Abstract

Background

Diagnostic ultrasound is a sophisticated electronic technology, which utilises pulses of high‐frequency sound to produce an image. Diagnostic ultrasound examination may be employed in a variety of specific circumstances during pregnancy such as after clinical complications, or where there are concerns about fetal growth. Because adverse outcomes may also occur in pregnancies without clear risk factors, assumptions have been made that routine ultrasound in all pregnancies will prove beneficial by enabling earlier detection and improved management of pregnancy complications. Routine screening may be planned for early pregnancy, late gestation, or both. The focus of this review is routine early pregnancy ultrasound.

Objectives

To assess whether routine early pregnancy ultrasound for fetal assessment (i.e. its use as a screening technique) influences the diagnosis of fetal malformations, multiple pregnancies, the rate of clinical interventions, and the incidence of adverse fetal outcome when compared with the selective use of early pregnancy ultrasound (for specific indications).

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (30 March 2015) and reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

Published, unpublished, and ongoing randomised controlled trials that compared outcomes in women who experienced routine versus selective early pregnancy ultrasound (i.e. less than 24 weeks' gestation). We have included quasi‐randomised trials.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trials for inclusion and risk of bias, extracted data and checked them for accuracy. We used the Review Manager software to enter and analyse data.

Main results

Routine/revealed ultrasound versus selective ultrasound/concealed: 11 trials including 37,505 women. Ultrasound for fetal assessment in early pregnancy reduces the failure to detect multiple pregnancy by 24 weeks' gestation (risk ratio (RR) 0.07, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.03 to 0.17; participants = 295; studies = 7), moderate quality of evidence). Routine scans improve the detection of major fetal abnormality before 24 weeks' gestation (RR 3.46, 95% CI 1.67 to 7.14; participants = 387; studies = 2,moderate quality of evidence). Routine scan is associated with a reduction in inductions of labour for 'post term' pregnancy (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.83; participants = 25,516; studies = 8), but the evidence related to this outcome is of low quality, because most of the pooled effect was provided by studies with design limitation with presence of heterogeneity (I² = 68%). Ultrasound for fetal assessment in early pregnancy does not impact on perinatal death (defined as stillbirth after trial entry, or death of a liveborn infant up to 28 days of age) (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.12; participants = 35,735; studies = 10, low quality evidence). Routine scans do not seem to be associated with reductions in adverse outcomes for babies or in health service use by mothers and babies. Long‐term follow‐up of children exposed to scan in utero does not indicate that scans have a detrimental effect on children's physical or cognitive development.

The review includes several large, well‐designed trials but lack of blinding was a problem common to all studies and this may have an effect on some outcomes. The quality of evidence was assessed for all review primary outcomes and was judged as moderate or low. Downgrading of evidence was based on including studies with design limitations, imprecision of results and presence of heterogeneity.

Authors' conclusions

Early ultrasound improves the early detection of multiple pregnancies and improved gestational dating may result in fewer inductions for post maturity. Caution needs to be exercised in interpreting the results of aspects of this review in view of the fact that there is considerable variability in both the timing and the number of scans women received.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Infant, Newborn; Pregnancy; Pregnancy, Multiple; Congenital Abnormalities; Congenital Abnormalities/diagnostic imaging; Fetal Monitoring; Fetal Monitoring/methods; Gestational Age; Perinatal Mortality; Pregnancy Trimester, First; Pregnancy Trimester, Second; Ultrasonography, Prenatal; Ultrasonography, Prenatal/methods

Plain language summary

Routine compared with selective ultrasound in early pregnancy

Ultrasound is an electronic technology that uses the reflection of pulses of high‐frequency sound to produce an image. Ultrasound may be used in a variety of circumstances during pregnancy. It has been assumed that the routine use of ultrasound in early pregnancy will result in the earlier detection of problems and improved management of pregnancy complications when compared with selective use for specific indications such as after clinical complications (e.g. bleeding in early pregnancy), or where there are concerns about fetal growth.

The focus of this review is routine early pregnancy ultrasound (before 24 weeks). We included 11 randomised controlled trials involving 37,505 women. Early ultrasound improved the early detection of multiple pregnancies and improved gestational dating, which may result in fewer inductions for post maturity. The detection of fetal malformation was addressed in detail in only two of the trials. There was no evidence of a significant difference between the screened and control groups for perinatal death. Results do not show that routine scans reduce adverse outcomes for babies or lead to less health service use by mothers and babies. Long‐term follow‐up of children exposed to scans before birth did not indicate that scans have a detrimental effect on children's physical or intellectual development. Studies were carried out over three decades and technical advances in equipment, more widespread use of ultrasonography, and increased training and expertise of operators may have resulted in more effective sonography.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Routine/revealed compared with selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy for fetal assessment in early pregnancy.

| Routine/revealed compared with selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy for fetal assessment in early pregnancy | ||||||

| Patient or population: Pregnant women at less than 24 weeks' gestation undergoing fetal assessment by ultrasound Settings: Norway, United Kingdom, United States and Sweden Intervention: Routine/revealed Comparison: Selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy | Routine/revealed | |||||

| Detection of fetal abnormality before 24 weeks' gestation | Study population | RR 3.46 (1.67 to 7.14) | 387 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | ||

| 44 per 1000 | 153 per 1000 (74 to 316) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 25 per 1000 | 85 per 1000 (41 to 175) | |||||

| Detection of multiple pregnancy by 24 to 26 weeks' gestation (number NOT detected) | Study population | RR 0.07 (0.03 to 0.17) | 295 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | ||

| 394 per 1000 | 28 per 1000 (12 to 67) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 250 per 1000 | 18 per 1000 (8 to 43) | |||||

| Induction of labour for 'post‐term' pregnancy | Study population | RR 0.59 (0.42 to 0.83) | 25516 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1,2 | ||

| 31 per 1000 | 18 per 1000 (13 to 25) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 38 per 1000 | 22 per 1000 (16 to 32) | |||||

| Perinatal death (all babies) | Study population | RR 0.89 (0.70 to 1.12) | 35735 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1,3 | ||

| 8 per 1000 | 7 per 1000 (6 to 9) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 10 per 1000 | 9 per 1000 (7 to 11) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Most of the pooled effect provided by studies with design limitations, including poor reporting of allocation concealment methods (‐1).

2Presence of heterogeneity (I² = 68%) (‐1).

3Wide CI crossing the line of no effect (‐1).

Background

Diagnostic ultrasound examination may be employed in a variety of specific circumstances during pregnancy, such as after clinical complications, or where there are concerns about fetal growth. Because adverse outcomes may also occur in pregnancies without clear risk factors, assumptions have been made that routine ultrasound in all pregnancies will prove beneficial by enabling earlier detection and improved management of pregnancy complications. Routine screening may be planned for early pregnancy, late gestation, or both. The focus of this review is routine early pregnancy ultrasound.

Description of the intervention

Diagnostic ultrasound is a sophisticated electronic technology that utilises pulses of high‐frequency sound to produce an image. A transducer, which is moved across the area to be examined, emits pulses of ultrasound that propagate through the tissues. Some pulses are reflected back to the transducer, which converts these returning echoes into electronic signals. The strength of the returning echo is determined by tissue interface characteristics. Returning signals are processed by a computer that displays each echo in both strength and position as an image on a screen. The quality of ultrasound imaging is dependent not only on the technical capabilities of the ultrasound equipment, but also on the experience and expertise of the operator; and standards are variable.

Diagnostic ultrasound examination may be employed in a variety of specific circumstances during pregnancy, such as: after clinical complications (e.g. bleeding in early pregnancy); where the fetus is perceived to be at particularly high risk of malformation; and where there are concerns regarding fetal growth. Because adverse outcomes may also occur in pregnancies without clear risk factors, assumptions have been made that the routine use of ultrasound in all pregnancies will prove beneficial. The rationale for such screening would be the detection of clinical conditions that place the fetus or mother at high risk, which would not necessarily have been detected by other means such as clinical examination, and for which subsequent management would improve perinatal outcome. Routine screening examinations may be planned for early pregnancy, late gestation, or both. The focus of this review is routine early pregnancy ultrasound; late pregnancy screening has been addressed in another Cochrane review (Bricker 2008).

The use of ultrasound to identify women at risk of preterm delivery by assessment of the cervix may be a component of screening before 24 weeks; this is outside the remit of this review and is considered elsewhere (Berghella 2013; Crane 2008).

How the intervention might work

Early Pregnancy complications and serum screening

An ultrasound at the time of antenatal booking may enable non‐viable pregnancies to be detected earlier than is possible using clinical presentation. This has implications for clinical management of these pregnancies. In addition, earlier detection of ectopic pregnancy may be possible allowing for medical rather than surgical management, or 'minimally invasive' rather than open surgery. Between 11% and 42% of gestational age estimations taken from the menstrual history are reported as inaccurate (Barrett 1991; Geirsson 1991; Peek 1994). A reliable estimate of gestational age is required for maternal serum screening for fetal abnormality to be accurately timed (Owen 1997). Accurate knowledge of gestational age may increase the efficiency of maternal serum screening and some late pregnancy fetal assessment tests.

Multiple Pregnancy

Multiple pregnancies are associated with increased perinatal morbidity and mortality compared to singleton pregnancies (Dodd 2005). Determination of chorionicity plays an important role in risk stratification when managing twin pregnancies. Routine early pregnancy scanning in this group may impact on accuracy of assignment of chorionicity in multiple pregnancies, as some studies have shown that this can be done more accurately at earlier gestations (Lee 2006). It is also possible that earlier diagnosis of multiple pregnancy will occur with routine early pregnancy scanning, thus preventing inappropriate maternal serum screening (Persson 1983; Saari‐Kemppainen 1990).

Detection of structural fetal abnormalities

In a systematic review, based on 11 studies (one randomised controlled trial, six retrospective cohorts and four prospective cohorts), undertaken to examine the use of routine second trimester ultrasound to detect fetal anomalies, the overall prevalence of fetal anomaly was 2.09%, ranging from 0.76% to 2.45% in individual studies and including major and minor anomalies (Bricker 2000). Using late pregnancy ultrasound scanning overall, detection of fetal anomaly was 44.7%, with a range of 15.0% to 85.3% (Bricker 2000). Optimum timing of such ultrasound scans may be aided by accurate estimation of dates using routine early pregnancy scanning.

Timing of delivery

A recent Cochrane review concluded that compared with a policy of expectant management, a policy of labour induction is associated with fewer perinatal deaths (Gulmezoglu 2012). It is possible that routine early pregnancy scanning will improve the accuracy of pregnancy dating and thereby affect the number of pregnancies undergoing induction for post‐maturity. Whilst there is evidence to suggest that ultrasound is very attractive to women and families, studies have also shown that women often lack information about the purposes for which an ultrasound scan is being done and the technical limitations of the procedure (Bricker 2000). It is therefore essential that women's satisfaction is considered.

Why it is important to do this review

The use of routine pregnancy ultrasound needs to be considered in the context of potential hazards. In theory, some ultrasonic energy propagated through tissue is converted to heat, and in laboratory experiments, biological effects of ultrasound have been observed. However, these effects have been produced using continuous wave ultrasound with long 'dwell' time (time insonating one area) and high‐power output. In the clinical setting, diagnostic ultrasound uses pulsed waves (short pulses of sound propagation), and most modern machines are designed so that safe power output limits cannot be exceeded. Operators are always advised to apply the ALARA (as low as reasonably attainable) principle to the ultrasound power output used (EFSUMB 1995), and to ensure time taken for an examination, including the 'dwell' time over a specific target, is kept to a minimum. One of the aims of this review is to assess available data and determine whether clear epidemiological evidence exists from clinical trials that ultrasound examination during pregnancy is harmful.

Objectives

To assess whether routine early pregnancy ultrasound for fetal assessment (i.e. its use as a screening technique) influences the diagnosis of fetal malformations, multiple pregnancies, the rate of clinical interventions, and the incidence of adverse fetal outcome when compared with the selective use of early pregnancy ultrasound (for specific indications).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All published, unpublished, and ongoing randomised controlled trials with reported data that compared outcomes in women who experienced routine early pregnancy ultrasound with outcomes in women who experienced the selective use of early pregnancy ultrasound. We included quasi‐randomised controlled trials. Cluster‐randomised trials were also eligible for inclusion.

We planned to include trials reported as abstracts provided that they contained sufficient information for us to assess eligibility and risk of bias, and that results were described in sufficient detail. Where insufficient information was provided in abstracts, we have included studies in Characteristics of studies awaiting classification until publication of the full study report or until we can obtain further information from authors.

Types of participants

Women with early pregnancies, i.e. less than 24 weeks' gestation.

Types of interventions

Routine ultrasound examination compared with selective ultrasound examination.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Detection of major fetal abnormality (as defined by the trial authors) prior to 24 weeks' gestation.

Detection of multiple pregnancy by 24 weeks' gestation.

Induction of labour for 'post‐term' pregnancy.

Perinatal death (defined as stillbirth after trial entry, or death of a liveborn infant up to 28 days of age).

Secondary outcomes

Detection

Non‐viable pregnancy prior to clinical presentation.

Ectopic pregnancy prior to clinical presentation.

Chorionicity of multiple pregnancy (in first trimester or in second trimester).

Multiple pregnancy prior to labour.

Soft markers before 24 weeks' gestation (i.e. structural features in the fetus that are of little or no functional significance (e.g. choroid plexus cyst, echogenic bowel), but which can be associated with increased risk of chromosomal disorder, e.g.Trisomy 21).

Major anomaly before birth.

Complications for infants and children

Birthweight.

.Gestation at delivery.

Low birthweight (defined as less than 2500 g at term in singletons).

Very low birthweight (defined as less than 1500 g at term in singletons).

Apgar score less than or equal to seven at five minutes.

Admission to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

Respiratory distress syndrome.

Death or major neurodevelopmental handicap at childhood follow‐up.

Poor oral reading at school.

Poor reading comprehension at school.

Poor spelling at school.

Poor arithmetic at school.

Poor overall school performance.

Dyslexia.

(Rreduced hearing in childhood.

Reduced vision in childhood.

Use of spectacles.

Non right‐handedness.

Ambidexterity.

Disability at childhood follow‐up.

Maternal outcomes

Appropriately timed serum screening tests.

Laparoscopic management of ectopic pregnancy.

Surgical management of abortion.

Appropriately timed anomaly scan (18 to 22 weeks).

Termination of pregnancy for fetal abnormality.

Antenatal hospital admission.

Induction of labour for any reason.

Caesarean section.

Measures of satisfaction

Woman not satisfied.

Women's preferences for care.

Costs

Costs associated with routine early pregnancy ultrasound versus selective early pregnancy ultrasound.

Number of antenatal visits.

Length of stay in NICU.

Infant length of hospital stay.

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (30 March 2015).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

monthly searches of CINAHL (EBSCO);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

Searching other resources

We examined cited references, abstracts, letters to the editor, and editorials for additional studies. Where necessary, we contacted the primary investigator directly to obtain further data.

We did not apply any language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For methods used in the previous version of this review, seeWhitworth 2010.

For this update, the following methods were used for assessing the six new reports that were identified as a result of the updated search and the four reports in the 'Studies awaiting classification' of the previous version of the review (Whitworth 2010).

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted the third review author.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted the third review author. We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2014) and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we contacted authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we planned to assess the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it is likely to impact on the findings. We explored the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Assessment of the quality of the body of evidence

For this update, we assessed the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach (Schunemann 2009). We assessed the quality of the body of evidence relating to the following outcomes for the main comparison of routine early ultrasound scan versus no early ultrasound.

Detection of major fetal abnormality (as defined by the trial authors) prior to 24 weeks' gestation.

Detection of multiple pregnancy by 24 weeks' gestation.

Induction of labour for 'post‐term' pregnancy.

Perinatal death (defined as stillbirth after trial entry, or death of a liveborn infant up to 28 days of age).

We used GRADEprofiler (GRADEpro 2014) to import data from Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan 2014) in order to create a ’Summary of findings’ table. We produced a summary of the intervention effect and a measure of quality for each of the above outcomes using the GRADE approach. The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence can be downgraded from 'high quality' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates or potential publication bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

We used the mean difference if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. In future updates, if the data dictate, we will use the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measure the same outcome, but use different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We did not include cluster‐randomised trials in this update. If in future cluster‐randomised trials are identified, we will include them in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials. We will adjust their sample sizes using the methods described in the Handbook [Section 16.3.4 or 16.3.6] using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Cross‐over trials

Cross‐over trials were not eligible for inclusion in this review.

Other unit of analysis issue

We have included multiple pregnancies in this review but we have not done any adjustment. Multiple pregnancy data were analysed along side singleton births.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. In future updates, if more eligible studies are included, we will explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if an I² was greater than 30% and either the Tau² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity. If we identified substantial heterogeneity (above 30%), we planned to explore it by pre‐specified subgroup analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots, if there were 10 or more studies in the analysis. One analysis did include 10 studies (perinatal death). For this outcome, we assessed funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry was suggested by a visual assessment, we planned to perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2014). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials were examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods were judged sufficiently similar.

If there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity was detected, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary, if an average treatment effect across trials was considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary was treated as the average of the range of possible treatment effects and we discussed the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect was not clinically meaningful, we did not combine trials. Where we used random‐effects analyses, the results were presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of Tau² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If we identified substantial heterogeneity, we investigated it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We considered whether an overall summary was meaningful, and if it was, we used random‐effects analysis to produce it.

Planned subgroup analyses included:

parity (nulliparous versus multiparous women);

selective performance of ultrasound versus selective reporting of ultrasound findings;

first scan occurring in first trimester (up to 14 weeks’ gestation) versus second trimester (14 to 24 weeks’ gestation).

We carried out subgroup analyses for the review’s primary outcomes (induction for post‐term pregnancy, perinatal death, and detection of multiple pregnancy and abnormality before 24 weeks’ gestation). We assessed differences between subgroups by visual inspection of the forest plots and the subgroups’ confidence intervals; non‐overlapping confidence intervals indicating a statistically significant difference in treatment effect between the subgroups. If we suspected any differences between subgroups we planned to seek statistical advice.

We assessed subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan (RevMan 2014). We reported the results of subgroup analyses quoting the Chi² statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to carry out sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of trial quality assessed by concealment of allocation, high attrition rates, or both, with poor quality studies being excluded from the analyses in order to assess whether this makes any difference to the overall result.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

For the previous version of this review (Whitworth 2010), we identified 63 papers reporting findings from 24 studies examining ultrasound for fetal assessment in early pregnancy (most studies resulted in several publications or reports). We included 11 trials involving 37,505 women. One study had no published data (Newcastle 2004); we contacted the authors of this study and added it to Studies awaiting classification. In addition, one of the included studies (Norway 1993) reported long‐term, childhood outcome data from two of the included trials (Alesund 1984; Trondheim 1984). We excluded 11 studies.

For this current version of the review, an updated search in March 2015 identified six new reports. One new trial (McClure 2014), has been added to ongoing studies. We identified one additional report for Sweden 1988 and one additional report for Johannesburg 2007. Three reports of new studies have been excluded (Georgsson Ohman 2010; Schifano 2010; Votino 2012). Newcastle 2004 still has no published data and therefore is still awaiting assessment.

Included studies

The studies were carried out in a number of countries: Australia (Adelaide 1999); the USA (RADIUS 1993 (a multicentre study); Missouri 1990); South Africa (Johannesburg 2007; Tygerberg 1996); Sweden (Sweden 1988); Norway (Alesund 1984; Trondheim 1984); the UK (London 1982; Oxford 2006) and Finland (Helsinki 1990). The earliest trials began recruitment in the late 1970s (Alesund 1984; Trondheim 1984).

All of the trials included an intervention involving an ultrasound examination before the 24th week of pregnancy. The dates of the scans, and the number of scans women received varied in different trials. In the London 1982 trial, all women (in both the intervention and control groups) were offered a scan, but while in the intervention group results were revealed in the women's case notes, in the control group results were concealed unless they were specifically requested by clinical staff. In all other included studies, women in the intervention group were offered a "routine" scan whilst those in the control groups received a scan at the discretion of clinical staff ("selective scans"). Ultrasound scans in the intervention group may have been the only 'routine' scan offered, or may have been an additional scan, with women in both intervention and control groups having scans scheduled at a later stage of pregnancy.

The gestational age at which index scans were performed, and the purpose of scans, varied in different trials. In the Adelaide 1999 study, scans in the intervention group were carried out at between 11 and 14 weeks. The purposes of the scan were to ascertain gestational age (with the aim of improving the timing of other screening tests), identify multiple pregnancies, and to carry out a limited examination of fetal morphology. Women in both treatment and control arms of this study had a routine morphology scan at 18 to 20 weeks' gestation.

In the two Norwegian studies, women in the intervention group were offered two scans, the first at 18 to 20 weeks and then a late ultrasound scan at 32 weeks (Alesund 1984; Trondheim 1984), with follow‐up data for both studies reported in the Norway 1993 papers. The purposes of the early scan were to measure biparietal diameter (BPD); to estimate the expected date of delivery (EDD); to identify multiple pregnancies; to note the location of the placenta; and to carry out a general examination of the fetus.

The ultrasound in the intervention group of the Helsinki 1990 trial was carried out between 16 and 20 weeks; the aims were similar to those in the Norwegian trials, with the amount of amniotic fluid also being recorded.

The main aim in the London 1982 study was BPD measurement and assessment of the EDD; scans were performed at approximately 16 weeks. In the Missouri 1990 trial, scans generally took place between 10 to 12 weeks (up to 18 weeks) and were carried out to estimate gestational age, identify multiple pregnancies, assess fetal viability, and to identify uterine abnormalities. The Sweden 1988 study had similar aims; women attending 19 antenatal clinics in Stockholm were invited for a scan at 15 weeks (range 13 to 19 weeks) (intervention) or received selective scans after 19 weeks (control).

In the Oxford 2006 study, women in both the intervention and control groups had routine scans at 18 to 20 weeks; in addition, women in the intervention group were offered an early scan (at between eight and 12 weeks) to estimate gestational age.

In a large multicentre trial in the USA (RADIUS 1993), women in the intervention group were offered scans at 18 to 20 weeks and at 31 to 33 weeks versus selective scans. The purpose of the earlier scan was to identify the location of the placenta, the volume of amniotic fluid, uterine abnormalities, multiple pregnancies, BPD and other measures of fetal size, and a detailed assessment of fetal anatomy.

In the South African study (Tygerberg 1996), a single scan was offered to women in the intervention group; women received a scan which aimed to ascertain gestational age and to identify major fetal anomalies. Finally, in the Johannesburg 2007 trial, scans in the intervention group were carried out between 18 and 23 weeks. The purpose of the scan was determination of single or multiple pregnancy; placental site identification; estimation of gestation age based on a combination of biparietal diameter, head circumference and femur length measurements, and to search for fetal abnormalities.

Further details of settings, participants and interventions are set out in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

Excluded studies

Altogether, 14 studies have been excluded (Belanger 1996; Bennett 2004; Duff 1993; Georgsson Ohman 2010; Hong Kong; Larsen 1992; Leung 2006; Owen 1994; Rustico 2005; Saltvedt 2006; Schifano 2010; Schwarzler 1999; Votino 2012; Wald 1988).

In four of the excluded studies, all participants (in both the intervention and control groups) received early scans. In the studies by Saltvedt 2006 and Schwarzler 1999, the timing of scans was examined (i.e. earlier versus later scans); in the study by Duff 1993, women in the intervention group had an additional scan in the third trimester; and Owen 1994 looked at women with a high risk of fetal anomaly, with women in the intervention group receiving more frequent scans.

In Bennett 2004, the focus was specifically on the timing of the assessment of gestational age with scans in the first and second trimesters. In Larsen 1992, the participants were high‐risk women, with those in the intervention group receiving an additional scan at 28 weeks. Two trials compared two versus three or four dimensional ultrasound scans (Leung 2006; Rustico 2005). In the Hong Kong study, women in both arms of the trial had two routine scans; in the intervention group the earlier scan was more detailed than in the control group. The study by Belanger 1996 did not include results relevant to the outcomes of the review. We contacted the authors of Wald 1988, but results were not available.

Risk of bias in included studies

See Figure 1 and Figure 2 for a summary of ’Risk of bias’ assessments.

1.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

In the majority of the included studies, no information was provided on the methods used to generate the sequence for randomisation. In the Adelaide 1999 study, a table of random numbers was used to generate the allocation order, and in the RADIUS 1993 study, the sequence was determined by a computerised random number generator. In two studies there was balanced block randomisation (Missouri 1990 (block size four) and Oxford 2006 (block size six)).

We assessed two studies as having inadequate methods to conceal group allocation; in the London 1982 study there was quasi‐random allocation to groups using the women's hospital number to determine allocation, while in the Johannesburg 2007 trial, women were allocated to intervention and control groups according to day of the week. In the RADIUS 1993 study, the methods used for allocating women to randomisation group were not clear. In all the remaining studies, the study allocation was concealed in sealed envelopes; in the Adelaide 1999, Missouri 1990 and Oxford 2006 studies envelopes were described as numbered, opaque, and sealed; in the Tygerberg 1996 and Sweden 1988 studies envelopes were sealed and opaque; while the Alesund 1984, Helsinki 1990, and Trondheim 1984 reports refer to the "sealed envelope method" of randomisation.

Blinding

Blinding women and clinical staff to group allocation was generally not feasible as women in the two treatment arms received different care, and the results of scans were recorded in women's case notes. In the Trondheim 1984 study outcome assessment was described as partially blinded. In the London 1982 study the results of the scan for the control group were not stored in case notes and therefore not available to outcome assessors (although outcome assessors would be aware of group allocation by the presence or absence of the scan report).

The lack of blinding in these studies is unlikely to affect some review outcomes (such as perinatal mortality), but outcomes relying on clinical judgement (e.g. the decision to induce labour for post‐term pregnancy) may possibly be influenced by knowledge of group allocation and this is a potential source of bias; such outcomes should be interpreted with caution.

Incomplete outcome data

The loss of women to follow‐up and levels of missing data for pregnancy outcomes were generally low in these studies (less than 5%). In Missouri 1990, 9% of the sample were lost to follow‐up after randomisation, and in the Oxford 2006 study 15% were lost, but an intention‐to‐treat analysis, including all women randomised, was carried out for the main study outcomes. There was relatively high attrition in Johannesburg 2007; 15.7% of women randomised were lost to follow‐up and there were further missing data for some outcomes; reasons for attrition were not described, and it was not clear how many women from each group were lost.

We have attempted to use consistent denominators in the analyses within this review. For pregnancy and early postnatal outcomes, we tried to include all women randomised less: those women that were not actually pregnant; those who had pre‐screening pregnancy termination; and those who experienced an early spontaneous miscarriage. We included women lost to follow‐up for other reasons (for example, did not attend for screening, withdrew from the study, missing data) in the denominators. In some cases, it was difficult to determine the denominators, as detailed information on attrition at different stages was not reported (in the Johannesburg 2007 study it was not clear how many women were randomised to each study group, and so we had to use the group denominators for those women available to follow‐up). For outcomes for "all babies", we have used the total number of babies (including babies from multiple pregnancies); some outcomes (e.g. birthweight) are specified for singletons only. Again, it was not always easy to ascertain the appropriate denominators for babies.

For long‐term follow‐up, where there was greater attrition (for example, there was complete data for approximately half of the original sample for some outcomes at childhood follow‐up in the Sweden 1988 study), we have used the denominators reported by the authors in study publications.

For some competing/overlapping outcomes (e.g. perinatal deaths, miscarriages and pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality) we have reported figures provided in the trial reports, but we advise caution in interpreting such data. We will return to this issue in the Discussion.

Selective reporting

We found no evidence of selective reporting. However, protocols were not available for us to assess this, so we do not know the original planned outcomes.

Other potential sources of bias

Some of the trials had other potential sources of bias: the Oxford 2006 study was stopped part way through and results are difficult to interpret, and in Alesund 1984, there was some baseline imbalance between groups in smoking rates. While not a source of bias as such, large numbers of women were not eligible for inclusion in the RADIUS 1993 trial and this may affect the generalisability of results.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Routine/revealed ultrasound versus selective ultrasound/concealed results: 11 trials including 37,505 women

Primary outcomes

1. Detection of major fetal abnormality (as defined by the trial authors) prior to 24 weeks' gestation

The detection of fetal abnormalities before 24 weeks in the screened and unscreened groups was reported in two studies; these studies (17,158 pregnancies) recorded a total of 387 fetal abnormalities with most being undetected at 24 weeks (346, 89% not detected by 24 weeks). It was more likely for the screened group to have abnormalities detected by 24 weeks compared with controls (unweighted percentages 16% versus 4%; risk ratio (RR) 3.46, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.67 to 7.14; participants = 387; studies = 2) (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 1 Detection of fetal abnormality before 24 weeks' gestation.

2. Detection of multiple pregnancy by 24 weeks' gestation

Failure to detect multiple pregnancies by 24 weeks was reported in seven studies. It was more likely that multiple pregnancies would not be detected by 24 weeks in the unscreened groups; only two of 153 multiple pregnancies were undetected at 24 weeks in the screened groups, compared with 56 of 142 in the control groups (RR 0.07, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.17; participants = 295; studies = 7) (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 2 Detection of multiple pregnancy by 24 to 26 weeks' gestation (number NOT detected).

3. Induction of labour for 'post‐term' pregnancy

Eight studies reported rates of induction of labour for 'post‐dates' pregnancy (which accounted for approximately 13% of total inductions). Compared with controls, women offered early routine ultrasound were less likely to be induced for post‐maturity. For this outcome there was a high level of heterogeneity between studies. A visual examination of the forest plot reveals that the general direction of findings is the same among studies; however, the size of the treatment effect and the rates of induction in control groups vary. We used a random‐effects model in the meta‐analysis and the average treatment effect favoured the screened group (average RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.83; participants = 25,516; studies = 8; I² = 68%) (Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 3 Induction of labour for 'post‐term' pregnancy.

4. Perinatal death (defined as stillbirth after trial entry, or death of a liveborn infant up to 28 days of age)

There was no evidence of a significant difference between the screened and control groups for perinatal mortality (unweighted percentages 0.73 versus 0.82%; RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.12; participants = 35,735; studies = 10) (Analysis 1.4). When lethal malformations were excluded, rates of perinatal death in the screened and unscreened groups were very similar (0.53 versus 0.56%), (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.27; participants = 34,331; studies = 8) (Analysis 1.5).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 4 Perinatal death (all babies).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 5 Perinatal death (excluding lethal malformations).

Secondary outcomes

Detection of abnormalities and multiple pregnancies prior to labour

All multiple pregnancies (140) were detected before labour in the intervention groups, whereas 12 of the 133 in the control groups remained undetected at the onset of labour (RR 0.12, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.54; participants = 273; studies = 5) (Analysis 1.6). Screened groups were also more likely to have major fetal anomalies detected before birth (RR 3.19, 95% CI 1.99 to 5.11; participants = 387; studies = 2) (Analysis 1.7).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 6 Detection of multiple pregnancy before labour (number NOT detected).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 7 Detection of major anomaly before birth.

Complications for infants and children

There was no evidence of significant differences between groups in terms of the number of low birthweight babies (less than 2500 g) (average RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.33; participants = 19,337; studies = 8; I² = 67%) (Analysis 1.8), or very low birthweight babies (less than 1500 g); (average RR 1.26, 95% CI 0.27 to 5.82; participants = 1584; studies = 2; I² = 52%) (Analysis 1.9). For these outcomes, some studies reported results for singletons only, and so in the analyses we have set out results for singletons and all babies separately. There was no evidence of statistically significant differences between groups in the number of babies that were small‐for‐gestational age (average RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.35; participants = 17105; studies = 3; I² = 40%) (Analysis 1.10), or in mean birthweight (mean difference (MD) 10.67, 95% CI ‐19.77 to 41.11; participants = 23213; studies = 5; I² = 59%) (Analysis 1.11). There were high levels of heterogeneity for outcomes relating to low birthweight, and these results should be interpreted with caution.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 8 Low birthweight (less than 2500 g).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 9 Very low birthweight (< 1500 g).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 10 Small‐for‐gestational age.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 11 Mean birthweight (g).

The number of babies with low Apgar scores (seven or less) at five minutes was similar in the two groups (average RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.33 to 1.72; participants = 3906; studies = 4; I² = 44%)) (Analysis 1.12), and there was no difference in rates of admission to neonatal intensive care (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.02; participants = 19,088; studies = 8) (Analysis 1.13).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 12 Apgar score 7 or less at 5 minutes.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 13 Admission to neonatal intensive care unit (various definitions).

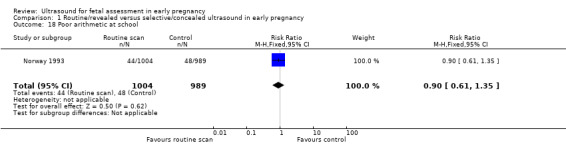

In three studies, babies were followed up into childhood (results for children up to nine years in the Alesund 1984 and Trondheim 1984 trials are reported together in Norway 1993, and the Sweden 1988 study includes data for children at eight to nine years and for teenagers aged 15 to 16 years). For children aged eight to nine years, there were no significant differences for any of the outcomes reported including school performance, hearing and vision, disabilities or dyslexia (which was measured in a subset of the main sample) (Analysis 1.14; Analysis 1.15; Analysis 1.16; Analysis 1.17; Analysis 1.18; Analysis 1.19; Analysis 1.20; Analysis 1.21; Analysis 1.22; Analysis 1.23; Analysis 1.24; Analysis 1.25).There was concern raised regarding an excess of non‐right handedness in the intervention group in the Norwegian study; however, the Swedish study did not confirm these findings, and results may have occurred by chance. Examination of the school records of teenagers (aged 15 to 16 years) revealed little difference in the performance of children whose mothers had been randomised to ultrasound or no ultrasound in the Swedish trial. Data were available for 94% of singletons in the original sample. Authors reported that there was no strong evidence of differences between groups for school performance (grades over all subjects) for girls or boys. For physical education, there was a small difference in scores for boys; those whose mothers had been randomised to the ultrasound group had slightly lower mean scores compared to those in the control group, but this finding was not statistically significant.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 14 Impaired development (screened using the Denver developmental screening test) at childhood follow‐up.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 15 Poor oral reading at school.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 16 Poor reading comprehension at school.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 17 Poor spelling at school.

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 18 Poor arithmetic at school.

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 19 Poor overall school performance.

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 20 Dyslexia.

1.21. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 21 Reduced hearing in childhood.

1.22. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 22 Reduced vision in childhood.

1.23. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 23 Use of spectacles.

1.24. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 24 Non right‐handedness.

1.25. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 25 Ambidexterity.

Maternal outcomes

It was more likely that women would undergo pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality in the screened groups, although overall the number of terminations was small (24 of 14,237 pregnancies in screened groups were terminated after detection of abnormality compared with 10 of 14,019 in controls) (RR 2.23, 95% CI 1.10 to 4.54; participants = 28,256; studies = 5) (Analysis 1.28).

1.28. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 28 Termination of pregnancy for fetal abnormality.

There was no significant evidence that ultrasound was associated with reduced numbers of women undergoing delivery by caesarean section (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.12; participants = 22,193; studies = 5) (Analysis 1.32). Overall, on average, there were slightly fewer inductions of labour (for any reason, including post‐maturity) in women in the screened groups; in view of heterogeneity we used a random‐effects model for this outcome (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.97; participants = 24790; studies = 7; I² = 84%) (Analysis 1.31). The rate of induction in the screened group was 18.8% versus 19.8% in the control group (unweighted percentages).

1.32. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 32 Caesarean section.

1.31. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 31 Induction of labour for any reason.

The Adelaide 1999 trial examined whether an early scan would reduce the number of serum screening tests or fetal anomaly scans that needed to be repeated because they had been performed at the wrong gestational age. There was no significant evidence that the numbers of women having repeat testing was reduced in the intervention group (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.45 to 1.76; participants = 602; studies = 1) (Analysis 1.26); (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.08; participants = 602; studies = 1) (Analysis 1.27). There was also no significant evidence in the Helsinki 1990 and Johannesburg 2007 trials that the number of antenatal visits was reduced (MD 0.16, 95% CI ‐0.33 to 0.65; participants = 9502; studies = 2; I² = 91%) (Analysis 1.29), and pooled results from five trials showed no significant reduction in antenatal hospital admissions (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.18; participants = 17,785; studies = 6; I² = 67%) (Analysis 1.30).

1.26. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 26 Appropriately timed serum screening tests (number having repeat screening).

1.27. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 27 Appropriately timed anomaly scan (18 to 22 weeks)(number NOT appropriately timed).

1.29. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 29 Number of antenatal visits.

1.30. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 30 Antenatal hospital admission.

In the Adelaide 1999, study investigators examined whether having an early scan was reassuring or worrying to mothers. Fewer mothers in the screened group reported feeling worried about their pregnancies (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.65 to 0.99; participants = 634; studies = 1) (Analysis 1.33).

1.33. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 33 Mother not satisfied with care (worried about pregnancy).

Costs of care

The impact of screening on costs to women and health services was examined in two trials.

In the Helsinki 1990 study, the average time spent in the hospital was 61 minutes and women spent 74 minutes travelling to hospital; 81% of the sample were working, and half of the working women used work time to attend for initial screening (some women may have had to attend for further screening‐induced appointments).

The cost to health services was not simple to calculate; the cost of the examinations was offset by fewer hospital visits and stays, and in this study there was a lower perinatal mortality rate and increased pregnancy termination in the screened group, leading the authors to conclude that ultrasound resulted in cost savings (Leivo 1996).

The issue of cost was also examined in a trial carried out in a low‐resource setting where overall adverse fetal outcome was higher, but where fetal anomalies represented a smaller proportion of adverse outcomes compared with high‐resource settings. An explicit aim of the Tygerberg 1996 study was to examine whether the costs of routine ultrasound for all women (rather than selective ultrasound) would be offset by a reduction in the use of other healthcare resources. In this study, routine ultrasound was perceived as being an expensive luxury: "In our less privileged community, however, the cost of investigation is in direct competition with resources for more urgent needs in healthcare and housing, sanitation, education and unemployment ... a routine obstetric ultrasonography policy is expensive and ... the more selective use is not accompanied by an increase in adverse perinatal outcome" (Tygerberg 1996 p.507).

Other outcomes

Included studies did not report data for a number of the secondary outcomes pre‐specified in our review protocol including the detection of ectopic pregnancy or chorionicity of multiple pregnancy, laparoscopic management of ectopic pregnancy and surgical management of abortion.

Subgroup and sensitivity analysis

We planned subgroup analysis by parity, by the timing of the early ultrasound (before or after 14 weeks) and by whether the control group had scans (with results concealed) rather than selective scans. We examined subgroups for primary outcomes only.

Parity

Information on parity was not available for us to be able to carry out this analysis.

Timing of early scan

In three studies the early scan was planned for before 14 weeks' gestation. In the Adelaide 1999 study, scans were planned for 11 to 14 weeks, in Oxford 2006 10 to 12 weeks, and in Missouri 1990, while scans could be performed up to 18 weeks, most were carried out between 10 and 12 weeks. There were no clear differences between subgroups where scans were performed earlier rather than later for perinatal death ( Analysis 1.36). The detection of multiple pregnancy by 24 to 26 weeks' gestation appears better in those scanned after 14 weeks' gestation (Analysis 1.34), although only one study (Missouri 1990) reported this outcome for women scanned prior to 14 weeks with small event numbers. For detection of multiple pregnancy prior to 24 to 26 weeks' gestation In the Adelaide 1999 and Oxford 2006 studies, the treatment effect appeared more conservative than in some of the other studies; this may be because women in both arms of these trials had routine ultrasound scheduled at 18 to 20 weeks' gestation. Compared with controls, women offered early routine ultrasound after 14 weeks' gestation were less likely to be induced for post‐maturity (Analysis 1.35), whilst scans prior to 14 weeks' gestation had no impact.

1.36. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 36 Subgroup analysis: perinatal death (earlier and late scans).

1.34. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 34 Subgroup analysis by timing of scan: detection of multiple pregnancy by 24‐26 weeks' gestation (number not detected).

1.35. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 35 Subgroup analysis: induction of labour for 'post‐term' pregnancy (early and later scans).

Concealed results and routine care

In one study, women in both groups were screened but results were revealed for the intervention group only (London 1982). This study examined two of the review's primary outcomes: detection of multiple pregnancy before 24 weeks and perinatal death. There was considerable overlap in the confidence intervals for these outcomes London 1982 and the other trials, suggesting no clear differences between subgroups. There was no evidence of a difference between subgroups according to the subgroup interaction test (Analysis 1.37; Analysis 1.38).

1.37. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 37 Subgroup analysis: detection of multiple pregnancy before 24 weeks (number not detected; concealed results.

1.38. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, Outcome 38 Subgroup analysis: perinatal death. Concealed results.

Sensitivity analysis (allocation concealment assessed as inadequate)

Two studies used a quasi‐randomised design (case note number London 1982; allocation by day of the week Johannesburg 2007). Removing these studies from the analysis did not affect overall results for the primary outcomes. None of the studies had very high levels of attrition (more than 20%) for primary outcomes.

Only one outcome (perinatal death) included data from 10 studies (Analysis 1.4); we produced a funnel plot to look for plot asymmetry which can suggest publication bias; there was no asymmetry apparent on visual inspection (Figure 3).

3.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Routine/revealed versus selective/concealed ultrasound in early pregnancy, outcome: 1.4 Perinatal death (all babies).

Discussion

Summary of main results

Ultrasound for fetal assessment in early pregnancy increases the chances of the detection of multiple pregnancy before 24 weeks' gestation, and there is some evidence that fetal abnormalities are detected earlier. Routine scanning is associated with a reduction in inductions of labour for 'post‐term' pregnancy, and this contributes to a small reduction in the overall rates of induction (for any indication). Routine scans do not seem to be associated with reductions in adverse outcomes for babies or in health service use by mothers and babies. At the same time, long‐term follow‐up of children exposed to a scan in utero does not indicate that scans have a detrimental effect on children's physical or cognitive development.

Considerable caution needs to be exercised in interpreting the results of aspects of this review in view of the fact that there is considerable variability in both the timing of the intervention and the number of scans that women received during pregnancy.

The assumed benefits of routine ultrasonography in early pregnancy have been: (1) better gestational age assessment; (2) earlier detection of multiple pregnancies; and (3) detection of clinically unsuspected fetal malformation at a time when termination of pregnancy is possible.

These assumptions appear to have been justified by analysis of data from the studies included in this review. The reduced incidence of induction of labour in the routinely scanned groups presumably results from better gestational 'dating', and earlier detection of multiple pregnancy. However, the high levels of heterogeneity for the former outcome means caution should be applied. Whilst routine ultrasound assessment in early pregnancy has not been shown to improve fetal outcome, much larger numbers of participants would be required to demonstrate that better gestational ‘dating’ and earlier detection of multiple pregnancy result in improved outcomes for babies.

The detection of fetal malformation has been addressed in detail only in two of the trials. The Helsinki 1990 trial showed improved detection with a resultant increase in the termination of pregnancy rate and a drop in perinatal mortality. There were, however, large differences in the detection rates between the two hospitals involved in this study, which shows that variation in skill and expertise can impact on performance and effectiveness of ultrasonography, and highlights the need for education, training, audit and quality control. This point is further emphasised by the low detection rate of major fetal malformations in the large RADIUS 1993 trial ‐ only 17% of such babies were identified in the ultrasound screened group before 24 weeks of pregnancy. Based on the Helsinki 1990 trial results and other reports of observational data, this implies unsatisfactory diagnostic expertise. A combination of low detection rates of malformation, together with a gestational age limit of 24 weeks for legal termination of pregnancy in the RADIUS 1993 trial, produced minimal impact on perinatal mortality, unlike the Helsinki 1990 experience.

The majority of obstetric units in the developed world already practice routine early pregnancy ultrasonography. For those considering its introduction, the benefit of the demonstrated advantages needs to be considered against the theoretical possibility that the use of ultrasound during pregnancy could be harmful, and the need for additional resources. At present, there is no clear evidence that ultrasound examination during pregnancy is harmful. The findings from the follow‐up of school children and teenagers, exposed as fetuses to ultrasound in the Norwegian and Swedish trials (Norway 1993; Sweden 1988) are generally reassuring; the finding that fewer children in the Norwegian ultrasound groups were right‐handed was not confirmed by intention‐to‐treat analysis of long‐term follow‐up data from the Swedish trial. The Norwegian finding is difficult to interpret and may have been a chance observation that emanated from the large number of outcome measures assessed, or from the method of ascertainment. Alternatively, if it was a real consequence of ultrasound exposure, then it could imply that the effect of diagnostic ultrasound on the developing brain may alter developmental pathways. No firm conclusion can be reached from available data, and there is a need to study these children formally rather than to rely on a limited number of questionnaire responses obtained from the parents (Paneth 1998).

Financial costs also need to be considered. Calculations by the authors of the Radius report indicate that screening four million pregnant women in the USA at 200 dollars per scan would increase costs by one billion dollars per year (LeFevre 1993). While costs have been shown to be less in other countries (Henderson 2002; Roberts 2002), economic issues will still be relevant, particularly in low‐resource settings. Clinicians, health planners, and pregnant women need to decide if these results justify the expense of providing routine ultrasound examination in early pregnancy. The early Helsinki 1990 data may have overestimated the efficiency of scans. Cost savings were assumed on the basis of decreased perinatal mortality, which was not borne out in other studies.

Maternal anxiety and satisfaction have not been well explored in the studies included in this review. Parents may not be fully informed about the purpose of routine ultrasonography and may be made anxious, or be inappropriately reassured by scans (Garcia 2002; Lalor 2007). Ultrasound scans are, however, popular ‐ the potential enjoyment that parents can receive from seeing the image of their baby in utero is discussed elsewhere (Neilson 1995).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The review includes several large trials, although the eligibility criteria of some trials (e.g. RADIUS 1993) mean that results may not be generalisable to all women.

The majority of studies were carried out in high‐resource settings where overall levels of perinatal mortality are low and the contribution of major fetal abnormality to mortality is higher than in lower‐resource settings. Findings in high‐resource settings may not apply in less affluent settings.

Studies were carried out over three decades and technical advances in equipment, more widespread use of ultrasonography in the developed world, and training and expertise of operators are likely to have resulted in more effective sonography, particularly for the detection of fetal abnormalities. The two trials which evaluated detection of fetal abnormality are probably not relevant in today's setting.

Quality of the evidence

Overall, the review includes several large, well‐designed trials but the lack of blinding is a problem common to all of the studies and this may have an effect on some outcomes. The quality of evidence was assessed for all review primary outcomes using GRADEpro 2014. The evidence for detection of fetal abnormality and multiple pregnancy before 24 weeks' gestation outcomes was judged as moderate. The quality of evidence was low for induction of labour for 'post‐term pregnancy' and 'perinatal death' (all babies) outcomes. Downgrading of evidence was based on including studies with design limitations, imprecision of results and presence of heterogeneity.

Potential biases in the review process

The possibility of introducing bias was present at every stage of the reviewing process. We attempted to minimise bias in a number of ways; two review authors assessed eligibility for inclusion, carried out data extraction and assessed risk of bias. Each worked independently. Nevertheless, the process of assessing risk of bias, for example, is not an exact science and includes many personal judgements. Further, the process of reviewing research studies is known to be affected by prior beliefs and attitudes. It is difficult to control for this type of bias in the reviewing process.

While we attempted to be as inclusive as possible in the search strategy, the literature identified was predominantly written in English and published in North American and European journals. Although we did attempt to assess reporting bias, constraints of time meant that this assessment largely relied on information available in the published trial reports and thus, reporting bias was not usually apparent.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We have not been able to identify many other studies or reviews in this area. The few studies identified focus mainly on the identification of fetal anomalies in early pregnancy. One study (Drysdale 2002), is a pilot study for screening by ultrasound examination of all women, presenting to their community midwife before 12 weeks' gestation. The included women were at high risk and had abnormal pregnancies. The researchers found that early pregnancy ultrasound at 12 to 14 weeks' gestation was an effective method of identifying and screening for major abnormalities of pregnancy. Five of the seven major abnormalities diagnosed were identified before the 20‐week anomaly scan. The authors emphasised the importance of using this in conjunction with an anomaly scan at around 20 weeks' gestation. Women found this method of screening acceptable. Rossi 2013, a systematic review, tested the accuracy of ultrasonography at 11 to 14 weeks of gestation for detection of fetal structural anomalies. Inclusion criteria were fetal anatomy examination performed at 11 to 14 weeks of gestation and confirmation of the early diagnosis of fetal malformations by postnatal or postmortem examination in addition to many others. In this systematic review, which included 19 studies, the overall fetal structural anomalies detection rate was 472 of 957 (51%). The authors stated that the number of fetal malformations remain undetected by early ultrasonography. We were unable to find other studies that address the other primary outcomes of this review.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Routine early pregnancy ultrasonography has been shown to detect multiple pregnancy earlier (moderate quality evidence), and to reduce induction of labour for post‐term pregnancy (low quality evidence), both of which could be clinically useful if resources allow.

Implications for research.

Other benefits which could result from better gestational age assessment, e.g. better management of pregnancies complicated by fetal growth retardation, need to be assessed in much larger studies than have been reported so far.