Abstract

Background

Evidence on the benefits of admission tests other than cardiotocography in preventing adverse perinatal outcomes has not been established.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of admission tests other than cardiotocography in preventing adverse perinatal outcomes.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (31 March 2011).

Selection criteria

Randomised (individual and cluster) controlled trials, comparing labour admission tests other than CTG for the prevention of adverse perinatal outcomes.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed eligibility, quality and extracted data.

Main results

We included one study involving 883 women.

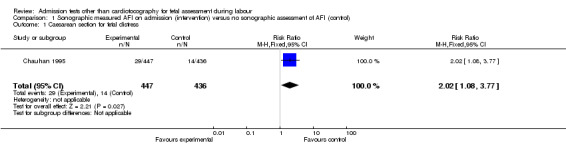

Comparison of sonographic assessment of amniotic fluid index (AFI) on admission versus no sonographic assessment of AFI on admission. The incidence of cesarean section for fetal distress in the intervention group (29 of 447) was significantly higher than those of controls (14 of 436) (risk ratio (RR) 2.02; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.08 to 3.77).

The incidence of Apgar score less than seven at five minutes in the intervention group (10 of 447) was not significantly different from controls (seven of 436) (RR 1.39, 95% CI 0.54 to 3.63).

The incidence of artificial oxytocin for augmentation of labour in the intervention group (213 of 447) was significantly higher than controls (132 of 436) (RR 1.57; 95% CI 1.32 to 1.87).

The incidence of neonatal NICU admission in the intervention group (35 of 447) was not significantly different from the controls (33 of 436) (RR 1.03; 95% CI 0.66 to 1.63)

Authors' conclusions

There is not enough evidence to support the use of admission tests other than cardiotocography for fetal assessment during labour. Appropriate randomised controlled trials with adequate sample size of admission tests other than cardiotocography for fetal assessment during labour are required.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Amniotic Fluid; Amniotic Fluid/diagnostic imaging; Labor, Obstetric; Cardiotocography; Cesarean Section; Cesarean Section/statistics & numerical data; Fetal Distress; Fetal Distress/diagnosis; Fetal Monitoring; Fetal Monitoring/methods; Heart Rate, Fetal; Heart Rate, Fetal/physiology; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Ultrasonography

Plain language summary

Admission tests other than cardiotocography for fetal assessment during labour

About four million out of 120 million infants have birth asphyxia each year. Almost a million of these newborns are not successfully resuscitated. Changes in fetal heart rate precede brain injury and can be monitored. Applying some tests to women who are admitted to hospital for labour may help to identify fetal distress and allow timely and effective intervention such as caesarian delivery to prevent poor newborn outcomes. A fetal admission test may consist of monitoring the fetal heart for 20 minutes using a Doppler ultrasound transducer on the mother's abdomen (cardiotocography), uterine contractions, sound‐provoked fetal movement, fetal breathing and estimation of amniotic fluid volume observed using real‐time ultrasonography.

This review identified one randomised controlled study (involving 883 women) at 26 to 42 weeks' gestation and in early labour who were admitted to a tertiary hospital in USA (between July 1992 and January 1993). Measuring the amount of amniotic fluid when women were admitted did not improve infant outcomes but increased/doubled the caesarean section rate for fetal distress. The use of artificial oxytocin for augmentation of labour was also higher in the group of women who received the test than for those that did not. Because of the limited evidence (one study with a small sample size), we cannot make a meaningful conclusion or recommendations. More studies are needed.

Background

Description of the condition

According to World Health Organization estimates, around 3% of approximately 120 million infants born every year in developing countries develop birth asphyxia requiring resuscitation. It is estimated that some 900,000 of these newborns die each year (Costello 1994; WHO 1997).

The goal of intrapartum fetal surveillance is to detect potential fetal decompensation and to allow timely and effective intervention to prevent perinatal morbidity or mortality such as perinatal asphyxia, neonatal hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy, stillbirth and neonatal death (Liston 2007). The fetal brain is the primary organ of interest, but at present it is not clinically feasible to assess its function during labour. However, fetal heart (FH) rate characteristics can be assessed, and changes in FH rate that precede brain injury constitute the rationale for FH monitoring: that is, timely response to abnormal FH patterns might be effective in preventing brain injury (Liston 2007).

Description of the intervention

The fetal admission test is a means to identify women who may require caesarean delivery for a non‐reassuring FH rate tracing during labour, thus avoiding delivery of a depressed newborn (Ingemarsson 1986). Cardiotocography (CTG) for 20 minutes (Ingemarsson 1986), response to vibroacoustic stimulation (Sarno 1990), biophysical profile (Kim 2003), modified biophysical profile (MBPP) (Lalor 2008), rapid biophysical profile (rBPP, the combination of amniotic fluid index and sound‐provoked fetal movement detected by ultrasound in predicting intrapartum fetal distress) (Tongprasert 2006; Tongsong 1999), Doppler scans of the umbilical artery (Malcus 1991; Mires 2001), and sonographic assessment of amniotic fluid (Moses 2004; Sarno 1989) are diagnostic modalities that have been used for the assessment of fetal well‐being on admission.

Vibroacoustic stimulation

Fetal vibroacoustic stimulation is a simple, non‐invasive technique where a device is placed on the maternal abdomen over the region of the fetal head and sound is emitted at a predetermined level for several seconds (East 2005).

Biophysical profile

The BPP combines the assessment of electronic FH rate monitoring (CTG) with four biophysical features, namely (i) fetal movements, (ii) fetal tone, (iii) fetal breathing and (iv) estimation of amniotic fluid volume. These latter four variables are observed using real‐time ultrasonography. The FH rate is recorded, usually over a 20‐minute period, and is achieved by using a Doppler ultrasound transducer to monitor the FH through the mother's abdomen. Uterine contractions are monitored simultaneously by a pressure transducer on the mother's abdomen. Both transducers are linked to a monitor and this results in a paper trace known as a CTG.

The BPP is performed in an effort to identify babies that may be at risk of poor pregnancy outcome, so that additional assessments of well‐being may be performed, labour may be induced, or a caesarean section performed to expedite birth (Lalor 2008; Manning 1980).

The modified biophysical profile (MBPP)

A modified version of the BPP, known as the MBPP, consists of: (i) recording an antenatal CTG (with or without vibroacoustic stimulation) combined with (ii) ultrasound measurement of the amniotic fluid. The MBPP is employed as a first‐line screening test (Archibong 1999) and should be followed by the complete BPP as a back‐up test when indicated (Lalor 2008).

The rapid biophysical profile (rBPP)

The rapid biophysical profile (rBPP) is the combination of amniotic fluid index and sound‐provoked fetal movement detected by ultrasound. The rBPP is an effective predictor of intrapartum fetal distress in high‐risk pregnancies (Tongprasert 2006).

Doppler scans of the umbilical artery

Doppler ultrasound study of umbilical artery waveforms helps identify the compromised fetus in 'high‐risk' pregnancies. Doppler ultrasound detects changes in the pattern of blood flow through the fetal circulation. It may be that problems for the fetus could be identified through these changes. Interventions such as early delivery might then be able to reduce the mortality and morbidity (Alfirevic 2009).

Sonographic assessment of amniotic fluid

Amniotic fluid volume is an important parameter in the assessment of fetal well‐being. Oligohydramnios occurs in many high‐risk conditions and is associated with poor perinatal outcomes (Nabhan 2008).

Cardiotocograph (CTG)

A systematic review was conducted to assess the effectiveness of admission FH tracings in preventing adverse outcomes, compared with auscultation only, and to assess the test’s prognostic value in predicting adverse outcomes (Alfirevic 2006). Three randomised controlled trials (RCTs) including 11,259 women and 11 observational studies including 5831 women were reviewed. Meta‐analyses of the controlled trials found that women randomised to the labour admission test were more likely to have minor obstetric interventions such as epidural analgesia (risk ratio (RR) 1.2; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.1 to 1.4), continuous electronic fetal monitoring (RR 1.3; 95% CI 1.2 to 1.5) and fetal blood sampling (RR 1.3; 95% CI 1.1 to 1.5) compared with women randomised to auscultation on admission. There were no significant differences in any of the other outcomes. From the observational studies, prognostic value for various outcomes was found to be generally poor. There is no evidence to support the hypothesis that the labour admission test is beneficial in women with no risk factors for adverse perinatal outcome (Blix 2005).

Continuous cardiotocography during labour was associated with a reduction in neonatal seizures, but no significant differences in cerebral palsy, infant mortality or other standard measures of neonatal well‐being. However, continuous cardiotocography was associated with an increase in caesarean sections and instrumental vaginal births (Alfirevic 2006).

There is a separate Cochrane protocol on the effectiveness of cardiotocography versus intermittent auscultation of FH on admission to labour ward for assessment of fetal well‐being (Devane 2010).

How the intervention might work

Ideally, these tests would identify the fetus at risk for decompensation during labour. This could allow timely and effective interventions to prevent perinatal morbidity or mortality.

These interventions might have different effects in high‐risk versus low‐risk pregnancy, preterm versus term versus post‐term.

We plan to conduct subgroup analyses based on these two variables.

Why it is important to do this review

At present, there is no evidence about the effectiveness of labour admission tests other than cardiotocography. Hence, it is important to systematically review the evidence on the effectiveness of labour admission tests other than cardiotocography, such as BPP, Doppler, MBPP, rBPP, sonographic assessment of amniotic fluid, in preventing adverse perinatal outcomes.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of admission tests other than cardiotocography in preventing adverse perinatal outcomes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Any RCTs (individual and cluster) comparing other labour admission tests in preventing adverse perinatal outcomes. We excluded quasi‐random study designs, trials using crossover design and reports that were only available as abstracts.

Types of participants

All women at admission to labour room, both primigravidae and multigravidae. We sought trials of both low and high obstetric risk groups.

Types of interventions

Labour admission tests including vibroacoustic stimulation, biophysical profile (BPP), modified BPP, rapid BPP, Doppler scans of the umbilical artery, and sonographic assessment of amniotic fluid.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Mother

Incidence of caesarean section

Incidence of cesarean section rate for fetal distress

Incidence of operative vaginal delivery

Incidence of serious maternal complications (e.g. admission to intensive care unit, septicaemia (a form of blood infection, organ failure))

Infant

Birth asphyxia

Stillbirths

Early neonatal death

Secondary outcomes

Incidence of continuous electronic fetal monitoring during labour

Incidence of artificial rupture of membranes during labour

Incidence of artificial oxytocin for augmentation of labour

Mobility during labour

Perceived control and/or self‐confidence during labour

Incidence of use of pharmacological analgesia during labour and birth (including epidural)

Incidence of use of non‐pharmacological methods of coping with labour, e.g. transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, hydrotherapy

Satisfaction with labour experience

Incidence of fetal blood sampling

Apgar score less than seven at five minutes

Incidence of neonatal NICU admission

Length of hospital stay (maternal and neonatal)

Neonatal neurodevelopment

Breastfeeding

Maternal and neonatal infection

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (31 March 2011).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

weekly searches of EMBASE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors, Suthit Khunpradit (SK) and Pisake Lumbiganon (PL), assessed independently all the potential studies we identified for inclusion as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion.

If information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

SK and PL independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreement through discussion with the third review author, Malinee Laopaiboon (ML).

(1) Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for the included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number) or;

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for the included study the method used to conceal the allocation sequence and determine whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3) Blinding (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for the included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding could not have affected the results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for outcome assessors.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

We described for the included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We have stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or was supplied by the trial authors, we have re‐included missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomization);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting bias

We described for the included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other sources of bias

We described for the included study any important concerns we have about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed whether the study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low risk of other bias;

high risk of other bias;

unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgments about whether the one included study is at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it was likely to impact on the findings. In future updates, as more data becomes available, we will explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we present results as summary RR with 95% CIs. This review only included dichotomous data from one study. Measures to be used in future updates of this review for continuous and ordinal data are listed below.

Continuous data

For continuous data, such as length of hospital stay, etc., we will use the mean difference if outcomes are measured in the same way between trials. We will use the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measure the same outcome, but use different methods.

Ordinal data

For ordinal data, we will use median and interquartile range.

We will compare:

one intervention versus no intervention;

one intervention versus another intervention.

Unit of analysis issues

For multiple pregnancies, we account for dependency of data for the outcomes of the infants who have the same mother in the analysis.

Cluster‐randomised trials

We did not identify any cluster‐RCTs for inclusion in this review. In future updates, if we identify any cluster‐RCTs we will include them in the analyses along with individually randomised trials. We will adjust their sample sizes using the methods described in the Handbook (Higgins 2011) using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Dealing with missing data

For the one included study, we noted levels of attrition.

In future updates, as more data become available, we will explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis. For all outcomes, we will carry out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we will attempt to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and all participants will be analysed in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each trial will be the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes are known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

In subsequent updates, if more data become available, we will assess statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the T², I² and Chi² statistics. We will regard heterogeneity as substantial if T² is greater than zero and either I² is greater than 30% or there is a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

When there are 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis we will investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually, and use formal tests for funnel plot asymmetry. For continuous outcomes we will use the test proposed by Egger 1997, and for dichotomous outcomes we will use the test proposed by Harbord 2006. If we detect asymmetry in any of these tests or by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We will carry out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2008).

In future updates, if more studies are included, we will use fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it is reasonable to assume that studies are estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials are examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods are judged sufficiently similar. If there is clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differ between trials, or if we detect substantial statistical heterogeneity, we will use random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary if an average treatment effect across trials is considered clinically meaningful. We will treat the random‐effects summary as the average range of possible treatment effects and we will discuss the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect is not clinically meaningful we will not combine trials.

If we use random‐effects analyses, we will present the results as the average treatment effect with its 95% CI, and the estimates of T² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In future updates, if we identify substantial heterogeneity, we will investigate it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We will consider whether an overall summary is meaningful, and if it is, use random‐effects analysis to produce it.

We plan to carry out the following subgroup analyses in subsequent updates of this review:

high‐risk versus low‐risk pregnancy;

term versus preterm, term versus post‐term.

We will restrict subgroup analyses to the primary outcomes.

For fixed‐effect inverse variance meta‐analyses we will assess differences between subgroups by interaction tests. For random‐effects and fixed‐effect meta‐analyses using methods other than inverse variance, we will assess differences between subgroups by inspection of the subgroups’ confidence intervals; non‐overlapping confidence intervals indicate a statistically significant difference in treatment effect between the subgroups.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not carry out any sensitivity analyses, as only one study was included. However, in future updates of this review, we plan to carry out sensitivity analysis to explore the effect of study quality. This will involve analyses based on the trial quality ratings for sequence generation, allocation concealment and incomplete outcome data. We will exclude studies of poor quality in the analysis (those categorised as 'high risk of bias' or 'unclear risk of bias') in order to assess for any substantive difference to the overall result.

Results

Description of studies

SeeCharacteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

The search strategy identified two potentially relevant studies. We included one study and excluded one study.

Included studies

We only included one RCT in this review (Chauhan 1995). The trial was undertaken in a tertiary hospital in Mississippi, USA between July 1992 and January 1993, and evaluated the effects of measured quantitative four‐quadrant amniotic fluid index (AFI) at admission on perinatal outcomes as shown in the Characteristics of included studies table.

This study randomised 883 pregnant women in early labour admitted for delivery to receive a quantitative four‐quadrant AFI on admission (447 women) or the control group (no sonographic assessment of AFI) (436 women).

For the intervention group, the AFI was measured as described by Phelan 1987 and clinically designated as oligohydramnios if it was equal to or less than 5.0 cm, or as normal if it was greater than 5.0 cm.

For the control group, no formal measurement of AF volume was performed.

Pregnant women at 26 to 42 weeks' gestation and in early labour (cervical dilatation 5 cm or less), vertex presentation, and no known fetal structural anomalies were eligible. Exclusion criteria included abnormal fetal heart rate tracing on admission, and vaginal bleeding.

For more information, seeCharacteristics of included studies.

Excluded studies

Based on the criteria listed in the methods section, we excluded one trial (Phelan 1989) which was only available as an abstract. The full study findings have not been published after we attempted to contact authors of the original report (seeCharacteristics of excluded studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the one included trial as having ’low risk of bias’ in most domains of risk of bias: sequence generation; allocation concealment; incomplete outcome data; and free other risk of bias.

See details inRisk of bias in included studiestable.

Effects of interventions

Sonographic assessment of amniotic fluid versus no sonographic assessment of amniotic fluid

One trial Chauhan 1995 involving 883 women (447 in the intervention group and 436 in the control group) evaluated the effects of quantitatively measured four‐quadrant AFI at admission on clinical outcomes.

Primary outcomes

Mother

The incidence of caesarean section for fetal distress in the intervention group (29 of 447) was significantly higher than those of controls (14 of 436) (RR 2.02; 95% CI 1.08 to 3.77; Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Sonographic measured AFI on admission (intervention) versus no sonographic assessment of AFI (control), Outcome 1 Caesarean section for fetal distress.

Infant

The incidence of Apgar score less than seven at five minutes in the intervention group (10 of 447) was not significantly different from controls (7 of 436) (RR 1.39, 95% CI 0.54 to 3.63; Analysis 1.2 )

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Sonographic measured AFI on admission (intervention) versus no sonographic assessment of AFI (control), Outcome 2 Apgar score < 7 at 5 min.

Secondary outcomes

The incidence of administering artificial oxytocin for augmentation of labour was significantly higher in the intervention group (213 of 447) than in the control group (132 of 436) (RR 1.57; 95% CI 1.32 to 1.87; Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Sonographic measured AFI on admission (intervention) versus no sonographic assessment of AFI (control), Outcome 3 Oxytocin administration.

The incidence of neonatal NICU admission in the intervention group (35 of 447) was not significantly different from the controls (33 of 436) (RR 1.03; 95% CI 0.66 to 1.63; Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Sonographic measured AFI on admission (intervention) versus no sonographic assessment of AFI (control), Outcome 4 Neonatal admission to NICU.

Discussion

Summary of main results

One trial involving 883 women evaluated the measurement of amniotic fluid index at admission. The incidence of augmentation of labour and cesarean section for fetal distress in the intervention group was significantly higher than those of controls, without any improvement in perinatal outcomes. This review's findings should be cautiously interpreted because it was concluded from only one study.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

There was only one study conducted in a university hospital in the US.

Quality of the evidence

The one included study was of reasonably good quality with low risk of bias. However, the sample size was rather limited to have any meaningful conclusion especially for rare outcomes.

Potential biases in the review process

We followed the review process recommended by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Review Group strictly, including a rigorous trial search strategy. The review authors have no known conflict of interest on the results of the review, which should help to minimise any biases in the review process.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The results of this review agree with a non‐RCT study (Chauhan 1994); patients who had the AFI measured as fetal admission test had significantly higher risk of caesarean section for suspected fetal distress and high incidence of oxytocin for augmentation of labour than the parturient who did not have AFI measurement in early labour. The incidences of Apgar scores less than seven at one and five minutes were not significantly different from controls.These findings, although from only one RCT and one non‐ RCT, raise concern about the possible adverse effects of this intervention. One possible explanation is the high false positive rate, leading to unnecessary interventions.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is not enough evidence to support the use of admission tests other than cardiotocography for fetal assessment during labour.

Implications for research.

Appropriate RCTs of admission tests other than cardiotocography for fetal assessment during labour are required.

Acknowledgements

As part of the pre‐publication editorial process, this review has been commented on by three peers (an editor and two referees who are external to the editorial team), a member of the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's international panel of consumers and the Group's Statistical Adviser.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Sonographic measured AFI on admission (intervention) versus no sonographic assessment of AFI (control).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Caesarean section for fetal distress | 1 | 883 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.02 [1.08, 3.77] |

| 2 Apgar score < 7 at 5 min | 1 | 883 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.39 [0.54, 3.63] |

| 3 Oxytocin administration | 1 | 883 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.57 [1.32, 1.87] |

| 4 Neonatal admission to NICU | 1 | 883 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.66, 1.63] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Chauhan 1995.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial, random assignment by opening an opaque, sealed envelope, which contained a computer‐generated randomisation sequence. | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria were parturients at 26 to 42 weeks' gestation and in early labour (cervical dilatation 5 cm or less), vertex presentation, and no known fetal structural anomalies. Exclusion criteria included abnormal fetal heart rate tracing on admission, vaginal bleeding, and gestation age less than 26 weeks. Parturients at 26‐42 weeks' gestation and in early labour were randomised to the study (measured AFI on admission) or a control group (no sonographic assessment of AF volume). A total of 883 women participated with 447 in the study group and 436 in the control group. |

|

| Interventions | Measurement of AFI on admission versus a control group (no sonographic assessment of AF volume). | |

| Outcomes | Oxytocin administration, prelabour rupture of membranes, meconium‐stained liquor, abdominal delivery, cephalopelvic disproportion, suspected fetal distress, birthweight, Apgar score < 7 at 1 and 5 minutes, and NICU admission. | |

| Notes | This study was conducted in the USA. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer random number generator. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sealed opaque envelopes. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not feasible to blind participants and clinicians. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Outcomes were able to be measured in all 883 women. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | We do not have the protocol to compare. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other obvious biases. |

AF: amniotic fluid AFI: amniotic fluid index NICU: neonatal intensive care unit

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Phelan 1989 | Based on the criteria listed in the methods section. Only abstract was available. The full study findings have not been published after we attempted to contact authors of the original report . |

Differences between protocol and review

We have added outcomes of cesarean section rate for fetal distress and incidence of neonatal NICU admission to the type of outcomes, because they are relevant to our review objective.

Contributions of authors

Suthit Khunpradit (SK) initiated the review question that was approved by Pisake Lumbiganon (PL) and Malinee Laopaiboon (ML). SK and PL independently assessed potential studies, extracted data and evaluated risk of bias. SK drafted the review which was revised critically by PL and ML. All review authors approved the final version of the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Lamphun Hospital, Thailand.

Khon Kaen University, Thailand.

External sources

Thai Cochrane Network, Thailand.

Thailand Research Fund(Senior Research Scholar Program), Thailand.

Declarations of interest

None known.

New

References

References to studies included in this review

Chauhan 1995 {published data only}

- Chauhan SP, Magann EF, Washburne JF, Perry KG, Martin JN, Morrison JC. Prospective, randomized assessment of amniotic fluid index as a fetal admission test. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1994;170:392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan SP, Washburne JF, Magann EF, Perry KG, Martin JN, Morrison JC. A randomized study to assess the efficacy of the amniotic fluid index as a fetal admission test. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1995;86:9‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Phelan 1989 {published data only}

- Phelan JP, Sarno AP, Ahn MO. The fetal admission test. Proceedings of 37th Annual Clinical Meeting of American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 1989 May 22‐25; Atlanta, Georgia, USA. 1989:4.

Additional references

Alfirevic 2006

- Alfirevic Z, Devane D, Gyte GML. Continuous cardiotocography (CTG) as a form of electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) for fetal assessment during labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006066] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Alfirevic 2009

- Alfirevic Z, Stampalija T, Gyte GML. Fetal and umbilical Doppler ultrasound in high‐risk pregnancies. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007529] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Archibong 1999

- Archibong EI. Biophysical profile score in late pregnancy and timing of delivery. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 1999;64(2):129‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Blix 2005

- Blix E, Reiner LM, Klovning A, Oian P. Prognostic value of the labour admission test and its effectiveness compared with auscultation only: a systematic review. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2005;112:1595‐604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chauhan 1994

- Chauhan SP, Magann EF, Sullivan CA, Lutton PM, Bailey K, Morrison JC. Amniotic fluid index as an admission test may increase the incidence of cesarean section in a community hospital. Journal of Maternal‐Fetal Investigation 1994;4:223‐6. [Google Scholar]

Costello 1994

- Costello AM, Manandhar DS. Perinatal asphyxia in less developed countries. Archives of Disease in Childhood. Fetal and Neonatal Edition 1994;71(1):F1‐F3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Devane 2010

- Devane D, Lalor JG, Daly S, McGuire W. Cardiotocography versus intermittent auscultation of fetal heart on admission to labour ward for assessment of fetal wellbeing. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 8. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005122.pub3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

East 2005

- East CE, Smyth RMD, Leader LR, Henshall NE, Colditz PB, Tan KH. Vibroacoustic stimulation for fetal assessment in labour in the presence of a nonreassuring fetal heart rate trace. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004664.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Egger 1997

- Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta‐analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629‐34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Harbord 2006

- Harbord RM, Egger M, Sterne JA. A modified test for small‐study effects in meta‐analyses of controlled trials with binary endpoints. Statistics in Medicine 2006;25:3443‐57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Ingemarsson 1986

- Ingemarsson I, Arulkumaran S, Ingemarsson E, Tambyraja RL, Ratnam SS. Admission test: a screening test for fetal distress in labor. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1986;68:800‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kim 2003

- Kim SY, Khandelwal M, Gaughan JP, Agar MH, Reece EA. Is the intrapartum biophysical profile useful?. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2003;102:471‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lalor 2008

- Lalor JG, Fawole B, Alfirevic Z, Devane D. Biophysical profile for fetal assessment in high risk pregnancies. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000038.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Liston 2007

- Liston R, Sawchuck D, Young D, Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecologists of Canada, British Columbia Perinatal Health Program. Fetal health surveillance: antepartum and intrapartum consensus guideline. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada 2007;29(9 Suppl 4):S3‐S56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Malcus 1991

- Malcus P, Gudmundsson S, Marsal K, Kwok HH, Vengadasalam D, Ratnam SS. Umbilical artery doppler velocimetry as a labor admission test. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1991;77:10‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Manning 1980

- Manning FA, Platt LD, Sipos L. Antepartum fetal evaluation: development of a new biophysical profile. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1980;136:787‐95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mires 2001

- Mires G, Williams F, Howie P. Randomised controlled trial of cardiotocography versus doppler auscultation of fetal heart at admission in labour in low risk obstetric population. BMJ 2001;322:1457‐62 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moses 2004

- Moses J, Doherty DA, Magann EF, Chauhan SP, Morrison JC. A randomized clinical trial of the intrapartum assessment of amniotic fluid volume: amniotic fluid index versus the single deepest pocket technique. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2004;190:1564‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nabhan 2008

- Nabhan AF, Abdelmoula YA. Amniotic fluid index versus single deepest vertical pocket as a screening test for preventing adverse pregnancy outcome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006593.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Phelan 1987

- Phelan JP, Ahn MO, Smith CV, Rutherford SE, Morrison JC. Amniotic fluid index and adverse outcome. Journal of Reproductive Medicine 1987;32:601‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2008 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.0. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008.

Sarno 1989

- Sarno AP, Ahn MO, Brar HS, Phelan JP, Platt LD. Intrapartum doppler velocimetry, amniotic fluid volume, and fetal heart rate as predictors of subsequent fetal distress: an initial report. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1989;161:1508‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sarno 1990

- Sarno AP, Ahn MO, Phelan JP, Paul RH. Fetal acoustic stimulation in the early intrapartum period as a predictor of subsequent fetal condition. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1990;162:762‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tongprasert 2006

- Tongprasert F, Jinpala S, Srisupandit K, Tongsong T. The rapid biophysical profile for early intrapartum fetal well‐being assessment. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2006;95:14‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tongsong 1999

- Tongsong T, Piyamongkol W, Anantachote A, Pulphutapong K. The rapid biophysical profile for assessment of fetal well‐being. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research 1999;25:431‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

WHO 1997

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report 1995. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1997. [Google Scholar]