Abstract

Background

Chronic pain following mesh‐based inguinal hernia repair is frequently reported, and has a significant impact on quality of life. Whether mesh fixation with glue can reduce chronic pain without increasing the recurrence rate is still controversial.

Objectives

To determine whether tissue adhesives can reduce postoperative complications, especially chronic pain, with no increase in recurrence rate, compared with sutures for mesh fixation in Lichtenstein hernia repair.

Search methods

We searched the following electronic databases with no language restrictions: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; issue 4, 2016) in the Cochrane Library (searched 11 May 2016), MEDLINE Ovid (1986 to 11 May 2016), Embase Ovid (1986 to 11 May 2016), Science Citation Index (Web of Science) (1986 to 11 May 2016), CBM (Chinese Biomedical Database), CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure), VIP (a full‐text database in China), Wanfang databases. We also checked reference lists of identified papers (included studies and relevant reviews).

Selection criteria

We included all randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials comparing glue versus sutures for mesh fixation in Lichtenstein hernia repair. Cluster‐RCTs were also eligible.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors extracted data and assessed the risk of bias independently. Dichotomous outcomes were expressed as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Continuous outcomes were expressed as mean differences (MD) with 95% CIs.

Main results

Twelve trials with a total of 1932 participants were included in this review. The overall postoperative chronic pain in the glue group was reduced by 37% (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.91; 10 studies, 1418 participants, low‐quality evidence) compared with the suture group. However, the results changed when we conducted subgroup analysis with regard to the type of mesh. Subgroup analysis of included studies using lightweight mesh showed the reduction of chronic pain was less profound and insignificant (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.17). Subgroup analysis of included studies using heavyweight mesh resulted in a significant benefit from the fixation with glue (OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.82).

Hernia recurrence was similar between the two groups (OR 1.44, 95% CI 0.63 to 3.28; 12 studies, 1932 participants, low‐quality evidence). Fixation with glue was superior to suture regarding duration of the operation (MD −3.13, 95% CI −4.48 to −1.78; 9 studies, 1790 participants, low‐quality evidence); haematoma (OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.86; 10 studies, 1384 participants, moderate‐quality evidence); and recovery time to daily activities (MD −1.26, 95% CI −1.89 to −0.63; 3 studies, 403 participants, low‐quality evidence).

We also investigated adverse events. There were no significant differences between the two groups. For superficial wound infection pooled analyses showed OR 1.23, 95% CI 0.37 to 4.11; 7 studies, 763 participants (low‐quality evidence); for mesh/deep infection OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.16 to 2.83; 8 studies, 1393 participants (low‐quality evidence). Furthermore, we investigated seroma (a postoperative swelling caused by fluid) (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.33); and persisting numbness (OR 0.81, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.14).

Finally, six trials involving 1009 participants reported postoperative length of stay, resulting in non‐significant difference between the two groups (MD −0.12, 95% CI: −0.35 to 0.10)

Due to the lack of data, it was impossible to draw any distinction between synthetic glue and biological glue.

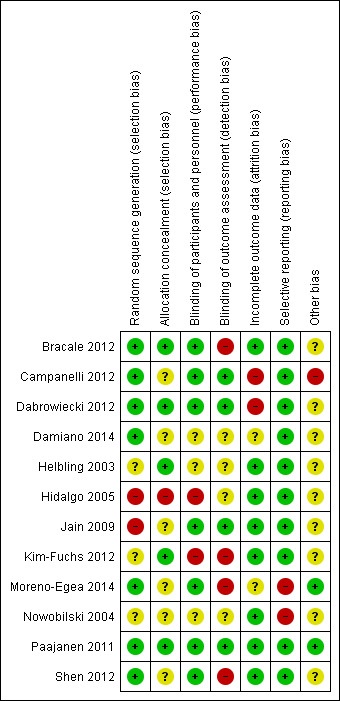

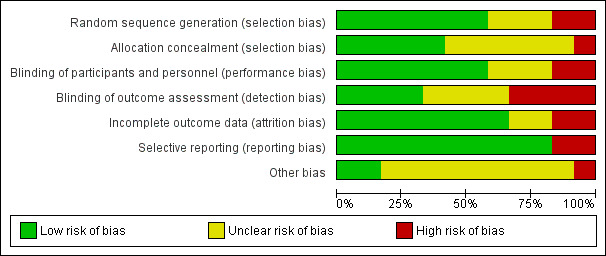

Eight out of 12 trials showed high risk of bias in at least one of the investigated domains. Two studies were quasi‐randomised controlled trials and the allocation sequence of one trial was not concealed. Nearly half of the included trials either did not provide adequate information or had high risk of bias regarding blinding processes. The risk of bias for incomplete outcome data of all the included studies varied from low to high risk of bias. Two trials did not report on some important outcomes. One study was funded by the manufacturer producing the fibrin sealant. Therefore, according to the 'Summary of findings' tables, the quality of the evidence (GRADE) for the outcomes is moderate to low.

Authors' conclusions

Based on the short‐term results, glue may reduce postoperative chronic pain and not simultaneously increase the recurrence rate, compared with sutures for mesh fixation in Lichtenstein hernia repair. Glue may therefore be a sensible alternative to suture for mesh fixation in Lichtenstein repair. Larger trials with longer follow‐up and high quality are warranted. The difference between synthetic glue and biological glue should also be assessed in the future.

Plain language summary

Glue may be a sensible alternative to suture for mesh fixation in Lichtenstein inguinal hernioplasty

Review question

We reviewed whether glue can reduce chronic pain after surgery, without increasing the postoperative recurrence rate, compared with sutures for mesh fixation in Lichtenstein inguinal hernia repair.

Background

A hernia is a weakness of the abdominal wall and allows escape of soft tissue or internal organs. It usually appears as a reducible lump and might cause discomfort and pain, limit daily activities, and affect quality of life. It can be life threatening if the bowel is ischemic or necrotic. Lichtenstein inguinal hernioplasty, which employs a synthetic mesh prosthesis to bridge the defect, is the standard open tension‐free repair of inguinal hernia. The recurrence rate of the Lichtenstein technique is acceptable. However, postoperative chronic pain is common and difficult to deal with. Suture is the traditional method for fixation of the mesh, but it may cause irritation or nerve compression which in turn leads to postoperative neuropathic pain. Therefore glue, as a non‐traumatic method for mesh fixation, is thought to reduce chronic pain. However, glue fixation might have an effect on the postoperative hernia recurrence rate.

Investigation

The Lichtenstein technique was first described in 1986, thus we searched the literature from 1986 to May 2016 for randomised controlled trials comparing glue versus sutures for mesh fixation in Lichtenstein hernia repair. We also considered studies including both primary and recurrent inguinal hernia when the report allowed us to separate the extraction of data on the primary repair.

Study characteristics

We identified 12 relevant randomised controlled trials comparing glue versus suture for fixation of the mesh, with a total of 1932 participants.

Main results

Glue fixation is superior to suture for the outcomes of chronic pain, duration of operation, haematoma and recovery time to daily activities.

Glue fixation is not associated with an increased risk of infection, hernia recurrence, seroma (a collection of fluid that builds up under the surface of the skin after surgery), persisting numbness (loss of sensation or feeling), quality of life, and postoperative length of stay.

We do not know the role of glue fixation in people with recurrent hernia, femoral hernia or complicated hernia. Meanwhile no conclusions could be drawn on which type of glue should be used because of lack of trials.

Quality of the evidence

Eight out of 12 trials showed high risk of bias in at least one of the investigated domains. Two studies were quasi‐randomised controlled trials. Nearly half of the included trials either did not provide adequate information or had high risk of bias regarding blinding processes. The risk of bias for incomplete outcome data of all the included studies is low to high. Two trials did not report on some important outcomes. One study was funded by the manufacturer producing the fibrin sealant. As the quality of the evidence (GRADE) for the outcomes is moderate to low and the results of chronic pain is not robust, the findings should be interpreted with caution.

However, the evidence is still sufficient to conclude that glue fixation of mesh for the Lichtenstein procedure is comparable, if not superior, to fixation with suture. Glue may be a sensible alternative to suture for mesh fixation in Lichtenstein repair.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Glue versus suture for recurrence and pain in Lichtenstein inguinal hernioplasty.

| Glue versus suture for recurrence and pain in Lichtenstein inguinal hernioplasty | |||||

|

Patient or population: patients with recurrence and pain in Lichtenstein inguinal hernioplasty

Settings:

Intervention: Fixation with glue Comparison: Fixation with suture | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Corresponding risk | |||||

| Glue versus suture | |||||

| Chronic pain Follow‐up: 3 to 60 months | Study population | OR 0.63 (0.44 to 0.91) | 1473 (10 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | |

| 71 per 1000 (51 to 99) | |||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 74 per 1000 (53 to 103) | |||||

| Hernia recurrence Follow‐up: 3 to 60 months | Study population | OR 1.44 (0.63 to 3.28) | 1987 (12 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2,4 | |

| 13 per 1000 (6 to 28) | |||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Duration of operation (mins) Follow‐up: 4.7 to 60 months | The mean duration of operation (mins) in the intervention groups was 0.37 standard deviations lower (0.52 to 0.23 lower) | 1790 (9 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,5 | ||

| Wound/superficial infection Follow‐up: 3 to 15 months | Study population | OR 1.23 (0.37 to 4.11) | 818 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2,4 | |

| 12 per 1000 (4 to 39) | |||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Mesh/deep infection Follow‐up: 3 to 60 months | Study population | OR 0.67 (0.16 to 2.83) | 1448 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2,4 | |

| 5 per 1000 (1 to 19) | |||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Haematoma Follow‐up: 3 to 60 months | Study population | OR 0.52 (0.31 to 0.86) | 1439 (10 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| 34 per 1000 (21 to 55) | |||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 35 per 1000 (21 to 56) | |||||

| Recovery time to daily activities (days) Follow‐up: 4.7 to 16.7 months | The mean recovery time to daily activities (days) in the intervention groups was 0.81 standard deviations lower (1.05 to 0.58 lower) | 403 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1 The risk of bias of most included studies is moderate or high. 2 Total number of events is less than 300.

3 The number of trials was too few to assess inconsistency.

4 Imprecision of results (wide confidence intervals).

5Unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency of results.

Background

Description of the condition

Inguinal (groin) hernia repair is one of the most frequent operations in general surgery. Rutkow 2003 reports 800,000 groin hernia repairs in the US in 2003. The Lichtenstein technique, first described in 1986 (Lichtenstein 1986), is the standard open tension‐free method of inguinal hernia repair and is used worldwide. In this method, a synthetic mesh is placed over the defect so that the hernia is repaired without the need to pull the tissues together under tension. The advantages of this procedure are that it is technically easy, associated with lower recurrence rates, has shorter recovery times compared with tension repair (Grant 2002; Nordin 2002), and can be performed using local anaesthesia as a day procedure. However, postoperative chronic pain is frequently reported following mesh‐based inguinal hernia repair, from 11.0% to as high as 40.5% (Eklund 2010; MRC Group 1999; Nienhuijs 2007; Nikkolo 2012; Paajanen 2002; Willaert 2012), and has a significant impact on quality of life (van Hanswijck de Jonge 2008). It is difficult to overcome this problem, as surgery and the use of additional local analgesics have not shown a clear benefit to those treated (Nienhuijs 2007).

Description of the intervention

Sutures are generally used to secure the prosthetic mesh but may contribute to chronic pain or other problems, such as numbness or groin discomfort, presumably through irritation or nerve compression (Heise 1998). This has prompted the development of less traumatic means of mesh fixation. The original technique for fixation of mesh in Lichtenstein hernioplasty used non‐absorbable sutures. Since then, other surgeons have described using absorbable sutures (Paajanen 2002), various tissue adhesives (Canonico 2005), or novel self‐fixing meshes (Kapischke 2010). Fibrin glue and N‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate are two of the most commonly used products for mesh fixation. Fibrin glue is a bio‐degradable adhesive that combines human‐derived fibrinogen and thrombin. In addition to its haemostatic action, the fibrinogen component gives the product tensile strength and adhesive properties (Katkhouda 2001), as well as promoting fibroblast proliferation (Zieren 1999). N‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate is a new generation of cyanoacrylate that has been used as a surgical tissue adhesive since the 1960s, polymerizing at room temperature, and resulting in lower toxicity and fewer inflammatory reactions compared to cyanoacrylate (Levrier 2003; Montanaro 2001).

How the intervention might work

Tissue adhesives aim to reduce chronic neuropathic pain and simultaneously speed up the surgical procedure. Because the possibility of trapping nerves with suturing is eliminated, direct nerve irritation is reduced. Therefore, mesh fixation with glue (tissue adhesive) seems to be an optimal choice to reduce postoperative chronic pain. However, there may be increased recurrence associated with glue fixation.

Why it is important to do this review

As inguinal hernia repair is performed so frequently and is often associated with postoperative chronic pain, even relatively modest improvements in clinical outcomes would have a significant medical and economic impact. If a reduction of postoperative chronic pain without affecting the recurrence rate can be demonstrated by fixation with tissue adhesives (glue), compared to mesh fixation with sutures, this may support change in current surgical practice. However, there is concern of increased recurrence associated with glue fixation because the fibrin glue is fully absorbed within two weeks of application (Petersen 2004). Several randomised trials and observational studies have compared the two methods (Campanelli 2012; Helbling 2003; Paajanen 2011), but consensus regarding which method is better has not been reached. Thus, a thorough and systematic evaluation of the use of mesh fixation with glue would be welcomed to support the ongoing discussions.

Objectives

To determine whether tissue adhesives can reduce postoperative complications, especially chronic pain, with no increase in recurrence rate, compared with sutures for mesh fixation in Lichtenstein hernia repair.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered for inclusion randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing glue versus sutures for mesh fixation in Lichtenstein hernia repair. Cluster‐RCTs were also eligible. We also considered studies including both primary and recurrent inguinal hernia if data on primary repair were reported separately. We included trials in any language.

Types of participants

Adults (at least 18 years of age) undergoing Lichtenstein hernia repair for primary inguinal hernia (direct and indirect), unilateral as well as bilateral. We excluded participants with femoral hernias.

Types of interventions

Lichtenstein hernia repair with mesh fixation by:

glue (tissue adhesive); or

sutures.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Chronic pain: pain persisting beyond three months postoperatively.

Hernia recurrence: clinically or radiologically diagnosed. We will use any time point reported by the authors, as there is no standard and widely accepted method to differentiate between recurrence and a new hernia that can be prespecified.

Secondary outcomes

Duration of operation (minutes).

Wound/mesh infection.

Haematoma/seroma.

Persistent numbness: numbness in the groin or testicle persisting beyond three months postoperatively.

Postoperative length of stay (days).

Recovery time to daily activities (walking, driving, manual work) (days)

Quality of life

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Lichtenstein technique was first described in 1986, thus searches were limited to publications from 1986 to 11 May 2016. The following electronic databases were searched with no language or publication restrictions.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2016, Issue 4) in the Cochrane Library (searched 11 May 2016) (Appendix 1).

MEDLINE Ovid (January 1986 to 11 May 2016) (Appendix 2).

EMBASE Ovid (January 1986 to 11 May 2016) (Appendix 3).

Science Citation Index (Web of Science) (January 1986 to 11 May 2016) (Appendix 4).

CBM (Chinese Biomedical Database) (Appendix 5).

CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure) (Appendix 6).

VIP (a full‐text database from China) (Appendix 7).

Wanfang databases (Appendix 8).

Searching other resources

We contacted experts in the field for information about any further completed and ongoing trials. Relevant websites were searched and reference lists of all the included studies were checked for additional studies suitable for inclusion.

We searched the following trial registers.

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov).

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/en/).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (SP and CX) independently assessed all abstracts identified by the search strategies and excluded studies that were clearly not relevant. We obtained the full‐text publications of all possibly relevant abstracts and formally assessed them for inclusion. Eligible studies were included irrespective of whether measured outcome data were reported. Review authors were not blinded to the names of the authors, their institutions, the journal of publication or the results. We resolved any disagreements by discussion or a third review author (SY) acted as arbiter. We also listed the excluded trials and the reasons for their exclusion.

Data extraction and management

A data extraction form was developed and two review authors (SP and DS) independently extracted data and completed these forms. Data on the following were extracted.

Study Information: study identification, first author, country, year of publication.

Methods of the study: study design, method of randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding.

Participants: setting, country, enrolment dates, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, age, sex, body mass index (where documented), activities (i.e. job, sport, hobbies), health status (i.e. chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, constipation, prostatism), details of hernia (type and size, unilateral/bilateral), total number of participants originally assigned to each intervention group.

Intervention: material for fixation.

Duration of follow‐up.

Outcomes: chronic pain, recurrence, length of operation (minutes), haematoma/seroma, wound infection, mesh infection, persistent numbness, postoperative hospital length of stay (days), recovery time (days) to achieving normal daily activities (walking, driving, manual work), quality of life.

Routine prophylactic use of perioperative antibiotics.

Economic aspects.

Other technical details: type of mesh, overlap to the pubic tubercle, fixation locations, handling of nerves.

Where a difference of opinion arose between authors, it was resolved through discussion with a third review author (HQ). We contacted study authors to request missing or updated information.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed all studies that met the inclusion criteria for methodological quality, as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Two review authors (SP and CX) independently assessed the risk of bias of included studies and a third review author (SY) resolved disagreements where necessary.

We assessed the following risk of bias domains.

Random sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding of participants and personnel.

Blinding of outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective reporting. and

Other bias (sample size calculation, differences at baseline between allocation groups, registered in trial database and funds from industry).

We judged each domain as low, high or unclear risk of bias according to criteria stated in the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (see Appendix 9) (Chapter 8.5.d, Higgins 2011).

We classified trials as low risk of bias if none of the domains were associated with unclear or high risk of bias. Otherwise, the trials were classified as moderate or high risk of bias (one of the domains has unclear risk of bias or one of the domains has high risk of bias, respectively).

We searched for the protocols of studies included in the review using electronic databases, or by contacting the authors of the respective studies. If we suspected selective reporting, we contacted the study authors for clarification.

Measures of treatment effect

We analysed the data using Cochrane's Review Manager 5 (RevMan) computer program (RevMan 2012), following recommendations from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Dichotomous outcomes were expressed as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Continuous outcomes were expressed as mean differences (MD) with 95% CI.

Unit of analysis issues

If people randomised had bilateral hernias and each hernia received the same intervention, the number of participants was used as the denominator in the analysis. One trial treated each hernia in people with bilateral hernias with a different method of fixation, therefore the number of hernias was used as the denominator in the analysis. All included studies were parallel in design, and we did not identify any cluster‐RCTs, hence the unit of analysis was the participant or the hernia.

Dealing with missing data

Where essential data were missing, insufficient or unclear, we attempted to contact study authors for further information. The current update reported data from original studies regardless of whether intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis was employed by the authors of the included studies. If data were missing due to participants dropping out of the studies, and being unable to receive any information on reasons from the primary authors, we conducted an intention‐to‐treat analysis and treated dropouts as successful rehabilitation when they occurred. For those data derived from completers only, we conducted best/worst case scenario sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of missing data on the estimates of effect (Analysis 2.1; Analysis 2.2).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Glue versus suture: worst case scenarios, Outcome 1 Chronic pain.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Glue versus suture: worst case scenarios, Outcome 2 Hernia recurrence.

Assessment of heterogeneity

First, we assessed the clinical diversity among the included studies, focusing on the participants, interventions, and measurement of outcomes.

Second, we judged methodological diversity in terms of variability in study design and risk of bias. We assessed statistical heterogeneity using the Chi² test (significance set at P < 0.1) and I² statistic (0% to 40%: might not be important; 30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity; 75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity) as guided by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2002; Higgins 2011).

Data synthesis

Where appropriate, for dichotomous outcomes we pooled data in meta‐analyses using the Mantel‐Haenszel approach (fixed‐effect model); and for continuous outcomes we used the inverse variance method (fixed‐effect model). If homogeneity between studies was deemed invalid (with substantial or considerable heterogeneity), a random‐effects model was adopted instead after exploring the causes of heterogeneity. We used the RevMan software (RevMan 2012) to analyse the data.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We intended to perform the following subgroup analyses.

Synthetic glue versus sutures.

Biological glue versus sutures.

Synthetic glue versus biological glue.

Lightweight mesh versus heavyweight mesh.

Due to lack of data, we were not able to perform the synthetic glue versus biological glue subgroup analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned sensitivity analyses to explore the influence of the following factors on effect size.

Repeating the analysis taking into account risk of bias of the studies, i.e. removing those that at least one criterion classified as high or unclear risk of bias as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Only Paajanen 2011 was considered to be at an overall low risk of bias.

Repeating the analysis removing the hernia level trial, Hidalgo 2005, in order to get the patient level result.

Summary of findings

We assessed the quality of the evidence for recurrence and chronic pain for glue versus suture following Lichtenstein inguinal hernioplasty using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach (Schünemann 2011) in the 'Summary of findings' table.

The GRADE system classifies the quality of evidence in one of four grades:

| Grade | Definition |

| High | Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect |

| Moderate | Further research is likely to have an impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate |

| Low | Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate |

| Very low | Any estimate of effect is very uncertain |

Factors that influence the quality of evidence:

| Downgrades the evidence | Upgrades the evidence for non‐randomised trials |

| Study limitation | Large magnitude of effect |

| Inconsistency of results | All plausible confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect |

| Indirectness of evidence | Dose‐response gradient |

| Imprecision | |

| Publication bias |

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

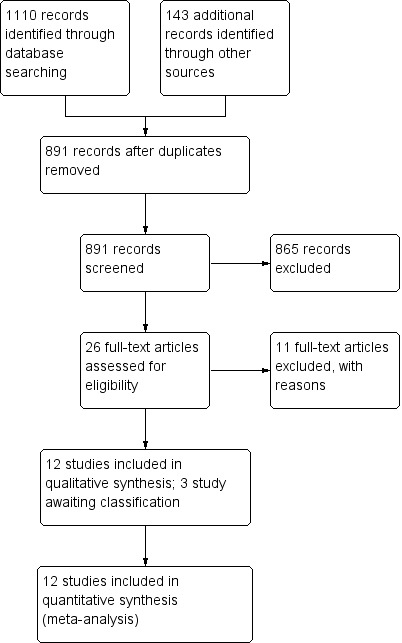

The study screening process is shown in Figure 1. For duplicated publications, only the most recent or the most complete report was included. There were 1253 publications, including 1110 records identified through database searching and 143 additional records identified through other sources. From these, 362 duplicates were removed. From the remaining 891 publications, 865 records were excluded due to non‐randomised designs or lack of relevance to our topic. We assessed the full‐text versions of the remaining 26 publications. Two publications were excluded because they were found to be duplicated publications and nine did not meet our inclusion criteria (see Excluded studies section, below). Finally, from the remaining 15 publications, 12 trials were included in the quantitative synthesis (meta‐analysis) and 3 studies are awaiting classification.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Ten RCTs and two quasi‐RCTs — Hidalgo 2005 and Jain 2009 — were included in this systematic review; one of the quasi‐RCTs used within‐patient allocation in people with bilateral hernia. No cluster‐RCTs were identified. The detailed information of the included trials is presented in the Characteristics of included studies table. All the included trials were published in English.

Eight studies applied synthetic glue for mesh fixation, while the other four — Hidalgo 2005, Bracale 2012, Campanelli 2012 and Damiano 2014 — used biological glue. A total of 1932 participants were included in this systematic review, among which 970 were in glue groups and 1017 in suture groups. Most of the participants were male, with six studies including only males (Campanelli 2012; Dabrowiecki 2012; Hidalgo 2005; Jain 2009; Kim‐Fuchs 2012; Nowobilski 2004).

The average follow‐up period in nine of the 12 included studies was similar, at 12 to 17 months; follow‐up was less than five months in two studies (Helbling 2003; Nowobilski 2004), and about five years in another (Kim‐Fuchs 2012). Eight of the included studies tried their best to identify and preserve the nerves in the inguinal region; Helbling 2003 resected the nerves of most of the participants and in three studies this information was not clear (Damiano 2014; Hidalgo 2005; Jain 2009).

Excluded studies

See: Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Three studies did not have randomised allocations of glue and suture (Negro 2011; Shen 2011; Sözen 2012), two trials reported data already included in Campanelli 2012 (Campanelli 2008; Campanelli 2014), three trials were not controlled studies and included people who underwent plug and mesh procedures other than Lichtenstein (Eldabe Mikhail 2012; Lionetti 2012; Testini 2010), and in three studies the intervention and control groups received different kinds of mesh (Arslani 2010; Stabilini 2010; Torcivia 2011).

Risk of bias in included studies

The results of the 'Risk of bias' assessments are summarised graphically (Figure 2, Figure 3).

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Two included studies are quasi‐randomised trials. In Hidalgo 2005, on the right side polypropylene sutures were used, while on the left, attachment was done using glue. In Jain 2009, participants were alternately assigned to one of two groups. For the 10 randomised trials, six reported specific method of randomisation (Bracale 2012; Campanelli 2012; Dabrowiecki 2012; Damiano 2014; Moreno‐Egea 2014; Shen 2012); but only five studies reported the method of allocation concealment (by sealed envelope) (Bracale 2012; Dabrowiecki 2012; Helbling 2003; Kim‐Fuchs 2012; Paajanen 2011).

Blinding

Both the participants and outcome assessment were blinded in four studies (Campanelli 2012; Dabrowiecki 2012; Jain 2009; Paajanen 2011). In Shen 2012, Bracale 2012 and Moreno‐Egea 2014, only the participants were blinded. In Helbling 2003, Damiano 2014 and Nowobilski 2004, the blinding was not clear. In Hidalgo 2005, the participants were not blinded and the blinding of outcome assessors was not clear. For Kim‐Fuchs 2012, neither the participants nor the outcome assessors were blinded.

Incomplete outcome data

Attrition bias was not clear in two trials (Damiano 2014; Moreno‐Egea 2014). In Helbling 2003, Nowobilski 2004, Hidalgo 2005, Jain 2009 and Shen 2012, the outcome data were complete. The proportion of missing outcomes was comparable between two groups, or was not big enough to have a clinically relevant impact on the intervention effect estimate, in Paajanen 2011, Kim‐Fuchs 2012 and Bracale 2012. Attrition bias was high in two trials (Campanelli 2012; Dabrowiecki 2012).

Selective reporting

Nowobilski 2004 reported pain within seven days, which did not meet our definition of chronic pain. Moreno‐Egea 2014 did not report the result of time required to return to normal activities (days) as they planned in the study protocol. The remaining 10 studies reported both primary outcomes of this review. For most of the studies there was no protocol.

Other potential sources of bias

The potential conflict of interest and source of funding was described in three trials (Campanelli 2012; Moreno‐Egea 2014; Paajanen 2011). For Paajanen 2011 the source of funding was a hospital research grant, free from financial or material support from any commercial company, thus judged to be free from risk of 'source of funding' bias. The study by Campanelli 2012 was funded by Baxter Healthcare, which is a manufacturer producing fibrin sealant; thus we consider this trial to be at high risk of 'source of funding' bias. In the Moreno‐Egea 2014 study, the authors declared no potential conflicts of interest and no financial support. The remaining included trials did not declare any source of funding.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

See: Data and analyses.

All 12 studies available for classification were included in quantitative synthesis (meta‐analysis).

1. Primary outcomes

1.1 Chronic postoperative pain

Ten trials, with a total of 1418 participants reported the number of people with chronic pain (at least 3 months postoperatively; follow‐up 3 to 60 months). There was an overall reduction of chronic pain by 37% (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.91, low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.1) with fibrin glue. There was no significant heterogeneity (I² = 37%, P = 0.12).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glue versus suture, Outcome 1 Chronic pain.

For subgroup analyses based on the type of glue used, there was no statistically significant difference between the synthetic glue group and the suture group (OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.04; Analysis 1.1.1) with moderate heterogeneity (I² = 48%, P = 0.07). The biological glue group also had less chronic pain (OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.20 to 1.03; Analysis 1.1.2) with no statistical heterogeneity (I² = 0, P = 0.83), but the difference was not statistically significant.

After we only included studies that used lightweight mesh (Bracale 2012; Helbling 2003; Kim‐Fuchs 2012; Moreno‐Egea 2014; Paajanen 2011; Shen 2012), the result of chronic pain became less profound and statistically insignificant (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.17). However, when we only included studies using heavyweight mesh (Campanelli 2012 and Jain 2009), a significant and more profound benefit from the fixation with glue regarding the outcome chronic pain was observed (OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.82).

When trials with at least one risk of bias criterion classified as unclear or high were removed from the analysis, this left only Paajanen 2011, which showed no statistically significant difference between the two groups (OR 1.39, 95% CI 0.76 to 2.56). When the hernia level trial was removed (Hidalgo 2005), none of the results changed.

Three studies did not present specific information of dropouts (Dabrowiecki 2012; Damiano 2014; Moreno‐Egea 2014). We conducted a worst case scenario analysis with the data of the four studies reporting dropouts (Bracale 2012; Campanelli 2012; Kim‐Fuchs 2012; Paajanen 2011), and found that none of the results changed (OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.02 for synthetic glue versus suture; OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.05 for biological glue versus suture; and OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.91 for glue versus suture; Analysis 2.1).

1.2 Postoperative hernia recurrence

All twelve included trials, with a total of 1932 participants, reported the primary outcome 'hernia recurrence' (follow‐up 3 to 60 months), with a median length of follow‐up just less than 17 months. One could argue whether a hernia is new or whether it is a recurrent one, but so far there is no standard and widely accepted method to differentiate between recurrence and a new hernia. Seven of the trials reported no recurrence events in either group. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (OR 1.44, 95% CI 0.63 to 3.28, low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.2) with no statistical heterogeneity (I² = 0, P = 0.84). Subgroup analyses also showed no statistically significant difference between the suture group and the synthetic glue (OR 1.58, 95% CI 0.62 to 4.05, P = 0.34; Analysis 1.2.1; five of the eight trials reported no recurrence in either group) or biological glue (OR 1.02, 95% CI 0.17 to 5.90, P = 0.99; Analysis 1.2.2; two of the four trials reported no recurrence in either group).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glue versus suture, Outcome 2 Hernia recurrence.

When we only included studies that used lightweight mesh (Bracale 2012; Helbling 2003; Kim‐Fuchs 2012; Moreno‐Egea 2014; Paajanen 2011; Shen 2012), the result of recurrence remained unchanged (OR 1.58, 95% CI 0.62 to 4.04). When we only included studies using heavyweight mesh (Campanelli 2012 and Jain 2009), there was also no statistically significant difference between the two groups (OR 0.50, 95% CI 0.04 to 5.54). When the hernia level trial was removed (Hidalgo 2005), none of the results changed.

As for the previous outcome 'postoperative chronic pain', we conducted a worst case scenario analysis which confirmed the robustness of the results (OR 1.31, 95% CI 0.84 to 2.04 for synthetic glue versus suture; OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.19 to 2.40 for biological glue versus suture; and OR 1.22, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.85 for glue versus suture; Analysis 2.2).

2. Secondary outcomes

2.1 Duration of operation

Nine trials, with a total of 1790 participants, reported duration of operation in minutes. The glue group had a shorter duration of operation (MD −3.13, 95% CI −4.48 to −1.78, low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.3). Test for heterogeneity was significant (I² = 60%, P = 0.01). Subgroup analyses showed that both the synthetic glue group and the biological glue group had shorter durations of operation than the suture group (MD −3.67, 95% CI −6.10 to −1.24 and MD −2.72, 95% CI −3.67 to −1.77, respectively; Analyses 1.3.1 and 1.3.2).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glue versus suture, Outcome 3 Duration of operation (mins).

2.2 Wound/superficial infection

Seven trials, with a total of 763 participants, reported this outcome (follow‐up 3 to 15 months). There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (OR 1.23, 95% CI 0.37 to 4.11, low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.4) with no statistical heterogeneity (I² = 0, P = 0.38). As the only trials that reported any events were those comparing synthetic glue with sutures, the pooled result was the same for this subgroup (Analysis 1.4.1).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glue versus suture, Outcome 4 Wound/superficial infection.

2.3 Mesh/deep infection

Eight trials, with a total of 1393 participants, reported this outcome (follow‐up 3 to 60 months). There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.16 to 2.83, low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.5). Subgroup analyses also showed no statistically significant differences between the synthetic or biological glue group and the suture group (OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.06 to 16.14 and OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.11 to 3.19, respectively; Analyses 1.5.1 and 1.5.2).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glue versus suture, Outcome 5 Mesh/deep infection.

2.4 Haematoma

Ten trials, with a total of 1384 participants, reported on the incidence of haematoma (follow‐up 3 to 60 months). The glue group had fewer haematomas than the suture group (OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.86, moderate‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.6) with no statistical heterogeneity (I² = 0, P = 0.78). Subgroup analyses showed that the synthetic glue group also had fewer haematomas than the suture group (OR 0.54, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.91; Analysis 1.6.1). However, there was no statistically significant difference between the biological glue group and the suture group (OR 0.33, 95% CI 0.05 to 2.13; Analysis 1.6.2).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glue versus suture, Outcome 6 Haematoma.

2.5 Seroma

Seroma is a swelling caused by fluid that builds up under the surface of the skin, and may develop after a surgical procedure. Eight trials involving 1184 participants reported this outcome (follow‐up 3 to 16.7 months). There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.33; Analysis 1.7) with no statistical heterogeneity (I² = 0, P = 0.89). Subgroup analyses also showed no statistically significant differences between the synthetic or biological glue group and the suture group (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.14 to 4.02 and OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.37, respectively; Analyses 1.7.1 and 1.7.2).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glue versus suture, Outcome 7 Seroma.

2.6 Persisting numbness

Only four trials, with a total of 728 participants, reported this outcome (follow‐up 3 to 60 months). There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (OR 0.81, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.14; Analysis 1.8) with no statistical heterogeneity (I² = 0, P = 0.49). Subgroup analyses also showed no statistically significant differences between the synthetic or biological glue group and the suture group (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.32 and OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.31, respectively; Analyses 1.8.1 and 1.8.2).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glue versus suture, Outcome 8 Persisting numbness.

2.7 Postoperative length of hospital stay

Six trials, with a total of 1009 participants, reported this outcome. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (MD −0.12, 95% CI −0.35 to 0.10; Analysis 1.9) with moderate heterogeneity (I² = 51%, P = 0.10). In Nowobilski 2004, the glue group had shorter postoperative length of hospital stay (MD −0.50, 95% CI −0.85 to −0.15). But the cause of heterogeneity was unknown.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glue versus suture, Outcome 9 Postoperative length of hospital stay (days).

Subgroup analyses showed no statistical difference between the synthetic or biological glue group and the suture group (MD −0.21, 95% CI −0.54 to 0.12 and MD 0.00, 95% CI −0.00 to 0.00, respectively; Analyses 1.9.1 and 1.9.2).

2.8 Recovery time to daily activities

Only three trials involving 403 people reported the outcome. The glue group had shorter recovery time to daily activities (MD −1.26, 95% CI −1.89 to −0.63, low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.10) without statistically significant heterogeneity (I² = 33%, P = 0.23). Subgroup analyses showed that both the synthetic and biological glue group had shorter recovery times to daily activities than the suture group (MD −1.87, 95% CI −2.86 to −0.88 and MD −1.00, 95% CI −1.26 to −0.74, respectively; Analyses 1.10.1 and 1.10.2).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glue versus suture, Outcome 10 Recovery time to daily activities (days).

2.9 Quality of life

Only Campanelli 2012 reported the quality of life evaluations (SF‐12v2 questionnaire) and participant satisfaction. Numerical improvements from baseline seen in the fibrin sealant group relative to sutures in terms of general health at 1, 6, and 12 months were not significant. Physical and mental component summary scores were similar between groups at each time point, as were scores on individual SF‐12v2 domains. Regarding participant satisfaction with the overall procedure, more people in the fibrin sealant group than in the sutures group answered positively when asked if they would have the same procedure again (98.7% vs 92.2%; P = 0.0035).

Discussion

Summary of main results

Compared to fixation with suture, our review shows that people undergoing Lichtenstein's procedure may benefit more from fixation with glue in terms of chronic pain, duration of operation, haematoma, and recovery time to daily activities. Meanwhile, there are no statistically significant differences between the two groups in other aspects such as hernia recurrence, wound/superficial infection, mesh/deep infection, seroma, persisting numbness, quality of life and postoperative length of stay. Given the low event rates for outcomes such as recurrence and infection, a lack of statistical significance cannot be interpreted as there being no difference — it may be that the analyses were just unable to detect it due to the relatively small number of participants (lack of statistical power).

As for subgroup analysis: fixation with synthetic glue and with biological glue showed similar results to fixation with suture, with the exception of haematoma, where there was no statistically significant difference between the biological glue and suture group in terms of the number of people experiencing haematoma.

The overall estimate of postoperative chronic pain was altered in subgroup analyses of lightweight versus heavyweight mesh. Analysis of included studies using lightweight mesh ― Bracale 2012, Helbling 2003, Kim‐Fuchs 2012, Moreno‐Egea 2014, Paajanen 2011 and Shen 2012 ― showed a less profound and insignificant reduction of chronic pain in the glue group (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.17) compared to the suture group. Interestingly, when we only included studies using heavyweight mesh ― (Campanelli 2012 and Jain 2009) ― a significant benefit from the fixation with glue was still evident and even more profound (OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.82) than in the overall analyses (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.91). Thus, participants in a subgroup of heavyweight mesh might therefore benefit more from fixation with glue compared to those in a subgroup of lightweight mesh. In a recent publication by Miserez 2014, results showed that lightweight mesh can cause less chronic pain compared to heavyweight mesh, which has been recommended in a guideline from the European Hernia Society on the treatment of inguinal hernia in adults (Miserez 2014) (Grade B). However in this study, we find that fewer people suffered from chronic pain when heavyweight mesh was applied compared to lightweight mesh (9/158, 5.7% vs 43/459, 9.4% in the glue group; 18/158, 11.4% vs 55/467, 11.8% in the suture group). It was hard to explain as these were not controlled trials studying the difference between heavyweight mesh and lightweight mesh. Maybe it was because of the heterogeneity between studies or the relatively small number of people in the subgroup analysis. But our result shows that a smaller proportion of people in the glue group suffered from chronic pain in both subgroups of heavyweight mesh and lightweight mesh compared to the suture group. Whether patients treated with lightweight mesh can benefit from fixation with glue needs to be further studied, as more and more lightweight mesh is applied worldwide.

Only one study was judged to be at overall low risk of bias (Paajanen 2011). In this study chronic pain did not differ significantly between the two groups (OR 1.39, 95% CI 0.76 to 2.56), but with only 302 participants the power of the analysis was greatly reduced.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Much dissimilarity with regard to inclusion criteria, outcome definitions, experience of surgeons, mesh type, nerve identification and protection, details of fixation and period of follow‐up may raise doubts as to whether pooling of data was appropriate in the present meta‐analysis. One critical issue is the definition of chronic pain: the duration and intensity of chronic pain is not uniform, making the incidence of chronic pain quite different between studies. Most authors define chronic pain as a pain lasting for more than three months according to the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) (Aasvang 1986). However, this definition is based on non‐surgical chronic pain. A clinical diagnosis of neuropathic pain is still not well defined. A second issue is the handling of the three nerves at the groin region. As damaged or trapped nerves are the main cause of neuropathic pain after hernioplasty, identification and protection of all three nerves during open inguinal hernia repair is recommended to reduce the risk of chronic incapacitating pain, according to the international guidelines for prevention and management of post‐operative chronic pain following inguinal hernia surgery (Alfieri 2011). However, the majority of the included studies did not provide sufficient information on this issue. Only the study by Helbling 2003 covered resection of nerves, but the average rate of nerve resection was less than 41% (18/48 versus 18/44). Furthermore the iliohypogastric nerve, one of the three nerves in this region, was not mentioned throughout the full text. Most importantly, in their Discussion section the authors mentioned that they meant to preserve these nerves. The nerves were resected because neuralgias were feared caused by intraoperatively damaged nerve fibres.

To control clinical heterogeneity, only studies applying Lichtenstein hernioplasty were included. Accordingly, our review cannot tell whether glue fixation is superior or inferior to fixation with suture during the Milligan procedure or hernioplasty with other kinds of mesh like PHS (Prolene Hernia System), UHS (Ultrapro Hernia System) and Modified Kugel Patch. Compared with Lichtenstein hernioplasty, these procedures differ materially, and the demand for stitching is much less.

As all the included trials only included people with primary inguinal hernia without complication, the role of glue fixation in people with recurrent hernia, femoral hernia or complicated hernia is still unknown. We also cannot answer the role of glue in TAPP (Transabdominal Pre‐Peritoneal) or TEP (Totally Extraperitoneal) repair. Two systematic reviews evaluating the role of glue in hernioplasty have been published (Fortelny 2012; Morales‐Conde 2011). Both of them found benefit in glue fixation during laparoscopic hernioplasty. An associated Cochrane Systematic Review is in preparation. According to the guidelines for laparoscopic (TAPP) and endoscopic (TEP) treatment of inguinal hernia published in 2011 (Bittner 2011), available evidence shows that fibrin glue is associated with low recurrence rates (Level 1B) and less acute and chronic pain than stapling. And the update with level 1 studies of the European Hernia Society guidelines on the treatment of inguinal hernia in adults concludes that there is possibly a short‐term benefit (postoperative pain) of atraumatic mesh fixation in endoscopic procedures (TAPP) (Miserez 2014).

Quality of the evidence

We identified no unpublished studies in this review.

Although we developed strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, the clinical heterogeneity noted above in terms of outcome definitions, experience of surgeon, mesh type, nerve identification and protection, details of fixation and period of follow‐up still translated into statistical heterogeneity. It is difficult to eliminate between‐study heterogeneity completely so we applied the random‐effects model instead if substantial statistical heterogeneity existed.

The potential influence of publication bias on the results of this systematic review can be considered small. Due to the extensive literature search using electronic databases without language restriction and our checking of reference lists of identified papers, it is unlikely that we failed to identify important studies.

Three out of 12 trials were assessed as having moderate risk of bias; eight trials showed high risk of bias in at least one of the investigated domains. Selection bias may have played a role in some of the included trials as two studies were quasi‐randomised controlled trials and the allocation sequence of one trial was not concealed. Nearly half of the included trials either did not provide adequate information or had high risk of bias regarding blinding processes, which raises the possibility of performance bias. With regard to blinding of outcome assessment, only four of 12 trials had low risk of bias, which raises the possibility of detection bias. The risk of bias for incomplete outcome data of all the included studies is moderate to low. Therefore, no obvious attrition bias existed. Ten of the 12 trials reported on all primary and secondary outcomes, but two trials did not report on some important outcomes: reporting bias may play a role here. Most trials did not provide details of funding sources and any declarations of interest; however one study was funded by Baxter Healthcare, which is a manufacturer of fibrin sealant, so an additional risk of bias may exist. For quite a number of outcomes, the total number of events was small and the confidence intervals were wide, which indicates that the estimates of effects obtained are imprecise. Meanwhile, the number of trials was too few to assess inconsistency for recovery time to daily activities. Taking into account all of these negative factors, the quality of evidence across the comparisons in this review is low to moderate and needs to be carefully considered (Table 1).

Potential biases in the review process

We tried many ways, including asking for help from the authors and from the staff of the Cochrane Colorectal Cancer Group, to get the full text of Bar 2009 but failed. The trial is therefore listed as a study awaiting classification. This might have produced some publication bias.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Several other meta‐analyses have been published in this field. Colvin 2013 included not only the Lichtenstein procedure, but also other open repair techniques of inguinal hernia using plug and mesh, or PHS or Modified Kugel patch. They included 10 RCTs and reported similar results to ours. Ladwa 2013 also included all kinds of open repair procedure. They conclude that glue fixation is comparable to suture fixation in terms of postoperative complications including chronic pain and recurrence, and can reduce operative time. They included only seven trials. Goede 2013 only included the Lichtenstein procedure. Although they reported similar results to ours, they included only seven trials, two of which (Arslani 2010 and Torcivia 2011) were excluded from this review (See Characteristics of excluded studies).

Our review included more trials (12) focusing on the Lichtenstein procedure. This allowed us to produce more precise estimates. We also performed GRADE assessments to highlight the quality of the evidence.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Glue fixation of mesh for the Lichtenstein procedure is comparable to, and seemingly superior to, fixation with suture in terms of chronic pain. People having repairs with heavyweight mesh may benefit more from fixation with glue compared to those having repair with lightweight mesh with regard to chronic pain. Glue fixation appears superior in outcomes like duration of operation, haematoma and recovery time to daily activities. Glue fixation is not apparently associated with an increased risk of infection, hernia recurrence, seroma, persisting numbness, quality of life or postoperative length of stay. Based on these results, glue may be a sensible alternative to suture for mesh fixation in Lichtenstein repair. However, these results should be interpreted with caution, as the quality of the evidence for most of the outcomes is low to moderate, meaning that we are not confident that further research would not alter the pooled results and therefore the conclusions drawn from the analyses. The only trial with well presented methodology showed no statistically significant difference between groups, but it is not clear if that means there is no difference or rather that the trial was too underpowered to detect one. We do not know the role of glue fixation in people with recurrent hernia, femoral hernia or complicated hernia. Whether synthetic glue is superior to biological glue, or vice versa, is also still unknown.

Implications for research.

Hernia recurrence is considered a primary concern, despite being a relatively rare complication. Currently, available evidence is limited by the short duration of follow‐up, the relatively small number of participants included and the overall quality of the primary trials. It is generally agreed that follow‐up of three to five years is necessary to detect the majority of recurrences, so larger high‐quality trials reporting longer follow‐up are warranted. Postoperative chronic pain is also considered a primary concern, and has been reported before and after three months postoperatively in the included trials in this review. As most experts in this field currently recommend reporting chronic pain for more than three months, this should be considered and adopted in future study protocols. Potential benefits of using either synthetic glue or biological glue, as well as the role of nerve identification and protection, should also be assessed in future trials.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Cochrane Colorectal Cancer Group and the peer reviewers for their valuable comments and assistance.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

Cochrane Library (CENTRAL) ‐ Issue 5, 2016

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Sutures] explode all trees #2 MeSH descriptor: [Adhesives] explode all trees #3 MeSH descriptor: [Fibrin Tissue Adhesive] explode all trees #4 MeSH descriptor: [Tissue Adhesives] explode all trees #5 MeSH descriptor: [Suture Techniques] explode all trees #6 MeSH descriptor: [Cyanoacrylates] explode all trees #7 MeSH descriptor: [Polyglycolic Acid] explode all trees #8 glue or suture* or tissue adhesiv* or fibrin or N‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate or Tisseel or Tissucol or cyanoacrylate* or polyglycolic* acid* or adhesiv*:ti,ab,kw #9 (#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8) #10 MeSH descriptor: [Surgical Mesh] explode all trees #11 mesh:ti,ab,kw #12 (#10 or #11) #13 MeSH descriptor: [Herniorrhaphy] explode all trees #14 lichtenstein or open or repair or tension‐free or hernio*:ti,ab,kw #15 (#13 or #14) #16 MeSH descriptor: [Hernia, Inguinal] explode all trees #17 ((inguina* or groin*) near/3 hernia*):ti,ab,kw #18 (#16 or #17) #19 (#9 and #12 and #15 and #18) Publication year from 1986

Appendix 2. MEDLINE search strategy

MEDLINE (OVID) ‐ 1986 to May 2016

1. exp Sutures/ 2. exp Adhesives/ 3. exp Fibrin Tissue Adhesive/ 4. exp Tissue Adhesives/ 5. exp Suture Techniques/ 6. exp Cyanoacrylates/ 7. exp Polyglycolic Acid/ 8. (glue or suture* or tissue adhesiv* or fibrin or N‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate or Tisseel or Tissucol or cyanoacrylate* or polyglycolic* acid* or adhesiv*).mp. 9. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 10. exp Surgical Mesh/ 11. mesh.mp. 12. 10 or 11 13. exp Herniorrhaphy/ 14. (lichtenstein or open or repair or tension‐free or hernio*).mp. 15. 13 or 14 16. exp Hernia, Inguinal/ 17. ((inguina* or groin*) adj3 hernia*).mp. 18. 16 or 17 19. 9 and 12 and 15 and 18 20. randomized controlled trial.pt. 21. controlled clinical trial.pt. 22. randomized.ab. 23. placebo.ab. 24. clinical trials as topic.sh. 25. randomly.ab. 26. trial.ti. 27. 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 28. exp animals/ not humans.sh. 29. 27 not 28 30. 19 and 29 31. limit 30 to yr="1986 ‐Current"

Appendix 3. Embase search strategy

Embase (OVID) ‐ 1986 to May 2016

1. exp suture/ 2. exp adhesive agent/ 3. exp suturing method/ 4. exp cyanoacrylate derivative/ 5. exp polyglycolic acid/ 6. (glue or suture* or tissue adhesiv* or fibrin or N‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate or Tisseel or Tissucol or cyanoacrylate* or polyglycolic* acid* or adhesiv*).mp. 7. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 8. exp surgical mesh/ 9. exp mesh sling/ 10. mesh.mp. 11. 8 or 9 or 10 12. exp hernioplasty/ 13. exp herniorrhaphy/ 14. exp herniotomy/ 15. (lichtenstein or open or repair or tension‐free or hernio*).mp. 16. 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 17. exp inguinal hernia/ 18. ((inguina* or groin*) adj3 hernia*).mp. 19. 17 or 18 20. 7 and 11 and 16 and 19 21. CROSSOVER PROCEDURE.sh. 22. DOUBLE‐BLIND PROCEDURE.sh. 23. SINGLE‐BLIND PROCEDURE.sh. 24. (crossover* or cross over*).ti,ab. 25. placebo*.ti,ab. 26. (doubl* adj blind*).ti,ab. 27. allocat*.ti,ab. 28. trial.ti. 29. RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL.sh. 30. random*.ti,ab. 31. 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 32. (exp animal/ or exp invertebrate/ or animal.hw. or nonhuman/) not (exp human/ or human cell/ or (human or humans or man or men or wom?n).ti.) 33. 31 not 32 34. 20 and 33 35. limit 34 to yr="1986 ‐Current"

Appendix 4. Science Citation Index search strategy

Science Citation Index ‐ 1986 to May 2016

#1 Topic=(glue or suture* or tissue adhesiv* or fibrin or N‐butyl‐2‐cyanoacrylate or Tisseel or Tissucol or cyanoacrylate* or polyglycolic* acid* or adhesiv*) #2 Topic=(mesh) #3 Topic=(lichtenstein or open or repair or tension‐free or hernio*) #4 Topic=(((inguina* or groin*) near/3 hernia*)) #5 Topic=(multicenter or phase 3 or phase 4 or singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl* or blind* or mask* or random* or control* or trial or RCT or group or cross* over* or factorial* or placebo* or volunteer*) #6 (#1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 AND #5)

Appendix 5. CBM (Chinese Biomedical Database) search strategy

全部字段:疝 and 全部字段:缝 and 全部字段:补片 and 全部字段:胶 or 粘 or 氰基丙烯酸酯

English translation: (All fields: hernia) and (All fields: suture) and (All fields: mesh) and All fields: (glue or stick or cyanoacrylate)

Appendix 6. CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure) search strategy

FT="补片" AND FT="缝" AND FT=("胶" + "氰基丙烯酸酯" + "粘") and FT="疝"

English translation: (FT="hernia") and (FT="suture") and (FT="mesh") and (FT=("glue" or "stick" or "cyanoacrylate"))

(Note: FT means full text)

Appendix 7. VIP (a full‐text database of China) search strategy

U=补片*(U=缝)*(U=(胶+氰基丙烯酸酯+粘))*(U=疝)

English translation: U=mesh*(U=suture)*(U=(glue + cyanoacrylate + stick))*(U=hernia)

(Note: U means any field)

Appendix 8. Wanfang databases search strategy

补片*缝*(胶+氰基丙烯酸酯+粘)*疝

English translation: mesh*suture*(glue + cyanoacrylate + stick)*hernia

Appendix 9. Criteria for judging risk of bias in the ‘Risk of bias’ assessment tool

RANDOM SEQUENCE GENERATION

| Criteria for a judgement of 'Low risk' of bias. | The investigators describe a random component in the sequence generation process such as:

|

| Criteria for the judgement of 'High risk' of bias. | The investigators describe a non‐random component in the sequence generation process.

|

| Criteria for the judgement of 'Unclear risk' of bias. | Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement of 'Low risk' or 'High risk'. |

ALLOCATION CONCEALMENT

| Criteria for a judgement of 'Low risk' of bias. | Participants and investigators enrolling participants could not foresee assignment because one of the following, or an equivalent method, was used to conceal allocation.

|

| Criteria for the judgement of 'High risk' of bias. | Participants or investigators enrolling participants could possibly foresee assignments and thus introduce selection bias, such as allocation based on:

|

| Criteria for the judgement of 'Unclear risk' of bias. | Insufficient information to permit judgement of 'Low risk' or 'High risk'. This is usually the case if the method of concealment is not described or not described in sufficient detail to allow a definite judgement. |

BLINDING OF PARTICIPANTS AND PERSONNEL

| Criteria for a judgement of 'Low risk' of bias. | Any one of the following.

|

| Criteria for the judgement of 'High risk' of bias. | Any one of the following.

|

| Criteria for the judgement of 'Unclear risk' of bias. | Any one of the following.

|

BLINDING OF OUTCOME ASSESSMENT

| Criteria for a judgement of 'Low risk' of bias. | Any one of the following.

|

| Criteria for the judgement of 'High risk' of bias. | Any one of the following.

|

| Criteria for the judgement of 'Unclear risk' of bias. | Any one of the following.

|

INCOMPLETE OUTCOME DATA

| Criteria for a judgement of 'Low risk' of bias. | Any one of the following.

|

| Criteria for the judgement of 'High risk' of bias. | Any one of the following.

|

| Criteria for the judgement of 'Unclear risk' of bias. | Any one of the following.

|

SELECTIVE REPORTING

| Criteria for a judgement of 'Low risk' of bias. | Any of the following.

|

| Criteria for the judgement of 'High risk' of bias. | Any one of the following.

|

| Criterion for the judgement of 'Unclear risk' of bias. | Insufficient information to permit judgement of 'Low risk' or 'High risk'. It is likely that the majority of studies will fall into this category. |

OTHER BIAS

| Criterion for a judgement of 'Low risk' of bias. | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias. |

| Criteria for the judgement of 'High risk' of bias. | There is at least one important risk of bias. For example, the study:

|

| Criteria for the judgement of 'Unclear risk' of bias. | There may be a risk of bias, but there is either:

|

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Glue versus suture.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Chronic pain | 10 | 1473 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.44, 0.91] |

| 1.1 Synthetic glue versus suture | 7 | 945 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.46, 1.04] |

| 1.2 Biological glue versus suture | 3 | 528 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.20, 1.03] |

| 2 Hernia recurrence | 12 | 1987 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.44 [0.63, 3.28] |

| 2.1 Synthetic glue versus suture | 8 | 991 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.58 [0.62, 4.05] |

| 2.2 Biological glue versus suture | 4 | 996 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.17, 5.90] |

| 3 Duration of operation (mins) | 9 | 1790 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.13 [‐4.48, ‐1.78] |

| 3.1 Synthetic glue versus suture | 6 | 904 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.67 [‐6.10, ‐1.24] |

| 3.2 Biological glue versus suture | 3 | 886 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.72 [‐3.67, ‐1.77] |

| 4 Wound/superficial infection | 7 | 818 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.23 [0.37, 4.11] |

| 4.1 Synthetic glue versus suture | 5 | 606 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.23 [0.37, 4.11] |

| 4.2 Biological glue versus suture | 2 | 212 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5 Mesh/deep infection | 8 | 1448 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.16, 2.83] |

| 5.1 Synthetic glue versus suture | 5 | 768 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.06, 16.14] |

| 5.2 Biological glue versus suture | 3 | 680 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.58 [0.11, 3.19] |

| 6 Haematoma | 10 | 1439 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.52 [0.31, 0.86] |

| 6.1 Synthetic glue versus suture | 7 | 911 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.54 [0.32, 0.91] |

| 6.2 Biological glue versus suture | 3 | 528 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.05, 2.13] |

| 7 Seroma | 8 | 1239 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.51, 1.33] |

| 7.1 Synthetic glue versus suture | 4 | 243 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.14, 4.02] |

| 7.2 Biological glue versus suture | 4 | 996 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.51, 1.37] |

| 8 Persisting numbness | 4 | 728 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.57, 1.14] |

| 8.1 Synthetic glue versus suture | 2 | 310 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.46, 1.32] |

| 8.2 Biological glue versus suture | 2 | 418 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.52, 1.31] |

| 9 Postoperative length of hospital stay (days) | 6 | 1009 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.12 [‐0.35, 0.10] |

| 9.1 Synthetic glue versus suture | 5 | 541 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.21 [‐0.54, 0.12] |

| 9.2 Biological glue versus suture | 1 | 468 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [‐0.00, 0.00] |

| 10 Recovery time to daily activities (days) | 3 | 403 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.26 [‐1.89, ‐0.63] |

| 10.1 Synthetic glue versus suture | 2 | 87 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.87 [‐2.86, ‐0.88] |

| 10.2 Biological glue versus suture | 1 | 316 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.0 [‐1.26, ‐0.74] |

Comparison 2. Glue versus suture: worst case scenarios.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Chronic pain | 10 | 1473 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.46, 0.91] |

| 1.1 Synthetic glue versus suture | 7 | 945 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.47, 1.02] |

| 1.2 Biological glue versus suture | 3 | 528 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.53 [0.27, 1.05] |

| 2 Hernia recurrence | 12 | 1987 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.80, 1.85] |

| 2.1 Synthetic glue versus suture | 8 | 991 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.31 [0.84, 2.04] |

| 2.2 Biological glue versus suture | 4 | 996 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.19, 2.40] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by year of study]

Helbling 2003.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial Unilateral hernia. Country: Switzerland. Setting: not reported. Enrolment dates: From January 2001 until December 2001. |

|

| Participants | Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

Glue group:

Suture group:

|

|

| Interventions | Lichtenstein inguinal hernioplasty with Vipro II‐mesh (14 cm × 8 cm) (pliable lightweight multi‐filament mesh). Glue group:

Suture group:

|

|

| Outcomes | Recurrences, chronic pain, infection, hematoma, recovery time to normal activity | |

| Notes | Handling of nerves:

Length of follow‐up: 3 months. Time points of the analysis: 3 months. Intention‐to‐treat analysis: yes. The number of participants randomized: 22 in Glue group; 24 in Suture group The number of participants evaluated: 22 in Glue group; 24 in Suture group Information from publication only. No details of funding sources and any declarations of interest provided. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not clear. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sealed envelopes |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not clear. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not clear. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 3 months after the operation, all but 1 person resumed normal physical activity, so we can believe that all the participants completed follow‐up. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | It is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Not clear. Without details of funding sources and any declarations of interest. |

Nowobilski 2004.

| Methods | Randomized controlled trial. Unilateral hernia. Country: Poland. Setting: Department of General & Gastroenterological Surgery, St. Vincent a’Paulo Hospital of Gdynia, Poland. Enrolment dates: between May and November 2003. |

|

| Participants | Inclusion criteria:

Glue group:

Suture group:

|

|

| Interventions | Lichtenstein inguinal hernioplasty with polypropylene mesh. Glue group:

Suture group:

|

|

| Outcomes | Recurrences, infection, seroma, length of operation, time to discharge, recovery time to normal activity | |

| Notes | Handling of nerves:

Length of follow‐up: median of 4.7 (range 3 to 9) months. Time points of the analysis: last day of the follow‐up. Intention‐to‐treat analysis:yes. The number of people randomized: 22 in Glue group; 24 in Suture group The number of people evaluated: 22 in Glue group; 24 in Suture group Information from publication only. No details of funding sources and any declarations of interest provided. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not clear. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not clear. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not clear. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not clear. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All participants had been followed up for at least 3 months. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Without the result of chronic pain. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Not clear. Without details of funding sources and any declarations of interest. |

Hidalgo 2005.

| Methods | Quasi‐randomised controlled trials. Bilateral hernia; by hernia. Country: Spain. Setting: not reported. Enrollment dates: January 2001 to July 2003. |

|

| Participants | Inclusion criteria:

Male: 100% Age: between the ages of 49 and 71 years Complications: obesity (56.3%); hypertension (32.7%); and obstructive pulmonary disease (20%) Hernia type: not reported. Direct:indirect: not reported. |

|

| Interventions | Lichtenstein inguinal hernioplasty with polypropylene mesh for both sides in 1 operation. 55 participants Glue group (left side):

Suture group (right side):

|

|

| Outcomes | Recurrences, infection, seroma, hematoma, chronic pain, recovery time to normal activity | |

| Notes | Handling of nerves:

Length of follow‐up: 1 year. Time points of the analysis: 1 year. Intention‐to‐treat analysis: yes. The number of people randomized: 55 in Glue group; 55 in Suture group The number of people evaluated: 55 in Glue group; 55 in Suture group Information from publication only. No details of funding sources and any declarations of interest provided. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | On the right side polypropylene sutures were used (prolene 2/0); while on the left, attachment was done using glue (Tissucol). |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | No. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | No. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not clear. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All participants had been followed for at least 1 year. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | It is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Not clear. Without details of funding sources and any declarations of interest. |

Jain 2009.

| Methods | Quasi‐randomised controlled trials. Alternately assigned to 1 of 2 groups. Unilateral hernia. Country: India. Setting: the surgery outpatient department of Lok Nayak Hospital, New Delhi. Enrolment dates: not reported. |

|

| Participants | Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

Glue group:

Suture group:

|

|

| Interventions | Lichtenstein inguinal hernioplasty with 15 cm × 10 cm heavyweight polypropylene mesh. Glue group:

Suture group:

|

|

| Outcomes | Recurrences, chronic pain, length of operation, time to discharge, recovery time to normal activity | |

| Notes | Handling of nerves:

Length of follow‐up: 1 year. Time points of the analysis: 6 months for chronic pain and 1 year for recurrence. Intention‐to‐treat analysis:yes. The number of people randomized: 40 in Glue group; 40 in Suture group The number of people evaluated: 40 in Glue group; 40 in Suture group Information from publication only. No details of funding sources and any declarations of interest provided. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Alternately assigned to 1 of 2 groups. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not clear. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The participants were blinded for the type of procedure to be performed. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The follow‐up was performed by a surgery registrar who was blinded for the method of hernia repair employed in the participants. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All 80 participants had been followed for at least 1 year. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | It is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Not clear. Without details of funding sources and any declarations of interest. |

Paajanen 2011.

| Methods | Randomized multi‐centre trial conducted in the ambulatory surgery unit of 3 hospitals in Finland. Unilateral hernia. Country: Finland. Setting: 3 hospitals in Finland (100 in hospital A, 80 in hospital B and 122 in hospital C). Enrolment dates: between June 2007 and May 2009. |

|

| Participants | Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

Glue group:

Suture group:

|

|

| Interventions | Lichtenstein inguinal hernioplasty with 9 × 13 cm trimmed lightweight polypropylene mesh (Optilene® 60 gr/m²; B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany). Glue group: