Abstract

Background

Any type of seizure can be observed in Alzheimer's disease (AD). Antiepileptic drugs seem to prevent the recurrence of epileptic seizures in most people with AD. There are pharmacological and non‐pharmacological treatments for epilepsy in people with AD. There are no current systematic reviews to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of the treatment. This review aims to review those different modalities.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and tolerability of the treatment of epilepsy for people with Alzheimer's disease (AD) (including sporadic AD and dominantly inherited AD).

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Epilepsy Group Specialized Register (1 February 2016), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (1 February 2016), MEDLINE (Ovid, 1 February 2016) and ClinicalTrials.gov (1 February 2016). In an effort to identify further published, unpublished and ongoing trials, we searched ongoing trials' registers, reference lists and relevant conference proceedings, and contacted authors and pharmaceutical companies.

Selection criteria

We included randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials investigating treatment for epilepsy in people with AD, with the outcomes of proportion of seizure freedom or experiencing adverse events.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened the titles and abstracts of identified records, selected studies for inclusion, extracted data, cross‐checked the data for accuracy and assessed the methodological quality. We performed no meta‐analyses due to the limited available data.

Main results

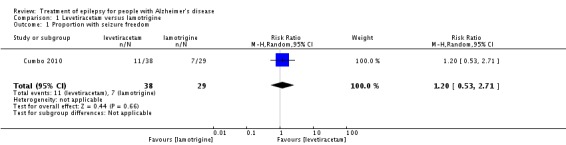

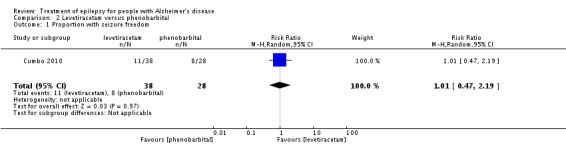

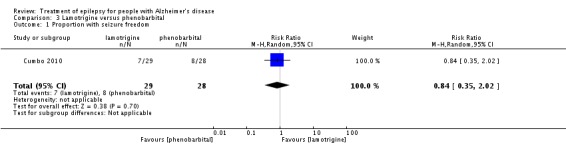

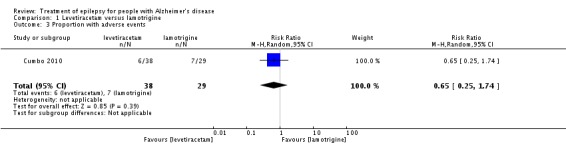

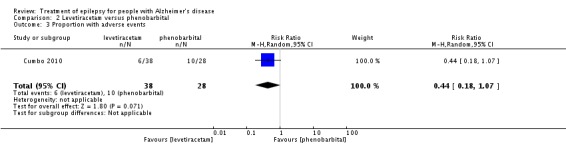

We included one randomised controlled trial with 95 participants. Concerning the proportion of participants with seizure freedom, no significant differences were found in levetiracetam (LEV) versus lamotrigine (LTG) (risk ratio (RR) 1.20, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.53 to 2.71), in levetiracetam versus phenobarbital (PB) (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.47 to 2.19), or in LTG versus PB (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.35 to 2.02). It seemed that LEV could improve cognition and LTG could relieve depression; while PB and LTG could worsen cognition, and LEV and PB could worsen mood. We judged the quality of the evidence to be very low.

Authors' conclusions

This review does not provide sufficient evidence to support LEV, PB and LTG for the treatment of epilepsy in people with AD. Regarding the efficacy and tolerability, no significant differences were found between LEV, PB and LTG. In the future, large randomised, double‐blind, controlled, parallel‐group clinical trials are required to determine the efficacy and tolerability of treatment for epilepsy in people with AD.

Keywords: Aged; Aged, 80 and over; Female; Humans; Male; Alzheimer Disease; Alzheimer Disease/complications; Anticonvulsants; Anticonvulsants/therapeutic use; Cognition; Cognition/drug effects; Depression; Depression/drug therapy; Epilepsy; Phenobarbital; Phenobarbital/therapeutic use; Piracetam; Piracetam/analogs & derivatives; Piracetam/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Triazines; Triazines/therapeutic use

Treatment of epilepsy for people with Alzheimer's disease

Background Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a risk factor for increased seizures in the elderly. Seizures of any type can be observed in AD and are probably underestimated. Study characteristics We searched scientific databases for clinical trials comparing the active comparator with placebo (a 'pretend' treatment) or another active comparator for epilepsy in people with Alzheimer's disease. We wanted to evaluate how well the treatment worked and if it had any side effects. Key results We included and analysed a randomised controlled trial (a clinical study where people are randomly put into one or two or more treatment groups) with 95 participants (identified from a literature search carried out on 1 February 2016). Concerning the proportion of participants with seizure freedom, no significant differences were found for levetiracetam versus lamotrigine (risk ratio (RR) 1.20, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.53 to 2.71), for levetiracetam versus phenobarbital (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.47 to 2.19), or for lamotrigine versus phenobarbital (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.35 to 2.02). It seemed that levetiracetam could improve cognition and lamotrigine could relieve depression; while phenobarbital and lamotrigine could worsen cognition, and levetiracetam and phenobarbital could worsen mood. Quality of the evidence The quality of the evidence from the study was very low and results should be interpreted with caution. Large randomised, double‐blind, controlled, parallel‐group clinical trials are required to determine how effective and well tolerated are treatments for epilepsy in people with AD.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison.

Levetiracetam compared with lamotrigine for the treatment of epilepsy in people with Alzheimer's disease

| Levetiracetam compared with lamotrigine for the treatment of epilepsy in people with Alzheimer's disease | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with AD and epileptic seizures Settings: living in the community of Caltanissetta, Italy Intervention: levetiracetam Comparison: lamotrigine | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| lamotrigine | levetiracetam | |||||

| Proportion with seizure freedom | 241 per 1000 | 289 per 1000 (128 to 653) | RR 1.20 (0.53 to 2.71) | 67 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low¹ | RR > 1 favours levetiracetam |

| Proportion with adverse events | 241 per 1000 | 158 per 1000 (60 to 419) | RR 0.65 (0.25 to 1.74) | 67 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low¹ | RR < 1 favours levetiracetam |

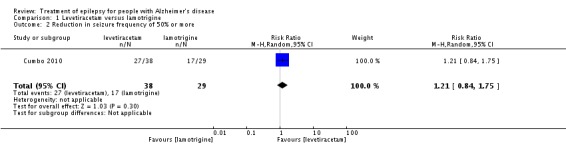

| Reduction in seizure frequency of 50% or more | 586 per 1000 | 711 per 1000 (492 to 1026) | RR 1.21 (0.84 to 1.75) | 67 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low¹ | RR > 1 favours levetiracetam |

| Proportion with seizure freedom in dominantly inherited AD | Not reported | Not reported | ||||

| Change in cognition | See comment | See comment | 67 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low¹ | In lamotrigine group, participants showed slight declines in MMSE and ADAS‐Cog scores. In levetiracetam group, MMSE scores reflected improvement by a mean of 0.23 points as compared with baseline. Similar improvement was observed in ADAS‐Cog scores (−0.23) | |

| Change in neuropsychiatric symptoms | See comment | See comment | 67 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low¹ | In lamotrigine group, score change of −0.72 was recorded on the Cornell scale. In levetiracetam group, mood score worsened with 0.20 points. | |

| Improvement in quality of life | Not reported | Not reported | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes.² The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). AD: Alzheimer's disease; ADAS‐Cog: Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale‐Cognitive; CI: Confidence interval; MMSE: Mini Mental State Examination; RR: Risk Ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

¹Only one trial was included with 67 randomised participants and potential methodological insufficiency. ²Assumed risk is calculated as the event rate in the control group per 1000 people (number of events divided by the number of participants receiving control treatment)

Summary of findings 2.

Levetiracetam compared with phenobarbital for the treatment of epilepsy in people with Alzheimer's disease

| Levetiracetam compared with phenobarbital for the treatment of epilepsy in people with Alzheimer's disease | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients with AD and epileptic seizures Settings: living in the community of Caltanissetta, Italy Intervention: levetiracetam Comparison: phenobarbital | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| phenobarbital | levetiracetam | |||||

| Proportion with seizure freedom | 286 per 1000 | 289 per 1000 (134 to 626) | RR 1.01 (0.47 to 2.19) | 66 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low¹ | RR > 1 favours levetiracetam |

| Proportion with adverse events | 357 per 1000 | 158 per 1000 (64 to 382) | RR 0.44 (0.18 to 1.07) | 66 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low¹ | RR < 1 favours levetiracetam |

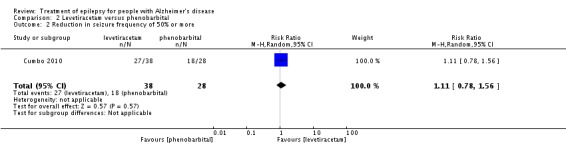

| Reduction in seizure frequency of 50% or more | 643 per 1000 | 711 per 1000 (502 to 1003) | RR 1.11 (0.78 to 1.56) | 66 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low¹ | RR > 1 favours levetiracetam |

| Proportion with seizure freedom in dominantly inherited AD | Not reported | Not reported | ||||

| Change in cognition | See comment | See comment | 66 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low¹ | In phenobarbital group, significant worsening of cognitive performance was found with lower mean scores indicating aggravation of existing cognitive impairment at both 6 and 12 months post randomisation on MMSE and ADAS‐Cog. In levetiracetam group, MMSE scores reflected improvement by a mean of 0.23 points as compared with baseline. Similar improvement was observed in ADAS‐Cog scores (−0.23). | |

| Change in neuropsychiatric symptoms | See comment | See comment | 66 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low¹ | In phenobarbital group, mood score worsened with 1.74 points. In levetiracetam group, mood score worsened with 0.20 points. | |

| Improvement in quality of life | Not reported | Not reported | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes.² The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). AD: Alzheimer's disease; ADAS‐Cog: Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale‐Cognitive; CI: Confidence interval; MMSE: Mini Mental State Examination; RR: Risk Ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

¹Only one trial was included with 66 randomised participants and potential methodological insufficiency. ²Assumed risk is calculated as the event rate in the control group per 1000 people (number of events divided by the number of participants receiving control treatment)

Summary of findings 3.

Lamotrigine compared with phenobarbital for the treatment of epilepsy in people with Alzheimer's disease

| Lamotrigine compared with phenobarbital for the treatment of epilepsy in people with Alzheimer's disease | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients with AD and epileptic seizures Settings: living in the community of Caltanissetta, Italy Intervention: lamotrigine Comparison: phenobarbital | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| phenobarbital | lamotrigine | |||||

| Proportion with seizure freedom | 286 per 1000 | 241 per 1000 (100 to 578) | RR 0.84 (0.35 to 2.02) | 57 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low¹ | RR < 1 favours phenobarbital |

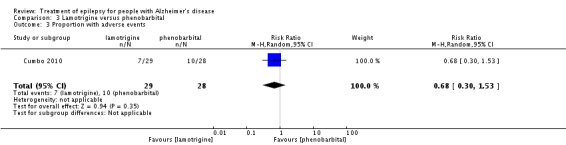

| Proportion with adverse events | 357 per 1000 | 241 per 1000 (107 to 546) | RR 0.68 (0.30 to 1.53) | 57 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low¹ | RR < 1 favours lamotrigine |

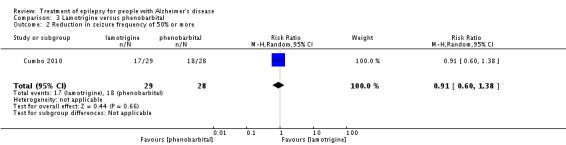

| Reduction in seizure frequency of 50% or more | 643 per 1000 | 586 per 1000 (386 to 887) | RR 0.91 (0.60 to 1.38) | 57 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low¹ | RR < 1 favours phenobarbital |

| Proportion with seizure freedom in dominantly inherited AD | Not reported | Not reported | ||||

| Change in cognition | See comment | See comment | 57 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low¹ | In phenobarbital group, significant worsening of cognitive performance was found with lower mean scores indicating aggravation of existing cognitive impairment at both 6 and 12 months post randomisation on MMSE and ADAS‐Cog. In lamotrigine group, participants showed slight declines in MMSE and ADAS‐Cog scores. | |

| Change in neuropsychiatric symptoms | See comment | See comment | 57 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low¹ | In phenobarbital group, mood score worsened with 1.74 points. In lamotrigine group, score change of −0.72 was recorded on the Cornell scale. | |

| Improvement in quality of life | Not reported | Not reported | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes.² The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). AD: Alzheimer's disease; ADAS‐Cog: Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale‐Cognitive; CI: Confidence interval; MMSE: Mini Mental State Examination; RR: Risk Ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

¹Only one trial was included with 57 randomised participants and potential methodological insufficiency. ²Assumed risk is calculated as the event rate in the control group per 1000 people (number of events divided by the number of participants receiving control treatment)

Background

Description of the condition

Epilepsy is a common neurological disorder and becomes more frequent with age (Brodie 2009). Meanwhile, Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common neurodegenerative disease in the elderly, and is characterised by memory loss, cognitive decline, and behavioural disorders. Although epilepsy is not the predominant symptom in sporadic AD, it is more common in autosomal dominant AD (Wu 2012). It has been estimated that AD is a risk factor for increased seizures in the elderly (Pandis 2012). Approximately 10% to 22% of people with AD have at least one unprovoked seizure (Mendez 2003). Any type of seizure can be observed in AD (Rao 2009). The prevalence of epilepsy is probably underestimated (Tallis 2002), considering the unrecognised non‐convulsive forms. Seizures can be seen even in the early stages of AD (Palop 2007), which suggests seizures may contribute to cognitive impairment.

Description of the intervention

Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) are the current intervention for epilepsy treatment in people with AD. According to a previous study, the efficacy of AEDs in the elderly was proven to be better than that in the younger population (Mattson 1985). The first generation AEDs, such as valproic acid and benzodiazepines, can aggravate cognitive decline in people with AD (Fleisher 2011; Wu 2009). In contrast, the new generation AEDs, e.g. lamotrigine and gabapentin, seem to be well tolerated by the elderly (Rowan 2005; Saetre 2007). Drugs targeting beta amyloid may also be a rational choice for treatment of epilepsy in AD as beta amyloid accumulation can contribute to seizures, as confirmed by Down syndrome and AD mouse models (Puri 2001; Westmark 2008). Non‐pharmacological interventions such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), deep brain stimulation and acupuncture are potentially beneficial for people with AD or people with epilepsy (Hsu 2015; Kimiskidis 2010; Laxpati 2014; McElroy‐Cox 2009).

How the intervention might work

The common mechanisms between AD and epilepsy can probably be attributed to hippocampal sclerosis; that is, neuron loss and astrogliosis in cornu ammonis with sparing of granule cells in the dentate nucleus (Chin 2013). Furthermore, hippocampal sclerosis may be associated with dementia and neuropsychiatric symptoms in people with AD or epilepsy. In AD mouse models, a‐beta amyloid and neurofibrillary tangle‐related tau protein have been suggested to contribute to seizures (Roberson 2011; Westmark 2008). Some studies have demonstrated that seizures occur even earlier than amyloid pathology, which possibly causes the progressive neurodegeneration in AD (Minkeviciene 2009; Palop 2007). Thus, AEDs may reduce the progression of AD by controlling epilepsy, while drugs targeting beta amyloid may reduce seizures by preventing amyloid aggregation. With regard to the mechanisms of TMS, either excitatory or inhibitory responses can be generated in cortical tissues, which improve the symptoms of both AD and epilepsy.

Why it is important to do this review

At present, AED therapy has been tested in clinical trials and seems to prevent the recurrence of epileptic seizures in most people with AD (Rao 2009). Meanwhile, drugs targeting beta amyloid, such as bapineuzumab and solanezumab, have not been widely applied in the treatment of AD. Therefore, their antiepileptic efficacy is still unknown. TMS treatment has been applied in AD and epilepsy, but the efficacy of TMS for epilepsy in people with AD is rarely reported. In this review, we aim to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of the treatment of epilepsy for people with AD. To our knowledge, no systematic review or meta‐analysis on this topic exists.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and tolerability of the treatment of epilepsy for people with Alzheimer's disease (AD) (including sporadic AD and dominantly inherited AD).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials.

Types of participants

We included people diagnosed with AD combined with epilepsy. We used the definitions of AD and epilepsy as provided in the original studies. There were no limitations in gender and age.

Types of interventions

Experimental intervention: any pharmacological or non‐pharmacological intervention for epilepsy, alone or combined with other treatment.

Control intervention: no treatment; placebo alone or combined with other treatment (concomitant interventions had to be the same in each group), as well as the different doses of the experimental intervention.

Types of outcome measures

The outcomes of all the participants initially randomised were collected and subjected to intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis. All the outcomes were measured at the endpoint, in comparison with the data in the baseline. We followed the endpoints as provided in the original publications, and merged the data at the same time point, if possible.

Primary outcomes

Proportion of participants with seizure freedom.

Proportion of participants who experienced any adverse events (AEs).

Secondary outcomes

Proportion of participants with dominantly inherited AD with seizure freedom.

Reduction in seizure frequency of 50% or more.

Change in cognition, measured by Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale‐Cognitive (ADAS‐Cog), etc.

Change in neuropsychiatric symptoms, measured by Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), etc.

Improvement in quality of life, measured by Quality of Life Scale, etc.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases:

Cochrane Epilepsy Group Specialized Register (searched 1 February 2016) using the search strategy set out in Appendix 1;

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL Issue 1, the Cochrane Library, January 2016) using the search strategy set out in Appendix 2;

MEDLINE via Ovid, 1946 to 1 February 2016, using the search strategy set out in Appendix 3;

ClinicalTrials.gov (searched 1 February 2016) using the search strategy set out in Appendix 4;

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (searched 1 February 2016) using the search strategy set out in Appendix 5.

Note: it is no longer necessary to search Embase, because randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials in Embase are now included in CENTRAL.

Searching other resources

We also:

searched reference lists of reviews and retrieved articles for additional studies;

searched conference proceedings from the last three years for relevant studies, in World Congress of Neurology, International Conference of Alzheimer's Disease, Alzheimer's Association International Conference, and International Epilepsy Congress;

contacted researchers, pharmaceutical companies, and relevant trial authors to seek information about unpublished or incomplete trials.

There were no language limitations for the search and we attempted to obtain translations of articles where necessary.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (JL, L‐NW) independently evaluated titles and abstracts of identified trials to determine if they fulfilled inclusion criteria. All potentially relevant studies were obtained in full text for further consideration. We listed the excluded studies and reported the reasons for exclusion. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or by an independent party (L‐YW) if necessary.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (JL, L‐NW) independently extracted eligible data from the published reports onto standardised forms, and cross‐checked them for accuracy. Disagreements regarding data extraction were resolved by consensus between the review authors.

We used checklists to independently record details of the following:

study design;

total study duration;

methods of generating randomisation schedule;

method of concealment of allocation;

blinding;

use of an ITT analysis (all participants initially randomised will be included in the analyses as allocated to groups);

AEs and dropouts for all reasons;

participants (country, number of participants, age, gender, inclusion and exclusion criteria);

comparison (details of the intervention in treatment and control groups, details of co‐intervention(s) in both groups, duration of treatment);

outcomes and time points of measures (number of participants in each group and outcome, regardless of compliance);

factors for heterogeneity (sample size, missing participants, confidence interval (CI) and P value in measurement, subgroup analyses).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (JL, L‐NW) independently assessed the risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreements by discussion or by involving an independent party (L‐YW). We assessed the risk of bias according to the following domains:

Random sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding of participants and personnel.

Blinding of outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective outcome reporting.

Other bias.

We assessed the risk of bias for each domain as high, low or unclear risk and provided information from the study report. We described sources of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We expressed continuous data as mean differences (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Standardised mean difference (SMD) would be used for the outcomes when they were measuring the same thing but in different ways. For all dichotomous outcomes we calculated risk ratios (RR), again with 95% CI. As it was possible that some trials (or groups within a trial) had no adverse events or no dropouts, we would calculate risk differences (RD) instead of RRs in these specific situations, again with 95% CI. ITT was used for all the outcomes. Different control groups were analysed separately.

Unit of analysis issues

We planned to deal with any unit of analysis issues according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

We planned to contact the authors of the studies for further details if any data were missing and to establish the characteristics of unpublished trials through correspondence with the trial co‐ordinator or principal investigator. According to the ITT principle, all randomised participants should be included.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to use the standard Chi² statistic and I² statistic to measure the heterogeneity (Higgins 2011), and make a judgement according to the visual inspection of forest plots. For the Chi² test, we would have rejected the hypothesis of tolerability if the P value was less than 0.10 and an I² greater than 50% would represent significant heterogeneity. In this case, we would have tried to explore factors for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to assess the publication bias by funnel plot if we had found more than 10 studies. However, the review included only one study.

Data synthesis

If we found neither clinical nor statistical heterogeneity, we planned to pool results using a fixed‐effect model. We would have analysed different controls separately. For statistical heterogeneity, we planned to incorporate the results into a random‐effects model. For heterogeneity that could not be readily explained, we would not have pooled the data but only given a description of the results.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to analyse subgroups of studies categorised according to the subtype of AD (sporadic AD and dominantly inherited AD), stage of AD (mild, moderate or severe AD), and the dosage and duration of interventions. As a formal method of comparing subgroups, we planned to use the Chi² test (to test for significant differences between subgroups of participants). For all statistical analyses, we used Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014). However, we did not perform subgroup analyses due to the limited available data.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses for unexplained heterogeneity, such as the exclusion of cross‐over trials from the analysis, the robustness of results to fixed‐effect versus random‐effects assumptions and the inclusion or exclusion of studies at high risk of bias, with inadequate allocation concealment or lack of blinded outcome assessor. We planned to use best‐case and worst‐case scenarios for taking into account missing data. However, we performed no sensitivity analyses due to the limited available data.

Summary of Findings and Quality of the Evidence (GRADE)

In a post hoc change, we have presented three 'Summary of findings' tables, one for each comparison (Table 1; Table 2; Table 3). We reported all outcomes in the tables.

We determined the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach (Schunemann 2011; GRADEPro 2004); and downgraded evidence in the presence of a high risk of bias in at least one study, indirectness of the evidence, unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency, imprecision of results, and high probability of publication bias. We downgraded evidence by one level if we considered the limitation to be serious and by two levels if very serious.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

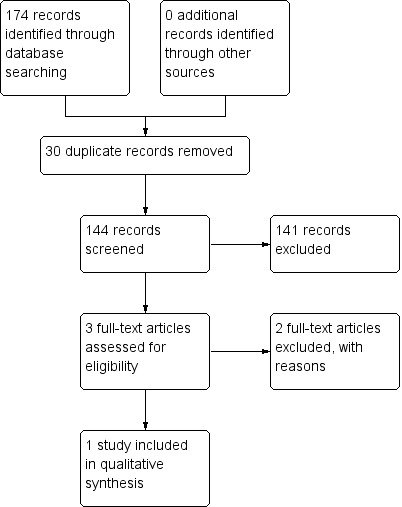

We identified 144 references from the electronic database searches after excluding duplicates (Figure 1). After screening the titles and abstracts, we obtained the full papers of three studies and assessed them for eligibility. We excluded two studies, due to non‐randomised style or ineligible participants (Campion 1995; Lovestone 2015). There was one ongoing RCT (NCT01554683).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

One RCT with 95 participants met the inclusion criteria.

A total of 95 participants with AD and epileptic seizures (41 males, 54 females) with a mean age of 71.75 years (range: 65 to 82 years) and a mean education of 6.3 years (range: 5 to 17 years) living in the community were enrolled. They were randomly assigned with an antiepileptic drug (AED) as monotherapy: 38 were administered levetiracetam (LEV), 28 phenobarbital (PB), and 29 lamotrigine (LTG). This study comprised a 4‐week dose adjustment period followed by a 12‐month dose evaluation period. During the treatment periods, participants received LEV, PB, or LTG and were titrated to an effective dose. No participant was previously exposed to another AED. The initial target dosage of LEV was 500 mg/day increased weekly by 500 mg/day; for PB, it was 50 mg/day increased weekly by 50 mg/day; and for LTG, it was 25 mg/day increased weekly by 25 mg/day. Thereafter, the dosage was individually adjusted. In summary, the mean daily dose of LEV monotherapy was 956 mg (range: 500 to 2000 mg/day); the mean daily dose of PB monotherapy was 90mg/day (range: 50 to 100 mg/day); and the mean daily dose of LTG monotherapy was 57.5 mg/day (range: 25 to 100 mg/day). Further details of the included studies are provided in the Characteristics of included studies.

Excluded studies

We excluded two studies after full‐text evaluation (Campion 1995; Lovestone 2015). The reason for exclusion was due to non‐randomised style or ineligible participants (see Characteristics of excluded studies).

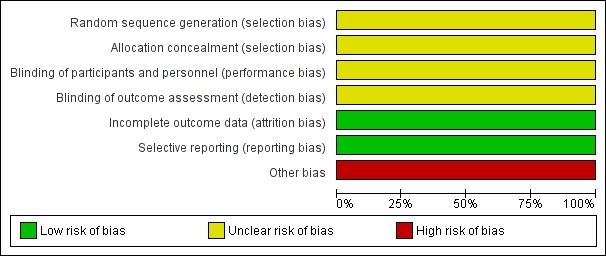

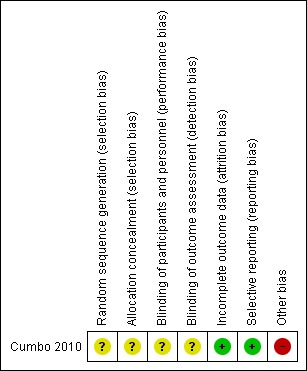

Risk of bias in included studies

The information regarding risk of bias is provided in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Figure 3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Cumbo 2010 did not describe the method used to generate allocation sequence and whether the methods of allocation were concealed or not. Therefore we regarded it as at an unclear risk of bias.

Blinding

The details of blinding were not mentioned in Cumbo 2010. Thus, we evaluated it as at an unclear risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

In Cumbo 2010, 83 (87%) subjects (35 (92%) on LEV, 23 (82%) on PB, 25 (86%) on LTG) completed the study. The reasons for dropouts were given. Therefore, we assessed it as at a low risk of bias.

Selective reporting

We intended to use the table of 'Outcome Reporting Bias In Trials (ORBIT)' to evaluate selective outcome reporting (Kirkham 2010). However, the reporting bias could not be assessed as no pre‐published protocols were available. The outcomes reported in the methods and results were consistent; and all important outcomes expected were reported. Therefore, we evaluated it as at a low risk of bias.

Other potential sources of bias

Minimum necessary sample size was not calculated. We assessed this as at a high risk of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3. An efficacy and tolerability analysis was conducted of all participants who had taken at least one dose (ITT population). People who discontinued the drug for any reason were considered non‐responders with 0% difference from baseline seizure frequency and were included in the efficacy results. There was no difference between groups in demographic or baseline characteristics. All the outcomes were measured at the (12‐month) endpoint.

Primary outcomes

1. Proportion of participants with seizure freedom

At 12 months in the LEV group, 11 of 38 participants (29%) had become seizure free; seven of the 11 were seizure free from the start of therapy, and the other four became seizure free after two months (with a relatively high dosage, 2000 mg/day). In the PB group, eight of 28 participants (29%) were seizure free from the start of therapy at a dosage of 100 mg/day. In the LTG group, elimination of seizures was achieved by seven of 29 (24%) participants (Analysis 1.1; Analysis 2.1; Analysis 3.1).

Analysis 1.1.

Comparison 1 Levetiracetam versus lamotrigine, Outcome 1 Proportion with seizure freedom.

Analysis 2.1.

Comparison 2 Levetiracetam versus phenobarbital, Outcome 1 Proportion with seizure freedom.

Analysis 3.1.

Comparison 3 Lamotrigine versus phenobarbital, Outcome 1 Proportion with seizure freedom.

2. Proportion of participants who experienced any adverse events (AEs)

In the LEV group, AEs were observed in six (16%) participants. These AEs included somnolence, asthenia, headache and dizziness. No participant withdrew due to AEs. In the PB group, 10 (36%) experienced AEs. Somnolence and asthenia were the most frequently reported AEs. PB was discontinued by four participants due to AEs. In the LTG group, seven (24%) participants reported AEs. No participant withdrew because of AEs. There was no statistically significant difference (Analysis 1.3; Analysis 2.3; Analysis 3.3).

Analysis 1.3.

Comparison 1 Levetiracetam versus lamotrigine, Outcome 3 Proportion with adverse events.

Analysis 2.3.

Comparison 2 Levetiracetam versus phenobarbital, Outcome 3 Proportion with adverse events.

Analysis 3.3.

Comparison 3 Lamotrigine versus phenobarbital, Outcome 3 Proportion with adverse events.

Secondary outcomes

1. Proportion of participants with dominantly inherited AD with seizure freedom

None reported.

2. Reduction in seizure frequency of 50% or more

At 12 months in the LEV group, 27 of 38 (71%) had a greater than 50% reduction in seizure frequency. In the PB group, 18 of 28 (64%) had a greater than 50% reduction in seizure frequency. In the LTG group, a greater than 50% reduction in seizure frequency was observed in 17 of 29 (59%) participants. There was no statistically significant difference (Analysis 1.2; Analysis 2.2; Analysis 3.2).

Analysis 1.2.

Comparison 1 Levetiracetam versus lamotrigine, Outcome 2 Reduction in seizure frequency of 50% or more.

Analysis 2.2.

Comparison 2 Levetiracetam versus phenobarbital, Outcome 2 Reduction in seizure frequency of 50% or more.

Analysis 3.2.

Comparison 3 Lamotrigine versus phenobarbital, Outcome 2 Reduction in seizure frequency of 50% or more.

3. Change in cognition

In the LEV group, MMSE scores recorded at the endpoint reflected improvement by a mean of 0.23 points as compared with baseline. Similar improvement was observed in ADAS‐Cog scores (−0.23). LEV was particularly associated with improved attention, short‐term memory, and oral fluency. In the PB group, significant worsening of cognitive performance was found with lower mean scores indicating aggravation of existing cognitive impairment at both 6 and 12 months post randomisation on MMSE and ADAS‐Cog. Participants in the LTG group showed slight declines in MMSE and ADAS‐Cog scores. Due to the lack of mean differences and standard deviations provided, qualitative analyses were unavailable.

4. Change in neuropsychiatric symptoms

Participants in the LTG group scored better on measures of mood. They exhibited progressive improvement on the Cornell scale for depression from six months onward. At the endpoint, a score change of −0.72 was recorded on the Cornell scale. Mood scores for the LEV (0.20) and PB (1.74) groups worsened. Due to the lack of standard deviations provided, qualitative analyses were unavailable.

5. Improvement in quality of life

None reported.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We included one RCT with 95 participants. We found methodological defects and the details are provided in the Characteristics of included studies section. Meta‐analysis was not carried out. There were no significant differences between levetiracetam (LEV), phenobarbital (PB) and lamotrigine (LTG) groups, in the participants with seizure freedom, reduction in seizure frequency of 50% or more, and adverse events. It seemed that LEV could improve cognition and LTG could relieve depression; while PB and LTG could worsen cognition, and LEV and PB could worsen mood.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

One included RCT reported no significant differences between LEV, PB and LTG in the outcomes of efficacy and safety. There were 95 participants randomised with 12 dropouts at the endpoint. Methodological insufficiency was found in the RCT. In the future, large, well‐designed, parallel group RCTs are required.

Quality of the evidence

Only one RCT comprising 95 randomised participants with methodology insufficiency was included. Therefore, we were uncertain about the estimate. The details of allocation sequence generation, allocation concealment and blinding were not provided. Moreover, high risk of attrition bias was found and the minimum necessary sample size was not calculated. All these limitations can affect the quality of the evidence.

Potential biases in the review process

The search for trials was rigorously performed based on the strategies in different electronic databases. One eligible RCT and an ongoing study were found. To identify unpublished or incomplete trials, we also searched for protocols, but found no eligible studies. It is possible that certain unpublished trials were not identified. In addition, due to the inclusion of only one RCT, we could not assess publication bias using funnel plots.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

To our knowledge, this is the first review to systematically evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of treatment for epilepsy in people with AD.

Authors' conclusions

This review does not provide sufficient evidence to support LEV, PB and LTG for the treatment of epilepsy in people with AD. Regarding efficacy and tolerability, no significant differences were found between LEV, PB and LTG.

In the future, large randomised, double‐blind, controlled, parallel‐group clinical trials are required to determine the efficacy and tolerability of treatment for epilepsy in people with AD.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the help provided by the Cochrane Epilepsy Group.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Cochrane Epilepsy Group Specialized Register

#1 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Alzheimer Disease Explode All

#2 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Dementia Explode All

#3 alzheimer* or dement*

#4 (#1 OR #2 OR #3) AND INREGISTER

Appendix 2. Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Alzheimer Disease] explode all trees

#2 MeSH descriptor: [Dementia] explode all trees

#3 (alzheimer* or dement*):ti,ab,kw

#4 #1 or #2 or #3

#5 (epilep* or seizure* or convuls*):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#6 MeSH descriptor: [Epilepsy] explode all trees

#7 MeSH descriptor: [Seizures] explode all trees

#8 (#5 or #6 or #7) in Trials

#9 #4 and #8

Appendix 3. MEDLINE (Ovid)

1. exp Alzheimer Disease/ or exp Dementia/

2. (alzheimer$ or dement$).tw.

3. 1 or 2

4. exp Epilepsy/

5. exp Seizures/

6. (epilep$ or seizure$ or convuls$).tw.

7. 4 or 5 or 6

8. exp *Pre‐Eclampsia/ or exp *Eclampsia/

9. 7 not 8

10. (randomised controlled trial or controlled clinical trial).pt. or (randomi?ed or placebo or randomly).ab.

11. clinical trials as topic.sh.

12. trial.ti.

13. 10 or 11 or 12

14. exp animals/ not humans.sh.

15. 13 not 14

16. 3 and 9 and 15

17. remove duplicates from 16

Appendix 4. ClinicalTrials.gov

Alzheimer AND Epilepsy

Appendix 5. WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform

Alzheimer AND Epilepsy

Data and analyses

Comparison 1.

Levetiracetam versus lamotrigine

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Proportion with seizure freedom | 1 | 67 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.20 [0.53, 2.71] |

| 2 Reduction in seizure frequency of 50% or more | 1 | 67 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.21 [0.84, 1.75] |

| 3 Proportion with adverse events | 1 | 67 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.25, 1.74] |

Comparison 2.

Levetiracetam versus phenobarbital

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Proportion with seizure freedom | 1 | 66 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.47, 2.19] |

| 2 Reduction in seizure frequency of 50% or more | 1 | 66 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.78, 1.56] |

| 3 Proportion with adverse events | 1 | 66 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.44 [0.18, 1.07] |

Comparison 3.

Lamotrigine versus phenobarbital

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Proportion with seizure freedom | 1 | 57 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.35, 2.02] |

| 2 Reduction in seizure frequency of 50% or more | 1 | 57 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.60, 1.38] |

| 3 Proportion with adverse events | 1 | 57 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.30, 1.53] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | A prospective, randomised, three‐arm parallel‐group clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: mild to moderate disease (MMSE score: 10 to 26), age between 60 and 90 years, educational level ≥ 5 years, a diagnosis of partial epilepsy according to the International League Against Epilepsy diagnostic scheme, and a caregiver who could ensure compliance with treatment and provide the information required for psychometric assessments. Exclusion criteria: history of primary neurological or psychiatric disease other than AD, history of seizures experienced prior to the development of AD, drug or alcohol abuse, clinically significant or unstable medical or surgical disorders that could influence the outcome of the study, previous treatment for epilepsy, concomitant treatment with antidepressants or neuroleptics, use of investigational drugs, and refusal to give informed consent in writing. A total of 95 people with AD and epileptic seizures (41 males, 54 females) with a mean age of 71.75 years (range: 65 to 82 years) and a mean education of 6.3 years (range: 5 to 17 years) living in the community were included in the study. They were randomly assigned with an AED as monotherapy: 38 were administered LEV, 28 PB, and 29 LTG. |

|

| Interventions | This study comprised a 4‐week dose adjustment period followed by a 12‐month dose evaluation period. During the treatment periods, participants received LEV, PB, or LTG and were titrated to an effective dose. No participant was previously exposed to another AED. The initial target dosage of LEV was 500 mg/day increased weekly by 500 mg/day; for PB, it was 50 mg/day increased weekly by 50 mg/day; and for LTG, it was 25 mg/day increased weekly by 25 mg/day. Thereafter, the dosage was individually adjusted. The mean daily dose of LEV monotherapy was 956 mg (range: 500 to 2000 mg/day). The mean daily dose of PB monotherapy was 90mg/day (range: 50 to 100mg/day). The mean daily dose of LTG monotherapy was 57.5 mg/day (range: 25 to 100 mg/day). |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: percentage of participants achieving at least 50% and 100% (seizure‐freedom) reduction in seizure frequency; adverse events. Secondary outcomes: changes in MMSE score; changes in ADAS‐Cog score; changes in Cornell scale for depression. | |

| Notes | All participants had concomitant cholinesterase inhibitor therapy for AD. Other concomitant medications, including diuretics, antihypertensives, lipid‐reducing agents, and antidiabetic drugs, started prior to the baseline visit were allowed during the study. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Each subject was randomly assigned to be treated with an AED as monotherapy: 38 were administered LEV, 28 PB, and 29 LTG. The details were not provided. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | The details were not provided. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | The details were not provided. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | The details were not provided. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 83 (87%) subjects (35 on LEV, 23 on PB, 25 on LTG) completed the study. The reasons for dropouts were given. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The outcomes reported in the methods and results were consistent; and all important outcomes expected were reported. |

| Other bias | High risk | Minimum necessary sample size was not calculated. |

AD: Alzheimer's Disease; ADAS‐Cog: Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale‐Cognitive; AED: Antiepileptic Drug; LEV: Levetiracetam; LTG: Lamotrigine; MMSE: Mini Mental State Examination; PB: Phenobarbital

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Campion 1995 | Not a randomised controlled trial. |

| Lovestone 2015 | The participants were not eligible. |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

| Trial name or title | Seizure Activity in Alzheimer's Disease |

| Methods | A Randomised Double‐Blind Placebo‐Controlled Trial with Crossover Assignment |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: probable Alzheimer's disease. Exclusion criteria: a history of seizures prior to the onset of AD |

| Interventions | Levetiracetam (low dose 2.5 mg/kg; high dose 7.5 mg/kg) and placebo |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: Brain Perfusion Blood Flow fMRI; secondary outcomes: Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test, MMSE, Trial Making Test Parts A & B, Phonemic & Category Fluency Test, Boston Naming Test 15‐item version |

| Starting date | February 2012 |

| Contact information | Jocelyn Breton, B.A., jbreton@bidmc.harvard.edu |

| Notes | Estimated Study Completion Date: June 2018 |

AD: Alzheimer's Disease; MMSE: Mini Mental Status Exam

Contributions of authors

JL and L‐NW formulated the idea and developed the basis for the review.

L‐YW served as the independent party in selection of studies and assessment of risk of bias.

The manuscript was completed by JL and L‐NW, and revised by Y‐PW.

JL will be in charge of updating the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

-

National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), UK.

This review was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to the Epilepsy Group. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Declarations of interest

JL: None known.

L‐NW: None known.

Y‐PW: None known.

L‐YW: None known.

New

References

References to studies included in this review

- Cumbo E, Ligori LD. Levetiracetam, lamotrigine, and phenobarbital in patients with epileptic seizures and Alzheimer's disease. Epilepsy & Behavior 2010;17(4):461‐6. [] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 4445567

References to studies excluded from this review

- Campion D, Brice A, Hannequin D, Tardieu S, Dubois B, Calenda A, et al. A large pedigree with early‐onset Alzheimer's disease: clinical, neuropathologic, and genetic characterization. Neurology 1995;45(1):80‐5. [] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 4445569

- Lovestone S, Boada M, Dubois B, Hüll M, Rinne JO, Huppertz HJ, et al. A phase II trial of tideglusib in Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease 2015;45(1):75‐88. [] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 4445571

References to ongoing studies

- Seizure Activity in Alzheimer's Disease. [] ; 4445573

Additional references

- Brodie MJ, Elder AT, Kwan P. Epilepsy in later life. Lancet Neurology 2009;8(11):1019‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin J, Scharfman HE. Shared cognitive and behavioral impairments in epilepsy and Alzheimer's disease and potential underlying mechanisms. Epilepsy & Behavior 2013;26(3):343‐51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleisher AS, Truran D, Mai JT, Langbaum JB, Aisen PS, Cummings JL, et al. Chronic divalproex sodium use and brain atrophy in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2011;77(13):1263‐71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brozek J, Oxman A, Schunemann H. GRADEPro Version 3.6 for Windows. GRADE Working Group, 2004.

- Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [update March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

- Hsu WY, Ku Y, Zanto TP, Gazzaley A. Effects of noninvasive brain stimulation on cognitive function in healthy aging and Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Neurobiology of Aging 2015;36(8):2348‐59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimiskidis VK. Transcranial magnetic stimulation for drug‐resistant epilepsies: rationale and clinical experience. European Neurology 2010;63(4):205‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham JJ, Dwan KM, Altman DG, Gamble C, Dodd S, Smyth R, et al. The impact of outcome reporting bias in randomised controlled trials on a cohort of systematic reviews. BMJ 2010;340:c365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laxpati NG, Kasoff WS, Gross RE. Deep brain stimulation for the treatment of epilepsy: circuits, targets, and trials. Neurotherapeutics 2014;11(3):508‐26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson RH, Cramer JA, Collins JF, Smith DB, Delgado‐Escueta AV, Browne TR, et al. Comparison of carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, and primidone in partial and secondarily generalized tonic‐clonic seizures. The New England Journal of Medicine 1985;313(3):145‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy‐Cox C. Alternative approaches to epilepsy treatment. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports 2009;9(4):313‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez M, Lim G. Seizures in elderly patients with dementia: epidemiology and management. Drugs & Aging 2003;20(11):791‐803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkeviciene R, Rheims S, Dobszay MB, Zilberter M, Hartikainen J, Fülöp L, et al. Amyloid beta‐induced neuronal hyperexcitability triggers progressive epilepsy. The Journal of Neuroscience 2009;29(11):3453‐62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palop JJ, Chin J, Roberson ED, Wang J, Thwin MT, Bien‐Ly N, et al. Aberrant excitatory neuronal activity and compensatory remodeling of inhibitory hippocampal circuits in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. Neuron 2007;55(5):697‐711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandis D, Scarmeas N. Seizures in Alzheimer disease: clinical and epidemiological data. Epilepsy Currents 2012;12(5):184‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri BK, Ho KW, Singh I. Age of seizure onset in adults with Down's syndrome. International Journal of Clinical Practice 2001;55(7):442‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SC, Dove G, Cascino GD, Petersen RC. Recurrent seizures in patients with dementia: frequency, seizure types, and treatment outcome. Epilepsy & Behavior 2009;14(1):118‐20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014.

- Roberson ED, Halabisky B, Yoo JW, Yao J, Chin J, Yan F, et al. Amyloid‐β/Fyn‐induced synaptic, network, and cognitive impairments depend on tau levels in multiple mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. The Journal of Neuroscience 2011;31(2):700‐11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan AJ, Ramsay RE, Collins JF, Pryor F, Boardman KD, Uthman BM, et al. New onset geriatric epilepsy: a randomized study of gabapentin, lamotrigine, and carbamazepine. Neurology 2005;64(11):1868‐73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saetre E, Perucca E, Isojarvi J, Gjerstad L, LAM 40089 Study Group. An international multicenter randomized double‐blind controlled trial of lamotrigine and sustained‐release carbamazepine in the treatment of newly diagnosed epilepsy in the elderly. Epilepsia 2007;48(7):1292‐302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schunemann HJ, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ, Glasziou P, et al. Chapter 12: Interpreting results and drawing conclusions. In: Higgins JPT, Green S editor(s). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tallis R, Boon P, Perucca E, Stephen L. Epilepsy in elderly people: management issues. Epileptic Disorders 2002;4 Suppl 2:S33‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westmark CJ, Westmark PR, Beard AM, Hildebrandt SM, Malter JS. Seizure susceptibility and mortality in mice that over‐express amyloid precursor protein. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology 2008;1(2):157‐68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CS, Wang SC, Chang IS, Lin KM. The association between dementia and long‐term use of benzodiazepine in the elderly: nested case‐control study using claims data. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2009;17(7):614‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Rosa‐Neto P, Hsiung GY, Sadovnick AD, Masellis M, Black SE, et al. Early‐onset familial Alzheimer's disease (EOFAD). Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences 2012;39(4):436‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

- Liu J, Wang LN. Treatment of epilepsy for people with Alzheimer's disease. Treatment of epilepsy for people with Alzheimer's disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 10. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD011922] [DOI] [Google Scholar]