Abstract

Background

In most pregnancies that miscarry, arrest of embryonic or fetal development occurs some time (often weeks) before the miscarriage occurs. Ultrasound examination can reveal abnormal findings during this phase by demonstrating anembryonic pregnancies or embryonic or fetal death. Treatment before 14 weeks has traditionally been surgical but medical treatments may be effective, safe, and acceptable, as may be waiting for spontaneous miscarriage.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness, safety and acceptability of any medical treatment for early pregnancy failure (anembryonic pregnancies or embryonic and fetal deaths before 24 weeks).

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group Trials Register (30 November 2005). We updated this search on 6 August 2012 and added the results to the awaiting classification section of the review.

Selection criteria

Randomised trials comparing medical treatment with another treatment (e.g. surgical evacuation), or placebo, or no treatment for early pregnancy failure. Quasi‐random studies were excluded.

Data collection and analysis

Data were extracted unblinded.

Main results

Twenty four studies (1888 women) were included.

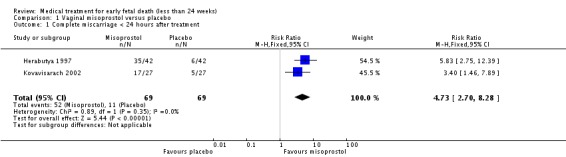

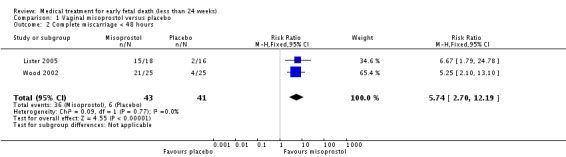

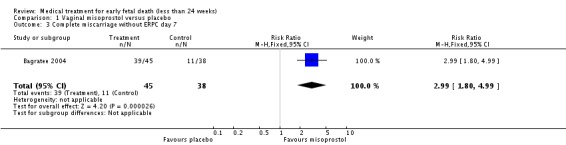

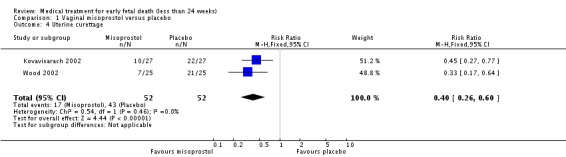

Vaginal misoprostol hastens miscarriage (complete or incomplete) when compared with placebo: e.g. miscarriage less than 24 hours (two trials, 138 women, relative risk (RR) 4.73, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.70 to 8.28), with less need for uterine curettage (two trials, 104 women, RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.60) and no significant increase in nausea or diarrhoea. Lower‐dose regimens of vaginal misoprostol tend to be less effective in producing miscarriage (three trials, 247 women, RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.00) with similar incidence of nausea. There seems no clear advantage to administering a 'wet' preparation of vaginal misoprostol or of adding methotrexate, or of using laminaria tents after 14 weeks. Vaginal misoprostol is more effective than vaginal prostaglandin E in avoiding surgical evacuation. Oral misoprostol was less effective than vaginal misoprostol in producing complete miscarriage (two trials, 218 women, RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.82 to 0.99). Sublingual misoprostol had equivalent efficacy to vaginal misoprostol in inducing complete miscarriage but was associated with more frequent diarrhoea. The two trials of mifepristone treatment generated conflicting results. There was no statistically significant difference between vaginal misoprostol and gemeprost in the induction of miscarriage for fetal death after 13 weeks.

Authors' conclusions

Available evidence from randomised trials supports the use of vaginal misoprostol as a medical treatment to terminate non‐viable pregnancies before 24 weeks. Further research is required to assess effectiveness and safety, optimal route of administration and dose. Conflicting findings about the value of mifepristone need to be resolved by additional study.

[Note: the 108 citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.]

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Fetal Death; Fetal Death/diagnostic imaging; Abortifacient Agents; Abortifacient Agents/therapeutic use; Abortion, Induced; Abortion, Induced/methods; Administration, Intravaginal; Administration, Oral; Mifepristone; Mifepristone/therapeutic use; Misoprostol; Misoprostol/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Ultrasonography, Prenatal

Medical treatment for early fetal death (less than 24 weeks)

Medical treatments for inevitable miscarriage.

Pregnancies that miscarry can sometimes be identified earlier at an ultrasound scan if the loss is due to the baby having died or no baby having developed. In the past, treatment before 14 weeks has usually been by surgery (D&C) but drugs have now been developed which may be helpful, or waiting for the miscarriage to happen may be a better alternative. The review of trials assessed various potential drug treatments using different routes and different doses, compared with waiting for the miscarriage. This review identified 24 studies involving 1888 women of less than 24 weeks gestation, where the baby had died in the uterus or the baby had not formed in the uterus. Most studies were of good quality. Vaginal misoprostol brought forward the time of the miscarriage, but the studies were too small to adequately assess potential adverse effects, including future fertility. Oral misoprostol seemed less effective than the vaginal route, and women took more sick‐leave with the oral drugs. Some women may wish to hasten an inevitable miscarriage, and others may not. It appears that both forms of care can be available to women. Women who are breastfeeding an older baby may prefer to wait rather than have drug treatment. Further research is needed on drug doses, routes of administration and potential adverse effects, including future fertility, and also on women's views of drug treatment, surgery and waiting for spontaneous miscarriage.

Background

The incidence of clinically obvious miscarriage is considered to be between 10% and 15% of all pregnancies, although the real incidence may be considerably higher (Grudzinskas 1995; Howie 1995; Simpson 1991).

The widespread use of ultrasound in early pregnancy for either specific reasons (for example, vaginal bleeding) or as a routine examination (Neilson 1998) reveals 'non‐viable pregnancies' destined inevitably to miscarry in due course. These are termed 'anembryonic pregnancies' (formerly called 'blighted ova') if no embryo has developed within the gestation sac, or 'missed abortions' if an embryo or fetus is present, but is dead.

The protocol for this review aimed to combine trials of medical treatments for both non‐viable pregnancies and for incomplete miscarriage but on further reflection, this was illogical. Non‐viable pregnancies contain viable trophoblast (placental) tissue, which produces hormones, which may in theory make these pregnancies more susceptible to anti‐hormone therapy and more resistant to uterotonic (stimulating uterine contractions) therapy than pregnancies in which (incomplete) miscarriage has already taken place. This review will therefore focus exclusively on non‐viable pregnancies, before miscarriage. Another review will assess trials of medical treatments after miscarriage has occurred (Vazquez 2000). A further review compares expectant management with surgical treatment for miscarriage (Nanda 2002).

Traditionally, early non‐viable pregnancies (less than 14 weeks) have been terminated by surgical evacuation. Later pregnancies (14 to 24 weeks) have been ended by medical induction of miscarriage.

Various types of medical treatment could be suitable as alternatives to surgical treatment: misoprostol is a prostaglandin E1 analogue, marketed for the prevention and treatment of peptic ulcers. Recognized as a potent method for terminating unwanted viable pregnancies (Costa 1993; Norman 1991), it is cheap, stable at room temperature and has few systemic effects, although vomiting, diarrhoea, hypertension and even potential teratogenicity when misoprostol fails to induce abortion have been reported (Fonseca 1991). Misoprostol has been shown to be an effective myometrial stimulant of the pregnant uterus, selectively binding to EP‐2/EP‐3 prostanoid receptors (Senior 1993). It is rapidly absorbed orally and vaginally. Vaginally absorbed serum levels are more prolonged and vaginal misoprostol may have locally mediated effects (Zieman 1997).

Misoprostol could be especially useful in developing countries, where transport and storage facilities are inadequate and the availability of uterotonic agents and blood is limited. Its use in obstetrics and gynecology has been explored, especially to induce first and second trimester abortion (Ashok 1998; Bugalho 1996), for the induction of labour (Alfirevic 2001; Hofmeyr 2003) and for the prevention of postpartum haemorrhage (Gulmezoglu 2004) despite the fact that it has not been registered for such use.

Other uterotonic drugs that could have a role would include ergometrine, oxytocin, and prostaglandin F2alpha.

The progesterone antagonist, mifepristone, is of value in terminating early unwanted pregnancies and may be of use in non‐viable pregnancies and spontaneous miscarriage (Baulieu 1986; Kovacs 1984), alone or in combination with prostaglandin (Cameron 1986).

Methotrexate may be helpful in the medical treatment of ectopic pregnancy and might therefore have a place in the treatment of intrauterine non‐viable pregnancies as well. It has also been used for the early termination of unwanted pregnancy, followed by a uterotonic agent such as misoprostol.

Although clotting problems occasionally occur in women with prolonged retention of a dead fetus, this is rare and does not usually happen within the first month after fetal death. There are, therefore, not pressing medical reasons to terminate non‐viable pregnancies. Although, anecdotally, many women favour early termination, so‐called 'expectant management' (that is, awaiting spontaneous miscarriage) is a legitimate alternative and this policy should be considered in clinical care and in planning trials.

Objectives

To assess, from clinical trials, the effectiveness and safety of different medical treatments for the termination of non‐viable pregnancies, with reference to death or serious complications, additional surgical evacuation, blood transfusion, haemorrhage, blood loss, anaemia, days of bleeding, pain relief, pelvic infection, cervical damage, duration of stay in hospital, psychological effects, subsequent fertility, women's satisfaction and costs.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised clinical trials comparing a medical treatment with another treatment (for example, surgical evacuation), or placebo, or no treatment to terminate non‐viable pregnancies; random allocation to treatment and comparison groups; reasonable measures to ensure allocation concealment; and violations of allocated management not sufficient to materially affect outcomes. Quasi‐random studies were excluded.

Types of participants

Women with non‐viable pregnancies (i.e. where the embryo or fetus had died in utero, and in whom miscarriage would have happened inevitably in due course) if less than 24 weeks estimated gestational age. Subgroup analyses to be performed, if possible, for women at less than 14 weeks, and those between 14 and 23 weeks estimated gestational age.

Types of interventions

Trials were considered if they compared medical treatment with other methods (for example, expectant management, placebo or any other intervention including surgical evacuation). Comparisons between different routes of administration of medical treatment (for example, oral versus vaginal), or between different drugs or doses of drug, or duration or timing of treatment, were also included if data existed.

Types of outcome measures

Trials were considered if any of the following outcomes were reported.

Primary outcomes

Complete miscarriage (i.e. no pregnancy tissues remaining in uterus ‐ based on clinical findings at surgery and/or ultrasound examination after a specific period).

Death or serious complications (e.g. uterine rupture, uterine perforation, hysterectomy, organ failure, intensive care unit admission).

Secondary outcomes

Additional surgical evacuation

Blood transfusion

Haemorrhage

Blood loss

Anemia

Days of bleeding

Pain relief

Pelvic infection

Cervical damage

Digestive disorders (nausea or vomiting or diarrhoea)

Hypertensive disorders

Duration of stay in hospital

Psychological effects

Subsequent fertility

Woman's satisfaction/acceptability of method

Costs

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (30 November 2005). We updated this search on 6 August 2012 and added the results to Studies awaiting classification.

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

weekly searches of EMBASE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

We assessed all potential trials for eligibility according to the criteria specified in the protocol. A single author extracted data from each publication and co‐authors checked the data. We resolved any discrepancies by discussion. In addition to the main outcome measures listed above, information on the setting of the study (country, type of population, socioeconomic status), the method of randomisation, a detailed description of the regimen used (drug(s), route, dose, frequency), definitions of the outcomes (if provided), and whether or not clinicians and participants were 'blind' to treatment allocated, were all collected. An intention‐to‐treat analysis was performed where possible. Any information on completeness of follow up was collected as well.

Trials were assessed for methodological quality using the standard Cochrane criteria of adequacy of allocation concealment: (A) adequate; (B) unclear; (C) inadequate; (D) allocation concealment was not used.

We collected information on blinding of outcome assessment and loss to follow up.

Separate comparisons were made of different drug regimens, grouped where appropriate by number of doses given and the route of administration. Summary relative risks were calculated using a fixed‐effect model (providing there was no significant heterogeneity between trials ‐ defined as I squared greater than 50%). Because of the small number of trials and comparisons, it was impossible to perform sensitivity analysis using trial quality (A versus B, C, D).

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

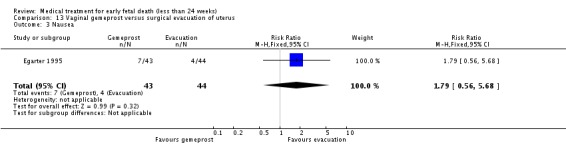

This review has included 24 studies comparing vaginal misoprostol to expectant management (Bagratee 2004), placebo (Herabutya 1997; Kovavisarach 2002; Lister 2005; Wood 2002), surgical evacuation (Demetroulis 2001; Graziosi 2004; Muffley 2002), oral or sublingual misoprostol (Creinin 1997; Ngoc 2004; Tang 2003), other types of vaginal or intracervical prostaglandin preparation (Al Inizi 2003; Eng 1997*; Fadalla 2004*; Kara 1999*); different doses (Heard 2002; Kovavisarach 2005; Niromanesh 2005*) and preparations (Gilles 2004) of vaginal misoprostol; the addition to vaginal misoprostol of methotrexate (Autry 1999) or laminaria tents (Jain 1996*); mifepristone versus placebo (Lelaidier 1993); mifepristone plus oral misoprostol versus expectant management (Nielsen 1999), and vaginal gemeprost versus surgical evacuation (Egarter 1995).

The Bagratee 2004 trial used a comparison of vaginal misoprostol versus placebo to explore comparisons with expectant management (up to seven days) and, therefore, differed in concept from the Herabutya 1997 and Wood 2002 studies in which early surgical intervention occurred after, respectively, 24 and 48 hours.

Five of the 24 included studies addressed medical treatment of non‐viable pregnancies after 14 weeks (Eng 1997*; Fadalla 2004*; Jain 1996*; Kara 1999*; Niromanesh 2005*). These are labelled with an asterisk for ease of interpretation.

There are additional trials that have included data on women with both non‐viable pregnancies and incomplete miscarriages (for example, Ngai 2001). If these can be separated by the researchers, these data may be included in the future.

(One hundred reports from an updated search on 6 August 2012 have been added to Studies awaiting classification.)

Risk of bias in included studies

Thirteen studies used robust methods of allocation concealment (Autry 1999; Bagratee 2004; Creinin 1997; Demetroulis 2001; Gilles 2004; Graziosi 2004; Kovavisarach 2005; Lelaidier 1993; Lister 2005; Muffley 2002; Ngoc 2004; Tang 2003; Wood 2002). Nine reports failed to describe the process of randomisation (Al Inizi 2003; Egarter 1995; Fadalla 2004*; Herabutya 1997; Jain 1996*; Kara 1999*; Kovavisarach 2002; Nielsen 1999; Niromanesh 2005*). One study has been reported only in abstract ‐ without randomisation details (Heard 2002). In one study, allocation was based on picking an un‐numbered envelope from a pack ‐ a method that is recognised to be less robust (Eng 1997*).

In most trials, analysis by intention‐to‐treat was performed.

It was not possible to blind the physicians to the method of treatment in some studies ‐ if this involved surgical evacuation of the uterus, alternative routes of drug administration (oral versus vaginal) or a policy of expectant management. It is, however, possible to blind the evaluator who assessed complications during the follow‐up visit but no study made mention of this.

There was variation between studies in the timing of scheduled follow‐up visits.

Effects of interventions

Twenty four studies, with a total of 1888 women, were included. Nineteen of the studies addressed termination of non‐viable pregnancies before 14 weeks.

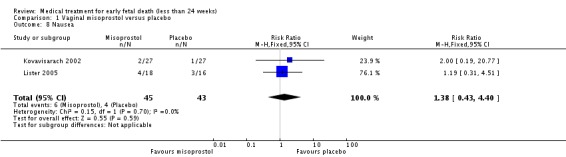

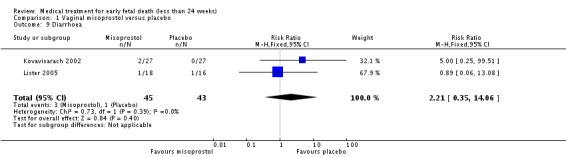

Treatment with vaginal misoprostol hastens miscarriage (passage of products of conception, whether complete or incomplete) when compared with placebo: miscarriage less than 24 hours (two trials, 138 women, relative risk (RR) 4.73, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.70 to 8.28); miscarriage less than 48 hours (two (other) trials, 84 women, RR 5.74, 95% CI 2.70 to 12.19); complete miscarriage without need for surgical intervention at seven days (one trial, 83 women, RR 2.99, 95% CI 1.80 to 4.99). There was less need for uterine curettage (two trials, 104 women, RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.60) and no statistically significant increase in adverse effects: nausea (two trials, 88 women, RR 1.38, 95% CI 0.43 to 4.40), diarrhoea (two trials, 88 women, RR 2.21, 95% CI 0.35 to 14.06). One study showed a reduction in costs associated with a strategy of starting treatment with misoprostol, compared to immediate curettage (mean difference EUR192, 95% CI 33 to 351), no obvious difference in subsequent fertility, and similar numbers of women (58%) who would choose the same treatment strategy in the future (Graziosi 2004); although more women who had complete miscarriage after misoprostol (76%) would choose this treatment than those who required subsequent curettage (38%).

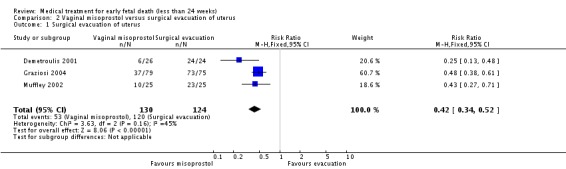

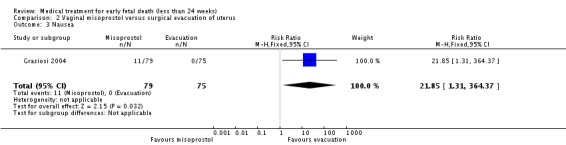

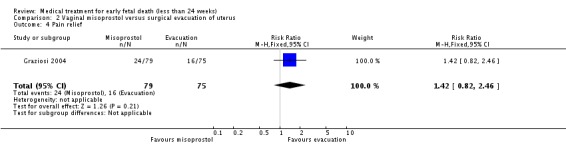

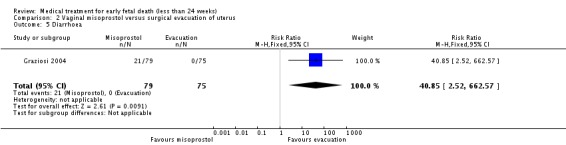

Consistent with these observations, treatment with vaginal misoprostol decreases the need for surgical evacuation of the uterus when compared with a policy of arranging immediate surgical evacuation (three trials, 254 women, RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.52) at a cost of more nausea (one trial, 154 women, RR 21.85, 95% CI 1.31 to 364.37) and diarrhoea (one trial, 154 women, RR 40.85, 95% CI 2.52 to 662.57).

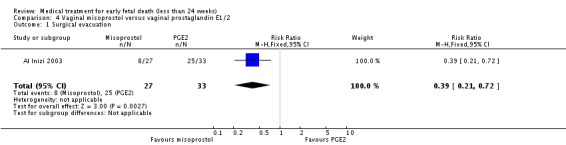

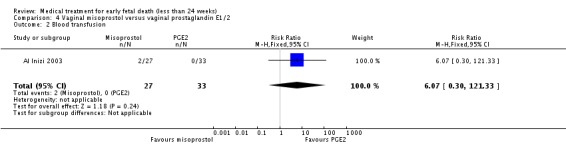

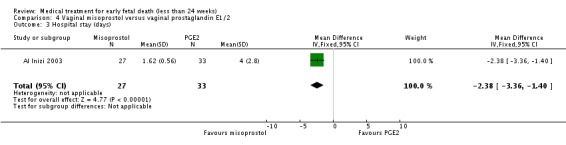

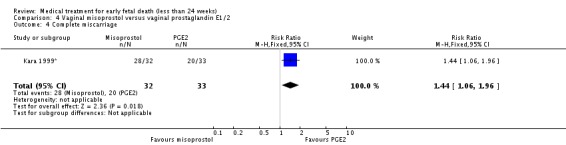

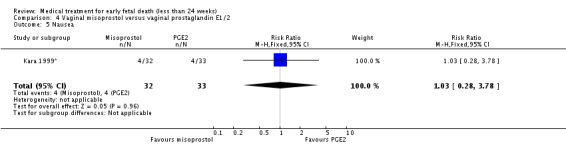

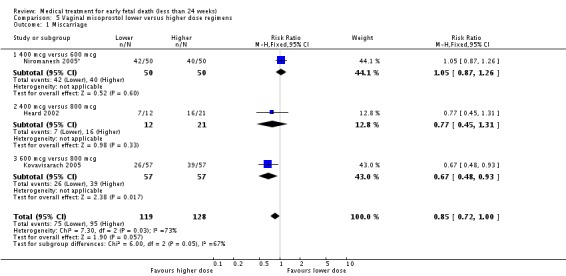

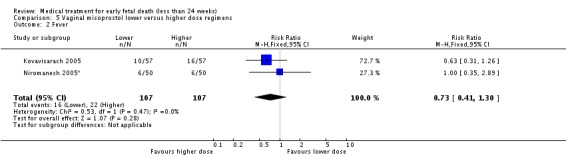

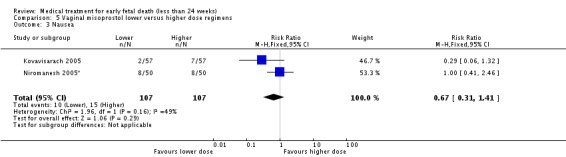

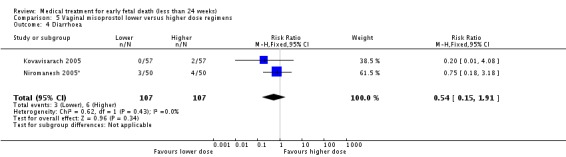

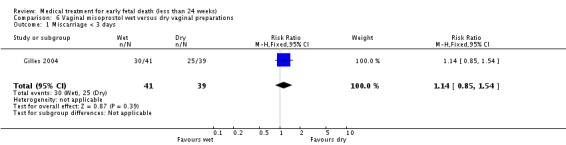

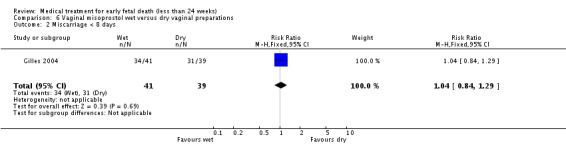

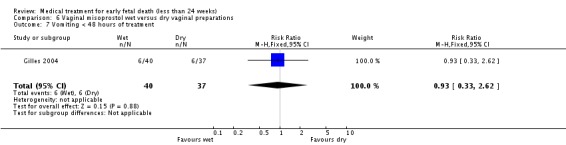

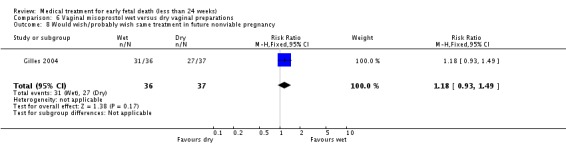

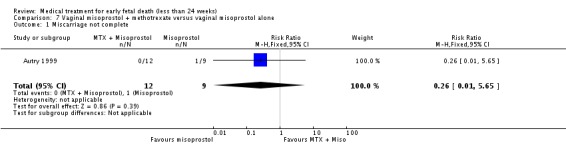

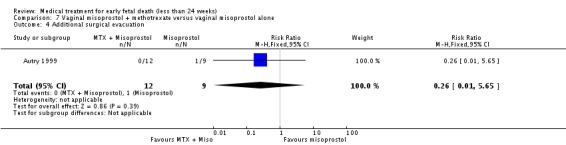

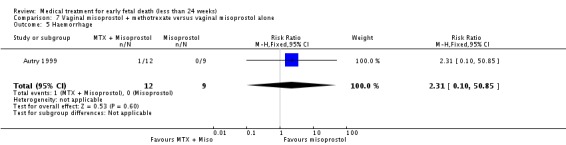

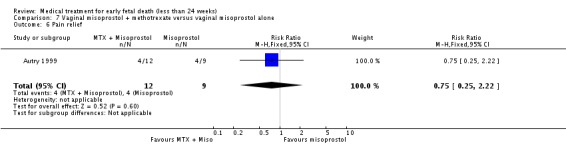

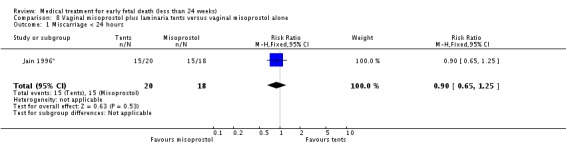

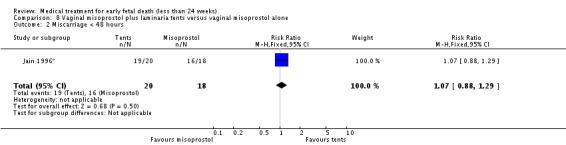

Vaginal misoprostol has been administered in doses of 400 mcg, 600 mcg, and 800 mcg in trials: lower‐dose regimens tend to be less effective in producing miscarriage (three trials, 247 women, RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.00) with similar incidence of nausea (two trials, 214 women, RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.31 to 1.41). There seems no clear advantage to administering a 'wet' preparation of vaginal misoprostol compared to a 'dry' preparation: miscarriage less than three days (one trial, 80 women, RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.54). Adding methotrexate treatment to vaginal misoprostol has not been demonstrated to be advantageous in the single small trial to address this: miscarriage not complete after treatment (21 women, RR 0.26, 95% CI 0.01 to 5.65). Nor are laminaria tests proven useful adjuncts to vaginal misoprostol during the second trimester: complete miscarriage less than 24 hours (one trial, 38 women, RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.25), less than 48 hours (one trial, 38 women, RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.29). Vaginal misoprostol was more effective than vaginal prostaglandin E in avoiding surgical evacuation (one trial, 80 women, RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.72) and effecting complete miscarriage in the second trimester (one trial, 65 women, RR 1.44, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.96).

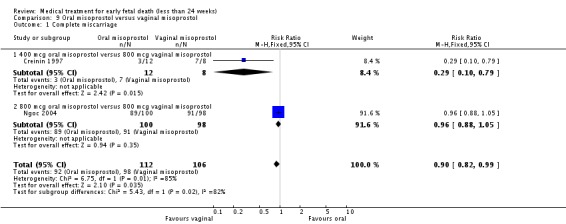

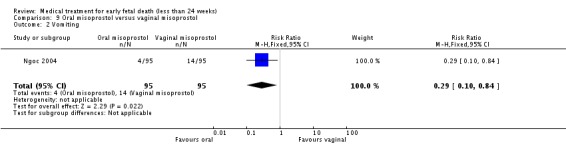

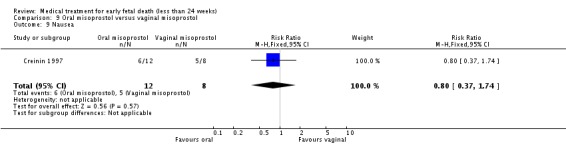

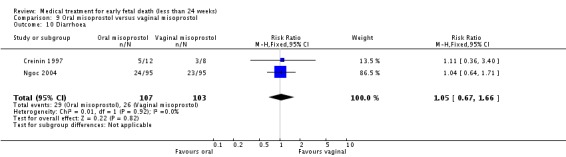

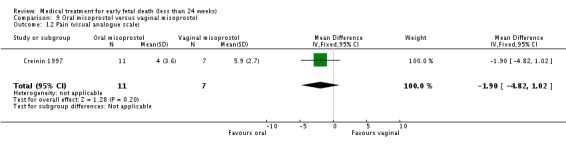

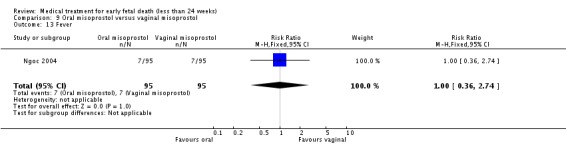

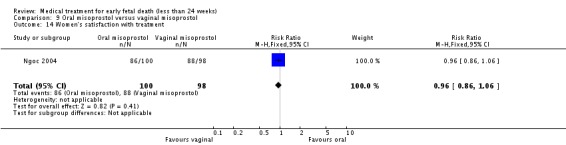

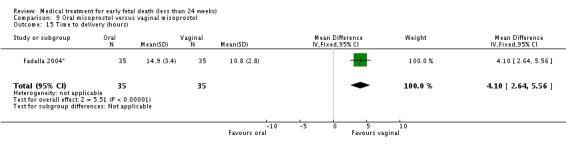

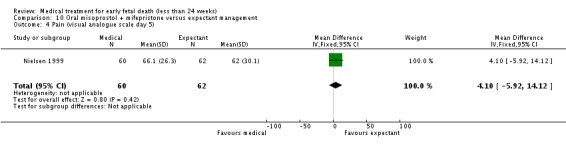

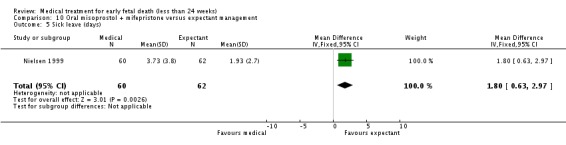

Overall, oral misoprostol was found to be less effective than vaginal misoprostol in producing complete miscarriage (two trials, 218 women, RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.82 to 0.99) but this difference was seen only with the 400 mcg oral dose (one trial, 20 women, RR 0.29, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.79) and not the 800 mcg oral dose (one trial, 198 women, RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.05). There was less vomiting with the oral regimen (one trial, 190 women, RR 0.29, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.84) but similar incidence of diarrhoea (two trials, 210 women, RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.66). There were high (and similar) levels of satisfaction with treatment (one trial, 198 women, RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.06). Oral misoprostol was slower than vaginal misoprostol in effecting miscarriage in a single trial of women with second trimester fetal death (weighted mean difference 4.10 hours, 95% CI 2.64 to 5.56).

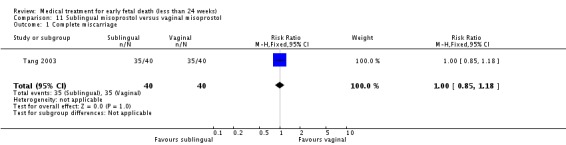

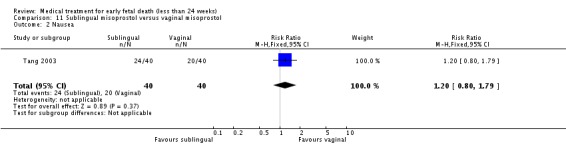

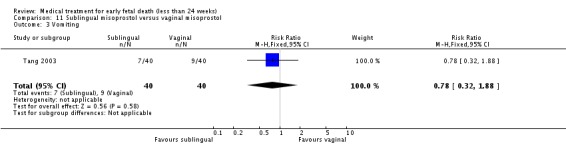

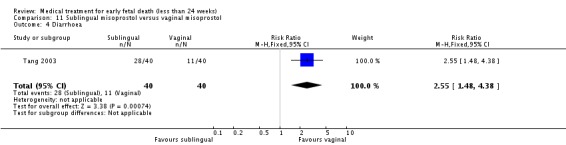

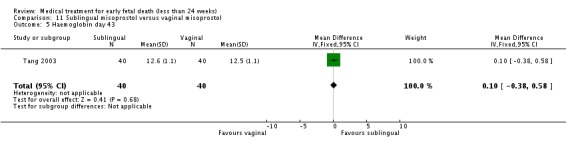

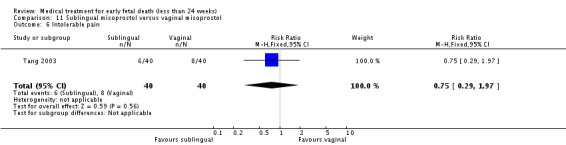

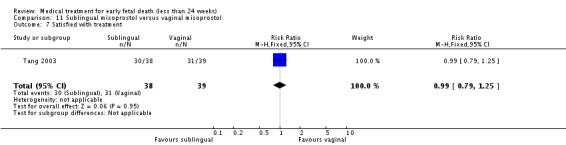

Sublingual misoprostol had equivalent efficacy to vaginal misoprostol in inducing complete miscarriage (one trial, 80 women, RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.18) but was associated with more frequent diarrhoea (RR 2.65, 95% CI 1.48 to 4.38) but not other side‐effects.

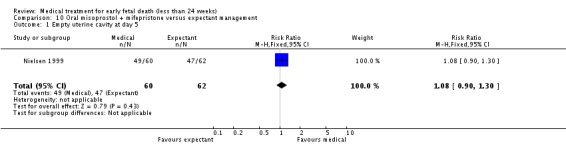

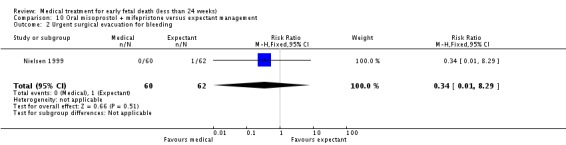

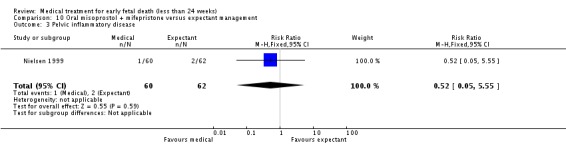

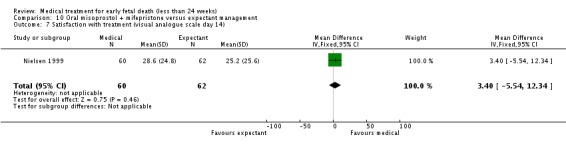

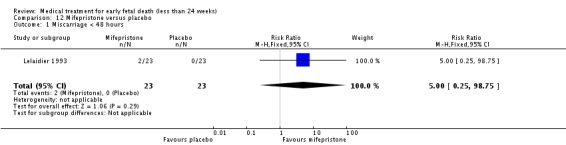

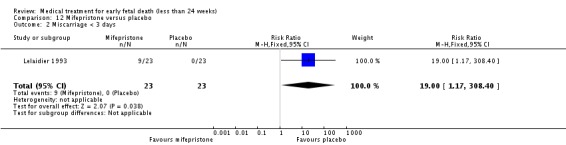

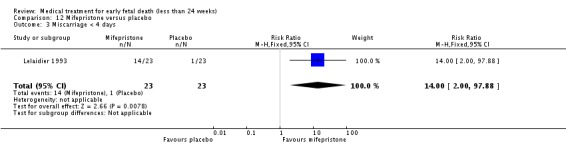

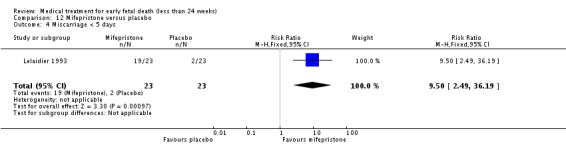

The two trials of mifepristone treatment generated conflicting results. One study found mifepristone to be much more effective than placebo: miscarriage complete by day five after treatment (46 women, RR 9.50, 95% CI 2.49 to 36.19). The other study compared treatment with mifepristone plus oral misoprostol with a policy of expectant management (no treatment); there was no statistically significant difference in complete miscarriage by day five (122 women, RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.30).

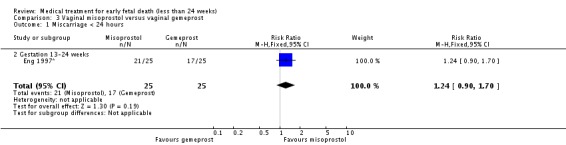

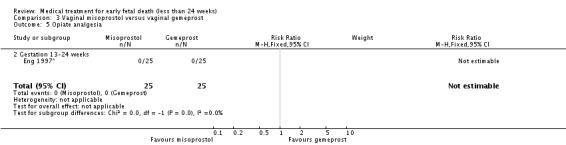

There was no statistically significant difference between vaginal misoprostol and gemeprost in the induction of miscarriage less than 24 hours for fetal death after 13 weeks (one trial, 50 women, RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.70).

There were few reports of serious adverse effects in the reported trials, but one woman required a bowel resection after uterine perforation at evacuation of the uterus (Egarter 1995).

Discussion

The large majority of included trials (21/24) addressed the use of misoprostol (mainly by vaginal administration). There is intense interest in the reproductive uses of misoprostol because it appears a potent method for pregnancy interruption as well as being cheap and stable at room temperature, and thus potentially especially useful in developing countries, where transport and storage facilities are inadequate and the availability of uterotonic agents and blood is limited. However, ultrasound imaging is needed to diagnose non‐viable pregnancies and equipment is sparse in many developing countries. The reproductive use of misoprostol is considered in other Cochrane reviews, for indications that include termination of unwanted pregnancies (Kulier 2004; Say 2002), induction of labour (Alfirevic 2001; Hofmeyr 2003; Muzonzini 2004) and prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage (Gulmezoglu 2004; Mousa 2003).

Authors' conclusions

Available evidence from randomised trials supports the use of vaginal misoprostol as one possible option for the treatment of non‐viable pregnancies before 24 weeks.

Ultrasound demonstration of early pregnancy failure before 14 weeks is a common problem that merits greater research effort than has occurred to date. Further research is required to assess the effectiveness, safety and side‐effects of misoprostol, including optimal route of administration and dose. Conflicting findings about the value of mifepristone need to be resolved by additional study. Women's views about the acceptability of medical treatment, surgical treatment and expectant management should be integral to future research protocols, as should economic assessments. Long‐term outcome, notably subsequent fertility, deserves further study in appropriately powered randomised controlled studies.

[Note: the 108 citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.]

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Sonja Henderson and Lynn Hampson of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group, Liverpool Women's Hospital, Liverpool, UK.

As part of the pre‐publication editorial process, this review has been commented on by two peers (an editor and referee who are external to the editorial team), one or more members of the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's international panel of consumers and the Group's Statistical Adviser.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1.

Vaginal misoprostol versus placebo

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Complete miscarriage < 24 hours after treatment | 2 | 138 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.73 [2.70, 8.28] |

| 2 Complete miscarriage < 48 hours | 2 | 84 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.74 [2.70, 12.19] |

| 3 Complete miscarriage without ERPC day 7 | 1 | 83 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.99 [1.80, 4.99] |

| 4 Uterine curettage | 2 | 104 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.40 [0.26, 0.60] |

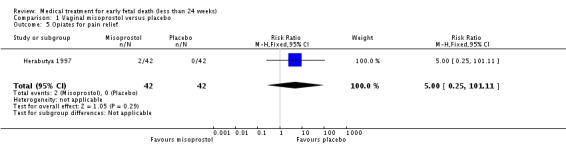

| 5 Opiates for pain relief | 1 | 84 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.0 [0.25, 101.11] |

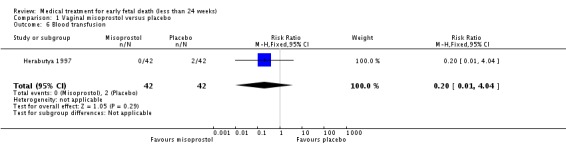

| 6 Blood transfusion | 1 | 84 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.2 [0.01, 4.04] |

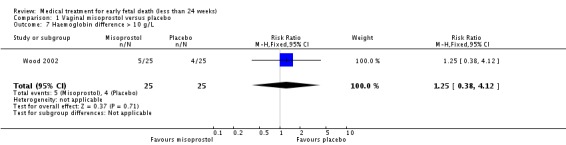

| 7 Haemoglobin difference > 10 g/L | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.38, 4.12] |

| 8 Nausea | 2 | 88 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.38 [0.43, 4.40] |

| 9 Diarrhoea | 2 | 88 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.21 [0.35, 14.06] |

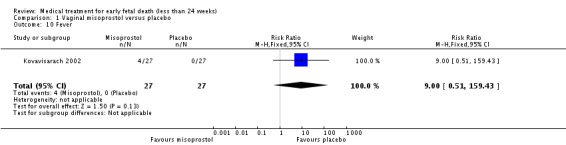

| 10 Fever | 1 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 9.0 [0.51, 159.43] |

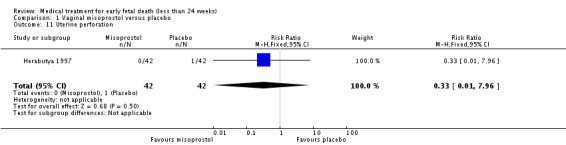

| 11 Uterine perforation | 1 | 84 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 7.96] |

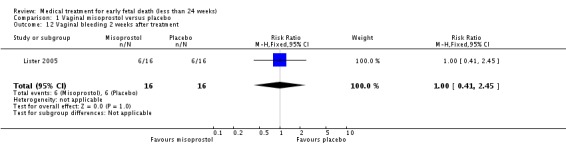

| 12 Vaginal bleeding 2 weeks after treatment | 1 | 32 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.41, 2.45] |

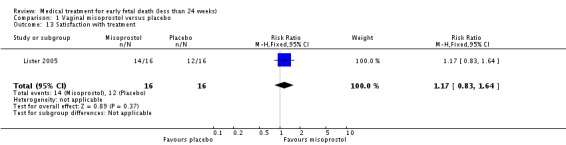

| 13 Satisfaction with treatment | 1 | 32 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.83, 1.64] |

Analysis 1.1.

Comparison 1 Vaginal misoprostol versus placebo, Outcome 1 Complete miscarriage < 24 hours after treatment.

Analysis 1.2.

Comparison 1 Vaginal misoprostol versus placebo, Outcome 2 Complete miscarriage < 48 hours.

Analysis 1.3.

Comparison 1 Vaginal misoprostol versus placebo, Outcome 3 Complete miscarriage without ERPC day 7.

Analysis 1.4.

Comparison 1 Vaginal misoprostol versus placebo, Outcome 4 Uterine curettage.

Analysis 1.5.

Comparison 1 Vaginal misoprostol versus placebo, Outcome 5 Opiates for pain relief.

Analysis 1.6.

Comparison 1 Vaginal misoprostol versus placebo, Outcome 6 Blood transfusion.

Analysis 1.7.

Comparison 1 Vaginal misoprostol versus placebo, Outcome 7 Haemoglobin difference > 10 g/L.

Analysis 1.8.

Comparison 1 Vaginal misoprostol versus placebo, Outcome 8 Nausea.

Analysis 1.9.

Comparison 1 Vaginal misoprostol versus placebo, Outcome 9 Diarrhoea.

Analysis 1.10.

Comparison 1 Vaginal misoprostol versus placebo, Outcome 10 Fever.

Analysis 1.11.

Comparison 1 Vaginal misoprostol versus placebo, Outcome 11 Uterine perforation.

Analysis 1.12.

Comparison 1 Vaginal misoprostol versus placebo, Outcome 12 Vaginal bleeding 2 weeks after treatment.

Analysis 1.13.

Comparison 1 Vaginal misoprostol versus placebo, Outcome 13 Satisfaction with treatment.

Comparison 2.

Vaginal misoprostol versus surgical evacuation of uterus

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Surgical evacuation of uterus | 3 | 254 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.34, 0.52] |

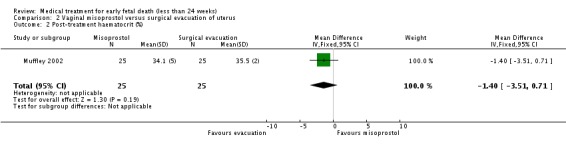

| 2 Post‐treatment haematocrit (%) | 1 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.40 [‐3.51, 0.71] |

| 3 Nausea | 1 | 154 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 21.85 [1.31, 364.37] |

| 4 Pain relief | 1 | 154 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.42 [0.82, 2.46] |

| 5 Diarrhoea | 1 | 154 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 40.85 [2.52, 662.57] |

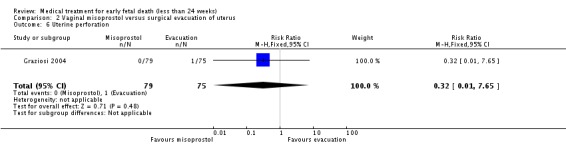

| 6 Uterine perforation | 1 | 154 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.32 [0.01, 7.65] |

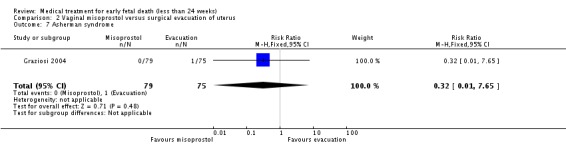

| 7 Asherman syndrome | 1 | 154 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.32 [0.01, 7.65] |

Analysis 2.1.

Comparison 2 Vaginal misoprostol versus surgical evacuation of uterus, Outcome 1 Surgical evacuation of uterus.

Analysis 2.2.

Comparison 2 Vaginal misoprostol versus surgical evacuation of uterus, Outcome 2 Post‐treatment haematocrit (%).

Analysis 2.3.

Comparison 2 Vaginal misoprostol versus surgical evacuation of uterus, Outcome 3 Nausea.

Analysis 2.4.

Comparison 2 Vaginal misoprostol versus surgical evacuation of uterus, Outcome 4 Pain relief.

Analysis 2.5.

Comparison 2 Vaginal misoprostol versus surgical evacuation of uterus, Outcome 5 Diarrhoea.

Analysis 2.6.

Comparison 2 Vaginal misoprostol versus surgical evacuation of uterus, Outcome 6 Uterine perforation.

Analysis 2.7.

Comparison 2 Vaginal misoprostol versus surgical evacuation of uterus, Outcome 7 Asherman syndrome.

Comparison 3.

Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal gemeprost

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Miscarriage < 24 hours | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.24 [0.90, 1.70] |

| 1.2 Gestation 13‐24 weeks | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.24 [0.90, 1.70] |

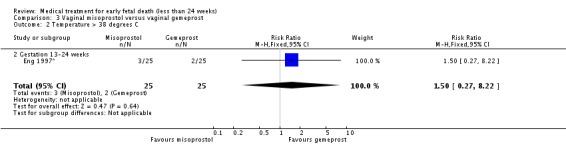

| 2 Temperature > 38 degrees C | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.5 [0.27, 8.22] |

| 2.2 Gestation 13‐24 weeks | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.5 [0.27, 8.22] |

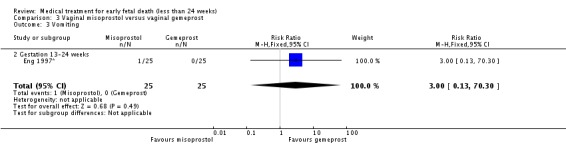

| 3 Vomiting | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 70.30] |

| 3.2 Gestation 13‐24 weeks | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 70.30] |

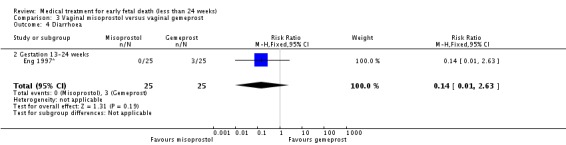

| 4 Diarrhoea | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.14 [0.01, 2.63] |

| 4.2 Gestation 13‐24 weeks | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.14 [0.01, 2.63] |

| 5 Opiate analgesia | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5.2 Gestation 13‐24 weeks | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Analysis 3.1.

Comparison 3 Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal gemeprost, Outcome 1 Miscarriage < 24 hours.

Analysis 3.2.

Comparison 3 Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal gemeprost, Outcome 2 Temperature > 38 degrees C.

Analysis 3.3.

Comparison 3 Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal gemeprost, Outcome 3 Vomiting.

Analysis 3.4.

Comparison 3 Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal gemeprost, Outcome 4 Diarrhoea.

Analysis 3.5.

Comparison 3 Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal gemeprost, Outcome 5 Opiate analgesia.

Comparison 4.

Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal prostaglandin E1/2

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Surgical evacuation | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.39 [0.21, 0.72] |

| 2 Blood transfusion | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 6.07 [0.30, 121.33] |

| 3 Hospital stay (days) | 1 | 60 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.38 [‐3.36, ‐1.40] |

| 4 Complete miscarriage | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.44 [1.06, 1.96] |

| 5 Nausea | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.28, 3.78] |

Analysis 4.1.

Comparison 4 Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal prostaglandin E1/2, Outcome 1 Surgical evacuation.

Analysis 4.2.

Comparison 4 Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal prostaglandin E1/2, Outcome 2 Blood transfusion.

Analysis 4.3.

Comparison 4 Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal prostaglandin E1/2, Outcome 3 Hospital stay (days).

Analysis 4.4.

Comparison 4 Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal prostaglandin E1/2, Outcome 4 Complete miscarriage.

Analysis 4.5.

Comparison 4 Vaginal misoprostol versus vaginal prostaglandin E1/2, Outcome 5 Nausea.

Comparison 5.

Vaginal misoprostol lower versus higher dose regimens

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Miscarriage | 3 | 247 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.72, 1.00] |

| 1.1 400 mcg versus 600 mcg | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.87, 1.26] |

| 1.2 400 mcg versus 800 mcg | 1 | 33 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.45, 1.31] |

| 1.3 600 mcg versus 800 mcg | 1 | 114 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.48, 0.93] |

| 2 Fever | 2 | 214 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.41, 1.30] |

| 3 Nausea | 2 | 214 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.31, 1.41] |

| 4 Diarrhoea | 2 | 214 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.54 [0.15, 1.91] |

Analysis 5.1.

Comparison 5 Vaginal misoprostol lower versus higher dose regimens, Outcome 1 Miscarriage.

Analysis 5.2.

Comparison 5 Vaginal misoprostol lower versus higher dose regimens, Outcome 2 Fever.

Analysis 5.3.

Comparison 5 Vaginal misoprostol lower versus higher dose regimens, Outcome 3 Nausea.

Analysis 5.4.

Comparison 5 Vaginal misoprostol lower versus higher dose regimens, Outcome 4 Diarrhoea.

Comparison 6.

Vaginal misoprostol wet versus dry vaginal preparations

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Miscarriage < 3 days | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.85, 1.54] |

| 2 Miscarriage < 8 days | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.84, 1.29] |

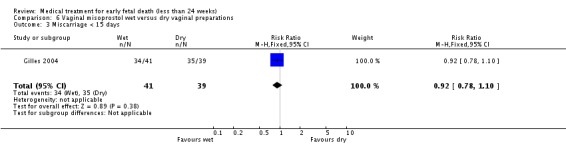

| 3 Miscarriage < 15 days | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.78, 1.10] |

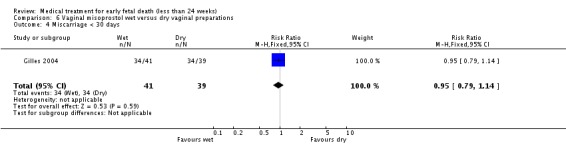

| 4 Miscarriage < 30 days | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.79, 1.14] |

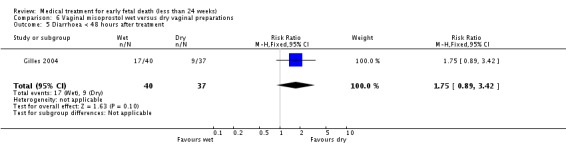

| 5 Diarrhoea < 48 hours after treatment | 1 | 77 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.75 [0.89, 3.42] |

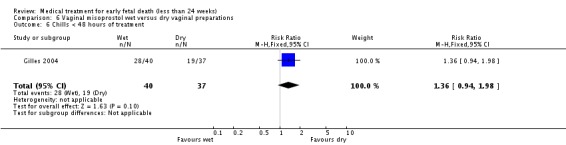

| 6 Chills < 48 hours of treatment | 1 | 77 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.36 [0.94, 1.98] |

| 7 Vomiting < 48 hours of treatment | 1 | 77 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.33, 2.62] |

| 8 Would wish/probably wish same treatment in future nonviable pregnancy | 1 | 73 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.93, 1.49] |

Analysis 6.1.

Comparison 6 Vaginal misoprostol wet versus dry vaginal preparations, Outcome 1 Miscarriage < 3 days.

Analysis 6.2.

Comparison 6 Vaginal misoprostol wet versus dry vaginal preparations, Outcome 2 Miscarriage < 8 days.

Analysis 6.3.

Comparison 6 Vaginal misoprostol wet versus dry vaginal preparations, Outcome 3 Miscarriage < 15 days.

Analysis 6.4.

Comparison 6 Vaginal misoprostol wet versus dry vaginal preparations, Outcome 4 Miscarriage < 30 days.

Analysis 6.5.

Comparison 6 Vaginal misoprostol wet versus dry vaginal preparations, Outcome 5 Diarrhoea < 48 hours after treatment.

Analysis 6.6.

Comparison 6 Vaginal misoprostol wet versus dry vaginal preparations, Outcome 6 Chills < 48 hours of treatment.

Analysis 6.7.

Comparison 6 Vaginal misoprostol wet versus dry vaginal preparations, Outcome 7 Vomiting < 48 hours of treatment.

Analysis 6.8.

Comparison 6 Vaginal misoprostol wet versus dry vaginal preparations, Outcome 8 Would wish/probably wish same treatment in future nonviable pregnancy.

Comparison 7.

Vaginal misoprostol + methotrexate versus vaginal misoprostol alone

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Miscarriage not complete | 1 | 21 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.26 [0.01, 5.65] |

| 4 Additional surgical evacuation | 1 | 21 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.26 [0.01, 5.65] |

| 5 Haemorrhage | 1 | 21 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.31 [0.10, 50.85] |

| 6 Pain relief | 1 | 21 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.25, 2.22] |

Analysis 7.1.

Comparison 7 Vaginal misoprostol + methotrexate versus vaginal misoprostol alone, Outcome 1 Miscarriage not complete.

Analysis 7.4.

Comparison 7 Vaginal misoprostol + methotrexate versus vaginal misoprostol alone, Outcome 4 Additional surgical evacuation.

Analysis 7.5.

Comparison 7 Vaginal misoprostol + methotrexate versus vaginal misoprostol alone, Outcome 5 Haemorrhage.

Analysis 7.6.

Comparison 7 Vaginal misoprostol + methotrexate versus vaginal misoprostol alone, Outcome 6 Pain relief.

Comparison 8.

Vaginal misoprostol plus laminaria tents versus vaginal misoprostol alone

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Miscarriage < 24 hours | 1 | 38 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.65, 1.25] |

| 2 Miscarriage < 48 hours | 1 | 38 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.88, 1.29] |

Analysis 8.1.

Comparison 8 Vaginal misoprostol plus laminaria tents versus vaginal misoprostol alone, Outcome 1 Miscarriage < 24 hours.

Analysis 8.2.

Comparison 8 Vaginal misoprostol plus laminaria tents versus vaginal misoprostol alone, Outcome 2 Miscarriage < 48 hours.

Comparison 9.

Oral misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Complete miscarriage | 2 | 218 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.82, 0.99] |

| 1.1 400 mcg oral misoprostol versus 800 mcg vaginal misoprostol | 1 | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.29 [0.10, 0.79] |

| 1.2 800 mcg oral misoprostol versus 800 mcg vaginal misoprostol | 1 | 198 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.88, 1.05] |

| 2 Vomiting | 1 | 190 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.29 [0.10, 0.84] |

| 9 Nausea | 1 | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.37, 1.74] |

| 10 Diarrhoea | 2 | 210 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.67, 1.66] |

| 12 Pain (visual analogue scale) | 1 | 18 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.90 [‐4.82, 1.02] |

| 13 Fever | 1 | 190 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.36, 2.74] |

| 14 Women's satisfaction with treatment | 1 | 198 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.86, 1.06] |

| 15 Time to delivery (hours) | 1 | 70 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.1 [2.64, 5.56] |

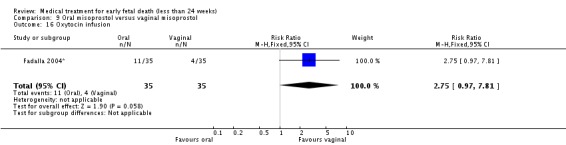

| 16 Oxytocin infusion | 1 | 70 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.75 [0.97, 7.81] |

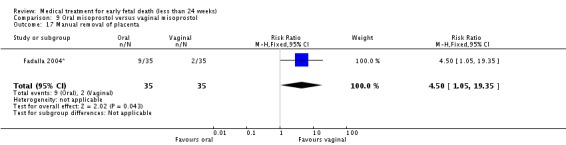

| 17 Manual removal of placenta | 1 | 70 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.5 [1.05, 19.35] |

Analysis 9.1.

Comparison 9 Oral misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol, Outcome 1 Complete miscarriage.

Analysis 9.2.

Comparison 9 Oral misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol, Outcome 2 Vomiting.

Analysis 9.9.

Comparison 9 Oral misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol, Outcome 9 Nausea.

Analysis 9.10.

Comparison 9 Oral misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol, Outcome 10 Diarrhoea.

Analysis 9.12.

Comparison 9 Oral misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol, Outcome 12 Pain (visual analogue scale).

Analysis 9.13.

Comparison 9 Oral misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol, Outcome 13 Fever.

Analysis 9.14.

Comparison 9 Oral misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol, Outcome 14 Women's satisfaction with treatment.

Analysis 9.15.

Comparison 9 Oral misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol, Outcome 15 Time to delivery (hours).

Analysis 9.16.

Comparison 9 Oral misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol, Outcome 16 Oxytocin infusion.

Analysis 9.17.

Comparison 9 Oral misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol, Outcome 17 Manual removal of placenta.

Comparison 10.

Oral misoprostol + mifepristone versus expectant management

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Empty uterine cavity at day 5 | 1 | 122 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.90, 1.30] |

| 2 Urgent surgical evacuation for bleeding | 1 | 122 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.01, 8.29] |

| 3 Pelvic inflammatory disease | 1 | 122 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.52 [0.05, 5.55] |

| 4 Pain (visual analogue scale day 5) | 1 | 122 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.10 [‐5.92, 14.12] |

| 5 Sick leave (days) | 1 | 122 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.8 [0.63, 2.97] |

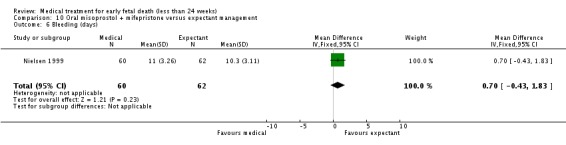

| 6 Bleeding (days) | 1 | 122 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [‐0.43, 1.83] |

| 7 Satisfaction with treatment (visual analogue scale day 14) | 1 | 122 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.40 [‐5.54, 12.34] |

Analysis 10.1.

Comparison 10 Oral misoprostol + mifepristone versus expectant management, Outcome 1 Empty uterine cavity at day 5.

Analysis 10.2.

Comparison 10 Oral misoprostol + mifepristone versus expectant management, Outcome 2 Urgent surgical evacuation for bleeding.

Analysis 10.3.

Comparison 10 Oral misoprostol + mifepristone versus expectant management, Outcome 3 Pelvic inflammatory disease.

Analysis 10.4.

Comparison 10 Oral misoprostol + mifepristone versus expectant management, Outcome 4 Pain (visual analogue scale day 5).

Analysis 10.5.

Comparison 10 Oral misoprostol + mifepristone versus expectant management, Outcome 5 Sick leave (days).

Analysis 10.6.

Comparison 10 Oral misoprostol + mifepristone versus expectant management, Outcome 6 Bleeding (days).

Analysis 10.7.

Comparison 10 Oral misoprostol + mifepristone versus expectant management, Outcome 7 Satisfaction with treatment (visual analogue scale day 14).

Comparison 11.

Sublingual misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Complete miscarriage | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.85, 1.18] |

| 2 Nausea | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.2 [0.80, 1.79] |

| 3 Vomiting | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.32, 1.88] |

| 4 Diarrhoea | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.55 [1.48, 4.38] |

| 5 Haemoglobin day 43 | 1 | 80 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.10 [‐0.38, 0.58] |

| 6 Intolerable pain | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.29, 1.97] |

| 7 Satisfied with treatment | 1 | 77 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.79, 1.25] |

Analysis 11.1.

Comparison 11 Sublingual misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol, Outcome 1 Complete miscarriage.

Analysis 11.2.

Comparison 11 Sublingual misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol, Outcome 2 Nausea.

Analysis 11.3.

Comparison 11 Sublingual misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol, Outcome 3 Vomiting.

Analysis 11.4.

Comparison 11 Sublingual misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol, Outcome 4 Diarrhoea.

Analysis 11.5.

Comparison 11 Sublingual misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol, Outcome 5 Haemoglobin day 43.

Analysis 11.6.

Comparison 11 Sublingual misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol, Outcome 6 Intolerable pain.

Analysis 11.7.

Comparison 11 Sublingual misoprostol versus vaginal misoprostol, Outcome 7 Satisfied with treatment.

Comparison 12.

Mifepristone versus placebo

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Miscarriage < 48 hours | 1 | 46 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.0 [0.25, 98.75] |

| 2 Miscarriage < 3 days | 1 | 46 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 19.0 [1.17, 308.40] |

| 3 Miscarriage < 4 days | 1 | 46 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 14.0 [2.00, 97.88] |

| 4 Miscarriage < 5 days | 1 | 46 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 9.5 [2.49, 36.19] |

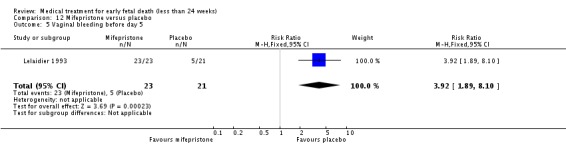

| 5 Vaginal bleeding before day 5 | 1 | 44 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.92 [1.89, 8.10] |

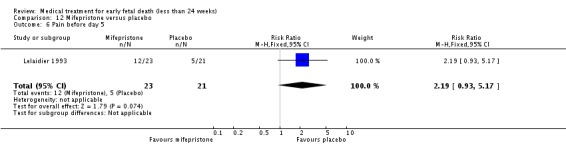

| 6 Pain before day 5 | 1 | 44 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.19 [0.93, 5.17] |

Analysis 12.1.

Comparison 12 Mifepristone versus placebo, Outcome 1 Miscarriage < 48 hours.

Analysis 12.2.

Comparison 12 Mifepristone versus placebo, Outcome 2 Miscarriage < 3 days.

Analysis 12.3.

Comparison 12 Mifepristone versus placebo, Outcome 3 Miscarriage < 4 days.

Analysis 12.4.

Comparison 12 Mifepristone versus placebo, Outcome 4 Miscarriage < 5 days.

Analysis 12.5.

Comparison 12 Mifepristone versus placebo, Outcome 5 Vaginal bleeding before day 5.

Analysis 12.6.

Comparison 12 Mifepristone versus placebo, Outcome 6 Pain before day 5.

Comparison 13.

Vaginal gemeprost versus surgical evacuation of uterus

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

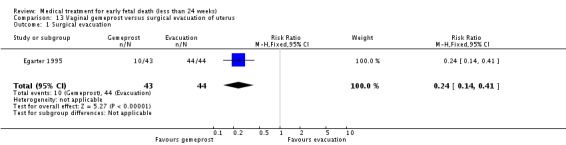

| 1 Surgical evacuation | 1 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.24 [0.14, 0.41] |

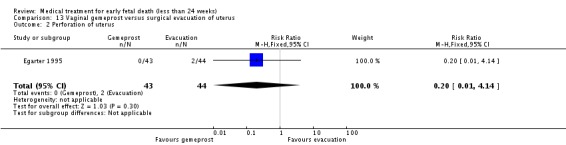

| 2 Perforation of uterus | 1 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.20 [0.01, 4.14] |

| 3 Nausea | 1 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.79 [0.56, 5.68] |

Analysis 13.1.

Comparison 13 Vaginal gemeprost versus surgical evacuation of uterus, Outcome 1 Surgical evacuation.

Analysis 13.2.

Comparison 13 Vaginal gemeprost versus surgical evacuation of uterus, Outcome 2 Perforation of uterus.

Analysis 13.3.

Comparison 13 Vaginal gemeprost versus surgical evacuation of uterus, Outcome 3 Nausea.

What's new

Last assessed as up‐to‐date: 24 April 2006.

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 8 August 2012 | Amended | Search updated. One hundred reports added to Studies awaiting classification. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2000 Review first published: Issue 3, 2006

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 18 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Differences between protocol and review

The protocol for this review aimed to include both trials for treatment of both ultrasound diagnosed non‐viable pregnancies and incomplete miscarriage. For the reasons described in the review, two separate reviews now address these topics ‐ thus, the change in title from 'Medical management for miscarriage'.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Al Inizi 2003

| Methods | 'Random allocation'. Details unknown. | |

| Participants | 60 women with early non‐viable pregnancies diagnosed by ultrasound. | |

| Interventions | Vaginal misoprostol 400 mcg repeated twice a day to maximum of 1600 mcg (n = 27) versus dinoprostone (PGE2) vaginal tablets repeated 6 hourly intervals to maximum of 36 mg (n = 33). | |

| Outcomes | Complete miscarriage/need for surgical evacuation. | |

| Notes | Authors contacted. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Autry 1999

| Methods | Randomisation using a random number tables. Allocation concealment was accomplished in sequentially numbered opaque sealed envelopes made available at the time of enrollment in the study. Intention to treat analysis. | |

| Participants | 21 women diagnosed with a non‐viable first trimester intrauterine pregnancy up to 49 days gestation. Evidence of non‐viability included one of the following findings on TVS: 1) mean gestational sac diameter greater than 18 mm and no embryonic pole; 2) embryonic pole 5‐10 mm without cardiac activity; 3) intrauterine gestational sac with abnormal hCG titers. Others entry criteria: 1) 18 years of age or greater; 2) closed cervix on digital exam; 3) no known intolerance or allergy to misoprostol or MTX; 4) hemoglobin of 9 g/dl or greater; 5) platelet count of 100,000/mcl or greater; 6) no history of blood clotting disorders; 7) no active liver or renal disease; 8) ability and willingness to comply with visit schedule; 9) hCG less than 40 000 IU/l; and 10) easy access to a telephone and transportation. | |

| Interventions | Combined group (n = 12): IM MTX 50 mg/m2 body surface area (day 1) followed two days later (day 3) by vaginal misoprostol 800 mcg (by vaginal placement of four 200 mcg‐tablets of misoprostol). If the gestational sac was present vaginal misoprostol was repeated. Misoprostol only group (n = 9): four 200 mcg‐tablets placed in the vagina on day 1. The remainder of the follow up was similar to that for combined group. | |

| Outcomes | Successful complete abortion: MTX plus misoprostol 12/12 vs misoprostol only 8/9. No blood transfusion or antibiotics. Positive urine pregnancy test at the initial follow‐up appointment: 2/9 vs 7/7. Pain relief: 4/12 vs 4/9. | |

| Notes | Wisconsin, Milwaukee, USA. All women received: 1) prescription for 10 tablets acetaminophen with codeine (300 mg/30 mg) and 8 tablets of ibuprofen (600 mg); 2) instruction sheet including phone number to contact physician 24 hours/day; and a diary sheet to record symptoms, side‐effects, and pain medication use. Data about side‐effects (headache, nausea and emesis) and women's satisfaction reported as no separate data. Authors conclude that both treatments are effective regimens for the complete evacuation of non‐viable early first trimester pregnancy, and represent a reasonable alternative for women wishing to avoid surgery. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Bagratee 2004

| Methods | Computer‐generated random allocation of study number. Numbered envelopes containing misoprostol or placebo. | |

| Participants | 104 women who attended Early Pregnancy Unit, St Mary's Hospital, with incomplete miscarriage or early pregnancy failure < 13 weeks. | |

| Interventions | 600 mcg misoprostol (n = 52) or placebo [expectant management] (n = 52). Second dose next day unless complete miscarriage had occurred in meantime. Review day 7 and surgical evacuation if miscarriage not complete. Further review at day 14. | |

| Outcomes | Primary: complete miscarriage without need for ERPC by day 7. Secondary outcomes: clinical, side‐effects, satisfaction and future choices. | |

| Notes | Primary outcome reported for both non‐viable pregnancies and incomplete miscarriages, but not for secondary outcomes. These will be added if authors can provide data separately for non‐viable pregnancies and incomplete miscarriages. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Creinin 1997

| Methods | Sealed, numbered, sequential envelopes containing instructions based on computer‐generated random number table. | |

| Participants | 20 women with non‐viable pregnancies diagnosed by transvaginal ultrasound; < 9 weeks; closed cervix; no contra‐indication to misoprostol; no heavy bleeding. | |

| Interventions | 400 mcg misoprostol orally, repeated after 24 hours if the pregnancy had not been expelled (n = 12); vaginal misoprostol 800 mcg ‐ repeated after 24 hours if necessary (as above) (n = 8). Surgical evacuation offered to women in both groups after 48 hours if treatment unsuccessful. | |

| Outcomes | Miscarriage; pain (visual analogue scale); side‐effects. | |

| Notes | Pilot study. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Demetroulis 2001

| Methods | Randomisation by opening sealed opaque envelope containing computer generated allocation code number. No attempt at masking given the manifest differences between medical and surgical interventions. | |

| Participants | 80 women with incomplete miscarriage or anembryonic pregnancy or missed miscarriage < 13 weeks, diagnosed by ultrasound. The data in this review are derived only from the subgroup with non‐viable pregnancies (n = 50) and not those with incomplete miscarriages. Women were reviewed 8‐10 hours after medical treatment; if they had empty uteruses on ultrasound examination they were discharged home; if not, surgical evacuation was arranged. | |

| Interventions | Vaginal misoprostol 800 mcg once only (n = 26) versus surgical evacuation of the uterus (n = 24). | |

| Outcomes | Need for surgical evacuation, symptoms including pain and bleeding, 'satisfaction'. | |

| Notes | Authors contacted for information on outcomes according to indication for treatment. Only usable data currently available are on incidence of surgical evacuation. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Egarter 1995

| Methods | Women "randomly assigned"; no details. | |

| Participants | 87 women in Austria with non‐viable pregnancies between 8 and 12 weeks, diagnosed by ultrasound. | |

| Interventions | Vaginal gemeprost 1 mg every 3 hours up to maximum of 3 mg daily for 2 days (n = 43) versus uterine curettage (n = 44). | |

| Outcomes | Need for surgical curettage. Adverse effects. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Eng 1997*

| Methods | Randomised by "blindly picking a sealed number from a box". Treatment allocation was then based on whether the number was odd or even. | |

| Participants | 50 women with intrauterine fetal death at 13‐26 weeks of pregnancy. | |

| Interventions | Vaginal misoprostol 200 mcg 3‐hourly up to a maximum dose of 1200 mcg (n = 25) versus vaginal gemeprost 1 mg 3‐hourly up to a maximum dose of 5 mg (n = 25). | |

| Outcomes | Main outcome ‐ "treatment failure" defined as failure to miscarry within 24 hours, or side‐effects severe enough to preclude use of additional dose of drug. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Fadalla 2004*

| Methods | "Randomised"; no details. | |

| Participants | 70 women in the Wad Medeni Teaching Hospital, Sudan, with fetal deaths between 13 and 28 weeks, diagnosed by ultrasound. | |

| Interventions | Oral misoprostol (n = 35) versus vaginal misoprostol (n = 35) ‐ both administered as 100 mcg tablets 4‐hourly until initiation of labour. | |

| Outcomes | Time to delivery; oxytocin infusion; manual removal of placenta. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Gilles 2004

| Methods | Random allocation by computer‐automated telephone response system. Stratification by pregnancy type. Random permuted blocks of size 4 or 8. | |

| Participants | 80 women with anembryonic pregnancy < 46 mm sac diameter or embryonic/fetal death with crown‐rump length < 41 mm. Four centres. | |

| Interventions | "Wet misoprostol" 800 mcg + 2 ml saline vaginally (n = 41) versus "dry misoprostol" (as above without saline) (n = 39). Second dose given day 3 if no miscarriage. | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: miscarriage without need for curettage before 30 days. Secondary outcomes: miscarriage < 3, < 8 and < 15 days; side‐effects, women's views. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Graziosi 2004

| Methods | Consent for study obtained at time of diagnosis of early pregnancy failure. Randomised after at least one week of expectant management. Computer programme with block randomisation sequence. Stratification by previous vaginal birth; Gestational age < or > 10 weeks; centre. | |

| Participants | 154 women with ultrasound‐diagnosed early pregnancy failure ‐ either anembryonic pregnancy or fetal death at 6‐14 weeks. 6 centre study in Netherlands. | |

| Interventions | Vaginal misoprostol 800 mcg; repeated after 24 hours if ultrasound indicated remaining tissue in the uterus. Curettage after 3 days if miscarriage hadn't occurred or was incomplete (n = 79) or suction curettage within a week of randomisation (n = 75). | |

| Outcomes | Primary: complete evacuation. Secondary: side‐effects, pain and need for analgesia, intensity/duration of bleeding. | |

| Notes | Of 241 eligible women, 87 (36%) declined to participate and chose curettage. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Heard 2002

| Methods | "Randomized" ‐ no details. | |

| Participants | 33 women with "missed abortion". | |

| Interventions | Vaginal misoprostol 400 mcg (n = 12) versus 800 mcg (n = 21). | |

| Outcomes | Only usable outcome reported in abstract was miscarriage. | |

| Notes | Abstract ‐ no explanation for unbalanced numbers. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Herabutya 1997

| Methods | "Random allocation" but method not discussed in paper. | |

| Participants | 84 women with ultrasound confirmation of fetal death with uterine size < 14 weeks, no bleeding, and cervix closed. | |

| Interventions | Misoprostol (200 micrograms vaginally) (n = 42) or vaginal placebo (n = 42) on admission to hospital. | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome was miscarriage within 24 hours of treatment. Some information available on complications. | |

| Notes | Much of the outcome data reported describes only the subgroups who did miscarry before surgical evacuation. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Jain 1996*

| Methods | "Random number table". | |

| Participants | 70 women in Los Angeles, USA, with either fetal death (n = 40) or medical or genetic indications for termination of pregnancy (n = 30) at 12‐22 weeks. Only data from pregnancies complicated by fetal death included here. | |

| Interventions | Vaginal misoprostol 200 mcg 12‐hourly plus laminaria tents (n = 20) versus vaginal misoprostol 200 mcg 12‐hourly alone. | |

| Outcomes | Miscarriage. | |

| Notes | Adverse effects are described for the groups as wholes, so are not included here. 2 women excluded from analyses ‐ 1 protocol violation; 1 was found to have interstitial ectopic pregnancy. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Kara 1999*

| Methods | "Random allocation". No details. | |

| Participants | 65 women in Istanbul, Turkey, with ultrasound‐diagnosed fetal death in second trimester. | |

| Interventions | Vaginal misoprostol 200 mcg (n = 32) versus intracervical dinoproston 0.5 mg (n = 33). Intravenous oxytocin started after 6 hours if no 'effective contractions'. | |

| Outcomes | Complete miscarriage. Adverse effects. | |

| Notes | Misoprostol dose reported as 200 mg. Assumed to be 200 mcg. Time to miscarriage not included as standard deviations seem incorrect. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Kovavisarach 2002

| Methods | "Random allocation". Method not discussed. | |

| Participants | 54 women with anembryonic pregnancies < 12 weeks diagnosed by TVS. Single centre study in Bangkok, Thailand. | |

| Interventions | Vaginal misoprostol 400 mcg (n = 27) or placebo (n = 27). Reviewed after 24 hours and curettage offered if no or incomplete miscarriage. Further review after 1 week. | |

| Outcomes | Primary: complete miscarriage within 24 hours of treatment. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Kovavisarach 2005

| Methods | Random allocation using sealed, sequentially numbered envelopes, prepared using published table of random numbers. | |

| Participants | 114 women in Bangkok, Thailand, with non‐viable pregnancies (anembryonic or fetal deaths) at < 12 weeks, diagnosed by TVS. Women with open cervices were not eligible for recruitment. | |

| Interventions | Vaginal misoprostol 600 mcg (n = 57) or 800 mcg (n = 57). If complete miscarriage not effected within 24 hours, or if clinical circumstances dictated (pain, bleeding), uterine curettage was performed. | |

| Outcomes | Primary: complete miscarriage without need for uterine curettage within 24 hours. Secondary: adverse effects. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Lelaidier 1993

| Methods | Drug or identical placebo supplied by pharmacy using randomisation list using permutation blocks of four. | |

| Participants | 46 women with non‐viable pregnancies diagnosed by ultrasound on two examinations separated by one week. < 14 weeks. No bleeding or pain. | |

| Interventions | Mifepristone 600 mg orally (n = 23) or placebo (n = 23). All women were reviewed after 5 days and if miscarriage had not occurred, surgical evacuation was performed that day. | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome was expulsion of the pregnancy. Symptoms also recorded. | |

| Notes | Two women in the placebo group underwent surgical evacuation by private practitioners before 5th day review. Both were in the process of miscarriage and were classed as expulsion positive; no information available on symptoms. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Lister 2005

| Methods | Random allocation ‐ blocked and stratified by physician office and by day of recruitment ‐ day of diagnosis, or after day of diagnosis. | |

| Participants | 34 women in Columbus, Ohio, USA, with early pregnancy failure (anembryonic pregnancies or early fetal deaths) diagnosed by TVS. | |

| Interventions | Vaginal misoprostol 800 mcg, repeated after 24 hours if sac still present on TVS (n = 18) or placebo (n = 16). | |

| Outcomes | Primary: miscarriage complete at 48 hours. | |

| Notes | Planned sample size 84 but trial stopped after interim analysis of first 36 women. Two women excluded from analysis ‐ one protocol violation; one did not meet entry criteria. Two women did not come for assessment 2 weeks after initial treatment. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Muffley 2002

| Methods | Computer‐generated random number table with blocked permutations ‐ group assignments recorded in sealed opaque numbered envelopes. | |

| Participants | 50 women with non‐viable pregnancies diagnosed by ultrasound (anembryonic or embryonic/fetal deaths) < 12 weeks. Exclusions: excessive bleeding, anaemia, unstable vital signs, coagulopathy, asthma or other contra‐indication to prostaglandin treatment, infection, open cervix. | |

| Interventions | 800 mcg misoprostol vaginally, repeated after 24 hours if ultrasound showed tissue still present in uterus; final review after further 24 hours ‐ if tissue still present, surgical evacuation performed (n = 25). Suction curettage (n = 25). | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: miscarriage. | |

| Notes | Analysis by intention to treat. Details about nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea reported only for misoprostol group. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Ngoc 2004

| Methods | Randomised by opening sequentially numbered envelope ‐ prepared by computer‐generated code in blocks of 10. | |

| Participants | 200 women in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, with non‐viable first trimester pregnancies (anembryonic or early fetal death) diagnosed by ultrasound; cervix closed. | |

| Interventions | Oral misoprostol 800 mcg (n = 100) versus vaginal misoprostol 800 mcg (n = 98). Women reviewed after 48 hours; if retained products present, they were given option of surgical evacuation or further review after another 5 days (when evacuation was performed if there were still products present). | |

| Outcomes | Primary: complete miscarriage without need for surgical evacuation. Secondary: adverse effects. | |

| Notes | 2 women lost to follow up. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Nielsen 1999

| Methods | Randomisation method not discussed in paper. | |

| Participants | 122 women < 13 weeks with symptoms of threatened miscarriage (bleeding +/‐ pain), a closed cervix, and ultrasound demonstration of pregnancy non‐viability (anembryonic pregnancy n = 44; embryonic/fetal death n = 46; 'complex mass with deformed gestational sac' n = 32). Surgical evacuation at day 5 if transvaginal ultrasound showed retained products > 15 mm diameter. | |

| Interventions | Mifepristone (400 mg orally) followed by oral misoprostol (400 micrograms) 48 hours later (n = 60) versus expectant management (n = 62). | |

| Outcomes | Clinical events; routine transvaginal ultrasound at 5 days to identify retained products; visual analogue scale to assess pain at day 5; visual analogue scale to assess satisfaction at day 14. | |

| Notes | Seeking clarification from authors if "complex mass with deformed gestational sac" represents missed or incomplete miscarriage. Data included in meantime. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Niromanesh 2005*

| Methods | Randomisation method not discussed in paper. | |

| Participants | 100 women in Tehran, Iran, with fetal deaths between 14 and 25 weeks. | |

| Interventions | Vaginal misoprostol: 400 mcg (n = 50) versus 600 mcg (n = 50) ‐ both 12‐hourly for 48 hours. | |

| Outcomes | Miscarriage; surgical evacuation; adverse effects. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Tang 2003

| Methods | Randomisation by "computer‐generated random numbers". | |

| Participants | 80 women with non‐viable pregnancies diagnosed by ultrasound < 13 weeks. | |

| Interventions | Group 1: 600 mcg misoprostol sublingually every 3 hours for maximum of 3 doses (n = 40); Group 2: 600 mcg misoprostol vaginally every 3 hours for maximum of 3 doses (n = 40). Women discharged home after completion of treatment and reassessed day 7 ‐ when surgical evacuation performed if gestation sac still present, or retained products of conception plus heavy bleeding. | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: complete miscarriage (defined as no need for surgical evacuation up until return of menstruation). | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Wood 2002

| Methods | Computer‐generated random number list in blocks. Pharmacy prepared numbered envelopes. Tablets not identical so placed by nurse in opaque vaginal introducer for physician to insert ‐ to maintain allocation concealment. | |

| Participants | 50 women with ultrasound diagnosed non‐viable pregnancies. Gestational age 7‐17 weeks but women not included if fetal size by ultrasound > 12 weeks equivalent. Also excluded from recruitment if experiencing uterine cramping or bleeding. | |

| Interventions | Misoprostol (800 mcg vaginally) (n = 25) or vaginal placebo (n = 25). If complete miscarriage not suspected after 24 hours, treatment was repeated. At 48 hours, if no miscarriage or miscarriage thought to be incomplete, uterine curettage was offered. | |

| Outcomes | Sample size based on reduction of uterine curettage from 50% to 10%. Women's satisfaction also assessed, but are not included in analyses as data not reported from control group. | |

| Notes | Analysis by intention to treat. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

ERPC: evacuation of retained products of conception hCG: human chorionic gonadotropin IM: intramuscular IU: international units mcg: microgrammes MTX: methotrexate POCs: products of conception TVS: transvaginal sonography vs: versus

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Abdel Fattah 1997 | Conference abstract. No information about gestational age but, given title, probably includes pregnancies > 24 weeks as well as < 24 weeks. |

| Almog 2005 | Termination of 'viable' pregnancies ‐ mainly with fetal anomalies. |

| Anderman 2000 | Conference abstract. Includes pregnancies > 24 weeks as well as < 24 weeks. |

| Avila‐Vergara 1997 | Intrauterine deaths mainly third trimester. |

| Bebbington 2002 | Termination of viable pregnancies. |

| Cabrol 1990 | Trial of mifepristone for induction of labour after intrauterine death ‐ but mainly late second and third trimester pregnancies. |

| Clevin 2001 | Abstract in Danish. A prospective, randomised study carried out to clarify the effect of vaginal administration of a prostaglandin E1 analogue (gemeprost) versus surgical management (curettage) on miscarriages at up to twelve weeks of gestation. Three groups: 1 (n = 27), 2A (n = 17) and 2B (n = 17) , allocated according the endometrial thickness. The measured outcomes were reduction of endometrial thickness, duration of vaginal bleeding and pain, reported in a non‐suitable format for analysis. |

| David 2003 | Randomised trial (details of randomisation unclear) of two methods to soften the cervix before surgical evacuation for early non‐viable pregnancies. No usable clinical data, given short timescale between treatment and surgery. |

| Dickinson 1998 | Trial included women with fetal malformations and maternal indications for pregnancy termination between 14 and 28 weeks, as well as pregnancies with fetal death. Data will be included for the latter if these can be obtained from the authors. |

| Dickinson 2002 | Trial included women with fetal malformations and maternal indications for pregnancy termination between 14 and 30 weeks, as well as pregnancies with fetal death. Data will be included for the latter if these can be obtained from the authors. |

| Dickinson 2003 | Randomised trial comparing oral with vaginal administration of misoprostol to terminate pregnancies with fetal malformations ‐ not non‐viable pregnancies. |

| Eppel 2005 | Trial included women with fetal malformations and maternal indications for pregnancy termination between 14 and 23 weeks, as well as pregnancies with fetal death. Data will be included for the latter if these can be obtained from the authors. |

| Feldman 2003 | Trial included women with fetal malformations and maternal indications for pregnancy termination between 14 and 23 weeks, as well as pregnancies with fetal death. Data will be included for the latter if these can be obtained from the authors. |

| Ghorab 1998 | Trial included women with fetal malformations for pregnancy termination, as well as pregnancies with fetal death. Data will be included for the latter if these can be obtained from the authors. |

| Gonzalez 2001 | Trial included women with fetal malformations and maternal indications for pregnancy termination between 14 and 23 weeks, as well as pregnancies with fetal death. Data will be included for the latter if these can be obtained from the authors. |

| Grimes 2004 | Trial included women with other reasons for pregnancy termination, as well as pregnancies with fetal death. Data will be included for the latter if these can be obtained from the authors. |

| Gronland 2002 | Not a randomised trial. Three centre study of women with non‐viable pregnancies comparing three treatment regimens: misoprostol, mifepristone + misoprostol, surgical evacuation ‐ with treatment regimen changing at each hospital every four months. |

| Hausler 1997 | Prospective randomised controlled trial evaluating three interventions for complete spontaneous abortion. Diagnosis was based on positive pregnant test, vaginal bleeding and/or evacuation of tissue from the vagina, a closed uterine orifice with only slight bleeding on admission and a possible clear sonographic pregnancy diagnosis in the history. Interventions: A) n = 15 curettage; B) n = 20 only controlled and; C) n = 15 additionally treated for 10 days with an oral hormone intake of 2 mg norethisterone acetate and 0.01 mg ethinyl oestradiol 3 x day. Randomisation by sealed unmarked envelopes. 63 patients were included in the study and allocated randomly to each group. 13 women (20.6%) were excluded from the study after randomisation: 10 did not report for the planned follow‐up control, one did not report for curettage, in one the height of the endometrium was > 8 mm and in one an ectopic pregnancy was diagnosed 6 days after the randomisation. The study only presents outcomes, in a non‐suitable format, regarding hCG clearing time and duration of the secondary haemorrhage from the day of randomisation. |

| Herabutya 2005 | RCT of misoprostol for terminating viable pregnancies. |

| Hidar 2001 | Trial included women with fetal malformations and maternal indications for pregnancy termination between 13 and 29 weeks, as well as pregnancies with fetal death. Data will be included for the latter if these can be obtained from the authors. |

| Hill 1991 | Trial includes fetal deaths in both second and third trimesters. |

| Hogg 2000 | Abstract. Trial included women with other reasons for pregnancy termination, as well as pregnancies with fetal death. Data will be included for the latter if these can be obtained from the authors. |

| Jain 1994 | Trial included women with fetal malformations and maternal indications for pregnancy termination between 12 and 22 weeks, as well as pregnancies with fetal death. Data will be included for the latter if these can be obtained from the authors. |

| Jain 1999 | Trial included women with fetal malformations and maternal indications for pregnancy termination between 12 and 22 weeks, as well as pregnancies with fetal death. Data will be included for the latter if these can be obtained from the authors. |

| Johnson 1997 | Randomised controlled trial evaluating pain and bleeding and comparing surgical to medical treatment. Surgical arm (n = 12) uterine curettage under general anesthesia. Medical arm (n = 17) include three different participant conditions and treatments: a) no treatment if women had a complete abortion and uterine cavity echo (nyometrium‐myometrium) less than 1.5 mm; b) women with incomplete abortion : 1 mg pessary of Gemeprost (Cervagem, May and Baker) and remained in hospital for 4 hours or until the had passed POC; and c) women with intact gestational sac (but non‐viable fetus) 200 mg RU 486 (mifepristone) and then allowed home, readmitted 36‐48 hours later for 1 mg of vaginal Cervagem. Data from each subgroup in the medical arm are not separated. The sample size is too small to detect any difference among such number of groups. |

| Kanhai 1989 | Includes both second and third trimester fetal deaths. |

| Lippert 1978 | Second and third trimester fetal deaths. Not obviously randomised. |

| Machtinger 2002 | Abstract. Appears to include both non‐viable pregnancies and miscarriages. Await full report. |

| Machtinger 2004 | Abstract. Appears to include both non‐viable pregnancies and miscarriages. Await full report. |

| Makhlouf 2003 | Not clear from paper if all pregnancies complicated by fetal death. Seeking clarification from authors. |

| Martin 1965 | Allocation based on alternation, not randomisation. Alternation violated. |

| Nakintu 2001 | Both second and third trimester fetal deaths. Seeking separate data from author. |

| Ngai 2001 | Includes data on women with both non‐viable pregnancies and incomplete miscarriages. If these data can be separated by the researchers, these data may be included in the future. |