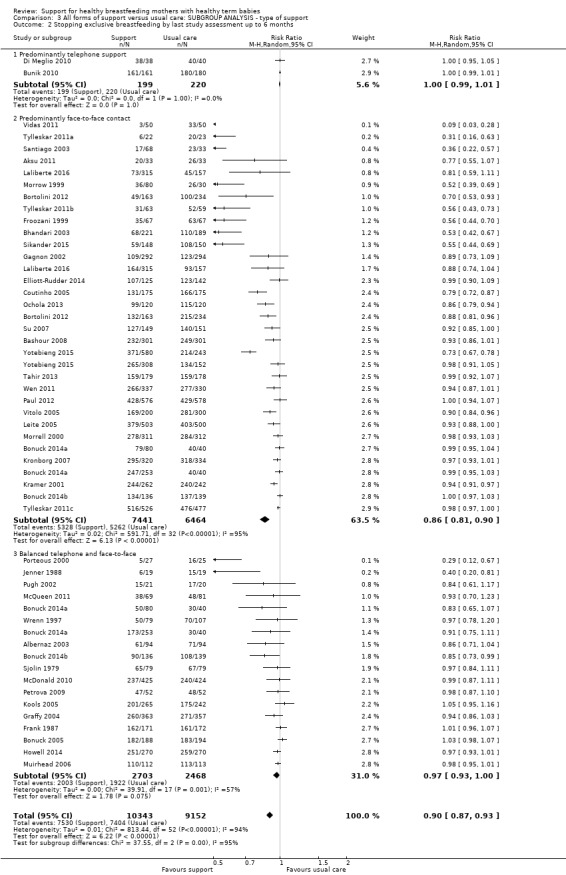

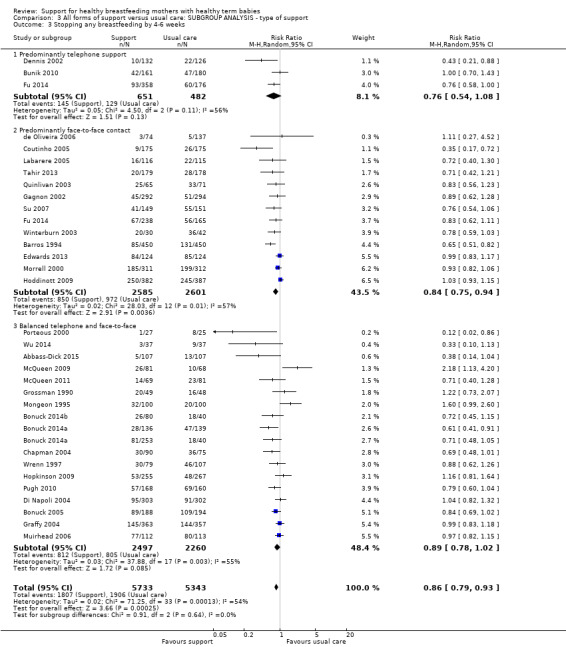

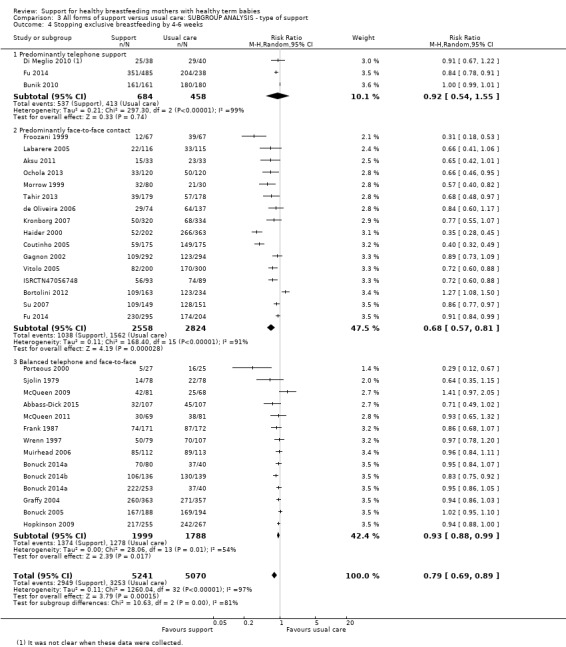

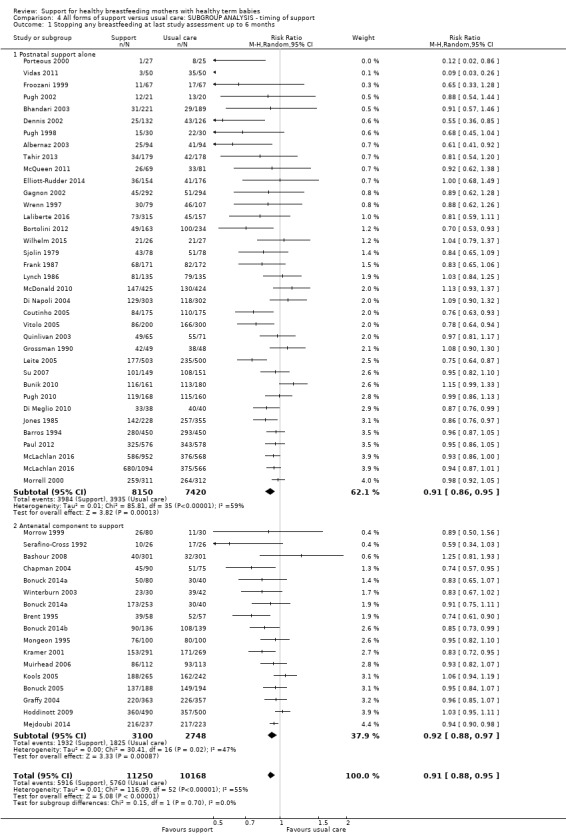

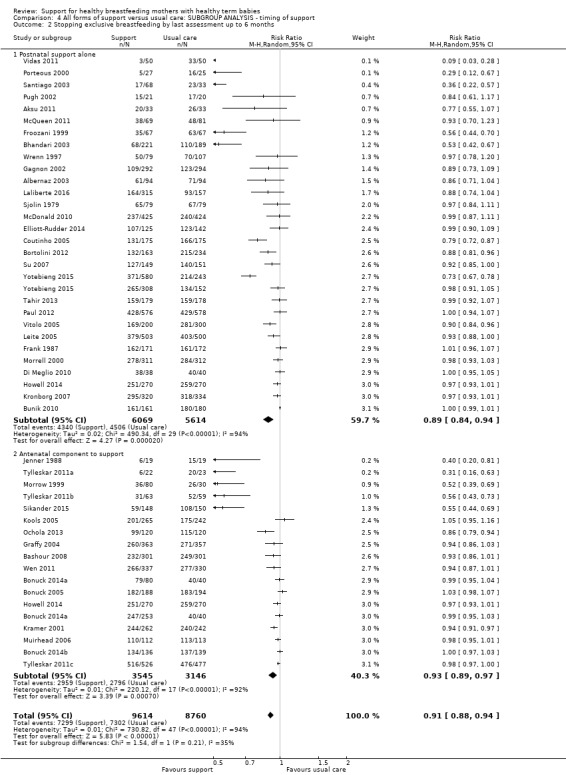

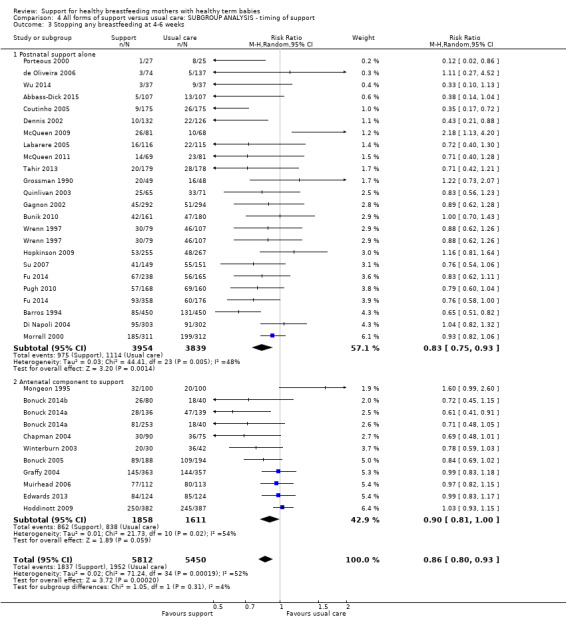

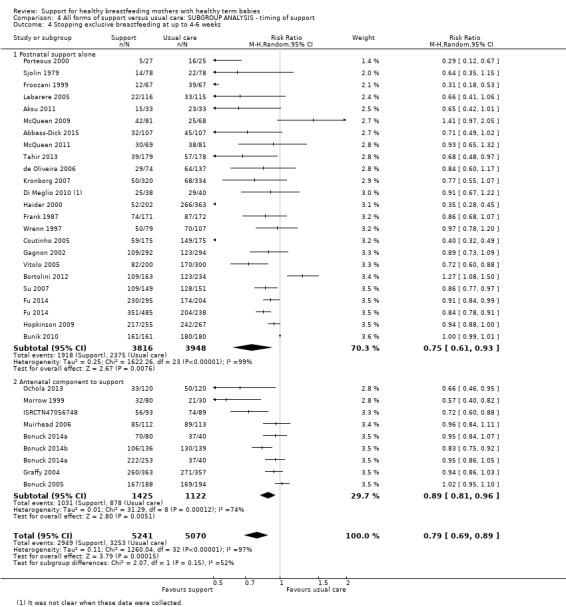

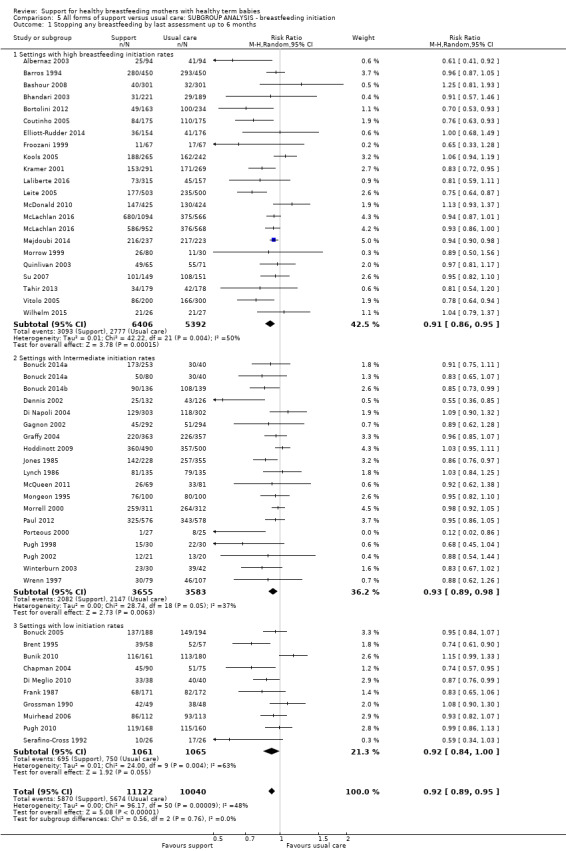

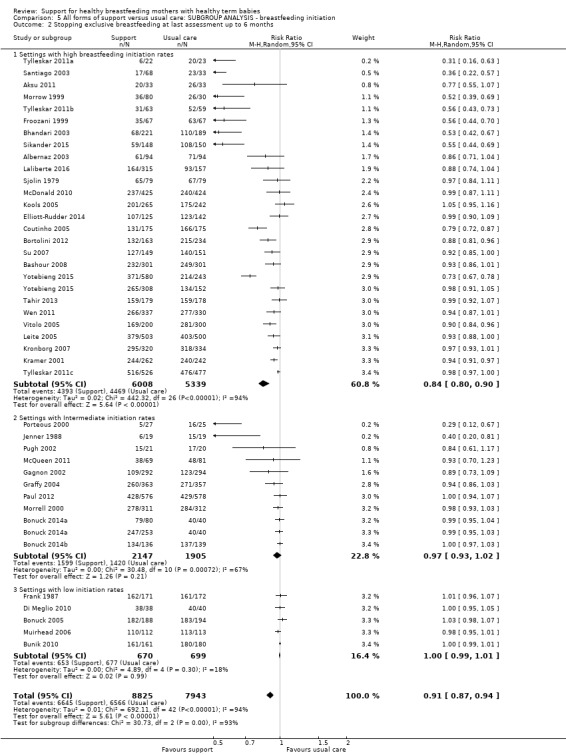

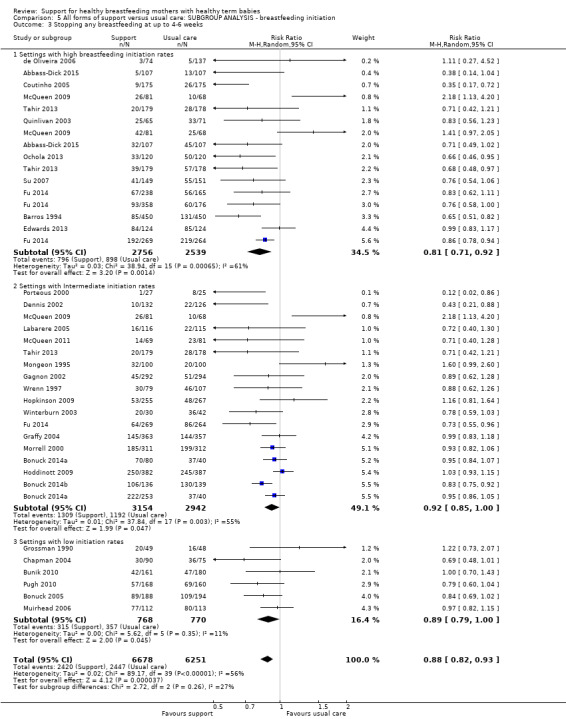

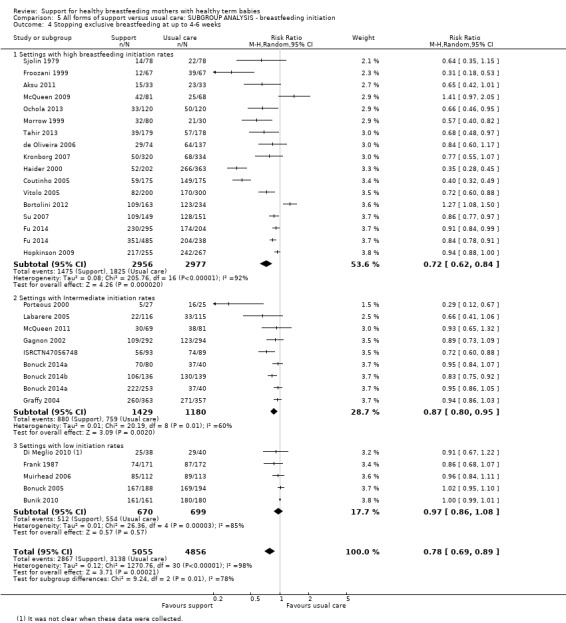

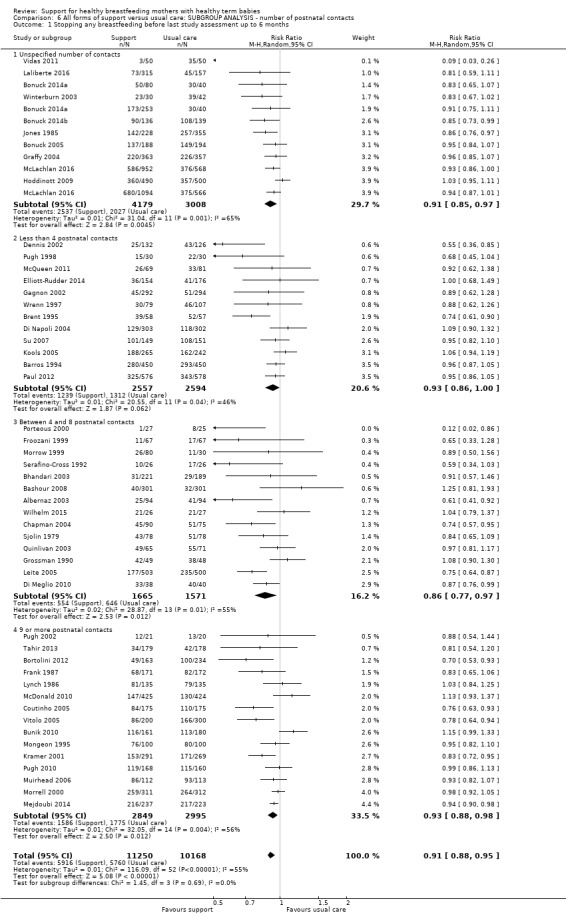

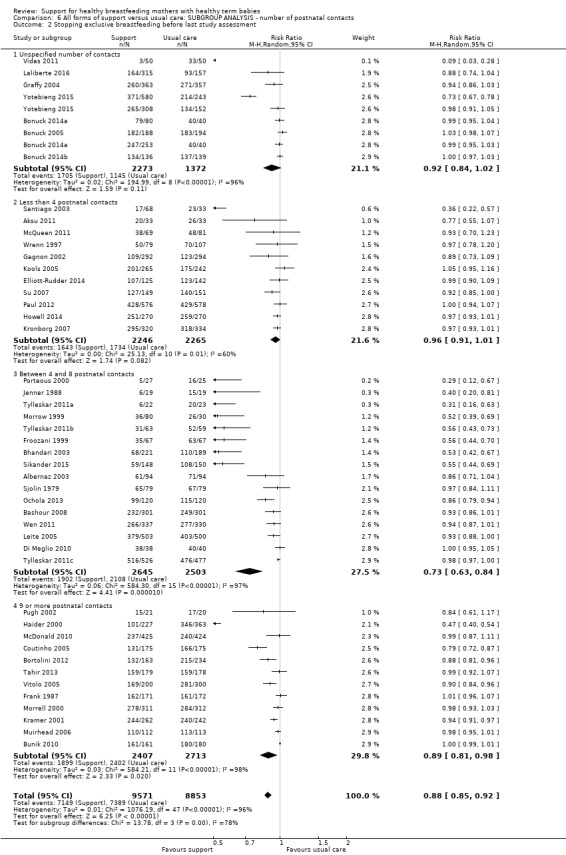

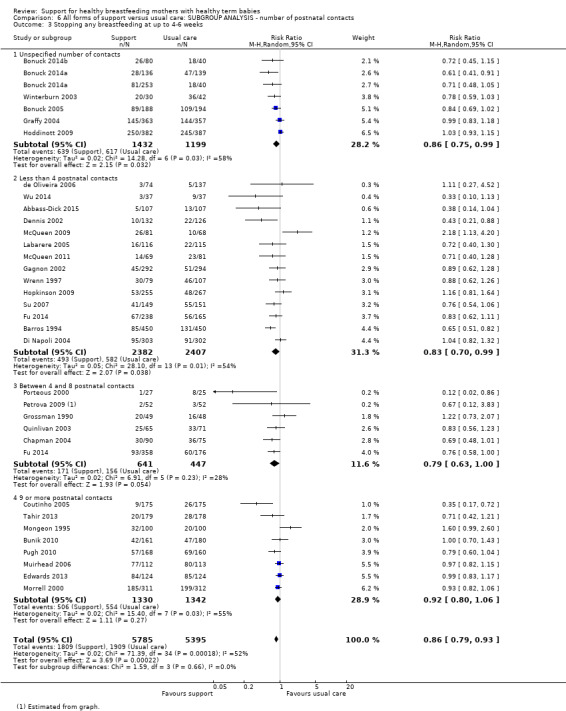

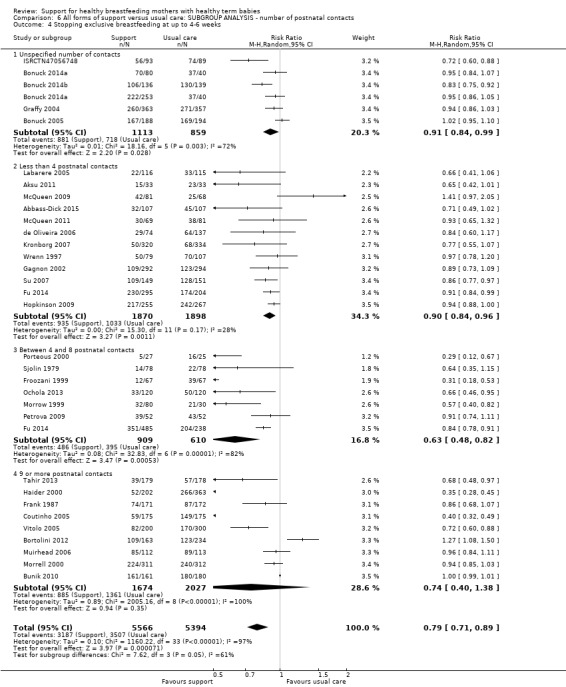

This updated review includes 100 trials involving more than 83,246 mother‐infant pairs of which 73 studies contribute data (58 individually‐randomised trials and 15 cluster‐randomised trials). We considered that the overall risk of bias of trials included in the review was mixed. Of the 31 new studies included in this update, 21 provided data for one or more of the primary outcomes. The total number of mother‐infant pairs in the 73 studies that contributed data to this review is 74,656 (this total was 56,451 in the previous version of this review). The 73 studies were conducted in 29 countries. Results of the analyses continue to confirm that all forms of extra support analyzed together showed a decrease in cessation of 'any breastfeeding', which includes partial and exclusive breastfeeding (average risk ratio (RR) for stopping any breastfeeding before six months 0.91, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.88 to 0.95; moderate‐quality evidence, 51 studies) and for stopping breastfeeding before four to six weeks (average RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.80 to 0.95; moderate‐quality evidence, 33 studies). All forms of extra support together also showed a decrease in cessation of exclusive breastfeeding at six months (average RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.85 to 0.92; moderate‐quality evidence, 46 studies) and at four to six weeks (average RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.89; moderate quality, 32 studies). We downgraded evidence to moderate‐quality due to very high heterogeneity.

We investigated substantial heterogeneity for all four outcomes with subgroup analyses for the following covariates: who delivered care, type of support, timing of support, background breastfeeding rate and number of postnatal contacts. Covariates were not able to explain heterogeneity in general. Though the interaction tests were significant for some analyses, we advise caution in the interpretation of results for subgroups due to the heterogeneity. Extra support by both lay and professionals had a positive impact on breastfeeding outcomes. Several factors may have also improved results for women practising exclusive breastfeeding, such as interventions delivered with a face‐to‐face component, high background initiation rates of breastfeeding, lay support, and a specific schedule of four to eight contacts. However, because within‐group heterogeneity remained high for all of these analyses, we advise caution when making specific conclusions based on subgroup results. We noted no evidence for subgroup differences for the any breastfeeding outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

When breastfeeding support is offered to women, the duration and exclusivity of breastfeeding is increased. Characteristics of effective support include: that it is offered as standard by trained personnel during antenatal or postnatal care, that it includes ongoing scheduled visits so that women can predict when support will be available, and that it is tailored to the setting and the needs of the population group. Support is likely to be more effective in settings with high initiation rates. Support may be offered either by professional or lay/peer supporters, or a combination of both. Strategies that rely mainly on face‐to‐face support are more likely to succeed with women practising exclusive breastfeeding.

Plain language summary

Support for breastfeeding mothers

What is the issue?

The World Health Organization recommends that infants should be breastfed exclusively until six months of age with breastfeeding continuing as an important part of the infant’s diet until he or she is at least two years old. We know that breastfeeding is good for the short‐term and long‐term health of both infants and their mothers. Babies are less likely to develop infections in the digestive tract, lungs or airways, and ears. They are also less likely to become overweight and develop diabetes later in life. The mothers are less likely to develop diabetes and to experience breast or ovarian cancer. Many mothers may stop breastfeeding before they want to as a result of the problems they encounter. Good care and support may help women solve these problems so that they can continue to breastfeed.

Why is this important?

By knowing what kind of support can be provided to help mothers with breastfeeding, we can help them solve any problems and continue to breastfeed for as long as they want to, wherever they live. Stopping breastfeeding early may cause disappointment and distress for mothers and health problems for themselves and their infants. Support can be in the form of giving reassurance, praise, information, and the opportunity for women to discuss problems and ask questions as needed. This review looked at whether providing extra organised support for breastfeeding mothers would help mothers to continue to breastfeed when compared with standard maternity care. We were interested in support from health professionals including midwives, nurses and doctors, or from trained lay workers such as community health workers and volunteers.

What evidence did we find?

We searched for evidence on 29 February 2016 and identified a further 31 new trials for inclusion in the review. This updated review now includes 100 randomised controlled studies involving more than 83,246 women. The 73 trials that contributed to the analyses were from 29 countries and involved 74,656 women. Some 62% of the women were from high‐income countries, 34% from middle income countries and 4% from low‐income countries

All forms of extra organised support analyzed together showed an increase in the length of time women continued to breastfeed, either with or without introducing any other types of liquids or foods. This meant that fewer women stopped any breastfeeding or exclusively breastfeeding (moderate quality evidence) before four to six weeks and before six months. Both trained volunteers and doctors and nurses had a positive impact on breastfeeding.

Factors that may have contributed to the success for women who exclusively breastfed were face‐to‐face contact (rather than contact by telephone), volunteer support, a specific schedule of four to eight contacts and high numbers of women who began breastfeeding in the community or population (background rates).

The term 'high‐quality evidence' means that we are confident that further studies would provide similar findings. No outcome was assessed as being 'high‐quality'. The term 'moderate‐quality evidence' means that we found wide variations in the findings with some conflicting results in the studies in this review. New studies of different kinds of support for exclusive breastfeeding may change our understanding of how to help women to continue with exclusive breastfeeding.

The methodological quality of the studies was mixed and the components of the standard care interventions and extra support interventions varied a lot and were not always well described. Also, the settings for the studies and the women involved were diverse.

What does this mean?

Providing women with extra organised support helps them breastfeed their babies for longer. Breastfeeding support may be more helpful if it is predictable, scheduled, and includes ongoing visits with trained health professionals including midwives, nurses and doctors, or with trained volunteers. Different kinds of support may be needed in different geographical locations to meet the needs of the people within that location. We need additional randomised controlled studies to identify what kinds of support are the most helpful for women.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. All forms of support versus usual care.

| All forms of support versus usual care | ||||||

| Patient or population: healthy breastfeeding mothers with healthy term babies Setting: outpatient settings in multiple countries (8% low‐ or lower‐middle income; 30% upper‐middle income; 60% high‐income countries) Intervention: all forms of support Comparison: usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments1 | |

| Risk with usual care | Risk with all forms of support | |||||

| Stopping breastfeeding (any) before last study assessment up to 6 months | Study population | average RR 0.91 (0.88 to 0.95) | 21418 (51 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE2 | We have not downgraded evidence for lack of blinding. However, no trial had adequate blinding of pregnant women or staff. | |

| 573 per 1000 | 510 per 1000 (487 to 532) | |||||

| Stopping exclusive breastfeeding before last study assessment up to 6 months | Study population | average RR 0.88 (0.85 to 0.92) | 18591 (46 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 3, 4 | ||

| 823 per 1000 | 732 per 1000 (707 to 765) | |||||

| Stopping breastfeeding (any) at up to 4‐6 weeks | Study population | average RR 0.87 (0.80 to 0.95) | 11264 (33 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE5 | ||

| 353 per 1000 | 304 per 1000 (279 to 329) | |||||

| Stopping exclusive breastfeeding at up to 4‐6 weeks | Study population | RR 0.79 (0.71 to 0.89) | 10960 (32 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 4, 6 | ||

| 642 per 1000 | 507 per 1000 (443 to 571) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Sensitivity analyses restricted to trials of low risk of bias for allocation concealment showed similar effects for all four outcomes, with a reduction in effect size of (0 to 0.08) and minimal differences in confidence intervals.

2 Statistical heterogeneity, downgraded one level (I² = 55%).

3 Statistical heterogeneity, downgraded one level (I² = 96%).

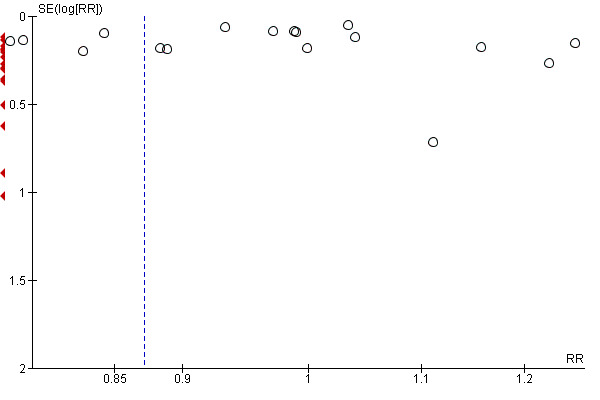

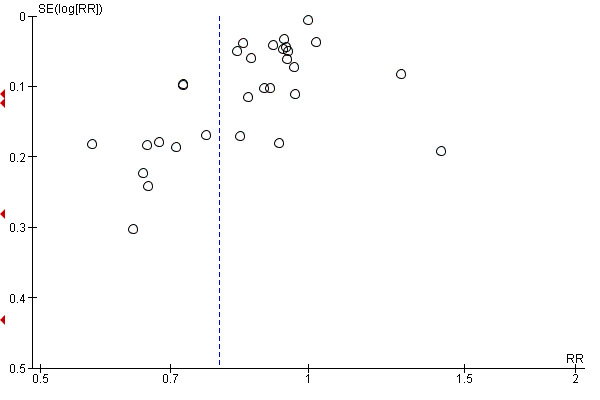

4 There is some evidence of funnel plot asymmetry due to small studies with large effect sizes. Not downgraded.

5 Statistical heterogeneity, downgraded one level (I² = 54%).

6 Statistical heterogeneity, downgraded one level (I² = 97%).

Background

Description of the condition

Breastfeeding has a fundamental impact on the short‐, medium‐ and long‐term health of children and has an important impact on women’s health (Victora 2016). For children, good quality evidence demonstrates that in both low‐, middle‐ and high‐income settings not breastfeeding contributes to mortality due to infectious diseases (Sankar 2015), hospitalisation for preventable disease such as gastroenteritis, and respiratory disease (Horta 2013), otitis media (Bowatte 2015), increased rates of childhood diabetes and obesity (Horta 2015a), and increased dental disease (Peres 2015; Tham 2015). For women, there is good quality evidence that not breastfeeding is associated with increased risks of breast and ovarian cancer, and diabetes (Chowdhury 2015). Lactational amenorrhoea is associated with exclusive/predominant breastfeeding and increases birth spacing when other forms of contraception are not available (Chowdhury 2015). Not being breastfed has an adverse impact on intelligence quotient (IQ), and educational and behavioural outcomes for the child (Heikkilä 2014; Heikkilä 2011; Horta 2015b; Quigley 2012). For many outcomes a dose‐response relationship exists, with the greatest benefit resulting from breastfeeding exclusively, with no added food or fluids, for around six months, with breastfeeding continuing thereafter as an important component of the infant’s diet (Kramer 2012). The negative impact of not breastfeeding has been demonstrated in a range of settings and population groups, though the balance of risks and benefits varies from setting to setting; for example, gastroenteritis will result in much higher mortality in low‐income countries (Horta 2013).

Few health behaviours have such a broad‐spectrum and long‐lasting impact on population health, with the potential to improve life chances, health and well‐being. Victora 2016 estimated that each year, 823,000 deaths in children under five years and 20,000 deaths from breast cancer could be prevented by near universal breastfeeding. The cost burden of not breastfeeding was estimated by Rollins 2016 to represent 0.49% of world gross domestic product. The cost burden includes the cost of caring for children and women with chronic disease as well as short‐term illness (Bartick 2010; Smith 2010).

The established negative impact on a population of not breastfeeding has resulted in global and national support for encouraging the initiation and continuation of breastfeeding. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that, wherever possible, infants should be fed exclusively on breastmilk until six months of age (WHO 2003), with breastfeeding continuing as an important part of the infant’s diet until at least two years of age. Other agencies and countries have endorsed the recommendation to breastfeed exclusively to around six months of age (EFSA Panel 2009; National Center for Health Statistics 2012).

Due to the lack of standardised infant feeding indicators in high‐income countries, it is difficult to compare rates of breastfeeding across high‐income countries, or between high‐income, and low‐ and middle‐income countries. Therefore reported rates of breastfeeding need to be treated with caution. Victora 2016 suggest that, in general, there is an inverse relationship between breastfeeding rates and national wealth, though this relationship does not necessarily hold at the level of population subgroups. In high‐income countries, for example, the relationship is often seen to be the opposite, with rates higher among more affluent women (McAndrew 2012).

Although some high‐income countries such as, Norway and Finland have high rates of both initiation and continuation of breastfeeding (Cattaneo 2010), rates in many high‐income countries are low. Initiation rates have risen in some high‐income countries in recent years (NHS England 2014; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2011), but there remains a marked decline in breastfeeding within the first few weeks after initiation, and exclusive breastfeeding to six months is rare (Cattaneo 2010; McAndrew 2012).

In middle‐ and low‐income countries, while breastfeeding initiation and duration are generally higher than in high‐income countries, the average rate of exclusive breastfeeding for children younger than six months is only 37% (Victora 2016). However, rates of exclusive breastfeeding for children younger than six months vary widely; Peru and Rwanda report rates of 72% and 85% respectively (UNICEF 2012), while in Nigeria the rate is only 17%. In some low‐ and middle‐income countries, cultural practices such as prelacteal feeds, and giving water or teas alongside breastfeeding, account for the low rates of exclusive breastfeeding (Kimani‐Murage 2011). This is particularly important as when breastfeeding continues for long periods of time, infant and young child mortality are reduced in the second year of life in low‐ and middle‐income countries (Victora 2016).

Infant feeding is strongly related to inequalities in health, and, far from being an individual decision made by each woman, is influenced most strongly by structural determinants of health. The range of different rates of initiation and continuation of breastfeeding in different settings globally demonstrates that the key factors influencing infant feeding rates are likely to be sociocultural and related to societal and subgroup norms, public policy, and the availability of appropriate care and support, both professional and lay (EU Project on Promotion of Breastfeeding 2004; Rollins 2016). In high‐income countries, for example, young mothers and women in low‐income groups, or women who ceased full‐time education at an early age, are least likely either to start breastfeeding or to continue for a period of time sufficient to benefit from the greatest health gain (McAndrew 2012). Migrant women have been shown to adopt breastfeeding practices that are more similar to the country in which they live, than the country of their birth (McLachlan 2006).

The early discontinuation of breastfeeding is not a decision that is taken lightly by women; it is associated with a high prevalence of problems such as painful breasts and nipples, concern about adequacy of milk supply and about the baby’s behaviour, and, in some settings, embarrassment related to breastfeeding in public. Many mothers report distress related to the decision to discontinue breastfeeding (McAndrew 2012), even in cultures where breastfeeding rates are high (Almqvist‐Tangen 2012). A key factor is the widespread lack of appropriate education for health professionals in the prevention and treatment of breastfeeding problems, which means that in a wide range of settings women commonly do not receive the quality of care needed from the health services (Cattaneo 2010; Renfrew 2006). Enkin 2000 notes that industrial societies, on the whole, do not provide women with the opportunity to observe other breastfeeding women before they attempt breastfeeding themselves. In such societies, where breastfeeding is not normative behaviour and women may find it socially challenging to breastfeed, women are at particular risk of finding a serious lack of support to continue breastfeeding.

Description of the intervention

‘Support’ is complex and can include several elements such as emotional and esteem‐building support (including reassurance and praise), practical help, informational support (including the opportunity to discuss and respond to women’s questions) and social support (including signposting women to support groups and networks) (Dykes 2006; Schmied 2011). It can be offered in a range of ways, by health professionals or lay people, trained or untrained, in hospital and community settings. It can be offered to groups of women or one‐to‐one, it can involve mother‐to‐mother support, and it can include family members (typically fathers or grandmothers) and wider communities. Support can be offered proactively by contacting women directly, or reactively, by waiting for women to get in touch. It can be provided face‐to‐face, by telephone or through social media. It can involve only one contact or regular, ongoing contact over several months.

Support is a complex intervention that tackles the multifaceted challenge of enabling women to breastfeed, and it should not be surprising that it varies from setting to setting and from study to study. However, it is likely that different forms of support in different contexts will be differentially effective. The global Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (Baby Friendly Initiative in some countries), which is a complex intervention incorporating 10 steps to successful breastfeeding, has been shown to be associated with increased breastfeeding rates (Labbok 2012; Pérez‐Escamilla 2016; Venancio 2011). Over 21,000 facilities in 198 countries have ever been accredited, representing 27.5% of maternities worldwide (Labbok 2012), but most babies are still not born in a Baby Friendly environment.

In many settings, the health professionals who provide standard maternity care lack in‐depth knowledge of the prevention and treatment of breastfeeding problems. Therefore training and education of health professionals and others who provide breastfeeding support is critical. To address this, WHO and UNICEF (the United Nations Children's Fund) have developed two breastfeeding training programmes: the 40‐hour Breastfeeding Counselling, and the five‐day Infant and Young Child Feeding Counselling, to train a cadre of health workers that can provide skilled support to breastfeeding mothers and help them overcome problems (WHO/UNICEF 1993; WHO/UNICEF 2006).

How the intervention might work

Support for breastfeeding women can work in different ways for different women. Timely, skilled support will help women to avoid or overcome breastfeeding problems that may lead to cessation of breastfeeding. In settings where breastfeeding is not the social norm, support can increase women’s belief in breastfeeding, and give them confidence to continue breastfeeding in the face of societal and family pressures that might undermine breastfeeding. In settings where exclusive breastfeeding is rare, support can dispel myths about the need for additional foods or fluids alongside breastfeeding to meet babies’ nutritional needs.

Why it is important to do this review

It is fundamentally important to examine the support that mothers receive when breastfeeding to determine what might be effective in helping women continue to breastfeed, whatever setting they live in. There is evidence that effective breastfeeding support interventions are cost‐effective and likely to realise a return on investment within a few years (Renfrew 2012a).

The purpose of this review is to examine interventions which provide extra support for mothers who are breastfeeding or considering breastfeeding; and to assess their impact on breastfeeding duration and exclusivity and, where recorded, on health outcomes and maternal satisfaction. This review is an update of the previously published version Renfrew 2012b. The focus of this review is support for mothers and babies who are part of the general healthy population of their countries; mothers of premature and sick babies and mothers with some medical conditions have additional issues with breastfeeding, and interventions to support these mothers need to be reviewed separately. A Cochrane Review of breastfeeding education and support for mothers with multiple pregnancies is in progress (Whitford 2015). Whilst many support interventions include breastfeeding education for mothers, our review excludes interventions described as solely educational in nature and interventions with no postnatal component. A Cochrane Review of antenatal breastfeeding education for increasing breastfeeding duration has been published (Lumbiganon 2012).

Specific objectives of this review are to describe forms of support which have been evaluated in controlled studies, and the settings in which they have been used. It was also of interest to examine the effectiveness of different modes of offering similar supportive interventions (for example, face‐to‐face or over the telephone), whether interventions containing both antenatal and postnatal elements were more effective than those taking place in the postnatal period alone, and whether the support was offered proactively to women, or whether they needed to seek it out. We also planned to examine the effectiveness of different care providers, and the possible impact of background breastfeeding rates in the countries or areas where the trials took place on the effectiveness of supportive interventions. It is important to note that the support interventions offered were in addition to standard care, which varied from setting to setting, though there are few settings in which standard care is consistently offered by people with training and skill in enabling women to breastfeed.

Objectives

To describe forms of breastfeeding support which have been evaluated in controlled studies, the timing of the interventions and the settings in which they have been used.

To examine the effectiveness of different modes of offering similar supportive interventions (for example, whether the support offered was proactive or reactive, face‐to‐face or over the telephone), and whether interventions containing both antenatal and postnatal elements were more effective than those taking place in the postnatal period alone.

To examine the effectiveness of different care providers and (where information was available) training.

To explore the interaction between background breastfeeding rates and effectiveness of support.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials, with or without blinding. Cluster‐randomised controlled trials were also eligible for inclusion.

Types of participants

Participants were healthy pregnant women considering or intending to breastfeed or healthy women who were breastfeeding healthy babies.Healthy women and babies were considered those who did not require additional medical care (e.g. women with diabetes, women with HIV/AIDs, overweight or obese women) or surgical care (e.g. women who required a Caesarean Section). Studies which focused specifically on women with additional care needs were excluded.

Types of interventions

Contact with an individual or individuals (either professional or volunteer) offering support which is supplementary to the standard care offered in that setting. ‘Support’ interventions eligible for this review could include elements such as reassurance, praise, information, and the opportunity to discuss and to respond to the mother’s questions, and could also include staff training to improve the supportive care given to women. It could be offered by health professionals or lay people, trained or untrained, in hospital and community settings. It could be offered to groups of women or one‐to‐one, including mother‐to‐mother support, and it could be offered proactively by contacting women directly, or reactively, by waiting for women to get in touch. It could be provided face‐to‐face or over the phone, and it could involve only one contact or regular, ongoing contact over several months. Studies were included if the intervention occurred in the postnatal period alone or also included an antenatal component. Interventions taking place in the antenatal period alone were excluded from this review, as were interventions described as solely educational in nature.

Types of outcome measures

The main outcome measure was the effect of the interventions on stopping breastfeeding by specified points in time. Primary outcomes were recorded for stopping any or exclusive breastfeeding before four to six weeks and before six months postpartum. Other outcomes of interest in previous versions of this review were stopping any or exclusive breastfeeding at other time points (two, three, four, nine and 12 months), measures of neonatal and infant morbidity (where available) and measures of maternal satisfaction with care or feeding method. Secondary outcomes were not considered in this update so that the review could be completed in time to inform the World Health Organisation’s review of the evidence and update of the WHO recommendations on breastfeeding in maternity facilities. A new set of core outcomes for Cochrane pregnancy and childbirth breastfeeding reviews is currently being developed and the outcomes from this core set may influence future outcomes chosen for this review.

Primary outcomes

Stopping breastfeeding before six months postpartum.

Stopping exclusive breastfeeding before six months postpartum.

Stopping any breastfeeding before four to six weeks postpartum.

Stopping exclusive breastfeeding before four to six weeks postpartum.

Secondary outcomes

We did not consider secondary outcomes in this 2016 update.

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register by contacting their Information Specialist (29 February 2016).

The Register is a database containing over 22,000 reports of controlled trials in the field of pregnancy and childbirth. For full search methods used to populate Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register including the detailed search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL; the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service, please follow this link to the editorial information about Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth in the Cochrane Library and select the ‘Specialized Register ’ section from the options on the left side of the screen.

Briefly, Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register is maintained by their Information Specialist and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

monthly searches of CINAHL (EBSCO);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals, plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Search results are screened independently by two people and the full text of all relevant trial reports identified through the searching activities described above is reviewed. Based on the intervention described, each trial report is assigned a number that corresponds to a specific Pregnancy and Childbirth review topic (or topics), and is then added to the Register. The Information Specialist searches the Register for each review using this topic number rather than keywords. This results in a more specific search set, which has been fully accounted for in the relevant review sections (Included studies; Excluded studies; Studies awaiting classification; Ongoing studies).

(For details of search methods used in previous versions of this review, please see: Britton 2007; Renfrew 1995; Renfrew 2012b; Sikorski 1999; Sikorski 2002)

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of retrieved studies.

We did not apply any language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For methods used in the previous version of this review, seeRenfrew 2012b.

For this update, the following methods (based on a standard template used by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth) were used for assessing the 162 reports that were identified as a result of the updated search.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed all the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy for inclusion. We resolved any disagreement through discussion and consulted a third review author if required.

Data extraction and management

We designed and piloted a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted information using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion. Data were entered into Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 2014), and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding study methods and results was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (the Handbook) (Higgins 2011). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

For each included study, we described the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

For each included study, we described the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

For each included study, we described the method used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

For each included study, we described the method used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

For each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, we described the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses that we undertook.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

For each included study, we described how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s prespecified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s prespecified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011).

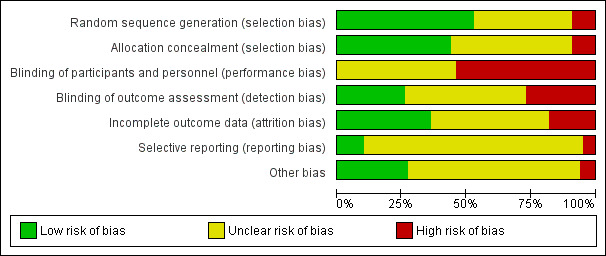

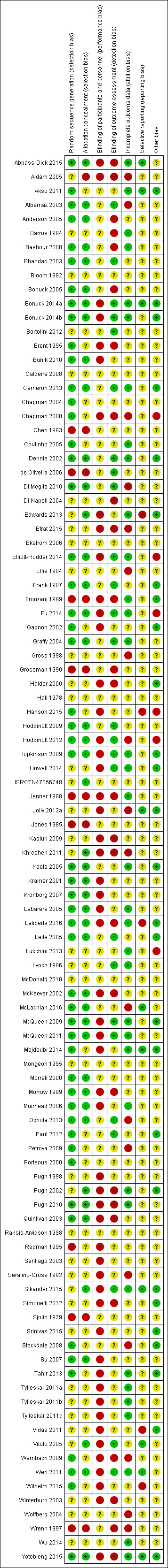

Overall findings for our assessment of risk of bias in the included studies are set out in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

1.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Assessment of the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach

For this update the quality of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach as outlined in the GRADE handbook in order to assess the quality of the body of evidence relating to the following primary outcomes for the comparison, All forms of support versus usual care.

Stopping breastfeeding before six months postpartum.

Stopping exclusive breastfeeding before six months postpartum.

Stopping any breastfeeding before four to six weeks postpartum.

Stopping exclusive breastfeeding before four to six weeks postpartum.

The GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool was used to import data from Review Manager 5.3 in order to create ’Summary of findings’ tables (RevMan 2014). A summary of the intervention effect and a measure of quality for each of the above outcomes was produced using the GRADE approach. The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence can be downgraded from 'high quality' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates or potential publication bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

There are no continuous data in this review.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

There are 15 cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses. Their sample sizes have been adjusted using the methods described in the Handbook and by Donner 2000 incorporating an estimate of the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible). Where cluster adjusted confidence limits were presented but not the ICC, the design effect was estimated from comparison with limits based on the raw numbers. However, for Ochola 2013, outcome one of Elliott‐Rudder 2014, arm two of Yotebieng 2015, adjusting for clustering based on the summary statistic made the standard error larger and the width of the confidence interval increased which resulted in a design of <1. Therefore, the adjustment for clustering resulted in an increase of the error sum of squares for the raw numbers given. As this was nonsensical, no adjustment for clustering was made for these studies. We have synthesised the findings from individually‐ and cluster‐randomised trials provided that there was little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit was considered to be unlikely. We have carried out sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of including cluster‐randomised trials where no adjustment was possible. For all trials where ICCs were not reported, study authors will be contacted in the next version of the review.

Trials with multiple groups

In order to avoid 'double counting' in studies involving one control group and two different interventions groups, we split the control group number of events and participants in half, so that we could include two independent comparisons, as per methods described the Handbook [section16.5.4].

Dealing with missing data

For all outcomes, analyses were carried out, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

For included studies, we have noted levels of attrition. We have not included outcomes in the analyses where more than 25% of the data were missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if I² was greater than 30% and either Tau² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity. If we identified substantial heterogeneity (above 30%), we planned to explore it by prespecified subgroup analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

For all outcomes we have ordered studies in terms of weight, where a sufficient number of studies contributed data, we have generated funnel plots. We examined plots visually to see whether there was any evidence of asymmetry that might suggest different treatment effects in smaller studies, which may indicate publication bias (Harbord 2006). We note however, that there are many other reasons for asymmetry in Funnel Plots such as heterogeneity.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 2014). At the outset, we had anticipated that there would be some heterogeneity between studies in terms of the interventions and the populations studied, we therefore decided to use random‐effects meta‐analysis for combining data. Random‐effects meta‐analysis estimates the average treatment effect, and this may not always be clinically meaningful. Furthermore, where there is high heterogeneity the applicability of the overall effect estimate is likely to vary in different settings and we therefore advise caution in the interpretation of results. The random‐effects summary was treated as the average of the range of possible treatment effects and we discuss the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect was not clinically meaningful, we planned not to combine trials. Since we used random‐effects analyses, the results were presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of Tau² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If we identified substantial heterogeneity, we investigated it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We considered whether an overall summary was meaningful, and if it was, we used random‐effects analysis to produce it.

We carried out the following subgroup analyses for the four primary outcomes.

By type of supporter (professional versus lay person, or both).

By type of support (face‐to‐face versus telephone support).

By timing of support (antenatal and postnatal versus postnatal alone).

By whether the support was proactive (scheduled contacts) or reactive (women needed to request support).

By background breastfeeding initiation rates (low, medium or high background rates).

By intensity of support (number of scheduled contacts).

Sensitivity analysis

We have carried out sensitivity analysis for primary outcomes by study quality; we did this by dividing the studies into subgroups according to whether they were at low risk of bias as opposed to unclear or high risk of bias. We have performed this for allocation concealment. Because we have excluded studies from any analyses if they had more than 25% attrition, we have not conducted sensitivity analyses for this item.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

In this updated version, we assessed 162 reports and have subsequently included a further 31 studies. We excluded 68 studies and have assigned the remainder as either an additional report of another study in the review, a study awaiting classification or an ongoing study (seeStudies awaiting classification and Characteristics of ongoing studies). This review now therefore includes 100 studies and has excluded 147 studies.

This updated review is only focused on two primary outcomes each at two different time points. Of the 31 new studies included in this update, 21 studies provided data for one or more of the primary outcomes (see Table 2). Ten new trials met the inclusion criteria for this review but were excluded from the analyses either because they did not present data in a useable form or because of attrition rates >25%. Eleven studies provided data for outcome 1.1; 13 studies for outcome 1.2; eight studies for outcome 1.3; and eight studies for outcome 1.4. The addition of these studies to the studies included in the previous version of the review meant that for this 2016 update a total of 51 studies contributed data for outcome 1.1; 46 studies for outcome 1.2; 33 studies for outcome 1.3; and 32 studies for outcome 1.4.

1. Summary of included studies from 2016 update.

| Study | RCT 2‐arm | RCT 3‐arm | RCT 4‐arm | Cluster | Background breastfeeding rates (low, medium, high) | Type of supporter (professional, lay person, both) | Type of support (face‐to‐face, telephone) | Timing of support (antenatal (ante) + postnatal (post), or post alone) | Whether support was: proactive (scheduled contacts) or reactive (women needed to request support) | Number of postnatal contacts (< 4, 4‐8, 9+) | Data included in outcome 1 | Data included in outcome 2 | Data included in outcome 3 | Data included in outcome 4 |

| Abbas‐Dick 2015 | x | High | Professional | Face‐to‐face and telephone | Post alone | Proactive | < 4 | N | N | Y | Y | |||

| Bonuck 2014 (BINGO trial) | x | Medium | Professional | Face‐to‐face and telephone | Post alone | Proactive | Unclear | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Bonuck 2014a (PAIRINGS trial) | x | Medium | Professional | Face‐to‐face and telephone | Ante and post | Proactive | Unclear | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Bortolini 2012 | x | High | Professional | Face‐to‐face | Post alone | Proactive | 9+ | Y | Y | N | Y | |||

| Cameron 2013 | x | High | Professional | Face‐to‐face | Ante and post | Proactive | < 4 | N | N | N | N | |||

| Chapman 2008 | x | Medium | Professional | Face‐to‐face and telephone | Ante and post | Proactive | 9+ | N | N | N | N | |||

| Edwards 2013 | x | High | Lay | Face‐to‐face | Ante and post | Unclear | 9+ | N | N | Y | N | |||

| Efrat 2015 | x | High | Professional | Telephone | Ante and post | Proactive | 9+ | N | N | N | N | |||

| Elliott‐Rudder 2014 | x | x | High | Professional | Face‐to‐face | Post alone | Proactive | < 4 | Y | Y | N | N | ||

| Fu 2014 | x | x | High | Professional | Telephone | Post alone | Proactive | 4 to 8 | N | N | Y | Y | ||

| Hanson 2015 | x | x | High | Lay | Face‐to‐face | Ante and post | Proactive | 4 to 8 | N | N | N | N | ||

| Hoddinott 2012 | x | Medium | Professional | Telephone | Post | Proactive | 9+ | N | N | N | N | |||

| Howell 2014 | x | High/low | Professional | Face‐to‐face and telephone | Post | Proactive | < 4 | N | Y | N | N | |||

| Jolly 2012 | x | x | Low | Lay | Face‐to‐face or telephone | Ante and post | Proactive | 4 to 8 | N | N | N | N | ||

| Laliberte 2016 | x | High | Professional | Face‐to‐face | Post alone | Proactive | Unclear | Y | Y | N | N | |||

| Lucchini 2013 | x | High | Professional | Face‐to‐face | Post | Proactive | < 4 | N | N | N | N | |||

| McLachlan 2016 | x | x | High | Professional | Face‐to‐face | Post alone | Proactive | Unclear | Y | N | N | N | ||

| McQueen 2009 | x | High | Professional | Face‐to‐face and telephone | Post alone | Proactive | < 4 | N | N | Y | Y | |||

| Mejdoubi 2014 | x | High | Professional | Face‐to‐face | Ante and post | Proactive | 9+ | Y | N | N | N | |||

| Ochola 2013 | x | x | High | Lay | Face‐to‐face | Ante and post | Proactive | 4 to 8 | N | Y | N | Y | ||

| Paul 2012 | x | Medium | Professional | Face‐to‐face | Post alone | Proactive | < 4 | Y | Y | N | N | |||

| Sikander 2015 | x | x | High | Professional | Face‐to‐face | Ante and post | Proactive | 4 to 8 | N | Y | N | N | ||

| Simonetti 2012 | x | High | Professional | Telephone | Post alone | Proactive | 4 to 8 | N | Y | N | N | |||

| Srinivas 2015 | x | Medium | Lay | Face‐to‐face and telephone | Ante and post | Proactive | > 9 | N | N | N | N | |||

| Stockdale 2008 | x | Medium | Professional | Face‐to‐face | Ante and post | Unclear | Unclear | N | N | N | N | |||

| Tahir 2013 | x | High | Professional | Face‐to‐face | Post alone | Proactive | 9+ | N | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Vidas 2011 | x | Unknown | Professional | Face‐to‐face | Post alone | Unclear | Unclear | N | Y | N | N | |||

| Wen 2011 | x | High | Professional | Face‐to‐face | Ante and post | Proactive | 4 to 8 | N | Y | N | N | |||

| Wilhelm 2015 | x | High | Professional | Face‐to‐face | Post alone | Proactive | 4 to 8 | Y | N | N | N | |||

| Wu 2014 | x | Unknown | Professional | Face‐to‐face and telephone | Post alone | Proactive | < 4 | N | N | Y | N | |||

| Yotebieng 2015 | x | x | High | Professional | Face‐to‐face | Post alone | Proactive | Unclear | N | Y | N | N | ||

| 25 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 11 | 13 | 8 | 8 |

Abbreviations

ante: antenatally N: no post: postnatally Y: yes

In the results section we will not discuss further those studies that did not contribute data to the review, but additional information about these trials is provided in the Characteristics of included studies table and further details about the eleven new trials from the update is also provided in Table 2.

Included studies

This updated review includes 100 trials involving more than 83,246 mother‐infant pairs of which 73 studies contribute data (58 individually‐randomised trials and 15 cluster‐randomised trials).

Description of included studies (n = 73)

Seventy‐three of the 100 included studies contribute data to this 2016 update of the review. It should be noted that two of the included trials were obtained via a single publication (Bonuck 2014a); one trial is called the BINGO trial and the other called the PAIRING trial. In order to differentiate between these two trials in this review the BINGO trial is identified via the reference (Bonuck 2014a) and the PAIRING trial via the reference (Bonuck 2014b).

The total number of mother‐infant pairs in these studies is 74,656 (this total was 56,451 in the previous version of this review (Renfrew 2012b). The 73 studies were published/conducted between 1979 and 2016 and show increases over time both in number of studies (five studies are dated before 1990, 10 between 1990 and 1999, 40 between 2000 and 2011, and 18 are dated between 2012 and 2016), and range of country settings (the seven studies with dates before 1994 were all undertaken in high‐income countries, and the eight studies from low‐/low‐middle income countries were published in 2000 or later). The data in this review come from participants living in 29 countries. Using the World Bank classification of countries by income (http://data.worldbank.org/about/country‐classifications/country‐and‐lending‐groups, accessed 30 June 2016):

four studies with 3260 participants (4.4% of the total number of participants) were conducted in low‐income countries (Bangladesh, Haider 2000; Burkina Faso and Uganda, Tylleskar 2011a and Tylleskar 2011b; and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Yotebieng 2015);

four studies with 2534 participants (3.4%) were conducted in low‐middle income countries (India, Bhandari 2003; Kenya, Ochola 2013; Pakistan, Sikander 2015; and Syria, Bashour 2008);

15 studies with 22,477 participants (30.1%) were conducted in upper‐middle income countries (Belarus, Kramer 2001; Brazil, Albernaz 2003, Barros 1994, Bortolini 2012, Coutinho 2005, de Oliveira 2006, Leite 2005, Santiago 2003, and Vitolo 2005; China, Wu 2014; Iran, Froozani 1999; Malaysia, Tahir 2013; Mexico, Morrow 1999; Turkey, Aksu 2011; and South Africa, Tylleskar 2011c1);

52 studies with 46,390 participants (62.1%) were conducted in high‐income countries (Australia, Elliott‐Rudder 2014, McLachlan 2016, McDonald 2010, Quinlivan 2003, and Wen 2011; Canada, Abbass‐Dick 2015, Dennis 2002, Gagnon 2002, Laliberte 2016, Lynch 1986, Mongeon 1995, McQueen 2011, and Porteous 2000; Croatia, Vidas 2011; Denmark, Kronborg 2007; France, Labarere 2005, and McQueen 2009; Hong Kong, Wu 2014; Italy, Di Napoli 2004; Netherlands, Kools 2005, and Mejdoubi 2014; Singapore, Su 2007; Sweden, Ekstrom 2006, and Sjolin 1979; UK, Graffy 2004, Hoddinott 2009, Jones 1985, Jenner 1988, Morrell 2000, Muirhead 2006, ISRCTN47056748, and Winterburn 2003; USA, Bonuck 2014a, Bonuck 2014b, Bonuck 2005, Brent 1995, Bunik 2010, Chapman 2004, Di Meglio 2010, Edwards 2013, Frank 1987, Grossman 1990, Hopkinson 2009, Howell 2014, Paul 2012, Petrova 2009, Pugh 1998, Pugh 2002, Pugh 2010, Serafino‐Cross 1992, Wilhelm 2015, and Wrenn 1997).

1 Note: The Tylleskar study, Tylleskar 2011a, Tylleskar 2011b, and Tylleskar 2011c, was undertaken in three countries, two are in the low‐income and one in the upper‐middle income World Bank category. In this review, we have entered data into the analyses separately for each country.

Methods used in trials

The 73 studies include 58 individually‐randomised trials and 15 cluster‐randomised trials (Bhandari 2003; Ekstrom 2006; Elliott‐Rudder 2014; Fu 2014; Haider 2000; Hoddinott 2009; Kools 2005; Kramer 2001; Kronborg 2007; McLachlan 2016; Morrow 1999; Ochola 2013; Sikander 2015; Tylleskar 2011a; Tylleskar 2011b; Tylleskar 2011c; Yotebieng 2015).

Participants and setting

Socioeconomic and health status

Participants were women from the general healthy population of their countries. However, 28 of the 73 studies were undertaken with women from low‐income groups within their country. These 28 studies include 16 of the 20 USA studies, with four other studies from high‐income countries (Jones 1985; Mejdoubi 2014; Quinlivan 2003; Wen 2011), three of the studies from Brazil (Barros 1994; Coutinho 2005; Vitolo 2005), three of the studies from low‐middle income countries (Ochola 2013; Sikander 2015; Yotebieng 2015), and the two studies from low‐income countries. In one of these (Haider 2000, Bangladesh), participants were mainly of lower‐middle and low socioeconomic status. In the other (Tylleskar 2011a; Tylleskar 2011b; Tylleskar 2011c), participants came from three countries in sub‐Saharan Africa, with those in one country (Uganda) from low‐income groups within that country. With regard to health of the general population of countries, Tylleskar 2011a; Tylleskar 2011b; Tylleskar 2011c reported local HIV prevalence rates of 10% to 34% in the South Africa study sites; during recruitment, women who had not been HIV tested were encouraged to visit the antenatal clinic, and those who had HIV‐positive status were recruited into another study.

Background rates of breastfeeding initiation/'ever breastfed'

Among the 73 studies, World Bank country income group shows an inverse relationship with background rates of breastfeeding initiation ('ever breastfed'). All the studies with intermediate (60% to < 80%, n = 18) or low (< 60%, n = 11) background rates of breastfeeding initiation were undertaken in high‐income countries. Nine of the 11 studies with low background rates recruited women from low‐income groups in the USA (Brent 1995; Bonuck 2005; Bunik 2010; Chapman 2004; Di Meglio 2010; Frank 1987; Grossman 1990; Pugh 2002; Serafino‐Cross 1992); the remaining two (UK) studies were from areas of Scotland with lower breastfeeding initiation rates than the Scottish average (Hoddinott 2009; Muirhead 2006). All the country income groups are represented among the 24 studies with high (≥ 80%) rates, however the seven studies from low‐/low‐middle income countries all had high rates. Where background rates of 'ever breastfed' were not reported, we have used either rates published in the WHO Global Data Bank on Infant and Young Child Feeding (www.who.int/nutrition/databases/infantfeeding/countries/en/index; accessed July 2016), or those published in the supplementary material to Victora 2016, and for the two studies from Scotland (Hoddinott 2009; Muirhead 2006), we used www.isdscotlandarchive.scot.nhs.uk/isd/1914 (accessed November 2016). For one study that was conducted in China (Wu 2014), data were not presented in the paper or available in the WHO Global Data Bank on Infant and Young Child Feeding and so were therefore excluded from the sensitivity analysis.

Interventions

Level of the intervention

In 64/73 studies, women received the intervention. In eight studies the intervention was additional training in breastfeeding support for staff (five cluster‐randomised trials; Bhandari 2003; Ekstrom 2006; Elliott‐Rudder 2014; Kramer 2001; Yotebieng 2015; and three individually‐randomised trials; Labarere 2005; Santiago 2003; ISRCTN47056748). One cluster‐randomised trial evaluated a policy for providing breastfeeding groups (Hoddinott 2009).

Breastfeeding support: proactive/indirect

In 58 of the 64 studies where women received the intervention and seven of the eight studies of staff training, breastfeeding support was delivered directly to women. However, in two of these studies although the support was offered proactively initially, it was up to the women to request follow‐up support (Bonuck 2014a; Laliberte 2016). In five other studies (Graffy 2004; Hoddinott 2009; Labarere 2005; Morrell 2000; Winterburn 2003), breastfeeding support was not offered proactively; women were encouraged to access it, but breastfeeding support was not delivered directly to women as part of these interventions. One study evaluated a multi‐faceted intervention, of which breastfeeding support delivered directly to women was one component (Kools 2005). For two studies it was not clear if the support was offered proactively or not (Edwards 2013; Vidas 2011).

One‐to‐one/group support

In 57 of the 73 studies there was individual, one‐to‐one contact between the breastfeeding supporter and the breastfeeding mother. Two studies offered group support (Hoddinott 2009; Vidas 2011), one offered both individual and group support (Ekstrom 2006), one study offered support to couples (Abbass‐Dick 2015), and in two studies this aspect of support was unclear (Kools 2005; Kramer 2001).

Breastfeeding support from professional/lay supporters

In the previous version of this review, the people providing breastfeeding support were categorised as 'professional', 'lay and professional' or 'lay'. Using those categories, the 73 studies in this update comprise 49 studies of professional support, nine of lay and professional support and 15 of lay support. In view of the growing body of work evaluating breastfeeding peer support, we have distinguished between this and other kinds of lay support, following the definition by Dennis 2002: “Peer support is provided by lay individuals who are not part of the client’s own embedded network, who possess experiential knowledge of the targeted behaviour (i.e. successful breastfeeding skills) and similar qualities (i.e. age, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, residency etc.) in order to aid the client during a time of actual or potential stress (i.e. the initiation and continuation of breastfeeding)."

Professional

In 49 of the 73 studies a variety of medical, nursing and allied professionals (for example, nutritionists, lactation consultants and researchers) provided the breastfeeding support (Abbass‐Dick 2015; Albernaz 2003; Bashour 2008; Barros 1994Bonuck 2005; Bonuck 2014a; Bonuck 2014b; Bortolini 2012; Brent 1995; Bunik 2010; de Oliveira 2006; Di Napoli 2004; Ekstrom 2006; Elliott‐Rudder 2014; Frank 1987; Froozani 1999; Fu 2014; Gagnon 2002; Grossman 1990; Howell 2014; Jones 1985; Kramer 2001; Kronborg 2007; Laliberte 2016; Lynch 1986; McLachlan 2016; McDonald 2010; McQueen 2009; McQueen 2011; Mejdoubi 2014; Paul 2012; Petrova 2009; Porteous 2000; Pugh 1998; Quinlivan 2003; Santiago 2003; Serafino‐Cross 1992; Sikander 2015; ISRCTN47056748; Sjolin 1979; Su 2007; Tahir 2013; Vidas 2011; Vitolo 2005; Wen 2011; Wilhelm 2015; Wrenn 1997; Wu 2014; Yotebieng 2015).

Professional and lay

Professionals provided breastfeeding support with other people in a further nine studies; para‐professionals (Kools 2005; Morrell 2000), peer supporters (Bhandari 2003; Hopkinson 2009; Pugh 2002; Pugh 2010), and lay people (employees who had to be mothers in Barros 1994; someone chosen by the mother in Winterburn 2003; and a group of mothers in Hoddinott 2009).

Lay

Lay people provided breastfeeding support in 17 studies. In twelve of these, the lay people were peer supporters (Chapman 2004; Dennis 2002; Di Meglio 2010; Edwards 2013; Haider 2000; Leite 2005; Morrow 1999; Muirhead 2006; Ochola 2013; Tylleskar 2011a; Tylleskar 2011b; Tylleskar 2011c). The other five studies did not report that the lay supporters met the Dennis 2002 criteria for us to classify them as peer supporters (Aksu 2011; Coutinho 2005; Graffy 2004; Jenner 1988; Mongeon 1995).

Training in breastfeeding support

Overall, 50 of the 73 studies reported that the people providing breastfeeding support had additional training to provide breastfeeding support (33/49 professional, 3/9 professional and lay, and 14/15 peer/lay). In 10 studies the professionals were International Board Certified Lactation Consultants (IBCLC) (Bonuck 2014a; Bonuck 2014b; Bortolini 2012; Brent 1995; Fu 2014; Laliberte 2016; Petrova 2009; Pugh 1998; Tahir 2013; Yotebieng 2015).

In one of the studies of support from professionals and paraprofessionals, the professionals were lactation consultants (Kools 2005), and in the other they were midwives not stated to have had extra training in breastfeeding support (Morrell 2000); in both these studies the para‐professionals were trained to refer women with breastfeeding problems to the professionals. Two of the four studies of support from professionals and peers reported training; in Bhandari 2003 peer supporters received WHO‐based training, and in Hopkinson 2009 the professionals were IBCLCs and the peer supporters had three days' training in lactation management, 20 hours' training in peer counselling and at least one year’s work experience. One of the three studies study of professional and lay support stated that lay supporters received breastfeeding support training (Barros 1994).

All 10 studies of peer support (alone) reported that peer supporters were trained. The training was WHO 20 hours (Leite 2005), 40 hours (Haider 2000; Ochola 2013) or one week (Tylleskar 2011a; Tylleskar 2011b; Tylleskar 2011c); La Leche League (LLL) 30 hours (Chapman 2004), 20 hours (Di Meglio 2010); over 30 weeks (Edwards 2013), or not specified (Morrow 1999). Two studies reported the length but not the type of training; 2.5 hours and more than two days (Dennis 2002; Muirhead 2006, respectively). Three of the five studies of lay support (alone) reported breastfeeding training; WHO 18 hours plus five days (Coutinho 2005), WHO 18 hours (Aksu 2011), and National Childbirth Trust training (Graffy 2004).

Mode of support (face‐to‐face or by telephone, or both)

Forty‐seven of the 73 studies offered telephone support and all but two of these were undertaken in countries classified as high‐income countries by the World Bank (Albernaz 2003, Brazil; Wu 2014, China). Four studies offered breastfeeding support only by telephone (Bunik 2010; Dennis 2002; Di Meglio 2010; Fu 2014). Thirty offered both face‐to‐face and telephone support, with telephone support either predominating (e.g. Muirhead 2006; Petrova 2009), or as backup (e.g. Chapman 2004). In some studies (e.g. Kools 2005; Pugh 1998), telephone contact with the breastfeeding support specialist came after the women had been visited by someone else. Across the 27 studies examining telephone support, details about whether or not the telephone support was proactively offered by the peer or professional supporter were not reported consistently. Thirty‐eight studies offered only face‐to‐face support. In the one remaining study (Winterburn 2003), the support was not proactive and the mode of support was not specified.

Support with an antenatal component and intention to breastfeed

The outcomes of interventions intended to promote longer duration of breastfeeding could be expected to differ according to whether women were recruited before or after they started to breastfeed. Two‐thirds of the studies (49/73) included postnatal women at or after initiation of breastfeeding. In the one study of breastfeeding in groups (Hoddinott 2009), pregnant women and breastfeeding mothers could be invited to attend groups. The remaining 24 studies recruited women before the birth, not all of whom went on to initiate breastfeeding. Six of the 24 studies included only women who intended to breastfeed (Kramer 2001 in Belarus; Jenner 1988 and Winterburn 2003 in the UK; Serafino‐Cross 1992 in the USA; Mongeon 1995 in Canada; Tylleskar 2011a; Tylleskar 2011b; Tylleskar 2011c in Burkina Faso, Uganda and South Africa). In the Tylleskar 2011 study, this inclusion criterion was related to HIV/AIDS prevention and management in the country and study populations. The other studies that recruited before the birth did not specify that participants had to intend to breastfeed.

Intensity of the intervention

Sixty of the 73 studies reported the intensity of the intervention in terms of the number of postnatal contacts the mother could have for breastfeeding support. Twenty‐four studies specified three or fewer contacts, 21 specified four to eight contacts, and the remaining 17 studies specified nine or more contacts. We have performed a subgroup analysis and the results are described in the text.

Control group care

Seven of the 73 studies were undertaken in hospital settings with Baby Friendly accreditation (Aksu 2011; Chapman 2004; Coutinho 2005; de Oliveira 2006; ISRCTN47056748; Tahir 2013; Yotebieng 2015). However, in the study by Yotebieng 2015, the intervention was the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) so the control group did not access this. For the other six studies undertaken in settings with Baby Friendly accreditation, study interventions were additional to care that met Baby Friendly standards and were received by everyone at the hospital including all the study participants in the intervention and control groups. In two community‐based cluster‐randomised trials (Hoddinott 2009; Kronborg 2007), most of the maternity hospitals in which the participants had given birth had Baby Friendly accreditation.

In 29 studies control group care was not specified (n = 9) or stated to be standard care but not described (n = 20). In the remaining studies there was some description of control group care (see Characteristics of included studies). Standard postnatal care varies both between and within countries. Care may have differed within the study period and may also have differed from that which is offered at the present time.

Outcomes

Level of data collection

In 66 of the 73 studies outcome data were collected from the women who had received the intervention. In the other seven studies, the relationship between the recipients of the intervention and the source of the outcome data varied. In the three individually‐randomised trials of staff training (ISRCTN47056748; Labarere 2005; Santiago 2003), outcome data came from all the women randomised to receive, or not to receive, a support intervention from trained staff. In one of the three cluster‐randomised trials of staff training (Ekstrom 2006), data came from mothers of singleton term healthy infants at centres where staff had been randomised, or not randomised, to receive training. In another (Bhandari 2003), trained staff visited all families in the intervention villages and outcome data were collected from all infants in the intervention and control villages, and in the third (Kramer 2001), staff in all intervention sites were trained and data were collected from mothers who intended to breastfeed in the intervention and control sites. In the cluster‐randomised trial that evaluated a policy for providing breastfeeding groups (Hoddinott 2009), the policy intervention was made at locality level. Pregnant or postnatal women could be invited to groups in intervention clusters; however, only 1310 pregnant or breastfeeding women out of more than 9000 births in the intervention localities attended any group.

Duration of any and/or exclusive breastfeeding

Breastfeeding duration was most commonly assessed at six months. A total of 51 studies measured any breastfeeding at six months and 46 studies measured exclusive breastfeeding at six months. For the other primary outcomes, 33 studies measured any breastfeeding at four to six weeks and 32 measured exclusive breastfeeding at four to six weeks. When data on both seven‐day and 24‐hour recall were provided, we selected the data for 24‐hour recall.

The breastfeeding outcomes reported reflect World Bank country income group of the countries in which the 73 studies were undertaken. Most studies (29/52) reported the effect of the intervention on rates of both any and exclusive breastfeeding. Some studies report details about data collection that make it clear that duration of exclusive breastfeeding at specific time points was not necessarily measured from birth (Tylleskar 2011a; Tylleskar 2011b; Tylleskar 2011c; Vitolo 2005); most studies did not report this level of detail.

Secondary outcomes

Details of secondary outcomes were not collected for this update but will be included in the next update in two years time.

In the previous version of this review (Renfrew 2012b), a few studies reported various infant morbidity and maternal satisfaction with feeding and care outcomes by intervention group: infant morbidity was reported in 11 studies (Bashour 2008; Bhandari 2003; Bunik 2010; Frank 1987; Froozani 1999; Kramer 2001; Morrow 1999; Petrova 2009; Pugh 2002; Quinlivan 2003; Tylleskar 2011a; Tylleskar 2011b; Tylleskar 2011c); maternal satisfaction with feeding in 11 studies (Bashour 2008; de Oliveira 2006; Dennis 2002; Hoddinott 2009; Hopkinson 2009; Kronborg 2007; Labarere 2005; McDonald 2010; McQueen 2011; Petrova 2009; Pugh 1998), and maternal satisfaction with care in six studies (Bashour 2008; Ekstrom 2006; Graffy 2004; Jones 1985; Kools 2005; Morrow 1999).

Excluded studies

The previous version of this review excluded 79 studies from the review and we have excluded a further 68 studies. Thus 147 studies have been excluded with reasons (see Characteristics of excluded studies). The main reason for exclusion was because studies were not randomised trials, or it was not clear that allocation to groups had been carried out randomly; we excluded 18 studies identified by the search for this reason (Caulfield 1998; Davies‐Adetugbo 1996; Ebbeling 2007; Garcia‐Montrone 1996; Hall 2007; Jang 2008; Kistin 1994; McInnes 2000; Moreno‐Manzanares 1997; Neyzi 1991; Nor 2009; Pascali‐Bonaro 2004; Perez‐Escamilla 1992; Segura‐Millan 1994; Sisk 2006; Susin 2008; Thussanasupap 2006; Valdes 2000). A further two papers were reviews rather than reports of a randomised controlled trials (Guise 2003; Lewin 2005).

We excluded 72 trials because the intervention was not relevant to this review. We excluded 42 trials on the grounds that studies examined educational interventions where the focus was on instruction rather than on support to women to encourage breastfeeding (Ahmed 2016; Beiler 2011; Benitez 1992; Bolam 1998; Cattaneo 2001; Christie 2011; Edwards 2013a; Ehrlich 2014; Finch 2015; Flax 2014; Forster 2004; Giglia 2015; Girish 2013; Hanafi 2014; Harari 2014; Hauck 1994; Henderson 2001; Isselmann 2006; Jakobsen 2008; Jones 2004; Labarere 2003; Labarere 2011; Lavender 2004; Louzada 2012; Mattar 2003; Perez‐Blasco 2013; Phillips 2011; Pollard 1998; Rea 1999; Rossiter 1994; Sakha 2008; Schy 1996; Svensson 2013; Szucs 2015; Tully 2012; Vianna 2011; Vitolo 2012; Vitolo 2014; Wallace 2006; Wan 2011; Westphal 1995; Williams 2014). We excluded a further 13 trials as the intervention was not designed to support continued breastfeeding; these studies examined more general interventions in the postnatal period (Ball 2011; Barlow 2006; Barnet 2002; Black 2001; Gagnon 1997; MacArthur 2002; Peterson 2002; Pollard 2011; Ratner 1999; Rush 1991; Serrano 2010; Thomson 2009; Wiggins 2005); a further trial by Baqui 2008 focused on breastfeeding initiation only, rather than on postnatal support to encourage continuation. Eleven of the studies examined interventions carried out in the antenatal period only, and had no postnatal support component (Forster 2006; Jahan 2014; Johnston 2001; Katepa‐Bwalya 2011; Kronborg 2012; MacArthur 2009; Olenick 2011; Otsuka 2012; Noel‐Weiss 2006; Reeve 2004; Wockel 2009).

We excluded 25 of the studies that we assessed for inclusion as they did not focus on healthy mothers with healthy, term infants. Five trials examined interventions for low birthweight babies (Agrasada 2005; Brown 2008; Junior 2007; Pinelli 2001; Thakur 2012), while the Ahmed 2008 study recruited only mothers of premature babies. The Davies‐Adetugbo 1997 and Haider 1996 studies recruited the mothers of babies with severe diarrhoea, the Merewood 2006, Phillips 2010 and Phillips 2012 studies recruited only mothers of babies admitted to neonatal intensive care units, and the Pound 2015 study only included babies with jaundice. The Ferrara 2008 and Stuebe 2016 trials focused on an intervention for mothers with diabetes, the Martin 2015 and Carlsen 2013 studies focused on overweight women, and the Gijsbers 2006 and Mesters 2013 trials on families with a history of asthma, while Moore 1985 looked at infants with a parent with eczema or asthma. Three other trials recruited only women in high‐risk groups (Chapman 2011; McLeod 2003; Rasmussen 2011). Two studies focused providing support for fathers (Byas 2011; Tohotoa 2012), and one study concerned training for student nurses (Davis 2014).

The remaining trials were excluded for other reasons (Bica 2014; Finch 2002; Haider 2014; Hives‐Wood 2013; Hoddinott 2012a; Lieu 2000; Mannan 2008; Nkonki 2014; Nor 2012; Ochola 2013a; Penfold 2014; Rasmussen 2011; Rowe 1990; Sciacca 1995; Steel O'Connor 2003; Thakur 2012; Wasser 2015). Further details of these, and other excluded studies, can be found in the Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

Risk of bias in included studies

Each trial was assessed for methodological quality as outlined in the Methods section (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Allocation

Random sequence generation: we considered that a little over half of the studies included in the review used methods that were at low risk of bias to generate the randomisation sequence: we deemed 54 studies to be at low risk; nine studies at high risk and 38 studies to be at unclear risk.

Allocation concealment: we considered that a little less than half of the studies included in the review used methods that were at low risk of bias to conceal allocation to experimental groups: we deemed 44 studies to be at low risk; nine studies at high risk and 48 studies to be at unclear risk.

Blinding

Blinding participants and personnel: with interventions of this type, it is very difficult to assess risk of bias associated with blinding. Both the mothers and the staff providing care would probably be aware that they were either receiving or delivering an intervention. In studies where there was randomisation at the clinic level, all women may have been exposed to the same intervention, and contamination between groups would thereby be reduced, but there may still have been a risk of response bias if outcomes were reported to staff providing care. Therefore, we assessed no studies as being at a low risk of bias for this domain.

Blinding of outcome assessment: we assessed approximately one‐quarter of studies as being at low risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessment: we deemed 27 studies to be at low risk, 27 studies to be at high risk, and 47 studies at unclear risk.

Incomplete outcome data

We had prespecified that we would not include data for any outcome where there were missing data for more than 25% of the randomised group. Loss to follow‐up was a particular problem in studies where women were recruited in the antenatal period and, as we have described above, we have not included any outcome data from studies that were otherwise eligible for inclusion in the review because of high levels of attrition for all outcomes. For some of those studies that contributed data there was still considerable loss to follow‐up, and loss was not always balanced across randomisation groups. When assessing incomplete outcome data, reasons for loss of data were not taken into consideration.

We judged approximately one‐third of studies to be at low risk of bias for incomplete outcome data: we deemed 36 studies to be at low risk; 18 studies at high risk and 47 studies to be at unclear risk.

Selective reporting