Abstract

Background

Allergy is common and may be associated with foods, including cow's milk formula (CMF). Formulas containing hydrolysed proteins have been used to treat infants with allergy. However, it is unclear whether hydrolysed formulas can be advocated for prevention of allergy in infants.

Objectives

To compare effects on allergy and food allergy when infants are fed a hydrolysed formula versus CMF or human breast milk. If hydrolysed formulas are effective, to determine what type of hydrolysed formula is most effective, including extensively or partially hydrolysed formula (EHF/PHF). To determine which infants at low or high risk of allergy and which infants receiving early, short‐term or prolonged formula feeding may benefit from hydrolysed formulas.

Search methods

We used the standard search strategy of the Cochrane Neonatal Review Group supplemented by cross referencing of previous reviews and publications (updated August 2016).

Selection criteria

We searched for randomised and quasi‐randomised trials that compared use of a hydrolysed formula versus human milk or CMF. Trials with ≥ 80% follow‐up of participants were eligible for inclusion.

Data collection and analysis

We independently assessed eligibility of studies for inclusion, methodological quality and data extraction. Primary outcomes included clinical allergy, specific allergy and food allergy. We conducted meta‐analysis using a fixed‐effect (FE) model.

Main results

Two studies assessed the effect of three to four days' infant supplementation with an EHF whilst in hospital after birth versus pasteurised human milk feed. Results showed no difference in infant allergy or childhood cow's milk allergy (CMA). No eligible trials compared prolonged hydrolysed formula versus human milk feeding.

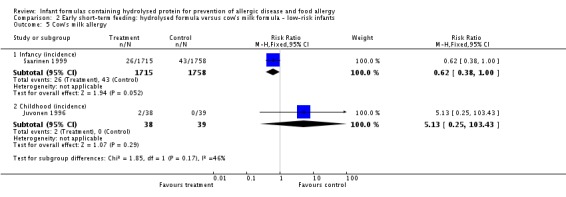

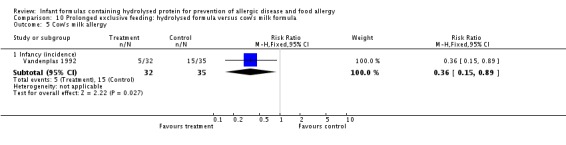

Two studies assessed the effect of three to four days' infant supplementation with an EHF versus a CMF. One large quasi‐random study reported a reduction in infant CMA of borderline significance among low‐risk infants (risk ratio (RR) 0.62, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.38 to 1.00).

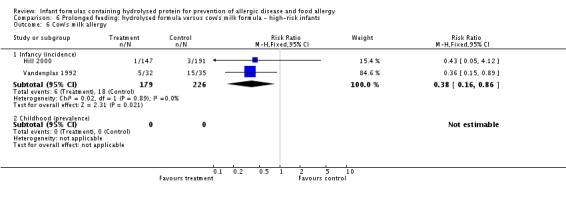

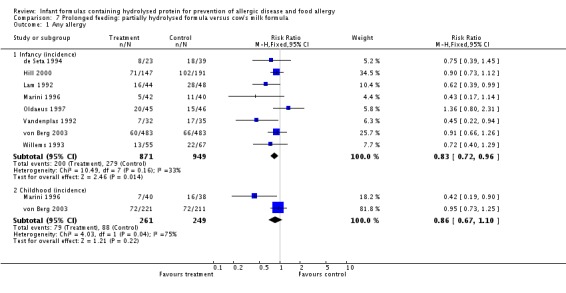

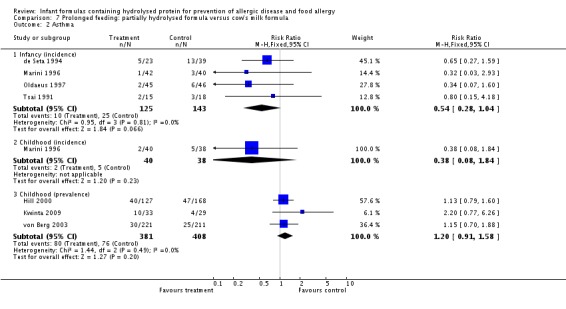

Prolonged infant feeding with a hydrolysed formula compared with a CMF was associated with a reduction in infant allergy (eight studies, 2852 infants; FE RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.95; risk difference (RD) ‐0.04, 95% CI ‐0.08 to ‐0.01; number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) 25, 95% CI 12.5 to 100) and infant CMA (two studies, 405 infants; FE RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.86). We had substantial methodological concerns regarding studies and concerns regarding publication bias, as substantial numbers of studies including those in high‐risk infants have not comprehensively reported allergy outcomes (GRADE quality of evidence 'very low').

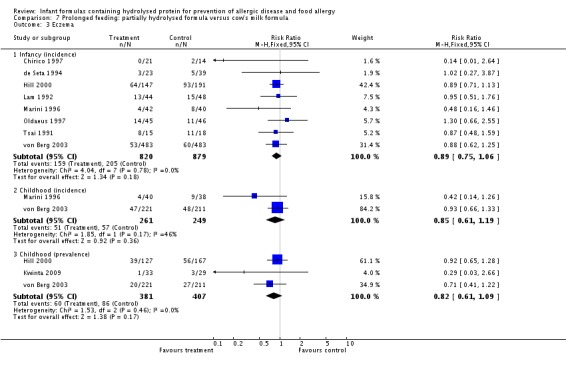

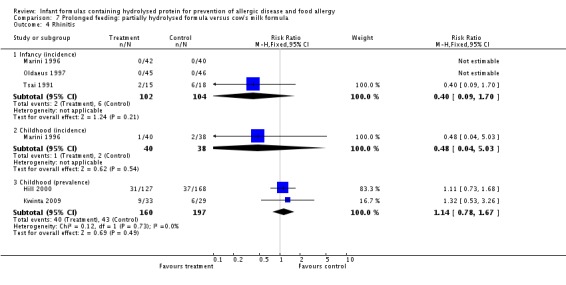

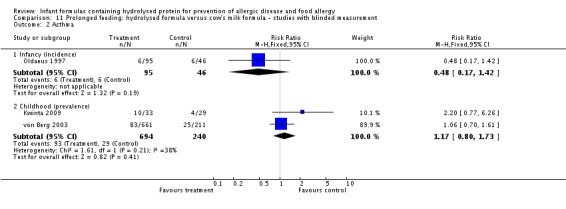

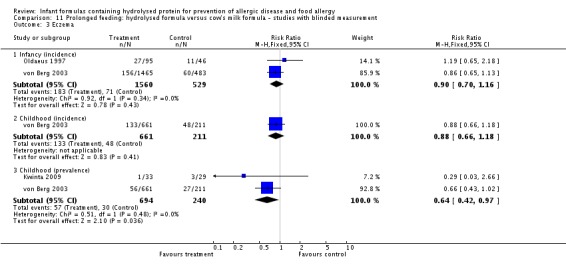

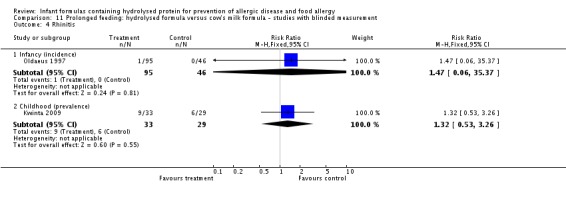

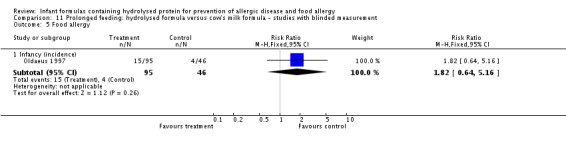

Prolonged infant feeding with a hydrolysed formula compared with a CMF was not associated with a difference in childhood allergy and led to no differences in specific allergy, including infant and childhood asthma, eczema and rhinitis and infant food allergy. Many of the analyses assessing specific allergy are underpowered.

Subroup analyses showed that infant allergy was reduced in studies that enrolled infants at high risk of allergy who used a hydrolysed formula compared with a CMF; used a PHF compared with a CMF; used prolonged and exclusive feeding of a hydrolysed formula compared with a CMF; and used a partially hydrolysed whey formula compared with a CMF. Studies that enrolled infants at high risk of allergy; used a PHF compared with a CMF; used prolonged and exclusive feeding of a hydrolysed formula compared with a CMF; and used a partially hydrolysed whey formula compared with a CMF found a reduction in infant CMA.

Authors' conclusions

We found no evidence to support short‐term or prolonged feeding with a hydrolysed formula compared with exclusive breast feeding for prevention of allergy. Very low‐quality evidence indicates that short‐term use of an EHF compared with a CMF may prevent infant CMA.

In infants at high risk of allergy not exclusively breast fed, very low‐quality evidence suggests that prolonged hydrolysed formula feeding compared with CMF feeding reduces infant allergy and infant CMA. Studies have found no difference in childhood allergy and no difference in specific allergy, including infant and childhood asthma, eczema and rhinitis and infant food allergy.

Very low‐quality evidence shows that prolonged use of a partially hydrolysed formula compared with a CMF for partial or exclusive feeding was associated with a reduction in infant allergy incidence and CMA incidence, and that prolonged use of an EHF versus a PHF reduces infant food allergy.

Keywords: Humans; Infant; Infant, Newborn; Dietary Proteins; Food Hypersensitivity; Food Hypersensitivity/prevention & control; Hydrolysis; Infant Formula; Infant Formula/chemistry; Milk Hypersensitivity; Milk Hypersensitivity/prevention & control; Milk, Human; Protein Hydrolysates; Protein Hydrolysates/administration & dosage; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Synapsins

Formulas containing hydrolysed protein for prevention of allergy and food allergy in infants

Review question

Does feeding infants with a formula containing hydrolysed protein result in decreased risk of developing allergy such as asthma, dermatitis/eczema, hay fever and food allergy during infancy and childhood?

Background

Allergy is responsible for a substantial health burden among infants, children and adults. Early dietary intake may influence the development of allergic disease. When babies are not exclusively breast fed, use of hydrolysed formula instead of ordinary cow's milk formula may reduce allergy among babies and children, although additional studies are needed to confirm this. Infant formulas have been designed to lower the chance of infants developing allergy or food allergy. These include hydrolysed cow's milk and soy milk formulas. Hydrolysed formulas break down milk proteins into smaller, potentially less allergy‐producing proteins.

Results

This review of trials found no evidence to support feeding with a hydrolysed formula to prevent allergy in preference to exclusive breast feeding. For infants at high risk of allergy who are unable to be completely breast fed, limited evidence indicates that feeding with a hydrolysed formula compared with a cow's milk formula reduces allergy among babies and children, including cow's milk allergy (CMA). Concerns regarding quality of the evidence and consistency of the results indicate that continued study is needed.

Conclusions

Among infants at high risk of allergy who cannot be exclusively breast fed, very low‐quality evidence suggests that prolonged supplementation with a hydrolysed formula compared with a cow's milk formula reduces the risk of infant allergy and infant CMA. However, further research is needed to confirm these findings.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison.

Early short‐term feeding: hydrolysed formula versus human milk feeding ‐ low‐risk infants for prevention of allergic disease and food allergy

| Early short‐term feeding of hydrolysed formula versus human milk for prevention of allergic disease and food allergy | ||||||

| Patient or population: infants not selected for allergy risk Settings: hospitals Intervention: early short‐term feeding: hydrolysed formula versus human milk feeding for prevention of allergic disease and food allergy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Early short‐term feeding: hydrolysed formula vs human milk ‐ low‐risk infants | |||||

| Any allergy ‐ childhood (incidence) Follow‐up: mean 3 years | Study population | RR 1.43 (0.38 to 5.37) | 90 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c | ||

| 75 per 1000 | 108 per 1000 (29 to 405) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 76 per 1000 | 109 per 1000 (29 to 408) | |||||

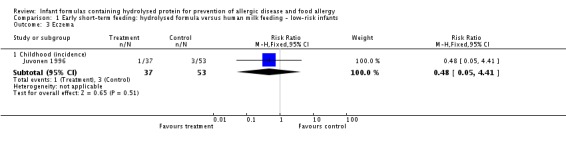

| Asthma ‐ childhood (incidence) Follow‐up: mean 3 years | Study population | RR 0.48 (0.05 to 4.41) | 90 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c | ||

| 57 per 1000 | 27 per 1000 (3 to 250) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 57 per 1000 | 27 per 1000 (3 to 251) | |||||

| Eczema ‐ childhood (incidence) Follow‐up: mean 3 years | Study population | RR 0.48 (0.05 to 4.41) | 90 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c | ||

| 57 per 1000 | 27 per 1000 (3 to 250) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 57 per 1000 | 27 per 1000 (3 to 251) | |||||

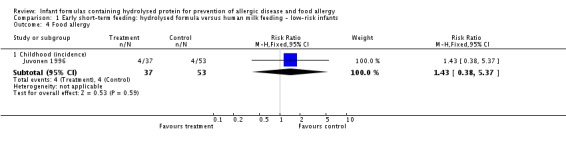

| Food allergy ‐ childhood (incidence) Follow‐up: mean 3 years | Study population | RR 1.43 (0.38 to 5.37) | 90 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c | ||

| 75 per 1000 | 108 per 1000 (29 to 405) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 76 per 1000 | 109 per 1000 (29 to 408) | |||||

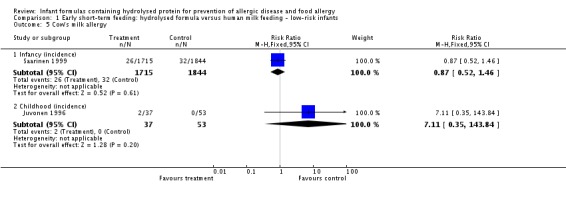

| Cow's milk allergy ‐ infancy (incidence) Follow‐up: mean 27 months | Study population | RR 0.87 (0.52 to 1.46) | 3559 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowc,d,e | ||

| 17 per 1000 | 15 per 1000 (9 to 25) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 17 per 1000 | 15 per 1000 (9 to 25) | |||||

| Cow's milk allergy ‐ childhood (incidence) Follow‐up: mean 3 years | Study population | RR 7.11 (0.35 to 143.84) | 90 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c | ||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

aMethodological concerns including quasi‐random sequence allocation, incomplete outcome data and imbalances at baseline bImprecision of estimate ‐ single small study cReported by only a single study dMethodological concerns including quasi‐random sequence allocation and incomplete outcome data eImpression of estimate ‐ low incidence of outcome

Summary of findings 2.

Early short‐term feeding: hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula ‐ low‐risk infants for prevention of allergic disease and food allergy

| Early short‐term feeding of hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula for prevention of allergic disease and food allergy | ||||||

| Patient or population: infants not selected for allergy risk Settings: hospitals Intervention: early short‐term feeding of hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula for prevention of allergic disease and food allergy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Early short‐term feeding: hydrolysed formula vs cow's milk formula ‐ low‐risk infants | |||||

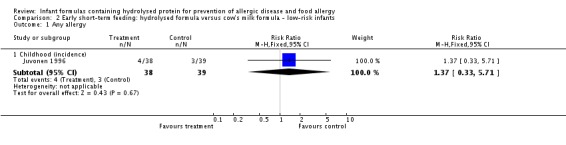

| Any allergy ‐ childhood (incidence) Follow‐up: mean 3 years | Study population | RR 1.37 (0.33 to 5.71) | 77 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c | ||

| 77 per 1000 | 105 per 1000 (25 to 439) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 77 per 1000 | 105 per 1000 (25 to 440) | |||||

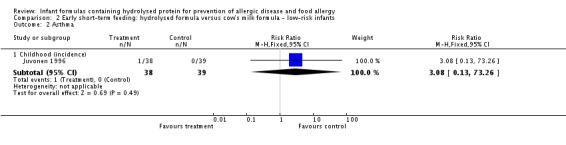

| Asthma ‐ childhood (incidence) Follow‐up: mean 3 years | Study population | RR 3.08 (0.13 to 73.26) | 77 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c | ||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

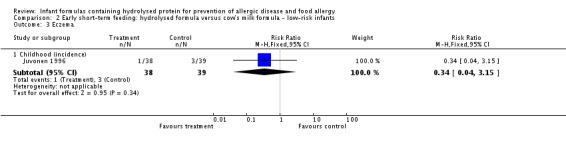

| Eczema ‐ childhood (incidence) Follow‐up: mean 3 years | Study population | RR 0.34 (0.04 to 3.15) | 77 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c | ||

| 77 per 1000 | 26 per 1000 (3 to 242) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 77 per 1000 | 26 per 1000 (3 to 243) | |||||

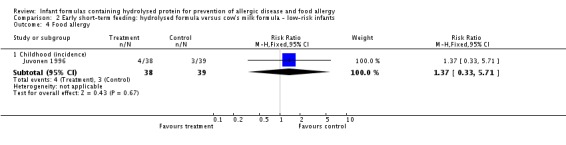

| Food allergy ‐ childhood (incidence) Follow‐up: mean 3 years | Study population | RR 1.37 (0.33 to 5.71) | 77 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c | ||

| 77 per 1000 | 105 per 1000 (25 to 439) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 77 per 1000 | 105 per 1000 (25 to 440) | |||||

| Cow's milk allergy ‐ infancy (incidence) Follow‐up: mean 3 years | Study population | RR 0.62 (0.38 to 1) | 3473 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,c,d | ||

| 24 per 1000 | 15 per 1000 (9 to 24) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 25 per 1000 | 15 per 1000 (9 to 25) | |||||

| Cow's milk allergy ‐ childhood (incidence) Follow‐up: mean 3 years | Study population | RR 5.13 (0.25 to 103.43) | 77 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c | ||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

aMethodological concerns including quasi‐random sequence allocation, incomplete outcome data and imbalances at baseline bImprecision of estimate ‐ single small study cReported only by a single study dImprecision of estimate ‐ low incidence of outcome

Summary of findings 3.

Prolonged feeding: hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula for prevention of allergic disease and food allergy

| Prolonged feeding of hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula for prevention of allergic disease and food allergy | ||||||

| Patient or population: infants Settings: infant feeding Intervention: prolonged feeding of hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula for prevention of allergic disease and food allergy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Prolonged feeding: hydrolysed formula vs cow's milk formula | |||||

| Any allergy ‐ infancy (incidence) Follow‐up: 2 years | Study population | RR 0.82 (0.72 to 0.95) | 2852 (8 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b | ||

| 294 per 1000 | 241 per 1000 (212 to 279) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 395 per 1000 | 324 per 1000 (284 to 375) | |||||

| Any allergy ‐ childhood (incidence) Follow‐up: 3 years | Study population | RR 0.85 (0.69 to 1.05) | 950 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c,d | ||

| 353 per 1000 | 300 per 1000 (244 to 371) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 381 per 1000 | 324 per 1000 (263 to 400) | |||||

| Asthma ‐ infancy (incidence) Follow‐up: 2 years | Study population | RR 0.57 (0.31 to 1.04) | 318 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,d | ||

| 175 per 1000 | 100 per 1000 (54 to 182) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 149 per 1000 | 85 per 1000 (46 to 155) | |||||

| Eczema ‐ infancy (incidence) Follow‐up: 2 years | Study population | RR 0.86 (0.73 to 1.01) | 2896 (9 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,d | ||

| 223 per 1000 | 191 per 1000 (162 to 225) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 200 per 1000 | 172 per 1000 (146 to 202) | |||||

| Rhinitis ‐ infancy (incidence) Follow‐up: 2 years | Study population | RR 0.52 (0.14 to 1.85) | 256 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,d | ||

| 58 per 1000 | 30 per 1000 (8 to 107) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

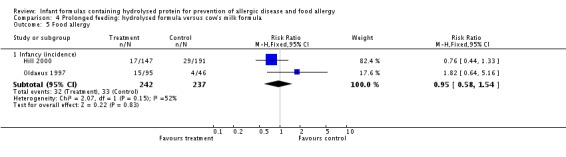

| Food allergy ‐ infancy (incidence) Follow‐up: 2 years | Study population | RR 0.95 (0.58 to 1.54) | 479 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,d | ||

| 139 per 1000 | 132 per 1000 (81 to 214) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 119 per 1000 | 113 per 1000 (69 to 183) | |||||

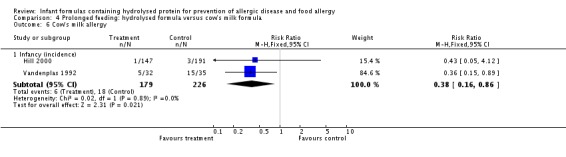

| Cow's milk allergy ‐ infancy (incidence) Follow‐up: 2 years | Study population | RR 0.38 (0.16 to 0.86) | 405 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,d | ||

| 80 per 1000 | 30 per 1000 (13 to 68) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 222 per 1000 | 84 per 1000 (36 to 191) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

aSubstantial methodological concerns. Sensitivity analysis found no study considered at low risk of bias bNot reported by all studies cSignificant heterogeneity between studies dImprecision of estimate

Background

Description of the condition

Food allergy and allergic disease are prevalent and represent a substantial health problem that may be increasing in developed countries (Burr 1989; Halken 2004; Prescott 2005; Schultz Larsen 1996). Although less than half of those who develop childhood allergic disease have a first‐degree relative with a history of allergy, the risk of allergy increases substantially with a positive family history (Bergmann 1994; Sears 1996; Tariq 1998). Approximately 10% of children without an allergic first‐degree relative develop allergic disease compared with 20% to 30% with an allergic first‐degree relative (parent or sibling) and 40% to 50% with two affected relatives (Arshad 2005; Bergmann 1997; Hansen 1993; Kjellman 1977). The predictive value of family history is increased with the addition of cord blood immunoglobulin (Ig) E antibody testing, although its accuracy may not be adequate for population screening (Bergmann 1997; Bergmann 1998; Tariq 1998).

Manifestations of allergic disease are age dependent. Infants commonly present with symptoms and signs of atopic eczema, gastrointestinal symptoms and recurrent wheezing. Asthma and rhinoconjunctivitis become prevalent in later childhood. Sensitisation to allergens tends to follow a characteristic pattern (Halken 2004), with sensitisation to food allergens in the first two to three years of life, followed by indoor allergens (e.g. house dust mite, pets) and subsequently outdoor allergens (e.g. rye, timothy grass). The cumulative prevalence of allergic disease during childhood is high, with up to 7% to 8% developing a food allergy, 15% to 20% atopic eczema and 31% to 34% asthma or recurrent wheezing (Halken 2004). Of these, 7% to 10% will continue to have asthma symptoms beyond five years of age (Halken 2004). Food hypersensitivities affect approximately 6% of infants younger than three years, and prevalence decreases over the first decade (Osterballe 2005; Sampson 2004).

Allergy may be diagnosed by questionnaire or clinician assessment, and the diagnosis may be confirmed by specific skin or serological testing, or by allergen challenge. Diagnostic criteria for different allergic diseases are not uniform, and the mode of ascertainment of allergic disease is variable. Although tests of bronchial hyperresponsiveness, challenge tests and classical tests of IgE‐mediated allergy have an imperfect correlation with allergy symptoms and clinical signs (Darsow 2000; Peat 2000), they are associated with an increased likelihood of allergy and disease (Ronmark 2001; Sears 1998; Sly 1999; Strachan 1996). In addition, some evidence suggests that questionnaires, although compromised by selection and recall bias (Peat 2001), are suitable for allergy screening (Kilpelainen 2001; Ravault 2001). This review includes trials that diagnosed allergy by questionnaire or by clinician assessment, with or without confirmation by laboratory testing. Criteria for diagnosis of allergic disease should include typical symptoms and/or signs, with evidence of precipitants, persistence or recurrence typical of allergic disease, or with test evidence confirming atopy or bronchial hyperreactivity.

The World Allergy Organization 2003 consensus (Johansson 2004) recommended that the term 'hypersensitivity' should be used to describe objectively reproducible symptoms or signs initiated by exposure to a defined stimulus at a dose tolerated by normal persons. 'Allergy' is a hypersensitivity reaction initiated by specific immunological mechanisms. The term 'food allergy' is used when immunological mechanisms have been demonstrated. Food‐specific IgG antibodies in serum are not of clinical importance but merely indicate previous exposure to a specific food. If IgE is involved in the reaction, the term 'IgE‐mediated food allergy' is appropriate. Food hypersensitivity is diagnosed by resolution of typical symptoms with elimination from the diet, with confirmation by blinded challenge. Around 2% to 3% of babies develop hypersensitivity to a particular food. Principal symptoms among infants with proven cow's milk protein hypersensitivity (CMPH) are gastrointestinal (˜ 50%), dermatological (˜ 31%) and respiratory (˜ 19%) in nature (Host 1994; Host 1995; Schrander 1993). Two of every three infants with CMPH have a family history of atopy (Schrander 1993). CMPH is strongly associated with feeding of cow's milk formula (CMF) to infants during the first month of life (Host 1991). Many infants with CMPH become tolerant over time, with approximately 30% at one year, 50% at two years and 70% at three years tolerant to cow's milk challenge. The risk of persisting hypersensitivity is increased with evidence of atopy (Host 1995).

Description of the intervention

Measures to prevent allergy and food allergy have included maternal allergen avoidance during pregnancy (Custovic 2000; Custovic 2001; Kramer 2001; Zeiger 1989) and/or lactation (Custovic 2000; Custovic 2001; Zeiger 1989), periods of exclusive breast feeding (Custovic 2000; Custovic 2001; Gruskay 1982; Oddy 1999; Saarinen 1995; Saarinen 2000) and avoidance of potential allergens including food and environmental antigens during the first year of life and beyond (Custovic 2000). Formulas prescribed for infants with the intention of preventing allergy and food allergy include hydrolysed cow's milk and elemental formula, as well as soy or hydrolysed soy formula. These formulas may be produced from cow's milk or soy milk, may be derived predominantly from whey or casein proteins and may be partially or extensively hydrolysed. Protein modification is performed through a variety of physiochemical processes including ultraheating and enzymatic cleavage, most often with trypsin and chymotrypsin.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that hypoallergenic formulas should be tested in trials in which investigators examine human infants for toxicity and suitability to maintain a positive nitrogen balance, while attempting to predict whether infants allergic to cow’s milk will react adversely to these formulas (AAP 2000). These formulas are studied in infants with cow’s milk or cow’s milk‐based formula allergic reactions verified by double‐blind placebo‐controlled challenge (DBPCC) (Bock 1988). At a minimum, these tests should ensure with 95% confidence that 90% of infants with documented cow’s milk allergy respond to treatment and do not react during challenge (Kleinman 1991). Protein particle size does not appear to be a prerequisite for defining a formula as hypoallergenic, although amino acid‐based formulas and those with more extensive hydrolysis are less likely to produce reactions among infants with cow's milk allergy (Hill 2007). Although universal agreement has not been reached on the definition (Chaffen 2010; Host 1999), for the purposes of this review an extensively hydrolysed formula (EHF) will be regarded as one meeting the AAP definition for hypoallergenic formula (AAP 2000), and those with less extensive hydrolysis will be regarded as partially hydrolysed.

How the intervention might work

Infants' immune systems become sensitised or tolerant to allergens in the order in which they are exposed. Early life exposure to allergens occurs frequently through ingested protein, particularly cow's milk protein in formula (Muraro 2004). Amino acid‐based and extensively hydrolysed protein formulas are produced so as to substantially reduce the antigenicity of the protein and prevent sensitisation of infants to commonly ingested antigens, including cow's milk protein. However, low concentrations of food allergens, especially cow's milk proteins, are present in human milk. It has been suggested that the low incidence of cow's milk protein allergy among exclusively breast fed infants ‐ at 0.5% in unselected infants and 1.3% in high‐risk infants ‐ in prospective birth cohort studies was due to low‐level exposure‐induced tolerance rather than to disease (Halken 2004). It has been proposed that prolonged exposure to allergenic proteins or to proteins with reduced but not absent allergenicity may induce tolerance over time (Allen 2009). Although most infants with cow’s milk hypersensitivity exhibit this in the first year of life, more than 80% subsequently develop clinical tolerance (Katz 2011; Sampson 2004). The concern is that early avoidance of cow's milk protein may reduce the likelihood that infants will subsequently develop tolerance to the allergen (Katz 2010).

Why it is important to do this review

The aim of this review is to gather evidence on the use of hydrolysed formulas for prevention of allergy and food allergy. This review does not include treatment of infants with clinically recognised allergy or food allergy.

Objectives

To compare effects on allergy and food allergy when infants are fed a hydrolysed formula versus CMF or human breast milk. If hydrolysed formulas are effective, to determine what type of hydrolysed formula is most effective, including extensively or partially hydrolysed formula (EHF/PHF). To determine which infants at low or high risk of allergy and which infants receiving early, short‐term or prolonged formula feeding may benefit from hydrolysed formulas.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We searched for randomised and quasi‐randomised trials that compared the use of a hydrolysed formula versus human milk or cow's milk formula. Randomised and quasi‐randomised (e.g. using alternation) trials with ≥ 80% follow‐up of participants were eligible for inclusion.

Types of participants

Infants in the first six months of life without clinical evidence of allergy.

Types of interventions

Hydrolysed formulas included:

hydrolysed cow's milk and soy formulas; and

extensively and partially hydrolysed formulas.

Hydrolysed formulas may be used for:

early, short‐term supplementary or sole formula feeding of infants unable to be exclusively breast fed in the first days of life;

prolonged supplementation of breast fed infants or infants fed solely with formula in the first months of life; and

weaning from the breast with infant formula.

The control group may include infants who receive:

exclusive human milk (breast fed or expressed); and

cow's milk formula.

Study authors had to prespecify the following comparisons.

Early short‐term hydrolysed formula versus human milk.

Prolonged use of a hydrolysed formula versus human milk.

Early short‐term hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula.

Prolonged use of a hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula.

Prespecified subgroup analyses included the following (see Methods for definitions).

Infant risk of allergy or food allergy.

Low‐risk infants (no family history of allergy or food allergy among first‐degree relatives).

High‐risk infants (family history of allergy or food allergy among first‐degree relatives or high cord IgE level).

Extent of protein hydrolysis.

Extensively hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula.

Partially hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula.

Extensively hydrolysed formula versus partially hydrolysed formula.

Indication for use.

Prolonged sole formula feeding.

Supplemental feeding or weaning from the breast using infant formula.

Method of ascertainment of allergy.

Allergy/Food allergy confirmed by test.

Blinded measurement for allergy or food allergy.

Type of protein hydrolysate used.

Partially hydrolysed whey formula versus cow's milk formula.

Partially hydrolysed casein formula versus cow's milk formula.

Extensively hydrolysed whey formula versus cow's milk formula.

Extensively hydrolysed casein formula versus cow's milk formula.

Hydrolysed soy formula versus cow's milk formula.

We excluded studies that included other allergy prevention interventions (e.g. maternal dietary avoidance measures, environmental allergy reduction measures) in the treatment group and not in the control group. Studies that provided other allergy prevention interventions for both treatment and control groups were eligible.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

All allergies, including asthma, atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis and food allergy

Secondary outcomes

Asthma

Atopic dermatitis/Eczema

Allergic rhinitis

Cow's milk or soy protein allergy

Food allergy

Urticaria

Anaphylaxis

In the 2013 review update, we no longer reported previously reported food hypersensitivity and potential harms, including growth parameters, cost and infant feed refusal.

Researchers may have diagnosed a specific allergy on the basis of:

history of recurrent and persistent symptoms typical of the allergy;

clinician diagnosis of allergy; or

clinical allergy confirmed by testing including detection of allergen sensitisation by skin testing or by serological testing for specific IgE (e.g. radio‐allergosorbent (RAST), enzyme‐allergosorbent (EAST)), or asthma confirmed by respiratory function testing for the presence of bronchial hyperresponsiveness confirmed by elimination/challenge.

Investigators used the following definitions of age of allergy.

Infant allergy incidence: allergy occurring up to two years of age.

Childhood allergy incidence: allergy occurring up to 10 years of age (or up to age of latest report between two and 10 years).

Childhood allergy prevalence: reported allergy that was present between two and 10 years of age.

Adolescent allergy: allergy present from 10 to 18 years of age.

Adult allergy: allergy present after 18 years of age.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

See the Collaborative Review Group search strategy.

2016 update: We performed an updated search of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; August 2016), MEDLINE (1948 to August 2016) and Embase (1974 to August 2016). We also searched citations of authors of included studies and citation lists of articles and reviews.

We documented the search strategies in Appendix 1,Appendix 2 and Appendix 3.

Searching other resources

We performed a search of previous reviews including cross references (all articles referenced), abstracts, conferences (Pediatric Academic Societies 2003 to 2016; Perinatal Society of Australia and New Zealand 2003 to 2016), recent review citations and expert informants.

We also updated in August 2016 our search of clinical trials registries for ongoing or recently completed trials (clinicaltrials.gov; controlled‐trials.com; who.int/ictrp).

Data collection and analysis

This review updates previous versions (Osborn 2003; Osborn 2006).

Each review author independently assessed eligibility of studies for inclusion. We included only studies with ≥ 80% reporting of randomised infants. We used the criteria and standard methods of the Cochrane Neonatal Review Group to assess the methodological quality of included trials regarding adequacy of randomisation and allocation concealment, blinding of parents or caregivers and assessors to intervention and completeness of assessment of all randomised individuals. We used a data collection form to aid extraction of relevant information and data from each included study. Each review author extracted the data separately, and review authors compared data and resolved differences by consensus. We used the standard methods of the Cochrane Neonatal Review Group to synthesise the data and expressed effects as risk ratio (RR), risk difference (RD) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for categorical data, and as mean difference (MD) and 95% CIs for continuous data. We used the Chi² test to examine data for heterogeneity, and we quantified heterogeneity using the I² statistic. We used the fixed‐effect model for meta‐analysis when enrolled infants and interventions were similar and no significant heterogeneity was found. We explored sources of heterogeneity by performing subgroup analysis.

The term 'hydrolysed formula' used without a reference to type refers to both extensively and partially hydrolysed formulas. We did not pool studies that used hydrolysed formula for early (first few days of life) supplemental or sole infant feeding with studies that used hydrolysed formula for prolonged feeding. We performed all comparisons by including only studies with no different co‐interventions prescribed for prevention of allergy in either study arm (e.g. in treatment group but not in control group). Allergy‐preventing co‐interventions included modifications to mother's diet when pregnant or breast feeding and environmental modifications such as avoidance of pet hair and host dust mite reduction measures. The protocol did not originally prespecify that we should restrict analyses to studies with no differential co‐interventions.

Selection of studies

We included all randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials fulfilling the selection criteria described in the previous section. Each review author reviewed the search results and separately selected studies for inclusion. Review authors resolved disagreements by discussion.

Data extraction and management

Each review author extracted the data separately. Review authors compared data and resolved differences by consensus.

We obtained additional method details and data from the authors of two studies (Hill 2000; von Berg 2003). For one study (Lam 1992), we extracted methods and data from a thesis.

For the 2013 update, we performed all analyses using Review Manager software (RevMan 2011).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We used the criteria and standard methods of the Cochrane Neonatal Review Group to assess the methodological quality of included trials. We evaluated the quality of included trials in terms of adequacy of randomisation and allocation concealment, blinding of parents or caregivers and assessors to intervention and completeness of assessment in all randomised individuals.

For the 2016 update, we incorporated previous assessments into RevMan 5 'Risk of bias' tables. We assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) by examining the following.

Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

Adequate (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator)

Inadequate (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number)

Unclear

Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

Adequate (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes)

Inadequate (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth)

Unclear

Blinding (checking for possible performance bias)

Adequate, inadequate or unclear for participants

Adequate, inadequate or unclear for personnel

Adequate, inadequate or unclear for outcome assessors

Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

Adequate (< 20% missing data)

Inadequate

Unclear

Selective reporting bias

Adequate (when it is clear that all of the study’s prespecified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported)

Inadequate (when not all of the study’s prespecified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified; outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study failed to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported)

Unclear

Other sources of bias

We assessed the possibility of other sources of bias (e.g. early termination of trial due to data‐dependent process, extreme baseline imbalance) as follows.

Yes.

No.

Unclear.

Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). With reference to the criteria above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of bias, and whether it was likely to have an impact on study findings. We explored the impact of the level of bias by undertaking sensitivity analyses (see Sensitivity analysis section).

Measures of treatment effect

We used the standard methods of the Cochrane Neonatal Review Group to synthesise data and expressed effects as risk ratio (RR) and risk difference (RD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for categorical data, and as mean difference (MD) with 95% CIs for continuous data.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the individual participant (infant).

Dealing with missing data

We recorded missing data in 'Risk of bias' tables and assessed the effect of missing data by performing sensitivity analysis.

We performed all analyses by 'intention to treat' when data were available. When intention‐to‐treat data were not available, we reported data as infants assessed by group of assignment as well as losses after randomisation.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used the two formal statistics described here.

Chi2 test: to assess whether observed variability in effect sizes between studies is greater than would be expected by chance. This test has low power when the number of studies included in the meta‐analysis is small, so we planned to set the probability at the 10% level of significance.

I2 statistic: to ensure that pooling of data is valid. We planned to grade the degree of heterogeneity as follows: 0% to 30%: might not be important; 31% to 50%: moderate heterogeneity; 51% to 75%: substantial heterogeneity; 76% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

When we found evidence of apparent or statistical heterogeneity, we planned to assess the source of the heterogeneity by conducting sensitivity and subgroup analyses to look for evidence of bias or methodological differences between trials.

Assessment of reporting biases

We documented in the Characteristics of excluded studies table all studies that reported use of a prebiotic in a potentially eligible infant population but did not report allergy‐related outcomes. We assessed reporting and publication bias by examining the degree of asymmetry of a funnel plot.

Data synthesis

We used the fixed‐effect model and Mantel‐Haenszel methods for meta‐analysis.

Quality of evidence

We used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach, as outlined in the GRADE Handbook (Schünemann 2013), to assess the quality of evidence for the following (clinically relevant) outcomes: all allergy; specific allergies including asthma, atopic dermatitis/eczema, allergic rhinitis, cow's milk or soy protein allergy, food allergy, urticarial allergy and anaphylaxis.

Two review authors independently assessed the quality of the evidence for each of the outcomes above. We considered evidence from randomised controlled trials as high quality but downgraded the evidence one level for serious (and two levels for very serious) limitations on the basis of the following: design (risk of bias), consistency across studies, directness of evidence, precision of estimates and presence of publication bias. We used the GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool to create a ‘Summary of findings’ table to report the quality of the evidence.

The GRADE approach yields an assessment of the quality of a body of evidence by one of four grades.

High: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to the estimate of effect.

Moderate: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect but may be substantially different.

Low: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Very low: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed subgroup analyses according to the following.

Infant risk of allergy or food allergy: low‐risk infants (no family history of allergy or food allergy in first‐degree relatives); high‐risk infants (family history of allergy or food allergy in first‐degree relatives or high cord blood IgE level).

Extent of protein hydrolysis: EHF versus CMF; PHF versus CMF; EHF versus PHF. An EHF should meet the definition provided by the AAP Committee on Nutrition (AAP 2000) ‐ extensively hydrolysed proteins derived from cow's milk in which most of the nitrogen is present in the form of free amino acids and peptides ≤ 1500 kDaltons ‐ and should, at a minimum, ensure with 95% confidence that 90% of infants with documented CMA will not react with defined symptoms to the formula under double‐blind, placebo‐controlled conditions.

Indication for use: prolonged sole formula feeding; supplemental formula feeding; weaning from the breast with infant formula.

Method of ascertainment of allergy or food allergy: clinical allergy confirmed by challenge testing or by testing for atopy (e.g. skin testing or serological testing for specific IgE, asthma confirmed by testing for presence of bronchial hyperresponsiveness, food allergy confirmed by elimination/challenge). Included in this definition is clinical allergy in a patient for whom atopy has been confirmed by testing (e.g. asthma when atopy has been confirmed by skin prick testing or RAST for specific IgE); blinded measurement for allergy or food allergy ‐ when measurement of outcome was blinded to treatment allocation (this analysis was not prespecified).

Type of protein hydrolysate used: partially hydrolysed whey formula versus CMF; partially hydrolysed casein formula versus CMF; extensively hydrolysed whey formula versus CMF; extensively hydrolysed casein formula versus CMF; hydrolysed soy formula versus CMF.

Sensitivity analysis

We prespecified a sensitivity analysis to determine whether review findings were affected by including only studies at low risk of bias, defined as those with adequate randomisation and allocation concealment and < 10% loss to follow‐up.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

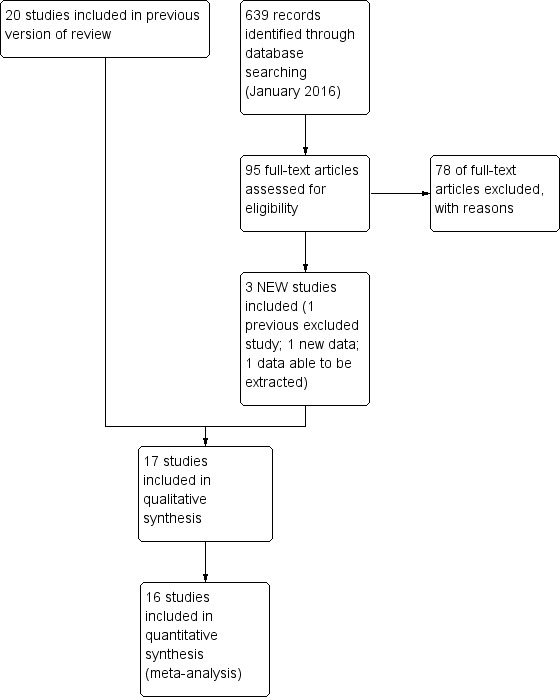

We performed searches on 22 January 2016 (see Figure 1 for study flow diagram). We searched MEDLINE using OVID and retrieved 198 reports (Appendix 1); CENTRAL and retrieved 242 reports (Appendix 2); and Embase and retrieved 199 reports (Appendix 3). We identified eight ongoing or unpublished studies (Baldassarre 2013; Barber 2009; Del Moral 2010; Knip 2012; Mennella 2012; Sorensen 2010; Vivatvakin 2009; Yin 2015) (see Appendix 3 and Appendix 4). We updated the search on 30 August 2016 and found one additional excluded study (Boyle 2016) and an additional 15‐year follow‐up report from a previously included study (von Berg 2003).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram: review update.

Included studies

We assessed 17 studies as eligible for inclusion ‐ see Characteristics of included studies table. The 2016 search revealed two additional studies that we assessed as included studies (Kwinta 2009; Sorensen 2007). We found an additional publication (Hill 2000) of a study that we had previously assessed as an excluded study as it had reported a per‐protocol analysis with excess losses. We combined a new report of an 'intention‐to‐treat' analysis with trial data obtained from study authors and have now assessed this trial as an included study. Sorensen 2007 (n = 242) has not reported extractable data to date that can be included in a meta‐analysis. This study compared a CMF versus a PHF versus an EHF in infants at high risk of allergy and is not included in the risk of bias assessment and analyses. Data from sequential publications of the GINI study (von Berg 2003) beyond three years remain ineligible for inclusion in this review owing to excess losses to follow‐up. As no new data have been made available, we have moved to the excluded studies list four previously included studies (Maggio 2005; Picaud 2001; Szajewska 2001; Vandenplas 1993) that provided no outcome data for the previous version (Osborn 2006).

Types of infants enrolled

High risk of allergy: A total of 14 studies (Chirico 1997; de Seta 1994; Halken 2000; Hill 2000; Lam 1992; Mallet 1992; Marini 1996; Nentwich 2001; Oldaeus 1997; Sorensen 2007; Tsai 1991; Vandenplas 1992; von Berg 2003; Willems 1993) enrolled infants at high risk of allergy on the basis of a history of allergy in a first‐degree relative and/or a high cord IgE level, although Lam 1992 did not report 'high risk' criteria.

Risk of allergy not specified: Three studies did not enrol infants on the basis of risk of allergy: Juvonen 1996 enrolled healthy term infants, although 62% had a family history of allergy; Kwinta 2009 enrolled very low birth weight infants (≤ 1500 g); and Saarinen 1999 enrolled healthy term infants requiring supplemental feeding in hospital.

Low risk of allergy: No study reporting allergy outcomes enrolled infants at low risk of allergy.

Types of interventions

See Characteristics of included studies for types of formula used in each study.

Early short‐term feeding: hydrolysed formula versus human milk feeding ‐ low‐risk infants

Two studies (Juvonen 1996; Saarinen 1999) compared a hydrolysed formula versus pasteurised donor human milk used for early short‐term infant feeding. Juvonen 1996 gave sole bottle feeds for three days, then all infants were exclusively breast fed. Saarinen 1999 gave supplemental feeds when required while infants were in hospital (average four days). Mothers were then encouraged to breast feed.

Early short‐term feeding: hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula ‐ low‐risk infants

Two studies (Juvonen 1996; Saarinen 1999) compared a hydrolysed formula versus CMF for early short‐term infant feeding. Juvonen 1996 gave sole bottle feeds for three days, then all infants were exclusively breast fed. Saarinen 1999 gave supplemental feeds when required while infants were in hospital (average four days). Mothers were then encouraged to breast feed.

Prolonged feeding: hydrolysed formula versus human milk feeding

We found no studies for this comparison.

Prolonged feeding: hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula

Thirteen studies compared prolonged supplemental or sole feeding with a hydrolysed formula versus CMF without differential co‐interventions (Chirico 1997; de Seta 1994; Hill 2000; Kwinta 2009; Lam 1992; Mallet 1992; Marini 1996; Oldaeus 1997; Sorensen 2007; Tsai 1991; Vandenplas 1992; von Berg 2003; Willems 1993). Three studies (Chirico 1997; Marini 1996; Oldaeus 1997) reported additional allergy avoidance measures in both hydrolysed formula and CMF groups.

Prolonged feeding: hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula ‐ low‐risk infants

Kwinta 2009 compared prolonged feeding with a hydrolysed formula versus CMF in low‐risk infants.

Prolonged feeding: hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula ‐ high‐risk infants

Twelve studies (Chirico 1997; de Seta 1994; Hill 2000; Lam 1992; Mallet 1992; Marini 1996; Oldaeus 1997; Sorensen 2007; Tsai 1991; Vandenplas 1992; von Berg 2003; Willems 1993) compared prolonged feeding with a hydrolysed formula versus CMF in high‐risk infants.

Prolonged feeding: partially hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula

Twelve studies (Chirico 1997; de Seta 1994; Kwinta 2009; Hill 2000; Lam 1992; Marini 1996; Oldaeus 1997; Sorensen 2007; Tsai 1991; Vandenplas 1992; von Berg 2003; Willems 1993) compared prolonged feeding with a PHF versus CMF.

Prolonged feeding: extensively hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula

Five studies (Kwinta 2009; Mallet 1992; Oldaeus 1997; Sorensen 2007; von Berg 2003) compared prolonged feeding with an EHF versus CMF.

Prolonged feeding: extensively hydrolysed formula versus partially hydrolysed formula

Five studies (Halken 2000; Nentwich 2001; Oldaeus 1997; Sorensen 2007; von Berg 2003) compared prolonged feeding with an EHF versus a PHF.

Prolonged exclusive feeding: hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula

Seven studies reported prolonged exclusive hydrolysed formula versus CMF (Chirico 1997; de Seta 1994; Kwinta 2009; Lam 1992; Marini 1996; Vandenplas 1992; Willems 1993). It is unclear whether the period of formula feeding was exclusive for one study (Sorensen 2007).

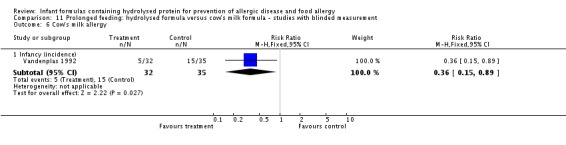

Prolonged feeding: hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula ‐ studies with blinded measurement

Four studies assessed allergy without knowledge of participant allocation (Kwinta 2009; Oldaeus 1997; Vandenplas 1992; von Berg 2003).

Prolonged feeding: hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula ‐ studies at low risk of bias

We assessed no studies as eligible for inclusion in the sensitivity analysis of adequate study methods (adequate randomisation, allocation concealment and < 10% losses to follow‐up).

Prolonged feeding: partially hydrolysed whey formula versus cow's milk formula

Ten studies (Chirico 1997; de Seta 1994; Hill 2000; Lam 1992; Marini 1996; Sorensen 2007; Tsai 1991; Vandenplas 1992; von Berg 2003; Willems 1993) compared a partially hydrolysed whey formula versus CMF.

Prolonged feeding: partially hydrolysed casein‐containing formula versus cow's milk formula

Two studies (Kwinta 2009; Oldaeus 1997) compared a PHF containing casein versus CMF.

Prolonged feeding: extensively hydrolysed whey formula versus cow's milk formula

Two studies (Sorensen 2007; von Berg 2003) compared an extensively hydrolysed whey formula versus CMF.

Prolonged feeding: extensively hydrolysed casein formula versus extensively hydrolysed whey formula

Two studies (Halken 2000; von Berg 2003) compared an extensively hydrolysed casein formula versus CMF.

No study compared a hydrolysed soy formula versus CMF. No study compared a hydrolysed soy formula versus hydrolysed CMF.

Types of outcomes

Definitions for allergy varied between studies but usually required persistent or recurring symptoms and signs in the absence of another obvious clinical explanation. For definitions of 'any allergy' and type of allergy for each study, see Characteristics of included studies.

Sorensen 2007 has not reported extractable data to date that can be included in a meta‐analysis. This study enrolled infants at high risk of allergy.

Studies (with timing) reporting clinician‐diagnosed allergy included Chirico 1997 (six months); de Seta 1994 (six and 24 months); Halken 2000 (six, 12 and 18 months); Hill 2000 (two and six to seven years); Juvonen 1996 (three years); Kwinta 2009 (five to seven years); Lam 1992 (six months); Mallet 1992 (one, two and four years); Marini 1996 (six months, one and three years); Nentwich 2001 (six and 12 months); Oldaeus 1997 (nurse examination at three, six, nine, 12 and 18 months and doctor visit at 18 months); Saarinen 1999 (mean age at follow‐up of 27 months, range 18 to 34 months); Sorensen 2007 (12 months); Tsai 1991 (one, two, four, six and 12 months); Vandenplas 1992 (12 months); and von Berg 2003 (12 months and three, six and 10 years ‐ note excess losses from three years of age).

Three studies reported using questionnaire‐diagnosed allergy: Hill 2000 (six to seven years); Kwinta 2009 (five to seven years); and Willems 1993 (three months and one year).

Seven studies reported specific food allergy (Halken 2000; Hill 2000; Juvonen 1996; Oldaeus 1997; Saarinen 1999; Vandenplas 1992; von Berg 2003).

Excluded studies

We excluded 79 studies and documented reasons for exclusion in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Here, we document controlled trials of hydrolysed formula according to types of participants and reasons for exclusion.

Preterm or low birth weight infants

Agosti 2003 did not report allergy; Florendo 2009 did not report allergy; Maggio 2005 did not report allergy; Mihatsch 1999 (cross‐over trial) did not report allergy; Mihatsch 2002 (excess losses) did not report allergy; Pauls 1996 did not report allergy (abstract format only); Picaud 2001 did not report allergy; Raupp 1995 did not report allergy; Riezzo 2001 did not report allergy; Szajewska 2001 did not report allergy; and Yu 2014 (likely non‐random, cross‐over) did not report allergy.

Term healthy infants

Akimoto 1993 reported allergy (non‐random); Berseth 2009 (multiple formula differences) did not report allergy; Borschel 2013 did not report allergy; Borschel 2014 (multiple formula differences) did not report allergy; Borschel 2014a (multiple formula differences) did not report allergy; Burks 2008 (excess losses) did not report allergy; de Jong 1998 used protein‐free formula; Decsi 1992 did not report allergy; Decsi 1998 did not report allergy; Exl 1998 reported allergy (non‐random); Fukushima 1997 reported allergy (excess losses); Hartman 1994 reported intolerance not allergy and reported unclear losses (abstract format only); Hernell 2003 (unclear allocation) did not report allergy; Keller 1996 (unclear allocation) reported allergy; Lasekan 2006 did not report allergy; Medjad‐Guillou 1992 (cross‐over trial) did not report allergy; Mennella 2011a did not report allergy; Moran 1992 reported excess losses; Paronen 2000 enrolled infants at risk of diabetes and did not report allergy; Rigo 1994a (unclear allocation) did not report allergy; Rigo 1994b (unclear allocation) did not report allergy; Scalabrin 2009 (excess losses) reported adverse events including allergy; Schmelzle 2003 (excess losses) did not report allergy; Schmitz 1992 did not report allergy (excess losses); Schrander 1993 was observational; Silva Rey 1996 (unclear allocation; excess losses) reported in a thesis only; Staelens 2008 did not report allergy; Tariq 1998 was observational; Vaarala 1995 did not report allergy; Vaarala 2012 (enrolled infants at risk of diabetes) did not report allergy; and Vandenplas 1993 did not report allergy.

Term infants at high risk of allergy

Arshad 1992a reported multiple differential allergy‐reducing co‐interventions; Barberi 1993 reported unclear allocation, excess losses and allergy (abstract format only); Bergmann 1996a reported allergy and non‐random allocation; Boyle 2016 reported multiple differential allergy‐reducing co‐interventions ‐ prebiotic and hydrolysed formulas ‐ and reported allergy; Chan 2002 reported allergy and excess losses; Chan‐Yeung 2000 reported multiple differential allergy‐reducing co‐interventions; Chandra 1989a reported data that could not be verified after allegations of fraud; Chandra 1989b reported data that could not be verified after allegations of fraud; D'Agata 1996 reported unclear allocation, imbalances between groups and allergy; Giovannini 1994 reported excess losses and did not report allergy; Halken 1992 reported allergy and excess losses; Kuo 2011 was observational; Iikura 1995 reported unclear allocation and imbalances between groups (abstract format only); Martinez‐Valverde reported unclear allocation in a thesis only; Moran 1992 reported excess losses and allergy; Nentwich 2003 was observational; Odelram 1996 reported excess losses and allergy; Porch 1998 reported excess losses; Shao 2006 reported multiple differential allergy‐reducing co‐interventions; Szajewska 2004 reported excess losses and allergy; TRIGR study 2011 did not report allergy; Vandenplas 1988 reported unclear allocation and losses; Wopereis 2014 did not report allergy to date (abstract format only); and Zeiger 1989 reported multiple co‐interventions and excess losses.

Infants with infantile colic, gastro‐oesophageal reflux symptoms or feed intolerance

Arikan 2008 did not report allergy; Campbell 1989 did not report allergy (non‐random); Corvaglia 2013 did not report allergy; Corvaglia 2013a did not report allergy; Hill 1995b did not report allergy; Lucassen 2000 did not report allergy; Nocerino 2012 did not report allergy (abstract format only); Savino 2003 was observational; Savino 2006 reported multiple formula differences; Taubman 1988 did not report allergy; and Zeiger 1989 reported allergy and excess losses.

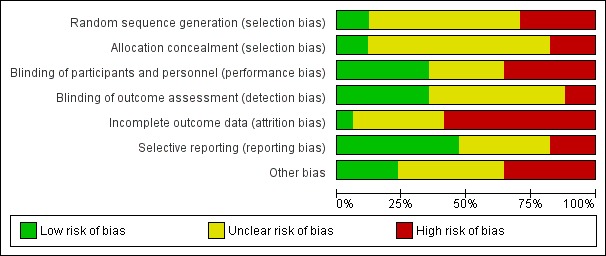

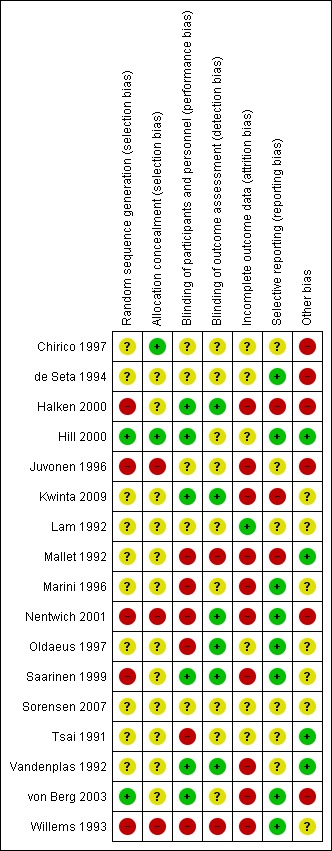

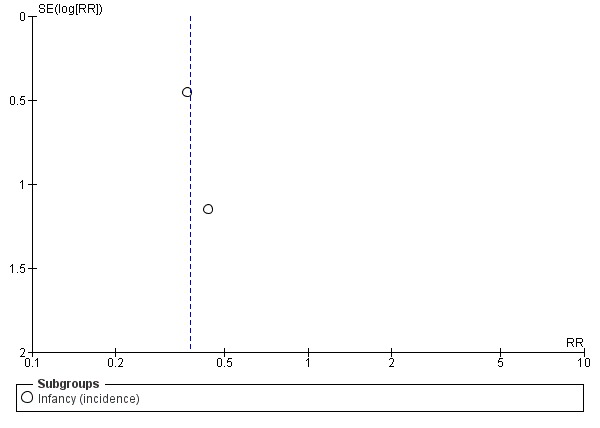

Risk of bias in included studies

We have summarised risk of bias in included studies in Figure 2; and Figure 3. Overall, we considered no studies to be at 'low risk' of bias.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Figure 3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Randomisation

Two studies reported an adequate method of randomisation (Hill 2000; von Berg 2003). Ten studies reported random allocation of infants but not the method of randomisation used (Chirico 1997; de Seta 1994; Lam 1992; Mallet 1992; Marini 1996; Oldaeus 1997; Tsai 1991; Vandenplas 1992), so we assessed their risk as 'unclear'. Five studies reported quasi‐random methods of participant allocation, including Halken 2000 (by date of birth), Juvonen 1996 (by day of month), Nentwich 2001 (odd and even numbers), Saarinen 1999 and Willems 1993 (month of birth), so we assessed them as having 'high risk'.

Allocation concealment

We assessed three studies as having 'low risk' of allocation concealment (Chirico 1997; Hill 2000; Tsai 1991) and 10 studies as having 'unclear' risk, including de Seta 1994 (did not report method of allocation), Halken 2000 (used quasi‐random allocation method but blinded intervention), Kwinta 2009 (used unclear allocation method), Lam 1992 (did not report method), Mallet 1992 (did not report method), Marini 1996 (did not report method), Oldaeus 1997 (did not report method), Saarinen 1999 (used quasi‐random allocation method but blinded intervention), von Berg 2003 (did not report method) and Vandenplas 1992 (used unclear allocation method). We assessed three studies as having 'high risk' for allocation concealment ‐ Juvonen 1996 (quasi‐random allocation, unblinded study), Nentwich 2001 (quasi‐random allocation, unblinded prescribing) and Willems 1993 (quasi‐random allocation, unblinded study).

Blinding

Six studies reported blinding of participants and personnel (Halken 2000; Hill 2000; Kwinta 2009; Saarinen 1999; Vandenplas 1992; von Berg 2003); we assessed four studies as having 'unclear' risk, as they did not report details (Chirico 1997; de Seta 1994; Juvonen 1996; Lam 1992) and six studies as unblinded (Mallet 1992; Marini 1996; Nentwich 2001; Oldaeus 1997; Tsai 1991; Willems 1993).

Six studies reported blinding of measurement (Halken 2000; Kwinta 2009; Nentwich 2001; Oldaeus 1997; Saarinen 1999; Vandenplas 1992). Eight studies did not report blinding of measurement of clinical allergy (Chirico 1997; de Seta 1994; Hill 2000; Juvonen 1996; Lam 1992; Marini 1996; Tsai 1991; von Berg 2003). Mallet 1992 and Willems 1993 performed unblinded measurements.

Incomplete outcome data

Studies reported losses to follow‐up. We included in this review only studies with < 20% loss to follow‐up. Studies reported the following losses to follow‐up: Chirico 1997 ‐ unclear; de Seta 1994 ‐ none reported; Halken 2000 ‐ 20% at 18 months; Hill 2000 ‐ 7.3% at two years and 20% at six to seven years; Juvonen 1996 ‐ 10% at three years; Kwinta 2009 ‐ 16% at five to seven years; Lam 1992 ‐ 8% at six months; Mallet 1992 ‐ 5% to 8% at four months but > 20% at one to four years; Marini 1996 ‐ 13% at two years and 19% at three years; Nentwich 2001 ‐ 19% at 12 months; Oldaeus 1997 ‐ 9% at 18 months; Saarinen 1999 ‐ unclear, although all infants were reported to be seen routinely in well baby clinics; Tsai 1991 ‐ 9% at 12 months; Vandenplas 1992 ‐ 11% at 12 months and > 20% at three and five years; von Berg 2003 ‐ for infants born in Wesel: 14.5% at one year and 19% at three years (all other analyses and time points > 20%); and Willems 1993 ‐ 13% at one year.

Studies with < 10% loss to follow‐up included de Seta 1994 ‐ none reported, Hill 2000 ‐ 7.3% at two years, Lam 1992 ‐ 8% at six months, Mallet 1992 ‐ 5% to 8% at four months, Oldaeus 1997 ‐ 9% at 18 months and Tsai 1991 ‐ 9% at 12 months.

Selective reporting

Eight studies were at 'low risk' of reporting bias with prespecified primary outcomes reported (de Seta 1994; Hill 2000; Marini 1996; Nentwich 2001; Oldaeus 1997; Saarinen 1999; von Berg 2003; Willems 1993). We assessed five studies as having 'unclear' risk of reporting bias (Chirico 1997; Juvonen 1996; Lam 1992; Tsai 1991; Vandenplas 1992) and three as having 'high risk' (Halken 2000; Kwinta 2009; Mallet 1992).

Other potential sources of bias

Six studies had imbalances between groups after randomisation, so we considered them to be at 'high risk' of bias (Chirico 1997; de Seta 1994; Halken 2000; Juvonen 1996; Nentwich 2001; von Berg 2003). Six studies did not report sufficient details of baseline characteristics or described differences of 'unclear' importance (Kwinta 2009; Lam 1992; Marini 1996; Oldaeus 1997; Saarinen 1999; Willems 1993). We considered four studies to have well‐balanced groups after randomisation with no other identified source of bias (Hill 2000; Mallet 1992; Tsai 1991; Vandenplas 1992).

We assessed no studies as having 'low risk' of bias overall ('low risk' of selection bias, performance and measurement bias and attrition bias with < 10% loss to follow‐up).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Analyses

Comparison 1. Early short‐term feeding: hydrolysed formula versus human milk feeding ‐ low‐risk infants

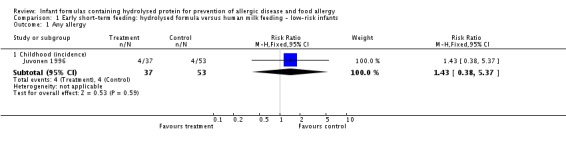

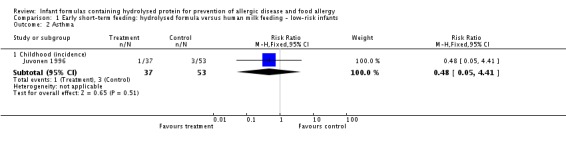

We included two studies (Juvonen 1996; Saarinen 1999) that compared a short duration (three to four days whilst in hospital) of early supplemental or sole hydrolysed formula versus donor human milk feeds in infants who were subsequently encouraged to breast feed.

Juvonen 1996 (90 infants) reported no difference in childhood incidence of allergy (risk ratio (RR) 1.43, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.38 to 5.37) and asthma (RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.05 to 4.41) and no difference in eczema (RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.05 to 4.41), no difference in food allergy (RR 1.43, 95% CI 0.38 to 5.37) and no difference in CMA (RR 7.11, 95% CI 0.35 to 143.84) at three years. Saarinen 1999 reported no difference in childhood incidence of CMA (3559 infants; RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.46) up to a mean age of 27 months.

We considered the following subgroup analyses, but as no significant benefits were reported, we did not wish to duplicate the results.

Both studies enrolled infants irrespective of family history of allergy or food allergy in first‐degree relatives.

Extent of protein hydrolysis: Juvonen 1996 and Saarinen 1999 compared an EHF versus pasteurised donor human milk.

Indication for use: Both studies used formula for early short‐term infant formula feeding.

Method of ascertainment of allergy: Saarinen 1999 reported outcomes of an unblinded elimination/challenge for CMA. Juvonen 1996 did not report criteria for diagnosis of allergy.

Type of protein hydrolysate used: Juvonen 1996 compared an extensively hydrolysed casein formula versus pasteurised donor human milk. Saarinen 1999 compared an extensively hydrolysed whey formula versus pasteurised donor human milk.

Sensitivity analysis

We considered neither study to be at 'low risk' of bias.

Comparison 2. Early short‐term feeding: hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula ‐ low‐risk infants

Two studies (Juvonen 1996; Saarinen 1999) compared a short duration (three to four days whilst in hospital) of early supplemental or sole feeding with a hydrolysed formula versus CMF. Both trials subsequently encouraged all mothers to breast feed.

Juvonen 1996 (77 infants) reported no difference in childhood allergy incidence (RR 1.37, 95% CI 0.33 to 5.71), no difference in childhood asthma incidence (RR 3.08, 95% CI 0.13 to 73.26), no difference in childhood eczema incidence (RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.04 to 3.15), no difference in childhood food allergy (RR 1.37, 95% CI 0.33 to 5.71) and no difference in childhood CMA (RR 5.13, 95% CI 0.25 to 103.43). Saarinen 1999 reported a reduction in infant CMA incidence of borderline significance (3478 infants; RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.00; risk difference (RD) ‐0.01, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.00; P = 0.05).

We considered the following subgroup analyses, but as no significant benefits were reported, we did not wish to duplicate the results.

Both studies enrolled infants irrespective of family history allergy or food allergy in first‐degree relatives.

Extent of protein hydrolysis: Juvonen 1996 and Saarinen 1999 compared an EHF versus CMF.

Indication for use: Both studies used formula for early short‐term infant formula feeding.

Method of ascertainment of allergy: Saarinen 1999 reported outcomes of an unblinded elimination/challenge for CMA. Juvonen 1996 did not report criteria for diagnosis of allergy.

Type of protein hydrolysate used: Juvonen 1996 compared an extensively hydrolysed casein formula versus CMF. Saarinen 1999 compared an extensively hydrolysed whey formula versus CMF.

Sensitivity analysis

We considered neither study to use adequate methods.

Comparison 3. Prolonged feeding: hydrolysed formula versus human milk feeding

We found no study that compared prolonged feeding with hydrolysed formula versus human milk feeding.

Comparison 4. Prolonged feeding: hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula

Twelve studies (Chirico 1997; de Seta 1994; Hill 2000; Kwinta 2009; Lam 1992; Mallet 1992; Marini 1996; Oldaeus 1997; Tsai 1991; Vandenplas 1992; von Berg 2003; Willems 1993) reported outcomes upon comparing prolonged hydrolysed formula versus CMF feeding.

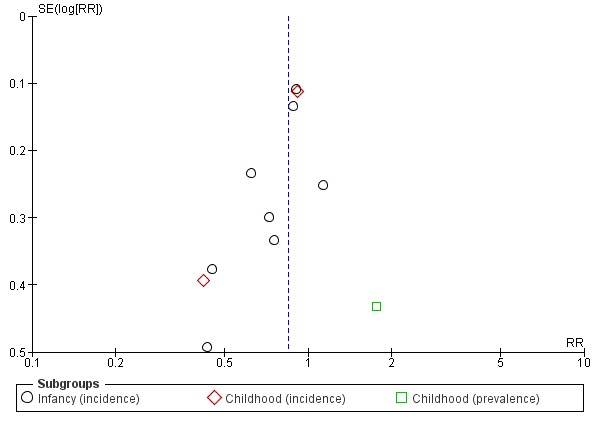

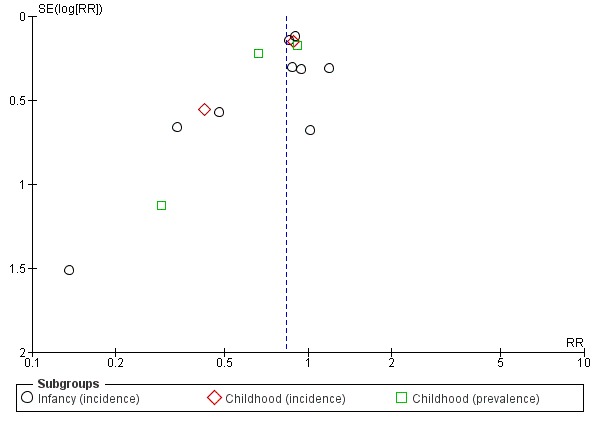

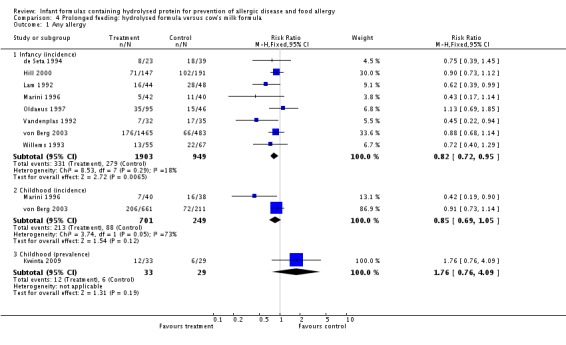

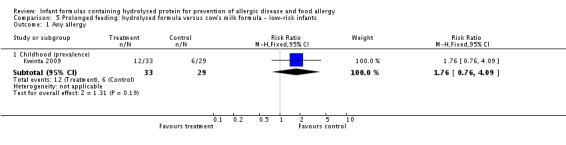

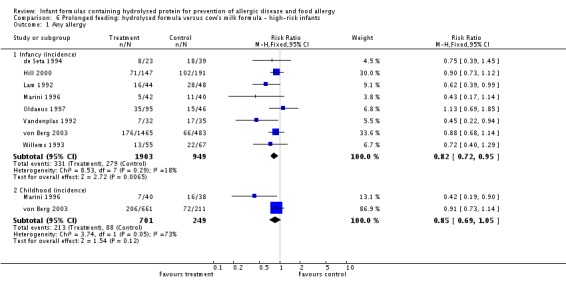

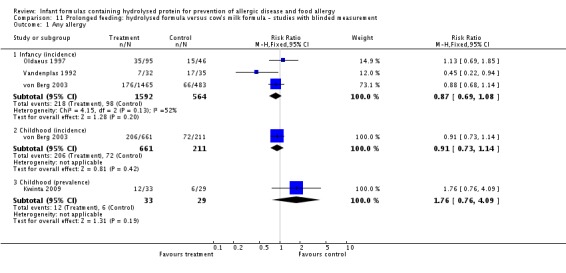

Meta‐analysis showed a reduction in infant allergy (eight studies, 2852 infants; fixed‐effect (FE) RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.95; RD ‐0.04, 95% CI ‐0.08 to ‐0.01; number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) 25, 95% CI 12.5 to 100; I² = 18%). Meta‐analysis revealed no difference in childhood allergy incidence (two studies, 950 infants; RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.05; heterogeneity P = 0.05; I² = 73%). One study (Kwinta 2009) reported no difference in childhood allergy prevalence (62 infants; RR 1.76, 95% CI 0.76 to 4.09). (See Figure 4 for funnel plot.)

Figure 4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 4 Prolonged feeding: hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula, outcome: 4.1 Any allergy.

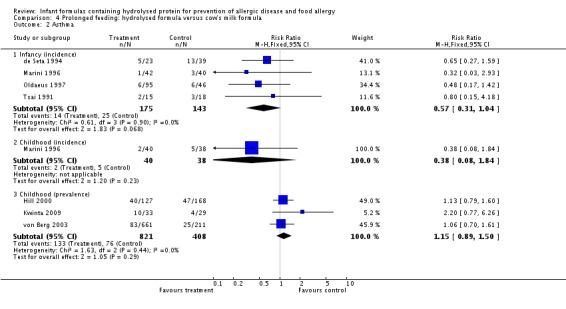

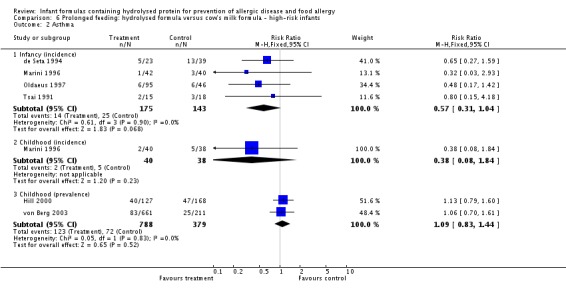

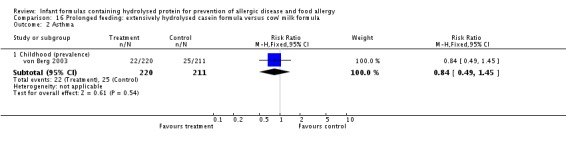

Meta‐analysis showed no difference in infant asthma (four studies, 318 infants; FE RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.31 to 1.04; I² = 0%). Marini 1996 reported no difference in childhood asthma incidence (78 infants; RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.08 to 1.84). Meta‐analysis revealed no difference in childhood asthma prevalence (three studies, 1229 infants; FE RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.50; I² = 0%).

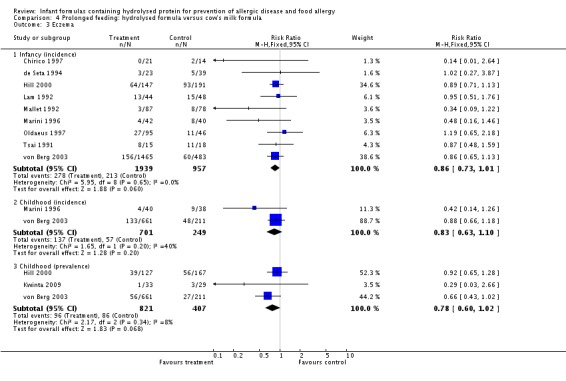

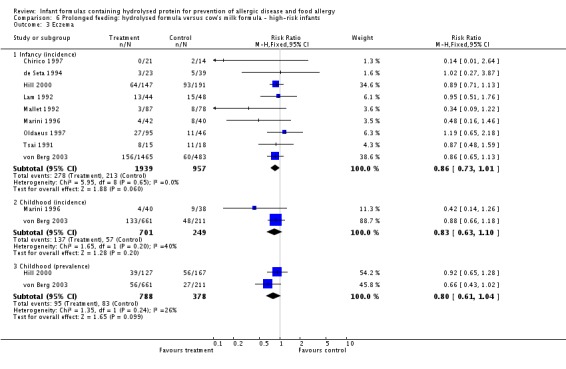

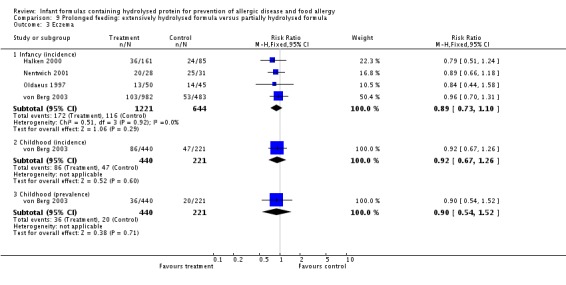

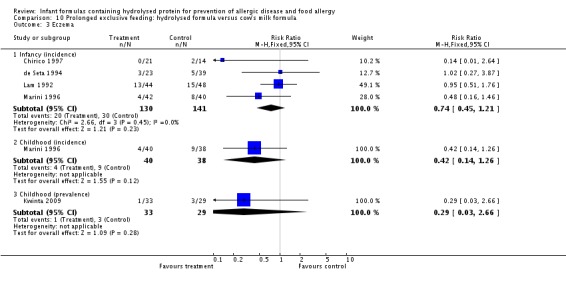

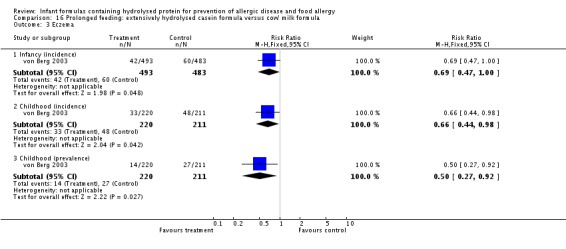

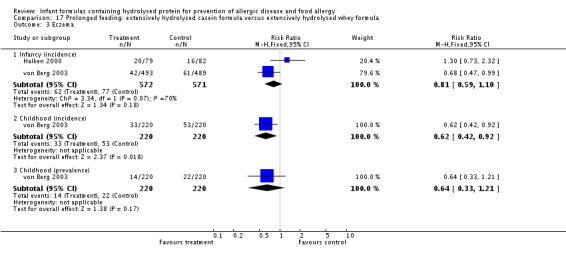

Meta‐analysis showed no difference in infant eczema (nine studies, 2896 infants; FE RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.01; heterogeneity P = 0.05; I² = 0%). Meta‐analysis showed no difference in childhood eczema incidence (two studies, 950 infants; FE RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.10; heterogeneity P = 0.20; I² = 40%). Meta‐analysis revealed no difference in childhood eczema prevalence (three studies, 1228 infants; FE RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.02; I² = 8%). (See Figure 5 for funnel plot.)

Figure 5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 4 Prolonged feeding: hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula, outcome: 4.3 Eczema.

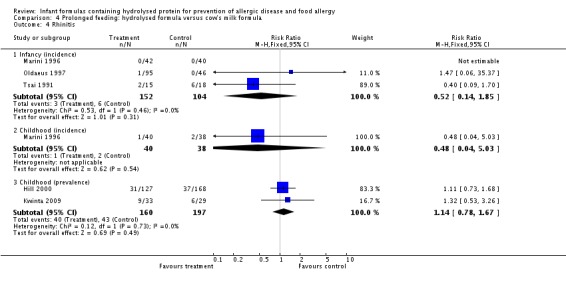

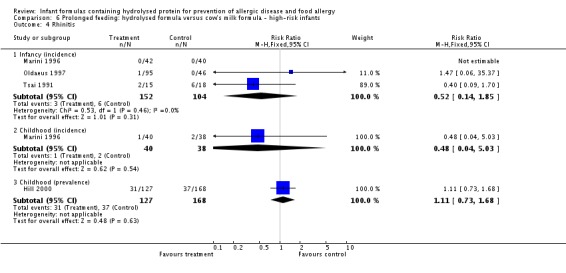

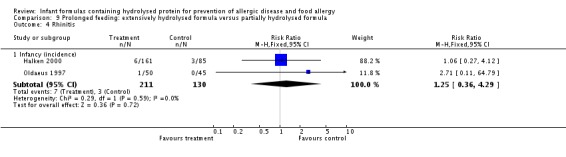

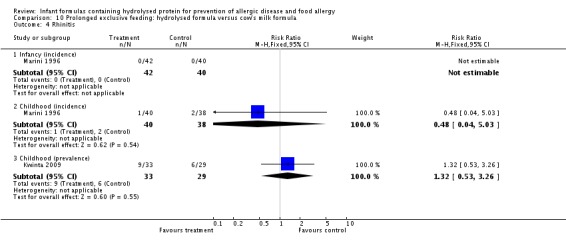

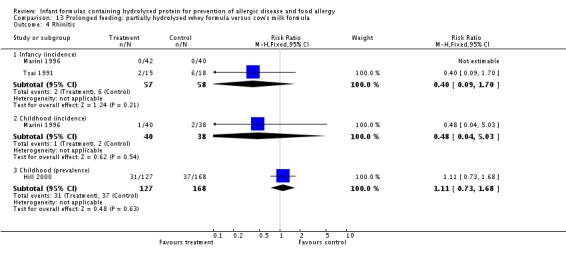

Meta‐analysis showed no difference in infant rhinitis (three studies, 256 infants; FE RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.14 to 1.85; I² = 0%). Marini 1996 reported no difference in childhood rhinitis incidence (78 infants; RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.04 to 5.03). Meta‐analysis revealed no difference in childhood rhinitis prevalence (two studies, 357 infants; FE RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.67; I² = 0%).

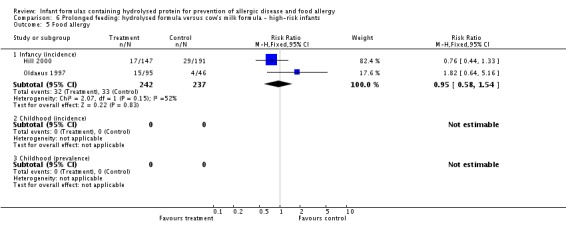

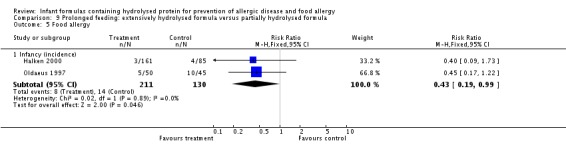

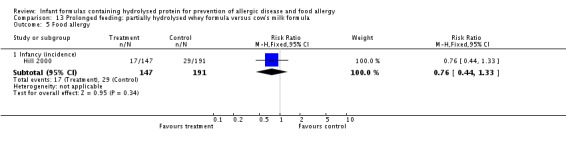

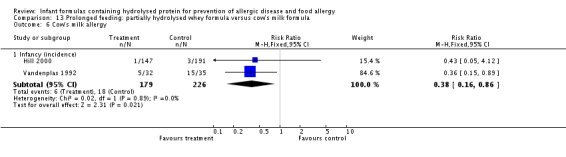

Meta‐analysis showed no difference in infant food allergy (two studies, 479 infants; FE RR 1.95, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.54; heterogeneity P = 0.15; I² = 52%). Meta‐analysis revealed a reduction in infant CMA (two studies, 405 infants; FE RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.86; I² = 0%). (See Figure 6 for funnel plot.)

Figure 6.

Funnel plot of comparison: 4 Prolonged feeding: hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula, outcome: 4.6 Cow's milk allergy.

Subgroup analyses (Comparisons 5 to 10)

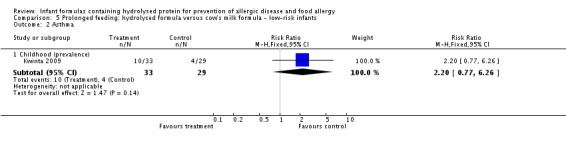

Comparison 5. Prolonged feeding: hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula ‐ low‐risk infants

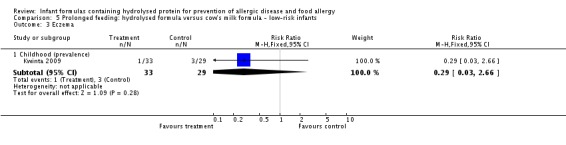

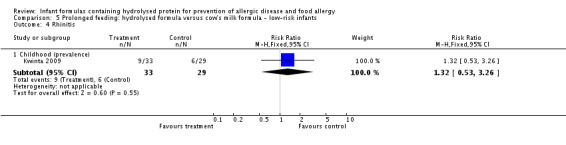

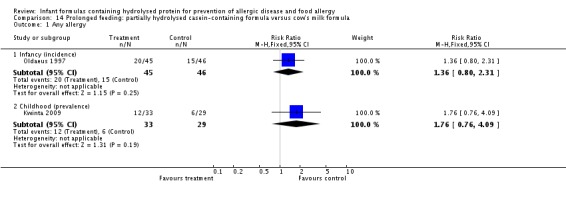

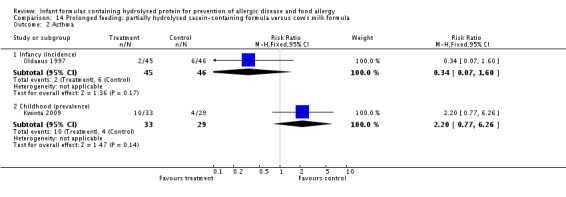

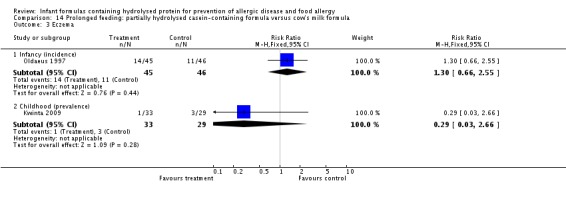

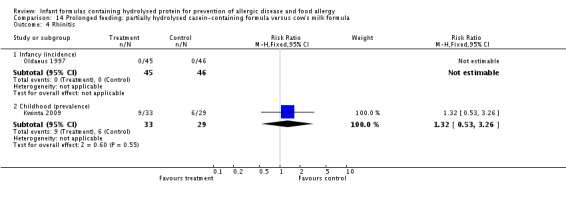

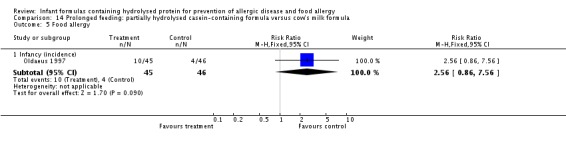

Kwinta 2009 compared prolonged feeding with a hydrolysed formula versus CMF in low‐risk infants. Kwinta 2009 reported no difference in childhood prevalence of allergy (62 infants; RR 1.76, 95% CI 0.76 to 4.09), asthma (62 infants; RR 2.20, 95% CI 0.77 to 6.26), eczema (62 infants; RR 0.29, 95% CI 0.03 to 2.66) and rhinitis (62 infants; RR 1.32, 95% CI 0.53 to 3.26).

Comparison 6. Prolonged feeding: hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula ‐ high‐risk infants

Eight studies (de Seta 1994; Hill 2000; Lam 1992; Marini 1996; Oldaeus 1997; Vandenplas 1992; von Berg 2003; Willems 1993) compared prolonged hydrolysed formula feeding versus CMF feeding in high‐risk infants.

Meta‐analysis showed a reduction in infant allergy incidence (eight studies, 2852 infants; FE RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.95; I² = 18%). Meta‐analysis revealed no difference in childhood allergy incidence (two studies, 950 infants; FE RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.05; heterogeneity P = 0.05; I² = 73%).

Meta‐analysis showed no difference in infant asthma incidence (four studies, 318 infants; FE RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.31 to 1.04; I² = 0%). Marini 1996 reported no difference in childhood asthma incidence (78 infants; RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.08 to 1.84). Meta‐analysis revealed no difference in childhood asthma prevalence (two studies, 1167 infants; RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.44; I² = 0%).

Meta‐analysis showed no difference in infant eczema incidence (nine studies, 2896 infants; FE RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.01; I² = 0%), no difference in childhood eczema incidence (two studies, 950 infants; FE RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.10) and no difference in childhood eczema prevalence (two studies, 1166 infants; FE RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.04; I² = 26%).

Meta‐analysis showed no significant difference in infant rhinitis incidence (three studies, 256 infants; FE RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.14 to 1.85; I² = 0%). Marini 1996 reported no difference in childhood rhinitis incidence (78 infants; RR 0.47, 95% CI 0.04 to 5.03). Hill 2000 found no difference in childhood rhinitis prevalence (295 infants; RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.68).

Meta‐analysis showed no difference in infant food allergy incidence (two studies, 479 infants; FE RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.54; heterogeneity P = 0.15; I² = 54%).

Meta‐analysis showed no difference in infant cow's milk allergy incidence (two studies, 405 infants; FE RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.86; I² = 0%).

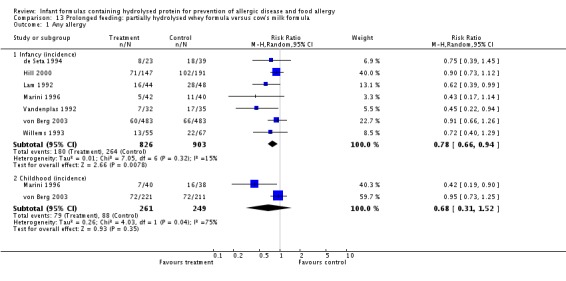

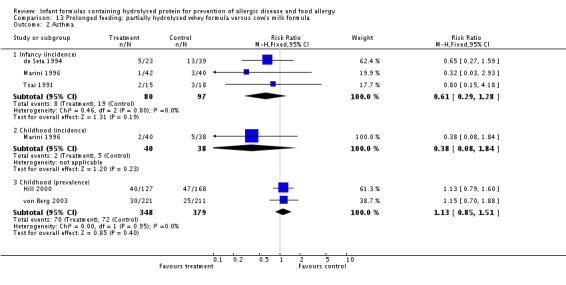

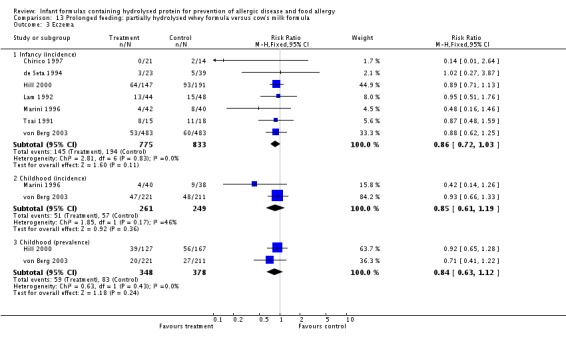

Comparison 7. Prolonged feeding: partially hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula

Eleven studies (Chirico 1997; de Seta 1994; Kwinta 2009; Hill 2000; Lam 1992; Marini 1996; Oldaeus 1997; Tsai 1991; Vandenplas 1992; von Berg 2003; Willems 1993) reported outcomes that compared prolonged feeding with a PHF versus a CMF.

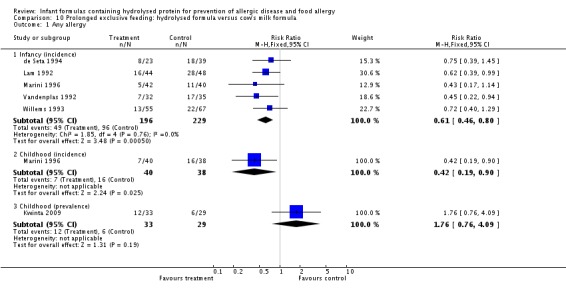

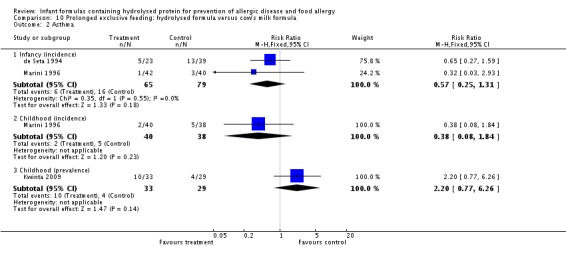

Meta‐analysis showed a reduction in infant allergy incidence (eight studies, 1820 infants; FE RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.96; RD ‐0.05, 95% CI ‐0.09 to ‐0.01; NNTB 20, 95% CI 11, 100; heterogeneity P = 0.16; I² = 33%) and no difference in childhood allergy incidence (two studies, 510 infants; FE RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.10; heterogeneity P = 0.04; I² = 75%). Marini 1996 reported a reduction in childhood allergy incidence (78 infants; RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.90), whereas von Berg 2003 found no difference (432 infants; RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.25).

Meta‐analysis showed no difference in infant asthma (four studies, 268 infants; FE RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.28 to 1.04; I² = 0%). Marini 1996 reported no difference in childhood asthma incidence (78 infants; RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.08 to 1.84). Meta‐analysis revealed no difference in childhood asthma prevalence (three studies, 789 infants; FE RR 1.20, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.58).

Meta‐analysis showed no difference in infant eczema (eight studies, 1699 infants; FE RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.06; I² = 0%), no difference in childhood eczema incidence (two studies, 510 infants; FE RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.19; heterogeneity P = 0.17; I² = 46%) and no difference in childhood eczema prevalence (three studies, 788 infants; FE RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.09; I² = 0%).

Meta‐analysis showed no difference in infant rhinitis (three studies, 206 infants; FE RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.09 to 1.70). Marini 1996 reported no difference in childhood rhinitis incidence (78 infants; RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.04 to 5.03). Meta‐analysis revealed no difference in childhood rhinitis prevalence (two studies, 257 infants; FE RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.67; I² = 0%).

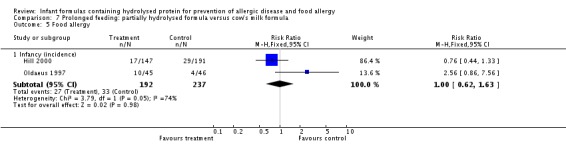

Meta‐analysis showed no difference in infant food allergy (two studies, 429 infants; FE RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.63; heterogeneity P = 0.05; I² = 74%). Neither study reported a difference.

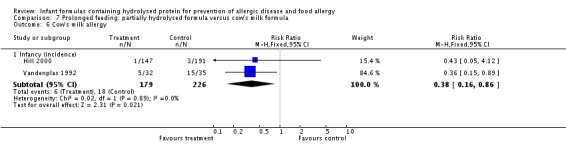

Meta‐analysis showed a reduction in infant CMA incidence (two studies, 405 infants; FE RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.86; I² = 0%).

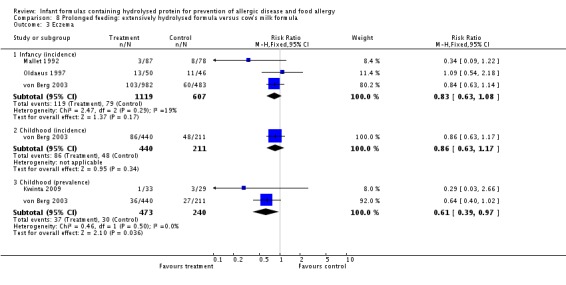

Comparison 8. Prolonged feeding: extensively hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula

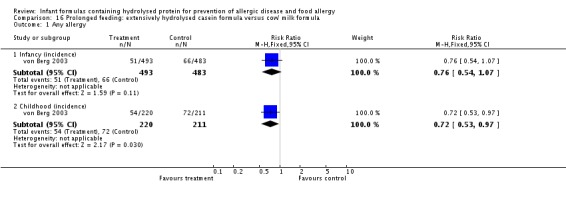

Five studies (Kwinta 2009; Mallet 1992; Oldaeus 1997; Sorensen 2007; von Berg 2003) compared prolonged feeding with an EHF versus CMF.

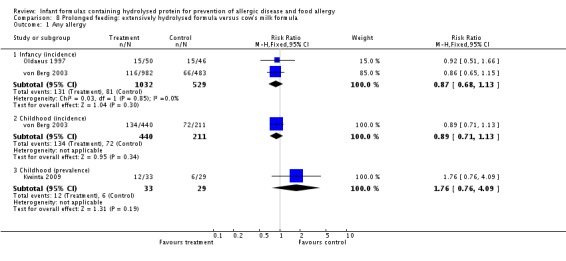

Meta‐analysis showed no difference in infant allergy (two studies, 1561 infants; FE RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.13; I² = 0%). von Berg 2003 reported no difference in childhood allergy incidence (651 infants; RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.13). Kwinta 2009 found no difference in childhood allergy prevalence (62 infants; RR 1.76, 95% CI 0.76 to 4.09).

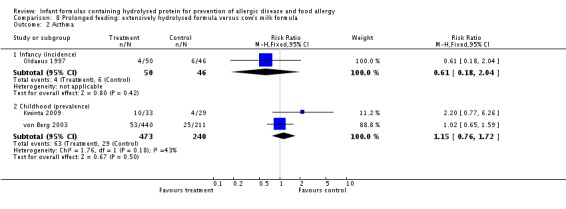

Oldaeus 1997 reported no difference in infant asthma (96 infants; RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.18 to 2.04). Meta‐analysis revealed no difference in childhood asthma prevalence (two studies, 713 infants; FE RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.72; heterogeneity P = 0.18, I² = 43%).

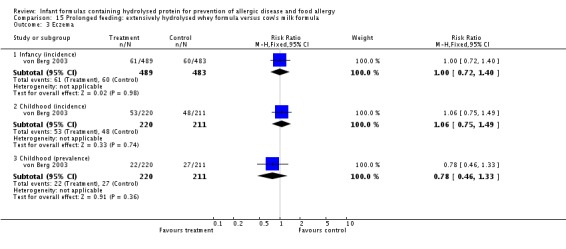

Meta‐analysis showed no difference in infant eczema (three studies, 1726 infants; FE RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.08). von Berg 2003 reported no difference in childhood eczema incidence (651 infants; RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.17). Meta‐analysis revealed a reduction in childhood eczema prevalence (two studies, 713 infants; FE RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.97; I² = 0%).

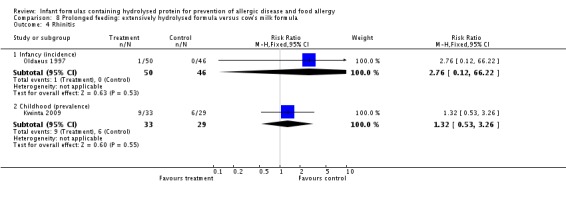

Oldaeus 1997 reported no difference in infant rhinitis incidence (96 infants; RR 2.76, 95% CI 0.12 to 66.22). Kwinta 2009 found no difference in childhood rhinitis prevalence (62 infants; RR 1.32, 95% CI 0.53 to 3.26).

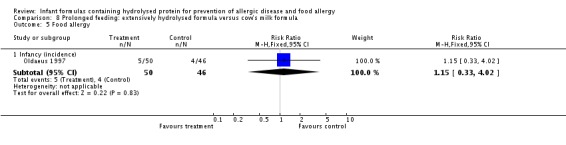

Oldaeus 1997 reported no difference in food allergy (96 infants; RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.33 to 4.02).

Comparison 9. Prolonged feeding: extensively hydrolysed formula versus partially hydrolysed formula

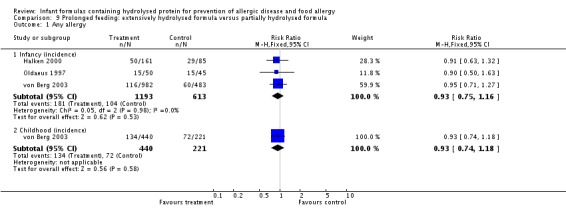

Five studies (Halken 2000; Nentwich 2001; Oldaeus 1997; Sorensen 2007; von Berg 2003) compared prolonged feeding with an EHF versus a PHF.

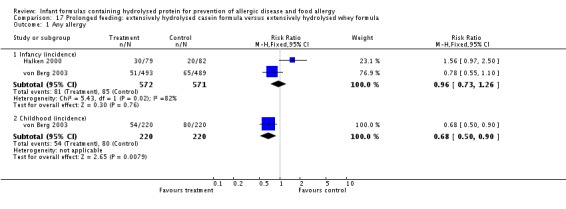

Meta‐analysis showed no difference in infant allergy (three studies, 1806 infants; FE RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.16; I² = 0%). von Berg 2003 reported no difference in childhood allergy incidence (661 infants; RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.35).

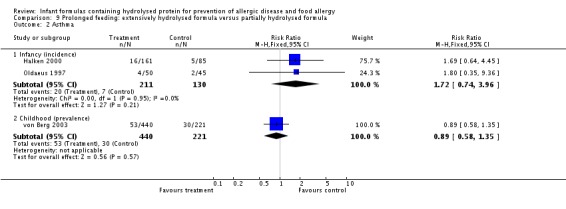

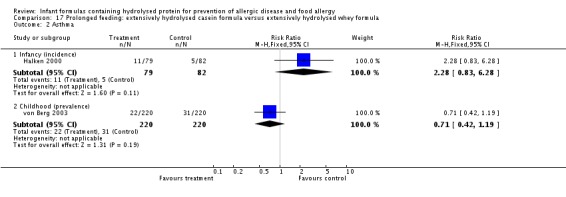

Meta‐analysis showed no difference in infant asthma incidence (two studies, 341 infants; FE RR 1.72, 95% CI 0.74 to 3.96; I² = 0%). von Berg 2003 reported no difference in childhood asthma prevalence (661 infants; RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.35).

Meta‐analysis showed no difference in infant eczema (four studies, 1865 infants; FE RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.10; I² = 0%). von Berg 2003 reported no difference in childhood eczema incidence (661 infants; RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.26) and no difference in childhood eczema prevalence (661 infants; RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.52).

Meta‐analysis revealed no difference in infant rhinitis (two studies, 341 infants; FE RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.36 to 4.29; I² = 0%).

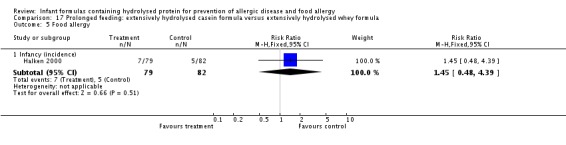

Meta‐analysis showed a reduction in infant food allergy (two studies, 341 infants; FE RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.19, 0.99; I² = 0%).

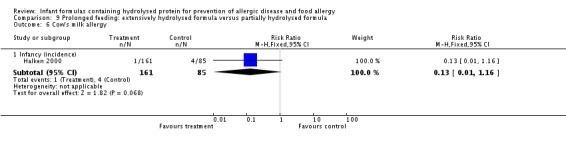

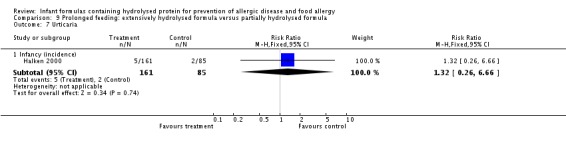

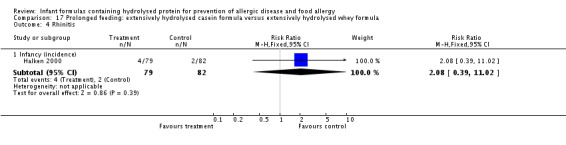

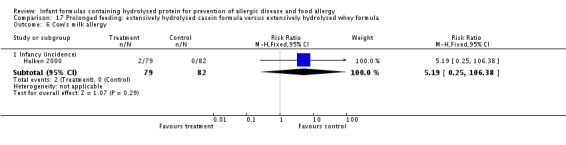

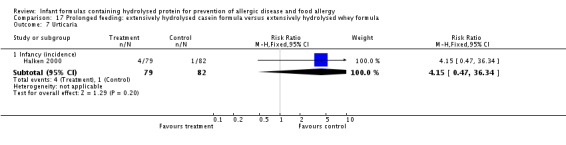

Halken 2000 reported no difference in infant CMA (246 infants; RR 0.13, 95% CI 0.01 to 1.16) and no difference in infant urticaria (246 infants; RR 1.32, 95% CI 0.26 to 6.66).

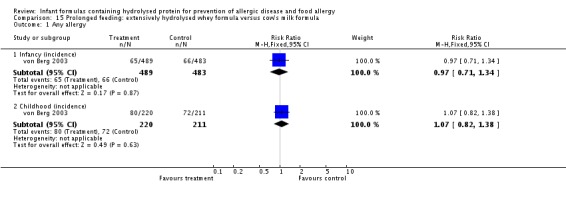

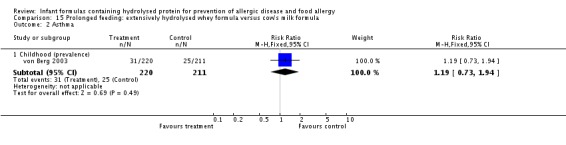

Comparison 10. Prolonged exclusive feeding: hydrolysed formula versus cow's milk formula