Abstract

Background

Amniotic fluid volume is an important parameter in the assessment of fetal well‐being. Oligohydramnios occurs in many high‐risk conditions and is associated with poor perinatal outcomes. Many caregivers practice planned delivery by induction of labor or caesarean section after diagnosis of decreased amniotic fluid volume at term. There is no clear consensus on the best method to assess amniotic fluid adequacy.

Objectives

To compare the use of the amniotic fluid index with the single deepest vertical pocket measurement as a screening tool for decreased amniotic fluid volume in preventing adverse pregnancy outcome.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (January 2009), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2008, Issue 4), MEDLINE (1966 to January 2008) and the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (December 2008). We handsearched the citation lists of relevant publications, review articles, and included studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials involving women with a singleton pregnancy, whether at low or high risk, undergoing ultrasound measurement of amniotic fluid volume as part of antepartum assessment of fetal well‐being that compared the amniotic fluid index and the single deepest vertical pocket measurement.

Data collection and analysis

Both authors independently assessed eligibility and quality, and extracted the data.

Main results

Five trials (3226 women) met the inclusion criteria. There is no evidence that one method is superior to the other in the prevention of poor peripartum outcomes, including: admission to a neonatal intensive care unit (Risk Ratio (RR) 1.04; 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) 0.85 to 1.26); an umbilical artery pH of less than 7.1; the presence of meconium; an Apgar score of less than 7 at five minutes; or caesarean delivery. When the amniotic fluid index was used, significantly more cases of oligohydramnios were diagnosed (RR 2.39, 95% CI 1.73 to 3.28), and more women had inductions of labor (RR 1.92; 95% CI 1.50 to 2.46) and caesarean delivery for fetal distress (RR 1.46; 95% CI 1.08 to 1.96)

Authors' conclusions

The single deepest vertical pocket measurement in the assessment of amniotic fluid volume during fetal surveillance seems a better choice since the use of the amniotic fluid index increases the rate of diagnosis of oligohydramnios and the rate of induction of labor without improvement in peripartum outcomes. A systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of both methods in detecting decreased amniotic fluid volume is required.

Keywords: Female, Humans, Pregnancy, Pregnancy Outcome, Amniotic Fluid, Amniotic Fluid/diagnostic imaging, Amniotic Fluid/physiology, Oligohydramnios, Oligohydramnios/diagnosis, Ultrasonography

Plain language summary

Amniotic fluid index compared with single deepest vertical pocket measurement in predicting an adverse pregnancy outcome

Amniotic fluid provides a supportive and protective environment for fetal development during pregnancy. A decreased amniotic fluid volume (oligohydramnios) can occur because of fetal anomalies, intrauterine growth restriction, pre‐eclampsia or prolonged (post‐term) pregnancy. Many caregivers practice planned delivery by induction of labor or caesarean section after diagnosis of decreased amniotic fluid volume at term, to prevent an adverse pregnancy outcome. Ultrasonography is non‐invasive and is used widely for the follow up of pregnancy. It can be used to determine amniotic fluid volume by measuring either the amniotic fluid index or single deepest vertical pocket.

This review demonstrated that using the amniotic fluid index increased the number of pregnant women who were diagnosed with oligohydramnios and induced for an abnormal fluid volume when compared with the deepest vertical pocket measure. The women also had a higher rate of caesarean section for so‐called fetal distress. Yet the rate of admission to neonatal intensive care units and the occurrence of neonatal acidosis, an objective assessment of fetal well‐being, were similar between the two groups. The other measured perinatal outcomes that were no different were a non‐reassuring fetal heart rate tracing, the presence of meconium, or an Apgar score of less than 7 at five minutes. These conclusions were from five randomized controlled trials involving 3226 women with singleton pregnancies, reported on between 1997 and 2004.

The accurate assessment of amniotic fluid volume by ultrasonography can be influenced by an inexperienced operator, fetal position, the probability of a transient change, and the different ultrasound diagnostic criteria of an abnormal volume.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. AFI vs SDVP: summary of findings table.

| Amniotic fluid index compared to Single deepest vertical pocket for pregnant women to prevent adverse pregnancy outcome | ||||||

|

Patient or population: pregnant women to prevent adverse pregnancy outcome Settings: Inpatient Intervention: Amniotic fluid index Comparison: Single deepest vertical pocket | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Single deepest vertical pocket | Amniotic fluid index | |||||

| Admission to neonatal intensive care unit | Low risk population1 | RR 1.04 (0.85 to 1.26) | 3226 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2,3 | ||

| 48 per 1000 | 50 per 1000 (41 to 60) | |||||

| High risk population1 | ||||||

| 349 per 1000 | 363 per 1000 (297 to 440) | |||||

| Perinatal deaths | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | Only 3 trials of the included 5 trials reported this critical outcome measure. No cases of perinatal deaths occurred in the 3 trials including 1689 women |

| Umbilical artery pH less than 7.1 | Low risk population1 | RR 1.1 (0.74 to 1.65) | 2625 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2,3 | ||

| 31 per 1000 | 34 per 1000 (23 to 51) | |||||

| High risk population1 | ||||||

| 38 per 1000 | 42 per 1000 (28 to 63) | |||||

| Rate of diagnosis of oligohydramnios | Low risk population1 | RR 2.39 (1.73 to 3.28) | 3226 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | ||

| 24 per 1000 | 57 per 1000 (42 to 79) | |||||

| High risk population1 | ||||||

| 174 per 1000 | 416 per 1000 (301 to 571) | |||||

| Caesarean delivery | Low risk population1 | RR 1.09 (0.92 to 1.29) | 3226 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | ||

| 66 per 1000 | 72 per 1000 (61 to 85) | |||||

| High risk population1 | ||||||

| 277 per 1000 | 302 per 1000 (255 to 357) | |||||

| Rate of induction of labor | Low risk population1 | RR 1.92 (1.5 to 2.46) | 2138 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | ||

| 12 per 1000 | 23 per 1000 (18 to 30) | |||||

| High risk population1 | ||||||

| 302 per 1000 | 580 per 1000 (453 to 743) | |||||

| Caesarean delivery for fetal distress | Low risk population1 | RR 1.46 (1.08 to 1.96) | 3226 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | ||

| 25 per 1000 | 37 per 1000 (27 to 49) | |||||

| High risk population1 | ||||||

| 68 per 1000 | 99 per 1000 (73 to 133) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Low and High risk represent risks in control groups of included studies.

2 Amniotic fluid volume is an indirect measure of outcome.

3 Confidence intervals include no difference.

4 There is unexplained significant heterogeneity

Background

Description of the condition

Amniotic fluid provides a supportive environment for fetal development. It protects the fetus from trauma and infection through its dampening and bacteriostatic properties. It allows for fetal movement and thus fosters the development of the fetal musculoskeletal system. It prevents compression of the umbilical cord and placenta and thus protects the fetus from vascular and nutritional compromise. Amniotic fluid is maintained in a dynamic equilibrium; its volume is the sum of fluid (from fetal urine and lung fluid) flowing into and out (to fetal swallowing and intramembranous absorption) of the amniotic space (Ross 2001). Amniotic fluid volume (AFV) is an important parameter in the assessment of fetal well‐being. Oligohydramnios, a decreased AFV, occurs as a result of fetal anomalies, intrauterine growth restriction, prolonged (post‐term) pregnancies, and pre‐eclampsia. Oligohydramnios is associated with increased fetal and neonatal morbidity and mortality (Sherer 2002). Therefore, the prenatal diagnosis of oligohydramnios is important in the management of pregnancy (Sherer 2002).

Description of the intervention

Invasive methods such as indicator dilution techniques are the most accurate measures of AFV, but are impractical for clinical use. Ultrasonography is non‐invasive and hence it is used widely for the follow up of pregnancy. Additionally, it can be performed serially in cases of suspected abnormal AFV (Gramellini 2004). Several methods are used to assess amniotic fluid. The first method is a subjective assessment where the volume is described as average, above average, below average or scant (Goldstein 1988; Gramellini 2004; Williams 1993). However, the experience of the operator is essential for reliable results (Gramellini 2004). Semi‐quantitative estimates of AFV include the measurement of an amniotic fluid pocket (Gramellini 2004; Williams 1993), the amniotic fluid index (AFI) (Gramellini 2004; Williams 1993), and the amniotic fluid distribution (Myles 2002).

The measurement of a single pocket of amniotic fluid varies among studies depending on the criteria used for decreased amniotic fluid. Different techniques include a 1 cm pocket in one plane (Bastide 1986; Hill 1983; Magann 2000; Manning 1981). Another technique is measuring two perpendicular diameters with values of 1 x 1 cm pocket, 2 x 1 cm pocket, and finally 2 x 2 cm pocket used (Magann 2000). It has also been shown that the largest vertical pocket cut‐off value of 2.7 cm does better than the AFI and the 2 cm largest vertical pocket rule in identifying those at risk for adverse peripartum outcome (Fischer 1993). Another cut‐off value for the largest vertical pocket is suggested to be 4 cm (Rogers 1999). The two diameter pocket method is also used (Gramellini 2004; Jaba 2005; Magann 1992), and a value less than 15 cm2 has been used to identify cases of decreased amniotic fluid (Magann 1999a; Magann 2000; Rogers 1999). Also, another technique for assessment of an amniotic fluid pocket is finding the product of the length, width, and depth of the largest amniotic fluid pocket (Hashimoto 1987). In order to calculate the AFI, the operator divides the uterine cavity into four quadrants. In each quadrant, the largest vertical diameter of a fluid pocket (not containing small fetal parts or loops of umbilical cord) is measured. The sum of these four measures provides a single value for the AFI (Phelan 1987). One study has defined the 50th percentile of AFI to be 12.4 in term pregnancy. The authors also defined the 5th, 10th, 90th, and 95th percentiles to be 8.1, 9.0, 13.5, and 14.4 respectively in term pregnancy. The fifth percentile serves as the lower limit of normal AFI for 28 to 42 weeks' gestation (Hinh 2005). Different arbitrary cut‐off values for identifying oligohydramnios have been estimated to be 5 cm (Croom 1992; Magann 1999a; Magann 2003; Seffah 1999) or 8 cm (Garmel 1997; Kawasaki 2002; Peedicayil 1994; Rogers 1999).

Ultrasonographic assessment of amniotic fluid can be viewed as a semi‐quantitative method. Moreover, there is also the question of reliability. Methods of assessing amniotic fluid perform best when identifying normal volumes, but are poor when identifying an abnormal volume (Gramellini 2004). In addition to the differences in the methods used to assess amniotic fluid, other factors play a role in the accurate assessment of amniotic fluid by ultrasonography. These include an inexperienced operator, fetal position, the probability of a transient change in AFV, and the different ultrasound diagnostic criteria of an abnormal AFV (Fok 2006; Sherer 2002). Furthermore, there is no consensus on the method or the cut‐off value that is more accurate in predicting perinatal morbidity and mortality (Magann 2000).

The AFI and the single deepest vertical pocket (SDVP) are the more commonly employed techniques for assessing adequacy of amniotic fluid. According to these two methods, an AFI less than or equal to 5.0 cm, or the absence of a pocket measuring 2 x 1 cm, can diagnose a decreased AFV (Magann 2003). A meta‐analysis has concluded that a decreased AFI is associated with poor perinatal outcomes in terms of an increased caesarean delivery rate performed for fetal distress, a low Apgar score at five minutes, and neonatal acidosis (Chauhan 1999). Therefore, a decreased AFV has been viewed as a sign of potential fetal compromise (Casey 2000; Locatelli 2004). This is particularly the case for high‐risk pregnancies.

Why it is important to do this review

Many caregivers practice planned delivery, either by induction of labor or caesarean delivery, following the diagnosis of a decreased AFV at term. However, there is no clear consensus on the best method to assess amniotic fluid (Magann 2000; Sherer 2002). In other words, there is a lack of a gold standard test to detect decreased AFV. Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have been conducted to compare the two most commonly used methods (i.e. the AFI versus the single deepest vertical pocket) and to determine the best technique to predict adverse pregnancy outcome among women undergoing antenatal testing. Nonetheless, to the best of our knowledge, a systematic review and meta‐analysis of the published RCTs have not been conducted to address this practical issue. Therefore, there is a need for a systematic review and meta‐analysis to compare the use of AFI with the 2 x 1 cm SDVP method in predicting adverse pregnancy outcome.

Objectives

To compare the use of the AFI with the 2 x 1 cm SDVP as a screening tool for decreased AFV for the prevention of adverse perinatal outcomes, such as admission to neonatal intensive care unit and perinatal deaths.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials.

Types of participants

Women with a singleton pregnancy, whether at low or high risk, undergoing tests for assessment of fetal well‐being.

Types of interventions

Ultrasound measurement of AFV. The methods compared were the AFI and the 2 x 1 cm (single deepest vertical) pocket method.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Admission to neonatal intensive care unit

Number of perinatal deaths

Secondary outcomes

Rate of diagnosis of oligohydramnios (as defined by authors of each study)

Umbilical artery pH less than 7.1

Apgar score less than 7 at five minutes

Presence of meconium

Non‐reassuring fetal heart rate tracing

Induction of labor

Assisted vaginal delivery (without specified indication)

Assisted vaginal delivery for fetal distress

Rate of caesarean section

Caesarean delivery for fetal distress

Length of neonatal intensive care unit stay

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (January 2009).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

In addition, we searched CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library 2008, Issue 4), MEDLINE (January 1966 to December 2008) and the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT) (December 2008), using the search strategies detailed in Appendix 1

Searching other resources

We handsearched the citation lists of relevant publications, review articles, and included studies.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Both authors independently reviewed and assessed full text copies of all identified papers. There were no disagreements regarding eligibility for inclusion. The papers selected for the review met the inclusion criteria:

data presented on AFI and the 2 x 1 cm SDVP method for the assessment of AFV;

the total number of women treated was stated.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form on which both authors independently recorded the extracted data. We used the Review Manager software (RevMan 2008) to double enter all the data. When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we contacted the authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the validity of each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). We described the methods used for generation of the randomization sequence in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

(1) Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

adequate (any truly random process e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

inadequate (any non random process e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal the allocation sequence in sufficient detail and determined whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate (e.g. telephone or central randomization; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

inadequate (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear.

(3) Blinding (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. Studies were judged at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judge that the lack of blinding could not have affected the results. Blinding was assessed separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

Blinding of participants (yes/no/unclear);

Blinding of caregiver (yes/no/unclear);

Blinding of outcome assessment (yes/no/unclear).

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We state whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomized participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or was supplied by the trial authors, we re‐included missing data in the analyses we undertook.

We assessed methods as:

adequate (less than 20% loss of participants);

inadequate (20% or more loss of participants);

unclear.

(5) Selective reporting bias

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate (where it is clear that all of the study's prespecified outcomes and all the expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

inadequate (where not all the study's prespecified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear.

Measures of treatment effect

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2008).

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomized trials

In the protocol, we planned to include cluster‐randomized trials in the analyses along with individually randomized trials and to adjust their sample sizes using the methods described in Higgins 2008. However, we did not identify any cluster randomized trials.

Dealing with missing data

We analyzed data on all participants with available data in the group to which they are allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We applied tests of heterogeneity between trials using the I² statistic. I² values of more than 50% imply substantial heterogeneity (Higgins 2008).

Assessment of reporting biases

Where we suspected reporting bias (see selective reporting bias above), we planned to contact study authors asking them to provide missing outcome data.

Data synthesis

We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data in the absence of significant heterogeneity if trials are sufficiently similar. If heterogeneity was found this was investigated followed by random‐effects when appropriate.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not conduct subgroup analyses because none of the included studies assessed the methods of appraising AFV as a routine procedure for all pregnancies.

Sensitivity analysis

Our planned sensitivity analysis to explore the effect of trial quality was not required because none of the included trials had clearly 'inadequate' allocation of concealment.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The comprehensive literature search yielded 10 trials. Both review authors independently assessed the 10 full‐text papers selected according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria indicated above.

Included studies

Five RCTs met the inclusion criteria for this review (Alfirevic 1997; Chauhan 2004; Magann 2004; Moses 2004; Oral 1999). These enrolled 3226 participants. There were 529 (16.4%) participants at a gestation of less than 37 weeks, 1431 (44.4%) at 37 to 40 weeks, and 1266 (39.2%) beyond 40 weeks. For details of the included studies, see the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Excluded studies

Five trials were excluded from the review (see 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table).

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation

Regarding selection bias, included trial reports noted adequate concealment of allocation except the Oral 1999 study in which the method of allocation concealment was unclear. Included trial reports noted adequate sequence generation, except Alfirevic 1997 in which the method of sequence generation was 'unclear'.

Blinding

In one trial (Moses 2004), the caregivers were blinded to the group assignment and the specific measurement; in the others, performance bias (blinding of participants, caregivers, and outcome assessment) was unclear.

Incomplete outcome data

For attrition bias, all trials had a less than 5% participant loss

Selective reporting

None of the 5 included trials (including 3226 pregnant women) reported the length stay in the neonatal intensive care unit. There is no data provided in 2 trials regarding perinatal death (Magann 2004; Moses 2004).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Primary outcome measures

1. Admission to neonatal intensive care unit

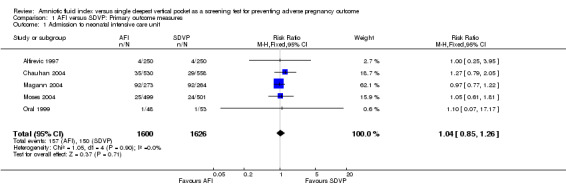

Rate of admission to a neonatal intensive care unit was reported in all five included trials (3226 pregnant women) and there was no evidence of a difference between the two groups (AFI and SDVP measurement) for this outcome (Risk Ratio (RR) 1.04, 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) 0.85 to 1.26, five trials, 3226 newborns) (see Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 AFI versus SDVP: Primary outcome measures, Outcome 1 Admission to neonatal intensive care unit.

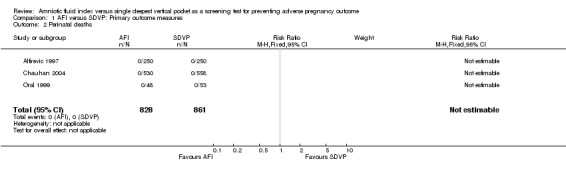

2. Number of perinatal deaths

No perinatal deaths occurred in the three studies that reported this outcome measure (Alfirevic 1997; Chauhan 2004; Oral 1999) (see Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 AFI versus SDVP: Primary outcome measures, Outcome 2 Perinatal deaths.

Secondary outcome measures

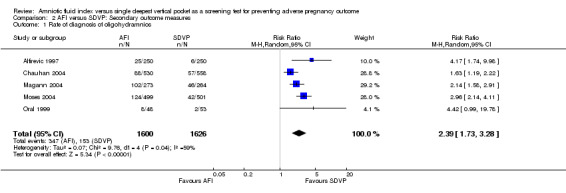

1. Rate of diagnosis of oligohydramnios

The rate of diagnosis of oligohydramnios was higher when the AFI was used for fetal surveillance (RR) 2.39; 95% CI 1.73 to 3.28; five trials, 3226 pregnancies) (see Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 AFI versus SDVP: Secondary outcome measures, Outcome 1 Rate of diagnosis of oligohydramnios.

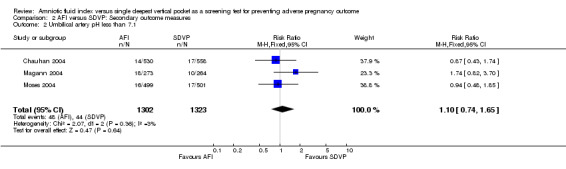

2. Ulbilical artery pH less than 7.1

Umbilical artery pH less than 7.1: no evidence of a difference between the two groups (RR 1.10; 95% CI 0.74 to 1.65; three trials, 2625 newborns) (see Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 AFI versus SDVP: Secondary outcome measures, Outcome 2 Umbilical artery pH less than 7.1.

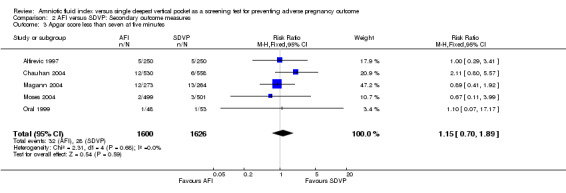

3. Apgar score less than 7 at five minutes

Apgar score of less than 7 at five minutes: no evidence of a difference between the two groups (RR 1.15; 95% CI 0.70 to 1.89; five trials, 3226 newborns) (Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 AFI versus SDVP: Secondary outcome measures, Outcome 3 Apgar score less than seven at five minutes.

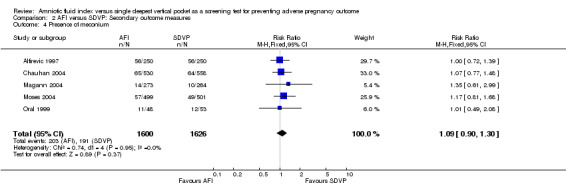

4. Presence of meconium

Presence of meconium: no evidence of a difference between the two groups (RR 1.09; 95% CI 0.90 to 1.30; five trials, 3226 newborns) (see Analysis 2.4).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 AFI versus SDVP: Secondary outcome measures, Outcome 4 Presence of meconium.

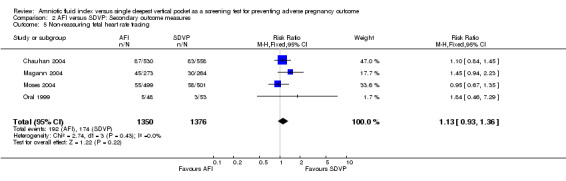

5. Non‐reassuring fetal heart rate tracing

Non‐reassuring fetal heart rate tracing: no evidence of a difference between the two groups (RR 1.13; 95% CI 0.93 to 1.36; four trials, 2726 fetuses) (see Analysis 2.5).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 AFI versus SDVP: Secondary outcome measures, Outcome 5 Non‐reassuring fetal heart rate tracing.

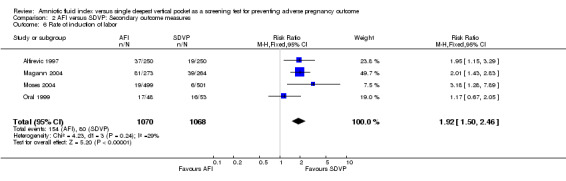

6. Induction of labour

The rate of induction of labor was higher when AFI was used for fetal surveillance (RR 1.92; 95% CI 1.50 to 2.46; four trials, 2138 pregnancies) (see Analysis 2.6).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 AFI versus SDVP: Secondary outcome measures, Outcome 6 Rate of induction of labor.

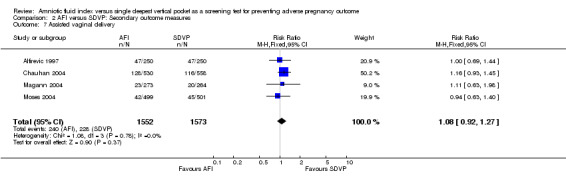

7. Assisted vaginal delivery (without specified indication)

Assisted vaginal delivery: no evidence of a difference between the two groups (RR 1.08; 95% CI 0.92 to 1.27; four trials, 3125 deliveries) (see Analysis 2.7).

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 AFI versus SDVP: Secondary outcome measures, Outcome 7 Assisted vaginal delivery.

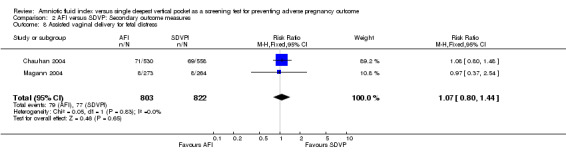

8. Assisted vaginal delivery for fetal distress

Assisted vaginal delivery for fetal distress: no evidence of a difference between the two groups (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.44; two trials, 1625 deliveries) (see Analysis 2.8).

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 AFI versus SDVP: Secondary outcome measures, Outcome 8 Assisted vaginal delivery for fetal distress.

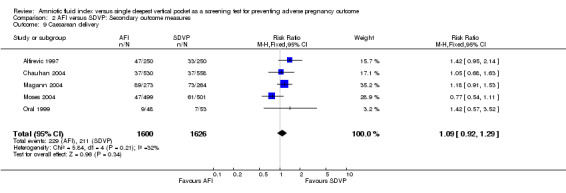

9. Rate of caesarean section

Caesarean delivery: no evidence of a difference between the two groups (RR 1.09; 95% CI 0.92 to 1.29; five trials, 3226 deliveries) (see Analysis 2.9).

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 AFI versus SDVP: Secondary outcome measures, Outcome 9 Caesarean delivery.

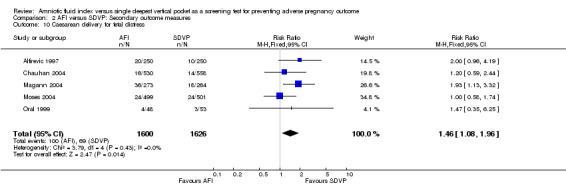

10. Caesarean section for fetal distress

Caesarean delivery for fetal distress was higher when the AFI was used for fetal surveillance (RR 1.46; 95% CI 1.08 to 1.96; five trials, 3226 deliveries) (see Analysis 2.10).

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 AFI versus SDVP: Secondary outcome measures, Outcome 10 Caesarean delivery for fetal distress.

11. Length of neonatal intensive care unit stay

None of the trials reported length of stay in a neonatal intensive care unit.

Discussion

Various antepartum fetal surveillance tests have the aim of providing the obstetrician with a tool that guides intervention with the ultimate goal of preventing clear‐cut adverse pregnancy outcomes. Both the biophysical profile (BPP) and the modified BPP (MBPP) include the assessment of AFV as an integral part of testing because decreased AFV (oligohydramnios) in a pregnancy without fetal renal agenesis or obstructive uropathy is believed to indicate a fetal response to chronic stress (Gramellini 2004; Sherer 2002).

The most common techniques used to ensure that the amniotic fluid is adequate are the AFI (Phelan 1987) and the SDVP measurement (Chamberlain 1984). According to these two methods, an AFI of 5 cm or less, or the absence of a pocket measuring 2 x 1 cm is indicative of decreased AFV.

Summary of main results

This meta‐analysis has demonstrated that pregnant women are significantly more likely to be diagnosed with oligohydramnios, be induced for an abnormal fluid volume, and undergo a caesarean delivery for fetal distress if AFI is used for fetal assessment. The major outcomes of concern are admission to a neonatal intensive care unit, neonatal acidosis, the presence of meconium, perinatal death, and an Apgar score of less than 7 at five minutes, all of which were similar in both groups. A higher rate of obstetric intervention can be justified only if there is a demonstrable decrease in the rate of poor pregnancy outcomes. Identifying a pregnant woman as having an oligohydramnios creates a form of the hoax effect, causing a higher number of inductions. This higher induction rate and a low threshold for the diagnosis of fetal distress led to a higher rate of caesarean section for so‐called fetal distress in labor.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The studies identified were sufficient to address all the objectives of this review. All our potential types of participants, interventions, and outcomes were investigated, except length of stay in a neonatal intensive care unit. This meta‐analysis shows that, when comparing the use of AFI and SDVP, the AFI is associated with a higher rate of obstetric intervention without an improvement in pregnancy outcomes. This implies that the SDVP measurement is probably a better method to estimate AFV. The results of this meta‐analysis should be interpreted with caution for two reasons. First, both methods have a poor sensitivity and specificity in detecting abnormal AFV. Second, multiple factors contribute to pregnancy outcomes in women undergoing antepartum fetal surveillance.

The results are important for current practice. Should the obstetrician base a clinical decision on the SDVP measurement or on the AFI? Today, some centres use the AFI and others the SDVP. A dilemma is evident when considering the two tests of antepartum assessment of fetal well‐being: the BPP and the MBPP. In the BPP, the measurement of the single deepest pool is recorded in order to calculate the overall BPP score. In the MBPP, the AFI is used to assess the fluid volume. This is not merely an academic exercise or dilemma; it is a dilemma in our everyday practice. It is obviously confusing for caregivers when the same patient achieves a reassuring score of 10 for a BPP and then in the same file the sonographer describes the fluid as abnormal by using an AFI criterion.

Quality of the evidence

The trials included in this meta‐analysis were of good quality with adequate allocation concealment. The analysis included five studies (3226 pregnancies). The results of the present meta‐analysis are consistent among all the trials included in the analysis.

Potential biases in the review process

We identified all relevant trials. We obtained all the relevant data.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The SDVP was routinely used to assess AFV until 1987, when Phelan and co‐authors (Phelan 1987) suggested that the AFI should be used instead. This first description of the technique was followed by reports by Rutherford et al. (Rutherford 1987a; Rutherford 1987b) and Sarno et al. (Sarno 1989), which noted an increased rate of caesarean delivery for a non‐reassuring fetal heart rate tracing and low Apgar scores in association with an AFI below the arbitrary cut‐off point of 5 cm. This led to widespread adoption of the AFI as the method of choice for the assessment of amniotic fluid during antepartum fetal surveillance. This move can be criticized because of three important facts: reports have used subjective surrogate measures of neonatal morbidity; the incidence of neonatal acidosis, an objective assessment of fetal well‐being, was not addressed in the early reports; and RCTs were not implemented to substantiate adoption of the AFI. An early case control study showed that 72% of women with an AFI of 5 cm or less still had a SDVP measurement of greater than 2 cm (Magann 1999b). Subsequently, RCTs have shown significantly greater numbers of women diagnosed as having oligohydramnios by measuring the AFI compared with the SDVP (Alfirevic 1997; Chauhan 2004; Magann 2004; Moses 2004). This can be explained by the higher specificity of the SDVP measurement compared with the AFI in the assessment of decreased AFV. The results of our meta‐analysis show that the use of the AFI led to more diagnoses of oligohydramnios, more inductions of labor and caesarean deliveries for fetal distress without improving perinatal outcome. A recent study revealed that the criteria for determining the adequacy of amniotic fluid using the AFI are not diagnostically useful for identifying peripartum complications (Johnson 2007). An earlier prospective double‐blind cohort study also showed that the use of the AFI in pregnancies beyond 40 weeks, is likely to lead to increased obstetric intervention without improvement in perinatal outcomes (Morris 2003).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The use of the AFI increases the intervention rate without an improvement in pregnancy outcomes. The SDVP measurement appears to be the more appropriate method for assessing AFV during fetal surveillance. It is also logical to recommend that only one method should be used for fetal assessment tests.

Implications for research.

A systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of amniotic fluid index versus single deepest vertical pocket is needed. Further trials are warranted to reach a consensus and standardize the method to be used to detect a decreased AFV by means of the various tests for fetal well‐being. The results of such trials and the consensus required would help to answer the question of when and how delivery should take place and reflect objective pregnancy outcomes.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 24 March 2009 | New search has been performed | Search updated January 2009. No new trials identified. One trial (Oral 1999) previously identified as 'awaiting classification' has now been included. 'Summary of findings' table has been added and the 'Risk of bias' table has been expanded. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2007 Review first published: Issue 3, 2008

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 27 February 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

The valuable contribution of Dr Susan Saad in supplying full‐text articles is greatly appreciated.

We thank Dr. Nancy Santesso (Grade Working Group) for her professional help on the SoF Table.

We would not have been able to finish this work without the sincere help of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Managing Editor, Deputy Managing Editor, and Trials Search Co‐ordinator.

We thank A Balistreri for providing translation of Oral 1999.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library)

#1 Pregnancy/ #2 Pregnancy Complications/ #3 Fetus/ #4 Fetal Monitoring/ #5 pregnan* #6 antepart* #7 prenatal* #8 antenatal* #9 perinatal* #10 intrapart* #11 amniotic near fluid #12 amniotic near volume #13 vertical near pocket #14 #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 #15 #11 or #12 or #13 #16 #14 and #15

MEDLINE

1.randomised controlled trial.pt. 2.randomised controlled trials/ 3.controlled clinical trial.pt. 4.random allocation/ 5.double blind method/ 6.single‐blind method/ 7.or/1‐6 8.clinical trial.pt. 9.exp clinical trials/ 10.(clin$ adj25 trial$).tw. 11.((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).tw. 12.placebos/ 13.placebo$.tw. 14.random$.tw. 15.research design/ 16.or/8‐15 17.comparative study/ 18.exp evaluation studies/ 19.follow up studies/ 20.prospective studies/ 21.(control$ or prospectiv$ or volunteer$).tw. 22.or/17‐21 23.animal/ not (human/ and animal/) 24.7 or 16 or 22 25.24 not 23 26.exp pregnancy/ 27.exp fetus/ 28.exp infant, newborn/ 29.exp pregnancy complications/ 30.or/ 26‐30 31 25 and 31 32. amniotic fluid index.tw 33. amniotic fluid pocket.tw 34. oligohydramnios.tw 35. umbilical artery pH.tw 36. fetal monitoring.tw 37. or/ 32‐36 38 37 and 31

mRCT (searched using each term individually)

1 Amniotic fluid index 2 Single deepest vertical pocket 3 Oligohydramnios 4 Fetal monitoring

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. AFI versus SDVP: Primary outcome measures.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Admission to neonatal intensive care unit | 5 | 3226 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.85, 1.26] |

| 2 Perinatal deaths | 3 | 1689 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Comparison 2. AFI versus SDVP: Secondary outcome measures.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Rate of diagnosis of oligohydramnios | 5 | 3226 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.39 [1.73, 3.28] |

| 2 Umbilical artery pH less than 7.1 | 3 | 2625 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.74, 1.65] |

| 3 Apgar score less than seven at five minutes | 5 | 3226 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.70, 1.89] |

| 4 Presence of meconium | 5 | 3226 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.90, 1.30] |

| 5 Non‐reassuring fetal heart rate tracing | 4 | 2726 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.13 [0.93, 1.36] |

| 6 Rate of induction of labor | 4 | 2138 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.92 [1.50, 2.46] |

| 7 Assisted vaginal delivery | 4 | 3125 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.92, 1.27] |

| 8 Assisted vaginal delivery for fetal distress | 2 | 1625 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.80, 1.44] |

| 9 Caesarean delivery | 5 | 3226 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.92, 1.29] |

| 10 Caesarean delivery for fetal distress | 5 | 3226 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.46 [1.08, 1.96] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Alfirevic 1997.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Women were allocated to monitoring by sealed envelopes prepared in blocks of 100. Each block was prepared by shuffling 2 sets of 50 cards which were sealed in sequentially‐numbered opaque envelopes. The allocation sequence was recorded on a master list which was held separately. | |

| Participants | 500 women with singleton uncomplicated post‐term pregnancies. | |

| Interventions | AFI in 250 and single deepest pocket in 250 cases. | |

| Outcomes | Admission to NICU, induction of labor, caesarean section, CS for fetal distress, instrumental delivery, oligohydramnios, Apgar score < 7 at 5 min, perinatal death, presence of meconium. | |

| risk status of subjects | High risk. | |

| Notes | UK. July 1994 to July 1995. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Shuffling cards. |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Adequate. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | |

Chauhan 2004.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Randomisation was accomplished via use of a computer‐generated random number table with blocked permutations. Randomisation was accomplished by opening sealed opaque envelopes containing group allocations that were prepared in blocks of 14 envelopes, 7 per allocation. When the envelope pack was reduced to 8 envelopes, a new block of 14 envelopes was supplemented. A person not directly associated with the study performed randomization and envelope preparation. | |

| Participants | 1088 pregnant women. | |

| Interventions | AFI in 530 and single deepest pocket in 558 cases. | |

| Outcomes | Umbilical artery pH < 7.1, CS for fetal distress and admission to NICU, oligohydramnios, non‐reassuring fetal heart rate (FHR) tracing, assisted vaginal delivery, caesarean section, Apgar score < 7 at 5 min, presence of meconium, perinatal death. | |

| risk status of subjects | High risk. | |

| Notes | USA. 1997 to 2001. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Computer‐generated random number table with blocked permutations. |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Adequate. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | |

Magann 2004.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. A randomization schedule was prepared in advance using a computer‐generated number table with a card sealed in an opaque envelope that assigned patients to have the amniotic fluid assessed either with AFI or single deepest pocket. | |

| Participants | 537 pregnant women. | |

| Interventions | AFI in 273 and single deepest pocket in 264 cases. | |

| Outcomes | Umbilical artery pH < 7.1, CS for fetal distress and admission to NICU, Apgar scores < 7 at 5 min, oligohydramnios, presence of meconium. | |

| risk status of subjects | High risk. | |

| Notes | USA. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Computer‐generated random number table. |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Adequate. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Free of selective reporting? | High risk | No data provided regarding perinatal death. |

Moses 2004.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Women who gave signed consent were assigned randomly to groups by a computer‐generated random number table with blocked permutations. Group assignment was placed into sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes. A person who was not associated directly with the study performed randomization and envelope preparation. Women were assigned either to the AFI group or the single deepest pocket technique group. The caregivers were not aware of the group assignment or the specific measurement. | |

| Participants | 1000 pregnant women. | |

| Interventions | AFI in 499 and single deepest pocket in 501 cases. | |

| Outcomes | Umbilical artery pH < 7.1, CS for fetal distress and admission to NICU, oligohydramnios, Induction of labor, assisted vaginal delivery, caesarean delivery, Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes. | |

| risk status of subjects | High risk. | |

| Notes | USA. July 2001 to January 2003. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Computer‐generated random number table. |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Adequate. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | The caregivers were not aware of the group assignment or the specific measurement |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Free of selective reporting? | High risk | No data provided regarding perinatal death. |

Oral 1999.

| Methods | Women at their 290th day of gestation were randomly assigned to either amniotic fluid index (four‐quadrant technique) or maximal vertical pocket. In both cases electronic foetal heart monitoring. | |

| Participants | 101 women with singleton uncomplicated post‐term pregnancies. | |

| Interventions | AFI in 48 and single deepest pocket in 53 cases. | |

| Outcomes | Admission to NICU, induction of labor, caesarean section, CS for fetal distress, oligohydramnios, Apgar score < 7 at 5 min, perinatal death, presence of meconium. | |

| risk status of subjects | High risk. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not stated. Probably not done due to different technique. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | |

AFI = Amniotic Fluid Index CS = Caesarean Section NICU = Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Alfirevic 1995 | This was a randomized controlled trial comparing simple with complex antenatal fetal monitoring after 42 weeks of gestation. The study did not include a comparison between AFI and SDVP. |

| Callan 1996 | This trial compared curvilinear and linear transducers. It did not include data on a comparison between AFI and SDVP. |

| Chauhan 1995 | This was a randomized study to assess the efficacy of the amniotic fluid index as a fetal admission test. It did not include data on the SDVP. |

| Magann 1994 | This trial assessed the accuracy of ultrasonic techniques for the evaluation of amniotic fluid volume in twins. |

AFI = Amniotic Fluid Index SDVP = Single Deepest Vertical Pocket

Differences between protocol and review

This updated review now incorporates the latest methods for assessing methodological quality of the included studies.

Contributions of authors

AF Nabhan proposed the topic and wrote the protocol. YA Abdelmoula contributed to the development of the protocol and commented on drafts. Both authors independently assessed eligibility and quality, and extracted the data. Both authors collaborated in writing the full review. AF Nabhan created the summary of findings table. AF Nabhan updated the review and YA Abdelmoula commented on the update.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

Egyptian Center of Evidence Based Medicine, Egypt.

Declarations of interest

None known.

Unchanged

References

References to studies included in this review

Alfirevic 1997 {published data only}

- Alfirevic Z, Luckas M, Walkinshaw SA, McFarlane M, Curran R. A randomised comparison between amniotic fluid index and maximum pool depth in the monitoring of post‐term pregnancy. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1997;104:207‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chauhan 2004 {published data only}

- Chauhan SP, Doherty DD, Magann EF, Cahanding F, Moreno F, Klausen JH. Amniotic fluid index vs single deepest pocket technique during modified biophysical profile: a randomized clinical trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2004;191(2):661‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Magann 2004 {published data only}

- Magann E, Doherty D, Field K, Chauhan S, Muffley PE. Biophysical profile with amniotic fluid volume assessment: a randomized controlled trial of the amniotic fluid index versus single deepest pocket. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2003;189(6 Suppl 1):S179. [Google Scholar]

- Magann EF, Doherty DA, Field K, Chauhan SP, Muffley PE, Morrison JC. Biophysical profile with amniotic fluid volume assessments. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2004;104(1):5‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moses 2004 {published data only}

- Moses J, Doherty DA, Magann EF, Chauhan SP, Morrison JC. A randomized clinical trial of the intrapartum assessment of amniotic fluid volume: amniotic fluid index versus the single deepest pocket technique. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2004;190:1564‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Oral 1999 {published data only}

- Oral B, Gocen C, Ozbasar D. A comparison between two different ultrasonographic methods for assessing amniotic fluid volume in postterm pregnancies [Postterm gebeliklerde amniyotik sivi hacminin degerlendirilmesinde iki farkli ultrasonografi yonteminin karsilastirimasi]. Ondokuz Mayis Universitesi Tip Dergisi 1999;16:180‐6. [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Alfirevic 1995 {published data only}

- Alfirevic Z, Walkinshaw SA. A randomised controlled trial of simple compared with complex antenatal fetal monitoring after 42 weeks of gestation. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1995;102:638‐43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Callan 1996 {published data only}

- Callan FT, Jaekle RK, Karpel BM, Meyer BA. Amniotic fluid index: comparison of curvilinear and linear transducers. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1996;174(1 Pt 2):415. [Google Scholar]

Chauhan 1995 {published data only}

- Chauhan SP, Washburne JF, Magann EF, Perry KG, Martin JN, Morrison JC. A randomized study to assess the efficacy of the amniotic fluid index as a fetal admission test. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1995;86:9‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Magann 1994 {published data only}

- Magann EF, Morton ML, Chauhan SP, Martin JN, Whitworth NS, Morrison JC. Accuracy of ultrasonic techniques for the evaluation of amniotic fluid volume in twins. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1994;170:365. [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Bastide 1986

- Bastide A, Manning F, Harman C, Lange I, Morrison I. Ultrasound evaluation of amniotic fluid: outcome of pregnancies with severe oligohydramnios. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1986;154(4):895‐900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Casey 2000

- Casey BM, McIntire DD, Bloom SL, Lucas MJ, Santos R, Twickler DM, et al. Pregnancy outcomes after antepartum diagnosis of oligohydramnios at or beyond 34 weeks' gestation. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2000;182(4):909‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chamberlain 1984

- Chamberlain PF, Manning FA, Morrison I, Harman CR, Lange IR. Ultrasound evaluation of amniotic fluid volume. I. The relationship of marginal and decreased amniotic fluid volumes to perinatal outcome. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1984;150(3):245‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chauhan 1999

- Chauhan SP, Sanderson M, Hendrix NW, Magann EF, Devoe LD. Perinatal outcome and amniotic fluid index in the antepartum and intrapartum periods: a meta‐analysis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1999;181(6):1473‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Croom 1992

- Croom CS, Banias BB, Ramos‐Santos E, Devoe LD, Bezhadian A, Hiett AK. Do semiquantitative amniotic fluid indexes reflect actual volume?. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1992;167(4 Pt 1):995‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fischer 1993

- Fischer RL, McDonnell M, Bianculli KW, Perry RL, Hediger ML, Scholl TO. Amniotic fluid volume estimation in the postdate pregnancy: a comparison of techniques. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1993;81(5 Pt 1):698‐704. [0029‐7844 (Print)] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fok 2006

- Fok WY, Chan LY, Lau TK. The influence of fetal position on amniotic fluid index and single deepest pocket. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology 2006;28(2):162‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Garmel 1997

- Garmel SH, Chelmow D, Sha SJ, Roan JT, D'Alton ME. Oligohydramnios and the appropriately grown fetus. American Journal of Perinatology 1997;14(6):359‐63. [0735‐1631 (Print)] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Goldstein 1988

- Goldstein RB, Filly RA. Sonographic estimation of amniotic fluid volume. Subjective assessment versus pocket measurements. Journal of Ultrasound Medicine 1988;7(7):363‐9. [0278‐4297 (Print)] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gramellini 2004

- Gramellini D, Fieni S, Verrotti C, Piantelli G, Cavallotti D, Vadora E. Ultrasound evaluation of amniotic fluid volume: methods and clinical accuracy. Acta Bio‐Medica de L'Ateneo Parmense 2004;75 Suppl 1:40‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hashimoto 1987

- Hashimoto B, Filly RA, Belden C, Callen PW, Laros RK. Objective method of diagnosing oligohydramnios in postterm pregnancies. Journal of Ultrasound Medicine 1987;6(2):81‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2008

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.1 [updated September 2008]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Hill 1983

- Hill LM, Breckle R, Wolfgram KR, O'Brien PC. Oligohydramnios: ultrasonically detected incidence and subsequent fetal outcome. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1983;147(4):407‐10. [0002‐9378 (Print)] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hinh 2005

- Hinh ND, Ladinsky JL. Amniotic fluid index measurements in normal pregnancy after 28 gestational weeks. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2005;91(2):132‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jaba 2005

- Jaba B, Mohiuddin AS, Dey SN, Khan NA, Talukder SI. Ultrasonographic determination of amniotic fluid volume in normal pregnancy. Mymensingh Medical Journal 2005;14(2):121‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Johnson 2007

- Johnson JM, Chauhan SP, Ennen CS, Niederhauser A, Magann EF. A comparison of 3 criteria of oligohydramnios in identifying peripartum complications: a secondary analysis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2007;197(2):207.e1‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kawasaki 2002

- Kawasaki N, Nishimura H, Yoshimura T, Okamura H. A diminished intrapartum amniotic fluid index is a predictive marker of possible adverse neonatal outcome when associated with prolonged labor. Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation 2002;53(1):1‐5. [0378‐7346 (Print)] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Locatelli 2004

- Locatelli A, Zagarella A, Toso L, Assi F, Ghidini A, Biffi A. Serial assessment of amniotic fluid index in uncomplicated term pregnancies: prognostic value of amniotic fluid reduction. Journal of Maternal‐Fetal & Neonatal Medicine 2004;15(4):233‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Magann 1992

- Magann EF, Nolan TE, Hess LW, Martin RW, Whitworth NS, Morrison JC. Measurement of amniotic fluid volume: accuracy of ultrasonography techniques. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1992;167(6):1533‐7. [0002‐9378 (Print)] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Magann 1999a

- Magann EF, Chauhan SP, Kinsella MJ, McNamara MF, Whitworth NS, Morrison JC. Antenatal testing among 1001 patients at high risk: the role of ultrasonographic estimate of amniotic fluid volume. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1999;180(6 Pt 1):1330‐6. [0002‐9378 (Print)] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Magann 1999b

- Magann EF, Kinsella MJ, Chauhan SP, McNamara MF, Gehring BW, Morrison JC. Does an amniotic fluid index of </=5 cm necessitate delivery in high‐risk pregnancies? A case‐control study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1999;180:1354‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Magann 2000

- Magann EF, Isler CM, Chauhan SP, Martin JN, Jr. Amniotic fluid volume estimation and the biophysical profile: a confusion of criteria. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2000;96(4):640‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Magann 2003

- Magann EF, Chauhan SP, Bofill JA, Martin JN, Jr. Comparability of the amniotic fluid index and single deepest pocket measurements in clinical practice. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2003;43(1):75‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Manning 1981

- Manning FA, Hill LM, Platt LD. Qualitative amniotic fluid volume determination by ultrasound: antepartum detection of intrauterine growth retardation. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1981;139(3):254‐8. [0002‐9378 (Print)] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Morris 2003

- Morris JM, Thompson K, Smithey J, Gaffney G, Cooke I, Chamberlain P, et al. The usefulness of ultrasound assessment of amniotic fluid in predicting adverse outcome in prolonged pregnancy: a prospective blinded observational study. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2003;110(11):989‐94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Myles 2002

- Myles TD, Santolaya‐Forgas J. Normal ultrasonic evaluation of amniotic fluid in low‐risk patients at term. Journal of Reproductive Medicine 2002;47(8):621‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Peedicayil 1994

- Peedicayil A, Mathai M, Regi A, Aseelan L, Rekha K, Jasper P. Inter‐ and intra‐observer variation in the amniotic fluid index. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1994;84(5):848‐51. [0029‐7844 (Print)] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Phelan 1987

- Phelan JP, Smith CV, Broussard P, Small M. Amniotic fluid volume assessment with the four‐quadrant technique at 36‐42 weeks' gestation. Journal of Reproductive Medicine 1987;32(7):540‐2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2008 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.0. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008.

Rogers 1999

- Rogers MS, Wang CC. A comparison of three ultrasound estimates of intrapartum oligohydramnios for prediction of fetal hypoxia‐reperfusion injury. Early Human Development 1999;56(2‐3):117‐26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ross 2001

- Ross MG, Brace RA. National Institute of Child Health and Development Conference summary: amniotic fluid biology‐‐basic and clinical aspects. Journal of Maternal‐Fetal Medicine 2001;10(1):2‐19. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rutherford 1987a

- Rutherford SE, Smith CV, Phelan JP, Kawakami K, Ahn MO. Four‐quadrant assessment of amniotic fluid volume. Interobserver and intraobserver variation. Journal of Reproductive Medicine 1987;32:587‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rutherford 1987b

- Rutherford SE, Phelan JP, Smith CV, Jacobs N. The four‐quadrant assessment of amniotic fluid volume: an adjunct to antepartum fetal heart rate testing. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1987;70:353‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sarno 1989

- Sarno AP Jr, Ahn MO, Brar HS, Phelan JP, Platt LD. Intrapartum Doppler velocimetry, amniotic fluid volume, and fetal heart rate as predictors of subsequent fetal distress. I. An initial report. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1989;161:1508‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Seffah 1999

- Seffah JD, Armah JO. Amniotic fluid index for screening late pregnancies. East African Medical Journal 1999;76(6):348‐51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sherer 2002

- Sherer DM. A review of amniotic fluid dynamics and the enigma of isolated oligohydramnios. American Journal of Perinatology 2002;19(5):253‐66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Williams 1993

- Williams K. Amniotic fluid assessment. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey 1993;48(12):795‐800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]