Abstract

Background

Dietary advice is the main strategy for managing gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). It remains unclear what type of advice is best.

Objectives

To assess the effects of different types of dietary advice for women with GDM for improving health outcomes for women and babies.

Search methods

We searched Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth's Trials Register (8 March 2016), PSANZ's Trials Registry (22 March 2016) and reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials comparing the effects of different types of dietary advice for women with GDM.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed study eligibility, risk of bias, and extracted data. Evidence quality for two comparisons was assessed using GRADE, for primary outcomes for the mother: hypertensive disorders of pregnancy; caesarean section; type 2 diabetes mellitus; and child: large‐for‐gestational age; perinatal mortality; neonatal mortality or morbidity composite; neurosensory disability; secondary outcomes for the mother: induction of labour; perineal trauma; postnatal depression; postnatal weight retention or return to pre‐pregnancy weight; and child: hypoglycaemia; childhood/adulthood adiposity; childhood/adulthood type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Main results

In this update, we included 19 trials randomising 1398 women with GDM, at an overall unclear to moderate risk of bias (10 comparisons). For outcomes assessed using GRADE, downgrading was based on study limitations, imprecision and inconsistency. Where no findings are reported below for primary outcomes or pre‐specified GRADE outcomes, no data were provided by included trials.

Primary outcomes

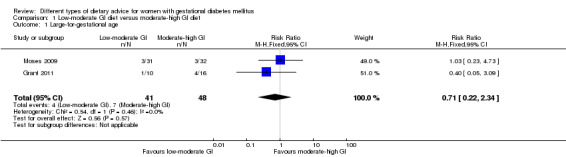

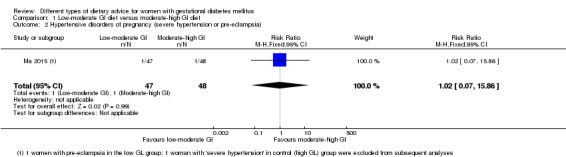

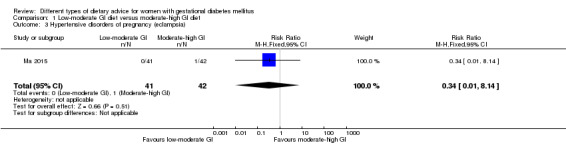

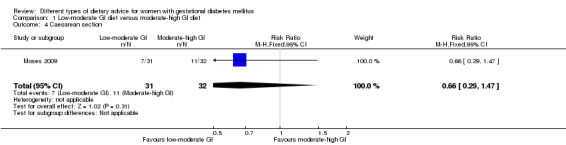

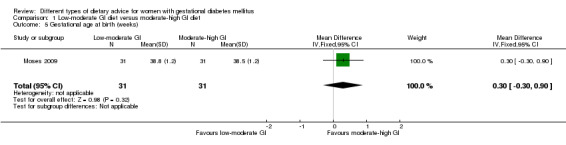

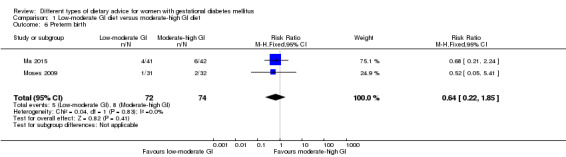

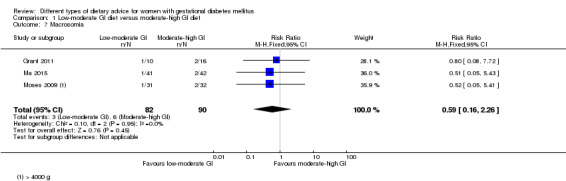

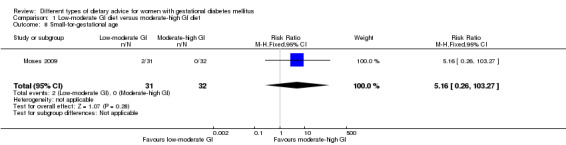

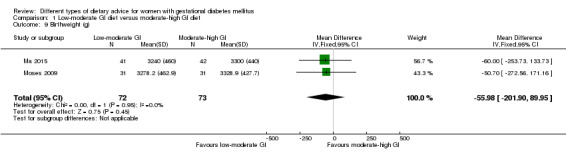

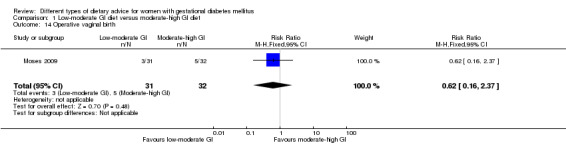

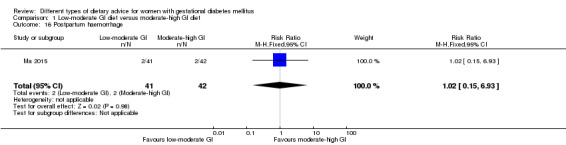

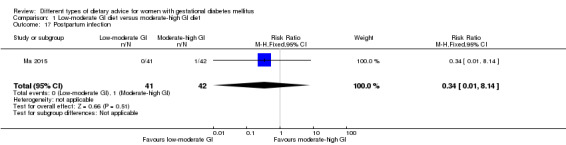

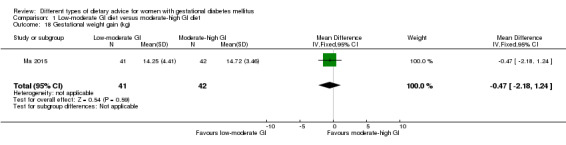

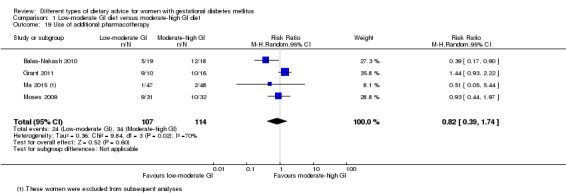

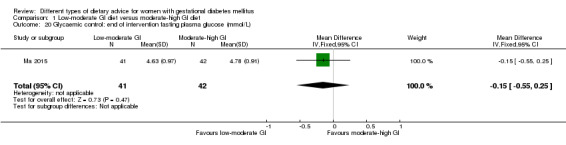

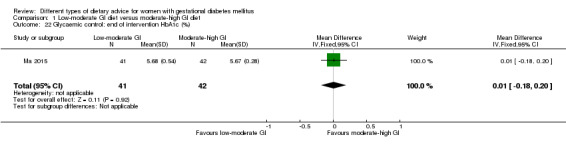

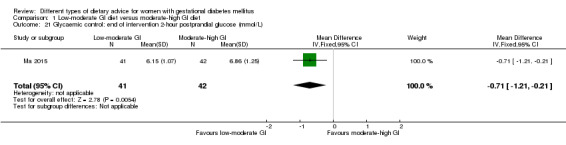

Low‐moderate glycaemic index (GI) versus moderate‐high GI diet (four trials): no clear differences observed for: large‐for‐gestational age (risk ratio (RR) 0.71, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.22 to 2.34; two trials, 89 infants; low‐quality evidence); severe hypertension or pre‐eclampsia (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.07 to 15.86; one trial, 95 women; very low‐quality evidence); eclampsia (RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.01 to 8.14; one trial, 83 women; very low‐quality evidence) or caesarean section (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.47; one trial, 63 women; low‐quality evidence).

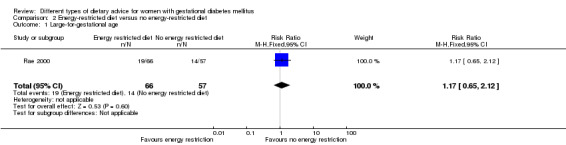

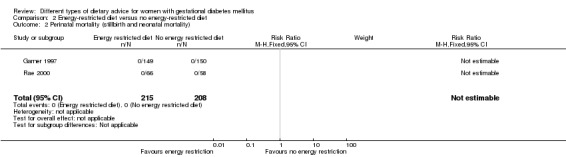

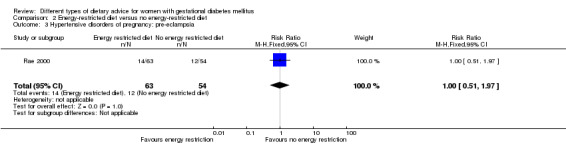

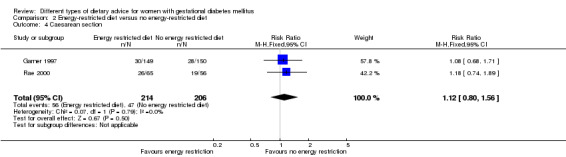

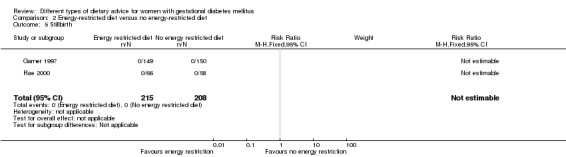

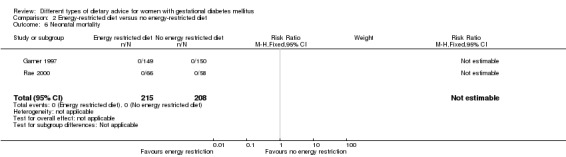

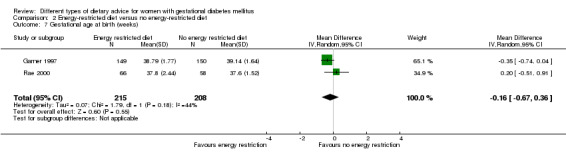

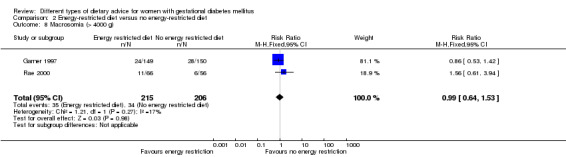

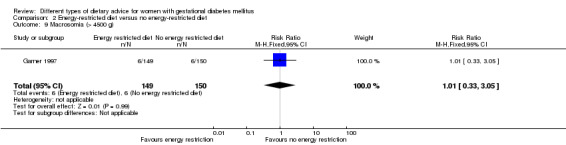

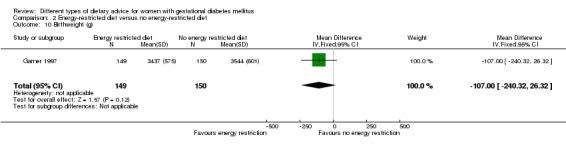

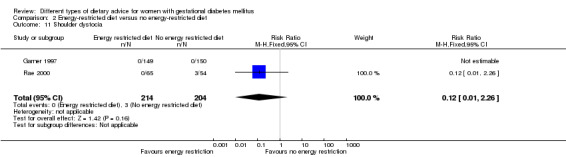

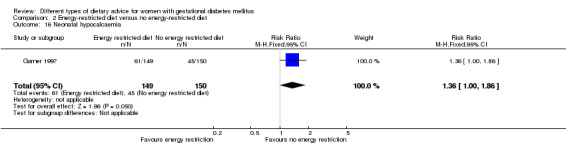

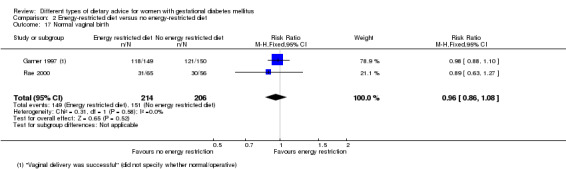

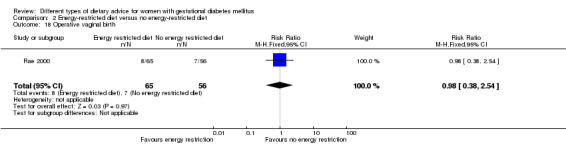

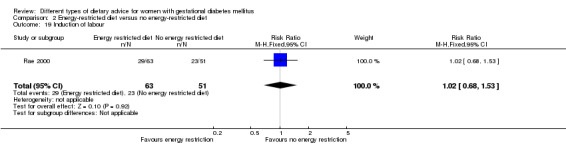

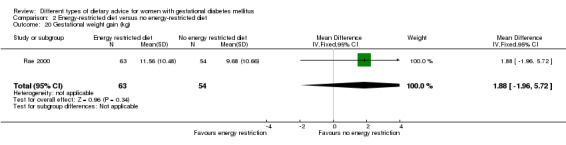

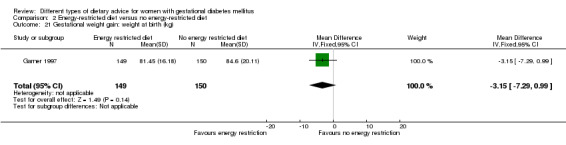

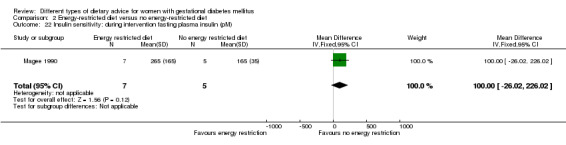

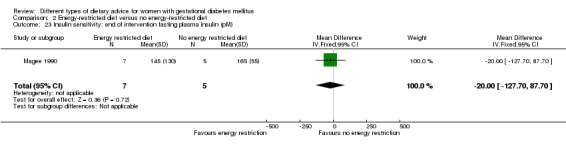

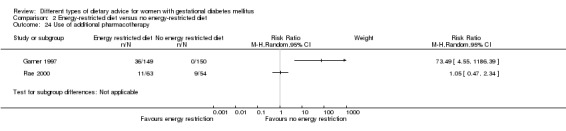

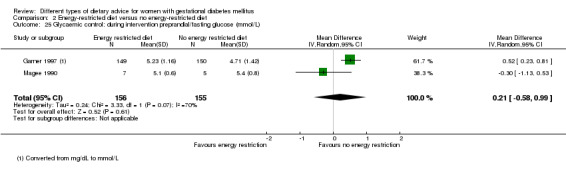

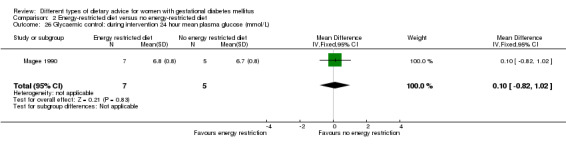

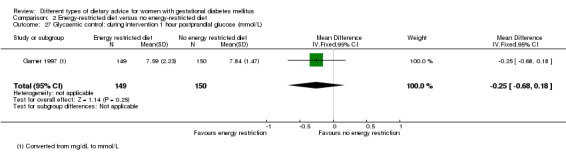

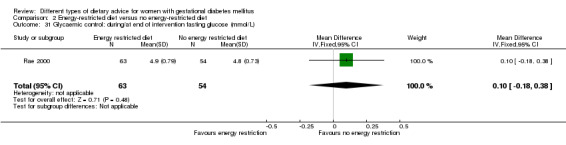

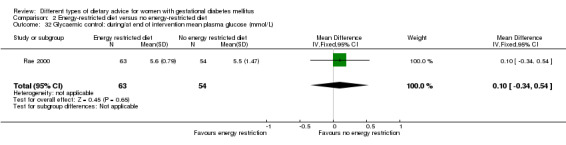

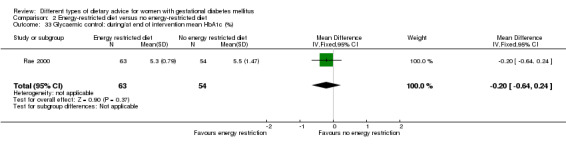

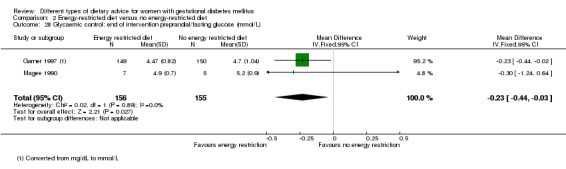

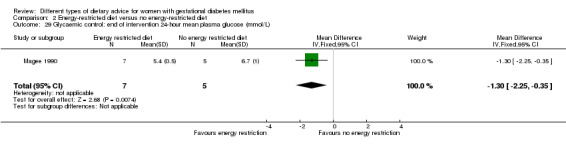

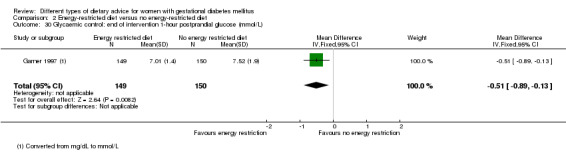

Energy‐restricted versus no energy‐restricted diet (three trials): no clear differences seen for: large‐for‐gestational age (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.65 to 2.12; one trial, 123 infants; low‐quality evidence); perinatal mortality (no events; two trials, 423 infants; low‐quality evidence); pre‐eclampsia (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.97; one trial, 117 women; low‐quality evidence); or caesarean section (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.56; two trials, 420 women; low‐quality evidence).

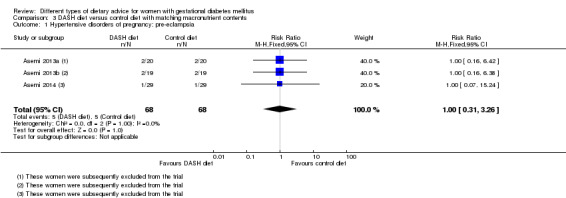

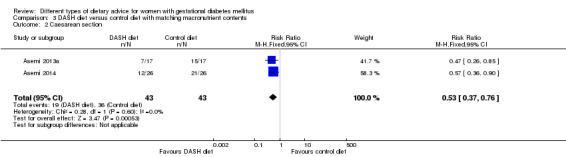

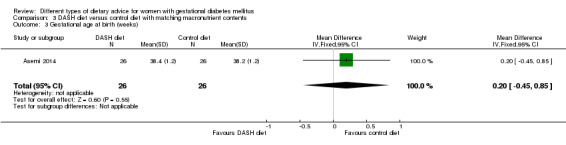

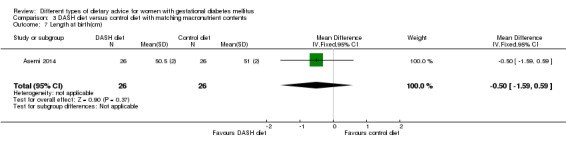

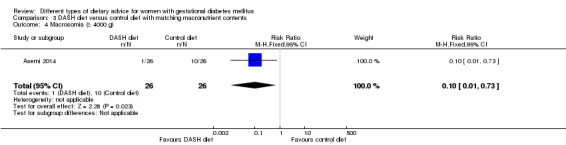

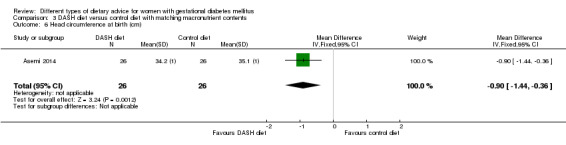

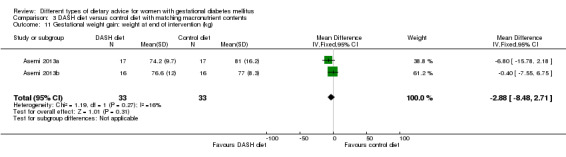

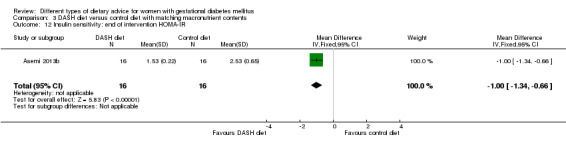

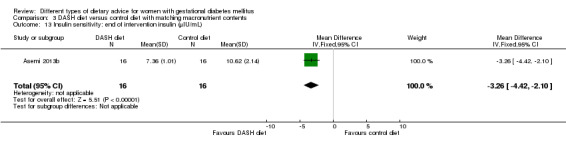

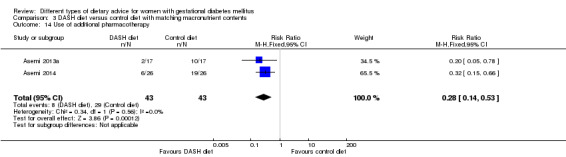

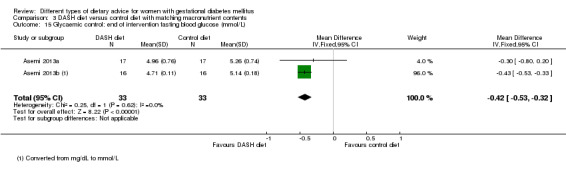

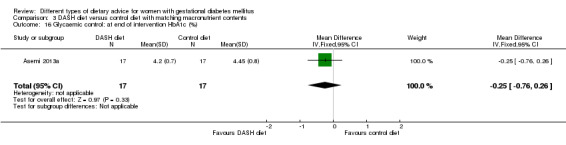

DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet versus control diet (three trials): no clear differences observed for: pre‐eclampsia (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.31 to 3.26; three trials, 136 women); however there were fewer caesarean sections in the DASH diet group (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.76; two trials, 86 women).

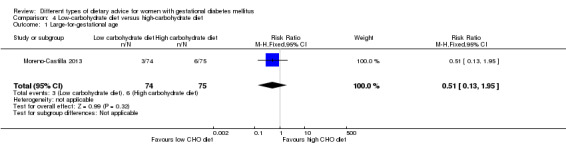

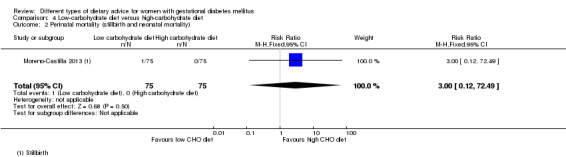

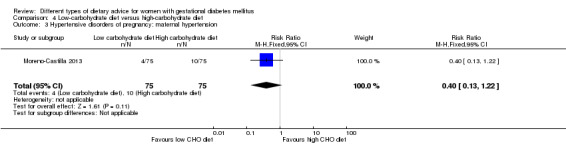

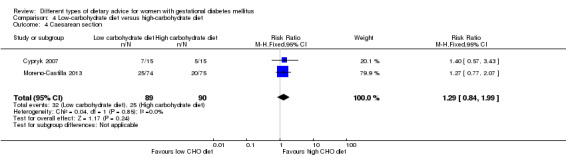

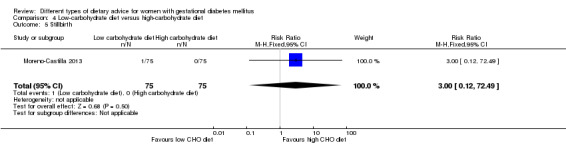

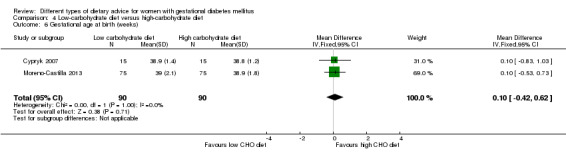

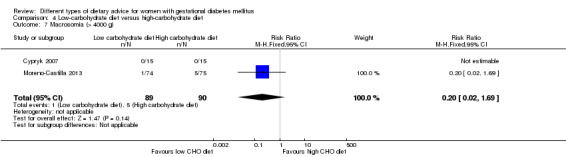

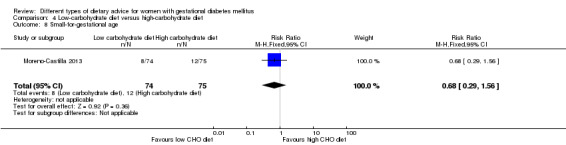

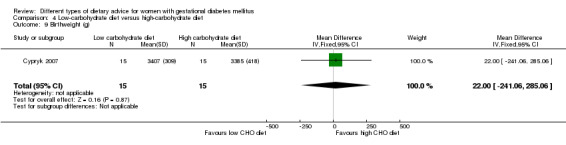

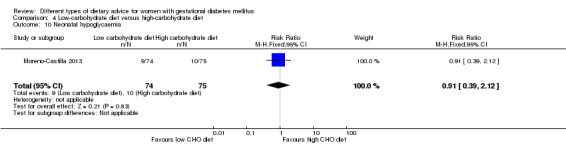

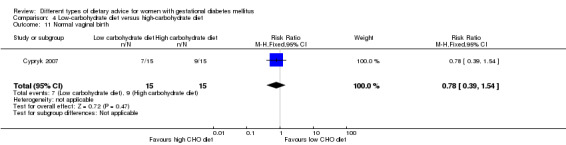

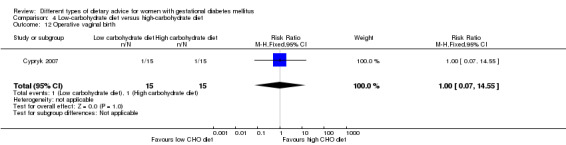

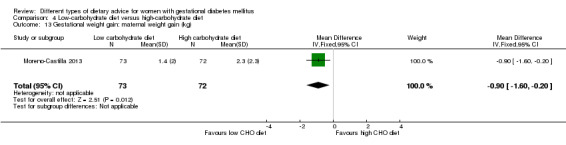

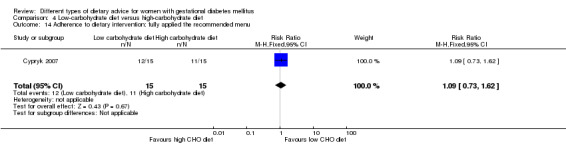

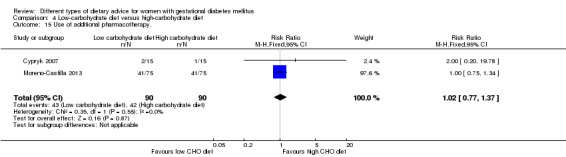

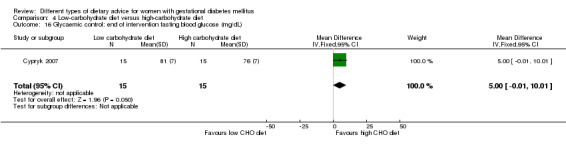

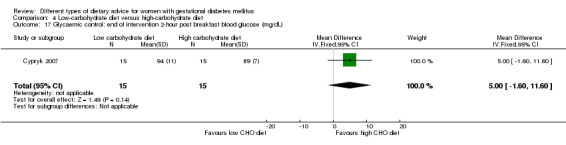

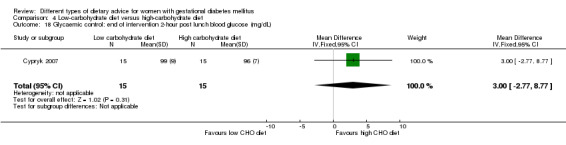

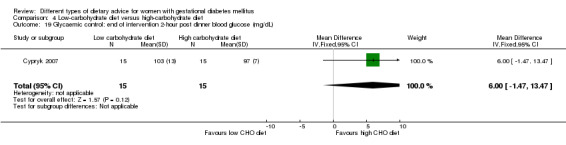

Low‐carbohydrate versus high‐carbohydrate diet (two trials): no clear differences seen for: large‐for‐gestational age (RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.13 to 1.95; one trial, 149 infants); perinatal mortality (RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.12 to 72.49; one trial, 150 infants); maternal hypertension (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.13 to 1.22; one trial, 150 women); or caesarean section (RR 1.29, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.99; two trials, 179 women).

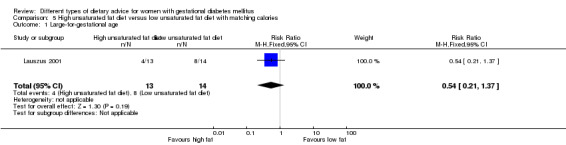

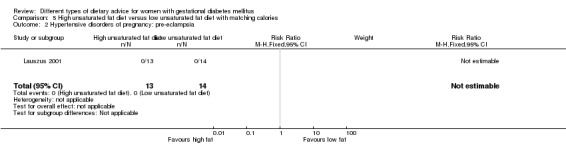

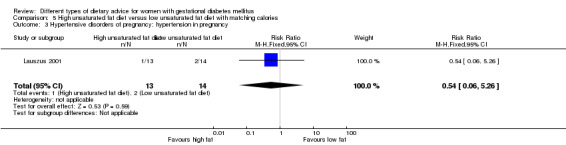

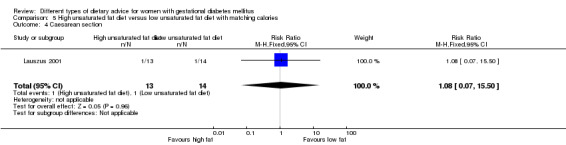

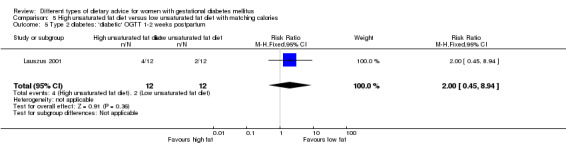

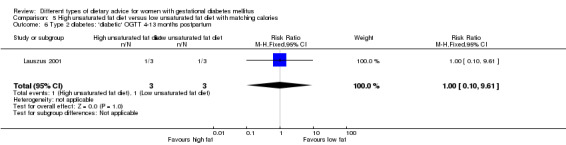

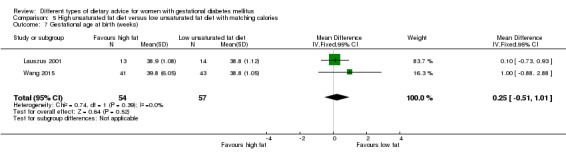

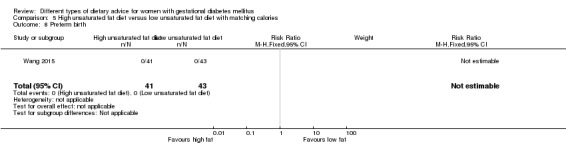

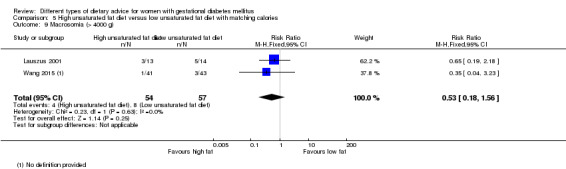

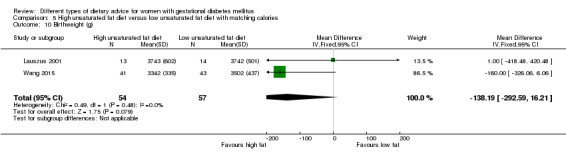

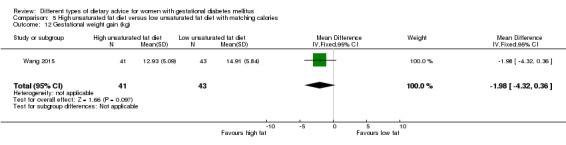

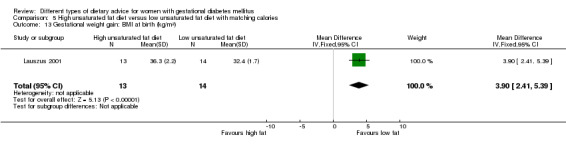

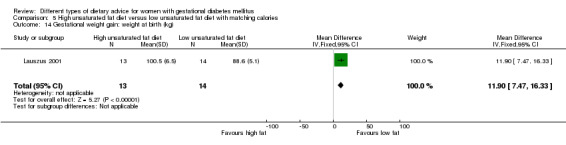

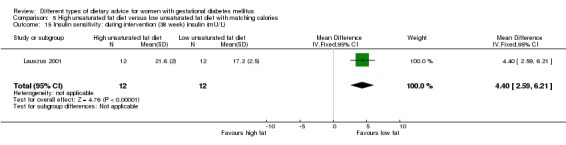

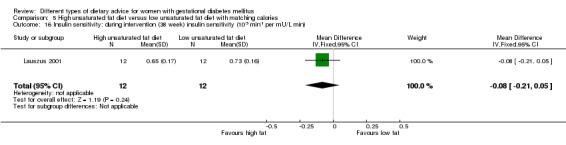

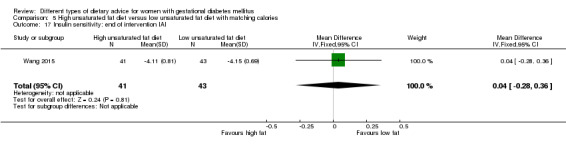

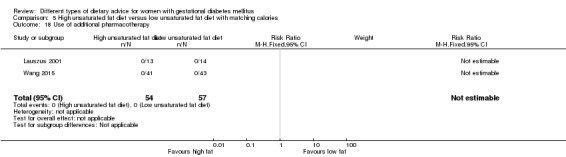

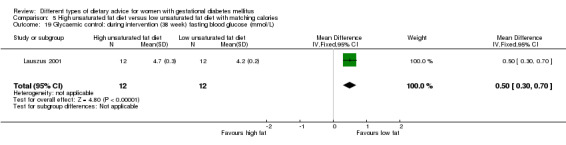

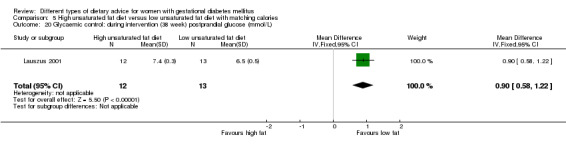

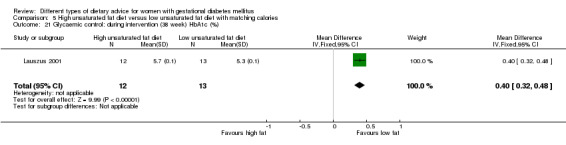

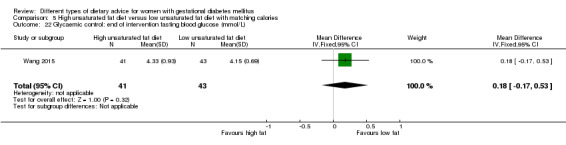

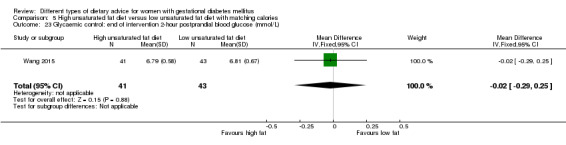

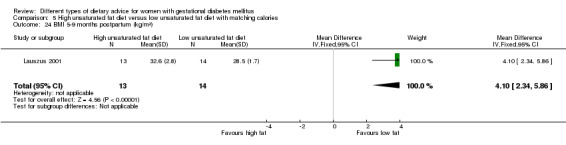

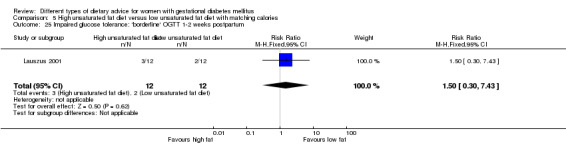

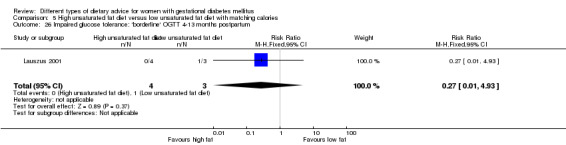

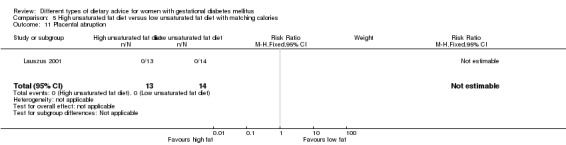

High unsaturated fat versus low unsaturated fat diet (two trials): no clear differences observed for: large‐for‐gestational age (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.21 to 1.37; one trial, 27 infants); pre‐eclampsia (no cases; one trial, 27 women); hypertension in pregnancy (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.06 to 5.26; one trial, 27 women); caesarean section (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.07 to 15.50; one trial, 27 women); diabetes at one to two weeks (RR 2.00, 95% CI 0.45 to 8.94; one trial, 24 women) or four to 13 months postpartum (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.10 to 9.61; one trial, six women).

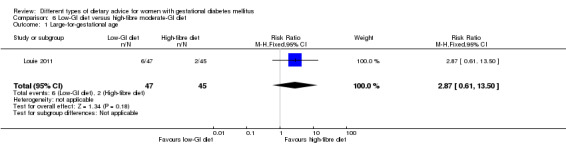

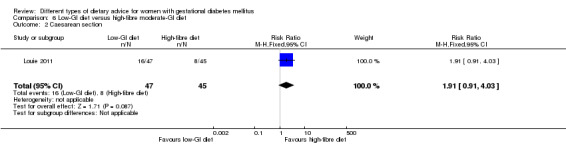

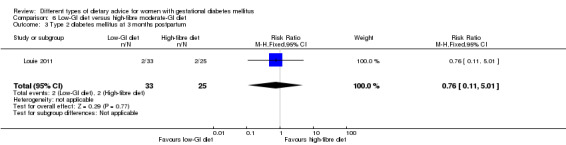

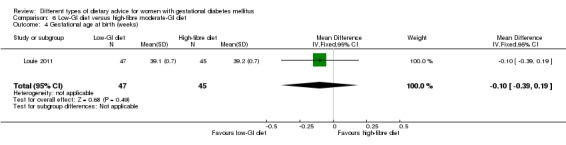

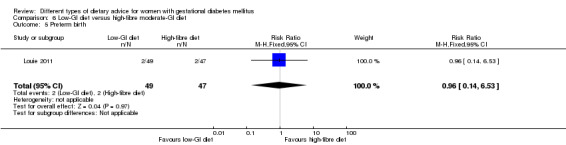

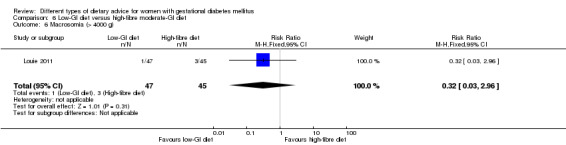

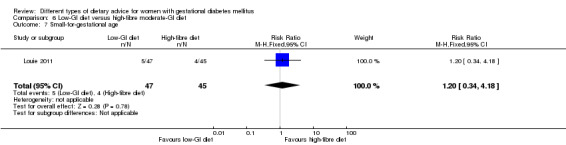

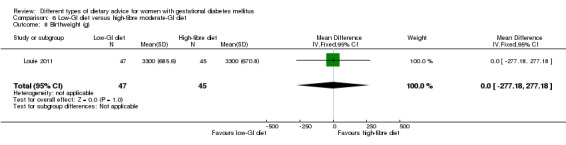

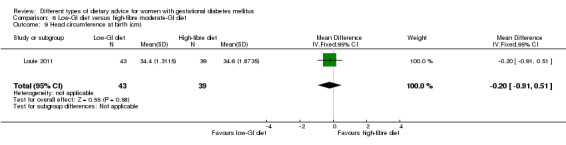

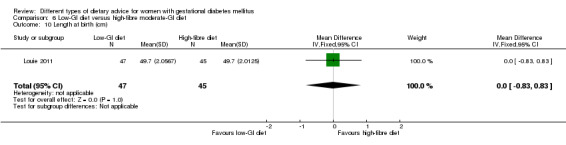

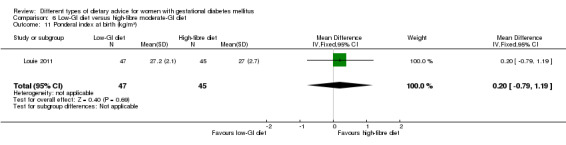

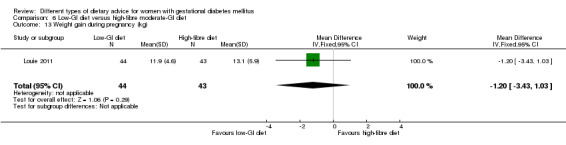

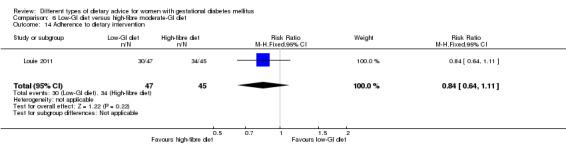

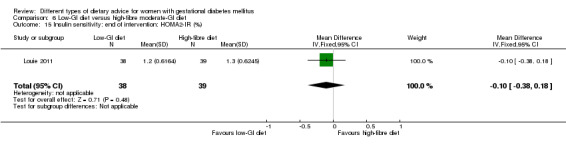

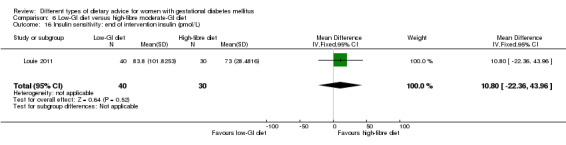

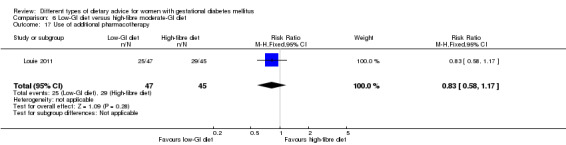

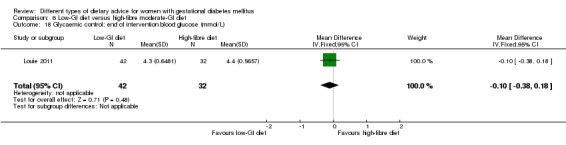

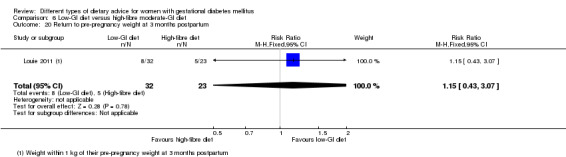

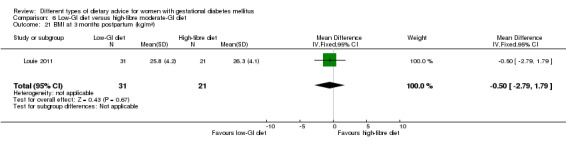

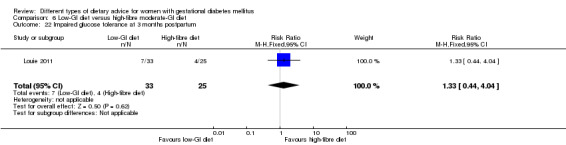

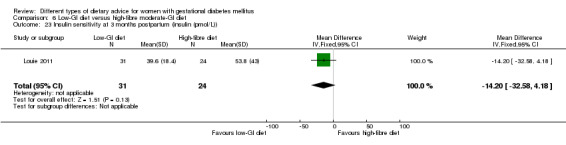

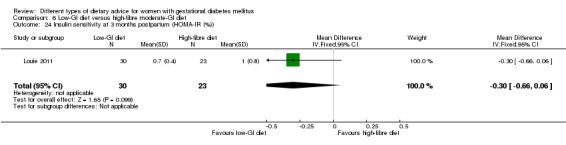

Low‐GI versus high‐fibre moderate‐GI diet (one trial): no clear differences seen for: large‐for‐gestational age (RR 2.87, 95% CI 0.61 to 13.50; 92 infants); caesarean section (RR 1.91, 95% CI 0.91 to 4.03; 92 women); or type 2 diabetes at three months postpartum (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.11 to 5.01; 58 women).

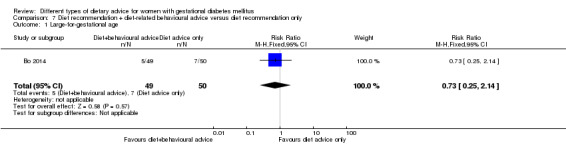

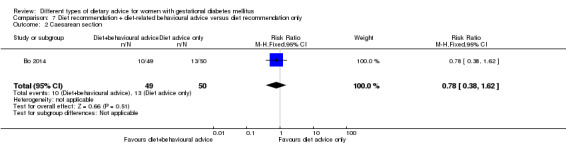

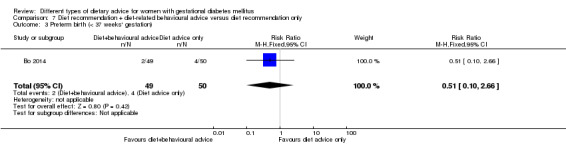

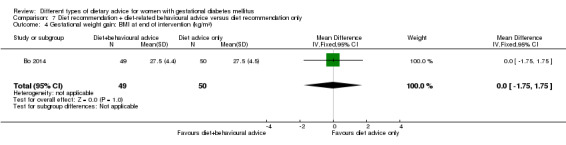

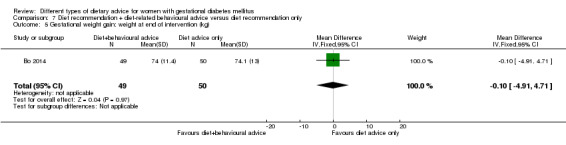

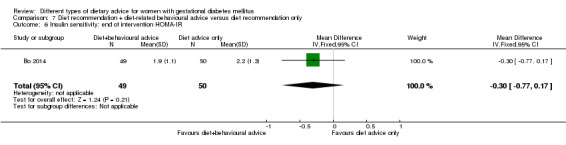

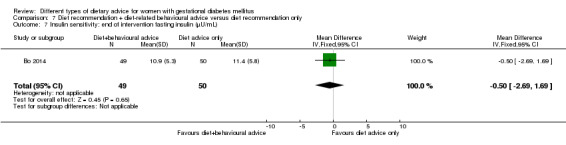

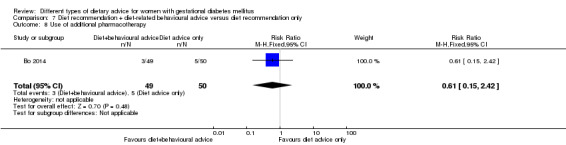

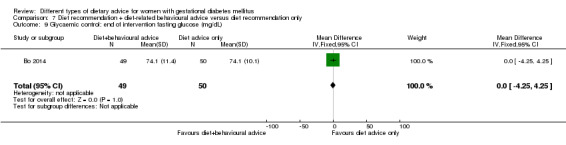

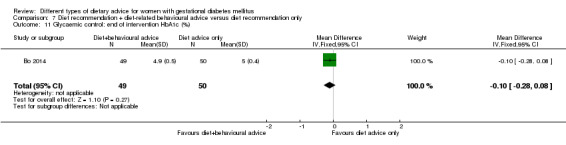

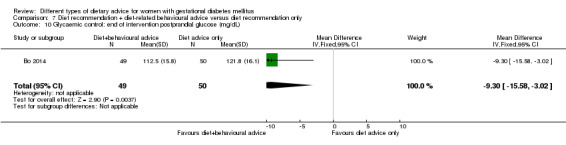

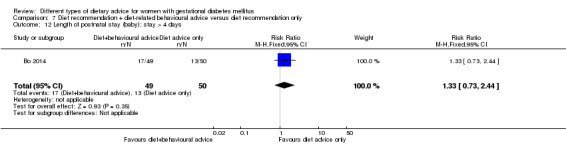

Diet recommendation plus diet‐related behavioural advice versus diet recommendation only (one trial): no clear differences observed for: large‐for‐gestational age (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.25 to 2.14; 99 infants); or caesarean section (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.62; 99 women).

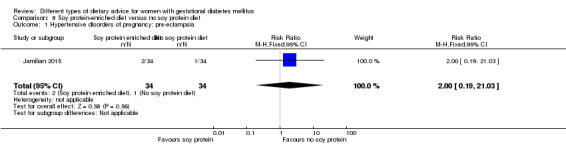

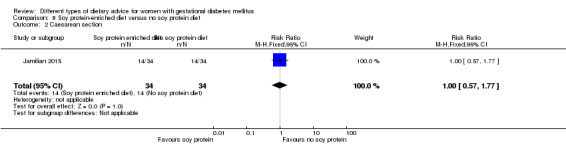

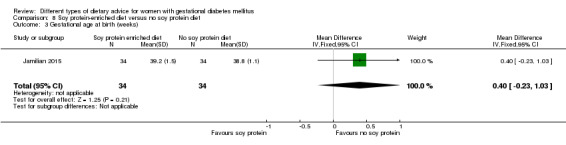

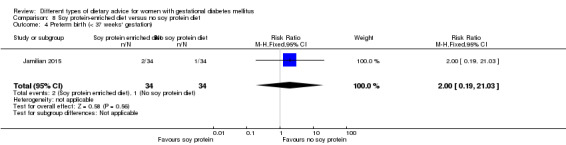

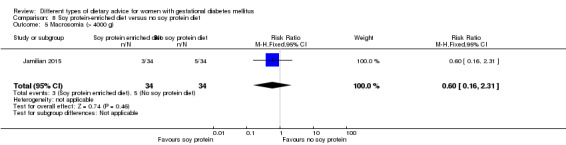

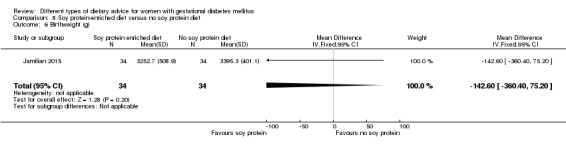

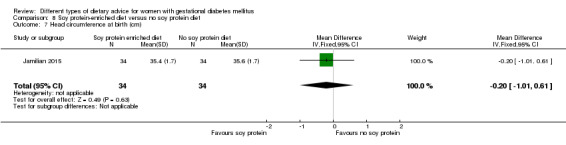

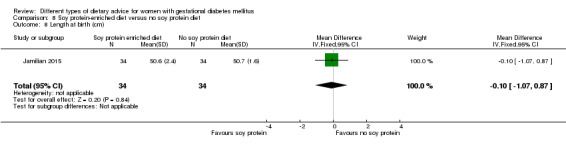

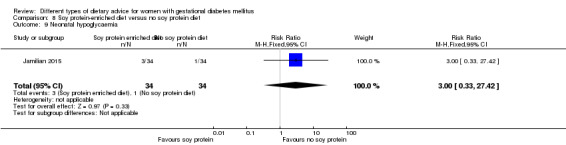

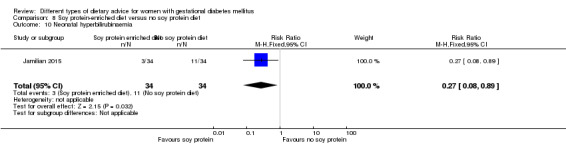

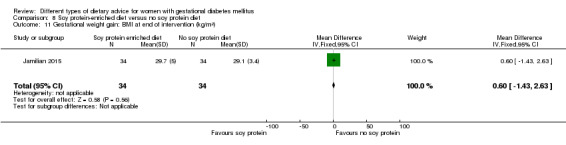

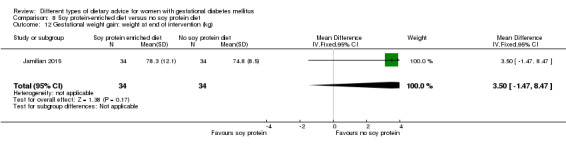

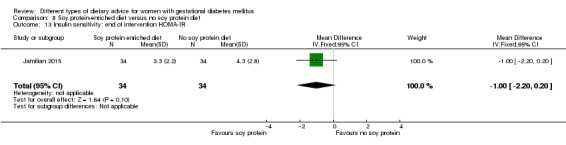

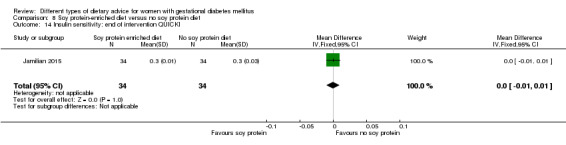

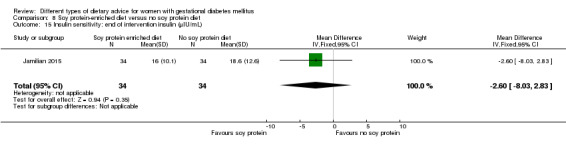

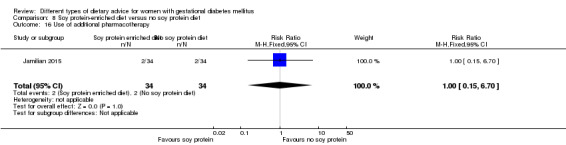

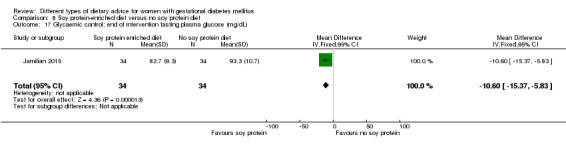

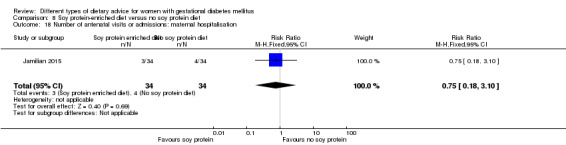

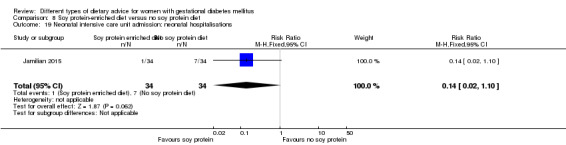

Soy protein‐enriched versus no soy protein diet (one trial): no clear differences seen for: pre‐eclampsia (RR 2.00, 95% CI 0.19 to 21.03; 68 women); or caesarean section (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.77; 68 women).

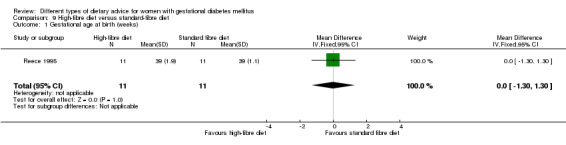

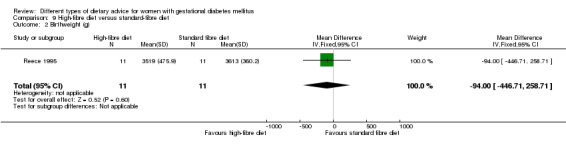

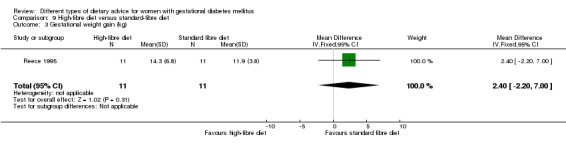

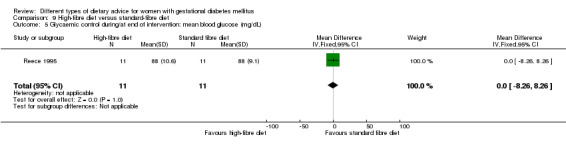

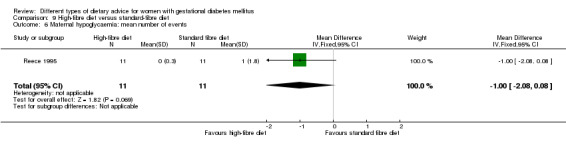

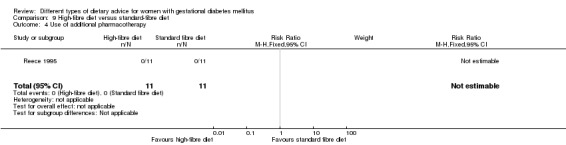

High‐fibre versus standard‐fibre diet (one trial): no primary outcomes reported.

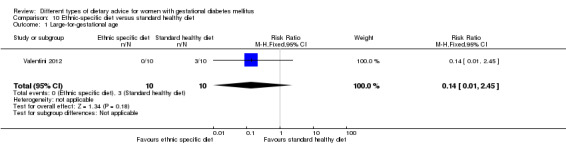

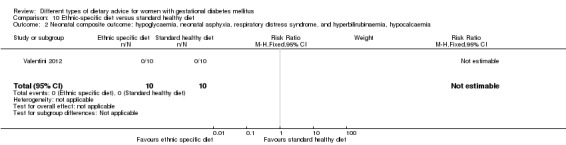

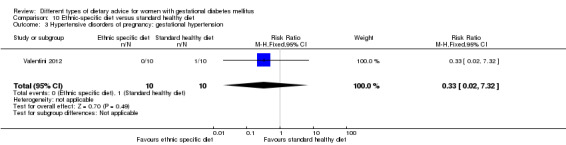

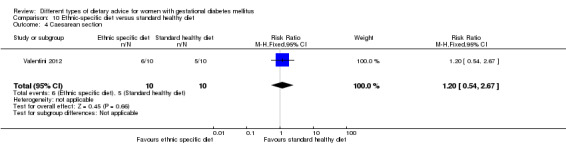

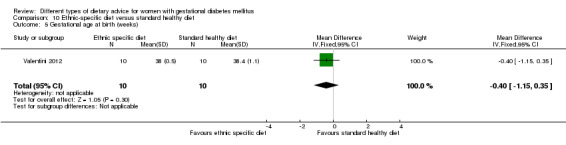

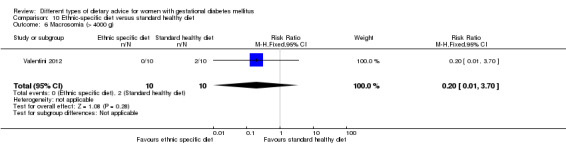

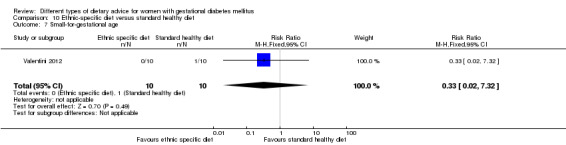

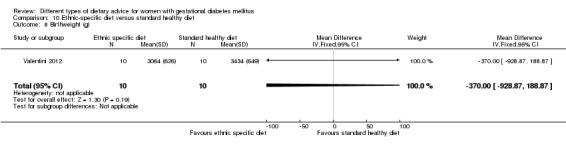

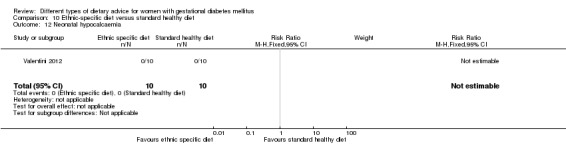

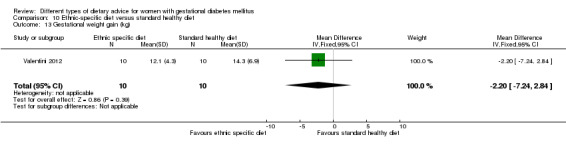

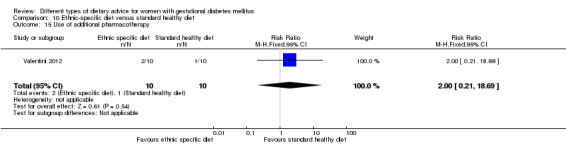

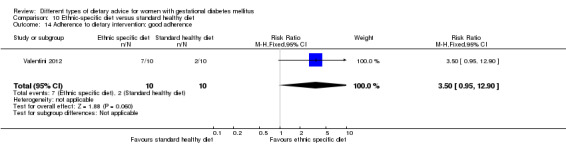

Ethnic‐specific versus standard healthy diet (one trial): no clear differences observed for: large‐for‐gestational age (RR 0.14, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.45; 20 infants); neonatal composite adverse outcome (no events; 20 infants); gestational hypertension (RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.02 to 7.32; 20 women); or caesarean birth (RR 1.20, 95% CI 0.54 to 2.67; 20 women).

Secondary outcomes

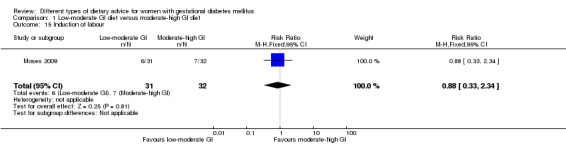

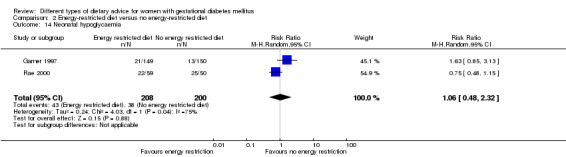

For secondary outcomes assessed using GRADE no differences were observed: between a low‐moderate and moderate‐high GI diet for induction of labour (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.33 to 2.34; one trial, 63 women; low‐quality evidence); or an energy‐restricted and no energy‐restricted diet for induction of labour (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.53; one trial, 114 women, low‐quality evidence) and neonatal hypoglycaemia (average RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.48 to 2.32; two trials, 408 infants; very low‐quality evidence).

Few other clear differences were observed for reported outcomes. Longer‐term health outcomes and health services use and costs were largely not reported.

Authors' conclusions

Evidence from 19 trials assessing different types of dietary advice for women with GDM suggests no clear differences for primary outcomes and secondary outcomes assessed using GRADE, except for a possible reduction in caesarean section for women receiving a DASH diet compared with a control diet. Few differences were observed for secondary outcomes.

Current evidence is limited by the small number of trials in each comparison, small sample sizes, and variable methodological quality. More evidence is needed to assess the effects of different types of dietary advice for women with GDM. Future trials should be adequately powered to evaluate short‐ and long‐term outcomes.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Caloric Restriction; Cesarean Section; Cesarean Section/statistics & numerical data; Diabetes, Gestational; Diabetes, Gestational/diet therapy; Diet, Carbohydrate‐Restricted; Diet, Diabetic; Dietary Carbohydrates; Dietary Carbohydrates/administration & dosage; Dietary Fiber; Dietary Fiber/administration & dosage; Glycemic Index; Hypertension; Hypertension/epidemiology; Pregnancy Complications, Cardiovascular; Pregnancy Complications, Cardiovascular/epidemiology; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Different types of dietary advice for women with gestational diabetes mellitus

What is the issue?

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a carbohydrate intolerance resulting in excess of sugar in the blood (hyperglycaemia) that begins or is first recognised during pregnancy. Dietary counselling or advice is the main strategy for helping women manage GDM, but it is not clear what dietary advice is best. In this review we set out to determine what dietary advice for women with GDM is best for reducing health complications for women and their babies.

Why is this important?

Women with GDM are at increased risk of developing high blood pressure and pre‐eclampsia (high blood pressure with swelling and protein in the urine) during pregnancy. The babies can grow large for their gestational age. As a result, they may be injured at birth, or cause injury to their mothers during the birth. The babies are more likely to have their birth induced or be born by caesarean section. Both the women and their babies are at increased risk of long‐term health problems including type 2 diabetes and disability.

What evidence did we find?

We searched the medical literature on 8 March 2016 and for this updated review we included 19 randomised controlled trials involving 1398 women with GDM and their babies. The overall risk of bias of the trials was unclear or moderate because of methodological limitations and the quality of the evidence was low or very low. The studies were generally small, few compared the same or similar interventions, and the outcomes they reported on were not comprehensive.

Ten different dietary advice comparisons were included. These were: 1) a low‐moderate glycaemic index (GI) diet with a moderate‐high GI diet (four trials); 2) an energy‐restricted diet with a diet with no energy restriction (three trials); 3) a 'Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH)' diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains and low‐fat dairy products with a control diet (three trials); 4) a low‐carbohydrate diet with a high‐carbohydrate diet (two trials); 5) a high unsaturated fat diet with a low unsaturated fat diet (two trials); 6) a low‐GI diet with a high‐fibre moderate‐GI diet (one trial); 7) diet recommendations and diet‐related behavioural advice with diet recommendations only (one trial); 8) a soy protein‐enriched diet with a diet with no soy protein (one trial); 9) a high‐fibre diet with a standard‐fibre diet (one trial); and 10) an ethnic‐specific diet with a standard healthy diet (one trial).

The review found no clear differences between the different types of dietary advice on the number of women with high blood pressure during pregnancy including pre‐eclampsia (nine trials in six different diet comparisons), large‐for‐gestational age babies (eight trials in seven different diet comparisons), perinatal deaths including stillbirth and death around the time of the birth (three trials in two different diet comparisons), type 2 diabetes development for the mother (two trials in two different diet comparisons), and a composite outcome of neonatal deaths or ill‐health (one trial in one diet comparison). No clear difference was seen in the number of babies delivered by caesarean section (10 trials in eight different diet comparisons) except for a reduction with a DASH diet. None of the included trials reported on later disability during childhood for the babies.

A range of other outcomes were looked at with no consistent differences reported between the different types of dietary advice. Outcomes related to longer‐term health for women and their babies, and the use and costs of health services were largely not reported.

What does this mean?

Dietary advice is the main strategy for managing GDM, however it remains unclear what type of advice is best. Conclusive evidence from randomised controlled trials is not yet available to guide practice, although a wide range of dietary advice interventions have been investigated. Few trials have compared the same or similar interventions, trials have been small and have reported limited findings. Further large, well‐designed, randomised controlled trials are required to assess the effects of different types of dietary advice for women with GDM for improving health outcomes for women and their babies in the short and long term.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings: Low‐moderate GI diet versus moderate‐high GI diet (maternal outcomes).

| Low‐moderate GI diet versus moderate‐high GI diet (maternal outcomes) | ||||||

|

Patient or population: pregnant women with GDM Settings: 4 RCTs in Australia, Canada, China and Mexico Intervention: low‐moderate GI diet Comparison: moderate‐high GI diet | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with moderate‐high GI diet | Risk with low‐moderate GI diet | |||||

| Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: severe hypertension or pre‐eclampsia | Study population | RR 1.02 (0.07 to 15.86) | 95 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW1,2 |

1 RCT in China | |

| 21 per 1000 | 21 per 1000 (2 to 333) | |||||

| Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: eclampsia | Study population | RR 0.34 (0.01 to 8.14) | 83 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW1,2 |

1 RCT in China | |

| 24 per 1000 | 8 per 1000 (0 to 195) | |||||

| Caesarean section | Study population | RR 0.66 (0.29 to 1.47) | 63 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW3,4 |

1 RCT in Australia | |

| 344 per 1000 | 227 per 1000 (100 to 506) | |||||

| Induction of labour | Study population | RR 0.88 (0.33 to 2.34) | 63 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW3,4 |

1 RCT in Australia | |

| 219 per 1000 | 193 per 1000 (72 to 512) | |||||

| Perineal trauma | Not reported | |||||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | Not reported | |||||

| Postnatal depression | Not reported | |||||

| Postnatal weight retention or return to pre‐pregnancy weight | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; GDM: gestational diabetes mellitus; GI: glycaemic index; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Design limitations: one study at high risk of selection and performance bias; unclear risk of detection bias.

2Imprecision: wide confidence interval crossing the line of no effect, few events and small sample size.

3Design limitations: one study at unclear risk of selection and detection bias; high risk of performance bias.

4Imprecision: wide confidence interval crossing the line of no effect and small sample size.

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings: Low‐moderate GI diet versus moderate‐high GI diet (neonatal/child/adulthood outcomes).

| Low‐moderate GI diet versus moderate‐high GI diet (neonatal/child/adulthood outcomes) | ||||||

|

Patient or population: pregnant women with GDM Settings: 4 RCTs in Australia, Canada, China and Mexico Intervention: low‐moderate GI diet Comparison: moderate‐high GI diet | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with moderate‐high GI diet | Risk with low‐moderate GI diet | |||||

| Large‐for‐gestational age | Study population | RR 0.71 (0.22 to 2.34) | 89 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW1,2 |

2 RCTs in Australia and Canada | |

| 146 per 1000 | 104 per 1000 (32 to 342) | |||||

| Perinatal mortality | Not reported | |||||

| Neonatal mortality or morbidity composite | Not reported | |||||

| Neonatal hypoglycaemia | Not reported | |||||

| Childhood/adulthood neurosensory disability | Not reported | |||||

| Childhood/adulthood adiposity | Not reported | |||||

| Childhood/adulthood type 2 diabetes mellitus | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; GDM: gestational diabetes mellitus; GI: glycaemic index; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Design limitations: one study at unclear risk of selection bias; two at high risk of performance bias and unclear risk of detection bias.

2Imprecision: wide confidence interval crossing the line of no effect and small sample sizes.

Summary of findings 3. Summary of findings: Energy‐restricted diet versus no energy‐restricted diet (maternal outcomes).

| Energy‐restricted diet versus no energy‐restricted diet | ||||||

|

Patient or population: pregnant women with GDM Settings: 3 RCTs in Australia, Canada and the United States Intervention: energy‐restricted diet Comparison: no energy‐restricted diet | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no energy‐restricted diet | Risk with energy‐restricted diet | |||||

| Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: pre‐eclampsia | Study population | RR 1.00 (0.51 to 1.97) | 117 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW1,2 |

1 RCT in Australia | |

| 222 per 1000 | 222 per 1000 (113 to 437) | |||||

| Caesarean section | Study population | RR 1.12 (0.80 to 1.56) | 420 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW3,4 |

2 RCTs in Australia and Canada | |

| 228 per 1000 | 255 per 1000 (182 to 356) | |||||

| Induction of labour | Study population | RR 1.02 (0.68 to 1.53) | 114 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW1,2 |

1 RCT in Australia | |

| 451 per 1000 | 460 per 1000 (307 to 690) | |||||

| Perineal trauma | Not reported | |||||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | Not reported | |||||

| Postnatal depression | Not reported | |||||

| Postnatal weight retention or return to pre‐pregnancy weight | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; GDM: gestational diabetes mellitus; GI: glycaemic index; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Design limitations: one study at unclear risk of selection and detection bias.

2Imprecision: wide confidence interval crossing the line of no effect and small sample size.

3Design limitations: two studies at unclear risk of selection bias; one at high risk of performance bias and unclear risk of detection bias.

4Imprecision: wide confidence interval crossing the line of no effect.

Summary of findings 4. Summary of findings: Energy‐restricted diet versus no energy‐restricted diet (neonatal/child/adulthood outcomes).

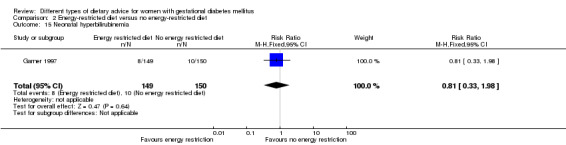

| Energy‐restricted diet versus no energy‐restricted diet (neonatal/child/adulthood outcomes) | ||||||

|

Patient or population: pregnant women with GDM Settings: 3 RCTs in Australia, Canada and the United States Intervention: energy‐restricted diet Comparison: no energy‐restricted diet | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no energy‐restricted diet | Risk with energy‐restricted diet | |||||

| Large‐for‐gestational age | Study population | RR 1.17 (0.65 to 2.12) | 123 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW1,2 |

1 RCT in Australia | |

| 246 per 1000 | 288 per 1000 (160 to 522) | |||||

| Perinatal mortality | Study population | Not estimable | 423 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW3,4 |

No events; 2 RCTs in Australia and Canada | |

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Neonatal mortality or morbidity composite | Not reported | |||||

| Neonatal hypoglycaemia | Study population | RR 1.06 (0.48 to 2.32) | 408 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW3,5,6 |

2 RCTs in Australia and Canada | |

| 190 per 1000 | 201 per 1000 (91 to 441) | |||||

| Childhood/adulthood neurosensory disability | Not reported | |||||

| Childhood/adulthood adiposity | Not reported | |||||

| Childhood/adulthood type 2 diabetes mellitus | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; GDM: gestational diabetes mellitus; GI: glycaemic index; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Design limitations: one study at unclear risk of selection and detection bias.

2Imprecision: wide confidence interval crossing the line of no effect and small sample size.

3Design limitations: two studies at unclear risk of selection bias; one at high risk of performance bias and unclear risk of detection bias.

4Imprecision: no events; relatively small sample sizes.

5Imprevision: wide confidence interval crossing the line of no effect.

6Inconsistency: substantial heterogeneity: I² = 75%.

Background

Description of the condition

Introduction and definition of gestational diabetes mellitus

Although there are no universally accepted diagnostic criteria, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) can be defined as 'glucose intolerance or hyperglycaemia (high blood glucose concentration) with onset or first recognition during pregnancy' (ACOG 2013; Hoffman 1998; Metzger 1998; Ministry of Health 2014; NICE 2015; WHO 2013). It is one of the most common pregnancy complications, with approximately 1% to 14% of pregnancies affected every year around the world (Mulla 2010). The prevalence of GDM continues to rise in line with the increasing prevalence of maternal obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (Bottalico 2007; Dabelea 2005; Mulla 2010; Petry 2010).

Pathophysiology of GDM

In pregnancy, insulin resistance increases with advancing gestation (Clapp 2006). Hormones secreted from the placenta, including tumour necrosis factor‐alpha (TNF‐α), placental lactogen, placental growth hormone, cortisol and progesterone are thought to be the likely triggers of these physiological changes (Clapp 2006; Devlieger 2008). Increasing insulin resistance in pregnancy, especially during the third trimester, helps to meet the increased nutrient requirement for fetal development and promotes fetal growth by increasing maternal glucose supply (Devlieger 2008). GDM results when the insulin secretion is inadequate for the degree of insulin resistance (Clapp 2006).

Risk factors for GDM

A range of factors have been found to increase the risk of GDM (Morisset 2010). Advancing maternal age and maternal overweight (body mass index (BMI) equal to or greater than 25 kg/m²) or obesity (equal to or greater than 30 kg/m²) are the two most common risk factors (Morisset 2010).

High parity, non‐white race/ethnicity, family history of diabetes, maternal high or low birthweight and polycystic ovarian syndrome are the known non‐modifiable risk factors for GDM (Cypryk 2008; Petry 2010; Solomon 1997). Additional non‐modifiable risk factors include history of having a macrosomic (birthweight 4000 g or more) baby and history of GDM (Petry 2010). Risk factors considered modifiable include those that are lifestyle‐related, such as physical inactivity (Chasan‐Taber 2008), having a low‐fibre and high‐glycaemic load (GL) diet (Zhang 2006), and excessive weight gain during pregnancy, especially for those who are overweight or obese (Hedderson 2010).

Health risks for GDM

Negative impacts of GDM on the health of women and their babies have been consistently reported (Crowther 2005; Landon 2009; Metzger 2008; Reece 2009).

Short‐term risks for women with GDM include developing pre‐eclampsia and an increased need for induction of labour (Anderberg 2010; Crowther 2005; Dodd 2007; Ju 2008; Landon 2009; Metzger 2008) and caesarean section (Dodd 2007; Landon 2009; Metzger 2008). The incidence of cephalopelvic disproportion, uterine rupture, shoulder dystocia and perineal lacerations is increased in women with GDM due to the higher likelihood of having a large‐for‐gestational age or macrosomic baby (Jastrow 2010). In the longer‐term, women who have a history of GDM have been estimated to have at least a seven‐fold risk of developing type 2 diabetes in the future when compared with women who have had a normoglycaemic pregnancy (Bellamy 2009), and up to 50% of women with GDM may develop type 2 diabetes within 10 years of the index pregnancy (Kim 2002).

One of the most significant health risks for babies born to mothers with GDM is being large‐for‐gestational age or macrosomic (Crowther 2005; Landon 2009; Metzger 2008; Reece 2009). Being a large‐for‐gestational age fetus or macrosomic infant is a surrogate for many of the complications associated with GDM (Esakoff 2009). Large‐for‐gestational age or macrosomic infants are at increased risk of birth injury, such as shoulder dystocia, perinatal asphyxia, bone fractures and nerve palsies (Henriksen 2008; Langer 2005; Metzger 2008). Babies large‐for‐gestational age at birth are more likely to be heavier at every age (adjusted for height) and to develop early overweight or obesity and type 2 diabetes (Pettitt 1993; Whincup 2008). In addition, babies born large‐for‐gestational age are at increased risk of developing metabolic syndrome (a cluster of risk factors defined by the occurrence of three of the following: obesity, hypertension, hypertriglyceridaemia and low high‐density lipoproteins cholesterol concentration) in childhood, adolescence or adulthood (Baker 1994; Guerrero‐Romero 2010; Harder 2009). Development of the metabolic syndrome during childhood predicts adult type 2 diabetes at 25 to 30 years of age (Morrison 2008). These health problems repeat across generations (Mulla 2010; Petitt 1985).

Besides the risks relating to large‐for‐gestational age or macrosomia, other adverse health consequences for babies born to women with GDM may include respiratory distress syndrome, hypoglycaemia, hyperbilirubinaemia (increased concentrations of bilirubin in the blood), cardiomyopathy (the deterioration of the function of the heart muscle layer), hypocalcaemia, hypomagnesaemia, polycythaemia (increase in the number of circulating red blood cells), and admission to the neonatal nursery (Metzger 2008; Reece 2009; Soler 1978). Other longer‐term risks for these babies include developing type 1 diabetes mellitus (Harder 2009) and having impaired neurosensory development (Rizzo 1997).

Management of GDM

The primary aims of management for GDM are to optimise glycaemic control and improve pregnancy outcomes (Alwan 2009; Balsells 2015; Brown 2016; Falavigna 2012; Horvath 2010; Kim 2010a). Providing dietary and lifestyle advice is usually recommended as the primary therapeutic strategy for women with GDM (ACOG 2013; Hoffman 1998; Ministry of Health 2014; NICE 2015). If diet and lifestyle management alone are not sufficient to achieve good maternal glycaemic control, insulin therapy or oral hypoglycaemics such as glyburide and metformin may be indicated (ACOG 2013; Hoffman 1998; Ministry of Health 2014; NICE 2015; Silva 2010; Simmons 2004). As a part of GDM management, maternal glucose monitoring and ultrasonography are advised to monitor treatment and guide care for birth (ACOG 2013; Hoffman 1998; Ministry of Health 2014; NICE 2015).

Description of the intervention

Dietary advice for managing GDM

Although it is widely accepted that dietary and lifestyle advice is the primary strategy for managing GDM, there is very little evidence on specific nutritional approaches such as total energy intake and nutrient distribution in GDM management (Cheung 2009; Kim 2010a; Metzger 2007). Elevated blood glucose concentrations, especially postprandial glucose elevations are associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes in GDM (De Veciana 1995). Dietary advice provided for women with GDM should ensure adequate nutrients for normal fetal growth and maternal health, but not induce weight loss or excessive weight gain during pregnancy; it should also aim to assist optimal glycaemic control (ACOG 2013; Hoffman 1998; Metzger 2007; Ministry of Health 2014; NICE 2015).

How the intervention might work

Total energy intake and weight gain during pregnancy

Given the high prevalence of overweight and obesity in women with GDM, dietary advice for appropriate pregnancy weight gain is often included as a part of nutritional management of GDM (Kim 2010a). It is estimated that the prevalence of GDM for women with a BMI within the range of 35 kg/m² to 64.9 kg/m² (extremely obese) is 15.4%, and decreases to 5.5%, 4.8% and 2.3% for women having a BMI within the ranges of 30 kg/m² to 34.9 kg/m² (obese), 25 kg/m² to 29.9 kg/m² (overweight) and 18.5 kg/m² to 24.9 kg/m² (normal weight), respectively (Kim 2010b). Small reductions in weight improve glycaemic control (ACOG 2005). However, severe calorie restriction and pregnancy weight loss are discouraged due to the risks of ketonaemia and small‐for‐gestational‐age infants (ACOG 2013; Hoffman 1998; Ministry of Health 2014; NICE 2015).

In 2009, the Institute of Medicine released new guidelines for weight gain during pregnancy, which are stratified by pre‐pregnancy BMI, i.e. women with a pre‐pregnancy BMI between 25 kg/m² and 29.9 kg/m² should aim for 6.8 kg to 11.4 kg weight gain and those with pre‐pregnancy BMI of 30 kg/m² or more should aim for 5 kg to 9 kg weight gain (IOM 2009). However, the degree of energy restriction for pre‐pregnancy overweight and obese women to achieve these weight gain goals is unknown (Kim 2010a).

The optional proportion of the total energy derived from each of the macronutrients in GDM management is still controversial (Kim 2010a). In Australia, the principles of dietary management of diabetes are also recommended for GDM management (i.e. carbohydrate contributes up to 50% total energy intake, fat accounts for less than 30% total energy and protein accounts for 10% to 20% total energy intake) (Colagiuri 2009; Hoffman 1998).

Carbohydrate and glycaemic index (GI)

Carbohydrate is an important source of energy, vitamins, minerals and fibre and is the main nutrient that affects blood glucose concentrations (Reader 2007); blood glucose can be affected by the total amount and type of carbohydrate (Reader 2007).

Evidence on the proportion of carbohydrate in diet therapy for GDM management is also controversial (Kim 2010a). Both low‐carbohydrate diets (i.e. carbohydrate accounting for less than 42% total energy intake) and high‐carbohydrate diets (i.e. carbohydrate accounting for 55% total energy intake) have been found beneficial in improving pregnancy outcomes in non‐randomised studies (Clapp 2002; Major 1998; Romon 2001). These inconsistent findings triggered the hypothesis that in addition to the total amount of carbohydrate, the type of carbohydrate may also be an important factor affecting postprandial blood glucose (Kim 2010a). Glycaemic index (GI) is a ranking of the effects of carbohydrates on blood glucose concentrations (Jenkins 1981). Foods with a low GI (less than 55) produce a lower postprandial glucose elevation and area under the curve; foods with a high GI (more than 70) produce a rapid increase in postprandial blood glucose concentrations (Jenkins 1981). In non‐pregnant individuals with diabetes, low‐GI diets help lower HbA1c and give better glycaemic control (Thomas 2010). During pregnancy, the concept of GI is still valid (Cheung 2009).

Fat and other nutrients

Polyunsaturated fatty acids may be protective against impaired glucose tolerance, while saturated fatty acids may increase glucose and insulin concentrations in women with GDM (Ilic 1999). However, the specific amount and sources of fat that are beneficial for GDM management are not clear (Kim 2010a). Therefore, recommendations on fat intake for women with GDM have not yet been promulgated (ACOG 2013; Hoffman 1998; Metzger 2007; NICE 2015).

Recommendations on the intake of other nutrients for women with GDM are usually based on the general recommendations for diabetes mellitus (Cheung 2009).

Why it is important to do this review

GDM affects a significant proportion of pregnant women each year and the incidence and prevalence are increasing worldwide (Bottalico 2007; Dabelea 2005; Mulla 2010). GDM is associated with a range of adverse outcomes for women and their babies and these adverse outcomes can repeat across generations (Metzger 2008; Mulla 2010). Dietary advice or counselling is the primary therapeutic strategy in GDM management (Hoffman 1998; Metzger 2007; NICE 2015). However, there is much inconsistency and uncertainty around the best dietary advice for women with GDM (Dornhorst 2002; Kim 2010a).

This review will provide reliable evidence on the effects of different types of dietary advice interventions for women with GDM. One Cochrane review has assessed the effects of dietary advice in pregnancy for preventing GDM (Tieu 2008). Another Cochrane review has assessed the effects of different treatments for women with GDM (Alwan 2009); however these reviews did not assess comparisons of different types of dietary advice. A new Cochrane review will assess lifestyle interventions for the treatment of women with GDM; specifically those including a combination of at least two of more of the following interventions: diet; physical activity; education; behavioural change; regimens of self‐monitoring of blood glucose; other (Brown 2015).

Objectives

To assess the effects of different types of dietary advice for women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) for improving health outcomes for women and babies.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All published randomised controlled trials and cluster‐randomised trials comparing the effects of different types of dietary advice for GDM management. We intended to include published abstracts if relevant outcome data were available. We planned to exclude quasi‐randomised trials and cross‐over trials.

Types of participants

Pregnant women with GDM. Diagnostic criteria for GDM based on oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) results were defined variously by individual trials according to the policies of local health authorities and professional organisations. Women were eligible regardless of age, gestation, parity or plurality.

We planned to include trials recruiting pregnant women with normal glycaemia, GDM or pre‐existing diabetes mellitus if subgroup data for women with GDM could be extracted separately.

Types of interventions

We planned to include interventions assessing any type of dietary advice for women with GDM in the review.

We planned to include trials comparing two or more different types of dietary advice interventions. We intended to compare two or more forms of the same type of dietary advice, i.e. standard dietary advice compared with individualised dietary advice, individual dietary education sessions compared with group dietary education sessions. We intended to compare different intensities of dietary intervention, i.e. single dietary counselling session compared with multiple dietary counselling sessions.

Types of outcome measures

For this update, we used the standard outcome set agreed by consensus between review authors of Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth systematic reviews for prevention and treatment of GDM and pre‐existing diabetes.

Primary outcomes

Fetal/neonatal/childhood outcomes

Large‐for‐gestational age (birthweight greater than or equal to the 90th percentile for gestational age).

Perinatal mortality (stillbirth and neonatal mortality).

Neonatal mortality or morbidity composite.

Neurosensory disability.

Maternal outcomes

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (including pre‐eclampsia, pregnancy‐induced hypertension, eclampsia).

Caesarean section.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Secondary outcomes

Fetal/neonatal outcomes

Stillbirth.

Neonatal mortality.

Gestational age at birth.

Preterm birth (less than 37 weeks' gestation and less than 32 weeks' gestation).

Apgar score less than seven at five minutes.

Macrosomia (birthweight greater than 4000 g as defined by authors).

Small‐for‐gestational age.

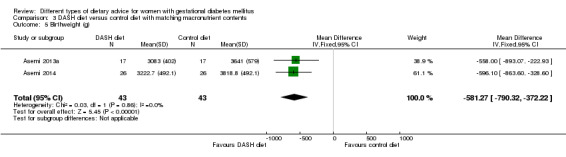

Birthweight and z‐score.

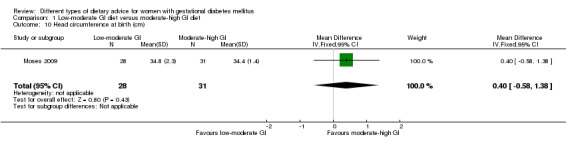

Head circumference at birth and z‐score.

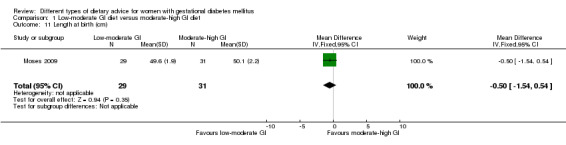

Length at birth and z‐score.

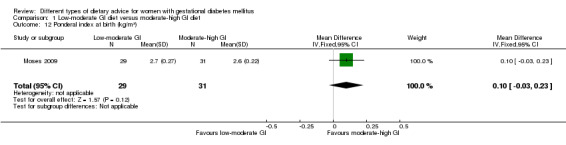

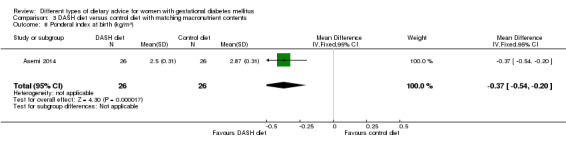

Ponderal index at birth.

Adiposity at birth (e.g. as measured by BMI, skinfold thickness).

Shoulder dystocia.

Bone fracture.

Nerve palsy.

Respiratory distress syndrome.

Hypoglycaemia.

Hyperbilirubinaemia.

Hypocalcaemia.

Polycythaemia.

Childhood outcomes

Weight and z‐scores.

Height and z‐scores.

Head circumference and z‐scores.

Adiposity (e.g. as measured by BMI, skinfold thickness).

Blood pressure.

Type 1 diabetes mellitus.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Impaired glucose tolerance (as defined by authors).

Insulin sensitivity (as defined by authors).

Dyslipidaemia or metabolic syndrome.

Educational achievement.

Adulthood outcomes

Weight.

Height.

Adiposity (e.g. as measured by BMI, skinfold thickness).

Cardiovascular health (as defined by authors, including blood pressure, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome).

Type 1 diabetes mellitus.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Impaired glucose tolerance (as defined by authors).

Insulin sensitivity (as defined by authors).

Employment, education and social status/achievement.

Maternal outcomes

Perinatal

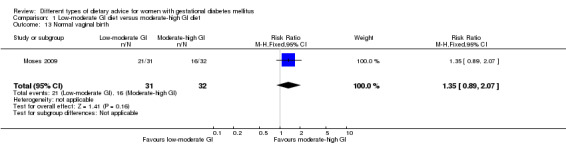

Mode of birth (normal vaginal birth; operative vaginal birth).

Induction of labour.

Perineal trauma.

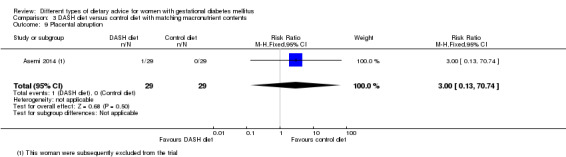

Placental abruption.

Postpartum haemorrhage.

Postpartum infection.

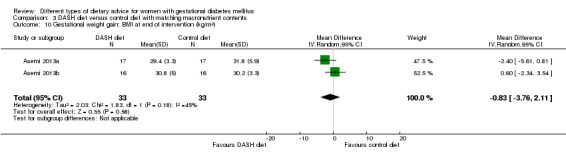

Gestational weight gain.

Adherence to dietary intervention.

Behaviour changes associated with dietary intervention.

Insulin sensitivity (as defined by authors).

Sense of well‐being and quality of life.

Views of the intervention.

Breastfeeding (e.g. at discharge, six weeks postpartum).

Use of additional pharmacotherapy.

Glycaemic control during or at the end of treatment.

Hypoglycaemia.

Mortality.

Long term

Postnatal depression.

Postnatal weight retention or return to pre‐pregnancy weight.

BMI.

GDM in a subsequent pregnancy.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Impaired glucose tolerance (as defined by authors).

Insulin sensitivity (as defined by authors).

Cardiovascular health (as defined by authors, including blood pressure, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome).

Health services outcomes

Number of hospital or health professional visits (e.g. midwife, obstetrician, physician, dietitian, diabetic nurse).

Number of antenatal visits or admissions.

Length of antenatal stay.

Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

Length of postnatal stay (mother).

Length of postnatal stay (baby).

Costs to families associated with the management provided.

Costs associated with the dietary intervention.

Cost of maternal care.

Cost of offspring care.

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth.

Electronic searches

We searched Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register by contacting their Information Specialist (8 March 2016).

The Register is a database containing over 22,000 reports of controlled trials in the field of pregnancy and childbirth. For full search methods used to populate Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register including the detailed search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL; the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service, please follow this link to the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth in the Cochrane Library and select the ‘Specialized Register ’ section from the options on the left side of the screen.

Briefly, Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register is maintained by their Information Specialist and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

monthly searches of CINAHL (EBSCO);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Search results are screened by two people and the full text of all relevant trial reports identified through the searching activities described above is reviewed. Based on the intervention described, each trial report is assigned a number that corresponds to a specific Pregnancy and Childbirth review topic (or topics), and is then added to the Register. The Information Specialist searches the Register for each review using this topic number rather than keywords. This results in a more specific search set which has been fully accounted for in the relevant review sections (Included studies; Excluded studies).

In addition, we searched the Perinatal Society of Australia and New Zealand (PSANZ) Trial Registry (22 March 2016) using the search terms detailed in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We searched reference lists of trials and other review articles.

We did not apply any language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For methods used in the previous version of this review, seeHan 2013.

For this update, the following methods were used for assessing the 34 reports that were identified as a result of the updated search.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third review author.

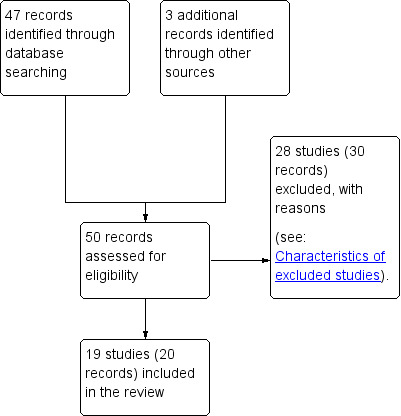

We created a Study flow diagram to map out the number of records identified, included and excluded (see Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third review author. Data were entered into Review Manager software (RevMan 2014) and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details. We contacted the authors of Grant 2011, Lauszus 2001, Louie 2011; Moses 2009, and Rae 2000 for further information.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; 'as treated' analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study's pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study's pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we planned to assess the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it is likely to impact on the findings. In future updates, we will explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Assessing the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach

For this update the GRADE approach as outlined in the GRADE Handbook was used, where possible, to assess the quality of the body of evidence relating to the following outcomes for the following two comparisons, which were selected as the 'main' comparisons, based on containing the most information (included trials and participants), and thus, based on perceived importance (of trialists).

Low‐moderate GI diet versus moderate‐high GI diet.

Energy‐restricted diet versus no energy‐restricted diet.

Maternal outcomes

Perinatal

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (including pre‐eclampsia, pregnancy‐induced hypertension, eclampsia).

Caesarean section.

Induction of labour.

Perineal trauma.

Long term

Type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Postnatal depression.

Postnatal weight retention or return to pre‐pregnancy weight.

Fetal/neonatal/childhood/adulthood outcomes

Fetal/neonatal

Large‐for‐gestational age.

Perinatal mortality (stillbirth and neonatal mortality).

Neonatal mortality or morbidity composite.

Hypoglycaemia.

Childhood/adulthood

Neurosensory disability.

Adiposity (e.g. as measured by BMI, skinfold thickness).

Type 2 diabetes mellitus.

We used the GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool to import data from Review Manager (RevMan 2014) in order to create 'Summary of findings' tables. A summary of the intervention effect and a measure of quality for the above outcomes, where possible, was produced using the GRADE approach. The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence can be downgraded from 'high quality' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates or potential publication bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we have presented results as summary risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we have presented results as summary mean differences with 95% confidence intervals. We planned to use standardised mean differences to combine trials that measured the same outcome, but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We did not identify any cluster‐randomised trials for inclusion. If we identify cluster‐randomised trials in future updates of this review, we will include them in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials. We will adjust their sample sizes using the methods described in the Handbook using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Cross‐over trials

We considered cross‐over trials as inappropriate for this research question.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. In future updates, if more eligible trials are included, the impact of including trials with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect will be explored by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, analyses were carried out, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if an I² was greater than 30% and either a Tau² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity. Had we identified substantial heterogeneity (above 30%), we planned to explore it using pre‐specified subgroup analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

In future updates, if there are 10 or more studies in a meta‐analysis, we will investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry is suggested by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using Review Manager software (RevMan 2014). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials were examining the same intervention, and the trials' populations and methods were judged sufficiently similar.

Where there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or where substantial statistical heterogeneity was detected, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary, if an average treatment effect across trials was considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary has been treated as the average range of possible treatment effects and we have discussed the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect was not considered clinically meaningful, we did not combine trials. Where we have used random‐effects analyses, the results have been presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of Tau² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where identified, we planned to investigate substantial heterogeneity using subgroup analyses.

Maternal characteristics, ways of delivering dietary advice and intensities of the dietary advice interventions may impact health outcomes. We planned to carry out the following subgroup analyses, however, there were insufficient data to do so.

Maternal characteristics

Maternal age: older than or equal to 35 years of age versus younger than 35 years of age.

Ethnicity: high‐risk versus low‐risk ethnicities.

Parity: 0 versus 1 to 2; versus 3 or more.

Maternal education level: less than 12 years versus 12 years of more.

Maternal BMI at or before trial entry: less than 18.5 kg/m² versus 18.5 kg/m² to 24.9 kg/m² versus 25 kg/m² to 29.9 kg/m² versus 30 kg/m² to 39.9 kg/m² versus 40 kg/m² or more.

Ways of delivering dietary advice

Standard dietary advice versus individualised dietary advice.

Individual dietary counselling versus group dietary education.

Face‐to‐face dietary advice versus non‐face‐to‐face dietary advice (e.g. phone counselling, information package, etc.).

Intensities of dietary intervention

Single dietary counselling session versus multiple dietary counselling sessions.

We planned to use primary outcomes in subgroup analyses.

We planned to assess subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan (RevMan 2014). We planned to report the results of subgroup analyses quoting the Chi² statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to carry out sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of trial quality assessed by concealment of allocation, high attrition rates, or both, with poor quality trials (rated high or unclear risk of bias for these domains) being excluded from the analyses in order to assess whether this makes any difference to the overall result. However, there were insufficient data to do so. If we had included cluster‐randomised trials, we also planned to carry out sensitivity analyses to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit, however we did not include any cluster‐randomised trials.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We identified a total of 47 potentially eligible studies (50 records) (see Figure 1).

Following the application of eligibility criteria, we included 19 randomised controlled trials (20 records) (Asemi 2013a; Asemi 2013b; Asemi 2014; Balas‐Nakash 2010; Bo 2014; Cypryk 2007; Garner 1997; Grant 2011; Jamilian 2015; Lauszus 2001; Louie 2011; Ma 2015; Magee 1990; Moreno‐Castilla 2013; Moses 2009; Rae 2000; Reece 1995; Valentini 2012; Wang 2015) and excluded 28 studies (30 records) (Cao 2012; Chua 2008; Corrado 2011; Deveer 2013; Ehrlich 2014; Gillen 2004; Gillmer 1986; Gonai 2014; Hernandez 2012; Hernandez 2014; Hernandez 2016; Hosseinzadeh‐Shamsi‐Anar 2012; Hu 2014; Ilic 1999; Jamilian 2016; Knopp 1991; Li 2013; Lindsay 2014; Lindsay 2015; Louie 2013; Ma 2011; Nolan 1984; Perichart‐Perara 2012; Reader 2006; Samimi 2015; Thangaratinam 2014; Yu 2013; Yuan 2015).

Included studies

Setting

Of the 19 included trials, four trials were conducted in Iran (Asemi 2013a; Asemi 2013b; Asemi 2014; Jamilian 2015); three were from Australia (Louie 2011; Moses 2009; Rae 2000); two trials each were conducted in the USA (Magee 1990; Reece 1995), Canada (Garner 1997; Grant 2011), Italy (Bo 2014; Valentini 2012) and China (Ma 2015; Wang 2015); one was from Denmark (Lauszus 2001), one from Mexico (Balas‐Nakash 2010), one from Poland (Cypryk 2007) and one from Spain (Moreno‐Castilla 2013).

Participants

A total of 1398 women and their babies were randomised to the 19 included trials, with sample sizes of the included trials ranging from 12 (Magee 1990) to 300 (Garner 1997).

For the detailed descriptions of inclusion and exclusion criteria across the included trials, see Characteristics of included studies.

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) diagnosis

Different GDM diagnostic criteria were used across the 19 included trials. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) criteria were used in five trials (Asemi 2013a; Asemi 2013b; Asemi 2014; Jamilian 2015; Valentini 2012). The Australian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society (ADIPS) criteria were used in two trials (Louie 2011; Moses 2009). One trial each used the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria (Cypryk 2007), Hatem Criteria (Garner 1997), Canadian Diabetes Association (CDA) criteria (Grant 2011), Carpenter and Coustan's criteria (Magee 1990) and the National Diabetes Data Group criteria (Moreno‐Castilla 2013). The International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Group (IADPSG) criteria were used in Wang 2015.

Lauszus 2001 used a three‐hour 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) for GDM diagnosis, and GDM was defined as two or more plasma glucose concentrations above three standard deviations of the mean. Rae 2000 used criteria as fasting blood glucose > 5.4 mmol/L and/or two‐hour blood glucose > 7.9 mmol/L following a 75 g OGTT. Ma 2015 used a three‐hour 75 g OGTT for GDM diagnosis, with women diagnosed if their blood glucose met two or more of the following criteria: fasting > 5.8mmol/L, one‐hour > 10.6 mmol/L, two‐hour > 9.2 mmol/L and three‐hour > 8.1 mmol/L.

There was no information on diagnostic criteria for GDM in Balas‐Nakash 2010, Bo 2014, or Reece 1995.

Two trials reported the incidence of type 2 diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in the early postpartum period (Lauszus 2001; Louie 2011). The diagnostic criteria for type 2 diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance based on OGTT were not specified in Lauszus 2001 and the WHO criteria were used in Louie 2011.

While 16 trials included only women with GDM, women with both GDM and type 2 diabetes were included in Balas‐Nakash 2010; women with GDM and insulin‐dependent diabetes were included in Reece 1995 and women with GDM and impaired glucose tolerance not meeting GDM diagnostic criteria were included in Grant 2011.

Maternal body mass index (BMI)

Women's BMI at trial entry varied greatly across the 19 included trials. Only three trials had specific eligibility criteria related to BMI (Bo 2014; Magee 1990; Rae 2000). Bo 2014 excluded women with a BMI > 40 kg/m²; Rae 2000 included women whose weights were greater than 110% of their ideal weight (100% ideal body weight was defined as BMI of 25 kg/m²); and Magee 1990 included only women who were obese; with obesity as greater than 120% of ideal body weight.

There were no eligibility criteria based on BMI in the remaining 16 trials (Asemi 2013a; Asemi 2013b; Asemi 2014; Balas‐Nakash 2010; Cypryk 2007; Garner 1997; Grant 2011; Jamilian 2015; Lauszus 2001; Louie 2011; Ma 2015; Moreno‐Castilla 2013; Moses 2009; Reece 1995; Valentini 2012; Wang 2015), though in 11 trials, some information was reported regarding women's pre‐pregnancy or baseline BMI (mean (SD)).

In Ma 2015, the mean pre‐pregnancy BMI was 21.9 (3.1) kg/m² for women in the low‐moderate GI diet group, and 21.2 (2.8) kg/m² for the women in the moderate‐high GI diet group. In Wang 2015, the mean pre‐pregnancy mean BMI was 21.4 (3.0) kg/m² for the women in the high unsaturated fat diet group and 22.2 (3.6) kg/m² for the women in the low unsaturated fat diet group. In Louie 2011, 68% of women had a pre‐pregnancy BMI of less than 25 kg/m²; the pre‐pregnancy mean BMI was 23.9 (4.4) kg/m² for women in the low‐GI diet group and 24.1 (5.7) kg/m² for women in the high‐fibre moderate‐GI diet group. In Valentini 2012, women's mean pre‐pregnancy BMI were 25.7 (3.6) kg/m² for the ethnic‐specific diet group and 24.1 (4.7) kg/m² for the standard healthy diet group. In Moreno‐Castilla 2013, women's pre‐pregnancy mean BMI were 25.4 (5.7) kg/m² for the low‐carbohydrate diet group and 26.6 (5.5) kg/m² for the high‐carbohydrate diet group. In Jamilian 2015, women's mean baseline BMI in the soy protein‐enriched diet group was 28.9 (5.0) kg/m², and 28.4 (3.4) kg/m² in the no soy protein diet group. In Asemi 2013a, Asemi 2013b and Asemi 2014, women's mean trial entry BMI ranged from 29.0 (3.2) kg/m² to 30.2 (4.6) kg/m² for the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet group and 29.7 (3.3) kg/m² to 31.4 (5.7) kg/m² for the control diet group. In Moses 2009, the mean trial entry BMI was 32.0 (1.2) kg/m² for the women in the low‐moderate GI diet group and 32.8 (1.4) kg/m² for the women in the moderate‐high GI diet group. In Lauszus 2001, women were recruited after their diagnosis of GDM and were then instructed to follow a high‐carbohydrate diet until 33 weeks' gestation where they were randomised. No information was reported on women's weight or BMI at recruitment, but baseline weight was reported for women at randomisation; the mean BMI at 33 weeks' gestation were 35 (2.4) kg/m² and 32.2 (1.5) kg/m² for women in the high unsaturated fat and the low unsaturated diet groups, respectively (Lauszus 2001).

No information was reported regarding BMI at trial entry in Cypryk 2007 and Garner 1997; and for Bo 2014 it was not reported for the two randomised groups at entry; a further three trials did not report BMI at trial entry for the relevant subgroup of women with GDM (Balas‐Nakash 2010; Grant 2011; Reece 1995).

Interventions and comparisons

We have structured the comparisons, ordered by quantity of information available (number of included trials, and participants in the comparisons) as:

low‐moderate GI diet versus moderate‐high GI diet: Balas‐Nakash 2010; Grant 2011; Ma 2015; Moses 2009;

energy‐restricted diet versus no energy‐restricted diet: Garner 1997; Magee 1990; Rae 2000;

DASH diet versus control diet with matching macronutrient contents: Asemi 2013a; Asemi 2013b; Asemi 2014;

low‐carbohydrate diet versus high‐carbohydrate diet: Cypryk 2007; Moreno‐Castilla 2013;

high unsaturated fat diet versus low unsaturated diet with matching calories: Lauszus 2001; Wang 2015;

low‐GI diet versus high‐fibre moderate‐GI diet: Louie 2011;

diet recommendation and diet‐related behavioural advice versus diet recommendation only: Bo 2014;

soy protein‐enriched diet versus no soy protein diet: Jamilian 2015;

high‐fibre versus standard‐fibre diet: Reece 1995;

ethnic‐specific diet versus standard healthy diet: Valentini 2012.

Five trials assessed the effects of a low‐ (or low‐moderate) GI diet (Balas‐Nakash 2010; Grant 2011; Louie 2011; Ma 2015; Moses 2009). In Balas‐Nakash 2010, women in the low‐GI diet group were advised to select low‐to‐moderate GI carbohydrate food, while women in the control group were allowed any type of carbohydrate food. There was no information reported on the definitions for low‐GI carbohydrate, moderate‐GI carbohydrate or high‐GI carbohydrate in this trial (Balas‐Nakash 2010). Grant 2011 advised women in the low‐GI diet group to select their starch food from an exchange list of low‐ and intermediate‐GI choices, while women in the comparison group were asked to select their starch choices from an exchange list of intermediate‐ and high‐GI food (Grant 2011). Food exchange lists for study diets were provided in the published report for Grant 2011, which indicated that the carbohydrate food recommended for women in low‐GI diet group having a GI range of 26 to 66 and for women in the control group having a GI range of 58 to 87. In Ma 2015, women in the low‐GL group were given an exchange list of low‐GL foods and women in the control group were given an exchange list of intermediate‐ to high‐GL foods. In Moses 2009, women in the low‐GI diet group were advised to select low‐GI food (55 or less) based on the international tables of GI and GL values (Atkinson 2008) and women in the comparison group were advised to follow a high‐fibre, low‐sugar diet. In Louie 2011, a low‐GI diet aiming for a GI target of no higher than 50, was compared with a moderate‐GI diet (GI around 60); thus this trial was included in a separate comparison from the aforementioned four trials.

Three trials compared an energy‐restricted diet with a no energy‐restriction diet (Garner 1997; Magee 1990; Rae 2000). In Garner 1997, a calorie‐restricted diet of 35 kcal per kg ideal body weight per day was compared with an unrestricted healthy diet during pregnancy. Women in Magee 1990 were hospitalised during the intervention period. In the first week of hospitalisation, women in both groups had a 2400 kcal per day diet, with 50% total energy derived from carbohydrate, 30% from fat and 20% from protein (Magee 1990). During the second week of hospitalisation, one group of women continued the diet consumed in the first week, while women in the other group restricted their daily energy intake to 1200 kcal, which was achieved by reducing serving size without changing diet content (Magee 1990). In Rae 2000, a 6800 kJ to 7600 kJ per day diet was compared with a diet providing 8600 kJ to 9500 kJ.

Three trials assessed the effect of the DASH eating pattern (Asemi 2013a; Asemi 2013b; Asemi 2014). In Asemi 2013a,Asemi 2013b and Asemi 2014, diet for women in the DASH diet group and the control diet group had similar composition of 45% to 55% carbohydrates, 15% to 20% protein and 25% to 30% fat. However, diet for women in the DASH diet group was rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains and low‐fat dairy products, and low in saturated fats, cholesterol, refined grains and sweets. The amount of sodium intake was 2400 mg per day or less (Asemi 2013a; Asemi 2013b; Asemi 2014).

Two trials assessed different carbohydrate content in the diet for women with GDM (Cypryk 2007; Moreno‐Castilla 2013). The daily total energy intake from carbohydrate was 40% to 45% for the low‐carbohydrate diet group and 55% to 60% for the control group (Cypryk 2007; Moreno‐Castilla 2013).

Two trials compared the effect of high unsaturated fat diet with low unsaturated diet with matching calories for managing GDM (Lauszus 2001; Wang 2015). Lauszus 2001 compared a high‐carbohydrate diet with a high‐monounsaturated fat diet, without specifying the proportion of daily energy sources for the diets. In Wang 2015, women in the high polyunsaturated fatty acid diet group were advised to use 45 to 50 g sunflower oil daily for cooking while women in the low polyunsaturated fatty acid diet group were instructed to use 20 g sunflower oil for daily cooking.

Bo 2014 assessed the effects of providing additional behavioural recommendations for assisting healthy dietary choices. Women in both groups received individually‐prescribed diets, with 48% to 50% from carbohydrates, 18% to 20% from protein, 30% to 35% from fat, fibre 20 to 25 g per day and no alcohol (Bo 2014). For women in the intervention group, additional oral or written recommendations including strategies for out of home eating, healthy cooking and food shopping were provided (Bo 2014).

In Jamilian 2015, women in the intervention group received a diet containing 0.8 g per kg protein with 35% animal protein, 35% soy protein and 30% other plant proteins, and women in the control group received the same amount of protein with 70% animal and 30% plant proteins.

In Reece 1995, a high‐fibre diet containing 80 g of fibre per day was compared with a standard American Diabetes Association (ADA) diet providing 20 g fibre per day.

In Valentini 2012, ethnic‐specific diet including typical foods from women's home countries were compared with standard healthy diet for women with GDM. Both diets had the same nutrient composition and daily energy intake was from 1800 to 2200 kcal, depending on women's pre‐pregnancy BMI.

Outcomes

Sixteen included studies reported perinatal outcomes for women and/or their babies and have not reported on any longer‐term outcomes (Asemi 2013a; Asemi 2013b; Asemi 2014; Balas‐Nakash 2010; Bo 2014; Cypryk 2007; Garner 1997; Grant 2011; Jamilian 2015; Ma 2015; Moreno‐Castilla 2013; Moses 2009; Rae 2000; Reece 1995; Valentini 2012; Wang 2015). Two trials have reported limited early postpartum outcomes including risk of maternal type 2 diabetes development (Lauszus 2001; Louie 2011). One trial has reported biochemical outcomes only (Magee 1990).

SeeCharacteristics of included studies for further details.

Excluded studies

A total of 28 trials were excluded.

Six trials were excluded as they were cross‐over trials (Hernandez 2012; Hernandez 2014; Hernandez 2016; Ilic 1999; Louie 2013; Nolan 1984), and one was excluded as it was not a randomised trial (Knopp 1991). Four trials were excluded as their populations did not meet our inclusion criteria: (Deveer 2013 included women with borderline GDM; Lindsay 2014: including obese pregnant women and excluded women with GDM; Ma 2011 included women with abnormal glucose metabolism; Thangaratinam 2014 included pregnant women with metabolic risk factors but not GDM. In Perichart‐Perara 2012, outcome data were reported for a mixed population of women with GDM and type 2 diabetes).

Fourteen trials were excluded as they did not assess different types of dietary advice interventions: five compared different types of care, or lifestyle interventions for women with GDM, where dietary advice was included as part of the care/intervention (Cao 2012; Ehrlich 2014; Gillen 2004; Gillmer 1986; Reader 2006); one assessed a five day diet intervention (Hu 2014); and 10 assessed effects of dietary supplements (including magnesium chloride, myoinositol, lactobacilli GG yogurt, vitamin D, omega‐3 fatty acids, probiotics, nutritional liquid supplement, capsaicin) for women with GDM (Chua 2008; Corrado 2011; Gonai 2014; Hosseinzadeh‐Shamsi‐Anar 2012; Jamilian 2016; Li 2013; Lindsay 2015; Samimi 2015; Yu 2013; Yuan 2015).

SeeCharacteristics of excluded studies for further details.

Risk of bias in included studies

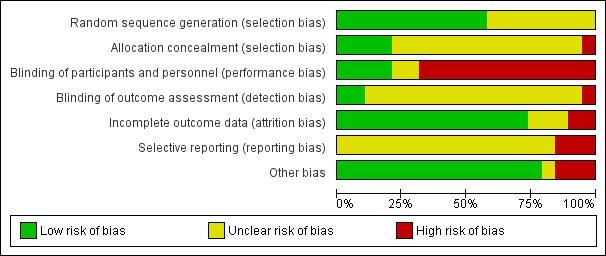

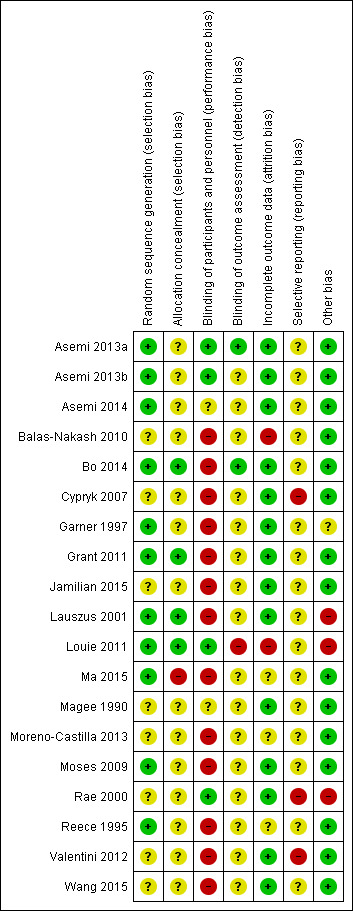

The 19 included studies had various levels of risk of bias. SeeFigure 2 and Figure 3 for further details.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Eleven of the 19 included trials reported adequate methods for generating their random sequence (Asemi 2013a; Asemi 2013b; Asemi 2014; Bo 2014; Garner 1997; Grant 2011; Lauszus 2001; Louie 2011; Ma 2015; Moses 2009; Reece 1995), and were thus judged to be at a low risk of selection bias. Methods reported included computer‐generated random numbers (Asemi 2013a; Asemi 2013b; Asemi 2014; Louie 2011), web‐based randomisation (Bo 2014) and random number tables (Garner 1997; Ma 2015; Reece 1995). In Moses 2009, restricted randomisation was used, where group allocation was done by using permuted blocks of unequal size with the list generated using STATA. Although Grant 2011 did not specify the method used for sequence generation, it was considered likely to have been a computer‐generated sequence. Lauszus 2001 used a block‐wise randomisation stratified for pre‐pregnancy weight. In the remaining eight trials (Balas‐Nakash 2010; Cypryk 2007; Jamilian 2015; Magee 1990; Moreno‐Castilla 2013; Rae 2000; Valentini 2012; Wang 2015), insufficient information was provided on random sequence generation, and thus these trials were judged to be at unclear risk of selection bias.

Four trials reported adequate allocation concealment methods, and were judged to be at low risk of selection bias (Bo 2014; Grant 2011; Lauszus 2001; Louie 2011). Methods used for achieving allocation concealment included use of a centralised randomisation service (Bo 2014; Louie 2011), use of consecutive, numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes (Grant 2011) and involvement of a third person from independent centre (Lauszus 2001). Ma 2015 reported allocation concealment was not used, and was thus judged to be at high risk of selection bias. The remainder of the included trials (Asemi 2013a; Asemi 2013b; Asemi 2014; Balas‐Nakash 2010; Cypryk 2007; Garner 1997; Jamilian 2015; Magee 1990; Moreno‐Castilla 2013; Moses 2009; Rae 2000; Reece 1995; Valentini 2012; Wang 2015) did not report clear methods for concealing allocation and thus were judged to be at unclear risk of selection bias.

Blinding

Four trials were judged to be at low risk of performance bias (Asemi 2013a; Asemi 2013b; Louie 2011; Rae 2000). In Asemi 2013a, Asemi 2013b and Louie 2011, while the study dietitians were not blinded, women and all other research personnel were reported to be blinded, and thus the risk of performance bias was judged to be low. Rae 2000 reported that the women and diabetes service staff were blinded.

Thirteen trials were considered to be at high risk of performance bias due to lack of blinding of women (Balas‐Nakash 2010; Bo 2014; Cypryk 2007; Garner 1997; Grant 2011; Jamilian 2015; Lauszus 2001; Ma 2015; Moreno‐Castilla 2013; Moses 2009; Reece 1995; Valentini 2012; Wang 2015), and two trials were judged to be at unclear risk of performance bias (Asemi 2014; Magee 1990).

Two trials reported that outcome assessors were blinded (Asemi 2013a; Bo 2014), and were thus judged to be at low risk of detection bias. In one trial, an un‐blinded research dietitian was responsible for outcome data collection, and was thus judged to be at high risk of detection bias (Louie 2011). No information was available on whether outcome assessors were blinded in the remaining 16 trials (Asemi 2013b; Asemi 2014; Balas‐Nakash 2010; Cypryk 2007; Garner 1997; Grant 2011; Jamilian 2015; Lauszus 2001; Ma 2015; Magee 1990; Moreno‐Castilla 2013; Moses 2009; Rae 2000; Reece 1995; Valentini 2012; Wang 2015).

Incomplete outcome data

Fourteen included trials were judged as being at low risk of attrition bias (Asemi 2013a; Asemi 2013b; Asemi 2014; Bo 2014; Cypryk 2007; Garner 1997; Grant 2011; Jamilian 2015; Lauszus 2001; Magee 1990; Moses 2009; Rae 2000; Valentini 2012; Wang 2015).

There were no losses to follow‐up or post‐randomisation exclusions in seven trials (Bo 2014; Cypryk 2007; Magee 1990; Moses 2009; Valentini 2012; Wang 2015). In the remaining trials, there were low proportions of women lost to follow‐up or excluded post‐randomisation, and/or similar reasons for loss to follow‐up or exclusion between groups (Asemi 2013a; Asemi 2013b; Asemi 2014; Garner 1997; Grant 2011; Jamilian 2015; Lauszus 2001; Rae 2000).

Two trials were judged to be at high risk of attrition bias (Balas‐Nakash 2010; Louie 2011). In Louie 2011, small numbers of women were lost to follow‐up or were withdrawn post‐randomisation; however, by three months postpartum, outcome data were only reported for only 58 (58.5%) of the randomised women and babies. In Balas‐Nakash 2010, it was reported that a randomised cohort of 108 women who were potentially eligible, 20 declined to participate (15.8%) and a further 19 women (17.5%) were excluded due to incomplete dietary information (leaving 69 women); no information was available on the characteristics of these women (Balas‐Nakash 2010).