Abstract

Background

Ultrasound and liver function tests (serum bilirubin and serum alkaline phosphatase) are used as screening tests for the diagnosis of common bile duct stones in people suspected of having common bile duct stones. There has been no systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound and liver function tests.

Objectives

To determine and compare the accuracy of ultrasound versus liver function tests for the diagnosis of common bile duct stones.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, Science Citation Index Expanded, BIOSIS, and Clinicaltrials.gov to September 2012. We searched the references of included studies to identify further studies and systematic reviews identified from various databases (Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Health Technology Assessment, Medion, and ARIF (Aggressive Research Intelligence Facility)). We did not restrict studies based on language or publication status, or whether data were collected prospectively or retrospectively.

Selection criteria

We included studies that provided the number of true positives, false positives, false negatives, and true negatives for ultrasound, serum bilirubin, or serum alkaline phosphatase. We only accepted studies that confirmed the presence of common bile duct stones by extraction of the stones (irrespective of whether this was done by surgical or endoscopic methods) for a positive test result, and absence of common bile duct stones by surgical or endoscopic negative exploration of the common bile duct, or symptom‐free follow‐up for at least six months for a negative test result as the reference standard in people suspected of having common bile duct stones. We included participants with or without prior diagnosis of cholelithiasis; with or without symptoms and complications of common bile duct stones, with or without prior treatment for common bile duct stones; and before or after cholecystectomy. At least two authors screened abstracts and selected studies for inclusion independently.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently collected data from each study. Where meta‐analysis was possible, we used the bivariate model to summarise sensitivity and specificity.

Main results

Five studies including 523 participants reported the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound. One studies (262 participants) compared the accuracy of ultrasound, serum bilirubin and serum alkaline phosphatase in the same participants. All the studies included people with symptoms. One study included only participants without previous cholecystectomy but this information was not available from the remaining studies. All the studies were of poor methodological quality. The sensitivities for ultrasound ranged from 0.32 to 1.00, and the specificities ranged from 0.77 to 0.97. The summary sensitivity was 0.73 (95% CI 0.44 to 0.90) and the specificity was 0.91 (95% CI 0.84 to 0.95). At the median pre‐test probability of common bile duct stones of 0.408, the post‐test probability (95% CI) associated with positive ultrasound tests was 0.85 (95% CI 0.75 to 0.91), and negative ultrasound tests was 0.17 (95% CI 0.08 to 0.33).

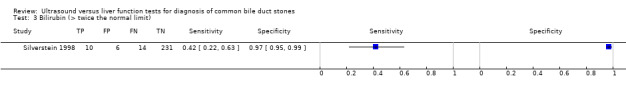

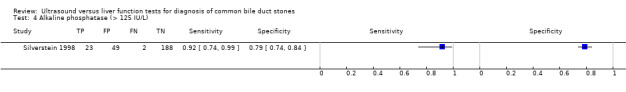

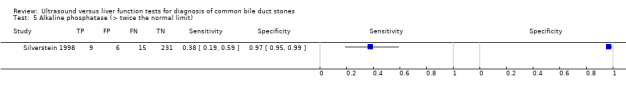

The single study of liver function tests reported diagnostic accuracy at two cut‐offs for bilirubin (greater than 22.23 μmol/L and greater than twice the normal limit) and two cut‐offs for alkaline phosphatase (greater than 125 IU/L and greater than twice the normal limit). This study also assessed ultrasound and reported higher sensitivities for bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase at both cut‐offs but the specificities of the markers were higher at only the greater than twice the normal limit cut‐off. The sensitivity for ultrasound was 0.32 (95% CI 0.15 to 0.54), bilirubin (cut‐off greater than 22.23 μmol/L) was 0.84 (95% CI 0.64 to 0.95), and alkaline phosphatase (cut‐off greater than 125 IU/L) was 0.92 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.99). The specificity for ultrasound was 0.95 (95% CI 0.91 to 0.97), bilirubin (cut‐off greater than 22.23 μmol/L) was 0.91 (95% CI 0.86 to 0.94), and alkaline phosphatase (cut‐off greater than 125 IU/L) was 0.79 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.84). No study reported the diagnostic accuracy of a combination of bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase, or combinations with ultrasound.

Authors' conclusions

Many people may have common bile duct stones in spite of having a negative ultrasound or liver function test. Such people may have to be re‐tested with other modalities if the clinical suspicion of common bile duct stones is very high because of their symptoms. False‐positive results are also possible and further non‐invasive testing is recommended to confirm common bile duct stones to avoid the risks of invasive testing.

It should be noted that these results were based on few studies of poor methodological quality and the results for ultrasound varied considerably between studies. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution. Further studies of high methodological quality are necessary to determine the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound and liver function tests.

Keywords: Humans, Liver Function Tests, Alkaline Phosphatase, Alkaline Phosphatase/blood, Bilirubin, Bilirubin/blood, Biomarkers, Biomarkers/blood, Choledocholithiasis, Choledocholithiasis/diagnosis, Choledocholithiasis/diagnostic imaging, Ultrasonography

Plain language summary

Ultrasound and liver function tests for the diagnosis of common bile duct stones

Background

Bile, produced in the liver and stored temporarily in the gallbladder, is released into the small bowel on eating fatty food. The common bile duct is the tube through which bile flows from the gallbladder to the small bowel. Stones in the common bile duct (common bile duct stones), usually formed in the gallbladder before migration into the bile duct, can obstruct the flow of bile leading to jaundice (yellowish discolouration of skin, white of the eyes, and dark urine); infection of the bile (cholangitis); and inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis), which can be life threatening. Various diagnostic tests can be performed for the diagnosis of common bile duct stones. Depending upon the availability of resources, these stones are removed endoscopically (usually the case) or may be removed as a part of the operation performed to remove the gallbladder (it is important to remove the gallbladder since the stones continue to form in the gallbladder and can cause recurrent problems). Non‐invasive tests such as ultrasound (use of sound waves higher than audible range to differentiate tissues based on how they reflect the sound waves) and blood markers of bile flow obstruction such as serum bilirubin and serum alkaline phosphatase are used to identify people at high risk of having common bile duct stones. Using non‐invasive tests means that only those people at high risk can be subjected to further tests. We reviewed the evidence on the accuracy of ultrasound and liver function tests for detection of common bile duct stones. The evidence is current to September 2012.

Study characteristics

We identified five studies including 523 participants that reported the diagnostic test accuracy of ultrasound. One of these studies, involving 262 participants, also reported the diagnostic test accuracy of serum bilirubin and serum alkaline phosphatase. All the studies included people with symptoms. One study included only participants who had not undergone previous cholecystectomy (removal of gallbladder). This information was not available from the remaining studies.

Key results

Based on an average sensitivity of 73% for ultrasound, we would expect that on average 73 out of 100 people with common bile duct stones will be detected while the remaining 27 people will be missed and will not receive appropriate treatment. The average number of people with common bile duct stones detected using ultrasound may vary between 44 and 90 out of 100 people. Based on an average specificity of 91% for ultrasound, we would expect that on average 91 out of 100 people without common bile duct stones would be identified as not having common bile duct stones; 9 out of 100 would be false positives and not receive appropriate treatment. The average number of false positives could vary between 5 and 16 out of 100 people.

Evidence from one study suggested that using a level of serum alkaline phosphatase higher than 125 units to distinguish between people who have and people who do not have common bile duct stones gave better diagnostic accuracy than using a level twice the normal limit (which usually ranges between 0 and 40). The study also showed better accuracy for serum alkaline phosphatase compared to serum bilirubin.

The sensitivity of serum alkaline phosphatase at the 125 units cut‐off was 92%, which means that 92 out of 100 people with common bile duct stones would be detected but 8 out of 100 people will be missed. The number detected could vary between 74 and 99 out of 100 people. Based on the specificity of 79%, 79 out of 100 people without common bile duct stones will be correctly identified as not having common bile duct stones while the remaining 21 people will be false positives. The number of false positives could vary between 16 and 26 out of 100 people. This suggests that further non‐invasive tests may be useful to diagnose common bile duct stones prior to the use of invasive tests.

Quality of evidence

All the studies were of low methodological quality, which may undermine the validity of our findings.

Future research

Further studies of high methodological quality are necessary.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings'. 'Performance of ultrasound and liver function tests for diagnosis of common bile stones.

| Population | People suspected of having common bile duct stones. | ||||

| Settings | Secondary and tertiary care setting in different parts of the world. | ||||

| Index tests | Ultrasound and liver function tests (bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase). For bilirubin, the cut‐offs used to define test positivity were > 22.23 μmol/L and > twice the normal limit. For alkaline phosphatase, the cut‐offs were > 125 IU/L and > twice the normal limit. | ||||

| Reference standard | Endoscopic or surgical extraction of stones in people with a positive index test result or clinical follow‐up (minimum 6 months) in people with a negative index test result. | ||||

| Target condition | Common bile duct stones. | ||||

| Number of studies | 5 studies (162 cases, 523 participants) evaluated ultrasound. 1 of these studies (25 cases, 262 participants) also evaluated bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase. | ||||

| Methodological quality concerns | All the studies were of poor methodological quality; most studies were at high risk of bias or gave high concern about applicability across all domains of quality assessment, or both. | ||||

| Test (cut‐off) | Summary sensitivity (95% CI)1 | Summary specificity (95% CI)1 | Pre‐test probability2 | Positive post‐test probability (95% CI)3 | Negative post‐test probability (95% CI)4 |

| Ultrasound | 0.73 (0.44 to 0.90) | 0.91 (0.84 to 0.95) | 0.095 | 0.45 (0.31 to 0.60) | 0.03 (0.01 to 0.07) |

| 0.408 | 0.85 (0.75 to 0.91) | 0.17 (0.08 to 0.33) | |||

| 0.658 | 0.94 (0.89 to 0.97) | 0.37 (0.20 to 0.58) | |||

| Bilirubin (> 22.23 μmol/L) | 0.84 (0.64 to 0.94) | 0.91 (0.86 to 0.94) | 0.095 | 0.49 (0.38 to 0.59) | 0.02 (0.01 to 0.04) |

| Bilirubin (> twice the normal limit) | 0.42 (0.22 to 0.63) | 0.97 (0.95 to 0.99) | 0.095 | 0.63 (0.41 to 0.81) | 0.06 (0.04 to 0.08) |

| Alkaline phosphatase (> 125 IU/L) | 0.92 (0.74 to 0.99) | 0.79 (0.74 to 0.84) | 0.095 | 0.32 (0.26 to 0.38) | 0.01 (0.00 to 0.04) |

| Alkaline phosphatase (> twice the normal limit) | 0.38 (0.19 to 0.59) | 0.97 (0.95 to 0.99) | 0.095 | 0.61 (0.38 to 0.80) | 0.06 (0.05 to 0.08) |

|

Interpretation of results: For ultrasound, at a pre‐test probability of 9.5%, out of 100 people with a positive result, common bile duct stones would be present in 45 people, at a pre‐test probability of 40.8%, they would be present in 85 people, and at a pre‐test probability of 65.8%, they would be present in 94 people. For ultrasound, at a pre‐test probability of 9.5%, out of 100 people with a negative result, common bile duct stones would be present in 3 people, at a pre‐test probability of 40.8%, they would be present in 17 people, and at a pre‐test probability of 65.8%, they would be present in 37 people. For bilirubin, at a pre‐test probability of 9.5%, out of 100 people with a positive result at a cut‐off above 22.23 μmol/L, common bile duct stones would be present in 49 people, and out of 100 people with a negative result, common bile duct stones would be present in 2 people. For alkaline phosphatase, at a pre‐test probability of 9.5%, out of 100 people with a positive result a cut‐off above 125 IU/L, common bile duct stones would be present in 32 people, and out of 100 people with a negative result, common bile duct stones would be present in 2 people. | |||||

| Comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound and liver function tests: because only 1 study reported the diagnostic accuracy of liver function tests, it was not possible to compare test accuracy in a meta‐analysis. The study compared ultrasound, bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase and reported higher sensitivities for bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase than ultrasound at both cut‐offs but the specificities of the markers were higher at only the cut‐off that was twice the normal limit. | |||||

| Conclusions: a negative ultrasound or liver function result may lead to many people with common bile duct stones being missed and further testing is needed in people with a high suspicion of the condition. However, the strength of evidence on the accuracy of the tests was very weak because it was based on few and methodologically flawed studies. | |||||

1Summary sensitivity and specificity for ultrasound only. Only 1 study evaluated bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase, so there are no pooled estimates.

2The pre‐test probability (proportion with common bile duct stones out of the total number of participants) was computed for each included study. For ultrasound, these numbers represented the minimum, median, and maximum values from the 5 studies. For bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase, the minimum pre‐test probability was also the pre‐test probability in the 1 study that evaluated the tests.

3Post‐test probability of common bile duct stones in people with positive index test results.

4Post‐test probability of common bile duct stones in people with negative index test results.

Background

Biliary stones are conglomerates of precipitated bile salts that form in the gallbladder or the common bile duct. The common bile duct carries bile from the liver to the duodenum (first part of the small intestine). The term 'gallstones' generally refer to the stones in the gallbladder while 'common bile duct stones' refer to stones in the common bile duct. Common bile duct stones may form inside the common bile duct (primary common bile duct stones), or they may form in the gallbladder and migrate to the common bile duct (secondary common bile duct stones) (Williams 2008). A significant proportion of people presenting with common bile duct stones may be asymptomatic (Sarli 2000). In some people, the stones pass silently into the duodenum, and in other people, the stones cause clinical symptoms such as biliary colic, jaundice, cholangitis, or pancreatitis (Caddy 2006). The prevalence of gallstone disease in the general population is about 6% to 15% with a higher prevalence in females (Barbara 1987; Loria 1994). Only 2% to 4% of people with gallstones become symptomatic with biliary colic (pain), acute cholecystitis (inflammation), obstructive jaundice, or gallstone pancreatitis in one year (Attili 1995; Halldestam 2004), and removal of gallbladder is recommended in people with symptomatic gallstones (Gurusamy 2010). Among people who undergo laparoscopic cholecystectomy (removal of gallbladder) for symptomatic gallstones, 3% to 22% also have concomitant common bile duct stones (Arnold 1970; Lill 2010; Yousefpour Azary 2011).

Common bile duct stones present in multiple ways. Central and right‐sided upper abdominal pain is a common presentation (Anciaux 1986; Roston 1997). Jaundice, caused by an impacted stone in the common bile duct leading to obstruction of bile passage into the duodenum, is another presentation. It may subsequently resolve if the common bile duct stone passes spontaneously into the duodenum. This happens in 54% to 73% of people with common bile duct stones in whom cholecystectomy is performed for gallstones (Tranter 2003; Lefemine 2011). Another, more dangerous, complication of common bile duct stones is acute cholangitis. Cholangitis is clinically defined by Charcot's triad, which includes elevated body temperature, pain under the right ribcage, and jaundice (Raraty 1998; Salek 2009). Acute cholangitis is caused by an ascending bacterial infection of the common bile duct and the biliary tree along with biliary obstruction. This complication is present in 2% to 9% of people admitted for gallstone disease (Saik 1975; Tranter 2003), and a mortality of approximately 24% is recorded (Salek 2009). Common bile duct stones may also cause acute pancreatitis, accounting for 33% to 50% of all people with acute pancreatitis (Corfield 1985; Toh 2000). Acute pancreatitis is usually a self limiting disease and is usually sufficiently treated by conservative measures in its mild form (Neoptolemos 1988). However, a more severe pancreatitis may evolve in approximately 27% to 37% of people with common bile duct stone‐induced pancreatitis, with mortality around 6% to 9% (Mann 1994; Toh 2000).

Suspicion of common bile duct stones can be confirmed by laboratory liver function tests (Barkun 1994), or imaging tests such as abdominal ultrasound (Ripolles 2009). Further testing may include endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) (Aljebreen 2008), magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) (Stiris 2000), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) (Geron 1999), and intraoperative cholangiography (IOC) (Fiore 1997). Currently, these are the recommended tests for diagnosis of common bile duct stones and of these tests, IOC can only be done during an operation as the test requires surgical cannulation of the common bile duct during cholecystectomy. The other tests may be used preoperatively or postoperatively. Usually the first diagnostic tests that most people will undergo are liver function tests and abdominal ultrasound. While ultrasound findings about common bile duct stones are available as a part of the test that the person undergoes for the diagnosis of gallstones, liver function tests may be routinely used to screen people with gallstones to identify people who need further testing. Invasive diagnostic tests are usually reserved for people with suspected common bile duct stones based on non‐invasive diagnostic tests, or when therapeutic measures are necessary (Freitas 2006).

There are other tests such as conventional computed tomogram, computed tomogram cholangiogram, laparoscopic ultrasound, and ERCP‐guided intraductal ultrasound used for diagnosing common bile duct stones, but these are of limited use (Maple 2010).

Target condition being diagnosed

Common bile duct stones. We did not differentiate the target condition with respect to common bile duct stone size, degree of common bile duct obstruction, and the presence or absence of symptoms.

Index test(s)

Liver function tests measure different biochemical reactions in blood drawn from the person. Common bile duct stones are usually suspected in the presence of elevated gamma glutamyltransferase, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and bilirubin levels. Liver function tests are usually the first laboratory tests that a person, whether asymptomatic or symptomatic, would undergo (along with abdominal ultrasound). Elevated bilirubin, gamma glutamyltransferase, or ALP raises suspicion of an obstruction of the common bile duct with a stone, tumour, or inflammatory changes (Barkun 1994; Giannini 2005). The normal values of these tests vary in different laboratories and are generally considered as the mean and 95% confidence interval (CI) in a normal reference population (Giannini 2005). A bilirubin value more than 1 mg/dL (greater than 17.1 μmol/L) is generally considered abnormal (FDA 2013). The mean ALP value in an adult population is between 50 and 170 IU/L (Eastman 1977). Gamma glutamyltransferase can be elevated because of alcohol abuse and drugs such as phenytoin and barbiturates (Rosalki 1971; Giannini 2005), and hence is of limited value in the diagnosis of obstruction to the flow of bile. Transaminases may also be elevated in the presence of obstructive jaundice due to common bile duct stones (Hayat 2005), but they may also be elevated in liver parenchymal damage. We fully acknowledge that even bilirubin and ALP can be elevated because of other reasons, but these are common tests used as triage tests for diagnosis of common bile stones particularly in people with gallstones. In this review, we assessed serum bilirubin and ALP as the index tests. We planned to investigate a test strategy that included abnormal values for either test or abnormal values for both tests.

Abdominal ultrasound uses sound waves of high frequency to visualise tissues and structures located in the abdomen, including the gallbladder and the common bile duct. The ultrasound probe is placed on the skin of the abdomen, using gel to enhance visibility. A test is considered positive when a hyperechoic round or oval structure is seen within the common bile duct (Ripolles 2009; RadiologyInfo 2011).

Clinical pathway

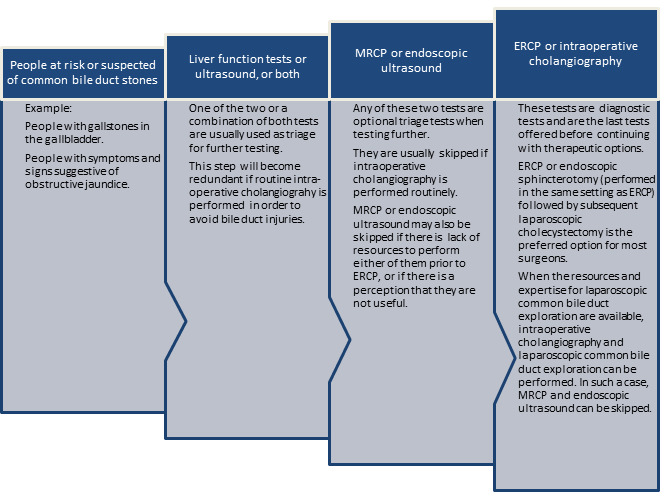

Figure 1 shows a diagnostic pathway. People that are at risk of having common bile duct stones or suspected of having common bile duct stones (such as people with gallbladder stones or people that show symptoms and signs of obstructive jaundice or pancreatitis) will undergo liver function tests and abdominal ultrasound as the first step. An abdominal ultrasound is usually available by the time the person is at risk or suspected of having common bile duct stones. Usually a combination of both tests is used as triage tests before further testing is done in the second step, but these can be used as the definitive diagnostic test to carry out a therapeutic option directly (e.g., endoscopic or surgical common bile duct exploration) (Williams 2008; ASGE Standards of Practice Committee 2010). MRCP or EUS are tests in the second step of the diagnostic pathway and are used as optional triage tests prior to the tests used in the third step of the diagnostic pathway, but can also be used as definitive diagnostic tests to carry out a therapeutic option directly. MRCP and EUS are not usually combined, since the positive or negative results of one or the other is usually accepted for further clinical decision making, without taking into consideration the results of liver function tests or transabdominal ultrasound, as it is generally believed that MRCP and EUS have better diagnostic accuracy than liver function tests or transabdominal ultrasound. ERCP and IOC are used in the third step of the diagnostic pathway. Both tests are done just before the therapeutic intervention. Therapeutic interventions, such as endoscopic or surgical stone extraction, can then be undertaken during the same session. ERCP is done before endoscopic sphincterotomy and removal of common bile duct stones using Dormia basket or balloon during the same endoscopic session (Prat 1996; Maple 2010), and IOC is done before surgical common bile duct exploration and removal of common bile duct stones using surgical instruments during operation for cholecystectomy (Targarona 2004; Freitas 2006; Chen 2007; Williams 2008; ASGE Standards of Practice Committee 2010; Kelly 2010).

1.

Diagnostic pathway for diagnosis of common bile duct stones. Note that ultrasound is generally performed in all people at risk or suspected of common bile duct stones.

ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; MRCP: magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography.

Ultrasound and liver function tests are considered as triage tests before the person undergoes further investigation using MRCP, EUS, ERCP, or IOC and are generally performed in all people in whom common bile duct stones are suspected.

Implications of negative test results

In general, people with negative test results in one step do not undergo further testing. For example, a person with no suggestion of common bile duct stones on liver function tests and ultrasound will not undergo further testing for common bile duct stones. Similarly, people with no suggestion of common bile duct stones on MRCP or EUS will not undergo further testing for common bile duct stones and people with no suggestion of common bile duct stones on ERCP or IOC will not undergo common bile duct clearance. People with a false‐negative test result can develop life‐threatening complications of common bile duct stones, such as cholangitis and pancreatitis, but the natural history of such people in terms of the frequency with which these complications develop is unknown. However, it is generally recommended that common bile duct stones are removed when they are identified because of the serious complications that can occur (Williams 2008). Although this practice is not evidence‐based, this shows the perception among hepato‐pancreato biliary surgeons and gastroenterologists that it is important not to miss common bile duct stones.

Rationale

There are several benign (non‐cancerous) and malignant (cancerous) conditions that may cause obstructive jaundice. Benign causes of obstructive jaundice include primary sclerosing cholangitis (Penz‐Osterreicher 2011), primary biliary cirrhosis (Hirschfield 2011), chronic pancreatitis (Abdallah 2007), autoimmune pancreatitis (Lin 2008), inflammatory strictures of the common bile duct (Krishna 2008), and strictures of the common bile duct caused by prior instrumentation (Lillemoe 2000; Tang 2011). Malignant causes of obstructive jaundice include cholangiocarcinoma (Siddiqui 2011), cancer of the ampulla of Vater as well as other periampullary cancers (Hamade 2005; Choi 2011; Park 2011), and carcinoma of the pancreas (Singh 1990; Kalady 2004). It is important to differentiate between the causes of obstructive jaundice in order to initiate appropriate treatment. The correct diagnosis of common bile duct stones is an essential contribution to this differentiation.

Common bile duct stones are responsible for a range of complications. Common bile duct stones may lead to pancreatitis in about 33% to 50% of people (Corfield 1985; Toh 2000), and cause mortality in about 6% to 9% of these people (Mann 1994; Toh 2000). Acute cholangitis appears in 2% to 9% of people admitted for gallstone disease, with mortality around 24% (Salek 2009). Therefore, it is important to diagnose common bile duct stones in order to initiate treatment and prevent such complications.

The preferred option for the treatment of people with gallstones and common bile duct stones is currently endoscopic sphincterotomy with balloon trawling followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy (Ludwig 2001; Spelsberg 2009). Other options include open cholecystectomy with open common bile duct exploration, laparoscopic cholecystectomy with laparoscopic common bile duct exploration, and laparoscopic cholecystectomy with endoscopic sphincterotomy (Hong 2006; Dasari 2013). Approximately half of people with jaundice, abnormal liver function tests, and common bile duct dilation on ultrasound do not actually have common bile duct stones at ERCP (Hoyuela 1999), and these people have therefore undergone an unnecessary invasive procedure. Accurate diagnosis of common bile duct stones may avoid unnecessary procedures and complications associated with these procedures. Invasive tests can result in complications, for example, ERCP with endoscopic sphincterotomy can have life‐threatening complications such as pancreatitis (Gurusamy 2011). Accurate diagnosis of common bile duct stones using non‐invasive tests can avoid these complications.

Currently, there are no Cochrane reviews of studies assessing the accuracy of different tests for diagnosing common bile duct stones. This review is one of three reviews evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of different tests in the diagnosis of common bile duct stones and will help in the development of an evidence‐based algorithm for diagnosis of common bile duct stones.

Ultrasound and liver function tests are non‐invasive and almost used universally in the diagnosis of common bile duct stones, these tests are used for triage to determine whether people suspected of common bile duct stones undergo further tests. In this respect, it is important to know the false‐negative rate as such people will be at risk of developing complications due to common bile duct stones. If the false‐negative rate is high, then people may have to undergo other tests regardless of the results of ultrasound and liver function tests and so these tests fail in their role as triage tests. While false‐positive results from liver function tests and ultrasound are not very significant in a clinical pathway where further tests such as MRCP or EUS are performed prior to ERCP followed immediately by endoscopic sphincterotomy or surgical exploration of common bile duct, the false‐positive rate becomes very important in a clinical pathway where ERCP or surgical exploration is attempted directly after ultrasound or liver function tests as people are exposed to the risk of complications associated with these invasive procedures.

Objectives

To determine and compare the accuracy of ultrasound versus liver function tests for the diagnosis of common bile duct stones.

Secondary objectives

To investigate variation in the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound and liver function tests according to the following potential sources of heterogeneity.

Studies at low risk of bias versus studies with unclear or high risk of bias (as assessed by the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies assessment tool (QUADAS‐2) tool (Table 2)).

Full‐text publications versus abstracts (this may indicate publication bias if there is an association between the results of the study and the study reaching full publication) (Eloubeidi 2001).

Prospective versus retrospective studies.

Symptomatic versus asymptomatic common bile duct stones (the presence of symptoms may increase the pre‐test probability). People with symptoms were defined as people showing upper right quadrant abdominal pain, jaundice, acute cholangitis, or acute pancreatitis (Anciaux 1986; Roston 1997; Raraty 1998; Toh 2000; Tranter 2003).

Prevalence of common bile duct stones in each included study. The prevalence of common bile duct stones in the population analysed by each included study may vary and cause heterogeneity. Prevalence may also change with people with co‐morbidities that would predispose them to common bile duct stones such as primary sclerosing cholangitis, Caroli's disease, hypercholesterolaemia, sickle cell anaemia, and sphincter of Oddi dysfunction.

Proportion of people with previous cholecystectomy. Cholecystectomy may cause dilation of the common bile duct (Benjaminov 2013), and subsequently change the accuracy of the index test particularly imaging modalities.

1. Application of the QUADAS‐2 tool for assessing methodological quality of included studies.

| Domain | Signalling question | Signalling question | Signalling question | Risk of bias | Concerns for applicability |

| Domain 1: Participant sampling | |||||

| Participant sampling | Was a consecutive or random sample of participants enrolled? | Was a case‐control design avoided? | Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | Could the selection of participants have introduced bias? | Are there concerns that the included participants and setting did not match the review question? |

| Yes: all consecutive participants or random sample of participants with suspected common bile duct stones were enrolled. No: selected participants were enrolled. Unclear: this was not clear from the report. |

Yes: case‐control design was avoided. No: case‐control design was not avoided. Unclear: this was not clear from the report. |

Yes: the study avoided inappropriate exclusions (i.e., people who were difficult to diagnose). No: the study excluded participants inappropriately. Unclear: this was not clear from the report. |

Low risk: 'yes' for all signalling questions. High risk: 'no' or 'unclear' for at least 1 signalling question. |

Low concern: the selected participants represented the people in whom the tests would be used in clinical practice (see diagnostic pathway (Figure 1). High concern: there was high concern that participant selection was performed in a such a way that the included participants did not represent the people in whom the tests would be used in clinical practice. |

|

| Domain 2: Index test | |||||

| Index test(s) | Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | If a threshold was used, was it pre‐specified? | ‐ | Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias? | Were there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differed from the review question? |

| Yes: index test results were interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard. No: index test results were interpreted with knowledge of the results of the reference standard. Unclear: this was not clear from the report. |

Yes: if the criteria for a positive test result were pre‐specified. No: if the criteria for a positive test result were not pre‐specified. Unclear: this was not clear from the report. |

‐ | Low risk: 'yes' for all signalling questions. High risk: 'no' or 'unclear' for at least 1 of the 2 signalling questions. |

High concern: there was high concern that the conduct or interpretation of the index test differed from the way it was likely to be used in clinical practice. Low concern: there was low concern that the conduct or interpretation of the index test differed from the way it was likely to be used in clinical practice. |

|

| Domain 3: Reference standard | |||||

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Was the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? | Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index tests? | ‐ | Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias? | Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard did not match the review question? |

| Yes: all participants underwent the acceptable reference standard. No: if all participants did not undergo an acceptable reference standard. Such studies were excluded from the review. Unclear: if the reference standard that the participants underwent was not stated. Such studies were excluded from the review. |

Yes: reference standard results were interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test. No: reference standard results were interpreted with the knowledge of the results of the index test. Unclear: this was not clear from the report. |

‐ | Low risk: 'yes' for all signalling questions. High risk: 'no' or 'unclear' for at least 1 of the 2 signalling questions. |

Low concern: participants underwent endoscopic or surgical exploration for common bile duct stone. High concern: no participants underwent endoscopic or surgical exploration for common bile duct stone. |

|

| Domain 4: Flow and timing | |||||

| Flow and timing | Was there an appropriate interval between index test and reference standard? | Did all participants receive the same reference standard? | Were all participants included in the analysis? | Could the participant flow have introduced bias? | ‐ |

| Yes: the interval between index test and reference standard was shorter ≤ 4 weeks (arbitrary choice). No: the interval between index test and reference standard was > 4 weeks. Unclear: this was not clear from the report. |

Yes: all participants underwent endoscopic or surgical exploration for common bile duct stone irrespective of the index test results. No: participants underwent endoscopic or surgical exploration if the index test results were positive and underwent clinical follow‐up for at least 6 months if the index test results were negative. Unclear: this was not clear from the report. Such studies were excluded. |

Yes: all participants meeting the selection criteria (selected participants) were included in the analysis, or data on all the selected participants were available so that a 2 x 2 table including all selected participants could be constructed. No: not all participants meeting the selection criteria were included in the analysis or the 2 x 2 table could not be constructed using data on all selected participants. Unclear: this was not clear from the report. |

Low risk: 'yes' for all signalling questions. High risk: 'no' or 'unclear' for at least 1 signalling question. |

‐ | |

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included studies providing cross‐sectional information comparing one or more of the index tests against a reference standard in the appropriate patient population (see Participants). We included studies irrespective of language or publication status, or whether data were collected prospectively or retrospectively. We included comparative studies in which ultrasound and liver function tests were performed in the same study population either by giving all participants the index tests or by randomly allocating participants to receive ultrasound or a liver function test. We excluded diagnostic case‐control studies if there were at least four cross‐sectional or comparative studies.

Participants

People at risk of or suspected of having common bile duct stones, with or without prior diagnosis of cholelithiasis; with or without symptoms and complications of common bile duct stones, with or without prior treatment for common bile duct stones; and before or after cholecystectomy.

Index tests

Ultrasound and liver function tests (serum bilirubin and ALP).

Target conditions

Common bile duct stones.

Reference standards

We accepted the following reference standards.

For test positives, we accepted confirmation of a common bile duct stone by extraction of the stone (irrespective of whether this is done by surgical or endoscopic methods).

For test negatives, we acknowledged that there was no way of being absolutely sure that there were no common bile duct stones. However, we accepted negative results by surgical or endoscopic negative exploration of the common bile duct, or symptom‐free follow‐up for at least six months, as the reference standard. Surgical or endoscopic exploration is adequate, but it is not commonly used in people with negative index tests because of its invasive nature. Therefore, we accepted follow‐up as a less adequate reference test. Negative exploration of common bile duct is likely to be a better reference standard than follow‐up for at least six months since most stones already present in the common bile duct are likely to be extracted using this method. Six months was an arbitrary choice, but we anticipated most common bile duct stones would manifest during this period.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched MEDLINE via PubMed (January 1946 to September 2012), EMBASE via OvidSP (January 1947 to September 2012), Science Citation Index Expanded via Web of Knowledge (January 1898 to September 2012), BIOSIS via Web of Knowledge (January 1969 to September 2012), and clinicaltrials.gov/ (September 2012). Appendix 1 shows the search strategies. We used a common search strategy for the three reviews of which this review is one. The other two reviews assessed the diagnostic accuracy of EUS, MRCP, ERCP, and IOC (Gurusamy 2015; Giljaca 2015). We also identified systematic reviews from the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Health Technology Assessment (HTA), Medion, and ARIF (Aggressive Research Intelligence Facility) databases in order to search their reference lists (see Searching other resources).

Searching other resources

We searched the references of included studies and systematic reviews related to the topic for identifying further studies. We also searched for additional articles related to included studies by performing the 'related search' function in MEDLINE (PubMed) and EMBASE (OvidSP), and a 'citing reference' search (search the articles that cited the included articles) (Sampson 2008) in Science Citation Index Expanded and EMBASE (OvidSP).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors (VG and DH or GP) searched the references independently for identification of relevant studies. We obtained full texts for the references that at least one of the authors considered relevant. Two authors (VG and DH or GP) independently assessed the full‐text articles. One author (KG) arbitrated any differences in study selection. We selected studies that met the inclusion criteria for data extraction. We included abstracts that provided sufficient data to create a 2 x 2 table.

Data extraction and management

Two authors (KG and VG) independently extracted the following data from each included study.

First author of report.

Year of publication of report.

Study design (prospective or retrospective; cross‐sectional studies or randomised clinical trials).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for individual studies.

Total number of participants.

Number of males and females.

Mean age of the participants.

Tests carried out prior to index test.

Index test.

Reference standard.

Number of true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives.

We sought further information on the diagnostic test accuracy data and assessment of methodological quality (see Assessment of methodological quality) from the authors of the studies, if necessary. We resolved any differences between the review authors by discussion until we reached a consensus. We extracted the data excluding the indeterminates but recorded the number of indeterminates and the reference standard results of the participants with indeterminate results.

Assessment of methodological quality

We adopted the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies assessment tool (QUADAS‐2) for assessment of the methodological quality of included studies as described in Table 2) (Whiting 2006; Whiting 2011). We considered studies classified at low risk of bias and low concern regarding applicability to the review question as studies at low risk of bias. We resolved any differences in the methodological quality assessment by discussion between the authors until we reached consensus. We sought further information from study authors in order to assess the methodological quality of included studies accurately.

Statistical analysis and data synthesis

We plotted study estimates of sensitivity and specificity on forest plots and in receiver operating characteristic (ROC) space to explore between‐study variation in the performance of the tests. Because our focus of inference was summary points, we used the bivariate model to summarise jointly the sensitivity and specificity if the number of studies was adequate for a meta‐analysis to be performed (Reitsma 2005; Chu 2006). This model accounts for between‐study variability in estimates of sensitivity and specificity through the inclusion of random effects for the logit sensitivity and logit specificity parameters of the bivariate model. We planned to calculate the summary sensitivity and specificity of serum bilirubin and serum ALP for each reported cut‐off if there were sufficient data to enable meta‐analyses. We performed meta‐analysis using the xtmelogit command in Stata version 13 (Stata‐Corp, College Station, Texas, USA). Confidence regions on summary ROC plots generated using Review Manager 5 are excessively conservative when there are few studies and they may appear inconsistent with the estimated CIs (RevMan 2012). While estimation of the CIs relies on the standard errors, the confidence regions rely on the number of studies in addition to the standard errors and the covariance of the estimated mean logit sensitivity and specificity. Therefore, if there were fewer than 10 studies included in a meta‐analysis, we used 10 as the number of studies for generating the regions. This number is arbitrary but seemed to provide a better approximation than using a small number of studies.

We planned to compare the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound, serum bilirubin, and serum ALP by including covariate terms for test type in the bivariate model to estimate differences in the sensitivity and specificity of the tests. In addition, if studies that evaluated ultrasound and liver function tests in the same study population had been available, we planned to perform a direct head‐to‐head comparison by limiting the test comparison to such studies.

We created a table of pre‐test probabilities (using the observed median and range of prevalence from the included studies) against post‐test probabilities. The post‐test probabilities were calculated using the pre‐test probabilities and the summary positive and negative likelihood ratios. We computed the summary likelihood ratios and their CIs by using the Stata _diparm command and functions of the parameter estimates from the bivariate model that we fitted to estimate the summary sensitivity and specificity of a test.

Investigations of heterogeneity

We visually inspected forest plots of sensitivity and specificity and summary ROC plots to identify heterogeneity. We investigated the sources of heterogeneity stated in the Secondary objectives. Where possible, given the number of included studies, we planned to explore heterogeneity formally by adding each potential source of heterogeneity as a covariate in the bivariate model (meta‐regression with one covariate at a time).

Sensitivity analyses

Exclusion of participants with uninterpretable results can result in overestimation of diagnostic test accuracy (Schuetz 2012). In practice, uninterpretable test results will generally be considered test negatives. Therefore, we planned to perform sensitivity analyses by including uninterpretable test results as test negatives if sufficient data were available.

Assessment of reporting bias

As described in the Investigations of heterogeneity section, we planned to investigate whether the summary sensitivities and specificities differed between studies that were published as full texts and studies that were available only as abstracts.

Results

Results of the search

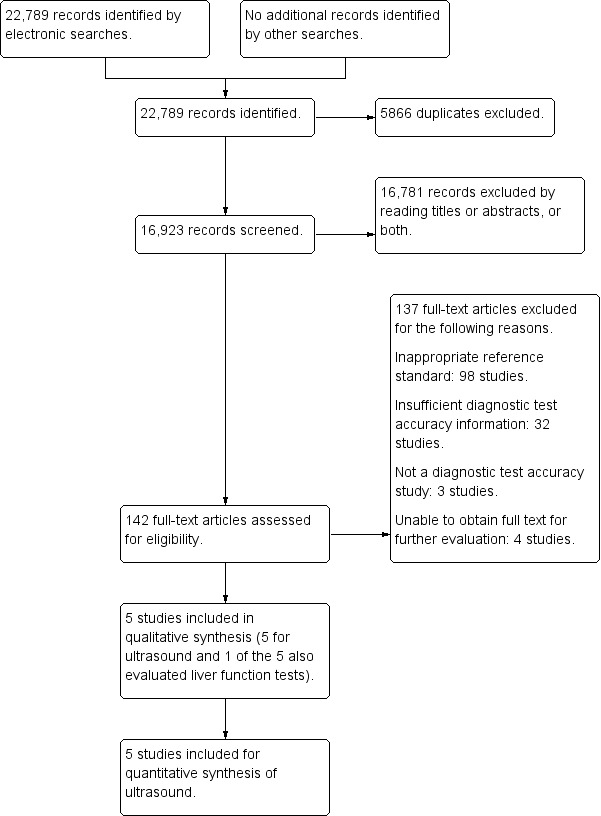

We identified 22,789 references through electronic searches of MEDLINE (8292 references), EMBASE (10,029 references), Science Citation Index Expanded and BIOSIS (4276 references), and DARE and HTA in The Cochrane Library (192 references). We identified no additional studies by searching the other sources. We excluded 5866 duplicates and 16,781 clearly irrelevant references through reading the abstracts. We retrieved 142 references for further assessment. We excluded 137 references for the reasons listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Five studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria and provided data for the review. We were able to obtain additional information from the authors of one of the studies (Kumar 1998). Figure 2 shows the flow of studies through the selection process.

2.

Flow of studies through the screening process.

Characteristics of included studies

We included five studies (Busel 1989; Kumar 1998; Silverstein 1998; Admassie 2005; Rickes 2006; see Characteristics of included studies table). The studies included 523 participants. All five studies reported the diagnostic test accuracy of abdominal ultrasound. One study including 262 participants reported the diagnostic accuracy of serum bilirubin and serum ALP (Silverstein 1998). The median pre‐test probability of common bile duct stones in the five studies was 0.408 (range 0.095 to 0.658).

The five included studies were full‐text publications. Three studies recruited participants prospectively (Kumar 1998; Silverstein 1998; Rickes 2006). Two studies included people with obstructive jaundice (Kumar 1998; Admassie 2005), two studies included people with jaundice or other symptoms such as pancreatitis (Silverstein 1998; Rickes 2006), and one study included people who underwent common bile duct exploration for common bile duct stones (Busel 1989). Thus, it appears that all the studies included people with symptoms. One study included only participants who had not undergone previous cholecystectomy (Silverstein 1998), but the information was not available in the remaining studies. The proportion of people with common bile duct strictures was 6% (Admassie 2005), and 12% (Kumar 1998), in the two studies that provided this information.

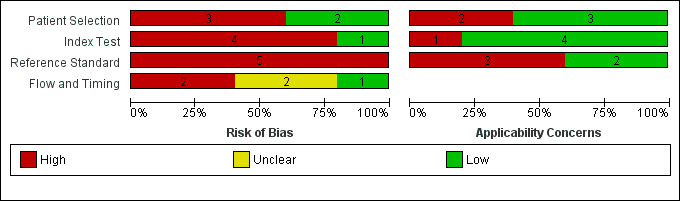

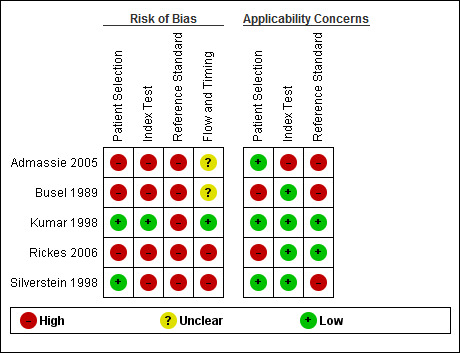

Methodological quality of included studies

Figure 3 and Figure 4 summarise the methodological quality of the included studies. All the studies were of poor methodological quality.

3.

Risk of bias and applicability concerns graph: review authors' judgements about each domain presented as percentages across included studies.

4.

Risk of bias and applicability concerns summary: review authors' judgements about each domain for each included study.

Patient selection

Two studies were at low risk of bias and of low concern regarding applicability in the 'patient selection' domain (Kumar 1998; Silverstein 1998). The remaining studies were at high risk of bias with high concern about applicability because they did not mention whether a consecutive or random sample of participants was included.

Index test

Only one study was at low risk of bias in the 'index test' domain (Kumar 1998). The remaining studies were at high risk of bias because it was not clear whether the index test results were interpreted without knowledge of the reference standard results. Four studies were of low concern about applicability (Busel 1989; Kumar 1998; Silverstein 1998; Rickes 2006), while one study was of high concern because the criteria for a positive diagnosis were not reported (Admassie 2005).

Reference standard

None of the studies were at low risk of bias in the 'reference standard' domain. The studies were at high risk of bias because it was either not clear whether the reference standards were interpreted without knowledge of the index test results (Busel 1989; Silverstein 1998; Admassie 2005; Rickes 2006), or it was clear that the reference standards were interpreted with knowledge of the index test results (Kumar 1998). Four studies were of low concern about applicability (Busel 1989; Kumar 1998; Admassie 2005; Rickes 2006), while one study was of high concern because endoscopic or surgical clearance of common bile duct was achieved in people with a positive test result and clinical follow‐up was performed in people with a negative test result (Silverstein 1998).

Flow and timing

Only one study was at low risk of bias in the 'flow and timing' domain (Kumar 1998). The remaining studies were at high risk of bias because of the following reasons. Four studies did not report the time interval between the index test and reference standard (Busel 1989; Silverstein 1998; Admassie 2005; Rickes 2006), and in one study, the same reference standard was not used since endoscopic or surgical clearance of common bile duct was achieved in people with a positive test result and clinical follow‐up was performed in people with a negative test result (Silverstein 1998). It was unclear whether all the participants were included in the analysis in two studies (Busel 1989; Admassie 2005), while two participants were excluded from the analysis in one study (Rickes 2006).

Findings

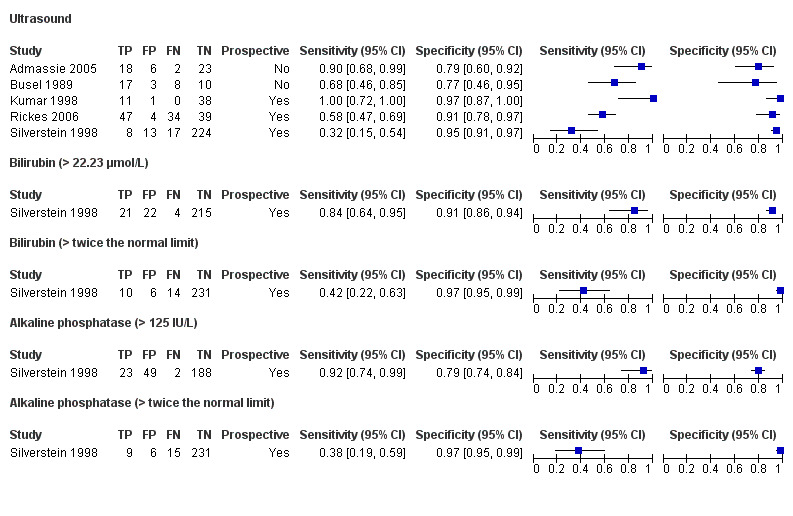

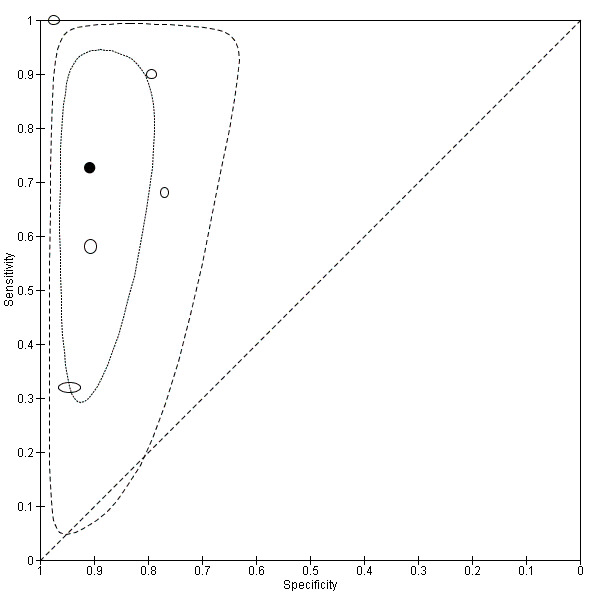

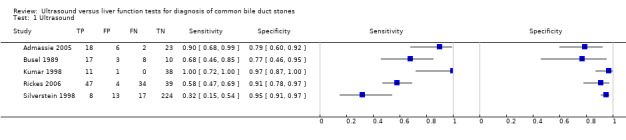

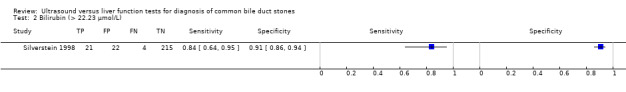

The forest plot of sensitivity and specificity (Figure 5) and the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) plot (Figure 6) summarises the individual study estimates of sensitivity and specificity (with 95% CIs) for ultrasound and the liver function tests. Results were available at two different cut‐offs for bilirubin (greater than 22.23 μmol/L and greater than twice the normal limit) and ALP (greater than 125 IU/L and greater than twice the normal limit). Based on the five included studies, the minimum pre‐test probability was 0.095, median was 0.408, and maximum was 0.658.

5.

Forest plot of ultrasound and liver function tests for detection of common bile duct stones. The plot shows study‐specific estimates of sensitivity and specificity (with 95% confidence intervals). The studies are ordered according to whether recruitment was prospective or not, and sensitivity. FN: false negative; FP: false positive; TN: true negative; TP: true positive.

6.

Summary receiver operating characteristic (ROC) plot of ultrasound for detection of common bile duct stones. Each ellipse on the plot represents the pair of sensitivity and specificity from a study and the size of the ellipse is scaled according to the sample size of the study. The solid black circle represents the summary sensitivity and specificity, and this summary point is surrounded by a 95% confidence region (dotted line) and 95% prediction region (dashed line).

Ultrasound

Five studies including 162 cases out 523 participants reported the diagnostic test accuracy of ultrasound. Sensitivities ranged from 0.32 to 1.00 and specificities ranged from 0.77 to 0.97. The summary sensitivity was 0.73 (95% CI 0.44 to 0.90) and specificity was 0.91 (95% CI 0.84 to 0.95). The positive likelihood ratio was 7.89 (95% CI 4.33 to 14.4) and the negative likelihood ratio was 0.30 (95% CI 0.13 to 0.72). At the median pre‐test probability of common bile duct stones of 0.408, post‐test probability associated with positive test results was 0.85 (95% CI 0.75 to 0.91) and negative test results was 0.17 (95% CI 0.08 to 0.33). At the minimum pre‐test probability of 0.095, the post‐test probability associated with positive test results was 0.45 (95% CI 0.31 to 0.60) and negative test results was 0.03 (95% CI 0.01 to 0.07). At the maximum pre‐test probability of 0.658, the post‐test probability associated with positive test results was 0.94 (95% CI 0.89 to 0.97) and negative test results was 0.37 (95% CI 0.20 to 0.58).

Liver function tests

Although we planned to estimate the summary sensitivity and specificity at each cut‐off point for serum bilirubin and serum ALP, only one study evaluated the tests and so we did not perform meta‐analyses. The study included 262 participants of whom 25 had common bile duct stones (Silverstein 1998). The diagnostic accuracy of serum bilirubin and serum ALP were reported at two cut‐offs for each test. For bilirubin at a cut‐off of greater than 22.23 μmol/L, sensitivity was 0.84 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.94) and specificity was 0.91 (0.86 to 0.94). For bilirubin at a cut‐off of greater than twice the normal limit, sensitivity was 0.42 (95% CI 0.22 to 0.63) and specificity was 0.97 (95% CI 0.95 to 0.99).

For ALP at a cut‐off of greater than 125 IU/L, sensitivity was 0.92 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.99) and specificity was 0.79 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.84). For ALP at a cut‐off of greater than twice the normal limit, sensitivity was 0.38 (95% CI 0.19 to 0.59) and specificity was 0.97 (95% CI 0.95 to 0.99).

Test strategies involving combinations of bilirubin and ALP were not reported.

Combinations of ultrasound and liver function tests

None of the studies assessed the diagnostic accuracy of a combination of ultrasound and liver function tests.

Comparison of ultrasound and liver function tests

We were unable to compare tests formally because only one study evaluated liver function tests (Silverstein 1998). This study also assessed ultrasound and reported higher sensitivities for bilirubin and ALP than ultrasound at both cut‐offs but the specificities of the markers were higher at only the greater than twice the normal limit cut‐off (Figure 5). For ultrasound, sensitivity was 0.32 (95% CI 0.15 to 0.54) and specificity was 0.95 (95% 0.91 to 0.97). For bilirubin at a cut‐off greater than 22.23 μmol/L, sensitivity was 0.84 (95% CI 0.64 to 0.95) and specificity was 0.91 (0.86 to 0.94). For ALP at a cut‐off greater than 125 IU/L, sensitivity was 0.92 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.99) and specificity was 0.79 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.84).

Exploration of heterogeneity

We performed none of the planned investigations of heterogeneity because few studies were included in the review.

Sensitivity analyses

We performed no sensitivity analyses. One study reported the exclusion of two participants, but their reference standard results were not available (Rickes 2006).

Discussion

Summary of main results

Table 1 shows the results for ultrasound and liver function tests. There was considerable variation in the estimates of sensitivity and specificity between the five studies that evaluated ultrasound. For ultrasound, the summary sensitivity was 0.73 (95% CI 0.44 to 0.90) and specificity was 0.91 (95% CI 0.84 to 0.95). At the median pre‐test probability of 40.8%, the post‐test probability for ultrasound was 0.85 (95% CI 0.75 to 0.91) for a positive test result and 0.17 (95% CI 0.08 to 0.33) for a negative test result. Bilirubin and ALP were the two liver function tests assessed in this review. Only one study evaluated both markers and the study also evaluated ultrasound. The study reported two cut‐offs for defining test positivity for bilirubin and ALP. For bilirubin, at cut‐offs of greater than 22.23 μmol/L, the sensitivity was 0.84 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.94) and specificity was 0.91 (95% CI 0.86 to 0.94) and at cut‐offs of greater than twice the normal limit, sensitivity was 0.42 (95% CI 0.22 to 0.63) and specificity was 0.97 (95% CI 0.95 to 0.99). For ALP, at cut‐offs of greater than 125 IU/L, sensitivity was 0.92 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.99) and specificity was 0.79 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.84) and at cut‐offs of greater than twice the normal limit, sensitivity was 0.38 (95% CI 0.19 to 0.59) and specificity was 0.97 (95% CI 0.95 to 0.99). None of the studies assessed the diagnostic accuracy of a combination of ultrasound and liver function tests.

An ideal test should have few false‐positive test results (so that people without common bile duct stones are not diagnosed to have common bile duct stones by the test performed) and few false‐negative test results (so that people with common bile duct stones are not missed by the test). Since relatively non‐invasive tests such as MRCP and EUS follow abnormal transabdominal ultrasound or liver function tests before people undergo invasive tests or treatment, it is acceptable for ultrasound and liver function tests to have false‐positive test results. However, it is not acceptable for ultrasound and liver function tests to have false‐negative results. This is because people with negative ultrasound and liver function tests may not be investigated further and so common bile duct stones may be missed exposing the person to the risk of developing pancreatitis and cholangitis, both of which are life‐threatening conditions. Although some researchers have suggested that there is no need to treat asymptomatic common bile duct stones (Caddy 2005), it is generally recommended that common bile duct stones are removed when they are identified because of the serious complications associated with their presence (Williams 2008). At the minimum pre‐test probability of 9.5%, which is close to the generally accepted 10% to 20% probability of common bile duct stones in people undergoing cholecystectomy (Williams 2008), ALP at a cut‐off of greater than 125 IU/L appeared to have the lowest post‐test probability for a negative test result at 1.0%. This means that approximately 1 out of 100 people with common bile duct stones would be missed by the test but this depends on the pre‐test probability of common bile duct stones. While people with abnormal liver function tests or ultrasound undergo further investigations such as MRCP to determine whether they have stones, it is unlikely that people with normal liver function tests and ultrasound would be subjected to further investigations. Liver function tests identify only whether there is obstruction in the common bile duct while ultrasound has the potential to identify the cause of obstruction by visualisation of a common bile duct stone. Therefore, strategies such as 'either test positive' may improve the sensitivity of the test as some people with normal ultrasound may have an abnormal liver function test and people with normal liver function tests may have an abnormal transabdominal ultrasound. In contrast, a strategy of 'both tests positive' may decrease the sensitivity but improve the specificity. However, these strategies were not evaluated in any of the studies.

Strengths and weaknesses of the review

We searched the literature thoroughly including full‐text publications and abstracts without any language restrictions. The use of diagnostic test accuracy filters may lead to the loss of some studies (Doust 2005), and so we did not use filters. Two authors independently identified and extracted data from the studies potentially decreasing errors related to single data extraction (Buscemi 2006). We used appropriate reference standards; relying on ERCP or IOC as reference standards can result in incorrect information about diagnostic test accuracy (Gurusamy 2015), and should be avoided.

The major limitation in the review process was our inability to explore heterogeneity formally because few studies were included in the review. For ultrasound, visual inspection of the forest plot of sensitivity and specificity and the prediction ellipse on the summary ROC plot indicated considerable differences, especially in sensitivity, between studies and it was not possible to determine the reason for the differences. All studies included people with symptoms (i.e., people with obstructive jaundice or pancreatitis). Four studies used surgical or endoscopic clearance as the reference standard in all participants (Busel 1989; Kumar 1998; Admassie 2005; Rickes 2006). In one study, participants with positive index test underwent surgical or endoscopic extraction of stones while the remaining participants had a clinical follow‐up of a minimum of two years (Silverstein 1998). It is quite possible that the participants included in the first four studies were at greater risk of having common bile duct stones than the last study. This was evident from pre‐test probabilities of common bile duct stones, which ranged from 22% to 66% in studies in which surgical or endoscopic clearance was performed in all participants (Busel 1989; Kumar 1998; Admassie 2005; Rickes 2006) compared to 10% in the study in which different reference standards were used depending upon the results of the index test (Silverstein 1998). Another potential source of heterogeneity was the criterion used to define a positive ultrasound. Two studies used hyperechoic shadowing within the common bile duct as the criterion for a positive ultrasound (Busel 1989; Rickes 2006); one study used dilated common bile duct (Silverstein 1998); one study used a combination of hyperechoic shadowing and dilated common bile duct (Kumar 1998); and the criterion was not stated in one study (Admassie 2005). It was also not possible to perform a comparison of the accuracy of the tests because we found too few studies for inclusion in the review.

The major limitation of the included studies was that none of the studies was of good methodological quality. There was a high proportion of studies at high risk of bias and of high concern regarding applicability in all the four domains. This makes the results potentially unreliable. We considered endoscopic or surgical extraction of common bile duct stones in all participants as a better reference standard than a combination of extraction of common bile duct stones in participants with positive index test and clinical follow‐up in participants with negative index test. However, we acknowledge that even this ideal reference standard can result in misclassification and hence alteration in diagnostic test accuracy if one or more stones reach the small bowel without the knowledge of the person who performed the common bile duct stone extraction.

Despite all these shortcomings, these studies are the best available evidence on the topic.

Applicability of findings to the review question

Most of the participants included in this review were people who had signs or symptoms related to common bile duct stones. The diagnostic accuracy of the tests when applied in people without symptoms with common bile duct stones may be lower. Therefore, unless further information becomes available, relying on these tests to make a diagnosis of common duct stones in people without symptoms cannot be recommended. It should also be noted that this review assessed the diagnostic accuracy of these tests only for the diagnosis of common bile duct stones and not for the diagnosis of other conditions such as benign or malignant biliary stricture and periampullary tumours.

Previous research

This is the first systematic review on this topic using appropriate reference standards.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Many people may have common bile duct stones in spite of having a negative ultrasound or liver function test. Such people may have to be tested with other modalities if the clinical suspicion of common bile duct stones is very high because of their symptoms. It is recommended that further non‐invasive tests be used to confirm common bile duct stones to avoid the risks of invasive testing.

It should be noted that our results are based on studies of poor methodological quality and the results should be interpreted with caution.

Implications for research.

Further studies of high methodological quality are necessary to determine the diagnostic test accuracy of ultrasound and liver function tests. In particular, it would be useful to compare the diagnostic test accuracy of either test positive versus both tests positive approach to inform the role of these triage tests and whether it is safe not to perform other tests if liver function tests and ultrasound do not suggest common bile duct stones. We acknowledge that differential verification cannot always be avoided if endoscopic sphincterotomy and extraction of stones was used as the reference standard because of the complications associated with this procedure (Gurusamy 2011). Surgical exploration of common bile ducts is a major surgical procedure and cannot be undertaken lightly. People with positive test results are likely to undergo endoscopic sphincterotomy and extraction of stones or surgical exploration of common bile ducts while people with negative test results are likely to be followed up. It is recommended that such people be followed up for at least six months to ensure that they do not develop the symptoms of common bile duct stones. Future studies that avoid inappropriate exclusions to ensure that true diagnostic accuracy can be calculated would be informative. Long‐term follow‐up of people with negative test results would help in understanding the implications of false‐negative results and aid clinical decision making.

Notes

This review is based on a common protocol which needed to be split in to three reviews(Giljaca 2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group staff, contact editors Mirella Fraquelli and Agostino Colli, and the UK Cochrane Diagnostic Test Accuracy Review Support Unit for their advice in the preparation of this review.

This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research. Disclaimer of the Department of Health: "The views and opinions expressed in the review are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), National Health Services (NHS), or the Department of Health".

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

| Database | Period of Search | Search Strategy |

| MEDLINE (PubMed) | 1946 to September 2012. | (((bile duct[tiab] or biliary[tiab] OR CBD[tiab]) AND (stone[tiab] OR stones[tiab] OR calculus[tiab] OR calculi[tiab])) OR choledocholithiasis[tiab] OR cholelithiasis[tiab] OR "Choledocholithiasis"[Mesh] OR "Common Bile Duct Calculi "[MESH] OR "Cholelithiasis "[MESH]) AND (CT[tiab] OR tomodensitometry[tiab] OR MRI[tiab] OR NMRI[tiab] OR zeugmatogra*[tiab] OR ((computed[tiab] OR computerised[tiab] OR computerized[tiab] OR magneti*[tiab] OR MR[tiab] OR NMR[tiab] OR proton[tiab]) AND (tomogra*[tiab] OR scan[tiab] OR scans[tiab] OR imaging[tiab] OR cholangiogra*[tiab])) OR "Tomography, X‐Ray Computed"[Mesh] OR "Magnetic Resonance Imaging"[Mesh] OR echogra*[tiab] OR ultrason*[tiab] OR ultrasound[tiab] OR EUS[tiab] OR "Ultrasonography"[Mesh] OR "Endosonography"[Mesh] OR cholangiogra*[tiab] OR cholangio?pancreatogra*[tiab] OR cholangiosco*[tiab] OR choledochosco*[tiab] OR ERCP[tiab] OR MRCP[tiab] OR "Cholangiography"[Mesh] OR "Cholangiopancreatography, Magnetic Resonance"[Mesh] OR liver function test[tiab] OR liver function tests[tiab] OR "Liver Function Tests"[Mesh]) |

| EMBASE (OvidSP) | 1947 to September 2012. | 1. (((bile duct or biliary or CBD) adj5 (stone or stones or calculus or calculi)) or choledocholithiasis or cholelithiasis).tw. 2. exp common bile duct stone/ or exp bile duct stone/ or exp cholelithiasis/ 3. 1 or 2 4. (CT or tomodensitometry or MRI or NMRI or zeugmatogra* or ((computed or computerised or computerized or magneti* or MR or NMR or proton) adj5 (tomogra* or scan or scans or imaging or cholangiogra*))).tw. 5. exp computer assisted tomography/ 6. exp nuclear magnetic resonance imaging/ 7. (echogra* or ultrason* or ultrasound or EUS).tw. 8. exp ultrasound/ 9. (cholangiogra* or cholangio?pancreatogra* or cholangiosco* or choledochosco* or ERCP or MRCP).tw. 10. exp cholangiography/ 11. (liver function test or liver function tests).tw. 12. exp liver function test/ 13. 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 14. 3 and 13 |

| Science Citation Index Expanded (ISI Web of Knowledge) | 1898 to September 2012. | #1 TS=(((bile duct or biliary OR CBD) AND (stone OR stones OR calculus OR calculi)) OR choledocholithiasis OR cholelithiasis) #2 TS=(CT OR tomodensitometry OR MRI OR NMRI OR zeugmatogra* OR ((computed OR computerised OR computerized OR magneti* OR MR OR NMR OR proton) AND (tomogra* OR scan OR scans OR imaging OR cholangiogra*))) #3 TS=(echogra* OR ultrason* OR ultrasound OR EUS) #4 TS=(cholangiogra* OR cholangio?pancreatogra* OR cholangiosco* OR choledochosco* OR ERCP OR MRCP) #5 TS=(liver function test OR liver function tests) #6 #5 OR #4 OR #3 OR #2 #7 #1 AND #6 |

| BIOSIS (ISI Web of Knowledge) | 1969 to September 2012. | #1 TS=(((bile duct or biliary OR CBD) AND (stone OR stones OR calculus OR calculi)) OR choledocholithiasis OR cholelithiasis) #2 TS=(CT OR tomodensitometry OR MRI OR NMRI OR zeugmatogra* OR ((computed OR computerised OR computerized OR magneti* OR MR OR NMR OR proton) AND (tomogra* OR scan OR scans OR imaging OR cholangiogra*))) #3 TS=(echogra* OR ultrason* OR ultrasound OR EUS) #4 TS=(cholangiogra* OR cholangio?pancreatogra* OR cholangiosco* OR choledochosco* OR ERCP OR MRCP) #5 TS=(liver function test OR liver function tests) #6 #5 OR #4 OR #3 OR #2 #7 #1 AND #6 |

| clinicaltrials.gov/ | September 2012. | (bile duct) OR CBD OR choledocholithiasis OR cholelithiasis |

| Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) and Health Technology Assessment (HTA) in The Cochrane Library (Wiley) |

September 2012. | #1 (((bile duct or biliary or CBD) NEAR/5 (stone OR stones OR calculus OR calculi)) OR choledocholithiasis OR cholelithiasis):ti,ab,kw #2 MeSH descriptor Choledocholithiasis explode all trees #3 (#1 OR #2) #4 (CT OR tomodensitometry OR MRI OR NMRI OR zeugmatogra* OR ((computed OR computerised OR computerized OR magneti* OR MR OR NMR OR proton) NEAR/5 (tomogra* OR scan OR scans OR imaging OR cholangiogra*))):ti,ab,kw #5 MeSH descriptor Tomography, X‐Ray Computed explode all trees #6 MeSH descriptor Magnetic Resonance Imaging explode all trees #7 (echogra* OR ultrason* OR ultrasound OR EUS):ti,ab,kw #8 MeSH descriptor Ultrasonography explode all trees #9 MeSH descriptor Endosonography explode all trees #10 (cholangiogra* OR cholangio?pancreatogra* OR cholangiosco* OR choledochosco* OR ERCP OR MRCP):ti,ab,kw #11 MeSH descriptor Cholangiography explode all trees #12 MeSH descriptor Cholangiopancreatography, Magnetic Resonance explode all trees #13 (liver function test OR liver function tests):ti,ab,kw #14 MeSH descriptor Liver Function Tests explode all trees #15 (#4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14) #16 (#3 AND #15) |

| Medion (www.mediondatabase.nl/) | September 2012. | We conducted four separate searches of the abstract using the terms: bile duct CBD choledocholithiasis cholelithiasis |

| ARIF (www.birmingham.ac.uk/research/activity/mds/projects/HaPS/PHEB/ARIF/databases/index.aspx) | September 2012. | (bile duct) OR CBD OR choledocholithiasis OR cholelithiasis |

Data

Presented below are all the data for all of the tests entered into the review.

Tests. Data tables by test.

| Test | No. of studies | No. of participants |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Ultrasound | 5 | 523 |

| 2 Bilirubin (> 22.23 μmol/L) | 1 | 262 |

| 3 Bilirubin (> twice the normal limit) | 1 | 261 |

| 4 Alkaline phosphatase (> 125 IU/L) | 1 | 262 |

| 5 Alkaline phosphatase (> twice the normal limit) | 1 | 261 |

1. Test.

Ultrasound.

2. Test.

Bilirubin (> 22.23 μmol/L).

3. Test.

Bilirubin (> twice the normal limit).

4. Test.

Alkaline phosphatase (> 125 IU/L).

5. Test.

Alkaline phosphatase (> twice the normal limit).

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Admassie 2005.

| Study characteristics | |||

| Patient sampling | Type of study: retrospective. Consecutive or random sample: unclear. | ||

| Patient characteristics and setting | Sample size: 49. Females: 34 (69.4%). Age: 50 years. Presentation: Inclusion criteria:

Setting: Surgery Department, Ethiopia. |

||

| Index tests | Index test: ultrasound. Technical specifications: not stated. Performed by: not stated. Criteria for positive diagnosis: not stated. | ||

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Target condition: common bile duct stones. Reference standard: surgical confirmation of cause for obstructive jaundice. Technical specifications: not applicable. Performed by: surgeons. Criteria for positive diagnosis: surgical confirmation of cause for obstructive jaundice. | ||

| Flow and timing | Number of indeterminates for whom the results of reference standard was available: not stated. Number of participants who were excluded from the analysis: not stated. | ||

| Comparative | |||

| Notes | Attempted to contact the authors in June 2013. Received no replies. | ||

| Methodological quality | |||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns |

| DOMAIN 1: Patient Selection | |||

| Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? | Unclear | ||

| Was a case‐control design avoided? | Yes | ||

| Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | Yes | ||

| High | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 2: Index Test All tests | |||

| Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | Unclear | ||

| If a threshold was used, was it pre‐specified? | Unclear | ||

| High | High | ||

| DOMAIN 3: Reference Standard | |||

| Is the reference standards likely to correctly classify the target condition? | Yes | ||

| Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index tests? | Unclear | ||

| High | High | ||

| DOMAIN 4: Flow and Timing | |||

| Was there an appropriate interval between index test and reference standard? | Unclear | ||

| Did all patients receive the same reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Were all patients included in the analysis? | Unclear | ||

| Unclear | |||

Busel 1989.

| Study characteristics | |||

| Patient sampling | Type of study: retrospective. Consecutive or random sample: unclear. | ||

| Patient characteristics and setting | Sample size: 38. Females: not stated. Age: not stated. Presentation: Inclusion criteria:

Setting: Surgery and Gastroenterology Departments, Chile. |

||

| Index tests | Index test: ultrasound. Technical specifications: sectorial transducer 3.5 MHz (manufacturer not stated). Performed by: not stated. Criteria for positive diagnosis: echogenic image with or without acoustic shadow In the common bile duct. | ||

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Target condition: common bile duct stones. Reference standard: surgical exploration of common bile duct. Technical specifications: not applicable. Performed by: surgeons. Criteria for positive diagnosis: surgical exploration of common bile duct. | ||

| Flow and timing | Number of indeterminates for whom the results of reference standard was available: not stated. Number of participants who were excluded from the analysis: not stated. | ||

| Comparative | |||

| Notes | Attempted to contact the authors in June 2013. Received no replies. | ||

| Methodological quality | |||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns |

| DOMAIN 1: Patient Selection | |||

| Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? | Unclear | ||

| Was a case‐control design avoided? | Yes | ||

| Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | Unclear | ||

| High | High | ||

| DOMAIN 2: Index Test All tests | |||

| Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | Unclear | ||

| If a threshold was used, was it pre‐specified? | Yes | ||

| High | Low | ||

| DOMAIN 3: Reference Standard | |||

| Is the reference standards likely to correctly classify the target condition? | Yes | ||