Abstract

Background

Activity limitations of the upper extremity are a common finding for individuals living with stroke. Mental practice (MP) is a training method that uses cognitive rehearsal of activities to improve performance of those activities.

Objectives

To determine if MP improves the outcome of upper extremity rehabilitation for individuals living with the effects of stroke.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register (November 2010), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library, November 2009), PubMed (1965 to November 2009), EMBASE (1980 to November 2009), CINAHL (1982 to November 2009), PsycINFO (1872 to November 2009), Scopus (1996 to November 2009), Web of Science (1955 to November 2009), the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro), CIRRIE, REHABDATA, ongoing trials registers, and also handsearched relevant journals and searched reference lists.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials involving adults with stroke who had deficits in upper extremity function.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected trials for inclusion. We considered the primary outcome to be the ability of the arm to be used for appropriate tasks (i.e. arm function).

Main results

We included six studies involving 119 participants. We combined studies that evaluated MP in addition to another treatment versus the other treatment alone. Mental practice in combination with other treatment appears more effective in improving upper extremity function than the other treatment alone (Z = 3.48, P = 0.0005; standardised mean difference (SMD) 1.37; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.60 to 2.15). We attempted subgroup analyses, based on time since stroke and dosage of MP; however, numbers in each group were small. We evaluated the quality of the evidence with the PEDro scale, ranging from 6 to 9 out of 10; we determined the GRADE score to be moderate.

Authors' conclusions

There is limited evidence to suggest that MP in combination with other rehabilitation treatment appears to be beneficial in improving upper extremity function after stroke, as compared with other rehabilitation treatment without MP. Evidence regarding improvement in motor recovery and quality of movement is less clear. There is no clear pattern regarding the ideal dosage of MP required to improve outcomes. Further studies are required to evaluate the effect of MP on time post stroke, volume of MP that is required to affect the outcomes and whether improvement is maintained long‐term. Numerous large ongoing studies will soon improve the evidence base.

Keywords: Humans, Arm, Practice (Psychology), Stroke Rehabilitation, Imagination, Imagination/physiology, Paresis, Paresis/etiology, Paresis/rehabilitation, Recovery of Function, Stroke, Stroke/complications

Mental practice for treating upper extremity deficits in individuals with hemiparesis after stroke

Mental practice is a process through which an individual repeatedly mentally rehearses an action or task without actually physically performing the action or task. The goal of the mental practice is to improve performance of those actions or tasks. Mental practice has been proposed as a potential adjunct to the physical practice procedures that are commonly performed by survivors of stroke undergoing rehabilitation. Our review of six studies involving 119 participants provided limited evidence that mental practice, when added to traditional physical rehabilitation treatment, produced improved outcomes compared with the use of traditional rehabilitation treatment alone. The evidence to date shows the improvements are limited to measures of performance of real‐life tasks appropriate to the upper limb (e.g. drinking from a cup, manipulating a door knob). It is not clear if mental practice added to physical practice produces improvements in the motor capacity of the upper limb (i.e. the ability to perform selected movements of the upper limb with strength, speed and/or co‐ordination). Finally, there is no evidence available detailing either the components of the mental practice (e.g. How long should the mental practice sessions be? How many mental practice sessions are necessary?, etc) or the qualities of the survivor of a stroke (How long since onset of stroke? How much recovery is required?, etc) that are required to obtain a positive outcome. However, there is reason for optimism that some of the questions will be answered as there are several large trials currently ongoing.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison.

Mental practice in addition to other treatment for treating upper extremity deficits in individuals with hemiparesis after stroke

| Mental practice in addition to other treatment for treating upper extremity deficits in individuals with hemiparesis after stroke | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with treating upper extremity deficits in individuals with hemiparesis after stroke Settings: outpatient clinic / hospital or Intensive Neuro‐Rehabilitation Care Unit Intervention: mental practice in addition to other treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | mental practice in addition to other treatment | |||||

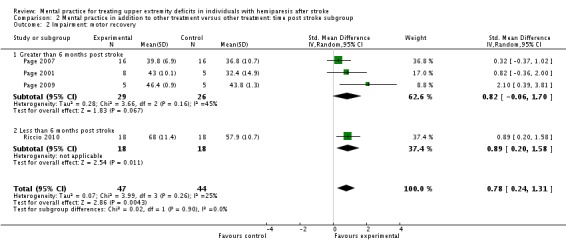

| Impairment ‐ Motor Recovery Fugl‐Meyer or Motricity Index | The mean Impairment ‐ Motor Recovery in the intervention groups was 0.78 standard deviations higher (0.24 to 1.31 higher) | 91 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | SMD 0.74 (0.3 to 1.17) | ||

| Impairment ‐ Motor Recovery ‐ less than 6 months post stroke Motricity Index. Scale from: 0 to 100. | The mean Impairment ‐ Motor Recovery ‐ less than 6 months post stroke in the intervention groups was 0.89 standard deviations higher (0.2 to 1.58 higher) | 36 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | SMD 0.89 (0.2 to 1.58) | ||

| Impairment ‐ Motor Recovery ‐ greater than 6 months post stroke Fugl‐Meyer Assessment of Motor Recovery after Stroke ‐ upper extremity section. Scale from: 0 to 66. | The mean Impairment ‐ Motor Recovery ‐ greater than 6 months post stroke in the intervention groups was 0.82 standard deviations higher (0.06 lower to 1.7 higher) | 55 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | SMD 0.63 (0.07 to 1.2) | ||

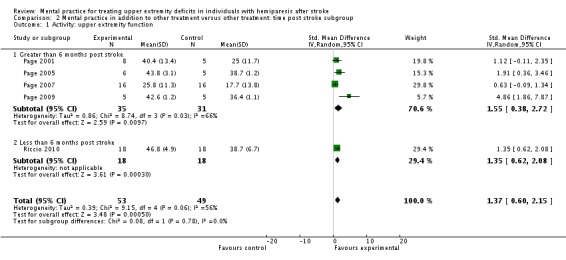

| Activity ‐ Upper Extremity Function Action Research Arm Test or Arm Functional Test | The mean Activity ‐ Upper Extremity Function in the intervention groups was 1.37 standard deviations higher (0.6 to 2.15 higher) | 102 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | SMD 1.16 (0.71 to 1.6) | ||

| Activity ‐ Upper Extremity Function ‐ greater than 6 months post stroke Action Research Arm Test. Scale from: 0 to 57. | The mean Activity ‐ Upper Extremity Function ‐ greater than 6 months post stroke in the intervention groups was 1.55 standard deviations higher (0.38 to 2.72 higher) | 66 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate5 | SMD 1.05 (0.48 to 1.61) | ||

| Activity ‐ Upper Extremity Function ‐ less than 6 months post stroke Arm Functional Test ‐ Functional Ability Scale | The mean Activity ‐ Upper Extremity Function ‐ less than 6 months post stroke in the intervention groups was 1.35 standard deviations higher (0.62 to 2.08 higher) | 36 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate6 | SMD 1.35 (0.62 to 2.08) | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 inconsistencies across studies re: allocation concealment and blinding 2 inconsistencies in study re: allocation concealment and blinding 3 inconsistencies across studies re: allocation concealment and blinding 4 inconsistencies across studies re: allocation concealment and blinding 5 inconsistencies across studies re: allocation concealment and blinding 6 inconsistencies in study re: allocation concealment and blinding. Information about validity and details of Arm Functional Test not clear.

Background

Stroke is defined as a sudden loss of brain function. It is caused by the interruption of flow of blood to the brain (ischaemic stroke) or the rupture of blood vessels in the brain (haemorrhagic stroke) (Heart and Stroke 2009a). People who experience a stroke may undergo sudden and intense changes in perception, cognition, mood, speech, health‐related quality of life, and function (e.g. difficulty walking or using the arm) (Mayo 1999). A review of population‐based epidemiological studies of stroke in 13 countries, published between 1992 and 2001, showed that the incidence of new stroke ranged from 1.3 to 4.1 per 1000 person‐years (e.g. 1000 people followed for one year) and the prevalence of people living with stroke ranged from 46.1 to 73.3 per 1000 population (Feigin 2003). It is estimated that in the United Kingdom, 150,000 individuals have a stroke each year (The Stroke Association 2009). In Canada, there are approximately 300,000 individuals living with the effects of stroke, with more than 50,000 individuals sustaining a new stroke each year (Heart and Stroke 2009b). It is estimated, by self report, that 3.7% of Canadians between the ages of 65 and 79 years are survivors of stroke and that 7.4% of those aged 80 years and over are living with the effects of stroke (Heart and Stroke 2009b). Stroke was estimated to cost the Canadian Health Care system CAD 2.7 billion in 1993 (Heart and Stroke 2009b).The cost of stroke has been described as vast, with the lifetime costs per patient ranging from USD 11,787 to USD 3,035,671 (Palmer 2005).

This review uses terminology from the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). The ICF defines activity as "the execution of a task or action by an individual", while activity limitations are defined as "difficulties an individual may have in executing activities" (World Health Organization 2001). In the ICF, body functions are "the physiological functions of body systems (including psychological function)" and body structures are "anatomical parts of the body such as organs, limbs and their components" (World Health Organization 2001). Impairments are "problems in body function or structure such as significant deviation or loss" (World Health Organization 2001).

Activity limitations of the upper extremity (arm and hand) are a common finding for individuals living with the effects of stroke, with its prevalence reported as between 33% and 95% of this population (Heller 1987; Nakayama 1994; Parker 1986; Sunderland 1989). These activity limitations may occur because of deficits in body structures and functions caused by the stroke, such as in motor ability (Andrews 2003; Canning 2004; Chae 2002; Mercier 2004), somatosensation (Carey 1995) and perceptual ability (Chen Sea 1993; Kalra 1997; Katz 1999). This has led to a variety of interventions that rehabilitation professionals may use to maximise the upper extremity function of the individuals they treat (Cauraugh 2002; French 2007; Mehrholz 2008; Moreland 1994; Richards 1999; Rose 2004; Wolf 2006). A feature of these interventions that is thought to be critical to their success is the number of repetitions the individuals perform. Conventional rehabilitation programmes have been criticised for failing to provide the opportunity to perform a sufficient volume of practice. Moreover, several authors have suggested that increasing the amount of time spent in therapeutic activity in rehabilitation units would improve the units' effectiveness as learning environments, improving a patient's recovery (Bernhardt 2004; Bernhardt 2008; Lincoln 1996; Mackey 1996).

Mental practice (MP) is a training method that calls for cognitive rehearsal of activities for the explicit purpose of improving performance of those activities. The movement is not actually produced but is, instead, produced in the individual's imagination (Jackson 2001; Page 2001). As such, MP has been called 'covert rehearsal' (Schmidt 1999). The use of MP to augment performance in athletics has been advocated for many decades (Andrisani 2003; Gallwey 1977; Joy 2005). There is consensus that in neurologically intact individuals MP is more effective than no practice in producing skilled movement; however, physical practice where the goal movements are produced seems to be superior to MP alone (Driskell 1994; Felz 1983). It has been suggested that tasks requiring problem solving are more suited to and would benefit more from MP (Batson 2004).

Hypotheses have been proposed to explain how MP works (Schmidt 1999). The 'neuromuscular theory' hypothesizes that an individual engaged in MP makes repeated activations of the desired motor program but with the 'gain' of the program dampened, thereby rendering the muscle contractions so weak that no movement is observed. However, the individual's learning improves from these subthreshold activations of the motor programs. Another hypothesis proposes that the individuals engaged in MP rehearse elements of the task thereby giving the opportunity to predict outcomes of actions based on their previous experience, and so they develop ways to address the outcomes. In this way, the individual explores possible anticipated courses of actions that they are more likely to employ in real performance of the movement. Neuroimaging has shown that similar areas of the brain are activated with both imagining a movement and physically completing a movement in individuals with and without stroke (Batson 2004).

Examination of the factors that maximise the effects of MP appears to be limited. A study of 12 individuals living with effects of stroke showed that ability to use working memory to maintain and manipulate information was related to the magnitude of improvement found after an intervention of physical and mental practice (Malouin 2004). However, further research examining the type and intensity of MP, the skills that respond to MP, and the necessary abilities of the individual performing the MP is clearly required.

Previous reviews have reasoned that MP may serve as a useful adjunct to the physical rehabilitation of individuals living with the effects of stroke, or that more research is needed (Batson 2004; Braun 2006; Jackson 2001; Page 2001; Zimmermann‐Schlatter 2008). It is hypothesised that MP may provide individuals undergoing rehabilitation after a stroke the opportunity to increase their amount of practice time, thereby serving to increase the effects of the physical practice that is performed. This review is designed to determine if the current literature supports the use of MP to improve the motor performance of individuals living with the effects of stroke.

A practical definition of MP is as follows. A person participates in MP when he or she adheres to a set of imagined task performances (e.g. picking up a cup) or movements (e.g. reaching out with his or her arm). This visualisation may occur from the first person or third person perspective, and the protocol defines either the number of imagined repetitions or the amount of time the individual invests in the imagining procedure. The imagined movements or tasks are performed without external visual cueing (e.g. watching performance on a videotape) although the training of the imagined procedure may use this modality.

Objectives

To determine if MP improves the outcome of upper extremity rehabilitation for individuals living with the effects of stroke. The review considered outcomes from the Body Structure and Function domain of the ICF as well as from the Activity domain. We also aimed to examine if the effect of MP was influenced by the root cause of the limitation in upper extremity activity (e.g. is MP more effective for individuals who have a sensory rather than motor or perceptual deficit?).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We sought parallel‐group randomised controlled trials (RCTs) for this review. With cross‐over RCTs, we only used the first period for analysis.

Types of participants

We sought studies examining adult survivors of stroke who have deficits in upper extremity function. We used a clinical definition of stroke. Selection of studies was not influenced by the chronicity or the severity of the stroke or the root cause of the activity limitation (e.g. motor versus sensory versus perceptual deficits).

Types of interventions

We looked for trials that incorporated MP of upper extremity movements or tasks. The MP could be a stand‐alone intervention or serve as an adjunct to a conventional intervention. The definition of a conventional intervention varies in the literature and may be described as usual care, or usual physiotherapy or occupational therapy treatment. We sought trials that had the following comparisons:

MP alone versus no intervention;

MP alone versus conventional intervention;

MP alone versus placebo MP (e.g. counting backwards by sevens, mentally manipulating a three‐dimensional object);

MP with conventional intervention versus conventional intervention alone;

MP with conventional intervention versus placebo mental activity with conventional intervention; or

MP plus other therapeutic or novel intervention versus other therapeutic or novel intervention alone.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcomes focused on activity and activity limitations. This included indicators of the ability to perform an upper extremity function (using the arm and hand) and could include tools such as:

the Box and Block test (Mathiowetz 1985);

the TEMPA (Desrosiers 1993);

Action Research Arm Test (Hsieh 1998);

Motor Assessment Scale, upper extremity component (Loewen 1988);

Frenchay Arm Test (Heller 1987);

Wolf Motor Function Test (Wolf 2001); and

components of the Barthel Index (BI) (Mahoney 1965) or the Functional Independence Measure (FIM) (Keith 1987). The Copenhagen Stroke Study used the sum of the feeding and personal toilet items of the BI as a proxy indicator of upper extremity function (Nakayama 1994). Williams 2001 had a similar strategy using the upper body dressing item of the FIM.

We also looked to include hand function tests such as:

the Jebsen Test of Hand Function (Jebsen 1969); and

the Motor Assessment Scale hand (Loewen 1988).

We reviewed all outcomes and planned to combine only those which measured the same concepts.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes focused on changes in body structure or function (that is, impairment) and included those indicators of motor recovery or quality of movement (amount and pattern of movement) of the upper extremity. This included the relevant components of standardised outcome measures such as:

the Fugl‐Meyer Test of Sensorimotor Ability (Fugl‐Meyer 1980); and

the Impairment Inventory of the Chedoke‐McMaster Stroke Assessment (Gowland 1993).

In this category we also included biomechanical analyses of different upper extremity movements, such as that used by:

Alberts 2004 (a key turning task); or

Michaelsen 2004 (a reaching task).

We sought other secondary outcomes that included:

activities of daily living, such as the BI and the FIM;

health‐related quality of life;

indicators of the economic costs of the interventions; and

any measurement of adverse effects of the interventions, including death.

Search methods for identification of studies

See the 'Specialized register' section in the Cochrane Stroke Group module.

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register, which was last searched by the Managing Editor in November 2010. In addition, we searched the following bibliographic databases: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library, November 2009) (Appendix 1), PubMed (1965 to November 2009) (Appendix 2), EMBASE (1980 to November 2009) (Appendix 3), CINAHL (1982 to November 2009) (Appendix 4), PsycINFO (1872 to November 2009) (Appendix 5), Scopus (1996 to November 2009) (Appendix 6), and Web of Science (1955 to November 2009) (Appendix 7), We also searched the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) (http://www.pedro.org.au/), the specialist rehabilitation research databases CIRRIE (http://cirrie.buffalo.edu) and REHABDATA (www.naric.com) (November 2009).

In an effort to identify further published, unpublished and ongoing trials we:

handsearched the following journals from 1999 to April 2010: Australian Journal of Occupational Therapy, Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair, Physical Therapy, and Physiotherapy. To avoid duplication we checked that these were not listed in the Master List of journals already handsearched by The Cochrane Collaboration (http://apps1.jhsph.edu/cochrane/masterlist.asp);

reviewed the reference lists of relevant publications;

-

searched the following ongoing trials registers (November 2009):

ClinicalTrials.gov (http://clinicaltrials.gov/);

NIH Clinical Research Studies Database (http://clinicalstudies.info.nih.gov);

National Research Register (NRR) Archive (https://portal.nihr.ac.uk/Pages/NRRArchive.aspx).

We searched for trials in all languages and arranged translation of trials published in languages other than English.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors (TS, LT) independently screened the titles and abstracts of the citations produced by the literature search and excluded obviously irrelevant studies. Both review authors are rehabilitation professionals (physiotherapist and occupational therapist) with experience in stroke rehabilitation and are familiar with the background material regarding MP. We retrieved the complete text of all remaining citations and reviewed the texts in further detail, selecting those studies that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria. We arranged for one trial in German to be translated. We resolved any disagreement through negotiation, with a third review author (RBG) serving as arbiter as necessary.

The same two review authors (TS, LT) examined the methodological quality of each included trial using the PEDro scale as a template (Moseley 2002). The PEDro scale has 11 criteria that examine aspects of methodology; where allocation concealment is specifically assessed. It produces summary scores that range from 0 to 10, with higher scores representing greater methodological rigour. The complete PEDro scale is available at http://www.pedro.org.au/english/downloads/pedro‐scale/. There is evidence that the PEDro scale provides a more comprehensive indication of methodological quality than the Jadad scale (Bhogal 2005). We resolved differences as described above. We have provided information on study characteristics, quality and biases, as well as deaths and drop‐outs in the Characteristics of included studies table.

The same two review authors (TS, LT) also extracted data from the included trials. We included immediate post‐intervention assessment along with any follow‐up assessment findings. We carried out an analysis when the review produced a minimum of two trials employing a particular intervention strategy and examining a common outcome. We used the Cochrane Review Manager software (RevMan 2008) for all data analyses.

All outcomes produced continuous data. We calculated the mean difference (MD) and 95% confidence interval (CI) when identical measures were combined. We used the standardised mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI for different outcomes that measured the same constructs. We carried out analyses with the random‐effects model due to heterogeneity across some of the outcomes. We analysed trials for statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, which describes the percentage of variability in the effect estimates due to heterogeneity. If the I2 was greater than 50%, we combined outcomes using the SMD, and used a random‐effects model. We used intention‐to‐treat analyses whenever possible.

We completed a subgroup analysis, based on time since stroke; however, only one study was less than six months post stroke, not enabling true comparison. We carried out subgroup analysis based on the dosage of MP (total time of MP over the course of the study), with less than or equal to 360 minutes versus greater than 360 minutes of total MP time. We looked for variations in the root cause of activity limitation, such as strength, sensation, and perception; working memory; presence versus absence of cognitive impairment; and conventional versus non‐conventional or other treatment.

Results

Description of studies

Our comprehensive searches retrieved 1100 articles, of which 29 were reviewed in full. We initially included 10 of the 29 articles; however, on closer inspection, we decided to exclude four of them (Bovend'Eerdt 2010; Hemmen 2007; Liu 2004; Miltner 1999), leaving six studies with a total of 119 participants for inclusion (Müller 2007; Page 2001; Page 2005; Page 2007; Page 2009; Riccio 2010). Of the six studies included, we could combine data from a total of 102 participants in five studies (Page 2001; Page 2005; Page 2007; Page 2009; Riccio 2010).

Included studies

Details of the six included studies can be found in the Characteristics of included studies table. The included studies were all randomised trials, one of which was a randomised cross‐over trial (Riccio 2010). In one study, data were presented as slopes of mean change (Müller 2007), one study presented change scores (Riccio 2010), and another did not present standard deviations for all outcomes (Page 2005). We contacted the authors of these three studies for further information, leading to data that could be used for the analysis from Müller 2007 and Riccio 2010.

Müller 2007 had six participants in the MP group, six in a motor practice group, and five in a conventional treatment group. Riccio 2010 reported 18 participants in the MP group and 18 in a conventional treatment group. Page 2009 included five participants in a modified constraint‐induced movement therapy plus MP group and five in a modified constraint‐induced movement therapy only group. Page 2005 had six participants in the physical practice with MP group and five participants in the physical practice plus placebo MP group (relaxation). Page 2007 included 16 participants in the physical practice plus MP group and 16 participants in the physical practice plus placebo MP (relaxation) group. Page 2001 reported eight participants in the physical practice plus MP group as well as five participants in the physical practice plus placebo MP (stroke information) group.

Comparisons used in the trials were as follows: MP alone versus conventional intervention (Müller 2007); MP alone versus motor practice (Müller 2007); MP with conventional intervention versus conventional intervention alone (Page 2009; Riccio 2010); MP with conventional intervention versus placebo mental activity with conventional intervention (Page 2001; Page 2005; Page 2007). Although the Page 2009 study used modified constraint‐induced movement therapy, we considered it a type of 'conventional' therapy, as it entailed primarily physical practice of tasks with an increased practice time. One study had three‐month follow‐up data, but the standard deviation was missing for one of the groups at follow‐up (Page 2009).

Treatment intensity varied across studies from twice weekly to daily, 30 to 60 minutes per session, and three to 10 weeks in length. All studies except for two (Müller 2007; Riccio 2010) included participants greater than six months post stroke.

The outcomes of all trials included activity level outcomes of upper extremity function. Upper extremity function outcomes included the Action Research Arm Test (Page 2001; Page 2005; Page 2007; Page 2009), the Arm Function Test (Riccio 2010), and the Jebsen hand function test with scores from individual items (Müller 2007). The Arm Function Test was not clearly described (Riccio 2010). Impairment level outcomes included motor recovery of the upper extremity (Page 2001; Page 2005; Page 2007; Page 2009; Riccio 2010) and pinch grip strength (Müller 2007). Motor recovery outcomes included the Fugl‐Meyer Upper extremity (Page 2001; Page 2007; Page 2009), the Motricity Index (Riccio 2010), and the Motor Activity Log ‐ Quality of Movement (Page 2005). The last outcome could not be utilised due to lack of standard deviation information.

We did not find other secondary outcomes of activities of daily living, health‐related quality of life, indicators of the economic costs of the interventions or any measurement of adverse effects of the interventions, including death.

Excluded studies

The three excluded studies are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. From the published abstract, one study appeared appropriate for inclusion. However, the text of the article was in German and when the text was translated, it was apparent that the study was not randomised (Miltner 1999). We excluded Liu 2004 as the intervention was not specific to the upper extremity, and Hemmen 2007 only imagined one isolated muscle movement.

Ongoing studies

We identified six ongoing studies relevant to this review (Braun 2007; Butler 2008; Ietswaart 2006; Johnston 2006; Page 2009; Verbunt 2008). However, Johnston 2006 and Ietswaart 2006 appear to be the same study. Details of these studies are available in the Characteristics of ongoing studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

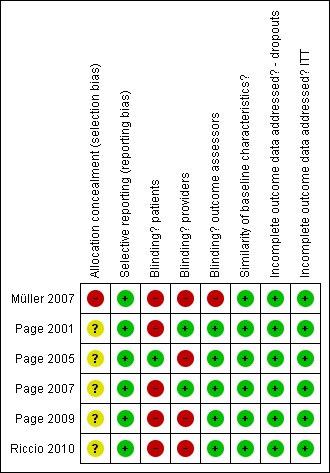

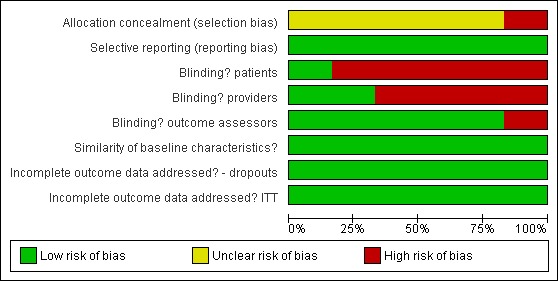

The six studies came from three countries (Germany, Italy and the USA). We evaluated all studies with the PEDro scale; they received scores from 6 to 9 out of 10. We used this information to evaluate the risk of bias. See 'Risk of bias summary' (Figure 1) and 'Risk of bias graph' (Figure 2). Further information is available in the Summary of findings table 1. Four of the six studies were from the same author (Page 2001; Page 2005; Page 2007; Page 2009). The author confirmed with us that the four studies occurred with different participants, in different projects and were in different locations.

Figure 1.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

The GRADE quality of evidence across the studies was determined to be moderate. In summary, allocation concealment was not always clear across studies. Blinding is very difficult in rehabilitation intervention trials, as it is hard ‐ if not impossible ‐ to blind participants and treatment providers. In most of the studies, however, the outcomes assessors were blinded. All six trials appeared free of selective reporting, had similar baseline characteristics and it appeared that the authors had accounted for all data.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

To determine if MP helps improve the outcome of upper extremity rehabilitation for individuals living with the effects of stroke, we evaluated various comparisons for the primary outcome of activity (upper extremity function)as well as the secondary outcome of impairment (recovery of function/quality of movement of the upper extremity). The comparisons evaluated were as follows:

MP and other treatment versus other treatment;

MP with conventional intervention versus placebo mental activity with conventional intervention (Page 2001; Page 2005; Page 2007);

MP with conventional intervention versus conventional intervention alone (Page 2009; Riccio 2010);

MP alone versus conventional intervention (Müller 2007); and

MP alone versus motor practice (Müller 2007).

For some comparisons there was only one study, so studies could not be combined. We combined the comparisons of 'MP with conventional intervention versus conventional intervention alone' and 'MP with conventional intervention versus placebo mental activity with conventional intervention' together as 'MP in addition to other treatment versus other treatment'. We further subdivided this overall comparison into greater than and less than six months post stroke, although only one study had data for participants less than six months post stroke (Riccio 2010). We also completed a second subgroup analysis of dosage of MP.

Results of meta‐analyses

MP and other treatment versus other treatment

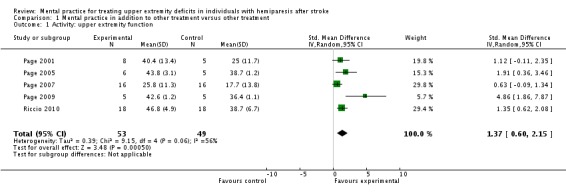

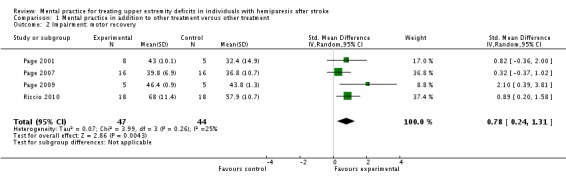

Data were available from five studies (Page 2001; Page 2005; Page 2007; Page 2009; Riccio 2010) that randomised a total of 102 participants. There was 'moderate' heterogeneity (I2 = 56%) across the activity‐upper extremity function outcomes in these studies and, therefore, we used the random‐effects model for this and all other analyses. The test for overall effect was statistically significant (SMD 1.37, 95% CI 0.60 to 2.15) favouring MP combined with other treatment compared to other treatment alone (Analysis 1.1). Four studies randomising 91 participants (Page 2001; Page 2007; Page 2009; Riccio 2010) reported impairment‐motor recovery outcomes. We found a significant effect favouring MP (SMD 0.78, 95% CI 0.24 to 1.31) (Analysis 1.2). See Summary of findings table 1 ‐ values in column 'Corresponding risk' are with random effects; fixed‐effect values are in the 'Comments' column.

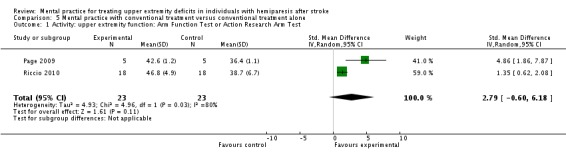

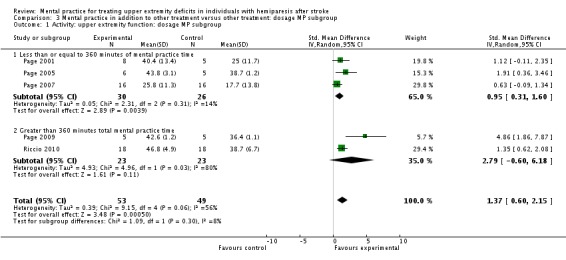

Analysis 1.1.

Comparison 1 Mental practice in addition to other treatment versus other treatment, Outcome 1 Activity: upper extremity function.

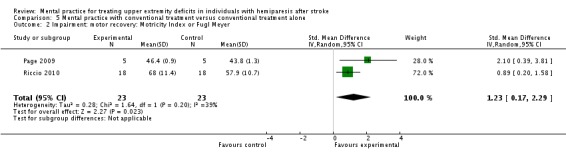

Analysis 1.2.

Comparison 1 Mental practice in addition to other treatment versus other treatment, Outcome 2 Impairment: motor recovery.

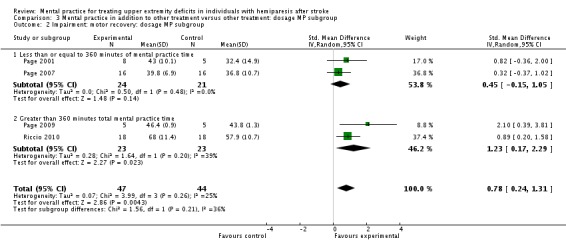

MP and other treatment versus other treatment: time post stroke analysis

We formed subgroups on the basis of the time since participants' stroke. One trial (Riccio 2010) studied participants who were less than six months post stroke; four trials (Page 2001; Page 2005; Page 2007; Page 2009; 66 participants randomised) studied participants who were more than six months post stroke. There was 'substantial' heterogeneity (I2 = 66%) across the activity‐upper extremity function outcomes for the trials using participants who were more than six months post stroke; we found a significant effect favouring MP (SMD 1.55, 95% CI 0.38 to 2.72) (Analysis 2.1). Three studies (Page 2001; Page 2007; Page 2009) randomising 55 participants reported impairment‐motor recovery outcomes. We did not identify any significant effect (SMD 0.82, 95% CI ‐0.06 to 1.70) (Analysis 2.2).

Analysis 2.1.

Comparison 2 Mental practice in addition to other treatment versus other treatment: time post stroke subgroup, Outcome 1 Activity: upper extremity function.

Analysis 2.2.

Comparison 2 Mental practice in addition to other treatment versus other treatment: time post stroke subgroup, Outcome 2 Impairment: motor recovery.

MP and other treatment versus other treatment: dosage of treatment analysis

We formed subgroups on the basis of the amount of time MP was performed. For the activity‐upper extremity function outcomes, three studies (Page 2001; Page 2005; Page 2007), randomising 56 participants, provided less than 360 minutes of MP (MPsmall); two studies (Page 2009; Riccio 2010), randomising 46 participants, provided more than 360 minutes of MP (MPlarge).

For the MPsmall studies, we found a significant effect for the activity‐upper extremity function outcomes (SMD 0.95, 95% CI 0.31 to 1.60) with no significant degree of heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 14%). For the MPlarge studies, we found no effect (SMD 2.79, 95% CI ‐0.60 to 1.60) with 'substantial' heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 80%).

For the impairment‐motor recovery outcomes, we found the opposite results with the two studies (Page 2001; Page 2007) using MPsmall dosage showing non‐significant findings (SMD 0.45, 95% CI ‐0.15 to 1.05) while the MPlarge studies showed a significant finding (SMD 1.23, 95% CI 0.17 to 2.29).

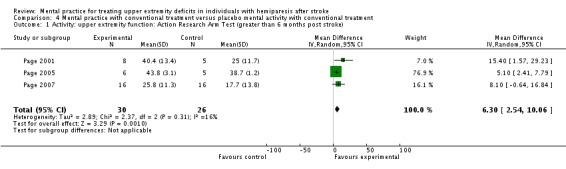

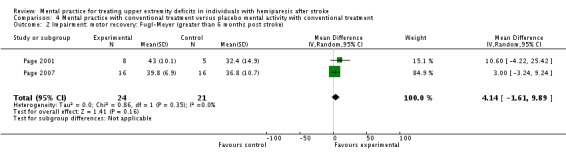

MP with conventional treatment versus placebo MP with conventional treatment

In the comparison 'MP with conventional treatment versus placebo mental activity with conventional treatment ', we included three studies involving 56 participants (Page 2001; Page 2005; Page 2007). For the outcome of activity‐upper extremity function, the outcome measure used across all three studies was the Action Research Arm Test, thus we combined all outcomes using the MD (Analysis 4.1). There was no significant heterogeneity, with an I2 of 16%. The overall test of effect (MD 6.30, 95% CI 2.54 to 10.06)) favours mental practice combined with conventional treatment over placebo mental activity combined with conventional intervention in addressing upper extremity function in individuals more than six months post stroke. For the outcome of impairment‐motor recovery, we could only combine two studies involving 45 participants (Page 2001; Page 2007) because the SD was not available for this outcome in Page 2005. Both studies used Fugl‐Meyer as a test of motor recovery/quality of movement; we used the MD (Analysis 4.2). We did not consider heterogeneity to be an issue, with I2 of 0%. In this outcome, the test for overall effect was not significant (MD 4.14, 95% CI ‐1.61 to 9.89).

Analysis 4.1.

Comparison 4 Mental practice with conventional treatment versus placebo mental activity with conventional treatment, Outcome 1 Activity: upper extremity function: Action Research Arm Test (greater than 6 months post stroke).

Analysis 4.2.

Comparison 4 Mental practice with conventional treatment versus placebo mental activity with conventional treatment, Outcome 2 Impairment: motor recovery: Fugl‐Meyer (greater than 6 months post stroke).

MP with conventional treatment versus conventional treatment alone

With the 'MP with conventional treatment versus conventional treatment alone' comparison, we combined two studies (Page 2009; Riccio 2010). For activity‐upper extremity function, the results were the same as the more than 360 minute subgroup comparison above, since the same studies were combined. Results were not significant, and heterogeneity was substantial (Analysis 5.1).

Analysis 5.1.

Comparison 5 Mental practice with conventional treatment versus conventional treatment alone, Outcome 1 Activity: upper extremity function: Arm Function Test or Action Research Arm Test.

In the impairment‐motor recovery outcome, results were also the same as in the more than 360 minute subgroup comparison, which showed a statistically significant effect (SMD 1.23, 95% CI 0.17 to 2.29) with moderate heterogeneity of I2 = 39% (Analysis 5.2).

Analysis 5.2.

Comparison 5 Mental practice with conventional treatment versus conventional treatment alone, Outcome 2 Impairment: motor recovery: Motricity Index or Fugl Meyer.

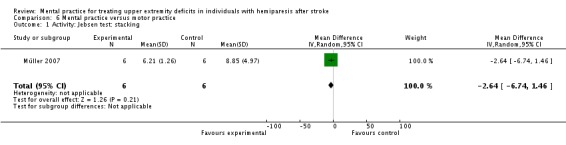

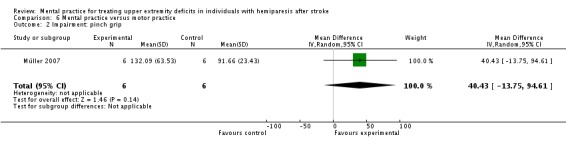

MP alone versus motor practice

Due to the comparisons used, we could not combine Müller 2007 with other studies. The MP alone versus motor practice comparison is seen in Analysis 6.1 and Analysis 6.2. For activity‐upper extremity function, the stacking item of the Jebsen Test of Hand Function is demonstrated in Analysis 6.1. The total score of the Jebsen Test is not described in the study, just the individual items. Since this is a timed test, the lower score is the better score. The impairment outcome is represented by pinch grip strength (Analysis 6.2).

Analysis 6.1.

Comparison 6 Mental practice versus motor practice, Outcome 1 Activity: Jebsen test: stacking.

Analysis 6.2.

Comparison 6 Mental practice versus motor practice, Outcome 2 Impairment: pinch grip.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We included six studies involving a total of 119 participants; we combined data from 102 participants in five studies. We combined studies for the comparisons 'MP in addition to other treatment versus other treatment': 'MP with conventional treatment versus placebo mental activity with conventional treatment' and 'MP with conventional treatment versus conventional treatment alone'.

The primary outcome for this review was from the activity domain ‐ upper extremity function. Mental practice in combination with other treatment appears more effective in improving upper extremity function than the other treatment alone for the 'MP in addition to other treatment versus other treatment' and 'MP with conventional treatment versus placebo mental activity with conventional treatment' comparisons. The 'MP with conventional treatment versus conventional treatment alone' comparison was not significant; it is likely that the studies were too different to be combined together. For the subgroup analysis of dosage of MP, the more than 360 minutes of MP subgroup was not statistically significant with a random‐effects model.

For the secondary outcome in the impairment domain of motor recovery/quality of movement, results were not consistent across the comparisons. For 'MP with conventional intervention versus placebo mental activity with conventional intervention', there was no difference between the groups. In the comparison of 'MP in addition to other treatment versus other treatment', we only noted a statistically significant difference when one study with participants less than six months post stroke was added to the studies with participants more than six months post stroke. Using subgroups of the dosage of MP used over the course of the study, less than or equal to 360 minutes suggested no difference between groups.

It is important to note that the subgroup analyses used small numbers of studies with a small overall sample size, so results should be interpreted with care. Heterogeneity appears to have affected some of the outcomes. The results, however, lead to further questions regarding the effectiveness of MP on motor recovery in individuals with chronic stroke, and what dosage or intensity of MP may be effective.

Finally, none of the studies included an indicator of the safety of the intervention (e.g. an accounting of any adverse events associated with MP performance). While the nature of MP lends itself to a widely held assumption that it can be performed without any harm, formal evaluation of this is needed. Moreover, the widely held assumption that MP would be a clinically feasible adjunct to conventional physical rehabilitation interventions has been called into question by two recent studies that documented lower than expected indicators of adherence by both therapists and participants to MP protocols that had been individualised to the participants (Bovend'Eerdt 2010; Braun 2010).

Quality of the evidence

We evaluated the quality of the evidence with the PEDro scale, with the evidence ranging from 6 to 9 out of 10; see the Characteristics of included studies table. The GRADE score (in the Table 1) was determined to be moderate for the combined 'MP in addition to other treatment versus other treatment' comparison outcomes based on inconsistent evidence about allocation concealment and difficulties in blinding participants and those providing treatment due to the type of study. These may represent a problem with the reporting of the findings rather the design of the study and, therefore, ongoing attention to reporting guidelines, such as CONSORT, seems to be required.

Potential biases in the review process

We attempted to decrease potential bias in the review by having non‐English studies translated. Two review authors assessed the quality of the studies and extracted data, with a third review author available to resolve disagreements as necessary.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies and reviews

Our search strategy identified the same studies that had been identified previously by two other systematic reviews of the literature (Braun 2006; Zimmermann‐Schlatter 2008). We, like Zimmerman‐Schlatter, chose to exclude the case‐control trial by Dijkerman 2004. However, we also excluded Liu 2004. Our search strategy generated four additional studies (Müller 2007; Page 2007; Page 2009; Riccio 2010) that met the inclusion criteria and were published after the two previous reviews. Despite an additional 95 participants, difficulty in combining studies for meta‐analysis reported by both previous reviews persisted in our attempt to use meta‐analysis to summarize the findings. There is reason to be optimistic that there will be ample opportunity for combining studies in future given the five ongoing projects that we identified (see the Characteristics of ongoing studies table; total sample size is anticipated to be 485 participants).

Authors' conclusions

There is limited evidence that mental practice (MP) in combination with other rehabilitation treatment appears to be beneficial in improving upper extremity function after stroke as compared with other rehabilitation treatment without MP. Clinicians may consider utilising MP in addition to their current treatment to enhance upper extremity function in individuals after stroke. Considerations should be made regarding the ability of the patient to imagine the necessary movement, and preparing the patient to be able to imagine the movement. No evidence of harm or side effects has been noted in the literature. Evidence regarding improvement in motor recovery and quality of movement at differing times post stroke is less clear. There is no clear pattern regarding the 'ideal' dosage of MP required to improve outcomes.

Are further RCTs required?

At this point, we recommend that design of further RCTs should wait until the results of the numerous ongoing studies regarding MP for upper extremity function in survivors of stroke are available. The ongoing studies are recruiting participants in the acute, sub‐acute and chronic phases of recovery from stroke, measuring outcomes from all domains of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) and obtaining immediate and follow‐up measures. It seems likely that identification of both optimal dosage of MP and optimal patient characteristics will continue to be issues for further consideration.

Are further systematic reviews required?

As mentioned above, future systematic reviews should provide further information into the benefit of MP for treating upper extremity deficits in individuals after stroke, since there are numerous studies ongoing.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Dr Ilaria Riccio and Dr Katharina Müller for sharing outcomes in the format that could be used for analysis, and to Dr Stephen Page for answering our questions.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor Cerebrovascular Disorders explode all trees #2 MeSH descriptor Brain Injuries explode all trees #3 MeSH descriptor Nervous System Diseases explode all trees #4 MeSH descriptor Paresis explode all trees #5 MeSH descriptor Hemiplegia explode all trees #6 MeSH descriptor Dystonia explode all trees #7 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6) #8 stroke or cerebrovascular or “cerebral vascular” or hemipleg* or paresis or pareses or hemipares* or parapares* or paretic or hemiparetic or paraparetic or dystoni* in All Fields #9 (#8 OR #7) #10 MeSH descriptor Imagery (Psychotherapy) explode all trees #11 MeSH descriptor Imagination #12 (“mental practice” or imagery or imagining or imagination or “mental representation” or “motor ideation” or “cognitive rehearsal” or cognitive rehearsing or cognitively rehearse or cognitively rehearsed or covert rehearsal or covert rehearsing or covertly rehearse or covertly rehearsed or mental rehearsal or mental rehearsing or mentally rehearse or mentally rehearsed) in All Fields #13 (#10 OR #11 OR #12) #14 MeSH descriptor Upper Extremity explode all trees #15 “upper extremity” or “upper extremities” or “upper limb” or “upper limbs’ or hand or hands or finger or fingers or arm or arms or shoulder* in All Fields #16 (#14 OR #15) #17 (#16 AND #13 AND #9)

Appendix 2. PubMed search strategy

1. "Cerebrovascular Disorders"[MeSH] OR "Brain Injuries"[MeSH] OR "Nervous System Diseases"[MeSH] OR "Nervous System Diseases"[MeSH] OR "Hemiplegia"[MeSH] OR "Paresis"[MeSH] OR "Dystonia"[MeSH] 2. stroke[tw] OR cerebrovascular[tw] OR cerebral vascular[tw] OR hemipleg*[tw] OR paresis[tw] OR pareses[tw] OR hemipares*[tw] OR parapares*[tw] OR paretic[tw] OR hemiparetic[tw] OR paraparetic[tw] OR dystoni*[tw] 3. #1 OR #2 4. "Imagery (Psychotherapy)"[MeSH] OR "Imagination"[MeSH:noexp] 5. imagery[tw] OR imagining[tw] OR imagination[tw] OR "mental representation"[tw] OR "motor ideation"[tw] OR "mental practice"[tw] OR "mentally practice"[tw] OR "mentally practicing"[tw] OR "mental practices"[tw] OR "mentally practiced"[tw] OR "mental rehearsal"[tw] OR "mental rehearsing"[tw] OR "mentally rehearsed"[tw] OR "mentally rehearse"[tw] OR “cognitive rehearsal” [tw] OR “cognitive rehearsing” [tw] OR “cognitively rehearse” [tw] OR “cognitively rehearsed” [tw] OR “covert rehearsal” [tw] OR “covert rehearsing” [tw] OR “covertly rehearse” [tw] OR “covertly rehearsed” [tw] 6. #4 OR #5 7. "Upper Extremity"[MeSH] 8. "upper extremity"[tw] OR "upper extremities"[tw] OR "upper limb"[tw] OR "upper limbs"[tw] OR hand[tw] OR hands[tw] OR finger[tw] OR fingers[tw] OR arm[tw] OR arms[tw] OR shoulder[tw] OR shoulders[tw] 9. #7 OR #8 10. #3 AND #6 AND #9

Appendix 3. EMBASE search strategy

EMBASE OvidSP

1. exp cerebrovascular‐disease/ or exp neurologic‐disease/ or paresis/ or exp hemiplegia/ or hemiparesis/ or dystonia/ 2.(stroke or cerebrovascular or cerebral vascular or brain injur$ or hemipleg$ or paresis or pareses or hemipares$ or parapares$ or paretic or hemiparetic or paraparetic or dystoni$). ti.ab. 3. 1 or 2 4. imagery/ or imagination/ 5. (mental$ adj3 practic$).tw. or (cognitive$ adj3 rehears$).tw. or (covert$ adj3 rehears$).tw. or (mental$ adj3 rehears$).tw. 6.(imagery or imagining or imagination or mental representation$ or motor ideation).tw. 7. 4 or 5 or 6 8.exp arm/ 9.(upper extremit$ or upper limb$ or hand or hands or finger or fingers or arm or arms or shoulder$).ti,ab. 10. 8 or 9 11. 3 and 7 and 10

Appendix 4. CINAHL search strategy

CINAHL EbscoHost

1. (MH "Cerebrovascular Disorders+") or (MH "Stroke Patients") or (MH "Hemiplegia") or (MH "Dystonia+") 2. AB ( stroke or cerebrovascular or cerebral vascular or hemipleg* or paresis or pareses or hemipares* or parapares* or paretic or hemiparetic or paraparetic or dystoni* ) or TI ( stroke or cerebrovascular or cerebral vascular or hemipleg* or paresis or pareses or hemipares* or parapares* or paretic or hemiparetic or paraparetic or dystoni* ) 3. S1 or S2 4. (MH "Guided Imagery") or (MH "Imagination") 5. AB (mental* N3 practic*) or TI (mental* N3 practic*) or TI (cognitiv* N3 rehears* or covert* N3 rehears* or mental* N3 rehears*) or AB (cognitiv* N3 rehears* or covert* N3 rehears* or mental* N3 rehears*) 6. AB ( imagery or imagining or imagination or mental representation* or motor ideation ) or TI ( imagery or imagining or imagination or mental representation* or motor ideation ) 7. S4 or S5 or S6 8. MH "Upper Extremity+" 9. AB ( upper extremit* or upper limb* or hand or hands or arm or arms or finger or fingers or shoulder* ) or TI ( upper extremit* or upper limb* or hand or hands or arm or arms or finger or fingers or shoulder* ) 10. S8 or S9 11. S3 and S7 and S10

Appendix 5. PsycINFO search strategy

PsycINFO OvidSP

1. exp Cerebrovascular Disorders/ or exp Brain Damage/ or exp Nervous System Disorders/ or exp General Paresis/ or exp Hemiplegia/ or exp Muscular Disorders/ 2. (stroke or cerebrovascular or cerebral vascular or brain injur$ or hemipleg$ or paresis or pareses or hemipares$ or parapares$ or paretic or hemiparetic or paraparetic or dystoni$).ti,ab,sh,id. 3. 1 or 2 4. exp Imagery/ or exp Guided Imagery/ or exp Ideation/ or exp Imagination/ 5. (imagery or imagining or imagination or mental representation$ or ideation or visuali$).ti,ab,sh,id. or (cognitive$ adj3 rehears$).ti,ab,sh,id. or (covert$ adj3 rehears$). ti,ab,sh,id. or (mental$ adj3 rehears$). ti,ab,sh,id. 6. 4 or 5 7. exp "arm (anatomy)"/ or exp wrist/ or exp "shoulder (anatomy)"/ or exp "hand (anatomy)"/ or exp "elbow (anatomy)"/ or exp "fingers (anatomy)"/ 8. (upper extremit$ or upper limb$ or hand or hands or finger or fingers or arm or arms or shoulder$).ti,ab,sh,id. 9. 7 or 8 10. 3 and 6 and 9

Appendix 6. Scopus search strategy

1. TITLE‐ABS‐KEY (stroke or cerebrovascular or cerebral vascular or brain injur* or hemipleg* or paresis or pareses or hemipares* or parapares* or paretic or hemiparetic or paraparetic or dystoni*) 2. TITLE‐ABS‐KEY(mental* W/3 practic*) or TITLE‐ABS‐KEY(imagery or imagining or imagination or mental representation* or motor ideation) or TITLE‐ABS‐KEY(cognitiv* W/3 rehears*) OR TITLE‐ABS‐KEY(covert* W/3 rehears*) OR TITLE‐ABS‐KEY(mental* W/3 rehears*) 3. TITLE‐ABS‐KEY(upper extremit* OR upper limb* OR hand OR hands OR finger OR fingers OR arm OR arms OR shoulder*) 4. #1 and #2 and #3

Appendix 7. Web of Science search strategy

1. Topic=(stroke or cerebrovascular or cerebral vascular or hemipleg* or paresis or pareses or hemipares* or parapares* or paretic or hemiparetic or paraparetic or dystoni*) 2. Topic=((mental* same practic*) or imagery or imagining or imagination or mental representation or motor ideation) or Topic=(cognitiv* same rehears*) OR Topic=(covert* same rehears*) OR Topic=(mental* same rehears*) 3. Topic=(upper extremit* or upper limb* or hand or hands or finger or fingers or arm or arms or shoulder*) 4. #1 and #2 and #3

Data and analyses

Comparison 1.

Mental practice in addition to other treatment versus other treatment

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Activity: upper extremity function | 5 | 102 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.37 [0.60, 2.15] |

| 2 Impairment: motor recovery | 4 | 91 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.24, 1.31] |

Comparison 2.

Mental practice in addition to other treatment versus other treatment: time post stroke subgroup

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Activity: upper extremity function | 5 | 102 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.37 [0.60, 2.15] |

| 1.1 Greater than 6 months post stroke | 4 | 66 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.55 [0.38, 2.72] |

| 1.2 Less than 6 months post stroke | 1 | 36 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.35 [0.62, 2.08] |

| 2 Impairment: motor recovery | 4 | 91 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.24, 1.31] |

| 2.1 Greater than 6 months post stroke | 3 | 55 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.82 [‐0.06, 1.70] |

| 2.2 Less than 6 months post stroke | 1 | 36 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.20, 1.58] |

Comparison 3.

Mental practice in addition to other treatment versus other treatment: dosage MP subgroup

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Activity: upper extremity function: dosage MP subgroup | 5 | 102 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.37 [0.60, 2.15] |

| 1.1 Less than or equal to 360 minutes of mental practice time | 3 | 56 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.31, 1.60] |

| 1.2 Greater than 360 minutes total mental practice time | 2 | 46 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 2.79 [‐0.60, 6.18] |

| 2 Impairment: motor recovery: dosage MP subgroup | 4 | 91 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.24, 1.31] |

| 2.1 Less than or equal to 360 minutes of mental practice time | 2 | 45 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.45 [‐0.15, 1.05] |

| 2.2 Greater than 360 minutes total mental practice time | 2 | 46 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.23 [0.17, 2.29] |

Analysis 3.1.

Comparison 3 Mental practice in addition to other treatment versus other treatment: dosage MP subgroup, Outcome 1 Activity: upper extremity function: dosage MP subgroup.

Analysis 3.2.

Comparison 3 Mental practice in addition to other treatment versus other treatment: dosage MP subgroup, Outcome 2 Impairment: motor recovery: dosage MP subgroup.

Comparison 4.

Mental practice with conventional treatment versus placebo mental activity with conventional treatment

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Activity: upper extremity function: Action Research Arm Test (greater than 6 months post stroke) | 3 | 56 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 6.30 [2.54, 10.06] |

| 2 Impairment: motor recovery: Fugl‐Meyer (greater than 6 months post stroke) | 2 | 45 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 4.14 [‐1.61, 9.89] |

Comparison 5.

Mental practice with conventional treatment versus conventional treatment alone

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Activity: upper extremity function: Arm Function Test or Action Research Arm Test | 2 | 46 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 2.79 [‐0.60, 6.18] |

| 2 Impairment: motor recovery: Motricity Index or Fugl Meyer | 2 | 46 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.23 [0.17, 2.29] |

Comparison 6.

Mental practice versus motor practice

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Activity: Jebsen test: stacking | 1 | 12 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.64 [‐6.74, 1.46] |

| 2 Impairment: pinch grip | 1 | 12 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 40.43 [‐13.75, 94.61] |

What's new

Last assessed as up‐to‐date: 15 December 2010.

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 16 June 2011 | Amended | Correction to graph labels for outcomes 1.1 and 1.2 |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2006 Review first published: Issue 5, 2011

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 21 August 2009 | New citation required and minor changes | The protocol has been revised and updated. |

| 12 August 2009 | Amended | The Published notes section has been amended. |

| 26 February 2009 | Amended | The reason for the protocol's withdrawal has been amended. |

| 2 February 2009 | Amended | The protocol has been withdrawn from publication. |

| 9 July 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Differences between protocol and review

We did not search the AMED database, as it is no longer available at our library.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Müller 2007

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial with "a pre‐set randomization plan" Setting: apparently in the clinic/research laboratory | |

| Participants | 6 in experimental group, 6 in motor practice group, 5 in conventional group; mean 28.7 (21.2) days post stroke; mean age 62 (10) years; 65% male; stroke severity ‐ European Stroke Scale 92/100, Barthel Index 98/100; hand dominance 16 right, 1 left; affected extremity and concordance not noted | |

| Interventions | 30 minute sessions; 5 days/week for 4 weeks MP dosage (total number of minutes of MP over the study) = 600 minutes Intervention: initially, cued to desired movements by watching a video tape of a hand in the desired pattern. For training, after being reminded of the movement sequence, experimental participants would mentally rehearse the sequence and (to) imagine (to) perform(ing) the movement sequence with the affected hand mentally. A researcher supervised the mental rehearsing so as to ensure no movements were actually performed. There was a check that mental rehearsal was occurring (indicate correct position of the thumb every 2 minutes) Motor practice control: practiced non‐sequential finger opposition, following videotaped sequence at 1 Hz with 450 repetitions per sequence for 1 minute; task was then performed by memory Conventional control: OT and PT ‐ training of hand functions ‐ grasping, extending the fingers, holding objects (no repetitive or isolated finger movements) | |

| Outcomes | Pinch and grip strength Jebsen hand function (individual items) | |

| Notes | PEDro score 6/10 Compared intervention and conventional control They did not analyse the raw findings ‐ instead, looked at values normalised to baseline and then the slopes of the regression lines between the assessment points | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Unspecified randomisation procedure |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Selective reporting not evident |

| Blinding? patients | High risk | There is no specific comment regarding blinding of patients; however, there is an active control group that received a dose‐matched defensible intervention |

| Blinding? providers | High risk | Blinding of treatment providers is not stated |

| Blinding? outcome assessors | High risk | Blinding of assessors is not stated |

| Similarity of baseline characteristics? | Low risk | There were no baseline differences among groups for pinch grip strength or Jebsen test performance |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? ‐ dropouts | Low risk | There were no dropouts |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? ITT | Low risk | All participants were analysed in the group to which they were randomised |

Page 2001

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial with "computer‐generated random numbers table" Setting: quiet room in the therapy department then repeated again at home | |

| Participants | 8 in experimental group, 5 in control group; mean 6.5 (3.3) months post stroke; mean age 64.6 (8.4) years; 77% male; no measure of stroke severity; hand dominance ‐ right 4, left 9; affected extremity ‐ right 4, left 9; concordance 13/13 | |

| Interventions | Approximately 10 minutes, 3 sessions/week for 6 weeks MP dosage (total number of minutes of MP over the study) = 180 minutes Intervention: the physical intervention as described below followed by listening to audiotapes that included 2 to 3 minutes of relaxation and 7 to 8 minutes of images involving using the affected extremity in functional tasks. 3 scripts were used with a new script introduced every 2 weeks Control: 3 x 60 minute sessions/week for 6 weeks of practicing ADL or ambulation tasks plus listening to a 10 minute tape containing stroke information | |

| Outcomes | Fugl‐Meyer Upper extremity Action Research Arm Test | |

| Notes | PEDro score 9/10 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomised by a computer‐generated random numbers table |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Selective reporting not evident |

| Blinding? patients | High risk | No comment regarding methods used to blind the patients |

| Blinding? providers | Low risk | Therapists were blinded to participants' groupings |

| Blinding? outcome assessors | Low risk | Outcomes were assessed by a blinded rater |

| Similarity of baseline characteristics? | Low risk | The groups were comparable at baseline in terms of Fugl‐Meyer and Action Research Arm tests |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? ‐ dropouts | Low risk | There were no dropouts |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? ITT | Low risk | All participants were analysed in the group to which they were randomised |

Page 2005

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial with "random numbers table" Setting: outpatient clinic where they had been doing their rehabilitation prior to enrolment in the study | |

| Participants | 6 in experimental group, 5 in control group; mean 23.8 months post stroke; mean age 62.8 (5.1) years; 82% male; no measure of stroke severity; concordance 10/11 | |

| Interventions | 30 minutes; 2 sessions/week for 6 weeks MP dosage (total number of minutes of MP over the study) = 360 minutes Intervention: physical practice of ADL for 30 minutes, twice a week for 6 weeks followed by MP of the same ADL prompted by audiotape (5 minutes of relaxation, 20 to 25 minutes of "internal, cognitive polysensory images related to using the affected arm in the functional tasks" that had been practiced in the physical rehabilitation component, followed by 3 to 5 minutes of refocusing into the room Control: physical practice of ADL as in the intervention group but followed by 30 minutes of progressive relaxation prompted by audiotape | |

| Outcomes | Action Research Arm Test Motor Activity Log: amount of use Motor Activity Log: quality of movement Caregiver Motor Activity Log: amount of use Caregiver Motor Activity Log: quality of movement | |

| Notes | PEDro score 8/10 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomisation by a random numbers table |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Selective reporting not evident |

| Blinding? patients | Low risk | The control intervention was designed to give the same amount of contact with a therapist in a similar setting. It is suggested that the participants do not realise they are receiving the control intervention |

| Blinding? providers | High risk | There are no statements regarding blinding of providers |

| Blinding? outcome assessors | Low risk | Examiners were blinded to patients’ experimental condition |

| Similarity of baseline characteristics? | Low risk | The groups were comparable at baseline in terms of Motor Activity Log and Action Research Arm tests |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? ‐ dropouts | Low risk | There were no dropouts |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? ITT | Low risk | All participants were analysed in the group to which they were randomised. |

Page 2007

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial with "computer‐generated random numbers table" Setting: all in the same environment, presumably a research laboratory or outpatient clinic | |

| Participants | 16 in experimental group, 16 in control group; mean 42 months post stroke; mean age 59.5 (13.4) years; 52% male; no measure of stroke severity; hand dominance not described; affected extremity ‐ right 19, left 13; concordance not described | |

| Interventions | 30 minutes, 2 sessions/week for 6 weeks MP dosage (total number of minutes of MP over the study) = 360 minutes Intervention: physical practice of ADL activities for 30 minutes/session, 2 sessions/week for 6 weeks plus MP of the same ADL activities prompted by audiotape with middle 20 minutes having suggestions for internal, cognitive polysensory images to cue the participant to mentally rehearse the motor skill practiced earlier in the day. Of note, the images were in the first person perspective, and the sensations associated with the movement were emphasised Control: physical practice as above followed by listening to a 30 minute tape taking the participants through a progressive relaxation program (comparable length as the MP tape above) | |

| Outcomes | Fugl‐Meyer upper extremity Action Research Arm Test | |

| Notes | PEDro score 9/10 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomisation with a computer‐generated random number table that gave each participant equal probability of being assigned to the experimental or control intervention |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Selective reporting not evident |

| Blinding? patients | High risk | There are no statements regarding blinding of participants |

| Blinding? providers | Low risk | Therapists were blinded to participants' group assignment |

| Blinding? outcome assessors | Low risk | Examiners were blinded to participants' group assignment |

| Similarity of baseline characteristics? | Low risk | Experimental and control groups were similar in terms of age, time post stroke, Fugl‐Meyer and Action Research Arm test scores |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? ‐ dropouts | Low risk | There were no dropouts |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? ITT | Low risk | All participants were analysed in the group to which they were randomised |

Page 2009

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial with random numbers table Setting: quiet treatment room adjacent to therapy gym | |

| Participants | 5 in experimental group, 5 in control group; mean 28.5 months post stroke; mean age 61.4 (3.02) years; 70% male; stroke severity ‐ Fugl Meyer upper extremity experimental 38.4 (0.83), control 39.8 (1.3); hand dominance not described, affected extremity ‐ right 7, left 3; concordance not described | |

| Interventions | 30 minutes, 3 times/week for 10 weeks (30 sessions) MP dosage (total number of minutes of MP over the study) = 900 minutes Intervention: modified CIMT regimen (see below) augmented with MP regimen from Page 2007 (audiotape with middle 20 minutes having suggestions for internal, cognitive polysensory images to cue the participant to mentally rehearse the motor skill practiced earlier in the day. Of note, the images were in the first person perspective, and the sensations associated with the movement were emphasised) Control: modified CIMT regimen (30 minutes/day, 3 days/week for 10 weeks of practice of ADL; restraint of the less involved hand with mitt for 5 hours/day, 5 days/week for the same 10 weeks) | |

| Outcomes | Fugl Meyer upper extremity Action Research Arm Test | |

| Notes | PEDro score 7/10 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Patients were randomly assigned to experimental and control groups by a random numbers table |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Selective reporting not evident |

| Blinding? patients | High risk | No statements regarding strategies to blind the patients were found |

| Blinding? providers | High risk | No statements regarding strategies to blind therapists were found |

| Blinding? outcome assessors | Low risk | Examiner was blinded to group assignments |

| Similarity of baseline characteristics? | Low risk | Experimental and control groups were comparable at baseline in terms of Fugl‐Meyer and Action Research Arm tests |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? ‐ dropouts | Low risk | There were no dropouts |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? ITT | Low risk | All participants were analysed in the group to which they were randomised |

Riccio 2010

| Methods | Randomised cross‐over trial with computer‐generated random number Setting: inpatient rehabilitation unit | |

| Participants | 18 in experimental group, 18 in control group; mean 7.33 (2.38) weeks post stroke for control, 7.44 (2.41) weeks post stroke for intervention; mean age 60.17 (11.69) years in control, 60.06 (11.68) years in intervention; stroke severity Motricity Index (upper extremity) 56.22 (10.81) in control, 56.72 (11.14) in intervention; hand dominance affected extremity and concordance not specified | |

| Interventions | 60 minutes (twice a day), 5 days/week for 3 weeks MP dosage (total number of minutes of MP over the study) = 900 minutes Intervention: alone in a quiet room, performed by listening to an audio CD asking participant to imagine "in detail" simple activities involving the upper extremity; activities were taken from the Arm Function Test and conventional activities Cross‐over trial: after 3 weeks, groups switched Control: neurorehabilitation of therapeutic exercise and OT for 3 weeks, 3 hours/day, 5 days/week | |

| Outcomes | Motricity Index (upper extremity) Arm Functional Test: time Arm Functional Test: Functional Ability Scale | |

| Notes | PEDro score 7/10 Cross‐over study: only used first treatment in each group: group A = control, and group B = intervention Little information provided about the Arm Functional Test | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Participants were randomly allocated to groups using a computer‐generated random number table |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Selective reporting not evident |

| Blinding? patients | High risk | There are no comments regarding strategies used to blind patients |

| Blinding? providers | High risk | There are no comments regarding strategies used to blind therapists |

| Blinding? outcome assessors | Low risk | All assessments were performed by a rater blind to participants’ group assignment |

| Similarity of baseline characteristics? | Low risk | There were no significant differences between group for age, time post‐stroke, Motricity Index, or Arm Functional Test scores at baseline |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? ‐ dropouts | Low risk | There were no dropouts |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? ITT | Low risk | All participants were analysed in the group to which they were randomised |

ADL: activities of daily living CIMT: constraint‐induced movement therapy MP: mental practice OT: occupational therapy PT: physical therapy

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Bovend'Eerdt 2010 | No way to tease out the mental imagery that was specific to the upper extremity. There were also multiple diagnoses in addition to stroke |

| Hemmen 2007 | Intervention was not imagining motor skills or activities; it only imagined 1 isolated muscle movement |

| Liu 2004 | Intervention was not specific to the upper extremity |

| Miltner 1999 | Article in German; when translated it was not a RCT |

RCT: randomised controlled trials

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

Braun 2007

| Trial name or title | Effects of mental practice embedded in daily therapy compared to therapy as usual in adult stroke patients in Dutch nursing homes: design of a randomised controlled study (MIND) |

| Methods | Randomised, controlled, observer masked prospective trial |

| Participants | 70 individuals with stroke living in nursing homes, > 60 years old with cognition and communication that enables them to participate, between 2 and 10 weeks post stroke |

| Interventions | Intervention: usual therapy with mental practice techniques embedded in the therapy sessions (4 phases), focusing on the activities of drinking from a cup and walking Control: multi‐professional rehabilitation (usual therapy) 6 weeks long |

| Outcomes | Baseline, end of intervention (6 weeks), and at 6 months Primary outcome: 11‐point Likert scale on the performance of drinking from a cup and walking, rated by individual and therapist (10 = excellent, 0 = poor) Secondary outcomes: Impairment ‐ Motricity Index; Activity ‐ Barthel Index, Nine‐hole peg test, Rivermead Mobility Index, 10 metre walking test, Timed Up and Go Optional: QEEG ‐ brain activity |

| Starting date | Mid‐2007 to mid‐2009 |

| Contact information | Susy M Braun s.braun@hszuyd.nl |

| Notes |

Butler 2008

| Trial name or title | Mental imagery to reduce motor deficits in stroke |

| Methods | Randomised cross‐over trial with blinded outcome assessor |

| Participants | 20 individuals 3 to 12 months post stroke |

| Interventions | Intervention: mental imagery and constraint‐induced therapy Control: mental imagery only |

| Outcomes | Primary: Wolf Motor Function test, Fugl‐Meyer Motor Assessment, Movement Imagery Questionnaire, Vividness of Movement Imagery Questionnaire, Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, Stroke Impact Scale Secondary: Sirigu's Break Test |

| Starting date | January 2003 to July 2008 |

| Contact information | Andrew J Butler, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, USA |

| Notes | clinicaltrials.gov NCT00379392 |

Ietswaart 2006

| Trial name or title | Recovery of hand function through mental practice: a study protocol |

| Methods | Multicentre randomised controlled trial, 3 arms, blinded examiner |

| Participants | 135 individuals between 1 and 6 months post stroke (45 to each group) |

| Interventions | Intervention: training in motor imagery for upper extremity, 4 weeks, 45 minutes per day Control group 1: training in visual imagery (attention‐placebo), 4 weeks, 45 minutes per day Control group 2: normal care |

| Outcomes | Baseline and 5 weeks Primary outcome: Action Research Arm test Secondary outcomes: grip strength, Nine‐hole peg test, a new peg board timed task, Barthel Index, and Functional Limitation Profile, various measures to evaluate motor imagery ability, Recovery Locus of Control |

| Starting date | |

| Contact information | Magdalena Ietswaart, email: magdalena.ietswaart@northumbria.ac.uk |

| Notes |

Johnston 2006

| Trial name or title | Can motor recovery imagery enhance recovery of hand function after stroke? |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial, double blind |

| Participants | 135 individuals with stroke in 3 groups, 45 to each group |

| Interventions | Intervention: daily mental rehearsal of activities with affected hand with close supervision Control: closely supervised non‐motor mental rehearsal Control: no training program |

| Outcomes | Baseline and 4 weeks Primary: Action Research Arm test Secondary: grip strength, Nine‐hole pegboard task, Functional Limitation profile, Barthel Index, Recovery Locus of Control |