Abstract

Background

Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) is recognized as a frequent cause of antibiotic‐associated diarrhoea and colitis. This review is an update of a previously published Cochrane review.

Objectives

The aim of this review is to investigate the efficacy and safety of antibiotic therapy for C. difficile‐associated diarrhoea (CDAD), or C. difficile infection (CDI), being synonymous terms.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, CENTRAL and the Cochrane IBD Group Specialized Trials Register from inception to 26 January 2017. We also searched clinicaltrials.gov and clinicaltrialsregister.eu for ongoing trials.

Selection criteria

Only randomised controlled trials assessing antibiotic treatment for CDI were included in the review.

Data collection and analysis

Three authors independently assessed abstracts and full text articles for inclusion and extracted data. The risk of bias was independently rated by two authors. For dichotomous outcomes, we calculated the risk ratio (RR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI). We pooled data using a fixed‐effect model, except where significant heterogeneity was detected, at which time a random‐effects model was used. The following outcomes were sought: sustained symptomatic cure (defined as initial symptomatic response and no recurrence of CDI), sustained bacteriologic cure, adverse reactions to the intervention, death and cost.

Main results

Twenty‐two studies (3215 participants) were included. The majority of studies enrolled patients with mild to moderate CDI who could tolerate oral antibiotics. Sixteen of the included studies excluded patients with severe CDI and few patients with severe CDI were included in the other six studies. Twelve different antibiotics were investigated: vancomycin, metronidazole, fusidic acid, nitazoxanide, teicoplanin, rifampin, rifaximin, bacitracin, cadazolid, LFF517, surotomycin and fidaxomicin. Most of the studies were active comparator studies comparing vancomycin with other antibiotics. One small study compared vancomycin to placebo. There were no other studies that compared antibiotic treatment to a placebo or a 'no treatment' control group. The risk of bias was rated as high for 17 of 22 included studies. Vancomycin was found to be more effective than metronidazole for achieving symptomatic cure. Seventy‐two per cent (318/444) of metronidazole patients achieved symptomatic cure compared to 79% (339/428) of vancomycin patients (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.84 to 0.97; moderate quality evidence). Fidaxomicin was found to be more effective than vancomycin for achieving symptomatic cure. Seventy‐one per cent (407/572) of fidaxomicin patients achieved symptomatic cure compared to 61% (361/592) of vancomycin patients (RR 1.17, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.31; moderate quality evidence). Teicoplanin may be more effective than vancomycin for achieving a symptomatic cure. Eightly‐seven per cent (48/55) of teicoplanin patients achieved symptomatic cure compared to 73% (40/55) of vancomycin patients (RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.46; very low quality evidence). For other comparisons including the one placebo‐controlled study the quality of evidence was low or very low due to imprecision and in many cases high risk of bias because of attrition and lack of blinding. One hundred and forty deaths were reported in the studies, all of which were attributed by study authors to the co‐morbidities of the participants that lead to acquiring CDI. Although many other adverse events were reported during therapy, these were attributed to the participants' co‐morbidities. The only adverse events directly attributed to study medication were rare nausea and transient elevation of liver enzymes. Recent cost data (July 2016) for a 10 day course of treatment shows that metronidazole 500 mg is the least expensive antibiotic with a cost of USD 13 (Health Warehouse). Vancomycin 125 mg costs USD 1779 (Walgreens for 56 tablets) compared to fidaxomicin 200 mg at USD 3453.83 or more (Optimer Pharmaceuticals) and teicoplanin at approximately USD 83.67 (GBP 71.40, British National Formulary).

Authors' conclusions

No firm conclusions can be drawn regarding the efficacy of antibiotic treatment in severe CDI as most studies excluded patients with severe disease. The lack of any 'no treatment' control studies does not allow for any conclusions regarding the need for antibiotic treatment in patients with mild CDI beyond withdrawal of the initiating antibiotic. Nonetheless, moderate quality evidence suggests that vancomycin is superior to metronidazole and fidaxomicin is superior to vancomycin. The differences in effectiveness between these antibiotics were not too large and the advantage of metronidazole is its far lower cost compared to the other two antibiotics. The quality of evidence for teicoplanin is very low. Adequately powered studies are needed to determine if teicoplanin performs as well as the other antibiotics. A trial comparing the two cheapest antibiotics, metronidazole and teicoplanin, would be of interest.

Plain language summary

Antibiotic therapy for Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhoea in adults

Background

Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) is a bacterium that can live harmlessly in the colon, but when an individual takes an antibiotic for another condition, the C. difficile can grow and replace most of the normal bacterial flora that live in the colon. This overgrowth causes C. difficile‐associated diarrhoea (also known as C. difficile infection ‐ CDI). The symptoms of CDI include diarrhoea, fever and pain. CDI may be only mild but in many cases is very serious and, if untreated, can be fatal. There are many proposed treatments for CDI, but the most common are withdrawing the antibiotic that caused the CDI and prescribing an antibiotic that kills the bacterium. Many antibiotics have been tested in clinical trials for effectiveness and this review studies the comparisons of these antibiotics. This review is an update of a previously published Cochrane review.

Methods

We searched the medical literature up to 26 January 2017. All randomised trials that compare two different antibiotics, or variations in dosing of a single antibiotic for treatment of CDI were included. Trials comparing antibiotic to placebo (e.g. a sugar pill) or no treatment were sought but, save for one poor quality placebo‐controlled trial, none were found. Trials that compared antibiotics to a non‐antibiotic treatment were not included.

Results

Twenty‐two studies (total 3215 participants) were included. The majority of studies enrolled participants with mild to moderate CDI who could tolerate oral antibiotics. Sixteen of the included studies excluded participants with severe CDI and few participants with severe CDI were included in the other studies. Twelve different antibiotics were assessed. Most of the studies compared vancomycin or metronidazole with other antibiotics. One small study compared vancomycin to placebo (e.g. sugar pill). There were no other studies that compared antibiotic treatment to a placebo or a no treatment control group. Seventeen of the 22 included studies had quality issues. In four studies, vancomycin was found to be superior to metronidazole for achieving sustained symptomatic cure (defined as resolution of diarrhoea and no recurrence of CDI). We rated the quality of the evidence supporting this finding as moderate. A new antibiotic, fidaxomicin, was, in two large studies, found to be superior to vancomycin. The quality of the evidence supporting this finding was moderate. It should be noted that the differences in effectiveness between these antibiotics were not too great and that metronidazole is far less expensive than either vancomycin and fidaxomicin. A pooled analysis of two small studies suggests that teicoplanin may be more effective than vancomycin for achieving symptomatic cure. The quality of the evidence supporting this finding was very low. The quality of the evidence for the other seven antibiotics in this review was very poor because the studies were very small, and many patients dropped out of these studies before completion. One hundred and forty deaths were reported in the studies, all of which were attributed to participants preexisting health problems. The only side effects attributed to antibiotics were rare nausea and temporary elevation of liver enzymes. Recent cost data (July 2016) for a 10 day course of treatment shows that metronidazole 500 mg is the least expensive antibiotic with a cost of USD 13. Vancomycin 125 mg costs USD 1779 compared to fidaxomicin 200 mg at USD 3453.83 or more and teicoplanin at approximately USD 83.67.

Conclusion

No firm conclusions can be drawn regarding the effectiveness of antibiotic treatment in severe CDI as most studies excluded these patients. The lack of any 'no treatment' control studies does not allow for any conclusions regarding the need for antibiotic treatment in patients with mild CDI beyond withdrawal of the antibiotic that caused CDI. Nonetheless, moderate quality evidence suggests that vancomycin is superior to metronidazole and fidaxomicin is superior to vancomycin. The differences in effectiveness between these antibiotics were not too large and the advantage of metronidazole is its far lower cost compared to the other antibiotics. The quality of evidence for teicoplanin is very low. Larger studies are needed to determine if teicoplanin performs as well as the other antibiotics. A trial comparing the two cheapest antibiotics, metronidazole and teicoplanin would be of interest.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Metronidazole versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhoea in adults.

| Metronidazole versus Vancomycin for Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhoea in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhoea in adults Settings: Intervention: Metronidazole versus Vancomycin | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Metronidazole versus Vancomycin | |||||

| Symptomatic cure with all exclusions treated as failures Follow‐up: mean 4 weeks | 792 per 10001 | 713 per 1000 (665 to 768) | RR 0.9 (0.84 to 0.97) | 872 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | |

| Bacteriologic cure Follow‐up: mean 4 weeks | 529 per 10001 | 449 per 1000 (328 to 619) | RR 0.85 (0.62 to 1.17) | 163 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3 | |

| Cure (combined symptomatic and bacteriologic cure) ‐ mild disease Follow‐up: mean 4 weeks | 841 per 10001 | 740 per 1000 (597 to 917) | RR 0.88 (0.71 to 1.09) | 90 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,4,5 | |

| Cure (combined symptomatic and bacteriologic cure) ‐ severe disease | 711 per 10001 | 526 per 1000 (369 to 739) | RR 0.74 (0.52 to 1.04) | 82 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,4,5 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Control group risk comes from control arm of meta‐analysis, based on included trials. 2 High risk of bias. 3 Serious imprecision. 4 Unclear risk of bias. 5 Unclear if stratification by severity was post hoc.

Summary of findings 2. Teicoplanin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhoea in adults.

| Teicoplanin versus Vancomycin for Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhoea in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhoea in adults Settings: Intervention: Teicoplanin versus Vancomycin | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Teicoplanin versus Vancomycin | |||||

| Symptomatic Cure Follow‐up: mean 4 weeks | 727 per 10001 | 880 per 1000 (727 to 1000) | RR 1.21 (1 to 1.46) | 110 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3 | |

| Bacteriologic Cure Follow‐up: mean 4 weeks | 452 per 10001 | 822 per 1000 (537 to 1000) | RR 1.82 (1.19 to 2.78) | 59 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,4 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Control group risk comes from control arm of meta‐analysis, based on included trials. 2 High risk of bias. Blinding not done in either study and other pathogens not excluded in Wenisch 3 Serious imprecision. Two very small studies 4 Serious imprecision. Just a single small study

Summary of findings 3. Fidaxomicin compared to vancomycin for Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhoea in adults.

| Fidaxomicin compared to Vancomycin for Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhoea in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhoea in adults Settings: Intervention: Fidaxomicin Comparison: Vancomycin | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Vancomycin | Fidaxomicin | |||||

| Symptomatic Cure Follow‐up: mean 4 weeks | 610 per 10001 | 713 per 1000 (652 to 774) | RR 1.17 (1.07 to 1.27) | 1164 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Control group risk comes from control arm of meta‐analysis, based on included trials. 2 High risk of bias in both studies.

Summary of findings 4. Bacitracin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhoea in adults.

| Bacitracin versus Vancomycin for Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhoea in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhoea in adults Settings: Intervention: Bacitracin versus Vancomycin | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Bacitracin versus Vancomycin | |||||

| Symptomatic Cure Follow‐up: mean 4 weeks | 462 per 10001 | 268 per 1000 (157 to 457) | RR 0.58 (0.34 to 0.99) | 104 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Control group risk comes from control arm of meta‐analysis, based on included trials. 2 High risk of bias. Attrition and blinding issues in one trial. 2 Very serious imprecision. Two very small studies with few events.

Background

Description of the condition

The administration of antibiotics is known to be associated with the development of diarrhoea in patients. Erythromycin and the clavulanate in amoxicillin‐clavulanate cause diarrhoea by accelerating gastrointestinal motility (Bartlett 2002). Still other antibiotics are thought to cause diarrhoea by reducing the number of fecal anaerobes, thereby decreasing carbohydrate digestion and absorption, leading to an osmotic diarrhoea (Bartlett 2002). Nearly 15% of hospitalised patients receiving beta‐lactam antibiotics develop diarrhoea (McFarland 1995). Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) infection of the colon (CDI) is another cause of antibiotic‐associated diarrhoea that is thought to be caused by a presumed overgrowth of native or newly acquired C. difficile (Fekety 1993). C. difficile is implicated in 20 to 30% of patients with antibiotic‐associated diarrhoea, in 50 to 70% of those with antibiotic‐associated colitis and in more than 90% of those with antibiotic‐associated pseudomembranous colitis (Bartlett 1980; Bartlett 1990; George 1982; Kelly 1994). Approximately 5% of healthy adults asymptomatically carry low concentrations of C. difficile in their colon, and the growth of these bacteria has been shown in vitro to be held in check by normal gut flora (Fekety 1993). The exact mechanism by which C. difficile overgrowth occurs is still unclear, but it can occur with the administration of oral, parenteral or topical antibiotics (Fekety 1993:Thomas 2003).

It is important to explain the terms used in conjunction with C. difficile infection, as the studies analysed in this review involve various descriptions of C. difficile disease. Clostridium difficile‐associated diarrhoea (CDAD) occurs in a patient with diarrhoea that has tested positive for C. difficile toxin or a positive stool culture for C. difficile. C. difficile colitis involves a stool test positive for the organism and signs of mucosal inflammation seen on endoscopy. Pseudomembranous colitis refers to the actual presence of pseudomembranes seen on endoscopy. CDI is a term used in an increasing number of publications but by no means to the exclusion of CDAD. Both terms connote a patient with symptomatic diarrhoea and laboratory evidence of C. difficile as the cause of that diarrhoea. Pseudomembranous colitis is meant to connote the same disease but is not quite synonymous, as many patients with antibiotic‐associated diarrhoea do not undergo the endoscopy and biopsy necessary for the diagnosis of colitis or the endoscopy and visualization of pseudomembranes. This systematic review will use the term CDI for all forms of symptomatic C. difficile infection for its analyses. This review is an update of a previously published Cochrane review (Bricker 2005; Nelson 2007; Nelson 2011), and includes six new trials assessing three new antibiotics.

Description of the intervention

The standard treatment for primary infection caused by C. difficile is an antibiotic. This is usually done in conjunction with with the cessation of the antibiotic that caused the alteration of the gut flora in the first place (when feasible, considering the patient's clinical condition) with subsequent overgrowth of Clostridium difficile.

How the intervention might work

By treatment with an antibiotic that is specifically effective against Clostridium difficile, toxin production is reduced and repopulation of the gut with normal gut flora is possible.

Why it is important to do this review

During the early part of the 21st century, much higher mortality rates from CDI than previous reports were reported in Quebec (Pepin 2005). This was related to the appearance of a new variant of C. difficile, which is capable of secreting much higher amounts of toxin A and B and is more resistant to standard antibiotic therapy (Louie 2005). This new variant resulted in a higher incidence of CDI among hospitalised patients (McDonald 2005), a greater need for urgent colectomy for toxic colitis and a high mortality rate (e.g. 37%; Pepin 2005). This variant, ribotype 027, has spread from Quebec to the USA, and Europe (Louie 2005; Laurence 2006). In the United States hospitalizations for CDI doubled between 2000 and 2010 and was expected to continue to increase in 2011 and 2012. CDI is the leading cause of gastrointestinal‐related death in the USA. CDI is estimated to have caused 14,000 deaths in the USA in 2007 and is the most common healthcare‐associated infection. The estimated cost of CDI is USD 4,800 million per year for acute care facilities alone in the USA (Lessa 2015). Unlike the UK, where both incidence and mortality have declined in recent years (HPA 2016), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality has shown a consistent increase in CDI from the turn of the century through 2015 (AHRQ 2016; Steiner 2015).

The emergence of this highly virulent bacterium adds urgency to the identification of effective therapy.

Objectives

The aim of this review was to investigate the efficacy and safety of antibiotic therapy for CDI, to identify the most effective antibiotic treatment for CDAD in adults and to determine the need for stopping the causative antibiotic during therapy.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) assessing antibiotic treatment for CDI were considered for inclusion.

Types of participants

The types of participants included: (I) patients with diarrhoea: various definitions exist usually describing the consistency of stool, number of bowel movements per day, duration of symptoms, and rarely stool volume; (ii) patients with C. difficile in stool identified by stool culture positive for C. difficile and or by stool positive for C. difficile cytotoxin; (iii) patients who had received prior antibiotic therapy for an infection other than C. difficile; and (iv) patients 18 years of age of older.

Patients were excluded if they did not have diarrhoea or if there was no evidence of C. difficile infection.

Types of interventions

Only studies involving antibiotic therapy for C. difficile‐associated diarrhoea were included. These studies may include comparisons among different antibiotics, between different timing or doses of the same antibiotic, or between antibiotic therapy and placebo. Studies were excluded if they compared antibiotic to non‐antibiotic therapy (such as resins, vaccines, probiotics or biologicals) or if, in conjunction with antibiotic treatment, the intervention being tested was of a non‐antibiotic such as those listed above. In addition interventions used for the prevention of CDI are not included in this review.

Types of outcome measures

The following outcomes were sought:

Sustained symptomatic cure: An initial resolution of the diarrhoea and no evidence of recurrence of diarrhoea due to CDI.

Bacteriologic cure: Conversion from a stool positive for any CDI assay to negative and no recurrence of CDI.

No specific minimum time limit was set for either of these determinations of recurrence.

Death.

Drug‐related adverse events (DRAE) of the antibiotic treatments.

Cost of each of the major antibiotics.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE , CENTRAL and the Cochrane IBD Group Specialized Register from inception to 26 January 2017. The search strategies are reported in Appendix 1. Studies published only as abstracts were not explicitly excluded.

Searching other resources

In addition, trials were sought in the Clinicaltrials.gov and Clinicaltrialsregister.eu registers using the search term 'Clostridium difficile'.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

At least two authors (three in this update) examined all the citations and abstracts derived from the electronic search strategy and independently selected trials to be included. Full reports of potentially relevant trials were retrieved to assess eligibility. Reviewers were not blind to the names of trials' authors, institutions or journals. Any disagreements about trial inclusion were resolved by group discussion.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction was performed independently by at least two authors (three in this update). Results were compared between reviewers and all studies were presented for group discussion. Where data may have been collected but not reported, further information was sought from the individual trial authors. When dropouts occurred and were not included in the analyses, and the randomisation group was known, these dropouts were treated as treatment failures in this meta‐analysis.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the included studies using the Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011). Criteria for quality assessment includes:

(1) Selection bias: We rated random sequence generation as 'low risk' if the investigators described a random component in the sequence generation process. We rated as 'high risk' if the investigators described a non‐random component in the sequence generation process. We rated as 'unclear risk' if insufficient information about the sequence generation process was provided.

(2) Performance bias: We rated allocation sequence concealment as 'low risk' if participants and investigators enrolling participants could not foresee treatment assignment. We rated as 'high risk' if participants or investigators enrolling participants could possibly foresee assignments and thus introduce selection bias. We rated as 'unclear risk' if the method of concealment was not described or not described in sufficient detail to allow a definite judgement.

(3) Detection bias: We rated blinding of participants and personnel as 'low risk' if blinding of participants and personnel was ensured, and it was unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. We rated as 'high risk' if there was no blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome was likely to be influenced by a lack of blinding or blinding of participants was attempted, but it was likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome was likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. We rated as 'unclear risk' if insufficient information was provided to allow a definite judgement. We rated binding of outcome assessment as 'low risk' if blinding of outcome assessors was ensured, and it was unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. However, due to the nature of the intervention, for several outcome items blinding of outcome assessors was not possible and may be a potential source of bias. We rated as 'high risk' if if there was no blinding of outcome assessors, and the outcome was likely to be influenced by a lack of blinding or blinding of outcome assessors was attempted, but it was likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome was likely to be influenced by a lack of blinding. We rated as 'unclear risk' if insufficient information was provided to allow a definite judgement.

(4) Attrition bias: We rated incomplete outcome data as 'low risk' if there were no missing outcome data, or if there were fewer than 10% post‐randomisation dropouts or withdrawals. We rated as 'high risk' if the reason for missing outcome data was likely to be related to the true outcome. We rated as 'unclear risk' if there was insufficient reporting of attrition and exclusions to permit judgement.

We rated selective reporting as 'low risk' if the study protocol was available and all of the pre‐specified primary and secondary outcomes that were of interest to the review were reported in the pre‐specified manor or the study protocol was not available but it was clear that the published reports included all expected outcomes, including those that were pre‐specified. We rated as 'high risk' if the pre‐specified primary outcomes were not all reported, or one or more outcomes of interest for the review were reported incompletely so that the data could not be used for meta‐analysis, or the study report failed to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study. We rated as 'unclear risk' if insufficient information was provided to allow a definite judgement.

(5) Selective Reporting

Selective reporting was focused in this review on whether recurrence data were collected and presented for each study. This is a necessary element in the determination of sustained clinical response.

(6) Other bias We rated other bias as 'low risk' if the study appears to be free of other sources of bias. We rated as 'high risk' if there was at least one other important risk of bias. We rated as 'unclear risk' if there may have been a risk of bias, but there was either insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists or insufficient rationale or evidence that an identified problem introduced bias.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes, we calculated the risk ratio (RR) with corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI).

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the individual patient.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted study authors for missing data. Dropouts were considered to be treatment failures for the analyses.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Clinical heterogeneity was assessed by examining the patient population, interventions and outcome definition and assessment. Methodological heterogeneity was assessed by looking at the components of the risk of bias assessment. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed by calculating the Chi2 and I2 statistics. We considered heterogeneity to be significant if the the P value for Chi2 was < 0.10 or I2 was > 60%.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed selective reporting as described above. If any of the pooled analyses included 10 or more studies, we planned to assess potential publication bias by constructing a funnel plot.

Data synthesis

Data were entered and analysed in Revman 5.3. For dichotomous outcomes we calculated the pooled RR and corresponding 95% CI. Due to the small number of studies in each analysis and the lack of statistical heterogeneity in those few analyses with more than one study, a fixed‐effect model was used for comparisons with more than one included study. When considerable clinical heterogeneity was encountered between comparisons, as in Analysis 1.1, both fixed‐effect and random‐effects models were calculated.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Metronidazole vs Vancomycin, Outcome 1 Sustained Symptomatic Cure with all exclusions treated as failures.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

For this systematic review, we assessed specific antibiotics individually. No further subgroup analyses were planned.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned for sensitivity analyses based on study quality. Howveer, given the poor overall quality of the studies in this systematic review no sensitivity analyses are reported in this update.

Summary of Findings

All included studies are RCTs. We used the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach to assess the overall quality of the evidence supporting the primary outcome and selected secondary outcomes (Schünemann 2011). The overall quality of evidence can be graded into four levels:

1. High: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect;

2. Moderate: Further research is likely to have an impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate;

3. Low: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence on the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate; or

4. Very low: Any estimate of effect is very uncertain.

The overall quality of evidence can be downgraded by one (serious concern) or two levels (very serious concern) for the following reasons: risk of bias, inconsistency (e.g. unexplained heterogeneity, inconsistency of results), indirectness (e.g. indirect population, intervention, control, outcomes), publication bias, and imprecision (e.g. wide confidence intervals, single trial). Imprecision was determined principally by a small number of studies for a comparison (two or fewer studies) and fewer than 100 events for that comparison. We used the GRADEproGDT software to produce the Summary of Findings Tables.

Cost

Cost estimates were determined by obtaining information from American retail pharmacies (i.e. GoodRx which is a compendium of six pharmacies and Walgreens/Boots) for a 10 day course of therapy, except for Teicoplann which as obtained from the British National Formulary.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

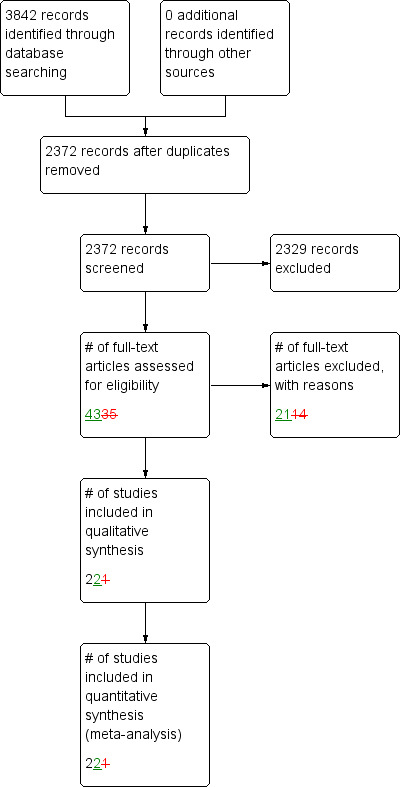

A literature search conducted on 26 January 2017 identified 3842 studies. After duplicates were removed a total of 2372 studies remained for review of titles and abstracts. Two authors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of these studies and 43 studies were selected for full text review (See Figure 1). Twenty‐one studies were subsequently excluded for reasons cited in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. In addition, two phase III trials of a new drug, cadazolid, were identified by searching trial registries (NCT01983683; NCT01987895).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

In the original review there were nine included studies. The first update included three additional studies (Lagrotteria 2006; Musher 2006; Wullt 2004). The second update included three additional studies (Louie 2009; Musher 2009; Zar 2007). In this third update seven more studies were added (Cornley 2012; Garey 2011; Johnson 2014; Lee 2016a; Louie 2011; Louie 2015; Mullane 2015).

The 22 included studies (total 3215 participants) involve patients with diarrhoea who have recently received antibiotics for an infection other than C. difficile. The definition of diarrhoea ranged from at least two loose stools per day with an associated symptom such as rectal temperature > 38 ºC (Anonymous 1994), to at least six loose stools in 36 hours (Teasley 1983; Louie 2009). All of the studies included a 'loose' or 'liquid' description of the stool in their definitions of diarrhoea. In terms of exclusion criteria, patients with HIV were only explicitly excluded from one study (Anonymous 1994). Pregnant women were excluded from two studies (Anonymous 1994; Zar 2007). All other studies had varying and vague exclusion criteria ranging from "other obvious cause of diarrhoea" (Teasley 1983) to "anatomic abnormality" (Young 1985). Both Louie 2009 and Musher 2009 excluded patients deemed clinically unstable and ''not expected to survive the study period''. Zar 2007 and most other authors excluded patients with suspected or proven life‐threatening intra‐abdominal complications. Johnson 2014 accepted a positive endoscopy at enrolment as long as a positive toxin assay followed. Mullane 2015 excluded patients if they had 12 or more stools per day. Among the seven new studies only two specifically excluded patients with Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis (Lee 2016a; Louie 2011). In fact patients in all 22 included studies were well enough to tolerate oral medication. None of the prescribed antibiotics were given intravenously.

The studies used different methods for detecting CDI. Teasley 1983 defined C. difficile disease as stool being positive for C. difficile by culture or cytotoxin assay, or by the presence of pseudomembranes on endoscopy. Stool was tested for other enteric pathogens, but the authors did not comment on the presence or absence of these pathogens. Young 1985 and Zar 2007 defined CDI in the same manner as Teasley 1983. Young 1985 tested for the presence of other enteric pathogens and excluded patients if their stool tested positive for any other pathogen. Dudley 1986 and Fekety 1989 and Louie 2009 defined C. difficile disease by both culture or cytotoxin assay. Dudley 1986 and Fekety 1989 did not test for the presence of other enteric pathogens. De Lalla 1992 defined C. difficile disease as stool being positive for cytotoxin, culture and evidence of colitis on endoscopy. De Lalla 1992 excluded patients if their stool tested positive for any other pathogen. Wenisch 1996 defined C. difficile disease as stool positive for cytotoxin or endoscopic evidence of colitis and fecal leukocytes. Wenisch 1996 did not perform stool culture on any of the study patients. The Swedish CDI study defined C. difficile disease as being positive for cytotoxin or culture or both and excluded patients if their stool tested positive for any other pathogen (Anonymous 1994). Eight studies used toxin assay and symptomatic diarrhoea to define C. difficile disease (Cornley 2012; Garey 2011; Johnson 2014; Lagrotteria 2006; Louie 2011; Musher 2006; Musher 2009; Wullt 2004). Endoscopic evidence of pseudomembranous colitis was used in Louie 2011, Cornley 2012 and Johnson 2014 for initial enrolment, but subsequent positive toxin assay was also required.

Eighteen of the 22 included studies compared different antibiotics for the treatment of C. difficile‐associated diarrhoea. Teasley 1983 compared oral vancomycin 500 mg four times a day for 10 days with oral metronidazole 250 mg four times a day for 10 days. Young 1985 compared oral vancomycin 125 mg four times a day for 7 days with oral bacitracin 20,000 units four times a day for 7 days. Dudley 1986 compared oral vancomycin 500 mg four times a day for 10 days with oral bacitracin 25,000 units four times a day for 10 days. De Lalla 1992 compared oral vancomycin 500 mg four times a day for 10 days with oral teicoplanin 100 mg two times a day for 10 days. Wenisch 1996 compared four antibiotics: oral vancomycin 500 mg three times a day for 10 days with oral metronidazole 500 mg three times a day for 10 days with oral fusidic acid 500 mg three times a day for 10 days with oral teicoplanin 400 mg two times a day for 10 days. Wullt 2004 compared 250 mg of fusidic acid three times per day to 400 mg of metronidazole three times per day for 7 days each. Musher 2006 compared 250 mg of metronidazole four times per day for 10 days to 500 mg of nitazoxanide twice a day given for either 7 or 10 days. Musher 2009 compared 125mg of vancomycin four times per day for 10 days to 500 mg of nitazoxanide twice a day for 10 days. Zar 2007 compared 125 mg of vancomycin four times per day with 250 mg of metronidazole four times per day for 10 days. Cornley 2012 and Louie 2011 published studies of identical design in two large diverse populations comparing an oral 10 day course of fidaxomicin 200 mg every 12 hours to vancomycin 125 mg every 6 hours. Johnson 2014 was a three armed study, whose principal objective was to assess the efficacy of Tolevamer, a resin that binds Clostridium difficile toxin. The other two arms of this multi‐institutional, multinational study compared the efficacy of vancomycin and metronidazole to Tolevamer and thus also to each other. Due to its size, this study added significantly to the data for the comparison of metronidazole to vancomycin. The Tolevamer arm of this study was not included in this review. Two other new antibiotics were reported by Louie 2015 (Cadazolid) and Mullane 2015 (LFF571). Neither of these recent studies stratified by disease severity before or after randomisation. The Cadazolid study reported three different dose groups separately but since the results were similar for the outcome assessment these groups were combined for the comparison to vancomycin. Lee 2016a compared two doses of a new antibiotic, surotomycin, to vancomycin in a non‐inferiority trial, similar to Cornley 2012 and Louie 2011).

Garey 2011 studied the effect of rifaximin 400 mg three times daily for 20 days compared to placebo in a group who had had CDI successfully treated with either metronidazole or vancomycin (the choice of these antibiotics being physician choice and non‐random) in order to prevent a highly likely occurrence, relapse of CDI. Strictly speaking this is not an eligible trial, in that it assesses a prophylactic intervention. However its goal was to define an antibiotic combination the best achieves a long term cure of CDI , perhaps more comparable in that regard to Johnson 1992.

The Swedish CDI study was a dose finding study which compared oral teicoplanin given at a constant daily dose but in differing dose schedules throughout the day (Anonymous 1994, also cited in some sources as Wistrom 1994). Fekety 1989 performed a dosage‐finding study for oral vancomycin by comparing 125 mg four times a day with 500 mg four times a day for an average of 10 days. Louie 2009 compared fidaxomicin (OPT‐80) given at either 50 mg, 100 mg or 200 mg doses twice daily for ten days. Only one study was placebo‐controlled and compared vancomycin to placebo (Keighley 1978).

In addition to treating CDI with antibiotics, the above studies also dealt with the initial, offending antibiotic in different ways. Only three studies explicitly reported that all initial antibiotics were stopped (Wenisch 1996; Young 1985; Zar 2007). Three of the other studies made attempts to stop the initial antibiotics, but these antibiotics were continued if deemed essential to the patient's clinical treatment (Anonymous 1994; Dudley 1986; Teasley 1983). Louie 2009 excluded any patients requiring concurrent antibiotic therapy, but made no reference to the initial antibiotics used in the included participants. The remaining studies either stated that the initial antibiotic was either stopped or changed (Fekety 1989) or did not make any reference to the initial antibiotic at all (Cornley 2012; De Lalla 1992; Garey 2011; Johnson 2014; Lagrotteria 2006; Louie 2011; Musher 2006; Musher 2009; Wullt 2004; Louie 2011).

Zar 2007 defined cure as a combination of resolution of diarrhoea and conversion of stool to toxin negative, whereas other authors reported these outcomes separately, or did not report bacteriologic cure at all. Zar 2007 is the first study to stratify patients (perhaps after randomisation) by disease severity when assessing the relative efficacy of metronidazole and vancomycin. This is of importance because this general concept of efficacy assessment has been adopted in subsequent studies (Cornley 2012; Johnson 2014; Louie 2011; Musher 2009), and three major guideline publications including the UK Health Protection Agency (HPA 2008), the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) (Bauer 2009), and the combined Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA), which is reported on the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) website (Cohen 2010). No study since Zar 2007 has specified in its methods that patients' randomisation was stratified by disease severity, although four more studies reported response to treatment by severity classes in post hoc subgroup analyses (Cornley 2012; Johnson 2014; Louie 2011; Musher 2009). None of the included studies stratified the randomisation of patients based on cessation or continuation of the antibiotic that caused the CDI.

Excluded studies

Excluded studies and the reasons for exclusion can be found in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

The results of the risk of bias analysis are presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Quality concerns include unclear allocation concealment, unclear generation of the allocation sequence and blinding of researchers and participants. Only 11 of the 22 studies reported adequate allocation concealment (Cornley 2012; Dudley 1986; Garey 2011; Keighley 1978; Lagrotteria 2006; Lee 2016a; Louie 2011; Musher 2009; Wullt 2004; Zar 2007). Twelve studies adequately explained the method used for random sequence generation (Cornley 2012; Dudley 1986; Fekety 1989; Garey 2011; Lagrotteria 2006; Louie 2009; Louie 2011; Louie 2015; Mullane 2015; Wenisch 1996; Wullt 2004; Zar 2007). Eleven studies clearly stated that the researchers and the subjects were both blinded (Cornley 2012; Garey 2011; Johnson 2014; Lee 2016a; Louie 2011; Louie 2015; Mullane 2015; Musher 2006; Musher 2009; Wullt 2004; Zar 2007). Two studies stated that patients were blinded, but it was unclear if outcome assessors were blinded (Dudley 1986; Young 1985). Outcome assessors were not blinded in the Fekety 1989 study. Patients were not blinded in the Lagrotteria 2006 study. Louie 2009 was a dose finding study and was not blinded. The Wenisch 1996, De Lalla 1992 and Boero 1990 studies were not blinded. Attempts were made to contact the authors to clarify these issues and as of the submission of this review correspondence was not established.

2.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

The included studies have additional quality issues. One diagnostic concern is that 17 of the 22 included studies used C. difficile cytotoxin stool assay as the means of identifying infected patients. Two other studies required stool positive for cytotoxin and growth of C. difficile on culture to establish the presence of CDI (De Lalla 1992; Fekety 1989). Although it was not specifically reported in the text how C. difficile was identified as the cause of CDI in the Lee 2016a study, the strain of C. difficile in each patients was reported in the demographics. Keighley 1978 separated patients who had positive cytotoxin from those patients who had positive cultures. However, the most important quality issue encountered in this review was that no study in which there were dropouts included those dropouts in their analyses, so effectively all participants were analysed as treated. In some studies this had a major impact, since randomisation occurred before disease confirmation, and participants were eliminated after randomisation when they were found not to have CDI. In some cases this was as low as 2% of those randomised (Musher 2009), however, in several studies the dropout rate was as high as 50% due to exclusions after randomisation (Anonymous 1994; Dudley 1986; Keighley 1978). For all studies in this review dropouts were considered to be treatment failures.

For the initial diagnosis of CDI, most included studies did not exclude the presence of other pathogens in the stool as the cause of diarrhoea. It is possible that a patient could have been infected with both C. difficile and another enteric pathogen. The studies do not consistently state whether the initial, offending antibiotic was stopped and if it was stopped, whether a different antibiotic was started in its place. Although Zar 2007 screened stool samples for Shigella, Salmonella and Campylobacter, all patients were negative for these microbes in this study. Additionally, only Young 1985 controlled for patients whose diarrhoea rapidly resolved on its own with the removal of the initial antibiotic by including only those patients with persistent symptoms. For these patients the diarrhoea may not have been caused by C. difficile, although it was present in the stool, or the bacterium was successfully purged by the patient. Recent studies relied on positive toxin assay and diarrhoea alone to make the diagnosis. Some studies included endoscopic confirmation of pseudomembranes, although this was not uniformly done even within these studies. Zar 2007 did include pre‐existing pseudomembrane checks, although no patients had pre‐existing pseudomembranous colitis in this study.

Each specific trial also had its own unique quality issues as well. In the Teasley 1983 study which compared vancomycin to metronidazole, the offending antibiotics believed to have brought about the CDI were said to be discontinued unless they were "essential for treatment." This was also true and quantified by Cornley 2012, Louie 2011 and Johnson 2014 but not allocated to such treatment in a random manner. Teasley 1983 did not indicate how many patients did not have their offending antibiotic discontinued. However these studies and others may confound the interpretation of results as the original antibiotic may have caused diarrhoea by a different mechanism. Dudley 1986 and Zar 2007 and Johnson 2014 (although positive endoscopy at recruitment was required for inclusion) did not have test results for C. difficile in the stool until after randomisation. As a result, all of the patients with diarrhoea that were C. difficile negative were dropped from these studies. Wenisch 1996 had a total of seven dropouts from all of the treatment arms combined. However, Wenisch 1996 did not indicate the treatment allocation of these patients, therefore precluding an accurate intention‐to‐treat analysis of the results. In the Swedish CDI study there was an intermediate measure of cure called 'improvement,' but the criteria for improvement were never described (Anonymous 1994). For the purposes of this systematic review, a conservative approach was taken and the 'improved' patients were not considered to have their clinical symptoms resolved. Fekety 1989 had a dropout rate of 18% and the duration of the antibiotic therapy was determined by each individual physician treating patients. The average duration of therapy was 10 days with a range of 5 to 15 days (Fekety 1989). Dropouts were 13% and 23% respectively in the Wullt 2004 and Musher 2006 studies, making an intention‐to‐treat analysis difficult. However, both studies reported dropouts by allocation group. There were no dropouts in the smaller Lagrotteria 2006 study. Zar 2007 had a dropout rate of 12.8% (22/172), however, the study still achieved predetermined power. Zar 2007 also excluded "suspected or proven life‐threatening intra‐abdominal complications" as well as prescription of either vancomycin or metronidazole in the 14 days prior to enrolment. Zar 2007 retested stool for recurrence at 21 days after cure (defined as symptom‐free and toxin‐free stool at day 10). This protocol was not based on evidence, and it should be noted that current guidelines for management of asymptomatic carriers of C. difficile are conservative. Although Zar 2007 screened for prior antibiotic use, no data were reported on which antibiotics were used. Although Musher 2009 was a multi‐centre randomised trial, 37 of 50 patients came from the principal investigator's hospital. The study excluded patients undergoing enteral tube feeding. Another exclusion criterion was use of "any drug with anti‐C. difficile activity ‐ with the exception of ≤3 oral doses of metronidazole or vancomycin ‐ within 1 week" of entry. It should be noted that Musher 2009 had a dropout rate of 18.4% (9/49) and was terminated early due to "slower‐than‐expected recruitment". It also fell far short of its predetermined sample size of 350.

Selective reporting bias was detected in only two studies (Boero 1990,Fekety 1989). None of the other studies reported very long follow up after innitial description of clinical response, varying from 14 (Musher 2009) to 40 (Wullt 2004) days.

Louie 2009 was a phase IIa trial and was an open label study for mild to moderate C. difficile infection and excluded all patients with severe disease and those who were "not expected to survive the study period". While patients kept a symptom diary, they were only formally observed at study entry and at the end of treatment or withdrawal.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Metronidazole versus vancomycin Symptomatic cure was improved with vancomycin over metronidazole with the addition of the large study by Johnson 2014. Seventy‐two per cent (318/444) of metronidazole patients achieved symptomatic cure compared to 79% (339/428) of vancomycin patients (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.84 to 0.97; Analysis 1.1; fixed‐effect; insignificant heterogeneity). A random‐effects model showed a non‐significant benefit for vancomycin (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.04). We rated the strength of the evidence supporting the symptomatic cure outcome as moderate due to high risk of bias and due to the non‐reporting of additional pathogens that may have caused diarrhoea. Only two studies reported on bacteriologic cure (Teasley 1983; Wenisch 1996), and the strength of evidence for this outcome was very low due to high risk of bias (i.e. lack of blinding) and very serious imprecision (Analysis 1.2). Looking at the severity stratification reported by Zar 2007 (Analysis 1.3), the evidence was also very low due to high risk of bias and very serious imprecision (See Table 1).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Metronidazole vs Vancomycin, Outcome 2 Bacteriologic Cure.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Metronidazole vs Vancomycin, Outcome 3 Sustained Cure (Combined symptomatic and bacteriologic cure).

One study presented an outcome not used in the other included studies (Zar 2007) which was a combination of symptomatic and bacteriologic cure (Zar 2007). Subsequent studies have only assessed bacteriologic evidence of CDI in patients with persistent or recurrent symptoms and therefore could not report bacteriologic cure (Cornley 2012; Johnson 2014; Louie 2011). Zar 2007 was also the first study to report differential efficacy of the two antibiotics based on disease severity.

Bacitracin versus vancomycin Vancomycin was also superior to bacitracin for achieving symptomatic cure. Twenty‐seven per cent (14/52) of bacitracin patients achieved symptomatic cure compared to 46% (24/52) vancomycin patients (RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.99; Analysis 2.1; no heterogeneity). We rated the strength of the evidence for this outcome as very low due to a high risk of bias (i.e. lack of blinding in one study) and serious imprecision (See Table 4).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Bacitracin vs Vancomycin, Outcome 1 Symptomatic Cure.

Teicoplanin versus vancomycin Sustained symptomatic cure was improved with teicoplanin compared to vancomycin, 87% (48/55) of patients who received teicoplanin achieved symptomatic cure compared to 73% (40/55) of patients who received vancomycin (RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.46; no heterogeneity; Analysis 3.1). Bacteriologic cure was reported by one small study. The quality of the evidence was very low in both cases due to a high risk of bias (i.e. lack of blinding) and serious imprecision due to small study sizes (See Table 3).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Teicoplanin vs Vancomycin, Outcome 1 Symptomatic Cure.

Fidaxomicin versus Vancomycin Fidaxomicin was more effective than vancomycin for achieving symptomatic cure in two large studies. Seventy‐one per cent (407/572) of fidaxomicin patients achieved symptomatic cure compared to 61% (361/592) of vancomycin patients (RR 1.17, 1.07 to 1.27, Analysis 5.1; no heterogeneity). The quality of the evidence was rated as moderate due to high risk of bias (Table 3)

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Fidaxomicin vs Vancomycin, Outcome 1 Symptomatic Cure.

Interventions for which there was only a single, usually very small, included study, or in some cases two studies, are reported below. All of these comparisons are subject to very serious imprecision due to the small number of participants and events within the study population and in some cases high risk of bias or inconsistency issues as well, so the quality of evidence for these comparisons was either low or very low.

Vancomycin versus placebo In a very small study (n = 44) vancomycin was found to be superior to placebo for symptomatic cure (RR 9.0, 95% 1.24 to 65.16) and for bacteriologic cure (RR 10.0, 95% CI 1.4 to 71.62). We rated the overall quality of the evidence supporting these outcomes as very low due to serious imprecision and high risk of bias (Keighley 1978).

Rifaximin versus Vancomycin In a very small study of 20 patients symptomatic cure was not found to be significantly different in those treated with Rifaximin compared to vancomycin (RR 0.9, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.18). We rated the quality of the evidence as very low due to high risk of bias and serious imprecision (Boero 1990).

Fusidic acid versus vancomycin No difference in symptomatic cure was found in a single small study comparing vancomycin to fusidic acid (Wenisch 1996). Seventy‐seven per cent (24/31) of patients who received vancomycin achieved symptomatic cure compared to 66% (19/29) of patients who received fusidic acid (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.17). There was also in no difference in bacteriologic cure (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.06). The quality of the evidence was rated as very low due to high risk of bias and serious imprecision). Wullt 2004 also studied this comparison in 131 patients but reported no recurrence data. Addition of Wullt 2004 to the analysis did not greatly change the results (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.08) or the GRADE rating.

Nitazoxanide versus vancomycin Symptomatic cure was achieved in one small study (n = 49) almost equally with vancomycin and nitazoxanide. Sixty‐seven per cent (18/27) of vancomycin patients were cured compared to 73% (16/22) of patients who received nitazoxanide (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.58). The quality of evidence was low due to serious imprecision (Musher 2009).

Metronidazole versus Nitazoxanide A single small study found little difference in the efficacy of metronidazole and nitazoxanide in achieving symptomatic cure (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.34). The quality of the evidence was very low due to high risk of bias (i.e. attrition) and serious imprecision (Musher 2006).

Metronidazole versus Metronidazole and Rifampin In a single small study (n = 39) there was little difference between metronidazole alone and metronidazole combined with rifampin in achieving symptomatic cure (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.49 to 2.41). The quality of the evidence was very low due to high risk of bias and serious imprecision (Lagrotteria 2006).

Metronidazole versus Teicoplanin In one small study (n = 59) teicoplanin was not significantly more effective than metronidazole in achieving symptomatic cure (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.09). The quality of the evidence was very low due to high risk of bias (i.e. lack of blinding and failure to exclude other pathogens) and serious imprecision (Wenisch 1996).

Metronidazole versus Fusidic Acid Metronidazole was no more effective than fusidic acid for achieving symptomatic cure in two small studies (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.30). Similar results were seen in these two small studies for bacteriologic cure (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.25; no heterogeneity). The quality of the evidence was very low due to high risk of bias (i.e. lack of blinding and attrition) and serious imprecision (Wenisch 1996; Wullt 2004).

Teicoplanin versus Fusidic Acid In one small study (n = 57) teicoplanin was more effective then fusidic acid for achieving symptomatic cure (RR 1.36, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.83), and bacteriologic cure (RR 1.73, 95% CI 1.19 to 2.51). The quality of evidence was very low due to high risk of bias (i.e. no blinding and failure to rule out other enteric pathogens) and serious imprecision (Wenisch 1996).

Dose Finding One small study (n = 56, Fekety 1989), found no difference in symptomatic cure between high and low dose regimens of vancomycin (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.38) in one small study. For fidaxomicin, also known as Opt‐80 (n = 48, Louie 2009), it appeared that the higher (200 mg) dose was more effective than low dose for symptomatic cure (RR 1.26, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.54). Both studies were very small and also had a high risk of bias (i.e. attrition, lack of blinding), and serious imprecision. The quality of the evidence was very low for both comparisons.

Dose Timing The dose of teicoplanin was maintained constant but administered in varying intervals in this small single study (n = 92). The dose was administered either twice or four times a day. There was no difference in symptomatic cure between doses administered twice or four times daily (RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.20). The study was terminated prematurely due to a higher than expected failure rate in the twice daily group. The quality of evidence in the study was very low due to high risk of bias (i.e. attrition) and serious imprecision (Anonymous 1994).

Rifaximin to diminish relapse risk After primary therapy of CDI with either metronidazole or vancomycin, rifaximin was found in one study to be insignificantly more effective than placebo for avoiding relapse (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.02). The quality of evidence was low due to high risk of bias and imprecision (Garey 2011).

Cadazolid versus Vancomycin In this small single study , three different doses of a new antibiotic, cadazolid, were compared to vancomycin in 82 patients. The results for all three doses were very similar and so we combined the dose groups as a single exposure to vancomycin, also with very similar effect (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.50 to 2.00). The quality of the evidence was moderate due to imprecision (Louie 2015).

LFF517 versus vancomycin This new antibiotic, as yet without a name, was compared to vancomycin in 76 randomised patients of whom 32 did not finish the study (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.57). The quality of the evidence was very low due to high risk of bias attrition and serious imprecision (Mullane 2015).

Surotomycin versus vancomycin One study (n = 209) compared two doses of surotomycin, a new antibiotic, to vancomycin (Lee 2016a). The results of the two doses were almost identical so these groups were combined in comparison to vancomycin. Surotomycin was marginally more effective than vancomycin for maintaining a sustained clinical cure (RR 1.22, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.56). The quality of evidence was moderate due to imprecision.

Older guidelines discuss treatment of unresponsive disease with an increased dose of vancomycin 500 mg four times daily, intravenous metronidazole 500 mg three times daily and rifampicin 300 mg twice daily. However, this regimen was shown to have no clinical benefit in primary CDI (Garey 2011; Lagrotteria 2006). The criteria defining severity stratification have differed across the studies included in this review (Bauer 2009; Cohen 2010; HPA 2016Musher 2009; Zar 2007). Lactate > 5 is perhaps the most valid marker of extreme disease severity, but it is associated with a 75% operative mortality. Therefore an earlier marker and proven therapy would be of more use (Cohen 2010). No randomised studies address this issue.

The patients with relapse of diarrhoea after treatment were re‐treated in various ways. Dudley 1986 re‐treated with the same antibiotic and Young 1985 re‐treated with the antibiotic from the other arm of the study. De Lalla 1992 stated that the patients with relapse were re‐treated, but analysed the results in aggregate, making it impossible to compare the antibiotics for efficacy. The Fekety 1989 vancomycin dose‐finding study re‐treated all nine relapses with vancomycin and subsequently cured these patients. Wenisch 1996 treated recurrent disease with teicoplanin with a reported a 100% cure rate. Louie 2009 re‐treated with either metronidazole or vancomycin, but did not report on the success of this treatment. The remaining studies did not report on the re‐treatment of relapses. As in the previous paragraph, the focus of randomised trials has been the prevention of recurrence and not its treatment. Johnson 2014 did enroll patients with recurrent disease as well as primary disease, but there is no mention in the paper that the recurrent patients were randomised separately so that the reporting of outcome of primary versus recurrent patients is once again a post hoc subgroup analysis (Assmann 2000).

Secondary outcome: Death The secondary outcome measured in this review, death, occurred infrequently in all of the studies. There were 140 deaths among the patients in the included studies. All of the reported deaths were described by the study authors as being due to the underlying morbidity that preceded CDI rather than the antibiotics used to treat CDI (Table 5). Although most of these patients had severe diseases prior to the diagnosis of CDI, it seems plausible that the CDI or antibiotic therapy could have contributed to their deaths. Dudley 1986 reported one death and one partial colectomy after failed treatment of CDI with bacitracin. Both patients were crossed‐over to vancomycin before their adverse outcome, with the first patient improving prior to his death, and the second patient continuing to have CDI. Fekety 1989 reported one death in each of the two vancomycin treatment arms. The Swedish CDI study reported one death in the two times per day teicoplanin group, but the authors did not specify if it was part of the CDI sub‐section of the study or part of the general dosage‐finding portion of the study (Anonymous 1994). Teasley 1983 had three deaths in the whole study, including two deaths in the vancomycin treatment arm. The authors attributed all three deaths to underlying illness and not to CDAD or the antibiotic therapy, a common claim in other studies as well. De Lalla 1992 reported two deaths and Musher 2009 reported one death. Both studies did not specify the treatment group and attributed the deaths to the patients' underlying disease. Zar 2007 reported eight deaths, four in each treatment group, but did not comment on the cause of mortality. Cornley 2012 and Louie 2011 reported 74 deaths in their two large studies, all felt to be due to the patient's primary disease and not associated with either antibiotic being investigated. Johnson 2014 reported 23 and 16 deaths in the metronidazole and vancomycin groups respectively again attributed to the patients' underlying comorbidity. There were two deaths in Louie 2015. Lee 2016a reported four deaths, two in each of the two treatment groups, all attributed to underlying disease.

1. Summary study.

| Study | n=Total | Deaths |

Harms due to Intervention |

Attrition% |

Stratified by Severity |

| Anonymous 1994 | 49 | 1 | joint pain | <10% | |

| Boero 1990 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Cornley 2012 | 535 | 20 Fid 17 Van |

none | 4.9% | Yes post randomisation |

| De Lalla 1992 | 51 | 2 | NR | 10% | |

| Dudley 1986 | 62 | 0 | NR | 52% | |

| Fekety 1989 | 46 | 0 | NR | 18% | |

| Garey 2011 | 79 | skin rash | 14% | ||

| Johnson 2014 | 1118 | 23 Met 16 Van |

none | 1.8% | Yes post randonisation |

| Lagrotteria 2006 | 39 | 2 | 0 | ||

| Lee 2016a | 209 | 4 | 5 | 7% | |

| Louie 2009 | 49 | 0 | 4% | ||

| Louie 2011 | 629 | 16 Fid 21 Van |

elevated liver enzymes |

5.2% | Yes post randomisation |

| Louie 2015 | 82 | 2 | 7.3% | ||

| Mullane 2015 | 72 | 0 | 44% | ||

| Musher 2006 | 142 | 4 | 23% | ||

| Musher 2009 | 50 | 0 | 2% | Yes post randomisation |

|

| Teasley 1983 | 101 | 2 | NR | 7% | |

| Wenisch 1996 | 126 | 3 | 5.5% | ||

| Wullt 2004 | 131 | 0 | 26% | ||

| Young 1985 | 42 | 0 | NR | 0 | |

| Zar 2007 | 172 | 7 | 13% | Yes but uncertain when |

|

| TOTAL | 140 |

NR: None reported

Drug‐related adverse events (DRAE) DRAEs were reported very differently in the included studies. It was reported that there were none (or not reported) in six studies (De Lalla 1992; Dudley 1986;Fekety 1989;Teasley 1983;Young 1985;Zar 2007). At the opposite end of the spectrum, quite remarkably high incidences of what was described as therapy emergent adverse events (TEAE) were reported by Cornley 2012 (75% with fidaxomicin and 71.5% for vancomycin, 26.5% and 22.3% described as serious), Louie 2011 (62.3%, 25% serious for fidaxomicin, 60.4%, 24.1% serious for vancomycin), and Johnson 2014 (35.3% vancomycin, 31.2% metronidazole). All three studies reported that around 1% of these TEAEs were due to study medications. All the other studies, attributed adverse events to the many serious co‐morbidities these patients had that gave rise to the CDI. Anecdotally reported DRAEs included pruritis, skin rash (Garey 2011), joint pain (Anonymous 1994), nausea (Zar 2007) and vomiting (Wenisch 1996), and elevation of liver enzymes (Louie 2011). Zar 2007 reported two adverse events that were clearly drug‐related, one patient in each treatment group had nausea and were switched to the other drug and completed therapy (as a crossover). None of the TEAEs are presented in a way that allows quantification of DRAE across studies in a summary of findings table. Most of the adverse events in Lee 2016a were indistinguishable from symptoms of CDI. Five patients ceased taking the medications due to unspecified adverse events (Lee 2016a).

Cost Two studies quantified the cost of treatment (Musher 2009; Wenisch 1996). Wenisch 1996 compared four different antibiotics. The cost data calculated at the time of the initial publication of this review for a course of treatment were: Metronidazole USD 35; Fusidic acid USD 287; Vancomycin USD 2030; and Teicoplanin USD 3430 (Bricker 2005). Musher 2009 compared two antibiotics. The cost data were as follows: Vancomycin USD 618 and Nitazoxanide USD 316 (Musher 2009).

More recent cost data (July 2016) for a 10 day course of treatment includes Metronidazole #20 500 mg USD 13 (Health Warehouse); Vancomycin 125 mg USD 1779 (Walgreens for 56 tablets); Fidaxomicin #20 200 mg: USD 3453.83 or more (Optimer Pharmaceuticals) and Teicoplanin approximately USD 83.67 (GBP 71.40, British National Formulary).

Discussion

Perhaps the biggest change for this update when compared to previous versions of this review is the change in outcome assessment. Recurrence rates have been reported to be high after initial resolution of CDI symptoms and assays, topping 20% (Vardakas 2012). There has been increasing emphasis on addressing the risk of recurrence of CDI as part of the primary therapy, with the desired outcome being a sustained symptomatic cure and bacteriologic cure (Cornley 2012; Garey 2011; Johnson 2012; Louie 2011). The previous set of outcomes for this systematic review have been condensed to: sustained symptomatic and bacteriologic cure, along with adverse events of the intervention and death. This should not just instruct how best to treat CDI patients but also provide the optimal protection for other hospitalised patients. In addition the number of outcomes assessed compared to previous versions is decreased by more than 50%, thus addressing the issue of multiplicity (Sedgwick 2014).

Summary of main results

The main results of this update have changed considerably since 2011. Moderate quality evidence suggests that vancomycin is more effective than metronidazole for achieving symptomatic cure, but the evidence is less supportive for bacteriologic cure (very low quality evidence; See Analysis 1.1, Analysis 1.2, Analysis 1.3, Table 1). Moderate quality evidence suggests that fidaxomicin is superior to vancomycin for achieving symptomatic cure with no direct data on bacteriologic cure (See Analysis 5.1, Table 3). Very low quality evidence from older smaller studies suggests that teicoplanin is a potentially effective drug compared to vancomycin or metronidazole (See Analysis 3.1, Table 2). Surotomycin was marginally superior to vancomycin (Analysis 6.1) based on a single study (n = 209). The use of the remaining antibiotics for treatment of CDI including bacitracin, fusidic acid, nitazoxanide, cadazolid, LFF571, rifaximin and rifampin was not supported by the evidence. The evidence supporting a specific therapy for bacteriologic cure is less conclusive, principally because the more recent and largest studies have not reported data that would allow assessment of bacteriologic cure (Cornley 2012; Johnson 2014; Louie 2011). Rifaximin given after a course of vancomycin of metronidazole may diminish the likelihood of recurrent CDI (Garey 2011).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The available evidence applies directly to the goals of this review: to assess the efficacy of antibiotic therapy for CDI. The results of this review are applicable to patients with mild CDI who can tolerate oral antibiotics. All of the included studies excluded patients with severe CDI.

Quality of the evidence

The only placebo‐controlled study of primary CDI was Keighley 1978. This is important since it could have provided evidence on how likely it is that CDI would spontaneously resolve. Keighley 1978 assessed the efficacy of oral vancomycin 125 mg taken four times a day for five days compared to placebo for the treatment of pseudomembranous colitis. All patients were recruited from a surgical ward and blinded during the five day treatment period. It is unclear from the study report whether the outcome assessor was blinded or not. Broad inclusion criteria were used. Any patient with postoperative diarrhoea was recruited. This led to the randomisation of patients with postoperative diarrhoea not related to C. difficile. The only exclusion criterion was a previous history of pseudomembranous colitis. The study not only divided patients by their treatment regimen, but also divided patients into three groups based on stool analysis results. Group one had stool that was culture positive for C. difficile and positive for C. difficile cytotoxin. Group two had stool that was culture positive for C. difficile only. Group three had stool that was culture negative and negative for cytotoxin. Keighley 1978 reported that only 21 of 44 randomised patients had some evidence of C. difficile infection. Of these patients 16 were toxin positive and 5 were culture positive. Twelve of these patients were in the vancomycin group and nine were in the placebo group. Keighley 1978 defined clinical response measured by stool frequency as resolution. Clinical response was higher in patients who received vancomycin in groups one and two, but response was not affected by treatment in group three. Keighley 1978 describes the numbers of patients taking vancomycin or placebo in whom stool converted to negative for C. difficile strain, negative for fecal cytotoxin and negative for histological evidence of pseudomembranous colitis. There are several major bias concerns with the Keighley 1978 study. The number of patients was small, and follow‐up was inadequate. During the convalescence period, there were specimens that were either not taken or mislaid. Two‐thirds of the patients in the vancomycin group fell into this category. Follow‐up conclusions were based on only four patients from the total of 12 patients with evidence of C. difficile infection that received vancomycin.

As mentioned above, Zar 2007 has had a great influence because of its stratification of outcome assessment by disease severity. Because of this, potential issues bear special attention. Despite the publication date, recruitment for this study ended in 2002, before the 027 strain of C. difficile reached the Chicago area, where the Zar 2007 study was conducted, and the severity of disease seen in this mutation had not yet been witnessed. Yet, in spite of excluding the sickest patients with CDI from the study, eight participants died within five days of the onset of therapy and were excluded from further analysis rather than being regarded as treatment failures. Randomisation also occurred before the diagnosis of C. difficile was established, and 14 randomised subjects were subsequently found to be C. difficile negative and excluded from analysis. If randomisation, was done prior to severity stratification, this may not sufficiently validate this concept of severity stratification in antibiotic choice as described by Zar 2007.

Two very large and for the most part well conducted studies of identical design compared fidaxomicin and vancomycin (Cornley 2012; Louie 2011). The quality issues in these studies are fairly minor compared to the above studies. The dropout rate was only 5%. These studies utilized a non‐inferiority design. The necessity of doing this rather than a standard analysis was not discussed, although the design itself has been a frequent topic of discussion elsewhere (Garattini 2007; Gotzsche 2006; Soonawala 2010). An intention‐to‐treat analysis (ITT) was not reported in either publication, rather a 'modified intention‐to‐treat' which excluded a number of dropouts and a per protocol analysis, excluding even more participants were reported. Again the purpose of this was not discussed, and curious insofar as including the dropouts as treatment failures in a standard ITT analysis demonstrates the superiority of fadixamicin over vancomycin (Analysis 5.1). The studies were both funded by Optimer Incorporated and the Louie 2011 manuscript was written by a part time employee of the company.

The most recent added studies (Louie 2015; Mullane 2015) are small and, like the previous two studies, theses studies also do not present results as a pure ITT analysis but a modified ITT or per protocol fashion. In this review, we conducted all analyses using the original number of patients randomised to each group as the denominator.

Potential biases in the review process