Abstract

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (commonly referred to as chronic bronchitis and emphysema) is a chronic lung condition characterised by the inflammation of airways and irreversible destruction of pulmonary tissue leading to progressively worsening dyspnoea. It is a leading international cause of disability and death in adults. Evidence suggests that there is an increased prevalence of anxiety disorders in people with COPD. The severity of anxiety has been shown to correlate with the severity of COPD, however anxiety can occur with all stages of COPD severity. Coexisting anxiety and COPD contribute to poor health outcomes in terms of exercise tolerance, quality of life and COPD exacerbations. The evidence for treatment of anxiety disorders in this population is limited, with a paucity of evidence to support the efficacy of medication‐only treatments. It is therefore important to evaluate psychological therapies for the alleviation of these symptoms in people with COPD.

Objectives

To assess the effects of psychological therapies for the treatment of anxiety disorders in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Search methods

We searched the specialised registers of two Cochrane Review Groups: Cochrane Common Mental Disorders (CCMD) and Cochrane Airways (CAG) (to 14 August 2015). The specialised registers include reports of relevant randomised controlled trials from The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, Embase, and PsycINFO. We carried out complementary searches on PsycINFO and CENTRAL to ensure no studies had been missed. We applied no date or language restrictions.

Selection criteria

We considered all randomised controlled trials (RCTs), cluster‐randomised trials and cross‐over trials of psychological therapies for people (aged over 40 years) with COPD and coexisting anxiety disorders (as confirmed by recognised diagnostic criteria or a validated measurement scale), where this was compared with either no intervention or education only. We included studies in which the psychological therapy was delivered in combination with another intervention (co‐intervention) only if there was a comparison group that received the co‐intervention alone.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened citations to identify studies for inclusion and extracted data into a pilot‐tested standardised template. We resolved any conflicts that arose through discussion. We contacted authors of included studies to obtain missing or raw data. We performed meta‐analyses using the fixed‐effect model and, if we found substantial heterogeneity, we reanalysed the data using the random‐effects model.

Main results

We identified three prospective RCTs for inclusion in this review (319 participants available to assess the primary outcome of anxiety). The studies included people from the outpatient setting, with the majority of participants being male. All three studies assessed psychological therapy (cognitive behavioural therapy) plus co‐intervention versus co‐intervention alone. We assessed the quality of evidence contributing to all outcomes as low due to small sample sizes and substantial heterogeneity in the analyses. Two of the three studies had prespecified protocols available for comparison between prespecified methodology and outcomes reported within the final publications.

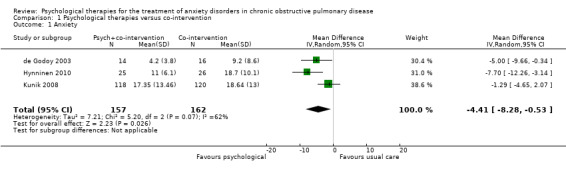

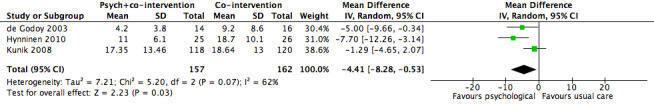

We observed some evidence of improvement in anxiety over 3 to 12 months, as measured by the Beck Anxiety Inventory (range from 0 to 63 points), with psychological therapies performing better than the co‐intervention comparator arm (mean difference (MD) ‐4.41 points, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐8.28 to ‐0.53; P = 0.03). There was however, substantial heterogeneity between the studies (I2 = 62%), which limited the ability to draw reliable conclusions. No adverse events were reported.

Authors' conclusions

We found only low‐quality evidence for the efficacy of psychological therapies among people with COPD with anxiety. Based on the small number of included studies identified and the low quality of the evidence, it is difficult to draw any meaningful and reliable conclusions. No adverse events or harms of psychotherapy intervention were reported.

A limitation of this review is that all three included studies recruited participants with both anxiety and depression, not just anxiety, which may confound the results. We downgraded the quality of evidence in the 'Summary of findings' table primarily due to the small sample size of included trials. Larger RCTs evaluating psychological interventions with a minimum 12‐month follow‐up period are needed to assess long‐term efficacy.

Plain language summary

Psychotherapy for treatment of anxiety in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (chronic bronchitis and emphysema)

Why is this review important?

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is commonly referred to as emphysema and chronic bronchitis. People with COPD are more likely to have anxiety disorders compared with the general population. Symptoms of anxiety affect various aspects of daily life, including quality of life and the ability to perform physical activities. Psychological therapies are used as part of clinical practice to treat these symptoms, however, there is little evidence to support these techniques.

Who will be interested in this review?

Health professionals and people with emphysema and underlying anxiety and panic.

What questions does this review aim to answer?

What is the current evidence on psychological therapies for anxiety in people with COPD and coexisting anxiety?

Which studies were included in the review?

Randomised controlled trials (research trials in which participants are allocated according to a random sequence either to the intervention to be tested or to a comparator intervention).

What does the evidence from the review tell us?

This systematic review found three studies with a total of 319 participants with COPD and coexisting anxiety. All three studies assessed psychotherapy (CBT) with a co‐intervention, versus the co‐intervention alone. There was limited evidence showing some improvements in reduced levels of anxiety and improved quality of life in the psychotherapy group. It is important to note that the overall quality of the evidence was low and hence further research is needed to increase our confidence in this effect. A limitation of this review is that all three included studies recruited participants with both anxiety and depression, not just anxiety, which may confound the results.

What should happen next?

Further research is needed to establish whether this therapy will reduce hospital admissions and length of hospital stays, as this was not assessed in the current evidence base. Larger studies of longer duration need to be conducted. There are at least two more clinical trials currently ongoing for this question. Once they are published, the evidence from them could increase or decrease our confidence in the findings of this review.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Psychological therapies for anxiety for people with COPD.

| Psychological therapies for anxiety for people with COPD | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with COPD

Settings: hospital and home

Intervention: psychological therapies plus co‐interventions for anxiety Comparators: co‐intervention alone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Psychological therapies for anxiety | |||||

| Anxiety Becks Anxiety Inventory. Scale from: 0 to 63. Follow‐up: 3‐12 months | The mean anxiety in the control groups was 15.51 | The mean anxiety in the intervention groups was 4.41 lower (8.28 to 0.53 lower) | 319 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | Beneficial findings were observed in favour of the psychological therapy group (p= 0.03), with levels of anxiety half that of the control population by final follow‐up (Gillis 1995) | |

| Adverse events | Study population | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | No studies reported on adverse events | |

| See comment | See comment | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| Quality of life ‐ physical composite SGRQ and SF36 Follow‐up: 6‐12 months | The mean quality of life ‐ physical composite in the control groups was 45.08 | The mean quality of life ‐ physical composite in the intervention groups was 0.40 standard deviations lower (0.88 lower to 0.08 higher) | 289 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | Two studies reported on quality of life with one study (Kunik 2008) reporting both SF36 and CRQ. Meta‐analysis occurred only for SF36 composite scores with SGRQ, as no totals were available for CRQ. Sub‐group analyses separating short‐term (0 to 3 months; SMD ‐0.22, 95% CI ‐0.45 to 0.01; P = 0.06) and long‐term follow‐up (6 to 12 months; SMD ‐0.30, 95% CI ‐0.53 to ‐0.06; P = 0.01) resulted in better treatment outcomes long‐term. | |

| Quality of life ‐ emotional composite SGRQ and SF36 Follow‐up: 6‐12 months | The mean quality of life ‐ emotional composite in the control groups was 52.3 | The mean quality of life ‐ emotional composite in the intervention groups was 0.30 standard deviations lower (1.03 lower to 0.44 higher) | 289 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | Two studies reported on quality of life with one study (Kunik 2008) reporting both SF36 and CRQ. We only meta‐analysed SF36 composite scores with SGRQ as no totals were available for CRQ. Sub‐group analyses separating short‐term (0 to 3 months; (SMD 0.05, 95% CI ‐0.18 to 0.28) and long‐term follow‐up (6 to 12 months; (SMD ‐0.09, 95% CI ‐0.32 to 0.14) resulted in better treatment outcomes long‐term. | |

| Exercise capacity 6MWD Follow‐up: 3‐12 months | The mean exercise capacity in the control groups was 839 | The mean exercise capacity in the intervention groups was 2.78 lower (58.49 lower to 52.94 higher) | 268 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,4 | The Kunik 2008 study which examined 6MWD at 8 weeks (post‐intervention) and again at 12 months' follow‐up with a difference in favour of the control arm at 12 months (P = 0.05). However, authors reported that group means at beginning of the follow‐up period were not equal (P < 0.01), contributing to the spurious finding. | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). 6MWD: six minute walking distance; CI: confidence interval; CRQ: Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire; SF36: Short Form 36; SGRQ: Saint George's Respiratory Questionnaire | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Substantial heterogeneity as identified via the I‐squared statistic and visual inspection of the data. 2Two of the three studies have sample sizes lower than the prespecified optimal sample size, study participants were predominantly men across all three studies and most subjects had comorbid anxiety and depression, therefore imprecision was downgraded by one point. 3Both studies had sample sizes lower than the prespecified optimal sample size. 4Wide confidence intervals around effect estimate.

Background

Description of the condition

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a chronic lung condition characterised by the inflammation of airways and irreversible destruction of pulmonary tissue leading to progressively worsening dyspnoea and is a leading international cause of disability and death in adults (Kerstjens 2001). COPD is a preventable and treatable disease with some significant extrapulmonary effects. Its pulmonary component is characterised by airflow limitation that is not fully reversible (GOLD 2013). The diagnosis of COPD is based on the person's history, evaluation of risk factors and relevant investigations, including pulmonary function testing and chest imaging. Spirometry will typically show a post bronchodilator forced expiratory volume 1/forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) less than 70% (Rabe 2007). Anxiety disorder is a generalised term for a myriad of abnormal and pathological fear and anxiety states, including generalised anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder (PD), agoraphobia, neurocirculatory asthenia, obsessive‐compulsive disorder (OCD), and phobic disorders. GAD is defined as excessive anxiety which lasts for at least six months. Individuals must also experience three or more of the following symptoms: difficulty in concentrating; fatigue after little exertion; sleep disturbance; a sensation of being 'keyed up' (nervous or anxious); irritability or muscle tension, or both (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) IV criteria) (APA 1994). Other anxiety symptoms can include increased behavioural and psychological symptoms of distress (Suh 2013) and fears (Breland 2015), which is of particular importance as disease‐specific fears can have an impact on disability (Keil 2014).

Evidence suggests that there is an increased prevalence of anxiety disorders in people with COPD (Maurer 2008). Moreover, the severity of anxiety has been shown to correlate with the severity of COPD and the presence of lower PaO₂ (partial pressure of oxygen in the blood, an indicator of severity of COPD)(Elassal 2014). Other studies suggest that anxiety can occur at any stage of COPD (Kim 2000; Heslop‐Marshall 2014. Studies have suggested prevalence rates for anxiety disorders of 28%‐36% in people with COPD (Di Marco 2006; Yohannnes 2006). The lifetime prevalence of GAD in particular amongst people with COPD is estimated at between 10% and 15.8% (Brenes 2003). The prevalence of panic disorder in the COPD population is estimated to be ten times higher than the general population (Smoller 1996; Smoler 1999). Rates of anxiety symptoms in people with COPD range from 13% to 51% and are higher than the rates in people with heart failure, cancer, and other medical conditions (Brenes 2003). COPD is associated with a higher risk of anxiety, and co morbid COPD and anxiety is related to poor health outcomes in terms of exercise tolerance, quality of life, COPD exacerbations (Eisner 2010), inappropriate use of medications and persistence of smoking as a coping strategy for anxiety management (Royal College of Physcians). Several risk factors have been identified that contribute to anxiety amongst people with COPD, including being employed, less education, lack of contentment with family support, living with family and friends, comorbid hypertension and depression, and having 10 or more exacerbations per year (Tan 2013). Indeed, co‐morbid depression is known to be a strong predictor of anxiety (DiNicola 2013), which confounds anxiety symptoms making treatment more difficult (Atlantis 2013). By compromising health status, mood disorders lead to increased risk of hospitalisation and re‐hospitalisation (Gudmundsson 2005) and hence also increase direct and indirect costs to the health system.

Various models could be considered to explain increased levels of anxiety and panic in people with COPD (Ley 1985; Perna 2004). One model explains this relationship as catastrophic misinterpretations of ambiguous bodily sensations (such as shortness of breath, rapid heart rate) which increase arousal, creating a positive feedback loop that results in a panic attack (Clark 1986). A crucial difference between physically healthy people and those with COPD is that in the latter, breathing, the most basic of all physical functions necessary for life, is objectively threatened (as measured by tests of lung function) and subjectively difficult. Dyspnoea (shortness of breath) can be an unpleasant and potentially frightening experience at any time, and, as the key symptom of an eventually fatal illness like COPD, it is an ambiguous sensation open to catastrophic interpretation, leading to increased levels of anxiety and panic in people with COPD (Livermore 2010b).

Description of the intervention

Management strategies for the treatment of anxiety disorders in people with COPD include both pharmacological and non‐pharmacological interventions. Evidence that pharmacological therapies (anti‐anxiety or antidepressant medications, or both) provide statistically or clinically significant benefits for this group of patients is limited (Usmani 2011). Psychological therapies include cognitive or behavioural therapies, or both, psychodynamic psychotherapy, interpersonal psychotherapy, non‐directive therapy, support therapy and counselling (Rose 2002; Davison 2003). Psychological therapies are intentional interpersonal relationships used by trained psychotherapists to aid people with problems of living, with an aim of increasing the individual's well‐being. Psychological therapies may also be performed by practitioners with a number of different qualifications, including psychologists, marriage and family therapists, occupational therapists, licensed clinical social workers, counsellors, psychiatric nurses, psychotherapists, trained general nurses, psychoanalysts, and psychiatrists. The mode of delivery for these therapies may comprise individual, group or family (including couple) therapy, performed by a healthcare professional.

How the intervention might work

Because COPD is an irreversible condition, treatment recommendations are aimed at improving quality of life (Norweg 2005). Current evidence examining quality of life suggests a reduction in satisfaction above and beyond what should be expected by COPD disease severity or co‐morbid medical illnesses (Coventry 2007), indicating that psychological status plays an intrinsic role in overall well‐being. A recent study examining the impact of anxiety on the lives of people with COPD found that they felt isolated and would avoid social occasions and usual daily activities (Willgoss 2011). As a result, therapies targeting the reduction of psychological stressors should be expected to improve quality of life (Ries 1995; Rose 2002; Baraniak 2011).

Psychological therapies are often based on the assumption that psychological outcomes such as anxiety are linked with physical manifestations of COPD, for example dyspnoea, which can precipitate episodes of anxiety (Wu 2004). It has been hypothesised that a person's fear and misinterpretation of bodily experiences from dyspnoea and hyperventilation may cause a panic reaction (Nutt 1999). Alternatively, underlying psychological distress can contribute to an increased risk of symptom exacerbations, particularly those treated in the person's own environment (Laurin 2011). As such, people with anxiety and panic disorders interpret threats as more dangerous due to a higher awareness of cues such as dyspnoea and tachycardia (Mikkelsen 2004).

A psychological therapy, cognitive‐behaviour therapy (CBT), aims to identify and correct dysfunctional emotions, behaviours and cognitions through a goal‐orientated, systematic procedure (Rose 2002; Kaplan 2009). In the case of people with COPD, CBT may be a means of managing concurrent anxiety and depression. While not in itself improving an individual's medical condition, CBT may serve to increase perceived self‐efficacy and motivate people to manage their physical condition, thereby improving quality of life (Kunik 2001). Moreover, the learning about oneself that occurs in various forms of psychological therapy may in itself influence the structure and function of the brain (Kandel 1998) or may have a significant impact on serotonin metabolism (Viinamaki 1998). 'Third wave CBT' applies to behavioural psychological therapies that integrate mindfulness and acceptance of unwanted thoughts and feelings with a behavioural understanding of emotional suffering, to elicit change in thinking process. Behavioural therapy includes methods that focus on behaviours, not the thoughts and feelings that might be causing them. The behavioural approach to therapy assumes that behaviour that is associated with psychological problems develops through the same processes of learning that affect the development of other behaviours. Psychodynamic therapy focuses on unconscious processes as they are manifested in people's present behaviour. Hence by making the unconscious aspects of their life a part of their present experience, psychodynamic therapy helps people understand how their behaviour and mood are affected by unconscious feelings. Humanistic psychotherapy emphasises human uniqueness, positive qualities, and individual potential. It works by emphasising one's capacity to make informed and rational choices and develop to one's maximum potential. Integrative therapies are approaches that combine components of different psychological therapy models.

Why it is important to do this review

Anxiety disorders in people with COPD have been shown to increase disability and impair functional status, resulting in an overall reduction in their quality of life (Beck 1988; Weaver 1997). Importantly, the impact of anxiety on these outcomes was shown after adjusting for other potential confounders such as general health status, other medical conditions and COPD severity (Brenes 2003). Kim 2000 reported that anxiety and depression were more strongly related to functional status than the severity of COPD. Screening data from a large randomised controlled trial in the UK showed anxiety was common in COPD and was not correlated with COPD severity (Heslop‐Marshall 2014). Co‐morbid anxiety in an elderly population with COPD has been suggested as a significant predictor of the frequency of hospital admissions (Yohannes 2000). A recent study has shown that among people with COPD, anxiety is related to poorer health outcomes including worse submaximal exercise performance, greater risk of self‐reported functional limitations and a higher longitudinal risk of COPD exacerbations (Eisner 2010).

The evidence for treatment of anxiety disorders in COPD is limited, and there are limited data to support the efficacy of medication‐only treatments (Borson 1998). The results of a Cochrane Review evaluating the effects of pharmacological interventions for anxiety in people with COPD are inconclusive (Usmani 2011). A feasibility study of antidepressants in this population suggested poor acceptance of antidepressants for various reasons including side‐effects and reluctance to take "yet another medication" (Yohannes 2001). Furthermore the association between anxiety/panic and dyspnoea/COPD had been explained by various psychological theories (Clark 1986; Livermore 2010b). It is important therefore, to evaluate psychological therapies for the alleviation of these symptoms in people with COPD.

In light of the health burden caused by psychological disorders and the limited evidence supporting treatment options, this review is one of four linked Cochrane Reviews that assess the effects of pharmacological and psychological therapies for the treatment of anxiety and depression in people with COPD, one of which has already been published (Usmani 2011).

Objectives

To assess the effects of psychological therapies for the treatment of anxiety disorders in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including cross‐over trials and cluster‐randomised trials.

Types of participants

Participants were adults over 40 years of age (as clinically significant COPD is generally seen in people more than 40 years of age (GOLD 2013)) of either gender and of any ethnicity, diagnosed with COPD and a recognised anxiety disorder or anxiety symptom(s).

The COPD diagnosis needed to have been made objectively, for example, according to GOLD (Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) criteria, or similar criteria (e.g. FEV1/FVC less than 0.70).

The anxiety disorder (e.g. generalised anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder (PD), agoraphobia, neurocirculatory asthenia, obsessive‐compulsive disorder (OCD), phobic disorders) needed be defined either using established diagnostic criteria, for example, DSM criteria (APA 1994) or anxiety symptoms identified using a formal psychological instrument, for example, Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Beck 1961; BAI 1993) or Hospital Anxiety & Depression Scale (Zigmond 1983) at the time of recruitment to the trial.

We included participants with co‐morbid mental health disorders. Anxiety did not need to be the primary mental health disorder for included participants as long as they had formally diagnosed or symptomatic anxiety (as diagnosed or assessed by a formal criteria or a validated tool).

We excluded studies that only assessed psychological therapies for the treatment of depression in people with COPD, as these will be covered by a separate review.

Types of interventions

We included studies assessing any form of psychological therapy for the treatment of anxiety disorders in people with COPD where this was compared with either no intervention or education only. Studies in which the psychological therapy was delivered in combination with another intervention (co‐intervention) were included only if there was a comparison group that received the co‐intervention alone.

Experimental interventions:

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) (e.g. problem solving, rational emotive therapy)

Third Wave CBT (i.e. acceptance and commitment therapy, compassionate mind training, functional analytic psychotherapy, mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy, behavioural activation, meta‐cognitive therapy and dialectical behavioural therapy)

Behavioural therapy (e.g. behaviour modification, assertiveness training)

Psychodynamic therapy (e.g. insight‐oriented therapy, group psychotherapy)

Humanistic therapy (e.g. expressive therapy, supportive therapy)

Integrative therapy (e.g. cognitive analytical therapy)

Comparators:

No intervention (i.e. waiting list and usual care)

Education only (education (written or oral), such as provision of information about physical and mental health issues during a medical consultation or during a visit with a nurse where no formal counselling or psychological therapy was provided)

Co‐intervention (only if the same co‐intervention was used in the intervention arm of the study). The co‐interventions considered were pharmacotherapy and pulmonary rehabilitation.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Change in anxiety symptoms as measured by a standardised or validated anxiety measure, for example, State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (Spielberger 1970), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Zigmond 1983) and the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Beck 1961; BAI 1993). These scales generated a total score which were recorded for all pair‐wise comparisons as short‐term follow up data (up to and including six months) or long term follow‐up data (greater than six months), or both.

Adverse events

Secondary outcomes

Each of the secondary outcomes were assessed based on a validated assessment scale. The secondary outcomes measured included:

Change in quality of life, for example, the St George’s respiratory questionnaire (SGRQ) (Jones 1991). Generic, validated quality‐of‐life measures were also considered

Difference in exercise tolerance, for example, the six‐minute walk test (Butland 1982)

Change in dyspnoea scores, for example, the Borg scale (Borg 1982)

Change in length of stay or readmission rate

Change in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1)

Timing of outcome assessment

Time frames were defined as short‐term (up to three months), medium‐term (three to six months) and long‐term follow‐up (more than six months). The primary time point used in the 'Summary of findings' table is the longest reported follow‐up by each included study. The range of follow‐ups for each outcome is described in the 'Summary of findings' table and in the Results section of the review.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Cochrane Specialised Registers

Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Register (CCMDCTR)

Cochrane Common Mental Disorders maintains a specialised register of RCTs, the CCMDCTR. This register contains over 40,000 reference records (reports of RCTs) for anxiety disorders, depression, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, self‐harm and other mental disorders within the scope of this Group. The CCMDCTR is a partially studies‐based register with more than 50% of reference records tagged to c. 12,500 individually PICO‐coded study records. Reports of trials for inclusion in the register are collated from (weekly) generic searches of MEDLINE (1950‐), Embase (1974‐) and PsycINFO (1967‐), quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library, and review‐specific searches of additional databases. Reports of trials are also sourced from international trials registries, drug companies, the handsearching of key journals, conference proceedings and other (non‐Cochrane) systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. Details of CCMD's core search strategies (used to identify RCTs) can be found on the Group's website with an example of the core MEDLINE search displayed in Appendix 1.

CCMD's Information Specialist cross‐searched the CCMDCTR‐Refs and CCMDCTR‐Studies registers (to 14 August 2015) using the following terms:

(anxi* or *phobi* or PTSD or post‐trauma* or posttrauma or “post trauma*” or "combat disorder" or panic or OCD or obsess* or compulsi* or GAD or stress* or distress* or neurosis or neuroses or neurotic or psychoneuro*) AND ((obstruct* and (pulmonary or lung* or airway* or airflow* or bronch* or respirat*)) or COPD or emphysema or (chronic* and bronchiti*))

Cochrane Airways' Register (CAGR)

Cochrane Airways' Specialised Register is also derived from systematic searches of bibliographic databases including: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; in the Cochrane Library), MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, AMED, and PsycINFO, and handsearching of respiratory journals and meeting abstracts (details of the CAGR can be found on the Group's website).

Cochrane Airways' Information Specialist searched CAGR records coded as 'COPD' for 'Anxiety Disorders' as listed above (14 August 2015).

An additional search of CENTRAL and PsycINFO was conducted at this time, to ensure no records had been missed from these databases in the creation of the CCMDCTR and CAGR (Specialised Registers) (Appendix 2).

Searching the CAGR, CENTRAL and PsycINFO did not retrieve any additional studies beyond those identified by the CCMDCTR, so in 2015 we decided to conduct update searches on the CCMDCTR alone.

National and international trials registers

Complementary searches were conducted on the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Searching other resources

We handsearched reference lists of retrieved, relevant articles to identify any other potentially relevant articles. We contacted authors of potentially‐included studies for raw data or unpublished data where required.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two of three review authors (either KC, ZU or KHM) independently assessed all citations generated from the search strategies to determine whether they satisfied the Criteria for considering studies for this review, through screening of the title, abstract and descriptors. Two of three review authors, as above, retrieved and independently examined the full texts of studies identified as potentially relevant for final inclusion. We resolved disagreements through discussion and by involving a third party if necessary (BS or AD).

Data extraction and management

Two independent review authors (a combination of ZU, KC and KHM) extracted the following data using a standardised and piloted data extraction form, for each included study. The review authors resolved any discrepancies by discussion between themselves and if needed, a third party (BS or AD).

Study eligibility

Study design, population group and description of psychological therapy.

Participants

Number of participants, age, gender distribution, ethnicity and co‐morbidities.

Interventions

Description of intervention, duration, intensity, who it was delivered by.

Main comparisons

Comparison 1: Psychological therapies versus no intervention

Comparison 2: Psychological therapies versus education

Comparison 3: Psychological therapies and co‐intervention versus co‐intervention alone

We stratified these comparisons according to psychological therapy, however, we did not perform an overall pooled estimate for intervention effectiveness for all the psychological therapies in each of these comparisons, that is, we used sub‐totals only in the analyses.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias for all the included studies using the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias, which is a domain‐based evaluation (Higgins 2011a). We assessed risk of bias as 'Low risk of bias', 'High risk of bias' and 'Unclear risk of bias' as per the guidelines in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, table 8.5.c (Higgins 2011a). We resolved any conflicts in the assessment either by consensus or by referring to a third party. The domains we evaluated were:

Sequence generation

Methods considered adequate included: random number table, computer random‐number generator, coin toss, shuffling cards or envelopes, throwing dice and drawing lots.

Allocation concealment

Methods considered adequate included: central allocation (phone, web, pharmacy), sequentially‐numbered identical drug containers and serially‐numbered sealed and opaque envelopes.

Blinding (of participants)

We considered blinding adequate if: trial authors mentioned that participants were blinded to the intervention, although for psychological therapies this was unlikely due to the difficulties associated with delivery of communication‐based interventions.

Blinding (of outcome assessors)

We considered blinding adequate if: authors mentioned that outcome assessors were blinded to sequence allocation.

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data on the grounds of whether the incomplete outcome data were adequately addressed or not, as per the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions section 8.12.

Selective outcome reporting

We considered studies to be at low risk of bias if a protocol was available and all prespecified outcomes were reported in the prespecified way, or in the absence of a protocol, if all expected outcomes were reported (and as per recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, table 8.5.c.

Other bias

We considered studies at a low risk of other bias if they were conducted in such a way as to ensure no other influencing factors that could potentially affect the outcome were evident. Examples of other biases included: extreme baseline imbalances for participants or outcomes, contamination of the intervention or control group, and selective recruitment of study participants.

We have presented the results of the 'Risk of bias' assessment in a 'Risk of bias' table and described them narratively within the results of the review.

Measures of treatment effect

Continuous data

We summarised available data by either mean differences (MD) or standardised mean differences (SMD) where appropriate, using mean values and standard deviations. We consulted a statistician for additional support where required (AE) (Deeks 2011).

Dichotomous data

Had dichotomous data been presented we would have calculated odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. We would have presented data as either final values (post‐intervention) or as change from baseline, if we had not been able to retrieve raw data from the trialists (Deeks 2011).

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

Cluster‐randomised controlled trials, that is, trials in which outcomes relate to individual participants, whilst allocation to the intervention is by hospital, clinic or practitioner, may introduce unit of analysis errors. Using statistical methods that assume, for example, that all participants’ chances of benefit are independent, ignores the possible similarity between outcomes for participants seen by the same provider. This may underestimate standard errors and give misleadingly narrow confidence intervals, leading to the possibility of a type 1 error (Altman 1997). For cluster‐randomised studies, we performed analyses at the level of individuals, whilst accounting for the clustering in the data using a random‐effects model for pooled meta‐analysis, as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (chapter 16.3.3) (Higgins 2011b) (checked by a statistician (AE)). For those studies that did not adjust for clustering, we replaced the actual sample size with the effective sample size (ESS), calculated using a rho = 0.02 (as per Campbell 2000).

Cross‐over trials

We extracted data from cross‐over studies for the first phase only (pre‐cross‐over), due to the potential for a significant carry‐over effect for psychological therapies.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

We considered multi‐arm trials for inclusions provided that there was an intervention arm with any of the interventions mentioned in the experimental group above and a control arm with any of the comparators mentioned above. In the case of multi‐arm trials we included each pair‐wise comparison separately, but with shared intervention groups divided out approximately evenly among the comparators. However, in cases where the intervention groups were deemed similar enough to be pooled, we combined the groups using appropriate formulae in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (table 7.7.a for continuous data (Higgins 2011c) and chapter 16.5.4 for dichotomous data, (Higgins 2011b)).

Dealing with missing data

We evaluated missing information regarding participants on an available case‐analysis basis as described in chapter 16.2.2 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b). Had there been statistics essential for analysis missing (e.g. group means and standard deviations (SDs) for both groups not reported) that could not be calculated from other data, we would have attempted to contact the study authors to obtain the data. Any loss of participants that occurred before the baseline measurements were performed would not have affected the eventual outcome data of the study. Any losses after the baseline measurements were taken may have affected trial validity. For dropouts at the initial phase of a trial (by the end of the second week of intervention/placebo administration), we did not include their data and for these studies we used the final data from the completers only. For participants who dropped out after the second week or with unclear dropout time, we used the last observation carried forward (LOCF) as presented in the publications, or had the data been missing we would have obtained raw data. Had we been unsuccessful in obtaining this raw data, we would have reported the missing data under 'other' sources of bias in the 'Risk of bias' tables and discussed the details in the text.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We expected this review to have some heterogeneity, with factors such as baseline severity of anxiety, severity of underlying COPD or consistency of diagnostic thresholds for COPD, or both, time of measurement of results and varying measuring tools used to assess outcomes contributing. We used the Chi2 (Deeks 2011) and I2 statistics (Higgins 2003) to quantify inconsistency across studies in combination with visual inspection of the data for differences between studies (e.g. types of interventions, participants etc.). Thresholds for the interpretation of the I2 statistic can be misleading, since the importance of inconsistency depends on several factors (Deeks 2011). These include magnitude and direction of the effect and strength of the evidence for heterogeneity, for example the P value from the Chi2 test, or a confidence interval for I2. For the purpose of this review, we considered an I2 statistic representing substantial or considerable heterogeneity for further investigation through subgroup analyses to examine possible causes, as per chapter 9.5.2 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011). The overlapping bands for the I2 statistic are:

0% to 40%: might not be important;

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

Since there were fewer than 10 studies, where we identified reporting biases we extrapolated them within the 'other bias' section in the 'Risk of bias' tables. If in future versions of this review we include more than 10 studies in any analysis, we will assess potential reporting biases using a funnel plot. Asymmetry in the plot might be attributed to publication bias, but may well be due to true heterogeneity or a poor methodological design. In case of asymmetry, contour lines may be included corresponding to perceived milestones of statistical significance (P = 0.01, 0.05, 0.1 etc.) to funnel plots, which may help to differentiate between asymmetry due to publication bias from that due to other factors (Sterne 2011).

Data synthesis

We pooled the extracted data in meta‐analyses using the random‐effects model to allow for expected heterogeneity (due to expected differences in the interventions and populations). We assessed all the included studies for inclusion in the primary analyses, and performed a sensitivity analysis for studies which were at an unclear or high risk of bias for sequence generation and allocation concealment, and for studies involving participants who had significant co‐morbidities, for example, dementia or severe heart failure. We performed separate meta‐analyses for intervention subgroups as defined under Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity (Deeks 2011). For trials reporting data at more than one point in time, we extracted data from the final follow‐up period reported by trialists. We analysed data using Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) software (RevMan 2014).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We have prespecified subgroups to investigate this heterogeneity to reduce the likelihood of spurious findings, first by limiting the number of subgroups investigated and second by preventing knowledge of the studies’ results influencing which subgroups are analysed (Deeks 2011). These contributing factors were identified as relevant in our previous completed review for pharmacological interventions for anxiety in COPD (Usmani 2011). We have described all included studies in table and narrative form reporting on study design, population, intervention characteristics and outcome measures.

We performed subgroup analyses for the above‐mentioned psychological therapies according to:

duration of intervention (e.g. 0 to 3 months, 3 to 6 months, > 6 months); and

severity of anxiety symptoms (i.e. mild, moderate and severe accepting the study authors' definition of this).

These subgroups permit an examination into the possible causes of heterogeneity, however their primary objective is to extrapolate data for the purposes of forming hypotheses.

Sensitivity analysis

Had there been sufficient data we would have conducted a sensitivity analysis to examine the effects of methodological decisions taken throughout the review process, particularly in regard to the inclusion criteria (Deeks 2011). We would have tested the validity and robustness of the findings by removing studies based on the following criteria:

inadequate sequence generation;

inadequate allocation concealment;

significant attrition of the study population (20% or higher attrition);

studies on populations with significant co‐morbidities;

cluster‐randomised trials;

cross‐over studies;

studies containing data imputed by the review authors.

'Summary of findings' table

As there were only three included studies in this review, the 'Summary of findings' table was limited only to the data reported under comparison 3 (psychological interventions and co‐interventions versus co‐interventions alone). Follow‐up periods presented in the 'Summary of findings' table relate to the final follow‐up reported in each study for every outcome measure (range of follow‐up is specified in the 'Summary of findings' table). We used only published data to populate information in the 'Summary of findings' table. We used the GRADE approach to assess the quality of evidence (GRADE 2013). The source of all information used in the table is from the publications only. The first four outcomes listed above under Types of outcome measures are the same outcomes used in the 'Summary of findings' table (Schünemann 2011).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

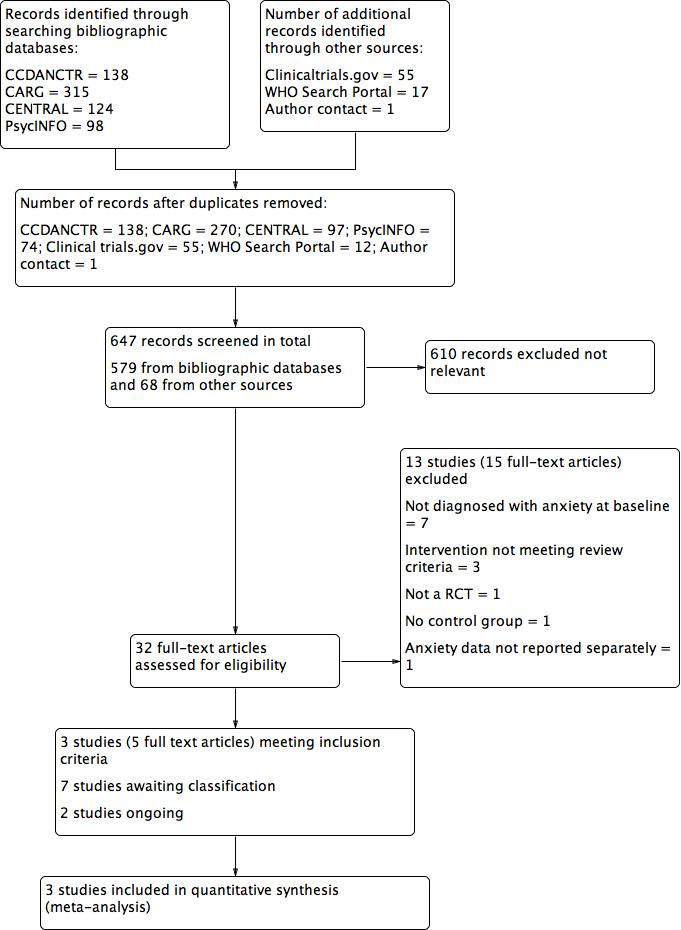

We identified a total of 675 records from searching Cochrane specialised registers and bibliographic databases (to 14th of Aug 2015) with 579 short‐listed once duplicates were removed. We retrieved an additional 72 records from screening clinical trials registries and identified one citation via author contact. This resulted in a total of 647 records screened and 32 full‐text articles (including online protocols) identified as potentially eligible. From these, we included three studies (five full‐text articles) in the final qualitative and quantitative analyses. Seven studies are awaiting classification and two were ongoing at the time of review completion (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

We included three studies in this review, with the following characteristics (see also Characteristics of included studies).

Design

All three studies were single‐centre, parallel RCTs coming from Brazil (de Godoy 2003), Norway (Hynninen 2010) and the USA (Kunik 2008).

Sample sizes

Each study reported difficulties with sample size, two being unable to meet the target recruitment number (Kunik 2008; Hynninen 2010) and the third (de Godoy 2003) not reporting a prespecified sample size calculation. Samples sizes ranged from n = 30 in de Godoy 2003, n = 51 in Hynninen 2010 and the largest being n = 238 in Kunik 2008.

Setting

Specific settings for psychological therapies were not described in detail, however two studies did report group settings for intervention delivery with an average of five participants in each session for the Hynninen 2010 study and up to 10 participants in each session for the Kunik 2008 study, whilst the setting for de Godoy 2003 was unclear. Participants of the Kunik 2008 study were recruited from a Veterans Affairs hospital, whilst the Hynninen 2010 study used outpatients from a University hospital and de Godoy 2003 recruited from a pulmonary rehabilitation clinic.

Participants

All three studies recruited people with diagnosed COPD and anxiety using a validated tool. Although all studies recruited participants from the hospital setting, two studies ( Kunik 2008; Hynninen 2010) also used external advertisements/flyers to attract participants into the study. The male to female ratio in the Hynninen 2010 study was similar, however there were more men recruited into both the de Godoy 2003 study (22 men and 8 women) and the Kunik 2008 study (226 men and 9 women). Only the Kunik 2008 study reported on participant ethnicity with 192 white, seven Hispanic and 38 black participants recruited. Of the 256 eligible participants for the Kunik 2008 study, 238 were randomised but only 181 attended their first session (24% attrition before the intervention commenced).

Interventions and comparators

de Godoy 2003 used psychotherapy in addition to exercise, physiotherapy and education in comparison to exercise, physiotherapy and education alone. Hynninen 2010 and Kunik 2008 both employed Cognitive and Behavioural Therapy (CBT) in addition to co‐interventions of telephone counselling and group discussions for each study respectively. The control population of the Hynninen 2010 study used an enhanced standard care programme for COPD with regular telephone contacts whilst the Kunik 2008 control group received COPD education. Although we defined the control of the Kunik 2008 study to be a co‐intervention, it could also have been considered as an education‐only intervention. However, due to the small number of included studies in this review (three studies) we classified all studies as co‐interventions, which also facilitated meta‐analysis and interpretation of results.

Outcomes

All three studies measured anxiety using the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI). A number of secondary outcomes were also assessed including depression, quality of life, exercise capacity and service utilisation.

Excluded studies

We excluded 13 of the potentially eligible studies (15 full‐text articles) from the review due to no diagnosis of anxiety at baseline (n = 7; Aubuchon 1990; Blake 1990; Gift 1992; Livermore 2010a; Williams 2011; Doyle 2013; Blumenthal 2014), the intervention not meeting the criteria for inclusion as defined in the protocol (n = 3) due to being either an intervention of progressive muscle relaxation without a psychological intervention (Lolak 2008), or due to being a multi‐component intervention (Pommer 2012;Yang 2015), and we excluded the remaining three studies because they were not randomised (Cully 2007), did not have a control group (de Godoy 2005) or did not report anxiety data separately (Lamers 2010). See Characteristics of excluded studies.

Ongoing studies

We identified seven studies as ongoing at the time of review completion. See Characteristics of ongoing studies for individual trial details. We identified all the studies through either published protocols in manuscript format or via online clinical trials registries. It is unclear if all inclusion/exclusion criteria as outlined in the protocol of this review will be met for each study due to the limitations in reported data. One study is reported to use mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy (Farver‐Vestergaard 2014), whilst the remaining six studies specifically report the use of CBT.

Studies awaiting classification

We classified two studies as 'awaiting classification'. One study was a Chinese paper that could not be translated in time for inclusion in this review (Shao 2003). Fifty‐four people with COPD were randomised to a behavioural therapy with psychological and somatic components or usual care, however, it is unclear if the presence of baseline anxiety was an inclusion criteria or if people with COPD were formally diagnosed as per the requirements for inclusion within this review (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification). For the other study (Livermore 2015) there is a question surrounding baseline anxiety scores for individual participants to determine eligibility of subjects for this review. We will continue to attempt to contact the study authors and, if no response has been received by the time of the next update, this study will be moved to the excluded category.

Risk of bias in included studies

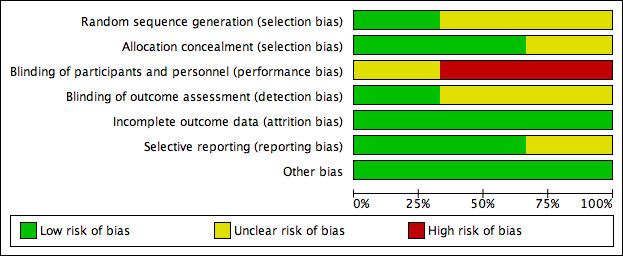

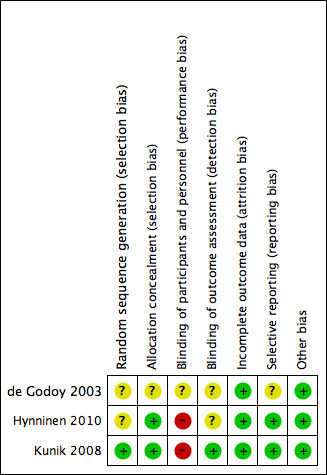

For details of the risk of bias judgements for each study, see Characteristics of included studies. We have presented a graphical representation of the overall risk of bias in included studies in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Sequence generation (selection bias)

Only one study adequately reported on method of sequence generation (Kunik 2008) using a computer program with blocks to provide appropriately equal numbers per class of COPD. The instructor assigned treatment to the code initially through flipping a coin. The two remaining studies reported randomisation as occurring, however, they did not describe their methods in detail.

Allocation

Two studies sufficiently reported allocation concealment using an external statistician to provide treatment codes to the study co‐ordinator once sufficient numbers of participants for two classes had been recruited (Kunik 2008) and by using numbered containers that were identical in appearance for the two groups (Hynninen 2010). The de Godoy 2003 study did not report any details of allocation concealment.

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias)

Blinding to psychological therapies can be challenging unless an active comparator arm, for example, education or sham interventions is included. Two studies did not blind participants or personnel to the treatment allocation, whilst the third study (de Godoy 2003) reported that group 1 was blinded in relation to the activities of group 2 and vice versa.

Blinding of outcome assessors (detection bias)

Outcome assessor blinding was unclear in two studies and assessed to be a low risk of bias in the Kunik 2008 study as authors reported that study personnel performing assessments were blinded to treatment condition.

Incomplete outcome data

All three studies had a low risk of bias for incomplete outcome data as they used intention‐to‐treat analyses. Moreover, any missing data were reported to be accounted for in the analyses.

Selective reporting

Selective reporting was a low risk in two studies due to the availability of prespecified published protocols, allowing adequate comparison of prespecified outcomes and those reported in the publications. We assessed the de Godoy 2003 study as having an unclear risk of bias due to the inability to review a prespecified protocol.

Other potential sources of bias

Had there been a sufficient number of studies to properly assess reporting bias, we would have assessed potential reporting biases using a funnel plot. Asymmetry in the plot may have been attributed to publication bias, but may well be due to true heterogeneity or a poor methodological design. In case of asymmetry, contour lines would have been included corresponding to perceived milestones of statistical significance (P = 0.01, 0.05, 0.1 etc.) to funnel plots, which may have helped to differentiate between asymmetry due to publication bias from that due to other factors (Higgins 2011a). No additional formal testing for funnel plot asymmetry would have been performed.

Although we defined the control of the Kunik 2008 study to be a co‐intervention, it could also have been considered as an education‐only intervention. However, due to the small number of included studies in this review (three studies) we pooled all studies together to facilitate meta‐analysis.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Comparison 1: Psychological therapies versus no intervention

There were no data for this comparison.

Comparison 2: Psychological therapies versus education

There were no data for this comparison.

Comparison 3: Psychological therapies and co‐intervention versus co‐intervention alone

Three studies including 319 participants contributed data to this comparison. See also: Table 1.

Primary outcomes

Change in anxiety symptoms

Psychological therapies were observed to be more effective for the treatment of anxiety compared with co‐interventions or usual care (mean difference (MD) ‐4.41, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐8.28 to ‐0.53; participants = 319; I2 = 62%; P = 0.03; Analysis 1.1; Figure 4). However, there was substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 62%), which limits the reliability of the findings. In the study by de Godoy 2003 the psychotherapy group started with a BAI score of 12.9 + 6.9, whilst the control population was 10.9 + 9.8. Authors reported a change from baseline in the intervention arm (P < 0.001), though no change was observed from baseline to follow‐up in the control group (9.2 + 8.6; P = 0.15).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Psychological therapies versus co‐intervention, Outcome 1 Anxiety.

4.

Forest plot of comparison 1: Psychological therapies versus co‐intervention, outcome: 1.1 Anxiety

Adverse events

No adverse events were reported for any of the included studies.

Secondary outcomes

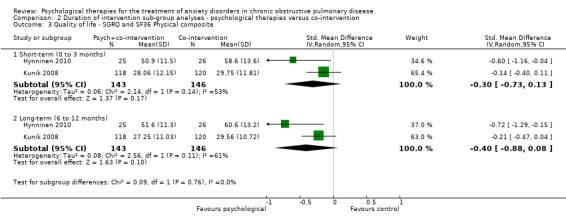

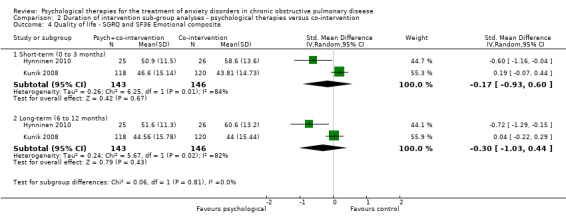

Change in quality of life

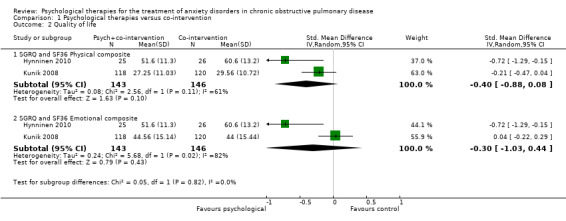

Two studies with 289 participants reported quality of life through use of three different tools, being SGRQ, SF36 and CRQ. Psychological interventions were observed to be more effective compared to the control population for the combination of SGRQ and the physical composite of SF36 (standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.40, 95% CI ‐0.88 to ‐0.08; participants = 289; studies = 2; I2 = 61%; P = 0.10). No evidence of any effect was observed for SGRQ and the emotional composite of SF36 (SMD ‐0.30, 95% CI ‐1.03 to 0.44; participants = 289; studies = 2; I2= 82%); Analysis 1.2). Of note substantial heterogeneity was observed in these analyses. Alongside SF36, CRQ was also reported in the Kunik 2008 study with only one of the eight categories producing results in favour of the CBT group for general health (end of treatment eight‐week score: intervention arm mean 34.14 + 28.53 and control arm mean 37.76 + 27.74; P = 0.05).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Psychological therapies versus co‐intervention, Outcome 2 Quality of life.

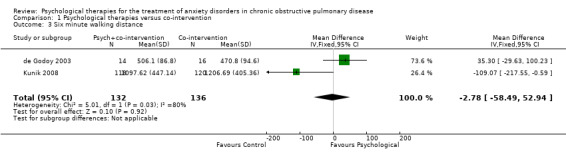

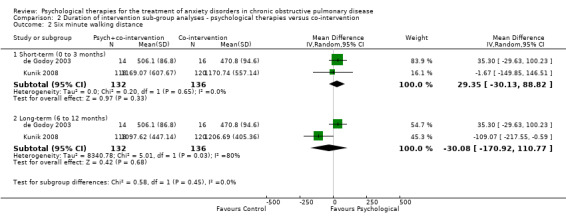

Difference in exercise tolerance

Compared with the control, there was no significant difference in the number of steps taken as measured by the Six Minute Walking Distance (6MWD) when engaged in psychological therapies: (MD ‐2.78, 95% CI ‐58.49 to 52.94, participants = 268; studies = 2; I2 = 80%; Analysis 1.3). The Kunik 2008 study, which was included in the meta‐analysis, examined 6MWD at eight weeks' (post‐intervention) and again at 12 months' follow‐up with a difference in favour of the control arm at 12 months (P = 0.05). However, the study authors reported that group means at the beginning of the follow‐up period were not equal (P < 0.01), contributing to the spurious finding.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Psychological therapies versus co‐intervention, Outcome 3 Six minute walking distance.

Exercise capacity in the psychotherapy group of the de Godoy 2003 study improved almost twice as much from baseline as the control population (P = 0.11). The study authors reported that it may have been the improvement in physical functioning that facilitated improvement in the psychological variables, rather than the psychotherapy itself. ).

Change in dyspnoea scores

Only one study (Kunik 2008) reported dyspnoea via CRQ, with an improvement in the CBT group over that of control at eight‐week end‐of‐treatment follow‐up (intervention group mean 3.36 + 1.64; control group mean 3.51 + 1.59; P = 0.02).

Change in length of stay or readmission rate

No studies provided data specifically on length of stay or hospital readmission rates. However the Kunik 2008 study did indirectly examine this by tracking the number of treatment visits pre and post study. No differences were observed for the ratio of pre treatment to post treatment between groups for outpatient visits, hospital admissions, mental health visits and emergency visits per month, per participant.

Change in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1)

No studies reported on FEV1. Whilst FEV1 is helpful to note the severity of COPD, as with most interventions few if any other therapies, including pharmacotherapies significantly improve FEV1 in COPD.

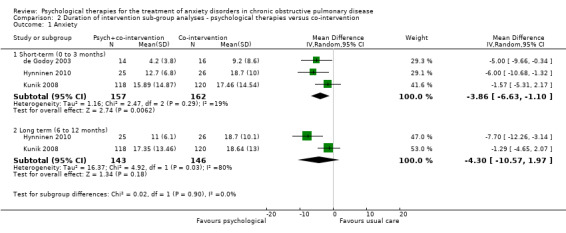

Subgroup analyses

We carried out subgroup analyses for duration of follow‐up due to multiple follow‐up periods reported in the Kunik 2008 study (eight weeks, i.e. post treatment, and 12 months) and the Hynninen 2010 study (seven weeks and six months). In both anxiety and quality‐of‐life outcomes, results became better (favoured intervention more) with longer follow‐up compared to immediately post treatment. In the case of anxiety, short‐term (0 to 3 month follow‐up) benefits were seen in favour of the intervention arm with a MD of ‐3.86; 95% CI of ‐6.63 to ‐1.10 and P = 0.006 (I2 = 19%), whilst these findings were not maintained long‐term (6 to 12 months; MD ‐4.30 with 95% CI of ‐10.57 to 1.97 and P = 0.18; I2 = 80%; Analysis 2.1). We did not note any evidence of an effect for exercise capacity (Analysis 2.2) or quality of life (Analysis 2.3, Analysis 2.4), even after sub group analyses.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Duration of intervention sub‐group analyses ‐ psychological therapies versus co‐intervention, Outcome 1 Anxiety.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Duration of intervention sub‐group analyses ‐ psychological therapies versus co‐intervention, Outcome 2 Six minute walking distance.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Duration of intervention sub‐group analyses ‐ psychological therapies versus co‐intervention, Outcome 3 Quality of life ‐ SGRQ and SF36 Physical composite.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Duration of intervention sub‐group analyses ‐ psychological therapies versus co‐intervention, Outcome 4 Quality of life ‐ SGRQ and SF36 Emotional composite.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Based on the small number of included studies within this review (only three), it is difficult to draw any meaningful and reliable conclusions. Some evidence of improvement in anxiety was observed with a benefit in favour of the psychological therapy arm, however, the presence of substantial heterogeneity and low quality of the evidence limits the reliability of these findings. Six‐minute walking distance was analysed in two of the three included studies, producing no evidence of any effect. As such there is insufficient information to draw reliable conclusions about whether psychological therapies are beneficial for people with COPD with anxiety (see Table 1).

Of note however, sub‐group analyses for duration of follow‐up for both anxiety and quality of life indicate the potential for greater benefits in favour of the psychological intervention given more time (in the presence of wider confidence intervals due to small number of relevant studies). Although intervention treatment lasted for similar periods of time (eight weeks and seven weeks for the Kunik 2008 and Hynninen 2010 studies respectively), participants within both studies did better at long‐term follow‐up in comparison to immediately post‐intervention. This suggests that psychological interventions may take longer to work than during the treatment phase alone.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

A limitation of this review is that all three included studies recruited participants with both anxiety and depression, not just anxiety, which may confound the results, as presence of co‐morbid depression may have over estimated or under estimated the effect of intervention in different participants (based on different levels of severity of anxiety and depression), the details of which are out of the scope of this review. Also important to note is that the majority of the participants of this review were men. From the prespecified outcomes identified as being important for this review, none of the three included studies included as an outcome either adverse events or objective markers of lung disease, such as FEV1. Length of stay and readmission rate was also not effectively evaluated in any of the three studies. Considering the small number of included studies and limited reporting for each of the outcomes, the overall completeness and applicability of evidence is poor. As such, findings from this review should be interpreted with caution and the questions posed in this review remain unanswered.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of evidence in this review overall was low, with two of the three studies having prespecified protocols available for comparison to methods, and outcomes reported on within the final publications. Although all studies reported that randomisation occurred, only one provided a description of the methods for sequence generation. Allocation concealment was adequately reported in two studies whilst the third was unclear.

Consistency

Substantial heterogeneity was identified in all meta‐analyses across studies, suggesting the possibility of these being true differences in the underlying treatment effect. However, as we only included three studies, it is difficult effectively to examine consistency. As such, the quality of results was downgraded due to inconsistency.

Indirectness

Due to the small number of included studies and broad classification of psychological therapies, it is likely that this review contains indirectness through varying interventions, comparators, populations and even outcomes and the use of different reporting tools.

Imprecision

Imprecision was identified particularly when examining exercise capacity with the presence of wide confidence intervals around the treatment effect. This is of particular concern when there are few studies with few participants attempting to determine the results of a particular outcome. As such the quality of the 6MWD outcome was downgraded due to imprecision.

Publication bias

It is difficult to determine the presence of publication bias and systematic underestimation or overestimation of the underlying beneficial or harmful effect due to inclusion of only three studies. Screening of online clinical trial registries allows identification of studies regardless of a positive or negative effect for the treatment, which may reduce the possibility of publication bias. The identification of six ongoing studies and one awaiting classification is reassuring, however, there is the possibility of negative studies being missed before publication of protocols became mandatory.

Potential biases in the review process

As the three studies identified for inclusion within the review were from three different countries and different healthcare settings, it is difficult to determine the extent to which the results can be generalised. In particular, all three studies reported issues with either prespecified sample sizes not being met ( Kunik 2008; Hynninen 2010) or a small sample limiting the ability to draw reliable conclusions from the results (de Godoy 2003, in which there was no mention of sample size calculations). Authors in the Hynninen 2010 trial reported that, due to the low sample size of their study, it was possible that significant differences had not been detected when they existed. They also reported that it may have been possible to detect a difference on anxiety symptoms due to age if a larger sample size had been achieved. Low recruitment numbers in the Kunik 2008 study was reported to be due to difficulties often occurring with recruitment of Veteran Affairs' patients due to greater prevalence of physical and mental health problems. Authors of the de Godoy 2003 study suggested that, due to the relatively small sample size, the conclusions from their study should only be considered as tentative.

An additional limitation relates to risk of bias categories deemed to be unclear by review authors, as we did not contact individual study authors for clarification or to obtain further information.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Meta‐analyses attempting to examine the impact of psychological interventions for anxiety in people with COPD have consistently identified a lack of methodologically rigorous evidence to support treatment efficacy (Rose 2002; Mikkelsen 2004; Baraniak 2011), resulting in the inability to draw reliable conclusions. A 2014 overview examining the prevalence, impact and management of depression and anxiety in COPD also found that the quality of evidence underpinning treatment varied considerably (Panagioti 2014). The authors found that interventions that included pulmonary rehabilitation with or without psychological components improved symptoms of depression and anxiety in COPD. They considered cognitive and behavioural therapy and, though treatment effects were small, they concluded that this type of therapy could potentially lead to greater benefits in anxiety for people with COPD if embedded in multi‐disciplinary collaborative frameworks. Another systematic review and meta‐analysis of complex interventions for depression and anxiety in COPD identified 28 studies for inclusion (Coventry 2013). Subgroup analyses identified small but non‐significant effects on self‐reported anxiety symptoms post‐treatment for cognitive and behavioural interventions (SMD ‐0.17; 95% CI ‐0.35 to 0.01; 7 studies) and relaxation (SMD ‐0.18; 95% CI ‐0.67 to 0.30; 3 studies), but observed no evidence of any effect for self‐management education (SMD ‐0.00; 95% CI ‐0.17 to 0.16; 5 studies). This review observed an improvement with the intervention for multi‐component exercise training, though the sample included substantial heterogeneity (SMD ‐0.47; 95% CI ‐0.66 to ‐0.28; P = 0.002; 14 studies; I2 = 63.3%; Coventry 2013).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Based on the small number of included studies identified for inclusion within this review (only three), it is difficult to draw any meaningful and reliable conclusions. All three included studies recruited participants with both anxiety and depression, not just anxiety (which may confound the results) and compared psychotherapy with co‐intervention versus co‐intervention alone. Some evidence of improvement in anxiety was observed in the psychological therapy arm, however, the low quality of the evidence and presence of substantial heterogeneity limits our ability to draw any conclusions from these findings.

Implications for research.

There is a need for further research trials to evaluate the role of psychotherapy for anxiety in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) using a population with anxiety symptoms and COPD. Given problems with sample size, participant selection and only one type of psychotherapy in current studies, future researchers might need to consider multi‐centre studies with different modalities of psychotherapy other than cognitive behavioural therapy. New research should also assess adverse events, the effect on hospital admissions, length of stay and long‐term effects on quality of life produced by psychotherapy.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the assistance of the editors and staff of the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group.

CRG Funding Acknowledgement

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) is the largest single funder of Cochrane Common Mental Disorders.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the review authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CCMDCTR ‐ core MEDLINE search

Core search strategy used to inform Cochrane Common Mental Disorders' specialised register: OVID Medline A weekly search alert based on condition + RCT filter only 1. [MeSH Headings]: eating disorders/ or anorexia nervosa/ or binge‐eating disorder/ or bulimia nervosa/ or female athlete triad syndrome/ or pica/ or hyperphagia/ or bulimia/ or self‐injurious behavior/ or self mutilation/ or suicide/ or suicidal ideation/ or suicide, attempted/ or mood disorders/ or affective disorders, psychotic/ or bipolar disorder/ or cyclothymic disorder/ or depressive disorder/ or depression, postpartum/ or depressive disorder, major/ or depressive disorder, treatment‐resistant/ or dysthymic disorder/ or seasonal affective disorder/ or neurotic disorders/ or depression/ or adjustment disorders/ or exp antidepressive agents/ or anxiety disorders/ or agoraphobia/ or neurocirculatory asthenia/ or obsessive‐compulsive disorder/ or obsessive hoarding/ or panic disorder/ or phobic disorders/ or stress disorders, traumatic/ or combat disorders/ or stress disorders, post‐traumatic/ or stress disorders, traumatic, acute/ or anxiety/ or anxiety, castration/ or koro/ or anxiety, separation/ or panic/ or exp anti‐anxiety agents/ or somatoform disorders/ or body dysmorphic disorders/ or conversion disorder/ or hypochondriasis/ or neurasthenia/ or hysteria/ or munchausen syndrome by proxy/ or munchausen syndrome/ or fatigue syndrome, chronic/ or obsessive behavior/ or compulsive behavior/ or behavior, addictive/ or impulse control disorders/ or firesetting behavior/ or gambling/ or trichotillomania/ or stress, psychological/ or burnout, professional/ or sexual dysfunctions, psychological/ or vaginismus/ or Anhedonia/ or Affective Symptoms/ or *Mental Disorders/

2. [Title/ Author Keywords]: (eating disorder* or anorexia nervosa or bulimi* or binge eat* or (self adj (injur* or mutilat*)) or suicide* or suicidal or parasuicid* or mood disorder* or affective disorder* or bipolar i or bipolar ii or (bipolar and (affective or disorder*)) or mania or manic or cyclothymic* or depression or depressive or dysthymi* or neurotic or neurosis or adjustment disorder* or antidepress* or anxiety disorder* or agoraphobia or obsess* or compulsi* or panic or phobi* or ptsd or posttrauma* or post trauma* or combat or somatoform or somati#ation or medical* unexplained or body dysmorphi* or conversion disorder or hypochondria* or neurastheni* or hysteria or munchausen or chronic fatigue* or gambling or trichotillomania or vaginismus or anhedoni* or affective symptoms or mental disorder* or mental health).ti,kf.

3. [RCT filter]: (controlled clinical trial.pt. or randomised controlled trial.pt. or (randomi#ed or randomi#ation).ab,ti. or randomly.ab. or (random* adj3 (administ* or allocat* or assign* or class* or control* or determine* or divide* or distribut* or expose* or fashion or number* or place* or recruit* or subsitut* or treat*)).ab. or placebo*.ab,ti. or drug therapy.fs. or trial.ab,ti. or groups.ab. or (control* adj3 (trial* or study or studies)).ab,ti. or ((singl* or doubl* or tripl* or trebl*) adj3 (blind* or mask* or dummy*)).mp. or clinical trial, phase ii/ or clinical trial, phase iii/ or clinical trial, phase iv/ or randomised controlled trial/ or pragmatic clinical trial/ or (quasi adj (experimental or random*)).ti,ab. or ((waitlist* or wait* list* or treatment as usual or TAU) adj3 (control or group)).ab.)

4. (1 and 2 and 3)

Records are screened for reports of RCTs within the scope of the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group. Secondary reports of RCTs are tagged to the appropriate study record. Similar weekly search alerts are also conducted on OVID EMBASE and PsycINFO, using relevant subject headings (controlled vocabularies) and search syntax, appropriate to each resource.

Appendix 2. Additional search strategies (CENTRAL and PsycINFO):

CENTRAL search strategy:

Issue 8, 2013, n=124

#1. MeSH descriptor LUNG DISEASES, OBSTRUCTIVE, this term only #2. MeSH descriptor PULMONARY DISEASE, CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE explode all trees #3. emphysema* #4. chronic* near/3 bronchiti* #5. (obstruct*) near/3 (pulmonary or lung* or airway* or airflow* or bronch* or respirat*) #6. (COPD or COAD or COBD or AECB) #7. (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6) #8. MeSH descriptor ANXIETY, this term only #9. MeSH descriptor ANXIETY DISORDERS explode all trees #10. MeSH descriptor ANXIETY, SEPARATION, this term only #11. MeSH descriptor PANIC, this term only #12. MeSH descriptor OBSESSIVE BEHAVIOR explode all trees #13. MeSH descriptor COMPULSIVE BEHAVIOR explode all trees #14. MeSH descriptor STRESS, PSYCHOLOGICAL explode all trees #15. MeSH descriptor NEUROTIC DISORDERS, this term only #16. (anxiety or phobi* or agoraphobi* or claustrophobi* or PTSD or post‐trauma* or posttrauma or (post NEXT trauma*) or (combat NEXT disorder) or panic or OCD or obsess* or compulsi* or GAD or stress* or distress* or neurosis or neuroses or neurotic or psychoneuro*) #17. (#8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16) #18. (#7 and #17) #19. (SR‐DEPRESSN OR HS‐DEPRESSN) #20. (SR‐AIRWAYS OR HS‐AIRWAYS) #21. #19 OR #20 #22. (#18 NOT #21)

OVID PsycINFO search strategy:

Searched 26 September 2013, n=98

Lung Disorders/

exp Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease/

(chronic* adj3 bronchiti*).mp.

emphysema*.mp.

(obstruct* adj3 (pulmonary or lung* or airway* or airflow* or bronch* or respirat*)).mp.

(COPD or COAD or COBD or AECB).mp.

or/1‐6

exp Anxiety/

exp Anxiety Disorders/

exp Phobias/

exp Neurosis/

exp Stress/

exp Trauma/

Panic Attack/ or Panic/ or Panic Disorder/

exp Fear/

(anxiety or phobi* or agoraphobi* or claustrophobi* or PTSD or post‐trauma* or posttrauma or post trauma* or combat disorder or panic or OCD or obsess* or compulsi* or GAD or stress* or distress* or neurosis or neuroses or neurotic or psychoneuro*).mp.

or/8‐16

treatment effectiveness evaluation.sh.

clinical trials.sh.

mental health program evaluation.sh.

placebo.sh.

placebo*.ti,ab.

randomly.ab.

randomi#ed.ti,ab.

trial*.ti,ab.

((singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl*) adj3 (blind* or mask* or dummy)).mp.

(control* adj3 (trial* or study or studies or group*)).ti,ab.

"2000".md.

factorial*.ti,ab.

allocat*.ti,ab.

assign*.ti,ab.

volunteer*.ti,ab.

(crossover$ or cross over*).ti,ab.

(quasi adj (experimental or random*)).mp.

(((waitlist* or (wait* and list*)) and (control* or group)) or treatment as usual or TAU).ab.

or/18‐35

(7 and 17 and 36)

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Psychological therapies versus co‐intervention.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|