Abstract

Background

Miscarriage occurs in 10% to 15% of pregnancies. The traditional treatment, after miscarriage, has been to perform surgery to remove any remaining placental tissues in the uterus ('evacuation of uterus'). However, medical treatments, or expectant care (no treatment), may also be effective, safe, and acceptable.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness, safety, and acceptability of any medical treatment for incomplete miscarriage (before 24 weeks).

Search methods

We searched Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth's Trials Register (13 May 2016) and reference lists of retrieved papers.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials comparing medical treatment with expectant care or surgery, or alternative methods of medical treatment. We excluded quasi‐randomised trials.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed the studies for inclusion, assessed risk of bias, and carried out data extraction. Data entry was checked. We assessed the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach.

Main results

We included 24 studies (5577 women). There were no trials specifically of miscarriage treatment after 13 weeks' gestation.

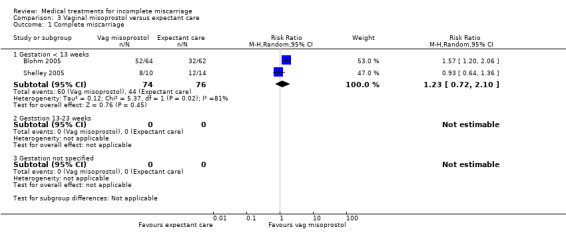

Three trials involving 335 women compared misoprostol treatment (all vaginally administered) with expectant care. There was no difference in complete miscarriage (average risk ratio (RR) 1.23, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.72 to 2.10; 2 studies, 150 women, random‐effects; very low‐quality evidence), or in the need for surgical evacuation (average RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.17 to 2.26; 2 studies, 308 women, random‐effects; low‐quality evidence). There were few data on 'deaths or serious complications'. For unplanned surgical intervention, we did not identify any difference between misoprostol and expectant care (average RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.17 to 2.26; 2 studies, 308 women, random‐effects; low‐quality evidence).

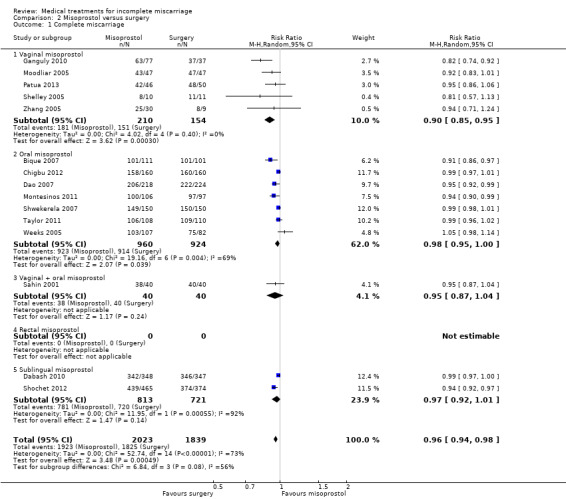

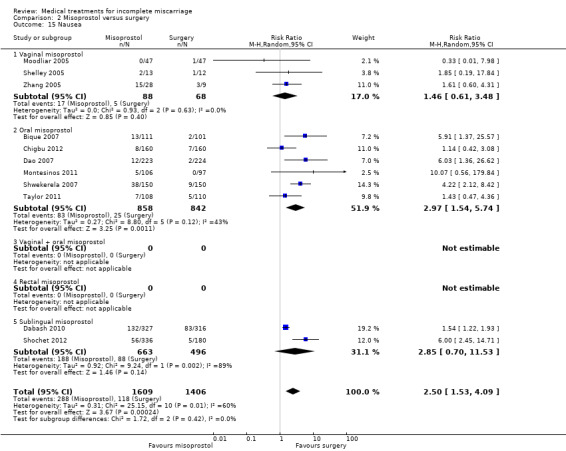

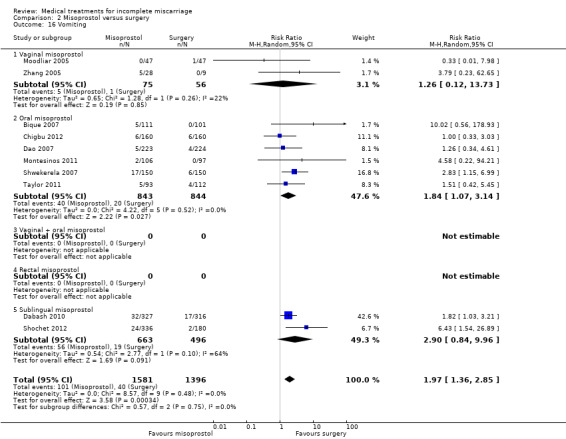

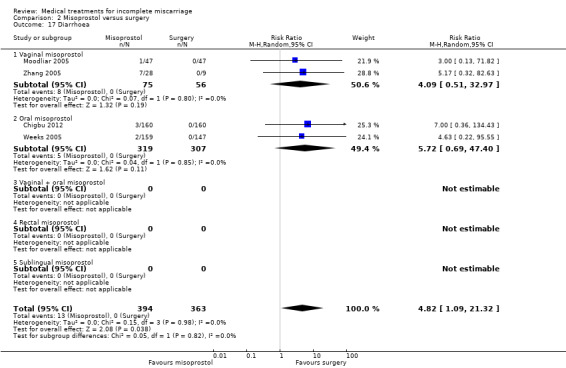

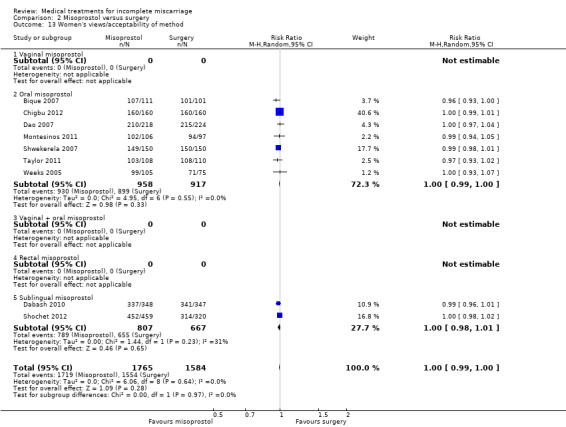

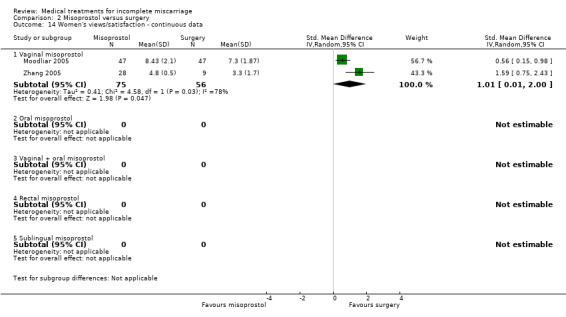

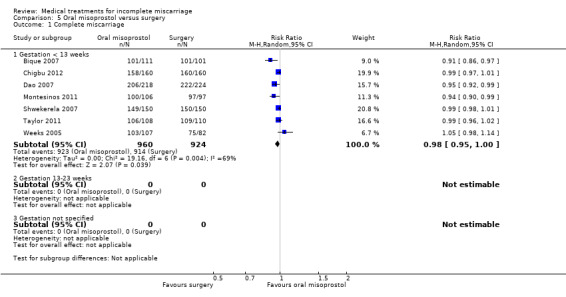

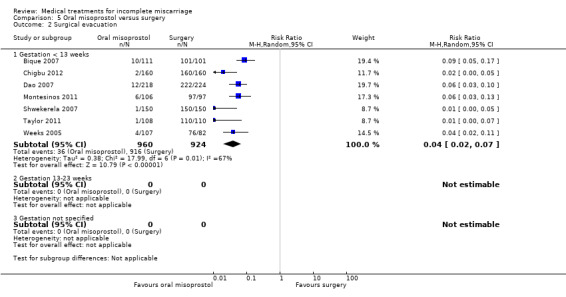

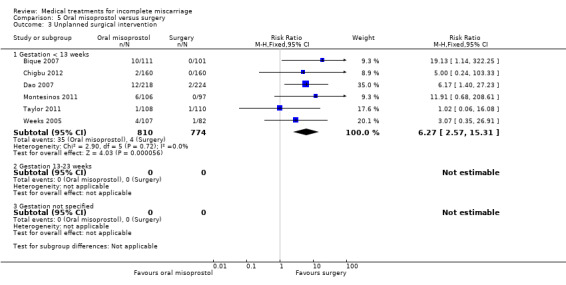

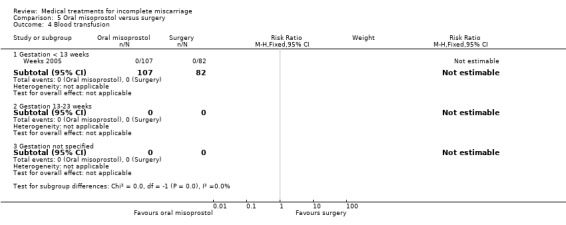

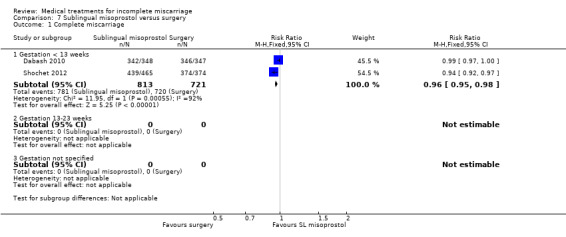

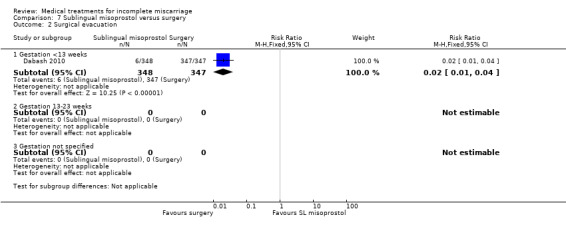

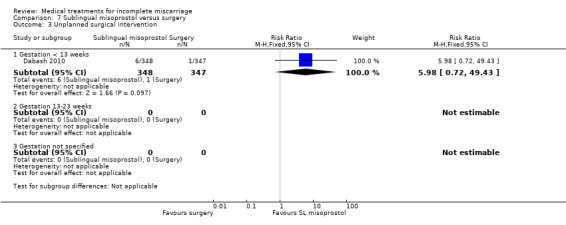

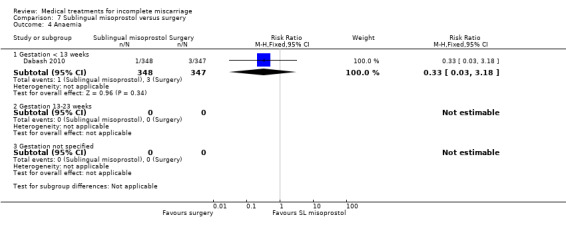

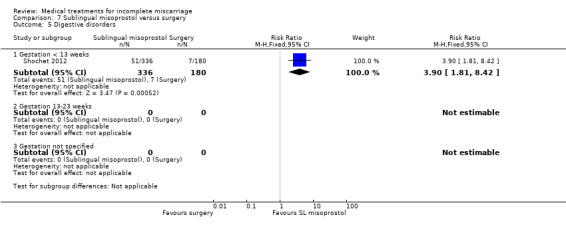

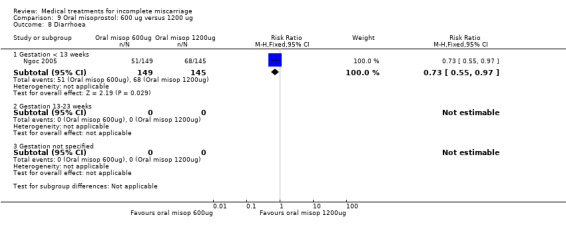

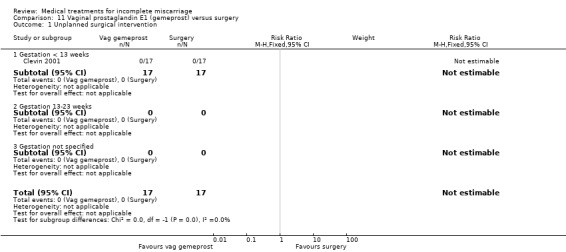

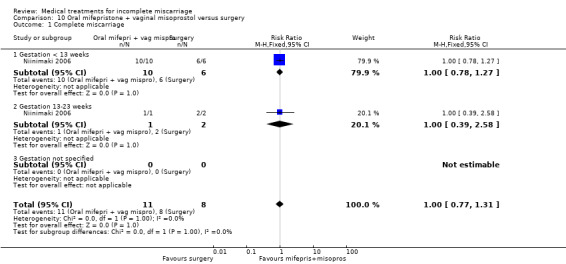

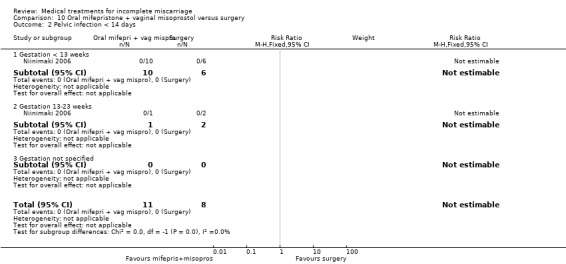

Sixteen trials involving 4044 women addressed the comparison of misoprostol (7 studies used oral administration, 6 studies used vaginal, 2 studies sublingual, 1 study combined vaginal + oral) with surgical evacuation. There was a slightly lower incidence of complete miscarriage with misoprostol (average RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.94 to 0.98; 15 studies, 3862 women, random‐effects; very low‐quality evidence) but with success rate high for both methods. Overall, there were fewer surgical evacuations with misoprostol (average RR 0.05, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.11; 13 studies, 3070 women, random‐effects; very low‐quality evidence) but more unplanned procedures (average RR 5.03, 95% CI 2.71 to 9.35; 11 studies, 2690 women, random‐effects; low‐quality evidence). There were few data on 'deaths or serious complications'. Nausea was more common with misoprostol (average RR 2.50, 95% CI 1.53 to 4.09; 11 studies, 3015 women, random‐effects; low‐quality evidence). We did not identify any difference in women's satisfaction between misoprostol and surgery (average RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.00; 9 studies, 3349 women, random‐effects; moderate‐quality evidence). More women had vomiting and diarrhoea with misoprostol compared with surgery (vomiting: average RR 1.97, 95% CI 1.36 to 2.85; 10 studies, 2977 women, random‐effects; moderate‐quality evidence; diarrhoea: average RR 4.82, 95% CI 1.09 to 21.32; 4 studies, 757 women, random‐effects; moderate‐quality evidence).

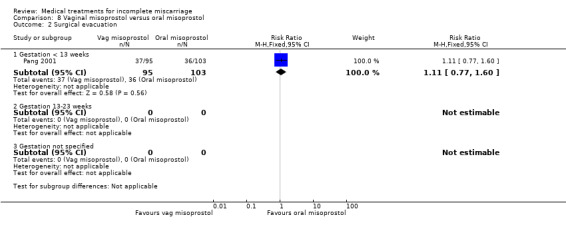

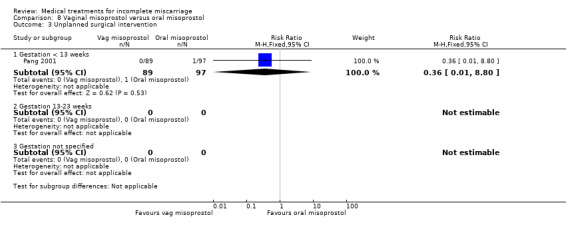

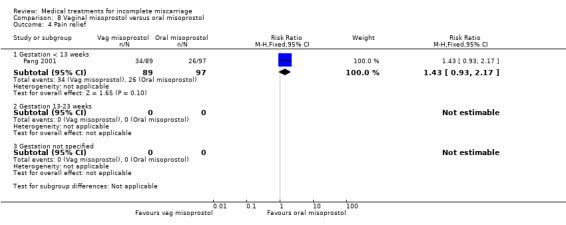

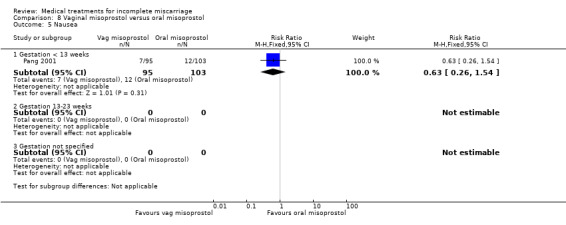

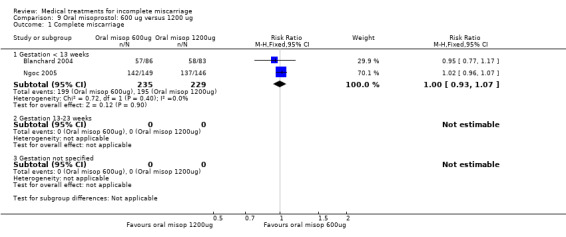

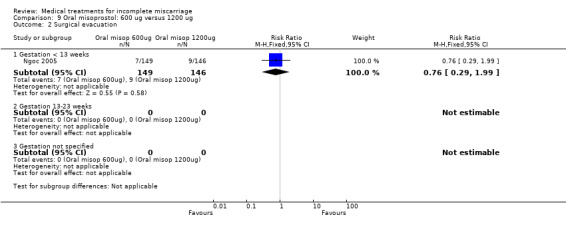

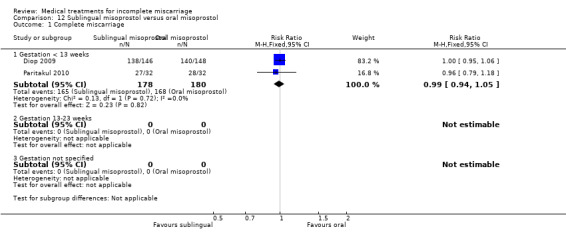

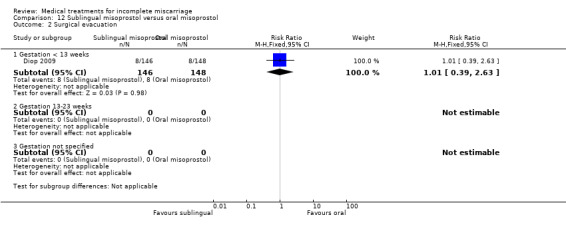

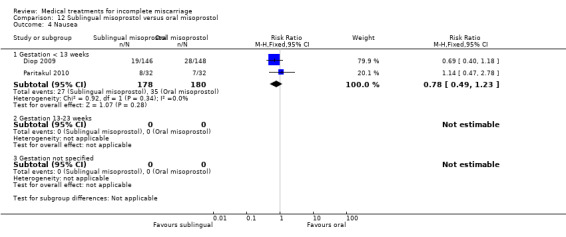

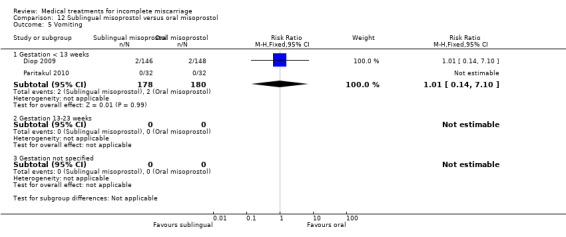

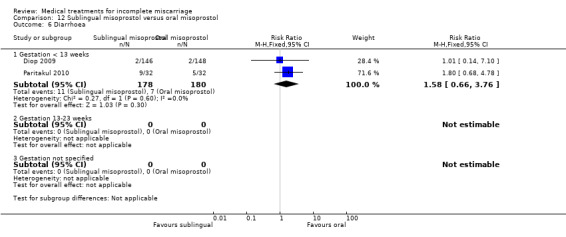

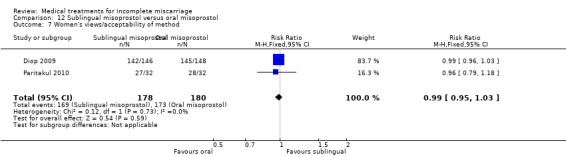

Five trials compared different routes of administration, or doses, or both, of misoprostol. There was no clear evidence of one regimen being superior to another.

Limited evidence suggests that women generally seem satisfied with their care. Long‐term follow‐up from one included study identified no difference in subsequent fertility between the three approaches.

Authors' conclusions

The available evidence suggests that medical treatment, with misoprostol, and expectant care are both acceptable alternatives to routine surgical evacuation given the availability of health service resources to support all three approaches. Further studies, including long‐term follow‐up, are clearly needed to confirm these findings. There is an urgent need for studies on women who miscarry at more than 13 weeks' gestation.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Watchful Waiting; Abortifacient Agents, Nonsteroidal; Abortifacient Agents, Nonsteroidal/administration & dosage; Abortifacient Agents, Nonsteroidal/adverse effects; Abortion, Incomplete; Abortion, Incomplete/therapy; Administration, Intravaginal; Administration, Oral; Diarrhea; Diarrhea/chemically induced; Extraction, Obstetrical; Extraction, Obstetrical/methods; Gestational Age; Misoprostol; Misoprostol/administration & dosage; Misoprostol/adverse effects; Nausea; Nausea/chemically induced; Pregnancy Trimester, First; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Vomiting; Vomiting/chemically induced

Plain language summary

Medical treatments for incomplete miscarriage

What is the issue?

Miscarriage is when a pregnant woman loses her baby before the baby would be considered able to survive outside the womb, i.e. before 24 weeks' gestation. Miscarriage occurs in about 10% to 15% of pregnancies and the signs are bleeding, usually with some abdominal pain and cramping. The traditional management of miscarriage was surgery but this Cochrane Review asks if medical treatments can be another management option for the woman.

Why is this important?

The cause of miscarriage is often unknown, but most are likely to be due to abnormalities in the baby’s chromosomes. Women experiencing miscarriage may be quite distressed, and there can be feelings of emptiness, guilt, and failure. Fathers can also be affected emotionally. Traditionally, surgery (curettage or vacuum aspiration) has been the treatment used to remove any retained tissue and it is quick to perform. It has now been suggested that medical treatments (usually misoprostol) may be as effective and may carry less risk of infection.

What evidence did we find?

We searched for evidence on 13 May 2016 and identified 24 studies involving 5577 women, and all these studies were of women at less than 13 weeks' gestation. There were a number of different ways of giving the drugs and so there are limited data for each comparison.

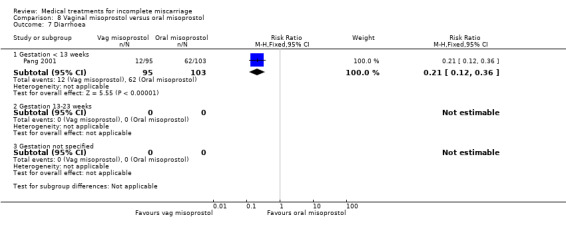

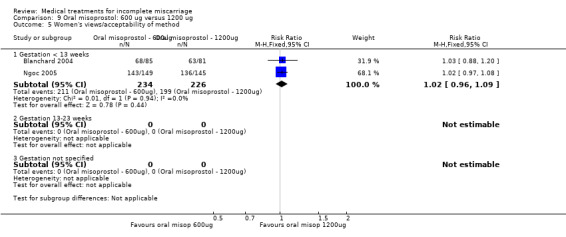

Overall, the review found no real difference in the success between misoprostol and waiting for spontaneous miscarriage (expectant care), nor between misoprostol and surgery. The overall success rate of treatment (misoprostol and surgery) was over 80% and sometimes as high as 99%, and one study identified no difference in subsequent fertility between methods of medication, surgery or expectant management. Vaginal misoprostol was compared with oral misoprostol in one study which found no difference in success, but there was an increase in the incidence of diarrhoea with oral misoprostol. However, women on the whole seemed happy with their care, whichever treatment they were given.

What does this mean?

The review suggests that misoprostol or waiting for spontaneous expulsion of fragments are important alternatives to surgery, but women should be offered an informed choice. Further studies are clearly needed to confirm these findings and should include long‐term follow‐up. There is an urgent need for studies on women who miscarry at more than 13 weeks' gestation.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Misoprostol compared to expectant care for incomplete miscarriage.

| Misoprostol compared to expectant care for incomplete miscarriage | ||||||

| Patient or population: incomplete miscarriage Setting: hospitals in Australia, Sweden, United Kingdom Intervention: misoprostol Comparison: expectant care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with expectant care | Risk with Misoprostol | |||||

| Complete miscarriage | Study population | RR 1.23 (0.72 to 2.10) | 150 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1, 2, 3 | ||

| 579 per 1000 | 712 per 1000 (417 to 1000) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 687 per 1000 | 845 per 1000 (494 to 1000) | |||||

| Surgical evacuation | Study population | RR 0.62 (0.17 to 2.26) | 308 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | ||

| 312 per 1000 | 193 per 1000 (53 to 704) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 327 per 1000 | 202 per 1000 (56 to 738) | |||||

| Unplanned surgical intervention | Study population | RR 0.62 (0.17 to 2.26) | 308 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | ||

| 312 per 1000 | 193 per 1000 (53 to 704) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 327 per 1000 | 202 per 1000 (56 to 738) | |||||

| Women's views/acceptability of method | Study population | ‐ | (0 study) | ‐ | No data | |

| see comment | see comment | |||||

| Nausea | Study population | ‐ | (0 study) | ‐ | No data | |

| see comment | see comment | |||||

| Vomiting | Study population | ‐ | (0 study) | ‐ | No data | |

| see comment | see comment | |||||

| Diarrhoea | Study population | ‐ | (0 study) | ‐ | No data | |

| see comment | see comment | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate‐quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low‐quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low‐quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 One study blinded (placebo‐controlled), but the other unblinded. 2 High levels of heterogeneity. 3 Only two trials, including a total of 150 women.

Summary of findings 2. Misoprostol compared to surgery for incomplete miscarriage.

| Misoprostol compared to surgery for incomplete miscarriage | ||||||

| Patient or population: incomplete miscarriage Setting: clinics and hospitals in Australia, Burkina Faso, Egypt, Ecuador, Ghana, India, Mauritania, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, Turkey, Uganda, USA Intervention: misoprostol Comparison: surgery | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with surgery | Risk with Misoprostol | |||||

| Complete miscarriage | Study population | RR 0.96 (0.94 to 0.98) | 3862 (15 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1, 2, 3 | ||

| 992 per 1000 | 963 per 1000 (943 to 982) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 1000 per 1000 | 970 per 1000 (950 to 990) | |||||

| Surgical evacuation | Study population | RR 0.05 (0.02 to 0.11) | 3070 (13 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1, 2, 4, 5 | ||

| 985 per 1000 | 49 per 1000 (20 to 108) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 1000 per 1000 | 50 per 1000 (20 to 110) | |||||

| Unplanned surgical intervention | Study population | RR 5.03 (2.71 to 9.35) | 2690 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1, 6 | ||

| 8 per 1000 | 38 per 1000 (21 to 71) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 9 per 1000 | 45 per 1000 (24 to 83) | |||||

| Women's views/acceptability of method | Study population | RR 1.00 (0.99 to 1.00) | 3349 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 7 | ||

| 981 per 1000 | 981 per 1000 (971 to 981) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 982 per 1000 | 982 per 1000 (972 to 982) | |||||

| Nausea | Study population | RR 2.50 (1.53 to 4.09) | 3015 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1, 2 | ||

| 84 per 1000 | 210 per 1000 (128 to 343) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 44 per 1000 | 110 per 1000 (67 to 179) | |||||

| Vomiting | Study population | RR 1.97 (1.36 to 2.85) | 2977 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | ||

| 29 per 1000 | 56 per 1000 (39 to 82) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 20 per 1000 | 39 per 1000 (27 to 56) | |||||

| Diarrhoea | Study population | RR 4.82 (1.09 to 21.32) | 757 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | ||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate‐quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low‐quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low‐quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Lack of blinding. 2 High heterogeneity. 3 Lack of smaller studies showing a RR more than 1. 4 Wide confidence interval crossing the line of no effect and small sample size. 5 Asymmetrical funnel plot. 6 Variation of effect size regardless of the study size. 7 Downgraded for overall risk of bias (limitations in design).

Background

Description of the condition

Miscarriage is generally defined as the spontaneous loss of a pregnancy prior to 24 weeks' gestation, that is, before the fetus is usually viable outside the uterus (Shiers 2003). The clinical signs of miscarriage are vaginal bleeding, usually with abdominal pain and cramping. If the pregnancy has been expelled, the miscarriage is termed 'complete' or 'incomplete' depending on whether or not tissues are retained in the uterus. If a woman bleeds but her cervix is closed, this is described as a 'threatened miscarriage' as it is often possible for the pregnancy to continue and not to miscarry (RCOG 2006; Shiers 2003); if the pregnancy is in the uterus but the cervix is open, this is described as an 'inevitable miscarriage', i.e. it will not usually be possible to save the pregnancy and fetus. The now widespread use of ultrasound in early pregnancy, either for specific reasons (e.g. bleeding) or as a routine procedure, reveals pregnancies that are destined to inevitably miscarry, because they are 'non‐viable' (Sawyer 2007; Weeks 2001). Non‐viable pregnancies are either a 'missed miscarriage' if an embryo or fetus is present but is dead, or an 'anembryonic pregnancy' if no embryo has developed within the gestation sac.

Regardless of the type of miscarriage, the overall incidence is considered to be between 10% and 15%, although the real incidence may be greater (Shiers 2003). Most miscarriages occur within the first 12 weeks of pregnancy and are called 'early miscarriage', with those occurring after 13 weeks being known as 'late miscarriage'. The cause of miscarriage is generally unknown, but most are likely to be due to chromosomal abnormalities. The risk of miscarriage has been reported to be higher in older women, and where there are structural abnormalities of the genital tract, infection, and maternal complications such as diabetes, renal disease, and thyroid dysfunction. Also, some environmental factors have been linked with miscarriage, including alcohol and smoking (Shiers 2003). Miscarriage can sometimes lead to haemorrhage and infection, and it can be an important cause of morbidity, and even mortality, particularly in low‐income countries (Lewis 2007).

Women experiencing miscarriage may be overwhelmed by the symptoms and also quite distressed (Shiers 2003). Psychological problems can follow a miscarriage, and these can include loss of self‐esteem resulting from the woman's feeling of inability to rely on her body to give birth (Swanson 1999). Emotional responses described include those of emptiness, guilt, and failure (Swanson 1999). There can also be depression, anxiety, grief, and anger (Klier 2002; Thapar 1992). A number of other consequences, including sleep disturbance, social withdrawal, anger, and marital disturbance, may occur following miscarriage (Lok 2007). Fathers can also be affected emotionally (Klier 2002).

Description of the intervention

Traditionally, all pregnancies that had miscarried were considered by clinicians as potentially incomplete. Therefore, surgical curettage ('evacuation of the uterus') was performed routinely to remove any retained placental tissue. If no tissue was obtained, then a retrospective diagnosis of complete miscarriage was made. Surgical curettage was the 'gold standard management' for miscarriage for many years because it is quickly performed and it is possible to completely remove any retained products of conception (Ankum 2001). Histological examination of the removed tissues also allowed exclusion of trophoblastic disease, e.g. hydatidiform mole ‐ although this is quite rare. New clinical approaches have evolved to try to minimise unnecessary surgical interventions whilst aiming to maintain low rates of morbidity and mortality from miscarriage. These approaches have included ultrasound imaging to diagnose complete miscarriage and thus avoid treatment, or more conservative treatments of incomplete miscarriage, such as drug (medical) treatment or no active treatment (expectant management) (Ankum 2001; Luise 2002). Various types of medical treatment could be suitable as alternatives to routine surgical treatment for miscarriage and these include the use of prostaglandins, or other uterotonic (uterus‐contracting) drugs or anti‐hormone therapy.

How the intervention might work

a) Prostaglandins, e.g. misoprostol, prostaglandin F2alpha

Misoprostol is a synthetic prostaglandin E1 analogue and is marketed for the prevention and treatment of peptic ulcers. Recognised as a potent method for pregnancy termination (Costa 1993; Norman 1991), it is inexpensive, stable at room temperature, and has few systemic effects, although vomiting, diarrhoea, hypertension, and even potential teratogenicity (causing fetal malformation) when misoprostol fails to induce the abortion, have been reported (Fonseca 1991).

Misoprostol has been shown to be an effective myometrial stimulant of the pregnant uterus, selectively binding to EP‐2/EP‐3 prostanoid receptors and stimulating contractions, which push the products or pregnancy out. It is rapidly absorbed orally and vaginally. Vaginally‐absorbed serum levels are more prolonged, and vaginal misoprostol may have locally‐mediated effects (Zieman 1997). Misoprostol could be especially useful in low‐income countries, where transport and storage facilities are inadequate, and the availability of uterotonic agents and blood is limited. Its use in obstetrics and gynaecology has been explored, especially to induce first and second trimester abortion (Costa 1993; Norman 1991), for the induction of labour (Alfirevic 2014; Hofmeyr 2010), and for the prevention of postpartum haemorrhage (Tuncalp 2012). The stimulatory actions of misoprostol on the early pregnancy uterus could, in theory, help to expel retained tissue from the uterus after miscarriage, and provide an attractive medical alternative to surgical treatment of incomplete miscarriage (Chung 1995). It is important to distinguish between the use of misoprostol for incomplete miscarriage and its use for termination of viable pregnancies.

b) Other uterotonics, e.g. ergometrine, oxytocin

Ergometrine (extracted from the rye fungus, ergot) will promote contraction of involuntary muscles throughout the body (Hawk 1985; Kawarabayashi 1990), and oxytocin promotes strong rhythmic contractions of the uterus (Arthur 2007; Mota‐Rojas 2007). Both drugs could potentially have a role in expelling tissue after miscarriage.

c) Progesterone antagonist

A number of progesterone antagonists are now available, and these drugs will interfere with the production, or functioning, or both, of progesterone. The progesterone antagonist, mifepristone, has an established role in the termination of first and second trimester pregnancy (Jain 2002), and may also be effective in promoting expulsion of retained placental tissues following miscarriage (Tang 2006b).

Why it is important to do this review

Bleeding in early pregnancy is the most common reason for women to present to the gynaecology emergency department, and in many of these women, miscarriage will be diagnosed (Ramphal 2006). It is now clear that routine surgical evacuation of the uterus following miscarriage may not be indicated, and the subsequent risk of infection, haemorrhage, cervical damage, uterine perforation, and risks of anaesthesia may not be justified (Harris 2007). In order to optimise clinical management of this common condition, it is important to establish whether the use of medical treatment (drugs), or expectant management (no routine treatment) may offer a safer alternative for women with incomplete miscarriage, and whether there are specific circumstances where one type of treatment plan is superior to others.

We initially aimed to systematically review medical treatments for both non‐viable pregnancies and incomplete miscarriages combined. On further reflection, this seemed illogical. Non‐viable pregnancies contain viable trophoblast (placental) tissue, which produces hormones, which may in theory make these pregnancies more susceptible to anti‐hormone therapy and more resistant to uterotonic (stimulating uterine contractions) therapy than pregnancies in which (incomplete) miscarriage has already taken place. Therefore, this review focuses on the management of incomplete miscarriage. Another Cochrane Review has covered non‐viable pregnancies (Neilson 2006).

Other relevant Cochrane Reviews on the treatment of miscarriage include: 'Expectant care versus surgical treatment for miscarriage' (Nanda 2012), 'Surgical procedures for evacuating incomplete miscarriage' (Tuncalp 2010), 'Anaesthesia for evacuation of incomplete miscarriage' (Calvache 2012), and 'Follow‐up for improving psychological well being for women after a miscarriage' (Murphy 2012). There is also a series of Cochrane Reviews on the possible prevention of miscarriage (Aleman 2005; Bamigboye 2003; Empson 2005; Haas 2013; de Jong PG 2014; Wong 2014; Balogun 2016). In addition, there are Cochrane Reviews on medical and surgical interventions for induced abortions (Dodd 2010; Kulier 2011; Lohr 2008; Wildschut 2011; Say 2010).

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness, safety, and acceptability of any medical treatment for incomplete miscarriage (before 24 weeks).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We only included randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Cluster‐randomised trials were eligible for inclusion, although we did not identify such trials. We excluded quasi‐RCTs and cross‐over trials. We also excluded conference proceedings and abstracts.

Types of participants

Participants were women being treated for spontaneous miscarriage (pregnancy loss at less than 24 weeks), either where there was ultrasound evidence of retained tissue (incomplete miscarriage) or where the diagnosis had been made on clinical grounds alone, and where there would be uncertainty whether the miscarriage was complete or incomplete. In communities in which termination of pregnancy was illegal or unavailable, this could have included women who had undergone unsafe abortion.

We excluded women with non‐viable pregnancies (i.e. where the embryo or fetus had died in utero, but in whom miscarriage had not yet occurred) as they are covered by another Cochrane Review (Neilson 2006).

We also excluded studies on induced abortion of a live fetus and for fetal anomaly as these are covered in other Cochrane Reviews (Dodd 2010; Kulier 2011; Lohr 2008; Wildschut 2011; Say 2010).

Types of interventions

We considered trials if they compared medical treatment of incomplete miscarriage with other methods (e.g. expectant management, placebo, or any other intervention including surgical evacuation, either curettage or vacuum aspiration). We also included comparisons between different routes of administration of drugs (e.g. oral versus vaginal), or between different drugs or doses of drug, or duration or timing of treatment, if data existed.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Complete miscarriage (diagnosis of complete miscarriage based on findings at surgery, or ultrasound examination, or both, after a specific period, or cessation of symptoms and signs, or both).

Surgical evacuation.

Death or serious complications (e.g. uterine rupture, haemorrhage, sepsis, coagulopathy, uterine perforation, hysterectomy, organ failure, intensive care unit admission).

Secondary outcomes

Unplanned surgical intervention (i.e. a second evacuation in the surgical group but a first evacuation in the medical or expectant group).

Blood transfusion.

Haemorrhage (blood loss greater than 500 mL, or as defined by trial authors).

Blood loss.

Anaemia (haemoglobin (Hb) less than 10 g/dL, or as defined by trial authors).

Days of bleeding.

Pain relief.

Pelvic infection.

Cervical damage.

Digestive disorders (nausea or vomiting or diarrhoea).

Hypertensive disorders.

Duration of stay in hospital.

Psychological effects.

Subsequent fertility.

Women's views/acceptability of method.

Pathology of fetal/placental tissue.

Costs.

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth.

Electronic searches

The Information Specialist searched Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth's Trials Register on 13 May 2016.

The Register is a database containing over 22,000 reports of controlled trials in the field of pregnancy and childbirth. For full search methods used to populate Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register, including the detailed search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, and CINAHL, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service, please follow this link to the editorial information about Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth in the Cochrane Library and select the 'Specialized Register' section from the options on the left side of the screen.

Briefly, Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register is maintained by their Information Specialist and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

monthly searches of CINAHL (EBSCO);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Search results are screened by two people and the full‐text of all relevant trial reports identified through the searching activities described above is reviewed. Based on the intervention described, each trial report is assigned a number that corresponds to a specific Pregnancy and Childbirth review topic (or topics), and is then added to the Register. The Information Specialist searches the Register for each review using this topic number rather than keywords. This results in a more specific search set which has been fully accounted for in the relevant review sections (Included studies; Excluded studies; Ongoing studies).

Searching other resources

We searched reference lists at the end of papers for further studies. We did not apply any language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For methods used in the previous version of this review, see Neilson 2013.

For this update, we used the following methods for assessing the 21 reports that we identified as a result of the updated search.

The following Methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth.

Selection of studies

Two review authors (CRK, SB) independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies we identified as a result of the search strategy. We would have resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if had been required, through consultation with a third person.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors (CRK, SB) extracted the data using the agreed form. We would have resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if had been required, through consultation with a third person. We entered data into Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 2014), and checked for accuracy.

Had any information regarding any of the above been unclear, we would have attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (CRK SB) independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in theCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We would have resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if had been required, through consultation with a third person.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We have described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We have assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding was unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high, or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high, or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high, or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature, and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data, including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion, where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; 'as treated' analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s prespecified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s prespecified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we planned to assess the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it is likely to impact on the findings. In future updates, we will explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ see Sensitivity analysis.

Assessment of the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach

For this update, we assessed the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach as outlined in the GRADE Handbook in order to assess the quality of the body of evidence relating to the following outcomes for the two main comparisons: misoprostol versus expectant care and misoprostol versus surgery.

Complete miscarriage

Surgical evacuation

Unplanned surgical intervention

Women's views/acceptability of method (for misoprostol versus surgery only)

Nausea

Vomiting

Diarrhoea

We used GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool to import data from Review Manager 5 in order to create 'Summary of findings' tables (RevMan 2014). We produced a summary of the intervention effect and a measure of quality for each of the above outcomes using the GRADE approach. The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence can be downgraded from 'high‐quality' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates, or potential publication bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference (MD) if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We used the standardised mean difference (SMD) to combine trials that measured the same outcome, but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We planned to include cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials, however, we did not identify any cluster‐randomised trials. If we identify any such trials in future updates, we will adjust their sample sizes using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Section 16.3.4) using an estimate of the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population (Higgins 2011). If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely. We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Cross‐over trials

These are considered inappropriate studies for this review.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. In future updates, if we include more eligible studies, we will explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I², and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if I² was greater than 30% and either Tau² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity. If we identified substantial heterogeneity (above 30%), we planned to explore it by prespecified subgroup analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

With this update, there were several outcomes in the meta‐analysis that included 10 or more studies. Therefore, we investigated reporting biases (such as publication bias). We assessed funnel plot asymmetry visually.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 2014). We used a fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect, i.e. where trials were examining the same intervention, and the trials' populations and methods were judged sufficiently similar.

If there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or if we detected substantial statistical heterogeneity, we used a random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary if we considered an average treatment effect across trials to be clinically meaningful. We treated the random‐effects summary as the average of the range of possible treatment effects and we discuss the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect was not clinically meaningful, we planned not to combine trials. If we used random‐effects analyses, we presented the results as the average treatment effect with 95% CIs, and the estimates of Tau² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

When we identified substantial heterogeneity, we investigated it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We considered whether an overall summary was meaningful, and if it was, used random‐effects analysis to produce it.

For misoprostol versus expectant care, and misoprostol versus surgery, we subgrouped studies by the route of administration of misoprostol (vaginal, oral, sublingual, rectal, combined).

For the remaining comparisons, we carried out the following subgroup analyses on all outcomes.

Women less than 13 weeks’ gestation versus women between 13 and 23 weeks’ gestation versus gestation not specified.

We assessed subgroup differences by interaction tests available within Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014). We reported the results of subgroup analyses quoting the Chi² statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to carry out sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of trial quality assessed by concealment of allocation, high attrition rates, or both, with poor quality studies being excluded from the analyses in order to assess whether this makes any difference to the overall result. We did not carry this out due to lack of data in separate comparisons.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

We identified 164 reports in the original search (September 2009) that covered medical interventions for miscarriage before 24 weeks' gestation, both for women with incomplete miscarriage and women with intrauterine fetal death. We identified 30 reports from an updated search on 23 July 2012. We identified 21 reports from an updated search on 13 May 2016.

We included 24 trials, involving 5577 women in the review (Bique 2007; Blanchard 2004; Blohm 2005; Chigbu 2012; Clevin 2001; Dabash 2010; Dao 2007; Diop 2009; Ganguly 2010; Montesinos 2011; Moodliar 2005; Ngoc 2005; Niinimaki 2006; Pang 2001; Paritakul 2010; Patua 2013; Sahin 2001; Shelley 2005; Shochet 2012; Shwekerela 2007; Taylor 2011; Trinder 2006; Weeks 2005; Zhang 2005); and two trials are ongoing (ISRCTN65305620; NCT01033903). We excluded the remaining trials (reasons listed in table of Characteristics of excluded studies).

Included studies

Twenty of the 24 included studies involved only women with incomplete miscarriage (Bique 2007; Blanchard 2004; Blohm 2005; Chigbu 2012; Clevin 2001; Dabash 2010; Dao 2007; Diop 2009; Montesinos 2011; Moodliar 2005; Ngoc 2005; Pang 2001; Paritakul 2010; Patua 2013; Sahin 2001; Shelley 2005; Shochet 2012; Shwekerela 2007; Taylor 2011; Weeks 2005). Seventeen of the studies took place in low‐income countries, mainly in Africa and Southeast Asia. Three studies included both women with incomplete miscarriage and women with an intrauterine fetal death (Niinimaki 2006; Trinder 2006; Zhang 2005). One of these studies reported the findings for incomplete miscarriage separately from those for intrauterine fetal death (Trinder 2006), and for the other two studies, the authors kindly sent us the separated data (Niinimaki 2006; Zhang 2005). One study included women with early pregnancy failure, which encompassed the anembryonic gestation, embryonic or fetal death, inevitable miscarriage, and incomplete miscarriage (Ganguly 2010). This study reported the findings for incomplete miscarriage separately from the other pregnancy failure types for the primary outcome. There are a further 12 studies that recruited both women with incomplete miscarriage and women with intrauterine fetal death, and we have tried to contact these authors for the separated data, but as yet have been unsuccessful. We have therefore excluded these studies from this review.

All of the 24 included trials addressed medical treatment for incomplete miscarriage before 13 weeks and we found no relevant studies addressing this question for women between 13 and 23 weeks' gestation.

Fourteen of the studies used ultrasound to confirm the diagnosis (Blanchard 2004; Blohm 2005; Clevin 2001; Dao 2007; Ganguly 2010; Montesinos 2011; Moodliar 2005; Ngoc 2005; Niinimaki 2006; Pang 2001; Paritakul 2010; Patua 2013; Zhang 2005). The other studies used clinical assessment for the diagnosis (Bique 2007; Chigbu 2012; Shelley 2005; Shwekerela 2007; Trinder 2006; Weeks 2005), or clinical examination supplemented by ultrasound, when necessary (Dabash 2010; Diop 2009; Shochet 2012; Taylor 2011). The trials assessed completeness of miscarriage at follow‐up, either by ultrasound or clinical assessment, and at times that varied from three days to eight weeks. We have included the specific information in the Characteristics of included studies and also at the beginning of the 'Results' section for each comparison.

Excluded studies

There are 148 excluded studies and these are listed in the reference section under 'Excluded studies'. The table Characteristics of excluded studies states the reasons for exclusion from this review. These reasons mainly include: study not randomised; study including women with non‐viable pregnancies or intrauterine fetal death only; and studies including women having termination of pregnancy. We have also excluded studies where we have been unable to contact the authors for data separated by incomplete miscarriage and intrauterine fetal death (Bagratee 2004; Demetroulis 2001; Hinshaw 1997; Johnson 1997; Louey 2000 [pers comm]; Machtinger 2004; Ngai 2001; Nielsen 1999; Shaikh 2008). Where authors have kindly responded, but have been unable to supply their data separated by incomplete miscarriage and intrauterine fetal death, we have also been compelled to exclude such studies (Chung 1999; Kong 2013; Petersen 2013).

Risk of bias in included studies

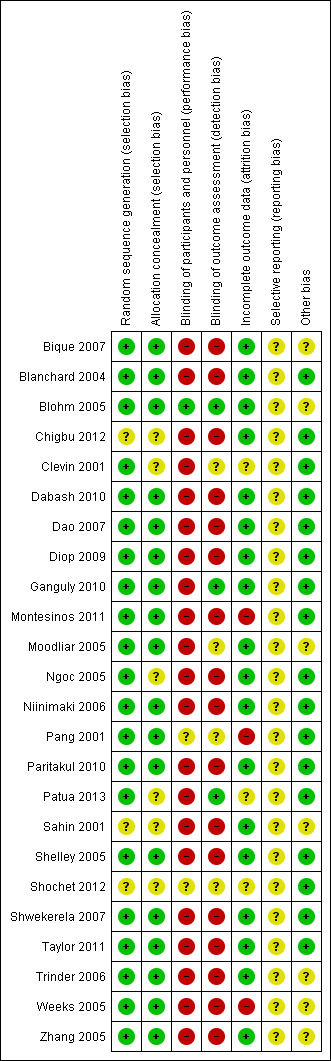

Overall, the risk of bias of studies was generally low, although in most studies it was not possible to blind participants and clinicians. It was unclear whether any of the studies were free of selective reporting bias as we did not assess the trial protocols (Figure 1).

1.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

We excluded studies where group allocation was not random. We considered the random sequence generation to be at low risk of bias in all studies except three (Chigbu 2012; Sahin 2001; Shochet 2012), where it was unclear. We considered allocation concealment to be at low risk of bias in all studies except six (Chigbu 2012; Clevin 2001; Ngoc 2005; Patua 2013; Sahin 2001; Shochet 2012), where it was unclear.

Blinding

We considered blinding to be at low risk of performance bias in only one study (Blohm 2005), and low risk for detection bias in three studies (Blohm 2005; Ganguly 2010; Patua 2013). There was unclear risk of performance bias in two studies (Pang 2001; Shochet 2012), and for detection bias it was unclear in four studies (Clevin 2001; Moodliar 2005; Pang 2001; Shochet 2012). For the remainder of the studies, we considered blinding to be at high risk of bias. However, for many studies we considered it impossible to blind, especially where medical treatment was being compared with surgery.

Incomplete outcome data

Loss to follow‐up and exclusions after randomisation were low in all studies except six; for three, we considered them unclear (Clevin 2001; Patua 2013; Shochet 2012), and another three, we considered to be at high risk of bias (Montesinos 2011; Pang 2001; Weeks 2005). In the Montesinos 2011 study, 16.1% of women did not return for assessment and were not included in analyses. In the Pang 2001 study, it appeared that intention‐to‐treat analysis was not used and the data could not be re‐included. In the Weeks 2005 study, there was complete follow‐up at six days, but by two weeks there was a 33% loss to follow‐up in the misoprostol group and 45% in the group having surgery. This was explained by women not returning from their communities for follow‐up.

Selective reporting

It was unclear to us whether any of the studies were free of selective reporting bias as we were unable to assess the protocols for the studies.

Other potential sources of bias

Seventeen out of the 24 studies appeared to be free of other sources of bias (Blanchard 2004; Chigbu 2012; Clevin 2001; Dabash 2010; Dao 2007; Diop 2009; Ganguly 2010; Montesinos 2011; Ngoc 2005; Niinimaki 2006; Pang 2001; Paritakul 2010; Patua 2013; Shelley 2005; Shochet 2012; Shwekerela 2007; Taylor 2011), and for the remainder, it was unclear.

Effects of interventions

All 24 studies assessed the medical treatment of incomplete miscarriage for women at less than 13 weeks' gestation. There were no studies involving women between 13 and 23 weeks' gestation, and none where gestation was not specified.

For the comparisons of misoprostol (by any route of administration versus expectant care or versus surgery), we used random‐effects meta‐analyses because of the clinical heterogeneity around route of administration. For other meta‐analyses, we used the fixed‐effect model, except where significant heterogeneity was indicated (see Assessment of heterogeneity above). Please note we did not conduct any subgroup analyses on gestation for all comparisons due to lack of data.

1. Misoprostol versus expectant care (3 studies, 335 women, Analyses 1.1 to 1.7)

For women less than 13 weeks' gestation

Three studies involving 335 women addressed this comparison for women with incomplete miscarriage (Blohm 2005; Shelley 2005; Trinder 2006). There were two further studies that involved both women with incomplete miscarriage and women with intrauterine fetal deaths, but to date we have been unable to obtain the data separated by incomplete miscarriage and intrauterine fetal death for these studies (Bagratee 2004; Ngai 2001).

Diagnosis of incomplete miscarriage and assessment of complete miscarriage after treatment were made using clinical judgement in two studies (Shelley 2005; Trinder 2006), and using ultrasound in one study (Blohm 2005). Assessment of the outcome of complete miscarriage was made at differing times in the three studies: Blohm 2005 assessed at one week and Shelley 2005 at 10 to 14 days. As Trinder 2006 assessed at eight weeks, we have not included these data (there was an assessment at two weeks, but the findings were not reported separately for women with incomplete miscarriage and women with intrauterine fetal death). We have written to the authors to seek these data.

All the studies looked at vaginal misoprostol compared with expectant care (Blohm 2005; Shelley 2005; Trinder 2006). There were no studies assessing other routes of administration.

The studies are at low risk of bias overall. However, blinding of participants and clinicians was only used in one (Blohm 2005).

We chose to use random‐effects meta‐analyses for all the outcomes in this comparison as we believe there is clinical heterogeneity as we will be potentially pooling differing routes of administration (vaginal, oral, rectal, and sublingual). We have therefore, reported the average risk ratio (RR) or mean difference (MD). Although there are currently only data from studies using vaginal misoprostol, we believe other studies will be undertaken in the future and will be added at future updates to this review. We have assessed the individual routes of administration of misoprostol for effectiveness (below, in Comparisons 3 to Comparison 8).

Primary outcomes

Complete miscarriage

Only two of the three studies assessed this outcome (Blohm 2005; Shelley 2005), with the primary outcome for the third study being infection at 14 days (Trinder 2006). We rated the quality of the evidence as very low (Table 1), mainly due to high levels of heterogeneity, a small number of women involved (n = 150), and only one of the two studies being blinded.

There was no difference identified in complete miscarriage between misoprostol and expectant care (average risk ratio (RR) 1.23, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.72 to 2.10; 2 studies, 150 women, random‐effects (Tau² = 0.12; Chi² P = 0.02; I² = 81%)) (Analysis 1.1, very low‐quality evidence). In terms of clinical impact, the success rate with misoprostol ranged from 80% to 81% and for expectant care from 52% to 85%. The heterogeneity may result from the different times at which complete miscarriage was assessed with expectant care. One study assessed at one week and found a success rate of 52% (Blohm 2005); the other study assessed at two weeks and found a success rate of 85% (Shelley 2005).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus expectant care, Outcome 1 Complete miscarriage.

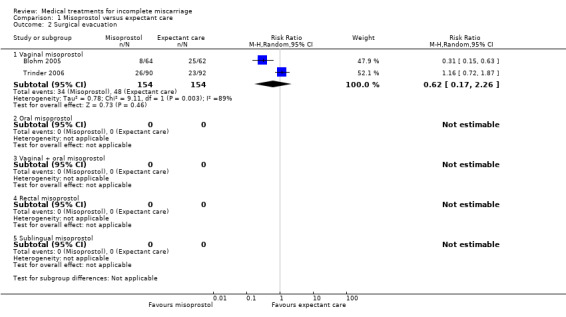

Surgical evacuation

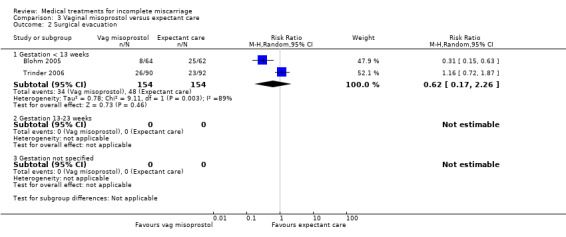

We rated the quality of the evidence as low (Table 1), mainly due to high levels of heterogeneity and only one of the two studies being blinded. We also did not identify a difference in the need for surgical evacuation between misoprostol and expectant care (average RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.17 to 2.26; 2 studies, 308 women, random‐effects (Tau² = 0.78; Chi² P = 0.003; I² = 89%)) (Analysis 1.2, low‐quality evidence).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus expectant care, Outcome 2 Surgical evacuation.

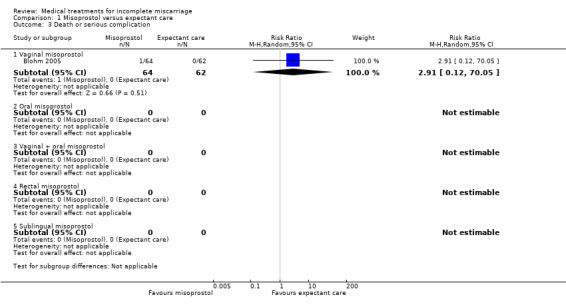

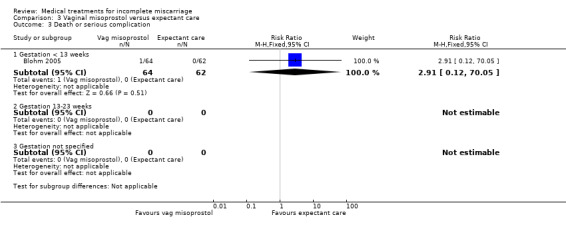

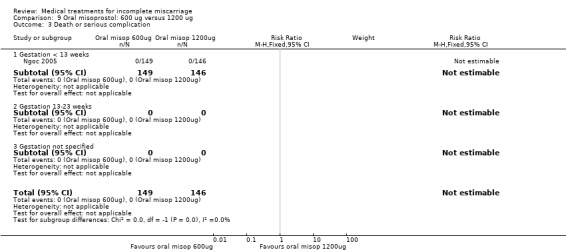

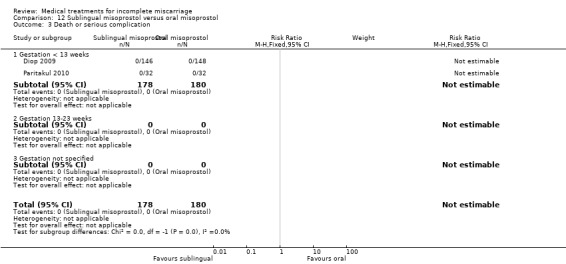

Death or serious complication

The outcome of death or serious complication showed no difference either (RR 2.91, 95% CI 0.12 to 70.05; 1 study, 126 women) (Analysis 1.3), although the review is underpowered to assess this outcome.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus expectant care, Outcome 3 Death or serious complication.

Secondary outcomes

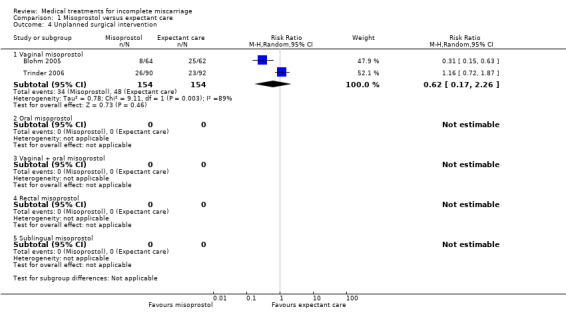

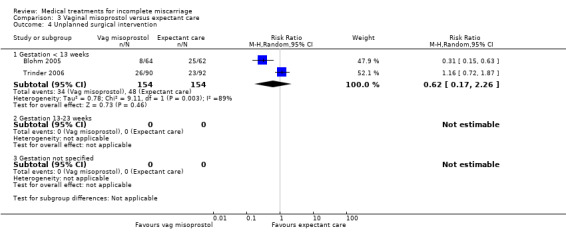

Unplanned surgical intervention

We rated the quality of the evidence as low (Table 1), mainly due to high levels of heterogeneity and only one of the two studies being blinded. We did not identify a difference in unplanned surgical intervention between misoprostol and expectant care (average RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.17 to 2.26; 2 studies, 308 women, random‐effects (Tau² = 0.78; Chi² P = 0.003; I² = 89%)) (Analysis 1.4, low‐quality evidence).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus expectant care, Outcome 4 Unplanned surgical intervention.

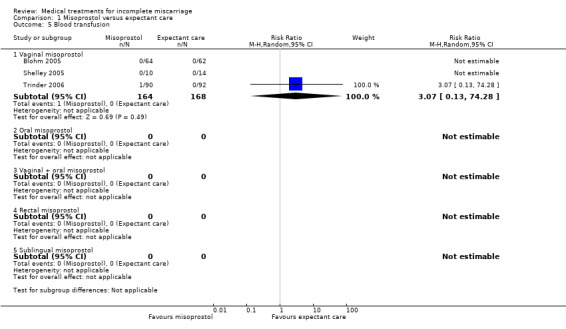

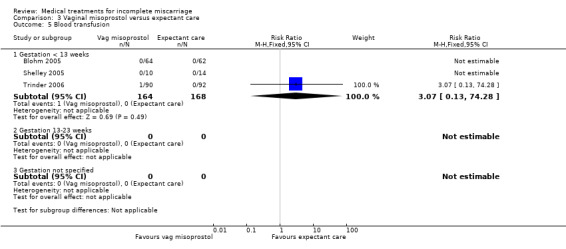

Blood transfusion

We did not identify a difference in the number of blood transfusions undertaken (RR 3.07, 95% CI 0.13 to 74.28; 3 studies, 332 women), although only one study was estimable (Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus expectant care, Outcome 5 Blood transfusion.

Haemorrhage

There was no information reported on haemorrhage.

Blood loss

There was no information reported on blood loss.

Anaemia

There was no information reported on anaemia.

Days of bleeding

There was no information reported on days of bleeding.

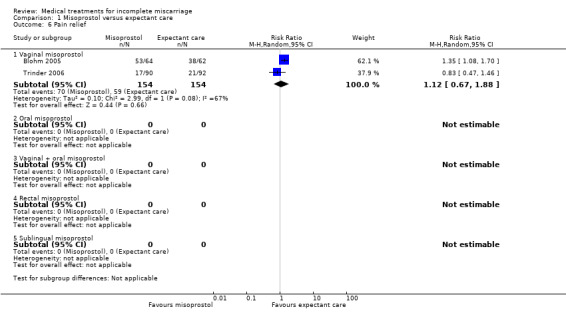

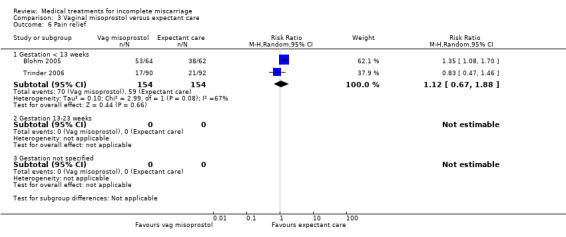

Pain relief

We did not identify a difference in pain relief (average RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.88; 2 studies, 308 women, random‐effects (Tau² = 0.10; Chi² P = 0.08; I² = 67%)) (Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus expectant care, Outcome 6 Pain relief.

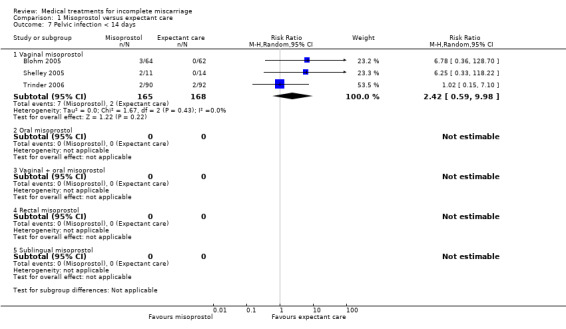

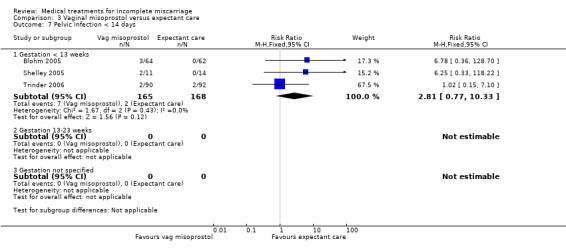

Pelvic infection

We did not identify a difference in pelvic infection (average RR 2.42, 95% CI 0.59 to 9.98; 3 studies, 333 women, random‐effects (Tau² = 0.00; Chi² P = 0.43, I² = 0%)) (Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Misoprostol versus expectant care, Outcome 7 Pelvic infection < 14 days.

Cervical damage

There was no information reported on cervical damage.

Digestive disorders (including nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea)

There was no information reported on digestive disorders.

Hypertensive disorders

There was no information reported on hypertensive disorders.

Duration of stay in hospital

There was no information reported on duration of stay in the hospital.

Psychological effects

There was no information reported on psychological effects.

Subsequent fertility

There was no information reported on subsequent fertility.

Women's views/acceptability of method

There was no information reported on women's views.

Pathology of fetal/placental tissue

There was no information reported on pathology of fetal/placental tissue.

Costs

There was no information reported on costs.

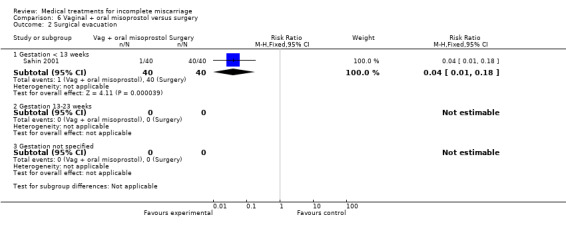

2. Misoprostol versus surgery (16 studies, 4044 women, Analyses 2.1 to 2.17)

For women less than 13 weeks' gestation

Sixteen studies involving 4044 women addressed this comparison for women with incomplete miscarriage at less than 13 weeks' gestation (Bique 2007; Chigbu 2012; Dabash 2010; Dao 2007; Ganguly 2010; Montesinos 2011; Moodliar 2005; Patua 2013; Sahin 2001; Shelley 2005; Shochet 2012; Shwekerela 2007; Taylor 2011; Trinder 2006; Weeks 2005; Zhang 2005). One of these studies was a comparison of misoprostol versus surgery versus expectant management (Trinder 2006), and therefore the comparison is described in the appropriate sections (here and the prior Section 1. Misoprostol versus expectant management).

The included studies were of low risk of bias overall (Figure 1), with most having adequate sequence generation and concealment allocation, although for Sahin 2001 and Shochet 2012, it was unclear. Blinding was not possible in any of the studies when comparing medical treatment with surgery. Only two studies had incomplete data and both related to the study being undertaken in rural settings where women in the community did not return for follow‐up checks (Montesinos 2011; Weeks 2005). We were unclear about the possibility of selective reporting bias as we did not assess any of the study protocols. Six of the 12 studies appeared to be free of other biases (Dabash 2010; Dao 2007; Montesinos 2011; Shelley 2005; Shwekerela 2007; Taylor 2011).

Diagnosis of incomplete miscarriage and assessment of complete miscarriage after treatment was made using clinical judgement in five studies (Bique 2007; Chigbu 2012; Shelley 2005; Shwekerela 2007; Weeks 2005), using ultrasound in eight studies (Dabash 2010; Dao 2007; Ganguly 2010; Montesinos 2011; Moodliar 2005; Patua 2013; Sahin 2001; Zhang 2005), and other studies sometimes used ultrasound. Assessment of the outcome of complete miscarriage was made at differing times in the studies: one study assessed 24 hours after the last dose of misoprostol or the surgical evacuation (Patua 2013), 11 studies assessed at one week (Bique 2007; Chigbu 2012; Dabash 2010; Dao 2007; Ganguly 2010; Montesinos 2011; Shochet 2012; Shwekerela 2007; Taylor 2011; Weeks 2005; Zhang 2005), and three studies assessed around 10 to 14 days (Moodliar 2005; Sahin 2001; Shelley 2005). Trinder 2006 assessed at eight weeks and so we have not included these data (there was an assessment at two weeks in this study, but the findings were not reported separately for women with incomplete miscarriage and women with intrauterine fetal death). We have written to the authors to seek these data.

We have chosen to use random‐effects meta‐analyses for all the outcomes in this comparison as we believe there is clinical heterogeneity as we will be potentially pooling differing routes of administration (vaginal, oral, vaginal + oral, rectal, and sublingual). Although there are currently only data from studies using vaginal misoprostol, we believe other studies will be undertaken in the future and will be added to future updates of this review. We have assessed the individual routes of administration of misoprostol for effectiveness compared with surgery below in Comparisons 7 to 11.

Primary outcomes

Complete miscarriage

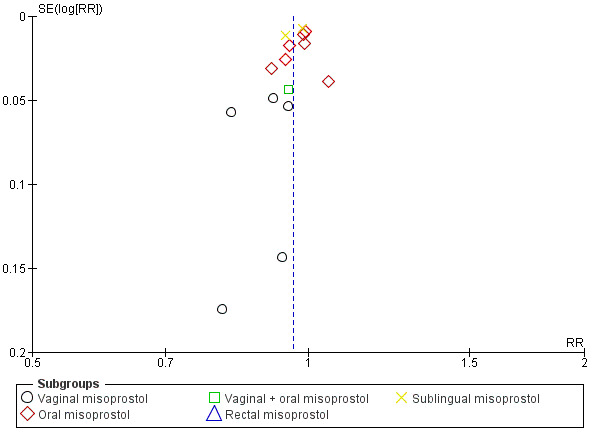

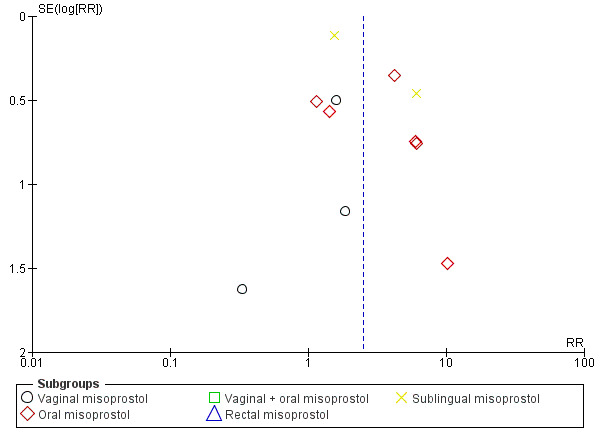

We rated the quality of the evidence as very low (Table 2), mainly due to high heterogeneity, the trials being inevitably unblinded, and suspicion of publication bias. There appeared to be fewer complete miscarriages with misoprostol compared with surgery (average RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.94 to 0.98, 15 studies; 3862 women, random‐effects (Tau² = 0.00; Chi² P < 0.00001, I² = 73%)) (Analysis 2.1), although the upper CI was at 0.98. The funnel plot suggests there could be some missing studies or that there is a lack of smaller studies demonstrating a RR greater than one, so the findings need to be interpreted with caution (Figure 2). However, from the clinical perspective, the success rate was very good for both misoprostol and surgery. Misoprostol achieving between 80% and 99% success across studies, and surgery achieving between 91% and 100% success across studies. The interaction test identified no difference between the subgroups of differing routes of misoprostol administration compared with surgery for this outcome (interaction test (IT) P = 0.08, I² = 56.1%) (Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus surgery, Outcome 1 Complete miscarriage.

2.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 Misoprostol versus surgery, outcome: 2.1 Complete miscarriage.

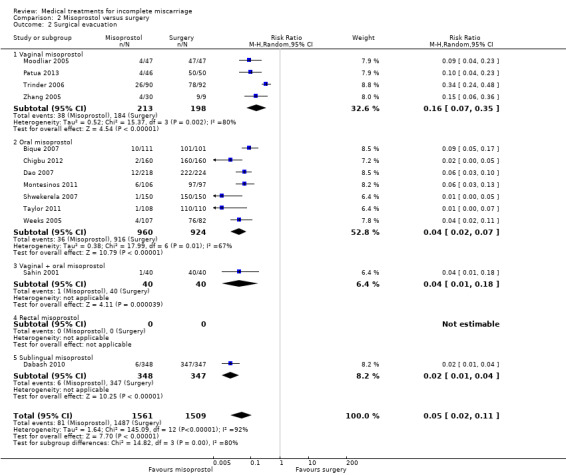

Surgical evacuation

We rated the quality of the evidence as very low (Table 2), due to high heterogeneity, the trials being inevitably unblinded, and the possibility of publication bias. There were fewer surgical evacuations with misoprostol (average RR 0.05, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.11; 13 studies, 3070 women, random‐effects (Tau² = 1.64; Chi² P < 0.00001; I² = 92%)) (Analysis 2.2). The funnel plot is asymmetrical, suggesting that smaller studies of lower methodological quality are showing an exaggerated effect size (Figure 3). The interaction test suggested there may be differences between the subgroups of differing routes of misoprostol administration compared with surgery for this outcome (IT P = 0.002, I² = 79.8%) (Analysis 2.2). However, many of the subgroups have little or no data, and when comparing just the two main subgroups (oral misoprostol and vaginal misoprostol), there is no longer any subgroup difference.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus surgery, Outcome 2 Surgical evacuation.

3.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 Misoprostol versus surgery, outcome: 2.2 Surgical evacuation.

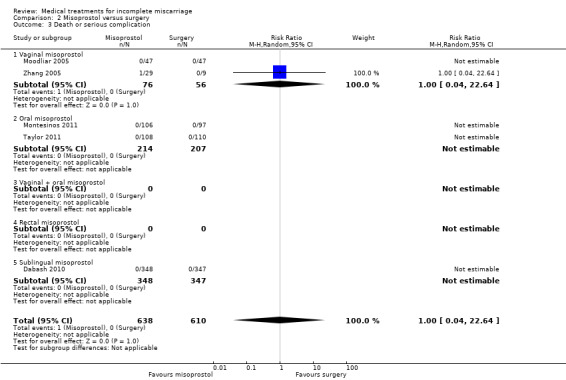

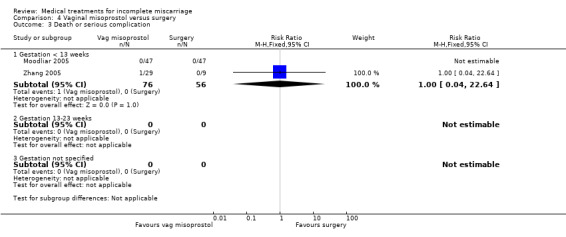

Death or serious complication

We did not identify any difference between misoprostol and surgery (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.04 to 22.64; 5 studies, 1248 women), but only one study was estimable, and the review is underpowered to assess this outcome (Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus surgery, Outcome 3 Death or serious complication.

Secondary outcomes

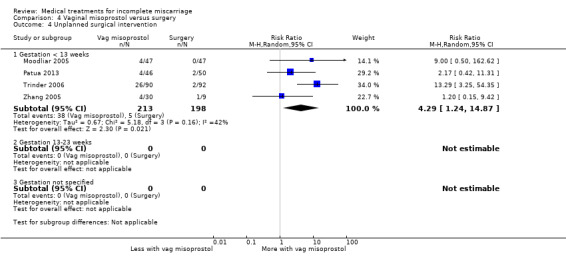

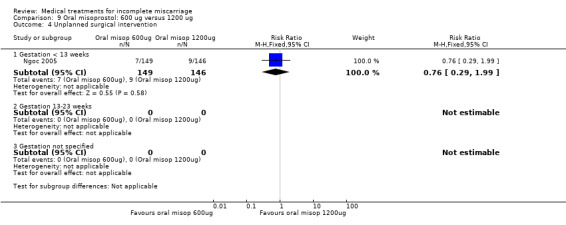

Unplanned surgical intervention

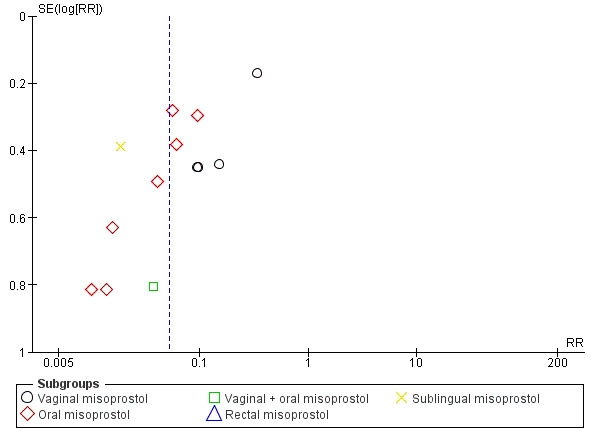

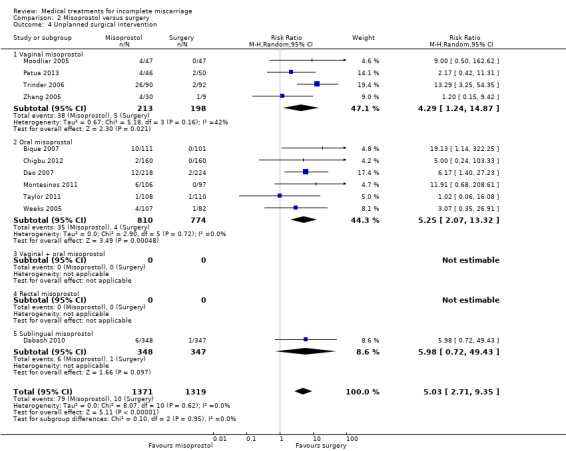

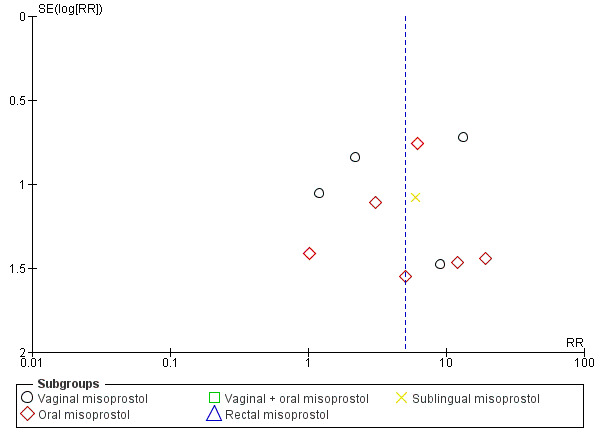

We rated the quality of the evidence as low (Table 2), due to the trials being inevitably unblinded and the potential of publication bias. There was more unplanned surgery with misoprostol (average RR 5.03, 95% CI 2.71 to 9.35; 11 studies, 2690 women, random‐effects (Tau² = 0.00; P = 0.62; Tau², I² = 0%)) (Analysis 2.4). The funnel plot displays a potential bias in that there is variation of effect estimates regardless of the study size. This leads to a consideration that there is something affecting the outcome that is not being measured, which is a form of reporting bias (Figure 4).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus surgery, Outcome 4 Unplanned surgical intervention.

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 Misoprostol versus surgery, outcome: 2.4 Unplanned surgical intervention.

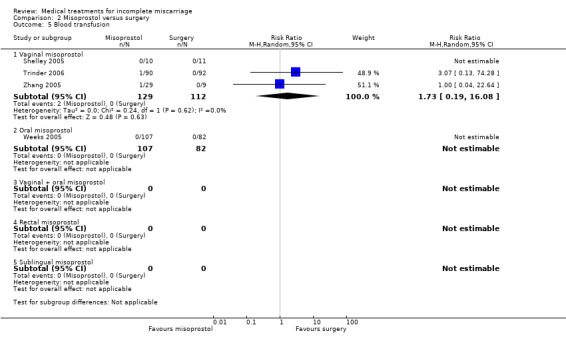

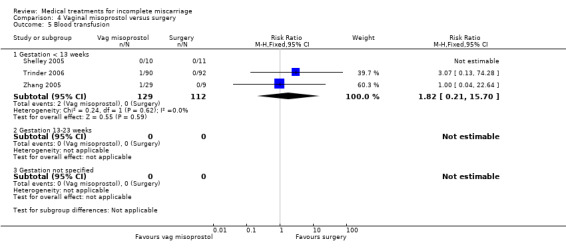

Blood transfusion

We did not identify any difference for the number of blood transfusions undertaken between misoprostol and surgery (average RR 1.73, 95% CI 0.19 to 16.08; 4 studies, 430 women (Tau² = 0.00; Chi² P = 0.62; I² = 0%)) (Analysis 2.5).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus surgery, Outcome 5 Blood transfusion.

Haemorrhage

There was no information reported on haemorrhage.

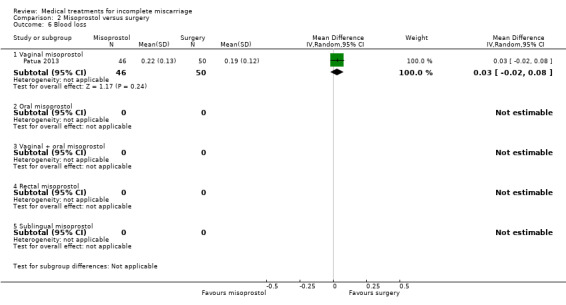

Blood loss

There was no information reported on blood loss.

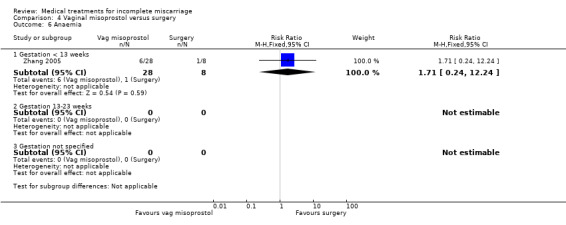

Anaemia

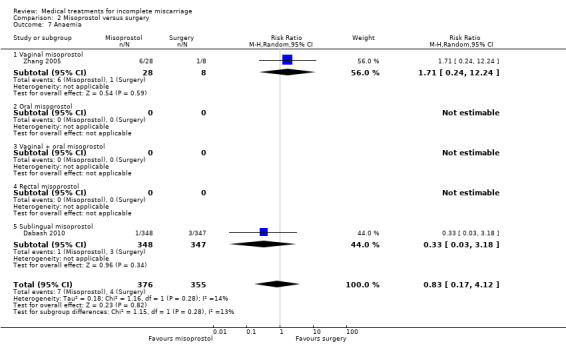

Tau²

We did not identify any difference in anaemia (average RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.17 to 4.12; 2 studies, 731 women, random‐effects (Tau² = 0.18; P = 0.28; I² = 14%)) (Analysis 2.7).

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus surgery, Outcome 7 Anaemia.

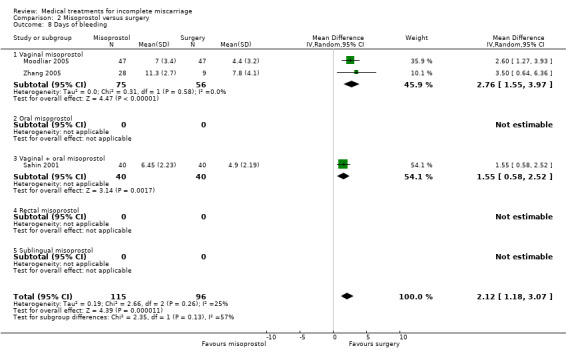

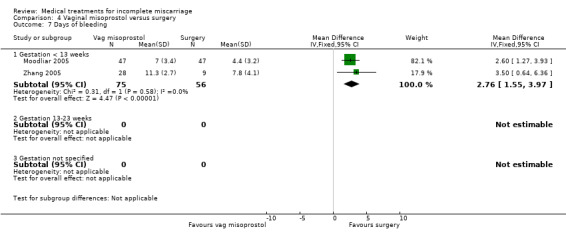

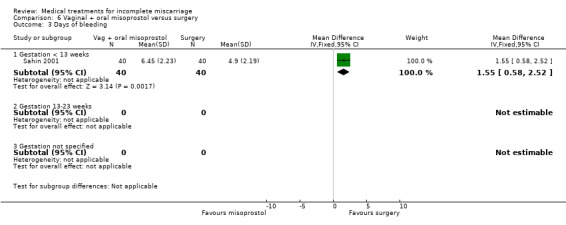

Days of bleeding

There were more days of bleeding with misoprostol than with surgery (average mean difference (MD) 2.12, 95% CI 1.18 to 3.07; 3 studies, 211 women, random‐effects (Tau² = 0.19; Chi² P = 0.26; I² = 25%)) (Analysis 2.8). This difference was also considered clinically significant.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus surgery, Outcome 8 Days of bleeding.

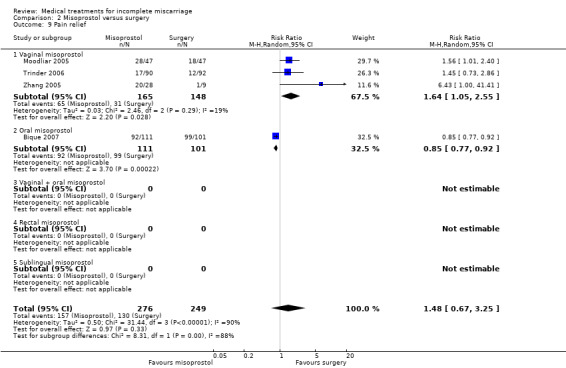

Pain relief

We did not identify a difference with the use of pain relief between women who had misoprostol and women who had surgery (average RR 1.48, 95% CI 0.67 to 3.25; 4 studies, 525 women, random‐effects (Tau² = 0.50; Chi² P < 0.00001; I² = 90%)) (Analysis 2.9).

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus surgery, Outcome 9 Pain relief.

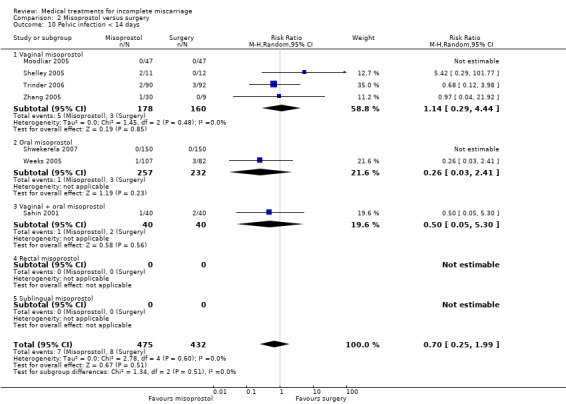

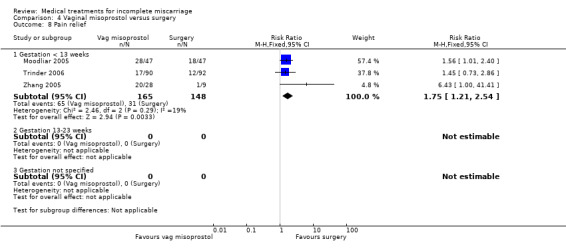

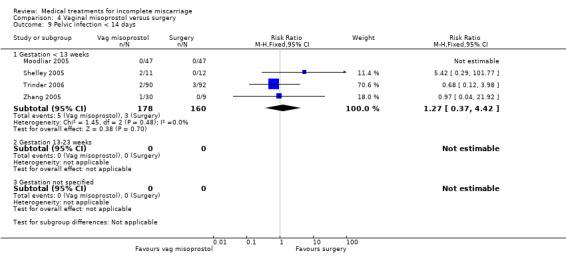

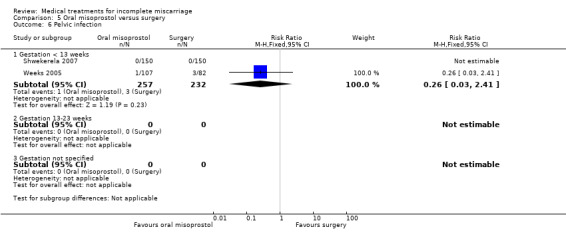

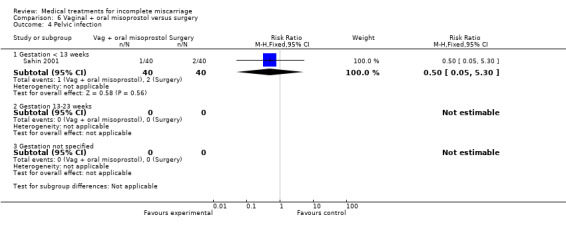

Pelvic infection

We did not identify a difference in the incidence of pelvic infection between women who had misoprostol and those who had surgery (average RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.99; 7 studies, 907 women, random‐effects (Tau² = 0.00; Chi² P = 0.60; I² = 0%)) (Analysis 2.10).

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus surgery, Outcome 10 Pelvic infection < 14 days.

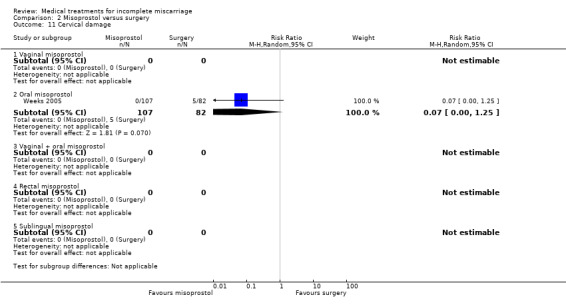

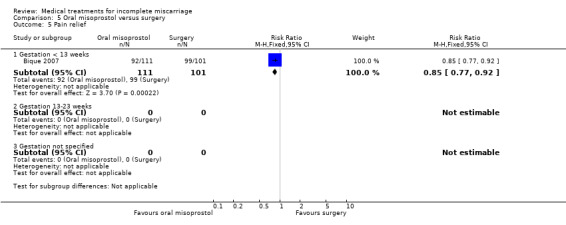

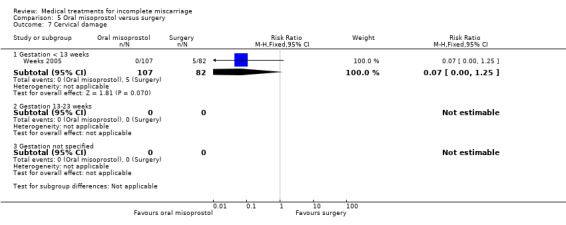

Cervical damage

We did not identify a difference in cervical damage, although only one study assessed this outcome (RR 0.07, 95% CI 0.00 to 1.25; 1 study, 189 women) (Analysis 2.11).

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus surgery, Outcome 11 Cervical damage.

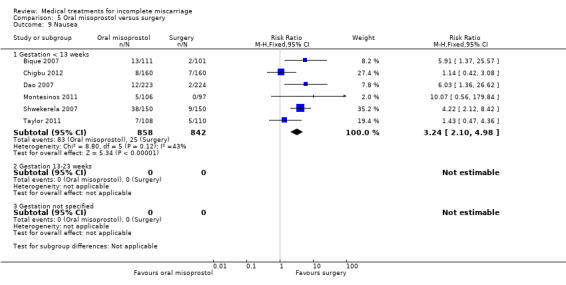

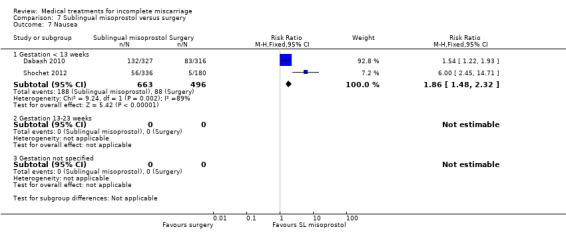

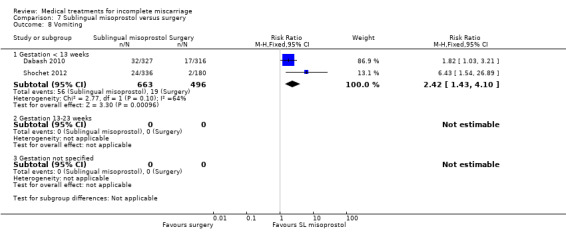

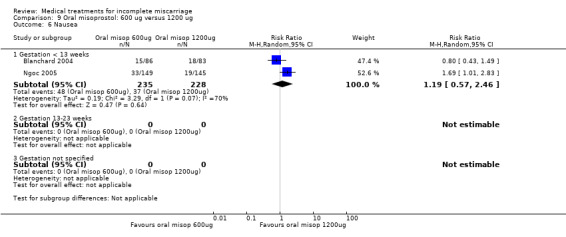

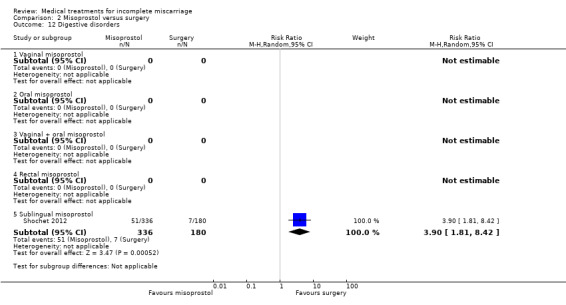

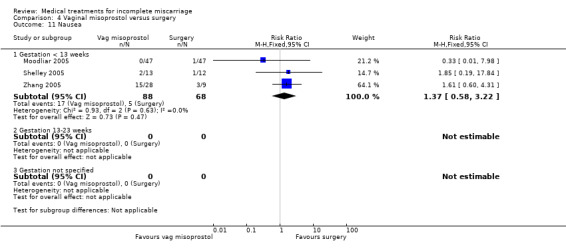

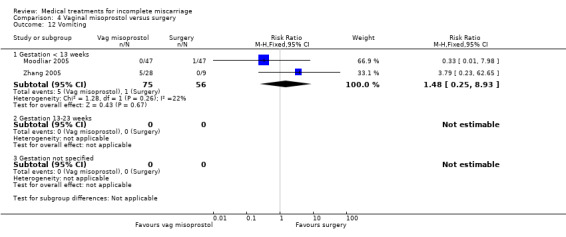

Digestive disorders (including nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea)

We rated the quality of the evidence for vomiting and diarrhoea as moderate (Table 2), due to the trials being inevitably unblinded. We rated the quality of the evidence for nausea specifically, as low due to trials being inevitably unblinded and high heterogeneity.

More women had nausea with misoprostol compared with surgery (average RR 2.50, 95% CI 1.53 to 4.09; 11 studies, 3015 women, random‐effects (Tau² = 0.31 Chi² P = 0.005; I² = 60%)) (Analysis 2.15, low‐quality evidence). This is likely to be clinically significant. The funnel plot does not show existence of a publication bias (Figure 5).

2.15. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus surgery, Outcome 15 Nausea.

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 Misoprostol versus surgery, outcome: 2.15 Nausea.

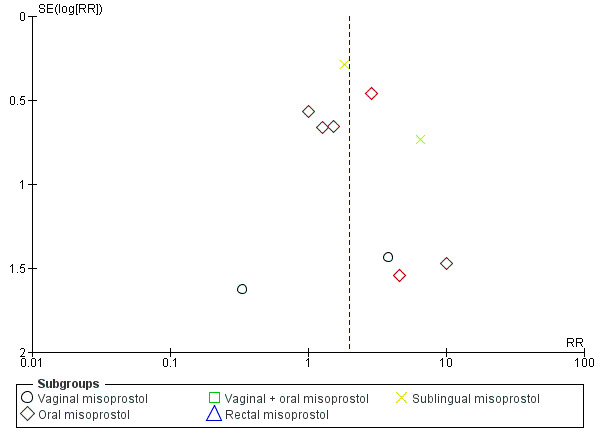

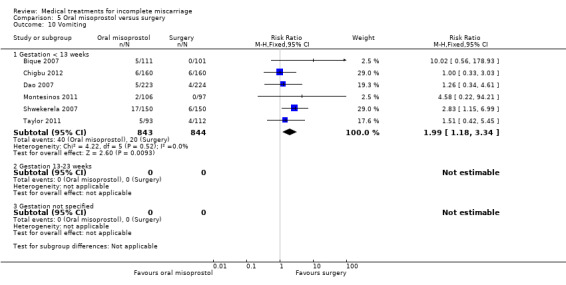

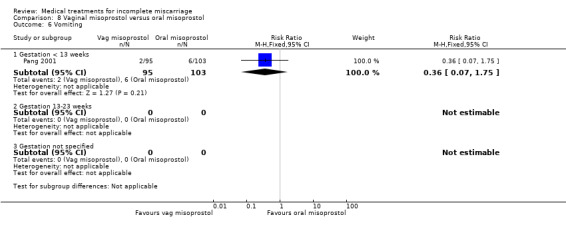

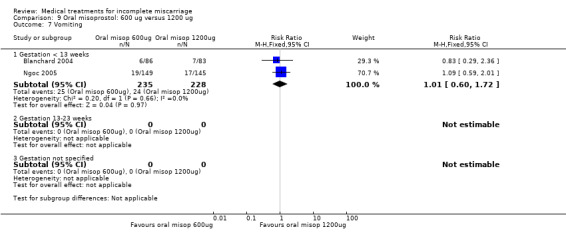

More women had vomiting with misoprostol compared with surgery (average RR 1.97, 95% CI 1.36 to 2.85; 10 studies, 2977 women, random‐effects (Tau² = 0.00; Chi² P = 0.48; I² = 0%)) (Analysis 2.16, moderate‐quality evidence). This may be less clinically significant than the nausea. The funnel plot does not show existence of a publication bias (Figure 6).

2.16. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus surgery, Outcome 16 Vomiting.

6.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 Misoprostol versus surgery, outcome: 2.16 Vomiting.

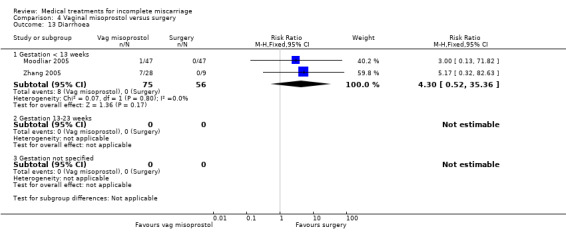

More women had diarrhoea with misoprostol compared with surgery (average RR 4.82, 95% CI 1.09 to 21.32; 4 studies, 757 women, random‐effects (Tau² = 0.00; Chi² P = 0.98; I² = 0%)) (Analysis 2.17, moderate‐quality evidence).

2.17. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus surgery, Outcome 17 Diarrhoea.

Hypertensive disorders

There was no information reported on hypertensive disorders.

Duration of stay in hospital

There was no information reported on duration of stay in the hospital.

Psychological effects

There was no information reported on psychological effects.

Subsequent fertility

There was no information reported on subsequent fertility.

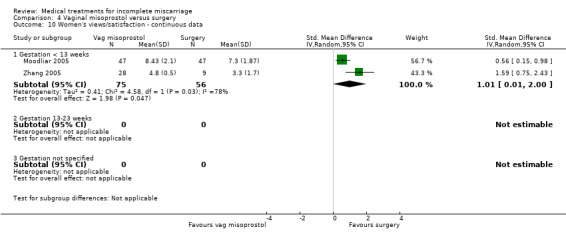

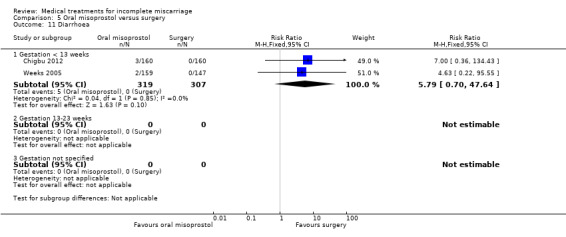

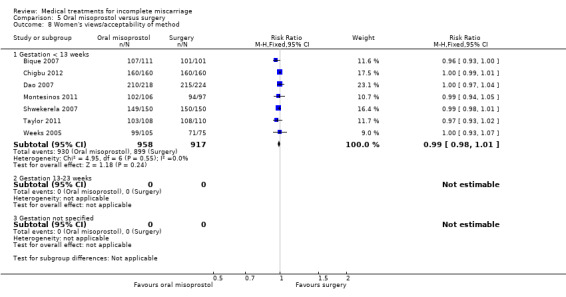

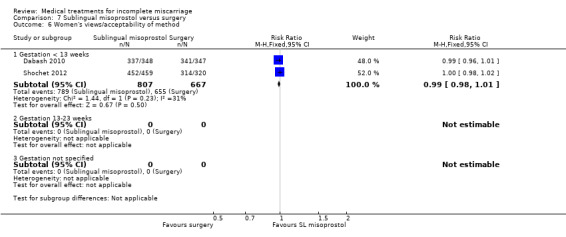

Women's views/acceptability of method

We rated the quality of the evidence as moderate (Table 2), due to the trials being inevitably unblinded.

We did not identify a difference in women's satisfaction between misoprostol and surgery when expressed by whether they were satisfied or not (average RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.00; 9 studies, 3349 women, random‐effects (Tau² = 0.00; Chi² P = 0.64; I² = 0%)) (Analysis 2.13). Women were very satisfied overall, and satisfaction with misoprostol ranged from 91% to 99% across studies, and satisfaction with surgery ranged from 95% to 100%.

2.13. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus surgery, Outcome 13 Women's views/acceptability of method.

When assessed using visual analogue scales, there were more women satisfied with surgery (average standardised mean difference (SMD) 1.01, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.00; 2 studies, 131 women, random‐effects (Tau² = 0.41; Chi² P = 0.03; I² = 78%)), but the difference was small and probably not clinically significant (Analysis 2.14). Taken with the findings above, it appears that overall most women are satisfied with the treatment they received.

2.14. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Misoprostol versus surgery, Outcome 14 Women's views/satisfaction ‐ continuous data.

Pathology of fetal/placental tissue

There was no information reported on pathology of fetal/placental tissue.

Costs

There was no information reported on costs.

3. Vaginal misoprostol versus expectant care (3 studies, 335 women, Analyses 3.1 to 3.7)

For women less than 13 weeks' gestation

Three studies involving 335 women addressed this comparison for women with incomplete miscarriage (Blohm 2005; Shelley 2005; Trinder 2006). There were two further studies that involved both women with incomplete miscarriage and women with intrauterine fetal deaths, but to date we have been unable to obtain the data separated by incomplete miscarriage and intrauterine fetal death for these studies (Bagratee 2004; Ngai 2001).

The studies are of low risk of bias overall. However, blinding of participants and clinicians was only used in one (Blohm 2005), and not the other two studies (Shelley 2005; Trinder 2006).

Diagnosis of incomplete miscarriage and assessment of complete miscarriage after treatment was made using clinical judgement in two studies (Shelley 2005; Trinder 2006), and using ultrasound in the third (Blohm 2005). Assessment of the outcome of complete miscarriage was made at differing times in the three studies: Blohm 2005 assessed at one week, Shelley 2005 at 10 to 14 days, and Trinder 2006 at eight weeks (although there was an assessment at two weeks, findings were not reported separately for women with incomplete miscarriage and women with intrauterine fetal death). We have written to the authors to see if they have earlier data for incomplete miscarriage.

Primary outcomes

Complete miscarriage

Only two of the three studies assessed this outcome (Blohm 2005; Shelley 2005), with the primary outcome for the third study being infection at 14 days (Trinder 2006).

We did not identify a difference in complete miscarriage between vaginal misoprostol and expectant care (average RR 1.23, 95% CI 0.72 to 2.10; 2 studies, 150 women, random‐effects (Tau² = 0.12; Chi² P = 0.02; I² = 81%)) (Analysis 3.1). From the clinical perspective, the success rate with vaginal misoprostol ranged from 80% to 81% and for expectant care from 52% to 85%. The heterogeneity may result from the different times at which complete miscarriage was assessed with expectant care. One study assessed at one week and found a success rate of 52% (Blohm 2005), and the other study assessed at 10 to 14 days and found a success rate of 85% (Shelley 2005).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vaginal misoprostol versus expectant care, Outcome 1 Complete miscarriage.

Surgical evacuation

We also did not identify a difference in the need for surgical evacuation between vaginal misoprostol and expectant care (average RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.17 to 2.26; 2 studies, 308 women, random‐effects (Tau² = 0.78; Chi² P = 0.003; I² = 89%)) (Analysis 3.2).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vaginal misoprostol versus expectant care, Outcome 2 Surgical evacuation.

Death or serious complication

The outcome of death or serious complication showed no difference (RR 2.91, 95% CI 0.12 to 70.05; 1 study, 126 women), although the review is underpowered to assess this outcome (Analysis 3.3).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vaginal misoprostol versus expectant care, Outcome 3 Death or serious complication.

Secondary outcomes

Unplanned surgical intervention

We did not identify a difference in unplanned surgical interventions between vaginal misoprostol and expectant care (average RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.17 to 2.26; 2 studies, 308 women, random‐effects (Tau² = 0.78; Chi² P = 0.003; I² = 89%)) (Analysis 3.4).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vaginal misoprostol versus expectant care, Outcome 4 Unplanned surgical intervention.

Blood transfusion

We did not identify a difference in the number of blood transfusions undertaken (RR 3.07, 95% CI 0.13 to 74.28; 3 studies, 332 women), although only one study was estimable (Analysis 3.5).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vaginal misoprostol versus expectant care, Outcome 5 Blood transfusion.

Haemorrhage

There was no information reported on haemorrhage.

Blood loss

There was no information reported on blood loss.

Anaemia

There was no information reported on anaemia.

Days of bleeding

There was no information reported on days of bleeding.

Pain relief

We did not identify a difference in pain relief (average RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.88; 2 studies, 308 women, random‐effects (Tau² = 0.10; Chi² P = 0.08; I² = 67%)) (Analysis 3.6).

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vaginal misoprostol versus expectant care, Outcome 6 Pain relief.

Pelvic infection

We did not identify a difference in pelvic infection (RR 2.81, 95% CI 0.77 to 10.33; 3 studies, 333 women) (Analysis 3.7).

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vaginal misoprostol versus expectant care, Outcome 7 Pelvic infection < 14 days.

Cervical damage

There was no information reported on cervical damage.

Digestive disorders (including nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea)

There was no information reported on digestive disorders.

Hypertensive disorders

There was no information reported on hypertensive disorders.

Duration of stay in hospital

There was no information reported on duration of stay in the hospital.

Psychological effects

There was no information reported on psychological effects.

Subsequent fertility

There was no information reported on subsequent fertility.

Women's views/acceptability of method

There was no information reported on women's views.

Pathology of fetal/placental tissue

There was no information reported on pathology of fetal/placental tissue.

Costs

There was no information reported on costs.

4. Vaginal misoprostol versus surgery (6 studies, 549 women, Analyses 4.1 to 4.13)

For women less than 13 weeks' gestation

Six studies involving 549 women addressed this comparison for women with incomplete miscarriage (Ganguly 2010; Moodliar 2005; Patua 2013; Shelley 2005; Trinder 2006;.Zhang 2005). Two further studies involved both women with incomplete miscarriage and women with intrauterine fetal deaths, but to date we have been unable to obtain the data separated by incomplete miscarriage and intrauterine fetal death for these studies, and so we have excluded these studies (Demetroulis 2001; Louey 2000 [pers comm]).

The studies were of low risk of bias overall (Figure 1). However, the nature of the intervention and comparison meant it was not possible to blind participants or clinicians, and it was mostly unclear whether the studies had selective reporting bias, or other biases.

Diagnosis of incomplete miscarriage and assessment of complete miscarriage after treatment was made using clinical judgement in two studies (Shelley 2005; Trinder 2006), and using ultrasound in four studies (Ganguly 2010; Moodliar 2005; Patua 2013; Zhang 2005). Assessment of the outcome of complete miscarriage was made at differing times in the studies: Patua 2013 assessed 24 hours after the last dose of misoprostol or surgical evacuation; Ganguly 2010 assessed at day 3 and day 8 for misoprostol, and day 2 and day 8 for surgical evacuation; Zhang 2005 assessed at three days; Shelley 2005 at 10 to 14 days; Moodliar 2005 at two weeks; and Trinder 2006 at eight weeks (although there was an assessment at two weeks, findings were not reported separately for women with incomplete miscarriage and women with intrauterine fetal death). We have written to the authors to seek these data.

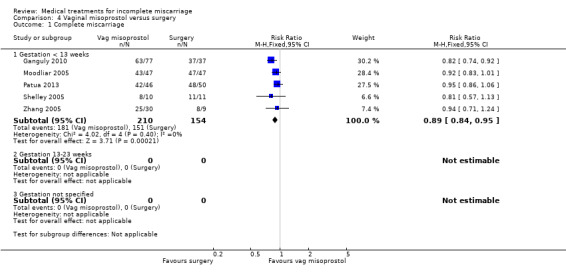

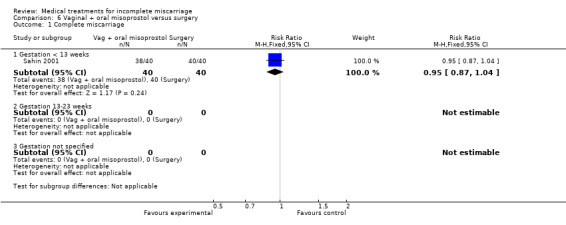

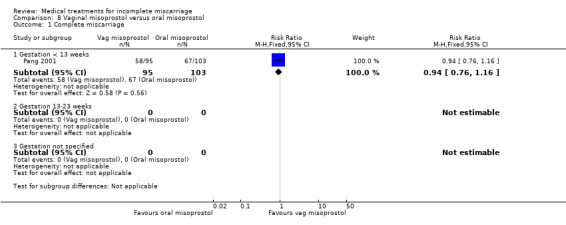

Primary outcomes

Complete miscarriage

Fewer women had complete miscarriage with vaginal misoprostol compared with surgery (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.84 to 0.95; 5 studies, 364 women) (Analysis 4.1). However, from the clinical perspective the success rate was high in both groups, vaginal misoprostol ranged from 80% to 91% and for surgery from 89% to 100%.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Vaginal misoprostol versus surgery, Outcome 1 Complete miscarriage.

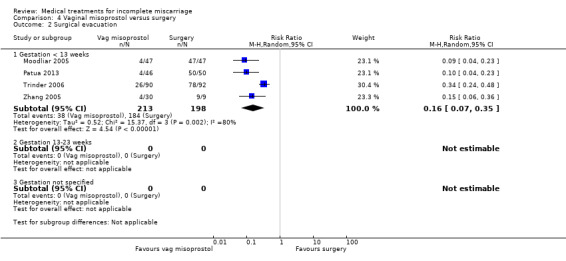

Surgical evacuation

Fewer women had surgical evacuation with vaginal misoprostol compared with women who were given surgery straight away (average RR 0.16, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.35; 4 studies, 411 women, random‐effects (Tau² = 0.52; Chi² P = 0.002; I² = 80%)) (Analysis 4.2). This finding was perhaps not surprising as the comparison group was surgical intervention, but it is an important outcome to assess as clinical management would be to use surgery if misoprostol failed. This reduction in the use of surgery with vaginal misoprostol helps to confirm the success of this intervention. The reasons for the heterogeneity were unclear.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Vaginal misoprostol versus surgery, Outcome 2 Surgical evacuation.

Death or serious complication

We did not identify a difference in the composite outcome of death or serious complications (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.04 to 22.64; 2 studies, 132 women, (although only one was estimable); however, the review is underpowered to assess this outcome (Analysis 4.3).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Vaginal misoprostol versus surgery, Outcome 3 Death or serious complication.

Secondary outcomes

Unplanned surgical intervention

In the vaginal misoprostol group, there was a higher incidence of unplanned surgical intervention (average RR 4.29, 95% CI 1.24 to 14.87; 4 studies, 411 women (Tau² = 0.67; Chi² P = 0.16; I² = 42%)) (Analysis 4.4). Again, this finding is unsurprising, as surgery is the comparative intervention and one would anticipate that few additional operations would be required if surgery was successful.

4.4. Analysis.