Abstract

Background

Psychotic disorders can lead some people to become agitated. Characterised by restlessness, excitability and irritability, this can result in verbal and physically aggressive behaviour ‐ and both can be prolonged. Aggression within the psychiatric setting imposes a significant challenge to clinicians and risk to service users; it is a frequent cause for admission to inpatient facilities. If people continue to be aggressive it can lengthen hospitalisation. Haloperidol is used to treat people with long‐term aggression.

Objectives

To examine whether haloperidol alone, administered orally, intramuscularly or intravenously, is an effective treatment for long‐term/persistent aggression in psychosis.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register (July 2011 and April 2015).

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCT) or double blind trials (implying randomisation) with useable data comparing haloperidol with another drug or placebo for people with psychosis and long‐term/persistent aggression.

Data collection and analysis

One review author (AK) extracted data. For dichotomous data, one review author (AK) calculated risk ratios (RR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) on an intention‐to‐treat basis based on a fixed‐effect model. One review author (AK) assessed risk of bias for included studies and created a 'Summary of findings' table using GRADE.

Main results

We have no good‐quality evidence of the absolute effectiveness of haloperidol for people with long‐term aggression. One study randomising 110 chronically aggressive people to three different antipsychotic drugs met the inclusion criteria. When haloperidol was compared with olanzapine or clozapine, skewed data (n=83) at high risk of bias suggested some advantage in terms of scale scores of unclear clinical meaning for olanzapine/clozapine for 'total aggression'. Data were available for only one other outcome, leaving the study early. When compared with other antipsychotic drugs, people allocated to haloperidol were no more likely to leave the study (1 RCT, n=110, RR 1.37, CI 0.84 to 2.24, low‐quality evidence). Although there were some data for the outcomes listed above, there were no data on most of the binary outcomes and none on service outcomes (use of hospital/police), satisfaction with treatment, acceptance of treatment, quality of life or economics.

Authors' conclusions

Only one study could be included and most data were heavily skewed, almost impossible to interpret and oflow quality. There were also some limitations in the study design with unclear description of allocation concealment and high risk of bias for selective reporting, so no firm conclusions can be made. This review shows how trials in this group of people are possible ‐ albeit difficult. Further relevant trials are needed to evaluate use of haloperidol in treatment of long‐term/persistent aggression in people living with psychosis.

Plain language summary

Haloperidol for long‐term aggression in psychosis

Background

People experiencing distressing delusions and hallucinations can often become agitated and aggressive. The antipsychotic drug haloperidol is widely used for the treatment of schizophrenia and psychosis‐induced agitation despite the possibility it can cause a number of serious side effects such as nausea, vomiting, dizziness, restlessness and muscle spasms.

Study characteristics

The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group ran an electronic search for clinical trials involving the use of haloperidol for psychosis‐induced aggression in July 2011 and April 2015. We found one study with 110 participants, diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Participants had been physically aggressive during recent hospitalisation and involved in at least one other aggressive event. The study randomised participants to receive either haloperidol, clozapine or olanzapine.

Key results

Most data presented were impossible to use and it is unclear if haloperidol is effective for reducing aggression or improving mental state for people who are aggressive due to psychosis. There were no data regarding side effects. The number of people leaving the study early from each treatment group was similar.

Quality of evidence

The quality of evidence available is low, only one study with a high risk of selective reporting of results provided data. No firm conclusions can be made until further good‐quality data are available.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. HALOPERIDOL versus OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTICS for long‐term aggression in psychosis.

| Haloperidol versus other antipsychotic drugs for long‐term aggression in psychosis | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with long‐term aggression in psychosis Settings: state hospitals ‐ New York, USA Intervention: haloperidol versus other antipsychotic drugs | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | haloperidolaloperidol versus other antipsychotic drugs | |||||

| Specific behaviour: aggression ‐ important decrease in aggression | We identified no trials reporting important decrease in aggression. When we compared haloperidol with olanzapine or clozapine, skewed data (n=83) from 1 small trial at high risk of bias suggested some advantage in terms of scores of unclear clinical meaning for olanzapine/clozapine for 'total aggression'. | |||||

| Specific behaviour: repeated need for tranquillisation | We identified no trials reporting repeated need for tranquillisation. | |||||

| Specific behaviours ‐ threat or injury to others/self | We identified no trials reporting threat or injury to others/self. When we compared haloperidol with olanzapine or clozapine, skewed data (n=83) from 1 small trial at high risk of bias suggested some advantage in terms of scores of unclear clinical meaning for olanzapine/clozapine for 'aggression against property' and 'aggression ‐ physical'. Verbal aggression was not changed. | |||||

| Adverse effects ‐ any serious, specific adverse effects | We identified no trials reporting any serious, specific adverse effects. | |||||

| Global outcomes ‐ overall improvement | We identified no trials reporting overall improvement. When we compared haloperidol with olanzapine or clozapine, skewed data (n=83) from 1 small trial at high risk of bias suggested some advantage in terms of scores of unclear clinical meaning for olanzapine/clozapine for a series of mental state ratings. | |||||

| Leaving the study early | Low1 | RR 1.37 (0.84 to 2.24) | 110 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3,4 | ‐ | |

| 100 per 1000 | 137 per 1000 (84 to 224) | |||||

| Moderate1 | ||||||

| 300 per 1000 | 411 per 1000 (252 to 672) | |||||

| High1 | ||||||

| 500 per 1000 | 685 per 1000 (420 to 1000) | |||||

| Economic outcomes | We identified no trials reporting economic outcomes. | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; n: number of participants; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Moderate control risk equivalent to that of people in the included study. 2 Risk of bias: rated 'serious' ‐ stated to be randomised, but no description on randomisation method provided. 3 Imprecision: rated 'serious' ‐ total number of events was 40, which is significantly lower than 300, 95% confidence interval of the best estimate of effect crosses over the line of no effect. 4 Publication bias: rated 'undetected' ‐ however, it is possible that we did not identify small studies due to a degree of publishing bias.

Background

Description of the condition

Psychosis is associated with a number of mental disorders, including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Symptoms of psychosis include delusions and hallucinations, which can lead some people to become confused, frightened, agitated or a combination of these (APA 2004). Agitation is characterised by restlessness, excitability and irritability, and for some people, this can result in verbal and physical aggressive behaviour (Mohr 2005). Aggression is a frequent cause for admission to inpatient facilities and detention in restrictive environments, and if people continue to exhibit aggressive behaviour, this can prolong hospitalisation and interfere with discharge (Volavka 2002). Aggression within the psychiatric setting imposes a significant challenge to clinicians who have to manage the risk that the service user may present to themselves, other service users and staff (NICE 2005), whilst attempting to make an accurate diagnosis and formulation (Schleifer 2011).

Aggression can be acute or persistent. The former is often to do with the acute reaction to the so called 'positive' symptoms of the illness whilst persistent aggresssion may be to do with chronically untreated illness, partially treated illness, partially responsive illness or problems not directly a function of illness at all (Hodgins 2008).

Description of the intervention

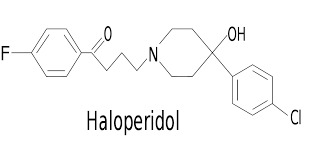

Haloperidol was developed in 1958 by the Belgian company (Janssen Pharmaceutica), and, along with the earlier development of chlorpromazine, was considered a "psychopharmacological revolution" for the treatment of schizophrenia (López‐Munoz 2009; Figure 1). Newer antipsychotic medication has been developed for the day‐to‐day management of symptoms of schizophrenia, however, haloperidol continues to be in wide use, particularly for the management of psychosis‐induced agitation (Pratt 2008).

1.

Haloperidol structure.

The Lundbeck Institute recommend a dosage of 5 mg/day to 15 mg/day, and under clinical supervision up to 100 mg/day. The plasma half‐life after oral dosage is about 17.5 hours; after intravenous (IV) injection it is approximately 15 hours. The release half‐life of the depot is about three weeks, with a steady state after three months. The therapeutic window of serum concentration in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder is 5 ng/mL to 17 ng/mL, and the maximal therapeutic effect occurs at 10 ng/mL (Psychotropics 2003).

Cardiac problems and adverse extrapyramidal effects (e.g. dystonia and akathisia) are associated with conventional antipsychotics such as haloperidol. Experiencing distressing adverse effects may act as a barrier for future engagement with services or treatment (Pratt 2008).

How the intervention might work

Haloperidol is mainly indicated for schizophrenia or other psychosis, mania, violent or dangerously impulsive behaviour, excitement and for short‐term adjunctive management of psychomotor agitation (British National Formulary 2011). Haloperidol is one of the butyrophenone family of antipsychotics (neuroleptics) (López‐Munoz 2009). It is thought that haloperidol prevents the occurrence of delusions and hallucinations by blocking the dopamine D2 receptors in the meso‐cortico‐limbic system; it is less clear how exactly haloperidol may affect aggression. In one study, whilst the dopamine D2 receptor binding was high in the temporal cortex for both haloperidol and atypical antipsychotics, haloperidol induced a significantly higher binding index in the thalamus and striatum than atypical antipsychotics. It is hypothesised that this antidopaminergic activity in the dorsolateral striatum may contribute to the adverse extrapyramidal effects that are associated with typical antipsychotics such as haloperidol (Xiberas 2001).

Why it is important to do this review

Any indication as to whether haloperidol as an intervention will alleviate long‐term aggression in psychosis is important in terms of managing the problem. This review is one of a series covering different treatments used for people whose psychosis is associated with aggression but the majority of these reviews are to do with acute aggression (Table 2).

1. Other relevant Cochrane reviews.

| Focus of review | Reference |

| 'As required' medication | Chakrabarti 2007 |

| Benzodiazepines | Gillies 2005 |

| Chlorpromazine | Ahmed 2010 |

| Containment strategies | Muralidharan 2006 |

| Haloperidol (rapid tranquillisation) | Powney 2011 |

| Haloperidol + promethazine | Huf 2009 |

| Olanzapine IM | Belgamwar 2005 |

| Seclusion and restraint | Sailas 2000 |

| Zuclopenthixol acetate | Gibson 2004 |

Objectives

To examine whether haloperidol alone, administered orally, intramuscularly or intravenously, is an effective treatment for long‐term aggression in psychosis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All relevant randomised controlled trials (RCT) or double blind trials (implying randomisation). We excluded quasi‐randomised studies, such as those allocating by alternate days of the week.

Types of participants

People exhibiting chronic/persistent (i.e. not acute episodes requiring rapid tranquillisation) agitation or aggression, or both concurrently with psychotic illness, regardless of age or sex, and definition used of 'chronic/persistent'.

Types of interventions

1. Haloperidol

Alone, any dose via any route of administration.

Compared with:

a. Other antipsychotic

Any dose via any route of administration.

b. Benzodiazepine

Any dose via any route of administration.

c. Anticonvulsant alone

Any dose via any route of administration.

d. Placebo or no intervention

Types of outcome measures

We planned to divide, where possible, outcomes into short‐term (up to three months), medium‐term (over three and up to six months) and long‐term (over six months).

Primary outcomes

1. Specific behaviours

1.1 Aggression ‐ important decrease in aggression ‐ medium‐term. 1.2 Repeated need for tranquillisation.

2. Adverse effects ‐ any serious, specific adverse effects ‐ medium‐term

Secondary outcomes

1. Specific behaviours

1.1 Self harm, including suicide 1.2 Injury to others 1.3 Aggression 1.3.1 Another episode of aggression ‐ other time periods 1.3.2 Clinically important change in aggression 1.3.3 No change in aggression 1.3.4 Average endpoint in aggression score 1.3.5 Average change in aggression scores

2. Global outcomes

2.1 Overall improvement 2.2 Use of restraints/seclusion 2.3 Relapse ‐ as defined by each study 2.4 Recurrence of violent incidents 2.5 Needing extra visits from the doctor 2.6 Refusing oral medication 2.7 Average endpoint in global score 2.8 Average change in global scores 2.9 Average dose of drug

3. Service outcomes

3.1 Duration of hospital stay 3.2 Re‐admission 3.3 Clinically important engagement with services 3.4 Engagement with services 3.5 Average endpoint engagement score 3.6 Average change in engagement scores

4. Mental state

4.1 Clinically important change in general mental state 4.2 Any change in general mental state 4.3 Average endpoint general mental state score 4.4 Average change in engagement scores

5. Adverse effects

5.1 Death 5.2 Any non‐serious general adverse effects 5.3 Any serious, specific adverse effects ‐ other time periods 5.4 Average endpoint general adverse effect score 5.5 Average change in general adverse effect scores 5.6 Clinically important change in specific adverse effects 5.7 Any change in specific adverse effects 5.8 Average endpoint specific adverse effects 5.9 Average change in specific adverse effects

6. Leaving the study early

6.1 For specific reasons 6.2 For general reasons

7. Satisfaction with treatment

7.1 Recipient of treatment not satisfied with treatment 7.2 Recipient of treatment average satisfaction score 7.3 Recipient of treatment average change in satisfaction scores 7.4 Informal treatment provider not satisfied with treatment 7.5 Informal treatment providers' average satisfaction scores 7.6 Informal treatment providers' average change in satisfaction scores 7.7 Professional providers not satisfied with treatment 7.8 Professional providers' average satisfaction score 7.9 Professional providers' average change in satisfaction scores

8. Acceptance of treatment

8.1 Accepting treatment 8.2 Average endpoint acceptance score 8.3 Average change in acceptance scores

9. Quality of life

9.1 Clinically important change in quality of life 9.2 Any change in quality of life 9.3 Average endpoint quality of life score 9.4 Average change in quality of life score 9.5 Clinically important change in specific aspects of quality of life 9.6 Any change in specific aspects of quality of life 9.7 Average endpoint specific aspects of quality of life 9.8 Average change in specific aspects of quality of life

10. Economic outcomes

10.1 Direct costs 10.2 Indirect costs

11. 'Summary of findings' table

We used the GRADE approach to interpret findings (Schünemann 2011) and GRADE profiler (GRADEPRO) to import data from Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2012) to create 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables provide outcome‐specific information concerning the overall quality of evidence from each included study in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on all outcomes we rated as important to patient‐care and decision making. We aimed to select the following main outcomes for inclusion in the 'Summary of findings' table if obtainable.

1. Specific behaviour: aggression ‐ important decrease in aggression ‐ medium‐term. 2. Specific behaviour: repeated need for tranquillisation. 3. Specific behaviours ‐ threat or injury to others/self. 4. Adverse effects ‐ any serious, specific adverse effects. 5. Global outcomes ‐ overall improvement. 6. Economic outcomes.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Information Specialist searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Study‐Based Register of Trials, July 2011 and 1 April 2015 using the phrase:

(*haloperi* or *R‐1625* or *haldol* or *alased* or *aloperidi* or *bioperido* or *buterid* or *ceree* or *dozic* or *duraperido* or *fortuna* or *serena* or *serenel* or *seviu* or *sigaperid* or *sylad* or *zafri* in intervention of STUDY) AND (*aggress* or *violen* or *agitat* or *tranq* in title, abstract, index terms of REFERENCE or intervention of STUDY)

The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Register of Trials is compiled by systematic searches of major resources (including MEDLINE, CINAHL, Embase, AMED, BIOSIS, PsycINFO, PubMed, and registries of clinical trials) and their monthly updates, handsearches, grey literature and conference proceedings (see Group Module). There are no language, date, document type, or publication status limitations for inclusion of records into the register

Searching other resources

1. Reference searching

We inspected references of all included and excluded studies for further relevant studies.

2. Personal contact

We contacted the first author of each included study for information regarding unpublished trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

One review author (MP) independently inspected citations from the searches and identified relevant abstracts. A second review author (AK) independently re‐inspected the majority to ensure reliability. Where disputes arose, we acquired the full report for more detailed scrutiny. We obtained full reports of the abstracts meeting the review criteria and one review author (AK) inspected these. One review author (MP) re‐inspected the reports in order to ensure reliable selection. Where it was not possible to resolve disagreement by discussion, we attempted to contact the authors of the study for clarification.

Data extraction and management

1. Extraction

One review author (AK) extracted data from the included study and extracted data presented only in graphs and figures whenever possible. If necessary, we attempted to contact authors through an open‐ended request in order to obtain missing information or for clarification whenever necessary.

2. Management

2.1 Forms

One review author (AK) extracted data onto standard, simple forms.

2.2 Scale‐derived data

We did not have any continuous outcomes but if we had come across them we would only have included continuous data from rating scales only if: a. the psychometric properties of the measuring instrument were described in a peer‐reviewed journal (Marshall 2000); and b. the measuring instrument had not been written or modified by one of the trialists for that particular trial.

Ideally the measuring instrument would be either i. a self report or ii. completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist). We realise that this is not often reported clearly, in 'Description of studies' we would have noted if this was the case or not.

2.3 Endpoint versus change data

There are advantages of both endpoint and change data. Change data can remove a component of between‐person variability from the analysis. However, calculation of change needs two assessments (baseline and endpoint), which can be difficult in unstable and difficult to measure conditions such as schizophrenia. We decided to primarily use endpoint data, and only use change data if the endpoint data were not available. We aimed to combine endpoint and change data in the analysis as we would have preferred to use mean differences (MD) rather than standardised mean differences (SMD) throughout (Higgins 2011).

2.4 Skewed data

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, we planned to apply the following standards to relevant continuous data before inclusion.

For endpoint data from studies including fewer than 200 participants:

a. when a scale starts from the finite number zero, we would subtract the lowest possible value from the mean, and divide this by the standard deviation (SD). If this value is lower than one, it strongly suggests that the data are skewed and we would exclude these data. If this ratio is higher than one but less than two, there is suggestion that the data are skewed: we would enter these data and test whether their inclusion or exclusion would change the results substantially. Finally, if the ratio is larger than two, we would include these data, because it is less likely that they are skewed (Altman 1996; Higgins 2011).

b. if a scale starts from a positive value (such as the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), which can have values from 30 to 210 (Kay 1986)), we would modify the calculation described above to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases, skewed data are present if 2 SD > (S ‐ S min), where S is the mean score and 'S min' is the minimum score.

Please note: we would enter all relevant data from studies of more than 200 participants in the analysis irrespective of the above rules, because skewed data pose less of a problem in large studies. We would also enter all relevant change data, as when continuous data are presented on a scale that includes a possibility of negative values (such as change data), it is difficult to tell whether or not data are skewed.

2.5 Common measure

To facilitate comparison between trials, we would have converted variables that could be reported in different metrics, such as days in hospital (mean days per year, per week or per month) to a common metric (e.g. mean days per month).

2.6 Conversion of continuous to binary

Where possible, we aimed to convert outcome measures to dichotomous data. This can be done by identifying cut‐off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into 'clinically improved' or 'not clinically improved'. It is generally assumed that if there is a 50% reduction in a scale‐derived score such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS, Overall 1962) or the PANSS (Kay 1986), this could be considered as a clinically significant response (Leucht 2005a; Leucht 2005b). If data based on these thresholds were not available, we would have used the primary cut‐off presented by the original authors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

One review author (AK) independently assessed risk of bias by using criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) to assess trial quality. This set of criteria is based on evidence of associations between overestimate of effect and high risk of bias of the article such as sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting.

Where advice was sought, if there was any disagreement the final rating was made by consensus, with the involvement of the second review author. Where inadequate details of randomisation and other characteristics of trials were provided, we contacted the authors of the studies in order to obtain further information. Non‐concurrence in quality assessment was reported, but if disputes arose as to which category a trial was to be allocated, again, resolution was made by discussion.

We noted the level of risk of bias in both the text of the review and in the Table 1.

Measures of treatment effect

1. Binary data

For binary outcomes, we calculated a standard estimation of the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). It has been shown that RR is more intuitive (Boissel 1999) than odds ratios and that odds ratios tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000). For statistically significant results, we used 'Summary of findings' tables to calculate the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial (NNTB) or harmful (NNTH) outcome and its 95% CI.

2. Continuous data

We found no continuous outcomes in the included study. If we had found continuous outcomes, we would have estimated the MD between groups, preferring not to calculate effect size measures (SMD). However, if scales of very considerable similarity had been used, we would have presumed that there was a small difference in measurement, and calculated effect size and transformed the effect back to the units of one or more of the specific instruments.

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice) but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. First, authors often fail to account for intra‐class correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992) whereby P values are spuriously low, CIs unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997; Gulliford 1999).

We had one included study, which was not a cluster trial. If we had found cluster trials, we would have assessed whether clustering was accounted for in primary studies. Where clustering had been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we would have presented these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect. Where it was not incorporated, we would have attempted to contact the first authors of studies to obtain intra‐class correlation coefficients (ICCs) for their clustered data and to adjust for this by using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). If the ICC was not reported, we would have assumed it to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

2. Cross‐over trials

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence, on entry to the second phase the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a washout phase. For the same reason, cross‐over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). Our included study was not a cross‐over trial, but if we had found cross‐over trials we would only have used data from the first phase.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups

Our included study did not involve more than two treatment arms. If we had found studies with more than two treatment arms we would have, if relevant, presented the additional treatment arms in comparisons. If data were binary, we would have simply added and combined them within the two‐by‐two table. If data were continuous, we would have combined data following the formula in Section 7.7.3.8 (Combining groups) of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Where the additional treatment arms were not relevant, we would not have used these data.

Dealing with missing data

1. Overall loss of credibility

At some degree of loss of follow‐up, data must lose credibility (Xia 2009). In our included study, more than 50% of data were accounted for. For any particular outcome, if more than 50% of data had been unaccounted for, we would not have reproduced these data or used them within analyses (except for the outcome 'leaving the study early').

2. Binary

Our included study clearly described attrition for binary outcomes. If we had found a case where attrition for a binary outcome was between 0% and 50% and where these data were not clearly described, we would have presented data on a 'once‐randomised‐always‐analyse' basis (an intention‐to‐treat analysis). Participants leaving the study early would have all been assumed to have the same rates of negative outcome as participants who completed, with the exception of the outcome of death and adverse effects. For these outcomes, the rate of participants who stayed in the study ‐ in that particular arm of the trial ‐ would have been used for participants who did not. We did not undertake a sensitivity analysis to test how prone the primary outcome measures were to change when data only from people who completed the study to that point were compared to the intention‐to‐treat analysis using the above assumptions, as there was only one included study.

3. Continuous

3.1 Attrition

If we had found any case where attrition for a continuous outcome was between 0% and 50%, and reported data only from people who complete the study to that point, we would have presented and used these data.

3.2 Standard deviations

If we had found any case where SDs were not reported for continuous data, we would first try to obtain the missing values from the authors. If not available, where there were missing measures of variance for continuous data, but an exact standard error (SE) and CIs available for group means, and either a P value or t value available for differences in mean, we would have calculated them according to the rules described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). When only the SE was reported, we would have calculated SDs using the formula SD=SE × square root (n). Chapters 7.7.3 and 16.1.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions present detailed formula for estimating SDs from P values, t or F values, CIs, ranges or other statistics (Higgins 2011). Where this formula did not apply, we would have calculated the SDs according to a validated imputation method that was based on the SDs of the other included studies (Furukawa 2006).

3.3 Last observation carried forward

We anticipated that some studies would employ the method of last observation carried forward (LOCF) within the study report. As with all methods of imputation to deal with missing data, LOCF introduces uncertainty about the reliability of the results (Leucht 2007). Therefore, where LOCF data were used in the trial, if less than 50% of the data were assumed, we would have reproduced these data and indicated that they were the product of LOCF assumptions.

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity

If we had included more than one study, we would have considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge clinical heterogeneity. We would have inspected all studies for clearly outlying people or situations that we had not predicted would arise. If such situations or participant groups arose, we would have discussed these fully.

2. Methodological heterogeneity

If we had included more than one study, we would have considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge methodological heterogeneity. We would have inspected all studies for clearly outlying methods that we had not predicted would arise. If such methodological outliers arose, we would have discussed these fully.

3. Statistical heterogeneity

3.1 Visual inspection

We would have visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

1. Protocol versus full study

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results. These are described in Section 10.1 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We tried to locate protocols of included randomised trials. If the protocol was available, we compared outcomes in the protocol and in the published report. If the protocol was not available, we compared outcomes listed in the methods section of the trial report with actually reported results.

2. Funnel plot

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Egger 1997). These are described in Section 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small‐study effects. We did not use funnel plots for outcomes because we included one study.

Data synthesis

We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed‐effect or random‐effects models. The random‐effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. This often seems to be true to us and the random‐effects model takes into account differences between studies even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. However, there is a disadvantage to the random‐effects model. It puts added weight onto small studies, which often are the most biased ones. Depending on the direction of effect, these studies can either inflate or deflate the effect size. We chose a fixed‐effect model for all analyses.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

1. Subgroup analyses

We did not anticipate any subgroup analyses.

2. Investigation of heterogeneity

If inconsistency had been high, we would have reported it. First, we would have investigated whether data were entered correctly. Second, if data were correct, we would have visually inspected the graph and successively removed studies outside of the company of the rest to see if homogeneity was restored. For this review, we decided that should this occur with data contributing to the summary finding of no more than around 10% of the total weighting, we would have presented the data. If not, data would not be pooled and issues would be discussed. We know of no supporting research for this 10% cut‐off but are investigating use of prediction intervals as an alternative to this unsatisfactory state.

If unanticipated clinical or methodological heterogeneity were obvious, we would have simply stated hypotheses regarding these for future reviews or versions of this review. We did not anticipate undertaking analyses relating to these.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not undertake a sensitivity analysis as there was only one included trial.

Results

Description of studies

For substantive descriptions of studies, see Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies, and Characteristics of studies awaiting classification tables.

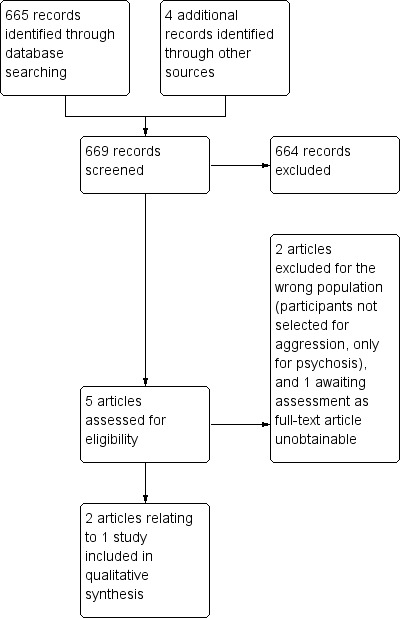

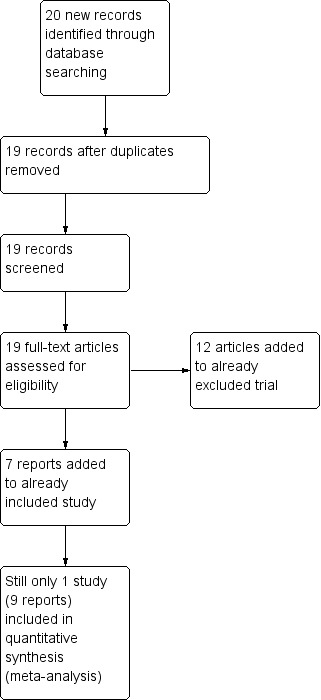

Results of the search

The search (July 2011) yielded 665 references of potentially eligible studies plus four additional references identified through other sources, of which we obtained five for second assessment. We excluded two papers for not meeting the inclusion criteria (due to wrong population) and one that awaits assessment as the full text is not obtainable (Lewis 2006). Finally, we included one study (two reports) in the present review (Krakowski 2006; Figure 2). The update search of April 2015 yielded no new studies but 19 more reports of the trials we had already identified (Figure 3).

2.

Study flow diagram.

3.

Study flow diagram (pre‐submission search of 1 April 2015).

Included studies

The Characteristics of included studies table provided details of the study that met the inclusion criteria (Krakowski 2006).

1. Length of study

The duration of the study was 12 weeks.

2. Participants

2.1 Clinical state

Participants were "physically assaultive" inpatients in state psychiatric facilities required to have "a clearly confirmed episode of physical assault directed at another person" and "some persistence of aggression, as evidenced by the presence of some other aggressive event, whether physical or verbal or against property."

2.2 Diagnosis

Participants were diagnosed with "schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (using diagnostic criteria form the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition)."

2.3 Exclusions

Exclusion criteria included people with a history of non‐response or intolerance to interventions, people with medical conditions adversely affected by interventions, people who received a depot antipsychotic drug within 30 days before randomisation, and people hospitalised for over one year.

2.4 Age

Participants ranged from 18 to 60 years.

3. Study size

The study initially randomised 110 participants; 70 participants completed the study.

4. Interventions

The study compared haloperidol with olanzapine and clozapine.

4.1 Dosing

4.1.1 Haloperidol: first six weeks, target endpoint 20 mg/day (mean dose 19.6 mg/day); last six weeks, range 10 mg/day to 30 mg/day (mean dose 23.3 mg/day). 4.1.2 Olanzapine: first six weeks, target endpoint 20 mg/day (mean dose 19.8 mg/day); last six weeks, range 10 mg/day to 35 mg/day (mean dose 24.7 mg/day). 4.1.3 Clozapine: first six weeks, target endpoint 500 mg/day (mean dose 457.1 mg/day); last six weeks, range 200 mg/day to 800 mg/day (mean dose 565.5 mg/day).

5. Leaving the study early

Sixteen people allocated to haloperidol discontinued the study, mainly due to clinical deterioration (n=7), but also due to adverse effects (n=4), withdrawn consent (n=4), or other reasons (n=1). Eleven people allocated to olanzapine discontinued the study, due to withdrawn consent (n=4), clinical deterioration (n=2), adverse effects (n=1) or other reasons (n=4). Thirteen people allocated to clozapine discontinued the study, mainly due to withdrawn consent (n=6), but also due to adverse effects (n=3), clinical deterioration (n=2) or other reasons (n=2).

6. Outcomes

We were able to use the outcome 'leaving the study early'.

6.1 Symptom scales

The study used the Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS) and PANSS to assess treatment effects; however, data from these scales were skewed.

a. Aggression: Modified Overt Aggression Scale (Kay 1986)

The MOAS uses three categories of external aggression, that is, physical aggression against other people, verbal aggression and physical aggression against objects. The score for each type of incident represents the number of incidents over time as well as their severity. The overall score assigns different weightings to each category of aggression, thus represents the number of incidents over time, their severity and the type of aggression (a high score is poor).

b. Mental state: PANSS (Kay 1986)

The PANSS contains three subscales; positive, negative and a general psychopathology subscale. The study used change in score rather than endpoint scores, so a positive score is an improvement in clinical symptoms.

Excluded studies

Two studies did not meet all the inclusion criteria (Volavka 2002, 24 reports; Singh 1981, one report). We had to exclude these because it was clear that participants had not been specifically selected for persistence of aggression as well as psychotic illness, rather they were people with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder on whom hostility and aggression was being measured.

1. Awaiting classification

One study is awaiting classification as it is a conference proceeding. This did not report the full characteristics or all the outcome data necessary (Lewis 2006, 1 report). We will search for a full‐text publication of this study at the next review update but admit that it may never be published since the abstract was published in 2006.

2. Ongoing

We identified no ongoing studies.

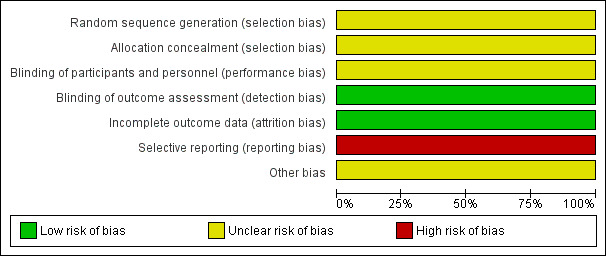

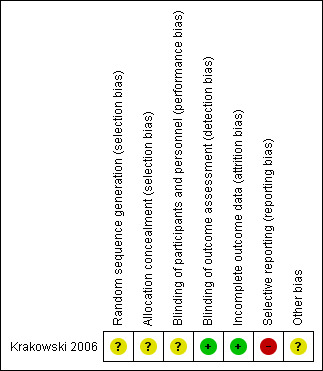

Risk of bias in included studies

Overall, we judged the risk of bias for the included study to be unclear. It is possible that the study slightly overestimated any true positive effects and slightly underestimated any true negative effects (see Figure 4; Figure 5).

4.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

5.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

The method of randomisation was not explicit (other than stating block randomisation) and there was no further information on how randomisation and allocation concealment were undertaken. We rated selection bias as unclear.

Blinding

The study was conducted under double‐blind conditions but no details were given of how the blinding was ensured. It was stated that raters who performed all the clinical assessment were blind to treatment group. We rated performance and detection bias as unclear.

Incomplete outcome data

There was a low risk of bias as the study clearly reported attrition data in a table and performed an intention‐to‐treat analysis.

Selective reporting

The study did not report data on adverse effects or numerical data for the additional medications used to control adverse effects. We rated this to be a high risk of bias.

Other potential sources of bias

Eli Lilly and Company provided supplemental funding for "encapsulation of the medications", but the authors stressed that "the overall experimental design, data acquisition, statistical analyses, and interpretation of the results were implemented with no input from any of the pharmaceutical companies". Overall, we rated the risk to be unclear.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

We categorised data from the one study (n=110) into three comparisons (Krakowski 2006, 12 reports).

1. Comparison 1: haloperidol versus olanzapine

There were two outcomes for haloperidol versus olanzapine.

1.1 Aggression: average scores (MOAS, high=poor, data skewed)

These continuous data had such large SDs as to suggest that analysis within Review Manager 5 would be inadvisable. Therefore, we presented them in a data table (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 HALOPERIDOL versus OLANZAPINE, Outcome 1 Aggression: average scores (Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS), high=poor, data skewed).

| Aggression: average scores (Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS), high=poor, data skewed) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Intervention | Mean | SD | N |

| total | ||||

| Krakowski 2006 | Haloperidol | 40.9 | 68.88 | 36 |

| Krakowski 2006 | Olanzapine | 32.7 | 69.83 | 37 |

| aggression ‐ physical | ||||

| Krakowski 2006 | Haloperidol | 20.7 | 30.61 | 36 |

| Krakowski 2006 | Olanzapine | 14.1 | 31.03 | 37 |

| aggression ‐ against property | ||||

| Krakowski 2006 | Haloperidol | 4.7 | 9.18 | 36 |

| Krakowski 2006 | Olanzapine | 2.7 | 6.21 | 37 |

| aggression ‐ verbal | ||||

| Krakowski 2006 | Haloperidol | 15.6 | 35.20 | 36 |

| Krakowski 2006 | Olanzapine | 16.0 | 29.48 | 37 |

1.2 Mental state: average change score (PANSS, positive=improvement, data skewed)

These continuous data had such large SDs as to suggest that analysis within Review Manager 5 would be inadvisable. Therefore, we presented them in a data table (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 HALOPERIDOL versus OLANZAPINE, Outcome 2 Mental state: average change score (Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), positive=improvement, data skewed).

| Mental state: average change score (Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), positive=improvement, data skewed) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Intervention | Mean | SD | N |

| general psychopathology | ||||

| Krakowski 2006 | Haloperidol | 0.64 | 8.2 | 36 |

| Krakowski 2006 | Olanzapine | 2.69 | 5.5 | 37 |

| negative symptoms | ||||

| Krakowski 2006 | Haloperidol | 0.44 | 4.6 | 36 |

| Krakowski 2006 | Olanzapine | 0.72 | 3.0 | 37 |

| positive symptoms | ||||

| Krakowski 2006 | Haloperidol | ‐0.5 | 5.3 | 36 |

| Krakowski 2006 | Olanzapine | 1.41 | 3.6 | 37 |

| total | ||||

| Krakowski 2006 | Haloperidol | 0.58 | 1.52 | 36 |

| Krakowski 2006 | Olanzapine | 4.83 | 9.7 | 37 |

2. Comparison 2: haloperidol haloperidol versus clozapine

There were two outcomes for haloperidol versus clozapine.

2.1 Aggression: average scores (MOAS, high=poor, data skewed)

These continuous data (one RCT) had such large SDs as to suggest that analysis within Review Manager 5 would be inadvisable. We presented data in a data table (Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 HALOPERIDOL versus CLOZAPINE, Outcome 1 Aggression: average scores (Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS), high=poor, data skewed).

| Aggression: average scores (Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS), high=poor, data skewed) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Intervention | Mean | SD | N |

| total | ||||

| Krakowski 2006 | Haloperdiol | 40.9 | 68.88 | 36 |

| Krakowski 2006 | Clozapine | 25.1 | 43.45 | 37 |

| aggression ‐ physical | ||||

| Krakowski 2006 | Haloperdiol | 20.7 | 30.61 | 36 |

| Krakowski 2006 | Clozapine | 10.3 | 24.83 | 37 |

| aggression ‐ against property | ||||

| Krakowski 2006 | Haloperdiol | 4.7 | 9.18 | 36 |

| Krakowski 2006 | Clozapine | 2.6 | 3.10 | 37 |

| aggression ‐ verbal | ||||

| Krakowski 2006 | Haloperdiol | 15.6 | 35.20 | 36 |

| Krakowski 2006 | Clozapine | 12.2 | 37 | |

2.2 Mental state: average change score (PANSS, positive=improvement, data skewed)

These continuous data were from one small study and were very skewed. We presented them in a data table (Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 HALOPERIDOL versus CLOZAPINE, Outcome 2 Mental state: average change score (Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), positive=improvement, data skewed).

| Mental state: average change score (Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), positive=improvement, data skewed) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Intervention | Mean | SD | N |

| general psychopathology | ||||

| Krakowski 2006 | Haloperidol | 0.64 | 8.2 | 36 |

| Krakowski 2006 | Clozapine | 1.43 | 37 | |

| negative symptoms | ||||

| Krakowski 2006 | Haloperidol | 0.44 | 4.6 | 36 |

| Krakowski 2006 | Clozapine | ‐0.56 | 4.9 | 37 |

| positive symptoms | ||||

| Krakowski 2006 | Haloperidol | ‐0.5 | 5.3 | 36 |

| Krakowski 2006 | Clozapine | 1.54 | 5.0 | 37 |

| total | ||||

| Krakowski 2006 | Haloperidol | 0.58 | 1.52 | 36 |

| Krakowski 2006 | Clozapine | 2.39 | 14.2 | 37 |

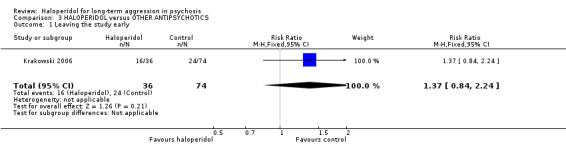

3. Comparison 3: haloperidolhaloperidol versus other antipsychotic drugs

There was one outcome for haloperidol versus other antipsychotic drug.

3.1 Leaving the study early

We found no evidence of a clear difference between haloperidol and other antipsychotic drugs for leaving the study early (1 RCT, n=110, RR 1.37, 95% CI 0.84 to 2.24, Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 HALOPERIDOL versus OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 1 Leaving the study early.

4. Missing outcomes

Although the study provided data for some outcomes, there were no data on most of the binary outcomes and none on service outcomes (use of hospital/police), satisfaction with treatment, acceptance of treatment, quality of life or economic outcomes.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review compared haloperidol versus any other intervention for people with psychosis exhibiting long‐term aggression/agitation. There were only limited data available and these are summarised in Table 1.

1. Aggression ‐ important decrease in aggression

We identified no trials reporting an important decrease in aggression. For the comparison of haloperidol versus olanzapine or clozapine, one small trial provided continuous but skewed data that was at high risk of bias suggesting some advantage in terms of scores of unclear clinical meaning for olanzapine/clozapine for 'total aggression' (Krakowski 2006). We do recognise the very great problems undertaking trials with this participant group. This review, its included study and at least one other (Lewis 2006) illustrate that randomisation is possible. This group of people is sufficiently prevalent, and this or other interventions used frequently enough, to merit investment of time and effort in evaluation of possible means of treatment.

2. Repeated need for tranquillisation

We identified no trials reporting repeated need for tranquillisation.

3. Specific behaviours ‐ threat or injury to others/self

We identified no trials reporting threat or injury to others/self. For the comparison of haloperidol versus olanzapine or clozapine, one small trial provided skewed data at high risk of bias suggesting some advantage in terms of scores of unclear clinical meaning for olanzapine/clozapine for 'aggression against property' and 'aggression ‐ physical' (Krakowski 2006). Verbal aggression was not changed. Data were limited making drawing of conclusions ill‐advised.

4. Adverse effects ‐ any serious, specific adverse effects

We identified no trials reporting any serious, specific adverse effects.

5. Global outcomes ‐ overall improvement

We identified no trials reporting overall improvement. For the comparison haloperidol versus olanzapine or clozapine, one small trial provided skewed data at high risk of bias suggesting some advantage in terms of scores of unclear clinical meaning for olanzapine/clozapine for a series of mental state ratings (Krakowski 2006). These outcomes were as close as we could find for 'global state' and were not informative.

6. Economic outcomes

We identified no trials reporting economic outcomes.

7. Leaving the study early

The Krakowski 2006 study (total n=110) reported leaving the study early and there was no clear evidence of a difference between haloperidol and other antipsychotic drugs (about 50% versus about 33%, RR 1.37, CI 0.84 to 2.24, Analysis 3.1). Recognising that this was a small study, there was no evidence that, across three months, haloperidol was clearly less well tolerated than the other more modern drugs. Although attrition was high, most people in both groups continued on their allocated drugs ‐ and, with this difficult group of people, this could be seen as important.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

1. Completeness

The study reported method and data mostly with clarity, enabling extraction of fairly reliable information. However, this study did not address all the outcomes specified for the review and the sample size was small. Initially it seemed that the Krakowski 2001 report of Krakowski 2006 estimated that 210 people were to be randomised but this seems to have proceeded to the smaller Krakowski 2006 report (n=110). The Krakowski 2006 report did not have aggression measured by the Buss Durkee Hostility scale or the Nurses' Observation Scale for In‐patient Evaluation (NOSIE), neither did it report mental state using Clinical Global Impression, Barratt Impulsivity Scale (trait impulsivity) or Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (cognitive) as had been listed in the Krakowski 2001 report. This does suggest that there was selective reporting in the Krakowski 2006 trial.

2. Applicability

The included study was highly relevant to the review question ‐ the participants, interventions and outcomes were directly comparable to the objectives of the review (Krakowski 2006). One study awaiting classification investigated haloperidol versus risperidone for aggression in male inmates with psychosis, using the MOAS and Barratt Impulsivity Scale, but could not be used in this review because the conference proceeding reported no data and we have not identified a full paper (Lewis 2006). The study was small (n=40) and specific to a certain population (prison inmates), so it might not be possible to generalise the findings to other populations. However, such a trial shows that more evidence is potentially there to incorporate into the questions asked by this review.

Quality of the evidence

Data were limited, low quality and difficult to interpret (Table 1).

Potential biases in the review process

We are not aware of any biases in the review process. It is possible that we did not identify small studies due to a degree of publishing bias (Egger 1997), but we consider that we have identified all larger relevant studies.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We know of no other systematic reviews for the use of haloperidol for treating long‐term aggression in people with psychosis.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

1. For people with psychosis and aggression

We have no evidence on the absolute effectiveness of haloperidol for longer‐term aggression. It may be of use if no other antipsychotic drugs are available. However, it has a considerable adverse effect profile (Adams 2013). We currently do not know if use of haloperidol for longer‐term aggression is any more or less effective than other drugs but this review provides some very limited evidence that olanzapine and clozapine may be at least as good, and it may be that some people find these more acceptable than haloperidol.

2. For clinicians

Aggressive behaviour could be the result of psychosis, independent of it, or even the consequences of treatments. People with chronic aggression are difficult to manage but antipsychotic medication is likely to remain one possible treatment approach. Evidence that trials are possible is strong. Evidence from within trials is currently almost without clinical value. Clinicians are left having to rely on evidence coming from other less applicable studies or studies of lesser rigour, or clinical experience.

3. For policymakers

From the evidence presented in the review, firm conclusions cannot be drawn for the use of haloperidol for persistently aggressive people with psychosis. Policymakers could help clinicians, researchers and recipients of care address this shortfall.

Implications for research.

1. General

1.1 Better reporting

The included study does not predate CONSORT (Begg 1996; Moher 2001). Clear and strict adherence to the CONSORT statement may well have resulted in clarifying more data from Krakowski 2006. Using specific trial identifiers such as International RCT Number (ISRCTN) across multiple publications would greatly reduce confusion over identification of the source trial.

1.2 Public accessibly of trial data

The review authors are in the invidious position of now knowing that data are probably not available to help clarify issues. However, full availability of all data from each study, including the one awaiting assessment (Lewis 2006), might have allowed us to say that data are too few with more confidence. Participants in Lewis 2006 did not give informed consent to have their data squandered.

2. Specific ‐ trials

More randomised controlled trials need to be conducted investigating haloperidol specifically for persistently aggressive people with psychosis. The trials should report aggression, mental state and leaving the study early outcomes, but also more detailed data on adverse effects, quality of life and economic costs as these are highly important to patients and clinicians managing their treatment. The trials should be reported in detail, as described by the CONSORT statement (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials, CONSORT). We do realise that design of such studies is difficult and needs most careful consideration. However, we have given this some thought and suggest an outline design in Table 3.

2. Suggested design for a randomised trial.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised, clearly described. Blinding: double, described and tested. Duration: 52 weeks. |

| Participants | Diagnosis: have psychoses. N=300*. Age: any. Sex: both. History: persistently aggressive. |

| Interventions | 1. Haloperidol: dose flexible within recommended limits. N=150. 2. Other antipsychotic drug: dose flexible within recommended limits. N=150. |

| Outcomes | Outcomes grouped into short term (3 months or less), medium term (> 3 and up to 6 months or less) and long‐term (> 6 months). Aggression: events. Adverse effects. Specific behaviours ‐ self harm including suicide, injury to others, aggression. Global outcomes ‐ overall improvement, use of additional medication, use of restraints/seclusion. Service outcomes ‐ duration of hospital stay, re‐admission. Mental state ‐ no clinically important change in general mental state. Leaving the study early ‐ why. Satisfaction with and acceptance of treatment. Quality of life ‐ no clinically important change in quality of life. Economic outcomes. |

| Notes | * Powered to be able to identify a difference of ˜ 20% between groups for primary outcomes with adequate degree of certainty. |

N: number of participants.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group editorial base, Nottingham, UK, for all their help and patience.

The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Editorial Base in Nottingham produces and maintains standard text for use in the Methods section of their reviews. We have used this text as the basis of what appears here and adapted it as required.

Parts of this review were generated using RevMan HAL version 4.2 (for further information see CSzG Website)

We would also like to thank and acknowledge Salwan Jajawi for peer reviewing this version of the review.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. HALOPERIDOL versus OLANZAPINE.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Aggression: average scores (Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS), high=poor, data skewed) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 1.1 total | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 1.2 aggression ‐ physical | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 1.3 aggression ‐ against property | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 1.4 aggression ‐ verbal | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 2 Mental state: average change score (Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), positive=improvement, data skewed) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 2.1 general psychopathology | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 2.2 negative symptoms | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 2.3 positive symptoms | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 2.4 total | Other data | No numeric data |

Comparison 2. HALOPERIDOL versus CLOZAPINE.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Aggression: average scores (Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS), high=poor, data skewed) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 1.1 total | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 1.2 aggression ‐ physical | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 1.3 aggression ‐ against property | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 1.4 aggression ‐ verbal | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 2 Mental state: average change score (Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), positive=improvement, data skewed) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 2.1 general psychopathology | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 2.2 negative symptoms | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 2.3 positive symptoms | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 2.4 total | Other data | No numeric data |

Comparison 3. HALOPERIDOL versus OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTICS.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Leaving the study early | 1 | 110 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.37 [0.84, 2.24] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Krakowski 2006.

| Methods | Allocation: random; block randomisation with no baseline stratification; parallel group. Blinding: double‐blind. Duration: 1 to 2 weeks' pre‐trial baseline screening; 12 weeks' trial ‐ 6 weeks' escalation and fixed dose, 6 weeks' variable dose. |

|

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder (DSM‐IV). N=110. Age: 18 to 60 years. History: psychiatric inpatient at 1 of 2 New York state hospitals, hospitalised within the last year. Inclusion: clearly confirmed episode of physical assault during this hospitalisation, some persistence of aggression i.e. evidence of other aggressive event (physical or verbal or against property). Exclusion: people hospitalised for over 1 year; history of non‐response or intolerance to interventions; people with medical conditions adversely affected by interventions; people who received a depot antipsychotic drug within 30 days before randomisation. |

|

| Interventions | 1. Haloperidol: first 6 weeks, target endpoint 20 mg/day, mean dose 19.6 mg/day; last 6 weeks, range 10 mg/day to 30 mg/day, mean dose 23.3 mg/day. N=36. 2. Olanzapine: first 6 weeks, target endpoint 20 mg/day, mean dose 19.8 mg/day; last 6 weeks, range 10 mg/day to 35 mg/day, mean dose 24.7 mg/day. N=37. 3. Clozapine: first 6 weeks, target endpoint 500 mg/day, mean dose 457.1 mg/day; last 6 weeks, range 200 mg/day to 800 mg/day, mean dose 565.5 mg/day. N=37. |

|

| Outcomes | Leaving study early. Unable to use ‐ Aggression: MOAS (skewed data), subgroup: MOAS (randomisation status unclear). Mental state: PANSS (skewed data). Adverse effects: ESRS and checklist (no data reported). |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "Block randomisation" ‐ no further details. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not stated. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | "Double blind" but no description of how blinding was ensured. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Raters, blind to treatment group, performed all clinical assessments. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Study attrition clearly reported ‐ table presented and intention‐to‐treat analysis performed. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Adverse effects data not fully reported; numerical data for additional medications not fully reported. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Supplemental funding from pharmaceuticals for "encapsulation of the medications". |

N: number of participants.

Rating scale abbreviations: ESRS: Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale; MOAS: Modified Overt Aggression Scale; PANSS: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

Diagnostic standards abbreviations: DSM‐IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition.

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Singh 1981 | Allocation: random implied but not stated. Participants: people considered to have schizophrenia, however not selected for persistently aggressive behaviour. |

| Volavka 2002 | Allocation: random. Participants: people with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder, however not selected for persistently aggressive behaviour, although aggression was an outcome of interest. |

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

Lewis 2006.

| Methods | Allocation: random. Blinding: unstated. Duration: 90 days. |

| Participants | Diagnosis: axis I psychotic disorders (DSM‐IV). N=40. Sex: men. Inclusion: inmates with serious mental illness at a mental health housing unit at Osborn Correctional Institute, Somers Connecticut. Exclusion: people on mood stabilisers. |

| Interventions | 1. Haloperidol: dose initiation 4 mg/day with weekly titration of 2 mg/day orally up to therapeutic maximum of 12 mg/day. N=20. 2. Risperidone: dose initiation 2 mg/day orally with weekly titration of 2 mg up to therapeutic maximum of 6 mg/day. N=20. |

| Outcomes | Aggression: OAS‐M administered weekly. Mental state (trait impulsivity): BIS at initiation and conclusion of study. |

| Notes | Conference proceeding, full characteristics and outcome data not reported. |

N: number of participants.

Rating scale abbreviations: BIS: Barratt Impulsivity Scale; CGI: Clinical Global Impression; MOAS/OAS‐M: Modified Overt Aggression Scale; NOSIE: Nurses' Observation Scale for Inpatient Evaluation; PANSS: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

Diagnostic standards abbreviations: DSM‐IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition.

Differences between protocol and review

We have added the outcome, repeated need for tranquillisation.

Contributions of authors

AK: took the lead in the review, wrote the protocol, screened and retrieved papers against eligibility criteria, appraised quality of papers, extracted data from papers, entered data into Review Manager 5 and analysed data, interpreted data and wrote the review.

MP: helped write the protocol and screened search results.

Sources of support

Internal sources

-

Watford General Hospital, UK.

Employs review author Abha Khushu ‐ Junior Doctor in Paediatrics

-

The University of Manchester, UK.

Supports review author Melanie Powney ‐ Trainee Clinical Psychologist

External sources

No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

AK: none known.

MP: none known.

New

References

References to studies included in this review

Krakowski 2006 {published data only}

- Krakowski M, Czobor P. A prospective longitudinal study of cholesterol and aggression in patients randomized to clozapine, olanzapine and haloperidol. 15th Biennial Winter Workshop in Psychoses; 2009 Nov 15‐18; Barcelona, Spain. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Krakowski M, Czobor P, Citrome L. Weight gain, metabolic parameters, and the impact of race in aggressive inpatients randomized to double‐blind clozapine, olanzapine or haloperidol. Schizophrenia Research 2009;110(1‐3):95‐102. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakowski MI. Clozapine and olanzapine in violent schizophrenics. CRISP database (www‐commons.cit.nih.gov/crisp/index.html) (accessed 19 February 2001).

- Krakowski MI, Czobor P. A prospective longitudinal study of cholesterol and aggression in patients randomized to clozapine, olanzapine, and haloperidol. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 2010;30(2):198‐200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakowski MI, Czobor P. Depression and impulsivity as pathways to violence: implications for antiaggressive treatment. Schizophrenia Bulletin 2014; Vol. 40, issue 4:886‐94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Krakowski MI, Czobor P. Executive function predicts response to antiaggression treatment in schizophrenia: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2012; Vol. 73, issue 1:74‐80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Krakowski MI, Czobor P. Neurocognitive impairment limits the response to treatment of aggression with antipsychotic agents. Schizophrenia Bulletin 2011; Vol. 37:311‐2.

- Krakowski MI, Czobor P, Citrome L, Bark N, Cooper TB. Atypical antipsychotic agents in the treatment of violent patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 2006;63(6):622‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakowski MI, Czobor P, Nolan KA. Atypical antipsychotics, neurocognitive deficits, and aggression in schizophrenic patients. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 2008;28(5):485‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Singh 1981 {published data only}

- Singh MM, Kay SR, Pitman RK. Aggression control and structuring of social relations among recently admitted schizophrenics. Psychiatry Research 1981;5(2):157‐69. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Volavka 2002 {published data only}

- Bilder RM, Goldman RS, Volavka J, Czobor P, Hoptman M, Sheitman B, et al. Neurocognitive effects of clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in patients with chronic schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 2002;159(6):1018‐28. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilder RM, Goldman RS, Volavka J, Czobor P, Hoptman M, Sheitman B, et al. Neurocognitive effects of clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol on treatment‐resistant patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. European Neuropsychopharmacology 2001;11(3):256. [Google Scholar]

- Bilder RM, Goldman RS, Volavka J, Czobor P, Hoptman M, Sheitman B, et al. Neurocognitive effects of clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol on treatment‐resistant patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Schizophrenia Research. Elsevier Science B.V, 2002; Vol. 53, issue 3 Suppl 1:194.

- Citrome L, Volavka J, Czobor P, Sheitman B, Lindenmayer JP, McEvoy J, et al. Effects of clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol on hostility among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 2001;52(11):1510‐4. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citrome LL, Volavka J, Czobor P, Nolan K, Lieberman JA, Lindenmayer JP, et al. Overt aggression and psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia treated with clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol. 156th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; 2003 May 17‐22; San Francisco (CA). 2003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Citrome LL, Volavka J, Czobor P, Sheitman BB, Lindenmayer JP, McEvoy JP, et al. Atypical antipsychotics and hostility in schizophrenia: a double‐blind study. 154th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; 2001 May 5‐10; New Orleans (LA). 2001.

- Citrome LL, Volavka J, Czobor P, Sheitman BB, Lindenmayer JP, McEvoy JP, et al. Atypical antipsychotics and hostility in schizophrenia: a double‐blind study. 155th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; 2002 May 18‐23; Philadelphia (PA). 2002.

- Czobor P, Volavka J, Sheitman B, Lindenmayer JP, Citrome L, McEnvoy J, et al. Antipsychotic‐induced weight gain and therapeutic response: a differential association. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 2002; Vol. 22, issue 3:244‐51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hoptman MJ, Volavka J, Czobor P, Gerig G, Chakos M, Blocher J, et al. Aggression and quantitative MRI measures of caudate in patients with chronic schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 2006;18(4):509‐15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenmayer JP, Czobor P, Volavka J, Citrome L, Sheitman B, McEvoy J, et al. Changes in glucose and cholesterol levels in schizophrenia patients treated with typical and atypical antipsychotics. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 2002;5(Suppl 1):S169. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenmayer JP, Czobor P, Volavka J, Citrome L, Sheitman B, McEvoy JP, et al. Changes in glucose and cholesterol levels in patients with schizophrenia treated with typical or atypical antipsychotics. American Journal of Psychiatry 2003;160(2):290‐6. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenmayer JP, Czobor P, Volavka J, Citrome LL, Sheitman BB, McEvoy JP, et al. Changes in glucose and cholesterol in schizophrenia treated with atypicals. 155th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; 2002 May 18‐23; Philadelphia (PA). 2002.

- Lindenmayer JP, Czobor P, Volavka J, Lieberman JA, Citrome L, Sheitman B, et al. Effects of atypical antipsychotics on the syndromal profile in treatment‐resistant schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2004;65(4):551‐6. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenmayer JP, Czobor P, Volavka J, Lieberman JA, Citrome LL, Sheitman BB, et al. Effects of atypicals on the syndromal profile in treatment‐resistant schizophrenia. 156th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; 2003 May 17‐22; San Francisco (CA). 2003.

- Lindenmayer JP, Czobor P, Yolayka J, Lieberman JA, McEvoy JP, Citrome LL, et al. Do atypicals change the syndrome profile in treatment‐resistant schizophrenia?. 154th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; 2001 May 5‐10; New Orleans (LA). Marathon Multimedia, 2001.

- Lindenmayer JP, Volavka J, Lieberman JA, Citrome LL, Sheitman B, McEvoy JP, et al. Do atypicals change the syndromal profile in treatment‐resistant schizophrenia?. 155th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; 2002 May 18‐23; Philadelphia (PA). 2002.

- Mohr P, Volavka J, Lieberman JA, Czobor P, McEnvoy J, Lindenmayer JP, et al. Clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in refractory schizophrenia. European Psychiatry 2000;15(Suppl 2):284S. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan KA, Volavka J, Czobor P, Sheitman B, Lindenmayer JP, Citrome LL, et al. Aggression and psychopathology in treatment‐resistant inpatients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2005;39(1):109‐15. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volavka J, Czobor P, Cooper TB, Sheitman B, Lindenmayer JP, Citrome L, et al. Prolactin levels in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder patients treated with clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2004;65(1):57‐61. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volavka J, Czobor P, Nolan K, Sheitman B, Lindenmayer JP, Citrome L, et al. Overt aggression and psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia treated with clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 2004;24(2):225‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volavka J, Czobor P, Sheitman B, Lindenmayer JP, Citrome L, McEvoy J, et al. Clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in refractory schizophrenia. 39th Annual Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; 2000 Dec 10‐14; San Juan, Puerto Rico. 2000.

- Volavka J, Czobor P, Sheitman B, Lindenmayer JP, Citrome L, McEvoy JP, et al. "Clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in the treatment of patients with chronic schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder": erratum. American Journal of Psychiatry 2002;159(12):2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volavka J, Czobor P, Sheitman B, Lindenmayer JP, Citrome L, McEvoy JP, et al. Clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in the treatment of patients with chronic schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 2002;159(2):255‐62. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volavka J, Nolan KA, Kline L, Czobor P, Citrome L, Sheitman B, et al. Efficacy of clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder assessed with Nurses Observation Scale for inpatient evaluation. Schizophrenia Research 2005;76(1):127‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies awaiting assessment

Lewis 2006 {published data only}

- Lewis CF. Haloperidol versus risperidone in the treatment of aggressive psychotic male inmates. 159th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; 2006 May 20‐25; Toronto, Canada. 2006.

Additional references

Adams 2013

- Adams CE, Bergman H, Irving CB, Lawrie S. Haloperidol versus placebo for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 11. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003082.pub3; CD003082] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ahmed 2010

- Ahmed U, Jones H, Adams CE. Chlorpromazine for psychosis induced aggression or agitation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007445.pub2; PUBMED: 20393959] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Altman 1996

- Altman DG, Bland JM. Detecting skewness from summary information. BMJ 1996;313(7066):1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

APA 2004

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. www.psychiatryonline.com/content.aspx?aID=45971 (accessed 3 June 2011).

Begg 1996